ABSTRACT

Transitions in gerontological social work are poorly theorised and underresearched. Although social workers are routinely involved in transitions of older people into care homes, they tend to be treated as a functional transition from one place to another rather than as a social, emotional and psychological process for the older person and their family. Evidence suggests that a healthy transition is more likely if the older person has exerted some influence over the ‘when’, ‘where’ and ‘how’ of the decision, continuity between the ‘old life’ and the ‘new’ is maintained, and their concerns are acknowledged. Drawing on a theory of transition developed by Melies et al. (2000), this paper argues that social workers have the relational, communication and advocacy skills, as well as legal literacy and a rights-based perspective, to help to promote healthy transitions. There is considerable potential to develop, and evidence the value of, social work’s contribution to this often marginalised area of practice.

TIIVISTELMÄ

Siirtymät (transitiot) ovat gerontologisessa sosiaalityössä huonosti teoretisoituja ja vähän tutkittuja. Vaikka sosiaalityöntekijät ovat mukana iäkkäiden ihmisten siirtymisessä asumispalveluihin, siirtymiä tarkastellaan usein fyysisenä siirtymisenä paikasta toiseen eikä iäkästä ihmistä ja hänen perhettään koskettavana sosiaalisena, emotionaalisena ja psykologisena prosessina. On näyttöä siitä, että ‘terveellinen siirtymä’ on todennäköisempää, jos iäkäs ihminen on voinut vaikuttaa siihen, milloin, missä ja miten hän tekee päätöksen, jos ‘vanhan elämän’ ja ‘uuden elämän’ välinen jatkuvuus säilyy ja jos iäkkään ihmisen ajatukset ja huolet otetaan huomioon.

Tässä artikkelissa esitetään Melies’in ja muiden (Citation2000) kehittämän siirtymäteorian pohjalta, että sosiaalityöntekijöillä on suhde-, kommunikaatio- ja vaikuttamistaitoja sekä juridista ja iäkkään oikeuksiin liittyvää osaamista, joiden avulla he voivat edistää ‘terveellistä siirtymää’ asumispalveluihin. Sosiaalityön panosta on mahdollista kehittää huomattavasti tällä usein marginaaliin jäävällä työn alueella tuomalla esiin sosiaalityön merkitys ja arvo siirtymisen prosessissa.

ABSTRACT

Il tema delle transizioni nel lavoro sociale con le persone anziane è poco teorizzato e studiato. Nonostante gli assistenti sociali siano coinvolti di consueto nelle transizioni delle persone anziane in struttura protetta, questi passaggi tendono ad essere considerati come una transizione funzionale da un luogo a un altro, piuttosto che un processo che incide sul piano sociale, emotivo e psicologico per le persone anziane e le loro famiglie.

Le evidenze di ricerca suggeriscono che è più probabile realizzare una sana transizione se le persone anziane hanno esercitato una certa influenza sulla decisione riguardo al ‘quando’, al ‘dove’ e al ‘come’, se è mantenuta continuità tra la ‘vecchia vita’ e quella ‘nuova’ e se le loro preoccupazioni sono riconosciute. Basandosi su una teoria della transizione sviluppata da Melies et al. (Citation2000), questo articolo sostiene che gli assistenti sociali dispongono delle capacità relazionali, comunicative e di advocacy, così come delle competenze legali e di una prospettiva fondata sui diritti, necessarie per promuovere una sana transizione. Esiste un notevole potenziale per sviluppare l’apporto del servizio sociale in questa area di pratica spesso poco considerata, e per dimostrarne il valore.

REZUMAT

Tranzițiile în asistența socială gerontologică sunt slab teoretizate și insuficient cercetate. Deși asistenții sociali sunt implicați în mod obișnuit în tranzițiile persoanelor în vârstă către centrele de îngrijire, vârstnicii tind să fie tratați mai degrabă ca fiind intr-o tranziție funcțională de la un loc la altul decât ca parcurgând un proces social, emoțional și psihologic pentru ei și familia lor. Dovezile sugerează că o tranziție sănătoasă este mai probabilă dacă persoana în vârstă a exercitat o anumită influență în decizie, asupra aspectelor referitoare la: ‘când’, ‘unde’ și ‘cum’, dacă se menține continuitatea între ‘viața anterioară’ și ‘ cea nouă’ și dacă preocupările ei sunt recunoscute. Bazându-se pe o teorie a tranziției dezvoltată de Melies și colab., (Citation2000), această lucrare susține că asistenții sociali au abilitățile relaționale, de comunicare și de advocacy, precum și alfabetizare juridică și o perspectivă bazată pe drepturi, pentru a ajuta la promovarea tranzițiilor sănătoase a persoanelor vârstnice în centre. Există un potențial considerabil de a dezvolta și de a dovedi valoarea contribuției asistenței sociale la acest domeniu de practică, adesea marginalizat.

Introduction

This paper will explore how social workers can help to facilitate a healthy transition for older people permanently admitted to a care home, and their family carers (carers) (see Box 1). Using a particular conceptual model (discussed later) we make the case for social work engagement with the transition process and why it is important. We draw on evidence from five European countries: the UK, Ireland, Romania, Finland, and Italy as these countries share policy contexts. The authors are University academics and are members of the European Social Work Research Association’s Special Interest Group for Gerontological Social Work.

Box 1: A note about terminology

Care homes refer to all types of institutional settings that offer 24-hour accommodation and care to older people, including nursing homes, residential care homes, and specialist dementia care homes.

Family carers will be referred to as carers (not caregivers)

Older people refers to people aged 65 years and over (unless otherwise stated)

We are looking at the transition of an older person from the community or hospital, into a care home not from one care home to another or from a care home to a hospice (or other setting).

Context: older people and care homes

There are a range of policy imperatives across Europe that encourage older people, including those with care and support needs, to remain in their own homes. The aims of ‘ageing in place’ policies chime with a related policy aspiration to reduce admissions to care homes and contain welfare costs (Luker et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, a small but significant proportion of older people do move into a care home every year in all of our five countries (see ). The risk of admission rises steeply amongst the very old. The majority of care home residents are women aged 85 years or over: most have multiple health problems; have previously lived alone, are single, widowed, or divorced; and are poor or dependent solely on public (welfare) benefits (Dening & Milne, Citation2021).

Table 1. Care home profile.

It is important to recognise that data from our five countries is collected and collated in different ways and that ‘care homes’ are defined and organised differently too (Aaltonen, Citation2015). It is noteworthy that admissions are lower for Italy and Romania. This can be explained by a combination of powerful cultural expectations that ‘the family’ will provide care, that welfare benefits incentivise community-based care options, the provision of home care services via the (free) health system, and the fact that in both countries the cost of residential care is very high. Despite these differences, key trends can be discerned, and patterns identified.

Risk factors and triggers

Risk factors and triggers take a number of forms.

Being in a hospital has been identified as a Europe-wide risk factor for admission to a care home although pathways into care are poorly understood. In Finland, the risk of admission from the hospital is double that of a community-based older person and, in Ireland, this is the case for nearly two-thirds of admissions (Health Service Executive, Citation2022). The profile of those admitted from the hospital is clinically distinct; this population tends to be very dependent, frail and to have recently experienced a stroke, fracture and/or significant mental illness (Burton et al., Citation2022; Harrison et al., Citation2017).

Care home residents have become markedly more dependent over time. In the UK, 80% of care home residents have dementia and/or hearing impairment; a significant proportion have depression and are frail, in pain and/or incontinent (Dening & Milne, Citation2021). At the point of admission, residents often have complex co-morbid conditions and unpredictable clinical trajectories (Forder & Caiels, Citation2011). This shift reflects the emphasis on community-based care noted above as well as the rising costs of care home fees across Europe. There is now greater reliance on residents paying their own fees,Footnote1 either wholly or partially; this is the case in three of our sample e countries – the UK, Ireland and Romania. Paying for ‘extras’ such as outings and hairdressing services is common in all five.

The death of a caring spouse or partner is a well-established trigger for admission (Nihtilä & Martikainen, Citation2008). A recent eight-country study identified caregiver burden as the ‘most consistent factor’ associated with a move to a care home (Verbeek et al., Citation2012). As the challenges of caring interleave with the needs of the older person social workers are often required to balance perspectives. Care home admission is a product of the needs of the cared for person and the needs and capabilities of the carer, who may themselves be older and have their own health problems. Living alone with no support from a family carer is a risk factor for admission at an earlier stage in the illness trajectory (Toot et al., Citation2017)Footnote2.

Other risk factors relate to the older person’s context. There is evidence, for example, that older people who are poorly socially connected are at greater risk of admission than those who are enmeshed in their community and/or have links with family members and friends (Hanratty et al., Citation2018). Unsurprisingly ‘inappropriate’ housing including: no or limited adaptations to accommodate mobility restrictions; draughty and inaccessible rooms; no or very expensive heating options; and poor bathroom facilities, is also a risk factor (Hoogerduijn et al., Citation2012).

For older people living with dementia, the ability to maintain independence in activities of daily living has consistently been identified as a protective factor across Europe (Verbeek et al., Citation2012). A systematic review of evidence (Toot et al., Citation2017) concluded that it is, commonly, a combination of the following issues that constitute ‘risk’ rather than a single issue: the person’s individual characteristics; the ability and willingness of carers to provide support; the availability and quality of support services; and the suitability of the person’s living environment (Covinsky et al., Citation2003; Hoogerduijn et al., Citation2012; Kauppi et al., Citation2018).

Transition into a care home

There can be no doubt that moving to a care home is a significant transition for an older person often precipitated by critical events, such as a fall, over which s/he has little control. It is likely to be their last place of residence. Admission tends to be associated with the loss of a number of long-established continuities and attachments such as: a home the older person may have lived in for many years, belonging to a community or neighbourhood, relationships, pets and personal possessions (Lundgren, Citation2000; Sullivan & Williams, Citation2017).

Transitions, especially from hospital, are managed in variable and inconsistent ways (Kable et al., Citation2015). It is well documented that unsupported transitions can have a negative impact on an older person’s wellbeing (Goodman et al., Citation2017). Adverse reactions, such as feeling like an ‘outsider’ or social disengagement, are associated with heightened risks of depression. Deterioration in health and wellbeing, loss of identity and sense of agency, and reduced connectivity with family and friends are common experiences (Fitzpatrick & Tzouvara, Citation2019).

Evidence strongly suggests that moving into a care home is much more than a physical transition from one environment to another; it involves profound psychological and emotional changes too (Sullivan & Williams, Citation2017). As noted, admission is likely to be preceded by at least one significant loss or change; these often co-occur giving the older person limited time to adjust. If an older person moves into a care home as an ‘emergency’ – for example from an acute hospital – they are likely to feel they have very limited control over the decision. Their physical, emotional, practical and social resources are also likely to be severely depleted.

Before exploring the nature and dimensions of a ‘positive’ or ‘healthy’ transition into a care home it is useful to discuss the concept of transition itself.

Transitions: concept and models

A transition results in fundamental changes to an individual’s role, sense of self, and/or identity (Melies et al., Citation2000). For a change to be described as ‘a transition’ it must be of sufficient magnitude and/or represent a ‘major life event’ requiring a person to develop alternative ways of managing their life or viewing their world. In the nursing literature – where ‘transitions’ have received much more attention than social work – the accepted definition is, ‘a passage from one life phase, condition or status to another, a multiple concept embracing the elements of process, time span and perception’ (Meleis, Citation2010, p. 25; Schumacher & Meleis, Citation1994).

Referring to the work of van Gennep, Tanner et al. (Citation2015) suggest that a transition involves stages that are connected to moving from one status to another as well as, often, from one place to another. Van Gennep highlights the importance of liminality: the experience of feeling ‘betwixt and between’. He identified three types of ‘liminal rites’: pre-liminal rites in which the individual is removed from her/his social situation; liminal rites in which s/he is in limbo; and post-liminal rites in which s/he adjusts to a new social status. The process also involves three types of transitional experience for example, relinquishing earlier but still valued roles, ideas, and practices; creating or discovering new adaptive ways of ‘acting’ and of ‘being’; and coping with the changed conditions (Ambrose, Citation2018).

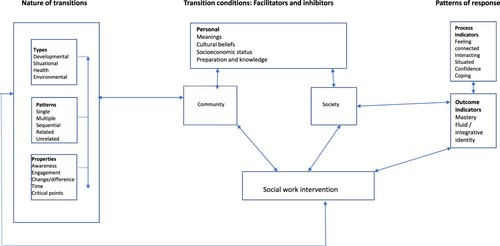

Originally utlised by the nursing profession, Melies et al. (Citation2000) developed a typology of transition which reflects the complexity and multidimensionality of a transition experience. Subsequent application of the typology to several health-related transition projects led to the development of a theory of transition (see ). Underpinned by an ecological approach, it offers a useful framework for social workers whose role often intersects with the lives of older people at the point of transition. The theory highlights:

Triggers or antecedents which make transition more likely

Types and patterns of transition (for example, health/illness, environmental, situational)

Properties of a transition experience (for example, temporality with no predetermined end point)

Factors which inhibit or facilitate progression towards a healthy transition (for example, accessing reliable information, opportunities to prepare)

Patterns of response comprising process indicators (for example, developing confidence, coping) and outcome indicators (for example, mastery, identity development/reformulation).

Figure 1. Transition theory (adapted from Melies et al., Citation2000).

Melies et al. (Citation2000) highlight the importance of understanding the experiences of the individual, and their family, during the transition. This necessitates understanding personal and environmental (individual, community and societal) conditions that facilitate, or constrain, progress towards achieving a healthy transition. Research suggests that the focus of most interventions relating to transitions is on the management of the physical transition rather than its emotional and psychological dimensions and the multiplicity of factors that influence the overall experience (Tanner et al., Citation2015). A ‘service focused transition’ risks prioritising practicalities and meeting the needs of the agency. Older people are subjected to ‘assessments of risk’ or ‘need’ and decisions tend to be driven by organisational pressures such as ‘delayed discharges’ rather than anything relating to the older person’s perspective or wishes.

Melies et al. (Citation2000, p. 26) argue that a healthy transition is determined by the extent to which a person can demonstrate mastery of the skills needed to manage their new situation and the ability to reformulate a new sense of identity. Feeling confident about the rhythms and culture of the care home, being able to accept support, and understanding the challenges of ‘collective’ care are examples of issues over which mastery can be developed. A healthy transition is a process which happens over time, not in a single moment. This reflects the complexities of psychologically working through what has been lost and what can be preserved and adjusting to the likelihood that factors such as health and care needs, social connections and personal resources have changed and may well continue to change.

The shape and nature of a healthy transition into a care home

A healthy transition can facilitate a number of positive outcomes for an older person including improved health and wellbeing, better social connectivity, and increased feelings of security, comfort, and safety (Fitzpatrick & Tzouvara, Citation2019; O’May, Citation2007). Research evidence from Europe, as well as the USA, Australia and Canada, suggests that a number of factors contribute to, or undermine, the achievement of a healthy transition. In this section, we explore this evidence through the lens of Melies et al.’s (Citation2000) model. We also reflect on the extent to which the dimensions of healthy transitions are, or could be, achieved for older people.

Personal conditions

Preparation, knowledge, and maintaining choice and control

A healthy transition is more likely if the older person exercises some control over the decision, retains an element of choice and is accorded agency (O’Neill et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Ryan & McKenna, Citation2015). For people living with dementia, it is important that the reason for moving into the home is fully explained (Sury et al., Citation2013). Other contributory factors include the support they receive throughout the decision-making process and pre-admission planning such as visiting the home and meeting the staff (Cole et al., Citation2018). Lee et al. (Citation2013) identified the importance of a ‘trial period’. For people living with dementia outcomes relating to well-being and ‘feeling settled’ are improved if s/he is allocated a ‘buddy’ for the first 48 hours of their stay (Sury et al., Citation2013).

However powerful the evidence is, significant challenges exist in achieving these aims in practice (Harrison et al., Citation2017). Choice can be severely constrained by care home availability – which varies significantly by country and area – and also by what the older person and/or their family can contribute financially. Choice, and engagement in decision making, is often much more limited for older people who rely on public (state) funding than it is for those who self-fund. Decisions about when an older person is admitted to a care home, and which home they move into, tend to be made by professionals, including social workers (Scheibl et al., Citation2019; Thetford & Robinson, Citation2006). People living with dementia are routinely excluded from decision-making on the grounds that they ‘lack capacity’ (Donnelly et al., Citation2018; Larsson & Österholm, Citation2014). Budgetary considerations are a primary driver. There is an inherent contradiction between the policy rhetoric of choice and a system driven by cost efficiencies (Reed & Stanley, Citation2006).

Overall, the opportunity for an older person to exert some influence over the ‘when’, ‘where’ and ‘how’ of the transition is consistently evidenced as positive. A healthy transition is much more likely in contexts where an older person has either chosen to move into a care home themselves or has been meaningfully involved in the decision (Gilbert et al., Citation2015; O’Neill et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b). How often this is, or can be, operationalised is a key question and one we return to later.

Personal resilience, self-efficacy and acceptance

The personal resilience of an older person is highlighted as contributing to their ability to come to terms with relocation (Holder & Jolley, Citation2012). Being able to recognise the benefits of living in a care home promotes adjustment, for example, feeling safe and having one’s care needs met (Ellis & Rawson, Citation2015). ‘Reframing’ admission as a positive decision has been specifically identified as helpful (Johnson & Bibbo, Citation2014).

Self-efficacy is also important (Lee, Citation2010). In two USA-based studies, increased self-efficacy (Johnson et al., Citation1998) – alongside appreciating the advantages of living in a care home – was pivotal to residents’ positive adjustment. It also contributes to lower rates of depression (Greene & Dunkle, Citation1992). Talking about losses associated with the transition and seeking ways to manage these – for example continuing engagement with pre-admission hobbies – also supports adjustment (Brandburg et al., Citation2013).

Environmental and organisational conditions

Creating a sense of home after relocation

Creating a ‘sense of home’ post admission has a positive influence on residents’ mental health and quality of life (DeVeer & Kerkstra, Citation2001; Rijnaard et al., Citation2016). There appear to be two routes to facilitating this: reinforcing connectivity with the ‘old life’ and the care home culture. Bringing personal possessions into the home such as furniture, books, photos and pictures is a key dimension of helping to build a bridge between the old and the new (Koppitz et al., Citation2017). Dimensions of the care home culture that promote a sense of home include: the physical layout (e.g. enabling residents to organise their own personal space); mealtimes (e.g. food choices, staff and residents eating together); promotion of resident autonomy; involvement of relatives in care home life; engagement with others; taking part in leisure and social activities; and access to outdoor space.

Feeling welcomed, having confident staff managing the admissions process in a way that prioritises the older person rather than administrative tasks, and being introduced to the care home gradually, have also been identified as important to adjustment (Fitzpatrick & Tzouvara, Citation2019). Establishing connections with other residents promotes a ‘sense of belonging’.

The quality of care is, perhaps obviously, important (Rijnaard et al., Citation2016). Key factors which promote effective adjustment include care which helps residents ‘feel like they still matter’ and which facilitates independence, agency and choice (Wada et al., Citation2020). Axiomatically, higher levels of ‘satisfaction’ with the care received is a key factor (Fitzpatrick & Tzouvara, Citation2019). The cultural sensitivity and competence of care provided i.e. the extent to which care staff recognise and respond to cultural needs, has been specifically associated with more effective adjustment for older people from black and minority ethnic communities. For example, provision of particular diets and/or foods (Amuji, Citation2021).

Healthy transition: process indicators

A healthy transition can be conceptualised, not as a temporal set of stages, but as a process which requires ongoing adjustment. Supporting existing relationships, and the development of new relationships, are important dimensions of a healthy transition (Brownie et al., Citation2014). Retaining a ‘connection to family’ can bolster residents’ ability to cope with relocation; it also promotes a sense of self and identity (Iwasiw et al., Citation2003).

Maintaining links is not straightforward. There is a well known risk of isolation, and depression, post admission which may result in the older person not wishing to see family or friends (Melrose, Citation2004). This can create tensions between the resident, the family and care home staff and may make it more challenging for the older person to develop new relationships; it may also compound existing feelings of isolation (Sun et al., Citation2021). Links can be fostered by family members helping with their relatives’ personal care needs, visiting regularly and including the older person in family outings. Evidence suggests that families derive satisfaction from these roles; their involvement is an important component of the older person’s experience of positive care (Ryan & McKenna, Citation2015).

Admission of a relative to care home is a life transition for family members too. Whilst research exploring the experiences of families is limited, evidence suggests that relatives feel more positive about admission if they consider that effort has been made to involve them in assessment processes and decision making (Afram et al., Citation2015; Moore & Dow, Citation2015; Westacott & Ragdale, Citation2015). This is also the case if they consider that the care home engages well with the older person and that they are receiving good quality care. Carers who have been engaged in providing intensive complex care for some time tend to find the transition more challenging; they struggle to relinquish their caring role and find ways to redefine their ‘carer identity’ post admission (Larkin & Milne, Citation2021).

Healthy transition: outcome indicators

Clear indicators of a healthy transition would include the older person feeling settled and/or recognising the positive aspects of the move (Schumacher et al., Citation2010). Achievement of ‘environmental mastery’ is also important: this is defined as ‘a sense of self efficacy or mastery over environmental demands, which reflect a sense of control’ (Knight et al., Citation2011, p. 871). Unsurprisingly, these features are associated with a lower risk of depression (Greene & Dunkle, Citation1992). A longitudinal study of the first-year post admission, found that encouraging residents to ‘honestly reflect’ on their feelings about their experience of transition helped them to maintain their sense of self, reinforced their individuality, and promoted a sense of ‘still mattering’ (Iwasiw et al., Citation2003).

Outcome indicators also extend to relatives and carers (Afram et al., Citation2015; Cole et al., Citation2018). Enhanced wellbeing of both carers and residents is evidenced in contexts where carers continue to provide (some) care to their relative and advocate for their needs to be met, for example, making sure they have access to their favourite TV programmes (Hainstock et al., Citation2017). Support groups for relatives, which are offered by some care homes, are evidenced as helpful in terms of reducing the stresses associated with the transition for both relatives and the older person themselves (Larkin & Milne, Citation2017).

Promoting healthy transitions into care homes: developing the social work role

As already noted, admission tends to be viewed and treated by the ‘care system’ as a functional process, not as a lived or felt experience; the expedient and cost-efficient management of resources takes precedence. Through this lens, opportunities for an older person to be emotionally, practically and socially supported to manage the transition, are often eclipsed by organisational and/or funding priorities. As employees (usually) of the local state, the role of social workers reflects these priorities. They are often involved in a formal assessment regarding care home admission and in some jurisdictions they have a statutory duty to investigate instances of abuse, including those arising in care homes (Anand et al., Citation2022). They are obliged to balance a duty to promote the rights of an older person to make their own decisions and choices with a duty to ensure that they, nor their family carer, are at risk of harm; they are also obliged to be mindful of the judicious use of limited welfare resources.

It is noteworthy that almost no attention has been paid to exploring how social workers could promote a healthy transition in practice or research. Given the challenges inherent in moving into a care home and the often disempowered status of the older person, this is perhaps surprising. We consider that there are a number of key ways in which social workers could help to facililtate healthy/ier transitions. We acknowledge that whilst there is some variation between the training and roles of social workers in our five countries, they share an engagement with processes of decision making around care home admission and expertise in supporting older people with complex needs and their families.

The social work skills of helping individuals, and families, to make informed, crafted choices and positive decisions is an obvious contribution (Ray et al., Citation2015). We know that older people are often placed in a care home in situations of crisis. Whilst this may challenge opportunities for thoughtful time-rich discussion, engagement can take many forms; there is often a window to share information, build a rapport, and offer advice. Arguably, this is even more important in a context where ‘emptying’ hospital beds and performing a ‘statutory duty’ dominate decision making. These are especially pronounced risks for people with dementia and older people with no family. Recent research examining the role of social work with older people in England highlights the important role they play in advocating for the wishes, agency and autonomy of older people and in protecting their rights to be involved in decisions about their care (Tanner et al., Citation2023). This is a role that needs to be brought to bear on care home transitions.

Melies et al. (Citation2000) identify ‘preparation’ as critical in promoting a (more) positive experience of transition. A key dimension of preparation is supporting the older person to voice their concerns and feelings about the move honestly, particularly their (likely) feelings of loss and fear. Identifying what is most important to them may inform ways to scaffold – at least some sense of – control over the decision and how the transition process will work. Offering tailored information is a key element: about the range of care homes available, costs and sources of financial advice, legal issues, and how the process of moving will be managed. These are all issues that social workers know about and, where offered, relieves older people and their relatives at a time of high stress; we know how challenging families find trying to navigate a complex care system (Ray et al., Citation2020). Engaging with a knowledgeable trusted professional is evidenced as helping to facilitate a more timely co-produced transition (The Parliamentary Ombudsman, Citation2020; Willis et al., Citation2022).

Social workers also have a role to play in challenging the nihilsitic ‘last resort’ and ‘personal failure’ narrative that dominates public discourse, referred to earlier. Admission to a care home may be the only safe choice. It is important to help the older person and their family recognise the benefits of the move, for example having an enhanced sense of security and relief for the, often exhausted, family carer (Larkin & Milne, Citation2021; Şoitu, Citation2021).

Social workers remaining engaged with the older person post admission reflects the fact that the process of assessment, and relationship-focused support, is an ongoing requirement of the whole process of transition. This is the case in Finland where all residents have a ‘named social worker’ – employed by the local state – and also in Romania where all care homes employ a social worker (Şoitu, Citation2021; The Parliamentary Ombudsman, Citation2020). A detailed social work assessment highlighting an older person’s strengths, resources, interests, preferences and biography – as well as their needs – helps to inform the shape and nature of the care home’s care plan and approach to support. Effective adaptation to the new situation is much more likely in contexts where the older person is supported to achieve mastery and exercise agency. A key post-admission role is supporting conversations between the care home staff and the older person, exploring concerns the older person may have about maintaining relationships with family members and friends and/or financial issues, and their feelings about moving to the home (Rossi, Citation2019).

Whilst, in a number of our sample countries (for example, England, Finland and Romania) it is a legal requirement to ‘regularly review’ the care and support of an older resident who is funded by the state, this can be challenging to enforce. Reviews do not always happen and when they do they are not necessarily conducted by a social worker but a less qualified social care worker. Valuable opportunities to (re)engage with the older person’s – and their family’s – concerns, provide proactive advice about legal rights and funding issues, as well as monitor the quality and type of care provided, are lost. This is particularly important in contexts where the older person has no relatives or access to an advocate and/or has dementia where there may be communication issues (Afram et al., Citation2015).

Although it is not common for care homes to employ social workers in Romania – as noted above – this is the case. For a care home to be registered by the Romanian authorities it is mandatory to employ a social worker (Şoitu, Citation2021). The social worker’s responsibilties include contributing to the multidisciplinary pre-admission assessment of potential residents and developing individualised care plans. Post-admission, they adjust the care plan as needed and provide direct support to the older person; they also facilitate engagement between the family and the care home (The Parliamentary Ombudsman, Citation2020). These roles help to achieve a healthy transition.

Conclusion

Moving into a care home represents one of the last transitions an older person will make in their life (Smith et al., Citation2023). Underpinned by an ecological approach, Melies (Citation2010) and Melies et al’s. (Citation2000) theory offers a useful framework for exploring greater social work engagement with care home transitions. Its emphasis on a multi-factorial process challenges the current transactional approach; it also foregrounds the lived experience of the older person and their family and highlights the nature of the transition as a social, emotional and relational journey as well as a physical and practical one. Despite the fact that social work’s skill set is situated squarely on this intersection of issues, no research has been done on exploring its contribution to promoting a healthy transition. Given the growing number of older people with complex needs and their families who come to the attention of social workers across our five countries, and the likelihood that an increasing proportion will need admission to a care home, our paper makes a timely contribution to making the case for a specific focus on this opaque and hidden, yet critical and complex, area of practice. Investment in research to explore the role of social workers in facilitating more positive outcomes for older residents and their families needs to be made beginning with a study in European countries that employ social workers in care homes (Pascoe et al., Citation2023).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alisoun Milne

Alisoun Milne has been an academic for over 25 years in the UK. Before this, she worked as a social worker and social work manager. Her main research interests are mental health in later life, family carers, and social care and social work with older people and their families.

Mo Ray

Mo Ray worked for many years as a social worker with older people in the UK. As an academic, her research interests focus on experiences of care, social care, participatory research methods and community engagement in research and the public understanding of research.

Sarah Donnelly

Sarah Donnelly works at University College Dublin. Her areas of research expertise include ageing, dementia, capacity and decision-making, and adult safeguarding. Sarah is a member of the editorial board for the European Social Work Research Journal and has recently co-edited a book on ‘Critical Gerontology for Social Workers’ (2022, Policy Press).

Sarah P. Lonbay

Dr Sarah Lonbay is an associate professor of social sciences and engagement in the School of Social Sciences at the University of Sunderland. She is also a research fellow in the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) North East and North Cumbria (NENC).

Lorna Montgomery

Dr Lorna Montgomery is a reader in social work, Queen's University, Belfast. Before taking up a post at Queen's, she practised as a social worker within the adult sector for 20 years, primarily within the mental health area. Lorna's teaching and research include work on adult safeguarding, mental health, parenting, and cross-cultural practice.

Francesca Corradini

Francesca Corradini, PhD, worked for many years as a social worker. She is currently a researcher at the Relational Social Work Research Centre in the sociology department of the Catholic University of Milan. Her research interests focus on gerontological social work, social work assessment and social work education.

Daniela Şoitu

Daniela Şoitu is a social sciences specialist and a professor at the department of sociology, Social Work, and Human Resources at the ‘Alexandru Ioan Cuza’ University of Iaşi, Romania. Her main research interests focus on late adulthood, long-term care, and personal and systemic vulnerabilities.

Eeva Rossi

Eeva Rossi (D.Soc.Sc.) works as a university teacher at the University of Lapland. She is a licensed social worker and has worked for more than twenty years with older adults. Her research interests include the ageing and professional practices of gerontological social work.

Sointu Riekkinen-Tuovinen

Sointu Riekkinen-Tuovinen (D.Soc.Sc) is a licensed social worker and researcher. Her interests are in both practice and research particularly, gerontological social work, socio-cultural work and health social work, and more recently effectiveness research in the social and healthcare sector.

Giulia Notari

Giulia Notari, PhD, is a social worker in a third-sector organisation. She is involved in community work, project management and research. She collaborates with the Relational Social Work Research Centre of the Catholic University of Milan

Janet Carter Anand

Janet Carter Anand is a social work academic, educator and practitioner. She has worked in higher education facilities in Australia, the UK, and the Republic of Ireland. Her current research interests include older people's rights, comparative analysis of social work practice and education, and the measurement of outcomes in health social work.

Notes

References

- Aaltonen, M. (2015). Patterns of Care in the Last Two Years of Life Care: transitions and places of death of old people [Academic dissertation]. University of Tampere.

- Afram, B., Verbreek, H., Bleijlevens, M. H., & Hamers, J. P. H. (2015). Needs of informal caregivers during transition from home towards institutional care in dementia: A systematic review of qualitative studies. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(6), 891–903. doi:10.1017/S1041610214002154

- Ambrose, A. (2018). An introduction to transitional thinking. In G. Amado, & A. Ambrose (Eds.), The transitional approach to change. Routledge.

- Amuji, I. (2021). Exploring the cultural sensitivities of UK care home services to the older Nigerian residents. [Doctoral thesis]. Northumbria University.

- Anand, J., Donnelly, S., Milne, A., Nelson-Becker, H., Vingare, E., Deusdad, B., Cellini, G., Kinni, R.-L., & Pregno, C. (2022). The COVID-19 pandemic & care homes for older people in Europe – Deaths, damage & violations of human rights. European Journal of Social Work, 25(5), 804–815. doi:10.1080/13691457.2021.1954886

- Brandburg, G. L., Symes, L., Mastel-Smith, B., Hersch, G., & Walsh, T. (2013). Resident strategies for making a life in a nursing home: A qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(4), 862–874. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06075.x

- Brownie, S., Horstmanshof, L., & Garbutt, R. (2014). Factors that impact residents’ transition and psychological adjustment to long-term aged care: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(12), 1654–1666. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.04.011

- Burton, J. K., Ciminata, G., Lynch, E., Shenkin, S. D., Geue, C., & Quinn, T. J. (2022). Understanding pathways into care homes using data (UnPiCD study): A retrospective cohort study using national linked health and social care data. Age and Ageing, 51(12), afac304. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afac304

- Cole, L., Samsi, K., & Manthorpe, J. (2018). Is there an “optimal time” to move to a care home for a person with dementia? A systematic review of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(11), 1649–1670. doi:10.1017/S1041610218000364

- Covinsky, K. E., Palmer, R. M., Fortinsky, R. H., Counsell, S. R., Stewart, A. L., Kresevic, D., Burant, C. J., & Landefeld, C. S. (2003). Loss of independence in activities of daily living in older adults hospitalized with medical illnesses: Increased vulnerability with age. Journal of American Geriatrics Society, 51(4), 451–458. doi:10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51152.x

- Dening, T., & Milne, A. (2021). Mental health in care homes for older people. In T. Dening, A. Thomas, R. Stewart, & J.-P. Taylor (Eds.), Oxford textbook of old age psychiatry (3rd edition, pp. 343–358). OUP.

- DeVeer, A. J., & Kerkstra, A. (2001). Feeling at home in nursing homes. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 35(3), 427–434. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01858.x

- Donnelly, S., Begley, E., & O’Brien, M. (2018). How are people with dementia involved in care planning and decision-making? An Irish social work perspective. Dementia, 18(7-8), 2985–3003. doi:10.1177/1471301218763180

- Ellis, J. M., & Rawson, H. (2015). Nurses’ and personal care assistants’ role in improving the relocation of older people into nursing homes. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24(13-14), 2005–2013. doi:10.1111/jocn.12798

- Fitzpatrick, J. M., & Tzouvara, V. (2019). Facilitators and inhibitors of transition for older people who have relocated to a long term facility: A systematic review. Health and Social Care in the Community, 27(3), e57–e81. doi:10.1111/hsc.12647

- Forder, J., & Caiels, J. (2011). Measuring the outcomes of long-term care. Social Science and Medicine, 73(12), 1766–1774. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.023

- Gilbert, S., Amella, E., Edlund, B., & Nemeth, L. (2015). Making the move: A mixed research integrative review. Healthcare, 3(3), 757–774. doi:10.3390/healthcare3030757

- Goodman, C, Davies, S. L., Gordon, A. L., Dening, T., Gage, H., Meyer, J., Schneider, J., Bell, B., Jordon, J., Martin, F., Iliffe, S., Bowman, C., Gladman, J. R. F., Victor, C., Mayrhofer, A., Handley, M., & Zubair, M.. (2017). Optimal NHS service delivery to care homes: A realist evaluation of the features and mechanisms that support effective working for the continuing care of older people in residential settings. NIHR Journals Library.

- Greene, R. W., & Dunkle, R. E. (1992). Is the elderly patient’s denial of long term care aversive to later adjustment to placement? Physical and Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 10(4), 59–75. doi:10.1080/J148V10N04_05

- Hainstock, T., Cloutier, D., & Penning, M. (2017). From home to ‘home’: Mapping the caregiver journey in the transition from home care into residential care. Journal of Aging Studies, 43, 32–39. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2017.09.003

- Hanratty, B., Stow, D., Collingridge Moore, D., Valtorta, N. K., & Matthews, F. (2018). Loneliness as a risk factor for care home admission in the English longitudinal study of ageing. Age and Ageing, 47(6), 896–900. doi:10.1093/ageing/afy095

- Harrison, J. K., Walesby, K. E., Hamilton, L., Armstrong, C., Starr, J. M., Reynish, E. L., MacLullich, A. M. J., Quinn, T. J., & Shenkin, S. D. (2017). Predicting discharge to institutional care home following acute hospitalisation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Age and Ageing, 46(1), 547–558. doi:10.1093/ageing/afx047

- Health Service Executive. (2022). Performance Profile July - September 2022, Dublin. https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/publications/performancereports/performance-profile-september-2022-final.pdf.

- Holder, J., & Jolley, D. (2012). Forced relocation between nursing homes: Residents’ health outcomes and potential moderators. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 22(4), 301–319. doi:10.1017/S0959259812000147

- Hoogerduijn, J. G., Buurman, B. M., Korevaar, J. C., Grobbee, D. E., de Rooij, S. E., & Schuurmans, M. J. (2012). The prediction of functional decline in older hospitalised patients. Age and Ageing, 41(3), 381–387. doi:10.1093/ageing/afs015

- Iwasiw, C., Goldenberg, D., Bol, N., & MacMaster, E. (2003). Resident and family perspectives: The first year in a long-term care facility. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 29(1), 45–54. doi:10.3928/0098-9134-20030101-12

- Johnson, B. D., Stone, G. L., Altmaier, E. M., & Berdahl, L. D. (1998). The relationship of demographic factors, locus of control and self-efficacy to successful nursing home adjustment. The Gerontologist, 38(2), 209–216. doi:10.1093/geront/38.2.209

- Johnson, R. A., & Bibbo, J. (2014). Relocation decisions and constructing the meaning of home: A phenomenological study of the transition into a nursing home. Journal of Aging Studies, 30, 56–63. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2014.03.005

- Kable, A., Chenoweth, L., Pond, D., & Hullick, C. (2015). Health professional perspectives on systems failures in transitional care for patients with dementia and their carers: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Health Service Research, 15(1), 567–578. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-1227-z

- Kauppi, M., Raitanen, J., Stenholm, S., Aaltonen, M., Enroth, L., & Jylhä, M. (2018). Predictors of long-term care among nonagenarians: The vitality 90+study with linked data of the care registers. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 30(8), 913–919. doi:10.1007/s40520-017-0869-6

- Knight, T., Davison, T. E., McCabe, M. P., & Mellor, D. (2011). Environmental mastery and depression in older adults in residential care. Ageing and Society, 31(5), 870–884. doi:10.1017/S0144686X1000142X

- Koppitz, A. L., Dreizler, J., Altherr, J., Bosshard, G., Naef, R., & Imhof, L. (2017). Relocation experiences with unplanned admission to a nursing home: A qualitative study. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(3), 517–527. doi:10.1017/S1041610216001964

- Larkin, M., & Milne, A. (2017). What do we know about older former carers? Key issues and themes. Health and Social Care in the Community, 25(4), 1396–1403. doi:10.1111/hsc.12437

- Larkin, M., & Milne, A. (2021). Research on former carers: Reflections on a Way forward, families. Relationships and Society, 10(2), 287–302. doi:10.1332/204674319X15761550214485

- Larsson, A. T., & Österholm, J. H. (2014). How are decisions on care services for people with dementia made and experienced? A systematic review and qualitative synthesis of recent empirical findings. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(11), 1849–1862. doi:10.1017/S104161021400132X

- Lee, G. E. (2010). Predictors of adjustment to nursing home life of elderly residents: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(8), 957–964. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.12.020

- Lee, V., Simpson, J., & Froggatt, K. (2013). A narrative exploration of older people’s transition into residential care. Aging and Mental Health, 17(1), 48–56. doi:10.1080/13607863.2012.715139

- Luker, J. A., Worley, A., Stanley, M., Uy, J., Watt, A. M., & Hillier, S. L. (2019). The evidence for services to avoid or delay residential aged care admission: A systematic review. BMC Geriatriatric, 19(1), 217. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1210-3

- Lundgren, E. (2000). Homelike housing for elderly people: Materialized ideology. Housing, Theory, and Society, 17(3), 109–120. doi:10.1080/14036090051084405

- Meleis, A. (2010). Role insufficiency and role supplementation: A conceptual framework. In A. Melies (Ed.), Transitions theory: Middle range and situation specific theories in nursing research and practice (pp. 13–24.

- Melies, A. I., Sawyer, L. M., Eun-Ok, I., Hilfinger, D. K., & Schumacher, K. (2000). Experiencing transitions: An emerging mid-range theory. ANS Advanced Nursing Science, 23(1), 12–28. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200009000-00006

- Melrose, S. (2004). Reducing relocation stress syndrome inlong-term care facilities. Journal of Practical Nursing, 54(4), 15–17.

- Moore, K. J., & Dow, B. (2015). Carers continuing to care after residential care placement. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(6), 877–880. doi:10.1017/S1041610214002774

- Nihtilä, E., & Martikainen, P. (2008). Institutionalization of older adults after the death of a spouse. American Journal of Public Health, 98(7), 1228–1234. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.119271

- O’May, F. (2007). Transitions into a Care Home, Quality of Life in a care home: a review of the literature. My Home Life, Research Briefing No 1. https://myhomelife.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/MHL-Research-Briefing-1-Managing-Transitions.pdf.

- O’Neill, M., Ryan, A., Tracey, A., & Laird, L. (2020a). “You’re at their mercy”: Older peoples’ experiences of moving from home to a care home: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 15(1), doi.org/10.1111/opn.12305

- O’Neill, M., Ryan, A., Tracey, A., & Laird, L. (2020b). ‘The primacy of ‘Home’: An exploration of how older adults’ transition to life in a care home towards the end of the first year. Health and Social Care in the Community, 30(2), e478–e492. doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13232

- Pascoe, K. M., Waterhouse-Bradley, B., & McGinn, T. (2023). Social workers’ experience of bureaucracy: A systematic synthesis of qualitative studies. British Journal of Social Work, 53(1), 513–533. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcac106

- Ray, M., Milne, A., Beech, C., Phillips, J., Richards, S., Sullivan, M., Tanner, D., & Lloyd, L. (2015). Gerontological social work: Reflections on its role, purpose and value. British Journal of Social Work, 45(4), 1296–1312. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct195

- Ray, M., Tanner, D., & Ward, E. (2020). Minding our business: The significance of self-funderes to social work. University of Brighton. Minding our business: the significance of self-funders to social work – Older People: Care and Self-Funding Experiences (olderpeopleselffundingcare.com).

- Reed, J., & Stanley, D. (2006). Transitions to a care home – The importance of choice and control, quality in ageing: Policy. Practice and Research, 7(4), 12–18.

- Rijnaard, M. D., van Hoof, J., Janssen, B. M., Verbeek, H., Pocornie, W., Eijkelenboom, A., Beerens, H. C., Molony, S. L., & Wouters, E. J. M. (2016). The factors influencing the sense of home in nursing homes: A systematic review from the perspective of residents. Journal of Aging Research, 2016, 1–17. doi:10.1155/2016/6143645

- Rossi, E. (2019). Needs for assistance and support for elderly residents of the housing services centre. Gerontologia, 32(4), 235–250. doi:10.23989/gerontologia.75745

- Ryan, A., & McKenna, H. (2015). “It’s the little things that count”. Families experience of roles, relationships and quality of care in nursing homes. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 10(1), 38–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12052

- Scheibl, F., Farquhar, M., Buck, J., Barclay, S., Brayne, C., & Fleming, J. (2019). When frail older people relocate in very old age, who makes the decision? Innovation in Aging, 3(4), 1–9. doi:10.1093/geroni/igz030

- Schumacher, K. L., Jones, P. S., & Melies, A. F. (2010). Helping elderly persons in transition: A framework for research and practice. In A. F. Melies (Ed.), Transition theory: Middle-range and situation-specific theories in nursing research and practice (pp. 129–144). Springer.

- Schumacher, K. L., & Meleis, A. I. (1994). Transitions: A central concept in nursing. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 26(2), 119–127. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1994.tb00929.x

- Smith, L., Phillipson, L., & Knight, P. (2023). Re-imagining care transitions for people with dementia and complex support needs in residential aged care: Using co-designed sensory objects and a focused ethnography to recognise micro transitions. Ageing and Society, 43(1), 1–23. doi:10.1017/S0144686X2100043X

- Şoitu, D. (2021). Long-term healthcare system. Development and future policies for Romania. In D. Şoitu, Š Hošková-Mayerová, & F. Maturo (Eds.), Decisions and trends in social systems. Innovative and integrated approaches of care services. Springer International Publishing.

- Sullivan, G. J., & Williams, C. (2017). Older adult transitions into long-term care: A meta-synthesis. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 43(3), 41–49. doi:10.3928/00989134-20161109-07

- Sun, C., Ding, Y., Cui, Y., Zhu, S., Li, X., Chen, S., Zhou, R., & Yu, Y. (2021). The adaptation of older adults’ transition to residential care facilities and cultural factors: A meta-synthesis. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 1–14. doi:10.1186/s12877-020-01943-8

- Sury, L., Burns, K., & Brodaty, H. (2013). Moving in: Adjustment of people living with dementia going into a nursing home and their families. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(6), 867–876. doi: 10.1017/S1041610213000057

- Tanner, D., Glasby, J., & McIver, S. (2015). Understanding and improving older people’s experiences of service transitions: Implications for social work. British Journal of Social Work, 45(7), 2056–2017. doi:10.1093/bjsw/bcu095

- Tanner, D., Willis, P., Beedell, P., & Nosowska, G. (2023). Social Work with Older People: The SWOP project https://swopresearch.wordpress.com/research-findings/.

- The Parliamentary Ombudsman. (2020). Ensuring the quality of services for older adults with mermory disorder, EOAK/6642/2019.

- Thetford, C., & Robinson, J. (2006). Older People's Long-Term Care Decision-Making in Flintshire. Research Report 105/06. Health and Community Care Research Unit, The University of Liverpool, UK. www.liv.ac.uk/haccru/html/reports.html.

- Toot, S., Swinson, T., Devine, M., Challis, D., & Orrell, M. (2017). Causes of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(2), 195–208. doi:10.1017/S1041610216001654

- Verbeek, H., Meyer, G., Leino-Kilpi, H., Zabalegui, A., Hallberg, I. R., Saks, K., Soto, M. E., Challis, D., Sauerland, D., Hamers, J. P., & RightTimePlaceCare Consortium (2012). A European study investigating patterns of transition from home care towards institutional dementia care: The protocol of a RightTimePlaceCare study. BMC Public Health, 23(12), 68. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-68

- Wada, M., Canham, S. L., Battersby, L., Sixsmith, J., Woolrych, R., Fang, M. L., & Sixsmith, A. (2020). Perceptions of home in long-term care settings: Before and after institutional relocation. Ageing and Society, 40(6), 1267–1290. doi:10.1017/S0144686X18001721

- Westacott, D., & Ragdale, S. (2015). Transition into permanent care: The effect on the family. Nursing in Residential Care, 17(9), 515–518. doi:10.12968/nrec.2015.17.9.515

- Willis, P., Lloyd, L., Hammond, J., Milne, A., Nelson-Becker, H., Perry, E., Ray, M., Richards, S., & Tanner, D. (2022). Casting light on the distinctive contribution of social work in multidisciplinary teams for older people. British Journal of Social Work, 52(1), 480–497. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab004