ABSTRACT

With China’s ongoing transition from a labour-intensive economy to a knowledge-driven one, the state has vigorously promoted diasporic Chinese technopreneur returnees as a new dynamic force for the nation’s economic development. This article examines the technopreneurs’ interactions with the state, focusing on how the government has orientated and structured them into the state’s national and globalisation agendas. We argue that the acquisition of political capital by the technopreneurs is a critical factor to successfully convert transnational cultural capital into economic capital. We also analyse the mechanisms and limitations of the top-down relationship between the state and diasporic technopreneur returnees. The conclusion section discusses the theoretical implications of the Chinese experiences for transnationalism, which has been largely examined from the perspective of immigrants’ transnationality with respect to their original society, and calls for a reversed analytical perspective and consequent focus on diaspora returnees’ transnational practice and cultural capital.

Introduction

Since 2000, the number of diasporic Chinese professionals returning to China has increased rapidly. Many of them are students-turned-immigrants who went overseas to pursue higher education after the initiation of the ‘reform and opening-up’ policy in the late 1970s. According to a recent report, more than 4 million students have gone overseas after the late 1970s, and 2.65 million had returned by 2017 (MOE Citation2017). This article focuses specifically on the returned diasporic technopreneurs who constitute an important segment of overseas Chinese professional returnees and a globalising China.

Diasporic technopreneur returnees can be broadly divided into two categories based on their different legal statuses. The first category has obtained foreign citizenship. The second category remains as Chinese nationals, who own permanent residency or studied/worked overseas on a student pass/employment visa before returning to China. Regardless their residential status, the two groups of technopreneur returnees possess the capability to stay overseas, should they choose to do so. Indeed, ninety percent of our informants indicated that it is possible for them to go overseas again if their careers did not develop well in China. It is clear that, for the overseas professional returnees, returning to China does not necessarily mean that they permanently return to the homeland, or purely for patriotic passion. Instead, it is a kind of self-interested strategy, leveraging on their international linkages and their homeland connections to foster new opportunities, although for many it is seen as an ‘adventure’ (Xiang, Yeoh, and Toyota Citation2013). As will be demonstrated in this article, these professional returnees remain distinct from other returnees and maintain a sense of transnational identity. Especially for those who hold foreign citizenship or permanent residency, their children are mostly educated abroad and their families still live overseas, they often plan to go back to the adopted resident country upon retirement. Therefore, this paper considers these technopreneurs as diasporic technopreneur returnees, highlighting their continued sense of international mobility and transnational characteristics.

Most studies on diasporic Chinese technopreneur returnees have been carried out by economists or management scholars. They examine the formation of the returnees’ technopreneurship and their impact on China’s economic development and technological advancement mainly from the perspective of ‘brain circulation’ or human capital theory (Saxenian Citation2002; Liu et al. Citation2010; Wang, Zweig, and Lin Citation2011; Bao et al. Citation2016; Bai, Johanson and Martin Citation2017). Few works concentrate on the institutional environments within which diasporic technopreneur returnees situate, including policies, norms, rules, etc (Scott Citation1995). In fact, the phenomenon of overseas Chinese professionals returning is not only prompted by the rise of China as the world’s second largest economy but also politically driven by the Chinese government’s diaspora engagement policy (Zweig Citation2006; Liu and van Dongen Citation2016; Xiang Citation2016). Nevertheless, how the Chinese state interacts with the returnees and, furthermore, institutionally integrates them into China’s globalisation and domestic development strategies have not yet been adequately addressed.

With respect to the interactions between the state and entrepreneurs, it has been argued that the institutional environment has played a significant part in influencing entrepreneurial motivation and access to resources (Sine, Haveman, and Tolbert Citation2005; Aidis, Estrin, and Mickiewicz Citation2008). Other factors such as the role of government policies and bureaucratic system efficiency, the regulatory framework, the complexity of administrative procedures and the level of corruption are also thought to be important on the evolution of entrepreneurship, (Fogel et al. Citation2006; Bowen and De Clercq Citation2008; Levie and Autio Citation2008; Bao et al. Citation2016). A number of studies have demonstrated the impact of governmental policies in shaping skilled migration from the perspective of the political climate and economic situation (Boucher and Cerna Citation2014; Cerna Citation2014; Green and Hogarth Citation2017). Based on the above theoretical discussions pertaining to the interaction between institutions and entrepreneurship and skilled migrants, this study focuses on institutional features and examines specifically how the Chinese state promotes the return of diasporic Chinese technopreneurs as an economic engine of innovation, and furthermore, how the government affects diaspora returnees’ technopreneurship through a top-down manner by way of direct policy and regulatory initiatives. Moreover, the role of high-skilled migrants in society is not considered only as an economic engine, but as social, cultural and political agents (Bailey and Mulder Citation2017; Grigoleit-Richter Citation2017; Leung Citation2017; Roohi Citation2017). In other studies, the latter aspects are usually neglected. This study contributes to filling in this gap by exploring how the Chinese state institutionally incorporates diasporic technopreneurs into the national agendas and configures their political roles. In the concluding section, through an analysis of the Chinese diaspora experience, this paper provides insights into the concepts of transnationalism, diaspora technopreneurship, and their relationship with the state.

To better understand the dynamic interactions between the Chinese state and diasporic technopreneur returnees, we propose the concept of transnational cultural capital as an analytical tool. This concept is derived from the idea of cultural capital, which constitutes one of the three forms of capital (the other two being economic capital and social capital) in Bourdieu’s theoretical formulations (Bourdieu Citation1986). Since the 1970s, cultural capital has been examined along several dimensions in overseas Chinese business studies, such as Confucian values (Tu Citation1996; Whyte Citation2009) and human capital (Redding Citation1990; Wang and Lo Citation2005; Liu Citation2012). This study approaches the cultural capital of the technopreneurs but from a transnational perspective. What, then, is transnational cultural capital? According to Bourdieu’s cultural capital theory,

Cultural capital can exist in three forms: in the embodied state, i.e., in the form of long-lasting dispositions of the mind and body; in the objectified state, in the form of cultural goods (pictures, books, dictionaries, instruments, machines, etc.), which are the trace or realization of theories or critiques of these theories, problematics, etc.; and in the institutionalized state, a form of objectification which must be set apart because, as will be seen in the case of educational qualifications, it confers entirely original properties on the cultural capital which it is presumed to guarantee. (Bourdieu Citation1986, 243)

Taking inspirations from this definition, we employ Transnational cultural capital to emphasise the dynamics, operations, consequences and limitations of cultural capital in a transnational milieu and its interactions with, the state. More specifically, it refers to the cultural resources possessed by diasporic technopreneurs in both the homeland and hostland, including education, intellect, knowledge, skills, mindset, networks, and other cultural experiences, which are transferable and portable across national boundaries. We argue that transnational cultural capital, as the main engine in a new phase of diasporic entrepreneurial activities in China, is being vigorously promoted by the state as a unique advantage of the technopreneur returnees, differentiating them from domestic technopreneurs and overseas Chinese entrepreneur predecessors in China. Nonetheless, the government selectively judges the technopreneurs’ value and market competiveness by measuring their transnational cultural capital and consequently influences the returnees’ technopreneurship.

In the conversion of cultural capital into economic capital, the institutional context has been a critical issue for discussion. For instance, Bourdieu (Citation1986) highlighted the importance of educational systems in the conversion of cultural capital. He indicated that cultural Capital is convertible, upon certain conditions, into economic capital and may be institutionalised in the form of educational qualifications. By situating technopreneur returnees into the institutional context of the Chinese state and its changing policies, we highlight the importance of political capital, and argue that, at the entrepreneurial start-up stage, political capital as a specie of capital in China can be both an influential facilitator and constraint for the technopreneurs to convert their transnational cultural capital into economic capital. Notably, in Bourdieu’s capital theories, there is no place for ‘political capital’ and his definition of political capital is quite vague. He regards political capital as a variation of social capital (Bourdieu Citation2002, 16). To date, the definition of political capital is mostly concentrated in the field of political studies, and it refers to a type of invisible currency that politicians use for the political purpose (Suellentrop Citation2004; Casey Citation2008; French Citation2011). In this study, political capital in the context of China is embodied in the power possessed by both the Communist Party and the state apparatus, from the central through to the local governments. Through diasporic technopreneur returnees’ acquisition and maintenance of political capital from the government, such as obtaining government financial support, official endorsement on their technology and achievements, and building networks with the officials, the state exerts considerable influences on the returnees’ technopreneurship and the configuration of their political roles.

Methods and data

The data of this empirical study are mainly collected from 66 diasporic Chinese technopreneurs who were selected through group meetings, questionnaires or in-depth interview by face-to-face or telephone. In terms of geographical scope, our fieldwork was conducted in both their foreign resident countries (Singapore, USA and Canada) and in different cities within China, including Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Dongguan, Shanghai, Hangzhou and Beijing. The multi-sited fieldwork in China and overseas is essential to capture the changing dynamics and characteristics of this particular group and contribute to improving our research in diversity and generalities. lists the profile data of 66 informants, including identification, country of settlement, business sectors, highest academic degree, years of overseas working experience, overseas working background, the frequency of participation in talent fairs organised by the Chinese government, the number of official financial funds gained and government-sponsored associations joined.

Table 1. Data on the 66 informants.

We selected our interviewees through two channels. One was through diasporic Chinese entrepreneur communities from the national entrepreneurial parks in China and diasporic Chinese associations or Chinese alumni associations in Singapore, USA and Canada. The entrepreneurial members of these organisations were an important source for us to identify our respondents. The other channel was through snowballing personal contacts we made by participating in social and professional events and via personal networks. In order to minimise interviewee sample bias, we diversified diasporic technopreneurs by business sectors, age, the country of origin, etc. When using the interview materials for this study, their names, age and other personal information will not be revealed to protect our respondents’ anonymity and confidentiality.

Besides questionnaires and the in-depth interviews, this study also uses other mixed methods, including participatory observations and content analysis of archival and media data. In participatory observations, we attended some formal events (e.g. anniversary and festival celebrations, monthly meetings, and awards ceremonies) and informal activities (e.g. private parties and social gatherings). For the content analysis, the data were mainly collected from print or online publications and unpublished materials from related organisations.

Apart from interviewing the entrepreneurs, we also conducted site-visits to their companies in China (and, in a few occasions, overseas), which provided us with an insight into the operational dimension of the conversion of transnational cultural capital into economic capital. We also paid particular attention to interviewing officials in both the central and local governments to understand their rationales and strategies in engaging the diasporic technopreneurs.

The emergence of diasporic technopreneur returnees

Against the backdrop of a returning diasporic Chinese wave, a group of diasporic technopreneur returnees has emerged dynamically in China over the past decade. While no clear-cut statistics exist about the total numbers of diasporic technopreneurs in China, some evidence indicates that there has been a rapid expansion in the quantity of technological enterprises that are helmed by them. For example, in 2001 there were around 3000 diasporic Chinese enterprises in overseas Chinese high-tech venture parks in all of China (Cooperation and Exchange Convention of Overseas Chinese Enterprises in Science & Technology Innovation Citation2001). Two years later, that number had reached 5000 (MOE Citation2004). More recently it has grown dramatically to more than 27,000 (Central Government of PRC Citation2017).

Many factors have contributed to the rapid expansion of diasporic technopreneurs in China. Apart from the global trend of technological innovation and China’s rising economic might, the state plays a crucial role in attracting diasporic Chinese talents from overseas.

During the ongoing transition from a labour-intensive economy to a knowledge-intensive one, since the 2000s the government’s priority in diaspora engagement policy has undergone a significant shift, from attracting foreign capital, to instead luring talents to return (Thunø Citation2001; Liu Citation2011; To Citation2014). In 2014 the government initiated a national-wide campaign called ‘Massive Entrepreneurship and Innovation’ and implemented various policies to encourage the growth of innovative technological-based enterprises.

One of the most important measures is to attract overseas-educated diasporic Chinese professionals back to China to promote innovative industries. As early as 2001, the central government issued a specific official document entitled, ‘Advices on Encouraging Overseas Chinese Scholars to Make Contributions to China in Multiple Ways’, which aims to encourage more overseas Chinese with scientific knowledge and capacities to come back and run high-tech enterprises. Since then, the central and local governments have developed a series of incentive schemes specifically targeted at potential returnees. These schemes offer substantial start-up grants, generous financial benefits, and even free housing. These schemes include the 1000 Talent Programme (central government-level), the Zhujiang Talent Programme (Guangdong, provincial-level), the Peacock Award (Shenzhen; municipality-level), the 530 Talent Programme (Wuxi, municipality-level), and the Hundred Talent Programme (national-level award, but specific only to the Chinese Academy of Sciences), amongst many others. According to a recent report, through the 1000 Talent Programme alone, more than 8000 talents have been imported (Sun Citation2018).

In 2016 Qiu Yuanping, the then Director-General of the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office (OCAO), further launched the programme of Thousands of Overseas Chinese Innovation Campaign. Two points were particularly stressed in the programme: to encourage diasporic professional returnees to engage in innovative entrepreneurial activities, and to develop collaboration with diasporic Chinese professionals and import some leading talents with innovative abilities (Zhao Citation2016).

Apart from above policies, the state has also set up specific government agencies at both the central and local levels for the introduction and management of diasporic Chinese professional and entrepreneurial affairs. Five main government institutions, namely the ‘five overseas Chinese structures’ are all involved in the administration of overseas Chinese events. The five institutions are: the Overseas Chinese Affairs Office (OCAO) of the State Council (OCAO has been merged with the United Front Work Department of CPC Central Committee since March 2018), All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese (ACFROC), China Zhigong Party, Overseas Chinese Affairs Committee of the National People’s Congress (NPC), and The Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan Compatriots and Overseas Chinese Affairs Committee of the CPPCC (Liu and van Dongen Citation2016). These five institutions have all set up specific sub-agencies to manage diasporic Chinese technological economic matters. For example, OCAO and ACFROC, at both the central or local governmental level, have established economy and technology departments that are specifically in charge of diasporic Chinese entrepreneurial and technological affairs.

In practice, the state promotes the recruitment of diasporic talents both domestically and abroad. Domestically, a series of fairs targeted at overseas Chinese professionals have been organised, mainly to attract talents in science and technology, and to build their connections with domestic enterprises in China. These fairs are held regularly every one or two years in various major cities. As the earliest talent fair in China, the Guangzhou Convention of Overseas Chinese Scholars in Science and Technology (GCOCSST) has been held continuously on an annual basis from 1998 to date. By 2017 the number of diasporic Chinese professional attending the convention had reached more than 40,000.

Moreover, the governments actively go abroad to engage with diasporic Chinese talents. As early as in 2009 OCAO organised a team of Chinese officials to hold forums in several major cities in the USA, such as Los Angeles, New York and Boston. These forums were designed to introduce to the local diasporic professionals about China’s economic opportunities, technological developments and preferential policies. The local governmental followed the suit. For instance, the Shenzhen government has held diasporic talent recruitment activities abroad eight times to date, covering North America, Europe and Oceania in geographical scope. These overseas recruitment efforts have proved effective. Several entrepreneurial interviewees told us that one of the important reasons influencing their decision to return to China was the invitation and persuasion from Chinese governments and particularly from officials travelling abroad to promote China as a fertile ground for entrepreneurial innovation.

In addition, the governments have set up overseas contact offices in conjunction with some overseas Chinese professional associations. For instance, by 2017 the Shandong provincial government had established thirty overseas contact offices in fifteen countries such as the UK, France, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. The contact offices are all associated with diasporic Chinese professional organisations that are concerned with biomedicine, information technology, automobile industry, etc. In 2013 and 2014, more than 70 highly skilled professionals were recommended from these contact offices to attend overseas talent fairs held in Shandong province, which led to the realisation of 68 entrepreneurial projects (Shandong Citation2014).

In short, the state has been directly acting as the biggest recruitment agent to create a robust institutional communication platform, managing the importation of diasporic talents and building transnational networks with diasporic Chinese professionals. All these have contributed to the emergence of diasporic Chinese technopreneurs in the homeland.

The making of transnational cultural capital

Compared with other diasporic Chinese entrepreneurs in China, the emerging diasporic technopreneurs have several distinctive characteristics. In terms of educational and social backgrounds, the technopreneurs have both domestic and overseas educational and working experience. They grew up and were well educated in China before moving overseas for further studies after the 1980s, often gaining higher degrees from developed countries. By contrast, other diasporic Chinese entrepreneurs in China, such as first-generation diasporic entrepreneurs who emigrated before 1949, were usually poorly educated, whereas foreign-born Chinese entrepreneurs tend to lack educational and social experience in China. In terms of country of origin, the technopreneurs mainly come from developed countries where economy and technology are highly advanced. Out of our 66 informants, 19 were from western Europe, such as UK, France, Germany and Belgium, 35 were from the US and Canada, and 12 were from the Asia-Pacific, such Japan, Singapore and Australia. Conversely, other diasporic entrepreneurs are traditionally from Southeast Asia where the economy and technology are often lagging developed countries. As a result, in business sectors, the technopreneurs take advantage of their cutting edge technology to engage in high-tech industries, whereas other diasporic entrepreneurs are mostly in traditional manufacturing industries. Technopreneurs usually have a wider ‘global vision’ as their overseas experiences allows them to rapidly follow up on the newest technological developments, and consequently, they tend to have a broader global entrepreneurship vision compared to those entrepreneurs from Southeast Asia.

The strength of transnational cultural capital has become a pivotal factor shaping the interactions between the Chinese state and diasporic technopreneurs. The government has endeavoured to capitalise on the transnational cultural resources wielded by these technopreneurs, and is particularly concerned with the conversion of transnational cultural capital into economic capital, to support the nation’s economic development. Furthermore, the state is seeking to differentiate the technopreneurs into different levels of priority and awards according to potential economic value and market competitiveness of the technopreneurs’ transnational cultural capital. In the interaction with the state, diasporic technopreneurs’ transnational cultural capital is mainly judged and selected on four key aspects decided by the government: educational credentials, level of technological innovation and its relevance to China, overseas working experience, and transnational knowledge network.

In the first place, diasporic technopreneur returnees possess a transnational educational background from China and overseas. Their early education in China ensures their mastery of the language and familiarity with the Chinese culture. Their further study abroad increases their transnational cultural capital. To measure this increase in cultural capital, the government emphasises two criteria from the individuals’ educational background: the academic degree and the university that grants it. The higher the degree they get, and the more prestigious the foreign university they graduate from, then the more transnational cultural capital they have, and the more favour they can extract from the government. By 2014 among 1500 diasporic Chinese professionals recruited through the Conference on Overseas Chinese Pioneering and Developing in China (COCPD Citation2017), 70% were doctoral degree holders. The GCOCSST even raised the requirements for participants in 2004, allowing only master degree holders and above to register for participation. For bachelors, only those graduated from one of the top-listed 200 universities in the world are qualified to register. The attention to academic credentials is clearly reflected in our fieldwork. In 66 informants, 43, or nearly two thirds of the technopreneurs, have overseas doctoral degrees, 11 obtained domestic doctorates but had overseas postdoctoral experience (the postdoctoral study is also regarded as a kind of educational degree in China). In total, the number of doctoral holders takes up more than 80% ().

One interviewee told us: ‘Western higher academic qualification is your essential stepping-stone to gain favor from the government. The higher the qualification you possess, the more advantages you have to acquire resources and support from the state.’ Another interviewee’s experience of failure further explains the importance of a higher degree, albeit from an opposite perspective:

I got my masters degree from Germany. When I tried to apply for financial support from the government for my start-up company, I was told it was difficult. Why? One important reason is that my degree is not high enough. They wanted a doctorate.

The second aspect of transnational cultural capital is that diasporic technopreneurs are at the forefront of international scientific technologies and knowledge in their own field of expertise, yet at the same time they are familiar with related domestic technological developments in China. The government leaders have highlighted this transnational cultural capital as the diasporic technopreneurs’ unique entrepreneurial asset. The holders of international leading technology are more favoured by the governments and usually can get more business start-up subsidies. Most interviewees expressed that the more prestigious the academic institute or company they studied/worked in, the more competitive they are to get government support in entrepreneurial activities. Therefore, how strong the returnees’ transnational culture capital is, has become a critical measure for the government to select talents and influence their technopreneurship. During transnational technology transfer, patents are a critical issue. To avoid intellectual property disputes, government officials usually have intellectual property agreements with the technopreneurs before the latter secure government financial support. Our interviews disclosed two common patterns concerning industrial intellectual property: the technopreneurs have their own patented technology in China and/or overseas; and the technopreneurs often incorporate foreign owners of intellectual property as partners in their companies, effectively co-opting overseas technologies.

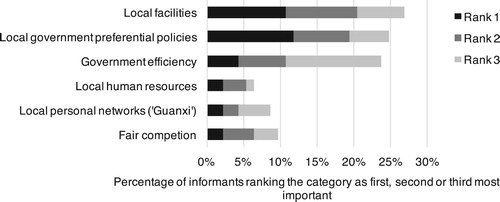

As a form of social capital, guanxi (an omnipresent social network in Chinese society) has been widely discussed in relation to diasporic Chinese entrepreneurial activities in China (Yang Citation1994; Liu Citation2012). Is guanxi, which is often based upon primordial ties such as locality and family connections, as important as cultural capital to the technopreneurs? Our research found that the location where the technopreneurs settle down is mostly not their hometown, which is in stark contrast to the traditional diasporic Chinese entrepreneurs who prefer to invest in their ancestral hometown or the locations where they have intensive social networks. This suggests guanxi, at least as traditionally viewed, as emanating from home or ancestral backgrounds, may not be critical. Indeed, in the Shenzhen Nanshan Overseas Chinese High-Tech Venture Park, 80% of the technopreneurs have no direct geographical-relationship with Shenzhen (which, of course, is a migrant city itself). In a survey, we evaluate the ranking of factors that affect business start-up, local facilities, government preferential policy and government efficiency were all ranked ahead of guanxi. () Some interviewees even expressed that they did not have wide domestic social networks since they studied or worked overseas for a long time. It further highlights that the key capital that the diasporic technopreneurs rely on to set up business in China is their transnational cultural capital such as educational credentials, technologies and innovation instead of their social capital.

Thirdly, diasporic technopreneurs’ transnational cultural capital is manifested by their overseas working experience, which is highly valued. About 70% of participants in the 17th GCOCSST in 2015 had more than 5 years of overseas working experience. (Yangcheng Evening News, December 18, 2015) Overseas working experience was always considered as a key favourable criterion by the government when selecting participants in overseas Chinese talent fairs held in China. This preference is keenly aware of by overseas Chinese experts. One interviewee told us,

You would become more popular and competitive with several years overseas working experience, whether to the Chinese governments or in the China market. So, I found a job first once I graduated and came back to China a few years later.

Among 66 informants, 59 have overseas working experience. In terms of their professional backgrounds, 29 worked in academic institutes, 15 in enterprises, 12 in both (). In other words, there are more technopreneur returnees who have a strong academic background than those who have direct business experience. This fact, on the one hand, demonstrates the government’s heavy promotion on the translation of technology and knowledge into economy, whilst on the other hand, it shows the government’s emphasis on the importance of academic technological background for technopreneurs’ competitiveness. Many interviewees told us that academic background is more critical when they apply for official entrepreneurial funds or grants. Their long-term overseas working experience, especially from world reputable research laboratories or institutes, demonstrates to the government that the technology they apply to industries is globally advanced and competitive. However, practical business experience is also important to run an enterprise. Of the 27 informants who have industrial experience overseas ranging from 1 to 25 years, one informant emphasised the value of his one-year working experience in an American company:

In my company there are no bureaucracy and politics that are common in Chinese companies. Everyone is equal and respected, although they take different level of positions. Everyone can present his own idea in group meetings. My company culture is made of three C’s: Care, Creativity, and Cooperation. This comes from my overseas working experience.

Those technopreneurs who lack business experience usually incorporate experienced businessmen into their core team, to make up for their weakness. The teamwork in the synthesis of technology and business enhances their capacities in gaining governmental support. The transition from a researcher to a technopreneur indeed takes time. One informant said, ‘It took me several years to learn from my business partners, and my own experience of failing in running a business. It is a painful experience. I am still learning now.’

Lastly, diasporic technopreneurs have built transnational knowledge networks based on their long-term overseas study or working experience, which has become an important component of their transnational cultural capital and is highly valued by the government. These transnational networks are built with their foreign countries and are manifested as their continuous contacts or close relationships with their overseas PhD supervisors or classmates, or former colleagues, some of whom are world-famous scientists or technological experts (such as Nobel prize winners). The diasporic technopreneurs utilise these transnational cultural networks to incorporate internationally leading scientists into their entrepreneurial team, which significantly improves their competitiveness in application for Chinese government grants. Most of our interviewee’s supported this observation. ‘If you want to be more competitive in applying for funds or grants from the government, your core work-team members are better to be international. It gives you a lot of advantages.’ One informant explained it by his own experience:

In my company the core technological team is made of 6 people. They come from Hong Kong, Denmark, Germany and the US. Some are overseas Chinese and some are pure foreigners. Four of them are my former colleagues in the US. They are all reputable scientists in this field, They do not necessarily live in China. We usually have an online meeting once a month. Last year I got a big award from the Chinese central government. It is closely related with my strong transnational team.

To sum up, in its interaction with the technopreneur returnees, the Chinese state values the latter’s four key attributes, namely, transnational educational credentials, technological know-how, overseas working experience, and transnational knowledge networks. These attributes, in turn, constitute the main components of the technopreneurs’ transnational cultural capital. The government judges the technopreneurs’ value or competitiveness by formulating and implementing its own regulations to create corridors to those who fit the criteria and facilitating their innovation while erecting barriers to others who are perceived to be not fitting the criteria.

Conversion of transnational cultural capital

In the conversion of transnational cultural capital into economic value, technopreneurship is a key factor. To stimulate technopreneurship from diasporic Chinese professionals, the state takes various measures to mobilise this transnational cultural capital.

The state has created various business platforms to facilitate the conversion of transnational cultural capital, for instance, Conference on Overseas Chinese Pioneering and Developing in China (COCPD) and Overseas Chinese Innovative and Entrepreneurial Project Competition. Most of these fairs are held regularly each year. The COCPD, as the oldest and biggest entrepreneurial start-up platform for diasporic technopreneurs, is organised and sponsored by three vertically-structured governmental institutions, including OCAO, the Hubei provincial government and the Wuhan municipal government. It was launched in 2001, and it has been held sixteen times so far. By 2017 the number of overseas Chinese professional participants reached 12,000. More than 2000 overseas professionals have returned and 2500 high-technological projects have been imported (COCPD Citation2017). Our investigation shows that nearly 81% of our informants have taken part in these fairs, among of them 15% once a year and 49% more than twice a year.

Apart from business platforms, the state builds many high-tech industrial incubators, which diasporic Chinese technopreneurs take advantage of and come to dominate. So far there are 347 pilot parks throughout China, encompassing more than 79,000 diasporic professional returnees and 27,000 enterprises. (People’s Daily [Overseas Edition], April 12, 2017) Based in these parks, diasporic technopreneurs can get financial support and benefits, like business start-up funds, subsidised interest for mortgage, venue rental allowance, etc. About 81% of our informants had positive opinions on these parks and considered them ‘useful’ or ‘moderately useful’ for start-up technological enterprises. One technopreneur said: ‘The government gave us some benefits on the office rental. It saved us 400,000 CNY every year. Now it seems not a lot. But it really helped us a lot especially at start-up period when our budget was tight.’

To encourage and stimulate diasporic professional returnees’ technopreneurship, the governments provide financial support to the returnees. The data collected from Southern University of Science of Technology in Shenzhen shows that in five years scholars in the university have received 400 million CNY from the Shenzhen municipal government and 100 million CNY from the Guangdong provincial government for their entrepreneurial and innovative activities. Our investigation shows that 80% of the informants got funding support from different governmental levels (). The government funding ranges from several tens of thousands to tens of millions. One technopreneur told us that in the previous five years he had received more than 40 million CNY of funding support from both the central and local governments.

The state is also directly involved as a stakeholder. One interviewee said:

The local government gave me a big help in setting up the high-technological industry. As the government was optimistic about my project, a state-owned company became one of the five main investors. Several years later, my enterprise and the state-owned company reached an agreement to establish another joint venture company.

The state offers various preferential policies and convenient services for diasporic technopreneur returnees in establishing enterprises in China, including business start-up guidance and training, industry and commerce registration, generous tax allowances and exemptions, and visa issue. These benefits were appreciated by the technopreneurs, one of whom told us:

When I came back from overseas, I worked in a governmental research institute for one year. After that I began to run my own business. In the beginning, the research institute offered me free use of equipment and venue. It also provided me with several technicians for assistance. These timely measures helped me overcome some difficulties in the initial stage.

As early as 2005, OCAO has been coordinating with its local bureaus to stage the Overseas Chinese Professional Returnees Business Start-up Entrepreneurship Seminar and by 2016 this event had been held 29 times in different cities of China. Every time there are dozens of diasporic Chinese professional attendees. The seminar usually lasts about five days and its programme covers four parts, including the current economic situation of China, the latest related policies from OCAO, business start-up guidance, on-the-spot investigations, and interface meeting with local enterprises. Shanghai has held this event eight times. The number of the participants reached 770, and the ratio of projects successfully funded and landing in Shanghai through this event has reached more than 13% (Xu Citation2016).

To facilitate the conversion of transnational cultural capital into economic capital, the state creates a strong institutional environment to stimulate diasporic professional returnees’ technopreneurship. At the same time, the returnees accumulate political capital through their entrepreneurial activities by winning official financial support and building networks with the government officials.

Incorporating diasporic technopreneurs into the national agenda

The state has made great efforts to integrate diasporic technopreneurs into the national agenda to maximise their political value. With the increasing number of diasporic returnees, the government has created institutional apparatuses to cultivate links with them. Over the past few years, a number of diasporic Chinese returnee associations have been established throughout China at both the central and local governmental levels. lists samples of these associations. These organisations have become an official channel for the governments to build and maintain connections with diasporic professional returnees. Among our informants, 71% have taken part in at least one government-linked association. These organisations are usually well structured, having their own regulations and undertaking regular events and management committees. For instance, the management committee of Entrepreneur Alliance of the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese consists of 2 executive directors, 36 vice directors, 132 entrepreneurial members, secretariat, along with a committee of consultants (Citation2016). These organisations usually have hundreds of individual members. The Fujian Overseas Chinese Professional Association has 237 committee members while the Guangzhou New Overseas Chinese Association has 230 members. Diasporic technopreneur returnees are usually recruited as key players in these organisations. Take for example the Guangzhou New Overseas Chinese Association: diasporic technopreneurs constitute the mainstay of its members; its executive president is a technopreneur and technopreneurs account for one third of the 80-strong committee.

Table 2. Samples of established diasporic Chinese returnee associations.

The state strengthens the national identity of diasporic technopreneurs by praising their contribution to the motherland and awarding them with various honours and prizes from the governments. To enhance their sense of belonging to China, the governments have organised seminars and exhibitions that showcase the technopreneurs’ successful stories and achievements. In addition, the state has initiated some honors, awards and prizes specifically targeted at diasporic Chinese technopreneurs. In 2009, the OCAO launched the award Key Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurial Team. It is awarded every two years, and by 2015, 230 diasporic technopreneur teams had been awarded with recognition and prizes. The ACFROC holds a similar event every two years to recognise and praise new diasporic Chinese innovative and entrepreneurial achievements. By 2016 the ACFROC event has been held 6 times and 830 diasporic Chinese returnees have been awarded ‘innovative talent’ award, 363 with the ‘innovative achievements’ award, 310 with the ‘innovative team’ award and 86 with the ‘innovative enterprises’ award (Zhu Citation2016).

Apart from the above-mentioned awards by the central government, local governments have also offered honors and awards diasporic technopreneurs. Between 2012 and 2014, the Shandong provincial government had honoured 77 local diasporic technopreneurs. The Guangzhou government between 2008 and 2011 awarded 58 outstanding diasporic Chinese entrepreneurs, 37 of them are technopreneurs, accounting for nearly 70% of the total awardees (Guangzhou Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese Citation2014).

The government has promoted diasporic professional returnees to act as an important national strategic human capital. In 2015 Xi Jinping specifically stated that diasporic Chinese scholars and professionals are ‘an important part of our talent pool’, and the state continues to emphasise diasporic Chinese as an important group that the government must unite with. As the most influential and largest diasporic-Chinese-professionals-orientated organisation in China, the Western Returned Scholars Associations (WRSA), which was established in 1913, is led by the secretariat of the CPC Central Committee. The WRSA has more than 20 sub-associations, 80,000 individual members, 30 group members throughout China and has established close networks with more than 100 diasporic Chinese professional organisations overseas. Diasporic technopreneurs (including returnees and those still overseas) are an important part of the targeted members who are encompassed in two affiliated organisations: Entrepreneurs’ Friendship Association and Association of Commerce. In 2016 the central government issued an official document, emphasising three roles that the WRSA can play, namely, to develop a Chinese talent pool, to work as a think tank, and to take part in civil diplomacy (WRSA Citation2017). The governments have also actively engaged in technopreneurs for official or semi-official positions, such as ACFROC distinguished specialist, OCAO professional committee members and ACFROC congress representatives. Eleven of the 66 informants have taken up such official titles.

In summary, the central and local governments have taken various approaches to institutionally incorporate diasporic technopreneurs into the political system and maximise the political value of the technopreneur returnees, who also expand their political capital by joining governmental organisational networks or taking up official positions.

Mechanisms of domesticating transnational cultural capital

Under the Chinese governments’ proactive diaspora engagement policy, the number of diasporic Chinese technological enterprises increased dramatically. However, the ratio of successful diasporic technopreneurs is not high. Less than 30% of diasporic technopreneur start-up enterprises in some venture parks of the Pearl River Delta region (one of the main areas where the diasporic technopreneur returnees settled) could survive beyond 3.5 years. (Yangcheng Evening News, April 15, 2016) Although it is not untypical for entrepreneurial businesses to fail, the interacting mechanism and its characteristics may contribute to this widespread business failure. This mechanism has three characteristics.

First, it is a two-way interactive relationship between the state and diasporic technopreneurs. The governments take a dominant role and become the main creator of technopreneurship activities. All the related preferential policies, diaspora talent schemes and fairs, financial support and newly established diasporic-Chinese-professionals-orientated organisations are substantially driven by the state in a top-down manner. As a result, the state becomes the most active player in this arena. At the same time, diasporic technopreneurs play an active role to engage with the governments in order to maximise their own interest. This interaction between the state and diasporic technopreneur returnees has been driven by two forces: One is the governments’ pursuit for performance and achievements, it forms a kind of ‘governmental economy’ or ‘ritual economy’ that denotes deep intertwining logic between the economic, the ritualistic and the political (Xiang Citation2011). The other force is that many diasporic technopreneur returnees are more inclined to rely on the government, rather than angel investors or venture capitalists. Under the governmental support schemes they can obtain legitimacy to the new ventures and even build contact with the governmental officials, which is a key benefit as the state takes a dominant role in all economic affairs in the country. As we observed in the GCOCSST, most participating diasporic professionals preferred not to deal with small and medium private enterprises, but instead preferred working directly with the government or with state-owned-enterprises.

Second, the state judges transnational cultural capital by setting up the qualification bar for the diasporic talents. Participants at diasporic talents venture fairs in China are essentially chosen by the government, which sets its own preferences and requirements, such as focusing on specific technological fields and a strong emphasis on participants’ academic credentials and overseas working experience. In so doing, the state ultimately decides who could be a talent or not. This artificial manipulation of the pool of returnees by the state using restrictive measures might marginalise professional returnees that do not easily fit into the ‘desirable’ categories.

Those who do fit into the talent criteria were selected by the government and subsequently acquired political capital. However, these talent programmes and policies have not yet led to the emergence of a strong technological economy driven by the diasporic technopreneurs. Our investigation in the Guangdong Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs Association (GOCEA) shed light on this issue. Guangdong province is one of the major areas where overseas Chinese enterprises are located. As one of the most influential overseas Chinese entrepreneur associations in Guangdong, the GOCEA was established in 2007 and has become an important agency for the local government to obtain information about overseas Chinese enterprises in the province. The GOCEA has 429 entrepreneurial members, and a directorial committee consisting of leaders drawn from 169 medium-sized and larger enterprises. However, only 11 of those 169 companies are high-technology companies (Guangdong Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs Association Citation2013), suggesting that overseas Chinese traditional industries remain dominant in large and medium enterprises, in both quantity and in strength. This exposes the deficiencies in the current talent programmes, particularly the rigid management of diasporic talents and the big influence exerted by the government on the returnees’ technopreneurship.

Third, institutional problems exist in the interaction between the state and diasporic technopreneurs. The governments have set up various platforms and preferential policies for diasporic technopreneurs returnees. However, it is difficult to get these platforms to work effectively and to put the policies into practice. More than half of our informants expressed that they did not know much about these governmental preferential policies when they were abroad. And during their interactions with government officials after coming back, they face two big problems: government work efficiency and governments’ judgment on entrepreneurial projects. Many interviewees complained that although there is a stated preferential policy, part or all of these policies may never be implemented. One diasporic technopreneur interviewee highlighted his experience in registering a company:

As I hold a foreign passport, it is complex for me to get temporary residential card, business license, employment permit and other requested documents. I have been out of China for 20 years, I am not so familiar with government agencies. The governments have supportive policies for diasporic Chinese professionals, but in reality it takes time to carry out.

Another common complaint from our informants was that the government is not in the best position to appropriately judge the value of technological projects due to the lack of specialist knowledge. And considering the risk of high-technological industries at the initial stage and the achievements in their officials’ career, most government officials prefer to only invest in start-ups that have already been supported by other means, e.g. venture capital, rather than providing initial funding. Corruption is also a problem--in some cities, giving a red packet (‘kick-back’) to some officials could facilitate the obtaining of government funds. One informant complained:

The project I brought back to China is very mature in terms of technology, and it has a big potential market. But when I applied to the government for start-up business funds, my project was not given attention at all, because I did not offer red packet to relevant officials.

The above discussion shows the mechanism and characteristics of the state in domesticating transnational cultural capital possessed by diasporic technopreneur returnees. The government takes a dominant role in resources allocation to influence diasporic technopreneurship, and diasporic technopreneurs make efforts to engage with the governments to obtain political capital in order to facilitate the conversion of transnational cultural capital into economic capital. While the state’s active role might be instrumental in attracting overseas Chinese technopreneurs back to China, the top-down approach is not conducive for technological innovation and business startup.

Conclusion

Against the backdrop of China’s transition from a labour-intensive to an innovation-driven economy, the state has vigorously promoted diasporic technopreneur returnees as a new dynamic force in the country’s economic development. Although the emergence of diasporic technopreneur returnees in China is concomitant with global forces emerging from accelerating globalisation, it is nonetheless closely related to the Chinese governments dedicated efforts in importing diasporic talents. There are several points argued in this study.

Firstly, the emergence of diasporic Chinese technopreneurs in China is deeply embedded in the institutional environments of China’s political economy. The government has exerted considerable influence, from the import of diasporic Chinese professionals to the conversion of their transnational cultural capital into economic capital, and again to the incorporation of the technopreneurs into the national agenda. The various policies that the state deploys towards these professional migrants distinguish the role of the state in transnational governance and the emerging of the networked state (Liu Citation2018).

Secondly, in the conversion of transnational cultural capital, the political authority and power the state exhibited highlights both the existence and importance of political capital in the globalisation of China. In the relatively immature venture environment of China, the acquisition and maintenance of political capital by technopreneur returnees becomes a facilitator or constraint for them. Whether diasporic technopreneurs can obtain political capital and how much political capital they can gain, are determined by whether they are qualified, as set by the governments criteria, and whether they obey the rules of the game. As a consequence, some technopreneurs are mainstreamed and some are marginalised. And the mainstreamed technopreneurs are furthermore strategically integrated into the political system.

Last but not least, this study also brings out a new emerging mode of immigrant transnationalism in a theoretical discourse. Transnationalism was initially defined as ‘the process by which immigrants build social fields that link together their country of origin and their country of settlement’ (Basch, Schiller, and Blanc Citation1994, 1). In this original formulation, transnationalism was proposed from the perspective of immigrants’ host countries and emphasised immigrant’s transnational networks with their homeland. In the current literature, transnationalism has been largely examined from the perspective of immigrants’ transnationality with respect to their original society. However, with the increasing number of Chinese diaspora that are experiencing sizeable returns to the homeland, the diaspora returnees keep transnational contact with their previous settlement society. This, in turn, requires a reversed analytical perspective and consequent focus on diaspora returnees’ transnational practice with respect to their own foreign residential countries, thus enhancing what we call ‘dual embeddedness’ of immigrant entrepreneurs (Ren and Liu Citation2015). This study shows that the technopreneur returnees have built transnational knowledge (and cultural) networks with their foreign resident countries through their overseas study and working experience. And thanks to the economic and political value of the transnational practices, this reversed diasporas’ transnational cultural network is furthermore pushed and strengthened by the state.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Hong Liu http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3328-8429

Additional information

Funding

References

- ACFROC (All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese). 2016. “The Establishment of Entrepreneur Alliance of the All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese in Beijing.” November 1. http://www.chinaql.org/c/2016-11-01/511793.shtml.

- Aidis, R., S. Estrin, and T. Mickiewicz. 2008. “Entrepreneurship, Institutions and the Level of Development.” Small Business Economics 31 (3): 219–234. doi: 10.1007/s11187-008-9135-9

- Bai, Wensong, Martin Johanson, and Oscar Martín Martín. 2017. “Knowledge and Internationalization of Returnee Entrepreneurial Firms.” International Business Review 26 (4): 652–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.12.006

- Bailey, Ajay, and Clara H. Mulder. 2017. “Highly Skilled Migration Between the Global North and South: Gender, Life Courses and Institutions.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2689–2703. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314594.

- Bao, Yue, Qi Miao, Ying Liu, and Daniel Garst. 2016. “Human Capital, Perceived Domestic Institutional Quality and Entrepreneurship Among Highly Skilled Chinese Returnees.” Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 21 (1), doi:10.1142/S1084946716500023.

- Basch, linda, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Szanton Blanc. 1994. Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States. Langhorne: Gordon and Breach.

- Boucher, A., and L. Cerna. 2014. “Current Policy Trends in Skilled Immigration Policy.” International Migration 52 (3): 21–25. doi: 10.1111/imig.12152

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardarson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 2002. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Trans. Richard Nice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bowen, P. H., and D. De Clercq. 2008. “Institutional Context and the Allocation of Entrepreneurial Effort.” Journal of International Business Studies 39 (4): 747–767. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400343

- Casey, Kimberly. 2008. “Defining Political Capital: A Reconsideration of Bourdieu’s Interconvertibility Theory.” Paper Presented at the 16th Annual Illinois State University Conference for Students of Political Science.

- Central Government of PRC. 2017. “The Solutions from the Department of Human and Society Studies to the Returned Overseas Students on the ‘Six Difficulties’ of Entrepreneurial Innovation.” http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2017-04/12/content_5185103.htm.

- Cerna, L. 2014. “Attracting High-Skilled Immigrants: Policies in Comparative Perspective.” International Migration 52 (3): 69–84. doi: 10.1111/imig.12158

- Conference on Overseas Chinese Pioneering and Developing in China (COCPD). 2017. “ Introduction.” http://www.hch.org.cn/index.php/index-show-tid-2.html.

- Cooperation and Exchange Convention of Overseas Chinese Enterprises in Science&Technology Innovation. 2001. “Opportunity, Entrepreneurship, Cooperation and Development.” http://www.chinaqw.com/node2/node116/node119/ym/lhf.htm.

- Fogel, K., A. Hawk, R. Morck, and B. Yeung. 2006. “Institutional Obstacles to Entrepreneurship.” In The Oxford Handbook of Entrepreneurship, edited by M. Casson, B. Yeung, A. Basu, and N. Wadeson, 540–579. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- French, Richard. 2011. “Political Capital.” Representation 47 (2): 215–230. doi: 10.1080/00344893.2011.581086

- Green, A., and T. Hogarth. 2017. “Attracting the Best Talent in the Context of Migration Policy Changes: The Case of the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2806–2824. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314609.

- Grigoleit-Richter, G. 2017. “Highly-Skilled and Highly Mobile? Examining Gendered and Ethnicised Labour Market Conditions for Migrant Women in STEM-Professions in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2738–2755. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314597.

- Guangdong Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs Association. 2013. Special Issue of Guangdong Overseas Chinese Entrepreneurs Association.

- Guangzhou Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese. 2014. New Guangzhou, New Strength of Overseas Chinese: Review of Work on New Diasporas in Guangzhou.

- Leung, M. W. H. 2017. “Social Mobility via Academic Mobility: Reconfigurations in Class and Gender Identities Among Asian Scholars in the Global North.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2704–2719. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314595.

- Levie, J., and E. Autio. 2008. “A Theoretical Grounding and Test of GEM Model.” Small Business Economics 31 (2): 235–263. doi: 10.1007/s11187-008-9136-8

- Liu, Hong. 2011. “An Emerging China and Diasporic Chinese: Historicity, The State, and International Relations.” Journal of Contemporary China 20 (71): 856–876.

- Liu, Hong. 2012. “Beyond a Revisionist Turn: Network, State, and the Changing Dynamics of Diasporic Chinese Entrepreneurship.” China: An International Journal 10 (3): 20–41.

- Liu, Hong. 2018. “Transnational Asia and Regional Networks: Toward a New Political Economy of East Asia.” East Asian Community Review 1: 33–47. doi: 10.1057/s42215-018-0003-7

- Liu, X., J. Lu, I. Filatotchev, T. Buck, and M. Wright. 2010. “Returnee Entrepreneurs, Knowledge Spillovers and Innovation in High-Tech Firms in Emerging Economies.” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (7): 1183–1197. doi: 10.1057/jibs.2009.50

- Liu, Hong, and Els van Dongen. 2016. “China’s Diaspora Policies as a New Mode of Transnational Governance.” Journal of Contemporary China 25 (102): 805–821. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2016.1184894

- MOE (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China). 2004. “The Fourth Press Conference of the Ministry of Education in 2004: The Situation of Studying Abroad in the Year 2003.” http://old.moe.gov.cn//publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/moe_2271/200408/2577.html.

- MOE (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China). 2017. “The Statistics of Overseas Students in 2016.” http://www.moe.edu.cn/jyb_xwfb/xw_fbh/moe_2069/xwfbh_2017n/xwfb_170301/170301_sjtj/201703/t20170301_297676.html.

- Redding, G. 1990. The Spirit of Chinese Capitalism. New York: de Gruyter.

- Ren, Na, and Hong Liu. 2015. “Traversing Between Local and Transnational: Dual Embeddedness of New Chinese Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Singapore.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 24 (3): 298–326. doi: 10.1177/0117196815594719

- Roohi, S. 2017. “Caste, Kinship and the Realization of ‘American Dream’: High Skilled Telugu Migrants in the U.S.A.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (16): 2756–2770. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1314598.

- Saxenian, A. 2002. Local and Global Networks of Immigrant Professionals in Silicon Valley. San Francisco: Public Policy Institute of California.

- Scott, R. 1995. Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Shandong, O. C. A. O. 2014. “Strengthening the Construction of Overseas Contact Offices and Improve the Effectiveness of Overseas Chinese Talent Recruitment.” Overseas Chinese Affairs Studies 4. http://qwgzyj.gqb.gov.cn/jyjl/179/2506.shtml.

- Sine, W. D., H. A. Haveman, and P. S. Tolbert. 2005. “Risky Business? Entrepreneurship in the New Independent-Power Sector.” Administrative Science Quarterly 50 (2): 200–232. doi: 10.2189/asqu.2005.50.2.200

- Suellentrop, Chris. 2004. “America’s New Political Capital.” Slate, November 30, 2004.

- Sun, Rui. 2018. “Significant Progress Made in the Introduction of Overseas Talents Since 18th CPC National Congress.” One Thousand Talent Plan. http://www.1000plan.org/qrjh/article/76678.

- Thunø, Mette. 2001. “Reaching Out and Incorporating Chinese Overseas: The Trans-Territorial Scope of the PRC by the End of the 20th Century.” The China Quarterly 168: 910–929. doi: 10.1017/S0009443901000535

- To, James Jiann Hua. 2014. Qiaowu: Extra-Territorial Policies for the Overseas Chinese. Leiden: Brill Academic.

- Tu, Wei-Ming, ed. 1996. Confucian Traditions in East Asia Modernity: Moral Education and Economic Culture in Japan and the Four Mini-Dragons. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wang, Shuguang, and Lucia Lo. 2005. “Chinese Immigrants in Canada: Their Changing Composition and Economic Performance.” International Migration 43 (3): 35–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2435.2005.00325.x

- Wang, Huiyao, David Zweig, and Xiaohua Lin. 2011. “Returnee Entrepreneurs: Impact on China’s Globalization Process.” Journal of Contemporary China 20 (70): 413–431. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2011.565174

- Whyte, Martin King. 2009. “Paradoxes of China’s Economic Boom.” Annual Review of Sociology 35: 371–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115905

- WRSA (Western Returned Scholars Association). 2017. “The Document of ‘Opinions on Strengthening the Construction of Chinese Overseas-Educated Scholars Associations’ Issued by the Central Office of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China.” August 29. http://www.wrsa.net/content_39103591.htm.

- Xiang, Biao. 2011. “A Ritual Economy of ‘Talent’: China and Overseas Chinese Professionals.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (5): 821–838. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2011.559721

- Xiang, Biao. 2016. Emigration Trends and Policies in China: Movement of the Wealthy and Highly Skilled. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

- Xiang, Biao, Brenda S.A. Yeoh, and Mika Toyota, eds. 2013. Return: Nationalizing Transnational Mobility in Asia. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Xu, Qian. 2016. “The 24th Overseas Chinese Professionals Returnees Entrepreneurship Workshops Held in Shanghai.” Qiaowangzhongguo, June 27. http://www.chinaqw.com/jjkj/2016/06-27/93265.shtml.

- Yang, M. 1994. Gifts, Favors, and Banquets: The Art of Social Relationships in China. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Zhao, Liang. 2016. “An Analysis of Thousands of Overseas Chinese Innovation Campaign.” Overseas Chinese Affairs Office of The State Council. http://qwgzyj.gqb.gov.cn/yjytt/187/2735.shtml.

- Zhu, Jichai. 2016. “The Sixth Award of Overseas Chinese Contribution in China Was Presented by All-China Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese.” The Central Government of PRC. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2016-09/01/content_5104283.htm.

- Zweig, David. 2006. “Competing for Talent: China’s Strategies to Reverse the Brain Drain.” International Labour Review 145 (1–2): 65–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1564-913X.2006.tb00010.x