ABSTRACT

Over the past two decades, globalisation has propelled millions of economic migrants from poor sending-nations to seek employment in economically better-off receiving-nations, often establishing new offshoot family formation, notwithstanding national migration policies trending towards tightening border controls. State policies on border crossing and circular migration shape and frequently impinge on the development aspirations, welfare-creation strategies and ways and means of provisioning family life cycle care needs. In the process, transnational families often make material sacrifices and contend with emotional tensions between migrant parents or spouses and their stay-behind family members. Conversely state policies, which do not take family aspirations into account in migration decision-making, are unlikely to effectively meet their intended objectives.

Introduction

In 2015, world attention turned to the swelling mass movement of migrants risking their lives under hazardous conditions to gain entry to Europe from the Middle East and Africa. Despite raging political debate and the humanitarian exigencies of mounting numbers of migrants, analysis of migrants’ decision-making has been relatively superficial. In-depth information on migrants’ family structures within their home country, as well as their knowledge of border barriers, physical risks enroute, chances of finding employment, and emotional coping strategies related to physical separation from their ‘left-behind’ family members are scantily documented (Skrbiš Citation2008). Instead the scale of migration, migrants’ distress and the politically charged interface between receiving nation-states and migrants have dominated the literature and public policy debate.

The ‘migrant crisis'Footnote1 has brought the significance of global family agency to the fore. The decision to migrate was treated as an outcome of ad-hoc individual decision-making in conventional twentieth century positivist social science, overlooking family strategy and the on-going evolution of family group decision-making that takes place over the course of the family's life-cycle and successive junctures of the migrant's stay abroad. Twenty-first century transport and communication advance has facilitated transnational family coherence. The strategic agency of family welfare-seeking across national borders crystallizes transnational families as a decentralised institutional force, influencing and influenced by labour market fluctuations and state policies.

This introduction focuses primarily on the modalities and agendas of transnational families in relation to nation states and the international market. Amidst the rising global mobility of people, agency within and between these three institutions is likely to collide as their established spheres of operation and institutional functions are reconfigured. The articles that follow trace transnational family formation and life cycle evolution from different vantage points, reflecting the authors’ disciplinary specialisations and geographical case study fieldwork.Footnote2

Some broad similarities and many nuanced differences in family migration strategies centre on gender and age that are critical to who migrates, who stays behind, who cares and who is cared for materially and emotionally at various stages of the family life cycle. The case studies contrast sending and receiving country contexts in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Europe. Emphasis is on members’ perceptions of opportunities, pitfalls, fears and interpersonal coping strategies in the face of inevitable dilemmas posed by the uncertain circumstances and outcomes of international migration.

‘Transnational families’ are defined as familial groups with members living some or most of the time separated from each other, while nonetheless feeling a sense of collective welfare, unity and familyhood across national borders (Bryceson and Vuorela Citation2002). Transnational families are not new but they are definitely more numerous now than ever before. They are an evolving institutional form of human interdependence, which serve material and emotional needs, in the twenty-first century's globalising world.

The transnational family constitutes a multi-dimensional spatial and temporal support environment for migrants, as well as providing motivational impetus for migration. Migrants are nudged or prodded by their individual and family economic needs and aspirations (de Jong et al. Citation1985). Family members most likely constitute migrants’ core social network for financial and emotional support, be they home-based family members or those who have already migrated and are in a position to provide strategic assistance along the migrant's journey or at their destination.

The articles in this Special Issue trace how economic migrants and their families navigate and negotiate border-crossing including how they contend with state regulations for gaining entry, residence permits, citizenship, marriage, divorce and birth registration in the face of sudden changes or gradual hardening of immigration policies in various countries and employment circumstances. Since the turn of the millennium, a tendency for transition from blurred to brittle borders has gained momentum in the European Union and North America.

‘Blurred borders’ refer to migrants’ low risk border crossings and light regulation of their visits, affording relative openness to migrants seeking legal residence and citizenship in the receiving countries. ‘Brittle borders’ represent the opposite, involving physically and legally hazardous crossings with enforcement of stringent restrictions on temporary as well as permanent residence and remote possibility or impossibility of migrants gaining citizenship or family reunification.

Receiving countries’ immigration policy objectives since the 2008 global economic crisis have veered from boom time recruitment of cheap unskilled and skilled labour to recessionary labour market cutbacks, tightened immigration policies and, in some countries, mounting security concerns about terrorism (Carr Citation2012; Harding Citation2012). Contested mass migration of refugees across European borders came to the fore in 2015. In receiving countries, rising anti-immigration attitudes have led to unanticipated electoral outcomes with sliver thin majorities voting to leave European Union in the United Kingdom's referendum and choosing Trump, an extreme anti-migration nativist candidate in the US presidential election. Global geo-political discourse has erupted into vehement polarisation of public opinion for and against transnational family movement and multi-cultural cosmopolitanism in a number of places.

Academic discourse has a role to play in moderating the incensed debate on migrants and transnationalism. Nationalist thinking and nation-state policies are premised on the notion of families serving as the building blocks for ordered local communities, regions and nation-states. Yet most migration studies posit the individual migrant as the focus of enquiry and seem to assume migrants’ autonomy of purpose. Migration necessarily involves the physical separation of family members, making analytical observations of families logistically difficult for the researcher. Under these circumstances, family influences on migration decision-making have been inevitably sidelined in mainstream migration literature to date. Nonetheless, despite the obstacles, awareness of the far-reaching significance of family decision-making in migration strategies has been gaining momentum in recent years (Epstein and Gang Citation2006; de Jong and Graefe Citation2008; Haug Citation2008; Riccio Citation2008; Ifekwunigwe Citation2013; Andersson Citation2014).

This introductory article centres on the institutional interplay of transnational families, the global labour market and migration policies of receiving nation-states. The next section focuses on the changing nature and volume of global economic migration and the role of transnational family life cycles in generational exchange and care circulation between sending and destination branches of transnational families. Section 3 probes state immigration policies’ impact on family life cycles, tracing how the transition from blurred to brittle borders may disintegrate into broken borders with paradoxical outcomes for transnational families and nation-states. Section 4 briefly highlights transnational family issues arising in each of the case study articles. The conclusion explores the contradictory tensions evolving between decentralised transnational families and labour markets as opposed to centralised nation-states. Anti-migration isolationist political demands of segments of the national citizenry pose a panoply of issues for family welfare and state stability.

The transnational family life cycle in twenty-first century global migration

Transnational families’ conditions of existence

Unlike nineteenth century mass migration in which people left their homes permanently and were afforded very little contact with their source families (Moberg Citation1951), twenty-first century transnational family coherence is a virtually inevitable outcome of people's global mobility. With more reliable and faster forms of international transport, internet communication and global banking, current international migrants are afforded a multitude of direct and indirect ways of retaining familial contact, support and caring relationships. But technological change and the free-trade policies of the globalising world economy have a weighty downside; technology's facilitation of travel and communication and open border policies can trigger widespread labour-displacement of local people in poor countries. Increasing numbers are propelled to seek livelihoods abroad, necessitating spatial separation between family members to ensure material wellbeing. Their material dissatisfaction is often fuelled by fantasies about the availability of wealth and comfort abroad in the West.

Relationships and exchange flows between transnational family members are heavily reliant on digital technology, telecommunications and air travel (Faist Citation2000; Mazzucato et al. Citation2015). Migrants’ capacity to instantaneously communicate with distant family members by text messaging, mobile phone conversations, skyping and assorted forms of social media have been axiomatic to the initiation, maintenance and expansion of transnational family exchange.

Migration strategies are rooted within a family frame of reference, underlined by the assumption that families, be they patrilineal or matrilineal and nuclear or extended in structure, are primal and enduring, capable of withstanding the test of physical separation. Family members’ suggestions and exhortation play a catalytic role in convincing spouses and offspring to migrate. de Jong et al. (Citation1985, 53–56) observe: ‘general migration intentions [are] dominated by family pressure, family ties, life cycle, and economic resources … The former two exerting the strongest influence in the case of international migration’. While some migrants unilaterally decide to migrate, seeking individual economic benefit or escape from their family home, most will still harbour a sense of family obligation steering them towards contributions to their family's welfare further downstream (van Dijk Citation2002; Clough Citation2018).

From the outset, international migrants are likely to have a strong sense of purpose and resolve (de Jong et al. Citation1985; Andersson Citation2014), as evidenced by their willingness to endure exhausting, often hazardous journeys and long periods of deprivation before finding work. Diversifying family income to reduce the risk of income failure is a central strategic goal of migration. Families hope that the receipt of remittances from migrant members will provide a stable economic footing and/or sufficient investment capital to enhance production or raise the transnational family's standard of living (Massey et al. Citation1993; Goldin and Reinert Citation2012; Clough Citation2018).

The family life cycle

It is hazardous to generalise about the family life cycle given the seemingly boundless cultural diversity of family size and structure throughout the world. Significantly, family membership fluctuates over time, expanding on the basis of birth, adoption or marriage recruitment and contracting through divorce or death. Nonetheless, wherever families form, their intention is to provision needs for their members on a long-term basis. The family is the ultimate unit of sharing and caring, directed at ensuring material survival, welfare and development, with intergenerational transfers of goods, services and finances flowing between family members. In the case of transnational families, these flows are geographically stretched.

The ‘family life cycle’ is defined here as stages of the physical and social reproduction of a conjugal couple beginning with marriage or cohabitation, followed by the birth of children, childrearing, generational fission and death. This demographic cycle takes place alongside changing patterns of economic interdependency related to the unfolding working capacity of family members. The family facilitates basic needs provisioning of its members over short, medium and long-term durations, with effort usually centred on care of dependent members – children, the elderly and the infirm – unable to earn or provide for themselves. Boundaries and coherence of a transnational family rest primarily on emotional sentiment and mutual material exchange. Paradoxically, the geographical spread of transnational family members' residences constitute strength and weakness. The family is likely to be afforded the comparative economic advantage of higher earnings in the migrant destination country, while the lack of frequent face-to-face contact may weaken the bonds of familial sentiment and identity.

The actual designation of dependents and provisioners is contingent on the configuration of the family life cycle with respect to family size, age/gender composition, physical location and members’ generational delineation. There are specific critical junctures of the life cycle that prompt migration: when members of the ‘dependent’ generation reach an age in which they are considered capable of economic independence. In poor countries, the age of self-reliance emerges from a gradual transitional period of economic interdependence in which maturing family members have increasing work responsibilities within the household, leading to a point when they are expected to shoulder some financial responsibility for household provisioning, debt servicing, the education of younger family members, etc.

Second, birth of first or successive children may cause married couples to recalibrate their family-earning strategies. New sources of economic support are needed to facilitate daily care and family educational and health costs over the longer term, which may lead to a parent or other adult family members being obliged to take on new financial costs or responsibilities to bolster the family's economic interdependence.

The concept of a ‘family life cycle’ appears in various social science disciplines.Footnote3 Chayanov (Citation1966), approximately a century ago, considered the changing structure, size and output of the family in relation to the reproductive and productive lifetime of conjugal couples and their offspring. Dissecting the nuclear family life cycle of Russian peasant farming households, led Chayanov to develop the concept of the ‘labour-consumer balance’ analytically pivoting on the size of the family and its ratio of working to non-working members and age structures, for gauging the household's maintained equilibrium between production and consumption of family members.

Naturally the family's dependency ratio fluctuates from roughly balanced between a newly married couple, thereafter thrown off-balance by the high dependency ratio arising from the successive birth of children, eventually eased by older children contributing to the family workload, which generates a more comfortable labour-consumer balance. As offspring leave the core family household to form their own households, the family shrinks in size, while the conjugal couple ages and gradually veers towards incapacitation and the decline of the family's labour-consumer balance.

The principles of Chayanov’s (Citation1966) family life cycle approach can be adapted to transnational family patterns. Transnational family maturation naturally pivots on reproduction and production. Beginning with a single-family member's migration abroad, the balancing of intra- and inter-familial labour allocation proceeds alongside material exchange between members of the transnational family. The concept of a labour-consumer balance in the transnational family context must accommodate the reality of partial rather than full material contributions from family members living abroad, given their in situ costs and any state, market or personal impediments to remittance-sending (Clough Citation2018).

Family exchanges: bi- and multi-transnational distinctions

Just as Chayanov traced agrarian peasant family life cycles, demonstrating how generational transition results in differing dependency relations and labour-consumer balances, the life cycle concept is pertinent to understanding migrant's motivation to cross national borders and the nature of exchange flows between members located in sending and receiving branches of the transnational family. Frequently, in situ members in the home country shoulder costs of migrants’ first journey abroad. Family investment is intended to enable migrants to realise higher earnings, in exchange for future remittances from migrants’ earnings.

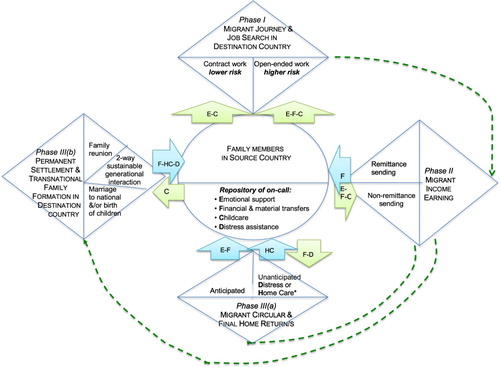

To illustrate family cycle agency between source and destination countries, provides a stylised depiction of transnational family between the migrant and his/her source family during successive phases of international migration. Phase I comprises the journey to and job search in the destination country, related to migrant's reliance on support from source country family. At the outset, there is generally a net outflow of investment from the in situ family, followed by Phase II when migrant remittance earnings come on-stream.

Figure 1. Phases of transnational family migration and care trajectories between source & destination countries. Source: Author's depiction.

While the source family anticipates remittances flows, not all migrants can or are willing to send remittances to their families. Some have migrated with the intention of pursuing a new lifestyle that may consume their full earnings. But most aim to transfer money or in-kind payments home. In return, they draw on childcare help, material transfers, as well as psychological support in the event of encountering emotional distress abroad.

indicates bifurcation between transnational family trajectories during the third phase. In many, if not most cases, migrants’ intent is to migrate temporarily such that returning home eventually comes to the fore for a variety of reasons be it: (1) anticipation of leaving when their work contract and residential rights come to an end; or (2) necessity arising from speculative migration without a work visa or documentation, failure to achieve target earnings or gain enduring remunerative work.

Apart from direct work and economic constraints, there are reasons for migrants returning home before completing the work either because: (3) they miss their family and culture or face unforeseen problems with work, their immigration status or health; or (4) they need to return home to assist with family care, often intending to return or, engage in a circular migration pattern that affords them a presence and economic stake in both countries (Martínez-Buján's article on Bolivian migrants in Spain, Citation2019). But this becomes increasingly difficult to achieve as borders become more brittle (Poeze's article on Ghanaian migrants in the Netherlands, Citation2019).

Transnational families straddle two or more households located in different cultural and political settings. schematically distinguishes the options and strategies of bi- as opposed to multi-transnational families. The former denotes a transnational family located across two countries, as opposed to the latter involving families potentially straddling three or more countries. The major difference between bi- and multi-transnational families is that bi-national modalities, conditions, material flows and fall back options are relatively restricted to simple source destination country exchange and demands and opportunities emanating from the migrant's home country.

Table 1. Distinguishing transnational families.

There are various bi-national modalities notably: first, circular labour migrants who are unlikely to gain permanent residence or citizenship in the destination country. Second, variants of marriage migration in different parts of the world contribute to the existence of bi-transnational families. The endogamous marriage practices of specific ethnic groups have given rise to bi-national populations in several European countries (e.g. Charsley Citation2005: Pakistani migration to Britain; Lievens Citation1999: Turkish and Moroccan marriage migration to Belgium). Third, commercial on and off-line marriage match-making services have proliferated worldwide. One outcome has been a surge in Asian mail-order brides usually associated with older single, divorced or widowed male citizens residing in affluent countries seeking marriage to young less-affluent foreign wives (e.g. Robinson Citation1996: Asian-Australian marriages; Yamaura Citation2015: Chinese-Japanese marriages). The general expectation in these voluntary marriages is that the migrant wife will conform to female spouse cultural norms and duties of the destination country, which may prove difficult to achieve. The wife and children of these marriage matches may experience brittle state policies towards the legal recognition of the marriage, residency and citizenship (Ishii Citation2016). They sometimes find themselves occupying peripheral uncertain and vulnerable positions in their adopted nation-state, which worsen in the event of divorce.

Multi-transnational families are more eclectic and fluid regarding cultural practices. They are searching for economic opportunities, regularisation of immigration status, as well as culturally uncharted paths. They are formed in the pursuit of educational advance, adventure or romance. Some come from families that have been dispersed abroad over generations due to peripatetic professions, overseas military service or diasporas of an ethnic or colonial nature (Bianchera et al., Citation2019; Vuorela Citation2002; Olwig Citation2007).

Bi-transnationals are more likely to lean conservatively to the customs of their homeland and/or be marginalised in the destination country, whereas multi-transnationals are likely to have skills, educational credentials and/or networks to eclectically combine, enhance and arbitrage their options across three or more cosmopolitan cultural settings.

All transnational households, be they bi- or multi-national, face a double life residing in their destination country, while subject to traditional filial or conjugal relationships when in contact with their home country or ancestral homeland. Multi-transnationals’ formation of family ties as conjugal partners and parents, may become increasingly culturally distanced from their home country or ancestral homeland. However, both bi- and multi-nationals retain some sense of identity with and care for family members abroad. Such real and imagined feelings of common identity and mutual obligation are quintessential to transnational familyhood. How transnational family members organise their productive and reproductive activities to retain contact and caring relationships is key to the welfare and development of members and the perpetuation of the transnational family unit (Vuorela Citation2002).

Understanding how the transnational family life cycle is accommodated and integrated across national borders entails probing transnationals’ family formation, changing reproductive patterns (fertility) dependency ratios, along with new attitudes towards economic dependency and interdependency within the family. A panoply of family life cycle issues arise related to how transnational families overcome the barriers of physical separation in their management of birth, death and illness and how new attitudes to family size and family members’ roles impact on family welfare within and between sending and receiving countries.

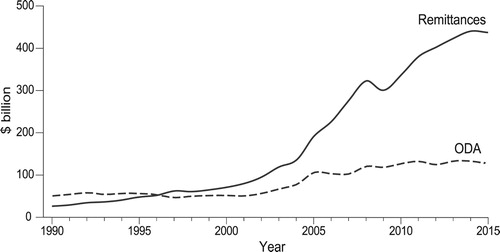

Source families generally hope that their financial support for their migrant family member's journey and settlement costs in the destination country will be compensated by remittance payments to the ‘left behind’ family members (Nurick and Hak's article on remittances between Thailand and Cambodia, Citation2019). World Bank statistics document a rising volume of remittances worldwide with the value of remittances superceding foreign aid from developed countries by the mid-1990s. shows migrants’ foreign remittances taking off in a period of stagnant foreign aid transfers, rising steeply, then briefly dipping during the 2008 global economic crisis. They regained momentum until starting to level off in 2014. Between 1990 and 2015, remittances increased more than 10-fold while aid transfers merely doubled in monetary value.

Figure 2. Remittance flows and overseas development aid to developing countries, 1990–2015. Source: World Bank (Citation2017).

While attention has been focussed on the material flow of money and goods, the emotional and physical care flows between sending and receiving branches, pivotal to transnationals’ physical and mental well-being as well as their sense of social purpose and identity, have been relatively overlooked.

Transnational family care regimes

‘Family care regimes’ encompass day-to-day nurturing and care of family members and family members’ evolving support roles during unfolding life cycle stages. Families everywhere are involved in negotiating a division of labour to provision their members’ care, but transnational families contend with a greater logistical challenge of physical separation. The need to find replacement childcare for absent parents, the possibility of high care dependency ratios and awkward delivery time frames frequently arise. Replacement carers may be family or non-family members serving in that capacity on a short or long-term basis, including peripatetic nuclear or extended family members, friends and family members who move in and out on a need basis. However, frequent mobile phone and internet contact and, when possible, regular home visits, can enable migrant parents to achieve a meaningful off-site care role.

Baldassar (Citation2007) delineates different categories of transnational family care flows: emotional, practical, financial support and accommodation and distinguishes two forms of delivery: either directly provisioned face-to-face assistance or indirect communication technology-mediated flows supplied over long distances. Kilkey and Merla (Citation2014) stress the variation in country-specific migration patterns, processes of transnational family formation, financial support and care exchange, which relate to the occupational categories of people emanating from the sending countries and receiving country's immigration laws. They refer to ‘care regimes’ whose form and content are shaped by needs exerted by source and destination branches of the family at specific stages of the life cycle, as well as the migrant status of absent members in the destination country. Despite wide-ranging contrasts, global similarities can be discerned based on common inter-generational dependency and interdependency patterns over the course of the family life cycle.

Baldassar and Merla (Citation2013, 25) use the term ‘circulation of care’ to refer to ‘reciprocal, asymmetrical and multi-directional exchange of care’. Such transnational family network care fluctuates over the family's life-course, conditioned by the sending and receiving societies’ economic, political, social and cultural contexts. Kilkey and Merla (Citation2014) adopt an institutional perspective, juxtaposing ‘state welfare regimes’ at a macro level, consisting of formal measures for providing fallback or supplementary care to families facing income shortfalls. This is related to the unevenness of opportunity in the labour market, as opposed to ‘family care regimes’ arising from micro level family-based arrangements for substitute care conditioned by the cultural setting and prevailing labour migration norms.

The context in which welfare and care regimes are gaining prominence relate to forces of labour demand and supply. Women's increased labour force participation in affluent countries exerts demand for female replacement labour as cleaners and child-minders. In these capacities, migrant women, offering their labour at a lower cost than nationals, are part of restructured neoliberal labour markets (Salih and Riccio Citation2010). Their migration leaves a void in their own families, filled by various family members performing maternal care responsibilities, including fathers, older siblings, grandparents and extended family members.

Such situations can emotionally disturb ‘left-behind’ children and create poignant consequences for child and family welfare (Lam and Yeoh, Citation2019). Women's migration decisions are generally premised on improving the long-term life chances of their children to gain a good education and well-paid occupation. But the absence of their mothers may give rise to children's resentment, and a reduction in the quality of family nurturing and marital tensions between women migrants and their stay-at-home carer husbands (Gamburd Citation2008).

Similarly, the absence of migrant fathers can result in children feeling estranged despite their fathers’ efforts to retain regular communications and the presence of grandparents and/or siblings. Poeze (Citation2019) notes that undocumented Ghanaian fathers, unable to make trips back and forth to Ghana to visit their left behind families, worried about failing to fulfil their social role as fathers. Their predicament dramatises the trade-off between the economic benefits of migrants’ remittances aimed at children's improved education and living standards, as opposed to the disbenefits of emotional barriers to spontaneously interacting face-to-face with their children.

Thus, both mothers and fathers face a migration paradox in which migration takes place for the purpose of improving children's economic welfare, but is often at the cost of children's emotional well-being (Lam and Yeoh, Citation2019). Furthermore, as parents separated from their children, both women and men experience extreme loneliness and alienation. A growing literature on emotional support transfers indicates the sometimes erratic or imbalanced nature of two-way emotional exchanges (Boehm Citation2012; Yeates Citation2012; Ariza Citation2014; Mahdavi Citation2016).

Significantly, family care exchanges are not necessarily based on close biological ties. Transnational family exchange and care relationships are established, maintained or curtailed in a selective process of ‘relativising’ whereby one's cherished family members, are those who succeed in negotiating an exchange of mutual benefit embedded in acceptable levels of dependence and interdependence (Bryceson and Vuorela Citation2002).

Transnational family care regimes vary widely to the extent that they can provide a sense of family coherence and effective care. Much has been written about the nature of remittance flows that depend on the migrant's earnings and ability to save and send remittances (Osella and Osella Citation2000; Riccio Citation2001; Goldin and Reinert Citation2012). Nurick and Hak (Citation2019) observe remittance-recipient Cambodian families generally view women migrants as more reliable and generous remitters.

The immigration of Poles to the United Kingdom exemplifies the desire for family coherence across borders. When Poland joined the European Union (EU) at the time of EU enlargement in 2004, Polish migrants were granted free entry in the UK, Ireland and Sweden. In the first years, most Polish migration to the UK consisted of young men who practised circular migration seeking to maximise their income for family investment in Poland. With the passage of time, families perceived detrimental effects on family life caused by locational separation, which spurred families’ applications for family reunion as EU nationals, catalysing Polish female migration. While some were job-seeking and readily found work in care industries, many seized the opportunity to become full-time mothers temporarily during the time when their children were young (Ryan et al. Citation2009).

Chain migration was also taking place as extended family members came for short-term visits and sometimes chose to migrate, when they discovered that they could readily find jobs. Frequent, often daily, mobile phone contact as well as regular visits at will with family in Poland afforded them a strong transnational perspective for making informed decisions. For many young Polish migrants, it was the freedom of being away from family in Poland that attracted them to the UK (Ryan et al. Citation2009). Nonetheless, mobile phones, skype and very frequent trips back to Poland imparted strength to family relations between sending and receiving countries.

By contrast, migrant women from Philippines, Indonesia, Ethiopia and Madagascar working as domestic cleaners and carers in Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates contend with many state-imposed barriers to their transnational family coherence. Most are young unmarried women shouldering responsibility for sending remittances to their families back home. As productive earners, they may be successful in sending back remittances to their family, but working in the confines of family homes, they are highly vulnerable to policing and punishment of their reproductive lives by their employers or the state. Mahdavi (Citation2016) observes that most women migrants in Kuwait and UAE are in their most fertile years, residing away from the familiarity of their homes and cultural norms for the first time, lacking awareness of strictures on romantic relationships in the Gulf States. In the event of an unmarried migrant woman becoming pregnant, she is in breach of her labour contract, charged with heavy fines and liable to lose her job. The migrant woman's plight is more serious if her work visa has lapsed. Her sexuality and motherhood is likely to be criminalised even in cases where her male employer or some other male member of the household has raped her (Mahdavi Citation2016, 45–46).Footnote4

The pivotal role of state immigration policies is apparent in the comparison of Poles’ experience of blurred borders in the UK as opposed to the Kuwaiti example of the exceptionally brittle borders migrant women face there. The next section delves further into how state immigration policies combine with family life cycles, generational exchange and migrants’ immigration status to shape transnational family welfare and development outcomes and in turn, how families perceive migration risks and what they do to obviate obstacles.

Transnational families enmeshed in blurred, brittle and broken borders

Nation-states enacting and implementing laws and regulatory policies concerning labour, foreign entry and exit, residence, citizenship and family reunification, vary in their exercise of control. This section restricts its coverage to an overview of how state immigration policies both shape and are affected by transnational family strategies.

A migrant-receiving state invariably prioritises the rights and welfare of its citizenry over that of migrants. If and when a national economy is deemed to need or benefit from specialised or additional labour from abroad, border policies allowing or encouraging the entry of economic migrants may be implemented, usually with the premise that the foreign labour must be flexible and retractable. A move from blurred to brittle borders can be sudden or protracted in nature, as evidenced by Nurick and Hak's case (Citation2019) of Cambodian migrant expulsion from Thailand as opposed to Martínez-Buján's case study of a more gradual blurred to brittle border transition with an unpredictable twist for some Bolivian migrants to Spain (Citation2019). Immigration policies can be altered rapidly whereas transnational family life cycles, care circulation and development strategies are usually less amenable to sudden alteration. Immigration policy changes can create far-ranging adverse and unforeseen implications. Migrants experience awkward or risky circumstances when their residential and labour rights are challenged or revoked and their livelihoods are placed in jeopardy.

In view of immigration laws’ complexity and variation from country to country, the following section provides a general overview of the tendency for advanced capitalist nations’ migration policies to transition from blurred to brittle borders over the last decade, and some of the implications for migrants and their transnational families.

Terms of nation-state entry

Individuals’ myriad reasons for crossing state borders and the proliferation of official categorisations of immigration status underpin the evolution of country-specific rules and regulations regarding border entry. Migrants’ immigration status delimits their livelihood and residential possibilities. While many have a carefully considered strategy for negotiating their immigration status, others are relatively unaware of the significance of their status, let alone knowledgeable about how to manage it. Those migrating from home countries with weak states to destination countries with strong states are most likely to not fully appreciate the formal definitive nature of their immigration status and the consequences of non-adherence to the law (Levitt and Glick-Schiller Citation2004).

Immigration status is an evolving process, contingent on the migrant's navigational manoeuvres. Some come as tourists or students and stay on to work either legally or illegally. Others attempt to remain after the expiry of their work contract. This is common in many Gulf States (Mahdavi Citation2016). Lapsed visa workers are generally hard to trace. Still others have entered without a visa and remain visa-less throughout their sojourn in a country. Many African migrants performing informal casualised work occupy this category and are not in a position to provide a unique, valued skill required to alter their undocumented status. Others with lapsed work visas also fall into the category of undocumented illegal migrants. In economic boom times, this category may reflect blurred border circumstances in which the government is lax about enforcing the full letter of its immigration laws. This is illustrated by the case studies of Cambodian migrants in Thailand (Nurick and Hak, Citation2019) and Bolivian migrants in Spain prior to the 2009 global economic crisis (Martínez-Buján, Citation2019).

In periods of actively enforced brittle border laws, undocumented migrants are ineligible for various public services and unable to travel to their country of origin with the certainty that they will be allowed to re-enter. Some feel compelled to ‘go underground’ indefinitely within the receiving country. Children of migrants born in a receiving country, where jus soli citizenship rights do not apply become stateless. In the US, where jus soli does apply, babies acquire American citizenship at birth and grow up there but their non-US citizen parents are always liable to deportation. If deported, such children, who have never been to Mexico and do not speak Spanish or know Mexican customs, accompany their parents to what is in effect a foreign country, if they have no guardians to stay with in the US (Boehm Citation2012; Cantú Citation2018).Footnote5

Evolving blurred, brittle and broken borders

Immigration regulations are influenced by the national economy of the country in question, its competitive market position and political concerns. During economic boom years, states and employers directly or indirectly seek to attract migrant labour and blurred boundaries prevail, offering porous, relatively easy entry for labour migrants either through liberal open entry laws or lax implementation of stringent migration regulations, affording migrants unofficial entry. More than physical barriers at national boundaries, border controls are essentially eligibility criteria for legal immigration based on migrants’ nationality, skills, and age.

Brittle borders, surfacing in times of economic crisis and political stress, are illustrated by Bianchera et al.’s (Citation2019) documentation of the internment of Welsh Italian men during World War II in Great Britain, as well as European Union border controls on the non-national Asians, Africans and Latin Americans described by Poeze (Citation2019), Martínez-Buján (Citation2019) and Fernandez (Citation2019).

Tightening border policies inevitably trigger migrants’ efforts to circumvent the barriers. By crossing borders without official documentation or overstaying their temporary visas, brittle state borders become broken borders a practice that can gain widespread incidence relatively quickly (Carr Citation2012; Harding Citation2012). In 2015, EU migration policy enforcement was unable to stem the entry of over 1.8 million migrants into the European Union by sea and land (Hagen-Zanker and Mallett Citation2016, 6; FRONTEX Citation2017).Footnote6 In the aftermath of the 2015 migrant crisis, rising numbers of undocumented migrants have been perceived as intolerable in scale and deleterious in nature by vocal segments of the general public in many EU countries.Footnote7 Migrants’ determination to reach their targeted destination countries vies against the hostility of anti-migrant segments of receiving country populations.

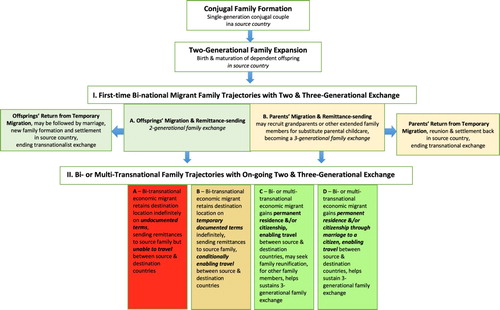

Within the destination country, migrants interact with the state during unfolding stages of their family life cycle and care regimes to gain access to work, residence and ultimately citizenship, alongside their felt need to remain in contact with the natal and conjugal families they left behind, or additional family members who may have migrated to other countries (Ariza Citation2014). schematises the family life cycle and intergenerational exchange across a spectrum of configurations, beginning with a single generational family with members locationally divided between source and destination countries. Over time this can ultimately expand to multi-generational families spanning two or more international borders (Wall and Bolzman Citation2014). The transition from bi- to multi-transnational families depends on the existence of restricting or alternatively incubating conditions conducive to family migration patterns, immigration/citizenship status in the destination country and life cycle progression through marriage and childbirth.

Figure 3. Evolution of transnational family life cycle and intergenerational exchange in relation to immigration status. Source: Author's depiction.

Multi-transnational families create homes and livelihood niches, forming networks of multiple locational nodes with family members sharing a common link back to the home country or ancestral homeland. Family exchanges between source and destination countries continue over time, but the exchange dynamic between branches of the family is likely to become less centred on the survival needs and development objectives of the source family members. Members in the destination country are liable to increasingly prioritise in situ investment in children's education and deepening cultural integration and class advance. The home country becomes a secondary point of reference, while destination family members gain a new hybrid identity as transnational expatriates or citizens spawning second and subsequent generations that are born and mature within the destination country context.

The flow of family exchange and care circulation between source and destination countries continues but often with reduced volume and new functions, such as holiday visits and house acquisition back in the home country, reflecting elevated standards of living and a transnational nostalgia for family roots, as illustrated in Bianchera et al.'s case study of Welsh-Italians (Citation2019). When there are no children or generational progression, migrants nonetheless often remain emotionally attached to the cultural influence of their home country. Fernandez (Citation2019) documents how Cuban migrant husbands in Scandinavia emphasised their Cuban heritage in their work life as musicians, which paradoxically afforded them international mobility given the global popularity of salsa music. Welsh-Italian ice cream and coffee shop owners similarly stressed their Italian origin, consumer products which were appreciated by their Welsh clientele.

Above all, the emergence of multinational families, their economic security rests on state legitimisation of family members’ presence in the form of long-term visas or citizenship. Residential stability and work security are essential to transnational family development strategies. The complexity of migration status can be reduced to three basic differences: first, those holding a legitimate documented status granting them secure residence or citizenship (green boxes, ). Second, migrants with the expectation of future security awaiting legitimacy of their visa or citizenship applications (yellow box). Third, those locked into undocumented, covert residence, denied citizen or denizen status, working in illegal casualised jobs, without access to social services, often living in fear of detection and deportation (red box). The world economy is premised on inequality and political division. Economic migrants from poor countries are frequently viewed as a political threat to the welfare state and western liberal democracy, a drain on existing taxpayers in the receiving country and usurpers of national citizens’ jobs in many countries.

By contrast, educated migrants from affluent post-industrial countries associated with high salaried income, tax revenue or investment are likely to be welcomed and offered special financial lures. Non-citizen expatriates are expected to return to their home countries after their work contracts expire. But there is another route to legitimacy and economic success. Some children from low-income migrant backgrounds may excel at school in their destination country and successfully climb the occupational ladder into well-paid professional jobs as adults, depending on the nature of state migration policies and migrant access to educational services.

Migration statistics are notoriously unreliable, given the difficulty of keeping administrative records on border entry and exit. The receiving country may be drawn into a vortex of hardening migration controls. Brittle borders become broken borders as more migrants seek entry or over-stay their visas generating a visible presence of mounting numbers. Unease in the political economy of the country is mirrored in the lives of undocumented migrants, some experiencing fractured intra-familial relationships within their bi-transnational families associated with their visa-less status, difficulty in sending remittances and making return visits to their home countries.

Transnational families, the global labour market and nation-states dynamics: case study insights

This Introduction has explored twenty-first century temporal and spatial patterns of transnational families’ global migration from the perspective of bi- and multi-transnational family agency, spanning poor countries of origin and more affluent destination countries where select family members have settled for economic betterment for themselves and their families. The case studies in this Special Issue trace migration from Asia, Africa and Latin America to Europe, the Middle East and Singapore, with focus on aims and quandaries embedded in choices regarding which family members migrate, where and when, and how subsequent transnational family formation and needs are reconciled over the course of the family life cycle and beyond to the next generation.

The articles afford insights into the dynamics of migration decision-making in a wide spectrum of sending and receiving countries amidst the booms and busts of the global market and the erratic border policies of receiving countries. The formal and informal pathways migrants’ traverse in search of viable livelihoods, their remittance-sending capability and means of retaining contact with ‘stay behind’ family members and their efforts to enhance family welfare and, in some cases, gain family reunification form the core of transnational family aims.

Miranda Poeze charts the differences between Ghanaian documented and undocumented migrant men's scope for retaining emotional contact with their Ghanaian-based children while living in the Netherlands. Migrants with an undocumented status face a double bind in which working abroad to provide enhanced material support for their children and wives can generate a communication barrier and emotional gulf between fathers and their families.

Theodora Lam and Brenda Yeoh explore how Indonesian and Filipino children adjust to their mothers or fathers working abroad and how they attempt to sway their parents’ decisions about long-distance contract work. These are bilateral transnational families where the father or mother is working to improve the family's living standards and the educational opportunities of their children. Parents contend with the emotional distancing that surface as children grow up without their parents’ daily physical presence.

Raquel Martínez-Buján probes the quandaries of economic migrants from Bolivia who became embroiled in the 2008 global economic crisis in Spain. The dilemma of choosing to return home to Bolivia or stay in Spain in the face of uncertainties of livelihood and Spanish immigration policies weighed heavy on relational ties within these bi-transnational families. Surprisingly, many who stayed gained Spanish citizenship, making flexible family visiting between Spain and Bolivia possible.

Robert Nurick and Sochanny Hak document how impoverished Cambodian rural peasant households rely on young family members to seek non-farm earning opportunities across the border in Thailand's more buoyant economy. Unexpectedly caught in the sudden political mayhem of a military coup in Thailand in 2014, all undocumented migrants were ordered to leave the country. The financial cost of their return and the forfeiture of their ability to continue sending remittances home posed a threat to the economic viability of poor Cambodian rural family farms.

Nadine Fernandez presents the case of Danish female tourists’ romantic holiday involvement with Cuban male musicians, leading to some Cuban men migrating to Scandinavia. Danish feminism and Cuban patriarchy were played out in various forms of bi-transnational cohabitation, marriage and family formation. In the event of marital breakdown or job loss, the Cuban men could temporarily fall back on the Danish welfare state precluding reliance on family support from Cuba – an intriguing contrast to the Cambodian workers fleeing from Thailand to their natal homes empty-handed.

Finally, Emanuela Bianchera, Robin Mann and Sarah Harper chart a timeline of inter-generational change in Italian migrant families who migrated to Wales in the late nineteenth century. Over multiple generations, families have retained circular migration links with Bardi, their Italian ancestral homeland, where many have second homes. Furthermore, some bi-transnational families have become multi-transnational families with branches of the family in other countries, representing three or more intra-familial national cultural traditions.

Transnational family networks’ agency begins with individual migrants venturing abroad in pursuit of family welfare enhancement. The journey can be confidence-building, soul-destroying or both. The migrant derives rewards from finding work, earning sufficiently to purchase daily needs, saving and sending remittances home, but when work is not forthcoming, friendship, collegiality, finding love and intimacy have less chance of being achieved. In addition to the economic journeys migrants traverse, migration poses a potential minefield of emotional turmoil involved in retaining meaningful contact with one's family back home (Cantú Citation2018). Meanwhile the migrant must navigate socially in a foreign culture where social norms may starkly contrast with what prevails in one's home country (Donnan and Wilson Citation2001).

As productive and reproductive decision-making units, transnational families cohere through physical, economic and social needs provisioning during the family life cycle from cradle to the grave. The initial family member who migrates abroad may hope to trail blaze, opening up possibilities for new sources of income and resource access. Such ventures align with bifurcated outcomes: (1) either the migrant returns after a fixed contractual period and resumes in situ membership in the family within the source country, while the legacy of the out-migration is considered to be a net benefit or loss to the family (Åkesson and Baaz Citation2015); or (2) the migrant stays in the destination country and becomes part of an on-going process of material and emotional exchange between source and destination branches of an evolving transnational family engaged in greater or lesser degrees of remittance-sending, cross-border care circulation and bridged welfare provisioning. In the event of fluctuating national economic booms and recessions, economic migrants struggle with the unpredictability of labour opportunities and hazards, and may be compelled to make unplanned returns to their home country where they are likely to face lower economic returns and labour market uncertainty (Martínez-Buján, Citation2019; Nurick and Hak, Citation2019).

Transnational family formation and extension encompasses multiple migration options: chain migration from the source country, branching family networks in different places abroad, marriage and childbirth of the migrant to someone back in the source country who migrates on the basis of family reunification, or marriage of the migrant to a national of the destination country. Bi- and multi-transnational networks ensue, which involve dual or multiple cultural identities, citizenships and varying degrees of adaptation to the destination country. There is no single, unilinear course of transnational family formation and expansion.

Conclusion: transnational families’ welfare quest versus nation-state censure

Transnational families evolve on the basis of their own investments in one or more family members’ migration and efforts to retain direct communications with each other and actively engage in material and emotional exchange underlined by a sense of care and concern for one another. Some thrive whereas others abandon their cross-border family ties over the course of generational progression. But certainly, where there is a willingness to pursue ties, twenty-first century digital technology and rapid transport development have greatly facilitated transnational family communication.

The current surge in international migration represents mounting numbers of families with household members responding to global inequality by venturing abroad in search of better opportunities. The massive scale of decentralised family decision-making entailed in members’ departure to distant countries is accompanied by migrants’ willingness to endure enormous uncertainty and hardship crossing international borders and finding livelihoods in receiving countries. Their migration journeys tend to be family rather than individual risk strategies.

A migrant entry and transnational family formation have increasingly attracted censure in destination nation-states. Segments of the citizenry in the more affluent countries are contesting their countries’ migration policies, making governments defensive and prone to tightening their borders to become brittle borders that ‘break’, thereby increasing the numbers of undocumented migrants living in alienating conditions. Resentful national citizens have turned to support of populist leaders propagating xenophobic attitudes. Adverse consequences follow for transnational families’ endeavouring to retain family coherence and welfare across source and destination countries.

Ironically, many nation-states, who have benefited the most from global liberalised markets over the past three decades, are seeking distance from the global market, scaling down and delimiting their national economy alongside tightening border controls. Other states remain committed to the on-going liberal challenge of mutual trade and welfare between nation states, expanding their national economies on the principles of a relatively unimpeded flow of commodities, capital and labour.

The odds are that nation-states, attempting to block rather than bridge the operation of fluid global labour markets and family life cycle care, are on the losing side of history. In the institutional interplay between markets, states and transnational families, the convergence of global market forces channelling people worldwide into twenty-first century work occupations and transnational families’ efforts to develop materially constitute a creative and welfare-enhancing trajectory for their families’ futures as well as the nation-states that they originate from and the destination states where they reside and work. It remains to be seen if centralised nation-states, operating primarily on the basis of twentieth century power politics and social divisions, can recalibrate and contribute to a more viable institutional synergy between markets, states and transnational families.

There is a widening gulf between transnational families’ decentralised strategies and centralised state policy-making in destination countries. The crisis of family welfare that afflicts poorer nations of the world has become a crisis of the nation-state both in sending and receiving countries. Global inequalities underpin the world's political fault lines and conflict zones. The surge in transnational families’ remittances, care and welfare distributive efforts across state borders are flexibly and pervasively mediating welfare gaps between nation-states. Yet states, subject to centralised migration policies and delimited national regulation, defensively tighten their borders.

Paradoxically, issues of national sovereignty and control are pitted against transnational family welfare and economic development in a world becoming more globally connected through technological advance in communication and forms of travel. Meanwhile, the predilection to migrate from materially poor to affluent countries will persist as long as average income gaps between the two remain so immense.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Belinda Bantje, Paul Clough, Anne Coles, Sian Crisp, Maurice Herson, Marek Kaminski, Judith Okely, Najma Sachak and Jill Shankleman for their willingness to comment on drafts of this paper. I bear full responsibility for the contents of this article.

Disclosure statement

There is no potential conflict of interest.

Notes

1 Weiner (Citation1995) already referred to a ‘migrant crisis’ 20 years earlier. Use of the term ‘migrant’ generally encompasses ‘economic migrants’ and ‘refugees’. Often, there is a hazy line been economic migrants and refugees, who tend to be designated primarily on the basis of their country of origin. ‘Refugees’ flee in fear of physical harm or psychological torture from war-torn countries or as political outcasts, whereas ‘economic migrants’ opt for better economic prospects from more politically stable countries. However, refugees become relatively indistinguishable from economic migrants in terms of preferring settlement and employment in affluent destination countries. They compete with economic migrants for work opportunities. Overtime their concerns increasingly merge with those of economic migrants.

2 Details of the qualitative and mixed qualitative/quantitative methods they chose to deploy are detailed in the articles.

3 In relation to international migration in East and Southeast Asia see Yeoh, Huang, and Lam (Citation2005). Douglass (Citation2006) uses the term ‘global householding’ to refer to a household's geographically extended social reproduction induced by a family member's international migration.

4 Regardless of her religion, she can be charged with zina (sex outside of marriage) and deemed to be an unfit mother, who faces imprisonment, separation from her child and deportation. Many migrant women have had to give birth while gaoled. Mahdavi (Citation2016) documents that a baby born to an unmarried non-citizen mother in Kuwait will be stateless and not allowed to leave the country. If the father is a national but refuses to marry and acknowledge paternity of the child, the child will be placed in a state orphanage, and grows up motherless and stateless. See Kaminski (Citation2012) for an analysis of parents’ turmoil in dealing with the resolution of their children's statelessness.

5 In 2014, President Obama, in a move to provide residential stability to such migrant families, controversially declared that illegal migrant parents with children who are American citizens will not be deported and inversely Mexican children who came to the US illegally to join parents with US citizenship were to be allowed a temporary legal status (Time Politics, 20 November 2014). In June 2016, this presidential directive was blocked by a tied Supreme Court decision (CNN Politics, Edition.ccn.com) putting families of mixed citizenship back at risk of deportation. Six months later, Trump's presidency began with his pledge to construct a full border-length wall between the US and Mexico, intensifying the brittleness of the border and renewed efforts to deport the so-called ‘dream children’.

6 2015 EU data shows an inflow of 1,898,472 migrants, of which 70% were from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq. ‘Economic migrants’ were assumed to constitute the remaining 30% (567,842), coming mainly from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Iran, Russia, Ukraine, Albania, Morocco, Gambia, Senegal, Nigeria, Sudan, Eritrea, Somalia.

7 In June 2016, a 52% majority of the voting public in the UK's EU referendum voted to leave the EU, largely on the grounds that stricter control and policing of immigration was needed. Trump's election to the American presidency was widely credited with his election promise to build a wall between Mexico and the United States. Levels of foreign migration were contested during national elections in Germany, The Netherlands, France, the United Kingdom, Germany, Austria and Italy during 2017–2018.

References

- Åkesson, L., and M. E. Baaz. 2015. Africa’s Return Migrants: The New Developers? London: Zed.

- Andersson, R. 2014. Illegality, Inc.: Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Ariza, M. 2014. “Care Circulation, Absence and Affect in Transnational Mothering.” In Transnational Families, Migration and the Circulation of Care: Understanding Mobility and Absence in Family Life, edited by L. Baldassar, and L. Merla, 94–114. New York: Routledge.

- Baldassar, L. 2007. “Transnational Families and Aged Care: The Mobility of Care and the Migrancy of Ageing.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33 (2): 275–297. doi: 10.1080/13691830601154252

- Baldassar, L., and L. Merla. 2013. Transnational Families, Migration and the Circulation of Care: Understanding Mobility and Absence in Family Life. London: Routledge.

- Bianchera, E., R. Mann, and S. Harper. 2019. “Transnational Mobility and Cross-Border Family Life Cycles: A Century of Welsh-Italian Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (16): 3157–3172. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1547026.

- Boehm, D. 2012. Intimate Migrations: Gender, Family, and Illegality among Transnational Mexicans. New York: New York University Press.

- Bryceson, D., and U. Vuorela. 2002. The Transnational Family: New European Frontiers and Global Networks. Oxford: Berg Press.

- Cantú, F. 2018. The Line Becomes a River. London: Penguin Random House UK.

- Carr, M. 2012. Fortress Europe: Inside the War Against Immigration. London: C. Hurst and Co.

- Charsley, K. 2005. “Unhappy Husbands: Masculinity and Migration in Transnational Pakistani Marriages.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11 (1): 85–105. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9655.2005.00227.x

- Chayanov, A. 1966 [1925]. The Theory of the Peasant Economy. Translated by D. Thorner, R. E. F. Smith, and B. Kerblay. Glencoe, IL: Irwin.

- Clough, P. 2018. “The Ethics of Alterity and the Language of the Divine in the Discourse and Economic Trajectories of West African Irregular Immigrants in Malta.” In Social Well-Being: New Pathologies and Emerging Challenges, edited by D. Napier, A. Hobart, and R. Muller. Herefordshire, UK: Sean Kingston.

- de Jong, G., and D. Graefe. 2008. “Family Life Course Transitions and the Economic Consequences of Internal Migration.” Population, Space and Place 14 (4): 267–282. doi: 10.1002/psp.506

- de Jong, G., B. Root, R. Gardner, J. Fawcett, and R. Abad. 1985. “Migration Intentions and Behavior: Decision Making in a Rural Philippine Province.” Population and Environment 8 (1): 41–62. doi: 10.1007/BF01263016

- Donnan, H., and T. Wilson. 2001. Borders: Frontiers of Identity, Nation and State. Oxford: Berg.

- Douglass, M. 2006. “Global Householding in Pacific Asia.” International Development Planning Review 28 (4): 421–446. doi: 10.3828/idpr.28.4.1

- Epstein, G., and I. Gang. 2006. “The Influence of Others on Migration Plans.” Review of Development Economics 10 (4): 652–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006.00340.x

- Faist, T. 2000. “Transnationalization in International Migration: Implications for the Study of Citizenship and Culture.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 23 (2): 189–222. doi: 10.1080/014198700329024

- Fernandez, N. T. 2019. “Tourist Brides and Migrant Grooms: Cuban–Danish Couples and Family Reunification Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (16): 3141–3156. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1547025.

- FRONTEX, European Border and Coast Guard Agency, 2017. Accessed November 6, 2017. http://frontex.europa.eu/news/fewer-migrants-at-eu-borders-in-2016-HWnC1J.

- Gamburd, M. 2008. “Milk Teeth and jet Planes: Kin Relations in Families of Sri Lanka’s Transnational Domestic Servants.” City & Society 20: 5–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-744X.2008.00003.x

- Goldin, I., and K. Reinert. 2012. Globalization for Development: Meeting New Challenges. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hagen-Zanker, J., and R. Mallett. 2016. “Journeys to Europe: The Role of Policy in Migrant Decision-Making.” ODI Research Report, February 2016.

- Harding, J. 2012. Border Vigils: Keeping Migrants out of the Rich World. London: Verso.

- Haug, S. 2008. “Migration Networks and Migration Decision-Making.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (4): 585–605. doi: 10.1080/13691830801961605

- Ifekwunigwe, J. 2013. “‘Voting with Their Feet’: Senegalese Youth, Clandestine Boat Migration, and the Gendered Politics of Protest.” African and Black Diaspora: An International Journal 6 (2): 218–235. doi: 10.1080/17528631.2013.793139

- Ishii, S. 2016. Marriage Migration in Asia: Emerging Minorities at the Frontiers of Nation-States. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Kaminski, I.-M. 2012. “Identity without Birthright: Negotiating Children’s Citizenship and Identity in Cross-Cultural Bureaucracy.” In Learning from the Children: Childhood, Culture and Identity in a Changing World, edited by J. Waldren, and I.-M. Kaminski, 146–169. Oxford: Berghahn.

- Kilkey, M., and L. Merla. 2014. “Situating Transnational Families’ Care-Giving Arrangements: The Role of Institutional Contexts.” Global Networks 14 (2): 210–229. doi: 10.1111/glob.12034

- Lam, T., and B. S. A. Yeoh. 2019. “Parental Migration and Disruptions in Everyday Life: Reactions of Left-Behind Children in Southeast Asia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (16): 3085–3104. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1547022.

- Levitt, P., and N. Glick-Schiller. 2004. “Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society.” International Migration Review 38 (145): 595–629.

- Lievens, J. 1999. “Family-Forming Migration from Turkey and Morocco to Belgium: The Demand for Marriage Partners from the Countries of Origin.” International Migration Review 33 (3): 717–744. doi: 10.1177/019791839903300307

- Mahdavi, P. 2016. Crossing the Gulf: Love and Family in Migrant Lives. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Martínez-Buján, R. 2019. “Here Or There? Gendered Return Migration to Bolivia from Spain during Economic Crisis and Fluctuating Migration Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (16): 3105–3122. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1547023.

- Massey, D., J. Arango, G. Hugo, A. Kouaouci, A. Pellegrino, and J. E. Taylor. 1993. “Theories of International Migration: A Review and Appraisal.” Population and Development Review 19 (3): 431–466. doi: 10.2307/2938462

- Mazzucato, V., D. Schans, K. Caarls, and C. Beauchemin. 2015. “Transnational Families between Africa and Europe.” International Migration Review 49 (1): 142–172. doi: 10.1111/imre.12153

- Moberg, V. 1951. The Emigrants. London: Penguin Books.

- Nurick, R., and S. Hak. 2019. “Transnational Migration and the Involuntary Return of Undocumented Migrants across the Cambodian–Thai Border.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (16): 3123–3140. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1547024.

- Olwig, K. F. 2007. Caribbean Journeys: An Ethnography of Migration and Home in Three Family Networks. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Osella, F., and C. Osella. 2000. “Migration, Money and Masculinity in Kerala.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 6 (1): 117–133. doi: 10.1111/1467-9655.t01-1-00007

- Poeze, M. 2019. “Beyond Breadwinning: Ghanaian Transnational Fathering in the Netherlands.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (16): 3065–3084. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1547019.

- Riccio, B. 2001. “From ‘Ethnic Group’ to ‘Transnational Community’? Senegalese Migrants’ Ambivalent Experiences and Multiple Trajectories.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27 (1): 583–599. doi: 10.1080/13691830120090395

- Riccio, B. 2008. “West African Transnationalisms Compared: Ghanaians and Senegalese in Italy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (2): 217–234. doi: 10.1080/13691830701823913

- Robinson, K. 1996. “Of Mail-Order Brides and ‘Boys’ Own’ Tales: Representations of Asian-Australian Marriages.” Feminist Review 52: 53–68. doi: 10.1057/fr.1996.7

- Ryan, L., R. Sales, R. M. Tilki, and B. Siara. 2009. “Family Strategies and Transnational Migration: Recent Polish Migrants in London.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (1): 61–77. doi: 10.1080/13691830802489176

- Salih, R., and B. Riccio. 2010. “Transnational Migration and Rescaling Processes: The Incorporation of Migrant Labor.” In Locating Migration: Rescaling Cities and Migrants, edited by N. Glick-Schiller, and A. Caglar, 123–142. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Skrbiš, Z. 2008. “Transnational Families: Theorising Migration, Emotions and Belonging.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 29 (3): 231–246. doi: 10.1080/07256860802169188

- van Dijk, R. 2002. “Religion, Reciprocity and Restructuring Family Responsibility in the Ghanaian Pentecostal Diaspora.” In The Transnational Family: New European Frontiers and Global Networks, edited by D. Bryceson, and U. Vuorela, 173–198. Oxford: Berg.

- Vuorela, U. 2002. “Transnational Families: Imagined and Real Communities.” In The Transnational Family: New European Frontiers and Global Networks, edited by D. Bryceson, and U. Vuorela, 63–82. Oxford: Berg.

- Wall, K., and C. Bolzman. 2014. “Mapping the New Plurality of Transnational Families: A Life Course Perspective.” In Transnational Families, Migration and the Circulation of Care, edited by L. Baldassar, and L. Merla, 61–77. New York: Routledge.

- Weiner, M. 1995. The Global Migration Crisis: Challenge to States and Human Rights. New York: Harper Collins.

- World Bank. 2017. Migration and Remittances Factbook 2016. Accessed 13 March 2018. http://www.worldbank.org/en/news/infographic/2017/04/21/trends-inmigration-and-remittances-2017

- Yamaura, C. 2015. “Marrying Transnational, Desiring Local: Making “Marriageable Others” in Japanese–Chinese Cross-Border Matchmaking.” Anthropological Quarterly 88 (4): 1029–1058. doi: 10.1353/anq.2015.0046

- Yeates, N. 2012. “Global Care Chains: A State-of-the-Art Review and Future Directions in Care Transnationalization Research.” Global Networks 12 (2): 135–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2012.00344.x

- Yeoh, B., S. Huang, and T. Lam. 2005. “Transnationalizing the ‘Asian’ Family: Imaginaries, Intimacies and Strategic Intents.” Global Networks 5 (4): 307–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2005.00121.x