ABSTRACT

While in Western literature, migration is generally considered an individual or (nuclear) household phenomenon, Indian context adds the strong presence of parents and extended family to the constellation. This paper addresses how significant others shape the life course events and the migration trajectories of highly skilled Indian migrants to the Netherlands and UK. We employ a qualitative approach to the life course framework to highlight the linked lives that can alter the migration decisions. Our findings are drawn from 47 semi-structured biographic interviews. The results underscore how further migration decisions are often informed by the implications of the different life stages of the linked lives, the key elements being care-giving by and for the parents. Furthermore, we also illustrate how migration provides space for negotiating social norms and expectations: due to the geographical distance between migrants and their parents, the local (non-Indian) context plays a bigger role and thus the need for and timing of conformity with norms can be postponed. The understanding of family life in transnational settings will be enriched when individuals are embedded within the cultural background and linked lives are extended beyond the immediate nuclear family.

Introduction

Each generation is bound to fateful decisions and events in the other’s life course. (Elder Citation1985, 40)

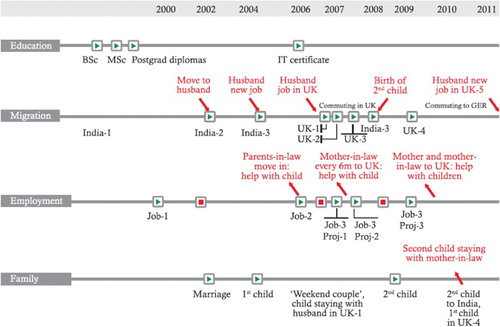

ShamilaFootnote1 was living and working in Mumbai, when her parents arranged her marriage. She then left her job to move in with her husband Ramesh and his family in Hyderabad, and became a housewife. After a few years their first child was born, and thereafter the family moved to Bangalore where Ramesh had found a new job. About a year later, Shamila decided to return to the labour market, therefore her parents-in-law moved in with them in order to help with the child care. Another year later, Ramesh got employed in the UK, so Shamila quit her job to join her husband abroad with their child. She also found a job in the new country, thus Ramesh’s mother migrated to the UK every six months in the following years to take care of their child. Two years after their arrival in the UK, the couple had another child. Both Shamila’s mother and mother-in-law stayed in the UK for months to look after the children. However, as the couple was living and working in different cities during the week and Shamila even had to travel to Germany for work on a weekly basis, they soon decided it was better for the baby to live in India with Ramesh’s mother until both parents found a job in the same city in the UK so that the whole family could live together. Shamila’s life course trajectories and the linked lives relating to migration are depicted in .

The short glance at Shamila’s story exemplifies how the migration of one person initiates migration of their significant others. Migration of an individual should thus not be regarded as an isolated act of movement. To better understand the processes underlying highly skilled migration, it should be viewed as a part of an integral system of previous and future life course events of the migrants and their significant others. Family members are important, if not crucial, in shaping the migration decision of an individual. Findlay et al. (Citation2015) identify linked lives as one of the key elements in the framework for analysing new mobilities across the life course.

The complexity of family migration has been widely acknowledged in the literature (e.g. Bailey and Boyle Citation2004). However, the focus has been by and large on the migration of couples only; the linked lives of parents and children have been studied to a lesser extent in the migration context. Thus in this paper we include parents and children, which will aid in enriching the understanding of migration mechanisms. Bailey, Blake, and Cooke (Citation2004) examine in this line of reasoning how dual-earner couples make relocation decisions in the context of the linkages to their children and parents and conclude that intergenerational links increase the likelihood of return migration.

Furthermore, calls for research on family and residential relocation have often been made, which would take one step further from the focus on the nuclear family and explore the relocation links with the extended family members in the countries of origin (Mulder Citation2007; Cooke Citation2008a; Mulder and Cooke Citation2009). Equally importantly, Mulder and Malmberg (Citation2014) point out the need to incorporate local ties (such as family living close by or a job) of a migrant’s partner; an aspect that has received relatively little attention in family migration research.

Literature related to family migration tends to be largely West-oriented (Valk and Srinivasan Citation2011) and does not discuss the role of parents and the extended family (however, see Mulder and Malmberg Citation2014), which is a central kinship structure in the Indian context. This paper sheds light on the life course choices and patterns of highly skilled Indian migrants in the Netherlands and UK, which are linked to their significant others and which often inform their future migration decisions. By adopting a qualitative approach to the life course framework, this paper seeks to provide insights into how the linked lives shape the life courses of highly skilled Indian migrants in the Netherlands and UK. We explore the ways in which significant others shape the life courses of highly skilled migrants through 47 biographies. Whereas quantitative frameworks tend to overemphasise economic-related outcomes of migration, our qualitative research provides a window into the social and cultural aspects migration decisions and patterns (Smith Citation2004; Kõu Citation2016).

Linked lives and migration

The life course framework views the development of life paths of individuals over time and in social processes (Elder and Giele Citation2009). It facilitates ‘an ecological understanding of people at the nexus of social pathways, developmental trajectories, and social change’ (Daaleman and Elder Citation2007, 87). Elder (Citation1994) uses the term ‘linked lives’ to refer to the interaction with and interdependence of social relationships, and thus to recognise the role of others in forming the life course trajectories and transitions of an individual. The lives are linked through life course events and transitions, which can shape the life course trajectories of other persons. The intersections between the life course trajectories of different individuals are embedded in the social, cultural and spatial context (Bailey and Mulder Citation2017). For instance, migration of a person creates physical distance between them and their parents, and limits the possibilities for intergenerational care exchange. Union formation and childbirth alter the relationships with parents (Kaufman and Uhlendberg Citation1998) through the mechanism of changing life course statuses to a parent-in-law and a grandparent. Union formation itself brings the life courses of spouses closely together and thus creates mutual dependencies: residential relocation of at least one partner is assumed for cohabitation and migration over longer distances often requires changes in the employment trajectories of both partners.

At the policy level, European Union migration laws regard the family as nuclear family only. As a result of this narrow definition, several important issues are overlooked, such as the ‘ … cultural differences in familial relationships, and the role of grandparents or other collateral relations in providing nurturing and support for different members of the family’ (Kofman Citation2004, 246). Silverstein, Gans, and Yang (Citation2006) emphasise that care-giving is an increasingly important part of the life course. Both the physical (‘caring for’) and emotional (‘caring about’) dimensions of care-giving and receiving are present among geographically dispersed families as well (Yeates Citation2012).

With regard to partnerships, previous research has highlighted the importance of linkages between couple migration and the education and employment trajectories of the male versus female partner. It is generally found that the education and employment of the male partner determine the migration decision (e.g. Bielby and Bielby Citation1992), leaving the female partner into the role of a tied mover whose employment status is harmed by migration (Boyle et al. Citation2001). More recently it has been argued that instead of sacrificing their professional careers, (highly educated) women seek opportunities in the migration process even when co-migrating and therefore become active agents rather than passive movers (Hiller and McCaig Citation2007; Kõu and Bailey Citation2014). Furthermore, tied staying most likely occurs more frequently than tied moving and affects men and women equally (Smits, Mulder, and Hooimeijer Citation2003; Cooke Citation2013).

The presence of children adds a pivotal dimension to the family migration and to the gender perspective within that. Cooke (Citation2008b) describes how couples adopt much more egalitarian gender norms and roles until they have children, but traditional gender norms (i.e. the female partner as a homemaker and the male partner as the breadwinner) emerge once the couple has a child. It is thus rather the ‘trailing mother’ than ‘trailing wife’ effect that has negative impact on women’s employment status after migration (Cooke Citation2001). The wife is more likely to have a job than a career (Becker and Moen Citation1999; Moen and Yu Citation2000): it is a gendered strategy which involves flexible number of work hours and prescribes the role as a primary caregiver (Leung Citation2017). Moen and Yu (Citation2000) conclude that it is not the participation in or exit from labour market, but hours in paid work that significantly differentiate gender roles.

The literature thus suggests that linked lives can play a substantial role in life course decisions of migrants. For instance, the care expectations have a direct implication for migrant families who have to arrange the care across borders or relocate for that purpose. This paper focuses on high-skilled migrants and their spouses who are very likely to be highly skilled as well. The higher the wife’s education, the more prone the family is to return to their country of origin (Saarela and Finnäs Citation2013), adding to the family dimension of international migration.

Linked lives in India

Family is considered to be the centre of social organisations in India (Choudhry Citation2001). Close family ties are produced and maintained by and large through the extended or joint family system. Lamb (Citation2011, 501) defines a joint family as ‘any multigenerational household including at least one senior parent and one married adult child (generally a son) with spouse’. For people in India aged 65 and above, co-residence with (grand)children is the most common living arrangement. Data pertaining to the census in 2011 show that households with 6–8 persons are the largest group, or 24.9% of the total population (Census of India Citation2011), at the same time total fertility rate was 2.5 (World Bank Citation2014).

One of the prominent features of India’s family system is patrifocality. It focuses specifically on the extended family and underlines the centrality of males through mechanisms such as patrilocal residence and patrilineal succession (Seymour Citation1995). The wife is thus expected to move to the extended family household of her husband, and she is not only considered to marry her husband, but equally importantly she will then be regarded as a vital part of his family (Mines and Lamb Citation2002). The life course of a woman will be strongly linked not only to her husband, but also to his parents and possibly to other members of the extended family (see Roohi Citation2017).

In the Indian context, marriage is viewed as ‘an economic and social bond for religious and cultural groups’ and as ‘a key vehicle through which a family’s status is expressed or improved’ (Bhopal Citation2011, 433). Because marriage is regarded to be contracted between families rather than individuals, arranging marriage for their children is one of the most salient concerns for parents (Mooney Citation2006; Gopalkrishnan and Babacan Citation2007). More than 90% of Indians marry through the arranged marriage system (Mullatti Citation1995). Parents and other senior kin seek for marriage partners based on various criteria, such as the education, employment, caste and religion of the candidate and the wealth and reputation of the family. In urban India and in the Indian diaspora, more recently, parents and ‘marriageable’ men and women are relying on matrimonial websites to find a spouse. It has been argued that the easy access to such websites weakens the role of parents as gatekeepers who otherwise control the information about potential matches (Seth and Patnayakuni Citation2012). Particularly in the recent decade, so-called love marriages – as opposed to arranged marriages – have increasingly become popular, as well as the combination of those two (Netting Citation2010; Mukhopadhyay Citation2012). However, arranged endogamous marriage (i.e. within a social group) remains the norm for middle-class Indians (Fuller and Narasimhan Citation2008).

Earlier research has established that the higher the education a young woman has, the more say she can have in choosing a marriage partner (Bhopal Citation2011). At the same time, participation in tertiary education has remarkably increased the age at marriage of Indian women (Seymour Citation1995; Maslak and Singhal Citation2008; Desai and Andrist Citation2010) and in Asia generally (Jones Citation2010) during the past few decades. Fuller and Narasimhan’s (Citation2013) research in South India confirmed that the position of women in the society has significantly improved, however, gender inequality is still deeply rooted in the domestic division of labour and in prioritising husbands’ careers over wives’.

Although highly educated women in India marry later than women without a tertiary education, the time span between the first and the second child tends to be much shorter (Banerjee Citation2006). Women tend to remain the primary caretakers in dual-earner couples, and because childcare facilities are not available like in Europe (Valk and Srinivasan Citation2011), they have to rely solely on the care support of their parents and/or extended family.

The extended family is heavily involved in child-rearing, and they are responsible for care distribution and socialisation, but this is disrupted by migration. This paper looks further into how the dense family system has to be adjusted due to migration.

Data and methods

A qualitative approach in researching the life course of migrants allows for an understanding of the crucial ways significant others influence the life courses in general and migration trajectories in particular (Kõu et al. Citation2015). We therefore adopted qualitative methods to get detailed accounts of the life courses of highly skilled migrants from the micro perspective. Specifically, a biographic approach assists in organising such accounts (Bailey Citation2009) and prioritises the social embeddedness of individuals (Halfacree and Boyle Citation1993).

Our results are based on interviews with 47 highly skilled Indian migrants in the Netherlands and UK to observe potential dissimilarities due to institutional context. The highly skilled visa schemes in those two countries differ in terms of origins, requirements and benefits for the migrants (see Kõu and Bailey Citation2014). The research participants were sought among Indian migrants working in a professional sector job, aged 25–40, who were preferably holders of a knowledge migrant visa (the Netherlands) or a Highly Skilled Migrant Programme or Tier 1 or Tier 2 visa (the UK), and who had lived or intended to live in the respective country for at least one year. The recruitment sites were Amsterdam, Eindhoven and Groningen in the Netherlands, and London and Southampton in the UK as to provide a broad picture of Indian professionals in both countries in geographical terms. The data collection took place between June 2010 and August 2011. 36 participants were male and 11 female; 23 of them were married and another 11 engaged or in a relationship. All five married women moved on a dependant migrant visa, whereas all married men were primary migrants. No couples were interviewed. The majority of the participants worked in the sectors of IT services, engineering industry, business, education and research.

The first part of the interview draws from the biographic-narrative interview method (see Wengraf Citation2001) whereby the participant was asked to tell his or her life story in order to reveal the life events and experiences to which the participant attaches the most value. Later the narrated biography was discussed in more detail and, if necessary, additional topics were raised by the interviewer to cover the interview themes of education, employment, migration and family trajectories as well as the role of significant others in shaping these trajectories. The interview transcriptions were inductively analysed by creating codes, categories and themes with the aid of qualitative software MAXQDA. The main themes regard the mechanisms of linked lives through which parents and spouse/partner had directed these life course trajectories of the participants.

Findings

The vast majority of participants suggested that parents in particular and extended family in general (i.e. siblings, particularly older siblings, uncles and aunts and their spouses, and grandparents) had directly or indirectly shaped their behaviour in all four life trajectories – education, employment, migration and family – examined in this study. Although the findings are discussed regarding the role of parents, members of the extended family often provided similar advice and support, which was almost always appreciated by the participants. As Ashwin (41, UK) put it: Family is important, everything is related to that. Because parents’ influence started the earliest and extended to all domains of life, their role is discussed first, followed by the spouse/partner.

Linked lives of parents

Three different types of influence from the family members emerged. First and foremost, parents derived their authority from the cultural norms and expectations related to traditions, for example by enforcing the normative age at marriage. Second, participants gave weight to the information provided by family members, for instance, when deciding on the specialisation for (under)graduate studies. Third, joint decision-making occurred when parents and extended family members presented the participants with different options regarding issues such as the choice of marriage partner, however, the participants had an equal share in the final decision. Whereas in Western societies parents encourage their (adult) children towards individual decision-making and independence, in South Asian context the parents and elders are very much engaged in decision-making and children are expected to follow their advice (Deepak Citation2005).

While nearly all participants indicated that they had considered their parents’ advice in most of their important life course decisions, some claimed they followed the advice in order to comply with the cultural norms, even if they initially were not content with the advice:

It’s different here. In India, your dad is the central figure. So, he’s the main person who decides. We all follow, but … I’m happy what decisions he made, because he always sees what is the benefit for us. And we never said ‘No,’ me and my brother. We were not happy to go to and study in a different place and things. But at the end of the day we feel it back, ‘Yes, that’s a wise decision. (Aroop, 28, UK)

Directing the education trajectory

Parents often advised which field of study to choose. The advice was to a large extent based on the ‘market situation’, regarding the current trends on the labour market as well as the prospective earnings. By and large, the preferred fields were engineering, IT and medicine. These occupations were reported as means for upward mobility among middle class, as well as for societal respect (see Kirk, Bal, and Janssen Citation2017; Roohi Citation2017). Particularly engineering and IT are in high demand also in foreign countries, thus it can be argued that parents were paving the road for their children to live and work abroad. Parents usually paid for private schooling to secure higher quality of education for their children, thus their contribution to participants’ education is notable throughout the education trajectory. The three preferred fields of tertiary education were expected to lead to jobs which would provide a payoff of the investment and parents were therefore reluctant to take risks with other occupations.

Following parents’ advice sometimes came at the price of neglecting own aspirations, but there was little or no space for questioning the advice. Although the lack of autonomy was not appreciated in such cases, most of the participants reported that in order to show respect they adhered to the wishes of the parents rather than followed their own ambitions:

I was forced [to study engineering] because my parents thought that was the best for me. My father thought. He has a double qualification, double degree or something. So, it didn’t appear very good for him to just go for arts or science. I wanted to do something really artistic or take probably little of management, Bachelors of Management or psychology. I was totally not interested in engineering. I was forced into it by my dad and it wasn’t my choice. And then, though I spoke, it didn’t really work or it didn’t really matter. (Sonali, 26, NL)

You just don’t want to take more and more money out of them [parents], then you have to follow what they say. It comes with a price, there is no free lunch. Then I would have to marry who they say and, you know. (Shaili, 32, UK)

Directing the migration trajectory

Nearly all participants had made the decision for the move abroad themselves, although often after consulting with family members and friends. The parents of only one participant were initially against her wish to move to Europe for obtaining a doctoral degree, because in their traditional rural community all women were expected to become housewives and not pursue postgraduate studies or a professional career. Eventually she convinced her parents and was allowed to follow the atypical life path of a village girl.

Parents and extended family facilitated migration through personal experiences of living abroad. Some participants indicated that family members also provided financial help with costs related to travel, accommodation and tuition fees. Among high-skilled Indians, it is common to have family members who have studied or worked abroad, which has led to a situation where migration is a normative part of a person’s career. The existence of a culture of migration (cf. Kandel and Massey Citation2002) lowers barriers to migration, as leaving family members (temporarily) behind occurs frequently. The wide-spread migration trend has led to a situation where living abroad is also seen as a means to gain status.

One category of people who move abroad are people whose parents want to send their kids abroad as a status symbol. Just like buying a sports car or having good fashion, anything. Having a foreign education and bit of an accent is something that you give your kids; it’s part of what you do. (Vikram, 31, UK)

I decided ‘Okay, now I’ll look for a job to support my family and my husband.’ Because my husband is the only son, he’s got two sisters and he has to support his parents and his grandparents, it was a joint family. So I started working, my mother-in-law came over to help take care of the baby. (Shamila, 34, UK)

The one other main reason why people don’t stay in Holland, is that … For example, my parents are here now. Getting visa for them is a very difficult thing. You get only 90-days visa. Another friend of mine is in US. His father and mother went to visit him, they got ten-years visa! His father is not going to go there, he doesn’t belong in United States, he doesn’t want to go and stay there through the cold winter and all that. They stayed there for four months, five months. Life is lot more easier for them, [grandparents] take care of those kids and then go back to India. [---] It just makes it very hard for me to stay alone so far away from my parents. So a lot of people go from here back to India not because they don’t like the life here, but because they can’t be close to their own parents. (Rahul, 38, NL)

But even culturally it’s not that acceptable [to live separately from parents]. If I moved out our home for no other reason but to live by myself … that would immediately make things sound very suspicious. Everyone would’ve been like ‘Oh, there’s something wrong there!’ It’s not normal practice, even today. Although people’s attitudes are changing. When I speak with my parents about moving back to India, they assume that I will come back and live with them. Although I have said that I won’t be living with them. Doesn’t mean that I don’t want to be with them, I just got used to not having my parents around. Not that they are conservative in any way, but I think it’s very difficult to change that mind-set. (Rakesh, 31, UK)

Directing the family trajectory

One of the primary responsibilities of parents in India is arranging the marriage for their children (Mooney Citation2006). Two important factors emerged from participants’ reflections on the topic: the timing of marriage – a certain ‘right age’ for both males and females to get married, which should be respected – and the requirements for the spousal candidate. Some mentioned the ‘compatibility’ of candidates, or the match of various background characteristics such as caste, language, religion and education. A good tertiary education was a central criterion for the potential marriage partner, as all participants had completed higher education. However, the relationship is not straightforward as education can both enhance and complicate a woman’s marriageability (Seymour Citation1995). If a young woman is ‘overeducated’, then finding a spouse can be very difficult, because of age issues and the common assumption that the future wife should not have a higher educational level or more degrees than the husband (cf. Fuller and Narasimhan Citation2008).

Among the participants there were different ways of accepting that parents would arrange their marriage. The most prevailing way was to not question this issue but to acknowledge the cultural norms and the dominant role of parents in the arranged marriage system. However, there is increasingly more space for negotiations in this matter. Almost all participants were allowed to choose between the candidates proposed by their parents, instead of parents presenting only one candidate based on the largest overlap in terms of background requirements and not taking into account the personal match/liking between the potential spouses.

One thing is support and second one is guidance you get from your parents, basically. They have more practical experience. What kind of issues could lead into your life when you have to live together. So they would be knowing you personally, your character and yourself from the birth. So they know what you are and what matters best for you. So nowadays I think it’s open world and everybody’s seen the world outside. It’s up to them which way they want to go. It’s not completely rational system, it’s also a moral system. (Venkatesh, 32, NL)

But they [parents] say like ‘Okay, if you have to do your marriage by your own, if you want to choose your thing, why are we there as your parents?’ I was like Okay, their mind-set is like they have their life only for their children, they are so much dedicated, so much love and affection they have, okay, that’s true, but you know, it’s a suffocation, right? When I discuss this point with my Indian friends here, they say ‘You don’t have respect for elders. (Sanjita, 25, NL)

Linked life of the spouse/partner

While parents’ influence on the life course choices made by the participants was extended to all four major life course trajectories studied in this paper (education, employment, migration and family) through complying with norms, providing information or joint decision-making, the role of the spouse/partner in shaping the life course mainly concerns joint decision-making in migration and family trajectories. In the pre-relationship/pre-marriage stage, the participants had to take into account only the (anticipated) changes in their own life course, whereas as a couple the aspirations, needs and wishes of the spouse/partner became equally important when making life course plans and decisions. However, in case of migration, the husband often seemed to be the primary decision-maker.

Directing the education and employment trajectories

In most cases, the participants or their spouse had to leave their job in India or other country of residence for the family reunion in the Netherlands or UK. In this situation, all participants considered it crucial to secure relevant employment or (post-)graduate education for their spouses. The traditional housewife was not a common role among the spouses: the dominant mentality in India is that if one is abroad, one has to work and make the maximum use of time abroad to earn capital for further life (Osella and Osella Citation2009). Mutual employment opportunities were also central among participants planning a future career in India:

I don’t want her to become a housewife. I also want her to engage in some sort of work she’s interested in. And so I applied [for a job] in Bangalore, I applied in Hyderabad, and I applied in Delhi, I applied in Bombay. I applied in all these, you know, A-class cities, metropolitan cities. Where she can also have some opportunity, I can also have some opportunity, so both of us can make a good family. (Pratul, 28, UK)

Some male participants reported how they had made a change in their career so that their wives could follow professional ambitions, or took on a career path that enabled them to spend more time with family instead of putting long hours into workplace. For instance, Bharat (35, UK) had a well-paid job in sailing as an officer and made good career progression, however, the job required him to be at sea for five months at a time. After being married for some time, he decided to quit his career at sea to be able to be together with his wife on a daily basis.

I could have, you know, been a captain of a ship. So sometimes I do miss that, but I think I do understand that this normal life what I have now is very good. I go to work and in the evening I come back, I’m home with family, so it’s like a normal life, you see. When you make this kind of compromise, because of family, I think this is also quite important, although when you are at sea you would really get paid well, but … You know, for the sake of family and future, I kind of decided that it’s fine. (Bharat, 35, UK)

Directing the migration trajectory

Being in a relationship with or married to a highly skilled migrant almost inevitably implies migration. Due to the prevailing patrilocality in India, a woman is expected to move to her husband’s home, thus putting women in the position of tied internal migrants. Most of the spouses were open for new opportunities in a new country, but a few revealed that they only moved abroad to join their husbands and that they would have preferred to stay in India. Although they were initially in the role of a tied mover, each one of them eventually found relevant employment or postgraduate studies matching their qualifications and skills.

At that time [before marriage] my wife was working in Chennai. She was working with a good company. She was a very career-oriented person, you know. So she had to leave that job that time simply because she was getting married to me. It’s like in the culture, where the husband goes, the wife has to go. (Bharat, 35, UK)

Coming to the Netherlands was not my decision at all. It was his [husband’s]. And he almost forced it on me, though he thinks he has asked me and we were quite okay but … [---] I could have put my foot down and said not to move at all, but I didn’t want to spoil his enthusiasm. And I had taken a break away from job, for myself, so … Well, though it may sound like a sacrifice, it’s really not [laughs]. (Sonali, 26, NL)

Because my parents also searched for persons who match me, who have permanent residence, the Green Card in USA or permanent residence in European countries. Then I said no, because I don’t want my … person to have permanent residence here. If they have it here, they never come back to India. And I want to go back. (Sanjita 25, NL)

Directing the family trajectory

To a certain extent, the events in parallel life course careers seemed to co-occur less frequently for women than men: the female participants had a strong preference of completing (post)graduate studies before entering the family trajectory. On the other hand, some men also reported to bring sacrifices to meet their long-term goals: they focused only on work for a number of years in order to have a better future in terms of career prospects, sufficient savings and starting a family. Migration may thus lead to postponement of marriage and childbirth.

I came here for professional life. I’m too busy with my work. Start at nine, finish at eight, sometimes I’ll be busy in the weekends as well. So no time for personal life. Because I want to grow professionally. [---] Some things are happening in European market. That has created lot of opportunities for professionals. It’s going to be there for another two or three years, I want to make most of this. For I don’t want to have any commitment at this time. That’s why I’m not having any personal side. (Amit, 30, UK)

It is like investment of your time for 4–5 years, and make sacrifices. Not in touch with family, your friends, just devote your time and energy on your research, write some good papers. And grow as a researcher and make a good network. And then apply in Indian universities, go, get a job there. And then go back, and settle down. I can see myself next year: I am sitting in some good academic organisation in India, as an assistant professor. And also get married to my long-last girlfriend. That was kind of the bigger picture. Both sides were happy to sacrifice this four years’ or five years’ time of our life, so that our next phase of life would be good. (Pratul, 28, UK)

The links between the lives of the couples can thus bring about a variety of migration accounts and these accounts depend largely on the employment or education trajectories of both partners. For spouse migration, key trajectory is that of employment. The gender component is strongly present, as by and large, the male makes the migration decision and the woman follows. Our findings suggest, however, that even if women are tied movers during the migration event itself, they enter the labour market in a short time, particularly if the institutional conditions are favourable.

Conclusion

This paper explored how parents, extended family and spouse/partner shape the life course decisions of high-skilled Indian migrants in the Netherlands and UK. Our findings showcase substantial impact of linked lives on various levels throughout the life course and in multiple trajectories. The more people are involved in life course decision-making, the more complex the process becomes.

While in Western literature migration is generally considered an individual or (nuclear) household phenomenon, the Indian context adds to the constellation a strong presence of extended family in general and parents in particular. Their prominent role in decision-making is visible throughout the life course. It is important to look at the migration process as a whole (Kõu and Bailey Citation2014), however, previous literature has often focused only on the role of family members in pre- or post-migration stages. This supports Pixley’s (Citation2008, 158) plea for analysing ‘patterns of multiple decisions over the life course rather than relying only on the observations of individual geographic moves found in most migration research’. Our study contributes to the knowledge of how parents and extended family shape the life course in general and migration decisions in particular. First, family members facilitate migration through a migration norm, educational choices and by means of financial support. Second, the migration experience is influenced by negotiating social norms and expectations with family members, as well as by providing support for child care. Finally, future migration plans are largely directed by care-giving for parents and care of grandchildren.

Our findings suggest that different actors have different roles in directing the life course stages. The Indian social norm of the (extended) family being actively involved predetermines the educational and marital choices to a large extent, whereas the different stages in the care-giving cycle reveal cultural schemas regarding age-role behaviour and often can trigger the migration of and to the parents. Parental influence takes a large share in one’s pre-relationship/pre-marriage life, while in post-marriage stage the spouse has increasingly more impact on the decision-making than the parents. Whereas in other domains joint decision-making occurred within the couples, the male spouses tended to initiate migration, however, having in mind the professional opportunities for their wives in the country of destination.

As migration creates an exposure to Western cultural and social environment, Indian norms are consequently often less valued or become irrelevant in the Western cultural milieu (cf. Gardner and Osella Citation2003). Family ties are still highly valued, but at the same time the high-skilled migrants are more independent from their families due to both distance created by migration and their higher educational levels and career development. The importance of parental advice is also changing: due to the geographical distance between the participants and their parents, the local (non-Indian) context plays a bigger role and thus the need for and timing of conformity with norms can be postponed in case of the highly skilled. However, parents are not only a regulating authority but also a source of support, particularly for care provision in a transnational family. Respect to values is also beneficial for migrants: it gives a sense of belonging to family in India and retains links with homeland, especially when preparing to return.

In Indian society, family values are highly honoured, whereas in the Western societies the individual is central. Migration can therefore be viewed as a pathway towards individualism, especially in the gender dimension. Women have more independence and an equal say within marriage as they are also highly skilled, which gives them different bargaining power than the less-educated. ‘Through the migration process and as a result of increased access to education women can actively transform and modify transitions’ (Samuel Citation2010, 108) and hence the need for conforming parents’ strict expectations and cultural norms, such as age at marriage or childbirth, is renegotiated to a certain degree.

In terms of the institutional setting, our findings point out that for facilitating high-skilled migration, the availability of not only spousal benefits but also parental visa is relevant. A major difference we observed between the two countries was that the participants in the Netherlands experienced the visa regulations as restrictive for their parents, which was considered a substantial disadvantage in the light of the central role of grandparents in child-rearing in India. The Dutch knowledge migrant policies are mainly focused on filling profitable jobs and pay less attention to social and cultural aspects, which are equally important from the point of view of the migrants. Thus far, the policies have been geared towards nuclear family and are therefore unaccommodating for grandparents whose role in the migration process has not been acknowledged. One of the main contributions of parents of migrants is helping with child care and therefore directly or indirectly enabling the migrant couple to maintain dual careers.

With a focus on linked lives we have been able to evaluate the role of significant others in the life courses of migrants. The findings of this paper suggest that research on linked lives cannot be limited to one geographical area or to the immediate nuclear family. Allowing a broader focus will enrich our understanding of family life in transnational settings.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants for sharing their stories with us. We would also like to thank Leo van Wissen and anonymous reviewers for providing valuable comments on earlier versions of this paper. We are grateful for financial support from the Ubbo Emmius Fund at the University of Groningen.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 The names of persons and places are fictitious in order to protect the anonymity of the participants.

2 However, none of the female participants had got married after migration, thus the migration of a male spouse concerns migration plans, not actual behaviour.

References

- Bailey, A. J. 2009. “Population Geography: Lifecourse Matters.” Progress in Human Geography 33 (3): 407–418. doi:10.1177/0309132508096355.

- Bailey, A. J., M. K. Blake, and T. J. Cooke. 2004. “Migration, Care, and the Linked Lives of Dual-earner Households.” Environment and Planning A 36 (9): 1617–1632. doi:10.1068/a36198.

- Bailey, A. J., and P. Boyle. 2004. “Untying and Retying Family Migration in the New Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (2): 229–241. doi:10.1080/1369183042000200678.

- Bailey, A., and C. H. Mulder. 2017. “Highly Skilled Migration Between the Global North and South: Gender, Life Courses and Institutions.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2689–2703. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314594.

- Banerjee, S. 2006. “Higher Education and the Reproductive Life Course. A Cross-cultural Study of Women in Karnataka (India) and the Netherlands.” PhD diss., University of Groningen. Amsterdam: Dutch University Press.

- Becker, P. E., and P. Moen. 1999. “Scaling Back: Dual-earner Couples’ Work-Family Strategies.” Journal of Marriage and Family 61 (4): 995–1007. doi:10.2307/354019.

- Bhopal, K. 2011. “‘Education Makes You Have More Say in the Way Your Life Goes’: Indian Women and Arranged Marriages in the United Kingdom.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 32 (3): 431–447. doi:10.1080/01425692.2011.559342.

- Bielby, W. T., and D. D. Bielby. 1992. “I Will Follow Him: Family Ties, Gender-Role Beliefs, and Reluctance to Relocate for a Better Job.” American Journal of Sociology 97 (5): 1241–1267. doi:10.1086/229901.

- Boyle, P., T. J. Cooke, K. Halfacree, and S. Smith. 2001. “A Cross-national Comparison of the Impact of Family Migration on Women’s Employment Status.” Demography 38 (2): 201–213. doi:10.1353/dem.2001.0012.

- Census of India. 2011. “ Data Sheet: Figures at Glance.” http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/hlo/Data_sheet/India/Figures_Glance.pdf.

- Choudhry, U. K. 2001. “Uprooting and Resettlement Experiences of South Asian Immigrant Women.” Western Journal of Nursing Research 23 (4): 376–393. doi: 10.1177/019394590102300405

- Cooke, T. J. 2001. “‘Trailing Wife’ or ‘Trailing Mother’? The Effect of Parental Status on the Relationship Between Family Migration and the Labor-Market Participation of Married Women.” Environment and Planning A 33: 419–430. doi:10.1068/a33140.

- Cooke, T. J. 2008a. “Migration in a Family Way.” Population, Space and Place 14: 255–265. doi:10.1002/psp.500.

- Cooke, T. J. 2008b. “Gender Role Beliefs and Family Migration.” Population, Space and Place 14: 163–175. doi:10.1002/psp.485.

- Cooke, T. J. 2013. “All Tied Up: Tied Staying and Tied Migration Within the United States 1997 to 2007.” Demographic Research 29: 817–836. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2013.29.30

- Daaleman, T. P., and G. H. Elder, Jr. 2007. “Family Medicine and the Life Course Paradigm.” The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine 20 (1): 85–92. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2007.01.060012.

- Deepak, A. C. 2005. “Parenting and the Process of Migration: Possibilities Within South Asian Families.” Child Welfare 84 (5): 585–606. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16435652.

- Desai, S., and L. Andrist. 2010. “Gender Scripts and Age at Marriage in India.” Demography 47 (3): 667–687. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0118.

- Elder, G. H., Jr. 1985. “Perspectives on the Life Course.” In Life Course Dynamics: Trajectories and Transitions, edited by G. H. Elder, Jr. , 23–49. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Elder, G. H., Jr. 1994. “Time, Human Agency, and Social Change: Perspectives on the Life Course.” Social Psychology Quarterly 57 (1): 4–15. doi:10.2307/2786971.

- Elder, G. H., Jr. and J. Z. Giele. 2009. “Life Course Studies: An Evolving Field.” In The Craft of Life Course Research, edited by G. H. Elder, Jr., and J. Z. Giele, 1–24. London: The Guilford Press.

- Findlay, A., D. McCollum, R. Coulter, and V. Gayle. 2015. “New Mobilities across the Life Course: A Framework for Analysing Demographically Linked Drivers of Migration.” Population, Space and Place 21: 390–402. doi:10.1002/psp.1956.

- Fuller, C. J., and H. Narasimhan. 2008. “Companionate Marriage in India: The Changing Marriage System in a Middle-class Brahman Subcaste.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14: 736–754. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.00528.x.

- Fuller, C. J., and H. Narasimhan. 2013. “Marriage, Education, and Employment among Tamil Brahman Women in South India 1891–2010.” Modern Asian Studies 47: 53–84. doi:10.1017/S0026749X12000364.

- Gardner, K., and F. Osella. 2003. “Migration, Modernity and Social Transformation in South Asia: An Overview.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 37 (1–2): v–xxviii. doi:10.1177/006996670303700101.

- Gopalkrishnan, N., and H. Babacan. 2007. “Ties that Bind: Marriage and Partner Choice in the Indian Community in Australia in a Transnational Context.” Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 14 (7): 507–526. doi:10.1080/10702890701578498.

- Halfacree, K. H., and P. J. Boyle. 1993. “The Challenge Facing Migration Research: The Case for a Biographical Approach.” Progress in Human Geography 17: 333–348. doi:10.1177/030913259301700303.

- Hiller, H. H., and K. S. McCaig. 2007. “Reassessing the Role of Partnered Women in Migration Decision-Making and Migration Outcomes.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 24 (3): 457–472. doi:10.1177/0265407507077233.

- Jones, G. W. 2010. “Changing Marriage Patterns in Asia.” Asia Research Institute Working Paper Series No. 131. Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

- Kandel, W., and D. Massey. 2002. “The Culture of Mexican Migration: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis.” Social Forces 80 (3): 981–1004. doi:10.1353/sof.2002.0009.

- Kaufman, G., and P. Uhlendberg. 1998. “Effects of Life Course Transitions on the Quality of Relationships Between Adult Children and Their Parents.” Journal of Marriage and the Family 60: 924–938. doi:10.2307/353635.

- Kirk, K., E. Bal, and S. R. Janssen. 2017. “Migrants in Liminal Time and Space: An Exploration of the Experiences of Highly Skilled Indian Bachelors in Amsterdam.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2771–2787. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314600.

- Kofman, E. 2004. “Family-related Migration: A Critical Review of European Studies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (2): 243–262. doi:10.1080/1369183042000200687.

- Kõu, A. 2016. Life Courses of Highly Skilled Indian Migrants in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. Enschede: Ipskamp Printing.

- Kõu, A., and A. Bailey. 2014. “‘Movement is a Constant Feature in My Life’: Contextualising Migration Processes of Highly Skilled Indians.” Geoforum 52: 113–122. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.01.002.

- Kõu, A., L. van Wissen, J. van Dijk, and A. Bailey. 2015. “A Life Course Approach to High-skilled Migration: Lived Experiences of Indians in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (10): 1644–1663. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1019843.

- Lamb, S. 2011. “Ways of Aging.” In A Companion to the Anthropology of India, edited by I. Clark-Decès, 500–516. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Leung, M. W. H. 2017. “Social Mobility via Academic Mobility: Reconfigurations in Class and Gender Identities among Asian Scholars in the Global North.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2704–2719. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314595.

- Maslak, M. A., and G. Singhal. 2008. “The Identity of Educated Women in India: Confluence or Divergence?” Gender and Education 20 (5): 481–493. doi:10.1080/09540250701829961.

- Mines, D. P., and S. Lamb. 2002. “The Family and the Life Course: Introduction.” In Everyday Life in South Asia, edited by D. P. Mines, and S. Lamb, 7–10. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Moen, P., and Y. Yu. 2000. “Effective Work/Life Strategies: Working Couples, Work Conditions, Gender, and Life Quality.” Social Problems 47 (3): 291–326. doi: 10.2307/3097233

- Mooney, N. 2006. “Aspiration, Reunification and Gender Transformation in Jat Sikh Marriages From India to Canada.” Global Networks 6 (4): 389–403. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2006.00151.x.

- Mukhopadhyay, M. 2012. “Matchmakers and Intermediation. Marriage in Temporary Kolkata.” Economic & Political Weekly 47 (43): 90–99. http://www.epw.in/review-womens-studies/matchmakers-and-intermediation.html.

- Mulder, C. H. 2007. “The Family Context and Residential Choice: A Challenge for New Research.” Population, Space and Place 13 (4): 265–278. doi: 10.1002/psp.456

- Mulder, C. H., and T. J. Cooke. 2009. “Family Ties and Residential Locations.” Population, Space and Place 15 (4): 299–304. doi: 10.1002/psp.556

- Mulder, C. H., and G. Malmberg. 2014. “Local Ties and Family Migration.” Environment and Planning A 46 (9): 2195–2211. doi:10.1068/a130160p.

- Mullatti, L. 1995. “Families in India: Beliefs and Realities.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 26 (1): 11–25. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41602364.

- Netting, N. S. 2010. “Marital Ideoscapes in 21st-Century India: Creative Combinations of Love and Responsibility.” Journal of Family Issues 31 (6): 707–726. doi:10.1177/0192513x09357555.

- Osella, F., and C. Osella. 2009. “Muslim Entrepreneurs in Public Life Between India and the Gulf: Making Good and Doing Good.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 15 (s1): S202–S221. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2009.01550.x.

- Pixley, J. E. 2008. “Life Course Patterns of Career-Prioritizing Decisions and Occupational Attainment in Dual-earner Couples.” Work and Occupations 35 (2): 127–163. doi:10.1177/0730888408315543.

- Roohi, S. 2017. “Caste, Kinship and the Realization of ‘American Dream’: High Skilled Telugu Migrants in the U.S.A.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2756–2770. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314598.

- Saarela, J., and F. Finnäs. 2013. “The International Family Migration of Swedish-speaking Finns: The Role of Spousal Education.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (3): 391–408. doi:10.1080/1369183x.2013.733860.

- Samuel, L. 2010. “Mating, Dating and Marriage: Intergenerational Cultural Retention and the Construction of Diasporic Identities among South Asian Immigrants in Canada.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 31 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1080/07256860903477712.

- Seth, N., and R. Patnayakuni. 2012. “Online Matrimonial Sites and the Transformation of Arranged Marriage in India.” In Gender and Social Computing. Interactions, Differences and Relationships, edited by C. Romm, 272–295. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Seymour, S. 1995. “Family Structure, Marriage, Caste and Class, and Women’s Education: Exploring the Linkages in an Indian Town.” Indian Journal of Gender Studies 2 (1): 67–86. doi:10.1177/097152159500200104.

- Silverstein, M., D. Gans, and F. M. Yang. 2006. “Intergenerational Support to Aging Parents: The Role of Norms and Needs.” Journal of Family Issues 27: 1068–1084. doi:10.1177/0192513x06288120.

- Singh, A. 2014. Indian Diaspora: Voices of Grandparents and Grandparenting. 720 Vols. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Smith, D. P. 2004. “An ‘Untied’ Research Agenda for Family Migration: Loosening the ‘Shackles’ of Past.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (2): 263–282. doi:10.1080/1369183042000200696.

- Smits, J., C. H. Mulder, and P. Hooimeijer. 2003. “Changing Gender Roles, Shifting Power Balance and Long-distance Migration of Couples.” Urban Studies 40 (3): 603–613. doi:10.1080/0042098032000053941.

- Valk, R., and V. Srinivasan. 2011. “Work-Family Balance of Indian Women Software Professionals: A Qualitative Study.” IIMB Management Review 23 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1016/j.iimb.2010.10.010.

- Wengraf, T. 2001. Qualitative Research Interviewing: Biographic Narrative and Semi-Structured Methods. London: Sage.

- World Bank. 2014. “Fertility Rate, Total (Births per Woman).” http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN.

- Yeates, N. 2012. “Global Care Chains: A State-of-the-art Review and Future Directions in Care Transnationalization Research.” Global Networks 12 (2): 135–154. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0374.2012.00344.x.