Mass immigration has become an enduring feature of open, integrated and dynamic economies, with most wealthy post-industrial societies experiencing large migration inflows in recent years (OECD Citation2017). At the same time, public opposition to immigration has become a major disruptive force in developed democracies, with the emergence of a new family of political parties, the populist radical right (Mudde Citation2007), who draw their support primarily from voters who oppose immigration (Ivarsflaten Citation2008). Immigration is economically vital yet politically contentious. Indeed, the present political and academic relevance of this topic area is greater than ever due to the Great Recession of 2008 which resulted in increased anti-immigrant sentiments in several countries (Billiet, Meuleman, and De Witte Citation2014; Kuntz, Davidov, and Semyonov Citation2017), large flows of refugees into both old and new immigration countries in Europe, and widespread political repercussions, with views of immigration for example playing a significant role in the British vote to leave the EU.

However, citizens vary widely in their views of migration overall (Meuleman, Davidov, and Billiet Citation2009; Ford and Lymperopoulou Citation2017), and not all migrant-receiving countries exhibit public hostility to migration to the same degree (Heath and Richards Citation2020). Understanding what drives these individual and cross-national variations in public support for or opposition to immigration is therefore an issue of central importance for academics and policymakers alike.

The goal of this special issue is to report findings from papers aiming to explain the drivers of attitudes toward immigration in European countries and how patterns vary across Europe. The articles in the special issue address questions such as: Do some members of European publics oppose immigration because they believe it threatens their economic interests, or because they see it as a threat to the national culture and values? How accurate are people's perceptions of the number of immigrants in their country, and do misperceptions lead to greater hostility towards immigration? To what extent are individuals’ perceptions of threat shaped by more fundamental influences such as basic human values, racist beliefs, group identities and the associated feelings of relative deprivation? How far do these shape feelings of threat or misperceptions of the volume of immigration?

All the articles in the special issue are comparative, comparing across twenty-one European countries. They explore how attitudes differ across countries – not only how countries differ in their support for immigration but also how consensual or internally-divided countries are. Which countries are most supportive of immigration? Which are the most divided? The articles also explore whether processes operate in similar ways right across Europe. Do personal experiences, values, identities, attitudes and beliefs play greater or less important roles depending on the economic, political or social context?

The articles in the special issue are all based on analysis of the recent immigration module included in the seventh wave (2014–15) of the European Social Survey (ESS) (Heath et al. Citation2014; European Social Survey Citation2016). All of the guest co-editors of the special issue (who also author several papers in the themed issue) were part of the questionnaire design team for the immigration module (Anthony Heath, as coordinator, with (alphabetically) Eldad Davidov, Robert Ford, Eva G. T. Green, Alice Ramos and Peter Schmidt).

The ESS is a high quality input-harmonized cross-national study, based on representative probability samples of national populations (aged 15 and older) in countries across Europe, designed and conducted according to state-of-the-art methodological principles (Jowell et al. Citation2007). Fieldwork was carried out between August 2014 and December 2015 with achieved sample sizes ranging from 1,224–3,045. (See Appendix Table A1 for further details.)

The ESS is the most highly-regarded comparative survey research programme in the world. Its greatest strengths are its insistence on rigorous standardised methods of survey sampling, data collection, questionnaire design and implementation, ensuring that each country follows the same protocols, and thus providing the highest degree of comparability between countries. The ESS is also notable for its transparency, with full details of the questionnaires, procedures, and data fully-documented and made available online with open access for users. Detailed documentation of the data and its collection procedures may be found under www.europeansocialsurvey.org.

The ESS data in the 2014–15 immigration module were collected in 21 West and East European countries (including Israel), in both old and new immigration societies. Respondents were asked questions not only about attitudes toward immigration and related topics, but also questions measuring their sociodemographic and socioeconomic background, their value orientations, and other major individual characteristics that are likely to explain opposition to immigration.

The 2014–15 immigration module was, in part, a repeat of the module conducted in the very first wave of the ESS in 2002/3 (Card, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2005). As in the first immigration module, the central outcome consists of attitudes to immigration. The module distinguishes between support for different types of migrants from various source countries, attitudes toward different criteria for accepting or excluding migrants, and attitudes toward policies for integrating migrants into the host country. In addition, the module contains a wide range of explanatory measures derived from contemporary theories developed in the immigration literature (for an overview, see Ceobanu and Escandell Citation2010; Rustenbach Citation2010). In addition, both sociodemographic variables and value orientations – (particularly but not only) conservation and universalism (Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012; Davidov et al. Citation2008; Ramos, Pereira, and Vala Citation2016) – are included in the ESS. The cross-national comparability of the scales developed from these items has been rigorously checked (Davidov, Cieciuch, and Schmidt Citation2018).

The first innovation of the 2014–15 module was to refine measurement of opposition to immigration by including more questions regarding migrants of different origins, specifically Jewish, Muslim and Roma, in order to allow the examination of attitudes toward groups that are at the heart of contemporary debates. A second innovation in the module was an experimental design (Ford Citation2016) for assessing attitudes toward immigrants of different types: a question with an experimental design was added with country-specific target groups of immigrants together with variations in the economic status of the immigrant. The great advantage of this experimental design is that it gives the respondents specific target groups to consider rather than the vague and decontextualised categories used in other parts of the module (and in a great deal of cross-national research). The use of specific target groups should reduce ‘noise’ (unexplained variation) and strengthen relationships with other variables. It also has the advantage that it enables exploration of the interaction between ethnic origins and the economic status of migrants (see Ford and Mellon Citation2020).

A third innovation of the module is the development of a new question to measure the ethnic background of respondents. Ethnic minorities with a migration background may have different attitudes toward immigrants compared to other ethnic groups or to members of the majority group because of their own or their family's history of migration. In previous research in Europe it has been common to measure ethnicity with proxies based on the country of birth of the respondent and of his/her parents. While in many contexts this has, up to now, provided a reasonable proxy for ethnicity, it fails to identify the growing number of ‘third generation’ members of minorities within European countries, and it also ignores internal ethnic differences due for example to the movement of national boundaries after the two world wars rather than to the movement of individuals between nation-states. Therefore the 2014–15 module includes a new and much more precise measure, directly tapping ethno-national origins (thus capturing both indigenous national minorities as well as ethnic minorities with an immigration background). This measure provides further information about the diversity of a country's population and how this diversity may be related to anti-immigrant sentiment (Heath et al. Citation2014; see also Schneider and Heath Citation2020).

A further central innovation of the 2014–15 module has been the inclusion and implementation of a number of new or refined explanatory concepts. These include racism (Bobo and Hutchings Citation1996; Blumer Citation1958; Ford Citation2008; Sears and Henry Citation2003; Vala et al. Citation2012), national identification (Blank and Schmidt Citation2003; Coenders and Scheepers Citation2003; Heath and Tilley Citation2005; Pehrson and Green Citation2010; Raijman et al. Citation2008), and sentiments of fraternal relative deprivation (Smith et al. Citation2012). In addition, established concepts from the 2002–3 module have been retained or refined. These include economic and symbolic threat (Esses et al. Citation2001; Green and Staerklé Citation2013; Meuleman, Abts, et al. Citation2018; Quillian Citation1995; Raijman and Semyonov Citation2004; Scheepers, Gijsberts, and Coenders Citation2002; Stephan and Stephan Citation2000), contact with immigrants (Escandell and Ceobanu Citation2009; Green et al. Citation2016; Pettigrew Citation1998; Pettigrew and Tropp Citation2006; Semyonov and Glikman Citation2009), perceived group size of the immigrants in the country (Schlueter and Wagner Citation2008; Semyonov et al. Citation2004), and subjective feeling of social distance from immigrants (Bogardus Citation1947; Schlueter and Wagner Citation2008).

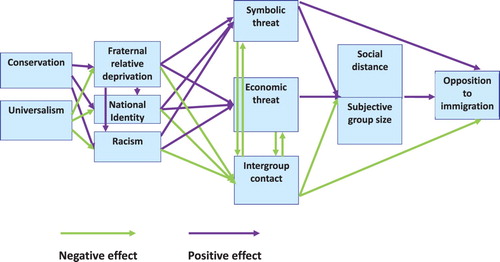

The established literature suggests that opposition to immigration increases with greater social distance from immigrants, greater perceived size of the immigrant population, and greater threat (symbolic or economic) attributed to immigrants. By way of contrast, contact with immigrants reduces opposition to immigration. Individuals who feel that their own group is deprived compared to immigrants, respondents reporting higher levels of racism (either biological or cultural), and those expressing stronger nationalist sentiments are also expected to be more opposed to immigrants. Finally, conservative individuals are likely to be more negative, and universalist individuals to be more positive, toward immigrants.

sketches a possible causal chain (or associations) between these different individual-level variables that potentially explain opposition to immigration. Papers in the special issue focus on different parts of this overall theoretical model, explain the mechanisms linking the variables of interest, and test these associations empirically. We do not however attempt to empirically test the whole model simultaneously since there are too many possible alternative model specifications. Moreover, the causal processes may operate in some cases in the reverse direction, leading to endogeneity problems (Paxton, Hipp, and Marquart-Pyatt Citation2011). The ESS data are cross-sectional and do not allow us to test for the direction of causality without using supplementary experimental or panel data. Therefore, the specific location of each explanatory element in the model may change depending on the theoretical reasoning about the mechanism linking it to opposition to immigration.

Figure 1. A possible causal chain between different individual-level predictors of opposition to immigration.

Note: For simplicity some of the direct effects were left out. Some of the effects may operate also in the other direction.

In addition to the individual characteristics which are the primary focus of , previous research has also explored characteristics of the countries (or regions) in order to explain cross-country variation in opposition to immigration. These contextual variables include, for example, information on the size of the migrant population (e.g. Green Citation2009; Quillian Citation1995; Schlueter and Wagner Citation2008; Schneider Citation2008; Semyonov, Raijman, and Gorodzeisky Citation2006; Semyonov et al. Citation2004), a country's immigration policies (e.g. Hooghe and de Vroome Citation2015; Schlueter, Meuleman, and Davidov Citation2013), and claims by the national media about immigration (Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Citation2009; Koopmans and Olzak Citation2004; Schlueter and Davidov Citation2013; Statham and Tumber Citation2013; Strabac and Listhaug Citation2008). This literature suggests that, in countries where policies are more supportive of immigrant integration, attitudes toward immigration are also more positive. However, in countries where the relative size of the immigrant population is larger and media coverage of immigration issues is more negative, respondents might view immigration more negatively.

Running through the papers in the special issue are two recurring themes. First, the processes outlined in the model ( above) are very largely supported. Most notably, in line with the model, the analyses reported in this special issue break new ground by showing the importance of biological and cultural racism and of group identities and associated feelings of group relative deprivation. These findings complement earlier approaches to the study of attitudes to immigration which tended to adopt more individualistic models focused on instrumental and economic grounds for anti-immigrant sentiment. The articles in the special issue tend to emphasise the importance both of social identities and processes and of normative beliefs and attitudes as well as of material self-interest.

The second theme is that national contexts really matter. The strength and significance of the various processes identified in the overall model tend to play out somewhat differently in different national contexts. In a sense there are several different sorts of European publics, depending on each country's history of immigration and emigration, as well as on the nature of the integration policies which governments have pursued, the normative signals which these provide, the political context and the strength of far-right parties.

The first three articles in the special issue all focus primarily on differences between the countries included in the 2014–15 wave of the ESS. The first, authored by Heath and Richards (Citation2020), ‘Contested boundaries: consensus and dissensus in European attitudes to immigration’, explores differences in attitudes toward immigration both between and within countries. The authors draw on new questions, included in the ESS for the first time in 2014–15, about willingness to accept culturally distinct groups of migrants such as Muslims. These new measures yield additional insights about the nature of symbolic boundaries since they directly tap one of the most salient boundaries in contemporary migration discourse. The findings distinguish three classes of individual attitudes, labelled ‘restrictive’, ‘selective’ and ‘unselective’. The proportions of individuals belonging to these classes vary across European countries, which fit into more or less distinct East European, North European and West European sets. These three sets display differing levels both of support for immigration and of internal homogeneity. For example, some eastern European countries such as the Czech Republic, are rather unfavourable toward immigration overall but are also fairly consensual. In contrast, North European countries such as Norway tend to be much more positive about immigration in the aggregate but at the same time are quite divided internally. This pattern is also reflected in the degree of socioeconomic polarisation within each country, and helps to explain why there may be strong anti-immigrant parties even in countries which are, on average, quite favourable toward migration.

The second article, authored by Ford and Mellon (Citation2020): ‘The skills premium and the ethnic premium: A cross-national experiment on European attitudes to immigrants’, also focusses on the ways in which attitudes differ across Europe. Importantly, the paper takes a new approach to a longstanding issue in comparative research – the trade-off between direct equivalence and functional equivalence. While previous studies have focussed on direct equivalence by asking about the same migrant groups in multiple contexts where their relevance varies, Ford and Mellon focus on functional equivalence by asking about the largest poorer European and non-European source countries for migration in each specific destination country, therefore ensuring that the migrant group asked about is maximally relevant locally as well as functionally comparable across countries. Their first key finding is that professional migrants are significantly more acceptable than unskilled labourers in every single one of the 21 national contexts, though with considerable variation in the size of the effect. Secondly, the experiment reveals a general, but not universal, preference for migrants from European source countries over migrants from non-European source countries. This ‘European premium’ is in almost all cases smaller than the ‘skills premium’, and varies considerably between national contexts, suggesting that the impact of migrant origins is sensitive to local contextual conditions. Thirdly, the two experimental treatment effects appear to be only modestly related to each other. The pooled sample suggests a significant interaction between the treatments, with the preference for European-origin migrants being somewhat stronger when migrants have low skills, but this interaction is inconsistent.

The third article, authored by Schneider and Heath (Citation2020), ‘Ethnic and cultural diversity in Europe: validating measures of ethnic and cultural background’ shifts the focus to a rather unexplored topic, namely the ethnic classification of immigrants in Europe. After all, socio-cultural and ethnic origin can be a powerful predictor of social attitudes and behaviours but, unlike the classical countries of immigration such as Australia, Canada and the USA, there is no standard measure in Europe for measuring ethnic background. The authors report a new measure of ethnic classification, developed for the ESS and trialled in the ESS wave 7 (2014/2015). They describe its underlying theoretical concepts, structure and classification criteria and report a range of substantive findings. Schneider and Heath show that the new measure has both criterion and predictive validity: it predicts whether respondents identify themselves as belonging to an ethnic minority and whether they feel that theirs is a group which is discriminated against. It also predicts strength of national identity and attitudes toward immigration. A particular advantage of the new measure is that it identifies both indigenous or (sub)national minorities as well those with a migration background and thus gives a fuller account of diversity. The paper shows that in some countries subnational minorities are quite distinctive, for example in their feelings of being discriminated against and in their low levels of national attachment.

The next set of articles pick up on some of the key explanatory mechanisms outlined in above. The fourth article, ‘Direct and indirect predictors of opposition to immigration in Europe: Individual values, cultural values, and symbolic threat’, is authored by Eldad Davidov, Daniel Seddig, Anastasia Gorodzeisky, Rebeca Raijman, Peter Schmidt and Moshe Semyonov (Citation2020). The article focusses on the role of the basic human values of conservation and universalism (shown on the left of the model displayed in ). The article shows that these basic human values are quite closely linked with feelings of threat: individuals who hold conservation values tend to perceive greater threats from immigration, while individuals who hold to universalism values perceive lesser threat. However, these patterns did not hold true with equal force in different countries. In countries such as the eastern European ones, it made less difference which of these basic human values individuals espoused. It appears that in these countries individuals are more embedded in a national culture and the character of the national culture tends to supplant individual differences in values with little room for intellectual and affective autonomy. In contrast, there is more room for individual values to make a difference in western or northern countries where the public is less embedded in a national culture and where there is greater room for individuals’ intellectual and affective autonomy.

The fifth article, authored by Ramos, Pereira, and Vala (Citation2020), ‘The impact of biological and cultural racisms on attitudes toward immigrants and immigration public policies’, focuses on the role of biological and cultural racism as explanations of negative views toward immigration. Firstly, Alice Ramos and her colleagues show that respondents are generally more willing to express feelings of cultural racism than of biological racism: in other words biological racism is more anti-normative than cultural racism. The results also suggest that both biological and cultural racism predict opposition to immigration and adhesion to ethnic criteria for the selection of immigrants. They also find that the relationship between racism and opposition to immigration is mediated by perceptions of threat. This suggests the important conclusion that threat perceptions constitute justifying mechanisms which people who endorse racist beliefs use to legitimise beliefs about racial inferiority which violate widely held societal norms. This mediating process is particularly relevant in more democratic societies (as judged by the Quality of Democracy Index) where discrimination based on biological racism is forbidden by law. Cross-level interactions of multilevel models demonstrated the moderating role of the quality of democracy on this mediating process.

The sixth paper, authored by Meuleman, Koen, et al. (Citation2020): ‘Economic conditions, group relative deprivation and ethnic threat perceptions: a cross-national perspective’, shifts the focus of the analysis to the concept of group relative deprivation, a classic sociological concept developed by Runciman (Citation1966). The key idea is that perceptions of threat depend not just on one's own individual situation but on that of one's group: if one feels that one's group is unfairly deprived of benefits to which it is entitled, one is more likely to feel threatened by immigration. The paper systematically examines the effects of group relative deprivation and finds that it exerts a significant and robust effect on perceptions of threat. This holds true even after taking account of other key components of the overall model displayed in such as economic conditions, value orientations and intergroup contact. It also appears that group relative deprivation explains how adverse economic conditions are translated into perceptions of ethnic threat: feelings of relative deprivation appear to be the crucial mechanism mediating the link between adverse economic conditions and negative attitudes to immigration. In addition, the analysis shows significant contextual patterns, too: in countries experiencing higher levels of long-term unemployment, group relative deprivation is markedly more prevalent.

The seventh article, authored by Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Citation2020), ‘Perceptions and misperceptions: actual size, perceived size and opposition to immigration in European societies’, focusses on another key component of the model shown in . The paper finds that, in all countries without exception, citizens tend to overestimate the size of the foreign-born population, although inflated perceptions are more likely among individuals who are vulnerable in socio-economic terms. In turn, misperceptions of the size of the immigrant population play a more important role than does factual reality in shaping public views and attitudes toward immigration. Although perceived size is not totally detached from the actual size of the foreign-born population, the discrepancy between actual and perceived size is found to be a more powerful predictor of opposition to immigration than actual size. For example, although the size of the international refugee population in 2015 was only slightly higher than in 1992, the recent refugee flow was perceived in western societies as uniquely large and threatening for the receiving countries. Thus, the more inflated is the misperception, the more pronounced is opposition to immigration. The impact of misperceptions also appears to be more pronounced in countries with larger foreign-born populations.

The final three articles introduce various contextual (country-level) measures for understanding how patterns vary across countries, focussing on integration policies, media claims about immigration, and far-right mobilisation. The eighth article is authored by Green et al. (Citation2020). ‘When integration policies shape the impact of intergroup contact on threat perceptions: A multilevel study across 20 European countries’ investigates how a country's migrant integration policies (as assessed by the Migrant Integration Policy Index (MIPEX) indicator) shape the relationship between intergroup contact and perceptions of economic and cultural threat. Multilevel analysis, investigating simultaneously the role of individual characteristics and national policies, shows that individual contact is associated with reduced feelings of symbolic and economic threat while at the same time more liberal and inclusive integration policies (a high MIPEX score) are related to higher average rates of everyday contact and lower average perceptions of symbolic threat in a country. In addition, while contact was generally related to lower perceptions of symbolic threat, the threat-reducing impact of everyday interactions was stronger in countries with relatively more inclusive integration policies than in countries with less inclusive policies. This suggests that the national policy context has the power both to facilitate contact and to reinforce the beneficial effects of contact. Beyond the impact of integration policies, these findings suggest more generally that the normative setting in which individuals are embedded can be important for understanding the public's reactions to immigration. (For another example of this process at work see Blinder, Ford, and Ivarsflaten Citation2013).

The ninth article, authored by Schlueter, Masso, and Davidov (Citation2020), ‘What factors explain anti-Muslim prejudice? A comparative assessment of Muslim population size, institutional characteristics and immigration-related media claims’, examines potential explanations that could account for differences between countries in levels of anti-Muslim prejudice (Statham Citation2016). The results indicate that a larger share of Muslims in the population, more liberal integration policies and greater state support of religion are all associated with lower levels of negative attitudes toward Muslim immigration. In other words, the presence of a relatively large number of Muslims in a country did not result in feelings of greater threat and negative attitudes. Instead, it appears to provide more opportunities for positive contact and helps to reduce negative sentiments. Furthermore, more liberal integration policies (as judged by the Migrant Integration Policy Index) seem to be associated with more positive attitudes, possibly because liberal integration policies are markers of societal norms which provide signals to respondents that immigrants are welcome in their country. Similarly, state support for the religious practices of all religions does not have the feared negative effects. Again, respondents may perceive these policies as normative signals from the state that the practice of any religion in the country is accepted and welcome. Finally, in contrast with expectations, cross-national differences in the frequency of negative news reports related to immigration, as measured by the ESS media claims data (European Social Survey Citation2017), were unrelated to attitudes toward Muslim immigration.

The tenth article, authored by McLaren and Paterson (Citation2020), ‘Generational change and attitudes to immigration’, examines the extent to which generational change is likely to be producing attitude change on the issue of immigration in Europe. The authors investigate whether there are significant differences in anti-immigration sentiment between older and younger generations of Europeans, focussing on the roles that education and far-right mobilisation are likely to play in the process of generational change. The results suggest that, in contexts where the far-right has been strongest during people's formative years, the youngest generations are the most negative about immigration, with education limiting this effect to only a small extent. In contrast, in contexts in where the far-right has been less influential during the formative years of the youngest cohorts, it does appear that these youngest cohorts are more positive about immigration, especially among young people with higher levels of education. It therefore appears that, if European societies and leaders wish to avoid the divisive events that anti-immigration sentiment can lead to, they will need to understand how the mobilising effects of the far-right can be countered. Education may help to limit this mobilising effect, but it appears that this may only have a minor impact. Political elites may need to learn how they might re-frame immigration in ways that might be more appealing among younger cohorts.

The articles in the special issue thus show that there are some common processes underlying anti-immigration sentiments. But at the same time they also show that the operation of these processes is far from uniform. The national economic, cultural and political contexts can powerfully exacerbate or weaken these processes. European publics are thus quite heterogeneous in public support for or opposition to immigration, in their extent of internal unity, and in the drivers associated with anti-immigration sentiment. This heterogeneity may well help to explain why it can prove so difficult politically to agree a common European approach to managing issues of immigration such as the 2015/16 refugee crisis, for example.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the ESS ERIC Core Scientific Team led by Rory Fitzgerald and the ESS local teams in the participating countries for their support in developing the 2014–5 module of the ESS on attitudes to immigration. We would also like to thank the British Academy for their conference which initiated this special issue, the contributors to this themed issue, and the journal editor, Professor Paul Statham, for his enthusiasm about the topic and his continuous support to help us get the special issue published. The articles accepted for this themed issue were rigorously reviewed and we also appreciate the effort of many anonymous external JEMS reviewers. We hope that this special issue will provide immigration researchers with an important and informative reference on the explanation of anti-immigrant sentiments, and will be helpful for researchers and policy makers alike. Eldad Davidov would like to thank the University of Zurich Research Priority Program Social Networks for their support. All guest editors would like to thank Lisa Trierweiler for English proofreading of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Anthony Heath http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3731-587X

Eldad Davidov http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3396-969X

Alice Ramos http://orcid.org/0000-0001-9512-0571

Additional information

Funding

References

- Billiet, Jaak, Bart Meuleman, and Hans De Witte. 2014. “The Relationship between Ethnic Threat and Economic Insecurity in Times of Economic Crisis: Analysis of European Social Survey Data.” Migration Studies 2 (2): 135–161.

- Blank, Thomas, and Peter Schmidt. 2003. “National Identity in a United Germany: Nationalism or Patriotism? An Empirical Test with Representative Data.” Political Psychology 24 (2): 289–312.

- Blinder, Scott, Robert Ford, and Elisabeth Ivarsflaten. 2013. “The Better Angels of Our Nature: How the Antiprejudice Norm Affects Policy and Party Preferences in Great Britain and Germany.” American Journal of Political Science 57 (4): 841–857.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1958. “Race Prejudice as a Sense of Group Relation.” The Pacific Sociological Review 1: 3–7.

- Bobo, Lawrence, and Vincent L. Hutchings. 1996. “Perceptions of Racial Group Competition: Extending Blumer’s Theory of Group Position to a Multiracial Social Context.” American Sociological Review 61 (6): 951–972.

- Bogardus, Emory S. 1947. “Measurement of Personal-group Relations.” Sociometry 10 (4): 306–311.

- Boomgaarden, Hajo G., and Rens Vliegenthart. 2009. “How News Content Influences Anti-Immigration Attitudes: Germany, 1993–2005.” European Journal of Political Research 48 (4): 516–542.

- Card, David, Christian Dustmann, and Ian Preston. 2005. Understanding Attitudes to Immigration: The Migration and Minority Module of the First European Social Survey. Discussion Paper Series CDP No. 03/05. London: Centre for Research Analysis of Migration (CReAM).

- Ceobanu, Alin M., and Xavier Escandell. 2010. “Comparative Analyses of Public Attitudes Toward Immigrants and Immigration Using Multinational Survey Data: A Review of Theories and Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 36: 309–328.

- Coenders, Marcel, and Peer Scheepers. 2003. “The Effect of Education on Nationalism and Ethnic Exclusionism: An International Comparison.” Political Psychology 24: 313–343.

- Davidov, Eldad, Jan Cieciuch, and Peter Schmidt. 2018. “The Cross-country Measurement Comparability in the Immigration Module of the European Social Survey 2014–15.” Survey Research Methods 12 (1): 15–27. doi:10.18148/srm/2018.v12i1.7212.

- Davidov, Eldad, and Bart Meuleman. 2012. “Explaining Attitudes Towards Immigration Policies in European Countries: The Role of Human Values.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (5): 757–775.

- Davidov, Eldad, Bart Meuleman, Jaak Billiet, and Peter Schmidt. 2008. “Values and Support for Immigration: A Cross-Country Comparison.” European Sociological Review 24 (5): 583–599. doi:10.1093/esr/jcn020.

- Davidov, Eldad, Daniel Seddig, Anastasia Gorodzeisky, Rebeca Raijman, Peter Schmidt, and Moshe Semyonov. 2020. “Direct and Indirect Predictors of Opposition to Immigration in Europe: Individual Values, Cultural Values, and Symbolic Threat.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 553–573. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550152.

- Escandell, Xavier, and Alin M. Ceobanu. 2009. “When Contact with Immigrants Matters: Threat, Interethnic Attitudes and Foreigner Exclusionism in Spain’s Comunidades Autónomas.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 32 (1): 44–69. doi:10.1080/01419870701846924.

- Esses, Victoria M., John F. Dovidio, Lynne M. Jackson, and Tamara L. Armstrong. 2001. “The Immigration Dilemma: The Role of Perceived Group Competition, Ethnic Prejudice, and National Identity.” Journal of Social Issues 57 (3): 389–412.

- European Social Survey. 2016. ESS7-2014 Data File Edition 2.1. NSD - Norwegian Centre for Research Data, Norway – Data Archive and distributor of ESS data for ESS ERIC. http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/download.html?file=ESS7e02_1&y=2014.

- European Social Survey. 2017. Data from Media Claims, Edition 1.0, Round 7. http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/download.html?file=ESS7MCe01&y=2014.

- Ford, Robert. 2008. “Is Racial Prejudice Declining in Britain?” The British Journal of Sociology 59 (4): 609–636.

- Ford, Robert. 2016. “Who Should We Help? An Experimental Test of Discrimination in the British Welfare State.” Political Studies 64 (3): 630–650.

- Ford, Robert, and Kitty Lymperopoulou. 2017. “Immigration: How Attitudes in the UK Compare to Europe.” In British Social Attitudes: The 34th Report, edited by Miranda Phillips, Eleanor A. Taylor, and Ian Simpson. London: NatCen Social Research. http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/latest-report/british-social-attitudes-34/immigration.aspx.

- Ford, Robert, and Jonathan Mellon. 2020. “The Skills Premium and the Ethnic Premium: A Cross-National Experiment on European Attitudes to Immigrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 512–532. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550148.

- Gorodzeisky, Anastasia, and Moshe Semyonov. 2020. “Perceptions and Misperceptions: Actual Size, Perceived Size and Opposition to Immigration in European Societies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 612–630. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550158.

- Green, Eva G. T. 2009. “Who Can Enter? A Multilevel Analysis on Public Support for Immigration Criteria Across 20 European Countries.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 12 (1): 41–60.

- Green, Eva G. T., Oriane Sarrasin, Robert Baur, and Nicole Fasel. 2016. “From Stigmatized Immigrants to Radical Right Voting: A Multilevel Study on the Role of Threat and Contact.” Political Psychology 37 (4): 465–480.

- Green, Eva G. T., and Christian Staerklé. 2013. “Migration and Multiculturalism.” In Oxford Handbook of Political Psychology, edited by Leonie Huddy, David O. Sears, and Jack S. Levy, 852–889. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Green, Eva G. T., Emilio Paolo Visintin, Oriane Sarrasin, and Miles Hewstone. 2020. “When Integration Policies Shape the Impact of Intergroup Contact on Threat Perceptions: A Multilevel Study Across 20 European Countries.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 631–648. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550159.

- Heath, Anthony F., and Lindsay Richards. 2020. “Contested Boundaries: Consensus and Dissensus in European Attitudes to Immigration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 489–511. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550146.

- Heath, Anthony F., Peter Schmidt, Eva G.T. Green, Alice Ramos, Eldad Davidov, and Robert Ford. 2014. “Attitudes towards Immigration and their Antecedents.” ESS7 Rotating Modules. http://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/docs/round7/questionnaire/ESS7_immigration_final_module_template.pdf.

- Heath, Anthony F., and James R. Tilley. 2005. “British National Identity and Attitudes Towards Immigration.” International Journal on Multicultural Societies 7 (2): 119–132.

- Hooghe, Marc, and Thomas de Vroome. 2015. “How Does the Majority Public React to Multiculturalist Policies? A Comparative Analysis of European Countries.” American Behavioral Scientist 59 (6): 747–768.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth. 2008. “What Unites Right-wing Populists in Western Europe? Re-examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (1): 3–23.

- Jowell, Roger, Caroline Roberts, Rory Fitzgerald, and Gillian Eva. 2007. Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally, Lessons From the European Social Survey. London: Sage.

- Koopmans, Ruud, and Susan Olzak. 2004. “Right-Wing Violence and the Public Sphere in Germany: The Dynamics of Discursive Opportunities.” American Journal of Sociology 110 (1): 198–230. doi:10.1086/386271.

- Kuntz, Anabel, Eldad Davidov, and Moshe Semyonov. 2017. “The Dynamic Relations between Economic Conditions and Anti-immigrant Sentiment: A Natural Experiment in Times of the European Economic Crisis.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 58 (5): 392–415. doi:10.1177/0020715217690434.

- McLaren, Lauren, and Ian Paterson. 2020. “Generational Change and Attitudes to Immigration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 665–682. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550170.

- Meuleman, Bart, Koenraad Abts, Koen Slootmaeckers, and Cecil Meeusen. 2018. “Differentiated Threat and the Genesis of Prejudice. Group-Specific Antecedents of Homonegativity, Islamophobia, Anti-Semitism and Anti-Immigrant Attitudes.” Social Problems Advance online publication. doi:10.1093/socpro/spy002.

- Meuleman, Bart, Eldad Davidov, and Jaak Billiet. 2009. “Changing Attitudes Toward Immigration in Europe, 2002–2007: A Dynamic Group Conflict Theory Approach.” Social Science Research 38 (2): 352–365.

- Meuleman, Bart, Abts Koen, Peter Schmidt, Thomas F. Pettigrew, and Eldad Davidov. 2020. “Economic Conditions, Group Relative Deprivation and Ethnic Threat Perceptions: A Cross-national Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 593–611. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550157.

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- OECD. 2017. International Migration Outlook 2017. Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2017-en.

- Paxton, Pamela, John R. Hipp, and Sandra Marquart-Pyatt. 2011. Non-Recursive Models: Endogeneity, Reciprocal Relationships and Feedback Loops. London: Sage.

- Pehrson, Samuel, and Eva G. T. Green. 2010. “Who We Are and Who Can Join Us: National Identity Content and Entry Criteria for New Immigrants.” Journal of Social Issues 66 (4): 695–716.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F. 1998. “Intergroup Contact Theory.” Annual Review of Psychology 49: 65–85.

- Pettigrew, Thomas F., and Linda R. Tropp. 2006. “A Meta-Analytic Test of Intergroup Contact Theory.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 90 (5): 751–783. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.90.5.751.

- Quillian, Lincoln. 1995. “Prejudice as a Response to Perceived Group Threat: Population Composition and Anti-Immigrant and Racial Prejudice in Europe.” American Sociological Review 60 (4): 586–611.

- Raijman, Rebeca, Eldad Davidov, Peter Schmidt, and Oshrat Hochman. 2008. “What Does a Nation Owe Non-Citizens? National Attachments, Perception of Threat and Attitudes Towards Granting Citizenship Rights in a Comparative Perspective.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49 (2–3): 195–220.

- Raijman, Rebeca, and Moshe Semyonov. 2004. “Perceived Threat and Exclusionary Attitudes Towards Foreign Workers in Israel.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (5): 780–799.

- Ramos, Alice, Cicero Pereira, and Jorge Vala. 2016. “Economic Crisis, Human Values and Attitudes Towards Immigration.” In Values, Economic Crisis and Democracy, edited by Malina Voicu, Ingvill C. Mochmann, and Hermann Dülmer, 104–137. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Ramos, Alice, Cicero Roberto Pereira, and Jorge Vala. 2020. “The Impact of Biological and Cultural Racisms on Attitudes Towards Immigrants and Immigration Public Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 574–592. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550153.

- Runciman, Walter G. 1966. Relative Deprivation and Social Justice: A Study of Attitudes to Social Inequality in Twentieth-Century England. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Rustenbach, Elisa. 2010. “Sources of Negative Attitudes Toward Immigrants in Europe: A Multi-level Analysis.” International Migration Review 44 (1): 53–77.

- Scheepers, Peer, Mérove Gijsberts, and Marcel Coenders. 2002. “Ethnic Exclusionism in European Countries: Public Opposition to Civil Rights for Legal Migrants as a Response to Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 18 (1): 17–34.

- Schlueter, Elmar, and Eldad Davidov. 2013. “Contextual Sources of Perceived Group Threat: Negative Immigration-related News Reports, Immigrant Group Size and Their Interaction, Spain 1996–2007.” European Sociological Review 29 (2): 179–191.

- Schlueter, Elmar, Anu Masso, and Eldad Davidov. 2020. “What Factors Explain Anti-Muslim Prejudice? An Assessment of the Effects of Muslim Population Size, Institutional Characteristics and Immigration-Related Media Claims.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 649–664. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550160.

- Schlueter, Elmar, Bart Meuleman, and Eldad Davidov. 2013. “Immigrant Integration Policies and Perceived Group Threat: A Multilevel Study of 27 Western and Eastern European Countries.” Social Science Research 42 (3): 670–682.

- Schlueter, Elmar, and Ulrich Wagner. 2008. “Regional Differences Matter: Examining the Dual Influence of the Regional Size of the Immigrant Population on Derogation of Immigrants in Europe.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 49 (2–3): 153–173.

- Schneider, Silke. 2008. “Anti-Immigrant Attitudes in Europe: Outgroup Size and Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 24 (1): 53–67.

- Schneider, Silke L., and Anthony F. Heath. 2020. “Ethnic and Cultural Diversity in Europe: Validating Measures of Ethnic and Cultural Background.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 533–552. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1550150.

- Sears, David O., and Patrick J. Henry. 2003. “The Origins of Symbolic Racism.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85 (2): 259–275.

- Semyonov, Moshe, and Anya Glikman. 2009. “Ethnic Residential Segregation, Social Contacts, and Anti-Minority Attitudes in European Societies.” European Sociological Review 25 (6): 693–708.

- Semyonov, Moshe, Rebeca Raijman, and Anastasia Gorodzeisky. 2006. “The Rise of Anti-foreigner Sentiment in European Societies, 1988-2000.” American Sociological Review 71 (3): 426–449.

- Semyonov, Moshe, Rebeca Raijman, Anat Yom-Tov, and Peter Schmidt. 2004. “Population Size, Perceived Threat, and Exclusion: A Multiple-Indicators Analysis of Attitudes Toward Foreigners in Germany.” Social Science Research 33 (4): 681–701.

- Smith, Heather J., Thomas F. Pettigrew, Gina M. Pippin, and S. Bialosiewicz. 2012. “Relative Deprivation: A Theoretical and Meta-Analytic Review.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 16 (3): 203–232.

- Statham, Paul. 2016. “How Ordinary People View Muslim Group Rights in Britain, the Netherlands, France and Germany: Significant ‘Gaps’ between Majorities and Muslims?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (2): 217–236. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2015.1082288.

- Statham, Paul, and Howard Tumber. 2013. “Relating News Analysis and Public Opinion: Applying a Communications Method as a ‘Tool’ to Aid Interpretation of Survey Results.” Journalism: Theory, Practice Criticism 14 (6): 737–753. doi:10.1177/1464884913491044.

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie White Stephan. 2000. “An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice.” In Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, edited by Stuart Oskamp, 23–45. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Strabac, Zan, and Ola Listhaug. 2008. “Anti-Muslim Prejudice in Europe: A Multilevel Analysis of Survey Data from 30 Countries.” Social Science Research 37 (1): 268–286. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.02.004.

- Vala, Jorge, Cicero R. Pereira, Marcus Lima, and Jacques-Philippe Leyens. 2012. “Intergroup Time Bias and Racialized Social Relations.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38 (4): 491–504.

Appendix

Table A1. Details of the surveys.