ABSTRACT

The mental well-being of youth is influenced by life events, which affects mental health in adulthood. Social support has been shown to have a buffering effect on the impact such events may have on mental health. This research aimed to explore the effect social support has on risk factors, such as youth delinquency and discrimination from private individuals and authorities and how these influence mental well-being. Drawing on data from a study of Norwegian youth and young adults (n = 2588), gender, trust in others and parents’ background positively influenced mental well-being. Use of alcohol, cannabis and experiences of discrimination negatively influenced mental well-being. Social support moderated these negative effects to various degrees. The findings can be applied to targeted social work interventions aiming to strengthen youths’ well-being and ability to cope with life struggles. Social workers have a strong ally in the youths’ network, and the youths themselves should be key players in selecting their supporters.

SAMMENDRAG

Ungdoms psykiske helse påvirkes av livshendelser, og effekten av disse kan vedvare inn i voksen alder. Sosial støtte har vist seg å moderere den negative effekten slike hendelser kan ha på psykisk helse. Denne studien hadde som mål å utforske hvilken effekt sosial støtte har på ulike risikofaktorer, som ungdomskriminalitet og diskriminering fra privatpersoner og myndigheter, og hvordan disse påvirker psykisk helse. Basert på data fra en stor studie av ungdom og unge voksne i Norge (n = 2588) fant denne studien at kjønn, tillit til andre og foreldres bakgrunn hadde en positiv effekt på psykisk helse. Hyppigere bruk av alkohol, cannabis og opplevelser av diskriminering påvirket psykisk helse negativt. Sosial støtte modererte de negative effektene i ulik grad. Funnene kan anvendes i målrettede intervensjoner av sosialarbeidere som har som mål å styrke unges trivsel og evne til å mestre livsutfordringer. Sosialarbeidere har en sterk alliert i ungdoms nettverk av venner og familie, og ungdommene bør selv være sentrale aktører i valg av støttespillere.

Introduction

Social workers engage in broad prevention efforts and more specialised services for youth facing complex challenges such as mental health issues and drug dependency (Wells et al., Citation2013). The Nordic countries have adopted a multiagency approach to address these concerns and coordinate efforts among governmental support services; this approach aims at lowering the threshold for cooperation and dialogue between agencies to ensure better-tailored services to youth at risk (Gundhus et al., Citation2008; Sloper, Citation2004).

One important societal concern is adolescents’ mental health because this is a cornerstone of their growing up and a potential indicator of later-in-life struggles; hence, both the broad and specialised efforts made to ensure the well-being of adolescents are an important investment in their present possibilities and in the future adult population. Research has found strong indications that adolescent depression increases the risk of suffering from depression and anxiety in adulthood (Johnson et al., Citation2018). This relationship is also found between adolescent use of cannabis and later-in-life depression (Gobbi et al., Citation2019). Other life experiences may also harm mental health, such as racial discrimination (Straiton et al., Citation2019), frequency of consumption of alcohol or stronger substances (Boden et al., Citation2020) and being involved in high-rate offending (Jennings et al., Citation2019). However, protective factors can reduce the adverse effects of these experiences. One important protective factor is social support from close friends or family (Bauer et al., Citation2021). This effort is crucial for maintaining mental well-being and recovering from modest to severe mental health problems (Bjørlykhaug et al., Citation2021). The aim of this research is to explore how the above risk factors influence Norwegian youths’ and young adults’ mental well-being and to what extent social support affects the relationship between substance use, delinquency, discrimination and mental well-being, itself.

Literature review

Discrimination & well-being

Studies exploring the link between discrimination and mental health have found that perceived racial discrimination impacts well-being (Anderson, Citation2013; Lewis et al., Citation2014), and overt and subtle discrimination have different effects. Overt discrimination leads to a reduction in positive affect, while subtle discrimination is more associated with depressive symptoms (Noh et al., Citation2007). Similar results were found in a meta-analytical review of perceived discrimination and adverse health outcomes (Pascoe & Richman, Citation2009). Perceived discrimination has a significant negative impact on both physical and mental health and produces stress responses. Such discrimination is also found to increase unhealthy behaviour, such as alcohol and substance abuse, while reducing healthy behaviour, such as maintaining physical health and safe sex (Pascoe & Richman, Citation2009).

However, there are important gender differences regarding discrimination. For example, Arab American men experienced a stronger negative impact on mental health than Arab American women (Assari & Lankarani, Citation2017). Cultural and ethnic background was also identified as an influencing factor in a study of Chinese and Australian students (Zhao et al., Citation2022). Also, immigrants in Norway were affected by racial discrimination, leading to a higher risk for mental health problems (Straiton et al., Citation2019).

Alcohol/drugs & mental well-being

Alcohol and other substances can negatively influence mental health (Das et al., Citation2016). For instance, the early debut of alcohol and drug use are important indicators of mental health problems among adolescents (Skogen et al., Citation2014). Both substance use and cannabis use are associated with mental health problems, and among those adolescents who confirmed a substance use problem, the majority also reported mental health problems (Brownlie et al., Citation2019). This tendency continues into adulthood because the early consumption of a large volume of alcohol and symptoms of alcohol use disorder lead to both substance use disorders and mental health disorders (Boden et al., Citation2020). There is also more frequent problematic alcohol and substance use among adolescents receiving psychiatric care than among those not (Heradstveit et al., Citation2019). As a contemporary factor, COVID-19 has through social isolation and less social support, to name a few, negatively impacted youth mental health and substance use and positively influenced service demand (Zolopa et al., Citation2022).

Delinquency & mental well-being

The pathways between offending and mental health have been explored both ways, with mixed results. Past research has found a substantial mental health problem in juvenile offenders (Teplin et al., Citation2002) and that oppositional defiant problems are a strong predictor of violence (Wareham & Boots, Citation2012). However, a recent Dutch study concluded that screening for mental health problems among young detainees offered a poor likelihood of identifying future perpetrators of violent crime (Colins & Grisso, Citation2019). Studies from the US showed that marginalised communities are more strongly policed than others and that negative experiences from contact with the police are associated with poorer mental health outcomes (Thompson et al., Citation2021). Additionally, there is a link between high-rate offending and depression (Jennings et al., Citation2019), with depression having an independent effect on delinquency (Ozkan et al., Citation2019).

Theoretical framework: social support

Social support has a positive effect on mental and physical health, moderating the effects of many adverse life experiences (Harandi et al., Citation2017). However, social support is complex, and its effect relates to what kind of support is given and by whom. One distinction has been to separate the instrumental and nurturant parts (Cutrona & Russell, Citation1990). In short, instrumental support can be providing a physical favour or helping someone out financially to ease stress. Nurturant support refers to the emotional dimension and can encompass sitting down with a person who is struggling, giving time and attention and providing care (Cutrona et al., Citation1990; Cutrona & Russell, Citation1990). Some interventions attempting to improve the well-being of adolescents with severe life struggles have a socio-ecological foundation resting on the hypothesis that adolescents’ close surroundings influence risk factors and their well-being and behaviour (Blankestein et al., Citation2019; Bronfenbrenner, Citation1981). Bronfenbrenner shifted the attention from the ‘troubled child’ to understanding how the developing child or adolescent is influenced by their surroundings and actively responds to the surroundings (Darling, Citation2007). Hence, the quality and quantity of the available social support may influence an adolescent in various ways. Further, measures can be taken to improve this. For instance, a version of multisystemic therapy (MST) can improve families’ ability to provide social support (Blankestein et al., Citation2019), and parents’ ability to mobilise social support impacts both adolescents’ mental health and their future ability to mobilise social support (Bauer et al., Citation2021). In a Spanish study, adolescent participants chose sources of support that were familiar, friendly and mature, indicating the value of family members (Camara et al., Citation2017). In Israel, the same type of social support moderated the negative effect of exposure to rocket attacks on depression, aggression and severe violence (Shahar & Henrich, Citation2016).

To date, important research findings within the social work and mental health contexts are found. For instance, a Dutch study on family group conferences found that the quality of social support significantly increased after family group conferences, as well as clients’ resilience and living conditions improved as well (de Jong et al., Citation2016). In a study of adults with mental health issues, both availability and adequacy of social support influenced satisfaction with various life domains, with availability producing the strongest effects (Baker et al., Citation1992).

The present research applies the lens of social support. Because social support can moderate the impact of adverse life experiences, exploring what kind of factors are affected and to what degree social support moderates these effects on mental well-being can move our understanding of this protective factor forward. The findings on this topic are of great relevance to social workers and less systemically oriented professions who might expand their therapeutic strategies to also encompass the network around youth and youth adults.

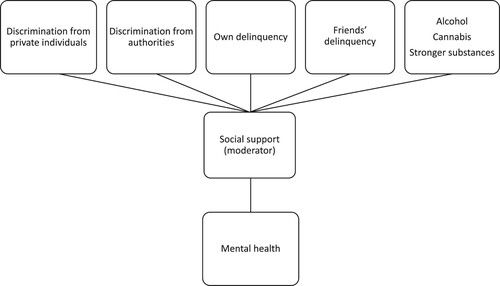

Interaction model of factors influencing mental well-being

illustrates which influencing factors the present research explores in relation to mental well-being. Importantly, this research differentiates between discrimination from authorities, such as the police and child protection services, and from private individuals. Also, because social support moderates the effect of adverse life experiences on mental well-being (Bauer et al., Citation2021), social support was added.

Methodology

The present study used data from a cross-sectional survey of Norwegian youth and young adults. The survey was emailed to students in 42 Norwegian upper secondary schools and the clients of 28 follow-up services. Although the number of follow-up services throughout Norway is challenging to quantify, the 42 schools comprise approximately 10% of the total number of upper secondary schools in Norway. The preferred mode of data collection was through in-class sessions, in which the students replied individually. However, because of COVID-19, in December 2021 and January 2022, numerous schools were forced to reprioritise alternative activities during school hours.

The survey gathered responses from 2,588 youth and young adults (56.3% of whom were female). Most participants had both parents born in Norway (71.2%). However, 13.7% had one of their parents born outside of Norway, while 15.1% had both parents born outside of Norway. Hence, nearly 30% of the study participants can had an ethnic or cultural background other than from Norway. The vast majority of responses were from those between the ages of 16 and 18 (92.5%), and 2.6% were not currently in school or daily work. See below for details.

Table 1. Region of Norway and places of living.

Measurements

The outcome variable was mental well-being, as measured by the WHO-5 scale, a five-question screening instrument for mental well-being in which participants react on a 6-point Likert scale from ‘All of the time’ to ‘At no time’. The questions were noninvasive, and the WHO-5 has been shown to be an outcome indicator in clinical trials and a reliable indicator of depression. The scores were scored by summing them, with a minimum of 0 (lack of well-being) and maximum of 25 (maximum well-being). This can be multiplied by four to get a percentage scale (Kaiser & Kyrrestad, Citation2019; Topp et al., Citation2015). In the current study, the original scale from 0 to 25 was kept. The scale was examined for internal consistency and found to have a high level of internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.85. Although the WHO-5 provided an indication of depression, the present research had a broader approach to mental health than specific symptoms or diagnostic criteria. The WHO-5 questions tapped into the subjective mental well-being of the study participants, functioning as a generic indicator of well-being (Topp et al., Citation2015),

Several measures were used as predictor variables. Social support was assessed after WHO-5, making use of the same scale by assessing the statement, ‘The last two weeks, I have felt that my closest (family and/or friends) support me and care about me’. Both the scale for mental well-being and social support were inverted for a more intuitive interpretation of the regression coefficients.

Youth delinquency was measured by two questions: how many times during the last six months the participant had been in contact with the police regarding a criminal offence or how many times their friends had been in this situation. This was scored on a 4-point Likert scale from 0 to 3, where 0 indicated never and 3 ‘six times or more’. Both questions regarding own and friends’ contact with the police were measured on this scale and informed the analysis with an indication of youth delinquency. In addition to the frequency of contact with police, the present study applied the frequency of alcohol, cannabis and stronger substance use as a predictor variable. Three questions about the frequency of alcohol, cannabis and stronger substance consumption that led to the participant being intoxicated during the past six months were asked. The questions were answered using the same scale as the frequency of contact with the police. The measure for discrimination had two dimensions: discrimination from authorities (such as the police or child protection service) and discrimination from private individuals. This was measured on a scale from 0 to 4, where 0 indicated ‘never’ and 4 indicated ‘very often’.

In addition to the measures, several control variables were included: age, gender, general trust in other people and family background. Trust was originally measured on a 10-point Likert scale, where 0 indicated most people are not to be trusted and 10 the opposite. The scale was collapsed into a 5-point Likert scale where scores of 1 and 3 would be the new one and so on.

Although the original 10-point Likert scale was not validated with this phrasing, 10-point Likert scales of various kinds have been used by both research institutions and government statistical agencies to measure trust on various levels (Friestad & Hansen, Citation2004; Statistisk Sentralbyrå, Citation2012). The family background variable consisted of (0) both parents being born in Norway, (1) one parent being born in Norway and (2) none of the parents born in Norway.

Results

The 2,588 participants had a mean WH0-5 score of 14.3. Additionally, 33.8% had a WHO-5 score under the threshold level, indicating the need to screen further for depression.

A hierarchical multiple regression was calculated to analyse the impact of delinquency, alcohol and substance use, experienced discrimination from private individuals and authorities, trust, gender, age and family background on mental well-being. A significant regression was found (F(12,2340) = 103,426, p = 0.000) with an adjusted R2 of .347. Six significant predictor variables were found, including social support. All variables, excluding social support, were introduced in the first regression sequence. In the final sequence, social support was added. Change in percentage in the unstandardised coefficient B after including social support is shown in parentheses in .

Table 2. Hierarchical regression.

Having a different family background than both parents born in Norway increased mental well-being. When social support was added in the second regression, the positive effect of family background on mental well-being was strengthened. Higher general trust in other people had a positive significant influence on mental well-being. For each unit increase in general trust in others, a 0.639 increase in mental well-being was found. The positive effect of trust on mental well-being was reduced by 36.9% when social support was added to the regression. Also, a positive influence of being male on mental well-being was found. When gender went from zero (being female) to 1 (being male), the mental well-being score increased by 2.184. This positive relationship dropped by 14.1% when social support was added.

Experiences of being discriminated against by individuals (both peers and adults) had a negative influence on mental well-being. For each unit increase in experienced discrimination, the mental well-being score dropped by 0.273. This effect was reduced by 60.0% when social support was added in the second sequence, indicating a strong moderating effect on the relationship between discrimination and mental well-being by social support.

In addition, more frequent use of alcohol and cannabis negatively influenced mental well-being. For each unit increase in alcohol or cannabis consumption (indicating more frequent use in the last six months), the mental well-being score dropped by 0.286 and 0.391, respectively. When social support was added, the effect of alcohol and cannabis use on mental well-being dropped by 0.7% and 42.2%.

In addition to exploring how social support influenced the effect of the other variables on the participants’ mental well-being, social support also had a significant influence on mental well-being. For each unit increase in perceived social support, the mental well-being score increased by 1.976.

Discussion

The current research adds several important pieces to the puzzle of how social support contributes to strengthening youth and young adults. One unique aspect was the distinction between the experiences of discrimination between individuals and authorities. However, only discrimination regarding individuals was found to negatively affect the participants’ mental health. This form of discrimination was substantially reduced when perceived social support was added. The three factors with a significant effect on mental health that were the most affected by social support were general trust in other people, frequency of cannabis consumption and experienced discrimination from individuals.

Following this, the discussion will lastly focus specifically on social work practice and how social support’s moderating effect can be harnessed by practitioners, clients and their families. How can social support reduce the negative effect of risk factors and adverse experiences on mental well-being? When social support moderates the negative effect of discrimination and cannabis use on mental well-being, it may add a sense of belonging and feeling connected to others. This may occur if social support is provided through both instrumental and nurturant support. Although nurturant support immediately appears to be the most relevant, being given advice, counselling or actual favours may ease the experienced burden of discrimination and potential challenges created by more frequent use of cannabis.

In a recent scoping review, social support for individuals with mental health problems was provided through both direct and indirect strategies. Direct strategies of social support could be through activities in which interpersonal relationships are facilitated or maintained, while indirect strategies could be through financial or housing support (Bjørlykhaug et al., Citation2021). Within these activities, bonds between individuals are created or possibly strengthened. The literature called for more research focusing on the mechanisms of social support (Reblin & Uchino, Citation2008). This call was answered by, among others, Thoits (Citation2011), who argued that social support can work through belonging and companionship, as well as mattering to other important people.

Although discrimination negatively affects mental health, this is partially mediated by causing a poorer sense of belonging to a community or society (Ferdinand et al., Citation2015; Jackson et al., Citation2020), especially for refugees or newly arrived citizens (Correa-Velez et al., Citation2010). In the latter group, mental well-being was mostly affected by indicators of belonging, such as perceived discrimination or bullying (Correa-Velez et al., Citation2010). This can have a substantial negative effect on newly arrived citizens, such as refugees and asylum seekers (Szaflarski & Bauldry, Citation2019; Ziersch et al., Citation2020). A stronger experience of belonging moderates the adverse effects of discrimination on mental health (Lincoln et al., Citation2021). Feeling connected to and belonging to others is also a predictor of fewer physical health-related problems (Hale et al., Citation2005).

Although recent studies highlighted high levels of mental well-being among habitual cannabis users (Morais et al., Citation2022), adverse effects from frequent use were well documented. A recent Lancet systematic review found that cannabis use produced both positive (such as hallucinations) and negative (such as emotional blunting and amotivation) mental health symptoms (Hindley et al., Citation2020). Also, for long-time users, a range of personality disorders and lower social support can arise (Cougle et al., Citation2020). The current findings of social support moderating the negative effect of more frequent cannabis use on mental health likely tap into this relationship. The buffering effect ‘added’ by feeling connected to others or belonging to a community may provide a substantial impact on how and how much the relationship between cannabis use and mental well-being operates. As in the present study, past research has found an association between more frequent alcohol use among adolescents and young adults and mental health challenges (Pedrelli et al., Citation2016; Strandheim et al., Citation2009). In contrast to the above factors, this influence was stable after including social support in the current study.

Although both experiences of discrimination and more frequent cannabis use intuitively make sense in relation to poorer mental well-being, the findings regarding trust are not as intuitive. Although the present study did not find that higher levels of trust and having available social support are the same, other research findings underlined this. Young adults regularly in contact with close networks also more often ask for their advice and support (Lazányi, Citation2017). Also, when children and adolescents witness that their close ones are trusting and supportive of their community, they internalise and adopt this attitude (Van Lange, Citation2015). This relationship is assumed to be stronger in high-trust societies (such as Norway) and may strengthen the experience that other people can be trusted (Bi et al., Citation2021). This can explain why general trust in others’ influence on mental well-being was substantially reduced when the social support variable was included.

Finally, because data collection was carried out in late 2021 and early 2022, COVID-19 influenced Norwegian upper secondary schools. With many schools returning to partially digital schooling, this may have been a contributing factor regarding mental well-being. Although the present research did not assess COVID-19’s impact on youth’s mental well-being, it must be taken into account when assessing the findings.

Recommendations for social work practice

The findings have a substantial contribution to social work practice by underlining the importance of working broadly with the network around social workers’ clients. Developing clinical tunnel vision and individualising complex issues such as mental well-being challenges, addiction and discrimination have been debated among social work scholars following the neoliberal influence on policy and practice (Brockmann & Garrett, Citation2022). However, the present research has shown that such experiences are deeply connected and that some common ground can be found when searching for a solution.

Social workers should early on map out the close and more distant network of their clients after establishing contact. This has been argued for, as shown by Ennis and West (Citation2013). Social network analysis may support researchers in exploring avenues for social change and practitioners to find more tailored support and intervention services (Rice & Yoshioka-Maxwell, Citation2015). However, this should be done in close partnership with the client(s).

Adolescents are heavily impacted by their peers, and they adjust to their social environments in accordance with expectations, including risk-taking, such as illegal activities. Additionally, the opinions of other teens on risk-taking affect the younger adolescent population more than the opinions of adults (Knoll et al., Citation2015). Following this, there should be greater awareness of both mapping out young adolescents’ networks and reaching out to identified sources of positive influences. Along with youth and their parents, social workers working in general or targeted intervention services should explore the youths’ network to facilitate positive interactions with individuals who may provide inclusion into healthy communities and behaviour. If done properly, this might provide a low-cost and high-efficiency supplement to professional services. This recommendation is in line with ideals in social work practice to empower clients (International Federation of Social Workers, Citation2014) and have their own perspectives and solutions as points of departure. Although concern has been raised that social workers’ empowerment efforts may run the risk of an over-responsibilisation of individuals (Rivest & Moreau, Citation2015), the argument in the current study is to facilitate client empowerment through their network. Having the clients in a leading role in this part of social workers’ services is highly recommended (Duncan & Miller, Citation2000), and having their perspectives and solutions to the problem at hand is an important predictor of a positive outcome from interventions (Miller et al., Citation2005). Formal support, from professionals such as mental health counsellors or social workers, has in past research found to be perceived as conditional, while support between private individuals was experienced as unconditional by clients with mental health issues (Dunér et al., Citation2012). This highlights the importance of facilitating social support from peers and family members, not only from professionals. However, social workers may be important in creating spheres where such support needs are communicated and potentially met.

Importantly, there are significant European country variations found between levels of trust, available social support and health, with high scores in high-trust societies such as Norway and Denmark (Bi et al., Citation2021; von dem Knesebeck & Geyer, Citation2007). Also, the availability of social workers and other welfare professionals differs between European countries. In Norway and the other Scandinavian countries, social, welfare and health services are a public responsibility and funded by the government (Gunnarsdóttir, Citation2016; OECD, Citation2021). Hence, substantial variations in trust, social support, health outcomes and the availability of social and welfare services may be found across regions and countries in Europe. These macro factors have implications for social workers’ ability to reach their target group and the extent to which networks or peers are available and might impact their close ones.

Recommendations for future research

The present research cannot distinguish between the quality or quantity of social support and whether close friends or family were considered the most important.

The present study utilised a one-item question to measure social support, which did not distinguish between nurturant and instrumental support. Future studies should consider using a three-item scale for social support (OSSS-3). The OSSS-3 was found to be valid and reliable, with one factor explaining nearly 60% of the total variance. The OSSS-3 scale asks for the number of people close to the respondent on whom the respondent can rely for support, how much interest others have in what the respondent does and how easy it is for the respondent to get help if needed, here answered on a 4/5-point Likert scale (Kocalevent et al., Citation2018). This might help better distinguish between the overall effect from social support and possibly subscales of instrumental or nurturant support.

Also, as encouraged by Cutrona and Russell (Citation1990), studies should be specific regarding what kind of social support is being studied in relation to various life challenges. Because both gender and family background have an important influence on mental well-being while not being substantially influenced by social support, future research should explore whether these factors can be understood through different empirical and conceptual frameworks.

Because the present study was designed to be feasible for upper secondary schools and their students, several potentially important variables were left out to make the survey as short as possible. Future studies should, in addition to a more nuanced measure for social support, include measures of socio-economic background, such as financial security and parental work situation. Finally, although there is reason to believe conducting an in-classroom survey will increase the number of responses, giving the students the option of potentially responding outside of the classroom might put less pressure on them, especially on sensitive topics such as mental well-being.

Conclusion

The present research explored how various risk factors, such as substance use, youth delinquency and discrimination, influence Norwegian youths’ and young adolescents’ mental well-being. Additionally, these factors were explored in relation to social support. Based on data from a nationwide survey with 2,588 participants, the current research showed that social support has a moderating effect on the negative impact of experienced discrimination and more frequent cannabis use. When social support was added to the hierarchical regression, these two risk factors had a reduced negative influence on mental well-being. Additionally, social support itself had a substantial positive impact on mental well-being.

Social workers have a strong ally in the network around their clients, which should be engaged with to fuel positive changes together with the social workers’ interventions and efforts. However, these supporters should not be picked and chosen by parents, professionals or other adults alone. In this case, exploring the clients’ own perspectives regarding who may be helpful and supportive is in line with social work ideals and traditions, leading to more effective course from the onset.

Future studies should be designed to capture the nuances in social support and distinguish the effect from nurturant and instrumental support, as well as their combined impact on risk factors and well-being.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Håvard Haugstvedt

Håvard Haugstvedt is a clinical social worker and research fellow in the Youth and Extremism project at C-REX. His main research areas include social work, prevention work against violent extremism and violent nonstate actors’ use of armed drones in conflicts. Håvard finished his PhD at the University of Stavanger in 2021 with the dissertation ‘Managing the tension between trust and security: A qualitative study of Norwegian social workers’ experience with preventing radicalisation and violent extremism’. Prior to his doctoral research, Håvard had 15 years of experience working with at-risk youth and young adults struggling with addiction, mental health issues and crime.

References

- Anderson, K. F. (2013). Diagnosing discrimination: Stress from perceived racism and the mental and physical health effects*. Sociological Inquiry, 83(1), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-682X.2012.00433.x

- Assari, S., & Lankarani, M. M. (2017). Discrimination and psychological distress: Gender differences among Arab Americans. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 1–10. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389fpsyt.2017.00023 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00023

- Baker, F., Jodrey, D., & Intagliata, J. (1992). Social support and quality of life of community support clients. Community Mental Health Journal, 28(5), 397–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00761058

- Bauer, A., Stevens, M., Purtscheller, D., Knapp, M., Fonagy, P., Evans-Lacko, S., & Paul, J. (2021). Mobilising social support to improve mental health for children and adolescents: A systematic review using principles of realist synthesis. PLOS ONE, 16(5), Article e0251750. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251750

- Bi, S., Stevens, G. W. J. M., Maes, M., Boer, M., Delaruelle, K., Eriksson, C., Brooks, F. M., Tesler, R., van der Schuur, W. A., & Finkenauer, C. (2021). Perceived social support from different sources and adolescent life satisfaction across 42 countries/regions: The moderating role of national-level generalized trust. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50(7), 1384–1409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01441-z

- Bjørlykhaug, K. I., Karlsson, B., Hesook, S. K., & Kleppe, L. C. (2021). Social support and recovery from mental health problems: A scoping review. Nordic Social Work Research, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2020.1868553

- Blankestein, A., van der Rijken, R., Eeren, H. V., Lange, A., Scholte, R., Moonen, X., Vuyst, K. D., Leunissen, J., & Didden, R. (2019). Evaluating the effects of multisystemic therapy for adolescents with intellectual disabilities and antisocial or delinquent behaviour and their parents. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(3), 575–590. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12551

- Boden, J., Blair, S., & Newton-Howes, G. (2020). Alcohol use in adolescents and adult psychopathology and social outcomes: Findings from a 35-year cohort study. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 54(9), 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867420924091

- Brockmann, O., & Garrett, P. M. (2022). ‘People are responsible for their own individual actions’: Dominant ideologies within the neoliberal institutionalised social work order. European Journal of Social Work, 25, 880–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2022.2040443

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1981). Ecology of human development experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press.

- Brownlie, E., Beitchman, J. H., Chaim, G., Wolfe, D. A., Rush, B., & Henderson, J. (2019). Early adolescent substance use and mental health problems and service utilisation in a school-based sample. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 64(2), 116–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743718784935

- Camara, M., Bacigalupe, G., & Padilla, P. (2017). The role of social support in adolescents: Are you helping me or stressing me out? International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 22(2), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2013.875480

- Colins, O. F., & Grisso, T. (2019). The relation between mental health problems and future violence among detained male juveniles. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 13(1), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-019-0264-5

- Correa-Velez, I., Gifford, S. M., & Barnett, A. G. (2010). Longing to belong: Social inclusion and wellbeing among youth with refugee backgrounds in the first three years in Melbourne, Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 71(8), 1399–1408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.018

- Cougle, J. R., McDermott, K. A., Hakes, J. K., & Joyner, K. J. (2020). Personality disorders and social support in cannabis dependence: A comparison with alcohol dependence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 265, 26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.029

- Cutrona, C. E., Cohen, B. B., & Igram, S. (1990). Contextual determinants of the perceived supportiveness of helping behaviours. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7(4), 553–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407590074011

- Cutrona, C. E., & Russell, D. W. (1990). Type of social support and specific stress: Toward a theory of optimal matching. In I. G. Sarason, B. R. Sarason, & G. R. Pierce (Eds.), Social support: An interactional view (pp. 319–366). John Wiley & Sons.

- Darling, N. (2007). Ecological systems theory: The person in the center of the circles. Research in Human Development, 4(3–4), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600701663023

- Das, J. K., Salam, R. A., Arshad, A., Finkelstein, Y., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016). Interventions for adolescent substance abuse: An overview of systematic reviews. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(4 Suppl), S61–S75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.021

- de Jong, G., Schout, G., Meijer, E., Mulder, C. L., & Abma, T. (2016). Enabling social support and resilience: Outcomes of family group conferencing in public mental health care. European Journal of Social Work, 19(5), 731–748. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2015.1081585

- Duncan, B. L., & Miller, S. D. (2000). The client’s theory of change: Consulting the client in the integrative process. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 10(2), 169–187. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009448200244

- Dunér, A., Nordström, M., & Skärsäter, I. (2012). Support networks and social support for persons with psychiatric disabilities—A Swedish mixed-methods study. European Journal of Social Work, 15(5), 712–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2011.577736

- Ennis, G., & West, D. (2013). Using social network analysis in community development practice and research: A case study. Community Development Journal, 48(1), 40–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bss013

- Ferdinand, A. S., Paradies, Y., & Kelaher, M. (2015). Mental health impacts of racial discrimination in Australian culturally and linguistically diverse communities: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health, 15(1), Article 401. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1661-1

- Friestad, C., & Hansen, I. L. S. (2004). Levekår blant innsatte (No. 429). FAFO. https://www.fafo.no/zoo-publikasjoner/fafo-rapporter/levekar-blant-innsatte.

- Gobbi, G., Atkin, T., Zytynski, T., Wang, S., Askari, S., Boruff, J., Ware, M., Marmorstein, N., Cipriani, A., Dendukuri, N., & Mayo, N. (2019). Association of cannabis Use in adolescence and risk of depression, anxiety, and suicidality in young adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(4), 426–434. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4500

- Gundhus, H. I., Egge, M., Strype, J., & Myhrer, T.-G. (2008). Modell for forebygging av kriminalitet? Evaluering av samordning av lokale kriminalitetsforebyggende tiltak (SLT) (PHS forskning No. 4). Politihøgskolen.

- Gunnarsdóttir, H. M. (2016). Autonomy and emotion management. Middle managers in welfare professions during radical organizational change. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 6(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.19154/njwls.v6i1.4887

- Hale, C. J., Hannum, J. W., & Espelage, D. L. (2005). Social support and physical health: The importance of belonging. Journal of American College Health, 53(6), 276–284. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.53.6.276-284

- Harandi, T. F., Taghinasab, M. M., & Nayeri, T. D. (2017). The correlation of social support with mental health: A meta-analysis. Electronic Physician, 9(9), 5212–5222. https://doi.org/10.19082/5212

- Heradstveit, O., Skogen, J. C., Hetland, J., Stewart, R., & Hysing, M. (2019). Psychiatric diagnoses differ considerably in their associations with alcohol/drug-related problems among adolescents. A Norwegian population-based survey linked with national patient registry data. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1–16. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389fpsyg.2019.01003 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01003

- Hindley, G., Beck, K., Borgan, F., Ginestet, C. E., McCutcheon, R., Kleinloog, D., Ganesh, S., Radhakrishnan, R., D’Souza, D. C., & Howes, O. D. (2020). Psychiatric symptoms caused by cannabis constituents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(4), 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30074-2

- International Federation of Social Workers. (2014, July). What is social work? Global definition of social work. International Federation of Social Workers. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work.

- Jackson, Z. A., Harvey, I. S., & Sherman, L. D. (2020). The impact of discrimination beyond sense of belonging: Predicting college students’ confidence in their ability to graduate. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 0(0), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120957601

- Jennings, W. G., Maldonado-Molina, M., Fenimore, D. M., Piquero, A. R., Bird, H., & Canino, G. (2019). The linkage between mental health, delinquency, and trajectories of delinquency: Results from the boricua youth study. Journal of Criminal Justice, 62, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2018.08.003

- Johnson, D., Dupuis, G., Piche, J., Clayborne, Z., & Colman, I. (2018). Adult mental health outcomes of adolescent depression: A systematic review. Depression and Anxiety, 35(8), 700–716. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22777

- Kaiser, S., & Kyrrestad, H. (2019). Måleegenskaper ved den norske versjonen av Verdens helseorganisasjon Well- Being Index (WHO-5). PsykTestBarn, 1(4), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.21337/0063

- Knoll, L. J., Magis-Weinberg, L., Speekenbrink, M., & Blakemore, S.-J. (2015). Social Influence on Risk Perception During Adolescence. Psychological Science, 26(5), 583–592. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615569578

- Kocalevent, R.-D., Berg, L., Beutel, M. E., Hinz, A., Zenger, M., Härter, M., Nater, U., & Brähler, E. (2018). Exploring narratives of resilience among seven males living with spinal cord injury: A qualitative study. BMC Psychology, 6(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-017-0211-2

- Lazányi, K. (2017). Social support of young adults in the light of trust. Economics & Sociology, 10(2), 140–152. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2017/10-2/10

- Lewis, T. T., Williams, D. R., Tamene, M., & Clark, C. R. (2014). Self-reported experiences of discrimination and cardiovascular disease. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports, 8(1), Article 365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12170-013-0365-2

- Lincoln, A. K., Cardeli, E., Sideridis, G., Salhi, C., Miller, A. B., Fonseca, T. D., Issa, O., & Heidi Ellis, B. (2021). Discrimination, marginalization, belonging and mental health among Somali immigrants in North America. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 91(2), 280–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000524

- Miller, S. D., Mee-Lee, D., Plum, B., & Hubble, M. A. (2005). Making treatment count: Client-directed, outcome-informed clinical work with problem drinkers. In J. L. Lebow (Ed.), Handbook of clinical family therapy (pp. 281–308). John Wiley & Sons.

- Morais, P. R., Nema Areco, K. C., Fidalgo, T. M., & Xavier da Silveira, D. (2022). Mental health and quality of life in a population of recreative cannabis users in Brazil. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 146, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.12.010

- Noh, S., Kaspar, V., & Wickrama, K. a. s. (2007). Overt and subtle racial discrimination and mental health: Preliminary findings for Korean immigrants. American Journal of Public Health, 97(7), 1269–1274. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2005.085316

- OECD. (2021). Norway: Country health profile 2021. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/norway-country-health-profile-2021_6871e6c4-en.

- Ozkan, T., Rocque, M., & Posick, C. (2019). Reconsidering the link between depression and crime: A longitudinal assessment. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 46(7), 961–979. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854818799811

- Pascoe, E. A., & Richman, L. S. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 531–554. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016059

- Pedrelli, P., Shapero, B., Archibald, A., & Dale, C. (2016). Alcohol use and depression during adolescence and young adulthood: A summary and interpretation of mixed findings. Current Addiction Reports, 3(1), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-016-0084-0

- Reblin, M., & Uchino, B. N. (2008). Social and emotional support and its implication for health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 21(2), 201–205. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f3ad89

- Rice, E., & Yoshioka-Maxwell, A. (2015). Social network analysis as a toolkit for the science of social work. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research, 6(3), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1086/682723

- Rivest, M.-P., & Moreau, N. (2015). Between emancipatory practice and disciplinary interventions: Empowerment and contemporary social normativity. British Journal of Social Work, 45(6), 1855–1870. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcu017

- Shahar, G., & Henrich, C. C. (2016). Perceived family social support buffers against the effects of exposure to rocket attacks on adolescent depression, aggression, and severe violence. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(1), 163–168. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000179

- Skogen, J. C., Sivertsen, B., Lundervold, A. J., Stormark, K. M., Jakobsen, R., & Hysing, M. (2014). Alcohol and drug use among adolescents: And the co-occurrence of mental health problems. Ung@hordaland, a population-based study. BMJ Open, 4(9), Article e005357. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005357

- Sloper, P. (2004). Facilitators and barriers for co-ordinated multi-agency services. Child: Care, Health and Development, 30(6), 571–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00468.x

- Statistisk Sentralbyrå. (2012, March 5). Mer aktive med tillit til andre. Statistisk Sentralbyrå. https://www.ssb.no/kultur-og-fritid/artikler-og-publikasjoner/mer-aktive-med-tillit-til-andre–87121.

- Straiton, M. L., Aambø, A. K., & Johansen, R. (2019). Perceived discrimination, health and mental health among immigrants in Norway: The role of moderating factors. BMC Public Health, 19(1), Article 325. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6649-9

- Strandheim, A., Holmen, T. L., Coombes, L., & Bentzen, N. (2009). Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health 3 young people, 13–19 years in North-Trøndelag, Norway: The young-HUNT study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 3(1), Article 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-3-18

- Szaflarski, M., & Bauldry, S. (2019). Advances in medical sociology. Advances in Medical Sociology, 19, 173–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1057-629020190000019009

- Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M., McClelland, G. M., Dulcan, M. K., & Mericle, A. A. (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(12), 1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1133

- Thoits, P. A. (2011). Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 52(2), 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510395592

- Thompson, A., Baquero, M., English, D., Calvo, M., Martin-Howard, S., Rowell-Cunsolo, T., Garretson, M., & Brahmbhatt, D. (2021). Associations between experiences of police contact and discrimination by the police and courts and health outcomes in a representative sample of adults in New York city. Journal of Urban Health, 98(6), 727–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00583-6

- Topp, C. W., Østergaard, S. D., Søndergaard, S., & Bech, P. (2015). The WHO-5 well-being index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 84(3), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1159/000376585

- Van Lange, P. A. M. (2015). Generalized trust. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(1), 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414552473

- von dem Knesebeck, O., & Geyer, S. (2007). Emotional support, education and self-rated health in 22 European countries. BMC Public Health, 7(1), Article 272. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-272

- Wareham, J., & Boots, D. P. (2012). The link between mental health problems and youth violence in adolescence. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(8), 1003–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854812439290

- Wells, E. A., Kristman-Valente, A. N., Peavy, K. M., & Jackson, T. R. (2013). Social workers and delivery of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for substance use disorders. Social Work in Public Health, 28, 279–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2013.759033

- Zhao, J., Chapman, E., Houghton, S., & Lawrence, D. (2022). Perceived discrimination as a threat to the mental health of Chinese international students in Australia. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.726614.

- Ziersch, A., Due, C., & Walsh, M. (2020). Discrimination: A health hazard for people from refugee and asylum-seeking backgrounds resettled in Australia. BMC Public Health, 20(1), Article 108. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-8068-3

- Zolopa, C., Burack, J. A., O’Connor, R. M., Corran, C., Lai, J., Bomfim, E., DeGrace, S., Dumont, J., Larney, S., & Wendt, D. C. (2022). Changes in youth mental health, psychological wellbeing, and substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic: A rapid review. Adolescent Research Review, 7(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-022-00185-6