ABSTRACT

As neoliberalisation and other global disruptions change the understanding of human rights and social justice for social workers, how are protests organised by marginalised groups against social welfare and public health regimes understood and participated, or even resisted, by social workers? Although there is a vast literature on protest and community organising in the social work tradition, there is less exploration of marginalised groups organising against the systems in which social workers are employed, thereby leading to dilemmas for social workers. Hence, more knowledge is necessary about social workers’ capability to respond to such protests.

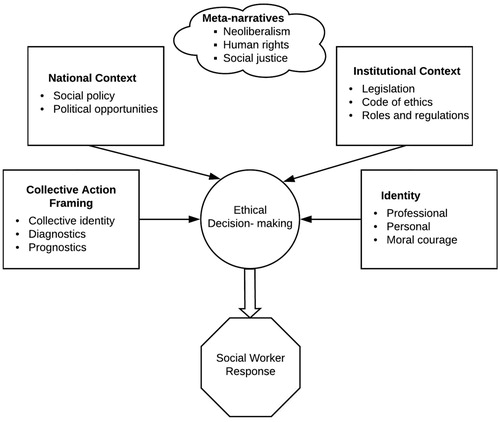

Using collective action and social movement theories, this paper introduces a conceptual framework in order to identify key factors and variables when marginalised groups organise against social welfare and public health regimes and social workers are involved. The conceptual framework concerns social workers’ value negotiation of human rights and social justice principles, collective action framing, ethical decision-making, and ultimately, the thought process behind a social worker’s response to collective actions against social welfare and public health regimes.

SAMMENDRAG

Nyliberalisme og andre globale utfordringer endrer forståelsen av menneskerettigheter og sosial rettferdighet for sosialarbeidere. Hvordan blir protest fra marginaliserte grupper mot velferds- eller folkehelseregimer forstått og deltatt i - eller også motarbeidet - av sosialarbeidere? Tross omfattende litteratur om protest og samfunnsarbeid i sosialt arbeid, er marginaliserte grupper som organiserer seg mot systemene sosialarbeidere er ansatt i – og dilemmaene dette fører til for sosialarbeidere – lite utforsket. Derfor er det behov for mer kunnskap om sosialarbeideres muligheter til å svare på slike protester.

Artikkelen bygger på teorier om sosiale bevegelser og kollektiv handling, og introduserer et begrepsmessig rammeverk for å identifisere sentrale faktorer og variabler når marginaliserte grupper organiserer seg mot velferd- og folkehelseregimer, der sosialarbeidere er involvert. Rammeverket omfatter sosialarbeidernes verdiforhandlinger knyttet til menneskerettigheter og prinsipper for sosial rettferdighet, forståelsesrammer etiske beslutningsprosesser, og til syvende og sist, tankeprosessen bak en sosialarbeiders respons på kollektive handlinger mot velferds- og folkehelseregimer.

Introduction

During the 2016 Joint World Conference on Social Work and Social Development, delegates gathered under the conference banner of ‘Promoting the Dignity and Worth of People.’ What was meant to be a conference to promote social inclusion became a controversy when attendees witnessed activists from Solidarity Against Disability Discrimination, a South Korean advocacy group, being dragged off the ceremony stage. The activists surprised attendees by entering onto the stage in wheelchairs with a protest banner and chanting slogans directed toward the South Korean Minister of Health, who himself was a speaker of the conference (Hardy, Citation2016). Only one of the more than 500 attendees raised objection against the treatment of the activists as it was occurring, although many people were shocked and upset after the session. Despite it being a violent spectacle, activists who were interviewed afterward said it was a successful protest because there was now greater attention for disability rights in South Korea.

The protest by disability rights activists from South Korea is an example of a collective action using disruptive tactics (Taylor & Van Dyke, Citation2007) against social welfare and public health regimes. The sombre response by conference attendees to the protest as it took place, unfortunately, is an example of social workers not living up to the social work ideals of social justice and human rights for marginalised groups (Collins, Citation2007; Dominelli, Citation2010; Ife, Citation2012; Lister, Citation1998; Reisch, Citation2016; Taylor & Van Dyke, Citation2007). While collective action brings focus to marginalised groups and their demands, there may be less attention given to the target of the collective action—in this case, social welfare and public health regimes—and the social worker’s thoughts and feelings about the collective action.

The two co-authors of this paper bore witness to collective actions in Oslo, Norway and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, respectively, under similar circumstances where marginalised groups organised against social welfare and public health regimes. We met at the 9th European Conference for Social Work and subsequently held several discussions about collective action by marginalised groups against social welfare and public health regimes to better understand it as a local and global phenomenon. This, in turn, led to several questions about social work ethics and the capability of social workers in different countries to appropriately respond to collective actions of this nature.

To be clear, what is meant by capability is the ability of social workers to make social justice and human rights-based decisions when marginalised groups—the people whom social workers are meant to help—organise collective action against social welfare and public health regimes that social workers are employed to uphold. The relevance of this issue is further suggested by the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused mass unemployment (Coibion et al., Citation2020) and service overload for social welfare and public health regimes throughout the world (Gentilini et al., Citation2020). Dissatisfied by the response from government and service providers, groups have taken to protest and dissent in several countries, including in the United States and Norway (Coibion et al., Citation2020; Dyer, Citation2020; Engelstad, Citation2020; Fairchild et al., Citation2020). This paper presents a conceptual framework for such circumstances, which the co-authors anticipate will serve as a foundation for theory development and data collection.

Developing a conceptual framework

Although there are a number of definitions for conceptual framework, we follow Carpiano and Daley (Citation2006), leading sociology and public health researchers who develop a specific definition based on a robust assessment of problems in theory development in the social sciences. According to their definition, creating a conceptual framework precedes the development of a theory. A conceptual framework functions to identify key factors and variables and the general relationship among each to account for a set of phenomena. A theory, on the other hand, takes the next step in developing hypotheses about the direction of relationships in a set of phenomena outlined by a conceptual framework (Carpiano & Daley, Citation2006).

The co-authors of this paper chose to develop a conceptual framework for several reasons. Much of the literature on collective action and the social work response focus on cases that are alone inadequate to understanding and explaining collective action by marginalised groups as a general phenomenon for social workers (Brady et al., Citation2014; Carey & Foster, Citation2011; Carr, Citation2007; Hardina et al., Citation2015; Mendes, Citation2002; Pyles, Citation2013; Strier & Bershtling, Citation2016). Second, few studies explore a cross-country perspective (Pyles, Citation2013; Weinberg & Banks, Citation2019), despite evidence of sharing global disruptions, such as neoliberalisation and the COVID-19 pandemic. The few existing studies do not share a common theory, let alone a conceptual framework. Lastly, there is much less research on collective action by marginalised groups that are organised against social welfare and public health regimes despite its’ reoccurrence (Carr, Citation2007; Lakeman & McGowan, Citation2007). Therefore, the aim of introducing a conceptual framework in this paper is to address these gaps.

Maxwell (Citation2013) names four main sources to develop components in a conceptual framework: one’s own experiential knowledge, existing theory and research, pilot and exploratory research, and thought experiments. Our framework mainly draws on existing theory and research, but we also use experiential knowledge and exploratory research in order to judge the relevance of concepts to include. This includes drawing on the second author’s experience as a social worker and ongoing study of immigrant shopkeepers’ collective action against a public health regime in Philadelphia, and drawing on the first author’s experience as a social worker and study of collective action among homeless people in Oslo (Aaslund, Citation2019; Aaslund and Seim Citation2020). Both projects yielded unexpected challenges in how to explain the social workers’ responses. In scrutinising differences and similarities in these cases, contextual differences appear to be important. To further refine the conceptual framework, thought experiments and social workers’ accounts of responses to current protests were used.

Gleaning insight from Armstrong and Bernstein’s (Citation2008) argument for a multi-institutional approach to social movement research, the conceptual framework considers collective action organised by marginalised groups against social welfare and public health regimes and the response by social workers as a phenomenon involving key factors and variables in micro, mezzo, and macro levels. Metanarratives and national context explain macro level factors, while institutional context explain mezzo level factors. Collective action framing and identity are sets of variables that explain individual thoughts, feelings, and decision making at the micro level. Although the three levels are distinct, the conceptual framework recognises macro and mezzo level factors as being more closely related than micro level factors. This is because the former is focused on ideology, policy, and organisations, while the latter is focused on individuals such as social workers and service users.

In addition to referring to existing literature, the co-authors use Norway and the United States as examples of how global comparison, or exploring the context of different countries, is achieved in the conceptual framework. Together, these key factors and variables make up the conceptual framework for theorising how social workers apply, or do not apply, social justice and human rights principles as a response to collective action organised by marginalised groups against social welfare and public health regimes.

Macro and mezzo levels: metanarratives, national context, and institutional context

Neoliberalisation

The practical challenges of aligning the needs and desires of marginalised groups as service users with service mandates and public policy are well known in social work (Lipsky, Citation1980). This mismatch between service users and services, not surprisingly, can lead to service user responses that range from a passive dissatisfaction that the service user does not verbalise, to the organising of collective action. There are concerns that neoliberalisation of services means an increasing likelihood of mismatch between service user needs and service provider objectives (Schram et al., Citation2010). The following is an overview of the ways in which collective action, a group level activity, can be understood in social work under neoliberalisation.

Iain Ferguson (Citation2017) argues new ways of ‘doing’ social justice in social work are often discovered in social movement, the aggregate of collective actions for a common cause which marginalised groups use to attain rights, recognition, and resources (Klandermans & Staggenborg, Citation2002; Staples, Citation2004). Alberto Melucci defines social movements as collective actions that express a conflict intended to breach system limits, and is characterised by solidarity, not merely the aggregate of individual actions (Citation1996). When social welfare or public health regimes become the reference system for such action, it leads to predicaments for a social worker. One predicament is when a social worker is asked to effectively turn onto themselves by breaching the system limits of social welfare and public health regimes in which they are employed.

At the same time, social work is being transformed by marketisation, managerialism (Ferguson, Citation2017), evidence-based practice, and New Public Management (Herz & Lalander, Citation2018; Kus, Citation2006; Wallace & Pease, Citation2011). Social work becomes vulnerable to co-optation for political aims that may disfavour the interests of marginalised groups in social welfare and public health regimes and therefore puts a constraint on a social worker’s ability to provide ethically sound services (Kojan et al., Citation2018; Lundberg et al., Citation2018; Spolander et al., Citation2014; Strier & Bershtling, Citation2016). This causes confusion for service users as to the objective of social welfare and public health regimes; that is, whether services are truly user-centred or otherwise, leading to conditions that stir collective action among marginalised groups. It also poses challenges to social workers, particularly role confusion, because the rules and regulations of service organisations become less aligned with human rights and social justice principles (Banks, Citation2013; Brady et al., Citation2014).

Neoliberalisation is conflicting for social workers and social welfare and public health regimes not because there is a clear ‘right and wrong’ but because in many cases there is not—at least in the view of its’ adopters (Ong, Citation2006). Take the traditionally non-competitive food banking system in Chicago, for example. The aims of the food banking system, to prevent hunger and engage in health promotion among the poor, took an unprecedent turn when institutional power throughout the metropolitan area was consolidated and services were commercialised. The outcome was a competitive food service delivery system that began charging user fees (Warshawsky, Citation2010).

Even seemingly progressive forms of collective action such as community organising are not immune to market logic schemas, where there is an increasing demand for evidence-based practice, efficiency, and commercialisation (Brady et al., Citation2014). This conflicts with human rights and social justice as integral parts of the global definition of social work (Healy & Link, Citation2012; Reisch, Citation2016) and therefore complicates social workers’ relationship with collective action organised by marginalised groups in local and global contexts. In other words, this is a situation in which neoliberalisation, and human rights and social justice become competing metanarratives (Chapman, Citation2016).

Human rights and social justice

Human rights and social justice go hand in hand (Wellman, Citation1987). They are both a set of principles concerning individual rights and social equality, yet with ongoing tension between the rights of individuals and collective interests (Reisch, Citation2016). Human rights and social justice promote closely resembled worldviews of a common humanity where individuals are obligated to help one another, but especially the vulnerable and oppressed. Beyond these similarities, however, there are important differences between human rights and social justice, such as in the United States and Norway, which ultimately affect how collective action occurs and how social workers respond to collective action.

United States

Social workers in the United States are expected to abide by the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics, an articulation of social justice principles and ethics for professional conduct (Citation2017). It defines who is oppressed and calls for action to address the immediate needs and long-term challenges of the oppressed. Reasons and arguments for social justice are based on the dictates and spirit of the United States Constitution (Reisch, Citation2016). Human rights are not domestic law; the United States, rather, limits its’ engagement in human rights to foreign policy. Activists find ways to combine social justice and human rights principles in the United States by creating organisations with a human rights framework, engaging in local and state level activism, and working as individuals (Reisch, Citation2016). Although the NASW Code of Ethics explicitly articulates social justice principles more than human rights principles, it certainly does not prohibit social workers from pursuing human rights.

Given the social welfare and public health landscape in the United States, where human rights is in the spirit of the law and social justice is articulated in the letter of the law, social workers and other activists use skills and resources in a strategic manner to effectively promote social justice and human rights together. Activists, for example, may take collective action and argue for the rights of undocumented residents by amplifying the spirit of the United States Constitution and how the United States is a historical beacon for the oppressed (Swerts, Citation2017). They may also articulate connection between United States foreign policy and social and economic instability in undocumented residents’ country of origin to formulate an argument that the United States bears responsibility for undocumented residents. Although these are persuasive arguments meant to appeal to the conscience of powerholders and the public, such arguments have relatively weak legal bearing.

Implementing human rights as domestic law in the United States, however, would have strong legal bearing. Access to human rights, in principle, is not limited by citizenship status, but entirely premised on being human. In addition to freedom of speech and freedom from discrimination, human rights include rights to healthcare, education, and protection from poverty—none of which are American constitutional mandates. Since human rights law is not yet available in the United States, social workers choose to promote human rights by alternative means.

University of Buffalo School of Social Work is well known for a mission statement that clearly articulates its’ adherence to human rights, for example (Androff, Citation2015). National Economic and Social Rights Initiative (NESRI) is a national, non-governmental organisation that leads organising campaigns and public policy development on the premise that access to healthcare, housing, and education are, in principle, human rights in the United States (Albisa & Sekaran, Citation2006). Political opportunities (McAdam et al., Citation1996; Snow et al., Citation2005) to introduce human rights and promote social justice in the United States remains closer at the local level, but it is creating the foundation for change at the national level.

Norway

Human rights and social justice are institutionalised in Norwegian social work. The Norwegian Allied Association of Child Welfare Pedagogues, Social Workers and Health Social Workers (FO) has a code of professional ethics based on human rights and social justice. It refers to the United Nations (UN) Declaration of Human Rights and Children’s Convention, as well as the International Federation of Social Work (IFSW) Statement of Ethical Principles (Keeney et al., Citation2014). The code of professional ethics promotes values of solidarity and social equality such as the fair allocation of society’s resources, fighting discrimination, and loyalty to service users, organisations, politicians and the public.

When there is conflict between the aforementioned parties, the code of professional ethics states that loyalty is foremost with the most vulnerable party, although it does not explain how a social worker should take context into account (Stjernø, Citation2013)—for example, if the nature of the conflict is collective action such as service user protests against service organisations. Since social work is not a licenced profession in Norway, there are debates about how to ensure fidelity to the code of professional ethics, and whether it is applicable to social workers who not members of FO.

Unlike the United States, Norway ratified and implemented the following UN Conventions: Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR); Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR); Against Racial Discrimination (ICERD); Against Torture (UNCAT); Against Discrimination of Women (CEDAW); Rights of Children (UNCRC); Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP); Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). Norway has also adopted the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Several of the rights from the conventions are incorporated into Norwegian domestic legislation. Therefore, Norway is monitored by European Union (EU) and UN human rights committees. Although Norway ranks among countries with the best human rights records, it has faced criticism for the use of solitary confinement in prisons and excessive force against users in psychiatric institutions.

Social justice, on the other hand, is promoted by the Nordic welfare state through universal social rights (Hutchinson, Citation2009). Social workers who worked for the state were once seen as arbiters of social policy that ensured social rights through their direct practice with service users. However, critiques of a paternalistic welfare state appeared in the 1980s that changed this (Christiansen & Markkola, Citation2006). Rising unemployment and people depending on social assistance gave rise to workfare and New Public Management policies that, in turn, spurred organising among the unemployed and poor people’s movements (Lødemel & Trickey, Citation2001). More recently, refugees and the opening of borders to EU migrant workers has led to contention about the availability of health and social services to migrants (Lundberg et al., Citation2018), which has spurred collective actions.

In the Nordic countries, marginalised groups have taken advantage of political opportunities by choosing a strategy of cooperation with professionals (Andreassen, Citation2004, Citation2006; Anker, Citation2009; Eriksson, Citation2018a) compared to, for example, the large amount of protests among the homeless in the US (Cress & Snow, Citation2000; Snow et al., Citation2005). This is explained by the Nordic countries having well-established corporate organisations that propagate the idea that marginalised people are in a position of larger gains from cooperating rather than from confrontation. Additionally, there are concerns that service organisations are under the influence of such propagation and now reinforce its’ messaging, which downplays collective action as a choice even when it is an optimal one for marginalised groups (Andreassen, Citation2004; Eriksson, Citation2018b).

Micro level: collective action framing and identity

Collective action framing

Collective action research tends to exist separately between Europe and the United States. American collective action scholars have focused on mobilising resources and political processes and conditions to explain the emergence of social movements (Benford & Snow, Citation2000; Cress & Snow, Citation2000; Piven & Cloward, Citation1979; Snow, Citation2004), while European scholars have focused on cultural conditions, such as conflict between identities and lifestyles (Calhoun, Citation1995; Diani, Citation1992; Melucci, Citation1996; van Stekelenburg & Roggeband, Citation2013). Within social work research, the study of collective action tends to focus on the social movement aspects of community organising and community development (Ife, Citation2012; Ledwith, Citation2011; Pyles, Citation2013; Staples, Citation2004). Present social work literature provides important insight into movement building and processes but tends to say less about spontaneous and short instances of collective action which may increasingly occur as a result of neoliberalisation and global disruptions.

Several authors argue that establishing fixed identities is a fundamental task of collective action strategy. Collective action actors accomplish this through boundary work that formulates a dichotomy such as ‘us versus them’ or ‘victim and oppressor.’ This is the basic process of collective action framing (Diani, Citation2013; Snow, Citation2013; Taylor, Citation2013; Taylor & Whittier, Citation1992). Indeed, framing is an integral part of the collective process where identities are not only established, but where targets, goals, and objectives become delineated, too (Benford & Snow, Citation2000; Melucci, Citation1995).

However, there has been a growing trend to conceptualise identities as fluid rather than fixed, and this brings an added layer of complexity in the use of identity to establish adversarial boundaries for collective action (Bauman, Citation2000; van Stekelenburg & Roggeband, Citation2013). In fact, recent social movements have emerged whose primary aim is the deconstruction of fixed identities, making the role of identities for collective action even more complex (Gamson, Citation1995). Additionally, the process of framing includes ‘diagnostics’ to identify the main problem or target for collective action and ‘prognostics’ in order to formulate strategies and solutions (Cress & Snow, Citation2000).

Identity

Whether a social worker supports or does not support a collective action will depend on, among other things, a negotiation between collective action framing, professional identity, and personal identity (Klandermans, Citation2013a). As a professional, there are a number of roles that a social worker can choose to support a collective action by marginalised groups: activist, mobiliser, facilitator, or advocate (Hutchinson, Citation2009). Each role, from activist to advocate, can be thought of as running along a spectrum where the former represents the closest involvement while the latter represents the furthest involvement in collective action (Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001).

A social worker choosing a role of support to collective action not only runs the risk of conflict with social welfare and public health regimes, but it also runs the risk of causing conflict with social work colleagues and others with whom there is a personal relationship. Therefore, a social worker’s personal identity and personal relationships may determine the support role they choose, or if they choose to not support a collective action by marginalised groups at all.

From a cognitive perspective, both a social worker’s professional identity and personal identity offer elements of internal motivation: feeling important, solidarity, social contact, self-realisation, and respect (Klandermans, Citation2013b; Olsson, Citation1999). The level of participation in collective action is contingent upon the extent to which these are fulfilled (Ganz, Citation2011; Simon & Klandermans, Citation2001). If a social worker decides to participate in a collective action, it can be understood from an ethical perspective of identity negotiation where the social worker is acting with moral courage. Strom-Gottfried defines this as when a social worker accepts challenges despite the risk of jeopardising their own reputation or well-being (Citation2014). In summary, although professional and personal identity are distinct forms of identity, they share characteristics that are negotiated by social workers to determine a response to collective action by marginalised groups.

Discussion

The protest at the 2016 Joint World Conference, which we referred to in the introduction, is only one of many incidents to suggest a complex relationship between human rights and social justice, and the social worker response to collective action by marginalised groups. The COVID-19 pandemic and the response by government and service providers has led to protests and dissent in several countries by service users of social welfare and public health, indicating a need for social workers to understand collective action as an interconnected, global phenomenon.

Although social justice and human rights are universalist principles, there are also national and local dimensions, which our comparison between Norway and the United States suggests. Differences in legal frameworks and welfare state adherence to human rights and social justice creates different political opportunities for collective action and the framing of collective action (McAdam et al., Citation1996). Human rights as law and the codification of human rights in a social work code of ethics encourages social workers to support collective action by marginalised groups. On the other hand, neoliberalisation may delegitimise collective action by marginalised groups, which discourages social workers from endorsing organised protest. Our conceptual framework, as shown in , maps the key factors and variables in these complex relationships, which has both usefulness and limitations.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework: social worker response to protest by marginalised groups against social welfare and public health regimes.

By referring to collective action and social movement theories, we acknowledge structural and social constructivist approaches that connect structural constraints and possibilities with an understanding of agency and reflexivity. Theoretical contributions from collective action theory broadens our understanding of social workers and the multiple roles they can choose such as enabler, bystander, or opponents. Our recognition of political opportunity and neoliberalism shows how human rights and social justice can form the basis for strategic resistance, but also how it can be manipulated and used against marginalised groups. By recognising national context, the conceptual framework is well fitted to study social worker responses to collective action by marginalised people across different political systems and welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990). The conceptual framework is useful for a wide range of research methods such as fieldwork, surveys, historical studies, and interviews (Diani & Eyerman, Citation1992).

Like any conceptual framework, it is a simplification of reality which will necessarily omit some aspects or concepts. It does not fully capture the complex relationships regarding social workers and collective actions. Issues such as representation, resource mobilisation, and grievances from social movement theory are not touched upon. Neither are theories about empowerment, decolonisation, or professional skills from the social work tradition. Our conceptual framework is a first step towards building a sound theoretical base for social workers responses to collective action by marginalised groups. Empirical research will necessarily lead to modifications or amendments. To our knowledge, this is one of the first conceptual frameworks introduced to a scarcely examined topic. Therefore, it enhances our understanding of human rights and social justice as tools for social workers.

Conclusion

Collective action, such as community organising and protests, is not a strange concept to social work. Additionally, the discourse on social work ethics is rich and remains a core subject in the discipline. Both collective action and social work ethics claim a history in social work that spans decades. Yet, our understanding of collective action and social work ethics together remains underdeveloped, especially when it pertains to collective action by marginalised groups against social welfare and public health regimes. Most studies are in-depth examinations of local occurrences of collective action and some may refer to the consequence of neoliberalisation and global disruptions, but almost no studies conduct cross-country comparisons.

If social work as a discipline intends to lead the discourse on human rights and social justice in direct practice with marginalised individuals, then it must develop robust scholarship that accounts for marginalised groups’ organised protest in local, national, and global contexts. The conceptual framework in this paper attempts to lay groundwork for theory building, data collection, and analysis of a multi-level, cross-country context. It suggests key factors and variables which we anticipate will guide the formative stage of a research agenda seeking to understand collective action organised by marginalised groups against social welfare and public health regimes, as well as a social worker’s fidelity to social justice and human rights in response to collective demands.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Håvard Aaslund is a PhD student at Oslo Metropolitan University, Norway and a lecturer at VID Specialized University. His research area concerns user participation, homelessness, marginalization, mobilization, action research, and social work education.

Charles Chear is a PhD student at the School of Social Work, Rutgers University, United States. His research area concerns work, care, and urban informality, particularly of immigrant children and families working in small business.

References

- Aaslund, H. (2019). Fra «Brukermedvirkning» til «Demokrati» –språkets betydning i deltakende aksjonsforskning [From “User Involvement” to “Democracy” – the meaning of language in participatory action research]. In O. P. Askheim, I. M. Lid, & S. Østensjø (Eds.), Samproduksjon i forskning. Forskning med nye aktører [Co-production in Research. Research with New Agents]. (pp. 111–129). https://doi.org/10.18261/9788215031675-2019

- Aaslund, H., & Seim, S. (2020). ‘The long and winding road’ — collective action among people experiencing homelessness. International Journal of Action Research, 16(2), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.3224/ijar.v16i2.02

- Albisa, C., & Sekaran, S. (2006). Realizing domestic social justice through international human rights. NYU Rev. L. & Soc. Change, 30, 351–352.

- Andreassen, T. A. (2004). Brukermedvirkning, politikk og velferdsstat [User Involvement, Policy, and Welfare State]. (Dr. polit. thesis). University of Oslo.

- Andreassen, T. A. (2006). Truet frivillighet og forvitrede folkebevegelser? En diskusjon av hva perspektiver fra studier av sosiale bevegelser kan tilføre forskningen om frivillige organisasjoner [Threatened volunteerism and weathered popular movements? A discussion of what perspectives from social movement studies can add to research about voluntary organisations]. Sosiologisk tidsskrift [Journal of Sociology], 14(2), 146–170. http://www.idunn.no/st/2006/02/truet_frivillighet_og_forvitrede_folkebevegelser_en_diskusjon_av_hva_perspe.

- Androff, D. (2015). Practicing rights: Human rights-based approaches to social work practice. Routledge.

- Anker, J. (2009). Speaking for the homeless–opportunities, strengths and dilemmas of a user organisation. European Journal of Homelessness, 3, 275–288.

- Armstrong, E. A., & Bernstein, M. (2008). Culture, power, and institutions: A multi-institutional politics approach to social movements. Sociological Theory, 26(1), 74–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2008.00319.x

- Banks, S. (2013). Negotiating personal engagement and professional accountability: Professional wisdom and ethics work. European Journal of Social Work, 16(5), 587–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2012.732931

- Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid Modernity. Polity Press.

- Benford, R. D., & Snow, D. A. (2000). Framing processes and social movements: An overview and assessment. Annual Review of Sociology, 26(1), 611–639. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611

- Brady, S., Schoeneman, A., & Sawyer, J. (2014). Critiquing and analyzing the effects of neoliberalism on community organizing: Implications and recommendations for practitioners and educators. Journal of Social Action in Counseling and Psychology, 6(1), 36–60. https://doi.org/10.33043/JSACP.6.1.36-60

- Calhoun, C. J. (1995). Social theory and the politics of identity. In C. J. Calhoun (Ed.), Critical social theory: Culture, history, and the challenge of difference (pp. 9–36). Blackwell Publishers.

- Carey, M., & Foster, V. (2011). Introducing ‘deviant’ social work: Contextualising the limits of radical social work whilst understanding (fragmented) resistance within the social work labour process. British Journal of Social Work, 41(3), 576–593. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq148

- Carpiano, R. M., & Daley, D. M. (2006). A guide and glossary on post-positivist theory building for population health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(7), 564–570. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.031534

- Carr, S. (2007). Participation, power, conflict and change: Theorizing dynamics of service user participation in the social care system of England and Wales. Critical Social Policy, 27(2), 266–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018306075717

- Chapman, A. R. (2016). Global health, human rights, and the challenge of Neoliberal policies. Cambridge University Press.

- Christiansen, N. F., & Markkola, P. (2006). Introduction. In N. F. Christiansen, K. Petersen, N. Edling, & P. Haave (Eds.), The Nordic model of welfare: A historical reappraisal (pp. 9–30). Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Coibion, O., Gorodnichenko, Y., & Weber, M. (2020). Labor markets during the covid-19 crisis: A preliminary view (0898-2937).

- Collins, S. (2007). Some critical perspectives on social work and collectives. The British Journal of Social Work, 39(2), 334–352. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm097

- Cress, D. M., & Snow, D. A. (2000). The outcomes of homeless mobilization: The influence of organization, disruption, political mediation, and framing. American Journal of Sociology, 105(4), 1063–1104. https://doi.org/10.1086/210399

- Diani, M. (1992). Analysing social movement networks. In M. Diani & R. Everman (Eds.), Studying collective action (Vol. 105, pp. 107-135). Sage Publications.

- Diani, M. (2013). Organizational fields and social movement dynamics. In J. van Stekelenburg, C. Roggeband, & B. Klandermans (Eds.), Dynamics, mechanisms, and processes. The future of social movement research (pp. 145–168). Univeristy og Minnesota Press.

- Diani, M., & Eyerman, R. (1992). Studying collective action (Vol. 30). SAGE Publications Limited.

- Dominelli, L. (2010). Social work in a globalizing world. Wiley.

- Dyer, O. (2020). Covid-19: Trump stokes protests against social distancing measures. BMJ, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1596

- Engelstad, E. (2020). Norway’s workers insisted they shouldn’t pay for coronavirus — and they won. Jacobin. https://jacobinmag.com/2020/03/coronavirus-norway-workers-sick-pay-social-democracy.

- Eriksson, E. (2018a). Four features of cooptation. Nordisk Välfärdsforskning | Nordic Welfare Research, 3(01), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2464-4161-2018-01-02 ER

- Eriksson, E. (2018b). Incorporation and individualization of collective voices: Public service user involvement and the user movement’s mobilization for change. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29(4), 832–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-018-9971-4

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton University Press.

- Fairchild, A., Gostin, L., & Bayer, R. (2020). Vexing, veiled, and inequitable: Social distancing and the “rights” divide in the age of COVID-19. The American Journal of Bioethics, 20(7), 55–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2020.1764142

- Ferguson, I. (2017). Hope over fear: Social work education towards 2025. European Journal of Social Work, 20(3), 322–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2016.1189402

- Gamson, J. (1995). Must identity movements self-destruct? A queer dilemma. Social Problems, 42(3), 390–407. https://doi.org/10.2307/3096854

- Ganz, M. (2011). Public narrative, collective action, and power. In S. Odugbemi, & T. Lee (Eds.), Accountability through public opinion: From inertia to public action (pp. 273–289). The World Bank.

- Gentilini, U., Almenfi, M., Orton, I., & Dale, P. (2020). Social Protection and Jobs Responses to COVID-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33635.

- Hardina, D., Jendian, M. A., & White, C. G. (2015). Tactical decision-making: Community organizers describe ethical considerations in social action campaigns.(Report). Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 42(1), 73–94.

- Hardy, R. (2016, June 28). Disabled activists condemn treatment at social work conference The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/social-care-network/2016/jun/28/disabled-activists-condemn-treatment-social-work-conference.

- Healy, L. M., & Link, R. J. (2012). Handbook of international social work: Human rights, development, and the global profession. Oxford University Press.

- Herz, M., & Lalander, P. (2018). Neoliberal management of social work in Sweden. In M. Kamali, & J. H. Jönsson (Eds.), Neoliberalism, Nordic welfare states and social work: Current and future challenges (pp. 57–66). Routledge.

- Hutchinson, G. S. (2009). The mandate for community work in the Nordic welfare states. In G. S. Hutchinson (Ed.), Community work in the Nordic countries. Universitetsforlaget.

- Ife, J. (2012). Human rights and social work: Towards rights-based practice (pp. 15–37). Cambridge University Press.

- Keeney, A., Smart, A., Richards, R., Harrison, S., Carrillo, M., & Valentine, D. (2014). Human rights and social work codes of ethics: An international analysis. Journal of Social Welfare and Human Rights, 2(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15640/jswhr.v2n2a1

- Klandermans, B. (2013a). Demand and supply of protest. In D. A. Snow, D. Della Porta, B. Klandermans, & D. McAdam (Eds.), The Wiley-blackwell encyclopedia of social and political movements (pp. 326–327). Wiley-Blacwell.

- Klandermans, B. (2013b). The Dynamics of demand. In B. Klandermans, J. van Stekelenburg, & C. Roggeband (Eds.), The future of social movement research (pp. 3–16). University of Minnesota Press.

- Klandermans, B., & Staggenborg, S. (2002). Methods of social movement research. University of Minnesota Press.

- Kojan, B. H., Marthinsen, E., Moe, A., & Skjefstad, N. S. (2018). Neoliberal reframing of user representation in Norway. In M. Kamali, & J. H. Jönsson (Eds.), Neoliberalism, Nordic welfare States and social work (pp. 109–118). Routledge.

- Kus, B. (2006). Neoliberalism, institutional change and the welfare state: The case of Britain and France. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 47(6), 488–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020715206070268

- Lakeman, R., & McGowan, P. (2007). Service users, authority, power and protest: A call for renewed activism. Mental Health Practice (Through 2013), 11(4), 12–16. https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp2007.12.11.4.12.c6332

- Ledwith, M. (2011). Community development: A critical approach. Policy Press.

- Lipsky, M. (1980). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lister, R. (1998). Citizenship on the margins: Citizenship, social work and social action. European Journal of Social Work, 1(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691459808414719

- Lødemel, I., & Trickey, H. (2001). ‘An offer you can’t refuse’: Workfare in international perspective. Policy Press.

- Lundberg, A., Gruber, S., & Righard, E. (2018). Brandväggar och det sociala arbetets professionsetik [Fire walls and social work professional ethics]. In M. Dahlseth, & P. Lalander (Eds.), Manifest: för ett socialt arbete i tiden [Manifest for a Timely Social Work] (pp. 291–302). Studentlitteratur.

- Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach. SAGE Publications.

- McAdam, D., McCarthy, J. D., & Zald, M. N. (1996). Introduction: Opportunities, mobilizing structures, and framing processes. In D. McAdam, J. D. McCarthy, & M. N. Zald (Eds.), Comparative perspectives on social movements: Political opportunities, mobilizing structures, and cultural framings (pp. 1–20). Cambridge University Press.

- Melucci, A. (1995). The process of collective identity. In H. Johnston, & B. Klandermans (Eds.), Social movements and Culture (pp. 41–63). UCL Press.

- Melucci, A. (1996). Challenging codes: Collective action in the information age. Cambridge University Press.

- Mendes, P. (2002). Social workers and the ethical dilemmas of community action campaigns: Lessons from the Australian State of Victoria. Community Development Journal, 37(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/37.2.157

- National Association of Social Workers. (2017). NASW Code of Ethics. https://www.socialworkers.org/About/Ethics/Code-of-Ethics/Code-of-Ethics-English.

- Olsson, L.-E. (1999). Från idé till handling: en sociologisk studie av frivilliga organisationers uppkomst och fallstudier av Noahs Ark, 5i12-rörelsen, Farsor och morsor på stan [From Idea to Action: A Sociological Study of Voluntary Organizations’ Origin and Case Studies of Noahs Ark, the 5in12-movement, Dads and Mums Downtown]. Almqvist & Wiksell International.

- Ong, A. (2006). Neoliberalism as exception: Mutations in citizenship and sovereignty. Duke University Press.

- Piven, F. F., & Cloward, R. (1979). Poor people’s movements: Why they succeed, how they fail. Vintage.

- Pyles, L. (2013). Progressive community organizing: Reflective practice in a globalizing world. Taylor & Francis.

- Reisch, M. (2016). Social work and social justice: Concepts, challenges, and strategies. Oxford University Press.

- Schram, S. F., Soss, J., Houser, L., & Fording, R. C. (2010). The third level of US welfare reform: Governmentality under neoliberal paternalism. Citizenship Studies, 14(6), 739–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2010.522363

- Simon, B., & Klandermans, B. (2001). Politicized collective identity: A social psychological analysis. American Psychologist, 56(4), 319. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.4.319

- Snow, D. A. (2004). Framing processes, ideology, and discursive fields. In D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule, & K. Hanspeter (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to social movements (Vol. 1, pp. 380-412). Blackwell.

- Snow, D. A. (2013). Identity dilemmas, discursive fields, identity work, and mobilization. Clarifying the identity–movement Nexus. In J. van Stekelenburg, C. Roggeband, & B. Klandermans (Eds.), The Future of social movement research (pp. 263–280). University of Minnesota Press.

- Snow, D. A., Soule, S. A., & Cress, D. M. (2005). Identifying the precipitants of homeless protest across 17 US cities, 1980 to 1990. Social Forces, 83(3), 1183–1210. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2005.0048

- Spolander, G., Engelbrecht, L., Martin, L., Strydom, M., Pervova, I., Marjanen, P., Tani, P., Sicora, A., & Adaikalam, F. (2014). The implications of neoliberalism for social work: Reflections from a six-country international research collaboration. International Social Work, 57(4), 301–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872814524964

- Staples, L. (2004). Roots to power: A manual for grassroots organizing. Praeger.

- Stjernø, S. (2013). Profesjon og solidaritet [Profession and solidarity]. In A. Molander & J. C. Smedby (Eds.), Profesjonsstudier [Studies of Professions] (Vol. 2, pp. 130–143). Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

- Strier, R., & Bershtling, O. (2016). Professional resistance in social work: Counterpractice assemblages. Social Work, 61(2), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/sww010

- Strom-Gottfried, K. (2014). Straight talk about professional ethics. Oxford University Press.

- Swerts, T. (2017). Creating space for citizenship: The liminal politics of undocumented activism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(3), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12480

- Taylor, V. (2013). Social movement participation in the global society. Identity, networks, and emotions. In J. van Stekelenburg, C. Roggeband, & B. Klandermans (Eds.), The Future of social movement research (pp. 37–58). University of Minnesota Press.

- Taylor, V., & Van Dyke, N. (2007). ‘Get up, stand up’: Tactical repertoires of social movements. In D. A. Snow, S. A. Soule, & H. Kriesi (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to social movements (pp. 262–293). Blackwell Publishing.

- Taylor, V., & Whittier, N. E. (1992). Collective identity in social movement communities: Lesbian Feminist mobilization. In J. Freeman, & V. Johnson (Eds.), Waves of protest: Social movements since the sixties (pp. 169–194). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers Inc.

- van Stekelenburg, J., & Roggeband, C. (2013). Introduction. In J. van Stekelenburg, C. Roggeband, & B. Klandermans (Eds.), The future of social movement research (pp. xi–xxii). University of Minnesota Press.

- Wallace, J., & Pease, B. (2011). Neoliberalism and Australian social work: Accommodation or resistance? Journal of Social Work, 11(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017310387318

- Warshawsky, D. N. (2010). New power relations served here: The growth of food banking in Chicago. Geoforum, 41(5), 763–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.04.008

- Weinberg, M., & Banks, S. (2019). Practising ethically in unethical times: Everyday resistance in social work. Ethics and Social Welfare, 13(4), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2019.1597141

- Wellman, C. (1987). Social justice and human rights. Persona & Derecho, 17, 199.