ABSTRACT

In Sweden, a country with one of the highest public spending on long term care, there is also extensive informal care, i.e. unpaid care by family, friends, or neighbours. In this article, we explore the spectrum of informal caring using data from a nationally representative survey of caregivers in the Swedish population. We describe three different caregiver profiles and analyse them in relation to their panorama of care, i.e. the extent to which caring is shared with other formal- and informal co-carers. The first profile, the co-habitant family carer, consists of caregivers providing help for someone in the same household with special care needs, and were mostly alone in intensive caregiving. The second profile, persons in the care network, consists of caregivers providing help to someone with care needs in another household. They have a network of both informal and formal co-carers. Finally, the helpful fellowman consists of caregivers providing help for someone without special needs in another household. In developing relevant carer support, it is important to acknowledge that caregivers are not a homogenous group. Thus, to fulfil national ambitions to support carers across the board, policy and practice need to have a diverse group of carers in mind.

SAMMANFATTNING

I Sverige som är ett land med en av de högsta offentliga utgifterna för äldreomsorg, finns det också omfattande informell omsorg. I denna artikel studerar vi spektrumet av informell omsorg utifrån en nationellt representativ undersökning. Vi beskriver och analyserar tre olika profiler av omsorgsgivare. Den första profilen, anhörigvårdaren, består av de som ger hjälp till någon i samma hushåll med särskilda omsorgsbehov och var ofta ensamma i sitt omsorgsåtagande. Den andra profilen, omsorgsgivarna, består av de som ger hjälp till någon med omsorgsbehov i ett annat hushåll. De har ett nätverk av både informella och formella omsorgsgivare. Den tredje profilen består av den aktive medborgaren som ger hjälp till någon utan särskilda omsorgsbehov i ett annat hushåll. Vid utvecklingen av anhörigstöd är det viktigt att se att detta inte är en homogen grupp. För att uppfylla nationella mål med att utveckla anhörigstöd behöver både politik och praktik utforma stöd som kan passa en rad olika profiler av informella hjälpgivare.

NYCKELORD:

Introduction

The sharing of care responsibilities between the private and public spheres has been a concern of care- and welfare research in many countries (AARP, Citation2020). It is estimated that 10–25% of Europe’s population regularly provide informal care, even though one’s personal identification as a carer and the definitions of carers vary in different contexts (Zigante, Citation2018). In our context of Sweden, which is one of the countries with the highest public spending on long term care (OECD, Citation2013), there is also extensive informal care, or unpaid care by family, friends, or neighbours. In this article, we will explore the spectrum of informal caring using data from a nationally representative survey of caregivers in the Swedish population. We will describe different caregiver profiles that emerged from the survey and analyse them in relation to the availability of other formal- and informal co-carers – i.e. what we call their panorama of care.

In this article, we use the term ‘caregiver’ to represent a broad range of actors and activities involved in caring. In early care research, the care receiver’s functional status of not being able to perform tasks oneself was a premise in whether an activity was defined as ‘care’ or ‘service’ (Wærness, Citation1996). From this perspective, ‘carers’ were analogous to primary carers, or persons with the main responsibility for providing care for another person. Care was also associated with providing personal and hands-on tasks over long periods of time, as reflected in the concept of a family member’s caregiving career (Pearlin & Aneshensel, Citation1994). Today, care research more broadly includes different contexts and actors. It now makes more sense to define an informal caregiver as a person who provides regular unpaid help, or arranges for help, to a relative or friend within our outside one’s household, for various reasons that include – but are not necessarily limited to – illness, disability, or old age (Swartz & Collins, Citation2019). Help with housework, paperwork, or taking the person out of the house, as well as activities not limited to a single task such as planning, anticipating, and assessing the quality of care, have also been increasingly acknowledged as part of informal caring (McKie et al., Citation2002).

Demographic factors may have contributed to the need to include other informal caregivers in research. Some argue that higher life expectancy, resulting in several generations living simultaneously, tend to broaden the individual’s network where care is exchanged (Antonucci et al., Citation2007; Bengtson et al., Citation2017; Sundström, Citation2019). Modern changes in family composition, for example, remarriage and complex family structures with one’s own and shared children, also challenge the concept of a ‘usual’ family caregiver (Bengtson et al., Citation2017; Bildtgård & Öberg, Citation2017). Likewise, the existence of adult children or a cohabiting partner as primary carers can no longer be taken for granted. In Europe today, 10% of older people are childless (Deindl & Brandt, Citation2017), and in Sweden, 1.8 million people live alone without a co-habiting partner (SCB, Citation2020). In such contexts, siblings, extended family members, friends and neighbours may be more likely caregivers, and it is possible that there is no single primary carer.

The broader definition of caring has also led to a shift in focus from the care receiver’s inability to perform tasks, to the help-giving tasks themselves. An alternative to ‘care’ and ‘service’ emerged, that instead categorised care tasks at the ‘lighter’ or ‘heavier’ ends of caregiving (Jeppsson Grassman, Citation2001; Szebehely, Citation2005). It has long been pointed out that even a ‘little bit of help’ has considerable value to care receivers (Clark et al., Citation1998). Conversely, workaday asks are the most common activities reported by caregivers (Horowitz, Citation1985; Parker & Lawton, Citation1990). The visibility household chores and keeping an eye on relatives in care research, confirms that these kinds of activities have moved from being taken-for-granted to being regarded as actual caregiving (Plöthner et al., Citation2019). Welfare reforms may have also contributed to making ‘lighter’ care tasks visible in public debate. As welfare systems are forced to ration limited resources, minor care tasks regularly performed by family members and friends to people with less extensive help needs, have increased in importance (Eby et al., Citation2017; Wolff & Kasper, Citation2006).

With the expansion of the network of possible persons giving informal care and the diversification of tasks defined as informal caring, it is necessary to broaden our understanding of different carer groups. Thus, extending on an earlier typology that looked at the type and extent of care provided by intra-household and extra-household informal caregivers (Jeppsson Grassman, Citation2001; Szebehely, Citation2005), our present analysis will describe different typologies but also analyse them in relation to their panorama of care, i.e. the help that is provided by other co-carers. This knowledge can help us get an alternative picture of the different burdens and responsibilities of caring.

Conceptual framework

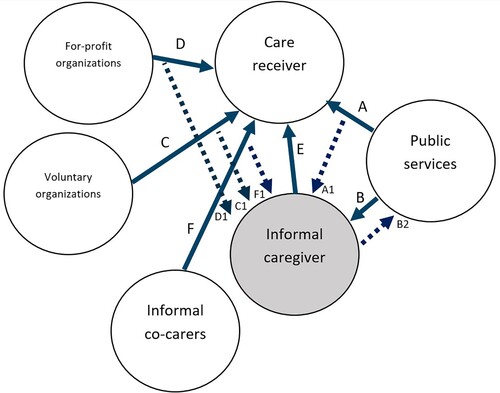

We introduced the term panorama of care in another empirical work (Jegermalm & Sundström, Citation2015), as a conceptual frame to map overlapping care responsibilities between public services, informal carers, and for-profit and voluntary organisations. Initially, the panorama of care was discussed from the care receiver’s perspective, to see the extent to which they acquired help from different sources. However, because the data was in fact reported by informal caregivers, we realised that the panorama of care reflected, to an equal extent, the caregivers’ network of co-carers. Focusing in this article on the informal caregiver’s perspective, we visualise our understanding of the panorama of care in , showing how there are multi-directional relationships between welfare state, informal caregivers, and care receivers. Our examples stem mainly from a Swedish context, even though the panorama of care model itself is applicable in other country settings.

Figure 1. A visual representation of the panorama of care, from the informal caregiver's perspective. Solid lines represent direct forms of exchange. Dotted lines represent how direct exchanges between actors can further be understood as an indirect positive exchange.

In , solid lines represent direct forms of exchange. For formal care, the public sector is responsible for organising publicly financed services for people with care needs (A). The public sector can also provide direct carer support to informal caregivers through interventions such as health-promoting activities, self-help groups and economic compensation (B) (Brimblecombe et al., Citation2018; Takter, Citation2020; Winqvist, Citation2014). Other actors in the direct provision of formal care are voluntary and for-profit organisations (C and D). In Sweden, these actors have had an increasing role – yet not as the primary player – as operators of care facilities or providers of welfare services under government contracts (Jegermalm & Sundström, Citation2015; von Essen et al., Citation2020). In other European countries with welfare partnership- or liberal models such as Austria, Germany, France and the UK, the proportion of non-profit welfare providers are much higher, and employs up to 25% of the workforce within the welfare sector (Sivesind, Citation2017).

Unpaid informal caring is another form of direct exchange (E). Keeping to a broad definition of care, we emphasise that our model does not make a distinction between primary or secondary carers. Indeed, several studies show that primary and secondary carers, although differing in their level of caregiving and financial burden, experience very similar strains and emotional rewards from caregiving (Barbosa et al., Citation2011; Gonçalves-Pereira et al., Citation2020; Marino et al., Citation2018). This said, we do consider the presence of other informal co-carers who provide help alongside the informal caregiver, regardless of their relation to the care receiver or to each other (F). Thus, our understanding of the panorama of care aligns with Kemp et al.’s (Citation2013) concept of convoy of care, defined as an ‘evolving collection of individuals who may or may not have close personal connections to the recipient or to one another’ (p. 5), and who together provide a changing variety of care tasks.

Dotted lines in represent how the direct exchanges between two actors can additionally be regarded as positive indirect exchanges for others in the panorama. For example, care provided by public services is known to double as indirect support for informal caregivers (A1) (Brimblecombe et al., Citation2018; Twigg & Atkin, Citation1994). In many cases, informal caregivers prefer increased services for the person receiving care, as the main form of carer support (Gatz et al., Citation1990; Lethin et al., Citation2019; Plöthner et al., Citation2019). Care provided by other formal and informal co-carers (C1, D1, F1) also supports the individual caregiver. It has been shown, for example, that having other informal co-carers impact on how role overload, as well as positive rewards from caregiving, are experienced (Cheng et al., Citation2013).

Informal caregiving, in turn, also has indirect positive consequences to the formal care system since informal caregivers substitute or complement public services (B2). Illustrating this point is a Swedish government report that argued for carer support from an economic standpoint, stating that ‘informal caring is so extensive that a reduction of only a few percent would have numerous consequences for the formal care provision’ (NBHW, Citation1994). In other country settings such as in the US, there is a similar debate on whether to provide tax incentives for informal carers, as informal caring has been shown to reduce formal care expenditures such as Medicare (Van Houtven & Norton, Citation2008). Our understanding of the panorama of care, therefore, acknowledges the benefits of caring for the care receiver, the informal caregivers, and the state, in their various relationships of interdependence.

Since we visualise care exchanges as multidirectional, different actors can be pivot points in understanding care relationships. However, in this article, we are especially interested in understanding the panorama of care from the informal carers’ perspectives.

Aim

Using data from a nationally representative survey of carers in Sweden, our aim is to distinguish different carer profiles based on the nature and frequency of care tasks they provide and to analyse these different profiles’ panoramas of care.

In our analysis, we studied the relative sizes of these profiles and the frequency of care given at the ‘lighter’ and ‘heavier’ ends of caregiving. We also compared our results to previous survey data, to see if the relative sizes of these groups have changed over time.

Materials and methods

Study design

As part of a government-commissioned survey, Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College has been conducting nationally representative surveys about the types and extent of informal caregiving since 1992 (Jegermalm & Jeppsson Grassman, Citation2009; Jegermalm & Sundström, Citation2017; von Essen et al., Citation2020). This current article uses data from the latest survey in 2019, but the previous surveys from 2009 and 2014 used similar questions and have also been used to make comparisons over time. The Origo group, a research company with a long experience of telephone surveys, was commissioned to conduct the 2019 survey on behalf of Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, which is the institution responsible for the survey data. The Origo group had also conducted the survey in 2014, while Statistics Sweden conducted the survey in 2009.

For all survey waves, a random representative sample of Swedish residents aged 16–84 was drawn from the population register. The register contains information about sex, marital status, and income. In the 2019 survey, the net sample was 1972 individuals, and the survey response rate was 56% (n = 1108). An international overview of telephone-based opinion- and market studies has shown decreasing response rates in many countries in recent decades, which was also true for our case (Kennedy & Hartig, Citation2019). To increase response rates, our surveys followed a standard follow-up procedure by telephone and post, but non-respondents were not asked to give a reason for not participating. To check for the data’s reliability, we analysed the demographic variables of the participating group, and could conclude that participants in terms of age, sex, and marital status, were representative of the national population (See also Holbrook et al., Citation2008).

Data collection and analysis

Three screening questions were used to identify informal carers among the sample. Firstly, participants were asked if they helped someone outside their household (neighbours, friends, or colleagues) at least once a week with activities such as housework, personal care, and transport, or whether they kept an eye on someone. If they answered yes, they were asked a second question of whether this help was being given to someone who was old, sick, had a disability or ‘in need of special care in the form of personal and physical care’. Finally, respondents were asked if they were caring for someone in the same household who was old, sick, had a disability or ‘in need of special care in the form of personal and physical care’. Fifty-two per cent of the sample answered yes to at least one of these questions (n = 585) and were identified in our study as providing informal care. We refer to this group as informal caregivers.

The questionnaire for informal caregivers then used a structured multiple-choice approach. Since it is possible that respondents helped several individuals, they were asked to think about the care receiver that they helped the most. This was done to be able to conceptually differentiate between the mainly intra- and extra-household caregivers. The respondents were then asked about their relationship with the care receiver in question, the care tasks they performed, and the amount of time spent performing these tasks. There was no distinction made on whether the respondents were primary or secondary carers. Instead, respondents were asked about the additional help (if any) that the care receiver obtained from other co-carers such as relatives, neighbours, friends, public services, voluntary organisations, for-profit agencies. Finally, they were asked about self-rated health and whether they had an informal social network, defined as a context where they met at least three people regularly (friends, acquaintances, or an activity group) in their free time.

A Chi-square test was used to investigate whether discrete variables such as sex, marital status and relationships varied significantly between profiles of intra-household and extra-household caregivers. Continuous variables such as number of hours of help given were tested with ANOVA one-tailed variance analysis to assess significant differences between categories of caregivers.

Ethical considerations

The survey design and the collected data contained no information that could be connected to any individual participant (such as a personal identification numbers), and as such, the survey did not require any ethical vetting by an ethical board. The database is available at Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, where it is electronically stored in such a way that only researchers intending to analyse the data are granted access to the material. The university college and the organisations commissioned to undertake the surveys have also complied with the ethical principles established by the Swedish Research Council (Citation2017). The participants had to be informed of the survey’s aims and had to give their consent to participate. Participants were informed that their answers were anonymous and would only be analysed at a group level. No individual participant could be identified by name, address or in any other way, by the researchers. Likewise, all survey information is handled in accordance with GDPR (the General Data Protection Regulation) regarding storage- and archiving policies at the responsible university.

Results

We categorised three caregiver profiles based on the structure of the screening questions, and we analysed each of these profiles in relation to their panorama of care. The first profile, the co-habitant family carer, consists of caregivers providing help for someone in the same household with special care needs. The second profile, persons in the care network, consists of caregivers providing help for someone not living in the same household but has special care needs. Finally, the helpful fellowman consists of caregivers providing help and care for someone not living in the same household that has no special care needs.

presents some characteristics of these profiles. Of the 585 informal caregivers, 81 were co-habitant family carers (7% of the total 1108 respondents), 164 were part of a care network (15% of total respondents), and 340 were helpful fellowmen (30% of total respondents). There were more men than women in all profiles, but the overall pattern – like that in the 2009 and 2014 surveys – was that it is just as likely among women and men to belong to the different caregiver profiles. The profiles were also similar regarding their educational level.

Table 1. Characteristics of three profiles of caregivers, the helpful fellowman, the care network and the co-habitant family carer.

further presents the three profiles based on their relationship with the care receivers, care receiver characteristics, and the types of care tasks usually performed. ‘Invisible’ tasks such as ‘keeping an eye’ or ‘keeping company’ are included. Minor tasks such as repair work and gardening are also differentiated in our data from help with household chores (housework). In , we show the reported formal and informal co-carers.

Table 2. Characteristics of the care receiver and types of help received, by respective caregiver profile.

Table 3. Reported co-carers, by respective caregiver profile.

Co-habitant family carer

The first caregiver profile, the co-habitant family carer, embodies the iconic cases of extensive caregiving. As shown in , the pattern of time spent on caring per month shows a distinct pattern of being substantially involved in caregiving and providing more than four times the amount of care per month than the other two groups.

The co-habitant family carer has the oldest age profile among the informal caregivers, with a quarter between 75 and 84 years old. They were most likely to be married. Half of the persons belonging to this profile provided care for a spouse (often a person older than 75 years), and about one third provided care for a co-habiting child (often a child under 17 years). shows that providing personal care is common among co-habitant family carers, both within the group and compared to the other caregiver profiles, where it was up to twice as likely. It is also common for these caregivers to provide tasks such as keeping company and housework.

When we considered their panorama of care, the survey showed it was most common for co-habitant family caregivers to be alone in providing care, with almost 6 out of 10 reporting no co-carers (). Around a quarter in this profile reported additional help from another relative, less than 10% reported that the care receiver had additional help from a neighbour/friend, and only 16% reported that the care receiver obtained formal care. Our results show a similar pattern of care tasks and relationships with care receivers as the surveys from 2009 and 2014. However, it also seems that co-habitant family carers without any co-carers have increased from around 45% of the group in 2009 and 2014, to 57% in this present survey (von Essen et al., Citation2020). Co-habitant family carers do report have informal networks (39%) and they rate their health as very good or good (71%), although they do so to a lesser degree compared to the two other profiles ().

The care network

One of the two groups providing regular help for a person outside their own household provided care to someone who is ‘in need of special care in the form of personal and physical care’. We have named this caregiver profile the care network, with reference both to the care tasks they performed and to their panorama of care, which we will describe below.

As seen in , persons in the care network provide a substantial amount of personal care (25%), and more hands-on help such as housework, paperwork and accompanying the care receiver outside the house, compared to the other extra-household profile the helpful fellowman. Keeping the care receiver company was the most reported care task in this profile (66%), even when compared to the two other profiles (). It might first appear strange that keeping company was less frequently reported by co-habitant family carers. One explanation for might be that co-habitant family carers, unlike extra-household caregivers, do not see keeping company as a distinct form of caring, especially among older spousal caregivers (Torgé, Citation2014). For extra-household caregivers, physically transporting oneself to keep the care receiver company adds visibility and may be the reason why it was reported more frequently.

Compared to the helpful fellowman with which this profile shares many characteristics, persons in the care network were older, with 54% being older than 60 years. This also partly explains why fewer in the care network had full- or part time work, as 40% were retired (). As seen in and , the persons in this profile were likely to be an adult family member, with a majority (77%) providing care for someone older than 75 years, most often the caregiver’s mother or another relative such as parents-in-law, a sibling, or grandparents.

What sets the care network apart as a profile are their co-carers. Only one-tenth reported that there were no formal or informal co-carers. Looking closer at the data in , it can be concluded that caregiving responsibilities overlap between formal and informal caregivers in all profiles, but that this nearly always is the case when it comes to the care network profile. It was most common to report that the care receiver obtained help through public services, often municipal home help and home nursing, despite the relatively high volumes of hands-on informal care provision by the respondent. In this profile about half belong in a social network () and the majority also rate their health as very good or good.

Compared with the studies conducted in 2009 and 2014, there has been a decrease in the proportion of this profile, from around 20% of respondents to around 15% in the 2019 study (Jegermalm & Sundström, Citation2015).

The helpful fellowman

Almost a third of the informal caregivers in the survey consisted of the group that provided regular care tasks for someone outside their household, despite no special help needs on the part of the care receiver. We call this profile the helpful fellowman. Unlike the caregivers in the care network, they mostly perform activities at the ‘lighter end’ of caregiving.

shows that the helpful fellowman is the youngest of the three profiles, with 63% under 60 years old. They are likely to be working full- or part time. A shown in , a majority help someone who is older than them (60+ years), but a fifth help adults between 18 and 44 years old (). Commonly, the care receivers are extended relatives (27%) such as parents-in-law, a sibling, or grandparents. However, they are also likely to be caring for a neighbour or a friend, or a non-cohabiting child or mother.

A helpful fellowman performs the whole spectrum of care tasks, although in different volumes compared with the other caregiver profiles. One difference is that fewer in this profile give help with personal care (7%), which corresponds to the fact that the care receiver was not identified as requiring special help needs. More commonly, the helpful fellowman provides help with tasks such as keeping company (39%) or keeping an eye (33%). For the latter, they are just as likely to provide this help as persons in the care network. Many helpful fellowmen also regularly provide help with practical tasks such as housework (38%), gardening (37%) and taking the care receiver out of the house (32%) (). This may indicate that the care receivers, after all, experience difficulties in performing these tasks, although they ‘get by’ with a little help from helpful fellowmen. demonstrates, for example, that the care receivers, although rarely receive any help from formal care, received help from other co-carers (relatives, neighbours, or friends) to the same extent as care receivers helped by the care network. The helpful fellowman is like the care network in their involvement in informal social networks, where about half were involved, and a substantial majority (80%) also rate their health as very good or good.

The helpful fellowman is the only one of the three profiles that have increased in proportion over the surveys, from around 25% in earlier surveys, to almost a third of all respondents in the 2019 study (Jegermalm & Sundström, Citation2015). However, the character of the care tasks and the relationship to care receivers did not seem to change.

Discussion

It goes without saying that the three profiles presented here represents only one way to categorise ‘ideal types’ or general typologies of caregivers. In reality, it is possible for a caregiver to identify with more than one profile. For instance, a male informal caregiver can be a co-habitant family carer to his wife, part of a care network for the care of his adult son, and a helpful fellowman to a neighbour or friend. It is also possible for a caregiver to switch from one profile to another over time, as the needs of the care receiver change. In this respect, the survey strategy to ask informal carers to think of the person that they helped the most, was a necessary condition for the job of typologising carers and differentiating them conceptually. Not doing so would not only have made the structure of the survey more complicated but would also have made the analysis of different characteristics of caregiver groups quite blurred. However, because the respondents thought about the care receiver they helped the most, this arguably allowed them to self-identify with whatever caregiver situation that they felt most relevant for the moment. Thus, while we are aware that carers’ situations and their pathways into caregiving are more complicated in the real world, we also maintain that ‘ideal types’ have a function, as it allows us to see diversity within the group ‘informal carers’.

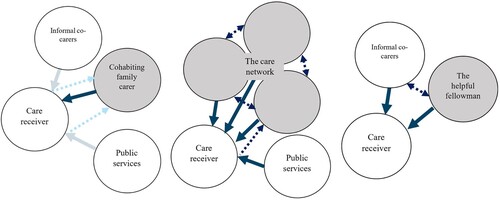

Our results show that there are clear differences between the three profiles of informal caregivers in terms of care activities performed at the ‘lighter’ and ‘heavier’ ends of caregiving as well as in the extent of reported co-carers. The three profiles’ panoramas of care are summarised visually in .

Figure 2. The care panoramas for the caregiver profiles ‘cohabiting family carer’, ‘the care network’ and ‘the helpful fellowman’.

An area where the knowledge of carer typologies can have implications, is in policy and practice regarding caregiver support. In our own context of Sweden, for example, legislation on carer support now identifies a broad definition of informal caregivers as clients eligible for social support. Yet, the public discourse on carer support still tends to focus on the most heavily burdened carers. Our results show that these carers only consist of one type of informal caregiver. The situation and needs of other carers have not been as visible. Neither it is clear to what extent these other groups obtain carer support and in what form this may take. In Sweden, as many as one out of five adults provide informal care, but the low uptake of carer support starkly contrasts with the wide ambitions to support informal caregivers (NBHW, Citation2012). Without knowing the situation of different carers, we also lack knowledge about how to help different types of carers in the best way.

The need for, and forms of direct and indirect carer support, will likely vary between caregiver profiles. Co-habitant family carers are heavily burdened caregivers. They are the most likely group for which direct carer support (such as self-help groups and counselling) is targeted, yet they lack indirect support from formal- and informal co-carers, so they remain alone in their caring responsibilities. Although cohabitant family caregivers have informal networks, they had little help. This shows an important distinction between social networks and carer networks (Phillips, Citation2007).

The situation of this profile suggests that more work is needed to encourage these carers to request formal and informal support, both for the care receiver and themselves. Primary carers often find it difficult to initiate requests for support (Dam et al., Citation2018). One way to make this easier to create integrated carer support systems that normalise the uptake of carer support. This requires raising awareness, making sure that pathways to support are as short as possible, and linking welfare information within health care systems where many have contacts, similar to an Australian model of integrated carer support (Department of Social Services, Citation2016). Co-habitant family carers may also need help in identifying and engaging their support networks for different kinds of practical assistance. Assistance from immediate- and extended family, as well as friends and neighbours, has been shown as a valuable source of support in studies involving different types of family caregivers (Chan et al., Citation2020). However, even though social networks may be willing to provide help, actual support is seldom provided due to barriers such as not having insight into the care situation, or not experiencing one’s need for help to be so urgent (Dam et al., Citation2018). Compounding a vulnerable situation is the tendency within families to be less engaged in a relative’s care, when there is a primary carer (Tolkacheva et al., Citation2010). To reduce such barriers, family- or group-based interventions can be considered in carer support provision, alongside traditional individual-based support (Zarit & Heid, Citation2015).

Caregivers in the care network fit the literature on ‘mixed care’ (i.e. care from different carers) (Camacho Ballesta & Minguela Recover, Citation2017). A comparative study (Camacho Ballesta & Minguela Recover, Citation2017) confirms that mixed care is more likely when the care receiver does not cohabit with a partner, and when one’s social networks are larger, which is supported by our results.

Caregivers in the care network have access to indirect support from informal and formal co-carers alike. Nevertheless, examples of direct carer support that may be relevant to this profile are involvement in decision-making and better facilitation of information between formal- and informal caregivers (Walker & Jane Dewar, Citation2001). Other forms of direct support may also be necessary. A recent study has shown that caregivers providing care from a distance have distinct emotional, financial, and social stressors, not least because of the need to be mobile, and because of competing time demands between caring for someone in another household, and one’s work, family, and friends (White et al., Citation2020). This study found that although distance carers were often part of a larger care network of paid and unpaid caregivers – something that our empirical data also show – their challenges nevertheless remained, and they also worried about the fragility of their support networks (White et al., Citation2020). Unfortunately, as Di Torella and Masselot (Citation2020) argue, carer entitlements of groups such as these are underdeveloped. Referring to carer rights in Europe, they point out that the right to flexible working arrangements is available for some carers (parents of young children) but not others (such as caregivers of other adults). Similarly, flexible leave provisions for working caregivers take for granted certain relationships (such as parenthood) yet leave out others (such as grandparents, stepparents or close friends that are heavily involved in caring). As this example shows, there is a gap in policy ambitions for carer support and the actual help that certain carers are entitled to by law.

The helpful fellowman is the least likely to ask for direct or indirect forms of support, due to the care receiver’s lack of special care needs. A traditional typology might even characterise the helpful fellowman’s activities as ‘service’. Nevertheless, our results point out that even though this profile provides the least number of hours of care per month, the difference is only marginal compared to the caregivers in the care network who might be seen as the more ‘typical’ extra-household caregivers. The helpful fellowman is likewise involved in all caregiving tasks. One way to interpret these results is that the helpful fellowman might be caring for someone whose care needs are not yet ascertained through formal needs assessment. Perhaps this profile even represents a transitional status prior to being a caregiver in the care network. In this case, they might be examples of emerging carers, that need to be identified early and proactively in health and social care.

Although generally invisible in mainstream care research, the helpful fellowman has been described in civil society research as substantial actors in the welfare society (Henriksen et al., Citation2008; Herd & Meyer, Citation2002). Our data supports this and shows that this profile is increasing in proportion. We mentioned that this may be an effect of the rationing of welfare services, that lead to persons with increasing – yet not yet extensive – difficulties to obtain various kinds of help from family and friends. Carer support that can be useful for this growing group of carers is access to information and advice regarding available services at for-profit or voluntary welfare- and service providers. Helpful fellowmen may be invisible to many welfare professionals, as care receivers do not use formal care. Thus, self-help resources online can be another example of how to reach this group, of which some may be in a transition to ‘heavier’ carer roles.

It should be mentioned that our survey data is cross-sectional, and we therefore cannot conclude anything about the substitution or complementarity of informal caring. What our analysis does show is an alternative picture of the different caring burdens and responsibilities of a broader group of informal caregivers, who in turn receive different extents of direct and indirect supports within their panoramas of care.

European reports emphasise the growing importance of informal caregivers, but also point out that few countries have developed support services aimed at informal carers (Spasova, Citation2018; Zigante, Citation2018). We maintain that in developing relevant carer support, it is important to acknowledge that caregivers are not a homogenous group. To fulfil national ambitions to support carers across the board, policy and practice need to consider the accessibility and usefulness of existing and planned supports, keeping in mind a diverse group of carers. By providing an empirically based categorisation of different profiles of carers, we hope to contribute towards this goal.

Geolocation information

57.7775933499562, 14.160541583968302.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data set associated with results and analyses presented is owned by the Ersta Sköndal Bräcke UC.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Magnus Jegermalm

Magnus Jegermalm is a Professor of Social Work at Jönköping University, Department of Social Work, and an affiliated Professor at Ersta Sköndal Bräcke University College, Stockholm. Since the late 1990s, Jegermalm has analysed trends of the civil society with a focus on older people’s involvement as volunteers and informal caregivers

Cristina Joy Torgé

Cristina Joy Torgé holds a PhD in Ageing and Later Life (Linköping University, 2014) and is currently working as a Senior lecturer (US: Assistant Professor) in Gerontology at the Institute of Gerontology, at Jönköping University. Her disciplinary background is in Philosophy and she holds master's degrees in the subjects Applied Ethics and Health and Society. Joy’s research interest is informal care by and for older people.

References

- AARP. (2020). Caregiving in the United States.

- Antonucci, T. C., Jackson, J. S., & Biggs, S. (2007). Intergenerational relations: Theory, research, and policy. Journal of Social Issues, 63(4), 679–693. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2007.00530.x

- Barbosa, A., Figueiredo, D., Sousa, L., & Demain, S. (2011). Coping with the caregiving role: Differences between primary and secondary caregivers of dependent elderly people. Aging & Mental Health, 15(4), 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.543660

- Bengtson, V., Lowenstein, A., Putney, N. M., & Gans, D. (2017). Global aging and challenges to families. In V. Bengtson & A. Lowenstein (Eds.), Global aging and its challenge to families. Routledge. 1–26.

- Bildtgård, T., & Öberg, P. (2017). Intimacy and ageing: New relationships in later life. Policy Press.

- Brimblecombe, N., Fernandez, J.-L., Knapp, M., Rehill, A., & Wittenberg, R. (2018). Review of the international evidence on support for unpaid carers. Journal of Long-Term Care, 25–40. https://doi.org/10.31389/jltc.3

- Camacho Ballesta, J. A., & Minguela Recover, M. A. (2017). Mixed care for elderly people in Spain and France: A comparative analysis. Revista de Cercetare si Interventie Sociala, 57, 89–103. http://www.rcis.ro/images/documente/rcis57_06.pdf

- Chan, C., Barnard, A., & Ng, Y. (2020). ‘Who are our support networks?’ A qualitative study of informal support for carers. Journal of Social Service Research, 47(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2020.1757012

- Cheng, S.-T., Lam, L. C., Kwok, T., Ng, N. S., & Fung, A. W. (2013). The social networks of Hong Kong Chinese family caregivers of Alzheimer’s disease: Correlates with positive gains and burden. The Gerontologist, 53(6), 998–1008. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns195

- Clark, H., Dyer, S., & Horwood, J. (1998). That bit of help: The high value of low level preventative services for older people. Policy Press.

- Dam, A. E., Boots, L. M., Van Boxtel, M. P., Verhey, F. R., & De Vugt, M. E. (2018). A mismatch between supply and demand of social support in dementia care: A qualitative study on the perspectives of spousal caregivers and their social network members. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(6), 881–892. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000898

- Deindl, C., & Brandt, M. (2017). Support networks of childless older people: Informal and formal support in Europe. Ageing and Society, 37(8), 1543. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16000416

- Department of Social Services. (2016). Delivering an integrated carer support service. A draft model for the delivery of carer support services. Australian Government.

- Di Torella, E. C., & Masselot, A. (2020). Caring responsibilities in European Law and policy: Who cares? Routledge.

- Eby, D. W., Molnar, L. J., Kostyniuk, L. P., St. Louis, R. M., & Zanier, N. (2017). Characteristics of informal caregivers who provide transportation assistance to older adults. PloS One, 12(9), e0184085. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184085

- Gatz, M., Bengtson, V. L., & Blum, M. J. (1990). Caregiving families. Handbook of the Psychology of Aging, 3, 404–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-101280-9.50030-9

- Gonçalves-Pereira, M., Zarit, S. H., Cardoso, A. M., Alves da Silva, J., Papoila, A. L., & Mateos, R. (2020). A comparison of primary and secondary caregivers of persons with dementia. Psychology and Aging, 35(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000380

- Henriksen, L. S., Koch-Nielsen, I., & Rosdahl, D. (2008). Formal and informal volunteering in a Nordic context: The case of Denmark. Journal of Civil Society, 4(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448680802559685

- Herd, P., & Meyer, M. H. (2002). Care work: Invisible civic engagement. Gender & Society, 16(5), 665–688. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124302236991

- Holbrook A. L., Krosnick, J. A., & Pfent, A. M. (2008). The Causes and Consequences of Response Rates in Surveys by the News Media and Government Contractor Survey Research Firms. In J. Lepkowski,, B. Harris-Kojetin, P. J., Lavrakas, C. Tucker, E. de Leeuw, M. Link, M. Brick, L. Japec & R. Sangster (Eds.), Telephone survey methodology. Wiley.

- Horowitz, A. (1985). Family caregiving to the frail elderly. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 5(1), 194–246. https://doi.org/10.1891/0198-8794.5.1.194

- Jegermalm, M., & Jeppsson Grassman, E. (2009). Caregiving and volunteering among older people in Sweden—prevalence and profiles. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 21(4), 352–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420903167066

- Jegermalm, M., & Sundström, G. (2015). Stereotypes about caregiving and lessons from the Swedish panorama of care. European Journal of Social Work, 18(2), 185–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2014.892476

- Jegermalm, M., & Sundström, G. (2017). Det svenska omsorgspanoramat: Givarnas perspektiv [The Swedish panorama of care: The caregivers perspective]. Tidsskrift for omsorgsforskning, 1. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.2387-5984-2017-01-04

- Jeppsson Grassman, E. (2001). Medmänniska och anhörig. En studie av informella hjälpinsatser. Sköndalinstitutet.

- Kemp, C. L., Ball, M. M., & Perkins, M. M. (2013). Convoys of care: Theorizing intersections of formal and informal care. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2012.10.002

- Kennedy, C., & Hartig, H. (2019). Response rates in telephone surveys have resumed their decline. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/02/27/response-rates-in-telephone-surveys-have-resumed-their-decline/

- Lethin, C., Hanson, E., Margioti, E., Chiatti, C., Gagliardi, C., Vaz de Carvalho, C., & Malmgren Fänge, A. (2019). Support needs and expectations of people living with dementia and their informal carers in everyday life: A European study. Social Sciences, 8(7), 203. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8070203

- Marino, V., Badana, A., & Haley, W. (2018). Stress, strain, health, and service use among primary and secondary caregivers. Innovation in Aging, 2(Suppl 1), 295. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igy023.1088

- McKie, L., Gregory, S., & Bowlby, S. (2002). Shadow times: The temporal and spatial frameworks and experiences of caring and working. Sociology, 36(4), 897–924. https://doi.org/10.1177/003803850203600406

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (1994). SoS-rapport 1994:22. Familjen som vårdgivare för äldre och handikappade.

- National Board of Health and Welfare. (2012). Anhöriga som ger omsorg till närstående. Omfattning och konsekvenser.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2013). OECD reviews of health care quality: Sweden 2013. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264204799-en

- Parker, G., & Lawton, D. (1990). Further analysis of the general household survey data on informal care. Report 1: A typology of caring. University of York, Social Policy Research Unit.

- Pearlin, L. I., & Aneshensel, C. S. (1994). Caregiving: The unexpected career. Social Justice Research, 7(4), 373–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02334863

- Phillips, J. (2007). Care. Polity Press.

- Plöthner, M., Schmidt, K., De Jong, L., Zeidler, J., & Damm, K. (2019). Needs and preferences of informal caregivers regarding outpatient care for the elderly: A systematic literature review. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1068-4

- SCB [Statistiskmyndigheten]. (2020). Antal hushåll och personer efter region, hushållstyp och antal barn. År 2011–2019. https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__BE__BE0101__BE0101S/HushallT05/

- Sivesind, K. H. (2017). The changing roles of for-profit and nonprofit welfare provision in Norway, Sweden, and Denmark. In K. Sivesind & J. Saglie (Eds.) Promoting active citizenship (pp. 33–74). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Spasova, S. B.-C. (2018). Challenges in long-term care in Europe. A study of national policies. European Commission.

- Sundström, G. (2019). Mer familj, mer omsorg: Svenska familjeband under senare år–särskilt 1985–2015. Familjen Först.

- Swedish Research Council (2017). Good Research Principles. Stockholm: Swedish Research Council.

- Swartz, K., & Collins, L. G. (2019). Caregiver care. American Family Physician, 99(11), 699–706.

- Szebehely, M. (2005). Anhörigas betalda och obetalda äldreomsorgsinsatser, i Forskarrapporter till Jämställdhetspolitiska utredningen. SOU 2005:66 (pp. 131–203). Fritzes offentliga publikationer.

- Takter, M. (2020). Anhörigperspektiv-en möjlighet till utveckling? Nationell kartläggning av kommunernas stöd till anhöriga 2019. Nationellt kompetenscentrum anhöriga.

- Tolkacheva, N., Broese van Groenou, M., & van Tilburg, T. (2010). Sibling influence on care given by children to older parents. Research on Aging, 32(6), 739–759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027510383532

- Torgé, C. J. (2014). Freedom and imperative: Mutual care between older spouses with physical disabilities. Journal of Family Nursing, 20(2), 204–225. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840714524058

- Twigg, J., & Atkin, K. (1994). Carers perceived: Policy and practice in informal care. McGraw-Hill Education.

- Van Houtven, C. H., & Norton, E. C. (2008). Informal care and medicare expenditures: Testing for heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Health Economics, 27(1), 134–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.03.002

- von Essen, J., Jegermalm, M., Kassman, A., Svedberg, L., Vamstad, J., & Lundåsen Wallman, S. (2020). Medborgerligt engagemang i Sverige 1992–2019 [Citizen engagement in Sweden 1992–2019]. Regeringskansliet.

- Wærness, K. (1996). Omsorgsrationalitet. Reflexioner över ett begrepps karriär. In R. Eliasson (Red.), Omsorgens skiftningar. Begreppet, vardagen, politiken, forskningen. Studentlitteratur. 203–220.

- Walker, E., & Jane Dewar, B. (2001). How do we facilitate carers’ involvement in decision making? Journal of Advanced Nursing, 34(3), 329–337. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01762.x

- White, C., Wray, J., & Whitfield, C. (2020). ‘A fifty mile round trip to change a lightbulb’: An exploratory study of carers’ experiences of providing help, care and support to families and friends from a distance. Health & Social Care in the Community, 28(5), 1632–1642. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12988

- Winqvist, M. (2014). Anhörigkonsulentens arbete och yrkesroll: Resultat från en enkätundersökning. Nationellt kompetenscentrum anhöriga.

- Wolff, J. L., & Kasper, J. D. (2006). Caregivers of frail elders: Updating a national profile. The Gerontologist, 46(3), 344–356. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.3.344

- Zarit, S. H., & Heid, A. R. (2015). Assessment and treatment of family caregivers. In P.A. Lichtenberg, B.T. Mast, B.D. Carpenter & J. Loebach Wetherell (Eds.), APA handbook of clinical geropsychology, Vol. 2: Assessment, treatment, and issues of later life (pp. 521–551). American Psychological Association.

- Zigante, V. (2018). Informal care in Europe. Exploring formalisation, availability and quality. European Commission.