ABSTRACT

The rise across Europe of political parties espousing an ethnic conception of the nation, explicitly opposed to immigrants and minorities, has brought into stark relief the politics of identity. Exploiting multiple identity questions in a large, nationally representative UK survey, this paper investigates the drivers of ethnic and political identity and the extent to which they are similar. It does so for both the ethnic majority and ethnic minorities. Locating our analysis within social identity theory, we consider the role of observed characteristics, including party affiliation, the experience of harassment, and political context in shaping ethnic and political identities. We also show that there are unobserved factors jointly implicated in individuals’ political and ethnic identities, which we interpret as providing suggestive evidence of more general political mobilisation of ethnicity. Although individual characteristics have largely expected associations with identity, we find that the local share of UKIP/BNP voters heightens ethnic but not political identity among both majority and minority populations. By contrast, harassment and discrimination shapes minorities’ political but not ethnic identity. Contrary to expectations, both political and ethnic identities are stronger among second-generation compared to immigrant minorities.

Introduction

The rise across Europe of political parties espousing an ethnic conception of the nation, explicitly opposed to the immigrants and minorities and their claims to belonging, has brought into stark relief the politics of identity (Pehrson, Vignoles, and Brown Citation2009; Hopkins Citation2010; Huddy Citation2001). In parallel, concerns with the failures of multiculturalism and integration have problematised the extent to which minorities identify with their ethnic ‘origins’ rather than with national values (Koopmans Citation2013; Cameron Citation2011; Reeskens and Wright Citation2013). Theory and existing literature posits that such currents might be expected to influence the majority population’s social identities (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986; Deaux et al. Citation1995), as they respond politically to the explicit mobilisation of narratives of ethnic identity (Kenny Citation2014). Note that by political identity, we refer to the salience of politics to an individual’s sense of self, rather than partisanship. These contemporary developments would also be expected to shape the ethnic and political identity of minorities, as the salience of minority status is heightened and politicised by such narratives.

Extant research has demonstrated the importance of political orientation and ethno-national identity for majority group behaviours, such as party membership or voting ‘Leave’ in the recent UK referendum (e.g. Henderson et al. Citation2017). Political engagement has also been linked to ethnicity and to minority group experiences (Sanders et al. Citation2014). There is also some evidence that those with particular political partisanship have stronger ethnic identities (Nandi and Platt Citation2015). However, existing analysis has not so far identified whether the drivers of stronger political identity are also the drivers of stronger ethnic identity. That is, whether ethnic and political identities are co-determined. This is our contribution.

We locate our analysis in social identity theory that highlights the potential for multiple identities to co-exist and for specific identities to be triggered in varied social contexts (Abrams Citation2010; Jenkins Citation2014; Tajfel Citation1974; Tajfel and Turner Citation1986; Abrams and Hogg Citation1999). Rather than addressing whether stronger political identity leads to stronger ethnic identity (or vice versa), we pose the prior question of what factors are shaping these identities. While we know an increasing amount about the correlates of ethnic identity and the factors associated with political partisanship or behaviours, we know much less about characteristics and context shaping people’s sense of the relevance of politics to their identity (‘political identity’). Nor do we know whether the factors are similar across the two identities. Our initial aim is therefore exploratory. We examine whether those individual and local-contextual factors associated with an increased ethnic sensitivity also stimulate enhanced political identity, across majority and minority populations.

Many of the key triggers of ethnic and political identity that are theoretically relevant and have been postulated as underpinning the relationship between the two, such as political mobilisation by political parties and politicised discourses around ethnicity, cannot be directly observed or measured quantitatively. That is, we cannot, by definition, distinguish the influence of common discourses and traits. We argue that, theoretically, if these are important then they will be revealed through unobserved factors influencing both ethnic and political identity concurrently. We, therefore, evaluate whether common unobserved factors also contribute to the strength of individuals’ ethnic and political identity, net of the observed characteristics.

The importance of our study lies in the insights it offers on the formation of ethnic and political identity. In the context of multiple claims relating to identities, ethno-national orientations and the politics of immigration, we are able to test propositions stemming from these claims. In the highly charged atmosphere that has marked political discussions of minority status and the re-emergence of populist nationalism with a strong ethnic undertow, the question of the interconnectedness between political and ethnic identities of a country’s minority and majority populations is timely. More generally, as both local and national elections in many European countries and beyond are increasingly being fought on the grounds of ethno-national identities and the othering of minorities and migrants, it is critical to ascertain the success of these strategies.

We address these questions exploiting a set of multiple-domain identity questions in a large, nationally representative multi-topic panel survey, Understanding Society (Knies Citation2017). We estimate seemingly unrelated regression (SUR) models to enable us to identify individual-level factors associated with political and ethnic identity and also unobserved factors influencing both identities not captured by, and not working through, this extensive suite of individual-level measures. We estimate separate models for majorities and minorities. We focus on the minority–majority distinction since our argument is based on the dichotomy between majority vs. minority status itself.

Our contribution is three-fold. First, drawing on indications from existing literature we derive expected associations between individual characteristics and ethnic and political identity and explore how far these are evidenced in our data. We show that individual and contextual factors are associated with ethnic and political identity in largely expected directions. We therefore amplify existing understanding of the formation of identities.

Second, we are able to show that common unobserved factors are implicated in both ethnic and political identities. By purging our identity measures of idiosyncratic variations and controlling for a range of relevant individual-level characteristics, we can more plausibly argue that common drivers of ethnic and political identities represent the broader political mobilisation of ethnicity. We further argue that if political identity is enhanced through mobilisation of ethnic identity (or vice versa) we would expect these common unobserved drivers to be stronger among majorities compared to minorities since there is greater scope for triggering ethnic identity among the typically normalised majority. We also expect this more among majority group members more to the right of the political spectrum, who are more likely to have endorsed ethnic notions of nation. Since we find these patterns, we argue they represent prima facie empirical evidence for political mobilisation of ethnicity.

Third, focusing on minorities we examine whether minorities’ political and ethnic identities are sensitive to experiences of harassment. Given visible minority status – and hence ethnic ascription and identification – can be expected to be salient even without personal experience of harassment, we anticipate negative experiences may play out in heightened political rather than ethnic identity. Finding this relationship, we suggest that the problematisation of minority ethnic identification in political discourse (e.g. Cameron Citation2011; DHCLG Citation2018) may miss the ways in which alienation or mobilisation is actually expressed.

Next, we elaborate on the theoretical framework and literature and outline the expectations we derive from it. In the subsequent sections, we describe the data and methods, our main results, and discuss the implications of our findings and conclude.

Background and theory

Social identities

Our starting point is social identity theory (Abrams Citation2010; Jenkins Citation2014; Tajfel Citation1974; Tajfel and Turner Citation1986; Abrams and Hogg Citation1999), which posits that individuals hold personal and social identities that provide points of differentiation from other individuals or from other social groups (Oaks, Turner and Haslam Citation1991). Social identities are formed and expressed under specific historical, cultural and ideological conditions, and ‘matter’ for social relations (Tajfel Citation1974), for individual development (Phinney Citation1992), and for national cohesion and coherence (Reeskens and Wright Citation2013). Social identity theory posits that a specific identification presupposes categorisation of others – which can have implications for their experiences, resources and, status (Jenkins Citation2014).

Deaux et al. (Citation1995) have argued that social identity theory is most applicable to ethnic as well as religious and political identity. However, studies of minority ethnic identity often continue to imply that ethnic identity is the sole relevant aspect of identity, and neglect other forms of identification, such as political, or for that matter, gender, class or occupational identity (Nandi and Platt Citation2012). Conversely, studies of the ethnic majority are only gradually recognising the relevance of their ethnic identity (Kenny Citation2014; Henderson et al. Citation2017). As a result, despite the emphasis in social identity theory on multiple identities (Abrams Citation2010; Jenkins Citation2014) and the strong theoretical basis for the co-evolution of ethnic and political identities, discussed below, we lack empirical evidence on other identity domains and their relationship to ethnic identity. Given that identification is an expression of ‘interest’ (Jenkins Citation2014) that has implications for others through processes of inclusion and exclusion (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986), the relationship between political identity (with its implication for claims to the public sphere) and ethnic identity (with the potential for polarisation) merits consideration.

Minority ethnic and political identities

In the context of increasing minority ethnic populations in Europe, there have been vivid debates on multiculturalism, acculturation and assimilation both within the academic sphere and the political arena (e.g. Koopmans Citation2013; Modood Citation2007; Brubaker Citation2001).

The political discourse has linked failures of ‘integration’ to minority ethnic groups’ retention of their ethnic identity and failure to engage with national identity (e.g. Cameron Citation2011; DHCLG Citation2018). As a consequence, extensive academic analyses have aimed to assess such claims. This literature has explored the extent, correlates and consequences of ethnic and national identification of ethnic minorities from both immigrant and second generations (Constant, Gataullina, and Zimmermann Citation2009; Manning and Roy Citation2010; Platt Citation2014; Van Heelsum and Koomen Citation2016; Platt Citation2014; Nandi and Platt Citation2015; Nguyen and Benet-Martínez Citation2013; Diehl and Schnell Citation2006; Karlsen and Nazroo Citation2013). This literature has demonstrated that ethnic identities tend to decline across generations, though still remaining strong into the second generation, while national identity increases. It has also illustrated a range of characteristics associated with ethnic identity, including age, gender, educational qualifications, occupation, region of residence, and political affiliation.

There is substantial evidence that minority identities are associated with forms of political engagement or behaviours. For example, Martinovic and Verkuyten (Citation2014) suggest that dual ethnic-national identity reduces political engagement while both Simon and Grabow (Citation2010) and Fischer-Neumann (Citation2014) find the opposite. Sanders et al. (Citation2014) show that both ethnic embeddedness and majority acculturation are associated with greater political engagement among minorities. Naturalisation, which can be understood as affective investment in destination countries has also been linked, though not consistently, to political engagement of minorities (Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Pietrantuono Citation2015; Street Citation2017).

The literature has also drawn attention to the role of political discourse and local context in shaping (dual) identity expression (Ahmad and Evergeti Citation2010; Nandi and Platt Citation2016; Diehl, Fischer-Neumann, and Mühlau Citation2016). Simon and Grabow (Citation2010) for example highlight the politicised nature of minority ethnic identity. Research also suggests that those contexts which foster ethnic identity and belonging can also mobilise minorities’ political consciousness (Jacobs and Tillie Citation2004; Sanders et al. Citation2014; Sobolewska et al. Citation2015; Hainmueller, Hangartner, and Pietrantuono Citation2015).

We might, therefore, expect minorities' recognition of their ethnicity as salient (‘ethnic social identity’) to go hand in hand with recognition of politics as an important identity domain (‘political social identity’). However, we lack empirical evidence on whether this is the case.

Majority ethnic and political identities

Majority ethnic identities, by contrast, have often in the past been normalised or neglected in studies of ethnic identity, with ethnicity being seen to be the preserve of minorities (Fenton and Mann Citation2011). However, a burgeoning body of research now explicitly interrogates majority or native populations’ ethnic identity. This literature suggests that ethnic identification among the majority is weaker than among minorities, but is also more contextually specific (Nandi and Platt Citation2015, Citation2016). That is, it comes into relief under specific local, temporal and political conditions (Kenny Citation2014). Contemporary English identity expression has been linked to a specific ‘sense of the nation’ (Bond Citation2017; Leddy-Owen Citation2014; Kumar Citation2003); and across Europe, we see that national identities are being reconceived. Instead of civic constructions of nationhood (Smith Citation1991), the ethnic roots of national identities (Wimmer and Glick Shiller Citation2003) appear to be finding increasing expression within the associated movements in countries such as Austria, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, The Netherlands and the UK, with corresponding implications for cohesion and solidarity (Reeskens and Wright Citation2013) and anti-immigrant prejudice (Pehrson, Vignoles, and Brown Citation2009). Huntington’s (Citation1993) claims about cultural clash have found resonance in the political retreat from multiculturalism (Koopmans Citation2013); and public attitudes have shown a belief in the incompatibility of shared identities in multicultural societies (e.g. Duffy and Frere-Smith Citation2014).

In the UK, political parties have aimed to mobilise such ethnic nationalism by linking ethnic and political identity explicitly among majority (white) populations (Wyn Jones et al. Citation2012; Bechhofer and McCrone Citation2014; Bond Citation2017; Henderson et al. Citation2017). The rise of the anti-immigration UK Independence Party (UKIP) in the years up to 2016 was implicated in a particular construction of national identity, linked to nostalgia for an imagined past of traditional values and certainties, which invoked specific cultural understandings of Englishness (Kumar Citation2003). Such strategies appeared to pay off in electoral terms, with Englishness clearly implicated in the recent ‘Brexit’ vote (Henderson et al. Citation2017); and awareness of ethnic identity among majority (white) populations has been associated with particular forms of political consciousness, but there is very little empirical evidence of this co-evolution. Indeed, existing research suggests that there is no simple relationship between white majorities’ sense of the salience of their ethnicity (and anti-immigrant sentiment) and their political mobilisation (e.g. Thomas et al. Citation2018; Duffy and Frere-Smith Citation2014). Rather, political commitment and ethnic orientation vary in complex ways (Kenny Citation2014). It therefore remains open to investigation whether similar factors are implicated in majority ethnic and political identities

Our study

Building on the previous discussion, rather than interrogating ethnic identity as the driver of political orientation or behaviour (Fischer-Neumann Citation2014; Martinovic and Verkuyten Citation2014), our aim in this study is to investigate the extent to which drivers are common across political and ethnic identity for both the majority and minorities. We posit that there will be individual and contextual influences on these identities, which are susceptible to measurement. We also posit that there are factors representing the political climate and ethno-nationalist and anti-immigrant discourses, which are unobservable at the individual level. From existing research, we can derive expectations about how these observed and unobserved factors might shape identities.

Individual-level influences on ethnic and political identity

If political identity is associated with political engagement, we might expect factors influencing political identity to be comparable for minorities and majority, as has been shown for political engagement in earlier research (Sanders et al. Citation2014; Heath et al. Citation2013). For ethnic identity, we might expect there to be more relevant individual-level influences among the majority, since ethnic identity has been shown to be less susceptible to variation in characteristics among minorities (Nandi and Platt Citation2015). Gender is an exception. Being a woman is typically associated expected with weaker political engagement (Kittilson Citation2016), and we expect it to be associated with weaker political identity for both majority and minorities; but among minorities it is expected to be associated with stronger ethnic identity, as women are regarded as the ‘bearers of culture’ (Winter Citation2016) and appear to be more sensitised to minority ethnic ‘markers’ (Warikoo Citation2005).

Education has been negatively linked to ethnic identity and positively linked to political identity / political engagement (Fischer-Neumann Citation2014; Strand Citation2014; Nandi and Platt Citation2015), since educational attainment provides an alternative and valued source of identity for minorities, and increases awareness of and engagement with politics across the board.

We expect political party support to be linked to greater political identity. We anticipate that right-wing political affiliation, as well as that within the devolved administrations of the UK, will be associated with stronger ethnic identity among the majority; and more left-wing political affiliation associated with stronger ethnic identity among minorities, given the ways in which left-wing parties tend to more explicitly espouse issues of diversity and minority rights (see discussion in Martin and Mellon Citation2020).

Finally, some characteristics are more likely to affect identity among minorities. Much of the ethnic identity literature reflects the particular salience of Islam within political discourse and as a marker of identity (Van Heelsum and Koomen Citation2016; Zolberg and Woon Citation1999; Cameron Citation2011; Karlsen and Nazroo Citation2013). Given this and the politisisation of Muslims within the public sphere (Ahmad and Evergeti Citation2010; Diehl, Fischer-Neumann, and Mühlau Citation2016), we would expect Muslim religious affiliation to be associated with greater political identity among minorities, particularly among the second generation (Just, Sandovici, and Listhaug Citation2014). Harassment on ethnic or racial grounds brings ethnic boundaries and outgroup membership into sharp relief. We would thus expect it to be associated with both greater ethnic and political identity, as identified by Simon and Grabow (Citation2010).

Despite Rumbaut’s (Citation1997) claims for reactive ethnicity, existing research suggests that minorities’ ethnic identity declines across generations (Platt Citation2014; Van Heelsum and Koomen Citation2016) or becomes more transnational in orientation (Muttarak Citation2014; Jacobson Citation1997). The second generation can be expected to have a greater understanding of the political system and may be more attuned to political messages and the sensitivity to politics that comes from a greater awareness of inequities (Platt Citation2014; Heath and Demireva Citation2014). At the same time, Heath et al. (Citation2013) point to ‘assimilation’ to a relatively low level of engagement among (young) minorities across generations. Martin and Mellon (Citation2020) show however a rather large degree of political partisanship among minority youth. On balance, we expect the second generation to have lower ethnic identities but stronger political identities than the immigrant generation, once we have controlled for age.

Common unobserved influences on ethnic and political identity

If the political climate and ethnic mobilisation are shaping ethnic and political identities, we would expect common, unobserved drivers of identities to differ across subpopulations in theoretically predictable ways. Specifically, we would expect such common unobserved influences to be greater among the majority than among minorities, and that the association will be greater among those majority group members with more conservative / right-wing views. We explain why.

Politicians and ‘attitude formers’ such as media outlets aim to mobilise political engagement through causing other aspects of identity – and individuals’ investment in these identities – to become salient (Wodak and Khosravinik Citation2013). This is a key strategy to mobilise politically those who have a weaker political identity and low electoral participation rates. The effectiveness of these strategies depends on being able to trigger an ‘ingroup’ political identity which can be opposed to an ‘outgroup’ (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986). Since it is normalised, majority ethnic identity is typically weaker than minority identity (Brewer Citation1991; Nandi and Platt Citation2016), and may, therefore, be more susceptible to being triggered in such ways. For example, in the US, ethnic ‘messaging’, linking particular understandings of ‘nation’ and ethnos, has been used in attempts to roll back the state through linking ‘welfare’ with migration (Hopkins Citation2010). In the UK, invocation of a nostalgic version of national identity has been employed to mobilise opposition to EU membership (Kumar Citation2003; Wilson and Hainsworth Citation2012).

Minority status is arguably consistently salient in everyday interactions and remains relatively stable across contexts (Kinket and Verkuyten Citation1997). While minorities’ political identity is likely to demonstrate some sensitivity to the broader socio-political context that also shapes majority identity, minorities’ ethnic identities can be expected to be less malleable and therefore the joint influence will be less. Investment in ethnic and political identities may additionally be considered to be alternatives, particularly if confidence in political systems is low or the political discourse is antagonistic (Sanders et al. Citation2014). Conversely, the second generation who have a stronger perception of discrimination (Heath and Demireva Citation2014), may experience greater politicisation as their attachment to the specific ethnicity of their parents and parents’ countries of origin declines (Platt Citation2014; Jacobson Citation1997; Muttarak Citation2014).

We would also expect a stronger correlation between the unobservables driving the two identities among majority individuals supporting nationalist parties in the devolved administrations where nationhood, politics and ethnicity are effectively merged (Bechhofer and McCrone Citation2014). If political engagement among the majority is driven by encouraging the ethnic identification, we would expect the correlation coefficient among white UK members with no party affiliations also to be high, but driven in this case by common factors implicated in a lack of political and ethnic identification.

Data and methods

Data and sample

We use data from Understanding Society, the UK Household Longitudinal Study, a household panel survey of a nationally representative sample of 26,000 households and an ethnic minority boost sample of around 4000 households that started in 2009 (University of Essex Citation2018). All adult (16+ year old) members of the sampled household are interviewed at one-year intervals (Knies Citation2017). For further information on the relevance of Understanding Society for research on ethnicity, see Platt and Nandi (Citation2020). Core content asked at each wave (on family, education, employment, income and health) is supplemented by rotating content (on identity, political behaviour, gender attitudes, the composition of social networks, etc.) asked at specific intervals. Adult interviews are carried out face-to-face, supplemented by a self-completion questionnaire for sensitive questions. We draw on the identity questions carried in the self-completion questionnaire fielded in the second wave. Our analysis is thus restricted to all adult respondents who completed the wave 2 self-completion, provided valid responses on relevant covariates, and were not excluded for analytical reasons (for example white minorities, as discussed below). This provided us with an analytical sample of 27,851 individual respondents, interviewed during 2010–2011, made up of 23,324 majority and 4527 minority group members. For analysing the role of harassment among minorities, we restricted the analysis to the 2859 minority group members who provided this information (McFall, Nandi, and Platt Citation2017).

Measures

Ethnic group

Ethnic group was measured with the Office for National Statistics [ONS] 2011 Census 17-category, self-reported ethnic group question. We coded those who reported their ethnic group as ‘white – British/ English/ Scottish/ Welsh/ Northern Irish’ and who were born in the UK as the white UK, or the majority. Those who chose this category but were not born in the UK were excluded, due to the difference in their histories of settlement in the UK. The other white categories were also excluded from analysis since their identity patterns were more similar to the majority than to the other minority groups (see Figure A2 in the Supplementary materials).Footnote1 All other categories were coded as (non-white) ethnic minority.

Given that we are concerned with ethnic mobilisation, polarisation around minority status, and the construction of the majority as having ethnic claims to nationhood, opposed to the minority ‘other’, we focus on this binary distinction.

Dependent variables: ethnic identity and political identity

Our dependent variables derive from a multi-domain identity question modelled on a validated suite of questions originally fielded in the UK’s Citizenship Survey (CLG Citation2009). Respondents were asked to complete an assessment of the importance of identity across seven domains (age, family, gender, profession, education, political beliefs and ethnic or racial background). Questions took the form:

We’d like to know how important various things are to your sense of who you are. Please think about the following and tick the box that indicates whether you think it is very important, fairly important, not very important or not at all important to your sense of who you are.

We combined ‘Don’t know/doesn’t apply’, with ‘not at all important’ responses.

We reverse-coded the identity questions, so that higher values represented greater salience. We then computed the mean of individual-level responses across all five domains (age, family, gender, profession, education) other than political identity (‘your political beliefs’) and ethnic identity (‘Your ethnic or racial background’). Figure S1 in the Supplementary materials illustrates the distribution of scores for majority and minorities, with minorities tending to identify more strongly.

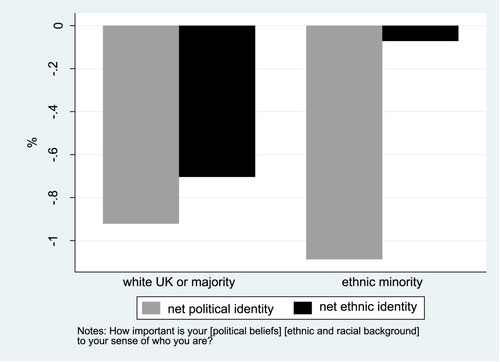

We next subtracted this mean individual-level identity score from each respondent’s political and ethnic identity scores to create ‘net’ political and ‘net’ ethnic identity scores. These net scores purged the political and ethnic identity responses of any individual-level tendency to ‘identify’ more or less strongly and of the effects of ‘satisficing’ (that is, where respondents choose the same response option on multiple-domain questions to minimise effort). If the tendency to identify or satisfice differs across majority and minorities, then this could bias our conclusions about differences in the strength of ethnic and political identity and the association between the two. Figure S2 in the Supplementary materials, shows the distribution of these net scores across all ethnic groups. Most minority groups have similar scores and differ from the white UK or majority. This lends further support to our analytical majority–minority distinction. These net identity scores form our two dependent variables (see for their average values for the majority and minority).

Explanatory variables

Sex: We coded respondent’s self-reported sex as 0 for men and 1 for women.

Educational qualifications: We used a six-category measure of highest educational qualifications: university degree or higher (reference), other higher educational qualifications, Advanced level (age 18) or equivalent, GCSE (age 16) or equivalent, other qualifications, no qualifications.

Political orientation: In the absence of a clear left-right scale in Understanding Society, in order to proxy the left-right wing orientation of respondents, we used political affiliation. Respondents were asked what party they supported. If they supported none, they were asked which party they were closer to. If none, they were asked if there were to be a general election tomorrow which party they would be most likely to support. We combined the responses to produce a measure of political affiliation where we interpreted Conservative as more right wing and LibDem, Green and Labour as more left wing. We separated out regional parties, given these are linked to specific ethno-national identities in the smaller countries of the UK. We categorised those with no political affiliation on any of these measures as a separate category.Footnote2

UKIP and BNP presence in the neighbourhood: We merged Understanding Society data with data on the 2010 General Election results linked to the respondent’s address at the level of the parliamentary constituency. We included the proportion of valid votes cast for UKIP and the British National Party (BNP) in the 2010 UK General Elections, to test the influence of these parties on ethnic and political identities.

Muslim: Respondents were asked if they had a current religion, and, if not, whether they were brought up in a religion. We classified all those who identified Islam on either of these questions as Muslim and all others, including no religion, as the reference group.

Generation: We coded those minorities who were born in the UK as second generation (reference) and those born outside UK as first generation.

Harassment: In the first wave of the study, respondents were asked if they were (i) physically attacked in, (ii) insulted in, (iii) felt unsafe in, or (iv) avoided a series of public places, over the past 12 months. If they answered yes they were asked the reason. From this we first computed a three-category variable: the respondent had neither experienced harassment nor felt unsafe/avoided being in any of these places (reference); they had been physically or verbally abused in any of these places; they felt unsafe in or avoided these places. We created a second two-category measure of whether the respondent had experienced physical or verbal abuse because of their ethnicity, religion or nationality, or not (reference).

Controls: age, current marital status, main activity status, socio-economic class (highest within the household) and household income (five income bands based on imputed gross monthly household income, adjusted for household size using the modified OECD scale).

Analytical strategy

From our understanding of the literature on ethnic and political identity, these identities are mutually implicated and constituted (Huddy Citation2001; Kenny Citation2014). Estimating models of the effect of ethnic identity on political identity or vice versa conceptualise one of these identities causally affecting the other directly and thus do not allow estimation and verification of the theoretical contention that common contextual factors (some of which cannot be observed in their variation at the individual level) and unmeasurable individual-level characteristics (such as specific traits and orientations) influence the strength of both political and ethnic identity simultaneously.

We, therefore, estimated political and ethnic identity as joint processes but allowing their errors to be correlated using the method of Seemingly Unrelated Regressions (SUR), operationalised by the sureg command and implemented in Stata 14. By allowing the errors to be correlated, we were able to estimate the existence and strength of common unobserved contextual and individual factors based on the degree of correlation of the error terms. As we include explanatory variables that may be associated with both ethnic and political identities, the correlation of the error terms is net of these observed terms. This method is thus not only the most appropriate but the only possible method to allow us to properly answer our research question. This method additionally allows different sets of explanatory variables to be included in each model. We have assumed that the error terms are not correlated with the explanatory variables across both equations as this is needed for the identification of the coefficients. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to estimate the existence and strength of the (unmeasurable) co-evolution process of political and ethnic identities.

We estimated these models separately for ethnic minority and majority groups. In subsequent specifications, we also estimated these models separately for sub-groups split by their party affiliations. We report the correlation coefficient between the unobserved or error terms of the two equations as an indicator of the degree to which ethnic and political identities covary after controlling for observed factors expected to affect both identities. Clearly there will be other unobserved drivers of either political or ethnic identity, for example, ecological commitment or cultural practices, but these are not necessarily correlated with each other. Our interest is in the factors that plausibly drive both ethnic and political identity and the extent to which these align with our theoretical expectations.

We estimated additional models including (a) Muslim religious affiliation, and (b) harassment. As the correlation of unobservables was almost identical for the model including Muslim affiliation we do not report it separately. However, we do report the correlations for the models with our two measures of harassment, as they were estimated on the reduced sample of minorities only. The correlations are similar for ethnic minorities across the two samples.

Given we know that identities vary with region of residence (Nandi and Platt Citation2016), region could potentially influence political and ethnic identity in unmeasured ways. Failure to account for it would then bias upwards the correlation of the error terms. We, therefore, estimated additional specifications including government office region. We further investigated potential confounding at the local level and estimated another specification including small area (LSOA) deprivation. As the correlations of error terms were almost identical in these specifications, we do not report these results.

Descriptive statistics

reports weighted means and proportions of the variables used in this analysis, by majority and minority group.

Table 1. Weighted estimates, by majority and minority groups.

The differences between minorities and majority are in the expected directions. The sex composition is quite similar, but minorities have a younger age composition, are less likely to be retired, are more likely to be taking care of the family, are more likely to have a degree qualification, are less likely to be in a non-marital cohabitation, but are more likely to be never married. These patterns are in line with recent evidence on the characteristics of UK immigrants and the second generation (Dustmann, Frattini, and Theodoropoulos Citation2010; ONS Citation2014). There is little difference in income and social class (NSSEC) profiles at the aggregate level.

Ethnic identity is much stronger among ethnic minorities than the majority, as we would expect. But by contrast with typical assumptions, as shows, net ethnic identity is nevertheless negative for minorities, indicating that other sources of identity (age or life stage, gender, family, education, profession) are more salient. Net political identity is weaker than other identities for both majority and minorities and is relatively similar between the two.

Results

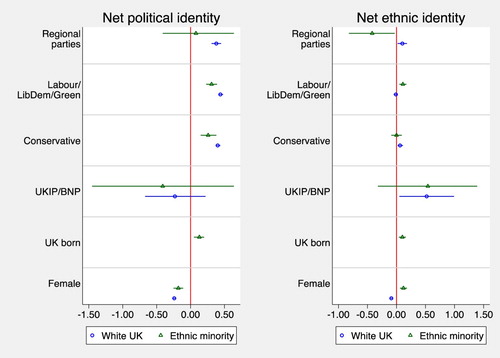

We first investigate which observed characteristics are associated with stronger political and ethnic identity, and whether these are the same for the majority and minority groups. The estimated coefficients from the political and ethnic identity models are reported in . We illustrate certain key relationships in . As anticipated, women have weaker political identities than men. But while majority women have weaker ethnic identity than majority men, as expected, ethnic minority women have stronger ethnic identity than ethnic minority men. The differences in this association between gender and ethnic identity are significant across the models, consistent with claims that women have stronger ethnic identities as the ‘carriers of culture’ (Winter Citation2016).

Figure 2. The association of selected individual and contextual characteristics with majority and minority political identity.

Table 2. Estimated coefficients of models of strength of (net) political and ethnic identity estimated using SUR.

In line with earlier evidence, attaining a degree is associated with weaker ethnic identity. But our expectation that higher levels of education would be associated with stronger political identity is only found for the majority not for ethnic minorities. We speculate that, given the high educational aspirations of ethnic minorities (Strand Citation2014), education may provide an alternative not only to ethnic but also to political identity – a question beyond the scope of this paper, but one which merits future scrutiny.

In terms of the local political context, the share UKIP/BNP in the local area is associated with stronger ethnic (but not political) identities. Note that this is net of individual characteristics and own party affiliation. This suggests that the political messaging around ethnic ingroups and outgroups propagated in such environments may lead to the greater salience of own ethnic identity – particularly for majorities, who may become more self-conscious about an otherwise ‘latent’ sense of ethnic identity.

In relation to generation, the second generation reports stronger ethnic identity than the first generation, when controlling for other covariates. This is at first challenging to square with earlier evidence (e.g. Platt Citation2014), but the answer may lie in the nature of the measures. Typically, ethnic identity questions require identification with a specific identity (e.g. your mother’s/ father’s ethnic group) or a named identity (‘Pakistani’ ‘Caribbean’ etc.). But our question did not prejudge the content of that identity – it leaves the meaning of ‘ethnicity’ for the respondent to supply. Abundant research demonstrates that identities are imbued with different meanings for respondents (e.g. see the discussion in Huddy Citation2001); hence, what respondents are envisaging when asked about their ‘ethnicity’ may be rather different to when they are asked about the importance of being, say, Indian or Ghanaian. The second generation are acutely aware of and sensitised to their ‘ethnic difference’ (Heath and Demireva Citation2014), without necessarily investing to the same extent in the ethnicity specifically linked to their parental country of origin. Instead, they may be reconceptualising their ethnic identity in ways that speak to more transnational orientations (Muttarak Citation2014) or higher level groupings (Jacobson Citation1997). These findings provide suggestive preliminary evidence for a form of reactive ethnicity (Rumbaut Citation1997) that has not previously been found in UK studies. The second generation also expresses stronger political identity than the immigrant generation, as we expected.

Turning to the posited relationship with the broader political context, political mobilisation by political parties and politicised discourses around ethnicity, we report the estimated correlation coefficients of the unobserved or errors terms from the two models based on the weighted SUR models in . These estimated correlation coefficients for both majority and minorities are positive and statistically significantly different from zero (based on the Breusch–Pagan test of independence). These indicate that there are common unmeasured factors associated with both ethnic and political identity.

Table 3. Estimated correlation coefficient of the (unobservables) error terms in the political and ethnic identity models.

We find evidence that this correlation is stronger among the majority than among ethnic minorities (0.33 compared to 0.18), in line with our expectations. As expected, among majority members, we find the correlation coefficient for right-wing members, who were argued to be more sensitive to the common political context, to be higher than for other political-ethnic combinations (excepting regional parties). The correlation coefficient for majority members with affiliation to the Conservative party is 0.35 while it is 0.28 among majority members with affiliation to the Labour, Liberal Democrats or Green parties.Footnote3

As regional parties have generally mobilised people on the basis of country-based identities, which would be interpreted by the respondents as their ethnic identity (Bechhofer and McCrone Citation2014), it follows that the correlation coefficient for this group would also be higher: 0.44.

In line with expectations, we also find the correlation coefficient for majority members with no party affiliations to be high at 0.36, though we expected this would be because of relatively low identification on both measures. This is supported by the fact that the association of political identity with party orientation among the majority is positive and significantly higher for all party affiliations as compared to those having no party affiliation (see and ).

Among ethnic minorities, not only is the correlation coefficient of the underlying unobservables of ethnic and political identity models much lower (0.18), the correlations across different party affiliations show an opposite pattern to the majority (0.12 among the Conservatives and 0.22 among the Labour, Liberal Democrats or Greens).

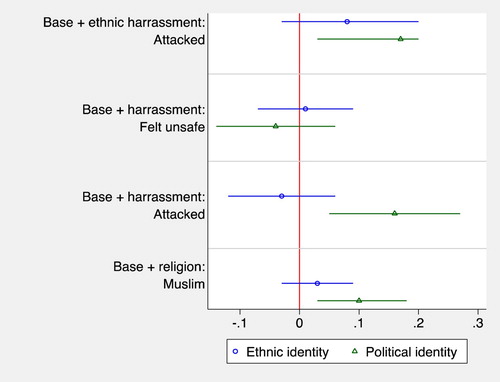

We estimated separate models of political and ethnic identity for minorities including religious affiliation as Muslim and experience of harassment. These estimated coefficients are reported in and illustrated in . We argued that the politicisation of Islam in political, popular – and also academic – discourse might have implications for the identity patterns of Muslims in particular. shows that there is no statistically significant difference in the ethnic identity of Muslims and non-Muslims, but Muslims report significantly stronger political identity than non-Muslims. The increasing political and social acceptability of anti-Muslim attitudes would appear to translate into a politicisation of those identities (Ahmad and Evergeti Citation2010).

Figure 3. The association of harassment and Muslim affiliation with minorities’ (net) ethnic and political identities.

Table 4. Estimated coefficients of models of strength of (net) political and ethnic identity estimated using SUR.

When testing the contribution of ethnic and racial harassment we found no statistically significant support for an association between harassment and ethnic identity, in line with other studies (e.g. Nandi and Platt Citation2015; Platt Citation2014), though the point estimate is positive (see ). The lack of a clear association is possibly because ethnic and racial harassment is measured in the year before the interview, while ethnic identities develop over much longer period. But we do find that such an experience has a positive and significant association with political identity. The same relationship is observed for harassment for any reason. The fact that harassment is associated with political identity suggests that adverse experiences can lead to reflection on the systems within which they are perpetuated.

Discussion

Ethnic identity is subject to increasing analysis and political debate in Western European countries. Political claims about lack of minority endorsement of national identity have been accompanied by a rise in populist conceptions of the nation, embedded in specific political and cultural understandings of the past (Kenny Citation2014). But empirical evidence of this co-evolution of political and ethnic identities is lacking. In this paper we investigated the relationship between political and ethnic identity across ethnic minorities and majority in the UK, using data from large, nationally representative survey, Understanding Society.

We showed, first, that not only political identity but also ethnic identity was considered less important than other identity domains. Second, we found largely similar associations between observed characteristics and both political and ethnic identities for all. An exception was that majority group women had weaker ethnic identities than men while minority women tended to have stronger ethnic identities than men. We also noted that the share of the vote for BNP/UKIP was associated with stronger ethnic rather than political identification. This provided some initial support for the co-evolution of ethnic and political identities.

We estimated the role of broader political mobilisation by political parties and politicised discourses around ethnicity, by considering the extent to which unobserved determinants of both ethnic and political identity were correlated. We found substantial and statistically significant correlations between the unobserved (unmeasured) factors that influence both ethnic and political identification, and that these were in line with the theorised relationships. That is, the association was substantially greater for the ethnic majority; and was larger among those majority members with more conservative/traditional orientations, devolved party affiliations and those with no party affiliation.

We also found that second-generation minorities tended to have stronger political and ethnic identity than the first generation. Rather than generational assimilation towards greater political apathy (Heath et al. Citation2013) or ethnic identity decline, this suggests a greater awareness and sensitivity to minoritised status that is not necessarily picked up by standard measures. Martin and Mellon (Citation2020) highlight the levels of political partisanship among ethnic minority youth, which could be one part of the pathway to this greater sensitivity.

Being Muslim and having experienced harassment were significantly associated with stronger political, but not ethnic, identity among minorities. Ethnic and racial harassment was also associated with stronger political identity but not stronger ethnic identity.

Despite limitations to our analysis, namely that we assume we have captured all relevant observables in our analyses, that we cannot make causal claims for the associations between our covariates and our identity outcomes, and that we lack direct indicators of political mobilisation that might allow us more thoroughly to test our proposed claims, we nevertheless consider our paper makes a contribution to the literatures on ethnicity and identity in the following ways.

We present the first, to our knowledge, attempt to shed light on the relationship between ethnic and political identity that does not presuppose the determination of one by the other. We provide suggestive empirical evidence of the way ethnic and political identity are jointly mobilised and respond to contextual factors that are by definition challenging to capture at the individual level.

Second, by using a ‘net’ measure of ethnic identity, we purged it of individual-level tendencies to identify more or less strongly. This was important given the tendency to identify more strongly among minorities. Having done this, we found that while political identity was less salient across majorities and minorities than other identities, net ethnic identity was also less salient, for minorities as well as for the majority. This indicates that rather than being the most significant aspect of identity across minorities, as much ethnic identity research implicitly or explicitly suggests, minorities are (more) heavily invested in other aspects of their identity. There is substantial scope to pay further attention to these different identity ‘choices’, their drivers and implications (Huddy Citation2001).

Third, that we identified Muslim religious affiliation as associated with political but not ethnic identity indicates not only the way the discourse around Islam is heavily politicised and leads to political identification. It also undermines the dominant discussion of Muslims as heavily invested in ethnic identity and self-segregation from national processes (Cameron Citation2011; DHCLG Citation2018).

Finally, against a backdrop of studies which have shown declining ethnic identity across the generations, our findings lend tentative support to theories of ‘reactive ethnicity’ (Rumbaut Citation1997). That is, the salience of ethnic – as well as political – identity was greater in the second generation. This is in line with the theory that reaction to ‘assimilative processes’ and greater sensitivity to group boundaries occurs as enduring ethnic inequalities are realised. But it raises the question of why our results differ from other UK research that has investigated change in ethnic identification across the generations and come to the opposite conclusion. We noted that respondents were not asked about a specific ‘pre-imposed’ identity but were able to interpret ethnic identity in their own terms. We cannot, therefore, extrapolate what ‘ethnicity’ they had in mind when expressing this identity, but it is consistent with a more expansive or transnational concept of ethnicity than that constrained by specific categories (Muttarak Citation2014; Jacobson Citation1997).

Our findings indicate further lines of research. First, given the cross-national populist currents and anti-immigrant sentiments in many countries, it would be of interest to identify whether similar findings could be replicated in other contexts. Second, given the dominance of other identity domains for both majority and minorities, it would be worth interrogating how these themselves covary and are linked to stronger or weaker patterns of social and political engagement. Our findings indicating reactive ethnicity also merit further interrogation, with more direct intergenerational analysis and consideration of the consequences for group relations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank three anonymous referees, Wouter Zwysen and participants at the 2018 ISA RC28 Poster Session in Toronto and at the Understanding Society Scientific Conference 2017 in UK for their helpful feedback. Understanding Society is an initiative funded by the Economic and Social Research Council and various Government Departments, with scientific leadership by the Institute for Social and Economic Research, University of Essex, and survey delivery by NatCen Social Research and Kantar Public. The research data are distributed by the UK Data Service.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Alita Nandi http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8743-6178

Lucinda Platt http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8251-6400

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Very few individuals (around 25) chose ‘white – Roma or Gypsy Traveller’ as their ethnic group.

2 We explored alternative proxies for political orientation including (non)-traditional attitudes, but retained this measure as closest to the construct we aimed to proxy.

3 An alternative measure using (in)egalitarian gender role attitudes to proxy traditionalism / right wing orientation produced comparable results (0.30 for high egalitarian, 0.33 for the rest).

References

- Abrams, D. 2010. Processes of Prejudice: Theory, Evidence and Intervention. Equality and Human Rights Commission. Research report 56. Manchester: EHRC.

- Abrams, D., and M. A. Hogg, eds. 1999. Social Identity and Social Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers.

- Ahmad, W. I. U., and V. Evergeti. 2010. “The Making and Representation of Muslim Identity in Britain: Conversations with British Muslim ‘Elites’.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (10): 1697–1717.

- Bechhofer, F., and D. McCrone. 2014. “Changing Claims in Context: National Identity Revisited.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (8): 1350–1370.

- Bond, R. 2017. “Sub-state National Identities among Minority Groups in Britain: A Comparative Analysis of 2011 Census Data.” Nations and Nationalism 25 (3): 524–546.

- Brewer, M. B. 1991. “The Social Self: On Being the Same and Being Different at the Same Time.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 17: 475–482.

- Brubaker, R. 2001. “The Return of Assimilation? Changing Perspectives on Immigration and its Sequels in France, Germany, and the United States.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 24 (4): 531–548.

- Cameron, D. 2011. “PM’s speech to the Munich Security Conference.” https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/pms-speech-at-munich-security-conference.

- Communities and Local Government [CLG]. 2009. 2007-08 Citizenship Survey Identity and Values Topic Report. London: Department for Communities and Local Government.

- Constant, A. F., L. Gataullina, and K. F. Zimmermann. 2009. “Ethnosizing Immigrants.” Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 69 (3): 274–287.

- Deaux, K., A. Reid, K. Mizrahi, and K. A. Ethier. 1995. “Parameters of Social Identity.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68: 280–291.

- Department of Housing, Communities and Local Government [DHCLG]. 2018. “Integrated communities strategy green paper.” https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/696993/Integrated_Communities_Strategy.pdf.

- Diehl, C., M. Fischer-Neumann, and P. Mühlau. 2016. “Between Ethnic Options and Ethnic Boundaries – Recent Polish and Turkish Migrants’ Identification with Germany.” Ethnicities 16 (2): 236–260.

- Diehl, C., and R. Schnell. 2006. “‘Reactive Ethnicity’ or ‘Assimilation’? Statements, Arguments, and First Empirical Evidence for Labor Migrants in Germany.” International Migration Review 40 (4):786–816.

- Duffy, B., and T. Frere-Smith. 2014. Perceptions and Reality: Public Attitudes to Immigration. London: Ipsos MORI Social Research Institute.

- Dustmann, C., T. Frattini, and N. Theodoropoulos. 2010. “Ethnicity and Second Generation Immigrants.” CReAM Discussion Paper Series 1004, Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration (CReAM), University College London.

- Fenton, S., and R. Mann. 2011. “Our Own People’: Ethnic Majority Orientations to Nation and Country.” In Global Migration, Ethnicity and Britishness, edited by T. Modood and J. Salt, 225–247. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fischer-Neumann, M. 2014. “Immigrants’ Ethnic Identification and Political Involvement in the Face of Discrimination: A Longitudinal Study of the German Case.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (3): 339–362.

- Hainmueller, J., D. Hangartner, and G. Pietrantuono. 2015. “Naturalization Fosters the Long-Term Political Integration of Immigrants.” PNAS 112 (41): 12651–12656.

- Heath, A., and N. Demireva. 2014. “Has Multiculturalism Failed in Britain?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (1): 161–180.

- Heath, A. F., S. D. Fisher, G. Rosenblatt, D. Sanders, and M. Sobolewska. 2013. The Political Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Henderson, A., C. Jeffery, D. Wincott, and R. Wyn Jones. 2017. “How Brexit was Made in England.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 19 (4): 631–646.

- Hopkins, D. 2010. “Politicized Places: Explaining Where and When Immigrants Provoke Local Opposition.” American Political Science Review 104 (1): 40–60.

- Huddy, L. 2001. “From Social to Political Identity: A Critical Examination of Social Identity Theory.” Political Psychology 22 (1): 127–156.

- Huntington, S. P. 1993. “The Clash of Civilizations?” Foreign Affairs 72 (3): 22–49.

- Jacobs, D., and J. Tillie. 2004. “Introduction: Social Capital and Political Integration of Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (3): 419–427.

- Jacobson, J. 1997. “Religion and Ethnicity: Dual and Alternative Sources of Identity among Young British Pakistanis.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 20 (2): 238–256.

- Jenkins, R. 2014. Social Identity. 4th ed. Cambridge: Polity.

- Just, A., M. E. Sandovici, and O. Listhaug. 2014. “Islam, Religiosity, and Immigrant Political Action, in Western Europe.” Social Science Research 43: 127–144.

- Karlsen, S., and J. Y. Nazroo. 2013. “Influences on Forms of National Identity and Feeling ‘at Home’ among Muslim Groups in Britain, Germany and Spain.” Ethnicities 13 (6): 689–708.

- Kenny, M. 2014. The Politics of English Nationhood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kinket, B., and M. Verkuyten. 1997. “Levels of Ethnic Self-Identification and Social Context.” Social Psychology Quarterly 60: 338–354.

- Kittilson, Miki Caul. 2016. “Gender and Political Behaviour.” Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Politics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.71.

- Knies, G., ed. 2017. Understanding Society –UK Household Longitudinal Study: Wave 1-7, 2009-2016, User Guide. Colchester: University of Essex.

- Koopmans, R. 2013. “Multiculturalism and Immigration: A Contested Field in Cross-National Comparison.” Annual Review of Sociology 39: 147–169.

- Kumar, K. 2003. The Making of English National Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Leddy-Owen, C. 2014. “Reimagining Englishness: ‘Race’, Class, Progressive English Identities and Disrupted English Communities.” Sociology 48 (6): 1123–1138.

- Manning, A., and S. Roy. 2010. “Culture Clash or Culture Club? National Identity in Britain.” The Economic Journal 120: F72–F100.

- Martin, N., and J. Mellon. 2020. “The Puzzle of High Political Partisanship among Ethnic Minority Young People in Great Britain.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (5): 936–956. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1539285.

- Martinovic, B., and M. Verkuyten. 2014. “The Political Downside of Dual Identity: Group Identifications and Religious Political Mobilization of Muslim Minorities.” British Journal of Social Psychology 53: 711–730.

- McFall, S., A. Nandi, and L. Platt. 2017. Understanding Society: UK Household Longitudinal Study: User Guide to Ethnicity and Immigration Research. 4th ed. Colchester: University of Essex.

- Modood, T. 2007. Multiculturalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Muttarak, R. 2014. “Generation, Ethnic and Religious Diversity in Friendship Choice: Exploring Interethnic Close Ties in Britain.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (1): 71–98.

- Nandi, A., and L. Platt. 2012. “Developing Ethnic Identity Questions for Understanding Society.” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 3 (1): 80–100.

- Nandi, A., and L. Platt. 2015. “Patterns of Minority and Majority Identification in a Multicultural Society.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (15): 2615–2634.

- Nandi, A., and L. Platt. 2016. ““Understanding the Role of Contextual Factors for the Salience of Majority and Minority Ethnic Identity.” Presentation at RC28 conference 2016, Bern, Switzerland.

- Nguyen, A.-M. D., and V. Benet-Martínez. 2013. “Biculturalism and Adjustment: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 44 (1): 122–159.

- Oaks, P. J., J. C. Turner, and S. A. Haslam. 1991. “Perceiving People as Group Members: The Role of Fit in the Salience of Social Categorizations.” Social Psychology 30 (2): 125–144.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). 2014. 2011 Census Analysis: Social and Economic Characteristics by Length of Residence of Migrant Populations in England and Wales. London: ONS.

- Pehrson, S., V. L. Vignoles, and R. Brown. 2009. “National Identification and Anti-Immigrant Prejudice: Individual and Contextual Effects of National Definitions.” Social Psychology Quarterly 72: 24–38.

- Phinney, J. S. 1992. “The Multigroup Ethnic Meaure: A new Scale for Use with Diverse Groups.” Journal of Adolescent Research 7: 156–176.

- Platt, L. 2014. “Is There Assimilation in Minority Groups’ National, Ethnic and Religious Identity’.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (1): 46–70.

- Platt, L., and A. Nandi. 2020. “Ethnic Diversity in the UK: New Opportunities and Changing Constraints.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (5): 839–856. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1539229.

- Reeskens, T., and M. Wright. 2013. “Nationalism and the Cohesive Society: A Multilevel Analysis of the Interplay among Diversity, National Identity, and Social Capital Across 27 European Societies.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (2): 153–181.

- Rumbaut, R. G. 1997. “Assimilation and its Discontents: Between Rhetoric and Reality.” The International Migration Review 31 (4): 923–960

- Sanders, D., S. D. Fisher, A. Heath, and M. Sobolewska. 2014. “The Democratic Engagement of Britain’s Ethnic Minorities.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (1): 120–139.

- Simon, B., and O. Grabow. 2010. “The Politicization of Migrants: Further Evidence That Politicized Collective Identity is a Dual Identity.” Political Pscyhology 31 (5): 717–738.

- Smith, A. 1991. National Identity. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Sobolewska, M., S. D. Fisher, A. Heath, and D. Sanders. 2015. “Understanding the Effects of Religious Attendance on Political Participation among Ethnic Minorities of Different Religions.” European Journal of Political Research 54: 271–287.

- Strand, S. 2014. “Ethnicity, Gender, Social Class and Achievement Gaps at Age 16: Intersectionality and ‘Getting it’ for the White Working Class.” Research Papers in Education 29 (2): 131–171.

- Street, A. 2017. “The Political Effects of Immigrant Naturalization.” International Migration Review 51 (2): 323–343.

- Tajfel, H. 1974. “Social Identity and Intergroup Behaviour.” Social Science Information 13 (2): 65–93.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner. 1986. “The Social Identity Theory of Inter-Group Behavior.” In Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by S. Worchel and W. G. Austin, 7–24. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

- Thomas, P., J. Busher, G. Macklin, M. Rogerson, and K. Christmann. 2018. “Hopes and Fears: Community Cohesion and the ‘White Working Class’ in One of the ‘Failed Spaces’ of Multiculturalism.” Sociology 52 (2): 261–282.

- University of Essex. Institute for Social and Economic Research, NatCen Social Research, Kantar Public. 2018. “Understanding Society: Waves 1-7, 2009-2016 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009.” [data collection]. 10th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 6614. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-6614-11.

- Van Heelsum, A., and M. Koomen. 2016. “Ascription and Identity: Differences Between First- and Second-Generation Moroccans in the Way Ascription Influences Religious, National and Ethnic Group Identification.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (2): 277–291.

- Warikoo, N. 2005. “Gender and Ethnic Identity among Second-Generation Indo-Caribbeans.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 28 (5): 803–831.

- Wilson, R., and P. Hainsworth. 2012. Far Right Parties and Discourse in Europe: A Challenge for our Times. Brussels: European Network Against Racism.

- Wimmer, A., and N. Glick Shiller. 2003. “Methodological Nationalism, the Social Sciences and the Study of Migration: An Essay in Historical Epistemology.” International Migration Review 37 (3): 576–610.

- Winter, B. 2016. “Women as Cultural Markers/Bearers.” The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies 0: 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss695.

- Wodak, R., and M. Khosravinik. 2013. “Dynamics of Discourse and Politics in Right-wing Populism in Europe and Beyond: An Introduction.” In Rightwing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discours, edited by R. Wodak, M. Khosravinik, and B. Mral, xvii–xxviii. London: Bloomsbury.

- Wyn Jones, R., G. Lodge, A. Henderson, and D. Wincott. 2012. The Dog That Finally Barked. England as an Emerging Political Community. London: Institute for Public Policy Research.

- Zolberg, A. R., and L. L. Woon. 1999. “Why Islam is Like Spanish: Cultural Incorporation in Europe and the United States.” Politics & Society 27 (1): 5–38.