ABSTRACT

Research on social work’s relation to local political decisions and the design of political policy documents is scarce. This paper analyses the design of local political policies for elder care in Sweden’s 290 municipalities. The policies determine delegation, i.e. care managers’ legal right to make decisions about the welfare services given to older people. By mapping documents for delegation, the results show that care managers’ delegation varies considerably between municipalities, e.g. by the decision-making being conditioned to local political guidelines, or by consultation with a manager. The Principal Agent theory (PAT) is used to discuss the findings. Analysed through the PAT, care managers can be understood as agents set to perform tasks on behalf of the politicians. Local policies can be viewed as a tool for political control by minimising risks of unpredictability and arbitrariness in decision-making. This raises questions about the role of care managers and the extent of their professional freedom while assessing needs to ensure older people a reasonable standard of living. The results highlight the importance of accounting for the structural political context and its consequences for frontline bureaucrats.

SAMMANFATTNING

Forskning om det sociala arbetets relation till lokalpolitiska beslut och utformningen av politiska policydokument är bristfällig. I denna artikel analyseras utformningen av lokalpolitiska policys för äldreomsorg i Sveriges 290 kommuner. Policydokumenten fastställer biståndshandläggares delegation – deras legala beslutsfattande om bistånd till äldre. Kartläggningen och kodningen av delegationsordningarna visar att biståndshandläggares delegation varierar avsevärt mellan Sveriges kommuner, exempelvis genom att villkora att beslutsfattandet ska följa lokala riktlinjer eller föregås av samråd med en chef. Resultatet diskuteras utifrån principal–agent teorin. Sett i ljuset av principal–agent teorin så kan biståndshandläggare betraktas som agenter – satta att utföra uppgifter på uppdrag av lokalpolitiker. Lokala policys kan ses som ett verktyg för att möjligliggöra politisk kontroll genom att minska risken för oförutsägbarhet och godtycklighet i beslutsfattandet. Detta väcker frågor om biståndshandläggares roll och omfattningen av deras professionella frihet i att bedöma behov för att tillgodose äldre en skälig levnadsnivå. Resultatet lyfter fram vikten av att synliggöra den strukturella politiska kontexten och dess konsekvenser för frontlinjebyråkrater.

Introduction

It has been argued that local political policies for care management within the social service significantly influence the needs assessment process and care managers’ discretion, placing the profession between political prioritisation and the people in need of service. While at the same time functioning as a guarantee for transparent processes for equal treatment, resource allocation and accountability, local policies can also be a tool for shrinking autonomy and controlling the profession (Boockmann et al., Citation2015; Erlandsson, Citation2018; Evans, Citation2013; Rauch, Citation2008).

While the existence of political policies has been acknowledged in previous research, it is generally assumed that care managers always have discretion to put these policies aside. Previous Swedish studies (Erlandsson, Citation2018; Nilsson, Citation2016), however, show that care managers not only perceive themselves as restricted by local political policies, due to expectations within the workplace, but that they in some municipalities have to comply with policies such as guidelines – in order not to lose their sought after decision-making authority. Even though they are not legally binding, guidelines can be the cause for rejecting individuals’ applications if the service applied for is not mentioned within the guidelines or if it exceeds the locally established level.

Although research on the design of local policy documents, such as guidelines, is scarce – the research on decision-making authority is scarcer. Recently, however, Van der Tier et al. (Citation2022) compared decision-making authority of social workers in three municipalities in Germany, Netherlands, and Belgium. The result showed that it varied between countries and resulted in social workers taking on different narratives aligning with different levels (state-agent and citizen-agent – resulting in them empowering or disciplining the citizens depending on their narrative). In Belgium for example, all decisions were made by the political board while the social worker had an advisory role. In Netherlands the social workers had a full mandate through decision-making authority about psycho-social assistance and economic benefits and in Germany they had decision-making authority over psycho-social assistance but not economic benefits. The result indicates varying structural conditions for the premises of social workers to exercise discretion depending on their local political context.

Predictability, equivalence, and universalism are other aspects of political policies. According to previous research within the field of social work, policies can be used to reduce variation that leads to inequality in the social service granted to older people. Political policies are used in Western democracies to reduce variation both within the same municipality as well as between municipalities, regions or nationwide (e.g. Boockmann et al., Citation2015; Rauch, Citation2008; Wittberg & Taghizadeh Larsson, Citation2021). This is not without reason. Several studies conclude that a less specified use of public resources brings forth a skewed distribution of resources between different groups in need (Sandkjær Hanssen & Helgesen, Citation2011; Szebehely & Trydegård, Citation2007). Individual’s varying access to services has also been shown to depend on the specific social worker’s view on deservingness of who is worthy or unworthy of public resources (Altreiter & Leibetseder, Citation2015; Maynard-Moody & Musheno, Citation2000).

Studies on the political design of local policy documents, and social work’s dependency thereon, are, however, relatively scarce in empirical social work research, especially on a systematic and nationwide scale. This is regrettable since the provision and funding of elder care in many well-developed welfare states is publicly administered, making social workers dependent on political decisions and priorities in their everyday work (Brodkin, Citation2021; Jensen & Lolle, Citation2013; Wittberg & Taghizadeh Larsson, Citation2021). This research gap is a manifestation of the lack of contextualisation within social work research, as addressed by Hupe and Buffat (Citation2014), where answers to micro behaviour are sought at the micro-level (individual characteristics or personal views) rather than at the meso or macro level (the structural and contextual setting). This means that the potential impact of the institutional setting is under-researched.

Against this backdrop, the overarching aim of this study is to examine how politicians exercise control through local policies, and to explore the framework and prerequisites for legal decision-making created by political policies on delegation. The policies determine care managers’ room for manoeuvre and their legal rights to make decisions about the welfare services given to older people. Motivated by the scarcity of research on social work practices’ relation to political policy documents, the purpose of this study is to highlight how local politics is embedded within social work practice.

This article maps and analyses the design of delegation within local political policies for decision-making about the needs and services provided to older people in Sweden’s 290 self-governing municipalities. Sweden is an interesting case for the purpose at hand since its social service, as in other Western European countries, is dependent on local funding, local political conditions and priorities. At the same time, the country is often described as a welfare state with universal services of national equivalence, while simultaneously being one of the most decentralised countries in Europe, which in turn opens up to variation between municipalities (Haveri, Citation2015; Jensen & Lolle, Citation2013; Ladner et al., Citation2016; Lunder, Citation2016).

Investigating local policy documents for delegation in this study can show whether politicians choose to transfer their legal decision-making authority. It further shows how politicians can exercise control by not giving or by conditioning the legal decision-making authority by giving different types of delegation. Care managers’ local prerequisites to make legal decisions about services to older people are thereby made visible. This paper can contribute to previous research by highlighting the importance of accounting for the structural political context and its consequences for frontline bureaucrats.

In contrast to most previous research (for an exception, see Van der Tier et al., Citation2022), this article focuses on legally binding documents, determining the boundaries for legally making decisions about welfare services (Government Bill, Citation1990/Citation91:Citation117), rather than supportive and guiding documents, such as local guidelines (see Erlandsson, Citation2018; Olaison et al., Citation2018). While there is no legal requirement to establish local guidelines (Government Bill, Citation2000/Citation01:Citation80) in order to employ care managers to assess and make decisions about welfare services – the establishment of a local delegation policy is required if care managers are to make decisions about the needs of older people (Local Government Act, Citation2017:Citation725 [LGA]; Government Bill, Citation1990/Citation91:Citation117). Hence while the role of local guidelines has been highlighted in previous research it is warranted to complement this knowledge with an increased understanding of the prevalence and design of local delegation policies.

The Swedish context and the right to make decisions about services for older people

Sweden is a welfare state with a social service funded by the public through taxes. In contrast to other parts of Europe, Sweden, as well as the other Nordic countries, has a higher degree of local autonomy concerning local political discretion, taxation, and policy scope (the range of functions for which the local level is responsible) (Ladner et al., Citation2016; LGA). Among other municipal tasks, the access of care for older people is a political matter at the municipal level (LGA; Social Service Act, Citation2001:Citation453 [SSA]). The LGA, according to which the local politicians act, states that all municipal citizens should be treated equally given that they have equal circumstances.

According to the LGA, local politicians are not only responsible for the design and provision of elder care but also ultimately decisive in individual cases. This means they are responsible for making decisions about older people’s access to services. This order of responsibility is a remnant from the mid-1900s (when Swedish municipalities were smaller, and politicians operated closer to locals) and has not been adjusted to the modern Swedish public sector with relatively few politicians and a large administration (Erlingsson et al., Citation2022; LGA). In the current century, however, the situation is different. For reasons of practicality and efficacy, local politicians are able to delegate the power of decision-making to civil servants, such as care managers (Government Bill, Citation1990/Citation91:Citation117). In contrast to the LGA, the Swedish SSA, according to which care managers operate, states that the individual has a right to an individual needs assessment and that granted services shall satisfy individually assessed needs (SSA). Consequently, the law specifies no limit to what older adults could be granted – as long as the services ensure the older person a ‘reasonable standard of living’ and a ‘dignified life’ – both of which call for expertise and knowledge about the law and praxes as well as biological, social, and psychological aging. In addition, shall economic interests not be considered during the needs assessment (except on a few occasions [Government Bill, Citation2000/Citation01:Citation80]).

Considering that all services granted by care managers are funded by public taxes, which local politicians are responsible for distributing, while at the same time upholding good financial housekeeping for the municipal finances, the relationship between politicians and care managers is crucial. Given their contradicting logic, conflicting interests can emerge between politicians and care managers. Politicians have stated that they have an information disadvantage compared to the administration and seek control over the large local administration (Erlingsson et al., Citation2022).

Since politicians are held accountable for elder care and the decisions made about it, they must also exercise control over municipal activities. Local politicians can therefore determine requirements for the delegation of decision-making authority, as well as demand reports on all decisions made by care managers as they are made in the name of the municipal board (or committee). The policy document and the assigned delegation, regulate and set the boundaries for the care managers’ legal capacity in the execution of work tasks. If care managers should exceed their legal right to act, the decision made is ‘non-existing’ – or not legally binding. Worth noting is that, even if a decision lacks legal support (which means that the care managers have violated their legal authority), the older adult, as receiver of the decision, can take the matter to court – provided that the person received the decision in good faith. By taking the matter to court, the municipality can be forced to implement the decision – depending on the legal outcome. Politicians cannot change decisions made with the support of delegation but can at any time reclaim the delegated power from the care managers overall, the overall delegation from a specific care manager, or the delegation regarding a specific case (Government Bill, Citation1990/Citation91:Citation117; Wenander, Citation2019).

The fact that it in Sweden is the municipal board that is decisive in individual cases is a problem that has been highlighted due to the risk of inappropriate political pressure on the public administration (considering the constitutionally protected forbid in Sweden against ministerial rule and political influence over decisions made by the administration at both the national, regional, and local level in Sweden). Political involvement in the decision-making process can create conflicting interests and jeopardise basic principles within the democracy, such as the principles of impartiality, lawfulness, and legal certainty (Erlingsson et al., Citation2022).

The need for efficiency while maintaining control – a principal–agent theory approach

An aspect often left out of adult social work research is care managers’ dependence on their principals (in this case local politicians), conditioning the professionals’ (agents’) freedom to act in order to minimise risks when delegating responsibility. As mentioned in the Swedish context, it would be too wide-ranging, time-consuming, and inefficient for local politicians to make all decisions about every older citizen applying for social services in the municipality. Instead, decision-making can be delegated, e.g. to a care manager, which can be seen as a tool for politicians to achieve goals and execute tasks.

The Principal Agent theory (PAT) concerns the relation between two actors when the responsibility to perform a task is delegated from one actor to the other (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). While the principal is the actor who delegates, the agent is the actor to whom power, and authority are delegated. According to PAT, delegating decision-making authority can create a principal–agent problem. This problem arises when a task is delegated from one actor (principal) to another (agent) and the actors have different interests and focus in executing the task, and when the agent has an information advantage over the principal. This is often the case with needs assessments within social services where meetings with older people are carried out away from supervision (Brodkin, Citation2011; Olaison et al., Citation2018), and where the SSA calls for an individual needs assessment regardless of other citizens and (more or less) of municipal economy. If care managers act according to their own agenda (contrary to politicians’ interests) while making decisions in the name of the municipal board, an agent cost arises, leaving the principal accountable for the agent’s actions. However, the agent’s interests need not be monetary or driven by a direct self-interest. Within social services, the agent’s actions may be altruistic, driven by professional judgement in the best interest of the clients, or a diverging idea on policy implementation based on field knowledge.

In order to handle the risks that diverging interests give rise to while delegating authority, the principal can control the agent (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). A common method of control is the design and implementation of policies that stipulate the principals’ ambition with regard to the delegated task at hand. Local policies for delegation, local guidelines, or statements of mission can be seen as examples of risk minimisation (e.g. Lunder, Citation2016; Wittberg & Taghizadeh Larsson, Citation2021).

To conclude, the principal–agent problem distinguishes an area rarely highlighted within social work research – the dependency of the relation between politicians and care managers, thereby contributing to a greater understanding of the organisational context surrounding practitioners at the ground level of social services.Footnote1 Considering the aim of this study, the principal–agent problem can contribute to an understanding of the relation between politicians and care managers as a two-way dynamic where they influence each other’s actions. Policy documents can thereby be seen as a way of embedding the politicians’ interest in social work practice.

Data and method

Data

The material analysed comprises local policy documents of delegation. The documents are designed and adopted by local politicians and determine the legal rights of care managers to make decisions about the welfare services given to older people according to the Social Service Act (SSA) in Sweden. Generally, the documents on delegation for care managers consisted of about one to three pages.

The documents of delegation, from 2019, were requested from and disclosed by all of Sweden’s 290 municipalities. Two municipalities had divided their political rule into 14 and nine, respectively, autonomous self-governing sub-municipal district councils, which are included in the study. The total amount of local policies in the study is therefore 311. The year 2019 was chosen because it is recent but before the Covid-19 pandemic and its potential effects on local politics and its documents.

Coding and analysis

The policy documents of delegation were mapped and coded for decision-making on all types of services within the municipal elder care mentioned in them.Footnote2 To begin with, a qualitative analysis was made as all delegation documents were read through, whereafter types of services were categorised and labelled for each municipality. Simultaneously, all services were coded by assigning different numbers for each type of delegation (see ). Within the delegation documents mainly the same name was used for services. When the name diverted the service mentioned was looked up in the municipality’s local guidelines in order to categorise the service the same way. An example of this is day care and daily activity both of which refer to the same service (categorised as day care). The category with the most internal differences was home care as this is a collective term for several smaller services carried out in the individuals home (e.g. cleaning, washing, showering, etc.). These were however mostly referred to as home care or help within the home (categorised as home care). In a few municipalities no specific services were mentioned – only ‘support for general living’ (SSA 4:1) for which delegation was given. These were coded as not restrictive, and as service not mentioned when coded for specific services. Finally, the analysis was complemented with a quantitative analysis for which Stata was used to calculate frequencies for restrictiveness in the overall delegation and for the main types of services within elder care. This is further explained below.

Table 1. Different types of delegation.

Five types of service (categorised as ‘main services’) within the elder care in Sweden are presented and analysed: residential care home, home care, temporary and reoccurring respite care,Footnote3 and day care. These services are chosen since they are the most commonly named services in the policies therefore indicating a high level of political interest and control. The ‘main services’ are also the most common services granted, the most extensive and expensive types of service, and several of them also function as a respite break for carers (SSA). Six types of delegation were identified – from no delegation to delegation (without limits) (see ).

To create an overview of the total restrictiveness of delegation for care managers to make decisions, the data for each municipality and district council was coded into the variable main services (restricted/not restricted) regarding restrictiveness in any of the five main services and overall delegation for restrictiveness for all mentioned services. The data for each municipality and district council for overall delegation was coded into restricted delegation (delegation type 1–5) and not restricted (delegation type 6–7) (see ). The results are presented as descriptive statistics of all 311 local policies for delegation.

Results

Initially the restrictiveness for delegation overall and for the five main services in the country as a whole will be presented. This is followed by a presentation of the different types of control strategies that have been identified in the study: no delegation, delegation according to guidelines, delegation after consultation and levels of delegation.

Restrictiveness and types of delegation for elder care services in Swedish social services

The results reveal that local politicians exercise varying control over care managers’ discretion in social work practice. According to the results (see ) care managers’ discretion for decision-making about the needs of older people are limited, in delegation documents, in more than half of Sweden’s municipalities, regardless of whether it concerns the overall service (62.4%) or one of the five main types of service (53.4%).

Table 2. Restrictiveness in delegation in the Swedish social services for older people – overall and for the main types of service (home care, residential care, temporary respite care, reoccurring respite care and day care).

Irrespectively of other factors (such as organisational structure, managers, etc.) which impact on professional care managers, the basic need for delegation in order to function autonomously and use professional competence seems highly unpredictable in Sweden and calls for further analysis. For instance, do politicians restrict and control certain types of services more than others? According to the results here, this seems to be the case. Care managers’ delegation for making decisions about respite to carers of older people (day care and reoccurring respite care), are, for example, less restricted in comparison to other services, such as residential care homes, the decision-making authority about which is more restrictive. In 2019, care managers in every fifth (22.8%) municipality in Sweden did not have any delegation to make decisions about residential care homes (see ).

Table 3. Types of delegation for making decisions about the five main types of social services.

This can be seen as a consequence of two conflicting goals for local politicians, who on the one hand seek to maintain control over local resources and distribution of services, while on the other hand need to delegate decision-making in order to create efficiency and better municipal services. If care managers act contrary to the politicians’ interests while making decisions about residential care homes, this restrictiveness can, however, be motivated. Considering that residential care homes claim more resources compared to other services and lay claim to available apartments in residential care homes,Footnote4 the risk in delegating is higher for the principal.

In view of this, further shows not only how frequently politicians restrict care managers’ discretion for certain types of decisions (such as those concerning residential care homes and temporary respite care), but also the palette of strategies used by politicians for maintaining control over decisions made, and how. The four main strategies used are: no delegation, delegation after consulting a manager, delegation according to guidelines and delegation up to a certain level. Although it is more common (than for the other four types of main services) that politicians choose not to delegate decisions about residential care home services to care managers (22.8%), other strategies are more common for other types of services.

The strategy of giving delegation according to local guidelines is most common for home care service (15.1%). This could be explained by the fact that home care service has larger internal variation compared to other types of services (such as day care or reoccurring respite care) as it is a collective term for all sorts of service given in the individuals’ home (hygiene, cleaning, food, social activity, etc.) (see Wittberg & Taghizadeh Larsson, Citation2021). By using this form of indirect control, politicians are still able to delegate a substantial portion of decisions in order to focus their own attention on other political matters. This can be seen as a complementary way of ensuring care managers comply with and follow the politicians’ instructions and goals. Even though following guidelines increase professionals’ discretion, in comparison to having no delegation at all, it also means that the care managers’ prerequisites and their freedom to act are highly conditioned by the design of the local guideline policies.

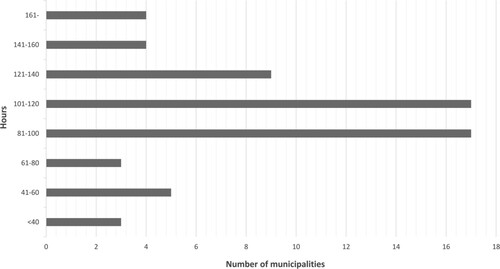

Another potential way of controlling the profession, not letting the care managers follow their self-interest or use their professional knowledge, is by allowing discretion to make decisions in terms of time-limits for service granted, e.g. up to a certain level. The levels consist, for example, of a certain number of hours of home care per month or respite care for a certain number of days or weeks. Even though care managers in approximately 20% of municipalities (see ) in Sweden are limited in deciding the total number of hours for home care, the number of hours they can grant varies considerably according to the policy documents (see ). While most of the municipalities have set the limit between 81 and 120 h, the highest number of hours is 300 h per month. The lowest is 40 h per month.

Figure 1. Care managers’ level of delegation for home care services. Comment: Interval of hours as levels of delegation for the decision-making by care managers about home care services for older people. In total 62 municipalities in Sweden (approximately 19.9%) have chosen to use number of hours to limit discretion.

The variation of delegated levels indicates different political needs for control and creates varying prerequisites for care managers depending on where they work. Forty hours per month leaves only a limited room for manoeuvre and use of professional expertise in order to ensure older people a reasonable standard of living and a dignified life.

The least used of the strategies is delegation after consultation. This strategy can be viewed as a middle path between not giving delegation and delegation according to guidelines both of which most likely call for follow-ups and further attention from politicians or managers. It does however call for a manager close at hand to deliberate the case with, in order to make a quick decision for e.g. temporary respite care – for which this form of delegation is most common (3.2%). Delegation after consultation enables politicians to maintain control by entrusting only one (or a few) people with decision-making authority to make decisions in line with the political will.

Noteworthy is not only the result showing different types of delegation but that different types of delegation are (more frequently) used for certain types of services indicating a deliberate strategy for control depending on the service. Seen in light of the principal–agent theory this can be understood as controlling economic expenses while balancing between the advantages of not maintaining control (efficiency, more time for other tasks, higher degree of expertise, etc.) and the costs of maintaining control (more tasks for managers or politicians, controls of compliance to guidelines, lower efficiency, lower degree of expertise, etc.).

Discussion

By analysing local political policies for delegation, this study shows how the strategies for delegating authority, granting social services to older people, and maintaining political control vary between Swedish municipalities. Viewed as a principal–agent problem, the varying conditions for care managers’ legal decision-making confirm the importance of studies investigating the structural setting to understand micro behaviour.

Not only does the study reveal that just around half of the municipalities have delegation without restrictions for the five main types of services, but it also reveals varying delegation strategies, upholding a certain extent of control for politicians. For instance, delegation conditioned by consultation with a manager is a complex strategy for maintaining control since the politicians can appoint a head of the local Social Services loyal to their policies. This makes care managers vulnerable to political pressure since a shift in political rule can result in a turnover of managers and changes in policies (Erlingsson et al., Citation2022). As pointed out by Evans (Citation2011, Citation2013), the care managers’ professional use of discretion is not only dependent on their relation to their managers but also dependent on the managers’ competence and rule-compliance attitude. Managers with less ambition for control and who are willing to take risks in relation to local politicians will leave care managers with more discretion.

Delegation according to guidelines, on the other hand, directs care managers to follow more detailed instructions and goals. Although delegation according to guidelines increases professionals’ discretion compared to not having delegation, it also means that the care managers’ options and freedom to act are highly conditioned by the design of the local guideline policies. As shown by previous research, the design and quality of local guidelines vary considerably between municipalities in Sweden (Wittberg & Taghizadeh Larsson, Citation2021).

A key finding in this study, seen in light of the principal–agent problem, is how the profession’s role can be understood as an extended arm of politics. By understanding the potentially conflicting interests and different roles of politicians and care managers as a principal–agent problem, the extent and type of delegation emerges as the result of a complex relation in interaction. Although social services are governed and dictated by local conditions and politicians (Brodkin, Citation2021; Haveri, Citation2015; Jensen & Lolle, Citation2013), the principal–agent problem is underused as a theoretical framework within social work research. An exception is a study by Carson et al. (Citation2015), who discuss the principal–agent problem in view of discretion within social work practice. They argue that the agents’ task does not solely consist of carrying out the principals’ instructions but rather tailoring those instructions according to a wide range of competing requirements and conditions, for example, making social workers, such as care managers, policy-creating actors (see also Brodkin, Citation2011). However, these arguments do not account for the legal boundaries for action nor the consequences for care managers acting outside their delegated authority and legal rights, but rather see the profession as an active negotiator and co-creator of policy. It is based on a discussion about policies in more general terms, rather than legally binding documents. The distinctive differences between the types of documents are essential. While guidelines, without a connection to delegation, can be a mere supportive document clarifying how the law (SSA) can be interpreted (Erlandsson, Citation2018), delegation policies are an authorisation of the professional’s legal authority to make decisions in the name of the political board (Government Bill, Citation1990/Citation91:Citation117). This does not however rule out that most types of delegation, apart from not having delegation, leaves some discretion towards making a certain decision (as shown by Olaison et al., Citation2018 concerning guidelines). This can be done either by interpreting criteria in guidelines or by framing an individual’s needs in a favourable manner for the individual – making the person eligible for specific services. Here levels of delegation stand out since it leaves room for manoeuvre as long as the level (of hours, days, weeks, etc.) is not exceeded. On the other hand, once the level is passed – the delegation authority for further services to the specific individual in need can be considered as ceased (as in having no delegation). This can leave the care managers with less discretion than with delegation according to guidelines or consultation with a manager. No delegation is thereby the ultimate limitation of discretion for making decisions about the needs of older people as well as for an autonomous profession. As pointed out by Nilsson (Citation2016) the threat of losing delegation can be a reason for Swedish care managers’, commonly questioned and criticised (Dunér, Citation2018; Olaison et al., Citation2018), compliance with soft governance tools, such as local guidelines. This study shows that the professionals’ discretion is far more complex than previously assumed and that the political context and the distinction between different types of policies needs to be taken into account while studying professionals’ behaviour within the social work practice.

Results from Carson et al. (Citation2015) pinpoint the principals’ need for control by reducing variation between agents, depending on their personal views on deservingness or individual needs (see also Altreiter & Leibetseder, Citation2015; Evans, Citation2013). Considering that previous research shows that care managers do not always accept and comply with organisational rules, politicians’ potential need for control emerges. It can be understood both in light of the LGA’s demand for citizens to be treated equally as well as the risk for arbitrariness if care managers create unofficial norms and praxes for who is worthy or unworthy (see Altreiter & Leibetseder, Citation2015; Brodkin, Citation2011). In view of this, the policies can be seen as a control function in creating legal certainty through predictability and avoiding arbitrariness.

One limitation of this study is that no conclusion can be drawn on how care managers experience delegation documents, how they are enforced in practice, nor can it clarify which services are granted due to varying local policies on delegation. This calls for further research. Furthermore, research with a comparison between municipalities with different types of delegation, between developed welfare states, or between professional groups of frontline bureaucrats within different parts of social work practice (see also Maynard-Moody & Musheno, Citation2000) is called for.

Considering that the delegation policies are designed and established by local politicians, one relevant question for further studies is whether varying restrictiveness of delegation result from different political majorities with a diverse political orientation towards the social service. Furthermore, it is called for to examine whether there could be a connection between restrictive local policies for granting social service such as elder care and the overall decline in the welfare eligibility of older people, especially in Sweden and Finland, but also in the other Nordic countries (Ranci & Pavolini, Citation2015; Szebehely & Meagher, Citation2018). A working hypothesis for further research could be that the decline of welfare eligibility is connected to the enforcement of local political policies, such as local guidelines (delimiting the municipal responsibility, advising care managers to depart from their legal assignment, etc. [see Wittberg & Taghizadeh Larsson, Citation2021]), – especially when enforced by local policies for delegation.

Conclusion

The results of this study reveal that the legal decision-making authority afforded to care managers within the social services varies considerably between municipalities in Sweden. The results underline social works’ dependency on local politics and highlights the politicians’ perceived need for controlling the distribution of services through different delegation strategies. In withholding delegation, limiting care managers’ legal right to make decisions about services to older people, the profession is made dependent on the organisation, thereby contributing to a less independent profession.

The focus within previous research (Dunér, Citation2018; Olaison et al., Citation2018) on the responsibility of professional care managers to liberate themselves from their organisational context can be seen in a different light when understood as a principal–agent problem. By unveiling and understanding care managers as agents and their prerequisite for decision-making as a politically delegated responsibility, the profession is made visible as the extended arm of politics – essentially set to perform tasks on behalf of the municipal board (or committee). In making visible the current processes and situation for the profession, a more informed discussion about what the role of care managers is, or should be, can be had. When seen as agents performing tasks on behalf of local politicians, care managers’ role and discretion within the welfare system are brought to question. This study points towards important implications for social work practice as the loss of legal decision-making authority risks reducing educated social workers to administrators or advisors (see Van der Tier et al., Citation2022).

This study contributes s to the field by studying larger contextual settings within a political framework and with legally binding documents. The results stress the need for further comparative research to better understand what happens at the ground level of the public sector. By unveiling the Swedish context, this paper highlights the importance of context, as argued by Hupe and Buffat (Citation2014). In line with Van der Tier et al. (Citation2022), this study stresses that more knowledge is needed to understand how premises and actions at the micro-level are formed by meso and macro level decisions.

Ethical considerations

Since the study relies on public municipal material, according to the Swedish Freedom of the Press Act (Citation1999:Citation105), there was no need for ethical approval.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for comments by Lars-Christer Hydén, Joy Torgé, Gissur Ó Erlingsson, Nicoline Roth, Annika Taghizadeh Larsson, Anna Olaison, Susanne Kelfve, and seminar attendees at Stockholm Gerontology Research Centre.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sara Wittberg

Sara Wittberg is a PhD candidate and a trained social worker with long experience as a care manager, assessing the needs of older people. Her research is focused on the local provision of welfare services. More specifically, she studies local interpretations of the Swedish national law through the design of local guidelines as well as local policies for decision-making authority for assessing and providing elder care services.

Notes

1 The PAT is often criticized for assuming rationality and that agents would act in favour of their own interests by maximising the utility of the administrations’ services according to their own agenda (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976). The aspect of maximising utilities is not in focus here but rather that actors, like politicians and care managers, can have different interests, and how this risk can be minimised through control.

2 A criteria was that the service should be enforced within the municipality in question.

3 Temporary respite care is a temporary accommodation with 24-hours personal care and support for older people in need of care for a shorter period of time. Reoccurring respite care is used as respite break for carers. The older adult in need of help lives in an accommodation, like temporary respite care, for 1 or 2 weeks/month, reoccurring.

4 Possibly resulting in penalty fees from the Swedish Health and Social Care Inspectorate if the decision is unenforced after 3 months.

References

- Altreiter, C., & Leibetseder, B. (2015). Constructing inequality: Deserving and undeserving clients in Austrian social assistance offices. Journal of Social Policy, 44(1), 127–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279414000622

- Boockmann, B., Thomsen, S. L., Walter, T., Gobel, C., & Huber, M. (2015). Should welfare administration be centralized or decentralized? Evidence from a policy experiment. German Economic Review, 16(1), 13–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/geer.12021

- Brodkin, E. Z. (2011). Policy work: Street-level organizations under new managerialism. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 21(2), i253–i277. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muq093

- Brodkin, E. Z. (2021). Discretion in the welfare state. In T. Evans & P. Hupe (Eds.), Discretion and the quest for controlled freedom (pp. 63–78). Palgrave MacMillian.

- Carson, E., Chung, D., & Evans, T. (2015). Complexities of discretion in social services in the third sector. European Journal of Social Work, 18(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2014.888049

- Dunér, A. (2018). Equal or individual treatment: Contesting storylines in needs assessment conversations within Swedish eldercare. European Journal of Social Work, 21(4), 546–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2017.1318831

- Eisenhardt, M. K. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. The Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/258191

- Erlandsson, S. (2018). Individuella bedömningar eller standardiserade insatser? Kommunala riktlinjers roll i biståndshandläggares arbete [Individual assessments or standardised services? Municipal guidelines’ role in care managers’ work]. In H. Jönson & M. Szebehely (Eds.), Äldreomsorger i Sverige. Lokala variationer och generella trender (pp. 43–58). Gleerups.

- Erlingsson, GÓ, Karlsson, D., Wide, J., & Öhrvall, R. (2022). Demokratirådets rapport 2022: Den lokala demokratins vägval [The Council of Democracy Report 2022: The choice of path for the local democracy]. SNS Förlag.

- Evans, T. (2011). Professionals, managers and discretion: Critiquing street-level bureaucracy. British Journal of Social Work, 41(2), 368–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcq074

- Evans, T. (2013). Organisational rules and discretion in adult social work. British Journal of Social Work, 43(4), 739–758. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcs008

- Government Bill. (1990/91:117). Om en ny kommunallag [About a new local government act]. Regeringen.

- Government Bill. (2000/01:80). Ny socialtjänstlag m. m [A new social service act etcetera]. Regeringen.

- Haveri, A. (2015). Nordic local government: A success story, but will it last? International Journal of Public Sector Management, 28(2), 136–149. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-09-2014-0118

- Hupe, P., & Buffat, A. (2014). A public service gap: Capturing contexts in a comparative approach of street-level bureaucracy. Public Management Review, 16(4), 548–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2013.854401

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Jensen, P. H., & Lolle, H. (2013). The fragmented welfare state: explaining local variations in services for older people. Journal of Social Policy, 42(2), 349–370. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279412001006

- Ladner, A., Keuffer, N., & Baldersheim, H. (2016). Measuring local autonomy in 39 countries (1990–2014). Regional & Federal Studies, 26(3), 321–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597566.2016.1214911

- Lunder, T. E. (2016). Between centralized and decentralized welfare policy: Have national guidelines constrained the influence of local preferences? European Journal of Political Economy, 41, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.11.003

- Maynard-Moody, S., & Musheno, M. (2000). State agent or citizen agent: Two narratives of discretion. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 10(2), 329–358. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024272

- Nilsson, J. (2016). Med makt följer ansvar – Socialtjänstens myndighetsutövning inom LSS och hemtjänst (report IVO 2016–30) [With power comes responsibility; the social services’ exercise of public authority within services for persons with certain functional impairments’ (1993:387) and home care service]. Inspektionen för vård och omsorg [Health and Social Care Inspectorate – IVO].

- Olaison, A., Torres, S., & Forssell, E. (2018). Professional discretion and length of work experience: What findings from focus groups with care managers in elder care suggest. Journal of Social Work Practice, 32(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2018.1438995

- Ranci, C., & Pavolini, E. (2015). Not all that glitters is gold: Long-term care reforms in the last two decades in Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 25(3), 270–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928715588704

- Rauch, D. (2008). Central versus local service regulation: Accounting for diverging old-age care developments in Sweden and Denmark, 1980–2000. Social Policy & Administration, 42(3), 267–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2007.00596.x

- Sandkjær Hanssen, G., & Helgesen, M. K. (2011). Multi-level governance in Norway: Universalism in elderly and mental health care services. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 31(3), 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443331111120609

- SFS. (1999:105). Tryckfrihetsförordningen. Justitiedepartementet [Freedom of the Press Act].

- SFS. (2001:453). Socialtjänstlag. Socialdepartementet [Social Services Act].

- SFS. (2017:725). Kommunallag. Finansdepartementet [Local Government Act].

- Szebehely, M., & Meagher, G. (2018). Nordic eldercare – Weak universalism becoming weaker? Journal of European Social Policy, 28(3), 294–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717735062

- Szebehely, M., & Trydegård, G.-B. (2007). Omsorgstjänster för äldre och funktionshindrade: skilda villkor, skilda trender? [Care services for the elderly and for disabled persons: Different conditions, different trends?]. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 2–3, 197–219.

- Van der Tier, M., Hermans, K., & Potting, M. (2022). Social workers as state and citizen-agents. How social workers in a German, Dutch and Flemish public welfare organisation manage this dual responsibility in practice. Journal of Social Work, 22(3), 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/14680173211009724

- Wenander, H. (2019). Olagligt, olämpligt, ogiltigt: Förutsättningar för prövning av nulliteter i svensk förvaltningsrätt [Illegal, inappropriate, invalid: Prerequisites for trial of non-existing decisions within Swedish administrative law]. In H. N. Tøssebro (Ed.), Ugyldighet i forvaltningsretten (pp. 112–125). Universitetsforlaget.

- Wittberg, S., & Taghizadeh Larsson, A. (2021). Hur avgränsas det kommunala ansvaret för att tillgodose äldres behov i kommunala riktlinjer? [How do local guidelines delimit the municipal responsibility to meet the needs of older people?]. Socialvetenskaplig tidskrift, 28, 269–288.