ABSTRACT

Compassion-evoking and widely circulated news images seem capable of affecting public opinion and change history. A case in point is the picture of the drowned toddler Alan Kurdi, who died while trying to escape to Europe with his family in September 2015. We theorise how these types of photos affect public opinion. By relying on panel data with sequentially embedded survey experiments conducted in the aftermath of the picture’s publication and while large numbers of refugees were coming to Europe, we demonstrate that the image of Alan Kurdi had context-varying effects on policy preferences. Initially, the upsetting photo of the toddler increased support for liberal refugee policies across ideological divides. However, when individuals had the time to think about policy implications, they started processing even this highly upsetting picture through their ideology. Consequently, our results indicate that compassion-evoking images shift meaning over time.

Introduction

During the so-called European refugee crisis in early September 2015, the three-year old Alan Kurdi drowned while trying to reach Europe with his family (Griggs Citation2015). The image of the toddler’s body, dressed in a red t-shirt and blue shorts, lying face down in the sand on a Turkish beach, spread rapidly through social media and global news outlets (Butler, Toksabay, and Balmer Citation2015; Vis and Goriunova Citation2015). In the aftermath of this tragic event, public opinion became more positive toward generous refugee policies (BBC/ComRes Citation2015; Slovic et al. Citation2017) and more than one million refugees applied for asylum in Germany, Sweden and other European countries (Eurostat Citation2016). The outpouring of support for refugees was brief, however, as multiple European countries shifted to stricter policies on refugees not long after the death of Kurdi.

In this paper, we evaluate the claim that compassion-evoking and widely circulated news photos like the one picturing Alan Kurdi affect public opinion during the tumultuous time when they first appear. We theorise that these pictures affect policy attitudes, but that these effects are conditioned by time and by the ideological orientations that people rely on to make sense of the world. In the immediate time-period following their publication, individuals increase their support for policies aimed at helping the suffering group regardless of their ideological predispositions. Before long, however, the same people, exposed to the same pictures, reach different policy positions depending on their ideological orientations. In other words, once people have had time to contextualise the upsetting pictures and consider policy implications, the effects of the images change.

We test our theoretically derived predictions in the context of the publication of the picture of Alan Kurdi. Since the picture appeals to core human principles (‘never again’) and the deep-seated moral emotion of compassion (Haidt Citation2003), we would expect individuals to have universally increased their support for generous refugee policies when they saw the picture in September 2015. However, a month later, in October, we would expect ideological orientation to have a stronger effect on people’s policy reactions to the picture. At this point, ideology-based resistance towards liberal governmental policies would take precedence among right-leaning individuals, and support for generous refugee policies is reduced. In contrast, since liberal refugee policies are compatible with a left-leaning ideology, with government help to disadvantaged groups, individuals on the left would not need to modulate their reaction to the image and can let a compassionate impulse have free rein.

In order to examine these issues – to our knowledge, we are the first to study these processes as they occur – we have collected panel survey data with two embedded, sequential and randomised experiments that were executed as events evolved in Sweden during the fall of 2015. Our first experiment was conducted shortly after the photo of Alan Kurdi was published on September 2, 2015, and our second experiment was done a month later, in October, when the initial public outcry had begun to subside. Preferences on refugee policies were measured four times: before the publication in May 2015, in connection with the two experiments, and in December 2015. By surveying the same individuals as events were unfolding, and by combining consecutive survey experiments with pre-treatment measures of variables, we are able to overcome the obstacles of drawing causal inferences faced by traditional surveys while maintaining high external validity.

The 2015 increase of refugees to Europe

The same year as Alan Kurdi tried to cross the Mediterranean Sea with his family, around one million refugees and migrants reached Europe. Although the numbers had increased substantially over the previous years, there was a manifold rise in 2015 compared to 2014. A majority came from countries plagued by war, conflict and persecution such as Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq.

This period of a dramatically increased number of refugees to Europe is commonly referred to as the European refugee crisis (or the European migrant crisis). The crisis terminology itself is contentious, however, as observers and scholars note that by calling it a crisis, the situation is being framed to serve certain political interests (Carastathis, Spathopoulou, and Tsilimpounidi Citation2018; Dines, Montagna, and Vacchelli Citation2018). This discussion is important, yet it is beyond the scope of this article to examine it. Instead, what matters most here is that during this period of upheaval, Alan Kurdi became a powerful symbol. Next, we turn to the theoretical reasons of why his fate seems to have had such wide-ranging and changing effects.

Visuals and public opinion

A large body of communication research shows that images can be influential. In comparison with text, people pay more attention to images (Garcia and Stark Citation1991), understand the meaning of images faster (Barry Citation1997) and are able to better recall the content of images (Nelson, Reed, and Walling Citation1976; Newhagen and Reeves Citation1992). Similarly, audio-visuals are more influential than audio alone (Druckman Citation2003). Overall, there is growing recognition that visuals play a particularly meaningful role in multiple fields of research (Joffe Citation2008; Margolis and Pauwels Citation2011).

There is a line of research on how refugees are visually depicted. For example, by relying on a content analysis of pictures in two influential Australian newspapers, Bleiker et al. (Citation2013) show that asylum-seekers are generally shown in groups of people, often on boats, rather than as single individuals with distinguishable facial features. The authors argue that such visuals can contribute to the dehumanisation of refugees. In a broader exploration of how refugees are visually represented, Wright (Citation2002) suggests that images are often inspired by common Christian motifs. In particular, typical pictures of refugees evoke Christian iconography like the Madonna and Child.

The events surrounding the death of Alan Kurdi have been studied by several scholars. They conclude that the image of Kurdi spread quickly and widely in social media and traditional news media (Vis and Goriunova Citation2015). As to whether or not the image changed attitudes or behaviour, there is no conclusive prior evidence. On the one hand, the publication of the picture coincided with a marked increase in online searches for refugees and in donations aimed at helping them (Slovic et al. Citation2017). The power of the image to increase helping behaviour is also supported by a study of young people (Prøitz Citation2018). Others doubt the image’s transformative power, however. For example, a study on tweets before and after the publication of the image suggests that it merely reinforced how actors previously had positioned themselves on refugees (Bozdag and Smets Citation2017).

While prior research has not established a causal link, it is likely that the image of Alan Kurdi did in fact influence public opinion. It focused attention on an identified, single victim, which tends to generate action and charitable contributions. In contrast, portrayals of anonymous groups of victims generally impart weaker impressions (Jenni and Loewenstein Citation1997; Kogut and Ritov Citation2005). In addition, the fact that Alan Kurdi was a child rather than an adult may have amplified the public’s reaction, as images of children tend to generate stronger reactions (Burt and Strongman Citation2005).

In sum, the picture of Alan Kurdi had several of the essential ingredients that normally evoke compassion, an automatically activated moral emotion that compels people to help or alleviate the suffering of others (Haidt Citation2003). This proposition is stated as the overwhelming image hypothesis: Seeing the picture of the drowned toddler led to an initial increase in support for liberal refugee policies across ideological divides.

The conditions of ideological processing

However, after a brief period of uniformly increased support among the public, we posit that individuals eventually derive differential policy conclusions from these visuals. The rationale behind this argument is that a strong political predisposition usually motivates people to seek out information that supports their prior beliefs and avoid opposing arguments, spend more effort in arguing against incongruent information and more readily accept congruent information, and find supporting arguments of prior beliefs more persuasive than opposing arguments. These tendencies can lead to further attitudinal entrenchment where, if given the same information, people polarise even more (Lord, Ross, and Lepper Citation1979; Kunda Citation1990; Nickerson Citation1998; Taber and Lodge Citation2006).

Left-right ideology is among the most important political predispositions. It has strong effects on of a range of political attitudes (Jost Citation2006; Treier and Hillygus Citation2009; Erikson and Tedin Citation2014), including attitudes towards immigrants and refugees, where right-leaning individuals tend to be more negative towards generous policies than individuals on the left (Ben-Nun Bloom, Arikan, and Courtemanche Citation2015). In fact, in some countries, such as in Sweden, ideology dominates as an explanatory variable on a vast array of policy preferences (Granberg and Holmberg Citation1988; Oscarsson and Holmberg Citation2016).

Our theoretical argument is that, due to the powerful nature of the picture of Alan Kurdi, there was a temporary break in the sway of ideology in September 2015, which consequently increased support for a more liberal refugee policy, even among individuals on the right. This was a natural response since compassion exists among all groups, regardless of ideological beliefs. Normally, however, a right-leaning ideology tends to win out over compassion on governmental policy preferences (Haidt Citation2012; Feldman et al. Citation2016). Subsequently, when right-leaning individuals have had time to think about the implications of a liberal refugee policy and how it relates to their ideology, we propose that they counteracted their initial empathetic impulse and, when faced with the picture again, drew more on their ideology to inform preferences on refugee policies. After all, when people think about their own thoughts, so called meta-cognitions, they are more influenced by their priors than they otherwise would be (Petty et al. Citation2009), which is what individuals had the chance to do in October 2015 when we conducted our second experiment. It is possible that viewing an image of this type at a later point could even suppress support among right-leaning individuals because of tendencies towards motivated reasoning.

Since left-leaning individuals do not need to resolve an inner struggle between compassion and ideological orientations, their compassion generally increases support for social welfare policies (Haidt Citation2012; Feldman et al. Citation2016). Consequently, we propose that left-leaning individuals who have had time to think about the implications of their increased support, strongly supported a liberal refugee policy when they were once again faced with the picture of Kurdi.

We summarise our argument as the image polarisation hypothesis: Upon seeing the picture of Alan Kurdi, we expect an increase in polarisation on refugee policy preferences to occur along ideological lines in October compared to September.

Study details, experimental design and measures

The study is set in Sweden, the European country that together with Hungary received the most asylum applications per capita during the large increase of refugees in 2015 (Eurostat Citation2016).Footnote1 To better understand the situation we are studying, it is vital to know that by October 2015, authorities throughout Sweden expressed distress over the unprecedented influx of asylum-seekers, and, according to Swedish citizens, migration was, by far, the most important political issue (Esaiasson, Martinsson, and Sohlberg Citation2016). Thus, at the time of the second experiment, people were likely already motivated to think hard about refugee policies and their own positions.

We rely on data from the Swedish Citizen Panel, a large and diverse web-panel with adult Swedes, administered by the Laboratory of Opinion Research at the University of Gothenburg (The Laboratory of Opinion Research Citation2017). The majority of the web panel participants are opt-in recruits, yet around 20% have been recruited from random samples of the Swedish population. At the September experiment, the sample consisted of 36% females and the mean age was 51 (SD = 15). Sixty-eight per cent had three years of college or more. Respondents were not compensated for their participation.

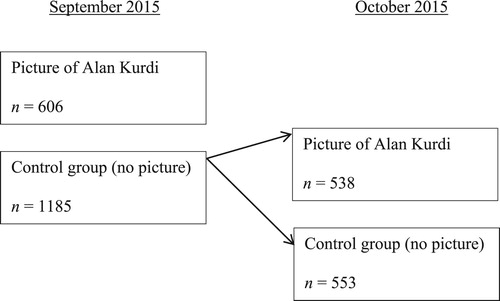

Our design includes multiple steps. In May 2015, we polled refugee policy preferences of 32 517 panel participants. On September 5, shortly after the publication of the picture, we randomly assigned a sub-sample of the panellists to one of two conditions. One group was given a picture of Alan Kurdi (n = 606) and the other was not given a picture (n = 1 185). Directly following the experiment, we measured attitudes on refugee policies. A month afterward, in early October 2015, we assigned individuals who had been part of the control group in September to either the (same) picture of Alan Kurdi (n = 538) or no picture (n = 553). As before, we measured refugee policy preferences after the experiment. In December, we asked about policy preferences again, yet this time without any experimental treatment. and show the experimental design and the image used in the Alan Kurdi Picture Conditions, respectively.

To take advantage of the benefits of the experimental method, randomisation to conditions needs to be successful. Fortunately, there is no evidence that randomisation was anything but successful in the present study since there are no statistically significant differences on key variables. Please see the appendix for additional information. Moreover, researchers had no ability to influence which condition participants were assigned to since this was handled automatically by the randomisation feature in Qualtrics, the research software used to create the study.

Respondents’ preferences on refugee policies were measured on a five-point scale, which has been recoded as ranging from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating more support for a liberal refugee policy. The question asked about a proposal to reduce the level of refugees, ‘What is your opinion on the following political proposal? Accept fewer refugees in Sweden.’ Response options were the following: ‘Very good proposal,’ ‘Somewhat good proposal,’ ‘Neither good nor bad proposal,’ ‘Somewhat bad proposal,’ and ‘Very bad proposal.’ For example, an individual who answered that this was a very bad proposal would be coded as most in favour of a liberal policy and coded as 1. Left-right ideology is an average of two equally worded self-placement questions, asked first when participants joined the panel and then at wave 1, both times on 11-point scales. The question asked, ‘There is sometimes talk about placing political opinions on a left-right scale. Where would you place yourself on such a left-right scale?’ The end-points on the scale and the middle option were labelled and the other options numbered. The measure (alpha = 0.97) has been recoded to range from 0 to 1 with higher values associated with a more right-leaning ideological placement. Individuals randomly assigned to a condition that showed the picture of Alan Kurdi have been coded as 1 whereas those assigned to the control condition of no image have been coded as 0. Information on the question wordings, variable names and coding are included as a codebook in the supplementary material.

Results

Refugee policy preferences over time in the control condition

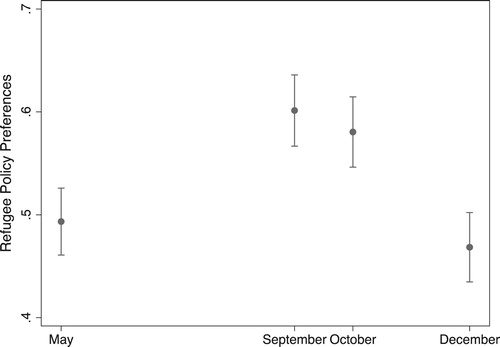

shows the change over time in refugee policy preferences among individuals who did not receive any experimental treatments, i.e. the panel subset of the sample that only answered questions about their support for liberal refugee policies. Consistent with the overwhelming image hypothesis, public opinion towards generous refugee policies increased remarkably following the publication of the picture. In September 2015, the mean level of support increased to 0.60, up from 0.49 in May 2015 (t = 11.94, p < 0.0001). The surge in support is noteworthy because it took place in spite of the political issue having been salient for a long period of time (Ohlsson, Oscarsson, and Solevid Citation2016), a feature that is often associated with attitude strength (Krosnick et al. Citation1993).

Figure 3. Description of refugee policy preferences over time.

Note: The graph shows change over time, May 2015 to December 2015, with 95% confidence intervals for untreated portion of the sample (n = 553). The point estimates are mean values.

However, the change did not last. By October, attitudes had begun to decrease to lower levels and were somewhat more negative than they had been in September (M = 0.58 vs. M = 0.60, t = 2.40, p = 0.02) although still much higher than in May (M = 0.58 vs. M = 0.49, t = 9.06, p < 0.0001). In December, support had returned to the same level as it was in May. In fact, it had even further decreased (M = 0.47 vs. M = 0.49, t = 2.30, p < 0.02). To summarise, the change following Kurdi’s death endured for at least a month, but no longer than three months, and it did not move public opinion to a new, more permanent level of support.

Although the results from the panel data are in line with the overwhelming image hypothesis, change over time is not sufficient evidence of a causal connection. The publication of the picture coincided with multiple events that could have potentially moved public opinion in the same direction. Therefore, we turn to our embedded experiments.

Establishing a causal connection

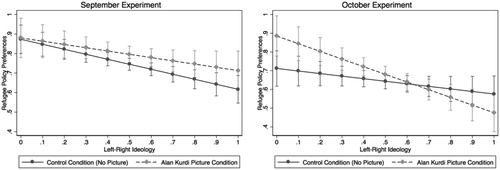

The first experiment was conducted when focus on the tragic event was at its peak. Since almost all participants had seen the picture previously, the treatment was foremost a priming manipulation where they were reminded of the picture that was presumably highly salient.Footnote2 In spite of the picture having received strong and recent attention in the media, (model 1) shows that treated individuals became more positive in their refugee policy preferences compared with those who saw no picture, i.e. the control condition, b = 0.052, SE = 0.024, p = 0.032. This result also supports the overwhelming image hypothesis, and with the advantage of the experimental method in mind, it is a conclusion we can draw with greater certainty. Moreover, there is no evidence of a heterogeneous effect of ideology in September, as is indicated by the lack of an interaction effect between ideology and the experimental conditions shown in , model 2 (b = 0.089, SE = 0.110, p = 0.420). Including pre-treatment covariates that are highly predictive of the dependent variable increases efficiency (Mutz and Pemantle Citation2016). Therefore, we have added refugee policy preferences in May 2015 to the models.

Table 1. Alan Kurdi, ideology and time: preferences on refugee policies.

Changing political impact of upsetting pictures

Turning then to the image polarisation hypothesis on a time-varying interaction between ideology and reactions to the picture, we expect that that the effect of ideology in response to viewing the picture of Alan Kurdi was stronger in October than in September. Given the coding of the variables, we expect a negative sign on the interaction effect between ideology and the experimental treatment in October.

Our results, shown in and (model 2 and model 4), are in line with this expectation. Model 4 (depicted on the right panel of ) shows that the effect of ideology is stronger among participants assigned to the Alan Kurdi Picture Condition compared to the control (b = −0.273, SE = 0.126, p = 0.030). That is, left-leaning individuals who were reminded of Alan Kurdi became more supportive of refugee policies than those who were not; in contrast, among right-leaning individuals there was a tendency towards a backlash effect of seeing the picture, as they reduced their support on refugee policies compared to right-leaning individuals in the control condition.Footnote3 The appendix includes additional information on this interaction effect.

Figure 4. Effect of Alan Kurdi picture conditions by ideology in September and October on refugee policy preferences.

As further evidence that the two interaction effects are different, rather than saying that one interaction is significant while the other is not, we posit a null hypothesis of similar interaction effects in September and October. This is rejected, Χ2 = 4.72, p = 0.030, indicating that they are dissimilar. In other words, the image polarisation hypothesis on the differential effect of the image of Alan Kurdi is supported.

Conclusion and discussion

Can powerful news images like the one of Alan Kurdi affect public opinion and have political ramifications? Both our panel data and our experimental data indicate that the picture of the drowned toddler made public opinion more welcoming of refugees in general. The uniform increase in support of liberal refugee policies was brief, however. A month after his death, when faced with the picture of Alan Kurdi again, people viewed the image increasingly through an ideological lens. Our interpretation is that pictures that evoke the moral emotion of compassion can initially unmoor the effect of ideological preferences and trigger public opinion change, but that even highly upsetting pictures find themselves relatively quickly drawn into political conflicts and processed through familiar political predispositions.

This study focused on the impact of viewing a picture of the vulnerable and innocent, which belongs to a specific class of pictures that are associated with the moral emotion of compassion. Two other photos of the same class are those of the Vietnamese girl running naked down the road after being wounded in a napalm attack and the Buddhist monk setting himself on fire, pictures that allegedly contributed to swing public opinion in the West against a brutal and destructive war.Footnote4 In general, this class of photos highlights the suffering of the vulnerable, and calls for action in support of the victimised group (Burt and Strongman Citation2005). Now, it is plausible that different types of powerful images can evoke other moral emotions that briefly dominate ideology. For example, images of terrorists committing a large attack could temporarily lead to anger (a so-called other-condemning moral emotion) causing punitiveness to take precedence over ideology, which could lead to a more aggressive response than individuals would normally promote based solely on their ideology. This is just one of many processes that we need to study in order to gain a clearer understanding of contemporary politics.

One implication of our results is that the iconic images associated with different eras – the dead of Antietam, Emmett Till and his mother, prisoners at Abu Ghraib – have shifted meaning over time. This points to the difficulties of recreating responses to historical events. In our case, we believe that the differential effects of our successive experiments were based on two factors: the image contained key elements that made it particularly upsetting, and it was published during a period when Sweden was receiving a very large number of refugees. While aware that our study design with its panel components, rapid launch and sequential experiments is demanding for both researchers and participants, we hope it can serve as a blueprint when the goal is to understand reactions towards visually compelling events.

As for possible limitations of our study, there are primarily two that should be addressed. The first concerns compassion. We theorised that compassion can overwhelm ideologically-driven motivations in the immediate aftermath of the publication of the picture of Alan Kurdi, but that compassion is tempered among right-leaning individuals once they are able to process more fully what it means to be driven by compassion. Ideally, we would have had a direct measure of participants’ levels of compassion after they viewed the picture of Alan Kurdi but before they answered the question on their refugee policy position. We did not include the question because we were concerned that such a measure would unwittingly reveal the purpose of the study and therefore influence responses on the policy question, our key dependent measure.Footnote5 To delve deeper into the details of how compassion interacts with ideology, we encourage further research.

The second limitation relates to the public’s reliance on ideology. One perspective argues that since so few people hold meaningful ideological beliefs, it is a relatively useless concept (Converse Citation1964). In response to this account, scholars maintain that ideology is a useful concept, albeit difficult to measure (Achen Citation1975; Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder Citation2008). Part of the reason it seems like people do not have coherent ideological beliefs is that they have different considerations on policy issues (Zaller and Feldman Citation1992) and that the conception of ideology as one-dimensional is an oversimplification for many individuals (Feldman and Johnston Citation2014). Here, it is important to note that left-right ideological placement in Sweden correlates strongly with policy positions on the economic dimension. For example, the correlation between our left-right ideology index and a two-item index comprised of attitudes on governmental taxes and the size of the welfare state is 0.77. Since ideological self-placement is systematically correlated with ideological policy positions, it suggests that self-placement indeed reflects a belief system.

Supplementary_Material.docx

Download MS Word (46.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 While Hungary received a large share initially, many of these individuals eventually moved on to other countries such as Germany and Sweden.

2 Towards the end of the survey when we asked respondents if they had seen the picture of Alan Kurdi before taking part in the study, 95% reported that they had seen the picture previously.

3 The image polarisation hypothesis can only be tested with experimental data since we are expecting effects based on renewed exposure.

4 Both pictures are listed as “100 Images That Changed the World” (Time Citation2017).

5 There are potential workarounds to this issue, but neither solves the basic problem. First, the compassion measure could have been embedded in a battery of other questions that serve as decoys. However, this would be questionable since there is a risk that such a battery would attenuate the effect of the experimental treatment on the policy measure. Second, the compassion measure could have been asked after the policy question. Yet, this is not a good option because the policy question could have influenced the compassion question, either by priming considerations that go into answering a question on the policy or by offsetting the effect of the treatment because of the time it took to answer the policy question.

References

- Achen, Christopher H. 1975. “Mass Political Attitudes and the Survey Response.” The American Political Science Review 69 (4): 1218–31. doi: 10.2307/1955282.

- Ansolabehere, Stephen, Jonathan Rodden, and James M. Snyder. 2008. “The Strength of Issues: Using Multiple Measures to Gauge Preference Stability, Ideological Constraint, and Issue Voting.” American Political Science Review 102 (2): 215–32. doi:10.1017/S0003055408080210.

- Barry, A. M. 1997. Visual Intelligence: Perception, Image, and Manipulation in Visual Communication. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- BBC/ComRes. 2015. “BBC Newsnight Migrant Crisis Survey.

- Ben-Nun Bloom, Pazit, Gizem Arikan, and Marie Courtemanche. 2015. “Religious Social Identity, Religious Belief, and Anti-Immigration Sentiment.” American Political Science Review 109 (2): 203–21. doi:10.1017/S0003055415000143.

- Bleiker, Roland, David Campbell, Emma Hutchison, and Xzarina Nicholson. 2013. “The Visual Dehumanisation of Refugees.” Australian Journal of Political Science 48 (4): 398–416. doi:10.1080/10361146.2013.840769.

- Bozdag, Cigdem, and Kevin Smets. 2017. “Understanding the Images of Alan Kurdi With “Small Data”: A Qualitative, Comparative Analysis of Tweets About Refugees in Turkey and Flanders (Belgium).” International Journal of Communication 11: 4046–69.

- Burt, Christopher DB, and Karl Strongman. 2005. “Use of Images in Charity Advertising: Improving Donations and Compliance Rates.” International Journal of Organisational Behaviour 8 (8): 571–80.

- Butler, Daren, Ece Toksabay, and Crispian Balmer. 2015. Troubling Image of Drowned Boy Captivates, Horrifies.” Reuters. Accessed October 27, 2017. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-europe-migrants-turkey-idUSKCN0R20IJ20150902.

- Carastathis, Anna, Aila Spathopoulou, and Myrto Tsilimpounidi. 2018. “Crisis, What Crisis? Immigrants, Refugees, and Invisible Struggles.” Refuge 34 (1): 29–38.

- Converse, Philip E. 1964. “The Nature of Belief Systems in Mass Publics.” In Ideology and Discontent, edited by David E. Apter, 206–261. New York: Free Press.

- Dines, Nick, Nicola Montagna, and Elena Vacchelli. 2018. “Beyond Crisis Talk: Interrogating Migration and Crises in Europe.” Sociology 52 (3): 439–47. doi:10.1177/0038038518767372.

- Druckman, James N. 2003. “The Power of Television Images: The First Kennedy-Nixon Debate Revisited.” Journal of Politics 65 (2): 559–71. doi:10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00015.

- Erikson, Robert S., and Kent L. Tedin. 2014. American Public Opinion: Its Origins, Content and Impact. 9 ed. New York: Routledge.

- Esaiasson, Peter, Johan Martinsson, and Jacob Sohlberg. 2016. “Flyktingkrisen och medborgarnas förtroende för samhällets institutioner – en forskarrapport.” Karlstad: MSB rapport 1035. https://www.msb.se/RibData/Filer/pdf/28209.pdf.

- Eurostat. 2016. “Record Number of Over 1.2 Million First Time Asylum Seekers Registered in 2015.” Eurostat.

- Feldman, Stanley, Leonie Huddy, Julie Wronski, and Patrick Lown. 2016. "Compassionate Policy Support: The Interplay of Empathy and Ideology.” APSA Annual Meeting & Exhibition, Philadelphia, PA.

- Feldman, Stanley, and Christopher Johnston. 2014. “Understanding the Determinants of Political Ideology: Implications of Structural Complexity.” Political Psychology 35 (3): 337–58. doi:10.1111/pops.12055.

- Garcia, M. R., and P. Stark. 1991. Eyes in the News. St. Petersburg, FL: Poynter Institute.

- Granberg, Donald, and Sören Holmberg. 1988. The Political System Matters: Social Psychology and Voting Behavior in Sweden and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Griggs, Brandon. 2015. “Photographer Describes ‘Scream’ of Migrant Boy's ‘Silent Body’.” CNN. Accessed October 28, 2017. http://edition.cnn.com/2015/09/03/world/dead-migrant-boy-beach-photographer-nilufer-demir/.

- Haidt, Jonathan. 2003. “The Moral Emotions.” In Handbook of Affective Sciences, edited by R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer and H. H. Goldsmith, 852-70. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Jenni, Karen, and George Loewenstein. 1997. “Explaining the Identifiable Victim Effect.” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 14 (3): 235–57. doi:10.1023/a:1007740225484.

- Joffe, Hélène. 2008. “The Power of Visual Material: Persuasion, Emotion and Identification.” Diogenes 55 (1): 84–93. doi:10.1177/0392192107087919.

- Jost, John T. 2006. “The end of the end of Ideology.” American Psychologist 61 (7): 651–70. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.61.7.651

- Kogut, Tehila, and Ilana Ritov. 2005. “The “Identified Victim” Effect: An Identified Group, or Just a Single Individual?” Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 18 (3): 157–67. doi:10.1002/bdm.492.

- Krosnick, Jon A., David S. Boninger, Yao C. Chuang, Matthew K. Berent, and Catherine G. Carnot. 1993. “Attitude Strength: One Construct or Many Related Constructs?” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology: Attitudes and Social Cognition 65 (6): 1132–51. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1132.

- Kunda, Ziva. 1990. “The Case for Motivated Reasoning.” Psychological Bulletin 108 (3): 480–98. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480.

- The Laboratory of Opinion Research. 2017. “About the Citizen Panel.” University of Gothenburg. Accessed October 27, 2017. http://lore.gu.se/surveys/citizen/aboutcp.

- Lord, Charles G., Lee Ross, and Mark R. Lepper. 1979. “Biased Assimilation and Attitude Polarization: The Effects of Prior Theories on Subsequently Considered Evidence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 37 (11): 2098–109. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.37.11.2098.

- Margolis, Eric, and Luc Pauwels. 2011. The Sage Handbook of Visual Research Methods. London: Sage.

- Mutz, Diana C., and Robin Pemantle. 2016. “Standards for Experimental Research: Encouraging a Better Understanding of Experimental Methods.” Journal of Experimental Political Science 2 (2): 192–215. doi:10.1017/XPS.2015.4.

- Nelson, Douglas L., Valerie S. Reed, and John R. Walling. 1976. “Pictorial Superiority Effect.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory 2 (5): 523–8. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.2.5.523.

- Newhagen, John E., and Byron Reeves. 1992. “The Evening's Bad News: Effects of Compelling Negative Television News Images on Memory.” Journal of Communication 42 (2): 25–41. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1992.tb00776.x.

- Nickerson, Raymond S. 1998. “Confirmation Bias: A Ubiquitous Phenomenon in Many Guises.” Review of General Psychology 2 (2): 175–220. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.2.2.175.

- Ohlsson, Jonas, Henrik Oscarsson, and Maria Solevid. 2016. “Ekvilibrium.” In Ekvilibrium, edited by Jonas Ohlsson, Henrik Oscarsson, and Maria Solevid, 11–44. Gothenburg: Göteborgs Universitet/SOM-Institutet.

- Oscarsson, Henrik, and Sören Holmberg. 2016. Svenska Väljare. Stockholm: Wolters Kluwer.

- Petty, Richard E, Pablo Briñol, Chris Loersch, and Michael J McCaslin. 2009. “The Need for Cognition.” In Handbook of Individual Differences in Social Behavior, edited by Mark R. Leary, and Rick H. Hoyle, 318–29. New York: Guilford Press.

- Prøitz, Lin. 2018. “Visual Social Media and Affectivity: The Impact of the Image of Alan Kurdi and Young People’s Response to the Refugee Crisis in Oslo and Sheffield.” Information, Communication & Society 21 (4): 548–63. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2017.1290129.

- Slovic, Paul, Daniel Västfjäll, Arvid Erlandsson, and Robin Gregory. 2017. “Iconic Photographs and the ebb and Flow of Empathic Response to Humanitarian Disasters.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (4): 640–4. doi:10.1073/pnas.1613977114.

- Taber, Charles S., and Milton Lodge. 2006. “Motivated Skepticism in the Evaluation of Political Beliefs.” American Journal of Political Science 50 (3): 755–69. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00214.x.

- Time. 2017. “The Most Influential Images of All Time.” Accessed October 27, 2017. http://100photos.time.com/.

- Treier, Shawn, and D. S. Hillygus. 2009. “The Nature of Political Ideology in the Contemporary Electorate.” Public Opinion Quarterly 73 (4): 679–703. doi:10.1093/poq/nfp067.

- Vis, F., and O. Goriunova. 2015. “The Iconic Image on Social Media: A Rapid Research Response to the Death of Aylan Kurdi*.” Visual Social Media Lab.

- Wright, Terence. 2002. “Moving Images: The Media Representation of Refugees.” Visual Studies 17 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1080/1472586022000005053.

- Zaller, John, and Stanley Feldman. 1992. “A Simple Theory of the Survey Response: Answering Questions Versus Revealing Preferences.” American Journal of Political Science 36 (3): 579–616. doi:10.2307/2111583.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Randomisation check

Table A1. The outcome of experimental randomisation.

Appendix 2. Further details on the interaction effect in October

The interaction effect in October between left-right ideology and the experimental treatment of seeing the picture of Alan Kurdi is statistically significant overall. complements (model 4) in that it shows at what points on the ideological scale that the effect of the treatment is statistically significant. For example, a moderately left-leaning individual (.2) increased support on refugee policies by 0.119 when he or she was assigned to the Alan Kurdi Picture Condition compared to if he or she was not (p = 0.016). Meanwhile, a highly right-leaning individual (1 on the scale) decreased support (−0.100) when exposed to the picture, although this effect is not statistically significant by conventional standards (p = 0.141).