ABSTRACT

This article analyses European integration's effects on migration and border security governance in Slovenia, Croatia and Macedonia in the context of ‘governed interdependence’. We show how transgovernmental networks comprising national and EU actors, plus a range of other participants, blur the distinction between the domestic and international to enable interactions between domestic and international policy elites that transmit EU priorities into national policy. Governments are shown to be ‘willing pupils’ and ‘policy takers’, adapting to EU policy as a pre-condition for membership. This strengthened rather than weakened central state actors, particularly interior ministries. Thus, in a quintessentially ‘national’ policy area, there has been a re-scaling and re-constitution of migration and border security policy. To support this analysis, social network analysis is used to outline the composition of governance networks and analyse interactions and power relations therein.

Introduction

This article develops a comparative analysis for three South East European (SEE) countries (Slovenia, Croatia and Macedonia) of the effects of European integration on migration and border security governance. It explores the consequences of EU requirements in these policies on the core executive in the case countries and the effects of ‘governed interdependence’ (Weiss Citation1998) in a region where the EU and European integration are central to debates about migration and border security, debates that have become focused on the EU's external frontiers and on new and prospective member states. Social network analysis (SNA) is used to specify the content of ‘transgovernmental networks’, comprising national and EU officials, plus a range of other actors, such as international organisations, that transmit EU priorities to prospective member states (Slaughter Citation2009).

The idea of governed interdependence is a particularly useful way of thinking about the issues of migration management and border security because it counters the ‘myth of the powerless state’ (Weiss Citation1998) and directs attention towards the reconstitution of state authority and the EU's role in this reconstitution, or as Weiss (Citation1998, 3) puts it: ‘the adaptability of states, their differential capacity, and the enhanced importance of state power in the new international environment’. We show how, under conditions of governed interdependence, each of our cases has been a ‘policy taker’ required to adapt to EU policy as a pre-condition for access to the wider benefits of membership. This has strengthened rather than weakened central state actors, notably interior ministries. We explore the re-scaling and re-constitution of migration and border security policy and what this means for the dynamics of policy in SEE and for the networks of transgovernmental action characteristic of this policy field.

In order to specify the conceptual and empirical dimensions of state adaptation to European integration, the paper explores the network basis of governed interdependence. SNA puts flesh on the bones of the network metaphor by showing the composition and relational aspects of these governance networks. When studying networks, we refer to attempts to represent interactions (number, scope and intensity) between ministers, officials from national, regional and international organisations. At the least, such interactions represent a change in the strategic context of decision-making on migration, but, drawing from interview material, we also show that they can prompt new, shared understandings of challenges of ‘Europeanised’ migration governance. The notion of transgovernmentalism is helpful because it cuts through a stale intergovernmental versus supranational dichotomy in EU studies and, instead, focuses attention on how forms of co-operation and interaction lead to specific forms of exchange, such as the sharing of information, knowledge and experiences between officials and a wide range of organisations including member states, but also other actors such as international organisations (Keohane and Nye Citation1977).

To develop its argument, the article first explores the debate on inter-state co-operation on migration to show that accounts that focus only on the more instrumental motives for co-operation can miss the social dynamics that occur as a result of regular interactions. We do so by exploring the debate about the EU's ‘transformative’ effects on new and prospective member states (Börzel and Risse Citation2012). The article then develops its empirical analysis by analysing the dynamics of co-operation in the three case countries to demonstrate the conditions under which inter-state co-operation occurs in the shadow of ‘fortress Europe’ and its effects, particularly on the executive branch of government. The time period for the analysis is 2008–2010 selected in order to test differing exposure to the EU migration acquis: Slovenia joined the EU in 2004; Croatia was in the process of joining the EU and under intense adaptational pressure (it joined in summer 2013); and, Macedonia was (and still is) negotiating membership. None is a major migrant destination country, but all developed new migration laws and administrative structures as a consequence of their relationship with the EU (Taylor, Geddes, and Lees Citation2012, Chapter 5). Our focus is on migration and border security policy that concern rules governing the entry and residence of third country nationals (TCNs). Border security policy focuses on the development of controls and checks at land-, air- and seaports to regulate access to a state's territory to those with the appropriate permission to enter. For reasons of space and because of the complexity of the issues, we do not assess the asylum issue, but do recognise the important connections between migration and asylum; not least that efforts to enhance border security can make it more difficult for asylum-seekers to access the asylum process in EU member states.

Governing migration in SEE

This section explores the relationship between migration, governance and ‘state capacity’ in the context of governed interdependence in Europe. These are key issues for the EU in terms of both its internal governance, where EU laws on aspects of migration create a rule-bound context with an emergent common EU migration and asylum policy (covering some but not all aspects of policy), and the EU's external relations with prospective member states and non-member states that lie beyond the remit of EU laws and have a more intergovernmental character (Lavenex Citation2006; Boswell and Geddes Citation2011). Each of the three countries analysed is more notable as a country of emigration rather than immigration but there are also important legacies of movement (both voluntary and involuntary) within the ex-Yugoslav federation and as a result of the displacement arising from the conflicts of the 1990s. As already noted, none of the three case countries are major destination countries. In 2008, 3.3% of the population of Slovenia were TCNs, compared to 1.5% in Croatia and 0.7% in Macedonia. Migration had a strong intra-regional dimension. For example, in Slovenia in 2008, 47.3% of TCNs were from Bosnia–Herzegovina with 20.1%, 10.9% and 10.2% from Serbia, Macedonia and Croatia, respectively (Eurostat Citation2009).

Despite these very particular migration dynamics with a strong intra-regional dimension, the focus of this article is on the ways in which the EU seeks to re-constitute migration as a challenge of governance (Trauner Citation2011, 17–33). We understand governance to possess a ‘dual meaning’ as an empirical manifestation of state adaptation and the conceptual representation of social systems with the core purposes of governance being the provision of safety, prosperity, coherence, stability and continuation (Pierre Citation2000, 3). These purposes are not necessarily connected with a particular form or location of governmental authority and may be pursued by national governments or by a range of public and private institutions and organisations at sub-national, national and international levels. Their pursuit may become tied to particular understandings of ‘good governance’, which also means that the analysis of governance is not merely a technical exercise because of its implications for the distribution of power.

While international migration is often represented as a challenge (or threat) to governance, we argue that it is more appropriate to think of it as a challenge of governance because international migration is constituted and conditioned by the borders and boundaries of states (Zolberg Citation1989). The governance of migration in SEE thus cuts across what Rosenau (Citation1997) termed the ‘domestic-foreign Frontier’ and is also reflective of what Heisler (Citation1992) identified as a key feature of international migration as an issue in international politics; namely that it is simultaneously a societal and an international issue and needs to be analysed across these levels.

The notion of the network has become a powerful metaphor within analyses of governance. We aim to develop this metaphor by specifying more precisely through the use of SNA the composition of governance networks and power relations therein. This requires some explanation of this methodological choice and its theoretical implications. SNA permits systematic analysis and ‘thicker’ description of networks and why they are as they are. This article draws from 35 detailed semi-structured interviews in the case countries and at the EU level. Additionally within these interviews, a structured questionnaire asked respondents to identify the organisations with which they interacted and to estimate the frequency and intensity of interaction.Footnote1 Our unit of analysis is not the actor but interaction between actors within the network. The data from the semi-structured component of the interview allowed us to explore ‘situated agency’ with recognition that agency is situated ‘within a social context that influences it’ (Bevir and Rhodes Citation2003, 4). Power and influence flow from network relationships, which are the product of engagement with the EU.

Barnett and Duvall's (Citation2005) relational conceptualisation of power in global governance informs our approach. Power relations can involve a compulsory component that is without doubt an important dynamic for countries required to adapt to the EU acquis as a condition for membership. We also find evidence of institutional power as EU influence shapes domestic institutional formation in the three countries. Structural forms of power are evidenced by the diffusion of ideas about migration located within EU migration management. Finally, the more productive or discursive aspects of the relational view of power developed by Barnett and Duvall are evident in the social and communicative logics associated with the transgovernmental networks in the field of migration and border security. To sum up, the beliefs and actions of individuals within these networks are not independent; rather they are located within the social and political contexts of network relations that are the product of EU rules and preferences interacting with the national context.

As will be seen, the three ‘domestic’ migration and border security networks have a transnational orientation and ‘interlock’ in response to specific EU policy requirements. The focus for SNA is the causes and consequences of the connections among a system's elements. Our analysis was particularly interested in the ways in which position in the network affects both the definition and control of the policy agenda. The SNA, supplemented by material from the semi-structured interviews, allowed us to explore in more detail the relational aspects of the networks, that is, not only to map the nodes and identify relationships, but also to explore the nature of these relationships. This allows us to go beyond the notion of network as an organisational mode by assessing the relational characteristics of networks insofar as they affect the determination of policy agendas (Hafner-Burton, Kahler, and Montgomery Citation2009). We thus understand networks as lying between states with their hierarchical character and markets that centre on a ‘more ephemeral bargaining relationship’ and see them as ‘sets of relations that form structures, which in turn may constrain or enable agents’ (Hafner-Burton, Kahler, and Montgomery Citation2009, 559–560).

There is insufficient space to recount in detail developments at the EU level or regionally in the area of migration and border security (see, e.g. Geddes Citation2008; Boswell and Geddes Citation2011 and on SEE, see Taylor, Geddes, and Lees Citation2013), but it is important to note that in the area of border security prospective, member states must demonstrate their capacity to conform to the provisions of the Schengen Borders Code (SBC), Article 6 of which specifies the mechanisms through which states are expected to regulate access to their territory: possession of a valid identity card; a valid visa (if required); justification of the purposes of the stay; means of subsistence for stay, onward travel or return; no alert on the Schengen Information System; and no threat to public order, health or safety. It is the capacity of a state to adapt to, and implement, these requirements that is an essential component of EU membership. Slovenia adapted to this acquis prior to its membership in 2004, Croatian accession was predicated upon adaptation, while Macedonian membership will depend on adaptation demonstrating the state's capacity to regulate territorial access. Visa liberalisation has also been a carrot dangled in front of prospective member states. Both Croatia and Macedonia benefited from such an arrangement that serves as a practical manifestation of the movement towards the EU migration and border security framework.

The key intended EU impact on new member states relates to the issue of state capacity. In the simplest of terms, capacity is the ability to attain objectives. Geddes and Taylor (Citation2013) distinguish between three dimensions of state capacity: a functional dimension adds an EU dimension to domestic policy debate that can provide external impetus to internal policy change; a political dimension means the development of ‘better’ policy in the context, for example, of securing the wider objective of EU membership; and, finally, an administrative dimension allows for the inclusion of national officials within new regional and international governance networks. Each of these three dimensions can strengthen domestic capacity, although each is predicated upon a particular understanding of the policy issues and appropriate responses. In the case of migration and border security, there is a clear control-driven agenda that emanates from the EU Commission and member states that derives from the perception of SEE as the EU's ‘soft underbelly’ exposed to flows of irregular migrants (). This issue ‘framing’ then structures a specific ‘capacity bargain’ linking ministers and officials in each of the three case countries to the transgovernmental networks that have developed on migration in the European Union and in SEE.

Figure 1. Annual detections at the Greek–Turkish border and En Route from Greece to other EU member states. Source: Western Balkans Annual Risk Analysis Citation2012, 18.

For EU membership to be secured, it is essential that aspiring member states demonstrate the capacity to regulate access to their territory, that is, they need to demonstrate their capacity to act as a sovereign state prior to ceding aspects of this authority to the EU. An immediate puzzle is why EU policy has now extended into areas of migration and border security that are ‘high politics’ in that they closely relate to state sovereignty. Keohane, Macedo, and Moravcsik (Citation2009) advance a liberal institutionalist account of inter-state co-operation to argue that co-operation can enhance the quality of national democratic processes by weakening special interests and factions, offering scope for the protection of individual rights, improving the quality of democratic deliberation and, most importantly in the context of the analysis contained within this article, increasing a state's capacity to attain policy objectives. But why would states cede autonomy in an area that is so closely linked to their sovereign authority? Writing in the 1960s, Hoffmann (Citation1966) argued that European integration would be likely to founder in the face of integration's movement into areas of high politics that are closely linked to state sovereignty. In similar vein, Keohane, Macedo, and Moravcsik (Citation2009) argue that multilateral co-operation is unlikely on issues such as immigration because it is an issue of ‘high politics’ with the potential for high levels of domestic political conflict (analogous to issues such as welfare and taxation). Notwithstanding, we do see a common migration and asylum policy at the EU level that may not provide a full and comprehensive framework for EU migration, but which is a significant challenge to the view that European integration would not extend to issues of high politics. This theoretical puzzle points to limits of liberal institutionalist accounts and the advantages of a focus on transgovernmental networks that create scope for social and communicative logics of institutional behaviour to supplement the narrower focus on rational, instrumental logics.

Transgovernmental networks create scope for regularised interaction by a range of actors, including, for instance, national officials, but also other actors such as international and supranational organisations, academics, private sector organisations, think tanks and NGOs. These interactions centre on the sharing and exchange of practice, which can be understood as socially recognised competence (Adler and Pouliot Citation2011; Bicchi Citation2011). Transgovernmental networks provide a setting for the social validation of competence enabled by the regularised interaction and exchange via the networks that are identified later in this article. It could be that these transgovernmental networks lack substance and merely change the strategic context within which interactions occur without really affecting the identities and preferences of actors. This would correspond with a ‘thin’, instrumental logic of institutional behaviour more in accordance with the rationalist precepts of liberal institutionalism. However, this article's analysis of the composition of networks suggest that they play a role in developing new forms of interaction that affect the interests and identities of participants and prompt institutional logics of appropriateness that are more social in content. The identification of the scope for social and communicative logics to supplement instrumental logics is developed by Börzel and Risse (Citation2012) in their assessment of the EU's transformative effects in which they suggest an important role in constituting the identities and preferences of actors arising are regular interactions with peers, as well communicative logics arising from encounters with differing approaches and the need to justify these to its various components.

These logics of institutional behaviour occur within a policy area in which there has been a ‘multi-levelling’ of policy and legal responses to international migration, but within which transgovernmental networks link our three case countries with neighbouring states, EU member states, EU institutions and agencies and with a range of international organisations. It is this setting that provides the context within which ideas and action develop in the area of migration and border security. In turn, this relates to the point made earlier about control of the policy agenda within these networks. Our SNA and interview data demonstrate that while the EU may not always be strongly present as a network actor, it is strongly present as the frame of reference for policy development and interaction. For example, the European Commission is responsible for the management of policy and oversight of its implementation. The EU's ideas are the dominant ideas governing migration and border security in SEE. While the focus of policy remains very much centred on interior ministries in each case country, there is also extensive involvement by, and with, sub-national, national, sub-regional, regional and international organisations and agencies. For example, the sub-regional setting in SEE is evident though the MARRI (Migration, Asylum and Refugees Regional Initiative) project on migration, asylum and refugees that brings together six SEE countries (Albania, Bosnia–Herzegovina, Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia) that were during the period of this analysis (2008–2010) non-EU member states, and which sought to facilitate co-operation on issues closely related to the EU migration and border security acquis and the development of associated capacity.

Multi-levelling is also apparent through the pursuit of ‘Integrated Border Management’ (IBM). IBM is centred on the promotion of multi-level governance in the pursuit of reinforced domestic capacity. The intention is that this will arise from: intra-service co-operation within organisations and agencies; intra-agency co-operation between different ministries and agencies involved in this field; and international co-operation with agencies and ministries of other states and with international organisations. Other EU member states can shape policy in prospective member states through ‘twinning’ exercises, while international organisations such as the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) and the International Centre for Migration Policy Development (ICMPD) provide migration management services. Even within a relatively small country such as Macedonia, IBM poses significant challenges. As one interviewee noted:

One of the main problems is how to improve the level of co-ordination and co-operation between domestic institutions especially in IBM where you have a variety of institutions, agencies which is quite vast and covers about 6–7 ministries and a dozen of agencies [sic] which all have to be integrated into the system. (Interview, September 2008)

Migration and border security in SEE

Yugoslavia's collapse and the EU enlargements of 2004 and 2007 were seen to create a ‘territorial hole’ through which ran what was called a ‘Western Balkan’ migration route (Marenin Citation2010, 13) that was, according to the EU border agency Frontex: ‘largely a function of the transiting flow of migrants that enter the EU at the Greek-Turkish borders and later continue towards other Member States’ (Frontex Citation2012, 20). This route has also been closely associated with the so-called Pan-European Transport Corridor X (Salzburg-Thessaloniki) that crosses Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Macedonia and Greece.

Frontex identified three migration flows affecting the case countries that were particularly relevant to the time period for our study (2008–2010): first and largest was ‘circular’ migration of Albanians into Greece; second, migrants from south Asia, the Middle East and Africa; third, Turkish nationals entering Greece with the intention of onwards movement in the EU. This second flow was seen to represent ‘an increasingly growing threat to the integrity of the borders in the Western Balkan region and internal security/migration policies in the EU’ (Frontex Citation2010, 18). Frontex also reported that migrants transiting through Greece preferred the fastest route into Schengen, meaning Slovenia (Croatia did not immediately become part of Schengen on accession in 2013). The Western Balkan/Corridor X route was, therefore, identified as a key issue for the EU with important framing effects on migration and border security in each of the three case countries. The resultant policy setting is complex, involving at least five states and embracing border management, asylum and return policies. The migration routes themselves were seen as attractive to migrants because they were accessible and relatively low cost while ‘transit’ required ‘simple’ smuggling services with a low probability of being caught and opportunities for multiple attempts. This all points to the centrality of national and cross-border capacity and coordination but:

as long as illegal entry to the EU in Greece is perceived as relatively easy … new migrants will continue to arrive from Turkey. A substantial proportion is likely to use the Western Balkan land route should the mitigation measures there remain unchanged. (Frontex Citation2012, 39)

Frontex has no executive powers but plays a key role in promoting interoperability, involving permanent co-operation on technology, doctrine, organisational cultures, trust-building and the specification of standards. Frontex led the development of a Western Balkans Risk Analysis Network to provide technical training on data exchange to ‘risk analysis units'. It also established Rapid Border Intervention Teams (RABIT). Interventions that seek to reinforce border security can have unintended effects. Schengen visa standards, for example, mean that people who could once cross freely from non-EU states require visas and face the prospect of being:

driven back into an inner ghetto space. This applies of course only to law-abiding citizens, since criminals can walk or bribe their way across these frontiers with little difficulty. The introduction of visa requirements is a stimulus for corruption and criminality, since the borders are unenforceable, and the attempts to install them create incentives for illegal activity, including the trafficking of goods and people. (Marenin Citation2010, 37)

Slovenia

Slovenia's geographical location and external border with Croatia made it a terminus of the Western Balkan route and central to the EU's IBM policy and thus to the transgovernmental migration governance networks. From the 1950s, there was emigration from Slovenia by ‘guest workers’, particularly to Austria and Germany, and movement within the Yugoslav federation. From the mid-1970s Bosnians, Croats and Serbs moved to Slovenia leading to a ‘turbulent period in the history of migration to Slovenia, above all because of the break-up of the former Yugoslavia’ (Thomson Citation2006, 2). Independence in 1991 deprived tens of thousands of migrants from other Yugoslav Republics of their legal status in Slovenia. The Slovenia–Croatia border was the focus for Frontex Operations KRAS and DRIVE-IN in 2007 in response to irregular migration. Slovenia was the location of the first RABIT exercise in 2008 whose scenario was a sudden massive influx of illegal immigrants using the Western Balkan route. Border guards from 20 EU states participated in an exercise to test the reinforcement of a Member State's response capacity (House of Lords Citation2008; Vaughan-Williams Citation2008; Neal Citation2009). By 2011, Frontex was reporting a 108% increase in the number of Slovenian nationals facilitating illegal border crossing and there has been a tendency for migrants to shift from Hungary to Slovenia (Frontex Citation2011, 15). Engagement with FRONTEX enabled Slovenia to participate in a regional political setting, engage with non-EU neighbours and work with international organisations. This sub-regional dimension to the governance of border security and migration within SEE was important in all our cases and was framed by EU influences, national concerns and the interests of international organisations in developing policy and capacity.

Slovenia made a rapid adaptation to the requirements of EU membership and to the Europeanised frame for the governance of migration and border security. Between 1992 and 1998, large numbers of refugees moved to Slovenia from Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Employment and Work of Aliens Act (1992) responded to the labour market consequences of independence and the presence of large numbers of (now) ex-Yugoslavs by allowing long-term (at least 10 years) resident foreign nationals to acquire a work permit. In 2000, legislation was amended in line with EU legislation to create three types of work permit: for long-term residents; for employers to bring in workers; and for temporary migrant workers. Between 1999 and 2004, there were relatively high levels of irregular migration and in the third period (after May 2004) policy was framed by the EU and reflected core EU priorities, particularly the focus on border security and the ‘external’ dimension of the EU's ‘fight against illegal immigration’ (Adams and Devillard Citation2009, 418). The legislative framework during our fieldwork was the Aliens Act (2006) and two resolutions on immigration policy passed by the National Assembly, Resolution 40/1999 and 106/2002 regulated the entry of foreigners and the return of emigrants. The EU was concerned primarily with the Slovenia–Croatia border as an entry point into the EU.

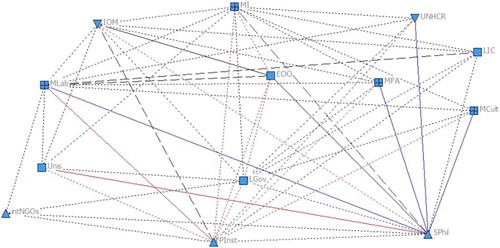

After Slovenia joined the EU in May 2004 its immigration legislation developed in accordance with the EU acquis and Slovenia managed a swift and relatively trouble-free adaptation (Adam and Devillard Citation2008, 425). The peak period for direct EU influence was between 1998 when negotiations began) and Slovenia's accession in 2004 after which Slovenia's roles as a policy taker widened into being a policy-maker with movement from institutional creation to institutional evolution. Our SNA analysis () found direct EU influence on Slovenian policy was nonetheless limited in the sense of visible participation of EU institutions within the policy network. What is noticeable about Slovenia's network is the important role played by NGOs and INGOs and the interior ministry's myriad connections within the network, which suggests a decline in EU influence after accession over time. We would, however, distinguish between direct influence and a profound impact on framing and the setting within which policy-makers operate.

Figure 2. The migration and border security network: Slovenia. MI, Ministry of Interior; MCult, Ministry of Culture; MLab, Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Affairs; MFA, Ministry of Foreign Affairs; LGov, Municipalities; UNHCR; IOM; IntNGOs, International NGOs; SPhil, Slovene Philanthropy; PInst, Peace Institute; Unis, Universities and research institutions; LIC, Legal Informative Centre; EOO, Equal Opportunity Office.

The Ministry of the Interior was, unsurprisingly, the key actor within the network with an extensive range of relations throughout the network. At the time of our research, the Ministry of the Interior had three counsellors based in Brussels and was a participant in the EU's Strategic Committee on Immigration Frontiers and Asylum (SCIFA) and its working groups. As migration increased in scale, attention shifted to labour migration, an area where the EU has no direct involvement, which drew other ministries, particularly the Ministry of Labour, into the network. A quota system for labour migrants was instituted in 2004 to protect the domestic labour market after access but was little used. The inevitable conclusion, ‘Slovenia is not at as attractive for economic migrants’ (Interview, Ministry of Labour, June 2008) shifted the focus to border security. The Ministry of the Interior focused on security but there was a more rights-based approach in the Ministry of Labour, Family and Social Affairs (MLFSA).

Slovenia slotted quickly into the EU frame for migration management. This, however, attracted some criticisms from civil society organisations. Despite rapid adaptation to a common policy, that policy can be ‘used’ by different ministries for different purposes. A Slovenian NGO official explained: ‘EU policy is welcomed by the Ministry of the Interior … EU policy has measures regarding integration … but in practice more effort is put into restrictive provisions such as border controls’ (Interview, June 21, 2008). A second interviewee argued ‘EU policy is used as an excuse not to think about migration—for copying EU directives into Slovene legislation without thinking about what adopted legislation would really bring’ (Interview, Slovenian NGO, June 2008).

NGOs were often critical of the direction of policy after accession as policy shifted to border security. Enhanced border security can, but not necessarily does, reduce a state's commitment to international, including, EU standards. A common theme in NGO interviews was that policy-making had regressed into an uncritical adoption of EU policy and a watering down of protection standards (see also Toplak Citation2006). There was little contestation of EU policy at the elite level. The EU was seen as ‘the only game in town’ and membership was/is a key priority for each case country. As in all cases, however, the capacity bargain applied to the formal dimension of policy in terms, for example, of legislative adaptation. Geddes and Taylor (Citation2013) argue that the capacity bargain focuses on the regulation of territorial access, which poses a series of regulatory-type dilemmas, but has less to say about the issues that arise once migrants are on a state's territory, which relate to questions such as labour market access and social rights, both of which raise complex distributive issues with domestic political consequences.

Croatia

Croatia has the longest external border in the EU: 1377 km compared to Greece's 1248 km. Border issues were, therefore, of huge significance in the accession process. The Chapter 24 Screening Report in 2006 found a ‘substantial amount’ of work was required if border management and enforcement capacity was to be improved; on migration (‘limited degree in [sic] compliance’) legislation required ‘comprehensive’ amendment; asylum rights were guaranteed but ‘substantial improvements’ were needed here and in visa policy. In all cases, major investments in capacity were required (CEC Citation2006a, 14–15).

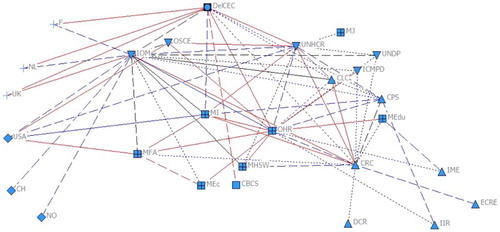

Croatia's external borders have been seen as posing a major challenge () with the USA on the fringes of the network and extensive engagement with EU members such as the UK, Netherlands and France. IBM was seen to require the ‘enhancing [of] inter-agency capacities, legislative alignment and institution building’ on a major scale. Accession and, ultimately, joining the Schengen area demanded demonstrating clear progress on ‘legislative alignment, institutional adaptation, upgrading of staff, effective enforcement and infrastructure investments’ over an extended period (CEC Citation2006b, 16–17). In 2009, the Croatian authorities, pointing to growing effectiveness, detected 57% of irregular border crossings at the Slovenia–Croatia border. Legislation such as the Aliens Act (2011) and implementation of the asylum acquis depended on improved capacities, both inter-agency and cross-border. The 2011 IBM plan was delayed by procurement and technical problems but cooperation with Frontex, twinning, and close cooperation with neighbours pointed to continued alignment with the EU and the evolution of the capacity bargain (CEC Citation2012, 8). This led to the dominance of the interior ministry. This was criticised by a foreign ministry official who argued this was ‘a big mistake because migration policy as they perceive it is a policy of repression’ (Interview, December 20, 2007).

Figure 3. The migration and border security network: Croatia. MI, Ministry of the Interior; MJ, Ministry of Justice; MHSW, Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; MFA, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration; MEdu, Ministry of Science, Education and Sports; MEc, Ministry of Economy, Labour and Entrepreneurship; CBCS, Cross-Border Co-operation Service; OHR, Office of Human Rights; IIR, Institute for International Relations, Zagreb; CLC, Croatian Legal Centre; IME, Institute for Migration and Ethnicity; CPS, Centre for Peace Studies; CRC, Croatian Red Cross; DelCEC, European Commission; OSCE, Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe; IOM, International Organization for Migration; UNHCR, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees; UNDP, United Nations Development Programme; ICMPD, International Centre for Migration Policy Development; ECRE, European Council for Refugees and Exiles; DCR, Dutch Council for Refugees.

In Croatia, we found a very strong focus on rapid adaptation to the EU acquis. Negotiations were opened on Chapter 24 on 24 October 2009. Changes were, therefore, a direct result of engagement with the EU. A senior Ministry of the Interior official believed the EU ‘has brought in changes that Croatia would have to bring in anyway [but] has quickened the adoption and enforcement of legislation’ (Interview, Ministry of the Interior, April 2008). The EU's primary effect was, then, to accelerate inevitable policy change. A second senior civil servant reiterated this: ‘The question is whether Croatia could regulate its society by itself. Of course it could, however this process is quickened and timeframes as well as goals are set that oblige us to act’ (Interview, Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration, April 16, 2008).

Institutional creation was dominated by EU requirements including IBM and the ‘fight against illegal immigration’ with measures to tackle people smuggling and human trafficking. The Act on the Amendments to the State Border Protection Act (December 2008) and the Act on the Amendments to the Aliens Act (March 2009) aligned Croatia with both the EU acquis and SBC. The political lead on accession negotiations was taken by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration and border and migration issues were key as they were understood an indicative of Croatia's ‘state-ness’ and capability (Interview, December 20, 2007). There was high-level co-ordination of the accession process with weekly meetings facilitating a rapid response to issues. Actors in day-to-day roles reported a strongly hierarchical administrative culture within the Croatian core executive that produced delay as issues filtered up to the senior level and then filtered back down.

shows engagement with the EU created scope for intervention by international organisations (such as UNHCR, IOM and ICMPD) offering technical knowledge and expertise. For example, from 2002 the UNHCR and IOM organised seminars on the role of border guards; developmental work included DCAF's work on the demilitarisation of borders and civilian control. The ICMPD drew on EU funding through its ‘AENEAS’ budget-line to develop a Memorandum of Understanding between countries in the region established statistical information exchange on illegal migration and the participation in a regional early warning system (November 2008). The EC delegation lacked the staff and expertise to undertake detailed technical policy work and training and focused on management and monitoring and encouraging cooperation between the Croatian government and international organisations. There was, however, an awareness of the limits of policy transfer and here the Commission delegation played an important role:

If there is some kind of resistance at the Ministry, or things are working slowly, then we come in. We nail them down. You are never going to be able to credibly argue that this chapter can be closed unless you have done this and these changes in, let's say, border law. (Interview, European Commission Delegation, April 2009)

International organisations deliver expertise but did not participate actively in policy-making. One reason for this was that laws (framed by the requirements of the EU acquis) needed to be developed rapidly. An IOM official reported that the 2008 legislation was developed very hurriedly and that the Parliamentary committee dealing with the legislation called on IOM for its views at one day's notice (Interview, IOM Official, April 2008). This also reflects some reluctance to draw from expert knowledge, which can be attributed in part to more critical or reflective elements that could slow adaptation to the EU. A Ministry of the Interior official argued that experts ‘have been included in the drafting of migration policy in the working group, but their input has not been as we expected. Very often they appear as criticisers, but not as those who recommend solutions’ (Interview, Ministry of the Interior, April 2008). Specialists believed their exclusion was due to the emphasis on rapid adaptation: ‘policy-makers do not gain knowledge from domestic sources … but they learn what they are forced to’ (Interview, Migration Research Institute, April 2008).

The core executive in Croatia appeared as relatively secretive and centralised. So, for example, the role of external advisers was limited ‘since Croatia received legal acts from Brussels that have to be implemented and those are usual technical issues … Experts know very little … ’ (Interview, Ministry of the Interior, April 16, 2008). Experts were judged by the interior ministry, to be obstacles to adaptation: ‘Very Often they appear as criticisers … not as those who recommend solutions’ (Interview, April 16, 2008).

The Commission, however, took a positive view on development of IBM believing Croatia ‘developed a pretty good integrated border management strategy and action plan on the basis of western Balkans guidelines’ (Interview, Commission Official, April 2008). The focus was securing Croatia's borders to demonstrate its capacity as a sovereign state and the image of a ‘good neighbour’.

Macedonia

Macedonia was at the time of this study (and still is) a country of emigration not immigration. In 2010, 29.1% of its tertiary educated population lived abroad (World Bank Citation2011). There was a very strong domestic awareness of the importance attached to border control by the EU, reinforced by Macedonia's geographical location that made it the ‘funnel’ of the Western Balkan route. Effective border control along EU lines was also seen as demonstrating Macedonia's legitimacy and effectiveness as a state. A failure to act, then, would undoubtedly damage seriously Macedonia's relations with the EU.

In 2011 and indicative of its incorporation within transgovernmental networks and within an Europeanised frame for migration management, Macedonia participated for the first time in Frontex operational activities. This involved participation in a permanent Frontex operation focused on the eastern and southern land borders of EU member states and the Neptune joint operation focused on land borders in the Western Balkans (Frontex Citation2011). As with the other cases, we found determined attempts to adapt to the EU framework for the governance of migration and border security driven by the pressures and demands of enlargement. Efforts were largely centred on the Interior Ministry with little evidence of elite-level contestation of the policy frame. EU priorities were thus ‘imported’ into the domestic context as part of the wider context of adaptation to the requirements of EU membership. Civil servants sometimes expressed puzzlement over the absence of definitive understandings of what was to be done. For example,

If you talk to a French police officer, from the French border police, he has one experience … While the German police officer will say something else, the Swedish one will say something completely different. I think that [this] can sometimes create a problem for us … It is not so easy when you will have to put all that together in one single frame. (Interview, Ministry of the Interior, March 10, 2008)

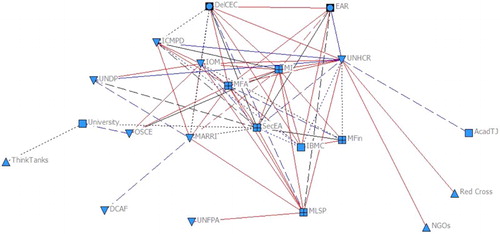

While the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration provided the negotiation lead with the EU the Ministry of the Interior was clearly the key actor in the migration and border security governance network (). An interior ministry official emphasised that ‘The role of the Ministry of the Interior as a main policy-maker of migration policy is uncontested’ (Interview, March 10, 2008); the Interior Ministry also coordinated the development of IBM. This is hardly a surprising finding and is in line with our findings in Slovenia and Croatia. The point that we seek to emphasise, however, is the re-constitution of authority that arose from the re-scaling of policy as a result of the capacity bargain that has been struck between the Macedonian state and the EU. This affects the content of policy and its domestic legitimacy, as well as the integration of Macedonian ministers and officials within transgovernmental networks. The ruling ideas within Macedonia about migration and border security are European ideas and were largely uncontested at the elite level. As an Interior Ministry interviewee puts it: ‘Every adjustment of our legislation is made in accordance with the EU acquis … . Here the EU influence is extraordinary … really huge’ (Interview, March 10, 2008). Again international organisations (e.g. the IOM, ICMPD and UNHCR) are present but, more than in the other cases, there is a ‘core network’ composed of the ministries of foreign affairs and interior, and the Secretariat for European Affairs. This helped to clarify the EU's role in the policy network. The key organisation was the Ministry of the Interior, but our interviews demonstrated the EU's centrality, particularly the Commission as the source of policy development. Enlargement and the perceived sensitivity of border control promoted network integration. Expertise was drawn from a wide range of organisations and provided clear evidence of the multi-level re-scaling of migration and border security. For example, between 2005 and 2007, financial support under the EU CARDS programme was made available to support IBM with involvement by the French Ministry of the Interior and involvement too from international organisations such as IOM and ICMPD (Taylor, Geddes, and Lees Citation2012, 158). The effect was to place considerable stress on domestic actors. Issues of capacity and capability placed limits on policy transfer:

We cannot copy-paste something, which was successful in Germany in our country and think that it is successful. We can write hundreds of laws, but what matters most is how we implement them. Macedonia still has certain specifics which must be respected and I think that we are aware that we have taken into consideration these specifics and implement them in our everyday work, as well as in laws we adopt. (Interview, Ministry of the Interior, March 10, 2008)

Figure 4. The migration and border security network: Macedonia. MI, Ministry of the Interior; MFA, Ministry of Foreign Affairs; MLSP, Ministry of Labour and Social Policy; University, University of Skopje; IOM; UNHCR; DelCEC, Commission Delegation; MARRI, Migration, Asylum and Refugees Regional Initiative; SecEA, Secretariat for European Affairs; EAR, European Agency for Reconstruction; MFin, Ministry of Finance; ICMPD; DCAF, Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF); UNDP; IBMC, CARDS Border police project/Integrated Border Management Commission; Red Cross, Macedonian Red Cross; UNFPA; OSCE, Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe; ThinkTanks, Think Tank Network; NGOs.

It could be asked whether the changes to national legislation would have occurred anyway. The answer to this question is that they may well have done so but the timing and rapidity of change the product of the EU as the driver of policy development.

Conclusion

This article analysed adaptation in the area of migration and border security in three SEE countries with varying relationships with the EU. The relational content of transgovernmental networks in the three case countries show how governed interdependence changes and reconstitutes state authority and relations between states, but also strengthens key domestic actors. SNA demonstrates the composition of transgovernmental networks that constitute an arena for social learning in conditions of governed interdependence. Learning had a strong compulsory component but central state actors in all three countries were willing pupils and the timing and tempo of policy change could not be accounted for without factoring-in the EU's role.

That European integration empowers central state actors is not in itself a new finding. There is an established body of work that shows co-operation at the EU level strengthens national executives. However, what we have sought to do through carefully grounded empirical analysis is extend the scope of these analyses, by specifying the relational and interactional content of networks, moving beyond the state intergovernmental versus supranational dichotomy and, develop fresh insights using case countries that have tended to be marginal to the study of migration but that are central to the EU's approach to migration and border security. Our focus on the relational aspects of policy change and state capacity and the ways in which domestic law and policy have been reconstituted and rescaled shows that, while none of our cases is a major immigrant destination country, all were framed as a potential route for irregular migrants to enter the EU with attendant efforts to enhance capacity to control territorial access. Each of the countries accepted and participated with this because of the broader benefits of EU membership.

The analysis also shows the extent of control within policy networks derived from the influence of the EU frame on new and prospective member states and the framing's impact is reflected in (broadly) similar domestic policy networks. These are structured to achieve common (EU mandated) ends but the domestic networks also engage extensively with international organisations and other EU countries. To seek to capture this in terms of whether they reflect an intergovernmental or a supranational dynamic is missing the point. Rather, they exemplify the development of transgovernmental forms of governance of migration and border security that are multi-level and, while strongly focused on states, have a broad range of participants; they change in fundamental ways the strategic context and social basis for the making and implementing of migration policy in Europe.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. The network diagrams were created using UCINET/Netdraw (http://www.analytictech.com/ucinet) and we gratefully acknowledge the help and assistance of Dr Daniel Wunderlich in preparing the diagrams. The analyses and the errors are, of course, entirely our own. The nature and type of relationships is shown by the style of the line connecting different actors. The ties are represented thus:

The following symbols represent the nodes:

References

- Adam, C., and A. Devillard. 2008. Comparative Study of the Laws in the 27 EU Member States for Legal Migration. Brussels: European Parliament Directorate General Internal Policies of the Union, Policy Department C: Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs.

- Adam, C., and A. Devillard. 2009. Comparative Study of the Laws in the 27 EU Member States for Legal Migration. Brussels: European Parliament.

- Adler, E., and V. Pouliot. 2011. “International Practices.” International Theory 3 (1): 1–36. doi: 10.1017/S175297191000031X

- Barnett, M., and R. Duvall. 2005. “Power in International Politics.” International Organization 59 (1): 39–75. doi: 10.1017/S0020818305050010

- Bevir, M., and R. Rhodes. 2003. Governance Stories. London: Routledge.

- Bicchi, F. 2011. “The EU as a Community of Practice: Foreign Policy Communications in the COREU Network.” Journal of European Public Policy 18 (8): 1115–1132. doi: 10.1080/13501763.2011.615200

- Börzel, T., and T. Risse. 2012. “From Europeanisation to Diffusion: Introduction.” West European Politics 35 (1): 1–19. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2012.631310

- Boswell, C., and A. Geddes. 2011. Migration and Mobility in the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- CEC. 2006a. The Global Approach to Migration One Year On: Towards a Comprehensive European Migration Policy. Brussels: COM (2006) 735 final.

- CEC. 2006b. Screening Report, Croatia, Chapter 24—Justice, Freedom and Security. Brussels: DG Enlargement. http://ec.europa.eu/enlargement/pdf/croatia/screening_reports/screening_report_24_hr_internet_en.pdf.

- CEC. 2012. “Monitoring Report on Croatia's Accession Preparations.” Brussels. Accessed April 24. http://ec.europa.eu/commission_2010-2014/fule/docs/news/20120424_report_final.pdf.

- Eurostat. 2009. Population Statistics. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/population-demography-migration-projections/population-data.

- Frontex. 2010. General Report 2010. Warsaw: Frontex.

- Frontex. 2011. General Report 2011. Warsaw: Frontex.

- Frontex. 2012. Western Balkans Annual Risk Analysis 2012. Warsaw: FRONTEX Risk Analysis Unit.

- Geddes, A. 2008. Immigration and European Integration: Beyond Fortress Europe? 2nd ed. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Geddes, A., and A. Taylor. 2013. “How EU Capacity Bargains Strengthen States: Migration and Border Security in South-East Europe.” West European Politics 36 (1): 51–70.

- Hafner-Burton, E., M. Kahler, and A. Montgomery. 2009. “Network Analysis for International Relations.” International Organization 63 (3): 559–592. doi: 10.1017/S0020818309090195

- Heisler, M. 1992. “Migration, International Relations and the New Europe: Theoretical Perspectives from Institutional Political Sociology.” International Migration Review 26 (2): 596–622. doi: 10.2307/2547073

- Hoffmann, S. 1966. “Obstinate or Obsolete: The Fate of the Nation State and the Case of Western Europe.” Daedalus 95 (3): 862–915.

- House of Lords. 2008. FRONTEX: The EU External Borders Agency. London: European Union Committee, 9th report of Session 2007–8, HL Paper 60.

- Keohane, R., and J. Nye. 1977. Power and Interdependence: World Politics in Transition. Boston, MA: Little Brown.

- Keohane, R., S. Macedo, and A. Moravcsik. 2009. “Democracy-Enhancing Multilateralism.” International Organization 63 (1): 1–31. doi: 10.1017/S0020818309090018

- Lavenex, S. 2006. “Shifting Up and Shifting Out: The Foreign Policy of European Immigration Control.” West European Politics 29 (2): 329–350. doi: 10.1080/01402380500512684

- Marenin, O. 2010. Challenges for Integrated Border Management in the European Union. Geneva: Geneva Centre for the Democratic Control of Armed Forces (DCAF).

- Neal, A. 2009. “Securitization and Risk at the EU Border: The Origins of FRONTEX.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 47 (2): 333–356.

- Pierre, J., ed. 2000. Debating Governance: Authority, Steering and Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rosenau, J. 1997. Along the Domestic Foreign Frontier: Exploring Governance in a Turbulent World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Slaughter, A.-M. 2009. A New World Order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Taylor, A., A. Geddes, and C. Lees. 2012. The European Union and South East Europe: The Dynamics of Multi-Level Governance and Europeanisation. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, A., A. Geddes, and C. Lees. 2013. Political Change in South East Europe: The Dynamics of Europeanisation and Multi-Level Governance. London: Routledge.

- Thomson, M. 2006. Migrants on the Edge of Europe: Perspectives from Malta, Cyprus and Slovenia. Brighton: Sussex Centre for Migration Research Working Paper 35.

- Toplak, J. 2006. “The Parliamentary Election in Slovenia, October 2004.” Electoral Studies 25 (4): 825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2005.12.006

- Trauner, F. 2011. The Europeanisation of the Western Balkans. EU Justice and Home Affairs in Croatia and Macedonia. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Vaughan-Williams, N. 2008. “Borderwork beyond Inside/Outside? Frontex, the Citizen–Detective and the War on Terror.” Space and Polity 12 (1): 63–79. doi: 10.1080/13562570801969457

- Weiss, L. 1998. The Myth of the Powerless State. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- World Bank. 2011. Factbook on Migration and Remittances. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Zolberg, A. 1989. “The Next Waves: Migration Theory for a Changing World.” International Migration Review 23 (3): 403–430. doi: 10.2307/2546422