ABSTRACT

This perspective paper enquires into the dynamics of justice-involved girls (JiG) residing in out-of-home foster care settings within a non-Western context, scrutinising and questioning prevailing approaches within youth justice institutions that amalgamate mediation and restorative justice methodologies. Leveraging insights garnered from firsthand encounters with JiG, I present vignettes from my fieldwork observations to illustrate scenarios where JiG experience disappointment, hence underscoring potential pitfalls associated with blended approaches. Proposing a concentric circle framework tailored to navigate the knottiness of double-mediation circumstances, particular attention is directed towards addressing JiG’s internal conflicts. Furthermore, I contend that JiG’s susceptibility to disappointment offers insights into the underlying origins of conflicts and sheds light on their struggles with self-identity within youth mediation programmes. By synthesising theoretical constructs with empirical evidence, this perspective paper offers practical guidance for researchers and social work practitioners working with JiG, while also contributing to ongoing dialogues surrounding girls’ participation in juvenile justice and youth-mediated interventions.

Introduction

This conceptual paper integrates existing scholarship on adolescents in conflict with fieldwork experiences with at-promise adolescent girls in out-of-home placements. ‘At-promise girls’ emphasises their potential and strengths, contrasting with the deficit-focused term ‘at-risk’ (Abrams, Citation2002). My goal is to advocate for a strengths-based approach to empower these girls, reframing narratives around risk and delinquency. While terms like ‘risk’ or ‘delinquency’ may still be used due to references to previous literature, my focus remains on uplifting individuals. Under the purview of ‘at-promise’, this paper specifically investigates justice-involved girls (JiG) participating in my fieldwork at a Global South institution. To uphold confidentiality and ethical agreements, the nationalities of these girls are withheld. This methodology offers a transcultural perspective on challenges in youth offending prevention mediations.

Rather than a case-study approach, I use fieldwork experiences to prompt reflection among researchers. The paper primarily examines discourse and instances of disillusionment observed during fieldwork workshops with JiG, serving as catalysts for further exploration. Specific sections argue against indiscriminate adoption of Global North strategies in the Global South context. However, literature from the Global North is still used to juxtapose with my fieldwork scenarios, elucidating discourse knottiness.

How are girls interacting with the implementation of mediation?

The United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 2250 (Citation2015) on youth, peace, and security, recognising the significant role young people play in promoting global peace and security. Despite this, critics, such as Ensor (Citation2021), have emerged challenging the discourse on global youth as peacebuilders, offering critical perspectives on its underlying assumptions and efficacy. Sukarieh and Tannock (Citation2018) have observed that ‘such arguments do not withstand scrutiny, as recent documents on global youth and security are imbued with concerns regarding youth as a threat and liability’ (p. 855). Altiok et al. (Citation2020) argue that the youth as peacebuilders ideal may exploit young people and enlist their support for the existing global social and economic structure. Additionally, scholars like Lancy (Citation2015) and MacBlain (Citation2017) suggest that existing literature on children and childhood may not fully grasp the realities faced by young individuals in peace and security initiatives. Young people must navigate various factors such as gender and age to effectively participate in these efforts. The growing interest in youth roles in conflict and peacebuilding has gained prominence globally in recent years, highlighting the need for a closer examination of juveniles’ experiences compared to adults and children.

Within the scope of JiG, there are occasional suggestions in the literature that female juveniles living in out-of-home foster care could be involved in peacebuilding efforts and youth mediation through various strategies. Firstly, the young women are afforded platforms for involvement, such as collective deliberations (Reed et al., Citation2021), inter-peer conflict resolution (Stearns & Yang, Citation2021), and endeavours directed towards the enhancement of communal bonds (Fedock & Covington, Citation2022). The second aspect involves the provision of mentorship and counselling services to these JiG, which aids in their acquisition of adaptive coping strategies and contribute to the cultivation of resilience (Downey et al., Citation2022). Lastly, the cultivation of an environment that prioritises safety and nurtures a sense of community (Morash & Hoskins, Citation2022) acts as a powerful motivator for adolescent females to actively engage in peacebuilding activities and assume leadership positions within their respective communities to advocate for stability and peaceful coexistence.

To enquire further into scholarly exploration of strategies for JiG, mediation serves as a method for resolving conflicts among disputing parties by facilitating dialogue aimed at resolving their issues, whereas restorative justice entails the acknowledgment of harm inflicted by one party upon another or a group, with the wrongdoer seeking to make reparations following an understanding of the harm caused (Aertsen, Citation2004; Dierolf et al., Citation2020). Consistent with the argument put forth by Oriol-Granado et al. (Citation2015) that ‘interventions to prevent criminal acts should be initiated as soon as the youths come into the centre’ (p. 223), certain institutions opt to blend mediation and restorative justice methods in addressing the needs of JiG, viewing this approach as a practical alternative to formal court proceedings (Attas et al., Citation2022). Some institutions integrate the two methods due to their shared focus on conflict resolution and relationship restoration. These approaches provide opportunities for affected parties to receive compensation and repair. Restorative practices prioritise restoration, reparation, and reintegration, while mediation prompts JiG to recognise responsibility and enhance relationships, aiming for future harmony. Moreover, both methods’ agreements hold legal weight, requiring adherence under threat of further prosecution, offering alternatives to formal trials and potentially diverting cases from prosecution (Aertsen, Citation2004; Mok & Wong, Citation2013). However, while this integrated approach may seem beneficial for promoting rehabilitation and reintegration while minimising the risk of recidivism, I seek to challenge its effectiveness in this article.

In alignment with McGregor and colleagues’ assertion (Citation2020) that strategies within the youth justice landscape ‘needs to be context driven, located within the complexities of time, space and place, based on parity of participation and implies more use of socio-spatial practice’ (p. 964), this paper aims to explore comparable ideas, substantiated by my observations during fieldwork, to contend that the merging practices of the two approaches do not invariably coincide and could give rise to diverse dilemmas.

The realm of enquiry: girls (together) in the system

Based on the preceding scholarly dialogue and prior to exploring the blending of the two practices, I endeavour to furnish contextual insights into my fieldwork engagement. My research milieu comprises a residential institution catering to JiG in out-of-home care, located in the Global South. Specifically used in this institution is a gender-sensitive approach to address the recognition that the experiences of JiG may vary from those of boys due to several factors such as gendered socialisation, gender stereotypes, and systemic gender inequality (Van Wormer & Bartollas, Citation2022). This approach emphasises the importance of considering the unique needs and experiences of girls in the design and implementation of interventions and programmes aimed at preventing and addressing delinquent behaviour. From a practical standpoint, at this institute, the social workers provide routine gender-specific programming, which includes addressing themes such as the development of self-esteem and self-worth and navigating relationships and boundaries. However, it is imperative to acknowledge that within the institution I researched and collaborated with, the peer relationships forged within these gender-sensitive activities incite detrimental effects that surpass the constructive ones. In actuality, the negative impacts can, at times, overshadow the positive ones.

The daily routine of JiG, which I researched, typically involves attending school, meeting with school counsellors, returning to their residential facilities, engaging with institution social workers, completing homework assignments, and communicating with their families. Given the numerous demands on their time and attention, it can be challenging for these girls to form and maintain peer relationships. In fact, the idea of developing and maintaining friendships with peers may not be at the forefront of their minds due to the various stressors and responsibilities they face on a daily basis. The numerous duties and expectations faced by these young women in out-of-home care create feelings of pressure and frustration, leading them to bond over shared grievances and complaints. This also results in the formation of a ‘collective venting space’, where the major priority of these young women is often on expressing their frustrations and demoralising encounters rather than cultivating constructive and supportive relationships. That is, an exclusively female out-of-home care facility serves as an attainable path to execute gender-sensitive programming that features bespoke conversations and activities crafted to address the unique requirements of JiG. Despite that, it is critical to comprehend that this approach entails risks as it may concurrently foment antipathy and rancour among the JiG. This echoes the concept put forth by McGregor and colleagues (Citation2020) regarding ‘the sense of disconnection many marginalised young people may feel to formal systems’ (p. 965).

From what I have gathered in my fieldwork, JiG in out-of-home care encounter a dual burden. Not only do they confront the customary feelings of despondency associated with delinquency, but they are also cognisant of the disparities in socioeconomic standing and gender roles specific to females in contemporary society. This awareness is further reinforced through gender-sensitive programming in the institute. As an illustration, during a conversation with my JiG participants concerning programming aimed at improving their comprehension of gender identity and female status, with the objective of empowering them and facilitating their growth into self-assured and self-aware young women, one of the girls said that she began to disengage from the programming halfway through. She spent less time participating in group activities and more time alone in her room. When approached by staff members, she expressed her frustration and disillusionment towards the programming. ‘What is the purpose of discussing gender and identity? It will not make any difference’, she lamented. Her experience acted as a stark prompt of the intrinsic hazards implicated in enacting gender-sensitive programming for JiG. Despite the praiseworthy intention behind the programme, it inadvertently acted as a mirror of the girls’ socially excluded position, highlighting the impediments and confinements they encountered as young women in a world that frequently disregarded their value.

The programme outlined demonstrates a fusion of mediation and restorative justice principles – the mediation aspect entails prompting JiG participants to engage in role-playing as mediators to address gender issues, alongside incorporating storytelling activities to encourage JiG to approach their individual cases with a restorative justice perspective, fostering an understanding of the harm caused and prompting them to seek reparations. However, this integration, although well-intentioned, may result in unintended confusion and marginalisation among JiG participants. The amalgamation of these two approaches creates a scenario where JiG may feel torn between conflicting roles as mediators and justice-involved individuals, leading to a sense of disorientation and marginalisation as they grapple with navigating the programme’s objectives. Moreover, the fusion of the mediator role with their justice-involved status could blur distinctions and escalate feelings of marginalisation, as JiG may encounter challenges in distinguishing their personal experiences from their role within the programme.

Ultimately, this ambiguity and potential convergence between mediation and restorative justice methodologies could hinder the programme’s efficacy in meeting the needs of JiG participants. This blending of programming reflects the argument made by Altiok et al. (Citation2020) that the portrayal of youth as mediators may exploit young individuals, as discussed earlier, and is supported by the direct quotation obtained during my fieldwork. Instead of feeling supported and validated, they may feel discontented and ostracised by the programme. Lacking clear communication channels, endeavours with noble intentions run the risk of disenfranchising the individuals they aspire to empower and nurture.

Finding meaning in fieldwork: vignettes

In this section, I aim to further synthesise insights gleaned from my fieldwork journals, using observational notes to craft two vignettes. These vignettes serve the dual purpose of fostering scholarly dialogue while safeguarding the confidentiality of the individuals involved. Preceding each vignette, I provide a concise review of pertinent literature. Subsequently, following each vignette, I offer an analytical discussion of my fieldwork observations. Additionally, a concluding section presents enquiries intended to stimulate critical reflection among researchers and practitioners.

The out-of-home institution I worked with employs community-based and strengths-based strategies to assist JiG in navigating their involvement with the criminal justice system. Specifically, they implement programmes by offering JiG with adaptable services within the neighbouring communities, departing from deficit-focused approaches, and instead, emphasising the development of constructive assets (Javdani & Allen, Citation2016). The social work practitioners and institution staff are adherents of ecological (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1992) and empowerment (Rappaport, Citation1981) theories, maintaining that the girls being served should have full autonomy in determining the focus and trajectory of the intervention. This principle is indispensable as JiG have expressed their preferred features for the intervention in a lucid manner. This aligns with the tenets of feminist scholarship, which has stressed the importance of centring the perspectives of JiG and women and acknowledging their knowledge in matters related to their lives. This out-of-home care’s intervention was designed to proactively address the immediate social surroundings of JiG to alter the circumstances of their existence, with the ultimate goal of reducing their exposure to negative influences and increasing factors that provide security.

In vignette 1, akin to a multitude of prior studies, I aim to confront the efficacy of involving JiG in community mediation endeavours as well as granting them varying roles in the promotion of peacebuilding efforts.

A school district sought to form a peer mediation programme in partnership with this juvenile justice organisation with the aim of fostering conflict resolution and promoting anti-bullying initiatives among students. The programme aimed to engage justice-involved girls as mediators, with the expectation of benefiting all parties involved. However, as the programme progressed, there were disagreements among the girls regarding the best approach to use in mediation. Some felt that a tough approach was necessary, while others favoured a more conciliatory approach. Diverging opinions led to factional struggle, where the girls became polarised into two groups, displaying a refusal to work together and exhibiting negative behaviours such as threats and disturbances.

In this vignette, JiG with deficient self-regulation present a considerable challenge in group intervention efforts as they are prone to spearheading coalitions with similarly delinquent peers, resulting in a disruptive and potentially volatile environment for other participants. Furthermore, as justice-involved adolescents ‘engage in aggressive responses because they perceive greater confidence in their abilities to engage in such behaviours than non-violent responses’ (Shetgiri et al., Citation2015, p. 8), this conduct of juvenile girls with delinquent tendencies amplify the aggressive reactions, causing the original peer mediation programme to deviate. As a result, through my observation, it became clear that the institutional personnel are compelled to address the discord and confrontations, which go beyond the routine conflict resolution practices, as delinquent behaviours are unwittingly brought from their out-of-home residential facilities into the mediation room. At this point, the conflict resolution practices become increasingly intricate due to the fact that, while the programme continues as initially intended, the participants are cognisant of the dissension and schisms among the JiG, resulting in a proliferation of conflicts beyond the original scope of the programme – the internal strife has then become the big elephant in the room.

According to empirical evidence, it has been ascertained that female adolescents exhibit a superior attentional capacity and emotional acuity, characterised by a heightened attentiveness towards emotional stimuli and an enhanced ability to accurately perceive and identify their own emotional states (Garaigordobil, Citation2020; Klimecki, Citation2019). These JiG in vignette 1 are experiencing emotional distress due to the disparity between their anticipated sense of accomplishment and the actuality of their disagreement, which is further compounded by the perception of divergent opinions held by their peers. This negative affect is leading to a state of either hostility or indifference among the youth, causing a halt in the peer mediation programme and necessitating intervention by the programme staff to mitigate the conflicts. From this vignette, it can be inferred that conflicts of a pre-existing nature have emerged, which require the girls’ active attention. These antecedent conflicts are serving as a distraction, diverting the collective focus of the group, and rendering their efforts ineffectual. Another contributing factor is the continuation of programming beyond the scope of community mediation efforts. Rather than ceasing these endeavours once they extended beyond community mediation, institutional staff concurrently engaged JiG in new rehabilitative activities to address their negative behaviours. This dual-track programming approach exacerbates the aforementioned confusion experienced by JiG.

The context depicted here does not insinuate that the integration of JiG in mediation programmes is irrevocably bound to be unsuccessful. Instead, I am posing interrogatives and occurrences during the discussions to contest the fundamental orientation of said programmes. To explicate the assorted affective reactions and sentiments that may be evinced by the JiG during the mediation proceedings, vignette 2 is presented for contemplation. As asserted by McGuire et al. (Citation2021), productive involvement in community activities ‘is a salient indicator of developmental growth and positive community adjustment’ (p. 2993), particularly for youth who have encountered the justice system. The mediation depicted in vignette 2 serves as a restorative community service programme, which aligns with the effort to revamp the application of community service among juvenile populations (Church et al., Citation2021). This initiative is founded on the provision of more substantial work opportunities and an emphasis on augmenting community involvement.

Local governmental agency and the juvenile justice organisation collaborated to establish a diversion programme that incorporated justice-involved girls as mediators. The objective of the programme was to channel young individuals away from the criminal justice system and towards community service or mentoring. Nevertheless, as the programme advanced, the young women observed that when they committed errors or behaved inappropriately, the community adults and social workers swiftly criticised and rebuked them. Conversely, when non-delinquent peers exhibited analogous misbehaviour, they received more clement treatment. This ethical inconsistency led to the girls feeling singled out and marginalised. Consequently, the justice-involved girls’ enthusiasm for participation diminished as they began to resent the adult authorities within the programme. Moreover, their discontent amplified when they discerned that they were not provided opportunities to voice their opinions or concerns. The adults made decisions unilaterally, neglecting to seek input from the young women, leaving them feeling unheard and insignificant.

As JiG face additional challenges as they carry latent stigmas (Humberstone, Citation2019; Kerig & Becker, Citation2012) and are subjected to particular societal presumptions, it is conceivable that these JiG experience intensified levels of strain upon entering the mediation programme described in the vignette, given their perception of the fundamental differences that set them apart from their non-delinquent peers. Adolescents are in the process of shaping their identities and undergoing social and cognitive development (Klausmeier et al., Citation2014), and they are amenable to interventions. In the context of joint assignments that predominantly involve adolescents, the phenomenon of peer pressure tends to emerge and consequently elicits deleterious consequences (Clasen & Brown, Citation1985), including conformist conduct, the ostracism of select group members, diminished quality of output, and elevated predisposition towards reckless behaviour. This dynamic may also precipitate a curtailment of originality and independent thinking, as individuals may feel compelled to adhere to the norms and beliefs espoused by the collective. In instances where certain non-delinquent peers exhibit a proclivity for taking the lead or simply articulating dissimilar perspectives, certain JiG are inclined to misconstrue these communications and construe them in a negative light. Moreover, I also identified that in the fieldwork, another cohort of JiG who express receptivity towards working alongside the non-delinquent peers in mediating conflicts must subsequently acquiesce to the dissatisfied individuals solely due to their affiliation with the ‘delinquent squad’, and noncompliance would lead to peer-based isolation.

What is additionally pertinent is the research conducted by Levey et al. (Citation2019). Adolescents with a reduced sense of self-concept clarity may be more vulnerable than their peers to the influence of their friends’ actions. Notably, self-concept clarity acted as a significant moderator in the correlation between an adolescent’s level of delinquency and that of their closest friend. Higher levels of self-concept clarity were found to weaken the association between an adolescent’s delinquent behaviour and that of their friends. In the vignette, certain JiG of the programme have displayed diminished levels of self-concept clarity, rendering them more prone to the sway of their respective subgroups. It is then vital to consider the degree of self-concept clarity demonstrated by each adolescent when developing mediation interventions aimed at promoting positive social interactions. This evaluation is essential to identify those who are more susceptible to external influences, and thereby provide the necessary support to enable them to fully participate in the programme. Furthermore, it could be the duty of programme designers to separate these individuals from those who project a negative outlook on non-delinquent peers and attempt to impose their viewpoints on the group, from those who do not. By implementing such measures, all adolescent participants will be better able to engage in positive, community-based mediation activities, thus facilitating a more constructive resolution of any conflicts that may arise.

Once again, the intention behind this programming was commendable, aiming to involve JiG as mediators to engage with their peer girls. However, the effectiveness of this initiative is contingent upon contextual considerations, particularly within the framework of restorative justice and the communities these JiG are expected to serve. A notable disparity arises in the perceptions of JiG and their non-delinquent counterparts regarding the community. While the neighbourhood and community hold neutral or commonplace significance for non-delinquent girls, they evoke sensitivity and complexity for JiG. Prior to their involvement in collaborative projects, JiG have already participated in restorative justice endeavours, familiarising themselves with the process of making amends to the neighbourhood and community during their institutional stay. Consequently, when tasked with collaborating with non-delinquent peers in the same neighbourhood and community, JiG encounter cognitive dissonance, as they navigate between the demands of restorative justice and the mediator role within the programming framework. Regarding the detrimental impact of peers on one another, a social worker involved in my fieldwork has communicated their stance:

‘The more you try to mix two things together with a purpose, the more the differences become apparent when the two groups finally come together’ (anonymous social worker).

Even with noble intentions at the outset to facilitate interaction between JiG and non-delinquent girls, their differences inevitably manifest. As articulated by the social worker above, sensitive JiG may still discern disparities between themselves and non-delinquent peers, resulting in feelings of marginalisation and disempowerment. The amalgamation of heterogeneous groups can precipitate a sudden surge in disorder, analogous to the mixing of gases or liquids that leads to an increase in entropy. Consequently, it behoves social workers and community-based mediation programme planners to thoughtfully contemplate the potential escalation of confusion or entropy before advancing with the integration of these distinct groups of adolescents. Also, the coexistence of mediator activities alongside restorative justice initiatives warrants reconsideration, as this amalgamation could give rise to bewilderment among JiG. It is advisable to maintain a clear distinction between these two activities, as they serve distinct purposes and could be implemented separately.

A concentric circle of double-mediation circumstances

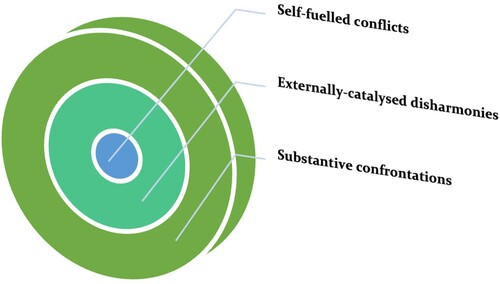

The two vignettes underscore a predicament in this context. The aim of the diversionary initiative that assimilated JiG as mediators is to obfuscate the demarcations between the ‘good’ and ‘bad’ girls, and to endow a prospect for reformation and favourable modification in demeanour. However, the programme was sidetracked in both scenarios due to the fusion of mediation and restorative justice, resulting in internal conflicts arising long before the actual challenges that both the JiG and programme staff were tasked with resolving. Consequently, I posit a concentric circle of dual-mediation contingencies to establish a paradigm for safeguarding the mediator roles of JiG in community-based interventions, as well as apprising the adults involved in the programme to remain mindful of the group dynamics and interaction between the institutional faction and the adolescent cohort. Please see below .

Figure 1. A concentric circle of dual-mediation contingencies for JiG’s community-based programmes and social interventions. Figure created by the author.

The genesis of this concentric circle is inspired by the enquiry performed by Rankine et al. (Citation2018), wherein they designed a multi-layered framework to provide a comprehensive perspective of the primary sources’ yearnings for introspective oversight and factual execution of practices in community-based child welfare services. Analogous to the necessity for social workers to cultivate self-awareness and establish their individual identity primarily in reflective supervision at the foundational layer, JiG must also address internal conflicts of self-perception, insecurity, and institutional struggles before engaging in mediation. The self-fuelled conflicts are persistent underlying issues, but community-based mediation programmes that ‘incorporate multiple system levels and inter-sectorial and interprofessional collaborations’ (Saltkjel et al., Citation2023, p. 67) can inadvertently exacerbate these issues, creating additional conflicts that must be resolved. Neglecting to consider the fluctuating and enduring nature of each girl’s self-identity in mediation programmes is akin to grouping individuals with myriad enquiries and anticipating autonomous resolution of their concerns.

I am not positing that the participation of JiG in mediation programmes is contingent upon their resolution of all internal conflicts pertaining to self-awareness and identity. Rather, I am elucidating the inadequacies in community-based interventions in mitigating individual and internal conflicts, a concept previously advocated by Openjuru and colleagues (Citation2015) in the realm of community-based activities. These interventions frequently neglect the Southern origins of such processes, instead imposing hegemonic Northern concepts. Within the context of my fieldwork, I assert that mediation programme planners ought to prioritise comprehension of the backgrounds and requirements of the participating youth. This entails reconsidering the adoption of purported ‘success panacea’ strategies depicted within the literature emanating from the Global North.

The second stratum of Rankine and fellow researchers’ reflective supervision framework pertains to the adeptness of constructing and preserving working relationships with clients, colleagues, and other professionals. Likewise, JiG are inevitably compelled to cooperate with others – whether their peers or adults – in mediation programmes, and heightened interactions engender greater potential for dissonance. Although scholarly literature underscores the role of social interactions in fostering social bonds, crucial for shaping adolescents’ community belonging and predicting positive developmental outcomes (Jason et al., Citation2015; Lardier et al., Citation2019), JiG are acutely aware of the imperative to engage in collaborative efforts within mediation settings. Nevertheless, they continue to confront both implicit and explicit stigmatisation linked to their behaviour. Furthermore, the peer dynamics mentioned earlier persist as enduring influences.

Turning attention to the subsequent layer, termed externally-catalysed disharmonies, Harnett and Jönson (Citation2022) discuss the implications of reframing and recalibrating activities in the context of the concept of ‘master status’. The concept was first introduced by Hughes (Citation1945) and expanded upon by Becker (Citation1973), who posited that certain negative social statuses have the power to supersede all other identities and strongly shape how an individual is perceived by others. The master status in this context refers to an externally-catalysed disharmony that impacts the experience of JiG in mediation. The disruption stems from conflicts that originate within the group. As a case in point, in my fieldwork, JiG raised concerns regarding the institutional transportation provided for their conveyance to and from the community-based programme. The prominently displayed name of the residential out-of-home foster care on the bus creates a stigmatising effect, leading to social isolation and marginalisation for the girls. Another instance of JiG’s grievances pertains to the limitations imposed on the duration for which they are allowed to use their mobile phones, hindering their ability to stay current with trends among their peers and impacting their interacting in the mediation programme, where technological pedagogies require mobile devices as a tool for education. Both the bus and cellphone usage period are externally-catalysed disharmonies. The instances serve to underscore the recurrent setbacks that these adolescent females confront in establishing ‘connections, bonds, and relationships that may involve a different number of actors and different types of relationships’ (Rodríguez & Ferreira, Citation2018, p. 865) within a community-mediated setting, and how these setbacks continue to impinge upon their sense of self-worth, consequently disaffecting their enthusiasm to engage actively in the mediation process. This exhibits a bidirectional interaction between internal and external conflicts, wherein each variable reciprocally influences and amplifies the other.

Returning to , the substantive confrontations which the adolescent mediators aim to resolve can be envisaged as wheels that drive the entire mediation programme. In this analogy, the externally-catalysed disharmonies are akin to a large, controlling gear that determines the direction of the programme. Meanwhile, the self-fuelled conflicts function as the core gear at the centre of this machinery, exerting a profound influence on all aspects of the mediation. If the core gear is damaged or malfunctioning, it can impact the controlling gear and subsequently cause the entire system to move in a lopsided or incorrect direction. As ‘conflicts are part of our daily life and daily professional practice’ (Jensen, Citation2018, p. 327), a well-designed mediated intervention does not eschew conflicts. Instead, it attends to the individual JiG’s self, not just the group dynamics or the overall programme progression, as it discerns the big picture from minute particulars.

Programme planners ought to acknowledge that the precise calibration and optimal orientation of the core gear (self-fuelled conflicts) are paramount to the efficacious functioning of the controlling gear (externally-catalysed disharmonies), thereby dictating the trajectory (substantive confrontations) of the mediation initiative. That is, in the self-fuelled conflicts pertain to the absence of self-confidence or self-respect, a sense of detachment from the society, a sense of disorientation, or uncertainty regarding one’s self-concept among JiG. These issues will invariably be at the nucleus of the mediation efforts. It is imperative for programme staff to prioritise the girls’ self-identity predicaments, regardless of the subject matter under discussion in the programme and its current stage.

I intend to culminate this discussion by revisiting the amalgamated approaches of mediation and restorative justice used by youth justice organisations, as initially introduced at the outset of this paper. Both the provided vignettes and the concentric circle illustrating dual-mediation contingencies for JiG exemplify potential deviations from intended outcomes when integrating mediation and restorative justice approaches in work with JiG. A reevaluation of the integration of mediation and restorative justice approaches in interventions with JiG is then warranted, necessitating a discerning approach that distinguishes between these modalities. I posit that rather than conflating these methodologies into combined activities with dual orientations, a judicious deployment predicated on contextual considerations is advisable. Practical strategies for researchers and practitioners to distinguish between these two approaches include:

Establishing tailored assessment tools: Researchers and practitioners should develop specialised assessment instruments to evaluate the suitability of mediation or restorative justice approaches based on the unique characteristics of each conflict scenario. These tools should consider factors such as the nature and severity of the offence, the parties involved, and the desired outcomes to guide decision-making and ensure the appropriate application of each methodology. In parallel with the situation illustrated in vignette 1, should institutional personnel discern the need to JiG in additional rehabilitative initiatives to mitigate their adverse behaviours, they should halt the ongoing community mediation initiatives, rather than simultaneously pursuing both endeavours.

Providing specialised training and professional development opportunities: It is essential to offer targeted training and ongoing professional development opportunities for staff involved in implementing mediation and restorative justice interventions. This training should encompass not only the theoretical foundations and principles of each approach but also practical skills development, such as facilitation techniques, communication strategies, and conflict resolution methodologies. By providing practitioners with requisite knowledge and competencies, institutions are less likely to devise such ambitious undertakings as described in vignette 2 and can preempt the circumstances delineated therein, thereby augmenting the efficacy of their mediation and restorative justice initiatives.

Promoting interdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge exchange: Encouraging interdisciplinary collaboration and knowledge exchange among researchers, practitioners, and stakeholders across a broad spectrum of fields, such as psychology, social work, law, and criminology, is essential. This initiative fosters collaboration spanning disciplines, thus capitalising on an array of perspectives, insights, and expertise to innovate youth justice interventions. Through the facilitation of interdisciplinary collaboration, organisations can enhance their capacity to discern between mediation and restorative justice practices and determine which expertise to consult. This approach not only enriches their comprehension of these methodologies but also facilitates evidence-based decision-making processes, therefore propelling advancements in youth justice research and practice.

Seconding the notion proposed by Lancy (Citation2015) and MacBlain (Citation2017) in the initial passages of this article, I further argue that within juvenile settings, mediation should be exclusively deployed for mitigating intragroup conflicts among JiG. This strategic emphasis on conflict resolution skills and dialogic processes within the institutional milieu holds potential for empowering participants to address interpersonal discord constructively. Conversely, restorative justice mechanisms should be reserved for extramural engagements, affording JiG the opportunity to participate in modalities such as victim-offender mediation or family group conferencing (Schout, Citation2022). Such an approach fosters their acknowledgment of accountability, comprehension of the repercussions of their actions, and active involvement in formulating meaningful restitution strategies. By advocating for the discrete application of mediation and restorative justice methodologies within their respective domains, a nuanced framework can be cultivated that foregrounds the needs and rehabilitation imperatives of JiG, concurrently nurturing conducive relationships and facilitating their societal reintegration.

The prevalence of anger in girls

In this article, I use the concept of entropy alongside terms like ‘fuelled’ and ‘catalysed’ within the double-mediation framework. These concepts are rooted in the conversion of energy from one form to another. When JiG struggle to channel their anger constructively, it becomes internalised, leading to emotional and behavioural instability (Kelly et al., Citation2019). Similar to energy conversion, managing and redirecting their anger requires considerable effort. This involves providing mediation techniques and resources to help them express their emotions constructively, transforming negative actions into positive ones. Concerning the expectation for women to suppress their anger and the subsequent internalisation of this emotion leading to disappointment, Chemaly (Citation2018) expounds thusly: ‘It took me too long to realise that the people most inclined to say “You sound angry” are the same people who uniformly don’t care to ask “Why?” They’re interested in silence, not dialogue’ (p. 23). From my fieldwork experiences, it is observable that JiG often exhibit emotional dysregulation and are particularly susceptible to feelings of disappointment. However, it is vital to grasp that these manifestations may be indicative of their deeply rooted feelings and experiences and represent a unique form of communication that deserves social work practitioners and institution’s validation and reflection.

The mediation programme for JiG is not only intended for creating collective transformative processes but also for the identification of each adolescent girl’s inner struggles pertaining to self-identity. Utilising the concentric circle of dual-mediation contingencies in community-based programmes and social interventions for JiG is beneficial due to the omnipresence of conflicts and the inexorable demonstration of conflicts in JiG, necessitating preparation. In response to Jensen’s enquiries (2018), ‘can we resolve all sorts of conflicts, and should we?’ (p. 328) In the realm of working with JiG in youth-led mediation involvements, yes and yes – it is both feasible and necessary. However, rather than directly addressing and resolving conflicts, it is more effective to employ mediation and restorative justice methods individually within their respective contexts. This approach allows for the development of a multifaceted structure that prioritises the needs and rehabilitation requirements of JiG, while also fostering supportive relationships and facilitating their re-assimilation into society. Additionally, a sidenote from my fieldwork underscores that the prevailing literature and methodologies from the Global North may not be universally applicable remedies, irrespective of whether the juvenile justice context is in the Global North or South. It is the youth and their contextual backgrounds, in conjunction with the selection of mediation and restorative justice techniques, that are fundamental components.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sheng-Hsiang Lance Peng

Sheng-Hsiang Lance Peng is a PhD candidate at the Education Faculty of the University of Cambridge, where he explores his passion for hauntology by using its frameworks to explore marginalised narratives at the crossroads of education and social work within his PhD research project.

References

- Abrams, L. S. (2002). Rethinking girls “at-risk”: Gender, race, and class intersections and adolescent development. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 6(2), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1300/J137v06n02_04

- Aertsen, I. (2004). Rebuilding community connections-mediation and restorative justice in Europe. Council of Europe.

- Altiok, A., Berents, H., Grizelj, I., & McEvoy-Levy, S. (2020). Youth, peace, and security. In F. O. Hampson, A. Özerdem, & J. Kent (Eds.), Routledge handbook oF peace, security and development (1st ed., pp. 433–447). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351172202-38

- Attas, N. H., Nasir, C., Saputra, T. E., & Gilang, A. (2022). Realizing restorative justice through mediation. Journal of Indonesian Scholars for Social Research, 2(2), 243–248.

- Becker, H. S. (1973). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance (Paperb. ed., 29th impr). Free Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). Ecological systems theory. In Six theories of child development: Revised formulations and current issues. (pp. 187–249). Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Chemaly, S. L. (2018). Rage becomes her: The power of women’s anger. Simon & Schuster.

- Church, A. S., Marcus, D. K., & Hamilton, Z. K. (2021). Community service outcomes in justice-involved youth: Comparing restorative community service to standard community service. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 48(9), 1243–1260. https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548211008488

- Clasen, D. R., & Brown, B. B. (1985). The multidimensionality of peer pressure in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14(6), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02139520

- Dierolf, K., Hogan, D., Van der Hoorn, S., & Wignaraja, S. (Eds.) (2020). Solution focused practice around the world. Routledge.

- Downey, S. K., Lyons, M. D., & Williams, J. L. (2022). The role of family relationships in youth mentoring: An ecological perspective. Children and Youth Services Review, 138, 106508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2022.106508

- Ensor, M. O. (Ed.) (2021). Securitizing youth: Young people’s roles in the global peace and security agenda. Rutgers University Press.

- Fedock, G., & Covington, S. S. (2022). Strength-based approaches to the treatment of incarcerated women and girls. In C. M. Langton & J. R. Worling (Eds.), Facilitating desistance from aggression and crime (1st ed., pp. 378–396). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119166504.ch16

- Fiske, S. T. (2002). What We know Now about bias and intergroup conflict, the problem of the century. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11(4), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00183

- Garaigordobil, M. (2020). Intrapersonal emotional intelligence during adolescence: Sex differences, connection with other variables, and predictors. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 10(3), 899–914. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10030064

- Harnett, T., & Jönson, H. (2022). Enabling positive framings of stigmatised settings: A neglected responsibility for social work. European Journal of Social Work, 25(2), 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2021.1918065

- Hughes, E. C. (1945). Dilemmas and contradictions of status. American Journal of Sociology, 50(5), 353–359. https://doi.org/10.1086/219652

- Humberstone, E. (2019). Friendship networks and adolescent pregnancy: Examining the potential stigmatization of pregnant teens. Network Science, 7(4), 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1017/nws.2019.25

- Jason, L. A., Stevens, E., & Ram, D. (2015). Development of a three-factor psychological sense of community scale: Sense community scale. Journal of Community Psychology, 43(8), 973–985. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21726

- Javdani, S., & Allen, N. E. (2016). An ecological model for intervention for juvenile justice-involved girls: Development and preliminary prospective evaluation. Feminist Criminology, 11(2), 135–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557085114559514

- Jensen, N. R. (2018). Conflict resolution for the helping professions (second edition). European Journal of Social Work, 21(2), 327–328. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2017.1421122

- Kelly, E. L., Novaco, R. W., & Cauffman, E. (2019). Anger and depression among incarcerated male youth: Predictors of violent and nonviolent offending during adjustment to incarceration. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(8), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000420

- Kerig, P. K., & Becker, S. P. (2012). Trauma and girls’ delinquency. In S. Miller, L. D. Leve, & P. K. Kerig (Eds.), Delinquent girls (pp. 119–143). Springer New York. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-0415-6_8

- Klausmeier, H. J., Allen, P. S., & Edwards, A. J. (2014). Cognitive development of children and youth: A longitudinal study. Elsevier Science.

- Klimecki, O. M. (2019). The role of empathy and compassion in conflict resolution. Emotion Review, 11(4), 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919838609

- Lancy, D. F. (2015). The anthropology of childhood: Cherubs, chattel, changelings (Second edition). Cambridge University Press.

- Lardier, D. T., Opara, I., Bergeson, C., Herrera, A., Garcia-Reid, P., & Reid, R. J. (2019). A study of psychological sense of community as a mediator between supportive social systems, school belongingness, and outcome behaviors among urban high school students of color. Journal of Community Psychology, 47(5), 1131–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22182

- Levey, E. K. V., Garandeau, C. F., Meeus, W., & Branje, S. (2019). The longitudinal role of self-concept clarity and best friend delinquency in adolescent delinquent behavior. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(6), 1068–1081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-00997-1

- Levine, J., & Hogg, M. (2010). Encyclopedia of group processes & intergroup relations. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412972017

- MacBlain, S. (2017). Contemporary childhood (1st ed.). Sage Pub.

- McGregor, C., Brady, B., & Chaskin, R. J. (2020). The potential for civic and political engagement practice in social work as a means of achieving greater rights and justice for marginalised youth. European Journal of Social Work, 23(6), 958–968. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2020.1793109

- McGuire, K., Kliewer, W., Lowery, P. G., Lotze, G. M., & Jäggi, L. (2021). Risk factors, promotive factors, and gainful activity in a sample of youth engaged in delinquent behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(12), 2992–3004. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02085-0

- Mok, L. W. Y., & Wong, D. S. W. (2013). Restorative justice and mediation: Diverged or converged? Asian Journal of Criminology, 8(4), 335–347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-013-9170-6

- Morash, M., & Hoskins, K. M. (2022). Effective community interventions for justice-involved girls and women in the United States. In S. L. Brown & L. Gelsthorpe (Eds.), The wiley handbook on what works with girls and women in conflict with the Law (1st ed., pp. 256–266). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119874898.ch18

- Openjuru, G. L., Jaitli, N., Tandon, R., & Hall, B. (2015). Despite knowledge democracy and community-based participatory action research: Voices from the global south and excluded north still missing. Action Research, 13(3), 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750315583316

- Oriol-Granado, X., Sala-Roca, J., & Filella Guiu, G. (2015). Juvenile delinquency in youths from residential care. European Journal of Social Work, 18(2), 211–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2014.892475

- Rankine, M., Beddoe, L., O’Brien, M., & Fouché, C. (2018). What’s your agenda? Reflective supervision in community-based child welfare services. European Journal of Social Work, 21(3), 428–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2017.1326376

- Rappaport, J. (1981). In praise of paradox: A social policy of empowerment over prevention. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00896357

- Reed, L. A., Sharkey, J. D., & Wroblewski, A. (2021). Elevating the voices of girls in custody for improved treatment and systemic change in the juvenile justice system. American Journal of Community Psychology, 67(1–2), 50–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12484

- Rodríguez, M. D., & Ferreira, J. (2018). The contribution of the intervention in social networks and community social work at the local level to social and human development. European Journal of Social Work, 21(6), 863–875. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2018.1423551

- Saltkjel, T., Andreassen, T. A., Helseth, S., & Minas, R. (2023). A scoping review of research on coordinated pathways towards employment for youth in vulnerable life situations. European Journal of Social Work, 26(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2021.1977249

- Schout, G. (2022). Into the swampy lowlands. Evaluating Family Group Conferences. European Journal of Social Work, 25(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2020.1760796

- Shetgiri, R., Lee, S. C., Tillitski, J., Wilson, C., & Flores, G. (2015). Why adolescents fight: A qualitative study of youth perspectives on fighting and its prevention. Academic Pediatrics, 15(1), 103–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2014.06.020

- Stearns, A. E., & Yang, Y. (2021). Women’s peer to peer support inside a jail support group. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(11), 3288–3309. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211030333

- Sukarieh, M., & Tannock, S. (2018). The global securitisation of youth. Third World Quarterly, 39(5), 854–870. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2017.1369038

- UNSCR. (2015). Resolution 2250. United Nations Security Council. https://documents-dds-ny.un.org/doc/UNDOC/GEN/N15/413/06/PDF/N1541306.pdf?OpenElement

- Van Wormer, K. S., & Bartollas, C. (2022). Women and the criminal justice system: Gender, race, and class (Fifth edition). Routledge.