ABSTRACT

Higher education is one of the social fields where inequalities are produced and reproduced. Nevertheless, we still know very little about the ways in which heterogeneities and inequalities have been experienced and interpreted by those involved in international academic mobility. In this introductory editorial, we consider some of the crucial conceptual issues involved in the study of the nexus between inequalities and international academic mobility. First, we argue that it is important to take manifold inequalities into account when examining this nexus. After all, inequalities can be detected at different levels, and the mobility process is structured around multiple heterogeneities rather than by a single one. Second, we discuss how international academic mobility and inequalities attached to it go beyond nation-state borders. Third, we argue it is beneficial to extend the scope of to the mobility process as a whole, as inequalities in opportunities and outcomes are intrinsically connected.

Introduction

Within the context of transnationalising labour markets and social life worlds, higher education represents a major field for understanding the ways in which social inequalities are produced and reproduced. In this special issue, we specifically focus on the role of academic mobility on the production and reproduction of inequalities, in line with recent scholarship which argued that international mobility within academia intensifies ‘social difference within the globalizing higher education system’ (Findlay et al. Citation2012, 119). Although international spatial mobility is often considered as a way to upward social mobility (e.g. Beck Citation2006), the central argument of this special issue is thus that international academic mobility also produces and reproduces inequalities. Mobile academics and students might, for example, find themselves in privileged positions in academia and/or in other sectors of labour markets during and/or after their mobility experience, or conversely, they might experience disadvantaged positions because of spending time abroad (cf. Guth and Gill Citation2008). Nevertheless, empirical evidence on the relationship between inequalities and international mobility of students and faculty members – which we refer to as international academic mobility in the remainder of this introduction – is rather limited. Usually these two groups are analysed separately (see Byram and Dervin Citation2008, for an exception). In this special issue we argue that albeit covering different life and career stages, both forms of knowledge mobility/migration are structured within the same field and together profoundly shape ‘the global geographies of knowledge production’ (Jöns Citation2015, 372). By analysing the international mobility of academics and students within a single journal issue, this special issue aims to advance our general understanding of the relationship between inequalities and knowledge mobility/migration, with a particular focus on the field of higher education. For migration scholars, the investigation of knowledge mobility/migration within academia is relevant, as the differences in decisions, experiences, trajectories, and outcomes reflect the multiple, fragmented, and complex nature of migration today.

From a resource perspective, individuals’ economic, social, and cultural capital determines their positions within social spaces. According to Bourdieu (Citation1984, Citation1986, Citation1993), those who already have an advantageous socio-economic background are likely to continue to hold these positions in their later life as they dispose of the necessary capital to enter to the field of higher education, and keep their differentiation, thus their higher status from the rest of the society. The stratification experienced in higher education is also reflected in the labour market positions of individuals reproducing differential power structures, unequal resource distribution, and therefore life chances (Weber Citation1968). Against this background, we understand social inequalities as referring not only to different distribution of valuable goods and resources, but also to the lack of opportunities in access to certain fields such as higher education which would not yield acquisition and/or maintenance of status and power (Grusky Citation2011; Ohnmacht, Maksim, and Bergman Citation2009; Platt Citation2011; Tilly Citation1999). Inequalities tied to both access and outcome in the higher education field are evident along gender lines, class, and ethnicity (Halsey et al. Citation1997; Pfaff-Czarnecka Citation2017). Interestingly, inequalities might not only exist between but also within societal ‘groups’. Even individuals who supposedly possess valuable resources and have access to spatial mobility can experience different forms of inequalities. This special issue precisely focuses on such experiences, namely those of internationally mobile academics and students.

Although international mobility is certainly not a new phenomenon within academia (cf. Ehrenberg Citation1973), it has been increasingly attributed as a fundamental element of academic habitus (Bauder Citation2015; Li and Bray Citation2006). Mobility is often an expected practice to be successful, and even became a requirement to secure better employment positions in certain skill-based labour market niches within neoliberal economies (Morano-Foadi Citation2005; Rothwell Citation2002; Waters Citation2009a, Citation2009b). As a result, the terrain of academia has been reshaped not only by student and faculty exchanges, but also through exchanges of knowledge and practices as well as repositioning of the higher education institutions. It is hence not surprising that over the last two decades, a myriad of studies have been published on the determinants (e.g. Beine, Noël, and Ragot Citation2014; Findlay Citation2011; Maringe and Carter Citation2007; Van Mol Citation2014; Wei Citation2013), experiences (e.g. Bilecen Citation2014; Brooks and Waters Citation2011; King et al. Citation2011; Montgomery Citation2010; Murphy-Lejeune Citation2002), knowledge practices (e.g. Bilecen and Faist Citation2015; Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo Citation2015; Raghuram Citation2013) as well as outcomes of international academic mobility (e.g. Robertson Citation2011; Shen and Herr Citation2004; Welch Citation1997). These contributions originate from a myriad of disciplines, such as Anthropology, Economics, Educational Studies, Geography, and Sociology. Consequently, this special issue also adopts an interdisciplinary approach, bringing together contributions from different academic disciplines.

Despite the increased attention of migration scholars on international academic mobility, however, our current scientific knowledge of how different inequalities intersect with such mobility remains rather limited. The current special issue aims to fill this gap, bringing together a collection of recent empirical studies that focus on the dynamics of international academic mobility and inequalities within and across nation-state borders. All the authors critically reflect on the meaning and implications of international mobility for educational purposes and their relation to a variety of inequalities, at the macro, meso, and micro-level. The articles in this issue vary in the type of populations and the countries of education and origin on which they focus – albeit the main focus is on the European context – as well as in terms of methods and methodologies. This diversity of approaches and contexts is highly informative for grasping how international academic mobility relates to inequalities.

In our introductory remarks to this special issue we consider some of the crucial conceptual issues that cater the main framework for the articles in this issue. We start our discussion by considering the nexus between inequalities and international academic mobility. Subsequently, we present our ideas on investigating social inequalities within the context of international academic mobility with a transnational lens. After giving an overview of the contributions of the current issue, in conclusion, we reflect on the implications to study inequalities in a mobile and transnational environment.

International academic mobility and inequalities

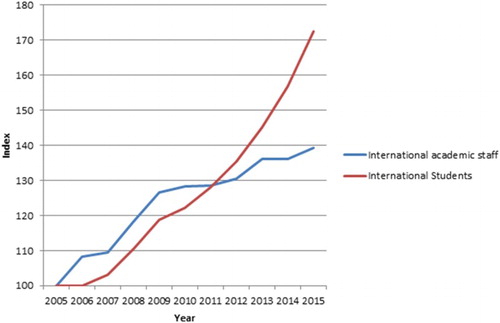

International academic mobility significantly increased over the past decade. According to the Institute of International Education (Citation2016), the mobility of scholars increased worldwide from 89,634 in 2005 to 124,861 in 2015. The numbers of international students are even more impressive, increasing from 565,039 in 2005 to 974,926 in 2015. When we consider the relative growth of international student mobility to the international mobility of faculty, taking 2005 as a starting point (see ), it can be noticed that the former is growing faster: international student mobility increased with two thirds, compared to one third for the international mobility of faculty members.

Figure 1. Relative growth in global academic mobility, 2005–2015.

In general, international academic mobility is directed towards the countries in the Global North, thereby intensifying existing global inequalities. As Börjesson shows in this volume, for example, international students mainly head towards a selected group of countries in the Global North: more than half of all international students move to the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, France, and Germany. A similar pattern can be found among doctoral students as well (Van der Wende Citation2015). Although educational activities such as international exchange programs are also on the rise within the South–South regions, ‘[i]nitiatives and programs, coming largely from the north, are focused on the south. Northern institutions and corporations own most knowledge, knowledge products, and IT infrastructure’ (Altbach and Knight Citation2007, 291).

We argue that inequalities in relation to international academic mobility should be examined from both inequality debates on opportunities as well as outcomes, as they are fundamentally connected. On the one hand, the equality of opportunity perspective assumes that ‘a person’s chances to get ahead (attain an education, get a good job) should be unrelated to ascribed characteristics such as race, sex, or class (or socioeconomic) origin’ (Breen and Jonsson Citation2005, 223). Studies with this perspective explore the cumulative series of actions that led to unequal positions (Platt Citation2011). Higher education is a field where access is often restricted mainly based on socio-economic background (Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1977; Shavit and Blossfeld Citation1993). Although the numbers of higher education institutions and enrolments from a variety of class backgrounds increased in recent decades, potentially enhancing their opportunities for education and labour market chances, the already privileged are disproportionately favoured (Shavit, Arum, and Gamoran Citation2007). With an increased pool of tertiary educated graduates, the value of such degrees for attaining jobs decreases (García Ruiz Citation2011). Today, it is not just having a tertiary degree which matters, but the place where this degree was obtained plays an important role in enhancing and/or securing chances in the labour market. As the place where degrees are obtained and whether and how they are recognised in different places is becoming increasingly important, academic mobility is potentially a key source in the production and reproduction of inequalities. Nevertheless, international academic mobility is not equally easy to realise for all individuals as it can involve significant financial and personal costs (e.g. Ackers Citation2008; Scheibelhofer Citation2006; Van Mol Citation2014). In this special issue, several papers therefore investigate access to international mobility in terms of, for example, different experiences of men, women, couples (Schaer, Dahinden, and Toader Citation2017; Sondhi and King Citation2017), ethnicity, and class positions (Shinozaki Citation2017; Wilken and Ginnerskov Dahlberg Citation2017).

On the other hand, studies looking into inequalities of outcome investigate disadvantages and disparities in societies as a result of heterogeneities mainly focusing on gender, ethnicity, and class. Inequalities of outcome in international academic mobility pinpoint to the ways in which such mobility yields to advantageous or disadvantageous positions. Therefore, the inequalities faced by those involved in international academic mobility are the main topic of the papers in the current issue. By moving abroad, students and faculty members are expected to be exposed to different ‘academic cultures’ with different empirical, methodological, and theoretical approaches. This way, academics and students moving across international borders would acquire important symbolic capital or ‘reputational capital’ (Ackers Citation2008) in terms of – for example – prestige, credibility, and specific skills that would be valued by employers. International mobility is hence considered to be leverage for advancing (academic and non-academic) careers in a competitive labour market both in the countries of education (Zeng and Xie Citation2004) and origin (Mohajeri Norris and Gillespie Citation2009). In academic and policy discourses, international academic mobility is considered inherently beneficial for mobile individuals, higher education institutions, and the labour markets through – for example – exchanges of knowledge and know-how (Bilecen and Faist Citation2015; Jöns Citation2009; King and Raghuram Citation2013; Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo Citation2015), fostering intercultural understanding (Jackson Citation2010; Williams Citation2005), and tolerance (Bilecen Citation2013) together with the development/improvement of language skills (Magnan and Back Citation2007; Pellegrino Aveni Citation2005).

Although those who engage in international academic mobility might experience their investment as a way of differentiation, associated with better educational and labour market perspectives compared to their non-mobile counterparts, this might not necessarily always the case (cf. Brooks, Waters, and Pimlott-Wilson Citation2012; Netz Citation2012; Van Mol Citation2017). Even when a stay abroad is transferred and fully recognised in other countries, employers and colleagues might not always be aware of the value of foreign degrees and experiences, thus treating (formerly) mobile individuals as newcomers (Weiss Citation2005, Citation2016). Furthermore, by going abroad, students and faculty members might weaken their local social networks which can be vital for ensuring access to jobs and/or new positions. Moreover, employers might favour individuals who are familiar to how things are done over people who worked for some time abroad. In sum, besides inequalities in access to international mobility, mobility itself can create new inequalities or reinforce existing ones.

When considering debates on selectivity and outcomes, the focus is often on individuals’ socio-economic background (e.g. Lörz, Netz, and Quast Citation2016). In this special issue, we argue it is important to consider other heterogeneities that might result in unequal positions as well, thus extending the scope of analysis. It has been documented, for example, that gender plays a significant role in shaping international academic mobility patterns (see e.g. Bauder Citation2015; Holloway, O’Hara, and Pimlott-Wilson Citation2012; Shinozaki Citation2017; Sondhi & King Citation2017). At the undergraduate and graduate student level, mobile female students are often overrepresented (Böttcher et al. Citation2016; Jöns Citation2011). Interestingly, when considering the mobility of academics, ranging from the pre-doctoral to senior faculty level, this pattern is inversed. According to the study of Jöns (Citation2011) with former visiting researchers in Germany, especially in the natural sciences female faculty members participate much less in international academic activities compared to their male counterparts. One of the explanatory factors of female academics’ low participation rates has been their roles as the main caregivers to their families (Jöns Citation2011; Scheibelhofer Citation2010), although care has also been acknowledged to restrain male academics’ international mobility patterns as well (Ackers Citation2008). Nevertheless, the gendered nature of academic mobility, and particularly international student mobility, has been rather neglected in academic research (King and Raghuram Citation2013; Salisbury, Paulsen, and Pascarella Citation2010). In this special issue, Shinozaki, Sondhi and King, and Schaer and colleagues take up this issue, exploring how gender roles impact the international trajectories of both students and academic staff.

In addition to gender, employment situations and the career stage also play an important role in shaping international mobility patterns and its outcomes. In general, it has been argued that the earlier in the career stage, the more important international academic mobility might be (Balter Citation1999; Hoffman Citation2007). Particularly for post-doctoral researchers, international mobility has become a requirement to distinguish themselves in a context characterised with increased competition for a limited number of jobs (Guth and Gill Citation2008). In that vein, the study of Barjak and Robinson (Citation2008) among doctoral students and post-doctoral researchers in the life sciences in ten European countries showed, for example, that while 20% of doctoral students received their education in a different country, among post-docs this number increases up to 40% in order to distinguish themselves and attain ‘better’ positions. Therefore, we argue that it is important to also analyse diverse set of heterogeneities leading to manifold inequalities international academic mobility might bring along.

Transnationalising inequalities tied to international academic mobility

While the higher education field is argued to be internationalised, globalised, and transnationalised (Gargano Citation2009; Knight Citation2004; Teichler Citation2009), inequalities emanating from these interconnected systems as well as the repercussions of such interconnectedness in terms of inequalities are still very much confined within the understanding of nation-states as natural containers of hierarchies, power, and status struggles. This is unfortunate, as in a world characterised by increased levels of flows of people, knowledge, and ideas, norms and experiences of inequalities can no longer be confined within one nation-state but rather should be interpreted transnationally (Amelina Citation2012; Faist Citation2016; Manderscheid Citation2009; Weiss Citation2005).

In the field of higher education, nation-states used to be the main authorities in certifying and standardising credentials with the aim that qualifications would serve within the given nation-state. Although the nation-states are still important actors in the higher education field, today we observe that other actors and processes are simultaneously involved. First, inequalities are on the rise stemming from the non-recognition of qualifications by the national educational as well as labour market systems. The academic literature on migration contains many examples of deskilling through international mobility, as well as degree mismatches in the national systems leading to power differentials between migrant and native populations (e.g. Nieswand Citation2011; Nowicka Citation2012; Weiss Citation2005, Citation2016). Previous studies indicated that movers often experience skill downgrading, ending up in relatively lower positions in the labour market in the destination country while they had relatively higher statuses in the countries of origin (Faist Citation2008; Shinozaki Citation2015). The existing empirical literature on international academic mobility suggests mixed results. Today, international mobility is increasingly valued on a CV, and hence movers are thought to have an advantage over stayers. A study of Mamisheisvili (Citation2010) showed, for example, that compared to their native counterparts, foreign-born female academics engage more in prestigious research activities, and spend less time for administrative and teaching activities. However, perils of moving abroad have also been observed (Richardson and Zikic Citation2007). For instance, according to Ackers (Citation2008), spending time abroad for advancing academic careers can have adverse outcomes upon researchers’ return as they might have lost necessary networks for getting academic positions, leaving them in an unequal situation compared to their native counterparts in the countries of origin (see also Lulle and Buzinska Citation2017). Moreover, Amelina (Citation2012) studying female scientists in the Ukrainian-German transnational social space observed that their mobility is not only restricted due to care commitments but also because of difficulties in getting recognition of their degrees. Interestingly, her study indicates recognition of credentials as a double-edged sword: besides difficulties in getting official recognition, in their social circles they also experience that German degrees are valued more than Ukrainian ones.

Second, there is an increase of transnational education institutions. Transnational education here refers to ‘any education delivered by an institution based in one country to students located in another’ (McBurnie and Ziguras Citation2007, 1), including branch campuses, franchising, off-shore degrees, virtual universities, and distance education (see Knight Citation2016 for an extensive review on transnational HEIs). The general tendency of Anglo-Saxon dominance in knowledge systems in higher education is also apparent in transnational education (Naidoo Citation2011) which turns into a symbolic regime of education. While transnational education (TNE) programmes aim to marketise and expand higher education across borders usually from a Global North perspective, issues regarding to the attached value to their credentials as well as experiences of students and academics are rather scarce (see Waters and Leung Citation2012 for an exception). For example, in this issue Leung and Waters investigate the meanings and practices of power geometries from the perspectives of the flying faculty members teaching in branch campuses in Hong Kong of British universities. The authors also argue that some students perceive local higher education degrees more reputable than the British ones offered in branch campuses (Leung and Waters Citation2017).

These two points direct our attention to the ways in which value is being assigned to resources, depending on the economic, social, political, as well as geographical contexts wherein individuals are situated (Therborn Citation2001). We argue that it is essential to understand the processes through which values are being assigned by whom, and where, and under which conditions they lead to inequalities. When individuals cross nation-state borders, they need to transfer or make their cultural capital understandable to those who are not familiar with it. Even though educational qualifications as a form of institutionalised cultural capital has been officially recognised by the nation-states and to some degree by employers, they still need to be acknowledged by colleagues in the workplace (Weiss Citation2016). It has been argued that ‘[t]he value of the cultural capital possessed by overseas-educated graduates depends, crucially, on particular, embedded and localised social relations’ (Waters Citation2009b, 116, original emphasis). After all, not only individuals engaged in international mobility cross nation-state borders, but also some of their credentials and capital come to a new nation-state regime where everything is different. Thus, experiences and practices that come along with international mobility of students and staff need to be negotiated in their everyday lives. Therefore, research on higher education and social inequalities specifically focusing on international academic mobility needs to take into account the multiple social positions of individuals (both with and without such experiences) as well as institutions across a variety of places under regulation by different nation-state regimes.

Overview of the articles

All contributions in this special issue consider inequalities in international academic mobility in relation to heterogeneities such as different colonial relations and labour market logics at the macro-level, as well as gender, socio-economic background, and nationality/ethnicity at the micro-level. Furthermore, they also address how qualifications gained abroad might (re)produce inequalities in faculties, universities, and labour markets in both the countries of origin and destination.

The paper by Börjesson (Citation2017) investigates the global terrain of academic mobility, illustrating the hierarchical positions of nation-states from a macro-level perspective. Using correspondence analysis, he maps out the international patterns of flows against socio-spatial structures. His analysis reveals student mobility is asymmetrically distributed and subjected to different logics, namely of the market, proximity of nation-states, and colonial history. His paper pinpoints to a symbolic regime of education across the globe legitimising the dominance of the norms and practices of the ‘agenda-setting’ Global North. One of the main contributions of this study is its illustration of the ways in which international student mobility favours well-developed infrastructures, potentially magnifying inequalities among the nation-states (cf. Altbach and Knight Citation2007; Brooks and Waters Citation2011).

Leung and Waters (Citation2017) concentrate on the perspective and unequal experiences of transnational education providers, namely the flying academics in branch campuses of 16 British TNE programmes in Hong Kong. Their paper shows that although TNE programmes make international higher education available to students without the necessity of crossing national borders, such as in the case of Hong Kong, many borders between the providers and recipients of education remain. Moreover, the authors pinpoint to the power dynamics between partner institutions in the UK and Hong Kong, challenging the common assumption of ‘Western hegemony’ in TNE.

The remainder of the papers focuses on students’ and academics’ experiences of inequalities. Three papers explicitly focus on inequalities tied to gender. The paper of Schaer, Dahinden, and Toader (Citation2017) reveals the gendered negotiations and arrangements that are made when couples decide to relocate together when pursuing the academic career of one of the partners. Based on three case studies of early career researchers located in Europe and North America, they show the variability in trajectories that occur in a situation of mobility. Importantly, their study nuances existing literature by revealing that international mobility also has the potential to reconfigure typical gender configurations.

The paper by Sondhi and King (Citation2017) analyses international student migration as a gendered process. The authors build on a case-study of Indian student migration, investigating their motivations to study abroad, negotiations of gendered everyday life, and processes of return to India. Based on a mixed-methods study taking both students’ and their parents’ perspectives into consideration, Sondhi and King illustrate the ways in which power is negotiated along gender lines within Indian families.

Shinozaki’s (Citation2017) paper adopts an intersectional perspective. She investigates the extent to which the intersection of gender and citizenship influences academic career prospects both in terms of advantages and disadvantages. The author’s analysis is based on a case-study of two higher education institutions in Germany, and illustrates three key career stages, namely doctoral researchers, post-doctoral researchers, and professors. Through a mixed-methods approach, Shinozaki argues that throughout all three career stages, the structure of intersecting gender-based and citizenship-based inequalities in academic career advancement is rather rigid. Nonetheless, in her analysis of non-German female academics she cautions not to equate female gender and non-German citizenship status with additive disadvantages in a straightforward way. She also demonstrates the differentiated ways in which German higher education institutions implement their respective internationalisation strategies, impacting on the profile of its academic staff.

The paper of Wilken and Ginnerskov Dahlberg (Citation2017) explores the intersection between international student mobility and low-skilled employment among master students from recent EU member states in Denmark. Focusing on the economic vulnerability that students from new member states often face, they reveal how these students often have to work in semi-legal and low-skilled jobs in order to sustain themselves while being abroad. Their analysis shows how these students make sense of their lives while having to navigate between the contradictory roles as students and workers in Denmark, as well as how these experiences influence their ideas of geopolitical belonging in Europe. Their paper exemplifies how social policies nation-states structure the terrain of higher education and thus stratification among various student bodies.

The last two papers in this special issue investigate the disadvantaged positions that might result through international academic mobility. The contribution of Lulle and Buzinska (Citation2017) explores the ways in which Latvian students abroad perceive their position in terms of access to education, inequalities in the symbolic value of higher education institutions’ prestige as well as inequalities in recognition of their cultural capital both in countries of education and origin. Interestingly, the authors reveal that one of the major drivers for Latvian students to study abroad is their experience of inequalities in access to higher education in their country of origin. Likewise, their return intentions are also influenced by these experiences. Their analysis shows that the lack of transparent structures in the labour market, the obstacles to recognition of foreign degrees as legitimate and valuable capital, together with a lack of relevant social connections to acknowledge their accumulated capital, refrain the interviewees to return to Latvia. This paper also illustrates the fluidity of international students as a migrant category (Bilecen Citation2014; King and Raghuram Citation2013): study is not always a primary motive for emigration, but migrants can shift status throughout their mobile trajectories.

Finally, the paper by Tzanakou and Behle (Citation2017) addresses the structural barriers in the transferability of degrees, focusing on the experiences of (European and British) UK graduates in British and European labour markets. They show that despite the positive outcomes generally associated with mobility in academic and policy discourses, mobile graduates often experience significant difficulties when aiming to work in another country. Their analysis shows that investments in foreign education can have adverse outcomes and even negatively impact labour market trajectories, particularly when the education-to-work transition is made in a different country than where students obtained their degree. Their contribution not only points to individual experiences of inequality, but also to the structural and spatial challenges in terms of recognition of qualifications shaping these inequalities.

Conclusion

In this special issue we address the multifaceted relationship between international academic mobility and inequalities. In this introduction, we argued that the study of this relationship should transcend the common questions of who goes where, and whether and how students and faculty members improve their skills and CVs through mobility, along with a consideration of transferability of skills and institutional credentials. Albeit these are important questions, they do not necessarily address multiple inequalities, both at the macro and micro levels. Access to and outcomes of international academic mobility are structured by disparities in the way labour markets, nation-state regulations, discourses, higher education systems, and institutions are organised as well as by individual characteristics such as gender, age, class, career stage, and cultural background. The collection of papers in this special issue delves deeper into some of these issues. Furthermore, we have also added to this debate ‘where’ to indicate the mobility and spatial dimensions of inequalities. Disparities in power, privilege, and advantageous positions are not only about differential access to valuable resources in one nation-state framework anymore, but rather practices of persons and institutional structures go beyond nation-state borders (see also Faist Citation2016). This situation along with spatial considerations in inequalities such as how values are being assigned by different actors in different locations pinpoint to a more nuanced understanding of inequalities tied to international academic mobility. Therefore, this special issue makes a number of important contributions to the existing literature on these dynamics.

First, this special issue shows that inequalities tied to international academic mobility are highly transnationalised. Nowadays, transnationalising higher education systems feed workforce to the transnationalising labour markets. Transferability of degrees as well as finding employment after an overseas academic stay has attracted the most attention when international academic mobility and social inequalities are considered. Moving across nation-state borders might entail challenges such as power negotiations, disruptions in career progress, along with considerations on unequal access across different student bodies and faculty members. Furthermore, whereas socio-economic background undoubtedly plays an important role in the decisions, experiences, and outcomes of mobility, we argued in this introduction that other heterogeneities should also be taken into account. Together, the papers in this special issue reveal the relevance of analysing academic mobility in reference to gender, citizenship, and career stage lines. Whereas these dimensions are only sparsely studied today, they should be considered to fully depict the complex relationships between inequalities and international academic mobility in transnational settings.

Second, this special issue shows that the spaces of education matters as well. Depending on the location of persons and institutions, differential values to experiences and credentials gained through international mobility are being assigned, which generates disparities in power and advantage. In other words, social positions of individuals are reconstructed through their mobilities and immobilities, both in their countries of origin and that of destination. In order to understand these processes to the fullest further research should concentrate on the mechanisms through which social inequalities are being produced and reproduced by taking into account of a variety of actors, nation-states, and higher education institutions.

Finally, two limitations of this special issue should be acknowledged. First, this special issue mainly concentrates on European and North American contexts, whereas other educational hubs and interesting dynamics are emerging around the world. Future research could investigate whether the inequality dynamics explained in this set of papers also apply in other contexts. Second, whereas some of the papers touch upon the topics of race, ethnicity, and socio-economic status, these were not central. Therefore, we encourage future studies on academic mobility to engage more fully with these key markers of heterogeneities and inequalities. Despite these limitations, however, this special issue provides fresh empirical evidence on how inequalities act as a driver and/or barrier to mobility and how mobility might generate and reinforce existing inequalities. Together, they shed light on the most recent theoretical developments and the most recent empirical results from both quantitative and qualitative empirical research.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Karolina Barglowski, Simone Castellani, Anatolie Cosciug, Thomas Faist, Tobias Gehring, Yaatsil Guevara Gonazales, Natalya Kashkovskaya, Cleovi Mosuela, Susanne Schultz, Joanna Sienkiewicz, Yasemin Soysal, Inka Stock, Christian Ulbricht, and the participants of the conference Transnational Academic Spaces for their useful comments, discussions, and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackers, Louise. 2008. “Internationalisation, Mobility and Metrics: A New Form of Indirect Discrimination?” Minerva 46 (4): 411–435. doi:10.1007/s11024-008-9110-2.

- Altbach, Philip G., and Jane Knight. 2007. “The Internationalization of Higher Education: Motivations and Realities.” Journal of Studies in International Education 11 (3/4): 290–305. doi: 10.1177/1028315307303542

- Amelina, Anna. 2012. “Hierarchies and Categorical Power in Cross-border Science: Analyzing Scientists’ Transnational Mobility between Ukraine and Germany.” COMCAD Working Papers No. 111. COMCAD: Bielefeld.

- Balter, Michael. 1999. “Europeans Who Do Postdocs Abroad Face Reentry Problems.” Science 285 (5433): 1524–1526. doi:10.1126/science.285.5433.1524.

- Barjak, Franz, and Simon Robinson. 2008. “International Collaboration, Mobility and Team Diversity in the Life Sciences: Impact on Research Performance.” Social Geography 3 (1): 23–36. doi: 10.5194/sg-3-23-2008

- Bauder, Harald. 2015. “The International Mobility of Academics: A Labour Market Perspective.” International Migration 53 (1): 83–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2012.00783.x

- Beck, Ulrich. 2006. Power in a Global Age: A New Global Political Economy. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Beine, Michel, Romain Noël, and Lionel Ragot. 2014. “Determinants of the International Mobility of Students.” Economics of Education Review 41: 40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.03.003

- Bilecen, Başak. 2013. “Negotiating Differences: Cosmopolitan Experiences of International Doctoral Students.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 43 (5): 667–688.

- Bilecen, Başak. 2014. International Student Mobility and Transnational Friendships. London: Palgrave.

- Bilecen, Başak, and Thomas Faist. 2015. “International Doctoral Students as Knowledge Brokers: Reciprocity, Trust and Solidarity in Transnational Networks.” Global Networks 15 (2): 217–235. doi: 10.1111/glob.12069

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1993. The Field of Cultural Production. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bourdieu, Pierre, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1977. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. Translated by R. Nice. London: Sage.

- Börjesson, Mikael. 2017. “The Global Space of International Students in 2010.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1256–1275. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300228.

- Böttcher, Lucas, Nuno A. M. Araújo, Jan Nagler, José F. F. Mendes, Dirk Helbing, and Hans J. Herrmann. 2016. “Gender Gap in the ERASMUS Mobility Program.” PLoS ONE 11 (2): e0149514. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0149514.

- Breen, Richard, and Jan O. Jonsson. 2005. “Inequality of Opportunity in Comparative Perspective: Recent Research on Educational Attainment and Social Mobility.” Annual Review of Sociology 31: 223–243. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.31.041304.122232

- Brooks, Rachel, and Johanna Waters. 2011. Student Mobilities, Migration and the Internationalization of Higher Education. London: Palgrave.

- Brooks, Rachel, Johanna Waters, and Helena Pimlott-Wilson. 2012. “International Education and the Employability of UK Students.” British Educational Research Journal 38: 281–298. doi: 10.1080/01411926.2010.544710

- Byram, Mike, and Fred Dervin. 2008. Students, Staff and Academic Mobility in Higher Education. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Ehrenberg, Victor. 1973. From Solon to Socrates: Greek History and Civilization during the Sixth and Fifth Centuries BC. London: Methuen.

- Faist, Thomas. 2008. “Migrants as Transnational Development Agents: An Inquiry into the Newest Round of the Migration-Development Nexus.” Population, Space and Place 14 (1): 21–42. doi: 10.1002/psp.471

- Faist, Thomas. 2016. “Cross-border Migration and Social Inequalities.” Annual Review of Sociology 42: 323–346. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074302.

- Findlay, Allan M. 2011. “An Assessment of Supply and Demand-side Theorizations of International Student Mobility.” International Migration 49 (2): 162–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00643.x

- Findlay, Allan M., Russell King, Fiona M. Smith, Alistair Geddes, and Ronald Skeldon. 2012. “World Class? An Investigation of Globalisation, Difference and International Student Mobility.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 37 (1): 118–131. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2011.00454.x

- García Ruiz, María José. 2011. “Impacto de la globalización en la universidad europea del siglo XXI.” Revista de Educación 356: 509–529.

- Gargano, Terra. 2009. “(Re)conceptualizing International Student Mobility: The Potential of Transnational Social Fields.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (3): 331–346. doi: 10.1177/1028315308322060

- Grusky, David B. 2011. “Theories of Stratification and Inequality.” In The Concise Encyclopedia of Sociology, edited by George Ritzer, and J. Michael Ryan, 622–624. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Guth, Jessica, and Bryony Gill. 2008. “Motivations in the East-West Doctoral Mobility: Revisiting the Question of Brain Drain.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (5): 825–841. doi: 10.1080/13691830802106119

- Halsey, Albert H., Hugh Lauder, Phillip Brown, and Amy Stuart Wells, eds. 1997. Education: Culture, Economy and Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hoffman, David M. 2007. “The Career Potential of Migrant Scholars: A Multiple Case Study of Long-Term Academic Mobility in Finnish Universities.” Higher Education in Europe 32 (4): 317–331. doi:10.1080/03797720802066153.

- Holloway, Sarah L., Sarah L. O’Hara, and Helena Pimlott-Wilson. 2012. “Educational Mobility and the Gendered Geography of Cultural Capital: The Case of International Student Flows between Central Asia and the UK.” Environment and Planning A 44: 2278–2294. doi:10.1068/a44655.

- Institute of International Education. 2016. Open Doors Data. Accessed June 7, 2016. http://www.iie.org/opendoors.

- Jackson, Jane. 2010. Intercultural Journeys: From Study to Residence Abroad. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Jöns, Heike. 2009. ““Brain Circulation” and Transnational Knowledge Networks: Studying Long-Term Effects of Academic Mobility to Germany, 1954–2000.” Global Networks 9 (3): 315–338. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2009.00256.x.

- Jöns, Heike. 2011. “Transnational Academic Mobility and Gender.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 9 (2): 183–209. doi:10.1080/14767724.2011.577199.

- Jöns, Heike. 2015. “Talent Mobility and the Shifting Geographies of Latourian Knowledge Hubs.” Population, Space and Place 21: 372–389. doi:10.1002/psp.1878.

- King, Russell, Allan Findlay, Jill Ahrens, and Mairead Dunne. 2011. “Reproducing Advantage: The Perspective of English School Leavers on Studying Abroad.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 9 (2): 161–181. doi: 10.1080/14767724.2011.577307

- King, Russell, and Parvati Raghuram. 2013. “International Student Migration: Mapping the Field and New Research Agendas.” Population, Space and Place 19 (2): 127–137. doi:10.1002/psp.1746.

- Knight, Jane. 2004. “Internationalization Remodelled: Definition, Approaches, and Rationales.” Journal of Studies in International Education 8 (1): 5–31. doi: 10.1177/1028315303260832

- Knight, Jane. 2016. “Transnational Education Remodeled: Toward a Common TNE Framework and Definitions.” Journal of Studies in International Education 20 (1): 34–47. doi: 10.1177/1028315315602927

- Leung, Maggi W.H., and Johanna L. Waters. 2017. “Educators Sans Frontières? Borders and Power Geometries in Transnational Education.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1276–1291. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300235.

- Li, Mei, and Mark Bray. 2006. “Social Class and Cross-border Higher Education: Mainland Chinese Students in Hong Kong and Macau.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 7 (4): 407–424.

- Lörz, Markus, Nicolai Netz, and Heiko Quast. 2016. “Why Do Students from Underprivileged Families Less Often Intend to Study Abroad?” Higher Education 72: 153–174. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9943-1

- Lulle, Aija, and Laura Buzinska. 2017. “Between a ‘Student Abroad’ and ‘Being from Latvia’: Inequalities of Access, Prestige, and Foreign-earned Cultural Capital.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1362–1378. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300336.

- Madge, Clare, Parvati Raghuram, and Pat Noxolo. 2015. “Conceptualizing International Education: From International Student to International Study.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (6): 681–701. doi: 10.1177/0309132514526442

- Magnan, Sally S., and Michele Back. 2007. “Social Interaction and Linguistic Gain during Study Abroad.” Foreign Language Annals 40 (1): 43–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb02853.x

- Mamiseishvili, Ketevan. 2010. “Foreign-born Women Faculty Work Roles and Productivity at Research Universities in the United States.” Higher Education 60: 139–156. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9291-0

- Manderscheid, Katharina. 2009. “Integrating Space and Mobilities into the Analysis of Social Inequality.” Distinktion: Scandinavian Journal of Social Theory 10 (1): 7–27. doi: 10.1080/1600910X.2009.9672739

- Maringe, Felix, and Steve Carter. 2007. “International Students’ Motivations for Studying in UK HE: Insights into the Choice and Decision Making of African Students.” International Journal of Educational Management 21: 459–475.

- McBurnie, Grant, and Christopher Ziguras. 2007. Transnational Education: Issues and Trends in Offshore Higher Education. London: Routledge.

- Mohajeri Norris, Emily, and Joan Gillespie. 2009. “How Study Abroad Shapes Global Careers.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (3): 382–397. doi: 10.1177/1028315308319740

- Montgomery, Catherine. 2010. Understanding the International Student Experience. London: Palgrave.

- Morano-Foadi, Sonia. 2005. “Scientific Mobility, Career Progression and Excellence in the European Research Area.” International Migration 43 (5): 134–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00344.x

- Murphy-Lejeune, Elisabeth. 2002. Student Mobility and Narrative in Europe: The New Strangers. London: Routledge.

- Naidoo, Rajani. 2011. “Rethinking Development: Higher Education and the New Imperialism.” In Handbook of Globalization and Higher Education, edited by Roger King, Simon Marginson, and Rajani Naidoo, 40–58. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Netz, Nicolai. 2012. “Studienbezogene Auslandsmobilität und Berufsverbleib von Hochschulabsolvent(inn)en.” In Hochqualifiziert und gefragt, edited by Michael Grotheer, Sören Isleib, Nicolai Netz, and Kolja Briedis, 259–313. Hannover: HIS.

- Nieswand, Boris. 2011. Theorising Transnational Migration: The Status Paradox of Migration. New York: Routledge.

- Nowicka, Magdalena. 2012. “Deskilling in Migration in Transnational Perspective. The Case of Recent Polish Migration to the UK.” COMCAD Working Papers No. 112. COMCAD: Bielefeld.

- Ohnmacht, Timo, Hanja Maksim, and Manfred M. Bergman. 2009. Mobilities and Inequality. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Pellegrino Aveni, Valerie A. 2005. Study Abroad and Second Language Use: Constructing the Self. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pfaff-Czarnecka, J., ed. 2017. Das Soziale Leben der Universität – Studentischer Alltag zwischen Selbstfindung und Fremdbestimmung. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Platt, Lucinda. 2011. Understanding Inequalities: Stratification and Difference. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Raghuram, Parvati. 2013. “Theorising the Spaces of Student Migration.” Population, Space and Place 19 (2): 138–154. doi: 10.1002/psp.1747

- Richardson, Julia, and Jelena Zikic. 2007. “The Darker Side of an International Academic Career.” Career Development International 12 (2): 164–186. doi: 10.1108/13620430710733640

- Robertson, Shanti. 2011. “Cash Cows, Backdoor Migrants, or Activist Citizens? International Students, Citizenship, and Rights in Australia.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 34 (12): 2192–2211. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2011.558590

- Rothwell, Nancy. 2002. Who Wants to be a Scientist? Choosing Science as a Career. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Salisbury, Mark H., Michael B. Paulsen, and Ernest T. Pascarella. 2010. “To See the World or Stay at Home: Applying an Integrated Student Choice Model to Explore the Gender Gap in the Intent to Study Abroad.” Research in Higher Education 51 (7): 615–640. doi:10.1007/s11162-010-9171-6.

- Schaer, Martine, Janine Dahinden, and Alina Toader. 2017. “Transnational Mobility among Early-Career Academics: Gendered Aspects of Negotiations and Arrangements within Heterosexual Couples.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1292–1307. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300254.

- Scheibelhofer, Elisabeth. 2006. “Wenn WissenschaftlerInnen im Ausland forschen. Transnationale Lebensstile zwischen selbstbestimmter Lebensführung und ungewollter Arbeitsmigration.” In Transnationale Karrieren: Biografien, Lebensführungen und Mobilität, edited by Florian Kreutzer, and Silke Roth, 122–140. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag.

- Scheibelhofer, Elisabeth. 2010. “Gendered Differences in Emigration and Mobility Perspectives among European Researchers Working Abroad.” Migration Letters 7 (1): 33–41.

- Shavit, Yossi, Richard Arum, and Adam Gamoran, eds. 2007. Stratification in Higher Education: A Comparative Study of 15 Countries. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Shavit, Yossi, and Hans-Peter Blossfeld, eds. 1993. Persistent Inequality: Changing Educational Attainment in Thirteen Countries. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Shen, Yih-Jiun, and Edwin L. Herr. 2004. “Career Placement Concerns of International Graduate Students: A Qualitative Study.” Journal of Career Development 31 (1): 15–29. doi: 10.1177/089484530403100102

- Shinozaki, Kyoko. 2015. Migrant Citizenship from Below: Family, Domestic Work and Social Activism in Irregular Migration. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shinozaki, Kyoko. 2017. “Gender and Citizenship in Academic Career Progression: An Intersectional Meso-scale Analysis in German Higher Education Institutions.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1325–1346. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300309.

- Sondhi, Gundjan, and Russell King. 2017. “Gendering International Student Migration: An Indian Case-study.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1308–1324. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300288.

- Teichler, Ulrich. 2009. “Internationalisation of Higher Education: European Experiences.” Asia Pacific Education Review 10 (1): 93–106. doi: 10.1007/s12564-009-9002-7

- Therborn, Göran. 2001. “Globalization and Inequality: Issues of Conceptualization and Explanation.” Soziale Welt 52 (4): 449–476.

- Tilly, Charles. 1999. Durable Inequality. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tzanakou, Charikleia, and Heike Behle. 2017. “The Intra-European Transferability of Graduates’ Skills Gained in the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1379–1397. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300342.

- Van der Wende, Marijk. 2015. “International Academic Mobility: Towards a Concentration of the Minds in Europe.” European Review 23 (1): S70–S88. doi: 10.1017/S1062798714000799

- Van Mol, Christof. 2014. Intra-European Student Mobility in International Higher Education Circuits. Europe on the Move. London: Palgrave.

- Van Mol, Christof. 2017. “Do Employers Value International Study and Internships? A Comparative Analysis of 31 Countries.” Geoforum 78: 52–60. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.11.014

- Waters, Johanna L. 2009a. “In Pursuit of Scarcity: Transnational Students, ‘Employability’, and the MBA.” Environment and Planning A 41: 1865–1883. doi: 10.1068/a40319

- Waters, Johanna L. 2009b. “Transnational Geographies of Academic Distinction: The Role of Social Capital in the Recognition and Evaluation of ‘Overseas’ Credentials.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 7 (2): 113–129. doi: 10.1080/14767720902907895

- Waters, Johanna L., and Maggi Leung. 2012. “Immobile Transnationalisms? Young People and Their In Situ Experiences of ‘International’ Education in Hong Kong.” Urban Studies 50 (3): 606–620. doi: 10.1177/0042098012468902

- Weber, Max. 1968. Economy and Society. Volume I. Edited by Günther Roth and Claus Wittich. New York: Bedminster Press.

- Wei, Hao. 2013. “An Empirical Study on the Determinants of International Student Mobility: A Global Perspective.” Higher Education 66 (1): 105–122. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9593-5

- Weiss, Anja. 2005. “The Transnationalization of Social Inequality: Conceptualizing Social Positions on a World Scale.” Current Sociology 53 (4): 707–728. doi: 10.1177/0011392105052722

- Weiss, Anja. 2016. “Understanding Physicians’ Professional Knowledge and Practice in Research on Skilled Migration.” Ethnicity & Health 21 (4): 397–409. doi:10.1080/13557858.2015.1061100.

- Welch, Anthony R. 1997. “The Peripatetic Professor: The Internationalisation of the Academic Profession.” Higher Education 34: 323–345. doi: 10.1023/A:1003071806217

- Wilken, Lisanne, and Mette Ginnerskov Dahlberg. 2017. “Between International Student Mobility and Work Migration: Experiences of Students from EU’s Newer Member States in Denmark.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1347–1361. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1300330.

- Williams, Tracey R. 2005. “Exploring the Impact of Study Abroad on Students’ Intercultural Communication Skills: Adaptability and Sensitivity.” Journal of Studies in International Education 9: 356–371. doi: 10.1177/1028315305277681

- Zeng, Zhen, and Yu Xie. 2004. “Asian-Americans’ Earnings Disadvantage Reexamined: The Role of Place of Education.” American Journal of Sociology 109 (5): 1075–1108. doi: 10.1086/381914