ABSTRACT

We advance a concept of political remittances that offers a distinct analytical perspective and enables a comparative assessment across time and space. By providing a new conceptualisation of political remittances, this article elaborates on the link between different kinds of remittances, delimiting the boundaries between political, social, economic, or cultural remittances. We understand political remittances as influencing political practices and narratives of belonging, thereby linking migrants’ places of destination and origin. The state, in this conceptualisation, mediates political remittances. The article distinguishes between factors influencing the transmission of political remittances such as the characteristic of the messengers, the relative space between sending and receiving contexts and the composite nature of political remittances. Illustrating the contours of a future research agenda, we suggest ways to operationalise research into political remittances drawing on the articles in this special issue which closely analyse political practices, narratives of belonging and the role of the state. Covering migration processes since the early 1800s, the case studies exemplify that political remittances are not a new phenomenon as such but rather a relatively recent analytic perspective.

1. Introduction

Questions about the newness of transnationalism have generated heated debates between historians and sociologists. The dialogue on the political dimension of cross-border flows undertaken in this special issue requires us to historicise the guiding assumptions of transnationalism. It moreover challenges us to assess how new the political dimension of cross-border exchange is and to determine what the concept of political remittances adds to the analysis of transnationalism. The introduction aims to addresses key questions that have remained conceptually and empirically underexplored. (1) What kinds of political remittances have existed historically and at present? How have they changed over time? (2) What are the main channels for the transmission of political remittances? (3) What are the individual characteristics and structural conditions under which migrants remit politically? (4) What is the impact of political remittances on home and host societies?Footnote1

Through this special issue with articles covering two centuries of migration in various spaces, it becomes clear that political activities crossing borders have certainly intensified over time but that important spikes in these activities caused by the international political environment, economic conditions or major cultural events, have existed in the past. Covering migration since the early 1800s, the articles in this issue exemplify how much the phenomenon of transnationalism is itself a historically contingent occurrence tied to specific political circumstances.

In this introduction, we develop and probe a new definition of political remittances building on historical evidence and theoretical work that has been developed since the emergence of the original concept of social remittance (Goldring Citation2004; Lacroix, Levitt, and Vari-Lavoisier Citation2016; Levitt Citation1998; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Tabar Citation2014). We suggest defining political remittances as the act of transferring political principles, vocabulary and practices between two or more places, which migrants and their descendants share a connection with. Political remittances are remoulded in a context of migration, and can, in turn, influence political behaviour, mobilisation, organisation and narratives of belonging in places of destination and origin. The state and state-like agencies act as transversal actors who influence the content of political remittances through various immigration, integration, emigration or diaspora policies. However, our conceptualisation emphasises that political remittances need to go beyond the nation-state as the sole reference point and questions the prevailing tendency of analysing migration from the receiving end, especially in migration scholarship rooted in the integration literature. We contend that political remittances should be rather seen as including multidirectional flows of political ideas and practices influenced by conditions in sending and receiving places. Senders of remittances can be migrants and their descendants, as well as non-migrants in places of origin. Finally, we insist on the transformative potential of political remittances to countervail normative implications of the democratising impact of remittances.

A first section contextualises the kinds of political remittances that have existed historically and at present and illustrates how a historical perspective can advance migration studies. In a second section, we carve out political remittances as a distinct concept and suggests ways to operationalise the concept. We delimit the boundaries between political, social, economic, and cultural remittances, elaborate on transmission mechanisms and distinguish between different forms of content and different types of flows. The introduction then discusses the transformative impact of political remittances and reflects on intervening factors influencing their transmission and reception. A third section introduces the individual papers of the special issue.

2. The historic depth of transnationalism

Regarding the newness of transnationalism, unsurprisingly, historians found continuities where sociologists saw primarily ruptures. One central problem in this debate, as Waldinger and Green emphasise, is that the frequently made opposition between ‘now’ and ‘then’ is trivial as these two points of temporal reference remained oftentimes unspecified (Citation2016, 1). The entry point of the terminology of transnationalism into migration scholarship clearly bears its imprint from the expanding global markets and political exchanges towards the end of the Cold War. Indeed, Glick Schiller, Basch and Blanc-Szanton rooted transnationalism in the expanding global capitalism of the 1990s (1992, 5), an assumption many scholars have shared. Portes postulates that ‘present’ transnationalism is a distinct phenomenon which necessitates a new concept, justified by referring to the number of people involved, the instantaneous character of communication and the fact that participation has become normative within certain immigrant groups (Citation1997, 813). Later writings have echoed such assumptions about the distinctiveness of the present with regard to transnationalism (Itzigsohn Citation2000; Levitt Citation2001; Meissner and Vertovec Citation2015; Tarrow Citation2005).

A wealth of historical information underlines, however, that migration and the cross-border exchanges it creates, including significant ethnic diversity (Ostergren Citation1998), have existed before ‘modern’ times (Lucassen and Lucassen Citation2009). Moreover, the rates of technological change hardly correspond to the dates which social scientists evoke to chart the expansion of transnationalism. While technological change has beyond a doubt contributed to an accelerated and intensified transnational exchange (Brinkerhoff Citation2009), transnationalism as a structural phenomenon, however, has characterised migration for the last 200 years at least. Meanwhile, features such as the role of migrant networks for facilitating emigration or the arrival in the place of residence have remained constant (Krawatzek and Sasse Citation2019b).

In particular, moments of political upheaval saw the increase of transnational political activity. Migration waves in the aftermath of revolutions such as 1789, 1848 or 1917 were crucial for spreading diverse political views across Europe and further afield. The French revolution of 1789 caused the exile of about 150,000 people and some became key political players – the aristocracy in exile for instance had the resources and skills to mobilise influential political allies against the revolutionary regime in their host societies (Pestel Citation2017). The importance of diffusion through migration and transnational communication channels has similarly been emphasised for the European revolutions of 1848 (Weyland Citation2009) or in the context of mass migration of Jews fleeing Russia to the US or Britain at the end of the nineteenth century (Kadish Citation1992). As today, the social embedding of revolutionaries was important to transfer political practices and ideas. Vernitski (Citation2005), for example, underlines the contacts and flows of ideas between Olive Garnett, a middle-class London Bloomsbury writer, and Sergei Mikhailovich Kravchinski, a Russian revolutionary associated with the Social Revolutionary ‘populist’ movement for helping to set up socialist meetings or participating in strikes in the 1880s and 1890s.

We thus share the assumption that transnationalism is not a new phenomenon but instead a relatively recent perspective (Levitt and Glick Schiller Citation2004; Portes Citation2003, 874). However, the question arises as to whether the term transnationalism is then appropriate to explore different forms of migrants’ cross-border activities and grasp their variation over time. Indeed, we suggest that to assess the relative changes over time requires a concept that can grasp the empirical differences over time and in diverging political contexts.

2.1. Transnationalism beyond the state?

Integral to definitions of transnationalism is the pivotal role played by the state, usually conceptualised as a bounded political entity. Even if transnationalism emphasises that political activities span political borders, inherent to the transnational is a focus on the sending and receiving states as key actors and targets (Østergaard-Nielsen Citation2003, 762). However, this state-centeredness strikes us as misleading for a flexible understanding of the political flows between ‘here’ and ‘there’ that takes into account the interpretive frames that migrants themselves use to make sense of their cross-border activities. Migrants’ transnational political activities potentially change the political institutions in each respective space as well as the relationship between the two.

The term transnational might thus be misleading as it is refers to one specific, historically contingent constellation of cross-border activities (Green Citation2011). Frequently, when looking at transfers between migrants and family or friends ‘back home’ in the past, it is not the national frame which turns out to be the most relevant, but instead some smaller, more tangible unit (White Citation2011). In both, past and present, the reference points of political spatiality are not restricted to the nation, but include local, supranational or religious places. Therefore, we talk about places of origin and destination. The cross-border political activities of migrants have challenged the meaning of state borders themselves as the example of Kurdish diaspora lobbying demonstrates (Østergaard-Nielsen Citation2000). The political practices of migrants hence need not necessarily recur to the state, defined over territory, nor the nation, as an imagined community (Bauböck Citation2003, 702). That the state plays a central role should not be part of our assumptions but of the investigation.

Increasingly, migration scholars have paid attention to the influence on migration by sending states or state agencies. Since the middle of the nineteenth century, states have politically engaged their diasporas as shown by research on Mexico (Délano Citation2011), Italy (Choate Citation2007) or Bismarck’s Germany (Manz Citation2014) and through comparative or synthesising studies (Délano and Gamlen Citation2014; Gamlen Citation2008; Meseguer and Burgess Citation2014). Moreover, regional or other organisations also play a role in shaping transnationalism. Cities have for instance formed the transnational self-identification of migrants as a study of Senegalese migrants in Italy illustrates (Sinatti Citation2006). Empirical work on the Coptic Patriarchate in Egypt (Haddad Citation2013) or religious centres of learning such as the Shia ḥawza in Najaf in the early twentieth century (Younes Citation2012) and regional political institutions such as the Kurdish Regional Government in Iraq (Østergaard-Nielsen Citation2000) testify to the need to move beyond the national. Indeed, such a focus on religious institutions as transnational actors leads Bruce to use the concept of transnational religious fields in this special issue (Citation2020).

What we aim at capturing with the concept of political remittances is indeed much more akin to approaches which historians have used to identify cross-relations between, but also below or above the nation. The expanding literature on global history (Mazlish and Buultjens Citation1993; Osterhammel Citation2014), perspectives emphasised by histoire croisée (Werner and Zimmermann Citation2004), Verflechtungsgeschichte (Becker Citation2004) or entangled history (Lepenies Citation2003) draw attention to questions of political transfers beyond comparing distinct cases (Kocka Citation2003). Heuristically, these methods share an inductive approach to apprehending their object of study. Instead of assuming that social and political processes take place within clear borders, these methodological perspectives take as their starting point the relationships which actors establish between different spaces which can be on the level of the nation, the region, the local, or a combination.

The emphasis on croisements within histoire croisée shares conceptual similarities with what we analyse in this issue as political remittances. In our conceptualisation, migrants are the agents who carry political remittances and by implication, research into political remittances is not confined to identifying the transmitting structures. Instead, political remittances are a grassroots phenomenon which rely on but are not equal to cross-border networks (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998). The degrees of croisements vary, following ebbs and flows of migration over time and between actors.

A study of migration and exile benefits from such a historical perspective as it is not solely the national embedding structure which is necessarily the main point of reference for migrants but rather the flows between ‘here’ and ‘there’. Such a perspective shares similarities with the concept of ‘transnational social spaces’ or ‘transnational social fields’ which denotes the spaces that cross international borders and which constitute frames of reference for migrants and their activities (Basch, Glick Schiller, and Blanc-Szanton Citation1994; Faist Citation2000; Glick Schiller, Basch, and Blanc-Szanton Citation1992; Vertovec Citation2009; Wimmer and Glick Schiller Citation2002). For all of these authors, the most important element has been elaborating a perspective that encompasses the lived reality of migrants. However, delimiting these transnational fields (or spaces) becomes a major theoretical and analytical challenge once state borders are no longer taken as given – a perspective which historically informed research encourages.

The focus on the transnational bears itself the imprint of methodological nationalism which continuously haunts migration scholars (Glick Schiller Citation2009; Wimmer and Glick Schiller Citation2002). But to assess the newness of our current times we should move beyond conceptualisations which are too narrowly rooted in the present. Through a historical comparison, we can most effectively contribute to successfully overcoming the limits of methodological nationalism. For this reason, we refrain from using the concept of political transnationalism for the present set of case studies. Although the term political transnationalism, if sufficiently specified, might be perfectly appropriate for particular case studies, we seek to focus on the changing forms of political participation across borders, for which the conceptual perspective developed in the following section proves to be more helpful.

2.2. Political remittances beyond transnationalism

The preceding discussion raises the question of how to think about migrants’ activities in the realms of private and public. We contend that acts of migration are inherently political and that even decisions which at first sight appear private may actually have profound political implications for sending and receiving places and their respective political systems. In other words, private actions, family and friendships abroad, can have public effects at one’s place of origin. Looking for instance at the case of German migration to the United States throughout the nineteenth and until the middle of twentieth century, it is telling that what appears at first sight like a private act, sending letters, shaped the political image of the United States across German speaking Europe. The content of letters reflects what popular literature at the time held to be true about the political but also economic, cultural, and social aspects of life in America (Krawatzek and Sasse Citation2019c; Mikoletzky Citation1988). A repeated act of private communication may change political perceptions and eventually translate into political acts which further diffuse and change feasibility judgements. Van Hear and Cohen (Citation2017) advance a similar distinction between the overlapping private spaces, the known and the imagined community, in which diaspora engagement occurs.

This historical duality which permeates public and private realms lies at the very heart of the dual political community of which migrants are a part. Once an individual becomes a migrant, she has the potential to influence the politics of her place of residence as well as that of her place of origin and can potentially voice her opinion on behalf of both. However, migrants are not necessarily used to formal political engagement – it is therefore also often in the seemingly private sphere in which politically transformative acts are located. Moreover, the new political environment which migrants experience, may itself be part of the transformative experience of migration and shape how migrants perceive their political role.

Approached from this perspective, remittances as they are manifest empirically are often a composite of political, social, cultural, and economic elements. Although the focus in this issue is on the analytically distinct political dimension, the case studies also consider the composite nature. This focus thereby decentres the prevailing scholarly emphasis on the economic and social aspects of remittances (Adida and Girod Citation2011; Ahmed Citation2012; Gallo Citation2013; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2013; Mata-Codesal Citation2013).

Meanwhile, our concept of remittances acknowledges that not all migrants live a transnational life. Indeed, previous research might have over-exaggerated the degree of transnationalism within the overall migrant population by studying those migrants who engaged in remitting, i.e. sampling on the dependent variable. However, migrant lives may lack an overtly transnational dimension (Portes Citation2003). Whilst some migrants create unbounded nations (Basch, Glick Schiller, and Blanc-Szanton Citation1994), others clearly do not. In their study on transnational entrepreneurs, Guarnizo, Portes, and Haller (Citation2003) show, for instance, that only five percent of their respondents lived a transnational life.

It is not possible to entirely solve the question of how much remitting takes place. The cases at the heart of this special issue display the ebbs and flows of political remittances across time and space. A key aspect to understand the dynamics of political remittances have been decisive political events, critical junctures (Capoccia and Kelemen Citation2007) or transformative events (Sewell Citation1996) in home or host society, and in particular those which oppose the societies with which migrants identify. Studying the political mobilisation of Irish migrants, Hanagan illustrates how Irish nationalism could flourish in the US during the uncertainty prior to the outbreak of the Civil War and its stormy aftermath (Citation1998, 115). Similarly, critical events such as crises and wars fundamentally impacted on the function and structure of German migrant networks in the US (Krawatzek and Sasse Citation2019b). Most recently, the Arab Spring has illustrated the critical role of events to reset migrants’ sense of belonging and political orientation (Müller-Funk Citation2020).

3. Political remittances: flows of political principles, vocabulary and practices

We develop and probe a new definition of political remittances building on theoretical work that has been advanced since the emergence of the original concept of social remittance (Goldring Citation2004; Lacroix, Levitt, and Vari-Lavoisier Citation2016; Levitt Citation1998; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Tabar Citation2014). Our definition of political remittances addresses three shortcomings of previous concepts. (1) They are oftentimes blurred and have attempted to cover not only an extremely diverse but also a contradictory set of phenomena, as Boccagni and Decimo highlight (Citation2013). (2) Our conceptualisation critiques the prevailing tendency of analysing migration from the receiving end, especially in migration scholarship rooted in the literature on immigrant integration. The term remittance itself is no exception to this tendency as it has its origin in the idea of a unidirectional flow – of ‘sending money back’. We contend, however, that political remittances should be rather conceptualised as including multi-directional flows of political ideas and practices. (3) The concept of political remittances needs to go beyond the nation-state as sole reference point. In our analysis, transmitted political principles, vocabulary, and practices, do not necessarily cross (modern) national borders but are transmitted across regions within the same country (internal migration) or historically between different provinces of empires.

3.1. The distinctiveness of political remittances: a redefinition

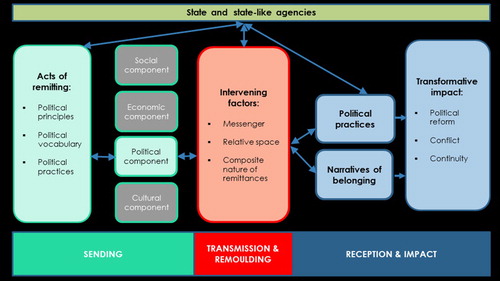

Political remittances have appeared as an indistinct subcategory of social remittances. In Levitt’s definition, for example, social remittances encompassed politics, broadly defined to include ideas, values, and beliefs about the organisational performance of state institutions but also patterns of civil and political participation (Citation1998, 933–4). Lacroix, Levitt, and Vari-Lavoisier (Citation2016) tend to also subsume the political in social remittances when including ‘intangible flows’, ‘democratic diffusion’, and ‘transfers of norms’. We suggest defining political remittances however more narrowly, namely as the act of transferring political principles, vocabulary and practices between two or more places, which migrants and their descendants share a connection with. Political remittances are remoulded in a context of migration, and can, in turn, influence political behaviour, mobilisation, organisation and narratives of belonging in places of destination and origin (). Transversal actors involved in influencing political remittances are the state (through immigration, integration, emigration, and diaspora policies) and state-like agencies, such as state-sponsored religious bodies or employment agencies abroad.

The definition of political remittances that we propose is thus narrow insofar as we do not consider every aspect of transnational political activity to fall into this category. Thus conceptualised, political remittances are not the mere protesting behaviour of a diaspora community or the electoral participation of citizens living abroad. Instead, we suggest that political principles, vocabulary, and practices, hence political remittances, received from a different place may trigger political acts such as protesting and voting. We argue that political remittances are analytically distinct from other remittances primarily because they may want to transform the state itself and generally target the public sphere – in contrast to social, economic or cultural remittances. This is why political remittances are mediated by the state and might also become the target of its outreach activities.

Within this special issue, the case studies cover a range of political remittances. Examples include writing about protests organised by the second-generation Egyptian youth in Vienna to support political movements in Egypt (Müller-Funk Citation2020), or the knowledge gained through participation in self-organised discussion circles by journeymen who then brought that knowledge back home during the early German labour movement in the nineteenth century (Schmidt Citation2020).

Building on Levitt’s conceptualisation of social remittances as norms, practices, identities, and social capital (Citation2001), we distinguish between three types of political remittances: principles, vocabulary, and practices (). (1) Political principles encompass norms for the functioning of political institutions including the role of the clergy, judges, and politicians, the place of religious institutions in politics, ideas about organisational features of politics such as voting systems, perceptions of transparency, corruption, and standards of political participation or party preferences. It can include for instance changed norms of war when German migrants in the US write about their experience of citizens voluntarily participating in the US Civil War at a time when wars across Europe relied primarily on compulsory military participation (Krawatzek and Sasse Citation2019a). (2) Transmitted political vocabulary consists in the transfer of political terms, symbols and slogans, as well as the specific framing of political messages. This can include political symbols, such as the R4BIA sign, identical to the hand gesture for the number four, which spread across Egyptian networks in the diaspora and symbolised opposition to Morsy’s ousting in summer 2013 (Müller-Funk Citation2019). (3) Political practices include knowledge about patterns of civil and political participation – membership recruitment, mobilisation techniques, political strategies and campaigning, forms of protesting, political leadership styles, forms of political communication. Piper and Rother demonstrate for example how returning delegates and activists who had participated in awareness-raising campaigns about migrants’ rights in Hong Kong, translated these experiences in the activism of the Migrant Forum Asia (Citation2020). Obviously, the distinction between these dimensions is purely analytic as all three tend to be intertwined empirically.

The mechanisms for transmitting political remittances are diverse: Remittances travel through personal exchange, either by long-distance communication (exchanges of letters, emails, telephone calls or video-chats, music, videos, and social media) or face-to face communication (conversations with returnees and through business trips, visits and travel) or through the activity of organisations (Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011).

While we argue that a conceptualisation of political remittances should go beyond the nation-state, the state still plays a crucial transversal role in trying to shape the form and content of remittances because political remittances can undermine or support the state and ultimately change the nature of the state itself through political conflict or reform. Therefore, sending states often attempt to influence the content of their emigrants’ political remittances, as a literature on diaspora policies and the emigration state shows (Gamlen Citation2008; Green Citation2005; Green and Weil Citation2007; Hollifield Citation2004; Lafleur Citation2013). Sending states try to influence the organisation and political control of community life abroad, the granting of voting rights, and citizenship policies that include migrants’ descendants within a broader and borderless conceptualisation of the nation (Kovács Citation2020). Finally, states also influence the remoulding of political remittances by shaping the structural conditions and the legal context, setting the political opportunity structure in which messengers of remittances can act. This includes political rights such as freedom of expression and association and other policies shaping political participation such as citizenship policies of receiving states (Soysal Citation1994).

3.2. Intervening factors in the transmission of political remittances and their impact

Different factors influence the transmission process of political remittances and thereby their potential impact (). First, we distinguish between factors linked to the messengers of political remittances. These include their social status, their reason for migration, and their pre-migratory political socialisation (Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Tarrow Citation2005) but also experiences made upon and after migration (inclusion, exclusion) as well as the density of transnational networks to which they have access. Successful messengers of political remittances often have a high social status and are well connected in places of origin and destination (Tarrow Citation2005).

Second, there are factors linked to what we call relative space. These include, for example, the congruence between sending and receiving contexts which in turn has an impact on whether or not political principles and vocabulary can be successfully remitted. Moreover, the possibility for alliance building relies on the location from which a messenger transmits political remittances, a factor which draws attention to the importance of power relations and the distance between places (Boccagni and Decimo Citation2013). In addition, the respective context of departure and reception (size of migrant communities, policies influencing political participation, and critical events such as protests, upheavals, and revolutions) as well as the target audience and its gender, socio-economic, and educational composition, are factors which play into the relationship between the two or more places to which migrants are connected.

Third, the features of the transmission process and the composite nature of political remittances are crucial in determining the reach of political remittances and relate back to the social status of the messenger. Do political remittances travel along with economic or cultural remittances? Lindley (Citation2010) illustrates that economic remittances of Somali refugees in London are embedded in a social relationship and can be a source of cultural and familial affirmation. We thus contend that research on the impact of political remittances must equally consider the composite nature of remittances.

Turning to reception and impact, there is consistent evidence of migrants’ ability to shape non-migrants’ political attitudes (Betts and Jones Citation2016; Córdova and Hiskey Citation2015; Levitt Citation1998; Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow Citation2010; Piper Citation2009; Shain Citation1999). International organisations and development agencies have often emphasised the positive potential of economic remittances for the improvement of living conditions in receiving countries, especially developing countries (Kapur Citation2004). This ‘remittance euphoria’, which saw remittances as an alternative or substitute to external development aid, has sometimes been shared by scholars of political transnationalism with the idea that democratic values acquired in Western countries can be transferred back to sending countries (Escribà-Folch, Meseguer, and Wright Citation2019). Several scholars highlight the potential of political remittances for furthering progressive political agendas or promoting democracy. Keck and Sikkink (Citation1998), for example, interpret transnational links as an emerging form of progressive politics and Piper (Citation2009, 238) equally connects political remittances and democratisation, arguing that political remittances can aim at the democratisation of the migration process.

However, other authors have questioned this euphoria, underlining that unattractive investment opportunities and restrictive immigration policies limit the actual potential of remittances (De Haas Citation2005). Similarly, Levitt was cautious when first assessing the impact of social remittances, stating that nothing can guarantee that knowledge acquired in the host society will be constructive or will have a positive effect on communities of origin (Levitt Citation1998, 944). In his study on the Philippines, Rother (Citation2009) elaborates on the negative effect of political remittances. Moreover, Doyle finds that economic remittances increase a population’s income level and thereby reduce pressure on governments for welfare spending (Citation2015). We therefore insist on the transformative potential of political remittances to try and overcome the normative bias of the concept. The impact of remittances is hence not negative or positive per se, as Eckstein and Najam’s edited volume illustrates (Citation2013). Political remittances are part of daily life, they shape cultural orientations, social norms, and political ideas, and influence how people perceive, and view politics. We also emphasise that political remittance can have an impact on receiving and destination places at different levels – private, local, regional, national or supranational (see also Levitt and Lamba-Nieves (Citation2011)).

Political remittances can thus have different impacts after their transmission. They may influence conventional forms of political participation such as voting, protesting or membership in political parties but also civil society activism, creative and artistic forms of raising political awareness, and symbolic politics. They can influence public attitudes and lead to calls for greater transparency or reform. However, they can deepen or replicate political cleavages or lead to political continuity or immobility. Anderson’s paper (Citation2020) for example, illustrates the success of the Danish Brotherhood in America in lobbying for a pro-democratic diplomatic corps during World War II. Hartnett (Citation2020), on the other hand, shows how political remittances can yield tangible outcomes, for instance the freeing of Russian political prisoners by mobilising the support of the local British population for this end.

3.3. How to operationalise political remittances

We now want to offer a way to decipher political remittances empirically. Drawing on the conceptualisation developed in the previous two sections, we offer a heuristic of political remittances which enables researchers to identify political remittances and assess the scope of their work. The different flows of remittances can be operationalised inductively by assessing the relationship between the sender and receiver of remittances, their transmission and remoulding, as well as their impact.

Senders of political remittances can be migrants, their descendants as well as non-migrants in places of origin since remittances are multidirectional. We found that remittances are sent by a wide variety of individuals: political exiles and intellectuals, returnees and deportees, children of migrants and family members back home as well as associations and networks of associations, religious institutions, and different levels of state governments in places of origin and settlement. We hence do not make a clear distinction between individual and collective senders as some previous research has done (Goldring Citation2004; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011), reflecting our earlier argument that the boundaries between the private and the public in political transnationalism are often blurred.

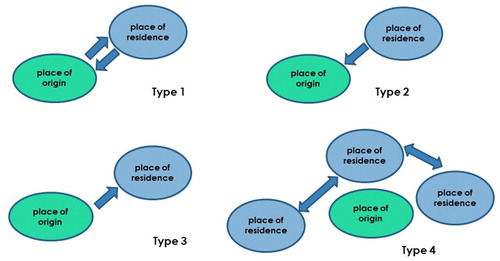

A next step in operationalising political remittances is to evaluate their spatial flows. Overwhelmingly, political remittances will in fact be circular, understood as back and forth movements between places of residence and origin (type 1, ), such as in the case of circular migration (Schmidt Citation2020). However, it is extremely difficult to empirically research this circular movement. Mostly, political remittances have been understood as the flows sent from migrants and sometimes their descendants in their place of residence to non-migrants in the respective places of origin (type 2, ). Along those lines, Goldring conceptualised political remittances as ‘the political identities, demands and practices of return migrants acquired as a result of their transnational migration experience’ (Citation2004, 805). Krawatzek and Sasse’s example of German migrant letters sent from the United States is an illustration of this classical flow (Citation2020). Although the letters circulated between both places, the available sources do not allow to precisely evaluate the full extent of the remitting flow.

In addition, we emphasise that political remittances include the transmission of political ideas, vocabulary, and practices from non-migrants in places of origin to migrants and their descendants in their respective places of residence (type 3, ). For example, religious norms and ideas, which are transmitted through the International Theology Programme teaching Islam to young foreigners of Turkish origin in the diaspora, can influence the narratives of belonging and political behaviour of migrant communities in receiving areas (Bruce Citation2020). Political ideas are also sent between migrants living in different places of residence without flows between the places of origin and residence (type 4, ), such as political advocacy, organising strategies, and the framing of political issues which are transmitted between migrants’ rights organisations across Asia (Piper and Rother Citation2020).

4. The influence of political remittances

The following discussion examines specific aspects of the cases in this issue with the aim of probing the conceptualisation of political remittances developed above, along the dimensions of political practices, narratives of belonging, and the role of the state. This analysis also helps to identify the analytic links between the cases and to hopefully stimulate future research ().

Table 1. Overview of articles in the special issue.

4.1. The impact on political practices: actors and conditions

We consider as a first dimension the impact political remittances may have on political practices after their transmission. The underlying questions in that regard is the extent to which remittances can shape politically relevant practices. Who remits and what conditions or events encourage or discourage remittances? What kind of political practices do migrants remit? How are remittances changed in the remoulding process between places of origin and destination? When do political remittances lead to political change?

Political remittances might lead to very tangible political actions in places of origin and have led for example to changed forms of how workers self-organised their interests across German-speaking Europe in the nineteenth century. Schmidt’s case study on the circulation of German journeymen across Western Europe highlights how, as a result of the remitting of political and economic ideas, new forms of worker associations emerged. The German labour movement itself was heavily influenced by returning migrants who brought their experience of a foreign system of economic and political participation back. The ensuing principles were dependent on the degree of exposure to new forms of economic thought in their respective places of residence. A critical factor in this regard was experiencing at first-hand the ideal of worker self-organisation, alongside the associational structures, which were in tune with the Zeitgeist of rising worker self-consciousness within the context of industrialisation. Journeymen also absorbed the language of socialism through the engagements with intellectuals abroad. The remoulding of remittances in this case is noteworthy because these remittances were transmitted personally through the return of journeymen, which augmented their impact. In this case of circular economic migration, the type of remittance is primarily of type 1, since practices moved back and forth along with the circular migration of wandering journeymen between places of origin and destination.

Similarly, examining the behaviour of Russian revolutionary émigrés in London, Hartnett’s case study identifies their critical role in late Tsarist Russia and the run-up to the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917. With money raised in Britain, émigrés could free political prisoners in Russia but also remit political ideas. This type of political remittances is primarily akin to type 2, circulating from migrants in the place of residence to non-migrants in that of origin. The conditions in the place of residence shaped the kind of principles which were remitted. Experiencing British liberalism in a time of Russian despotism changed émigrés’ political expectations about the possible trajectory of the Russian regime and increased hopes for its political change. In the liberal political context of late nineteenth century Britain, their appeals to human rights echoed with Western notions of Humanitarianism. The émigrés could hence successfully use networks in Britain which included the local British population alongside descendants of other migrant groups. Another reason for their success was the émigrés’ relative position as vanguards of revolutionary thought and the perceived centrality of London as a centre for political migration ever since the French Revolution. Moreover, the experience of migration impacted the vocabulary that revolutionary émigrés remitted, with the development of a discourse about a free Russia that empowered revolutionary vanguard groups as those who could bring about political change in the homeland.

Rother and Piper’s case study on the Migrant Forum Asia shows how political remittances can affect learning and the exchange of knowledge amongst networks of organisations. Their case demonstrates different forms of learning: horizontally, amongst members of the Forum itself, and vertically, between differently positioned migrant organisations, i.e. at the regional, national or supranational level. The learning processes centre primarily on a human rights based understanding of migrant workers’ rights. The remitted principles and vocabulary includes a global legal discourse that migrant organisations encourage and spread between different member organisations. Moreover, remitted practices encompass procedures to prevent deportations or ways to publicise human rights violations. The local context itself shapes the remitting of such practices, principles, and vocabulary given the importance of what kind of information and resources are available locally. The remittances therefore illustrate type 4, flowing between member organisations in different places of residence without necessarily involving places of origin.

These case studies and others in this issue demonstrate how remitted practices are intrinsically linked to the principles and the vocabulary which are part of them. Migrants, associations, as well as states transmitted practices in these examples and their outcomes were not simply liberal or emancipating. Their success depends on several factors – the characteristics of the messenger of political remittances, the relative space in which they act, and the composite nature of the remittances.

4.2. The shaping of hybrid identities and political remittances

Political remittances can also influence narratives of belonging: What implications do crucial events in places of origin and destination have on identity constructions and how do they change over time?

Political remittances have contributed to shaping hybrid forms of identity throughout time. Krawatzek and Sasse, studying letters of German-speaking migrant communities in the US, identify the extent to which these hybrid identities persist in the context of shifting cultural policies. The integration of this migrant community responded much more to underlying local structures and the social interactions in places of residence than regional differences in education policy, underlining that state policies might not always have the effect they wish to achieve. The case study therefore illustrates the compensatory mechanisms migrants adopt under conditions of shifting policies. At the point of their migration to the US, nation-building in Germany had been far from conclusive. Instead, migrants discovered the meaning of being German to some extent only through migration itself and remitted a hybrid version of German-Americanism back which took shape in the encounter with other Germans abroad. The sense of belonging which migrants remitted back to German-speaking Europe changed when critical events such as World War I put places of origin and residence into opposition. However, even in that crisis, German migrants’ individual expressions of a German identity proved to be of remarkable resilience despite strong assimilation pressures. Nevertheless, the war was a decisive juncture which changed how ‘Germanness’ could be practiced and which fundamentally called into question the desirability of being German in the US. In this regard, the migrant communities acquired a new vocabulary of speaking about being German. The flow of these remittances is of type 2 since German migrants remitted back ideas of identity to non-migrants in their place of origin. Obviously, the communication went both ways, however, the according flow of remittances (type 1) can only be reconstructed indirectly through the letters.

Hybrid identities are integral to most migration experiences. Anderson’s case study of the Danish-American lodges, an example of type 1, further illustrates how such hybrid identities were institutionalised and cultivated over time. The availability of Danish-American organisations not only nurtured hybridity, they also facilitated migration of Danes to the US as they tempered the cultural shock that most migrants experienced upon arrival. These kinds of migrant organisations cultivated principles and practices of what it meant and implied to be Danish, through the singing of Danish songs, reading of Danish books, and participating in folk dances. During World War II, following the occupation of Denmark by Nazi Germany, these associations were also able to spread an alternative idea of what Denmark could signify that went beyond the image of Danish collaboration with fascism: The national fraternal organisation and its constituent lodges employed instead a counter-narrative which emphasised Danish freedom and its proximity to America’s founding ideology. Whilst the Brotherhood provided a vocabulary to preserve and propagate authentic memories of Denmark, this discourse could later on be used by the Danish ambassador in Washington to speak about ‘free Denmark’ during the war and thereby address the allied forces as well as the American public. Beyond political actions, the lodges also spread such values by promoting certain expressions of Danish culture, such as the book I chose Denmark, written by an Irish-born author who lived in Denmark prior to World War II, which portrays a free and democratic Denmark. Importantly, the context of reception contributed to the success of these remittances since the US itself was at that time considered the leader of ‘the free world’.

Studying second-generation Egyptian youth associations in Vienna, Müller-Funk’s paper highlights the hybrid identities which political remittances may foster. Significantly, it underlines that the balance within hybrid identities is itself in permanent motion and reacts in particular to critical events in places of origin. The revolution in Egypt in 2011 and the phase which followed, heavily politicised Egyptian youth organisations abroad. The environment in which these youths were living subsequently reshaped the flows of political ideas and principles emanating from Egypt and thus influenced their identity constructions. As a result, young Austrians of Egyptian origin in Vienna highlighted on the one hand the Egyptian side of their identity, at least, during the first phase of the revolution – including initially a strong feeling of pride for the political events happening in Egypt. Ideas about what it means to be a ‘free and democratic Egyptian’ which took shape in the context of the 2011 revolution were amongst the principles remitted from Egypt to Vienna. Moreover, the spread of a revolutionary vocabulary from Egypt to Austria could be observed which impacted on how multilingualism was lived. The discrimination and violence which Copts experienced in post-revolutionary Egypt led to a fracturing of identity expressed by Egyptian youth in Vienna based on religious belonging. Identity constructions were also influenced by the discourse on national identity in the receiving context as well as by instances of discrimination that especially Muslim respondents had experienced. These flows are hence of type 3, since the remittances flow from non-migrants in the place of origin to descendants of migrants in the place of residence.

These three case studies demonstrate that identity constructions are fluid social and political practices, closely linked to political events and the political demands made by senders of remittances (Dufoix Citation2008). Meanwhile, the examples above underline that identities are by no means confined to the nation. How migrants understand their own identity does not necessarily correspond to the perspective of the sending state. Schmidt’s analysis of journeymen illustrates for example the emergence of a self-consciousness as workers through the process of migration, while Rother and Piper emphasise that identities specifically as migrant workers can also take shape in migration without being linked to a sense of belonging to a nation.

4.3. Potential and limits of the state in capitalising on remittances

A third dimension examines the role of the state or state-like agencies in trying to capitalise on its migrant stock and the remittances it generates. Thanks to the resources at the disposition of the state, it is an actor that usually intervenes in both, shaping practices and senses of belonging. Sending states act often within type 3, in other words, they aim at influencing remittances in places of residence of their migrant population. However, if the state is successful in its endeavour, it might lead to type 2 and influence events ‘back home’. Such state involvement can also lead to competition between sending and receiving states – which both aim at influencing for example practices and senses of belonging of migrants. The example of Turkey’s International Theology Programme and the establishment of Islamic theology faculties at Austrian and German universities by each respective state in recent years tellingly illustrate such a competition. However, looking at the role of the state through the perspective of remittances also challenges ideas of a unitary state. The actions of a diaspora are themselves relevant for how a state conceives of itself and acts politically. Indeed, migrant groups may question the authority of official representatives to speak for the state and migrant involvement on the level below the state is particularly apt to questioning ideas of the state as a homogeneous actor.

In the case of the Japanese population in South America, Takenaka’s paper (Citation2020) illustrates the changing importance of this migrant community for the state. During most of the nineteenth and early twentieth century, Japan’s nation-building project incorporated the colonial fantasies that had emerged in Western Europe and adopted a discourse of wanting to spread the empire beyond Asia. As colonial emigration progressed, ideas of heroic Japanese settlers who contributed to the agricultural, economic, and cultural development of ‘the hinterland’ in South America prevailed to include emigrants into the map of the Japanese nation. Intellectuals and politicians promoted the image of Japanese emigrants furthering the development of South America as ‘pioneers in frontier expeditions’ and emphasised their contribution to national labour and agricultural productivity ‘in the frontier’. The juncture of World War II changed how Japan related to its overseas population as part of its imagined national identity. Japan had come under severe pressure during the war. This critical event thus intensified links between migrants and their place of origin. In the post-World War II context, the Japanese government tried to use the overseas Japanese population as cultural mediators which could translate the country’s culture and progress to the wider world. Since the late 1980s, with government policies encouraging return migration from Latin America, the overseas communities have remained a constitutive part of national Japanese identity, though, only specifically as diaspora. If these descendants of migrants return to Japan, they begin to disturb the sense of cultural homogeneity prevailing in the Japanese context. These remittances can hence be analysed as type 3 as they are remitted from the place of origin to migrants in places of destination.

Looking at different forms of how a state engages its diaspora politically and symbolically through remittances, Kovács points to the shifts in the kind of remittances states have tried to mobilise. Studying present-day Hungary, she discusses how an increasingly right-wing and nationalist government places policies of engaging its own population abroad in the centre of its political agenda. As a result, the Hungarian government distinguishes between two types of Hungarians living abroad and accordingly engages with these groups in different ways. On the one hand, its kin-minority in neighbouring countries is seen as having potentially more tangible political relevance or political capital. The diasporic community beyond the immediate neighbouring countries, on the other hand, is engaged primarily on the symbolic level as a component for reconstructing a sense of Hungarian national identity. The guiding principles of these policies are an expanding sense of Hungarianness which becomes clear in reforms to the citizenship law and the differential treatment made towards different types of Hungarians abroad.

Practices by migrants can also be shaped by remittances initiated by the state. In Bruce’s study on Turkey’s International Theology Programme, we see how Turkey endeavours to propagate a distinct vision of how Sunni Islam ought to be practiced within diaspora communities. The principles remitted through the International Theology Programme are tied to prescriptive practices and delimit the boundaries of acceptable behaviour for Sunni Turkish Muslims in a Western minority context. The religious ideas and norms that the Turkish state spreads are especially influential whenever they are in tune with the local situation of Muslims in Western Europe. The participants of the programme are well suited to translate these principles between the places of origin and destination as they know both contexts and can provide responses to questions which are of relevance for migrant communities abroad. At the same time, the Turkish state does not cast doubt on the loyalty of these students to the Turkish nation, nor on their dominant religious identity as Sunni Muslims. Although they might have been born and raised in another country, and are required to have dual or foreign citizenship, they are represented as full members of the Turkish nation. Nevertheless, in practice, participation in this programme simultaneously reinforced its participants’ Turkish, Muslim, and European identities, highlighting their particular transnational and hybrid backgrounds. The sender of remittances in this case, the Turkish state religious authorities, exercise unique power and bestow high social status to its participants. These political remittances are primarily of type 3, since political remittances are remitted from the place of origin to migrant communities in their respective places of residence. It can, however, also lead to type 2 if the participation in the process increases at the same time the support for the Justice and Development Party within Turkish migrant communities.

Most case studies in this issue touch upon the fundamental role of the state in conditioning the kind of remittances that circulate between ‘here’ and ‘there’. However, the shared focus on cases of international migration equally points to the need to question the nature and unity of the state, as well as its possible limits in migratory contexts.

5. Conclusion

This introduction provides a heuristic setting to link the diverse case studies to their shared interest in the forms and impacts of political remittances. We also develop a way to operationalise political remittances in future research and suggest that the concept of political remittances enables cross-temporal and cross-sectional comparisons as it avoids a nation-centred starting assumption. Instead, it emphasises changing connections across a variety of spaces such as regions and localities, above and below the national.

The articles united in this special issue offer a unique combination as this volume is the first to approach political remittances from different disciplinary perspectives. Taken together, the conceptual introduction and the case studies contribute to a thematically focussed dialogue which engages the disparate literature on transnationalism across different disciplines of the social sciences and history. The case studies range from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century in a wide variety of geographical areas. This diversity serves to empirically delve deep into the changing forms of political flows across borders.

The examples of political remittances analysed in this issue demonstrate the importance of taking into account the intervening factors which relate to the specificities of both the messengers and receivers of remittances, as well as the relative space linking them, and the composite nature of remittances. We found that the relative position of both groups of actors along with the directionality of the flow has an impact on the circulation of remittances. This perspective moreover encourages researchers to consider the processes of remoulding themselves to better understand political remittances, rather than simply ignoring the issue or confining it to a black box. Our conceptualisation advances that the transmission is distinct and conceptually prior to the impact remittances have. Lastly, an agent-centred perspective demands that the different levels that individuals and groups are part of are considered so as to understand the interplay between local, regional or supra-national layers.

We do not hesitate to point out that this approach certainly does not provide a solution to all the remaining challenges in the study of migrant political engagement. First, it will remain inherently difficult to obtain the kind of sources needed to fully trace the process of political remittances outlined in this introduction. Indeed, the case studies here rarely comply fully to this ideal-type conceptualisation. Second, our selection of cases has conceivably led us to overlook forms of political remittances and their impacts, which studies on other regions and times might bring to the fore. The heuristic should not be seen as set in stone, therefore, but rather as an opportunity for further study on the topic. Third, more work is needed on the interaction between political and other kinds of remittances. Whilst this issue foregrounds the political aspects, it is evident even within the cases studied here, that the political can never be fully conceived when considered in isolation from economic, social, or cultural aspects. We have tried to express this characteristic through the idea of the composite nature of remittances; however, this certainly remains another avenue for further research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Félix Krawatzek http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1108-6087

Lea Müller-Funk http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9934-0491

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 This paper has been made possible through discussions during the workshop ‘Political Remittances and Political Transnationalism: Narratives, Political Practices and the Role of the State’ which took place in Oxford in June 2017 and was generously supported by Nuffield College, the DPIR Oxford, OxPo, and the Maison Française d’Oxford. We are indebted to all participants for having shared their insights and wish to extend our gratitude in particular to Iain Anderson, Benjamin Bruce, David Doyle, Ana Isabel López García, Gwendolyn Sasse, Nick Van Hear, Ilka Vari-Lavoisier and Simona Vezzoli for their generous comments. Emma Chippendale has created a podcast of the workshop available here: http://bit.ly/2yFs0yx. The authors are jointly responsible for any remaining flaws.

References

- Adida, Claire, and Desha Girod. 2011. “Do Migrants Improve Their Hometowns? Remittances and Access to Public Services in Mexico, 1995–2000.” Comparative Political Studies 44 (1): 3–27.

- Ahmed, Faisal. 2012. “The Perils of Unearned Foreign Income: Aid, Remittances, and Government Survival.” American Political Science Review 106 (1): 146–165.

- Anderson, Iain. 2020. ““We’re Coming!” Danish American Identity, Fraternity, and Political Remittances in the Era of World War II.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1094–1111. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554297.

- Basch, Linda, Nina Glick Schiller, and Cristina Blanc-Szanton. 1994. Nations Unbound: Transnational Projects, Postcolonial Predicaments, and Deterritorialized Nation-States. London: Gordon & Breach Science Pub.

- Bauböck, Rainer. 2003. “Towards a Political Theory of Migrant Transnationalism.” International Migration Review 37 (3): 700–723.

- Becker, Felicitas. 2004. “Netzwerke vs. Gesamtgesellschaft: Ein Gegensatz? Anregungen für Verflechtungsgeschichte.” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 30 (2): 314–324.

- Betts, Alexander, and Will Jones. 2016. Mobilising the Diaspora: How Refugees Challenge Authoritarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Boccagni, Paolo, and Francesca Decimo. 2013. “Mapping Social Remittances.” Migration Letters 10 (1): 1–10.

- Brinkerhoff, Jennifer M. 2009. Digital Diasporas: Identity and Transnational Engagement. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Bruce, Benjamin. 2020. “Imams for the Diaspora: The Turkish State’s International Theology Programme.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1166–1183. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554316.

- Capoccia, Giovanni, and Daniel Kelemen. 2007. “The Study of Critical Junctures: Theory, Narrative, and Counterfactuals in Historical Institutionalism.” World Politics 59 (3): 341–369.

- Choate, Mark I. 2007. “Sending States? Transnational Interventions in Politics, Culture, and Economics: The Historical Example of Italy.” International Migration Review 41 (3): 728–768.

- Córdova, Abby, and Jonathan Hiskey. 2015. “Shaping Politics at Home: Cross-Border Social Ties and Local-Level Political Engagement.” Comparative Political Studies 48 (11): 1454–1487.

- De Haas, Hein. 2005. “International Migration, Remittances and Development: Myths and Facts.” Third World Quarterly 26 (8): 1269–1284.

- Délano, Alexandra. 2011. Mexico and Its Diaspora in the United States: Policies of Emigration Since 1848. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Délano, Alexandra, and Alan Gamlen. 2014. “Comparing and Theorizing State–Diaspora Relations.” Political Geography 41: 43–53.

- Doyle, David. 2015. “Remittances and Social Spending.” American Political Science Review 109 (4): 785–802.

- Dufoix, Stéphane. 2008. Diasporas. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Eckstein, Susan Eva, and Najam Adil, eds. 2013. How Immigrants Impact Their Homeland. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Escribà-Folch, Abel, Covadonga Meseguer, and Joseph Wright. 2019. “Remittances and Protest in Dictatorships.” American Journal of Political Science 62 (4): 889–904.

- Faist, Thomas. 2000. The Volume and Dynamics of International Migration and Transnational Social Spaces. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Gallo, Ester. 2013. “Migrants and Their Money are not all the Same: Migration, Remittances and Family Morality in Rural South India.” Migration Letters 10 (1): 33–46.

- Gamlen, Alan. 2008. “The Emigration State and the Modern Geopolitical Imagination.” Political Geography 27 (8): 840–856.

- Glick Schiller, Nina. 2009. A Global Perspective on Transnational Migration: Theorizing Migration Without Methodological Nationalism. Oxford: Centre on Migration, Policy and Society.

- Glick Schiller, Nina, Linda Basch, and Cristina Blanc-Szanton. 1992. “Transnationalism: A New Analytic Framework for Understanding Migration.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 645 (1): 1–24.

- Goldring, Luin. 2004. “Family and Collective Remittances to Mexico: A Multi-Dimensional Typology.” Development & Change 35 (4): 799–840.

- Green, Nancy. 2005. “The Politics of Exit: Reversing the Immigration Paradigm.” Journal of Modern History 77 (2): 263–289.

- Green, Nancy. 2011. “Le transnationalisme et ses limites: le champ de l’histoire des migrations.” In Pratiques du transnational. Terrains, preuves, limites, edited by J.-P. Zúñiga, 197–208. Mayenne: Jouve.

- Green, Nancy, and François Weil, eds. 2007. Citizenship and Those Who Leave: The Politics of Emigration and Expatriation. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

- Guarnizo, Luis Eduardo, Alejandro Portes, and William Haller. 2003. “Assimilation and Transnationalism: Determinants of Transnational Political Action among Contemporary Migrants.” American Journal of Sociology 108 (6): 1211–1248.

- Haddad, Yvonne Joshua. 2013. “Good Copt, Bad Copt: Competing Narratives on Coptic Identity in Egypt and the United States.” Studies in World Christianity 19 (3): 208–232.

- Hanagan, Michael. 1998. “Irish Transnational Social Movements, Deterritorialized Migrants, and the State System: the Last one Hundred and Forty Years.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 3 (1): 107–126.

- Hartnett, Lynne Ann. 2020. “Relief and Revolution: Russian émigrés’ Political Remittances and the Building of Political Transnationalism.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1040–1056. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554290.

- Hollifield, James F. 2004. “The Emerging Migration State.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 885–912.

- Itzigsohn, José. 2000. “Immigration and the Boundaries of Citizenship: The Institutions of Immigrants’ Political Transnationalism.” International Migration Review 34 (4): 1126–1154.

- Kadish, Sharman. 1992. Bolsheviks and British Jews: The Anglo-Jewish Community, Britain and the Russian Revolution. New York: Routledge.

- Kapur, Devesh. 2004. Remittances: The New Development Mantra. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. G-24 Discussion Paper Series.

- Keck, Margaret, and Kathryn Sikkink. 1998. “Transnational Advocacy Networks in the Movement Society.” In The Social Movement Society: Contentious Politics for a New Century, edited by David S. Meyer, and Sidney Tarrow, 217–238. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Kocka, Jürgen. 2003. “Comparison and Beyond.” History and Theory 42 (1): 39–44.

- Kovács, Eszter. 2020. “Direct and Indirect Political Remittances of the Transnational Engagement of Hungarian Kin-minorities and Diaspora Communities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1146–1165. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554315.

- Krawatzek, Félix, and Gwendolyn Sasse. 2019a. “Integration and Identities: The Effect of Time in Migration, Migrant Networks, and Political Crises on the Germans in the US.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 60 (4): 1029–1065.

- Krawatzek, Félix, and Gwendolyn Sasse. 2019b. “Migrantische Netzwerke und Integration: Das Transnationale Kommunikationsfeld deutscher Einwandererfamilien in den USA.” Zeitschrift für vergleichende Politikwissenschaft 12 (1): 211–228.

- Krawatzek, Félix, and Gwendolyn Sasse. 2018c. “The Simultaneity of Feeling German and Being American: Analyzing Patterns of Immigrant Integration Based on 150 Years of Private Correspondence.” Migration Studies. doi:10.1093/migration/mny014.

- Krawatzek, Félix, and Gwendolyn Sasse. 2020. “Language, Locality, and Transnational Belonging: Remitting the Everyday Practice of Cultural Integration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1072–1093. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554295.

- Lacroix, Thomas, Peggy Levitt, and Ilka Vari-Lavoisier. 2016. “Social Remittances and the Changing Transational Political Landscape.” Comparative Migration Studies 4 (16). doi:10.1186/s40878-016-0032-0.

- Lafleur, Jean-Michel. 2013. Transnational Politics and the State: The External Voting Rights of Diasporas. New York: Routledge.

- Lepenies, Wolf. 2003. Entangled Histories and Negotiated Universals: Centers and Peripheries in a Changing World. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Levitt, Peggy. 1998. “Social Remittances: Migration Driven Local-Level Forms of Cultural Diffusion.” International Migration Review 32 (4): 926–948.

- Levitt, Peggy. 2001. The Transnational Villagers. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. “Conceptualizing Simultuneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 1002–1039.

- Levitt, Peggy, and Deepak Lamba-Nieves. 2011. “Social Remittances Revisited.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (1): 1–22.

- Levitt, Peggy, and Deepak Lamba-Nieves. 2013. “Rethinking Social Remittances and the Migration-Development Nexus From the Perspective of Time.” Migration Letters 10 (1): 11–22.

- Lindley, Anna. 2010. The Early Morning Phone Call: Somali Refugees’ Remittances. Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Lucassen, Jan, and Leo Lucassen. 2009. “The Mobility Transition Revisited, 1500–1900: What the Case of Europe can Offer to Global History.” Journal of Global History 4 (3): 347–377.

- Manz, Stefan. 2014. Constructing a German Diaspora: The “Greater German Empire,” 1871–1914. New York: Routledge.

- Mata-Codesal, Diana. 2013. “Linking Social and Financial Remittances in the Realms of Financial Know-How and Education in Rural Ecuador.” Migration Letters 10 (1): 23–32.

- Mazlish, Bruce, and Ralph Buultjens. 1993. Conceptualizing Global History. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Meissner, Fran, and Steven Vertovec. 2015. “Comparing Super-Diversity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (4): 541–555.

- Meseguer, Covadonga, and Katrina Burgess. 2014. “International Migration and Home Country Politics.” Studies in Comparative International Development 49 (1): 1–12.

- Mikoletzky, Juliane. 1988. Die deutsche Amerika-Auswanderung des 19. Jahrhunderts in der zeitgenössischen fiktionalen Literatur. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer.

- Müller-Funk, Lea. 2019. Egyptian Diaspora Activism During the Arab Uprisings: Insights From Vienna and Paris. London: Routledge.

- Müller-Funk, Lea. 2020. “Fluid Identities, Diaspora Youth Activists and the (Post-)Arab Spring: How Narratives of Belonging Can Change Over Time.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1112–1128. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554300.

- Østergaard-Nielsen, Eva. 2000. “Trans-state Loyalties and Politics of Turks and Kurds in Western Europe.” Sais Review 20 (1): 23–38.

- Østergaard-Nielsen, Eva. 2003. “The Politics of Migrants’ Transnational Political Practices.” International Migration Review 37 (3): 760–786.

- Ostergren, Robert C. 1998. “The Euro-American Settlement of Wisconsin, 1830–1920.” In Wisconsin Land and Life, edited by R. C. Ostergren and R. Vale, 137–162. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Osterhammel, Jürgen. 2014. The Transformation of the World: A Global History of the Nineteenth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Pérez-Armendáriz, Clarisa, and David Crow. 2010. “Do Migrants Remit Democracy? International Migration, Political Beliefs, and Behavior in Mexico.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (1): 119–148.

- Pestel, Friedemann. 2017. “French Revolution and Migration after 1789.” http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/europe-on-the-road/political-migration-exile/friedemann-pestel-french-revolution-and-migration-after-1789#Transferprocessesbetweenmigrsandhostsocieties.

- Piper, Nicola. 2009. “Temporary Migration and Political Remittances: The Role of Organisational Networks in the Transnationalisation of Human Rights.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 8 (2): 215–243.

- Piper, Nicola and Stefan Rother. 2020. “Political Remittances and the Diffusion of a Rights-Based Approach to Migration Governance: The Case of the Migrant Forum in Asia (MFA).” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1057–1071. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554291.

- Portes, Alejandro. 1997. “Immigration Theory for a New Century: Some Problems and Opportunities.” International Migration Review 31: 799–825.

- Portes, Alejandro. 2003. “Conclusion: Theoretical Convergencies and Empirical Evidence in the Study of Immigrant Transnationalism.” International Migration Review 37 (3): 874–892.

- Rother, Stefan. 2009. “Changed in Migration? Philippine Return Migrants and (Un) Democratic Remittances.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 8 (2): 245–274.

- Schmidt, Jürgen. 2020. “The German Labour Movement, 1830s to 1840s: Early Efforts at Political Transnationalism.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1025–1039. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554283.

- Sewell, William. 1996. “Historical Events as Transformations of Structures: Inventing Revolution at the Bastille.” Theory and Society 25 (6): 841–881.

- Shain, Yossi. 1999. “The Mexican-American Diaspora's Impact on Mexico.” Political Science Quarterly 114 (4): 661–691.

- Sinatti, Giulia. 2006. “Diasporic Cosmopolitanism and Conservative Translocalism: Narratives of Nation Among Senegalese Migrants in Italy.” Studies in Ethnicity and Nationalism 6 (3): 30–50.

- Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoğlu. 1994. Limits of Citizenship: Migrants and Postnational Membership in Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago.

- Tabar, Paul. 2014. “‘Political Remittances’: The Case of Lebanese Expatriates Voting in National Elections.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 35 (4): 442–460.

- Takenaka, Ayumi. 2020. “The Paradox of Diaspora Engagement: A Historical Analysis of Japanese State-Diaspora Relations.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1129–1145. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1554301.

- Tarrow, Sidney. 2005. The New Transnational Activism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Van Hear, Nicholas, and Robin Cohen. 2017. “Diasporas and Conflict: Distance, Contiguity and Spheres of Engagement.” Oxford Development Studies 45 (2): 171–184.

- Vernitski, Anat. 2005. “Russian Revolutionaries and English Sympathizers in 1890s London: the Case of Olive Garnett and Sergei Stepniak.” Journal of European Studies 35 (3): 299–314.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2009. Transnationalism. London; New York: Routledge.

- Waldinger, Roger, and Nancy Green. 2016. “Introduction.” In A Century of Transnationalism: Immigrants and Their Homeland Connections, edited by N. Green, and R. Waldinger, 1–31. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- Werner, Michael, and Bénédicte Zimmermann. 2004. De la comparaison à l'histoire croisée. Paris: Seuil.

- Weyland, Kurt. 2009. “The Diffusion of Revolution: ‘1848’ in Europe and Latin America.” International Organization 63 (3): 391–423.

- White, Anne. 2011. “The Mobility of Polish Families in the West of England: Translocalism and Attitudes to Return.” Studia Migracyjne - Przeglad Polonijny 37 (1): 11–32.

- Wimmer, Andreas, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2002. “Methodological Nationalism and Beyond: Nation–State Building, Migration and the Social Sciences.” Global Networks 2 (4): 301–334.

- Younes, Miriam. 2012. “Die Verwirrung der Zöglinge Najafs - Reformkonzepte in der und über die Hawza im frühen 20. Jahrhundert.” Asiatische Studien 66 (3): 711–748.