ABSTRACT

Active labour market programmes (ALMPs) are a central aspect of labour market policies and are intended to combat the negative effects of long-term unemployment and increase the ability of individuals to obtain gainful employment and financial self-sufficiency. The purpose of this Swedish study is to explore the designs of six ALMPs and their sequential chains, through which participants are intended to transition from long-term unemployment to employment. Three of the ALMPs were delivered by the municipality and three by different NGOs. Programme stakeholders were interviewed using a semi-structured interview guide followed by clarifying questions. The results reveal that the basic components of the ALMPs vary in terms of activities, programme durations and education of the employees. Moreover, the goals of the sequential chains differ, and it was found that the municipal ALMPs define paid work on the open labour market, or financial independence, as the most important goal for participants. The goals for participants in NGO-based ALMPs, however, focused on enhancing wellbeing, skills, and self-confidence. The study adds to our understanding of differences and similarities of the basic components and sequential chains of municipality and NGO based ALMPs.

ABSTRAKT

Arbetsmarknadsprogram (ALMP) är en central del av arbetsmarknadspolitiken och de är avsedda att bekämpa de negativa effekterna av långtidsarbetslöshet och förbättra individernas förmåga att få förvärvsarbete och att bli ekonomiskt självförsörjande. Syftet med denna svenska studie är att utforska designen av sex olika program och jämföra deras grundläggande komponenter och utfallskedjor. Tre av arbetsmarknadsprogrammen har en kommunal huvudman och tre har olika frivilliga organisationer. Företrädare för programmen intervjuades med hjälp av en semistrukturerad intervjuguide som följdes av förtydligande och klargörande frågor. Resultaten visar att de grundläggande komponenterna i de olika programmen varierar när det gäller aktiviteter, programlängd och utbildning av de anställda. Dessutom skiljer sig målen för utfallskedjorna åt. De kommunala programmen hade betalt arbete på den öppna arbetsmarknaden eller ekonomiskt oberoende, som det viktigaste målet för deltagarna. Målen för deltagare i de programmen som gavs av de frivilliga organisationerna var att förbättra deras välbefinnande, färdigheter och självförtroende. Studien ökar förståelsen av skillnader och likheter mellan de grundläggande komponenterna och teoretiska grunderna för arbetsmarknadsprogram med olika huvudmän.

Introduction

Long-term unemployment is associated with a range of adverse consequences for individuals and their families, as well as the communities in which they live (Nichols et al., Citation2013). Research has shown that long-term unemployment has negative consequences for individuals’ financial situation and is an important indicator of many disparities in health and wellbeing (Lindo, Citation2011; Rege et al., Citation2011). Active labour market programmes (ALMPs) are a central element of activation policies and intend to combat the negative effects of long-term unemployment and increase the ability of individuals to obtain gainful employment and financial self-sufficiency. The ALMPs are a cornerstone for social policy and social work practice, as the programmes aim to reduce many of the social problems connected to long term unemployment (Hultqvist & Hollertz, Citation2021). Even though there is scarce evidence for the effectiveness of ALMPs, these programmes have become an important component of the modern welfare state, not only in Sweden but as a shared European development (Crépon & Van den Berg, Citation2016; Heidenreich & Rice, Citation2016; McKenzie, Citation2017; Rafass, Citation2017). On average, over one per cent of gross domestic product in Sweden has been directed towards the provision of ALMPs during the first decade of the twenty-first century, surpassed only by Denmark in the OECD area (Hur, Citation2018).

ALMPs are designed with the aim to support individuals to gain and/or maintain employment. Organisations implementing ALMPs may use a variety of strategies to achieve their goals (Brown & Koettl, Citation2015; Card et al., Citation2010; Kluve et al., Citation2017). ALMPs may, for example, consist of activities such as:

Skills training, referring to teaching job-specific technical skills but also to literacy and numeracy programmes as well as programmes that improve general work skills, behavioural skills, life skills or soft skills.

Employment services and sanctions refers to programmes delivering job counselling, assistance with job-seeking and/or mentoring services, which may be complemented by job placements and/or technical or financial assistance. In the case of individuals who are considered to put insufficient effort into their job search, sanctions are intended to restore an appropriate level of compliance.

Subsidised employment refers to programmes that include wage subsidies and labour-intensive public employment programmes. These programmes aim to reduce labour costs for employers and provide employment opportunities and infrastructure for social development and community projects. Subsidised employment may be provided in either the private or public sector.

Whereas the two first categories of programmes, the skills training and employment services connect to the traditions of individual and group oriented social work practice, subsidised employment programmes operate on a structural level. ALMPs can be designed to meet the needs of specific target groups with increased risk of long-term unemployment, such as newly arrived migrants, young persons, persons with a disability or older persons. However, programmes can also be provided to a broader range of participants by making them accessible to the general population of long-term unemployed individuals regardless of age, ethnicity, educational experience, or other specific criteria (Butschek & Walter, Citation2014; MacEachen et al., Citation2017; Tosun, Citation2017).

In Sweden, to be considered ‘long-term unemployed’ requires that an individual has been without employment for 6 months or more (SCB, Citation2018). Labour market policies are primarily a state responsibility, and the Public Employment Services (PES) is responsible for funding and developing strategies for ALMPs and deciding which programmes are made available and to whom. Registration with the PES provides access to ALMPs, after an assessment and referral by a PES caseworker. ALMPs may, however, be implemented by public or private actors, for-profit or not-for-profit (NGO) organisations. Municipalities, through their social services or equivalent organisational entities, are also important collaborating partners with PES and implement ALMPs for long-term unemployed individuals. In addition, municipalities deliver programmes for those who are supported by the social services and lack employment (Hollertz, Citation2016; Jacobsson et al., Citation2017). An argument for handing over the responsibility for the provision of ALMPs to private actors has been an ambition to achieve greater competition in the field. A political rationale behind increased marketisation is the belief that competition between a variety of service providers can increase the quality of services and results in more flexible organisations that are able meet the varying needs of the long-term unemployed. In Sweden, private providers are often described as being more innovative than public ones. However, private providers are also criticised for their cost-cutting practices, which are perceived as a threat to quality (Lundin, Citation2011). Currently, available research does not provide any evidence that private providers have been more successful than public providers, with respect to supporting individuals in moving from unemployment to employment (Norberg, Citation2018). In addition, meta-analytic research has investigated the impact of ALMPs for different populations and concluded that although some programmes provide benefit to participants, studies of ALMPs fail to describe the programmes’ underlying theories of change (Kluve et al., Citation2017). This means that it is unclear whether there is an experimental contrast in these studies or if the programmes evaluated are targeting similar change mechanisms through similar programme components; this complicates efforts to understand how ALMPs work to help vulnerable populations. There are also no available studies that describe and compare if and how underlying theories of change differ between public and private actors implementing ALMPs, which would increase our understanding of the important mechanisms to implement and measure in subsequent investigation of the intervention change processes.

Purpose and research questions

This study is a first attempt to explore the chain of events through which participants in ALMPs are intended to move in their transition from long-term unemployment to employment in programmes delivered by a municipality or NGOs in Sweden. Situated within a scientific realist philosophy (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997) the purpose of this study is to increase our understanding of:

the design of municipally provided and NGO-provided ALMPs and how they intend to move individuals from a state of unemployment to employment, and

the similarities and differences in the basic components and sequential chains between municipally provided and NGO-provided ALMPs.

The following questions are asked:

What are the basic programme design features (i.e. activities, target population, referral source, programme length and deliverer background) of the municipal and NGO-based ALMPs?

How do stakeholders responsible for the provision of municipally provided ALMPs describe what is defined as the sequential chain of events that participants move through to achieve the programme’s intended results?

How do stakeholders responsible for the provision of NGO-provided ALMPs describe what is defined as the sequential chain of events that participants move through to achieve the programme’s intended results?

What are the similarities and differences in the sequential chains between programmes implemented by the municipality and by NGOs?

Materials and methods

Programme recruitment, inclusion, and exclusion criteria

Active labour market programmes available to long-term unemployed individuals in a Swedish municipality, were recruited to the study via web-based announcements and personal contacts Three programmes from each of the two categories of service provider were selected to participate. The ALMPs were selected on a first-come-first-serve basis, assuming they fulfilled the following inclusion criteria:

The programme had a goal of increasing participants’ access to the labour market through work, work training or education.

The ALMP was offered to individuals who were considered long-term unemployed (i.e. outside of the labour market for at least six months).

The ALMP had participants in at least one of the following target groups: young persons (under age 25), individuals with a developmental and/or physical disability, migrants, and older individuals (55+) without post-secondary education.

The programme was operated by the municipality or an NGO.

Participants in the programme received economic support from either the municipal social services or the state insurance system.

The programme served a minimum of 40 participants per year.

The programme was seasonal and not on-going.

The programme was a time-limited project.

The programme had been in operation for less than 12 months.

Municipal employment offered to long term unemployed who were referred to the municipality for placements by PES (labelled M1)

Individual placement and support offered by a local social service to clients eligible for means tested social benefits (labelled M2)

Individual placement and support offered to citizens in psychiatric outpatient care without employment (labelled M3)

The following three ALMPs were delivered by non-governmental organisations:

Work training by an NGO offered to long term unemployed referred by a case worker in PES (labelled NGO1)

Work training by an NGO offered to long term unemployed referred by a case worker in PES (labelled NGO2)

Work training by an NGO offered to long term unemployed referred by a case worker in PES (labelled NGO3)

Semi-structured interviews

Programme stakeholders were interviewed based on a semi-structured interview guide. The guide was developed to investigate the four basic components present in a programme theory: inputs, objectives, outputs, and outcomes (Funnell & Rogers, Citation2011). The components were investigated through questions on the characteristics of participants, expected changes in participants and relationships between participants and employees. Questions also concerned the employees’ responsibility for implementing the programme, their educational background, and their work tasks. The interview guide also covered areas such as office spaces, documentation and documentation systems, available information technology, collaborative relationships with outside organisations and the local community, implementation processes, expected changes in participants, administration, and attitudes towards the programme.

The interviews were conducted by two of the authors with two to three employees from each ALMP who were either programme leaders or service personnel. During the interview, the interviewers made sure that the participants understood the questions by using clarifying information and that the participants were given the opportunity to discuss the answers together. In addition, clarifying follow-up questions were asked to make sure that the answers were correctly understood by the interviewers. The interviews were limited to two hours and all interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis of interviews, validation, and refinement

The analysis of the transcribed interviews was conducted in four stages. First, transcribed interviews were analysed via deductive content analysis inspired by Finfgeld-Connett (Citation2014) into the following categories: objectives of the ALMP, resources necessary to provide the ALMP, activities undertaken while participating in the ALMP, intended outcomes of the ALMP and external factors influencing the ALMP. Second, the reduced information was sorted into preliminary programme theory matrices (Funnell & Rogers, Citation2011). Third, the resulting programme theory matrices were presented to informants for validation and refinement. These meetings were limited to one hour each. The participants made minor changes to the logical order of outcomes and in some cases removed outcomes they felt were irrelevant to their programme. After the changes were made, all programme representatives agreed on the construction of the programme theory matrices. Finally, the information received from the participants concerning target groups, referrals, basic components of the programme, time that a participant can join the programme and preferred employee background was analysed to compare the sequential chains of the ALMPs.

Ethics

Participation in the study was voluntary, and information about the study was provided to all participating organisations in face-to-face meetings and in writing before and during the process. The study used a collaborative approach between the representatives for the programmes and the researchers, following the guidelines of the Swedish Research Council (Citation2017). The Swedish Ethical Review Authority approved the study [will add the reference number].

Results

Design features of the included ALMPs

According to research (Crépon & Van den Berg, Citation2016), there are several types of ALMPs with the purpose of supporting return to employment. Four different main categories of ALMPs are described (Kluve et al., Citation2017; Rafass, Citation2017):

Training – classroom, on the job and work experience

Private sector incentive schemes – wage subsidies to private firms and start-up grants

Direct employment programmes in the public sector, usually work-for-benefit schemes

Services and sanctions to increase job search efficiency

Among the ALMPs in this study, a job and work experience are essential parts of the programmes (the first category). Wage subsidies and direct employment programmes in the public sector (2 and 3) are found in several of the programmes. None of the programmes directly include job search efficiency or related sanctions services (4).

The basic design features of the ALMPs are presented in .

Table 1 The basic design features of the ALMPs.

Both NGO and municipal ALMPs offer services to a broad and diverse population, including individuals experiencing long-term unemployment within the age range of 18–64. The exceptions are M1, which only includes persons aged 25–64; NGO2, which only includes women; and M3, which only includes persons with a psychiatric diagnosis. The NGO programmes have a narrower referral stream as all clients are referred from the PES, while the municipal programmes are accessible through various channels such as the PES, municipal social services, and self-referral. The NGO ALMPs are shorter in duration than the municipally run programmes.

The NGOs provide work training for their participants within their own organisations. This differs from the municipal ALMPs who collaborate with private and public employers outside their organisations to provide work training to participants.

The employees in the municipal ALMPs have university educations, including social workers, occupational therapists or pedagogues who serve as work specialists, work coaches or coordinators to support participants. The necessary resources for the NGOs include access to professionals with university educations, however most of the employees are individuals with experience of long-term unemployment who have participated in ALMPs themselves. This was especially noticeable in NGO2 and NGO3. In these NGOs, some of the employees also had wage subsidies attached to their employment.

Municipal ALMPs’ sequential chains

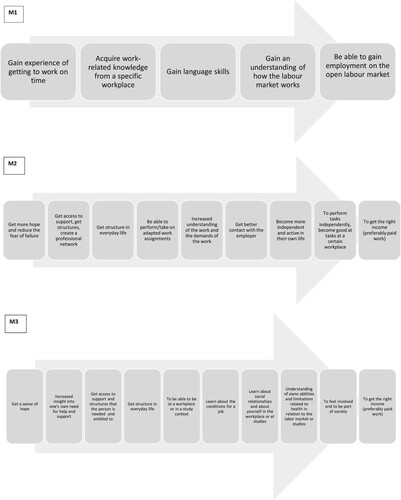

Each of the municipal ALMPs’ sequential chains are presented in .

In the municipal ALMPs, the objectives of the programmes focused on labour market participation. The intended outcomes were for participants to successfully gain employment on the regular labour market, with or without wage subsidies attached to the employment. The respondents of M2 and M3 also identified changes such as increased confidence, independence and feelings of hope, as important outcomes of the programmes they represented. Descriptions of the activities programme participants engage in while participating in the ALMPs studied focused on increasing employment-related knowledge, skills, abilities, and experiences. This included, for example, knowledge of specific work-related tasks and increased experience and ability to engage in adapted tasks. It also included focus on time management skills and punctuality, as well as experience with daily routines. Passive language skills development was also a component identified by respondents representing the municipal ALMPs.

NGO ALMPs’ sequential chains

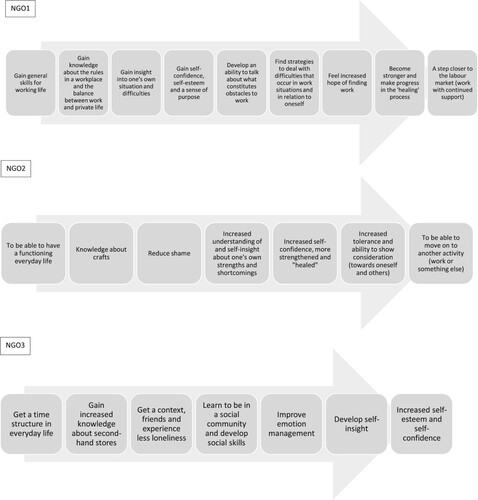

The NGO-provided ALMPs’ sequential chains are shown in .

In the NGO-based ALMPs, the goals were for participants to enter the labour market and gain employment with support or to proceed into another ALMP once the programme was completed. The intended outcome of the ALMPs was personal development for the participants. This included higher self-confidence, development of self-insight and better emotional management. Another indented outcome was for participants to gain and develop social skills, including learning to be part of a social context in the workplace, finding new friends, having a social context outside the workplace, and increasing tolerance for other participants and employees. The participants received support from employees within the programme to achieve the stated outcomes.

The activities that participants undertake in the NGOs focused on learning and developing specific competences that are relevant to the daily activities performed within the programme and to learn to manage tasks linked to the work performed within the NGOs. In addition to these specific work-related skills, the development of more general skills related to working life, such as punctuality and having a structure in everyday life, was described as a desired outcome. According to the informants of NGO1, the activities also had a more general labour market orientation aimed at developing general skills desired by the labour market, such as knowledge of rules in the workplace and identifying barriers to gaining work, in order to take a step closer to entering the labour market.

Similarities and differences in sequential chains between municipal- and NGO-provided ALMPs

The municipal ALMPs focused on the labour market and employment in their sequential chains to a greater extent than those provided by the NGOs. Among the NGO-based ALMPs, it was only the informants of NGO1 that focused on employment in the sequential chains. The differing goals of the ALMPs are also revealed in the intended outcomes for the participants upon completing the programmes. The programmes delivered by the municipality focus on improving participants’ skills to improve their chances of entering the labour market or helping them receive the financial support to which they are entitled. As shown in the sequential chain, the aim for participants of M2 and M3 is to receive the appropriate financial support or paid work. In the sequential chain of M1, it is also shown that the goal for participants is to have paid work upon leaving the programme. The informants of M1 also describe that the goal for participants is to develop work-related competence.

Personal development was described in the sequential chains of all the NGO-provided AMLPs and in two of those provided by the municipality. The NGO programmes encourage participants to identify their own barriers to work and find strategies for dealing with them to increase their chances of finding employment. The municipal programmes, especially M2 and M3, do not focus on barriers but rather encourage participants to identify their strengths and find strategies to implement them.

The importance of a well-functioning social context, developing social skills and making friends was described in the sequential chains of NGO2 and 3. The development of competence, knowledge and skills was described in all the sequential chains except NGO1. In the NGO-based ALMPs, participants are generally described as weak, fragile, vulnerable and in need of a supportive and protective structure. The informants of the NGOs describe the work tasks that the participants perform as being unimportant in themselves and that they serve as a tool to develop more general work-related skills and competences, such as being part of a group and taking instruction. They describe the development of skills as a tool that will help participants to overcome the personal challenges that constitute barriers to finding employment.

In the municipal ALMPs, the goal is for participants to develop skills and competences in relation to site-specific work tasks. In essence, this means learning how to perform a certain task within a certain work setting, is considered as central for chances for future employment. To some extent, M3 differs from the other municipal ALMPs as it aims to increase participants’ awareness about how they function at the workplace. The municipal informants describe a more technical approach to the participants’ learning of specific skills than those representing the NGOs; in the NGO programmes the social aspects of the learning process is given more weight.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to increase our understanding of the design of municipally provided and NGO-provided ALMPs and how they are intended to move individuals from a state of unemployment to employment, and to identify the similarities and differences in their basic components and sequential chains.

The basic programme design features

The target group – inclusion and exclusion criteria

The ALMPs in this study, except M1, invite all persons aged between 18 and 64 to participate and can therefore be defined as age neutral. It is reported (Crépon & Van den Berg, Citation2016) that ALMPs are often open to a broad eligible population and a particularly important heterogeneous dimension is that of age. However, it is reported (Heckman et al., Citation1999; Nordlund, Citation2011) that ALMPs have more positive effects for older participants than younger ones, which is explained by the fact that older participants have labour market experience and access to more human capital. In response to the earlier findings, it is a point of discussion why the programmes are designed in this broad way and if it is feasible to cater to all needs that can be included in the different age groups given the range of different experiences and life situations. As shown by Nordlund (Citation2011), for example, young unemployed individuals who have little or no experience in the labour market have different life experiences and needs than older unemployed persons.

One of the ALMPs serves females only, a decision motivated by a belief that women are vulnerable and need to be protected and sheltered from men while participating in labour market programs. Findings from earlier research indicate that creating ‘protected rooms’ is a strategy to ‘foster femininity’ and cater to the particular needs, actual or constructed, of women. This is a rare practice in the labour market but is used in social work practice, for example in addiction treatment (Campbell & Herzberg, Citation2017). Research on the outcomes of ALMPs for men compared to women deliver mixed results (see Crépon & Van den Berg, Citation2016). Card et al. (Citation2010) report that the ALMPs do not appear to have differential effects on men versus women. However, other studies have reported ALMPs to be more effective for men than women, especially for economically disadvantaged males (Card et al., Citation2018; Friedlander et al., Citation1997). There are also findings that show that there is a larger impact of ALMPs for female participants in ALMPs (Card et al., Citation2018). Blumenberg (Citation2002) argues that ALMPs should address the barriers facing low-income women specifically and that ALMPs need to account for the specific employment related barriers that women face. Further, there is a need for coordinating the service provision and to develop ALMPs to meet the needs of different groups to enter the labour market (Blumenberg, Citation2002). The recognition of difficulties to reach employment due to a range of different barriers have implications for social work and social work profession which needs to be studied further. This includes for example barriers faces by persons with psychiatric diagnosis. In the study the inclusion criteria of one of the programmes requires that participants have a psychiatric diagnosis. The other programmes recognise that a participant might have a disability, diagnosed or undiagnosed, that could be a barrier to entering the labour market. In a review (MacEachen et al., Citation2017) it is reported that even if there is an increase of studies about mental health issues, there is a need to further study the barriers and needs for people with disability to enter the labour market.

Duration of the programmes

The durations of the municipal and NGO-based ALMPs differ. Within the NGO-based programmes, a participant can attend the programme for 3–6 months, with the possibility of extension. The municipal programmes offer a much longer programme, at least 12 months or until the participant is financially self-sufficient. In all the NGO programmes, short referrals were described as a problem for reaching the goals of the intervention.

Card et al. (Citation2018) found that programmes with short durations (4 months or less) have significantly fewer positive outcomes than those with a longer duration. In addition, the duration of the programme and subsequent impact on participants vary according to the type of programme, with larger average gains for programmes that emphasise human capital accumulation. It has been argued (see Kluve, Citation2016) that the number of training components may not be the key determining factor for outcome of a programme but instead the length of the programme.

The referral process and the background of the employees

Five out of the six programmes are dependent on referrals from case workers in local public employment services or municipal social services. This means that most of the participants are subjects of different ongoing actions and arrangements and participating in a programme could be a requirement of the referring authority. The effect of this needs to be further studied as the assignment to ALMPs relies primarily on the discretion and decisions of the professionals who make the referrals (Dengler, Citation2019). It is also a matter of the background and professional knowledge of those who are employed in the ALMPs and their decisions about programme assignments. Accordingly, professional background, such as education and work experience, is of interest. In the study, most of the ALMPs support the idea that employees should have a university degree in a relevant field. However, in NGO2 and 3, the employees’ own experiences of attending ALMPs or being unemployed themselves are seen as a beneficial factor and some also have wage subsidies attached to their employment. This presents a dual situation in which some of the employees are subjects to active labour market policies themselves. Whether this is beneficial to the participants needs to be studied further.

Activities

The ALMPs provided by the NGOs include work tasks and daily activities within their organisations. This means that employees and participants meet during the day and can share, reflect, and maintain an ongoing discussion about the work. This also means that the work training is taking place on the premises of the NGOs. The employees of the NGOs are in control of the workspace and the tasks that are performed by the participants. Even if the NGO-based programmes offered work through which the participants were exposed to contact with other people, it can be understood that the participants of the NGOs are sheltered and protected, which is in sharp contrast to the municipal programmes. The participants of the municipal ALMPs are in regular workplaces and the employees are not in control of the daily activities of the participants. These participants rely on the employees of the workplace and are expected to be part of the workplace. The role of the employees of the ALMP is to support the workplace and participant on a consultative basis. This means that the participants in municipal programmes do not have the daily support of employees at the ALMPs and experiences and reflections have to be shared at scheduled meetings. These differences can be understood as being congruent with Bonoli (Citation2010) and the distinction between ‘life first’ and ‘work first’ programmes for unemployed individuals. In a sheltered environment with continuous contact and support from ALMP employees, there is a possibility of interaction and reflection between employees and participants, which may support their human capital. Aspects such as fears, everyday struggles and individual life situation are placed at the forefront of the programme, when employees and participants can integrate on an everyday basis. The programme theory of the NGO-based ALMPs can be understood to support the human capital of the participants, with the ability to take the daily experiences of the participant into account, which is more difficult in municipal programmes. It is reported (Card et al., Citation2018) that human capital programmes have small, or in some cases even negative, short-term impacts, but that they have larger impacts two to three years after the completion of the programme, which indicates the need for longitudinal follow-up studies.

The sequential chains of the ALMPs

The sequential chains – similarities and differences

Most of the ALMPs’ sequential chains focus on participants’ capacities to manage their time and the structure of their everyday lives. This could be interpreted as meaning the participants lack structure, including time management skills, and therefore that they need support with this. However, there is little scientific evidence that unemployed individuals have more difficulty than others structuring their days. On the contrary, research indicates that structure is not a problem as such for those who are unemployed, rather the problem is their lack of income. Knabe et al. (Citation2010) report that those in long-term unemployment experience their everyday lives as being equally satisfying as those who are employed. This is explained by them having more available time for non-work-related activities that are more satisfying.

There is a difference between the way the informants describe participants’ abilities and needs. In the NGO-based ALMPs, the participants are generally described as weak, fragile, vulnerable and in need of a supportive and protective structure. In the municipal ALMPs, the participants are instead described as competent and able with the need to be supported in finding their way into the labour market. The statements of the abilities and needs of the participants might reflect an awareness of the needs of the participants, especially in the NGO-based ALMPs in which the employees work more closely with the participants than in the municipal ALMPs. The NGO-based ALMPs are based on the premise that the relations and context shall be supportive of the participants. This is in accordance with research by McEnhill et al. (Citation2016), who reported that peer support can lead to several positive education and/or employment outcomes, such as joining the labour market and/or improving self-esteem or confidence. However, as the authors concluded, peer support can be designed in different ways and implemented with various degrees of success.

The inclusion of self-esteem or confidence in the sequential chains of the NGOs can be understood as a therapeutic chain; they aim to support the participants to proceed from feelings of hopelessness to those of hope and meaning and support their self-esteem. It can be discussed if the peer-support design can help the transition into employment in a similar way as found by Nielsen Arendt et al. (Citation2020). They measured progression towards employment in terms of developing skills and found that the self-reported health of those who attended ALMPs was the main predictor of employment. This indicates that the transition process into employment needs to be studied further and that NGO-based ALMPs might serve as a progression or step towards a job compared with municipal ALMPs that define paid work on the open labour market or financial independence as the most important goals. NGOs do not consider skills learned as an outcome per se, rather that the skills learned and the content of ALMPs should increase wellbeing, skills self-confidence, and insight into the specific challenges that participants might have.

Another difference found in the sequential chains is the special attention paid to language training, as described by the informants of M1. This can be interpreted as the ALMP identifying a lack of sufficient knowledge of the Swedish language as a barrier to employment. It can also be interpreted as this programme recognising that participants have different language backgrounds and need language training. This might imply that the general inclusion of participants from different migrant backgrounds is not recognised in other ALMPs. The absence of this in the sequential chains may imply that the programmes are not adapted to the target group and might fail to support the participants to reach the goals of the programme.

Concluding analysis and practical implications

The findings reveal that there are similarities and differences in the basic components and sequential chains of NGO-based and municipal ALMPs. The distinction between ‘life first’ and ‘work first’ (Bonoli, Citation2010) could be used to further analyse the designs and programme theory. The ‘life first’ perspective could be illustrated by the informants of NGO-based ALMPs that present participants as a vulnerable group that requires a sheltered environment including peer support. The sequential chains focus on the personal development of the participants, which can be understood as the programmes supporting foremost the human and social capital of their participants. The ‘work first’ approach is identified in the municipality ALMPs, in which the participants are presented as competent and able. In line with this, the participants join workplaces and are expected to participate in work, the motivation being that it is the most effective way into the labour market. The sequential chains reflect that the aims for participants are to achieve paid work on the open labour market or financial independence. This can be understood as the municipal ALMPs supporting the economic capital of their participants.

Together with previous research, this study adds to our understanding of the variations in programme theory and designs of municipality and NGO -based ALMPs. It also reveals the need for further research about the theoretical foundations of ALMPs and the differences in the programme theories of the ALMPs disclose a complex set of conditions and circumstances that needs to be further studied and to be developed in social work practice as well as employment services. Therefore, programme theory awareness could support stakeholders to analyse if the content of a programme is consistent with its objectives and research and then develop ALMPs with achievable goals for participants.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for the time set aside and the information provided by the respondents. Many thanks to assistant professor Tina Olson for valuable comments on the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mikaela Starke

Starke is a professor in social work with a special interest in disability and interventions and implementations in social work.

Katarina Hollertz

Hollertz is an assistant professor in social work. Her main research interests are in the fields of labour market policies, activation, and social work practice.

References

- Blumenberg, E. (2002). On the way to work: Welfare participants and barriers to employment. Economic Development Quarterly, 16(4), 314–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124202237196

- Bonoli, G. (2010). The political economy of active labor-market policy. Politics & Society, 38(4), 435–457. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329210381235

- Brown, A. J. G., & Koettl, J. (2015). Active labor market programs – Employment gain or fiscal drain? IZA Journal of Labor Economics, 4(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40172-015-0025-5

- Butschek, S., & Walter, T. (2014). What active labour market programmes work for immigrants in Europe? A meta-analysis of the evaluation literature. IZA Journal of Migration, 3(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40176-014-0023-6

- Campbell, N. D., & Herzberg, D. (2017). Gender and critical drug studies: An introduction and an invitation. Contemporary Drug Problems, 44(4), 251–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091450917738075

- Card, D., Kluve, J., & Weber, A. (2010). Active labour market policy evaluations: A meta-analysis. The Economic Journal, 120(548), F452–F477. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02387.x

- Card David, Kluve Jochen, Weber Andrea (2018). What works? A meta-analysis of recent active labor market program evaluations. Journal of the European Economic Association, 16(3), 894–931. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvx028

- Crépon, B., & Van den Berg, G. J. (2016). Active labor market policies. Annual Review of Economics, 8(1), 521–546. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-080614-115738

- Dengler, K. (2019). Effectiveness of active labour market programmes on the job quality of welfare recipients in Germany. Journal of Social Policy, 48(4), 807–838. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279419000114

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2014). Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Qualitative Research, 14(3), 341–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794113481790

- Friedlander, D., Greenberg, D. H., & Robins, P. K. (1997). Evaluating government training programs for the economically disadvantaged. Journal of Economic Literature, 35(4), 1809–1855.

- Funnell, S., & Rogers, P. J. (2011). Purposeful program theory, Effective use of the theories of change and logic models. Jossey Bass/John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Heckman, J. J., Lalonde, R. J., & Smith, J. A. (1999). The economics and econometrics of active labour market programs. The Handbook of Labor Economics, 3(part A), 1865–2097. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1573-4463(99)03012-6

- Heidenreich, M., & Rice, D. (2016). Integrating social and employment policies in Europe: Active inclusion and challenges for local welfare governance. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hollertz, K. (2016). Integrated and individualized services. In M. Heidenreich, & D. Rice (Eds.), Integrating social and employment policies in Europe: Active inclusion and challenges for local Welfare governance (pp. 51–71). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hultqvist, S., & Hollertz, K. (2021). Individual need and societal claims: Challenging the understanding of universalism versus selectivism in social policy. Social Policy & Administration, 55(5), 940–953. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12680

- Hur, H. (2018). Government expenditure on labour market policies in OECD countries: Responding to the economic crisis. Policy Studies, 40(6), 585–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2018.1533113

- Jacobsson, K., Hollertz, K., & Garsten, C. (2017). Local worlds of activation: The diverse pathways of three Swedish municipalities. Nordic Social Work Research, 7(2), 86–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2016.1277255

- Kluve, J. (2016). A Review of the effectiveness of active labour market programmes with a focus on Latin America and the Caribbean. Research Department Working Papers, No 9, International Labour Office, Geneva, March.

- Kluve, J., Puerto, S., Robalino, D., Romero, J. M., Rother, F., Stöterau, J., Weidenkaff, F., & Witte, M. (2017). Interventions to improve the labour market outcomes of youth: A systematic review of training, entrepreneurship promotion, employment services and subsidized employment interventions. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–288. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2017.12

- Knabe, A., Rätzel, S., Schöb, R., & Weimann, J. (2010). Dissatisfied with life but having a good day: Time-use and well-being of the unemployed. The Economic Journal, 120(547), 867–889. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02347.x

- Lindo, J. M. (2011). Parental Job Loss and infant health. Journal of Health Economics, 30(5), 869–879. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.06.008

- Lundin, M. (2011). Arbetsmarknadspolitik-om privata komplement till arbetsförmedlingen. In L. Hartmann (Ed.), Konkurrensens konsekvenser. Vad händer med svensk välfärd (pp. 146–180). SNS förlag.

- MacEachen, E., Du, B., Bartel, E., Ekberg, K., Tompa, E., Kosny, A., Petricone, I., & Stapleton, J. (2017). Scoping review of work disability policies and programs. International Journal of Disability Management, 12, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1017/idm.2017.1

- McEnhill, L., Steadman, K., & Bajorek, Z. (2016). Peer support for employment: A review of the evidence. The Work Foundation, Lancaster University. Retrieved 16/09/21 from https://www.base-uk.org/knowledge/peer-support-employment-review-evidence.

- McKenzie, D. (2017). How effective are active labor market policies in developing countries? A critical review of recent evidence. The World Bank Research Observer, 32(2), 127–154. https://doi.org/10.1093/wbro/lkx001

- Nichols, A., Mitchell, J., & Lindner, S. (2013). Consequences of Long-Term Unemployment. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/consequences-long-term-unemployment.

- Nielsen Arendt, J., Lindegaard Andersen, H., & Saaby, M. (2020). The relationship between active labor market programs and employability of the long-term unemployed. Labour (committee. on Canadian Labour History), 34(2), 154–175. https://doi.org/10.1111/labr.12172

- Norberg, H. (2018). Hur kan externa aktörer bidra till bättre arbetsförmedlingstjänster? – eller “it’s all about execution”. In A. Bergström, & L. Calmfors (Eds.), Framtidens arbetsförmedling (pp. 299–341). Fores.

- Nordlund, M. (2011). Who are the lucky ones? Heterogeneity in active labour market policy outcomes. International Journal of Social Welfare, 20, 144–155. https://doi-org.ezproxy.ub.gu.se/10 .1111/j.1468-2397.2010.00740.x

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). An introduction to scientific realist evaluation. In E. Chelimsky, & W. R. Shadish (Eds.), Evaluation for the 21st century: A handbook (pp. 405–418). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483348896.n29.

- Rafass, T. (2017). Demanding activation. Journal of Social Policy, 46(2), 349–365. https://doi.org/10.1017/S004727941600057X

- Rege, M., Telle, K., & Votruba, M. (2011). Parental job loss and children’s school performance. The Review of Economic Studies, 78(4), 1462–1489. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdr002

- SCB. (2018). Arbetslöshetstid i Arbetskraftsundersökningarna (AKU) och tid utan arbete på Arbetsförmedlingen (Af). Rapport, Statistiska centralbyrån. Retrieved 05/09/2021 from, https://www.scb.se/contentassets/46a4a9bddec2413799c697d0cc0dbb5a/am0401_2018a01_br_am76br1806.pdf.

- Swedish Research Council. (2017). Good Research Practice. Retrieved 14/09/2021 from, https://www.vr.se/english/analysis/reports/our-reports/2017-08-31-good-research-practice.html.

- Tosun, J. (2017). Promoting youth employment through multi-organizational governance. Public Money & Management, 37(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1249230