ABSTRACT

Increased migration to OECD countries has made unemployed foreign-born immigrants a new target population for ‘activation’ policies to reintroduce people into the labour market. As populations receiving employment activation interventions became more diverse, individualisation of activation measures was introduced into guidelines for welfare and employment agencies. While a person-centred approach in employment-oriented social work is gaining popularity, there is little research relating to how such approaches fit the frameworks of relatively aggressive activation. This study presents a qualitative instrumental case study exploring interactions between activation policy and person-centred employment interventions with immigrant jobseekers in Norway. Data analysis applied critical orientation towards data and employed directed content analysis. Research questions include: (1) How well do person-centred principles fit with the policy of activation? (2) How do person-centred practice and activation measures interact, and what are the congruencies and tensions? (3) What are the effects and practical implications of these congruencies and tensions? Findings from the present case study indicate the policy of activation strongly affects opportunities to implement person-centred practice in vocational counselling. Further, the political agenda of activation is inconsistent with the intentions of supported employment implementation to make vocational services jobseeker-centred or jobseeker-driven.

SAMANDRAG

Økt innvandring til OECD-landene har ført til at arbeidsledige innvandrere er blitt en ny målgruppe for “aktiverings”-tiltak som skal hjelpe mennesker tilbake inn på jobbmarkedet. Etter hvert som stadig flere typer befolkningsgrupper blir gjenstand for aktiveringstiltak, har man i retningslinjene for velferds- og arbeidskontorer innført individualisering av aktiveringstiltak. Mens personsentrert tilnærming innen arbeidsrettede sosialt arbeid blir stadig mer populært, finnes det lite forskning på hvordan slike tilnærmingsmetoder passer inn i rammeverkene for den forholdsvis dramatiske aktiveringen som finner sted. Denne studien presenterer en kvalitativ instrumentell casestudie som utforsker samhandlingen mellom aktiveringspolitikk og personsentrerte tiltak for utenlandske jobbsøkere i Norge. Det er anvendt dataanalyse ved kritisk orientering overfor data og direkte innholdsanalyse. Følgende spørsmål ble stilt ved undersøkelsen: 1) Hvor forenlige er personsentrerte prinsipper med aktiveringspolitikken? 2) På hvilke områder samhandler personsentrert praksis og personsentrerte aktiveringstiltak? På hvilke måter stemmer de overens, og hvor ligger spenningsforholdene? 3) Hva er virkningene og de praktiske implikasjonene av disse overensstemmelsene og spenningsforholdene? Funn fra denne casestudien tyder på at aktiveringspolitikken har sterk innvirkning på mulighetene for å implementere en personsentrert praksis ved yrkesrådgivning. Dessuten er det ikke samsvar mellom den politiske agendaen for aktivering og hensikten med støttet sysselsetting, som er å gjøre arbeidsformidlingstjenestene mer sentrert omkring jobbsøkeren.

Introduction

During the last two decades, social work has shown an interest towards adopting the principles of person-centred practice that allow independent functioning and promote respect for individuality (Gardner, Citation2014; Washburn & Grossman, Citation2017), empowerment, self-determination, and autonomy of social service users (Hansen & Natland, Citation2017).

At the same time, due to the economic disturbances and rising unemployment rates experienced by the welfare states since 1990, welfare-to-work policies had to toughen demands and rules for recipients of welfare and unemployment benefits in an attempt to reintroduce them into the labour market, making unemployment a significantly tougher experience (Immervoll & Knotz, Citation2018; Pinto, Citation2019). These changes, often referred to as ‘active labour market policies’ (ALMP), or ‘activation’ (Bonvin, Citation2008; Gubrium et al., Citation2014; Immervoll & Knotz, Citation2018), pivot on the notion of an active citizen who is self-sufficient and responsible for social self-integration primarily through participation in the labour market (Nothdurfter, Citation2016). Social workers have become the agents of coercive activation policies turning social work into ‘activation work’ (Nothdurfter, Citation2016) with a focus on quick integration of the unemployed into the labour market (Hansen & Natland, Citation2017; Nothdurfter, Citation2016).

Adding to this, significantly increased migration to OECD countries during the last two decades has seen unemployed immigrants (foreign-born population) as a new target group for activation policies (Auer et al., Citation2017; Breidahl, Citation2017; Renema & Lubbers, Citation2019). Activation arguably facilitates their integration into the labour market and society of the host country (Breidahl, Citation2017; Jensen & Pfau-Effinger, Citation2005).

As populations receiving activation interventions became more diverse, individualisation of activation measures was introduced into guidelines for welfare and employment agencies (Solvang, Citation2017; van Berkel & Knies, Citation2018), and person-centred practice was touted as a facilitator of individualisation (Leplege et al., Citation2007; Lewis & Sanderson, Citation2011).

The Norwegian context

To reduce bureaucracy and facilitate interagency collaboration, Norwegian social insurance, employment, and local social assistance agencies were united under one organisation in 2006, the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration (NAV) (Gubrium et al., Citation2014; NAV, Citation2019b; Røysum, Citation2010). NAV became the frontline of the employment-oriented social work and activation measures in Norway targeting the long-term unemployed, young unemployed, people with reduced working capacity, and unemployed immigrants from outside the European Economic Area (EEA; Finansdepartementet, Citation2019).

Activation in Norway is characterised by a ‘human capital’ approach to unemployment (Andreassen, Citation2019; Gubrium et al., Citation2014), including developing the skills and qualifications of an individual, who in return is expected to apply those skills to contribute to society (Dean, Citation2006). In the context of NAV employment measures, this includes assessment of working capacity, requalification, work trials, and employer incentives to stimulate the employment of jobseekers with limited working capacity (NAV, Citation2019a).

Alongside the introduction of activation policies, Norwegian social workers have argued for an empowering rather than a coercive approach (Andreassen, Citation2019; Hansen & Natland, Citation2017) with a growing interest in person-centred interventions such as developing individual plans for social service users (Breimo, Citation2016). In vocational follow-up, person-centred supported employment (Bonfils et al., Citation2017; European Union of Supported Employment, Citation2010) is offered to some groups of jobseekers, with immigrant jobseekers most recently included as recipients of this type of intervention (Maximova-Mentzoni, Citation2019).

While a person-centred approach in employment-oriented social work is gaining popularity, there is a dearth of research investigating how person-centred practice fits into the frameworks of relatively aggressive ‘activation’ policies, including if it undergoes any modification, or if it continues to adhere closely to its stated principles in this reciprocal action.

The research presented in this article is a case study of immigrant jobseekers who participated in supported employment in Norway. We explored the interactions between activation policy and person-centred supported employment intervention. The broad research questions were: (1) How well do person-centred principles fit with the policy of activation? (2) How do person-centred practice and activation measures interact, and what are the congruencies and tensions? (3) What are the effects and practical implications of these congruencies and tensions? The study first offers a critical introduction to both ‘activation’ policies and person-centred approaches before introducing the research in more detail.

Activation

Proponents of activation stress the importance of active citizenship for a welfare state and synonymise ‘active citizen’ with contributing to society as a self-sustained ‘worker-citizen’ (Clarke, Citation2005). These authors underline that activation facilitates social inclusion of the marginalised population groups, such as immigrants, and promotes their active citizenship through integration into the labour market (Jensen & Pfau-Effinger, Citation2005; Nybom, Citation2011) and participation in the community as valuable members (Christiansen & Townsend, Citation2010). They argue that under activation policies, job search support has proven to be cost-effective and increased employment rates, particularly in the short- and medium-term for diverse target groups (Kluve & Rani, Citation2016). However, a number of researchers have questioned how reasonable activation measures are in other respects.

Despite vocational follow-up in social work being conceptualised as facilitating a person’s vocational potential, often the only activity considered to be meaningful is paid work (Bonvin, Citation2008; Fadyl et al., Citation2019). Consequently, all other jobseeker engagements are neglected or downplayed in the process of work-oriented follow-up. The lack of assistance from social workers in dealing with other challenges for the jobseeker, such as family or accommodation issues, leads to an imbalance that, together with continuous unsuccessful attempts to obtain employment, results in disappointment, frustration, and increased chance of ‘deactivation’ relapse (Hibbard & Mahoney, Citation2010; van Hal et al., Citation2012).

Indeed, even though ‘activation’ aims at inclusion through work and contribution to society, it may in fact generate social exclusion instead: first, by guiding and nudging a person towards a decision considered appropriate by the social worker, or by making the decision on her or his behalf instead of encouraging self-determined choice and assisting in pursuing it (Gibson et al., Citation2019; van Hal et al., Citation2012). Second, by failing to assist those who are unable to articulate their needs or ask for help when they need it (van Hal et al., Citation2012). Third, by sanctioning those who are already economically vulnerable (Eleveld, Citation2017), and stigmatising them (Kluve & Rani, Citation2016).

Resource-consuming activation also increased the caseloads on caseworkers, with every caseworker following around 100 jobseekers simultaneously, thus decreasing the quality of the work-oriented follow-up (Hainmueller et al., Citation2016). Therefore, according to Hudson et al. (Citation2010), ‘creaming and parking’ occurs when vocational counsellors prioritise the jobseekers they consider employment-ready and provide a minimised service to hard-to-employ jobseekers, including ethnic minority groups with cultural and language barriers.

Person-centred practice

McCance and McCormack (Citation2010) argue that the basis of person-centred practice comprises philosophical perspectives on the meaning of being a person, with a focus on humanness that includes beliefs, values, and experiences that explain authentic choices and ‘the way we construct our lives’ (p.5). They argue that every person has an ‘inborn potential’ that is developed and exercised through social relations. Person-centred practice’s focus on authenticity and elimination of constraints allows the realisation of an individual’s full potential or the closest approximation to it that is achievable.

Person-centred counselling, first described by Carl Rogers (Citation1951), placed an emphasis on every person being the expert on their own life and guiding the received service in the direction that is important for him or her, thus finding the solution to their own problems. Counsellors were to acknowledge the person in their clients, knowing their history and being able to empathise with them while providing non-directive counselling, thus constructing a trust-based productive relationship.

Person-centred practice as developed in health and social care disciplines over the last few decades focuses on partnership between the service provider and the person, and their shared responsibility for the person’s well-being, with empowering and holistic follow-up touching on multiple spheres of the person’s life (Louw et al., Citation2017). Its adoptation into social work from health care (Washburn & Grossman, Citation2017) accentuated the importance of the holistic well-being of the person and underlined the importance of their preferences, expectations, needs and wishes (Carvajal et al., Citation2019).

While there is no commonly accepted definition of what person-centred practice is (Waters & Buchanan, Citation2017), scholars agree that there are core elements it includes. Therefore, a broad definition of person-centred practice describes a service that attends to the individual circumstances, needs, and preferences of a service user by involving them in service planning; respecting the person’s authenticity, self-determination, and choice; supporting interpersonal relations and social inclusion; being strength focused; and facilitating engagement in the service (Louw et al., Citation2017; McCance & McCormack, Citation2016; Waters & Buchanan, Citation2017).

A key strategy of person-centred practice is construction of a trust-based ‘therapeutic’ relationship between the person and the service provider that facilitates the person’s openness to challenges and the anticipation of their needs and thus, helps to adjust assistance accordingly, resulting in positive service outcomes (Crisp, Citation2015; Hamovitch et al., Citation2018; Parr, Citation2016).

Person-centred practice has been suggested as a means to achieve a quality service, and as such has become a key aspect of social and health policy in a range of countries (Christie & Camp, Citation2014; Waters & Buchanan, Citation2017). Person-centred policy encourages structures such as integrated services and multi-disciplinary teams, and practices like direct payment (where service users control funding allocation), as well as supporting an informed decision-making to benefit service recipients (Glasby, Citation2016).

Despite its increasing popularity, person-centred practice has also been criticised, particularly in the context of case management where individualisation is sometimes operationalised as client responsibilisation. The issues debated include: lack of help when needed; creating victim blaming by expecting the individuals to resolve problems by their own effort; potentially creating unachievable goals; and inducing guilt for not doing enough to improve one’s own life (Gibson et al., Citation2012; Kahn, Citation1999; Waterhouse, Citation1993).

Implementation of this approach can also be challenging. Critiques highlight issues such as a counsellor’s lack of knowledge or skills, lack of understanding of what person-centred practice should be, reported difficulty in switching from traditional provider-centred service, and imposing their own (more ‘expert’ or ‘informed’) goals as more realistic ones (Cooper, Citation2004; Richard & Knis-Matthews, Citation2010).

Study design

This study is a part of a wider PhD research project which received ethical approval from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data.

In accordance with the aims described above, the methodology employed a qualitative instrumental case study. This type of case study serves to acquire understanding of a certain phenomenon through examining a case, focusing on a particular phenomenon (in our study, person-centred practice and its interaction with activation policies), rather than the case itself (Casey & Houghton, Citation2010; Luck et al., Citation2006).

For this case study, we looked specifically at:

The extent to which: (a) activation, and (b) person-centred practice are evident in vocational intervention with immigrant jobseekers.

The opportunities and constraints for person-centred practice in the context of activation.

Our case was a NAV location with a well-established supported employment programme targeting immigrant jobseekers. They participated in supported employment through Job Chance (Jobbsjansen), or as part of the Introduction Programme (Introduksjonsprogrammet). Job Chance targets home-based immigrant women who struggle to obtain employment, while the Introduction Programme is designed for newly arrived refugees and includes tutoring in various aspects of Norwegian society, including introduction into the labour market.

The first author collected the data. First, she approached employment specialists regarding their interest to participate in this study. Having agreed, they offered help in contacting and inviting jobseekers. Before beginning data collection, the first author also obtained necessary permission for conducting research from the head of the NAV office as well as the NAV County office.

Semi-structured interviews and non-participant observations were employed. The interviews included questions that explored jobseekers’ or employment specialists’ experiences of the intervention, what they liked or did not like, challenges experienced, suggested improvements, and how the employment specialists helped the jobseekers to achieve their personal goals, if at all.

Observations of meetings between jobseekers and employment specialists focused on the communication flow between the jobseeker and the employment specialist, including who talked most, what issues they raised, and the other party’s responses. The first author interviewed jobseekers and employment specialists before or after meetings, according to their availability.

Prior to conducting each interview or observing meetings, research participants confirmed and signed consent to participate. Explicit consent to use a voice recorder was also sought. Five participants consented to participate in the research but not voice recordings. In these cases, hand-written notes were taken.

When transcribing interviews, each participant was allocated a pseudonym that was used throughout the interview transcript and observation notes. After transcriptions and anonymization were completed, the original data was erased.

The interviews were conducted and transcribed in Norwegian, while data analysis and analytical coding was done in English. As the transcript was in Norwegian, the first author referred to it throughout the analysis to assure that the proper meaning was interpreted and conveyed. Interview extracts presented in this article are transcribed according to intelligent verbatim and translated.

Data analysis

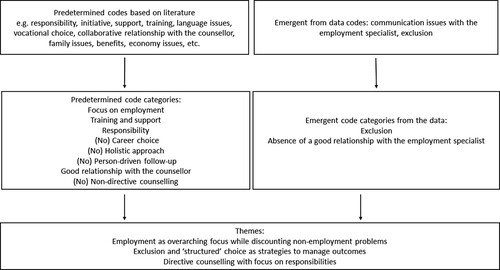

Our data analysis applied critical orientation towards data and employed directed content analysis as described by Hsieh and Shannon (Citation2005). This type of content analysis is used when the goal of the research is the further development and differentiation of existing knowledge. Thus, coding of data is done using a coding framework derived from pre-existing research and includes key characteristics of the phenomenon of interest. During the process of coding, new codes and sub-codes may emerge from the data that will extend the coding. This type of content analysis builds on existing knowledge by identifying the way in which the phenomenon occurs in the data, as well as adding new information about the phenomenon that emerges from the study. Coding processes were managed using NVivo v12 software. shows the coding structure with examples of codes and consequent emergence of the themes. The arrows show the coding process algorithm.

We developed our coding framework from theoretical and conceptual literature in both activation policy and person-centred practice in a rehabilitation and social work context. Emergent codes are the codes that we did not predetermine because they were not derived from the literature reviewed. The emergence of these codes was not anticipated.

We repeated the coding process several times to ensure appropriate coding of all relevant information. The codes were combined in categories that in turn constructed themes, which are presented in the results section.

Results

Participants

In total, data consisted of 23 interviews and 10 observations of meetings between jobseekers and employment specialists, conducted between July–October 2018.

This data comprised 18 individual interviews with jobseekers (5 male, 13 female) who participated in supported employment as part of the Introduction Programme and Job Chance. They originated from Syria (n = 5), Eritrea (n = 2), Somalia (n = 2), Kosovo (n = 2), Iran (n = 2), Romania (n = 1), Democratic Republic of the Congo (n = 1), Bosnia (n = 1), Kurdistan (n = 1), and Nigeria (n = 1), and were aged between 25 and 50. The employment specialists had assessed them as ‘employment ready’, i.e. ready to take up employment at any time.

Four individual interviews and one group interview were conducted with four employment specialists (1 male, 3 female). All employment specialists had previous working experience as caseworkers in NAV. They had also acquired supplementary education in supported employment and motivational interviewing. One also had experience of working as a follow-up counsellor in a mental health institution, one worked at the municipality follow-up service for people with mental health problems, and one had experience as a nurse. Each employment specialist worked with up to 20 jobseekers.

Findings

Overall, the findings from our analysis indicate that the person-centred approach is present to some degree but is largely influenced and modified by activation principles.

Having analysed our codes, we constructed the following three themes: employment as the overarching focus while discounting non-employment problems; exclusion and ‘structured’ choice as strategies to manage outcomes; and directive counselling with focus on responsibilities. Further, we expand on these themes through a discussion of the data. Thereafter, we discuss the interaction between activation and person-centred practice as evident from the data.

Employment as an overarching focus while discounting non-employment problems

Data clearly indicated that the employment specialists were acutely aware of their perceived role as focused on employment and were well prepared to support jobseekers in the job-hunting process. They provided assistance in searching for employment opportunities, preparation and sending of CVs and cover letters, and training in interview skills. They approved supplementary courses for the jobseekers if those facilitated employment, accompanied them to meet employers, and approved incentives to stimulate employers to employ or provide a work trial. They also addressed the importance of mastering language skills, described differences in working culture, such as shaking hands with customers or wearing hijab at work, and other issues that affected how jobseekers operated in job-related situations.

At the same time, jobseekers’ problems perceived to be non-employment-related were generally not addressed by the employment specialists. The jobseekers spoke of struggling with problems within their families, encounters with child protection services, worries for and necessity to attend to close family members living abroad, and challenges in establishing a network outside of the family.

My sister died, then she had to be transported and buried in [homeland]. I was very sad, to go to school [language and employment courses] did not go very well […]. (Ajola, jobseeker)

We talk about job, economy, home, how it is going at home, how you pay your invoices […] I feel really sad and just break down and start crying […] Sometimes you feel like this programme is not helping you. (Neema, jobseeker)

I make it clear from the first meeting that my job is to help them to find employment and I cannot answer [other] questions […] I think it is good that we are not responsible for these. It would detract from the employment specialist role. I don’t think it would be possible to put under one role. (Inger, employment specialist)

Others did not see a problem with employment pressure and considered it the point of the intervention. At the same time, they expressed frustration that some jobseekers travelled to other countries because of family matters when they were in an active job search process in Norway, thus missing out on employment opportunities.

It emerged that jobseekers referred to employment specialists who assisted them with non-employment-related issues in a more positive way than those whose employment specialists focused solely on employment goals. They were also more satisfied with the collaboration process.

It is important to find someone who you can talk to and she understands you and gives you advice: you can do this, you can do this. (Neema, jobseeker)

They don’t attack, like, but when you say something – they don’t like it. It is childish, but it hurts. (Thomas, jobseeker)

Strategies to manage outcomes: exclusion and ‘structured’ choice

From the interviews with employment specialists, it emerged that some jobseekers wishing to participate in supported employment, or who were referred to supported employment by their caseworkers in NAV were not admitted to the intervention for various reasons, mostly lack of resources.

Though supported employment is an offer for everyone, we have so limited resources that we have to prioritise, though we should not. (Inger, employment specialist)

The jobseekers identified as having poor language skills were either denied enrolment or sent for a three-month language course precluding their participation in the intervention.

I would like to have a conversation with them without an interpreter. Then they will go straight into work life. The employers are sceptical if someone cannot speak Norwegian at all. (Veronica, employment specialist)

Prolonged participation in work trials instead of employment was a point of frustration for many interviewed jobseekers. While some of them received work trials in their desired industry, they struggled to get a job offer. Therefore, while jobseekers could express their career choices, they were guided by employment specialists towards ‘realistic’ job opportunities, for example, as a cleaner instead of a kitchen assistant. If employment specialists considered the career choice unrealistic or hard to implement, they prompted jobseekers to change their career goal and pursue another vocation.

Together with the unavailability of job vacancies with preferred employers, reasons to modify career choice were not based on jobseeker needs and preferences, but rather on the local and regional labour market needs, jobseekers’ qualifications, and the possibility of obtaining the desired job through requalification. Some jobseekers expressed disappointment because of choice limitations due to their geographical location and limitations in the labour market, though they understood the need for compromise.

Together with employment, applying for full-time tertiary education instead of employment was technically a possibility for the Introduction Programme’s participants. However, employment specialists appeared not to view this as desirable for jobseekers approaching their 50s.

If you come to Norway as 45 year-old and have seven kids, and if both the husband and the wife will study, how will you support yourself? You need somehow to support yourself! It is true that in Norway you can become what you want to, but you need to prioritise […] It is very challenging to dampen these demands or wishes of education. (Andy, employment specialist)

Directive counselling with focus on responsibilities

In the meetings with immigrant jobseekers, employment specialists emphasised striving to achieve employment goals to become self-supportive. Jobseekers were responsible for contacting potential employers, applying for relevant jobs, and improving language skills.

First, I applied for jobs. She said: ‘you must apply for jobs by yourself, you need to try to apply for jobs alone.’ (Alina, jobseeker)

They say: ‘you must look for a job by yourself. And we can also help you.’ (Larissa, jobseeker)

Jobseekers were expected to be available for impromptu meetings, unless they were in an employment-relevant activity. The meetings were mainly updates of the current situation in the job seeking process and making agreements on what the jobseeker should do next.

We only observed one self-determined initiative shown by a jobseeker, who decided to pursue education in another town and would therefore quit supported employment if accepted. We saw mainly directive counselling employed by the employment specialists, though one employment specialist mentioned the visualisation techniques she employed with her jobseekers, such as asking them to imagine where they were in five years (the employment goal) and what they had done to achieve it.

In one observed meeting, an employment specialist reminded a jobseeker that her time in the programme was nearly finished, including the benefits connected with it, and asked her what she planned to do next. The employment specialist put responsibility for the situation on the jobseeker as she had not applied for the jobs she was referred to, while the jobseeker seemed to be in distress. She swung between explaining her perceived duty as a mother and being available for her young children when they come home from school, the need for a stable income, and her hopes to find a job that would correspond with her interests and qualifications.

Here, we observed a close correlation between directive counselling and the denial or heavy structuring of choice when the jobseeker was reminded that the job-hunting process was her responsibility, as she had not applied the jobs suggested to her.

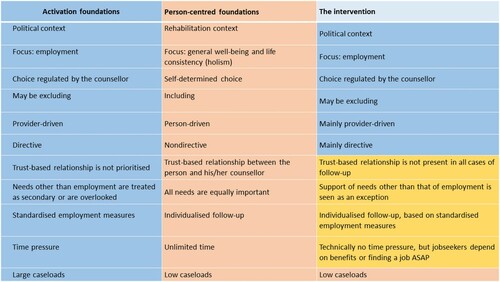

In summary, depicts the elements of activation and person-centred practice we identified in the studied intervention context in correlation to their foundations. The colour coding shows the dominance of activation measures in the intervention. In many cases, the practices we saw directly reflected activation policies. In others, a person-centred approach is modified by activation policies. The only aspect in which it is fully consistent with a person-centred framework is with respect to low caseloads.

Figure 2. Relationship between activation measures and person-centred practice in the intervention (supported employment).

Thus, analysis of the interviews and observations reveals that activation policy is dominant and affects opportunities for implementing person-centred practice in important ways. In the section below, we critically analyse this relationship further and consider recommendations for practice.

Discussion

Our case study indicates that activation policy strongly affects opportunities to implement person-centred practice in employment-oriented social work. The political agenda of activation is in many ways inconsistent with the intentions of supported employment implementation to make vocational services jobseeker-centred or jobseeker-driven.

The idea behind supported employment is that it is delivered in the context of person-centred practice (Bonfils et al., Citation2017; EUSE, Citation2010). However, the context in which these immigrant jobseekers received it in our study was more representative of keen activation measures than person-centred practice. Together with the absence of a holistic approach, overarching focus on employment, and constructed choice, exclusion and directive counselling rely on the political context of activation with its focus on getting the unemployed into work as soon as possible.

An unexpected finding was that despite the theoretical assumption common to both person-centred practice and supported employment that the services are inclusive, i.e. non-discriminative towards potential and current participants (e.g. EUSE, Citation2010; Kass, Citation2017), we observed clear examples of excluding practices. Our analysis indicates that it was used as a strategy to manage caseloads and (coupled with a structuring of choice) influence measurable outcomes. A lack of trust-based relationships between some of the jobseekers and employment specialists can be attributed to exclusionary techniques such as exclusion from the decision-making process, and one-sided focus of the employment specialist on enhancing employment opportunities without pursuing a holistic approach, addressing jobseekers’ other important needs. Along with the other indicators of activation dominance already discussed, this is a further indicator that supported employment as it is implemented in this context is scarcely person-centred.

This study further contributes to a discussion about whether it is possible to properly implement person-centred practice in the context of vocational follow-up. The labour market is demanding and discriminative (and arguably becoming more so; Branker, Citation2017; Dancygier & Laitin, Citation2014; Waite, Citation2017), and competition for jobs is high. In contrast, a person-centred approach may seem ‘soft’, impractical, or failing to prepare jobseekers for the challenges they may experience in the labour market while trying to obtain the ‘perfect job’.

Solely focusing on activation measures in order to turn the unemployed into ‘working citizens’ and minimising other aspects of being may be an unwise course for social policy and social work. A one-sided focus on employment can miss other ways a citizen can participate in the life of the community, including socially, politically, and civically (Jensen & Pfau-Effinger, Citation2005). The issues at stake are arguably not as straightforward as just ‘obtaining employment’. It is important not to underestimate the potential benefits of a person-centred approach, especially with vulnerable jobseekers.

The challenges experienced by the study target group are linked to complex issues such as family dynamics or adaptation to a new culture and community life, which affect employment potentials. As research in vocational rehabilitation continues to show, ‘work functioning cannot be understood outside its social context’ (Sandqvist & Henriksson, Citation2004, p. 155). Ensuring inclusion of jobseekers, allowing them to guide the job search process, and providing support are likely to decrease misunderstandings and help to develop the trust relationship with the counsellor. This in turn provides the opportunity to address complex psychosocial issues, which are the key barriers to positive vocational outcomes internationally (Fadyl et al., Citation2010; Sandqvist & Henriksson, Citation2004). From this perspective, a person-centred approach in social work is essential for sustainable outcomes.

Practical implications

The absence of a holistic approach in employment-oriented social work leads to situations where jobseekers risk many problems affecting their wellbeing and vocational success remaining hidden, or not being discussed in the necessary depth to be solved. There is a clear need for a more holistic approach that supports other needs and makes the employment specialist more effective.

We suggest that employment specialists’ qualifications and skills correspond with possibilities to provide holistic follow-up for unemployed people, enabling this role in social work to be delegated to them. It would help to avoid making the jobseeker a ‘shuttlecock’ of the system by redirecting them to other actors, facilitating a therapeutic relationship that the jobseeker would benefit from the most. The political agenda of activation needs to recede to allow employment specialists to learn, practice, and utilise holistic counselling. Consequently, reduced caseloads would allow time to address the real needs and goals defined by the jobseeker, where employment is an element of the holistic assistance of social work.

Study limitations and suggestion for further research

Due to limited time and resources, we conducted one set of interviews and observed a limited number of meetings. Therefore, we suggest a longitudinal study that would look at the process of person-centred practice in vocational counselling at all stages, following jobseekers from enrolment into person-centred vocational counselling and finishing after obtaining a job and/or stopping participation in the intervention. This would help to register all the possibilities for the dominance of activation over the person-centred approach, and to evaluate the reasonableness of this deviation by assessing the overall life quality of the jobseekers and consequently, to support this tendency or suggest how to change it.

Conclusion

We have explored how vocational person-centred practice is congruent with the policy of activation. We found that while certain features of the person-centred approach, such as low caseloads and attempts to individualise the follow-up are present, activation is the keynote of vocational counselling and the intense pursuit of employment hinders actualisation of a person-centred approach.

This study extends knowledge on activation theory and person-centred approaches and serves as a base for further knowledge development on implementation of person-centred approaches in the frames of vocational counselling. The findings of our research may engage practitioners and policy makers who work with person-centred practice in general and implementing person-centred approaches in vocational counselling in particular.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Christine Cummins and Gareth Terry for the valuable comments that helped improve our article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mariya Khoronzhevych

Mariya Khoronzhevych is a PhD fellow at OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University in Norway. Her PhD study in social work and social policy focuses on labour integration of immigrants in Norway with focus on immigrant jobseekers’ activation and engagement. She holds a Master Degree in Peace and Conflict Transformation from University of Tromsø in Norway and a Master Degree in Secondary Education from Kherson State University in Ukraine. Her main research interests are immigration, social policy and integration of immigrants, international politics and conflict transformation.

Joanna Fadyl

Joanna Fadyl is a senior lecturer at Auckland University of Technology and deputy director of AUT's Centre for Person Centred Research, a centre for trans-disciplinary research and teaching in rehabilitation and disability. Her research programme has a focus on vocational rehabilitation and includes exploring how different methodologies can open up new opportunities to address challenges.

References

- Andreassen, T. A. (2019). Measures of accountability and delegated discretion in activation work: Lessons from the Norwegian labour and welfare service. European Journal of Social Work, 22(4), 664–675. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1423548

- Auer, D., Bonoli, G., & Fossati, F. (2017). Why do immigrants have longer periods of unemployment? Swiss evidence. International Migration, 55(1), 157–174. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12309

- Bonfils, I. S., Hansen, H., Dalum, H. S., & Eplov, L. F. (2017). Implementation of the individual placement and support approach – facilitators and barriers. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 19(4), 318–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2016.1222306

- Bonvin, J.-M. (2008). Activation policies, new modes of governance and the issue of responsibility. Social Policy and Society, 7(3), 367–377. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746408004338

- Branker, R. R. (2017). Labour market discrimination: The lived experiences of English-speaking Caribbean immigrants in Toronto. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 18(1), 203–222. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-016-0469-x

- Breidahl, K. N. (2017). Scandinavian exceptionalism? Civic integration and labour market activation for newly arrived immigrants. Comparative Migration Studies, 5(1), 2. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-016-0045-8

- Breimo, J. P. (2016). Planning individually? Spotting international welfare trends in the field of rehabilitation in Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 18(1), 65–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15017419.2014.972447

- Carvajal, A., Haraldsdottir, E., Kroll, T., McCormack, B., Errasti-Ibarrondo, B., & Larkin, P. (2019). Barriers and facilitators perceived by registered nurses to providing person-centred care at the end of life. A scoping review. International Practice Development Journal, 9(2), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.92.008

- Casey, D., & Houghton, C. (2010). Clarifying case study research: Examples from practice. Nurse Researcher, 17(3), 41–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2010.04.17.3.41.c7745

- Christiansen, C. H., & Townsend, E. A. (2010). Introduction to occupation: The art and science of living (2nd ed.). Pearson.

- Christie, J., & Camp, J. (2014). Critical reflection on the process of validation of a framework for person-centred practice. International Practice Development Journal, 4(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.42.008

- Clarke, J. (2005). New labour’s citizens: Activated, empowered, responsibilized, abandoned? Critical Social Policy, 25(4), 447–463. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018305057024

- Cooper, M. (2004). Person-centred therapy: myths and reality. Working paper. https://pure.strath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/18354036/2004_myths_of_PCA.pdf

- Crisp, R. (2015). Can motivational interviewing be truly integrated with person-centered counselling? The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 21(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/jrc.2015.3

- Dancygier, R. M., & Laitin, D. D. (2014). Immigration into Europe: Economic discrimination, violence, and public policy. Annual Review of Political Science, 17(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-082012-115925

- Dean, H. (2006, October 20–21). Activation policies and the changing ethical foundations of welfare. ASPEN/ETUI Conference: Activation Policies in the EU. Brussels.

- Eleveld, A. (2017). Activation policies: Policies of social inclusion or social exclusion? The Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 25(3), 277–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/175982717X15024428691894

- European Union of Supported Employment. (2010). European Union of supported employment toolkit. http://euse.org/content/supported-employment-toolkit/EUSE-Toolkit-2010.pdf

- Fadyl, J. K., Mcpherson, K. M., Schlüter, P. J., & Turner-Stokes, L. (2010). Factors contributing to work-ability for injured workers: Literature review and comparison with available measures. Disability and Rehabilitation, 32(14), 1173–1183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/09638281003653302

- Fadyl, J. K., Teachman, G., & Hamdani, Y. (2019). Problematizing ‘productive citizenship’ within rehabilitation services: Insights from three studies. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1573935

- Finansdepartementet. (2019). Muligheter for alle — Fordeling og sosial bærekraft. [Possibilities for everyone – distribution and social sustainability]. Meld. St. 13 (2018–2019). Stortingsforhandlinger.

- Gardner, A. (2014). Personalisation - where did it come from?. In A. Gardner, J. Parker & G. Bradley (Eds) Transforming Social Work Practice Series: Personalisation in social work (pp. 1–19). 55 City Road, London: SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473922471.n1

- Gibson, B., Teachman, G., Wright, V., Fehlings, D., Young, N., & McKeever, P. (2012). Children's and parents’ beliefs regarding the value of walking: Rehabilitation implications for children with cerebral palsy. Child: Care, Health and Development, 38(1), 61–69. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01271.x

- Gibson, B., Terry, G., Setchell, J., Bright, F., Cummins, C., & Kayes, N. (2019). The micro-politics of caring: Tinkering with person-centered rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation, 42(11), 1529–1538. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2019.1587793

- Glasby, J. (2016). Person-centred approaches: A policy perspective. In B. McCormack & T. McCance (Eds.), Person-Centred practice in Nursing and health care: Theory and practice (p. 67). John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Gubrium, E., Harsløf, I., Lødemel, I., & Moreira, A. (2014). Norwegian activation reform on a wave of wider welfare state changes. In I. Lødemel & A. Moreira (Eds.), Activation or workfare? Governance and neo-liberal convergence (pp. 19–46). Oxford University Press.

- Hainmueller, J., Hofmann, B., Krug, G., & Wolf, K. (2016). Do lower caseloads improve the performance of public employment services? New evidence from German employment offices. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 118(4), 941–974. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12166

- Hamovitch, E. K., Choy-Brown, M., & Stanhope, V. (2018). Person-centered care and the therapeutic alliance. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(7), 951–958. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0295-z

- Hansen, H. C., & Natland, S. (2017). The working relationship between social worker and service user in an activation policy context. Nordic Social Work Research, 7(2), 101–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2016.1221850

- Hibbard, J. H., & Mahoney, E. (2010). Toward a theory of patient and consumer activation. Patient Education and Counseling, 78(3), 377–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2009.12.015

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Hudson, M., Phillips, J., Ray, K., Vegeris, S., & Davidson, R. (2010). The influence of outcome-based contracting on provider-led pathways to work. http://www.psi.org.uk/pdf/2010/rrep638.pdf

- Immervoll, H., & Knotz, C. (2018). How demanding are activation requirements for jobseekers. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 215. OECD Publishing.

- Jensen, P. H., & Pfau-Effinger, B. (2005). Active citizenship: The new face of welfare. In J. G. Andersen, A-M. Guillemard, P. H. Jensen &; B. Pfau-Effinger (Eds.), The changing face of welfare: Consequences and outcomes from a citizenship perspective (pp. 1–14). The Policy Press.

- Kahn, E. (1999). A critique of nondirectivity in the person-centered approach. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 39(4), 94–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167899394006

- Kass, J. D. (2017). A person-centered approach to psychospiritual maturation: Mentoring psychological resilience and inclusive community in higher education. https://link-springer-com.ezproxy.hioa.no/book/10.1007%2F978-3-319-57919-1

- Kluve, J., & Rani, U. (2016). A review of the effectiveness of active labour market programmes with a focus on Latin America and the Caribbean. ILO.

- Leplege, A., Gzil, F., Cammelli, M., Lefeve, C., Pachoud, B., & Ville, I. (2007). Person-centredness: Conceptual and historical perspectives. Disability and Rehabilitation, 29(20-21), 1555–1565. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280701618661

- Lewis, J., & Sanderson, H. (2011). A practical guide to delivering personalisation: Person-centred practice in health and social care. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Louw, J. M., Marcus, T. S., & Hugo, J. F. M. (2017). Patient- or person-centred practice in medicine? – A review of concepts. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 9(1), e1–e7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v9i1.1455

- Luck, L., Jackson, D., & Usher, K. (2006a). Case study: A bridge across the paradigms. Nursing Inquiry, 13(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1800.2006.00309.x

- Maximova-Mentzoni, T. (2019). Kvalifiseringstiltak for innvandrere og muligheter for supported employment [Labour market measures for migrants and opportunities for supported employment]. Søkelys på arbeidslivet, 36(01-02), 36–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-7989-2019-01-02-03

- McCance, T., & McCormack, B. (2010). Person-centred nursing: Theory and practice. Wiley-Blackwell.

- McCance, T., & McCormack, B. (2016). Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice In B. McCormack & T. McCance. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated.

- Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration. (2019a). Tiltak for å komme i jobb. [Employment schemes]. https://www.nav.no/no/Person/Arbeid/Oppfolging+og+tiltak+for+a+komme+i+jobb/Tiltak+for+a+komme+i+jobb

- Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration. (2019b). What is NAV? https://www.nav.no/en/Home/About+NAV/What+is+NAV

- Nothdurfter, U. (2016). The street-level delivery of activation policies: Constraints and possibilities for a practice of citizenship. European Journal of Social Work, 19(3-4), 420–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2015.1137869

- Nybom, J. (2011). Activation in social work with social assistance claimants in four Swedish municipalities. European Journal of Social Work, 14(3), 339–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2010.501021

- Parr, S. (2016). Conceptualising ‘the relationship’ in intensive key worker support as a therapeutic medium. Journal of Social Work Practice, 30(1), 25–42. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2015.1073146

- Pinto, M. (2019). Exploring activation: A cross-country analysis of active labour market policies in Europe. Social Science Research, 81, 91–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.03.001

- Renema, J. A. J., & Lubbers, M. (2019). Welfare-based income among immigrants in the Netherlands: Differences in social and human capital. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 17(2), 128–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1420276

- Richard, L. F., & Knis-Matthews, L. (2010). Are we really client-centered? Using the Canadian occupational performance measure to see how the client's goals connect with the goals of the occupational therapist. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 26(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01642120903515292

- Rogers, C. R. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications, and theory. Constable.

- Røysum, A. (2010). Nav-reformen: Sosialarbeidernes profesjon utfordres [Nav reform: Social worker profession is challenged]. Fontene Forskning, 1, 41–52.

- Sandqvist, J. L., & Henriksson, C. M. (2004). Work functioning: A conceptual framework. Work, 23(2), 147–157.

- Solvang, I. (2017). Discretionary approaches to social workers’ personalisation of activation services for long-term welfare recipients. European Journal of Social Work, 20(4), 536–547. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2016.1188777

- van Berkel, R., & Knies, E. (2018). The frontline delivery of activation: Workers’ preferences and their antecedents. European Journal of Social Work, 21(4), 602–615. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2017.1297774

- van Hal, L. B., Meershoek, A., Nijhuis, F., & Horstman, K. (2012). The ‘empowered client’ in vocational rehabilitation: The excluding impact of inclusive strategies. Health Care Analysis, 20(3), 213–230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-011-0182-z

- Waite, L. (2017). Asylum seekers and the labour market: Spaces of discomfort and hostility. Social Policy and Society, 16(4), 669–679. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746417000173

- Washburn, A. M., & Grossman, M. (2017). Being with a person in our care: Person-centered social work practice that is authentically person-centered. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 60(5), 408–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2017.1348419

- Waterhouse, R. L. (1993). Wild women don't have the blues: A feminist critique of ‘person-centred’ counselling and therapy. Feminism & Psychology, 3(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353593031004

- Waters, R. A., & Buchanan, A. (2017). An exploration of person-centred concepts in human services: A thematic analysis of the literature. Health Policy, 121(10), 1031–1039. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.09.003