ABSTRACT

The starting point of this article is an interest in understanding what happens when the concept of evidence-based practice (EBP) travel between countries. Understanding knowledge as something constructed between actors who shape and trade ideas and experiences, the aim is to study how EBP has been received, interpreted and practised in Swedish social work in comparison to some of the other Nordic welfare states. This is done through a scoping study literature review of research on evidence-based practice (EBP) in Swedish social work within the Swedish welfare system. The review shows that two research units (CUS and IMS) at the public authority National Board of Health and Welfare have had significant influence on the travelling of EBP to Sweden. Further, the review shows that a guideline-model version of EBP has been given priority in the diffusion process. The results also show that the interest in EBP among managers has increased over the past few years, and that their attitude toward the concept is generally positive. At the same time Swedish social workers rarely make use of research in their work, seldom use evidence-based methods, and seems to be unsure of the meaning of the concept.

SAMMANFATTNING

Utgångspunkten för denna artikel är ett intresse i att förstå vad som händer när evidensbaserad praktik (EBP) som begrepp reser mellan länder. Genom att förstå kunskap som något konstruerat mellan olika aktörer som skapar och förhandlar idéer och erfarenheter syftar artikeln att studera hur EBP har blivit mottagen, tolkad och utövad i svenskt socialt arbete i jämförelse med några av de andra nordiska välfärdsstaterna. Detta är genomfört genom en omfångsstudie av publicerad forskning EBP i socialt arbete i Sverige. Översikten visar att två forskningsavdelningar (CUS och IMS) hos den statliga myndigheten Socialstyrelsen har haft stor betydelse i införandet av EBP till Sverige. Dessutom visar översikten att riktlinje-versionen av EBP har getts företräde i spridningen. Resultaten pekar också mot att intresset hos gruppledare och chefer har ökat under de senaste åren, och att deras attityd gentemot EBP, generellt är positiv. Samtidigt använder sällan svenska socialarbetare forskning i sitt arbete eller evidensbaserade metoder och tycks även vara osäker på begreppets betydelse.

NYCKELORD:

Introduction

The concept of evidence-based practice (EBP) emanates from the medical field (Sackett et al., Citation2000). Hübner (Citation2016) suggests that EBP in social services should be understood as a vehicle or model for knowledge management. This means that the concept of EBP not only refers to what should be understood as valid knowledge, but also to how such knowledge should be produced, as well as to how it should be integrated into social work practice as a process and a product. How best to understand EBP, as well as its benefits and drawbacks when used in social work practice, has been widely discussed internationally (see e.g. Gray et al., Citation2009; Mullen & Streiner, Citation2004; Nevo & Slonim-Nevo, Citation2011; Soydan, Citation2014).

According to Vedung (Citation2010) the EBP movement is the successor of a wave of interest among public authorities in the evaluation of welfare interventions, which began in the USA as early as the 1960s. Important influences for the thinking about EBP have probably also come from the New Public Management movement, a model for organizing the public sector that was introduced in public administration at the end of the 1980s.

The EBP movement originated in the USA, and as the concept has spread attempts have been made to implement it in Human Service Organizations in Sweden and many other countries in Europe, such as the UK and the Nordic countries. To understand how the concept of EBP has been differently implemented in different countries, it is helpful to make use of theories concerning how ideas ‘travel’ between countries. The choice of the term ‘travel’, rather than ‘transfer’ in this case highlights that ‘knowledge’ is socially constructed in human interaction between actors that are involved in shaping and trading ideas and experiences with each other (cf. Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996).

It has been suggested that some conditions are particularly important when understanding how concepts like EBP travel. One is that concepts/ideas like EBP transform, to a greater or lesser extent, when they travel. We suggest that this is due to the inherently constructive and plastic nature of language, which refracts the world rather than reflecting it in an objective depiction (cf. Berger & Luckmann, Citation1966). Therefore, actors make different interpretations of the meaning of ideas as they spread.

Another important condition for understanding how concepts like EBP change when travelling, is that the travel can be facilitated or hampered by boundaries that exist on a conceptual level due, for instance, to history, society, and culture (Harris et al., Citation2015). For instance, boundaries can be explained by the institutional contexts where ideas and methods are implemented, and by how these contexts have different needs and are also susceptible to change (Czarniawska & Joerges, Citation1996). This means that the transformation of concepts like EBP can be attributed to the special needs of the receiving institution, such as an R&D organization on a national level, and the tasks to be performed (see e.g. DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983).

It has also been argued that knowledge travels in the forms of narratives, which could mean that plots, connections between objects, and the ‘moral of the story’ or conclusions that should be drawn from the content of the narrative, are tied to the narrative and thus are less negotiable than ideas that are not embedded in a narrative structure. Another important factor for understanding how concepts travel is the routes they take. The concept of routes can be defined as ‘the interwoven spatial and social dimensions in the travelling of knowledge’ (Harris et al., Citation2015, p. 488). Such routes are dependent on different factors, such as the fact that people from some countries (e.g. the UK and the Nordic Countries) tend to direct their interest towards, travel to, and create contacts at conferences and other events where the English language is dominant, and are influenced by thoughts produced in western welfare countries (cf. Kessl & Evans, Citation2015). This leads to another important condition for understanding how concepts like EBP travel, namely the dominant position that US actors, as producer, carriers or providers of ideas, models and methods in connection to social work, have in relation to other western welfare countries (Sahlin-Andersson, Citation2001). For the development of social work in Sweden as well as in other Nordic countries, the impact of this has been quite substantial both on social work methods and the spreading of EBP in social work (Bergmark et al., Citation2011).

Given the differences that exist between the United States and Europe, and the Nordic countries in particular, in terms of the development of social work as a profession and organizational and legislative factors, it can be expected that, as a device for knowledge management, EBP has been received, interpreted and practised differently in the countries to which it has travelled.

Based on this, our aim is to study how EBP has been received, interpreted and practised in Swedish social work in comparison to some of the other Nordic welfare states employing what often is called the Scandinavian/Nordic welfare model. To accomplish this a scoping study review has been carried out to investigate how the EBP concept has been described, criticized, and debated in Swedish social work during the period 1998–2020.

The reception of evidence-based social work in other Nordic countries

In a comparative study of why demands to implement EBP in social work have been much more strongly articulated by public authorities and other proponents in Sweden than in Finland, Hübner (Citation2016) suggests that some factors have been particularly important for the different interpretations of the EBP movement in Finland and Sweden. Hübner (Citation2016) contends that the EBP movement’s lack of influence on authorities, and the length of education of social workers in Finland, alongside a high level of confidence in their academic skills, can explain why it has never gained strong support in Finland.

In Sweden, as will be shown in more detail later in the article, representatives of central authorities were important drivers of the EBP movement. Arguing for the importance of implementing EBP, the Director of the National Board of Health and Welfare basically claimed that social work was being performed without knowledge about the effects of the methods used, thereby reducing social workers’ ability to do a professional job (see Wigzell & Pettersson, Citation1999). In Finland, however, the authorities made no such claims or demands for change regarding EBP in social work. This was partly due to the lack of connections between Finnish researchers and officials on the one hand and proponents of the EBP movement on the other, and partly due to Finnish social workers being trusted to be able to do a professional job. The latter is attributed by Hübner to Finnish social workers’ longer education (master’s degree) which includes a strong emphasis on academic skills.

In Denmark, EBP has taken a different path in social work. It was initiated by a Danish researcher who, in 2002, took from abroad the idea of forming a Campbell centre (Elvbakken & Hansen, Citation2019; Hansen & Rieper, Citation2010). At first, the centre was housed at the National Institute for Social Research (SFI) and after a few years it was granted permanent funding. Since then the name has changed to SFI Campbell, and it is now hosted at the Danish VIVI Effect Measurement Department and addresses questions of social policy and welfare. Today the emphasis is more on ‘knowledge that works’ than on its original aim of performing Randomized Control Studies (RCT). This change in focus coincides with changes in the Danish Health and Welfare authorities (Socialstyrelsen), which have led to influential proponents of the EBP idea on managerial level gradually moving to other positions. Since the economic crisis/recession of 2009, there has been an increased interest in public spending and ‘knowledge gaps in social services and the costs of various interventions’ (Elvbakken & Hansen, Citation2019, p. 266), which seems to fit with the current location of the Campbell centre. Concerning the question of how EBP ideas travel between fields of policy Elvbakken and Hansen (Citation2019) suggest that the existing division between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Social Affairs explains why both research institutes Cochrane’s and Campbell’s activities have remained separate. The authors also suggest that the fact that Campbell’s proponents no longer have leading positions in governmental research units, the already mentioned change in leadership in the Danish Health and Welfare authorities, and the criticism of RCT by social workers have been contributing factors in why the evidence movement has not achieved strong institutionalization. The authors also predict that the Campbell unit in Denmark might face difficulties in getting funding in the future.

In relation to the development of EBP in Denmark, Hansen and Rieper (Citation2010) suggest that the institutionalization process was driven by normative pressure and an idea of what can be characterized as global knowledge in the field of social work. However, their analysis also shows that when travelling outside the medical field, EBP was confronted with other research/evaluative ideals, which led to the Nordic Campbell centre in Denmark being challenged by researchers and also recommended by agency officials to broaden their research methods to include other methods than meta-studies. The authors also suggest that the Campbell methodology was formed on the basis of the Cochrane methodology ‘in a mimetic process’, but that the progression led to the Campbell centre developing and a broadening the methodological approach.

In a comparison of Denmark and Norway, Elvbakken and Hansen (Citation2019) find that there are some significant differences between how the concept of EBP has travelled to the countries. One similarity, the authors argue, is that in both countries the evidence movement has had difficulty getting resources and support outside of the medical field. Significant differences that can be detected in the authors’ comparison is that EBP has not been as intensely debated in Norway. An explanation of this, they suggest, is that the EBP question has had ‘low visibility’ in social work (p. 272), and that a health perspective has been most predominant. This development is linked to the inclusion by the Knowledge Centre for Health Services, an agency under the Norwegian Directorate of Health, of social work into its field of interest. Later, the Campbell centre’s activities were integrated into the Cochrane network with the argument that ‘many of the social policy questions were actually social-medicine questions’ (p. 271).

Method

The study was performed as a scoping literature review (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). This means that the review was carried out to survey and account for what has been reported in scientific journals, professional journals, theses, debate articles and reports on EBP in social work in Sweden. This approach was chosen to avoid limiting the review to identifying, and emphasizing the quality of, the included studies (as is usually the case with systematic literature reviews). Relevant databases were identified and search terms, as well as search strategies, were developed, with the help of a librarian. In the table below the different search terms used in search strategies are illustrated.

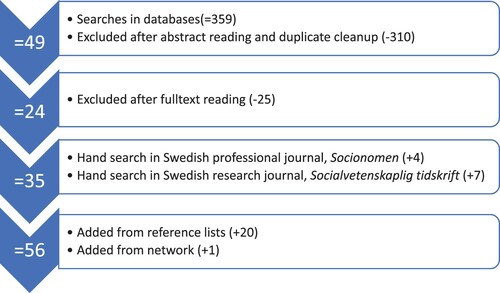

Two meta-search engines focusing on scholarly literature were used: Social Science Premium Collection and Soc Index. The search terms used were ‘evidence based social work’ and ‘Sweden’. All kinds of publication types were included, and the search was done ‘in all text’. The date range of the search was from first year published to November 2020. A hand-search was also done for two journals, the research supplement to the professional journal Socionomen, and Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, in which peer-reviewed articles on social work written in Swedish are published. The inclusion criteria were that texts must concern social work and discuss, criticize and debate EBP as a phenomenon and the development of EBP in Swedish social work. Studies whose primary aim was to develop evidence about social work methods or that lacked reflection on EBP as such were excluded. Furthermore, the articles had to be written in English or Swedish. When relevant articles were found, their reference lists were also scrutinized to find articles that were not found through the other methods.

The database search process is illustrated in and the results of final selection of the articles are marked with an asterisk in the reference list. The initial search yielded 359 texts (articles, conference papers and monographs) and of these, In Social Science Premium Collection 239 texts were found and in Soc Index 120 texts. After applying inclusion criteria, 24 texts were left. A hand search was conducted for the two mentioned journals yielding four articles in Socionomen and one via the original search, giving five in total, and seven in Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift. Reference lists and network were then consulted for additional references, adding a further 21 papers. The result comprises 56 peer-reviewed texts which was published between 1998 and 2020. After reading through the texts we chose to structure the presentation around six headings: Evidence-based practice in Swedish social work – which presents the historical development of EBP in social work in Sweden; Organizing evidence-based practice and providing organizational support for it – which presents how support for EBP is structured; Contents of guidelines and decision-making support systems for evidence-based practice – which presents how guidelines and decision-making support have been presented and criticized; Social workers’ use and interest in evidence-based practice – which presents the attitudes toward and knowledge about EBP among social workers; Managers, directors and evidence-based practice – which presents the attitudes and knowledge of managers; and finally Social work organization and evidence-based practice – which presents the most recent developments regarding evidence-based practice in Sweden. The article ends with a discussion of the results.

Results

Evidence-based practice in Swedish social work

The concept of EBP was introduced in Sweden at the end of the 1990s (Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2006a). However, already in 1992, the Center for Evaluation of Methods in Social Work (Centrum för utvärdering av metoder i socialt arbete, CUS) had been established because of a perceived need at the time to produce and systematize scientifically based evaluations of treatments and other interventions within social services. CUS was active between 1992 and 2003 (Tengvald, Citation2019). One of CUS’s assignments was to produce research reviews within the area of social work. In a sense, CUS was thus a response to existing expectations about controlling the costs and results of social work. In 2004 CUS was replaced by ‘The Institute for development of methods in social work’ (Institutet för utveckling av metoder i socialt arbete, IMS) (Tengvald, Citation2019), which up to 2009 had essentially the same assignment as CUS. CUS was also responsible for supporting or conducting its own studies and evaluations of social measures and structured programmes, for supporting the development of systematic tools for evaluation, and for disseminating information to practitioners and decision makers. During the 1990s and 2000s a discursive battle between representatives of universities and research institutions, on the one hand, and representatives of the public authorities CUS and IMS on the other, raged within research publications and in debate articles (see e.g. Svanevie, Citation2011). This controversy had epistemological, methodological, theoretical and ethical implications, and bore many similarities to the international research debate on EBP in social work. The questions addressed by the controversy included the difficulty of developing and standardizing methods for the field of social work (Månsson, Citation2003) and the problems with basing directives for interventions and methods on the results of randomized, controlled trials (Hydén, Citation2008).

In the argumentation that took place during this period, one can see two opposing viewpoints among the institutions and agents that were the driving and influential forces regarding what directions should be taken. Attempting to generalize, one might say that the discussion about how to understand and implement the EBP project in the Swedish context has leaned toward one of two opposing, though not necessarily completely incommensurable, models, namely a Guideline Model and a Critical Appraisal Model. The former is based on a top-down strategy, by which professionals are supplied with a knowledge base or simply with guidelines that have been developed for social work by researchers and other experts. The other model requires professionals themselves to work systematically and methodically with an evaluative approach to develop knowledge about their practice. This model bears more similarity to a bottom-up strategy and in Sweden it has received much less attention and had less impact (see e.g. Oscarsson, Citation2011). According to Bergmark and Lundström, the EBP movement in Sweden can be seen as having been unreflectively imported by representatives of Swedish bureaucracy (Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2006a, p. 109).

Soydan (Citation2010) talk about a lack of success of EBP in social work in Sweden explained by a failure of cooperation between policy, researchers and practitioners. Other researchers, for example Oscarsson (Citation2011), link the development of the EBP movement to sociocultural and socio-political changes that have taken place in Swedish society. According to Oscarsson, there is a trend towards medicalization and individualization of social problems. This trend coincides with the interest in the NPM (New Public Management) model and the privatization of welfare. These changes in the view of social problems and their possible solutions have created a new agenda for the provision of social services, in harmony with the striving for EBP in social work. This trend towards medicalization is a constant topic of debate as are the opposition to the top-down implementation of EBP (Johansson, Citation2019). In a recent article, for example, Jacobsson and Meeuwisse (Citation2020) argue that EBP in social work is dominated by a medical epistemological perspective, which has led to social work being standardized, while aspects that are not possible to measure, such as preventive social work, run the risk of being thinned out.

Past years, articles in where EBP are discussed as being strengthened and in need of reflection, practice-based knowledge or praxis-based knowledge can be seen, perhaps as an answer to above mentioned critic (Nilsen et al., Citation2012; Petersén & Olsson, Citation2015; Ryding & Wernersson, Citation2019).

Organizing evidence-based practice and providing organizational support for it

In comparison with the health field, the funding for R&D of social work conducted, for example, within the social services is very meagre, and overall, very little R&D is conducted within social work practices. The ties between universities and the R&D units that exist on a local level have also been relatively weak, with a few exceptions that were manifested in a temporary initiative called ‘The Social Services University’ (Socialtjänstuniversitetet), which was a government assignment titled ‘National Support for the Development of Knowledge within Social Services’ (Nationellt stöd för kunskapsutveckling inom socialtjänsten). Perhaps as a consequence of the weak connections between local R&D units and research at universities, the research that has been conducted within many of these units has been criticized for being of inferior scientific quality (Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2006b; Socialstyrelsen, Citation2002, p. 166). In a review of all R&D units in Sweden, for instance, Bergmark et al. (Citation2015) note that only six of the 28 units have formalized collaborations with universities, and that only those units that have been connected to a university for a long period of time publish their work as scientific articles or the like (for some exceptions, see Alexandersson et al., Citation2009; Citation2014).

Given the limited resources, both knowledge-related and financial, at the municipal level (where the majority of social work takes place) and the role that the state and state agencies and authorities have taken on and been given, it is not surprising that the EBP movement in social work in Sweden has had a top-down strategy. The main instigators have been the NBHW and the Unit for the Development of Knowledge (Enheten för kunskapsutveckling, EFK) with its predecessors CUS and IMS, as well as, to some extent, the universities (cf. Lundström & Shanks, Citation2013).

The mentioned dearth of resources allocated to the municipalities can also be detected in the agreement on the establishment of a support structure first signed in 2010 between the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Socialdepartementet) and Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (Sveriges kommuner och regioner – SKR) (Denvall & Johansson, Citation2012). This came about because the municipal social services were considered weak in the areas of ‘knowledge creation’ and ‘knowledge management’ (Socialstyrelsen & SKR, Citation2011). In the 2015 contract between the Swedish state and SKR, it is stipulated that the support structure at a municipal level should, among other things, be ‘a dialogue partner vis-à-vis the national level in questions concerning the development and management of knowledge’, ‘a developmental support system for the implementation of new knowledge, for instance, national guidelines and methods’, and ‘a contributor to creating the conditions for EBP throughout the social services and in related healthcare’ (Socialdepartementet & SKR, Citation2015). In practical terms, this means that the support structure, which still is in place, is designed to disseminate such knowledge as has been determined to be evidence-based on a general level by central authorities, such as the NBHW and transfer it from the central authorities down and outwards. It also means that the funds should be used to contribute to the development of EBP within the municipal social services. The latter would be done by giving support to the municipal- or regional-level R&D units. However, as it turns out, the agreement does not concretely allocate any funds for developing evidence-based methods. Instead it offers finances for the transmission of knowledge or directives, for instance from NBHW, which are disseminated at conferences, courses, and support for organizational development, with regional leaders of development and R&D units as intermediaries. Moreover, the research community has no prominent position in this structure, its role being limited to a consultative one, which has been criticized by the research community (Denvall & Johansson, Citation2012; Jacobsson & Meeuwisse, Citation2020). Researchers have also long pointed out the urgent need for a municipal organization that supports EBP, for instance, with individuals specifically assigned to work with and be responsible for questions of evidence on a local level (Bergmark et al., Citation2011; Ponnert & Svensson, Citation2011). Björk (Citation2016a) maintains that if Critical Appraisal is to be practised, at least one social worker or manager per unit should have the task of critically examining research related to client problems. That would be particularly relevant in cases where EBP guidelines have not yet been, or cannot be developed, which covers the vast majority of social work areas.

Content of guidelines and decision-making support systems for evidence-based practice

The most important actors developing guidelines and decision-making support system have been the aforementioned units CUS and IMS, as well as their successor, the Unit for the Development of Knowledge, all units within NBHW (cf. Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2011; Sundell et al., Citation2010). The academic community have so far not contributed greatly to developing guidelines, even though generally speaking the knowledge produced at universities is of course used as a foundation for such work. Swedish academic social work researchers have instead most often adopted a critically scrutinizing role regarding the content of the guidelines that have been developed within, for instance, the NBHW (see e.g. Engström, Citation2005; Gerdner, Citation2009; Mäkelä, Citation2004 on the use of the Addiction Severity Index, ASI, within social services).

The research community has also criticized the top-down strategy for the implementation of EBP that has been adopted within the NBHW. An example of such criticism was made against the programme for national implementation of guidelines for treating substance abusers and addicts (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2007), which is part of the programme ‘Knowledge for Practice’ (Kunskap till praktik).Footnote1 Researchers claim, for instance, that EBP has been presented in the guidelines in a vague and confusing way, and that it produces a false sense of confidence among social workers (Bergmark, Citation2007; Karlsson & Bergmark, Citation2012). Other expressed critic are that the NBHW is unclear about which of the two somewhat contradictory models for EBP (the top-down/Guideline Model or the bottom-up/Critical Appraisal Model) it advocates (Karlsson & Bergmark, Citation2012), and also that there is a lack of evidence to serve as a foundation for the guidelines (Bergmark et al., Citation2012; Karlsson et al., Citation2017; Sundell & Åhsberg, Citation2018).

At the same time, there is no clear-cut boundary between the stances held by academic researchers and authorities (see Hesse & Thylstrup, Citation2012). The reason for this is that the advocates of a top-down model for the implementation of EBP are represented in both camps, and university researchers quite often work for both universities and public authorities, or in other government or government-related contexts simultaneously.

Social workers’ use of and interest in evidence-based practice

Research on social workers’ knowledge about, interest in, and use of evidence illustrates a progression. In an article from the late 1990s, Bergmark and Lundström maintain that there is genuine uncertainty about whether the interventions that social workers claim they implement in their EBP comply with the requirement of a clear and consistent method (Bergmark & Lundström, Citation1998). In two subsequent articles, results are presented showing that Swedish social workers lack the competence to use international databases and to critically examine and synthesize research results (Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2000, Citation2008).

Further, Bergmark and Lundström (Citation2002) examine social workers’ attitudes toward and use of different sources of knowledge, as well as how they interpret the concept of EBP and make use of research. They note that even though many social workers have an academic degree and various types of supplementary training, they have little interest in assimilating research results into their daily work. As few as one out of four social workers working with individuals and families are active consumers of research relevant to their work. Two years later Bergmark and Lundström (Citation2007) finds that even though social workers’ attitudes toward evidence have become more positive, they do not follow the research well enough to be able to practise EBP in accordance with the recommendations of such authors as Sackett et al. (Citation2000) and Oscarsson (Citation2009) (see also, Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2011; Kaunitz & Strandberg, Citation2009; Ponnert & Svensson, Citation2011). In opposition to these results, however, Heiwe et al. (Citation2013) report that 53 per cent of medical social workers read research literature between two and five times a month.

Gustle et al. (Citation2007) report, somewhat surprisingly, that social workers’ attitudes toward evidence-based research seem to be of minor importance when referring clients to Multisystemic Therapy (MST). More explanatory was the social workers’ sympathy with the treatment ideology.

Even though social workers overall seem to be becoming more open and knowledgeable about EBP, the support for practising it according to a guideline model is weak, due to the scarcity of guidelines in social work (see Bergmark & Lundström, Citation2000; Citation2008; Bergmark et al., Citation2011; Lundström & Shanks, Citation2013). In those cases where guidelines do exist, the upside is that they can be helpful in arguing for resources, however the downside is that they seem to distance social workers from their clients (Avby et al., Citation2014; Hjärpe, Citation2020). Moreover, medical social workers face the dilemma of being dominated by a positivistic knowledge culture, because they work closely with medical professionals (Udo et al., Citation2019). This aspect of clashing knowledge interests is also discussed by Bergmark and Lundström (Citation2011) though from the perspective of EBP itself emanating from a positivistic knowledge culture.

Managers, directors, and the evidence-based practice

Managers within social work have also been highlighted in discussions about EBP. In a study from 2011, the authors compare the results regarding municipal social services managers’ attitudes towards and knowledge about EBP with the results of a previous study (Socialstyrelsen, Citation2011; Sundell et al., Citation2008). The findings show that managers had a greater interest in EBP and perceived that their employees used evidence-based treatment methods more often in 2010 than in 2007. Other research shows that managers in both social services and elderly care perceive themselves as important for the implementation of EBP. Having said that, when looking at what the managers actually did, their contributions were assessed as ad hoc and more focused on the installation phase of informing staff about EBP and creating engagement and motivation, and less on the full implementation phase. Moreover, managers from the social services were described as more knowledgeable and positive towards EBP than managers within elder care (Mosson et al., Citation2017). These results were somewhat confirmed by Rojas and Stenström (Citation2020) who reported that EBP was used to a lesser extent in both elder care and disability care services than in family care services.

Lundström and Shanks (Citation2013) researched middle-level managers within social services, their view on EBP, and how they transform EBP into a social practice. Some of the managers express scepticism about what they experience as excessive rigidity in the implementation of evidence-based programmes. Consequently, the managers revise the original concept of EBP, turning it into evidence-informed social work, which turns out to be less restrictive when it comes to how robust the implemented methods must be and to implementing scientifically corroborated knowledge and methods. These results might be explained as a necessary concession made by the managers to adapt EBP to social workers who are generally less positive (Gustle et al., Citation2008).

The organization of social work and evidence-based practice

In recent articles, greater emphasis is placed on aspects that can be attributed to organizational factors. Several researchers have highlighted the importance of organizational support as an explicit facilitator for an intervention’s implementation (Mosson et al., Citation2017; Rojas & Stenström, Citation2020). Other factors facilitating an intervention’s success in an organization would be how well it fits with the routines and practices of the organization (Björk, Citation2016b) and staff possessing sufficient knowledge to search for evidence or to systematically follow up interventions (Rojas & Stenström, Citation2020).

A barrier to implementation is the existence of different understandings of the concept among middle and top managers (Bäck et al., Citation2020). Top managers are described as regarding EBP as a responsibility of the organization that must be implemented in response to social pressure, because of the competitive advantages it affords, and to serve as quality assurance. On the other hand, middle managers understood EBP on a more operational level and differed amongst themselves in how they perceived it.

Another barrier hindering EBP implementation, brought up by Ryding and Wernersson (Citation2019), consists of the recurrent re-organizations of social services, which might entice practitioners to return to business as usual.

Discussion

The review of how the EBP has been received, interpreted and practiced in Swedish social work shows that two research units (CUS and IMS) under the public authority National Board of Health and welfare have had significant influence on the travel of EBP to Sweden. The results also show that a guideline-model version of EBP has been given priority in the diffusion process. The results also show that the interest in EBP among managers has increased over the past few years, and that their attitude toward the concept is generally positive. The results further show that Swedish social workers rarely make use of the results of research in their work, seldom use evidence-based methods and that there seems to be a certain degree of confusion of the meaning of the concept in relation to social work practice.

When trying to understand the development of EBP in social work in Sweden the conditions for the travelling of concepts like EBP (i.e. transformation, boundaries, institutional context, routs and producer and carriers or providers) introduced in the introduction are useful. It is also interesting to compare the development in Sweden with what is known from other Nordic countries.

I such a comparison some circumstances appear particularly interesting when understanding why EBP as a narrative could gain a foothold. It seems, for instance, evident that the institutional conditions in Sweden, unlike those in Finland, rather than preventing instead facilitated that the EBP concept could gain a foothold. Such facilitated conditions apply in particular to the difference in trust that authorities in the two countries had in the ability of social workers to carry out professional work (see Hübner, Citation2016). In Sweden, opinions were expressed by representatives of the NBHW and IMS that social work in Sweden was performing some sort of ‘guessing game’ and was ‘opinion-based’ rather than evidence-based (see e.g. Sundell et al., Citation2010; Wigzell & Pettersson, Citation1999). The referred actors therefore suggested that EBP could be a tool to be useful to deal with the lack of professionalism that the descriptions they identified.

Another condition that seems to have been the case in Sweden, unlike Finland, is that government representatives and researchers at CUS and IMS established contacts with colleagues that could be regarded as important carriers and providers of the EBP concept. This was for instance manifested by the arrangement of a national conference on evaluation of social work, with a large number of invited researchers in field from USA and the UK which took place in 2007 (see e.g. Soydan, Citation1998).

There are also some parallels between the developments in Sweden and Denmark on the issue of the importance of key actors. In comparison to Denmark, for example, a similar development has taken place regarding key people leaving the important units (IMS) and the transfers of the EBP-question to other institutions.

The research institute that was the driving force behind EBP, namely IMS, was, as already mentioned, later replaced by the Unit for the Development of Knowledge, within NBHW. Later the Swedish Agency for Health Technology assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU), an authority with the task of making independent evaluations of methods and initiatives in health care, dentistry, also was given an increased responsibility to include evaluations of methods within the social services and the area of functional disability. With these changes, the key actors who were the initiators and the driving forces within CUS and IMS have also been replaced. The more ‘hard-boiled’ version of EBP that originally launched had, with this, thus also disintegrated into a less homogeny version of what EBP stands for (see e.g. Karlsson & Bergmark, Citation2012). Perhaps it is also this gradual heterogenization that has contributed to professionals in the social services now to a greater extent being able to claim that they meet the requirements set. Similar to the development in Norway, it is probably true to say that the EBP concept did not become a reason for any more extensive discussions in social practices in Sweden either, instead it was in the academic world that the differences of opinion were aired. As (Leicht et al., Citation2009, p. 583) suggest this might be attributed to that the social work profession since the 1990s when the first waves of neo-liberal organizational changes started, has been subjected to so many organizational changes that they are used to deal with the inherent tension between ‘the institutional logic of professional practice centred on professional–client relationships, autonomy, collegiality and professional ethics on the one hand, versus a technical environment stressing market efficiency, technological change and organizational innovation on the other’ and therefore are, so to say, too exhausted to engage in all changes that bears similarities to the NPM rationale.

Finally, we suggest that one institutional condition is particularly important for understanding how the EBP-concept was received I Sweden, and that is the uneven balance that exists between the state and the municipalities, with the state as the legislator and the municipalities as the providers of welfare services. We suggest that because of Sweden’s history of a strong central state, initiatives and directives from the state authorities have remained relatively uncontested, despite the fact, as has been shown in the review, that their content has been vague. At the same time, however, the long-term scarcity of resources on municipal level, and the division between the state setting the terms and the municipalities having the role as ‘implementers’ has led to a situation where EBP has been cherished in theory, but very limited resources have actually been allocated for its implementation in practice (see e.g. Socialstyrelsen & SKR, Citation2011). Social workers and their superiors have therefore received relatively weak support from their municipal employers to implement EBP, even though the concept of EBP, as shown in the review, has been accepted by frontline workers and their superiors. Similar problems with organizational and financial conditions have also been reported from other countries, showing that applying research to practice never has been an economically prioritized area (see, e.g. Gray et al., Citation2009).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pernilla Liedgren

Pernilla Liedgren is Associate Professor at the Department of Social Work, Mälardalen University, Sweden. Her research interest relates to poverty and over-indebtedness, professional issues of social workers as well as inter-relational and evidence-based social work.

Christian Kullberg

Christian Kullberg is professor in social work at the Department of Social Work, Mälardalen University, Sweden. One of his research interests is gender in social work, which includes studies on the Swedish income support, victim support work with young adults and budget and debt counselling.

Notes

1 Kunskap till praktik was started by SKR in 2008 following an agreement between it and the government about overall focus and financing.

References

- Alexandersson, K., Beijer, E., Bengtsson, S., Hyvönen, U., Karlsson, P-Å, & Nyman, M. (2009). Producing and consuming knowledge in social work practice: Research and development activities in a Swedish context. The Evidence and Policy, 5(2), 127–139. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/174426409X437883

- Alexandersson, K., Hyvönen, U., Karlsson, P-Å, & Larsson, A.-M. (2014). Supporting user involvement in child welfare work: A way of implementing evidence-based practice. Evidence and Policy, 10(4), 541–554. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/174426414X14144219467266

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Toward a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Avby, F., Nilsen, P., & Abrandt Dahlgren, M. (2014). Ways of understanding evidence based practice in social work: A Qualitative study. British Journal of Social Work, 44(6), 1366–1383. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs198

- Bäck, A., von Thiele, S., Hasson, H., & Richter, A. (2020). Aligning perspectives? – comparison of Top and middle managers’ view on How organization influences Implementation of Evidence-Based practice. The British Journal of Social Work, 50(4), 1126–1145. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcz085

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality a treatise in the sociology of knowledge. Penguin.

- Bergmark, A. (2007). Guidelines and evidence-based practice – a critical appraisal of the Swedish national guidelines for addiction treatment. Nordisk Alkohol & Narkotikatidskrift, 24(6), 589–599. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250702400602

- Bergmark, A., Bergmark, Å., & Lundström, T. (2011). Evidensbaserat socialt arbete - teori, kritik, praktik. Natur & Kultur.

- Bergmark, A., Bergmark, Å, & Lundström, T. (2012). The mismatch between the map and the terrain – evidence-based social work in Sweden. European Journal of Social Work, 15(4), 598–609. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2012.706215

- Bergmark, A., & Lundström, T. (2006a). Mot en evidensbaserad praktik? Om Färdriktningen i Socialt Arbete. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 13, 99–113. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.2006.13.2.2605

- Bergmark, A., & Lundström, T. (2006b). Utvärderingar inom socialtjänsten – FOU-enheternas bidrag. Socionomen, 4, 28–30. 41. *.

- Bergmark, A., & Lundström, T. (2008). Evidensfrågan och socialtjänsten – om socialarbetares inställning till en vetenskapligt grundad praktik. Socionomens Forskningssupplement, 3, 5–14. *.

- Bergmark, A., & Lundström, T. (2011). Guided or independent? Social workers, central bureaucracy and evidence-based practice. European Journal of Social Work, 14(3), 323–337. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691451003744325

- Bergmark, Å, & Lundström, T. (1998). Metoder i socialt arbete. Om Insatser och Arbetssätt i Socialtjänstens Individ- och Familjeomsorg. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 4, 291–314. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.1998.5.4.2918

- Bergmark, Å, & Lundström, T. (2000). Kunskaper och kunskapssyn. Socionomens Forskningssupplement, 12, 1–16. *.

- Bergmark, Å, & Lundström, T. (2002). Education, practice and research. Knowledge and Attitudes to Knowledge of Swedish Social Workers. Social Work Education, 21(3), 359–373. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470220136920

- Bergmark, Å, & Lundström, T. (2007). Att studera rörliga mål – om villkoren för evidens och kunskapsproduktion i socialt arbete. Socionomens Forskningssupplement, 21(3), 4–16. *.

- Bergmark, Å, & Lundström, T. (2011b). Evidensbaserat socialt arbete. Teori, kritik, praktik. Natur och Kultur. *.

- Bergmark, Å, Lundström, T., & Stranz, H. (2015). Från lokal förankring till regional samverkan? FoU-miljöer i socialtjänstens individ- och familjeomsorg. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 2, 133–151. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.2015.22.2.2348

- Björk, A. (2016a). Evidence-based practice behind the scenes. How evidence in social work is used and produced. Dissertation in social work. Stockholm University. * http://su.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A900625&dswid=-2831

- Björk, A. (2016b). Evidence, fidelity, and organizational rationales: Multiple uses of motivational interviewing in a social services agency. Evidence and Policy, 12(1), 43–71. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/174426415X14358305421172

- Czarniawska, B., & Joerges, G. (1996). Travels of ideas. In B. Czarniawska & G. Sevón (Eds.), Translating organizational change (pp. 13–48). DeGruyter.

- Denvall, V., & Johansson, K. (2012). Kejsarens nya kläder – implementering av evidensbaserad praktik i socialt arbete. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 1, 26–45. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.2012.19.1.2453

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2095101

- Elvbakken, K. T., & Hansen, H. F. (2019). Evidence producing organizations: Organizational translation of travelling evaluation ideas. Evaluation, 25(3), 261–276. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389018803965

- Engström, C. (2005). Implementering och utvärdering av Addiction Severity Index (ASI) i socialtjänsten. Akademisk avhandling. Institutionen för psykologi. Umeå universitet. *.

- Gerdner, A. (2009). Diagnosinstrument för beroende och missbruk – granskning av ADDIS validitet och interna konsistens gällande alkoholproblem. Nordisk Alkohol- og Narkotikatidsskrift, (NAT), 26(3), 265–276. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250902600303

- Gray, M., Plath, D., & Webb, S. (2009). Evidence-based social work: A critical stance. Routledge.

- Gustle, L.-H., Hansson, K., Sundell, K., & Andrée-Löfholm, C. (2007). Multisystemic therapy project in Sweden: What factors affect the tendency of social workers to refer subjects to the research project? International Journal of Social Welfare, 16(4), 358–366. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.2007.00491.x

- Gustle, L.-H., Hansson, K., Sundell, K., & Andrée-Löfholm, C. (2008). Implementation of evidence-based models in social work practice: Practitioners’ perspectives on an MST Trial in Sweden. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse, 17(3), 111–125. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15470650802071713

- Hansen, H. F., & Rieper, O. (2010). The politics of evidence-based policy-making: The case of Denmark. German Policy Studies, 6(2), 87–112.

- Harris, J., Borodkina, O., Brodtkorb, E., Evans, T., Kessl, F., Schnurr, S., & Slettebø, T. (2015). International travelling knowledge in social work: An analytical framework. European Journal of Social Work, 18(4), 481–494. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2014.949633

- Heiwe, S., Nilsson-Kajermo, K., Olsson, M., Gåfvels, C., Larsson, K., & Wengström, Y. (2013). Evidence-based practice among Swedish Medical social workers. Social Work in Health Care, 52(10), 947–958. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2013.834029

- Hesse, M., & Thylstrup, B. (2012). Practice between scylla and charybdis. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 29(3), 273–275. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2478/v10199-012-0020-0

- Hjärpe, T. (2020). Mätning och motstånd. Sifferstyrning i socialtjänstens vardag. Akademisk avhandling. Socialhögskolan, Lunds universitet. *

- Hübner, L. (2016). Reflections on knowledge management and evidence based practice in the personal social services of Finland and Sweden. Nordic Social Work Research, 6(2), 114–125. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2015.1117985

- Hydén, M. (2008). Evidence-based social work på svenska – att sammanställa systematiska kunskapsöversikter. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 15(1), 3–19. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.2008.15.1.2580

- Jacobsson, K., & Meeuwisse, A. (2020). ‘State governing of knowledge’–constraining social work research and practice. European Journal of Social Work, 23(2), 277–289. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1530642

- Johansson, K. (2019). Evidence-based social service in Sweden: A long and winding road from policy to local practice. Evidence & Policy, 15(1), 85–102. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/174426417X15123846324591

- Karlsson, P., & Bergmark, A. (2012). Implementing guidelines for substance abuse treatment: A critical discussion of “knowledge to practice”. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 29(3), 253–265. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2478/v10199-012-0017-8

- Karlsson, P., Bergmark, T., & Lundström, A. (2017). Effects of psychosocial interventions on behavioral problems in youth: A close look at Cochrane and Campbell review. International Journal of Social Welfare, 26(2), 177–187. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12240

- Kaunitz, C., & Strandberg, A. (2009). Aggression replacement training (ART) i sverige- evidensbaserad socialtjänst i praktiken. Socionomens Forskningssupplement, 26, 36–52. *.

- Kessl, F., & Evans, T. (2015). Special issue: Travelling knowledge in social work. European Journal of Social Work, 18(4), 477–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2015.1067381

- Leicht, K., Walter, T., Sainsaulieu, I., & Davies, S. (2009). New public management and new professionalism across nations and contexts. Current Sociology, 57(4), 581–605. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392109104355

- Lundström, T., & Shanks, E. (2013). Hård yta men mjukt innanmäte. Om hur chefer inom den sociala barnavården översätter evidensbaserat socialt arbete till lokal praktik. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 20(2), 108–126. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.2013.20.2.2436

- Mäkelä, K. (2004). Studies of the reliability and validity of the Addiction Severity index. Addiction, 99(4), 398–410. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00665.x

- Månsson, S.-A. (2003). Att förstå sociala insatsers värde. Nordiskt Socialt Arbeid, 23(2), 73–80. *.

- Mosson, R., Hasson, H., Wallin, L., & von Thiele Schwarz, U. (2017). Exploring the role of line managers in implementing evidence-based practice in social services and older people care. British Journal of Social Work, 47, 542–560. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw004

- Mullen, E., & Streiner, D. (2004). The evidence for and against evidence-based practice. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 4(2), 111–121. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhh009

- Nevo, I., & Slonim-Nevo, V. (2011). The myth of evidence-based practice: Towards evidence-informed practice. British Journal of Social Work, 41(6), 1176–1197. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq149

- Nilsen, P., Nordström, G., & Ellström, P.-E. (2012). Integrating research-based and practice based knowledge through workplace reflection. Journal of Workplace Learning, 23(6), 4403–4415. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/13665621211250306

- Oscarsson, L. (2009). Evidensbaserad praktik inom socialtjänsten – En introduktion för praktiker, chefer, politiker och studenter. SKR Kommentus. *.

- Oscarsson, L. (2011). Utvärdering och evidensbasering. In B. Blom, L. Nygren, & S. Morén (Eds.), Utvärdering i socialt arbete: Utgångspunkter, modeller och användning (pp. 183–198). (1st ed.). Natur & Kultur.

- Petersén, A., & Olsson, J. (2015). Calling evidence-based practice into question: Acknowledging phronetic knowledge in social work. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1581–1597. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu020

- Ponnert, L., & Svensson, K. (2011). När förpackade idéer möter organisatoriska villkor. Socialvetenskaplig Tidskrift, 3, 168–185. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3384/SVT.2011.18.3.2510

- Rojas, Y., & Stenström, N. (2020). The Effect of organizational factors on the Use of evidence-based practices among Middle Managers in Swedish social services. Human Service Organizations: Management, Leadership & Governance, 44(1), 32–46. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2019.1683667

- Ryding, J., & Wernersson, I. (2019). The role of reflection in family support social work and its possible promotion by a research-supported model. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 16(3), 322–345. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/26408066.2019.1606748

- Sackett, D., Strauss, S., Richardson, W., Rosenberg, W., & Haynes, R. (2000). Evidence-Based medicine: How to practice and teach EBM. Churchill and Livingstone.

- Sahlin-Andersson, K. (2001). National, International and transnational constructions of New Public Management. In New Public Management. In T. Christensen & P. Lægreid (Eds.), The transformation of ideas and practice (pp. 43–72). Ashgate.

- Socialdepartementet & SKR. (2015). Stöd till en evidensbaserad praktik för god kvalitet inom socialtjänsten. Agreement for year 2015 between the state and Sveriges Kommuner och Landsting. Appendix to protocol for the government session 2015-01-22 number II:2. *.

- Socialstyrelsen & SKR. (2011). På väg mot en evidensbaserad praktik inom socialtjänsten. Kartläggning, analys och förslag för att förbättra kunskapsstyrningen. Socialstyrelsen och SKR. *.

- Socialstyrelsen. (2002). Utvärdering av FoU – En studie av FoU-enheter inriktade på individ- och familjeomsorg. *.

- Socialstyrelsen. (2007). Nationella riktlinjer för missbruks- och beroendevård: Vägledning för socialtjänstens och hälso- och sjukvårdens verksamhet för personer med missbruks- och beroendeproblem. *.

- Socialstyrelsen. (2011). Evidensbaserad praktik i socialtjänsten 2007 och 2010. Kommunala enhetschefer om evidensbaserad praktik och användning av evidensbaserade metoder inom socialtjänstens verksamhetsområde. *.

- Soydan, H. (1998). Evaluation research and social work [Special issue]. Scandinavian Journal of Social Welfare, 7(2), 74–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2397.1998.tb00205.x

- Soydan, H. (2010). Evidence and policy: The case of social care services in Sweden. Policy Press, 6(2), 179–193. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/174426410X502301

- Soydan, H. (2014). Evidence-based practice in social work. Development of a new professional culture. Routledge. *.

- Sundell, K., & Åhsberg, E. (2018). Trends in methodological quality in controlled trials of psychological and social interventions. Research on Social Work Practice, 28(5), 568–576. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731516633297

- Sundell, K., Brännström, L., Larsson, U., & Marklund, K. (2008). På väg mot en evidensbaserad praktik. Rapport. IMS. *.

- Sundell, K., Soydan, H., Tengvald, K., & Anttila, S. (2010). From opinion-based to evidence-based social work: The Swedish case. Research on Social Work Practice, 20(6), 714–722. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731509347887

- Svanevie, K. (2011). Evidensbaserat socialt arbete: Från idé till praktik. [Doctoral dissertation, Umeå University]. Department of Social Work. *. http://umu.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A455430&dswid=9121

- Tengvald, K. (2019). För forskning om socialtjänstens funktionssätt och resultat ur ett klient- och brukarperspektiv – underlag till fortes program för tillämpad välfärdsforskning. Appendix 11. Forte. *.

- Udo, C., Forsman, H., Jensfelt, M., & Flink, M. (2019). Research Use and evidence-based Practice Among Swedish Medical Social Workers: A Qualitative study. Clinical Social Work Journal, 47(3), 258–265. *. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0653-x

- Vedung, E. (2010). Four waves of evaluation diffusion. Evaluation, 16(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1356389010372452

- Wigzell, K., & Pettersson, L. (1999, 6th of October). “Hjälp till svaga bara chansning”. Ny undersökning från Socialstyrelsen: Varannan socialchef vet inte om socialtjänsten gör någon nytta. Dagens Nyheter.