ABSTRACT

This article is based on the premise that the Covid-19 pandemic represents an unprecedented experience in contemporary social work education, and that it presents unique challenges to all involved in practice teaching and require a comprehensive understanding of what has been termed as ‘New Normal’. The results of a survey conducted in Slovenia are presented regarding the course of practice teaching before and during the Covid-19 epidemic, the provision of mentoring support in normal and emergency situations, and the challenges of mentoring in times of changed circumstances. The findings indicated that the Covid-19 pandemic impacted the practice teaching of social work students in terms of both the content and nature of mentoring, and that the students were less satisfied with their practice teaching than they were in the pre-Covid-19 era. Nonetheless, one promising finding was that mentors supported students in an adaptive manner; therefore, the students were consequently able to acquire the necessary practical skills.

POVZETEK

Članek temelji na predpostavki, da pandemija Covid-19 predstavlja izkušnjo brez primere v sodobnem izobraževanju na področju socialnega dela in edinstven izziv za vse, ki so vključeni v praktično usposabljanje, ter zahteva celovito razumevanje tega, kar je bilo poimenovano kot ‘nova normalnost’. Predstavljeni so rezultati raziskave, izvedene v Sloveniji, o poteku praktičnega usposabljanja pred epidemijo Covid-19 in med njo, o zagotavljanju mentorske podpore v običajnih in izrednih razmerah ter o izzivih mentorstva v času spremenjenih okoliščin. Ugotovitve kažejo, da je pandemija Covid-19 vplivala na praktično usposabljanje študentk in študentov socialnega dela tako z vidika vsebine kot narave mentorstva in da so bili študentke in študentje manj zadovoljni s praktičnim usposabljanjem kot v obdobju pred pandemijo Covid-19. Kljub temu pa je vzpodbudna ugotovitev, da so mentorice in mentorji študentke in študente podpirali na prilagodljiv način, zato so študentke in študenti posledično lahko pridobili potrebne praktične veščine.

KLJUČNE BESEDE:

Introduction

Social work, as defined by the International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW, Citation2014), is an academic discipline and practice-based profession, and practice teaching is recognised as a formative component in preparing social work students for professional practice (Bogo, Citation2014; Wayne et al., Citation2010). Different terms are used to refer to practice learning of students, such as practicum, internship, field practice, practice placement, field practicum, practice teaching. In this article the term practice teaching is employed as used by Doel and Shardlow (Citation2016). A primary purpose of practice teaching is to provide students with the opportunity to apply and synthesise the knowledge and skills acquired in the classroom in a safe social work practice environment where they have support of both the agency mentor and faculty supervisor (Sarbu & Unwin, Citation2021; Walsh et al., Citation2019). Social work literature generally refers to mentors as supervisors, practice teachers, field instructors, or field supervisors (see Martin et al., Citation2020). The terms mentor and mentoring will be used in this article when referring to agency mentors, and the terms faculty supervisor and supervising when referring to the process of cooperation between the social work teacher and students.

In 2020, however, the Covid-19 pandemic caused sudden changes both at the societal level and in people’s daily lives. Practice teaching in social work faced great challenges, including the reshaping of school education by the measures taken to contain the spread of the virus. Schools and universities closed their doors, and online learning became the new norm (Azman et al., Citation2020), with social work education no exception. The findings of many studies (Morley & Clarke, Citation2020; Szczygiel & Emery-Fertitta, Citation2021; Walter-McCabe, Citation2020) have demonstrated that Covid-19 has created a less than ideal environment for social work education and practice. Universities had to be fast and innovative in rethinking and redesigning both classroom and practice teaching. Organisations that typically provide practice teaching for students also had to develop new forms of service delivery to meet the demands of governmental measures and new challenges (Morley & Clarke, Citation2020; Walter-McCabe, Citation2020).

New terms for practice teaching were coined (e.g. ‘e-placement’, Zuchowski et al., Citation2021), as the virtual spaces replaced practice placements what was a new situation for social work education. Additional challenges were related to the findings of some previous research (e.g. Carrilio, Citation2008) that a non-negligible proportion of social workers were uncomfortable using information and communication technology (hereafter ICT).

Practice teaching was burdened by changing routines, curricula, and work environments, as well as increased stress among all involved (students, mentors, supervisors and service users). Mentoring support for students by experienced social workers who monitor student progress and skill acquisition (Bogo, Citation2014; McSweeney & Williams, Citation2018; Nordstrand, Citation2017) became even more important during the pandemic. Above all, a major challenge for mentors was finding ways to support students in these uncertain situations (Szczygiel & Emery-Fertitta, Citation2021).

In Slovenia, soon after the epidemic was declared (summer 2020), the data were collected on how students from the Faculty of Social Work (hereafter FSW) and mentors experienced practice teaching during the first wave. Prior to this, the data were occasionally collected for the purpose of evaluation. The last most complex evaluation was conducted in 2015 and was based on data collected from mentors and students for the 2014/2015 academic year. The main aim of this article is to examine how mentors’ support of students has adapted to the new conditions and how practice teaching during the epidemic has differed from the situation before the virus, using Slovenia as a case. The importance of mentoring students and implementing social work practice teaching during the Covid-19 pandemic is presented first, followed by research findings on student and mentor views of practice teaching and mentor support during and outside of the Covid-19 pandemic. We use the term epidemic for the situation in Slovenia, where it was first declared in March 2020. The term pandemic is used when referring to a global situation.

The importance of mentor support in practice teaching

Practice teaching is often rated by social work students as the most important, productive, and memorable component of their studies (Bălăuţă & Vlaicu, Citation2017; Lefevre, Citation2005). Although there are different models of practice teaching in social work programmes in Europe (and around the world), the curriculum is often organised through practice-based courses (Urbanc et al., Citation2016), and many social work programmes take the opportunity to increase the number of hours allocated to practice teaching (Doel & Shardlow, Citation2016). Practice teaching allows students to develop, enrich and integrate theoretical and practical knowledge and to get a sense of a professional identity and self-image as a social worker (Bogo, Citation2014; Frost et al., Citation2013; Satka et al., Citation2016). Research has shown that the relationship between mentor and student can influence student learning and satisfaction with practice (Raskin, Citation1989). Mentoring is critical not only to the development of the student’s skills, but also to the student’s identification with the responsibilities, values and ethics of the social work profession, their socialisation in the agency and their understanding of the agency in the broader community (Bogo, Citation2014; Castillo et al., Citation2021; Hrnčić et al., Citation2020). Mentoring is also an opportunity to provide emotional support to students when needed and to develop resilience in coping with issues students may face later in their work (Sepulveda-Escobar & Morrison, Citation2020).

Mentoring is a process that benefits both the student and the mentor and research (Hay & Brown, Citation2015) show that mentoring ensures learning, development and growth for both. Mentors report that mentoring brings them personal satisfaction, greater visibility of the organisation, a better atmosphere in the organisation and encouragement to all employees from the youthful energy and motivation of students, while strengthening their own knowledge and skills, relieving them of minor tasks, allowing them to rethink their work responsibilities and, at the same time, bringing them advancement that is often associated with higher pay (Hay & Brown, Citation2015). The success of mentoring is related to the personal characteristics of each mentor and their skills in supporting students. Research (Bogo, Citation2014; Knight, Citation2001) shows the importance of students having mentors who are supportive in practice, who are actively involved in the learning process, who provide constructive feedback on student behaviour, who encourage student autonomy and self-criticism, and most importantly, who support the students in testing and applying theory to practice. Based on the premise that practice teaching and mentoring are some of the key factors in preparing students for social work practice, the adaptation of social work practice education in Covid-19 required special attention (Hatton et al., Citation2021).

In the FSW, practice teaching has a long tradition and has been an integral part of the curricula from the very beginning of formal education in 1955. The form and extent of practice teaching depend on the year of study and takes place at both the undergraduate (600 h – 45 ECTS) and postgraduate (80 h – 10ECTS) levels. In each academic year, students are required to complete several practical assignments. To support students in acquiring different competencies, the Center for Practical Studies (hereinafter CPS) at Faculty of Social Work was established in 2007 and is responsible for the organisation and implementation of practice teaching (Mesec, Citation2015). Practice teaching is delivered in two forms – as a few hours a week in the first two years of study and as a continuous full-time placement for 4–6 weeks in later years of study. Students have the opportunity to undertake practice teaching in a range of different sectors and organisations (e.g. social care and welfare, education, health, employment), where they come into contact with service users, what triggers different issues and dilemmas (particularly in the lower years of the study). This emphasises the importance of providing students with support that is, in our case, organised as a triangle formed by the supervisor from the FSW, the mentor and the student. An intense collaboration is established between the student and the mentor throughout the practice teaching.

Students are divided into mentoring groups that are facilitated by a supervisor (usually a teaching assistant). In the 1st and 2nd years, up to 15 students meet every fortnight across the study year; in the later years of study, about 20 students meet mostly during field practice period. The main aim of the mentoring groups is to reflect on knowledge gained during practice teaching, address and resolve dilemmas and challenges, integrate theory and practice. All students are individually mentored in an agency by a qualified social worker. The role of the mentor is to introduce the student to the work of a social worker and the organisation and to enable the student (progressively, in higher years) to undertake certain assignments. The supervisor and the mentors meet in different ways during the practice teaching, either with visits to the organisation or at the university. Constant contact between all parties involved (student, supervisor and mentor) is desirable, although this is sometimes difficult to achieve in person, as the practice placement are spread across the country. In this case, ICT applications are usually used (Mesec, Citation2015). The use of ICT turned out to be of a key importance in the time of Covid-19.

Practice teaching during the COVID-19 epidemic

The measures undertaken by the governments to prevent the spread of Covid-19 virus had a strong impact on the implementation of social work education. Practitioners who were accustomed to personally responding to the needs of individuals, families, and/or communities were forced to close the doors of their organisations and convert to remote work (Szczygiel & Emery-Fertitta, Citation2021). Due to Covid-19, many students have had to quit or postpone their practice teaching; some of them have completed it in an adjusted manner to different extents (Hatton et al., Citation2021).

Across the world, practice teaching faced similar limitations (Davis & Mirick, Citation2021) and concerns about using ICT, especially because some service users have no access to it, which prevents them from fully exercising their social rights (García-Castilla et al., Citation2019). Decisions on modifications of practice teaching were made without information on how long the Covid-19 measures that changed practice would last or without considering how to ensure that all students achieved the required practice skills (Davis & Mirick, Citation2021).

Adjustments to practical teaching have been reported in many countries, notably by introducing students to remote work and the use of ICT, reducing the number of hours of practice, enabling students to undertake practice placement in their hometowns and involving them in work on various projects etc. (Buchanan & Bailey-Belafonte, Citation2021; Kourgiantakis & Lee, Citation2020; Morley & Clarke, Citation2020; Nadeak, Citation2020). The restructuring of work at agencies resulted in a failure by some to provide mentoring to students (Davis & Mirick, Citation2021). Sarbu and Unwin (Citation2021) add that the Covid-19 pandemic and the implementation of practice teaching online has also deprived students of what so called silent learning in practice teaching, which usually takes place in day-to-day interactions with agency employees and staff. At the same time, the challenges of distant education should not be overlooked. Some students faced digital poverty (Hatton et al., Citation2021) (i.e. they lacked adequate or sufficiently powerful ICT equipment), others did not have private space at home and still others faced the challenge of how to deal with confidential and stressful situations they encountered in practice teaching ‘breaking into’ their home lives through ICT. Social work educators were sceptical, even before the outbreak of Covid-19, about the online education in terms of student outcomes, competencies, and ethical considerations, as well as the potential negative impact on social integration, critical thinking skills training, and loss of face-to-face social contact (Kilpeläinen et al., Citation2011; Zidan, Citation2015). Research (Lynch et al., Citation2022; Zuchowski et al., Citation2021) has shown that e-placements and online education can be valuable learning opportunities, but should be accompanied by guidance, frameworks, and opportunities to build professional skills in digital environments.

In Slovenia in response to the changed conditions, several adjustments were made in the spring of 2020 for the implementation of the practice teaching itself. These included reduction of the number of hours, adjustment of the tasks, creation of new tasks, adjustment of the content of the practice teaching, possibilities for extension of the period in which practice teaching should take place and additional incentives for students to complete their practice teaching in the home environments. Despite the changed situation, the efforts were made to provide students with access to as many opportunities and experiences (psychosocial support and learning assistance for pupils due to online education, cooperation with older people through video calls or correspondence, civil defence support etc.) as possible to enable them to develop, qualify and acquire skills through evidence-based learning (Kodele & Mešl, Citation2015). It was important for all involved that the students achieved the basic goals of practice teaching despite the changed situation.

Shulman (Citation2005) points out that students learn more about the practice itself based on how mentors interact with them than they do from what mentors tell them about practice. Abrams and Dettlaff (Citation2020) add that this has been especially true during the Covid-19 pandemic, when individuals are even more susceptible to the increased stress that accompanies the traumatic experiences of both vulnerable groups of people and the social workers who work with them.

Methodology

The results presented are based on the data collected for the needs of the evaluation of practice teaching in CPS at FSW in the academic years 2014/2015 and 2019/2020. The population consists of active mentors (mentoring at least one student), as well as students, of the undergraduate programme. Response rates (together with population and sample numbers) of mentors and students are presented in and vary between 37.2% and 57.1% in 2014/2015 and 3.6% and 51.4% in 2019/2020.

Table 1. Populations and samples.

In June 2015 and July 2020, all mentors and students who met the above conditions were invited by email to participate in an online survey conducted by CPS with the aim of assessing practice teaching.

Data were collected using relatively comprehensive questionnaires. The questionnaires for students contained fewer questions (47 in 2015 and 31 in 2020) than the questionnaires for mentors (72 in 2015 and 51 in 2020). The questionnaires (mostly on a 5-point scale) contained a detailed assessment of practice, ratings of task suitability, satisfaction, respondents suggestions and some demographic questions.

To verify the satisfaction with and importance of each factor and element of the practice teaching, we used univariate and bivariate descriptive statistics (calculations of frequencies, Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient, averages) and some graphical representations. We also calculated standard deviations to obtain a sense of the variability of the data. Excel (Microsoft 365, version 2207) and SPSS 25 were used to analyse and present the results. The data obtained from the responses to the open-ended questions were also used and analysed by the qualitative analysis method using the MAXQDA Plus analysis programme 2018.2. We first categorised the text into individual thematic sections, entered these into the MAXQDA programme, divided them into several subcategories and codes, and then analysed the text for its content. The statements from the open questions were marked with letter S or M (which means that the document refers to the students’ or mentors’ answer), followed by the sequential number of statements. To protect personal information, we changed names and other personal information. Ethical approval for the research was granted by the FSW (033-5/2020-13).

For the analysis, we used secondary data from two studies (evaluations) that were not conducted for the purpose of direct comparison (conducting practice teaching under ‘normal’ conditions and during Covid-19) and are therefore limited. Due to the higher dropout rate in participation in the survey on the part of students during the Covid-19 epidemic, the sample of students might be biased. We also see a study limitation in the fact that we only present two aspects that are most relevant to the training (mentors and students); thus, the viewpoint of service users on practice teaching, as well as the viewpoint of supervisors, is missing. The scope of this paper also goes beyond the in-depth qualitative research on the provision and experience of mentoring in emergencies that we believe is also interesting.

Results

The results are organised into three main themes: adjustment of practice teaching, satisfaction with practice teaching, challenges of mentoring. Mentioned themes emerged most frequently in the analysis and that relate to practice in the Covid-19 period or in comparison to the pre-Covid-19 period.

Adjustments of practice teaching

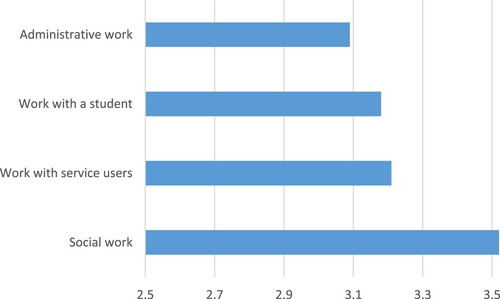

The FSW decided that practice teaching should be carried out to approximately the same extent and with the acquisition of the intended skills, despite the epidemic, and that the way in which it was carried out should be adjusted if necessary. Consequently, the finding that the students rated (on a 5-point scale) various forms of cooperation with different actors as ‘quite present’, both in correspondence and personal contact, is not surprising (). Occasionally (with an average score of 3 or more), another 5 items were rated, indicating the occurrence of online contacts and correspondence with service users and a mentor, and face-to-face contacts with a supervisor. Telephone contacts with a supervisor and online video contacts with a mentor were the least used remote collaboration options.

Figure 1. Student assessments of the frequency of different forms of collaboration with different stakeholders in the 2019/2020 academic year (n = 67–69).

The use of different forms of collaboration for remote work can be attributed to measures to curb the spread of Covid-19 (mentors working from home, taking leave etc.) and consequently to the closure of agencies.

During the state of emergency, we closed the department where student worked for a period of time. The state regulations and the way the work was organised by the superior dictated the presence of professionals in the department, which also affected the contact with the student. (M.111)

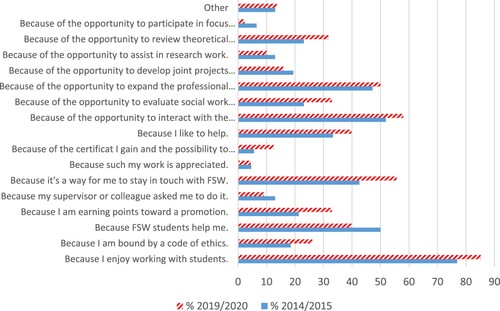

As expected, (see ), some changes in the students’ fields of work occurred during the Covid-19 epidemic. A significant decrease was noted in school counselling, elderly care, addiction volunteer development and quality of life, whereas a slight increase was observed in areas of children and young people and social work centres, among others, in the 2019/2020 academic year. The latter category increased significantly, with mentors most frequently citing youth work (n = 3) and counselling victims of violence (n = 2), as well as homelessness, community work, and association leadership.

Figure 2. Comparison (% of statements) of mentors’ areas of work in the 2014/2015 (n = 86) and 2019/2020 (n = 58) academic years.

On average, mentors rated adjustments in practice teaching due to the Covid-19 situation in the 2019/2020 academic year as quite successful (mean score 3.71 on a 5-point scale, standard deviation 0.98), and less than 9% of them rated the adjustments as unsuccessful.

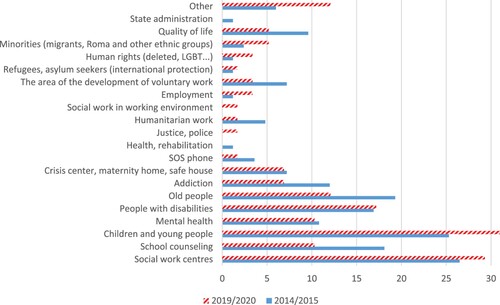

When asked to what extent Covid-19 situation has impacted their work (on a 5-point scale, with 1 representing much less work, 3 representing no change, and 5 representing much more work), mentors estimated (as shown in ) that workload increased in all items (including work with students) during the Covid-19 epidemic, with the amount of social work increasing the most.

On average, the mentors agreed the most and gave the highest average score (on a 5-point scale) on the assessment that students were more familiar with agency work during Covid-19 (see ). By contrast, the greatest differences between the ratings were in their assessment of the extent to which they succeeded in creating situations in which students could collaborate with service users (the only average score below 4).

Table 2. Average grades and dispersion of mentors’ grades of mentoring.

Satisfaction with practice teaching

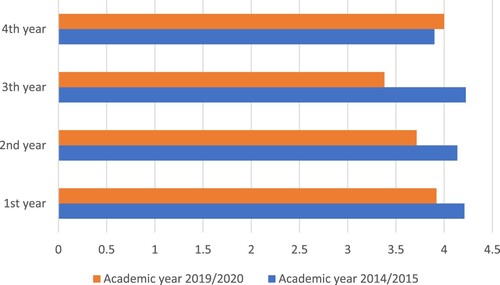

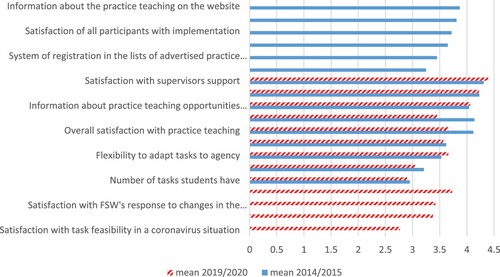

The overall student satisfaction with practice training in the Covid-19 academic year was rated as 3.66, which was significantly lower than in the 2014/2015 academic year when it was 4.12 (on a 5-point scale). Students mostly gave lower satisfaction ratings in academic year 2019/2020.

As shown in , the largest drop in satisfaction among students was in 3rd year of study. The latter was to be expected, as the timing of placements (April and May 2020) meant that their practice teaching was most affected.

Figure 4. Student satisfaction with practice by year of study in academic years 20014/2015 and 2019/2020.

On the other hand, the overall satisfaction of mentors with the practice training was very similar in the two academic years (4.28 in the 2014/2015 and 4.2 in the 2019/2020 academic year) and was higher than the student averages. We can also gain some insights into FSW practice from 2014 to 2020 or during Covid-19 from the basic demographic characteristics of mentors. The gender structure of mentors has not changed over time, as women predominate, accounting for more than 93%. The age structure has also not changed significantly (the average age of mentors is about 41 years, with a standard deviation of almost 9 years). The average total tenure of respondents in the academic year 2019/2020 was slightly lower (14.4 years) than 5 years earlier (16.3 years), while the average tenure in the current position did not differ significantly and amounted to about 9.7 years. Compared to the previous period, the percentage of social work education among professionals in the academic year 2019/2020 was almost 10 percentage points higher (in the academic year 2019/2020, it was 83.1%) than in 2014/2015, and the level of education was slightly higher (a decrease in the number of professionals with a 6th level education and an increase in the number of professionals with 7th or 8th level education).

Among the students, the average satisfaction with the practice teaching during Covid-19 was moderately negatively related (r = −0.45) to ratings of the magnitude of all (various) barriers, implying that students who reported fewer barriers during the practice teaching expressed higher average overall satisfaction with the practice teaching. The latter also showed, on average, the most positive correlation with being enabled (by the mentor) to collaborate with service users (r = 0.55) and being supported by the supervisor to successfully complete tasks (r = 0.54). A high positive correlation was also shown between the items of support from a mentor in practical work and performance of tasks (r = 0.79) and support for practical work and performance of tasks by the supervisor (r = 0.79). A moderate positive correlation (r = 0.66) was also evident between overall satisfaction with mentors and overall student satisfaction with the practice teaching. The latter was also moderately positively correlated (r = 0.61) with the students’ self-assessment of how many skills they had acquired in the practice teaching. Students who gave a higher grade to their practice teaching in the 2019/2020 academic year also estimated, on average, that they gained more in the practice teaching (moderate positive correlation, r = 0.48).

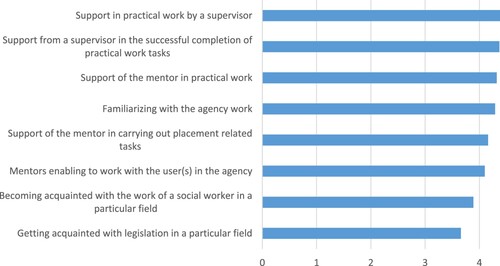

In terms of achieving the intended goals of the practice teaching during Covid-19 (see ), students felt that these were largely achieved (average score above 4 on a 5-point scale), and the support from both mentors received high marks. Regarding the element of learning about the work of the organisation, both mentors and students noted the greatest progress made by students during their practice teaching in the 2014/2015 academic year. The lowest mean scores regarding Covid-19 were the items ‘acquaintance with legislation’ (M = 3.66), which also had the highest dispersion of data among all items, (sd = 1.26) and ‘acquaintance with a social worker’s work in a particular field’ (M = 3.89). Students indicated in their open-ended responses that they gained a great deal of new knowledge and experience from the practice training, especially regarding social work in emergencies.

Figure 5. Student ratings of achievement of practice teaching goals in the 2019/2020 academic year (n = 81 and 82).

shows that students were quite satisfied with most elements of practice teaching in both years of study (mean scores on a 5-point scale are above 3), and they gave the ‘range of available agencies’ and the ‘support from the mentor and supervisor’ the highest mean scores (4 or more on a 5-point scale). Students expressed dissatisfaction (mean scores below 3) only on the elements related to the tasks they had to complete during the practice teaching (especially feasibility and number of tasks). As shown in , even without Covid-19, students gave the task-related elements low ratings, with average scores between 3 and 3.5.

Figure 6. Average ratings of students’ satisfaction with practice teaching in the 2014/2015 (n = 139–148) and 2019/2020 (n = 56–97) academic years.

Students who rated the amount of support they received from the mentor (r = 0.56) and the amount of support they received from the supervisor (r = 0.51) as more appropriate also rated the skills they acquired with a higher overall score. The analysis of the open-ended responses also confirmed that, having the support of supervisors and mentors was particularly important to them.

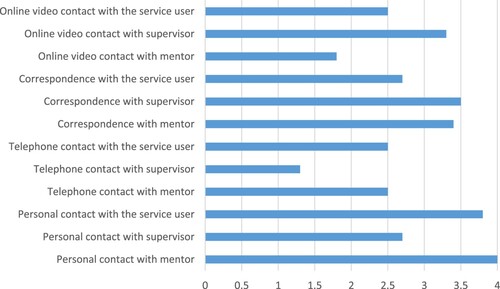

I had a good mentor who was very supportive, both in terms of social work and my practice, and emotionally and morally when I was working remotely. (S44)

Challenges of mentoring students

The most common motive for mentoring (see ) cited by mentors was that they enjoyed working with students, which likely explains the decision to mentor despite the previously mentioned increased workload during Covid-19. With mentions from more than 50% of the mentors, the motive of ‘contact with the profession’ followed in terms of frequency of mentions. In the 2019/2020 academic year (compared to 2014/2015), larger changes (10 percentage points or more) occurred in the motives of ‘maintaining connection with FSW’ and ‘earning points for promotion’, where the frequency of these motives increased, and in the motive ‘because students are helpful to mentors’, where the frequency of mention of this motive decreased. The latter is not surprising, as the analysis of the open-ended responses shows that mentors attributed the challenges related to mentoring, mainly to their workload due to changes in the way they work (changes in the way the agency works, distance learning, the need for additional support for students due to the new challenges caused of practice teaching, infections among staff etc.). In some ways, mentoring students was an additional burden for them rather than additional help to relieve their workload. As some mentors reported, their workload resulted in a lack of time for quality mentoring.

Among other work was reorganisation of work with service users – finding a suitable way to work with a student and for a student to work with a service user with whom a relationship had not yet been established. Sometimes, it was not possible to pay enough attention to the students, and they hung somewhere in between. Understandably, motivation then drops. (M94)

The lack of ICT and/or poor service users’ equipment with ICT was also a challenge that consequently made working remotely an impossibility. Conversely, some mentors also identified individual challenges with the students themselves (e.g. students’ unwillingness to work remotely, their lack of responsiveness, their late decisions to do placement in their agency), which also created an impossible situation for the agency to prepare well for the placement.

Discussion

Organising practice teaching during Covid-19 proved particularly challenging for universities and employers who provided practice teaching for participating students (Sarbu & Unwin, Citation2021). The question of the extent to which we were successful in Slovenia can be interpreted by comparing the implementation of practice teaching in the 2014/2015 and 2019/2020 academic years. The comparison shows similarities in the form and manner (scope, tasks) of implementation and the relative satisfaction of the main actors (students and mentors) with it. Due to the situation in which the second data collection took place the data also show differences which cannot be attributed to a single factor alone (such as development, improvement, or the Covid-19 epidemic).

As previous research has shown, the organisation and the field of work in which students complete their practice teaching are important. Sarid et al. (Citation2009) found that students’ responses to their practice teaching depended on the setting to which they were assigned, and they encouraged students to try out different organisations and different fields.

During the Covid-19 epidemic, the volume of practice teaching in certain areas (e.g. school counselling and elder care) decreased significantly due to the closure of organisations. Conversely, the volume of practice teaching increased in response to a perceived increased need among children and young people (due to distance learning) and, to some extent, in social work centres (due to increasing needs among various groups of service users).

Analysis of the results obtained showed that the measures taken to prevent the spread of the virus forced both students and mentors, to some extent, to find a way to stay in contact with service users. While face-to-face contact with a mentor was still fairly common, despite the emergency, face-to-face contact with service users was slightly less common, on average. Collaboration between students and service users (even if over the phone, via email, or through an online app) was mostly dependent on individual mentors, which is not surprising given that mentors also had different practices in working with service users regarding measures to prevent the spread of virus. The experience of working with service users was important to students for at least two reasons. First, they needed to gain experience in working with service users and based on that experience, to perform specific tasks for practice teaching and, consequently, to acquire needed skills. Secondly, these methods showed them the importance of flexibility and agility in social work, especially in emergencies, in their response to the needs of service users. Alternatively, as Sarbu and Unwin (Citation2021) note in their research, some students (as well as mentors) experienced the new challenges as an opportunity to ‘nudge’ themselves out of their comfort zones and become creative, flexible, and resilient.

As Rape Žiberna and Žiberna (Citation2017) also note, our analysis showed that mentors in Slovenia rated FSW’s practice teaching as quite good (with higher average scores than those given by the students) and emphasised student motivation as the most important element. By contrast, mentors rated the importance of the student’s prior knowledge as almost the least important element of the practice teaching. This shows, on the one hand, the awareness that the mentor and the student (similarly noted by Bălăuţă & Vlaicu, Citation2017) are the main actors in practice teaching and, on the other hand, that mentors find personality traits much more important than prior knowledge (Hay & Brown, Citation2015).

The data analysed show that, on average, students began to use ICT to a greater extent in the 2019/2020 academic year. It replaced face-to-face contact with a supervisor and, to a lesser extent, face-to-face contact with service users and contact with a mentor. The use of ICT has certainly brought about many challenges (lack of ICT, unfamiliarity with its use), not only in the student–service user collaboration, but also in the mentor–student collaboration. The results show that students increasingly interacted with supervisors (mostly in the form of email and web applications), while they interacted with mentors mainly through phone calls and less through web applications (the latter can be mainly attributed to the lack of or poor quality of equipment of agencies with ICT, at least in the first wave of the epidemic). However, those mentors who have had access to ICT should definitely be supported more by FSW in using it for mentoring support to students. It might also be useful to network the mentors even more with each other so that they can share positive experiences and support each other in solving mentoring challenges.

The lack of face-to-face contact with the mentor speaks to the disadvantage of students in silent learning in practice teaching (Sarbu & Unwin, Citation2021). It also raises the question of what this means for student mentoring and, therefore, for the acquisition of the required practical skills. The findings show that mentors were further burdened by adjusting to the new work reality; some of them were not even working as they were forced to use wait time for work or leave. That meant less time for support to students in carrying out social work at the agency, as well as less support from mentors for students in carrying out tasks (which they have as part of their practice teaching). As a result, this could be reflected in a poorer assessment of the acquired skills among the students (the results of the analysis show a relationship between the adequacy of the amount of mentor support and self-assessment of acquired skills). Similarly, also Davis and Mirick (Citation2021) points out that students missed more mentor support during Covid-19, they felt lonely and isolated in terms of professional work because they lacked support. On the other hand, some authors (Urbanc et al., Citation2016) emphasise that mentors also need continuous support and training to be able to support students, which is particularly evident in times of emergency. Finally, the findings show that students who received more support from their mentors were more satisfied with practice teaching, and that mentors who enjoy working with students have decided to continue being mentors also during Covid-19.

On average (in both the 2014/2015 and 2019/2020 academic years), students expressed lower satisfaction with the practice teaching than did their mentors, and the average satisfaction score during COVID-19 was significantly (almost 0.5 points on the 5-point scale) lower than that of the mentors. This is probably also explained by the correlation showing that students’ satisfaction with the practice teaching was most related to the ability to work with service users, which was much lower and more demanding during the Covid-19 epidemic.

Conclusion

The data presented show that the Covid-19 epidemic radically affected the practice teaching of social work students in Slovenia, both in terms of content (areas and scope of work with service users) and the nature of mentoring. Mentors estimated that the burden of mentoring in emergency situations (such as Covid-19) is more demanding (including the changing nature of their work), so schools of social work must be aware of the need to place much emphasis on providing support to mentors and on mentoring training. In this way they will be able to adequately support students in their further professional work, and in acquiring the necessary skills in various situations. Despite the changed situation and the expressed lower satisfaction with practice teaching, students were able to acquire the necessary practical skills with the support of their mentors (in an adapted form). The pandemic thus confirmed that mentoring support for students is crucial and prepares them for contemporary social work practice (Bogo, Citation2014).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tadeja Kodele

Tadeja Kodele, PhD is a teaching assistant at the Faculty of Social Work, University of Ljubljana. She is a qualified social worker. Her research interests mainly cover social work with families, children participation and practice teaching in social work. She has participated in many scientific research projects in various fields. She has presented her research work at several conferences and congresses and in scientific journals.

Tamara Rape Žiberna

Tamara Rape Žiberna, PhD is a teaching assistant at the Faculty of Social Work, University of Ljubljana, where she is a member of the Department of Research and Organization and the Centre for Practical Studies. She is a qualified social worker. Her research interests are mainly related to teamwork in social work, social work research and social work practice education.

References

- Abrams, L. S., & Dettlaff, A. J. (2020). Voices from the frontlines: Social workers confront the COVID-19 pandemic. Social Work, 65(3), 302–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swaa030

- Azman, A., Singh, P. J. S., Parker, J., & Crabtree, S. A. (2020). Addressing competency requirements of social work students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Malaysia. Social Work Education, 39(8), 1058–1065. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1815692

- Bălăuţă, D. S., & Vlaicu, L. (2017). Perceptions of actors involved in social work field placement at the West University of Timişoara. Revista de Asistenţă Socială, XVI(2), 53–56.

- Bogo, M. (2014). Achieving competence in social work through field education. University of Toronto Press.

- Buchanan, C. S., & Bailey-Belafonte, S. J. (2021). Challenges in adapting field placement during a pandemic: A Jamaican perspective. International Social Work, 64(2), 285–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872820976738

- Carrilio, T. E. (2008). Accountability, evidence, and the Use of information systems in social service programs. Journal of Social Work, 8(2), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1468017307088495

- Castillo, J. T., Hendrix, E. W., Nguyen Van, L., & Riquino, M. R. (2021). Macro practice supervision by social work field instructors. Journal of Social Work Education, 58(2), 333–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1885539

- Davis, A., & Mirick, R. G. (2021). COVID-19 and social work field education: A descriptive study of students’ experiences. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(1), 120–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1929621

- Doel, M., & Shardlow, S. M. (2016). Modern social work practice. Teaching and learning in practice settings. Routledge.

- Frost, E., Höjer, S., & Campanini, A. (2013). Readiness for practice: Social work students’ perspectives in England, Italy, and Sweden. European Journal of Social Work, 16(3), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2012.716397

- García-Castilla, F. J., De-Juanas Oliva, A., Vírseda-Sanz, E., & Páez Gallego, J. (2019). Educational potential of E-social work: Social work training in Spain. European Journal of Social Work, 22(6), 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1476327

- Hatton, K., Galley, D., Veale, F. C., Tucker, G., & Bright, C. (2021). Creativity and care in times of crisis: An analysis of the challenges of the COVID-19 virus experienced by social work students in practice placement. Social Work Education, 41(8), 1768–1784. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2021.1960306

- Hay, K., & Brown, K. (2015). Social work practice placements in Aotearoa New Zealand: Agency managers perspectives. Social Work Education, 34(6), 700–715. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2015.1062856

- Hrnčić, J., Polić, S., & Tanasijević, J. (2020). Perspektiva mentora terenske prakse studenata socijalne politike i socijalnog rada (A field placement mentor's perspective of students of social policy and social work(. Year of the Faculty of Political Sciences, 14(23), 255–282.

- IFSW. (2014). Global definition of social work. https://www.ifsw.org/global-definition-of-social-work.

- Kilpeläinen, A., Päykkönen, K., & Sankala, J. (2011). The use of social media to improve social work education in remote areas. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 29(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2011.572609

- Knight, C. (2001). The process of field instruction: BSW and MSW students’ views of effective field supervision. Journal of Social Work Education, 37(2), 357–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2001.10779060

- Kodele, T., & Mešl, N. (2015). Refleksivna uporaba znanja v kontekstu praktičnega učenja (reflexive use of knowledge in the context of practical learning). Socialno Delo, 54(3-4), 189–203.

- Kourgiantakis, T., & Lee, E. (2020). Social work practice education and training during the pandemic: Disruptions and discoveries. International Social Work, 63(6), 761–765. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0020872820959706

- Lefevre, M. (2005). Facilitating practice learning and assessment: The influence of relationship. Social Work Education, 24(5), 565–583. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470500132806

- Lynch, M. W., Dominelli, L., & Cuadra, C. (2022). Information communication technology during COVID-19. Social Work Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2022.2040977

- Martin, E. M., Myers, K., & Brickman, K. (2020). Self-Preservation in the workplace: The importance of well-being for social work practitioners and field supervisors. Social Work, 65(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swz040

- McSweeney, F., & Williams, D. (2018). Social care students’ learning in the practice placement in Ireland. Social Work Education, 37(5), 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2018.1450374

- Mesec, M. (2015). Praktični študij na fakulteti za socialno delo (practical study at the faculty of social work(. Socialno Delo, 54(3-4), 139–248.

- Morley, C., & Clarke, J. (2020). From crisis to opportunity? Innovations in Australian social work field education during the COVID-19 global pandemic. Social Work Education, 39(8), 1048–1057. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1836145

- Nadeak, B. (2020). The effectiveness of distance learning using social media during the pandemic period of COVID-19: A case in Universitas Kristen Indonesia. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29(7), 1764–1772.

- Nordstrand, M. (2017). Practice supervisors’ perceptions of social work students and their placements – an exploratory study in the Norwegian context. Social Work Education, 36(5), 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1279137

- Rape Žiberna, T., & Žiberna, A. (2017). Kaj je pomembno za dobro študijsko prakso v socialnem delu: Pogled mentoric z učnih baz (what is important for good study practice in social work: The view of mentors from learning placements(. Socialno Delo, 56(3), 157–178.

- Raskin, M. (Ed.) (1989). Empirical studies in field instruction. Haworth Press.

- Sarbu, R., & Unwin, P. (2021). Complexities in student placements under COVID-19 moral and practical considerations. Frontiers in Education, 6, 654843. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.654843

- Sarid, O., Anson, J., & Cohen, M. (2009). Reactions of students to different settings of field experience. European Journal of Social Work, 12(1), 101–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691450802221022

- Satka, M., Kääriäinen, A., & Yliruka, L. (2016). Teaching social work practice research to enhance research-minded expertise. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 36(1), 84–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2016.1128779

- Sepulveda-Escobar, P., & Morrison, A. (2020). Online teaching placement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile: Challenges and opportunities. European Journal of Teacher Education, 43(4), 587–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2020.1820981

- Shulman, L. S. (2005). Signature pedagogies in the professions. Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences, 134(3), 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1162/0011526054622015

- Szczygiel, P., & Emery-Fertitta, A. (2021). Field placement termination during COVID-19: Lessons on forced termination, parallel process, and shared trauma. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1932649

- Urbanc, K., Buljevac, M., & Vejmelka, L. (2016). Teorijski in iskustveni okviri za razvoj modela studentske terenske prakse u području socialnog rada (theoretical and experiential frameworks for development of a model of student field practice in the field of social work(. Ljetopis Socijalnog Rada, 23(1), 5–38. https://doi.org/10.3935/ljsr.v23i1.102

- Walsh, C. A., Gulbrandsen, C., & Lorenzetti, L. (2019). Research practicum: An experiential model for social work research. Sage Open, 9(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F2158244019841922

- Walter-McCabe, H. A. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic calls for an immediate social work response. Social Work in Public Health, 35(3), 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2020.1751533

- Wayne, J., Bogo, M., & Raskin, M. (2010). Field education as the signature pedagogy of social work education. Journal of Social Work Education, 46(3), 327–339. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2010.200900043

- Zidan, T. (2015). Teaching social work in an online environment. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 25(3), 228–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2014.1003733

- Zuchowski, I., Collingwood, H., Croaker, S., Bentley-Davey, J., Grentell, M., & Rytkönen, F. (2021). Social work E-placements during COVID-19: Learnings of staff and students. Australian Social Work, 74(3), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2021.1900308