ABSTRACT

There is a reciprocal relationship between social work and (social) policy: (i) social workers act on the basis of social policy guidelines, and (ii) they should contribute to changing these frameworks in the interest of their profession and of service users. Previous studies have outlined different routes for social workers to influence policy: One of these is referred to as ‘holding elected office’. This paper provides a descriptive analysis of social workers with political mandates in Germany. My first step is to compile a comprehensive dataset of current members of parliament to identify social workers. I then conduct an online survey among this group to learn more about their political socialisation processes, their political career paths, and their current political work. My results show that social workers accept mandates at all political levels, with their share being lowest at the national level. The decision of social workers to become directly involved in politics is closely linked to the experiences that they have gained in their professional practice. The process of politicisation tends to run parallel to their professional careers.

ZUSAMMENFASSUNG

Zwischen Sozialer Arbeit und (Sozial-)Politik besteht ein wechselseitiges Verhältnis: (i) Sozialarbeiter:innen handeln auf der Grundlage sozialpolitischer Grundlagen und (ii) sollen Sozialarbeiter:innen dazu beitragen, diese Rahmenbedingungen im Interesse ihrer Profession und der Adressat:innen zu verändern. Bisherige Studien haben verschiedene Möglichkeiten für Sozialarbeiter:innen aufgezeigt, Einfluss auf die Politik zu nehmen: Eine davon wird als „Holding elected office“ bezeichnet. Dieser Beitrag liefert eine deskriptive Analyse zu Sozialarbeiter:innen mit gewählten Mandaten in Deutschland. In einem ersten Schritt wurde ein umfassenden Datensatz aktueller Parlamentsmitglieder zusammengestellt, um Sozialarbeiter:innen unter ihnen zu identifizieren. Anschließend wurde eine Online-Umfrage durchgeführt, um mehr über ihre politischen Sozialisationsprozesse, ihre politischen Karrierewege und ihre aktuelle politische Arbeit zu erfahren. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass Sozialarbeiter:innen Mandate auf allen politischen Ebenen annehmen, wobei ihr Anteil auf nationaler Ebene am niedrigsten ist. Die Entscheidung von Sozialarbeiter:innen, sich direkt in der Politik zu engagieren, ist eng mit den Erfahrungen verbunden, die sie in ihrer beruflichen Praxis gesammelt haben. Der Prozess der Politisierung verläuft tendenziell parallel zu ihrer beruflichen Laufbahn.

Introduction

(Social) policy and social work in Germany are in a reciprocal relationship that is not without tension. On the one hand, social policy defines the basis for social work. On the other hand, social work can shape the legal framework in the interests of the profession and of the service users. The latter activities are aimed at influencing and changing (social) policies and are referred to as policy practice of social workers (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2013, p. 6; see Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b, for an overview of the state of research). The object of their actions is primarily the representation of ‘weak interests’ (Leitner & Schäfer, Citation2022, p. 20). The term ‘weak’ refers to the interests of people with limited resources in political interest mediation processes (Clement et al., Citation2010, p. 7), such as the homeless, drug users, refugees, or the long-term unemployed, who are also among the classic addressees of social work (Leitner & Stolz, Citation2022, p. 20). Through their work with various groups of service users, social workers are particularly familiar with the interests and the problems that arise when implementing the legal framework of social policy in practice. With this in mind, it seems to make little sense to assign social workers the task of dealing with or even solving social problems, which are always (also) structurally conditioned, but not to allow them to influence the structural framework (Schneider, Citation2001, p. 28). Their knowledge enables social workers to develop specific ideas about which political measures need to be changed and how to adjust them (Lane & Pritzker, Citation2018, p. 469). According to Sorg (Citation2001), social workers even have a responsibility to bring their expertise into political decision-making processes and to intervene in design processes – that is, to engage in policy practice. Of social workers policy practice, the most direct form is accepting an elected office.

Policy practice by social workers

When analysing the policy practice of social workers, several questions arise: Why do they engage in policy practice? What factors determine social workers’ political behaviour? How do they become involved? What are the routes they use for their political engagement?

One model that attempts to systematically integrate these questions – and that is grounded in social work – is Gal and Weiss-Gal’s (Citation2015, Citation2023b) conceptual framework of ‘policy practice engagement’ (PPE). The authors used findings from a cross-national study of social workers’ policy practice engagement to develop their conceptual framework (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b, pp. 10–12). Their framework offers ‘a way of thinking more systematically about the various factors that determine how social workers seek to influence policies in very diverse arenas and forms’ (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b, p. 11). According to this model, the determining factors are environment, opportunity, facilitation, and motivation. Opportunity, facilitation, and motivational factors impact each other and ‘are directly influenced by the environments’ (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b, p. 11). The model helps to explain how these factors affect ‘the engagement of social workers in the policy process through diverse policy routes’ (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b, p. 11).

The international discussion identifies six routes through which social workers ‘seek to impact policies at the local, regional, national or federal levels, whether through the formulation of new policies, by defending existing policies and suggesting changes in them, or by resisting policy proposals detrimental to service users’ (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023a, p. 49).

Weiss-Gal (Citation2017) differentiates between professional and civic routes (also Gerster, Citation2018, p. 11; Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b, pp. 29–39):

Professional routes: ,Policy practice as social worker’, ,Macro or Micro policy practice’, ,Policy involvement by professional organizations’, ,Academic policy practice’ and ,Street-level policy involvement’.

Civic routes: ,Voluntary political participation’ and ,Holding elected office’

These explanations provide the framework for the author's research project, which analyses the route ‘holding elected office’ in more detail for Germany (Löffler, Citation2023, Citation2024). The focus is thus on social workers who can directly influence policies and represent weak interests in political decision-making processes. The route ‘holding elected office’

is rooted in the notion of democratic citizenship, which encourages members of society to play an active political role. The policy involvement may, but not necessarily, entail remuneration and tends to be more intensive than in the case of voluntary political participation. (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b, pp. 31–32)

Instead, as shows the route ‘holding elected office’ entails different activities at the local, state, and federal level in Germany:

At the local level, ‘holding elected office’ can take three forms: (i) a voluntary activity, (ii) a professional part-time activity, or (iii) a professional full-time work. These alternatives can be distinguished by the amount of time involved in the political mandate and/or the monetary remuneration for the mandate (Reiser, Citation2006). There are only a few larger cities, mainly in the south of Germany, where members of parliaments (MPs)Footnote1 at the local level are paid for their political work and live from their political mandate (see Leitner & Stolz, Citation2022, Citation2023). In most municipalities, social workers and other professionals work one to 40 h per week in their profession in addition to their political mandate (Leitner & Löffler, Citation2024).

At the state and federal level ‘holding elected office’ is a ‘professional activity’, i.e. largely a full-time work. The main difference to the ‘civic routes’ of ‘private citizens’ is that the politicians receive a full salary for their work (Gerster, Citation2018; Weber, Citation1926). In these cases, social workers change their occupation by accepting elected office and start to live not only ‘for’ but also ‘from’ their political work (Weber, Citation1926).

Literature review and research gap

As politicians in elected office, social workers have the opportunity of a ‘real’ political mandate (Leitner & Stolz, Citation2023), which increases their scope of action in political decision-making processes at the local, state, or federal level. This is necessary to challenge the existing power structure and to advance public policy (Binder & Weiss-Gal, Citation2021, p. 1). Although it is assumed that elected representatives have greater opportunities to use their knowledge to influence policy decisions and ‘influence the policy formulation process from within’ (Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b, p. 31; also Amann & Kindler, Citation2022, p. 4; Binder & Weiss-Gal, Citation2021; Lane & Pritzker, Citation2018, p. 468), this specific group of actors has long been ignored in the academic discussion of social worker’s engagement in making policies (Kindler & Amann, Citation2022; see Amann & Kindler, Citation2022 and Gal & Weiss-Gal, Citation2023b for an overview of the international state of research).

At the international level, empirical research on this specific group is now available for Canada (Greco, Citation2020; McLaughlin et al., Citation2019), Israel (Binder & Weiss-Gal, Citation2021), Switzerland (Amann & Kindler, Citation2021a, Citation2021b, Citation2022; Kindler & Amann, Citation2022), the United Kingdom (Scourfield & Warner, Citation2022; Gwilym, Citation2017), and the United States (Lane, Citation2008, Citation2011; Lane & Humphreys, Citation2011, Citation2015; Meehan, Citation2018, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Citation2021; Miller et al., Citation2021; Pence & Kaiser, Citation2022). Almost all studies analyse the motivation of social workers to run for and hold political office. They confirm that ‘holding elected office’ is a promising career path for social workers. The studies point out that their motivation is strongly influenced by social work studies and social work practice (Binder & Weiss-Gal, Citation2021; Greco, Citation2020; Gwilym, Citation2017). The existing studies also focus on the influence of gender (Lane & Humphreys, Citation2015; Meehan, Citation2018) and age (Meehan, Citation2018) on their motivation. Previous research focusses on socialisation theory issues such as family background and biographical experiences (Gwilym, Citation2017; McLaughlin et al., Citation2019), social networks, and membership in professional associations (Amann & Kindler, Citation2022; Binder & Weiss-Gal, Citation2021; Lane, Citation2011). In addition, there is one study that examines strategies of policy engagement used by social workers holding elected office (Kindler & Amann, Citation2022).

For Germany, there is only the exploratory investigation by Leitner and Stolz (Citation2022; Leitner & Stolz, Citation2023) who studied the 19th election period of the German Bundestag (2017–2021), the Bavarian State Legislature (2018–2023), and the 2020–2026 period of the Munich City Council exemplary to gain initial insights on social workers with political mandates in German parliaments. Their sample contained ‘parliamentarians and councillors who have either completed a degree in social pedagogy or social work [but also] […] child-care workers and nursery teachers, remedial teachers, or special needs teachers with experience in the field of social work’ (Leitner & Stolz, Citation2022, p. 3). Focussing on the political career and career paths of these selected professionals, their study shows that by holding elected office, social workers exercise a ‘real’ political mandate (Leitner & Stolz, Citation2023). Additionally, they increase their scope of action in political decision-making processes at the local, regional or federal level.

So, it is not yet known to what extent social workers are represented in German parliaments. There is a lack of data on this group of persons, their biographies, and their paths from social work into politics.

Research aim and method

This paper aims to show whether and to what extent social workers are represented in German parliaments.Footnote2 It also provides a detailed overview of the sociodemographic composition of this group of politicians and their motivations and paths into politics.

Sampling

The target group of this research project consists of elected representatives in political parliaments at national, state, and local level who have completed a degree in social work/social pedagogy and can thus be categorised as belonging to the profession of social work.

Field access

I employed two methods to identify social workers in German parliaments. First, I scraped the websites of the German Bundestag as well as all German state parliaments, the websites of individual members of parliament, and the websites of the respective political parties. I identified 2,621 members of parliament at the federal and state level (June 2022), whose data records were fully included in the scraping. 736 members of parliament hold a mandate in the German Bundestag (20th legislative period), 1,521 persons hold an office in the state parliament and 361 politicians are part of the citizens’ assemblies (Bremen, Hamburg) or the House of Representatives (Berlin) in the city-states. Based on this dataset, I searched for the keywords ‘social worker’, ‘social pedagogue’, ‘social work’, and ‘social pedagogy’ to identify (former) social workers. This procedure identified members of parliament who (i) identified themselves as belonging to the social work profession and have indicated ‘social worker’ or ‘social pedagogue’ as their profession (variable ‘job’), and/or (ii) had a degree in social work or social pedagogy (regardless of which profession was identified in the dataset).

Secondly, I contacted the county and/or district associations (Kreis – und/oder Bezirksverbände) of the seven parties represented in the German Bundestag by email and requested information on politically engaged social workers in the municipalities.

Once social workers in the parliaments had been identified, two online surveys (one for professional politicians at the national and state level and one for social workers in local politics) were developed to learn more about their motivations and paths into politics.

The identified social workers at the national and state level were personally informed about the research project by e-mail in September 2022 and asked to participate in an online survey (Welker & Wünsch, Citation2010). In order to reach the social workers at the local level, the local and/or district associations (Kreis- und/oder Bezirksverbände) were chosen as field access. They were asked to inform the social workers in their parties about the online survey and to share the link to the survey. The surveys were open for six weeks and a reminder was sent every two weeks. Both questionnaires were constructed based on the international state of research and included eight sections: Educational background, Professional career, Social work and politics, Politicisation, Political activity, Political career, Participation resources, and Professional knowledge. The questionnaire contained mostly closed questions (scaled questions, single and multiple-choice questions, and rank order questions). For some topics, open-ended questions were also included. These responses were categorised and some were included as quotations in the analysis and presentation of findings.

In line with the aim of the study, which was to describe this specific group of politicians and their paths into politics, a descriptive analysis of the data was conducted. This was carried out using SPSS.

Limitations

The population of MPs at state and national level is known and each of them could be contacted and thus enabled to participate. Discrepancies between the number of population and the number of participants in the study result from self-selection strategies; some MPs decided not to participate. In contrast, there is no information on the population of MPs at the local level. It is not fully known to what extent the inquiry was forwarded to the relevant people in the municipalities. In addition, all social workers were of course free to decide whether they wanted to participate in the study, depending on their resources and interests. As for the participants, it can be assumed that they are people who were particularly interested in the topic and who took the opportunity to bring their interests into the study and to have their concerns heard.

Findings

The findings of the database analysis and the two surveys are summarised below.

Data on social workers in state and national parliaments

The analysis of 2,621 datasets of MPs at the state and national level showed that 64 MPs are social workers. 17% of them have a mandate in the federal parliament and 83% have a mandate at the state level (including MPs who have a mandate in the parliaments of the three city states). The highest percentage of 3.6% is held by professional politicians in the city states. In the state parliaments, 2.6% are social workers, and in the Bundestag, 1.5%. The proportion of social workers in parliaments seems to increase the lower the political level of the parliament. In total 2.4% of all politicians at the state and national level are (former) social workers. The example of the Bundestag shows that their share (1.5% of all members of parliament) is rather low compared to other professional groups (e.g. 20% law graduates, 14% economists).Footnote3 At 59%, the majority of social workers at the state and national level are female, whereas only 34% of all members of parliament at national and state level are. In the national parliament (German Bundestag), the percentage of female social workers is even higher at 82%. The average age of the social workers is 50 years. Three-quarters of the representatives belong to left-wing parties.

Findings of the online surveys

A total of 69 social workers and 3 social work students participated in the (two) surveys.Footnote4 They have mandates in national (2), state (17), and local (49) councils. 4 people did not indicate in which parliament they were elected. The response rate for MPs at the national and state level was therefore 36%. In total, 71% of all participants stated they belong to a party on the left of the political spectrum: With 35%, the largest group belongs to the Green Party.

Socio-demographic data

42% of the participants in the online surveys are female, 32% report being male and 26% didn’t answer this question. The average age of the respondents is 47 years. Regarding their current civil status, 10 respondents stated that they were single, and 33 that they were married or living in a stable partnership. 7 are separated or divorced. 41% of the MPs state that they have children.

Educational path

Prior to their studies, 29 persons had completed vocational training, 15 of them in the social and health care sector. 64 social workers studied at a college or university in Germany and two abroad. Slightly more than half of the politicians fully or rather agreed that they had studied social work to change social ills. Nearly 70% of the MPs had chosen to study social work in order to engage for more social justice in society.

Professional career

42 MPs were already working in different areas of social work practice (including child and youth welfare, outpatient assistance for people with disabilities, and assistance for the homeless) before graduating. After graduation, 62 politicians worked in various fields of social work. 27 of the politicians currently work on a voluntary basis in addition to their mandate. A total of 32 MPs (mainly from the local level) have paid jobs in social work practice. While the social workers in the national and state parliaments work full-time as politicians, the social workers in the municipalities work between one and 40 h per week in social work practice in addition to their engagement in politics. Three-quarters of them work more than 20 h a week in professional practice and in very different fields of social work. Besides their own professional experience and social work activities, about 50% of the politicians have contacts in social work practice through constituency work, social engagement, or support of local social projects. It can be assumed that they have professional social work knowledge, are familiar with the problems of the service users and could bring their interests into the political decision-making process.

Process of politicisation

The interest of social workers in politics mostly comes from their parents and other family members. It results mainly from the fact that the parents were or are political and that politics was discussed in the family. Another strong influencing factor is the study: Almost 60% of the survey participants state that they joined the party during or after their studies. While studying social work they understood that political engagement is part of social work. Two thirds of the social workers state that their professional activities include(d) forms of policy practice. But from their point of view, the possibilities of social work are not enough to change the reality of people's lives; real changes can ‘only be achieved at the political level’. So there remains a desire to be able to make a real difference through involvement in a party. The social workers joined primarily parties of the left spectrum in order to ‘contribute to democracy’ and ‘change something’. The individual reasons for joining a party can be summarised as ‘to initiate change’, ‘to achieve improvements’ and ‘to be able to help shape things’. The social workers want to ‘be heard’ and not just complain, they are willing to exert influence and fight for better living conditions and social justice themselves. The high approval rates for the political nature of social work also fit in with this. The group of social workers in politics seems to attach particular importance to the political side of social work.

Political career

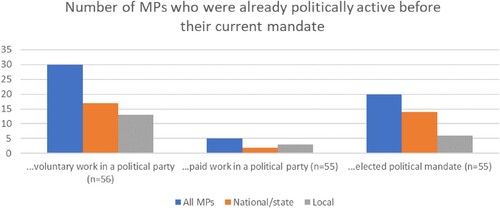

In most cases, the political career ran parallel to the professional career in social work. shows that before being elected to parliament, 30 of the social workers stated that they had held volunteer positions in a political party before their current mandate. For example, they were members of the party board at the local, district, or state level. They were also members of the youth welfare committee, spokespersons for the youth organisation, or involved in party working groups. One MP reported that they had done an internship in the office of an MP in the national parliament. Volunteering takes place at all levels of the party (local, district, county, state, and national) and lasts between two and up to 38 years: MPs have been involved most often and also for the longest time at the local and district levels of the party. Five politicians had also previously held paid positions at the district and the state level in the party or its youth organisation. 20 MPs stated that they already had held a mandate at the local, state, or national level before their current mandate. In some cases, they have even had several elected mandates before being elected as MPs, most often in the municipalities. The duration of these previous mandates ranged from one to 18 years.

Current political work

Another question in the survey was how long MPs had their current mandate. The duration varied between one and 36 years. 6 social workers received their mandate in the year of the survey (2022). Social workers with a mandate at the municipal level have the longest term of office (up to 36 years). At the federal and state level, the longest term of office is 16 years. Overall, about half of the MPs state that their mandate lasted between one and eight years, which corresponds to one or two election periods.

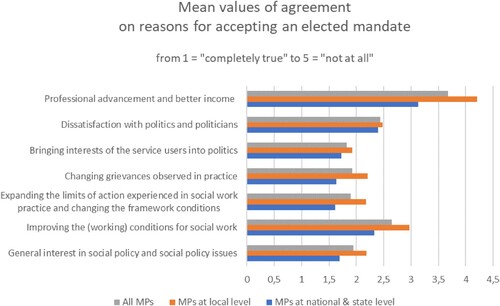

shows the repondents’ agreement with different reasons for accepting an elected mandate. Overall, ‘Bringing interests of the service users into politics’ has the highest level of agreement. A more differentiated view shows that among the MPs at the national and state level the agreement is sill somewhat higher for ‘Expand the limits of action experienced in social work practice and changing the framework conditions’ as well as ‘Changing grievances observed in practice’ than at the local level.

This was followed by two questions asking the MPs to rate the extent to which they had succeeded in incorporating knowledge from practice and the interests of service users into policy. They could choose between 1 = ‘to a very high degree’ and 5 = ‘not at all’. These questions have been answered by 48 MPs. 65% of them say that they have succeeded to a high or very high degree in bringing the knowledge from their (former) professional activities into the political committees. At the same time, MPs at the national and state level agreed to a much greater extent (88%) than politicians at the municipal level (52%). Around 45% of the MPs felt that they were able to bring the interests of the service users into the political decision-making processes to a high or very high degree. This question also showed a strong discrepancy concerning the political level: while only 32% of the social workers with a mandate at the local level stated that they can bring the interests of the service users into the political decision-making processes to a high or very high degree, two thirds of the national and state politicians agreed.

In this context, it was also interesting to analyze which committees the MPs sit on. They could contribute their knowledge to the discussions in the committees and act as advocates. At the municipal level, most MPs sit on the social committee and/or the youth welfare committee. Only a few are members of committees that at first sight seem to have less to do with social work. At the national and state level, it is more common for MPs to sit on committees that have nothing to do with their original profession. At the same time, 47 out of 52 MPs stated that they have the opportunity to work on other policy areas in addition to committee work.

Discussion

Gender effects

The explorative study by Leitner and Stolz (Citation2022) shows that the majority of ‘social professionals’ in politics are female, which is confirmed in this analysis of all elected representatives from social work at the federal and state level. This is striking because, independent of occupational groups, two-thirds of federal and state MPs are male. It can be assumed that this discrepancy results from the female connotation of the social professions: At the end of 2019, the share of female employees in health and social services was 77% (Destatis, Citation2022). This means that in social work, men are proportionally more likely than women to choose a path from social work into politics. Similar effects are evident in the career advancement of women into management positions in social work (Sachße, Citation2020). These gender effects are also indicated in international studies (Meehan, Citation2018; Lane & Humphreys, Citation2015) and could be the subject of further research.

Party affiliation and politicization

In Germany, the path into politics usually begins with joining one of the political parties (Gerster, Citation2018, p. 18). As shown, this is also true for the majority of politicians in social work. Hoffmann (Citation2011, p. 80) explains party membership in general with a basic attitude that she calls ‘political efficacy’. She argues that this attitude is characterised by a sense of efficacy in political action and consists of a combination of interest in politics and a belief in political self-competence and the external efficacy of political work. Like the survey of all members of the German Bundestag by Laux (Citation2011), this study of federal, state, and local parliamentarians shows that the most important reason for joining a party is the idea of achieving political goals. Social workers want to help shape and change society according to their ideas. As in other studies (Leitner & Stolz, Citation2022; Kindler & Amann, Citation2021), the results of my own study also show that social workers - predominantly, but not exclusively – choose to join a left-wing party.

International studies on social workers with a political mandate show that interest in politics and the desire to bring about social change result from early political socialisation. Four socialisation instances are distinguished (McLaughlin et al., Citation2019): the family of origin, values, and knowledge from social work studies, professional experiences with proximity to politics, and influences from social and professional networks. The high importance of family socialisation (e.g. Lane & Humphreys, Citation2011; Lane & Pritzker, Citation2018, p. 468) is also confirmed for the social workers in this study. Around one third of the respondents also cited their studies and contact with fellow students as an additional influence on their political interest (on the importance of social work studies as a socialisation instance see also Binder & Weiss-Gal, Citation2021, p. 12). Internships during studies represent a ‘politicisation thrust’ (Kulke, Citation2021, p. 156). For the confrontation with real cases (ibid., p. 156 f.) highlights the discrepancies between the demands made on one’s own actions and the given possibilities for action.

Like initial international studies (Gwilym, Citation2017; McLaughlin et al., Citation2019), the presented results show that students and social workers recognise through professional practice experiences (even after graduation) that social work practice activities are not sufficient to promote more just and equitable policies. This realisation leads to policy engagement among the study group. Due to the chosen sample, the present study cannot answer why other social workers are less politically engaged despite the same conditions.

Political career

According to Reiser (Citation2006, p. 62), the path into politics is characterised by a specific combination of push and pull factors. This is also evident for the social workers: Dissatisfaction with the opportunities for action in professional practice could be identified as a push factor, and at the same time the prospect of more opportunities for participation and shaping policy as a politician could be identified as a pull factor. The results of my study thus confirm international findings (Binder & Weiss-Gal, Citation2021; Gwilym, Citation2017) for social workers holding elected office in Germany.

As in the exemplary study by Leitner and Stolz (Citation2022), the present study shows that the political path of social workers begins with a mandate at the local, district, or county level - and thus at the lowest political levels. These first offices are therefore the ‘stepping stone’ to mandates at the state or national level and give politicians ‘the opportunity […] to gain experience, develop leadership skills and familiarise themselves with the democratic “rules of the game”’ (Püttner, Citation2007, p. 390). Through their many years of participation and the experience they have gained at these lower levels, they prove ‘their suitability (political skills, loyalty, etc.)’ (Leitner & Stolz, Citation2023, p. 6) for a paid mandate at the state or federal level.

Concluding thoughts

This paper first showed the reciprocal relationship between social work and social policy. It outlined the possibilities for social workers to become politically active. The route ‘holding elected office’ discussed at the international level was analyzed in more detail for Germany. Holding elected office could be identified as a particular way of bringing the interests of service users into political decision-making processes through advocacy. As professional politicians from social work in Germany have so far been largely ignored in the academic debate, many open questions remain, which are to be investigated in a further study. This paper provides an insight into the initial findings of a study on social workers in national, state, and local politics. It has been shown that there are social workers in the parliaments at all political levels. For the participants of the quantitative survey, it was possible to trace the path from social work into politics and to identify first regularities in this regard.

A differentiated knowledge of (political) socialisation processes and the importance of academic education as an instance of socialisation, among other things, must be the subject of further research. Another research deficit, which takes a look at the micro level of politics (Schöne, Citation2020, p. 194), is formed by the actions and related possibilities for action that professional politicians have and use to influence sociopolitical processes in the interest of their (former) service users. It became clear that the MPs see opportunities to bring their knowledge into the political processes, but it remains open, among other things, to how exactly they manage to do this. In Germany, political decisions are prepared, among other ways, in the different committees. The exemplary analysis of the representation of social workers in two committees of the German Bundestag relevant to social work is rather sobering in this respect: Of the 49 members of the ‘Committee for Labor and Social Affairs’ only three are professional politicians from social work. In the ‘Committee for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women, and Youth’ there is only one social worker. Another instrument that can be used to bring ‘weak’ interests into the decision-making process is the speaking time allocated to the parliamentary groups in plenary sessions. In their speeches, politicians can comment on motions. One social worker uses this instrument to demand that, with all measures, consideration must always be given to ‘how they will be received by the poorer, by those receiving social benefits or lower incomes’ (BR220623, BT05). A differentiated analysis of speeches in the German Bundestag as an instrument of advocacy is still lacking.

It remains to be investigated whether, how, and in which phases of political processes (political cycle model according to Lasswell, Citation1956) social workers succeed in introducing ‘weak’ interests and to what extent political decisions are influenced by the knowledge introduced by social workers. It can also be asked what conflicts arise from competing interests for their professional action. In the course of the author's research project, these questions will be pursued in a more differentiated manner and thus an understanding of the observations made so far will be sought through qualitative data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eva Maria Löffler

Dr. Eva Maria Löffler is a social worker (MA) and currently working as a postdoc at the University of Applied Sciences Cologne where she is researching social workers in politics. She has already published a paper on this topic in the journal of Social Work in Germany. Her further research interests are professional action in social work, theories of social work and poverty. She has a thematic focus on social work with the elderly. She examines how the welfare state framework enables professional action. But also, how social workers can influence these frameworks

Notes

1 In this paper the term 'Member of Parliament' (MP) is used for all three levels (local, state, federal/national). Even though at the local level they are not necessarily full-time politicians and paid for their political work as shown.

2 This paper is part of a bigger research project on social workers as members of parliament in Germany. The project uses a multi-method approach that includes the analysis of existing databases, a quantitative survey, a panel discussion, and qualitative interviews with members of parliament. This paper is based on the first two steps of data collection: the analysis of data sets and two quantitative surveys. The next step will be the combination of the quantitative data with qualitative data obtained through the category-based analysis of a panel discussion and qualitative interview data. In this sense, life course data of social workers holding elected office will be analyzed and then combined with biographical. The profession-theoretical study is thus located at the intersection of quantitative life course and qualitative biographical research (Sackmann, Citation2013).

3 The analysis of these three groups of employees with an academic degree in Germany shows that 4% have a law degree and 21% have a degree in economics. Around 4% of the employed persons with an academic degree have studied social work/social pedagogy (own calculations according to BA 2022). In this sense, the ratio of occupational groups among members of the Bundestag does not reflect the distribution in the working population in Germany. Law graduates in particular are significantly overrepresented in the Bundestag.

4 Not all participants answered all questions. This may result in discrepancies.

References

- Amann, K., & Kindler, T. (2021a). Einleitende Gedanken zum parteipolitischen Engagement von Fachpersonen der Sozialen Arbeit in der Schweiz. In K. Amann, & T. Kindler (Eds.), Sozialarbeitende in der Politik: Biografien, Projekte und Strategien parteipolitisch engagierter Fachpersonen der Sozialen Arbeit (pp. 15–19). Frank & Timme GmbH.

- Amann, K., & Kindler, T. (2021b). Sozialarbeitende in der Politik: Biografien, Projekte und Strate-gien parteipolitisch engagierter Fachpersonen der Sozialen Arbeit. Frank & Timme GmbH.

- Amann, K., & Kindler, T. (2022). Social workers in politics–a qualitative analysis of factors influencing social workers’ decision to run for political office. European Journal of Social Work, 25(4), 655–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2021.1977254

- Binder, N., & Weiss-Gal, I. (2021). Social workers as local politicians in Israel. British Journal of Social Work, Article bcab219, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcab219

- Clement, U., Nowak, J., Ruß, S., & Scherrer, C. (2010). Einleitung: Public Governance und schwache Interessen. In J. Nowak, S. Ruß-Sattar, & C. Scherrer (Eds.), Springerlink Bücher. Public Governance und schwache Interessen: Partizipation unterpriviligierter Akteure? (pp. 4–23). VS Verlag für Sozialwis-senschaften.

- Destatis. Statistisches Bundesamt. (2022). Erwerbstätige: Deutschland, Jahre (bis 2019), Wirtschaftszweige (WZ2008), Geschlecht. Online verfügbar unter https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis/online?sequenz=tabelleErgebnis&selectionname=12211-9008#abreadcrumb, zuletzt geprüft am 10.03.2023.

- Dischler, A., & Kulke, D. (2021). Zum Verhältnis von Sozialer Arbeit und politischer Praxis - Theorie, Empirie und Praxis politischer Sozialer Arbeit. In A. Dischler, & D. Kulke (Eds.), Theorie, Forschung und Praxis der sozialen Arbeit: Band 22. Politische Praxis und Soziale Arbeit: Theorie, Empirie und Praxis politischer Sozialer Arbeit (pp. 9–22). Verlag Barbara Budrich.

- Gal, J., & Weiss-Gal, I. (2013). Policy practice in social work: An introduction. In J. Gal, & I. Weiss-Gal (Eds.), Social workers affecting social policy: An international perspective on policy practice (pp. 1–16). Policy Press.

- Gal, J., & Weiss-Gal, I. (2015). The 'Why' and the 'How' of policy practice: An eight-country comparison. British Journal of Social Work, 45(4), 1083–1101. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bct179

- Gal, J., & Weiss-Gal, I. (2023a). The policy engagement of social workers: A research overview. European Social Work Research, 1(1), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1332/SGNP8071

- Gal, J., & Weiss-Gal, I. (2023b). When social workers impact policy and don’t just implement It: A framework for understanding policy engagement. Bristol University press.

- Gerster, F. (2018). Politik als Beruf: Eine motivationspsychologische Analyse (1. Auflage). Nomos.

- Greco, C. E. (2020). “I’ve Got to Run Again”: Experiences of Social Workers Seeking Municipal Office in Ontario [Thesis (Master of Social Work)]. Wilfrid Laurier University. https://scholars.wlu.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3439&context=etd.

- Gwilym, H. (2017). The political identity of social workers in neoliberal times. Critical and Radical Social Work, 5(1), 59–74. https://doi.org/10.1332/204986017X14835297465135

- Hoffmann, H. (2011). Warum werden Bürger Mitglied in einer Partei? In T. Spier, M. Klein, U. von Ale-mann, H. Hoffmann, A. Laux, A. Nonnenmacher, & K. Rohrbach (Eds.), Parteimitglieder in Deutschland (pp. 79–95). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Kindler, T., & Amann, K. (2021). Perspektiven einer politischen Sozialen arbeit. In K. Amann, & T. Kindler (Eds.), Sozialarbeitende in der politik: Biografien, Projekte und Strategien parteipolitisch engagierter Fachpersonen der Sozialen Arbeit (385-). Frank & Timme GmbH.

- Kindler, T., & Amann, K. (2022). Strategies of social workers’ policy engagement—a qualitative analysis Among Swiss social workers holding elected office. Journal of Policy Practice and Research, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42972-022-00058-1

- Kulke, D. (2021). Von „im Kleinen helfen“ bis zu „kritisch einmischen“: Der politische Auftrag Sozialer Arbeit und die politische Partizipation von Studierenden der Sozialen Arbeit. In A. Dischler, & D. Kul-ke (Eds.), Politische Praxis und Soziale Arbeit. Theorie, Empirie und Praxis politischer Sozialer Arbeit (pp. 139–162). Verlag Barbara Budrich.

- Lane, S. R. (2008). ‘Electing the right people’: A survey of elected social workers and candidates [Dissertation]. University of Connecticut, Connecticut.

- Lane, S. R. (2011). Political content in social work education as reported by elected social workers. Journal of Social Work Education, 47(1), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2011.200900050

- Lane, S. R., & Humphreys, N. A. (2011). Social workers in politics: A national survey of social work candidates and elected officials. Journal of Policy Practice, 10(3), 225–244.

- Lane, S. R., & Humphreys, N. A. (2015). Gender and social workers’ political activity. Affilia: Journal of Women and Social Work, 30(2), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109914541115

- Lane, S. R., & Pritzker, S. (2018). Political social work (1st ed.). Springer International Publishing AG.

- Lasswell, H. D. (1956). The decision process: Seven categories of functional analysis. University of Maryland.

- Laux, A. (2011). Was motiviert Parteimitglieder zum Beitritt? In T. Spier, M. Klein, U. von Alemann, H. Hoffmann, A. Laux, A. Nonnenmacher, & K. Rohrbach (Eds.), Parteimitglieder in Deutschland (pp. 61–78). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Leitner, S., & Löffler, E. M. (2024). Soziale Arbeit als politische akteurin in der kommune. In A. Brettschneider, S. Grohs, & N. Jehles (Eds.), Handbuch kommunale sozialpolitik. Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

- Leitner, S., & Schäfer, S. (2022). Die Vertretung von sozial benachteiligten Bevölkerungsgruppen im Gesetzgebungsprozess. WSI-Mitteilungen, 75(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.5771/0342-300X-2022-1-20

- Leitner, S., & Stolz, K. (2022). German social workers as professional politicians: career paths and social advocacy: Deutsche Sozialarbeiter(innen) in der Berufspolitik: Politische Karrieren und advokatorische Interessenvertretung. European Journal of Social Work, https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2022.2117138

- Leitner, S., & Stolz, K. (2023). „Politik als Beruf“ – Sozialprofessionelle als Mandatsträger:innen. In S. Leiber, S. Leitner, & S. Schäfer (Eds.), Grundwissen Soziale Arbeit: Vol. 47. Politische Einmischung in der Sozialen Arbeit: Analyse- und Handlungsansätze (1st ed., pp. 199–212). Verlag W. Kohlhammer.

- Löffler, E. M. (2023). Aus der Sozialen Arbeit in die Politik. Der professionelle und politische Werdegang von Sozialarbeiter:innen in der Landes- und Bundespolitik. Soziale Arbeit, 72(5), 176–183.

- Löffler, E. M. (2024). „Da muss ich mir Gehör verschaffen“. Das Wissen Sozialer Arbeit in politischen Entscheidungsprozessen. Soziale Arbeit, 73(8-9), i.V.

- McLaughlin, A. M., Rothery, M., & Kuiken, J. (2019). Pathways to political engagement. Interviews with Social Workers in Elected Office. Canadian Social Work Review, 36(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.7202/1064659ar

- Meehan, P. (2018). “I think I Can… Maybe I Can … I can’t”: Social work women and local elected office. Social Work, 63(2), 145–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swy006

- Meehan, P. (2019a). Making Change Where It Counts: Social Work and Elected Office [Dissertation]. University of Michigan.

- Meehan, P. (2019b). Political primacy and MSW students’ interest in running for office. Advances in Social Work, 19(1), 276–289. https://doi.org/10.18060/22576

- Meehan, P. (2021). Water into wine: Using social policy courses to make MSW students interested in politics. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(2), 357–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1671256

- Miller, D. B., Jennings, E., & Angelo, J. (2021). Social workers as elected officials: Advocacy at the doorstep. Journal of Social Work Education, 57(3), 455–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1671268

- Pence, E. K., & Kaiser, M. L. (2022). Elected office as a social work career trajectory: Insights from political social workers. Journal of Social Work Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.2019639

- Püttner, G. (2007). § 19 Zum Verhältnis von Demokratie und Selbstverwaltung. In T. Mann, & G. Püttner (Eds.), Handbuch der kommunalen Wissenschaft und Praxis. Band 1 Grundlagen und Kommunalverfas-sung (pp. 381–390). Springer-Verlag.

- Reiser, M. (2006). Zwischen ehrenamt und Berufspolitik: Professionalisierung der Kommunalpolitik in deutschen Großstädten. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Sachße, C. (2020). Ein Frauenberuf unter Männerregie. Zur Entwicklung der Sozialen Arbeit in Deutsch-land. In P. Hammerschmidt, J. B. Sagebiel, & G. Stecklina (Eds.), Männer und Männlichkeiten in der So-zialen Arbeit (pp. 30–43). Beltz Verlag.

- Sackmann, R. (2013). Lebenslaufanalyse und Biografieforschung: Eine Einführung (2. Aufl.). Studien-skripten zur Soziologie. Springer VS.

- Schneider, V. (2001). Sozialarbeit zwischen Politik und professionellem Auftrag: Hat sie ein politisches Mandat? In R. Merten (Ed.), Soziale Arbeit. Hat Soziale Arbeit ein politisches Mandat? Positionen zu einem strittigen Thema (pp. 26–40). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

- Schöne, H. (2020). Entscheidungsprozesse im Demokratiemodell. In A. Kost, P. Massing, & M. Reiser (Eds.), Handbuch demokratie. Sonderausgabe für die Zentralen für politische Bildung (pp. 193–205). Wochenschau Verlag.

- Scourfield, J., & Warner, J. (2022). Knowing where the shoe pinches: Three labour ministers reflect on their experiences in social work and politics. Critical and Radical Social Work, 10(3), 484–490. https://doi.org/10.1332/204986021X16521772186589

- Sorg, R. (2001). Annäherungen an die Frage, ob die Soziale Arbeit ein politisches Mandat hat. In R. Merten (Ed.), Soziale Arbeit. Hat Soziale Arbeit ein politisches Mandat? Positionen zu einem strittigen Thema (pp. 41–54). Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH.

- Weber, M. (1926). Politik als Beruf. Duncker & Humblot.

- Weiss-Gal, I. (2017). What options Do We have? Exploring Routes for Social Workers‘ Policy Engagement. Journal of Policy Practice, 16(3), 247–260.

- Welker, M., & Wünsch, C. (2010). Methoden der Online-Forschung. In W. Schweiger, & K. Beck (Eds.), Handbuch Online-Kommunikation (1st ed, pp. 487–517). VS Verl. für Sozialwiss.