ABSTRACT

The social worker-client relationship is described as essential to social work but is a broad and multi-layered concept. Today, the relationship is strengthened and challenged by digitalisation. The aim of this configurative literature review is to understand how research on social work from 2015 to 2020 describes and analyses digitalisation’s significance for the social worker-client relationship. Three themes depict the benefits and disadvantages of digitalisation, how digitalisation generates new ethical questions and dilemmas, and the different theoretical perspectives used. Future research should go beyond the pros and cons of digitalisation and should use various theoretical approaches to challenge data, illuminate client perspectives, and pose additional questions.

SAMMANFATTNING

Relationen mellan socialarbetare och klienter beskrivs som central för socialt arbete men är ett brett och mångtydigt begrepp. Idag stärks och utmanas relationen genom digitalisering. Syftet med denna konfigurativa litteraturöversikt är att förstå hur forskning om socialt arbete mellan 2015 och 2020 beskriver och analyserar digitaliseringens betydelse för relationen mellan socialarbetare och klient. Tre teman visar digitaliseringens fördelar och nackdelar, hur digitaliseringen genererar nya etiska frågor och dilemman, och de olika teoretiska perspektiv som används. Framtida forskning bör gå längre än för- och nackdelar med digitalisering och bör använda teori för att utmana data, belysa klientperspektiv och ställa ytterligare frågor.

Introduction

There is a strong political narrative in the European Union to increase the digitalisation of welfare services (e.g. European Commission, Citation2020), not least during the COVID-19 pandemic. Digitalisation, in which domains of social life are restructured around, digital communication and media infrastructures (Brennen & Kreiss, Citation2016), is increasingly manifested in digital tools that support, govern, or replace social work practice within case management (e.g. automation), outcome measurement (e.g. standardised assessment), interventions (e.g. online counselling), and communication (e.g. video meetings) (cf. Mackrill & Ebsen, Citation2018).

In this literature review, we investigate the significance of digitalisation in social work practice for the social worker-client relationship. This relationship can be understood not only as an integral part of social workers’ professional identity and purpose (Rollins, Citation2020, p. 395) but also as the very core of an intervention or as a service in itself (Gray et al., Citation2012). It is often framed as something ‘good’, such as a principle manifested in informed consent, therapeutic alliances, and dialogical relations (Payne, Citation2014, p. 48), or as an ethical principle where social workers should work towards empathetic relationships (IASSW, Citation2018, p. 3). Related values such as transparency, mutual trust, respect, and an interest in the client can support the social worker-client relationship (Rollins, Citation2020). For example, relationship-based practice aims to use the relationship as a medium to design interventions that increase clients’ exposure to relationships that are secure and responsive (Howe, Citation1998, p. 52; cf. Ruch, Citation2005). It involves using empathic skills and self-knowledge on the part of the social worker (Trevithick, Citation2003).

Still, the relationship is not ‘neutral’ but can be infused with power depending on context and asymmetric positions (Duffy, Citation2017), leading to a sense of powerlessness, guilt and shame (Rollins, Citation2020). The relationship may be involuntary giving rise to important ethical boundaries. The social worker-client relationship has also been challenged by ‘lawyers, managers and proceduralists’, according to Howe (Citation1998, p. 48), giving preference for:

… responding to people’s external performance rather than understanding their internal psychology, measuring need and behaviour according to checklists rather than understanding motivation using personality theory, asking what people do rather than wonder why they do it, attending to the individual act rather than the individual actor.

In this literature review, we acknowledge the increased focus on digital tools in the social worker-client relationship and the subsequent research. However, such research relates to different understandings and conceptualisations of the relationship, thus making it a broad and multi-layered concept. We argue that through a configurative literature review we can approach the broad topic of the social worker-client relationship in order to illuminate important divides, common themes, and future research agendas. To our knowledge, there are no reviews on digitalisation’s implications for the social worker-client relationship.

The aim is to understand how research on social work from 2015 to 2020 describes and analyses digitalisation’s significance for the social worker-client relationship. We do this by investigating how research on social work depicts digitalisation’s significance for the relationship, its theoretical and conceptual approaches, and how it deals with issues of power and ethics inherent in the relationship. Next, we describe the research methods used and present our findings as three themes, closing with a discussion and conclusion.

Methods

Research design

The research design is a configurative literature review using thematic analysis. A configurative design aims to develop an understanding of how a certain substantive or theoretical research area is developing and how a certain phenomenon is conceptualised (cf. Gough et al., Citation2012). Also, the review is narrative in that it covers broader and less clearly defined topics and often develop theorised reflections on the work of others (Shaw & Holland, Citation2014). These points of departure are relevant because the concepts of digitalisation and relation are imprecise in the literature and because the study seeks to generate themes of how research on the social worker-client relationship has described and analysed these concepts. The downside of a narrative review, i.e. potentially being unsystematic and missing important studies (Shaw & Holland, Citation2014), is counteracted by employing steps of a systematic literature review for a transparent methodology: describing our research questions, systematic search process, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and our method of thematic analysis.

Search strategy

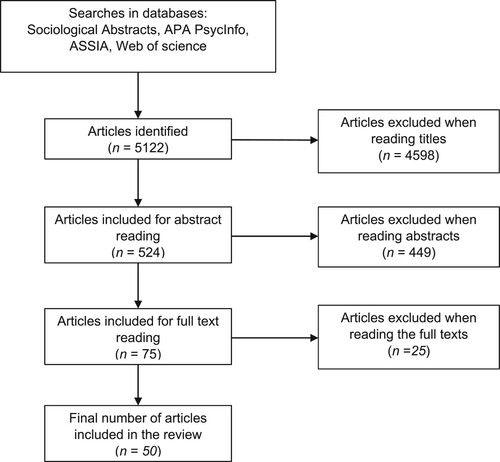

We targeted original peer-reviewed journal articles in English between 2015 and 2020 (see ). The databases went beyond social work journals to include other disciplines. The search consisted of the three key words, ‘digitalisation’, ‘social work’, and ‘relation’, and synonyms thereof.Footnote1

The search resulted in 5122 articles. The first author screened all titles and excluded duplicates and articles that were not related to digitalisation and social work, resulting in 524 articles. Their abstracts were read by two authors. A key criterion for inclusion was that the abstract must describe some sort of digital technology used by social workers in a social work practice with explicit implications, consequences, or significance for clients. Articles were excluded if digitalisation was itself the social problem (e.g. cyberbullying), if the technology was a policy and was not implemented in social work practice, or if they concerned target groups’ patterns of use, e.g. mobile phone usage. Also, digitalisation in areas such as psychiatry, health care, and probation were excluded to focus on social work. Moreover, articles were excluded if digitalisation did not concern the relationship between social workers and clients, e.g. support groups on Facebook. After reading the abstracts, 75 articles remained. After all authors read the full articles, additional articles were excluded according to the same criteria, leaving 50 articles. Among these, all but one study were conducted in the ‘global north’, mainly in Europe (26) and North America (16).

Method of analysis

We used Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2012) six-phase approach to thematic analysis in tandem with Nowell et al.’s (Citation2017) discussion of trustworthiness in thematic analysis to identify and organise patterns of meaning across the articles. First, all authors became familiarised (phase 1) with the data by reading the articles and documenting their thoughts. Tentative codes were generated (phase 2) by describing how relations were described and their role in relation to digitalisation (e.g. relations as communication, digitalisation as threat). Codes were discussed, reformulated, grouped, and regrouped in data tables resulting in the generation of descriptive themes (phase 3), e.g. how relations were described. After going back and forth between codes and descriptive themes, we got a sense of the tensions in the data that would become our interpretive themes. For example, one theme regards how half of the articles were empirical studies of digital tools in practice, while the other half relied on theoretical approaches to relations. During writing and new readings of the article, we reviewed and adjusted our themes (phase 4). The definitions and titles of the themes were continuously discussed and changed to reflect a theme’s unique content and not to overlap with other themes (phase 5). The analysis was an integrated part of the writing process and is described accordingly in this methods section (phase 6).

Limitations

We address two limitations. First, the timespan 2015–2020 is relatively brief. However, it was the most feasible design to provide interpretive themes of an elusive concept used within a broad research area of social work. Second, relevant research is always excluded. The key word relation may have excluded research that takes a more contextual and sociological turn on the relationship. Our results may also have excluded articles that dealt with digitalisation on an organisational level, as well as automated tools such as chat bots. We argue, however, that we obtained articles that dealt explicitly with relations, which was the primary criterion for inclusion.

Results

We describe our results in three themes: the benefits and disadvantages in using digital tools, ethical risks in the social worker-client relationship and three identified theoretical perspectives.

Benefits and disadvantages in using digital tools: general or context-specific results?

In this theme, we focus on 33 articles that highlight benefits and disadvantages in using digital tools in the social worker-client relationship. Most of the analysed articles focus on both (e.g. Breyette & Hill, Citation2015; Cwikel & Friedmann, Citation2020; Hobbis, Citation2018; Hodge et al., Citation2017; Lamberton et al., Citation2016; Lolich et al., Citation2019; Macdonald et al., Citation2017; Rönkkö, Citation2018 to mention a few). However, the included articles focus on both different digital tools and different practice settings and this can have implications for the interpretations of the results on a more general level. Below we present four possible ‘tensions’ between benefits and disadvantages for the relationship, which were visible in the literature.

First, there seems to be a tension between digital tools having either negative or positive effects on the social worker-client relationship. On the one hand, van de Luitgaarden and van der Tier’s (Citation2018) study shows that the process of establishing a working relationship in a chat application differs from offline settings. They stress that there are time constraints and that the engagement in the relationship is limited and is rather characterised by being standardised, straightforward, and brief. The interactions focus on a specific goal rather than focusing on building lasting working relationship between the social worker and the client (van de Luitgaarden & van der Tier, Citation2018; cf. Räsänen, Citation2015). Reamer (Citation2015, p. 130) who focus on clinical social work in a digital environment also writes that ‘ … the boundaries of the clinician-client relationship are now much less clear and much more fluid and ambiguous’. On the other hand, digital tools can have a positive effect on the therapeutic alliance or working alliance between the social worker and the client (Lopez, Citation2015; Mackrill & Ørnbøll, Citation2019). For example, by using an app system in three municipalities, social workers and clients (15–23 years old) could together explore specific goals and aspects of the client’s life. However, there are concerns about whether the social worker and client become too close and whether clients consider some of their goals and information to be too personal to share with their social worker (Mackrill & Ørnbøll, Citation2019). A study on school-based social work support shows how digital communication can also increase young people’s sense of being in control of the relationship because they can communicate more on their own terms (Bolin & Sorbring, Citation2017). Another study on the role of smartphones in foster care shows how they experience a greater sense of empowerment and individuality (Denby et al., Citation2016).

Second, there seems to be a tension between digital tools making services more accessible or less accessible for clients. On the one hand, scholars have described how the use of digital communication and social media increases young people’s perceptions of the social worker’s accessibility (Bolin & Sorbring, Citation2017; Chan & Ngai, Citation2019). There are no geographical/physical/time restrictions as in offline settings, which makes the services offered more accessible, especially for youth (Chan & Ngai, Citation2019). By using tablets, older clients also have much more interaction with their coaches (Brusoski & Rosen, Citation2015). Social media enables groups to be reached that are usually difficult to establish a relation with, such as ‘hidden youth’ who are socially withdrawn (Chan & Ngai, Citation2019; Leung et al., Citation2017). On social media, it is easier to discuss sensitive issues such as sex or suicide (Chan & Ngai, Citation2019), and it is easier to provide support that fits the client’s own needs (Lamberton et al., Citation2016). On the other hand, scholars have highlighted that the use of new digital tools has also created a ‘digital divide’, i.e. making the services that are offered less accessible for some target groups and individuals (Lee & Kim, Citation2019; cf. Mishna et al., Citation2020 for support for domestic violence victims during Covid-19). Digital interventions can sometimes require in-person assistance, and there are discussions on how to bridge the digital divide by, for example, offering different kinds of training in digital skills for clients (Lee & Kim, Citation2019; see also Breit et al., Citation2020) and for professionals (Lolich et al., Citation2019). So-called digital literacy is required from both the social workers and the clients (Recmanová & Vávrová, Citation2018).

Third, scholars have also highlighted a tension between digital surveillance as resistance and control. On the one hand, clients can record meetings with their social worker without their consent as a way to resist the power imbalance within the relationship. On the other hand, social workers sometimes consider it acceptable to use social media to gather information on their clients (cf. Byrne et al., Citation2019; La Rose, Citation2019; see also Breyette & Hill, Citation2015; Cooner et al., Citation2020 about the risk of monitoring clients’ online activities; older people Mortenson et al., Citation2015). Lim (Citation2017) who has conducted a study on youth workers’ use of Facebook discusses how social workers’ ‘surveillance’ of clients is not only used to ‘control’ the clients, but can also be used to get a more extensive picture of their clients’ lives, adjust their interventions, and intervene when their clients’ behaviour poses some kind of risk.

Fourth, there is a tension between being shaped by and shaping technology (e.g. De Witte et al., Citation2016; Gillingham, Citation2015). On the one hand, digital tools influence the content and form of several interventions (Jeyasingham, Citation2020; Recmanová & Vávrová, Citation2018; see also Turner, Citation2016 on social media). For instance, Electronic Information Systems sometimes tend to turn social work into a primarily technical practice (Devlieghere & Roose, Citation2018), and malfunctioning computer systems tend to disrupt the social worker-client relationship and can create distance between them (Räsänen, Citation2015). On the other hand, in order to avoid the technology setting the term for social work, scholars stress the importance of dialogue between developers of digital tools and social workers. Rather than being the passive recipients of new digital tools, social workers should take a more active role in participatory design processes. A study on older people in rural communities, also emphasises the importance of balancing the views of the clients in the design because stereotypic views on clients and their ability to use digital tools can make it difficult to reach certain target groups (Hodge et al., Citation2017). For example, Mackrill and Ebsen (Citation2018, p. 952) who have made a study on municipal youth protection work write: ‘External support and assessments of how to use, development, incorporate digital technology into practice need to be made available to municipalities, social workers and clients.

In sum, scholars have drawn different conclusions on how digitalisation affects the social worker-client relationships. It is unclear whether these different interpretations only reflect scholars’ focus on different types of digital tools, ‘talks’, or tasks, that can affect the relationship in different ways, or whether they simply draw different conclusions from the same type of observations. There is a need for more comparative studies to be able to extend the knowledge on general and context-specific benefits and disadvantages in using digital tools in the social worker-client relationship.

Ethical risks in the social worker-client relationship

The use of digital tools has created numerous ethical challenges regarding the social work concepts of ‘client informed consent; client privacy and confidentiality; boundaries and dual relationships; conflicts of interest; practitioner competence; records and documentation; and collegial relationships’ (Reamer, Citation2015, p. 120). In this theme, we focus on 16 articles that use the concept of ethics and describe how they label ethical risks from digitalisation in the social worker-client relationship. 11 articles focus on clinical social work with individuals and their families and one article on community work. Four articles belong in both categories.

First, articles differ in the use of the term ‘ethics’. For example, there is a preoccupation with professional codes in many articles (e.g. Groshong & Phillips, Citation2015; Mattison, Citation2018; Sinha et al., Citation2019). Mattison (Citation2018) argues that e-practices consist of threats against privacy and confidentiality and must be regulated by best practice of informed consent according to legal and moral non-prescriptive professional codes. The idea is that codes can protect clients from misuse of power in the relationship. Few articles concern inequality and the significance of clients’ gender, ethnicity, class, or sexuality for ethics in the social worker-client relation. For example, Byrne et al. (Citation2019) have a similar research interest as Mattison (Citation2018), but they also investigate power asymmetries in the social worker-client relationship by conceptualising clients’ surveillance of social workers as a form of resistance. These articles thus differ from those concerned with the professional codes, which are typically written in a clinical setting. The difference in use of the term ‘ethics’ is thus related to the setting in which the tools were studied.

Second, the ethical boundaries protecting both the clients and the social workers are also described differently in the articles on ethics. Overall, boundaries between the social workers and clients are described as crucial (e.g. Kellen et al., Citation2015; Mishna et al., Citation2020; Reamer, Citation2015), and articles describe how failing to maintain professional boundaries in the use of digital tools has ethical risks. For example, social workers being friendly and inviting clients into their private social media (or not being aware that it is visible for all) violates professional codes and risks self-disclosure towards clients with problems maintaining boundaries themselves. Also, failing to keep a distance risks poor judgment from the social worker that may harm the client by trespassing on their private sphere by using the clients’ private social media for gathering information (e.g. Breyette & Hill, Citation2015; Byrne & Kirwan, Citation2019). Some of these articles show an awareness of clients’ weak position in the relationship (e.g. Boddy & Dominelli, Citation2017; Cooner et al., Citation2020), and Cooner et al. (Citation2020) argue that social workers must consider clients’ power and lack of resources when using digital tools. However, most articles on clinical social work with individuals and their families are primarily concerned with the risks of digitalisation for social workers and less so the risks for clients. The very essence in other articles on ethics is how to overcome professional distance with digitalisation offering less focus on the individual and its deficits, and they focus more on developing relations through social justice. For example, the possibility for instant contact and for using technology to enhance relations that for some reason are difficult to carry out face-to-face becomes a possibility for creating a sense of community (e.g. Shevellar, Citation2017). Shevellar (Citation2017) concludes that participation in society for the poorest and most oppressed is becoming more dependent on e-technology, and getting in contact with authorities or applying for support becomes an ethical issue about living a good life. Common for all articles on digitalisation’s significance for ethical boundaries, regardless of context, is that no clients are asked about boundaries and thus given a voice.

Third, the articles on ethics do not only miss the client’s perspectives but also fails to acknowledge several categories of clients. Here, the most common category of clients is young people and children and their families (e.g. Breyette & Hill, Citation2015; Cwikel & Friedmann, Citation2020; Dolinsky & Helbig, Citation2015), where social media and digital communication are common tools. Other categories that seem to be prioritised are those that relate to the context of handling clients within a clinical setting (Mishna et al., Citation2021; Reamer, Citation2015). So, what categories and power relations are silenced? Although this question is difficult to answer unambiguously due to the categories being social constructions, we identify some broad categories. Poverty is hardly mentioned, and neither are persons of old age, victims of violence, or persons with disabilities. Gender, sexuality, ethnicity, or class and their importance for the relationships are hardly ever mentioned either. Exceptions are where gender is to some degree present, but not as a problematised category (see Mishna et al., Citation2021; Kellen et al., Citation2015), and when sexuality is discussed in terms of a vignette with a same-sex couple (Kellen et al., Citation2015). Ethnicity among social workers is to some degree discussed in Mishna et al. (Citation2021, p. 10):

Participant ethnicity was significantly related to informal ICT use in the U.S., with social workers who identified as Indigenous, Black or another ethnicity engaging in informal ICT use at a significantly lower rate than social workers who identified as White.

Overall, clients are not given a voice in 16 articles on ethics, and specific categories of clients, and thus power relations are obscured and consequently objectified. We believe that this makes the research less useful and in the worst-case scenario reproduces inequality rather than empowering clients in the relationship with social workers within digitalised social work.

Three theoretical perspectives on the social worker-client relationship

Half of the articles (25) are empirical studies without explicit use of theory. Here, the typical study is qualitative and uses inductive data analysis on a digital tool to present practice-related results such as its advantages and disadvantages for the relationship and for social work practice (see also quantitative empirical studies, e.g. Murray et al., Citation2015). For example, Cooner et al. (Citation2020, p. 138) study how social workers ‘established, developed and sustained relationships with service users in long-term casework’ through the use of Facebook. Although relationships are discussed in a literature review, they are not theoretically defined to understand the collected data. The sparse use of theory may be a characteristic of a research field in development. In this theme, we thus turn to the 25 articles in the other half and show how their use of theory to analyse empirical data or discuss a certain topic, can put digitalisation’s significance for relations into new perspectives. We grouped the articles in three perspectives – the interpersonal (10), the contextual (9), and the critical (6).

The interpersonal perspective is characterised by understanding relations as psychosocial interactions and communication between people. These articles often refer to the writings of Howe (Citation1998), Trevithick (Citation2003), and Ruch (Citation2005) and to relationship-based, therapeutic, or psychodynamic social work. Digital tools may transform and shape these relations in different ways. For example, Turner (Citation2016, p. 323) argues that social media fulfils many of Trevithick’s (Citation2003) essential requirements of relationship-building and may contribute to ‘practitioners developing and sustaining supportive professional relationships in unique and challenging situations (Ruch, Citation2005)’. Similarly, Lopez (Citation2015) explores the internet in therapy through the therapeutic alliance, i.e. ‘ … the quality of the working relationship between client and therapist to achieve positive therapy outcomes’ (p. 190), including aspects such as empathy, positive regard, emotional validation, trust, and genuineness (cf. van de Luitgaarden and van der Tier’s, Citation2018 analytical framework for a working relationship).

Some articles in the interpersonal perspective use specific concepts to analyse relations. ‘Social presence’ explains how human relationships can be developed and maintained through ‘a communication process, a mutual activity that serves as the basis for the interaction, and some type of emotional or psychological involvement related to the activity’ (Lopez, Citation2015, p. 190). Lopez (Citation2015) finds that internet-based resources can complement traditional therapy due to their influence on the therapeutic alliance. Also, Simpson (Citation2017) investigates the role of mobile communication in professional working relationships, defining social presence as the projected presence of a person (a Facebook profile), the sense of the other (a telephone conversation), and co-presence (a psychological connection is established). Experiencing presence at different levels with different technologies thus enables social workers to use a variety of communication methods (cf. Byrne et al., Citation2019 for ethical dilemmas). Similarly, Leung et al. (Citation2017) argue that social workers must be socially present by being present to the online generation and community. Overall, social presence highlights how people feel connected when separated by time or space and the possibilities and responsibilities of digitalisation for the relationship.

Another concept is ‘affordances’, which suggests that an object’s utility depends not only on its intrinsic features but also on social actors’ intentions and experiences (Chan & Ngai, Citation2019, p. 160). Bolin and Sorbring (Citation2017) use the concept to conceptualise support provision and to investigate the factors that can facilitate children’s active seeking of help from on-site social workers in school environments. Similarly, Chan and Ngai (Citation2019) explore clients’ experiences that might not have been possible without technology, e.g. online status indicators that improve service accessibility, emphasising that the utility of social media also depends on the perceptions of social media users.

While the interpersonal perspective addresses relations as communication and interaction, the contextual perspective is characterised by emphasising digitalisation as an external policy that may threaten relational and narrative social work. It shifts the analytical lens to how the administrative, organisational, or political context affects the social worker-client relationship. Social workers use their ‘discretion’, i.e. the freedom, autonomy, and authority to make judgements as one sees fit (Lipsky, Citation2010), to ‘ … develop strategies to shape, reshape and even bend regulations and procedures for using EISs (Electronic Information Systems) in social work practice, aiming precisely to achieve a responsive social work practice’ (Devlieghere & Roose, Citation2018, p. 651; cf. Devlieghere et al., Citation2020; see also Breit et al., Citation2020 on digital coping). Such strategies can result in a gap between digitalisation as policy and practice (cf. De Witte et al., Citation2016). Moreover, some authors draw on science and technology studies to investigate the significance of artefacts such as computers for the social worker-client relationship (Høybye-Mortensen, Citation2015) or the construction of children as a target group through ICT (Lecluijze et al., Citation2015). Other contributions concern the ‘informatisation’ of social work, i.e. ‘the substantial use of digital processing, storing and transmitting information’ (Recmanová & Vávrová, Citation2018, p. 877; see Eito Mateo et al., Citation2018 for a theoretical reflection) and the production of new forms of social interaction and sense making through spatial dialectics (Jeyasingham, Citation2020). In all, this perspective goes beyond the two-person relationship in order to understand the relationship through its context.

Finally, some studies can be loosely grouped in a critical perspective characterised by a critical and societal lens on digitalisation’s influence on the preconditions for social work practice and its subsequent ethical challenges. Surveillance is explored in Foucauldian terms to understand Facebook as an informal surveillance technique (Lim, Citation2017) as well as how technology can transform everyday life in elder care (Mortenson et al., Citation2015). Relatedly, Lynch et al. (Citation2019) use discourse analysis to highlight the conflict between a telecare policy and the experiences of practitioners and clients. Finally, social justice is a basis for community participation where practice resonates with the informal potential of social media (Shevellar, Citation2017; see also Boddy & Dominelli, Citation2017 for online guidelines for social justice).

Overall, while half of the articles represents empirical research designs, the other half show a variety of theoretical approaches to studying the social worker-client relationship.

Discussion and conclusion

We generated three themes on how research on social work from 2015 to 2020 describes and analyses digitalisation’s significance for the social worker-client relationship.

On the one hand, our findings show a technological optimism. Digital tools can initiate, maintain, and change interpersonal relationships in new ways that improve social work practice and clients’ lives. Tools can improve the accessibility to welfare services and engage with hard-to-reach groups such as youths on their own terms. While face-to-face interactions may decrease and ethical issues may arise, such problems are not seen to render social work practice informational (Parton, Citation2009) or technical (Devlieghere & Roose, Citation2018), and they are possible to deal with through education and ethical consideration in a reflexive practice. In this view, where empirical designs and interpersonal perspectives are more common, digital tools are not an example of Howe’s (Citation1998) fear of the consequences of ‘lawyers, managers and proceduralists’ in social work. Rather, they are instrumental to the social worker-client relationship.

On the other hand, digital tools are also viewed as a threat to relational social work. Our results show how power dynamics in the relationship are affected and altered through standardisation, multidirectional surveillance, and professionals’ strategies for discretion. Also, the lack of client voices and the obscuring of power relations when studying ethical issues within digitalised social work, may reproduce inequality rather than empowering clients. As Blennberger (Citation2005) argues, ethical ventures hold the risk of individualisation that obscures structural causes of social problems and instead promotes paternalism and moralism. Such insights are possible by recognising the social worker-client relationship as a broad and multi-layered concept in an organisational, professional, and political setting and by using contextual and critical perspectives. Future research could use critical perspectives to bring forth clients’ voices, whose participation in society is becoming more dependent on e-technology (Shevellar, Citation2017).

Moreover, studying digitalisation’s significance for the social worker-client relationship helps us to understand what is considered important and not in social work today and to identify the changes in emphasis and negotiations of the values that are taken for granted. Future research could thus target whether challenges of digitalisation to the relationship as an integral part of social workers’ professional identity and purpose (Rollins, Citation2020, p. 395), are balanced by potential gains of accountability and legal security.

In this rapidly developing research area, the width of theoretical perspectives may be a strength and used to further understand such preconditions for the social worker-client relationship. Theorisation may hinder traditional views of the relationship to be unintentionally reproduced and instead problematised. For example, exploring the significance of class, gender and race can help highlight structural causes to social problems that may be relevant to the use of digital tools. In this way, theorisation can convey tools for increasing social work organisations’ ideation and self-reflection (Payne, Citation2014). Hence, we urge researchers to be explicit about how they understand and conceptualise the social worker-client relationship to make it easier to situate and compare findings and analyses.

Furthermore, we also suggest research on the mutually affecting interactions between the social worker-client relationship and the organisational and professional context. As digitalisation becomes more institutionalised, it is no longer solely an external and separate novelty affecting the relationship. Finally, we argue that comparative research designs are useful to understanding how different digital tools shape different aspects of the social worker-client relationship in different settings. While we are ourselves guilty of grouping different tools within the process of digitalisation, we adhere to the view that digitalisation is not a homogeneous concept.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kettil Nordesjö

Kettil Nordesjö is associate senior lecturer at the Department of Social Work, Malmö University. His research interests concern digitalisation, standardisation and evaluation in social work policy and practice. He currently does research on the significance of digitalisation for the social worker-client relationship and the evaluation and implementation of social investment practices in social work.

Gabriella Scaramuzzino

Gabriella Scaramuzzino is a researcher at the School of social work, Lund University, Sweden. Her general research interests are in the areas of digitalisation, civil society and working life. She has been involved in several research projects on how the increased digitisation affects social work.

Rickard Ulmestig

Rickard Ulmestig is a former social worker and currently associate professor at the Department of Social Work, Linnaeus University, and does critical research on social assistance, activation, and digitalisation. He is a research leader for AKTIV that focus on research with a relevance for social work practice (kmaktiv.org).

Notes

1 Search string: noft(technolog* OR tech* OR cyber* OR virtual OR online OR digi* OR digitalisation OR digitisation OR digitalization OR digitization OR ICT* OR “E-Social work*” OR “E-services” OR “E-govern*” OR Automati* Automatization OR Automation OR robot* OR AI OR “artificial intelligence” OR Algorithm* OR Computer* OR Smartphone* OR App OR Internet OR “Social media” OR “social networking”) AND noft(“social work*” OR “social service*”) AND noft(relation* OR interact* OR communicat*).

References

- Blennberger, E. (2005). Etik i socialpolitik och socialt arbete [Ethics in social policy and social work]. Studentlitteratur.

- Boddy, J., & Dominelli, L. (2017). Social media and social work: The challenges of a new ethical space. Australian Social Work, 70(2), 172–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1224907

- Bolin, A., & Sorbring, E. (2017). The self-referral affordances of school-based social work support: A case study. European Journal of Social Work, 20(6), 869–881. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2016.1278521

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/13620-004.

- Breit, E., Egeland, C., Loberg, I. B., & Rohnebaek, M. T. (2020). Digital coping: How frontline workers cope with digital service encounters. Social Policy & Administration, 1–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12664

- Brennen, J. S., & Kreiss, D. (2016). Digitalization. In K. B. Jensen, E. W. Rothenbuhler, J. D. Pooley, & R. T. Craig (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of communication theory and philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118766804.wbiect111

- Breyette, S. K., & Hill, K. (2015). The impact of electronic communication and social media on child welfare practice. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 33(4), 283–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2015.1101408

- Brusoski, M., & Rosen, D. (2015). Health promotion using tablet technology with older adult African American methadone clients: A case study. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 33(2), 119–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2014.989297

- Byrne, J., & Kirwan, G. (2019). Relationship-based social work and electronic communication technologies: Anticipation, adaptation and achievement. Journal of Social Work Practice, 33(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2019.1604499

- Byrne, J., Kirwan, G., & Mc Guckin, C. (2019). Social media surveillance in social work: Practice realities and ethical implications. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 37(2-3), 142–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2019.1584598

- Chan, C., & Ngai, S. S.-y. (2019). Utilising social media for social work: Insights from clients in online youth services. Journal of Social Work Practice, 33(2), 157–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2018.1504286

- Cooner, T. S., Beddoe, L., Ferguson, H., & Joy, E. (2020). The use of Facebook in social work practice with children and families: Exploring complexity in an emerging practice. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 38(2), 137–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2019.1680335

- Cwikel, J., & Friedmann, E. (2020). E-therapy and social work practice: Benefits, barriers, and training. International Social Work, 63(6), 730–745. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872819847747

- De Witte, J., Declercq, A., & Hermans, K. (2016). Street-level strategies of child welfare social workers in Flanders: The use of electronic client records in practice. British Journal of Social Work, 46(5), 1249–1265. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcv076

- Denby, R. W., Gomez, E., & Alford, K. A. (2016). Promoting well-being through relationship building: The role of smartphone technology in foster care. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 34(2), 183–208. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2016.1168761

- Devlieghere, J., & Roose, R. (2018). Electronic Information Systems: in search of responsive social work. Journal of Social Work, 18(6), 650–665. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017318757296

- Devlieghere, J., Roose, R., & Evans, T. (2020). Managing the electronic turn. European Journal of Social Work, 23(5), 767–778. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2019.1582009

- Dolinsky, H. R., & Helbig, N. (2015). Risky business: Applying ethical standards to social media use with vulnerable populations. Advances in Social Work, 16(1), 55–66. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18060/18133

- Duffy, F. (2017). A social work perspective on how ageist language, discourses and understandings negatively frame older people and why taking a critical social work stance is essential. British Journal of Social Work, 47(7), 2068–2085. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw163

- Eito Mateo, A., Gómez Poyato, M. J., & Marcuello Servós, C. (2018). e-Social work in practice: A case study. European Journal of Social Work, 21(6), 930–941. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1423552

- European commission. (2020). Shaping Europe’s digital future. https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/content/european-digital-strategy.

- Gillingham, P. (2015). Electronic Information Systems in human service organisations: The what, who, why and how of information. British Journal of Social Work, 45(5), 1598–1613. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu030

- Gough, D., Thomas, J., & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

- Gray, M., Midgley, J., & Webb, S. A. (2012). The Sage handbook of social work. Sage.

- Groshong, L., & Phillips, D. (2015). The impact of electronic communication on confidentiality in clinical social work practice. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-015-0527-4

- Hobbis, S. K. (2018). Mobile phones, gender-based violence, and distrust in state services: Case studies from Solomon Islands and Papua New Guinea. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 59(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12178

- Hodge, H., Carson, D., Carson, D., Newman, L., & Garrett, J. (2017). Using internet technologies in rural communities to access services: The views of older people and service providers. Journal of Rural Studies, 54, 469–478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2016.06.016

- Howe, D. (1998). Relationship-based thinking and practice in social work. Journal of Social Work Practice, 12(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02650539808415131

- Høybye-Mortensen, M. (2015). Social work and artefacts: Social workers’ use of objects in client relations. European Journal of Social Work, 18(5), 703–717. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2014.930816

- IASSW. (2018). Global social work statement of ethical principles. https://www.iassw-aiets.org/global-social-work-statement-of-ethical-principles-iassw/.

- Jeyasingham, D. (2020). Entanglements with offices, information systems, laptops and phones: How agile working is influencing social workers’ interactions with each other and with families. Qualitative Social Work, 19(3), 337–358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325020911697

- Kellen, K., Schoenherr, A. M., Turns, B., Madhusudan, M., & Hecker, L. (2015). Ethical decision-making while using social networking sites: Potential ethical and clinical implications for marriage and family therapists. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 43(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01926187.2014.942203

- La Rose, T. (2019). Limiting relationships through sousveillance video based digital advocacy: Multi-modal analysis of The nervous CPS worker. Journal of Social Work Practice, 33(2), 233–243. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2019.1597693

- Lamberton, L., Devaney, J., & Bunting, L. (2016). New challenges in family support: The use of digital technology in supporting parents. Child Abuse Review, 25(5), 359–372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2451

- Lecluijze, I., Penders, B., Feron, F. J. M., & Horstman, K. (2015). Co-production of ICT and children at risk: The introduction of the child index in Dutch child welfare. Children and Youth Services Review, 56, 161–168. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.07.003

- Lee, O. E.-K., & Kim, D.-H. (2019). Bridging the digital divide for older adults via intergenerational mentor-up. Research on Social Work Practice, 29(7), 786–795. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731518810798

- Leung, Z. C. S., Wong, S. S. K., Lit, S.-w., Chan, C., Cheung, F., & Wong, P.-l. (2017). Cyber youth work in Hong Kong: Specific and yet the same. International Social Work, 60(5), 1286–1300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872815603784

- Lim, S. S. (2017). Youth workers’ use of Facebook for mediated pastoralism with juvenile delinquents and youths-at-risk. Children and Youth Services Review, 81, 139–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.08.004

- Lipsky, M. (2010). Street-level bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the individual in public services. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Lolich, L., Riccò, I., Deusdad, B., & Timonen, V. (2019). Embracing technology? Health and social care professionals’ attitudes to the deployment of e-health initiatives in elder care services in Catalonia and Ireland. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 147, 63–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.06.012

- Lopez, A. (2015). An investigation of the use of internet based resources in support of the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(2), 189–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0509-y

- Lynch, J. K., Glasby, J., & Robinson, S. (2019). If telecare is the answer, what was the question? Storylines, tensions and the unintended consequences of technology-supported care. Critical Social Policy, 39(1), 44–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018318762737

- Macdonald, G., Kelly, G. P., Higgins, K. M., & Robinson, C. (2017). Mobile phones and contact arrangements for children living in care. British Journal of Social Work, 47(3), 828–845. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw080

- Mackrill, T., & Ebsen, F. (2018). Key misconceptions when assessing digital technology for municipal youth social work. European Journal of Social Work, 21(6), 942–953. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2017.1326878

- Mackrill, T., & Ørnbøll, J. K. (2019). The MySocialworker app system:A pilot interview study. European Journal of Social Work, 22(1), 134–144. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1469471

- Mattison, M. (2018). Informed consent agreements: Standards of care for digital social work practices. Journal of Social Work Education, 54(2), 227–238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2017.1404529

- Mishna, F., Milne, E., Bogo, M., & Pereira, L. F. (2020). Responding to covid-19: New trends in social workers’ use of Information and Communication Technology. Clinical Social Work Journal, 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-020-00780-x

- Mishna, F., Sanders, J., Fantus, S., Fang, L., Greenblatt, A., Bogo, M., & Milne, B. (2021). # socialwork: Informal use of Information and Communication Technology in social work. Clinical Social Work Journal, 49(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-019-00729-9

- Mortenson, W. B., Sixsmith, A., & Woolrych, R. (2015). The power(s) of observation: Theoretical perspectives on surveillance technologies and older people. Ageing & Society, 35(3), 512–530. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X13000846

- Murray, K. W., Woodruff, K., Moon, C., & Finney, C. (2015). Using text messaging to improve attendance and completion in a parent training program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(10), 3107–3116. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0115-9

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Parton, N. (2009). Challenges to practice and knowledge in child welfare social work: From the ‘social’ to the ‘informational’? Children and Youth Services Review, 31(7), 715–721. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.01.008

- Payne, M. (2014). Modern social work theory. Oxford University Press.

- Räsänen, J.-M. (2015). Emergency social workers navigating between computer and client. British Journal of Social Work, 45(7), 2106–2123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu031

- Reamer, F. G. (2013). Social work in a digital age: Ethical and risk management challenges. Social Work, 58(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swt003

- Reamer, F. G. (2015). Clinical social work in a digital environment: Ethical and risk-management challenges. Clinical Social Work Journal, 43(2), 120–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-014-0495-0

- Recmanová, A., & Vávrová, S. (2018). Information and Communication technologies in interventions of Czech social workers when dealing with vulnerable children and their families. European Journal of Social Work, 21(6), 876–888. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1441137

- Rollins, W. (2020). Social worker–client relationships: Social worker perspectives. Australian Social Work, 73(4), 395–407. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2019.1669687

- Rönkkö, K. (2018). An activity tracker and its accompanying app as a motivator for increased exercise and better lleeping habits for youths in need of social care: Field study. Jmir Mhealth and Uhealth, 6(12), e193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.9286

- Ruch, G. (2005). Relationship-based practice and reflective practice: Holistic approaches to contemporary child care social work. Child & Family Social Work, 10(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2005.00359.x

- Shaw, I. G. R., & Holland, S. (2014). Doing qualitative research in social work. Sage.

- Shevellar, L. (2017). E-technology and community participation: Exploring the ethical implications for community-based social workers. Australian Social Work, 70(2), 160–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2016.1173713

- Simpson, J. E. (2017). Staying in touch in the digital era: New social work practice. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 35(1), 86–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2017.1277908

- Sinha, S., Shrivastava, A., & Paradis, C. (2019). A survey of the mobile phone-based interventions for violence prevention among women. Advances in Social Work, 19(2), 493–517. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18060/22526

- Trevithick, P. (2003). Effective relationship-based practice: A theoretical exploration. Journal of Social Work Practice, 17(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/026505302000145699

- Turner, D. (2016). ‘Only connect’: Unifying the social in social work and social media. Journal of Social Work Practice, 30(3), 313–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2016.1215977

- van de Luitgaarden, G., & van der Tier, M. (2018). Establishing working relationships in online social work. Journal of Social Work, 18(3), 307–325. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316654347