ABSTRACT

This article presents findings from a scoping review of the published literature on independent experts in care order proceedings. The aim of the review is to inform the researchers, policymakers and practitioners working at the crossroads of social work, psychology and law of the current knowledge base and gaps in the research. The review includes 43 articles from which we extracted and analysed content related to how and why independent experts are used in care order proceedings, challenges and advantages of using such experts, and the consequences of using these experts for the family. The results revealed several challenges relating to the use of independent experts and the way in which this work is organised, and their methods. The findings indicate that some challenges are caused by the various professions that are involved in these proceedings having insufficient knowledge and understanding of each other’s mandates for the work they carry out in this field. The review recommends further research on the expert reports’ impact on children and families, and how they affect the court’s decisions.

ABSTRAKT

Denne artikkelen presenterer funn fra en scoping review hvor tema er uavhengige eksperter i barnevernets omsorgsovertakelser. Målet med litteraturgjennomgangen er å gi forskere, beslutningstakere og praktikere som jobber i krysningspunktet mellom barnevern, psykologi og juss en oppdatert kunnskapsoversikt og gi anbefalinger for videre forskning. Oppsummeringen inkluderer 43 artikler hvor innholdet er sortert og analysert i lys av hvordan og hvorfor uavhengige eksperter blir brukt i omsorgssaker, utfordringer og fordeler ved bruken av slike eksperter og hvilke konsekvenser det kan få for familien. Resultatene viser flere utfordringer knytt til bruken av uavhengige eksperter, metodene deres og måten dette arbeidet er organisert på. Funnene indikerer at noen av utfordringene oppstår når de ulike profesjonene som inngår i omsorgsovertakelser har utilstrekkelig kjennskap og forståelse av hverandres mandat og arbeidet de utfører. Anbefalinger for videre forskning er å utforske hvilken betydning rapporter fra uavhengige eksperter har for barn og familier og hvilken innflytelse rapportene har på rettens avgjørelser

Background

The work of child welfare services (CWS) includes protecting children from harm, and in severe cases, the last resort is to remove the child from their parents. Decisions to remove children from their birth family are mainly made in civil courts or tribunals of lay members (Hultman et al., Citation2020). These processes are often called care proceedings. In care proceedings, an independent expert who has assessed the care provided by the parents and the child’s developmental needs is commonly called as a witness. The experts carry out assessments and deliver a report according to a mandate (Melinder, Koch, et al., Citation2021). Their recommendation will function as a supplement to the CWS assessment, which jointly forms the basis for the decision. However, the profession of these experts vary (Augusti et al., Citation2017; Masson et al., Citation2019), as does the actual use of the independent experts, specifically in regard to how the interaction between the expert, the CWS and the court is organised (Dickens et al., Citation2017; Hultman et al., Citation2020; Skivenes & Tonheim, Citation2016). The research has shown that there are various intentions behind using an independent expert, and that there are several different ways in which this has been implemented (Hinton, Citation2019; Melinder, Koch, et al., Citation2021; Robertson & Broadhurst, Citation2019; Skivenes & Tonheim, Citation2019). A cross-country comparative study shows that requests for expert reports among CWS professionals differ in their intentions and outcomes (Dickens et al., Citation2017).

In care proceedings, independent experts’ assessments are made in order to influence the care order decisions, as the intention of employing such an expert assessment is to improve the quality of care that will be provided on the basis of what decision is made. However, there is an ongoing debate in the literature regarding the function of these independent experts and the contributions of their reports. A number of reports have documented that some expert reports in Norway are of a low quality, specifically in consideration of the assessments being made, which may have critical consequences for the children involved (Ministry of Children and Equality, Citation2006; Citation2017; Norwegian Board of Health Supervision, Citation2019). In a vignette study on independent experts in Norway, Læret (Citation2017) found that these experts vary considerably in their recommendations of placing the child in foster care, even when they considered the risk of abuse and neglect to be the same. Others have raised questions about how and the extent to which the experts’ evidence should be weighted in court (Bala et al., Citation2017; Richman, Citation2005). According to Dickens et al. (Citation2017), social workers report that commissioning an expert report results in delays in the care order decision-making process, exemplifying their concerns about the time spent on assessment in high-risk cases. Moreover, a research report shows that in England, reforms reduced the length and cost of care proceedings which then resulted in a reduction in using independent experts and possibly affected the outcome for the children involved (Masson et al., Citation2019). These findings thus show that the use of an independent expert affects the organisation and quality of the care proceedings in complex ways, resulting in challenges that must be acknowledged.

The research on independent experts in care proceedings includes at least three fields of practice: social work, law and psychology, all of which comprise their own field of research and policy. Historically, there have been debates on the relationships between these disciplines. King (Citation1991) claims welfare (social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists) and law (courts, judges) exist and work within very different discourses. The legal discourse aims to make simple binary distinctions – e.g. proven/not proven, while the welfare discourses deal with probabilities more than certainties. King argues that when welfare knowledge shall inform the legal system, this ‘will inevitably result in the domination of law and the ‘enslavement’ of child-welfare knowledge to serve institutional legal objectives’ (King, Citation1991, p. 319). Research focusing on the junction of the three professions may be fragmented and skewed due to their differences in nature and the few common intersections these fields have in regard to discussions and knowledge-sharing. Regular overviews of the literature would be beneficial, namely so that we can gain knowledge of what we do and do not know about the field, and with that, develop the knowledge base and move the research forward. A scoping review is commonly used to provide a comprehensive summary of a topic, so as to identify the key concepts, sources of evidence, and gaps in the research (Peters et al., Citation2021). According to a preliminary search for reviews of independent experts in care proceedings, this has yet to be done. Thus, this study sought to compile the comprehensive knowledge of the use of independent experts in care proceedings in order to systematically map out the existing knowledge and identify research gaps in the literature, specifically focusing on the purpose of using an expert. Given that the purpose is to gain a better foundation for making such important decisions, the objectives of this study are to ensure a review of the possible challenges and advantages when it comes to improving the basis on which the decisions in care proceedings are made.

Objectives

The scoping review explores how the use of independent experts contributes to the decision-making process in care proceedings. The following research objectives were developed:

Summarise how and why experts are utilised in care proceedings,

Identify any challenges that raise concerns about the practice of using independent experts in care proceedings,

Identify what the advantages of using experts are so as to improve the foundation of the decision-making in care proceedings that choose to use experts,

Identify what has been reported as consequences for the families involved by using an independent expert.

Procedure

A protocol was produced using the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis for scoping reviews (Peters et al., Citation2020). The final protocol was registered with the Open Science Framework on 14 September 2021 (https://osf.io/yf9tp/).

Eligibility criteria

To be included in this study, the articles had to be: published in a peer-reviewed journal; describe original research on independent experts in care proceeding or the preparation for such; or be a scientific paper that discusses the use of independent experts, for which the setting must be within the CWS. The articles selected for the study had to be written in English or a Scandinavian language. Papers were excluded if they: discussed independent experts generally, that is, not within the child welfare services; focused on parental conflict in child custody cases; revolved around child abuse cases where the focus is on evidence in criminal court; used juvenile court cases that were not about care orders; and were guidelines/framework for experts.

Method

The search strategies were developed during January and February 2021 by author RG and two librarians, and then refined by a pilot search and discussions with the co-authors. The pilot search was conducted in the following databases: Scopus, Cinahl and PsycINFO. The search strategy was peer-reviewed by OsloMet Library, according to Peer Review of Electronic Search Strategies (PRESS) (Sampson et al., Citation2008). The final main search was conducted on 3 June 2022 in the following databases: PsychINFO, Web of Science, SocINDEX, Cinahl, Scopus, Academic Search Elite, ASSIA, ProQuest Dissertation. In addition, a hand-search was conducted, in which we searched for keywords in the native language in each database, for the following journals: Social Care online, Nordic Social Work Research, the Norwegian data bases Oria and Norart, as well as the Swedish data bases SwePub and DIVA. The final search strategy for Scopus is presented in Appendix I.

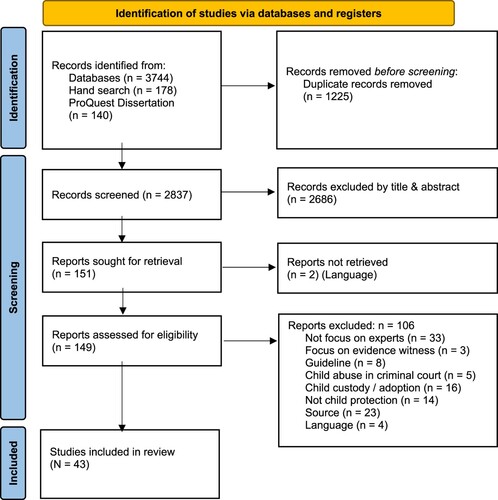

The screening of titles and abstracts was conducted in Rayyan, a web-based tool designed for systematic reviews (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). Screening was done in pairs by the authors and screened independently. During the screening of abstracts, the authors met on two occasions to discuss the inclusion and exclusion of papers. The authors screened full text articles where 20 per cent of the articles were screened by pairs independently and discussed before then screening the remaining papers. If a disagreement arose, a third reviewer would decide on whether an article was to be included or excluded. The process is presented in the figure below ().

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart (Page et al., Citation2021).

Analysis

A data-charting form was developed by the reviewer team and piloted by all authors (Appendix II). The included articles were charted by the reviewers independently. Data was charted based on aims, method, country, and on how and why experts were applied to the care proceedings, as well as the challenges and benefits of using an expert in regard to the court case itself, and the advantages and disadvantages of using experts for the family. The charted data was synthesised by a thematic content analysis in which all of the authors discussed and revised the themes (Anderson, Citation2007).

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

From the 2837 records screened, 43 articles were included in the analysis (Appendix III). Of those 43 articles, 17 were theoretical papers and the remaining 26 studies comprise collected data (n = 7) or used existing data, such as case documents (n = 5), and case studies (n = 4). Eight articles utilised a mixed method approach, and one used a scoping review and one a chart review. The majority of the articles included were from the UK (n = 16) and the US (n = 11). Australia was represented by five articles, Norway four and Canada two. Three articles were from multiple countries and Germany and Israel were the origin in one article each.

How and why experts are used

The results show that how experts are used and why the experts were appointed varied from country to country. An independent expert was commonly appointed by the court for a full assessment of family functionality (Bala et al., Citation2017; Brophy et al., Citation2003; Brown & Dean, Citation2002; Budd et al., Citation2006; Sibert et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, in some instances, an expert was appointed by the CWS to prepare for court, where the CWS brings the expert evidence to court (Melinder, Koch, et al., Citation2021; Tilbury, Citation2019). The most common reasons for using an expert mentioned in the literature were: to inform the court of their assessments (Brophy et al., Citation2003; Brown & Dean, Citation2002; Dale, Citation2010; Haugli & Nordhelle, Citation2014; Johnson, Citation1999; Masson et al., Citation2019; McKenzie & Cossar, Citation2013; Mulcahy et al., Citation2014); to investigate evidence of abuse (Harnett, Citation1995; Lennings, Citation2002; Levine & Battistoni, Citation1991; Mian et al., Citation2009; Milchman, Citation1995; Skellern, Citation2008; Skellern & Donald, Citation2012); to inform the court about the learning disability of the parent in particular (Fialkov, Citation1988); to inform the court about the infant’s mental health (Pruett, Citation1992); or to give information regarding culture or ethnicity (Limb et al., Citation2004).

The most common profession of the expert mentioned was psychologist and psychiatrist, followed by paediatricians, social workers, and mental health workers, as shown in Appendix III. In two articles, an alternative organisation was used as the independent expert. In these articles, a clinic with various different professionals was commissioned to assess the family. A few articles included experts consisting of the child(ren)’s guardian, forensic scientists, general practitioners and medical practitioners.

Challenges of using an expert

The analysis identified four themes that highlight the concerns about the use of independent experts in care order cases. These four themes may individually or together reduce the quality of the experts’ contribution and, through this, impair the usefulness of their contributions in regard to the decision then made in child protection cases.

First, the analysis identified the professional chasm – that is, the current gap in knowledge and cooperation between the users of the experts’ reports and the experts themselves – as problematic. The different professionals involved in this field of work have insufficient knowledge of each other’s work, which may cause issues regarding the quality of the foundation on which the decision is built. Findings showed that social workers may lack the skills to request and use psychological evaluations and to evaluate the quality of those evaluations (Kayser & Lyon, Citation2000). In addition, judges may also lack the training to adequately appraise the evidence provided by the experts (Beckett et al., Citation2007), which corroborates with Tilbury (Citation2019, p. 401) who highlighted that the court’s decision-making would benefit from enhanced ‘legal and judicial capacity’ to appraise expert evidence. On the other hand, Bala et al. (Citation2017) and Mian et al. (Citation2009) claimed some expert reports lack relevant information (Mian et al., Citation2009) and fail to elaborate on the limitations and challenges related to the use of their evidence (Bala et al., Citation2017). Hence, the difficulties in using or appraising the reports could be reinforced by how the experts explain their assessment and conclusions. Further, Levine & Battistoni (Citation1991), Beckett et al. (Citation2007) and Kayser and Lyon (Citation2000) claimed the courts seem to take for granted that the experts’ evidence is in accordance with scientific evidence of good quality and therefore trustworthy. However, the court may lack the skill to properly evaluate the quality of the report and hence base their judgement on their belief in the medical and psychological profession’s scientific knowledge generally, rather than the work the expert has undertaken in the completion of an individual report. Beckett et al. (Citation2007) claimed that judges value experts’ evidence to a greater extent than the social workers’ reports, and have a tendency to believe that a ‘right’ answer will emerge when provided with increasingly more information. However, such processes may instead cause delays in the care proceedings, with the court requiring such assessments by experts during the process of the care proceedings (Beckett et al., Citation2007).

Another challenge identified revolves around the methods used by the experts. The methods and instruments used by experts in child protection assessments are plentiful but divergent. Several of the included articles provided critiques of the expert’s methods, implying a threat to the quality of the care order decision. Lennings (Citation2002), Budd et al. (Citation2006), Tilbury (Citation2019) and Skellern and Donald (Citation2012) emphasised that there is a lack of systems in place to provide a gold standard for such expert reports in child protection. There is no consensus on what variables should be assessed and how, which might reduce the quality of the experts’ assessments. Others described procedures that the experts use in their work to be ethically and/or methodologically problematic (Budd, Citation2005; Kollinsky et al., Citation2013; Levine & Battistoni, Citation1991; Pruett, Citation1992). Levine & Battistoni (Citation1991) claimed that the interviews used by experts in child abuse cases are intrusive and suggestive, which may also be methodologically problematic and ethically challenging at best, causing the child to disclose false allegations at worst. In addition, Budd (Citation2005), Kayser and Lyon (Citation2000) and Kollinsky et al. (Citation2013) claimed that experts can be experts in clinical work but lack the necessary competence to assess such cases for care orders. They argued that clinical psychologists are not trained for forensic evaluations and may fail to follow forensic guidelines. Budd (Citation2005) reported that psychological instruments are generally not designed for assessing parenting capacity and are not empirically tested regarding their validity in a child protection context. The few standardised observation systems of parent–child interaction behaviour are limited in their applicability and require substantial training for reliable use (Budd, Citation2005). According to Pruett (Citation1992) experts use methods in forensic investigations similar to those clinicians use in clinical work. However, the work is presented for the resolution of legal disputes, not for clinical interventions. This may be problematic as clinical work has the intention of helping, treating and supporting parents, while forensic work intends to provide a neutral description of parental functioning for a specific child. Altogether, this may result in poor or inappropriate recommendations for treatment or decisions for the clients.

A third challenge identified is that experts may lack contextual information about the families in child welfare cases. Limited contextual knowledge of the families causes a restricted and less holistic understanding of the child’s care and needs. Kayser and Lyon (Citation2000) reported that experts may lack familiarity with the complexities and constraints of the child welfare system, resulting in the expert not using the extensive, ecological assessment data that social workers typically use. A dominating view in the included articles is that expert assessments are based on evaluations made in a short period of time and on limited information and thus may fail to bring forward the complexity and nuances within the child welfare case (Beckett et al., Citation2007; Beckett & McKeigue, Citation2003; Booth & Booth, Citation2004; Budd et al., Citation2006; Kayser & Lyon, Citation2000; Tilbury, Citation2019). Budd et al.’s studies from both Citation2001 and Citation2006 found that evaluations of the parents were typically completed in single sessions within an office setting, without any home observations, rarely using collateral sources of information and often neglecting to state any information about the parent’s relationship with the child or their parental qualities. While Tilbury (Citation2019) reported that the judicial officers believed the expert reports to be the most comprehensive assessments available to the court. However, the quality of the expert assessment was criticised for lacking the depth and analysis of complex issues such as trauma, abuse and cultural matters (Tilbury, Citation2019). Beckett et al. (Citation2007) reported that social workers claimed that expert evidence was partly based on information gathered in ‘laboratory’ settings, such as the expert’s office or a family centre, where parents managed to conduct good enough parenting. The combination of an artificial assessment setting without taking the families’ histories into account may result in inferior decisions being made (Beckett et al., Citation2007). Brophy et al. (Citation2003) described that expert reports lack relevant information about ethnicity and culture, and that the expert reports should include a differentiation between culture-bound experiences and mental illness, with the experts having a better understanding of the significance of cultural traditions (Brophy et al., Citation2003; Wills & Norris, Citation2010).

The last identified challenge was that the professional perspectives had the potential to limit the scope of an assessment where certain factors could cause the expert to overlook essential considerations in a care order assessment, such as: the experts’ theoretical perspectives (Johnson, Citation1999; Melinder, van der Hagen, et al., Citation2021); the use of social science research (Robertson & Broadhurst, Citation2019; Sibert et al., Citation2007); and expert prejudices (Booth & Booth, Citation2004). Johnson’s study (Citation1999) illustrated how the theoretical perspective of the expert can limit their ability to assess the situation as a whole, criticising their focus of the so-called psychological parent theory, as it places too much emphasis on the assessment of the psychological bonding between the child and their day-to-day carer, which thus overlooks the other risks and developmental needs of the child. Corroborating with Johnson (Citation1999), Melinder et al. (Citation2021b) argued that the position of the biological parents in relation to the rights of the child has been weakened in terms of their rights to family life and integrity, namely because of the psychologists’ use of attachment theory and a trauma approach. Booth and Booth (Citation2004) brought to light in their discussion that experts’ prejudices may influence their assessment by showcasing that parents with learning difficulties are at high risk of having their parental rights terminated due to a widespread presumption that they may be incompetent in providing the necessary care. Booth and Booth (Citation2004) further claimed that the expert witnesses in these cases are instructed to find flaws in the parental practice, and thus trawl for evidence that supports such inadequate parenting. Robertson and Broadhurst (Citation2019) pointed to the nature of social science being contested, as different researchers claim different findings, and that research can be seen as politically motivated or aligned too. Robertson and Broadhurst (Citation2019) and Sibert et al. (Citation2007) both highlighted that social science is continuously changing and may not be conclusive, and that judges and lawyers are neither trained in interpreting research evidence nor are they trained on how to apply the research in specific cases. They concluded that there is a potential for the misuse of research evidence in care proceedings (Robertson & Broadhurst, Citation2019; Sibert et al., Citation2007).

Advantages of using an expert

The analysis identified two themes that highlighted the positive contributions of the independent experts in the care proceedings. The themes uncovered here were that it was beneficial that the experts had knowledge of a specialised area that can inform the decision and that the use of experts can contribute to multi-professional work within the field of child protection.

The articles included in the review showed that the expert report is considered as a positive contribution when the experts are shown to have the required knowledge and skills, which is considered vital for ensuring a solid foundation on which a decision can be made (Bala et al., Citation2017; Brown & Dean, Citation2002; Kollinsky et al., Citation2013; Pruett, Citation1992; Tilbury, Citation2019). The experts’ contribution is mainly to inform the court about parent assessment or evaluation made during the care proceedings. Indeed, Bala et al. (Citation2017) claimed that, based on experiences from lawyers and judges, the assessments made by these experts can play a significant role in facilitating settlements. This indicates that the use of experts may have diverse impacts depending on the context. Besides providing assessments of parental functioning, an important expert contribution was to inform the court about the children. Pruett (Citation1992) discussed the use of experts to testify about the mental health of infants. According to Pruett, an infant mental health expert can communicate to the court about the infants’ needs and development – something that requires a particular understanding of a specific expertise, and which can thus provide guidance about the concepts of infant mental health. Budd et al. (Citation2006) also pointed out that clinical psychologists can provide important clinical information too, such as parenting problems, communicative skills and behaviours in need of change. Similarly, Tilbury (Citation2019) emphasised that the separate representative is particularly valuable in ensuring that the child’s view and wishes are promoted in court. Separate representatives are to be understood as independent experts on child development and their role is to talk with the child and promote the child’s view and opinions in the legal proceedings (Tilbury, Citation2019).

The second theme identified as an advantage of using experts was that it could enhance the multi-professional work within the proceedings, which was considered a positive contribution in ensuring a comprehensive assessment of the family. McKenzie and Cossar (Citation2013) claimed that, by including clinical psychologists as experts for care proceedings, this improved the multi-agency work within child protection, as it meant that the different agencies dedicated time to work with other agencies in order to fully assess the family. Similarly, some participants in Skivenes and Tonheim’s (Citation2019) study suggested that psychologists and social workers should take part in the decision-making process to complement each other professionally and thus bring about an improvement to the decision-making process in care proceedings. A few articles included a multi-professional court clinic assessment rather than opting for an independent expert report, which was recognised as beneficial (Brown & Dean, Citation2002; Budd et al., Citation2006). Brown and Dean (Citation2002) argued that a court clinic assessment prior to the care proceeding would facilitate the therapeutic process that follows on from the care proceedings, and could provide further information that makes it easier to discuss recommendations. Budd et al. (Citation2006) found that a court clinic was successful in providing timely, relevant clinical information, reflecting recommended forensic evaluation guidelines. The clinics consisted of social workers, psychologists, psychiatrists, lawyers, and support personnel – a different but successful structure of the function of the independent expert.

Consequences for the family of using an expert

Overall, there was a limited number of articles focusing on the consequences for the families in care proceedings. Across the included articles, three themes were identified. The first was that the use of experts prolonged the care proceedings and thus resulted in negative consequences for the families, and particularly the children (Bala et al., Citation2017; Beckett & McKeigue, Citation2003; Masson et al., Citation2019). Beckett and McKeigue (Citation2003) claimed that the lengthy care proceedings drastically reduce the options for a child as the rate of adoption among older children is much lower than their younger counterparts, and will thus increase the risk of placement breakdown, meaning the child must return to foster care/the children’s home if a potential adoption/foster care opportunity is unsuccessful. Beckett and McKeigue (Citation2003) also pinpointed multiple assessments of the child as negative for the child and claimed that the use of experts increases the numbers of assessments per child. Masson et al. (Citation2019) found that a reduction in the amount of time used on care proceeding, namely by setting a time limit and restricting the use of expert evidence, may have improved outcomes for the children involved: adoption happened earlier, there was a reduced number of placements and an increase in supervision orders and special guardianship orders. The children who were placed back with their parents spent less time in foster care, which also reduced costs for local authorities (Masson et al., Citation2019).

The second theme identified is that the assessment process is intrusive to families, both for the parents and children (Bala et al., Citation2017; Booth & Booth, Citation2004; Budd et al., Citation2006). The articles emphasised how stressful the care proceeding can be for the families and that being assessed in this situation may be demanding. However, none of the articles used families as informants in their research.

The third theme highlighted how the families may be affected by the clinical psychologists’ conflicting roles when carrying out both forensic and clinical work with the families themselves (McKenzie & Cossar, Citation2013; Pruett, Citation1992). McKenzie and Cossar (Citation2013) noted that this conflict may cause a disruption to the existing therapeutic relationship between the family and a therapist, if the therapist is brought into the child protection work. Similarly, Pruett (Citation1992) claimed one cannot serve as an expert in court for a child that also is their client. Consequently, these conflicting roles may heighten the intrusive nature of a care proceeding, given that the families would need to go through another assessment or have their relationship with their therapist disrupted.

Discussion

The aim of the scoping review was to summarise the findings of the available literature on independent experts in care proceedings, specifically in regard to: how and why independent experts are appointed; the challenges and advantages; the consequences for the families; and to identify any knowledge gaps. The results reveal a problematic chasm between the experts and the users of the expert reports – being the judges, legal practitioners in CWS and case/social workers, and a substantial critique towards the methods and the use of limited perspectives by the experts. The advantages identified were that the experts had the specific knowledge and skills inform the decision of the care proceedings, and that the use of experts contributed to a multi-disciplinary perspective. There were few articles that focused on the consequences for the families. By mapping out the literature about these independent experts in care proceedings, this review shows that there are areas that need to be addressed and important research gaps to fill. Here, we will discuss some aspects regarding the use of different professions as the expert in care proceedings; the challenges regarding the experts’ methods and perspectives; and recommendations for future research based on our review.

Our review shows that the profession of the independent expert may differ depending on the context of the care proceeding, despite the fact that the purpose of the experts is reported to be similar across the material we studied. The findings reveal that the most common profession of the expert is that of a psychologist, specifically when the mandate is to evaluate the parents and children. Paediatricians are reported to be used as experts when there is a need to examine the children in the event that abuse or injury is suspected to have occurred (Mian et al., Citation2009; Sibert et al., Citation2007; Skellern, Citation2008; Skellern & Donald, Citation2012). While social workers’ expertise is described as insufficient by the court in some contexts (Beckett & McKeigue, Citation2003; Skivenes & Tonheim, Citation2016), an independent social worker is commonly called in as an expert in the UK, the US and Australia (Dale, Citation2010; Masson et al., Citation2019; Tilbury, Citation2019). Our findings seem to confirm that the court’s attention tends to be on the forensic side of the proceedings, which causes a general undermining of the child protection expertise provided by social workers (Sheehan & Borowski, Citation2014). However, the social work professionals may be considered experts when operating outside the caseworker setting. Although our review shows that psychologists are commonly considered as an expert in care proceedings – emphasising the mental health perspective as a key component in child care – our overall findings show that multiple professions within health and social care have considerable influence on such care proceedings. Indeed, our findings suggest that there is a problematic chasm between the various professions involved, meaning that there is currently a disconnect in the way in which they work and approach such work, while some articles promote a multi-professional approach, stating that this could help in assessing the complex legal standard of ‘the best interest of the child’ (McKenzie & Cossar, Citation2013; Robertson & Broadhurst, Citation2019; Sibert et al., Citation2007; Skivenes & Tonheim, Citation2019). A multi-professional approach may contribute to a reduction in the disconnect between social workers and the experts (Frost, Citation2017), but it may then also jeopardise the experts’ role regarding the necessary independence required. In addition to this, such a multi-professional approach could be further enhanced by improving the judges’ understanding of the experts’ methods, for example by introducing mandatory training (Burns et al., Citation2016).

Overall, the challenges identified mainly address the practical and theoretical work of the experts. Our review shows that a lack of a gold standard for the frameworks of forensic work within the field of child protection may threaten the quality of the experts’ reports. However, deciding on a standardised framework may still fail to recognise that social science is ambiguous and is in a state of continuously developing (Bhattacherjee, Citation2012; Rathus, Citation2014), meaning that theoretical frameworks will and do change over time. Experts are expected to synthesise the research, giving most weight to studies that use a sound methodology, in order for them to give an evidence-based opinion in court, and to avoid the inclusion of personal experience and their own values and beliefs about the parents’ parenting capacity and the children’s needs. However, other factors, such as their background, attitudes (Page & Morrison, Citation2018; Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1974) and the theoretical perspective (Stridbeck, Citation2020) used by the professional conducting the assessments will inevitably influence the interpretation of those assessments. Theoretical perspectives develop over time and the recognition and use of certain schools of thought tend to rise and fall among the professionals. One relevant example is noted by Melinder et al. (Citation2021b) who argue that the position of the biological parents has, over the last decade, been weakened due to the increased focus on attachment and trauma-based approaches in care proceedings. Extensive research shows that insecure/disorganised attachment may be caused by neglect and abuse (Baer & Martinez, Citation2006), but is not necessarily the only cause (Forslund et al., Citation2022). However, if the experts’ opinions are based on their reasoning that disorganised attachment is solely caused by abuse and neglect, there is a higher risk of the child being placed out-of-home. Our findings show that the methods used by experts have limitations and that there is a need for the expert to elaborate on the limitations of the methods they have used for assessments and to provide alternative perspectives on each care proceeding case. On the other hand, the judges, searching for unambiguous answers (King, Citation1991), seem to rely on the experts’ interpretations of social science, seeing it as impartial knowledge, even though research shows that impartiality in expert witnesses is hard to accomplish (Dror et al., Citation2015). Our findings indicate that the users of the reports may have unrealistic expectations of the assessments, suggesting that the experts themselves may fail to recognise the level to which the judges and social workers will understand their assessment.

Recommendations for research

Overall, the scoping review identified a lack of research in the field of expert reports within care proceedings, namely in the following two areas: research from the parents’ and child’s perspectives, and how the expert’s report influences the decision made by the court. Few articles are concerned with how families experience the inclusion of independent experts in care proceedings and none included families as informants in their studies. The increasing emphasis on child participation within child protection work (van Bijleveld et al., Citation2015) should also be reflected in the future research carried out on independent experts in care proceedings.

As the purpose of an independent expert is to inform the court of evidence-based opinions so as to improve the basis on which the decision is made, it may come as a surprise that none of the articles included in this review have evaluated the impact of expert reports on the outcome of the decision. The methods used in the articles were all mainly theoretical and qualitative, and thus a lack of quantitative research was identified. Overall, there were few papers that focused on a cost analysis of using an independent expert in care proceeding either. We conclude then that this scoping review of the existing literature can inform the field of research that it must focus on the experiences of the parents and children when it comes to appointing an independent expert in care proceedings, as well as the outcome of the use of such experts.

Limitations

The aim of the study was to review the current literature at the crossroad between social work, law and psychology, with the use of the scoping review methodology. Consequently, the scope of the review was broad and the field of research vast, leading to the inclusion of a wide array of databases. Nonetheless, there might have been some papers covering the topic of independent experts in care proceedings that were undetected. Another limitation is that, as a scoping review, the quality and rigour of the studies was not assessed. Yet, by using a scoping review methodology, we were able to include a range of study designs, which may be valuable in a fragmented and important field of research.

Conclusion

Overall, the literature revealed that challenges exist regarding an insufficient knowledge between the judges, the experts and the social workers, and concerns with some aspects of the experts’ work with the assessments. Although there were few identified advantages reported in our review, there was an overall consistency in reporting that the purpose of the independent expert was that of the experts’ expertise in specialised knowledge, and that this was being fulfilled. In addition, our findings suggests that the experts positively contribute to enhancing the multi-professional work in child protection.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (81.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rakel Aasheim Greve

Rakel Aasheim Greve is a PhD student in the Department of Welfare and Participation at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Norway. Her doctoral research is in child welfare services, with a focus on the use of independent experts in Norway (see project webpage: hvl.no/expert).

Tone Jørgensen

Tone Jørgensen is PhD in sociology and is an associate professor in the Department of Welfare and Participation at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Norway. Her field of research is within child welfare and child protection services, with a special focus on decision-making processes, the use of professional knowledge, and children's participation.

Øivin Christiansen

Øivin Christiansen is a social worker with a PhD in Psychosocial Science. He works as a Senior Researcher at Regional Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health and Child Welfare West, NORCE Norwegian Research Centre, Bergen, Norway. He has broad experiences from child welfare practice, education, and research. His research interests include child welfare decision-making, family support, foster care, user participation, and services to marginalised families and children.

Vibeke Samsonsen

Vibeke Samsonsen is PhD in Social Work and is an associate professor in the Department of Welfare and Participation at the Western University of Applied Sciences, Norway. Her field of research is child protection decision-making and high-conflict families.

Hanne Cecilie Braarud

Hanne C. Braarud is Dr.psychol. and Professor II at the Western Norway University of Applied Sciences, Norway, and Research Professor at the Regional Centre for Child and Adolescent Mental Health and Child Welfare West, NORCE. She has long experience from research, teaching and education. Her field of research expands on infant mental health, experimental observation studies of parent-infant interaction, prospective cohort studies evaluating implementation of interventions in child welfare service and public health services.

References

- Anderson, R. (2007). Thematic content analysis (TCA). Descriptive Presentation of Qualitative Data, 1–4. http://rosemarieanderson.com/wpcontent/uploads/2014/08/ThematicContentAnalysis.pdf

- Augusti, E.-M., Bernt, C., & Melinder, A. (2017). Kvalitetssikring av sakkyndighetsarbeid–en gjennomgang av vurderingsprosesser i Barnesakkyndig kommisjon, fylkesnemnder og domstoler. Tidsskrift for familierett, arverett og barnevernrettslige spørsmål, 15(4), 265–289. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.0809-9553-2017-04-02

- Baer, J. C., & Martinez, C. D. (2006). Child maltreatment and insecure attachment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 24(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830600821231

- Bala, N., Birnbaum, R., & Watt, C. (2017). Addressing controversies about experts in disputes over children. Canadian Journal of Family Law, 30(1), 71–128.

- Beckett, C., & McKeigue, B. (2003). Children in limbo: Cases where court decisions have taken two years or more. Adoption & Fostering, 27(3), 31–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/030857590302700307

- Beckett, C., McKeigue, B., & Taylor, H. (2007). Coming to conclusions: Social workers’ perceptions of the decision-making process in care proceedings. Child and Family Social Work, 12(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00437.x

- Bhattacherjee, A. (2012). Social science research: Principles, methods, and practices. Textbooks Collection. 3. http://scholarcommons.usf.eda/oa_textbooks/3

- Booth, W., & Booth, T. (2004). A family at risk: Multiple perspectives on parenting and child protection. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 32(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2004.00263.x

- Brophy, J., Jhutti-Johal, J., & Owen, C. (2003). Assessing and documenting child Ill-treatment in ethnic minority households. Family Law, 756–764.

- Brown, P., & Dean, S. (2002). Assessment as an intervention in the child and family forensic setting. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice, 33(3), 289–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.33.3.289

- Budd, K. S. (2005). Assessing parenting capacity in a child welfare context. Children and Youth Services Review, 27(4), 429–444. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.11.008

- Budd, K. S., Felix, E. D., Sweet, S. C., Saul, A., & Carleton, R. A. (2006). Evaluating parents in child protection decisions: An innovative court-based clinic model. Professional Psychology: Research & Practice, 37(6), 666–675. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.37.6.666

- Budd, K. S., Poindexter, L. M., Felix, E. D., & Naik-Polan, A. T. (2001). Clinical assessment of parents in child protection cases: An empirical analysis. Law and Human Behavior, 25(1), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005696026973

- Burns, K., Dioso-Villa, R., & Rathus, Z. (2016). Judicial decision-making and ‘outside’ extra-legal knowledge: breaking down silos. Griffith Law Review, 25(3), 283–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2016.1264100

- Dale, P. (2010). Child protection risk assessment: An independent social work expert witness perspective. Family Law, 40, 628–635.

- Dickens, J., Berrick, J., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (2017). Social workers and independent experts in child protection decision making: Messages from an intercountry comparative study. British Journal of Social Work, 47(4), 1024–1042. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw064

- Dror, I. E., McCormack, B. M., & Epstein, J. (2015). Cognitive bias and its impact on expert witnesses and the court. The Judges' Journal, 54(4), 8–14.

- Fialkov, M. J. (1988). Fostering permanency of children in out-of-home care: Psycho-legal aspects. Bulletin of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 16(4), 343–357.

- Forslund, T., Granqvist, P., van Ijzendoorn, M. H., Sagi-Schwartz, A., Glaser, D., Steele, M., Hammarlund, M., Schuengel, C., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Steele, H., Shaver, P. R., Lux, U., Simmonds, J., Jacobvitz, D., Groh, A. M., Bernard, K., Cyr, C., Hazen, N. L., Foster, S., … Duschinsky, R. (2022). Attachment goes to court: Child protection and custody issues. Attachment & Human Development, 24(1), 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1840762

- Frost, N. (2017). From “silo” to “network” profession – A multi-professional future for social work. Journal of Children’s Services, 12(2-3), 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-05-2017-0019

- Harnett, P. (1995). The contribution of clinical psychologists to family law proceedings in England. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 6(1), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585189508409883

- Haugli, T., & Nordhelle, G. (2014). Sikker i sin sak? Om barn, sakkyndighet og rettssikkerhet. Lov og rett, 54(2), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-3061-2014-02-04

- Hinton, M. (2019). Why the fence is the seat of reason when experts disagree. Social Epistemology, 33(2), 160–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/02691728.2019.1577512

- Hultman, E., Forkby, T., & Höjer, S. (2020). Professionalised, hybrid, and layperson models in Nordic child protection – Actors in decision-making in out of home placements. Nordic Social Work Research, 10(3), 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/2156857X.2018.1538897

- Johnson, M. B. (1999). Psychological parent theory reconsidered: The New Jersey “JC” case, part II. American Journal of Forensic Psychology, 17(2), 41–56.

- Kayser, J. A., & Lyon, M. A. (2000). Teaching social workers to use psychological assessment data. Child Welfare, 79(2), 197–222.

- King, M. (1991). Child welfare within law: The emergence of a hybrid discourse. Journal of Law and Society, 18(3), 303–322. https://doi.org/10.2307/1410197

- Kollinsky, L., Simonds, L. M., & Nixon, J. (2013). A qualitative exploration of the views and experiences of family court magistrates making decisions in care proceedings involving parents with learning disabilities. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(2), 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2012.00726.x

- Læret, O. K. (2017). Sakkyndige som «demokratiets sorte hull»? En vignettstudie av sakkyndige psykologers vurderinger av barnevernssaker. The University of Bergen.

- Lennings, C. (2002). Decision making in care and protection: The expert assessment. Australian e-Journal for the Advancement of Mental Health, 1(2), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.5172/jamh.1.2.128

- Levine, M., & Battistoni, L. (1991). Corroboration requirement in child sex abuse cases. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 9(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2370090103

- Limb, G. E., Chance, T., & Brown, E. F. (2004). An empirical examination of the Indian Child Welfare Act and its impact on cultural and familial preservation for American Indian children. Child Abuse & Neglect, 28(12), 1279–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.06.012

- Masson, J. M., Dickens, J., Garside, L. B., Bader, K. F., & Young, J. (2019). Child protection in court: outcomes for children. School of law, University of Bristol.

- McKenzie, K., & Cossar, J. (2013). The involvement of clinical psychologists in child protection work. Child Abuse Review, 22(5), 367–376. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2205

- Melinder, A., Koch, K., & Bernt, C. (2021a). Som du spør, får du svar: En gjennomgang av mandater til sakkyndige i barnevernssaker. Tidsskrift for familierett, arverett og barnevernrettslige spørsmål, 19(1), 52–76. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.0809-9553-2021-01-04

- Melinder, A., van der Hagen, M. A., & Sandberg, K. (2021b). In the best interest of the child: The Norwegian approach to child protection. International Journal on Child Maltreatment: Research, Policy and Practice, 4, 209–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-021-00078-6.

- Mian, M., Schryer, C. F., Spafford, M. M., Joosten, J., & Lingard, L. (2009). Current practice in physical child abuse forensic reports: A preliminary exploration. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33(10), 679–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.06.001

- Milchman, M. S. (1995). Child sexual abuse assessment: Issues in professional ethics. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse: Research, Treatment, & Program Innovations for Victims, Survivors, & Offenders, 4(4), 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1300/J070v04n04_06

- Ministry of Children and Equality. (2006). NOU 2006:9 Kvalitetssikring av sakkyndige rapporter i barnevernet.

- Ministry of Children and Equality. (2017). NOU 2017:12 Svikt og svik. Gjennomgang av saker hvor barn har vært utsatt for vold, seksuelle overgrep og omsorgssvikt.

- Norwegian Board of Health Supervision. (2019). Det å reise vasker øynene. Gjennomgang av 106 barnevernsaker. Helsetilsynet.

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Page, A., & Morrison, N. M. V. (2018). The effects of gender, personal trauma history and memory continuity on the believability of child sexual abuse disclosure among psychologists. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.014

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., & Moher, D. (2021). Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 134, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, JBI (Aromataris E and Munn Z, Ed.) Available from https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2021). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Implementation, 19(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/xeb.0000000000000277

- Pruett, K. D. (1992). Bearing witness for babies: The role of the expert witness. Zero to Three, 13(3), 7–11.

- Rathus, Z. (2014). The role of social science in Australian family law: Collaborator, usurper or infiltrator? Family Court Review, 52(1), 69–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12071

- Richman, K. D. (2005). Judging knowledge: The court as arbiter of social scientific knowledge and expertise in LGBT custody and adoption cases. Studies in Law, Politics & Society, 35, 3–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1059-4337(04)35001-5

- Robertson, L., & Broadhurst, K. (2019). Introducing social science evidence in family court decision-making and adjudication: Evidence from England and Wales. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 33(2), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebz002

- Sampson, M., McGowan, J., Lefebvre, C., Moher, D., & Grimshaw, J. PRESS: Peer review of electronic search strategies. Ottawa: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2008. Revised edition retrieved from FHI.no.

- Sheehan, R., & Borowski, A. (2014). Australia’s children’s courts: An assessment of the status of and challenges facing the child welfare jurisdiction in Victoria. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 36(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/09649069.2014.916079

- Sibert, J. R., Maguire, S. A., & Kemp, A. M. (2007). How good is the evidence available in child protection? Archives of Disease in Childhood, 92(2), 107–108. https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2006.110627

- Skellern, C. (2008). Medical experts and the law: Safeguarding children, the public and the profession. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 44(12), 736–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2008.01423.x

- Skellern, C., & Donald, T. (2012). Defining standards for medico-legal reports in forensic evaluation of suspicious childhood injury. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 19(5), 267–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2012.02.009

- Skivenes, M., & Tonheim, M. (2016). Improving the care order decision-making processes: Viewpoints of child welfare workers in four countries. Human Service Organizations Management, Leadership and Governance, 40(2), 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/23303131.2015.1123789

- Skivenes, M., & Tonheim, M. (2019). Improving decision-making in care order proceedings: A multi-jurisdictional study of court decision-makers’ viewpoints. Child & Family Social Work, 24(2), 173–182. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12600

- Stridbeck, U. (2020). Coerced-reactive confessions: The case of Thomas quick. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice, 20(4), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2020.1732758

- Tilbury, C. (2019). Obtaining expert evidence in child protection court proceedings. Australian Social Work, 72(4), 392–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407x.2018.1534129

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science, 185(4157), 1124–1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124

- van Bijleveld, G. G., Dedding, C. W. M., & Bunders-Aelen, J. F. G. (2015). Children’s participation within child protection. Child & Family Social Work, 20(2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12082

- Wills, C. D., & Norris, D. M. (2010). Custodial evaluations of Native American families: Implications for forensic psychiatrists. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 38(4), 540–546.