ABSTRACT

Why is it that some care order cases result in the child being removed from parental care, while in others she is not, despite the cases being similar? This paper investigates how decision-makers reason and justify different outcomes for similar cases, by an analysis of four pairs of judgments (from Norway, Estonia, and Finland) about care orders, using thematic analysis. The comparison is within the pairs and not across countries. I find that the variance in outcome and reasoning seems to be a result of discretionary evaluations: risk, cooperation of the parents, and the potential of services to alleviate the situation are interpreted differently in the cases and lead to different outcomes. This appears to be a legitimate use of the discretionary space available to the decision-makers. The decisions are justified with ‘good reasons’ mostly related to threshold, the least intrusive intervention principle, and the best interests of the child. Such justifications are suitable to provide accountability and legitimacy, but the reasoning is at times lacking transparency and thoroughness. The reasoning is longer in the non-removal cases, suggesting that more thorough reasoning is required when the decision-makers depart from the most common outcome.

SAMMENDRAG

The reasoning is longer in the non-removal cases, indicating that more thorough reasoning is required when the decision-makers depart from the most common outcome.

Hvorfor er det slik at noen omsorgsovertakelser ender med at barnet blir fjernet fra foreldrenes omsorg, mens i andre blir hun ikke det, til tross for at sakene er like? Denne artikkelen undersøker hvordan beslutningstakere resonnerer og begrunner ulike utfall for like saker, gjennom en analyse av fire par av dommer (fra Norge, Estland, og Finland) i omsorgsovertakelser, gjennom å bruke tematisk analyse. Sammenligningen er innad i parene, og ikke på tvers av land. Jeg finner at variasjonen i utfall og resonnering virker å være et resultat av skjønnsmessige vurderinger: risiko, foreldrenes samarbeid, og hjelpetjenesters potensiale til å forbedre situasjonen blir vurdert ulikt i sakene og leder til forskjellige utfall. Dette virker å være legitim bruk av beslutningstakernes skjønnsrom. Beslutningene er begrunnet med «gode grunner», for det meste relatert til terskel for inngripen, det minste inngreps prinsipp, og barnets beste. Slike begrunnelser er godt egnet til å gi ansvarlighet og legitimitet, men resonneringen mangler tidvis transparens og grundighet. Resonneringen er lengre i saker der barnet ikke blir fjernet, som indikerer at mer grundig resonnering er nødvendig når beslutningstakerne avviker fra det mest vanlige utfallet.

Introduction

Why is it that some care order cases result in the child being removed from parental care, while in others she is not, despite the cases being similar on relevant and visible factors? In this paper, I investigate how decision-makers reason and justify individual cases with different outcomes through analysing judgments in care orders cases that display relevant similarities. In such decisions, decision-makers are given discretion to find the best possible solution, but discretion can lead to unjustified decision variability and threaten the legitimacy of the decisions as well as the decision-making system.

State mandated decision-makers implement child protection policy and wield power over individual citizens’ lives – equal treatment in their decisions are vital for the rule of law. Differences in treatment must be based on differences between the cases. Child protection systems are established to safeguard the rights and welfare of children. Among the interventions available are care orders, placing a child in state care. The right decisions must be made regarding severe interventions into family life, especially in the case of newborns where a separation from their birth parents can be permanent (Magruder & Berrick, Citation2023). The wrong decision can leave a child in a dangerous situation, or unnecessarily interfere into a family, both can be traumatic.

Care order decisions are important to study given the consequences for the involved parties, the legitimacy of the child protection system and the rule of law. As care order cases are complex and laws can be ambiguous, the decision-makers need to use discretion which ‘has come to connote … autonomy in judgement and decision’ (Galligan, Citation1987, p. 8). Discretion poses an inherent threat to equal treatment as it involves freedom in making decisions according to set standards (Molander, Citation2016). Decision-makers must justify their decisions using ‘good reasons’ to facilitate accountability and show that the decisions are legitimate (Molander, Citation2016). Care orders are useful study objects as they are ‘discretion in practice’, and their justifications are accessible in written judgments.

While discretion in child protection is an established research area, this paper adds a novel dimension by investigating how different outcomes in similar cases are reasoned, through comparing four case pairs consisting of eight individual care order cases concerning newborns. From a large project data material in which characteristics of 216 cases are registered, a rigorous selection process detailed in the methods section determined the selection of cases that share formal aspects like country of origin and decision year, and central aspects of the involved parties. Two of the pairs are from Norway, one from Finland and one from Estonia. As the aim is comparison within the pairs and not across countries, the same discretionary context applies to the cases within each pair. Norway and Finland practice group-decision-making, in Estonia a single judge decides.

To situate my approach, I begin with an overview over relevant literature, theory, and the empirical context. Next, the methods used are presented, before then findings are described and discussed. Finally, I provide some concluding remarks.

Equal treatment and discretion

The equal treatment principle is a core component of the rule of law, and according to Aristotle, ‘alike cases should be treated alike and unalike cases should be treated unalike.’ (as cited by Westerman, Citation2015, p. 83). The inclusive starting point of the principle is that all cases should be treated similarly, all exceptions have to be founded in relevant differences, and the difference in treatment has to be proportionate to the aim of the rule (Westerman, Citation2015).

Decision-makers are given discretion when making decisions governed by general laws. Discretion gives limited freedom and ‘ensures proper examination and treatment of individual cases because it permits professionals to consider what is particular and unique’ (Molander, Citation2016, p. 51). The aim is justifiable outcome variation – that different outcomes are based on relevant differences in the cases or in the evaluation of facts. There is an inherent danger that discretion can lead to arbitrary decisions and threaten equal treatment, if cases without relevant differences are treated differently, or if relevant differences in cases are overlooked.

Discretionary reasoning takes place within space surrounded by the laws and guidelines that must be followed. Wallander & Molander explain that ‘To reason means to attempt to find justifiable answers to questions.’ (Wall Ander & Molander, Citation2014, p. 3), reasoning regarding what the case is about and what should be done (Molander, Citation2016). To facilitate accountability, the result of reasoning is documented in written care order judgments. To be legitimate, the decisions need to be justified by what Molander (Citation2016) calls ‘good’ or ‘public reasons’: they need to be generally accessible, related to the decision-makers’ expert knowledge, applicable laws and generally accepted principles. If the reasoning or the reasons justifying the decision are absent, incomprehensible or not in line with what policymakers authorised, the trust in the delegated decision-making power and the legitimacy of the decisions can be questioned (Molander, Citation2016).

Discretionary decision-making

There is a growing literature on discretionary decision-making, focussing on for example handling of debt relief (Larsson & Jacobsson, Citation2013), bureaucratic treatment of migrants (van den Bogaard et al., Citation2022), and medical assessments (Bjorvatn et al., Citation2020). Raaphorst (Citation2021) summarises administrative justice research on treatment of similar and different cases, highlighting the tension between equal treatment and discretion.

Some research has focused on decision variability in child protection (Keddell, Citation2023), and research on empirical child protection decision-making has been productive in recent years (Helland, Citation2021b, Citation2021a; Juhasz, Citation2020; Krutzinna & Skivenes, Citation2021; Løvlie, Citation2023; Løvlie & Skivenes, Citation2021; Luhamaa et al., Citation2021). Different approaches to understand and predict child protection decision-making have been developed, like Dalgleish’s (Citation2003) work on the role of values related to decision thresholds in child protection, or the decision-making ecology (Fluke et al., Citation2020) which aims to explain why child protection decisions are made as they are. Comparisons of treatment has been researched through vignette studies (e.g. Bartelink et al., Citation2014; Falconer & Shardlow, Citation2018). However, these have not compared the treatment of empirical cases in regards to equal treatment specifically, despite being recognised as an important topic (Burns et al., Citation2016; Rothstein, Citation1998).

Legal systems and child protection

The eight analysed cases were decided in Estonia, Norway and Finland in 2016. In the same year between 10 and 16.5 per 1.000 children were placed in out-of-home care in these countries (see ). In Finland, only care orders where a party objects are decided in court, and the number reported in are for the whole year. Estonia and Norway report all out-of-home placements, at one point of the year. Interpretation of the table should take this into consideration.

Table 1. Key facts for Estonian, Finnish and Norwegian child protection systems.

The Norwegian and Finnish child protection systems are classified as child centric orientations, where the rights of children, preventive services and early intervention are emphasised, aiming at promoting wellbeing and equal opportunities (Gilbert et al., Citation2011). Cooperation with parents is sought after, to facilitate a therapeutic effect, actively working to uphold the right to respect for family life. The Estonian child protection system can be classified as a risk-oriented system (Luhamaa et al., Citation2021), meaning that the threshold for intervention is high, and focus is on keeping children safe from harm (Gilbert et al., Citation2011).

Norwegian care orders are usually decided in the Child Welfare Tribunal, by a jurist, a child expert and a layperson. The child protection agency and private parties are represented by lawyers, and evidence is mainly given orally (Lov Om Barnevern (Barnevernsloven), Citation2021). In 2022, there were submitted applications to the Tribunal averaging 50 applications per jurist (Fylkesnemnda for barnevern og sosiale saker, Citation2023). The Finnish care orders are decided in a generalist administrative court, by two judges and one expert (Höjer & Pösö, CitationIn press). The court is obliged to hear the child’s parents and the child protection agency, but while proceedings are mainly based on written statements the proportion of oral hearings is increasing (was around 1/3 cases in 2017) (Pösö & Huhtanen, Citation2016). The courts are generally considered to be under-resourced (ibid). In Estonia, single generalist judges who tend to specialize into family law matters decide care orders. They are required to hear parents and older children.

Deliberative theory through which group decision-making can be understood finds that the quality of the decision is based on the process, not the outcome (Skivenes & Tonheim, Citation2017). Care orders are decided by one decision-maker in Estonia and three in Norway and Finland. While it can give valuable insights into care order decision-making, it is outside the scope of this paper to discuss the deliberative process as well as the outcome.

Legislation in all three countries contains a threshold, and removals are only permitted as the last resort (Luhamaa et al., Citation2021). All three are civil law countries where decision-makers are bound by a codified collection of laws (Danner & Bernal, Citation1994). When considering care orders for newborn children, decision-makers make individual decisions in specific cases and their discretion is not bound by precedent in the same way as in common law systems. All three have an appeal system for care orders in place (Burns et al., Citation2016; Eesti Kohtud, Citationn.d.). In all three countries, the written judgments are legally required to include the reasons for the decision, and the relevant facts and evidence for the decision (Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism, Citation2019). Norway and Finland require an assessment of the facts in light of legal norms, and Norway and Estonia require specification of which legal norms guide the decision and assessment. Norwegian judgments also need to include an assessment of the central claims of the parties.

Methods

Data material

The data material was selected from a project data material of 216 judgments from Austria, England, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Norway, and Spain as specified in Appendix 1. All judgments concern a newborn and her birth parents, decided in the first instance decision-making body. The child was removed from their parent’s care within 30 days of birth or after a stay in a supervised parent–child facility. The material was collected between February 2018 and October 2019, for details on data collection, coding and ethical approvals, see Appendix 1.

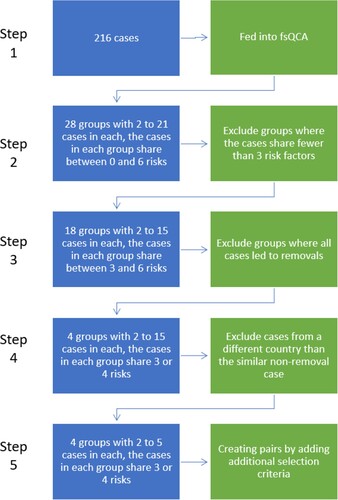

From the 216 judgments, I have selected the paper data material – the eight cases that are pairwise similar (see ). In each pair, one case ends in a care order, while the other does not. I have selected cases that share the maximum number of central risk factors but differed in outcome to ensure that the most similar cases in the project material were analysed for this paper. They share a range of formal, legal and case-internal aspects, and are highly similar. Despite different outcomes the cases are classified as similar, as the outcome depends on the decision-makers’ discretion, which carries an inherent potential for decision variability.

To identify which cases shared the highest number of attributes, the program fsQCA sorted the 216 cases into groups that share three or four of six maternal risk factors, in addition to the formal and case-related characteristics that are applicable to the whole project data material. fsQCA allows sorting a number of cases by their attributes and shows mutually exclusive groups where cases are sorted according to the highest number of shared attributes. It is positive that the cases are from countries where a full sample was available for the same year as it ensures that the selection was from a complete material. See Appendix 1 for details on the selection process.

Finnish judgments are around 7–9 pages per judgment. Estonian judgments are around 6–10 pages. Norwegian judgments can range from 8 to 23 pages, but around 12 pages is typical. The judgements are required to include the decision-makers’ reasoning, and the facts and evidence they found to be relevant (Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism, Citation2019).

Risk factors are well suited for finding similar care order cases as applications are made to prevent harm. Parental problems can significantly put the child at risk and influence parents’ ability to provide adequate care (Ward et al., Citation2014). The maternal risk factors I used to sort and select are perpetration of domestic violence, mental health issues, removal of previous children, parenting insufficiencies, substance misuse, and learning difficulties (see Appendix 1 for full description). Domestic violence, mental health issues and substance misuse all are documented to potentially greatly influence parenting capabilities (Ward et al., Citation2014). Having previous children taken into care signals that previous parenting has been found to be inadequate. No pairs in the project data material shared more than four of these risk factors. As mothers are typically the primary caregiver for newborns, I focus on risks related to the mother.

Table 2. Pair characteristics.

Thematic analysis

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the data, a method suitable to qualitatively analyse patterns of meaning, a flexible approach suitable to finding and showing both similarities and differences (Braun & Clarke, Citation2022). Braun and Clarke (Citation2022) describe six steps, (1) getting acquainted with the data material, (2) coding, (3) creating initial themes, (4) reviewing them, (5) defining and naming themes and (6) producing the report. These are not linear steps but can be switched between in a dynamic and iterative process. In my case, especially steps 2 and 4 were revisited several times. I mapped the conclusion of the decision-makers’ reasoning, and found the following five concluding reasons (full coding description in Appendix 2):

Child’s best interests/welfare/rights

Parents providing inadequate care

Assistive services are sufficient/insufficient

Threshold not crossed

Positive parental effort

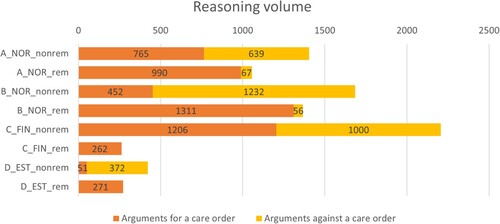

Reasoning volume

To determine the reasoning volume, I counted the number of words in the decision-makers’ reasoning, when it concerns the specific case.

Limitations

While being a valuable and trustworthy data source, the data material has some limitations. It does not show the quality of the evidence presented in the adjudication, which is likely to influence the reasoning of the decision-makers, as presentation will influence interpretation. The adjudication and my selection can only be as good as the presented evidence. Additionally, inferences between decision-maker or setting characteristics and outcome cannot be established, and it cannot identify discrimination in the child protection system as full case files are not available.

Findings

Pair A

Pair A consists of two Norwegian cases with striking similarities. Both mothers have cognitive difficulties and mental health problems. The fathers are no help – in the removal case he is unknown, and in the non-removal he leaves the family. Both mothers stay at a parent–child centre with their child.

Central in both cases are negative reports from the parent–child centre, and the decision-makers’ evaluation of these. In A_NOR_nonrem, the mother’s inability to provide adequate care in the centre is attributed to the stress of the situation. In A_NOR_rem, however, the decision-makers state that the reports give a realistic picture of the mother’s caring abilities, which allows them to conclude that no assistive services are sufficient to alleviate the situation, adding that removal is in the best interests of the child:

It seems both necessary and in CHILD’s best interests that a care order is decided for and that she is placed in a foster home.

Assistive services have previously not been tried in this case, and the Tribunal has under doubt come to the conclusion that assistive services will give a satisfactory care situation for CHILD.

Pair B

Pair B contains two Norwegian cases where the mothers lost care of older children, both have mental health issues and misuse substances, and the newborns are taken into care from the hospital.

Central in both cases are reports by mental health and substance misuse treatment professionals. In B_NOR_rem, the reports focus on mother’s mental health issues and difficulties in treatment. The decision-makers conclude that she is unable to provide adequate care due to her mental health and that a care order is in the child's best interests. The absence of a father is not discussed by the decision-makers.

In B_NOR_nonrem, the reports are conflicting, and the decision-makers side with those favourable to the parents, supported by their impressions of the parents in the adjudication. Although the mother has lost care for a sibling of the newborn and the father has been violent towards a previous child (and partner), the decision-makers find previous parenting experience advantageous. The decision-makers conclude their reasoning by stating that assistive services can be sufficient:

The majority has concluded that the requirements for a care order not are fulfilled as they find that a care order is not required as satisfactory conditions for the child can be created through assistive services.

Pair C

Two Finnish cases make up pair C. The parents have violent relationships, and both mothers’ cognitive deficits, mental health problems and insufficient parenting abilities as well as uncooperativeness (C_FIN_rem) and varying cooperation (C_FIN_nonrem) are described. After birth of the child, both families moved to a supervised setting, in the removal case to the mothers’ former foster carers.

In both cases, reports from the supervised setting are central. In C_FIN_rem, the court accepts the reports, concluding that the mother is providing inadequate care and that assistive services will be insufficient:

… the Administrative Court considers that the upbringing-related conditions of the infant child with her parents pose a serious threat to her health and development within the meaning of section 40 of the Child Welfare Act. The child welfare support measures in open care have proven to be insufficient to implement care in the best interests of the child. This being the case, grounds for taking the child into custody exist.

In C_FIN_nonrem the court concludes that it is not sufficiently clarified whether the mother can care for the child with assistance – and thus rejects the care order. While this is the singular concluding reason in this case, the reasoning reveals that the mother’s family network and her (varying) cooperativeness are important. The reports from the parent–child centre and medical professionals are discounted in favour of the parents, stating that the episodes were not so serious or not the parents’ fault. The reasoning in C_FIN_nonrem is far longer (see ) and provides more substantial information than the removal case.

Pair D

In pair D it is the most difficult to pinpoint why the cases got different outcomes. It contains two Estonian cases where both mothers have lost care of previous children. Both have misused substances for several years and continued doing so during and after pregnancy. In both cases the child was taken into care from the hospital. Only summaries of the mother’s risks are provided (in the non-removal always in the context of how she mitigated these), and almost no information on the children and their needs.

In both cases, the decision-maker states that the mother has failed to provide adequate care for her child. In neither case is it detailed by the decision-maker how she has failed to provide care, but in D_EST_nonrem it is concluded that the threshold is not crossed:

… that the mother, in various periods of her life, has had problems with herself as well as with raising the children, but the circumstances pointed out by the petitioner’s representative at the court session held on xx.xx.2016 (the absence of a doctor’s certificate, the change of jobs and place of residence) are not so serious that would justify the application of the most extreme family law measure

The court’s reasoning in the removal case contains only a concise summary of the mothers’ risks, and concludes that she cannot provide adequate care:

It emerges from the explanations of the parties to the proceedings and the case file (…) that the mother is a person with subsistence difficulties who consumes narcotic substances and alcohol. The mother does not have the desire or social skills to raise the child on her own.

Concluding reasons

The decision-makers use more concluding reasons in removal cases (see ). The most frequent concluding reasons are the child’s best interests/welfare/rights, parents providing inadequate care, and the sufficiency/insufficiency of assistive services.

Table 3. Concluding reasons.

Reasoning volume

The decision-makers differ greatly in how much reasoning they include before concluding. Generally, the reasoning of non-removal cases consists of more words, and of arguments both in favour and against a care order (see ). The removal cases are far more one-sided, most of their reasoning concerns negative aspects of the case.

Discussion

The analysis of the data material shows that discretionary interpretation of the parents and their situation (e.g. risk or their potential to benefit from assistive services) led to different outcomes in these similar cases. The decision-makers in the cases conclude with five reasons, of which three are stated across most of the cases: child’s best interests/welfare/rights, parents providing inadequate care, and assistive services are sufficient/insufficient. These are ‘good reasons’, in line with Molander (Citation2016), based on international and domestic law and in line with generally accepted values – making the decisions acceptable to the public (Langvatn, Citation2016). They are in line with the legal requirements for care orders, which for all three countries require crossing of a threshold, that the decision is in the best interests of the child, and that a care order is the last resort, not permitted when in-home services can be sufficient (Luhamaa et al., Citation2021). Helland found that over time, Norwegian Supreme court judgments concerning child welfare adoption cases developed towards more ‘rational, well-reasoned and thorough judgments’ (Helland, Citation2021a, p. 633), indicating that the fulfilment of the obligation towards ‘good reasons’ is under development.

In addition to the concluding reasons, I found that the reasoning preceding the concluding reasons is longer in non-removal cases, and typically contains both positive and negative aspects of the case, while removal cases focus more (singularly) on the negatives.

Connecting reasoning and reasons

Concluding reasons are preceded and should be supported by reasoning – the decision-makers’ process of determining what should be done in the specific case (Molander, Citation2016). In the judgments they discuss, weigh, and lay out what they find to be relevant aspects, and account for their impact on the conclusion. Here I discuss the prevalence of concluding reasons and how the reasoning supports them.

The effectiveness of services is central in many of the cases, also mirrored in the concluding reasons. The content of services is discussed somewhat, but more important is the prospect of the parents benefiting from them. Ruiken (Citation2022) found that the involvement of assistive and health services is the most prevalent protective factor that decision-makers found relevant in newborn care order cases involving maternal substance misuse. Concluding that services will be sufficient is discretionary – supporting this conclusion with reference to positive testimony from professionals and support from private network, done in several of the analysed cases, increases the accountability as it makes the reasoning more transparent. For example, in case A_NOR_nonrem, the mother found a supportive network while absconding with the child. The decision-makers concluded that while the threshold for removal was crossed, the network that now supported her would facilitate the implementation of services to the point where it would create satisfactory conditions for the child.

Although rare among the concluding reasons, the attitude of the parents is often discussed in the reasoning. Attitude can magnify risk or risk mitigation, and willingness and capacity to change have been found to be important considerations for decision-makers (Juhasz, Citation2020; Løvlie & Skivenes, Citation2021). A positive and cooperative attitude can increase the likelihood of services being effective or mitigate risk directly, like in B_NOR_nonrem, where parents are adamant, they will not allow risky behavior in the other. If the attitude is negative, the risk can increase – like in C_FIN_rem, where the mother refuses to separate from the violent father.

While the parents’ attitudes are prevalent in reasoning but not among concluding reasons, the child’s best interests is the opposite: the most prevalent concluding reason but rarely substantiated by specific case aspects discussed in the reasoning. Lack of specificity can be problematic for the accountability and legitimacy of the decision, which depends on the quality and availability of reasons (Molander, Citation2016). In several of the analyzed cases, the child is barely mentioned, but still the decision-makers conclude that the decision is in the child's best interests. Newborns are nonverbal, but even in decisions regarding older children their view is often not included (Helland, Citation2021a; McEwan-Strand & Skivenes, Citation2020). At best, blanket statements, as quoted from A_NOR_rem in the findings section, are suboptimal reasoning; at worst they can be seen as endangering accountability.

The concluding reasons discussed above are relevant regarding risk. Risk and risk mitigation have been found to be central considerations in care order cases, often dominating the reasoning (Krutzinna & Skivenes, Citation2021; Ruiken, Citation2022). Risk assessments are difficult, highly discretionary (Berrick et al., Citation2017) and can vary across decision-makers and contexts (Križ & Skivenes, Citation2013). Two concluding reasons are directly tied to risk assessments: parents providing inadequate care (given in all four removal cases), and that the threshold is not crossed. Risk is dealt with in different ways, acknowledged but assessed as not justifying a removal like in D_EST_nonrem, or attributed to something outside of the parents’ control, like in C_FIN_nonrem. In B_NOR_nonrem, the decision-makers adjudicating the case had dissenting opinions, disagreeing about the viability of risk mitigation in the case and the mother’s potential to benefit from assistive services. This shows how difficult it can be to evaluate such cases, and that several outcomes can be appropriate.

There are indications that the decision-makers consider it more important to clearly show the thoroughness of their reasoning when their decisions depart from the common or obvious outcome. Few newborn care orders are decided each year, most are approved, and non-removals are the exception (see ). I find that the reasoning of removals is much shorter than of non-removals (in some instances the brevity makes it difficult to follow the decision-makers reasoning, especially C_EST_rem and D_FIN_rem) while non-removals are longer and more balanced in content. This confirms a reasoning pattern where challenges to the position of the child protection agency and related services are more thoroughly argued for: Helland (Citation2021b) in her analysis of adoption cases from England and Norway, found that the adoption petition was confirmed without much balancing or challenge of the states’ arguments. Løvlie (Citation2023) found that moderating the implications of reports from a parent–child center (like in A_NOR-nonrem and C_FIN_nonrem) may be an expression of discretion that requires further justification to be legitimate.

Implications

What stands out in the reasoning and justifications of non-removals vs. removals in the analysed pairs? The same things are evaluated, parents’ attitude, the feasibility of service implementation and support from professionals and private networks, but the inferences drawn from these case aspects differ due to discretionary judgment. Empirical research has shown the relevance of these case elements on the safety of children (Ward et al., Citation2014) – this is an empirical fact. How the decision-makers evaluate the presence of these case facts will mitigate risk in the specific case is subject to discretionary considerations. The facts of the cases are interpreted differently, and the cases have different outcomes as a result of the discretionary reasoning by the decision-makers. There may be ‘noneliminable sources of variation’ in the interpretative exercise and reasoning, that this variation leads to different outcomes may be expected – and reasonable (Molander, Citation2016, p. 4).

Different outcomes for similar cases can lead one to question the legitimacy of the decisions – good reasoning quality can assure trust in the decision and system. There are some parts in the reasoning of the analysed cases that are not substantiated very well – for example, B_NOR_nonrem, where it is stated as a positive that the parents are experienced caregivers, but the father’s history of domestic violence as well as the mother’s loss of the right to care for a previous child are not problematised. It is also difficult to understand post-hoc why the decision-maker in D_EST_rem omits the positive changes that the case mother has achieved, when they are acknowledged in the non-removal. Another is the general lack of specific substantiation of child’s best interests arguments. This suboptimal reasoning, also found by Dickens et al. (Citation2019) in child protection files, makes it difficult to assess whether the process has been thorough, and the question of legitimacy is also difficult to evaluate, threatening accountability (Molander, Citation2016).

Despite shortcomings in the reasoning, the cases are concluded with ‘good reasons’. Previous studies have found that the need for intervention in the same case can be evaluated differently by different decision-makers (Berrick et al., Citation2020). Thus, it seems understandable that discretionary evaluations of complex and interpretative case facts lead to different outcomes in similar cases. Several outcomes can be appropriate, and this highlights the difficult nature of discretionary decisions. It also indicates that the cases can be similar and receive different but legitimate outcomes. The question remains if it is enough to conclude with ‘good reasons’ if the reasoning is suboptimal.

Concluding remarks

The cases are justified with ‘good reasons’ related to relevant accepted empirical knowledge on children and safe childhoods, applicable laws and generally accepted social principles. The decision-makers are complying with accountability demands by using publicly accessible reasons to conclude.

While the justifications are good, the reasoning has room for improvement. It is difficult to assess the equal treatment obligation in these cases when the removals are sparsely reasoned and explanations of the basis for concluding reasons are lacking. Decision-makers are given discretion based on trust that they’ll make good decisions, this trust is maintained by accountability: ‘individuals should be able to "account” for their judgment and decisions’ (Molander, Citation2016, p. 60). When the account for the reasoning is suboptimal, this may harm the legitimacy of the individual decision, and the system as a whole. It may very well be that the decision-making process was sound and fair and the decision the best one, but when critique is voiced towards a decision process, there can be reason to ask whether the decision or process was fully legitimate.

Interpretative social facts about the parents and their situation stand out as allowing non-removal. The variance in outcome and reasoning seems to be a result of discretionary evaluations of case facts, a legitimate use of the discretionary space available to the decision-makers. They are difficult decisions; in some cases several outcomes could be legitimate based on the assessments by decision-makers. These seem to be instances of reasonable disagreement, to be expected when discretion is exercised (Molander, Citation2016).

Further research involving a greater number of matched cases would be very beneficial for generalisability.

Structural accountability mechanisms like specifying applicable rights and standards could compel decision-makers to further justify their decisions (Molander, Citation2016). Molander also mentions epistemic accountability mechanisms aimed at improving the quality of decision-making. Such policy changes, stretching across countries, could increase the accountability of decision-makers, but would require considerable political will.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for constructive feedback and comments from both my supervisors Dr Marit Skivenes and Dr Tarja Pösö. Furthermore, thanks to anonymous reviewers, and Dr Jenny Krutzinna and Dr Audun Løvlie. The paper has been presented at seminars at the University of Bergen.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Barbara Ruiken

Barbara Ruiken is a PhD fellow at the Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism, department of Government at the University of Bergen, Norway. She previously worked as a research assistant, and holds an M.Phil. in Administration and Organization theory from the University of Bergen. Her PhD project ‘Understanding risk and protective factors in child’s best interest decision’ focusses on discretion by decision-makers in high-stake child protection cases, and employs a comparative lens. Her research interests include discretionary decision-making, child protection policy implementation and the role of risk and protective factors in care order proceedings concerning newborn children.

References

- Bartelink, C., van Yperen, T. A., Ten Berge, I. J., de Kwaadsteniet, L., & Witteman, C. L. M. (2014). Agreement on child maltreatment decisions: A nonrandomized study on the effects of structured decision-making. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(5), 639–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-014-9259-9

- Berrick, J. D., Dickens, J., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (2017). A cross-country comparison of child welfare systems and workers' responses to children appearing to be at risk or in need of help. Child Abuse Review, 26(4), 305–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2485

- Berrick, J. D., Dickens, J., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (2020). Are child protection workers and judges in alignment with citizens when considering interventions into a family? A cross-country study of four jurisdictions. Children and Youth Services Review, 108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104562

- Berrick, J. D., Gilbert, N., & Skivenes, M. (2023). Child protection systems across the world. In J. D. Berrick, N. Gilbert, & M. Skivenes (Eds.), Oxford handbook of child protection systems. Oxford University Press.

- Bjorvatn, A., Magnussen, A.-M., & Wallander, L. (2020). Law and medical practice: A comparative vignette survey of cardiologists in Norway and Denmark. SAGE Open Medicine, 8, 205031212094621. https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312120946215

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE.

- Burns, K., Pösö, T., & Skivenes, M. (2016). Child welfare removals by the state: A cross-country analysis of decision-making systems. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190459567.001.0001

- Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism. (2019). Requirements for judgments in care order decisions in 8 countries. Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism. https://www.discretion.uib.no/formal-legal-requirements-for-judgments-in-care-order-decisions-in-8-countries/.

- Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism. (2021). Description of coding results—216 care order cases concerning newborn children. Centre for Research on Discretion and Paternalism. https://discretion.uib.no/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Newborn-Description-of-coding-results.pdf.

- Dalgleish, L. I. (2003). Risks, needs and consequences. In M. C. Calder, & S. Hackett (Eds.), Assessment in child care: Using and developing frameworks for practice (pp. 86–99). Russel House Pub.

- Danner, R. A., Bernal, M.-L. H., & American Association of Law Libraries. (1994). Introduction to foreign legal systems. Oceana Publications.

- Dickens, J., Masson, J., Garside, L., Young, J., & Bader, K. (2019). Courts, care proceedings and outcomes uncertainty: The challenges of achieving and assessing “good outcomes” for children after child protection proceedings. Child & Family Social Work, 24(4), 574–581. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12638

- Falconer, R., & Shardlow, S. M. (2018). Comparing child protection decision-making in England and Finland: Supervised or supported judgement? Journal of Social Work Practice, 32(2), 111–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2018.1438996

- Fluke, J. D., López, M. L., Benbenishty, R., Knorth, E. J., & Baumann, D. J. (eds.). (2020). Decision-Making and judgment in child welfare and protection: Theory. In Research, and practice (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190059538.001.0001

- Fylkesnemnda for barnevern og sosiale saker. (2023). Årsrapport Årsregnskap 2022. Barneverns- og helsenemnda. https://www.bvhn.no/aarsrapporter.6485272-568824.html.

- Galligan, D. J. (1987). Discretionary powers: A legal study of official discretion. Clarendon Press.

- Gilbert, N., Parton, N., & Skivenes, M. (2011). Changing patterns of response and emerging orientations. In N. Gilbert, N. Parton, & M. Skivenes (Eds.), Child protection systems: International trends and orientations (1st ed., pp. 243–257). Oxford University Press.

- Helland, H. S. (2021). In the best interest of the child? Justifying decisions on adoption from care in the Norwegian supreme court. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 29(3), 609–639. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-29030004

- Helland, H. S. (2021). Reasoning between rules and discretion: A comparative study of the normative platform for best interest decision-making on adoption in England and Norway. International Journal of Law, Policy and the Family, 35(1), ebab036. https://doi.org/10.1093/lawfam/ebab036

- Höjer, I., & Pösö, T. (In press). Child protection in Finland and Sweden. In J. D. Berrick, N. Gilbert, & M. Skivenes (Eds.), International Handbook of Child Protection Systems. Oxford University Press.

- Juhasz, I. B. (2020). Child welfare and future assessments – An analysis of discretionary decision-making in newborn removals in Norway. Children and Youth Services Review, 116), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105137

- Keddell, E. (2023). On decision variability in child protection: Respect, interactive universalism and ethics of care. Ethics and Social Welfare, 17(0), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2022.2073381

- Eesti Kohtud. (n.d.). The Estonian court system | Eesti Kohtud. Retrieved May 5, 2023, from https://www.kohus.ee/en/estonian-courts/estonian-court-system.

- Križ, K., & Skivenes, M. (2013). Systemic differences in views on risk: A comparative case vignette study of risk assessment in England, Norway and the United States (California). Children and Youth Services Review, 35(11), 1862–1870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.09.001

- Krutzinna, J., & Skivenes, M. (2021). Judging parental competence: A cross-country analysis of judicial decision makers' written assessment of mothers' parenting capacities in newborn removal cases. Child & Family Social Work, 26(11), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12788

- Langvatn, S. A. (2016). Should international courts Use public reason? Ethics & International Affairs, 30(3), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0892679416000265

- Larsson, B., & Jacobsson, B. (2013). Discretion in the “backyard of Law”: case handling of debt relief in Sweden. Professions and Professionalism, 3(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.438

- Lov om barnevern (Barnevernsloven). (2021). https://lovdata.no/dokument/NL/lov/1992-07-17-100.

- Løvlie, A. G. (2023). Evidence in Norwegian child protection interventions – analysing cases of familial violence. Child & Family Social Work, 28(1), 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12956

- Løvlie, A. G., & Skivenes, M. (2021). Justifying interventions in Norwegian child protection. Nordic Journal on Law and Society, 4), https://doi.org/10.36368/njolas.v4i02.178

- Luhamaa, K., McEwan-Strand, A., Ruiken, B., Skivenes, M., & Wingens, F. (2021). Services and support for mothers and newborn babies in vulnerable situations: A study of eight European jurisdictions. Children and Youth Services Review, 120(1), 105762. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105762

- Magruder, J., & Berrick, J. D. (2023). A longitudinal investigation of infants and out-of-home care. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 17(0), 390–407. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2022.2036294

- McEwan-Strand, A., & Skivenes, M. (2020). Children’s capacities and role in matters of great significance for them. International Journal of Children’s Rights, 28(3), 632–665. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718182-02803006

- Molander, A. (2016). Discretion in the welfare state: Social rights and professional judgment. Routledge.

- Pösö, T., & Huhtanen, R. (2016). Removals of children in Finland: A mix of voluntary and involuntary decisions. In K. Burns, T. Pösö, & M. Skivenes (Eds.), Child welfare removals by the state: A cross-country analysis of decision-making systems. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780190459567.003.0002

- Raaphorst, N. J. (2021). Administrative justice in street-level decision making: Equal treatment and responsiveness. In J. Tomlinson, R. Thomas, M. Hertogh, & R. Kirkham (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of administrative justice (pp. 1–30). Oxford University Press. https://hdl.handle.net/1887/139073.

- Rothstein, B. (1998). Just institutions matter: The moral and political logic of the universal welfare state. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511598449

- Ruiken, B. (2022). Analyzing decision-maker’s justifications of care orders for newborn children: Equal and individualized treatment. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 0(0), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2022.2158990

- Skivenes, M., & Tonheim, M. (2017). Deliberative decision-making on the Norwegian county social welfare board: The experiences of expert and Lay members. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 11(1), 108–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2016.1242447

- Statistics Estonia. (2022, December 5). RV021: POPULATION, 1 JANUARY by Sex, Year and Age group. Statistical Database. Statistics Estonia. https://andmed.stat.ee/en/stat/rahvastik__rahvastikunaitajad-ja-koosseis__rahvaarv-ja-rahvastiku-koosseis/RV021/table/tableViewLayout2.

- van den Bogaard, R.-M., Horta, A. C., Van Doren, W., Desmet, E., & Valcke, A. (2022). Procedural (in)justice for EU citizens moving to Belgium: An inquiry into municipal registration practices. Citizenship Studies, 26, 995–1010. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2022.2137944

- Wallander, L., & Molander, A. (2014). Disentangling professional discretion: A conceptual and methodological approach. Professions and Professionalism, 4(3), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.7577/pp.808

- Ward, H., Brown, R., & Hyde-Dryden, G. (2014). Assessing parental capacity to change when children are on the edge of care: An overview of current research evidence (p. 193). Department for Education.

- Westerman, P. C. (2015). The uneasy marriage between Law and Equality. Laws, 4(1), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.3390/laws4010082

Appendix 1

This appendix consists of two parts. The first part describes the project data material of 216 cases, and the coding process of the risk factors that were used to select the cases for the paper data material. The paper data material was selected from the project data material, this process is described in the second part of the appendix.

Part 1: The project data material

The data material is part of the DISCRETION and ACCEPTABILITY projects.

A description of data collection, translation, and ethics approvals is available here: https://www.discretion.uib.no/projects/supplementary-documentation/#1552297109931-cf15569f-4fb9

Table A1. Overview over the data material the pairs were selected from.

Estonian care order judgments are around 6–10 pages.

Finnish care order judgments are around 7–9 pages per judgment.

Norwegian care order judgments can range from 8 to 23 pages, but around 12 pages is typical.

Mapping of risk factors in the project data material

The selection criteria were coded for the whole project material in a separate process prior to the coding for the paper. For an overview over the results of this process, please see https://www.discretion.uib.no/projects/supplementary-documentation/#1552297109931-cf15569f-4fb9. The judgments were coded and reliability tested by a team of 9 researchers and research assistants in a collaborative process led by the PI of the projects, between September 2018 and July 2019. In general, the coding process consisted of 1 person reading the judgement and mapping the content with values according to the pre-set coding description. A second coder then read the same judgements and made amendments to the coding where they deemed fit.

At least one person coded, and at least one person (other than the first coder) reliability tested the coding. Due to additional codes and large quantities of codes the workload of coding and reliability testing was split between several people. No one coded and reliability tested the same codes for the same cases.

When coders discovered confusions over the coding description or discrepancies in the coding, discussions were had in the team and the coding description updated. When necessary, the coded material was then revisited and amended. Logs were kept.

The entire judgments from Estonia and Finland were included for coding of these codes, for Norway it was the parts called ‘Saken gjelder/Sakens bakgrunn’ and ‘Fylkesnemndas merknader/vurderinger’.

Part 2: The paper data material.

shows the codes from the project data material coding, which were used as selection criteria for the paper data material.

Table A2. Overview over codes used for selection of paper data material.

Step 1

The selection and sorting process started with the project data material of 216 cases from eight European countries. All of these cases shared the following characteristics: decided between 2012 and 2018, concern a newborn and their birth parents, decided in the first instance decision-making body, and the child was removed from their parent’s care within 30 days of birth or after a stay in a supervised parent-child facility.

An excel sheet with these 216 cases and six relevant maternal risk factors as variables (perpetration of domestic violence, mental health issues, removal of previous children, parenting insufficiencies, substance misuse, and learning difficulties) were added to the program fsQCA. The risk factors were mapped in a thorough and documented coding process, and are established in the literature to be associated with future harm.

The program sorted the cases into groups based on which of the variables (maternal risk factors) they shared. The groups were mutually exclusive, meaning that any case was sorted into only one group. The groups were determined by the maximum number of shared variables.

Step 2

Step 2 started with the result of step 1: 28 groups with two to 21 cases in each, that shared between zero and six risk factors. I then excluded from the selection all groups where the cases shared fewer than three risk factors, as these were considered not similar enough for a valuable analysis.

Excluded in this step: 10 groups where cases shared less than three risk factors.

Step 3

Step 3 started with the result of step 2: 18 groups, which contained between two and 15 cases each. The cases in each group shared between three and six risks. I then excluded the groups where all cases led to removals, as the aim of the analysis was to compare cases with different outcomes.

Excluded in this step: 14 groups where all cases led to removals.

Step 4

Step 4 started with the four groups that were the result of step 3. They contained between two and 15, which shared three or four maternal risk factors. So far, the groups contained cases from different countries. Three of the groups contained only one case that ended in a non-removal. All cases from a different country than the non-removal were excluded from the groups.

One group contained two non-removals (one from Finland and one from Germany). There were no removals from Germany in this group, so the German non-removal was excluded.

Excluded in this step: 29 removal cases from a different country than the non-removal, one non-removal case from a different country than the removals.

Step 5

Step 5 started with the result of step 4: four groups with two to five cases in each.

The groups respectively called pair A and pair B in the paper consisted of only one removal case and one non-removal, and were thus established as pairs. All of these cases were from 2016.

The group called pair C contained one non-removal and two removal cases, all from Finland from 2016. One of the removal cases contained additional important risk factors that the non-removal did not share, and this removal case was thus excluded. Thus, pair C was established.

The group called pair D in the paper contained one non-removal and four removal cases from Estonia. The non-removal and one of the removals were decided in 2016 and chosen to establish pair D. The three remaining cases were decided in 2015, and thus excluded.

Excluded in this step: one Finnish removal case that contained additional risk factors, and three Estonian cases from 2015.

Comment on the excluded countries

The included pairs consist of cases from Estonia, Norway, and Finland. There is nothing to my knowledge that suggests that the other five countries are better at avoiding situations in which similar cases get different treatment. All cases in the Austrian sample ended in removals, so there were no cases to match. Among the non-removals from Ireland, England, and Spain, none reported three or more of the maternal risk factors selected for sorting and selection of the paper data material. The remaining two German non-removals reported three of the risks, but one did not find a match and for the last the data material was incomplete, excluding it from analysis.

Appendix 2 – coding description

This appendix describes the coding for the paper ‘A Tale of Two Cases – Investigating Reasoning in Similar Cases with Different Outcomes’

Substantive coding

What is coded

The following parts of the judgments were coded:

Estonia: ‘Reasons for the order’

Finland: ‘Reasoning of the court’

Norway: ‘Fylkesnemndas merknader/vurderinger’ (The County Social Welfare Boards’ comments/considerations) – in the case where the decision-makers’ split into a majority and minority, only the majority’s part was coded.

The limitation was done to only include the arguments of the decision-makers, and not the arguments of biological parents or child protection services/social workers. The length of the reasoning of the court described in the paper refers to these parts, and includes the parts of the reasoning where applicable law is referenced, and the conclusion of the decision-makers. It has to be noted that the Finnish judgments are formatted with a substantial indent that leaves less space on the page for text than in the other judgments.

Concluding reasons in the justifications

Coding the justifications – the direct justification for why the outcome (care order or no care order) is required. This means that the decision-makers’ summary of the situation is not included, only the reasons they mention in direct relation to the need or non-need for a care order. A lot of the contextual risks or protective aspects will be missing here. After mapping these, I have sorted them into the following intuitive/inductive descriptive categories:

Assistive services sufficient/insufficient: here the argument is that assistive services have not been tried in the case yet, and/or the assessment is that services will be sufficient to create a satisfactory care situation for the child with her birth parents. Or, the argument centers around the services that have been tried or are available, and the assessment of the decision-makers is that these were or would be insufficient to create a satisfactory care situation for the child with her biological parents.

Not providing adequate care: this argument includes statements that the parent(s) are unable or unwilling to provide adequate care for the child, that they de facto not are providing care, or that the home conditions are unsatisfactory.

Child’s best interests / welfare / rights: the outcome is required to ensure the child’s best interests, or well-being, or rights. The argument is used to justify both removals, and a non-removal.

Threshold not crossed: the decision-makers argue that the risk of harm is not so high as to justify a removal of the child.

Positive parental effort: arguments centering on the parent trying to be a good parent and wishing to care for the child.

Reasoning volume

The aim of this coding is to find out how much case-specific reasoning is included in the decision-makers’ parts. Anything related to what has happened in the case, or what can happen, will be included. Legal references not directly tied to the case will be excluded (meaning that when they present law and case law, without specifying how this relates to the case at hand, it will be excluded).

First, I coded the reasoning as described above

Then, from what I coded I coded arguments for a care order (negative events, aspects of the case), and what should count against (positive events and aspects of the case). Only focusing on case history/future, not including legal references, or the decision to go for a care order or not or instructions for what happens after the decision. Not coded is reasoning around where the child should be placed, or if there should be contact arrangements.

Then I exported the nodes, and let Word count the content of the categories.