ABSTRACT

According to the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis, educational tracking will cause a polarisation of students’ school attitudes and behaviours: while students in high tracks will develop pro-school attitudes and behaviours, students in low tracks come to reject school. This hypothesis may be too crude, as the effect of tracking on school misconduct could vary across students. Based on the literature on the immigrant aspiration-achievement paradox and the oppositional culture hypothesis, I argue that the tracking effect will be different for students with a migration background. Using two-wave panel data from three educational systems with different types of tracking (i.e. England, the Netherlands, and Sweden), I find some support for the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis among students from the native majority, yet effect sizes are small. In line with the literature on the immigrant aspiration-achievement paradox, no support for the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis is found among students with a migration background. There are no statistically significant differences in these patterns across the three different educational systems.

In most educational systems students tend to be grouped on the basis of their academic performance or ability, a practice also known as tracking. The different ability groups are commonly referred to as track-levels, as they are hierarchically ordered, differ with respect to the pace at which material is offered and the content of this material, and prepare students for different educational trajectories (de Brabander Citation2000). Some countries, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, apply course-by-course tracking, implying that students are grouped within school for specific courses (Chmielewski, Dumont, and Trautwein Citation2013). In other countries, such as Belgium, Germany, and the Netherlands, students are separated into entirely different classes or schools for their full curriculum (i.e. full-curriculum tracking). Most research on tracking focuses on the effects of tracking on efficiency and inequality in student performance (Van de Werfhorst and Mijs Citation2010). Unfortunately, it is less clear how tracking affects the behavioural skills of students, including their school misconduct. School misconduct refers to students’ disobedience to school rules and norms, such as skipping class, and is related to school drop-out (Rumberger Citation1995) and delinquency (Jenkins Citation1997). Hence, it is an important predictor of school success.

Some scholars have hypothesised that tracking will lead to a polarisation of students with pro- and anti-school attitudes and behaviours (Berends Citation1995; Hargreaves Citation1967; Van Houtte Citation2006, Citation2017). In line with this ‘differentiation-polarization’ hypothesis, cross-sectional and case studies indicate that an anti-school culture is more prevalent in lower educational tracks (Hargreaves Citation1967; Van Houtte Citation2006, Citation2017). A handful of panel studies has also lent support for the hypothesis by showing that students in lower tracks exhibit lower levels of school adjustment or have more negative school attitudes, whilst accounting for students’ prior school adjustments or attitudes (Berends Citation1995; Müller and Hofmann Citation2016; Van Houtte Citation2016).

Despite these empirical findings, the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis has been criticised for being too simplistic, as the behaviour and attitudes of students greatly vary across students within tracks (Berends Citation1995; Gamoran and Berends Citation1987). Hence, the hypothesis may apply to some, but not all students. In line with this, cross-sectional research in Belgium suggests that track position is more strongly related to boys’ study involvement than that of girls (Van Houtte Citation2017). The present study contributes to the existing literature by examining variations in students’ behavioural response to tracking by migration background. Literature on the immigrant aspiration-achievement paradox indicates that children from immigrant parents generally obtain lower test scores and grades, yet, given this, are more ambitious in their educational choices and aspirations (Heath, Rothon, and Kilpi Citation2008). Hence, they may be less likely to exhibit school misconduct when they attend a low track. However, according to the ‘oppositional culture hypothesis’, anti-school attitudes and behaviours are especially pronounced among ethnic minorities (Ogbu Citation1987; Van Tubergen and van Gaans Citation2016), arguably even more among those in lower tracks.

I examine the ‘differentiation-polarization’ hypothesis among immigrant and native youths in three different educational systems: England, the Netherlands, and Sweden. So far, there are no cross-national comparative studies on the level and development of students’ school misconduct across track-levels. Comparative research is needed to shed light on whether and which type(s) of educational tracking relate(s) to school misconduct (c.f. Müller and Hofmann Citation2016). Primarily, I argue that the type of tracking in an educational system influences the extent to which students in lower tracks will experience status loss in the academic realm (Chmielewski, Dumont, and Trautwein Citation2013; Richer Citation1976), and subsequently come to oppose to school – i.e. reject the context that is held responsible for their status loss (Van Houtte Citation2006). Although, in theory, tracking is more rigid in full-curriculum tracking systems, students are confronted more with their track-level in course-by-course tracking systems (Chmielewski, Dumont, and Trautwein Citation2013).

I use two-wave panel data, which enable me to account for students’ prior levels of school misconduct. Most existing research on the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis still relies on cross-sectional data, making it impossible to truly test the hypothesis (i.e. that track differences in school misconduct polarise over time). Moreover, students’ track-level may be correlated to their misbehaviour because misbehaving students are generally assigned to lower tracks.

Theory

Tracking and school misconduct

There are various reasons why students in lower tracks misbehave more in school. First, the relationship may be (partly) driven by selection effects. With a few exceptions (Timmermans, Boer, and Werf Citation2016)Footnote1, research shows that students’ pro-school behaviour (e.g. following a teacher’s directions, effort) is positively related to a teacher’s track recommendation (Sneyers, Vanhoof, and Mahieu Citation2018) and expectations (Kelly and Carbonaro Citation2012), whilst accounting for their socioeconomic status and (teachers’ perception of their) academic performance. Since teachers are largely responsible for students’ track placement, this suggests that students who exhibit higher levels of school misconduct may be selected into lower tracks.

Second, the relationship between tracking and school misconduct may be confounded, primarily by a student’s academic ability or performance (e.g. test scores). Less able or lower performing students are selected into lower tracks, and according to the frustration-self-esteem model, these students will exhibit more problem behaviour (Finn Citation1989). Academic incompetence can lead to feelings of frustration, embarrassment, and a loss of status. Students may cope with these experiences by dismissing the context that is held accountable for these experiences.

Finally, tracking may influence school misconduct. According to the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis, tracking polarises students’ attitudes and behaviours (Hargreaves Citation1967; Van Houtte Citation2006, Citation2017). Tracking systems are hierarchical, and a students’ track-level constitute a signal about their academic capabilities in reference to other students (Chmielewski, Dumont, and Trautwein Citation2013). Students who are assigned to a low track experience status deprivation in the academic realm, while students who are assigned to a high track experience status gains (Hargreaves Citation1967; Van Houtte Citation2006, Citation2017). The experiences of status losses or gains may be reinforced by peers, teachers, and parents, who are also aware of the tracking hierarchy. Belgian research for example shows that students in lower tracks are more likely to think that others look down on them because of the studies they follow (Spruyt, Van Droogenbroeck, and Kavadias Citation2015).

According to the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis, students in low tracks will cope with their loss of status by engaging in school misconduct, while students in the high tracks conform to school norms and rules (Hargreaves Citation1967). Moreover, students who are assigned to a lower track may lower their educational expectations and aspirations, which reduces their incentive to invest in schoolwork (Gamoran and Berends Citation1987).

The track differences in school attitudes and behaviours are expected to polarise over time through two self-reinforcing mechanisms. First, students mainly interact, and establish friendships, with peers in the same track (Berends Citation1995). Hence, students are more likely to be positively influenced by these same-track peers. Second, teachers generally have lower expectations of students in lower tracks, and may label them as more problematic. This could lead to self-fulfilling prophecies, as students may act upon these expectations and labels (Müller and Hofmann Citation2016).

In support of the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis, panel research in Belgium suggests that students in the vocational track experience a greater decline in their sense of control over academic failures and successes than students in the academic track in their first year of secondary school (Van Houtte Citation2016). Relatedly, Swiss students in the basic track decrease their level of school adjustment more in the first year in which they are tracked, than students in the general or advanced track (Müller and Hofmann Citation2016). However, student performance or ability was not accounted for in this study, and tracking effects could therefore be confounded. In the United States, an early panel study found no support for the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis (Wiatrowski et al. Citation1982), yet later findings show that students in a non-academic track in tenth grade are less engaged in school, more likely to be absent, less likely to expect to go to college, and show more disciplinary problems in twelfth grade than students in the academic track (Berends Citation1995).

H1) Students in higher tracks exhibit lower levels of school misconduct, even when accounting for their academic ability level and prior level of school misconduct.

Variations by migration background

The relationship between students’ track-level and their school misconduct may vary by students’ migration background. The literature on the ‘aspiration-achievement’ paradox provides theoretical underpinnings for this.

The ‘aspiration-achievement’ paradox refers to the finding that the academic performance (i.e. test scores and grades) of children of immigrants is generally lower than that of children of the native majority population, yet – given this academic performance – their educational aspirations and choices are more ambitious (Heath, Rothon, and Kilpi Citation2008). Educational aspirations can either refer to idealistic aspirations that reflect students’ educational wishes, or realistic aspirations that reflect students’ perception of their educational opportunities given their constraints.

Scholars have posited various explanations for the relatively high educational aspirations and choices of children of immigrants. First, immigrant parents and their children may lack information about the host country’s educational system, leading to unrealistic expectations (Salikutluk Citation2016). Second, immigrant parents may socialise their children with high educational motivation and ambitions, as their migration may have been (partly) motivated by a desire or expectation to experience upward (intergenerational) mobility (Kao and Tienda Citation1995; Salikutluk Citation2016). Third, immigrant children may forestall discrimination in the labour market, and try to circumvent this by obtaining higher educational qualifications (Jackson, Jonsson, and Rudolphi Citation2012; Salikutluk Citation2016).

The ‘aspiration-achievement’ paradox has been observed in several European studies, and seems especially pronounced for children of non-Western migrants. For example, in Sweden and England ethnic minorities – primarily those of non-European and non-Western origins – are more likely to opt for the academic track after finishing compulsory school, and to transition to university upon finishing the academic track (Jackson, Jonsson, and Rudolphi Citation2012; Jonsson and Rudolphi Citation2010). Dutch students of Turkish, Moroccan, and Surinamese/Antillean origin also choose for more ambitious tracks than their native majority peers, given their academic ability (Van de Werfhorst and Van Tubergen Citation2007). When accounting for student performance and parental background, Western migrants do not attend higher tracks in the Netherlands. In Germany, youths with a Turkish background have higher idealistic and realistic educational aspirations than their native counterparts, yet the idealistic and realistic educational aspirations of students originating from the Former Soviet Union (Hadjar and Scharf Citation2019; Salikutluk Citation2016), Poland, Former Yugoslavia, or Italy/Greece are similar to those of natives (Hadjar and Scharf Citation2019). Moreover, Swedish students with a Turkish, Near Eastern, or Former Yugoslavian background; Dutch students with a Turkish background; and English students of Nigerian, Indian, Pakistani, or Bangladeshi background show higher idealistic and realistic educational aspirations than native students (Hadjar and Scharf Citation2019).

The high educational ambitions among children of immigrants, as well as their motivation to pursue education to avoid discrimination, could make them less likely to reject school when they attend a low track. Educational tracks carry meaning and value that are assumed to affect students’ educational expectations (Gamoran and Berends Citation1987). In the high tracks, all students will have high expectations that motivate them to adhere to school rules. In the low tracks, low expectations may be present among students with a native background, but less so among students with a migration background. This latter group is more motivated to stay in school and move to a higher track (c.f. Dollmann Citation2017; Jackson, Jonsson, and Rudolphi Citation2012), and/or is less aware about the implications of low-track placement due to a lack of knowledge about the educational system. Moreover peer effects may strengthen these group differences, as students tend to interact with same-ethnic peers (Geven, Kalmijn, and van Tubergen Citation2016).

H2a) The negative relationship between a student’s track-level and school misconduct is more pronounced for students with a native majority background than for students with a (non-Western) migration background.

Mickelson’s (Citation1990) work on educational attitudes sheds a different light on the aspirational-achievement paradox. Her research among African-Americans in the United States suggests that there are two types of educational attitudes. While African-American students perceive education as a pathway to upward mobility in society at large (i.e. they hold positive abstract educational attitudes), they are relatively pessimistic about the payoffs of schooling within their own lives (i.e. they hold negative concrete educational attitudes). Mickelson posits that only the concrete attitudes, and not the abstract ones, predict the academic behaviour of African-American students. Building on these ideas, the relatively high educational aspirations among ethnic or racial minorities may not translate into pro-school behaviour, as these high educational aspirations may reflect abstract, rather than concrete educational attitudes (Kao and Tienda Citation1998).

Mickelson’s conceptualisation of concrete attitudes builds on Ogbu’s (Citation1987) work on school rejection among migrants who came to the United States involuntarily, for example as slaves (e.g. African Americans). Ogbu (Citation1987) argues that their experiences of discrimination and racism causes them to conclude that their efforts in school are not necessarily rewarded in the labour market. This leads to an ‘oppositional culture’ with respect to schoolwork.

Some scholars argue that the situation of students with a non-Western migration background in Western-Europe is comparable to that of involuntary migrants in the United States (D’hondt et al. Citation2016; Jonsson and Rudolphi Citation2010; Van Tubergen and van Gaans Citation2016). While non-Western immigrants in Western-Europe migrated voluntarily, they also face social exclusion and discrimination. Hence, they may hold positive abstract educational attitudes (and high aspirations), but negative concrete ones (D’hondt et al. Citation2016) that translate into school rejection (Van Tubergen and van Gaans Citation2016).

Empirical findings in the European contexts provide little support for these ideas (e.g. the Netherlands (Van Tubergen and van Gaans Citation2016); Belgium (Demanet and Van Houtte Citation2011; D’hondt et al. Citation2016); Germany (Stark, Leszczensky, and Pink Citation2017)). For example, Dutch students with a non-Western migration background do not clearly have more negative concrete educational attitudes or oppose more to school than students of the native majority (Van Tubergen and van Gaans Citation2016). While Belgian students of Turkish and Moroccan descent do hold more negative concrete educational attitudes than students of the native majority, these attitudes are not related to their achievement (D’hondt et al. Citation2016). Moreover, qualitative findings suggest that experiences and expectations of discrimination sometimes also motivates students to invest in school.

Despite these findings, an oppositional culture could be present among (non-Western) migrants in the low ability tracks, as low track assignment may be perceived as discrimination. Hence, these students may be more likely to feel that their opportunities in society are thwarted than their native counterparts, especially if they also anticipate labour market discrimination. Moreover, given that students with a migration background generally have higher educational aspirations than their native counterparts, they may assign greater value to track hierarchies, and will therefore experience a greater loss of status in the lower tracks. I formulate the following (contrasting) hypothesis:

H2b) The negative relationship between a student’s track-level and school misconduct is more pronounced for students with a (non-Western) migration background than for students with a native majority background.

Variations across educational systems

The relationship between educational tracking and school misconduct, as well as the differences herein between native and immigrant youths, may vary across educational systems. Educational systems are characterised by different types of tracking. Some systems, such as the Dutch one, have a full-curriculum tracking system in which students are placed into different groups for all subjects on the basis of their academic ability (Chmielewski Citation2014). Other systems, such as the Sweden and English one, apply course-by-course tracking. In England, this tracking is more extensive than in Sweden (Geven, Jonsson, and van Tubergen Citation2017).

In theory, course-by-course tracking is less rigid than full-curriculum tracking: students can attend different tracks for different courses, upward track mobility is easier, and the link between track attendance and postsecondary education is weaker (Chmielewski Citation2014). While, in practice, these assumptions do not always hold, students in course-by-course tracking systems may experience their track-level as less definitive than students in full-curriculum tracking systems. These arguments imply that, in course-by-course tracking systems, the self-esteem of students in lower tracks will be higher, and their frustration with school will be lower, than in full-curriculum tracking systems.

However, students in course-by-course tracking systems are also more exposed to students who attend a different track. Consequently, there is a higher chance that they use each other as a reference group for comparison, and that they are confronted with the status of their track (Chmielewski, Dumont, and Trautwein Citation2013; Richer Citation1976). Hence, the polarisation of attitudes and behaviours between students of different tracks will be more pronounced in course-by-course tracking systems than in full-curriculum tracking ones.

Empirical findings seem to correspond with this second line of reasoning. Cross-national research indicates that students who attend a higher track have a higher math self-concept in course-by-course tracking systems, and a lower math self-concept in full-curriculum tracking systems (Chmielewski, Dumont, and Trautwein Citation2013). Moreover, in Flanders in Belgium (a full-curriculum tracking system), students in lower tracks have a lower global self-esteem (Van Houtte, Demanet, and Stevens Citation2012), and are less involved in their studies (Van Houtte and Stevens Citation2009), especially when they are surrounded by higher-track students in school.

H3) The negative relationship between a student’s track-level and school misconduct is more pronounced in England and Sweden than in the Netherlands.

H4) The difference between students with a native majority background and students with a migration background with respect to the relationship between track- level and school misconduct is more pronounced in England and Sweden than in the Netherlands.

Data and measurements

Data

I use data from the Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries (CILS4EU) (Kalter et al. Citation2013). Nationally-comparative data were gathered in England, Germany, The Netherlands, and Sweden. Germany is excluded from the analyses, because in most German Federal states students in the lowest track complete their programme after the first wave, and therefore often leave school (i.e. 25% of the German schools did not participate in the second wave primarily for this reason). Hence, information on school misconduct in the second wave was missing for a selective group of students.

The first wave of data was collected among 4000–5000 students in ± 100 schools in each country, in the school year of 2010/2011. Large schools and schools with a high immigrant proportion were oversampled. When invited schools refused to participate, replacement schools were approached in England and the Netherlands. Response rates at the school-level were 15% in England, 35% in the Netherlands, and 77% in Sweden before replacement; and 66% in England and 92% in the Netherlands after replacement. In each country, the 15-year-old school population was approached (i.e. year-10 students in England, 3rd graders in the Netherlands, and 8th graders in Sweden). All students in two randomly selected classes were invited to participate. Participation rates at the student-level varied between 81% in England and 91% in the Netherlands.

One year later, 86% of the English, 98% of the Dutch, and 99% of Swedish schools participated in the second wave. In this wave, between 65 (England) and 78% (Sweden) of all the sampled students participated. I exclude 57 Dutch, 7 Swedish, and 275 English students who participated in the second wave, but not via school (i.e. they dropped out of school, changed school, or their school refused to participate). Moreover, I exclude students with missing values on the dependent variable (i.e. school misconduct in wave 2), as imputing these values can lead to random error in the estimates (Young and Johnson Citation2015). Missing values on the dependent variable are primarily due to student non-participation in the second wave (i.e. item non-response is < 1% in England and Sweden, and 3% in the Netherlands).

Measurements

Dependent variable

School misconduct w2

School misconduct is measured by the average score on four items from the student questionnaire in the second wave. Students were asked to indicate the extent to which they skip class, come late to class, argue with their teachers, and are punished in school. Students provided their answers on a five-point-scale ranging from ‘never’ to ‘every day’. In each country the items load on one factor, and Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.69.

Independent variables

Track

Track-level is measured by a categorical variable with four categories: (1) high (=reference category), (2) intermediate, (3) low, and (4) no track.Footnote2 In the Netherlands, all students are tracked. Students who attend the most selective six-year university-preparatory track (i.e. VWO or Gymnasium) are considered to be in the high track. The intermediate track refers to students who follow a five-year programme that grants access to tertiary vocational education (i.e. HAVO). Students who attend one of the four-year prevocational tracks (i.e. VMBO-b, VMBO-k, VMBO-g, or VMBO-t) that prepare for senior secondary vocational education (i.e. MBO) are in the low track. In the Netherlands, tracks are measured at the school-level in the first wave. More than 98% of the students stay in this track in the second wave.

For Sweden and England, track-level refers to a student’s ability group in mathematics in the first wave. In course-by-course tracking system, tracking occurs most frequently in mathematics (Chmielewski, Dumont, and Trautwein Citation2013). This is also apparent in the CILS4EU data, as tracking is more common for mathematics than for language in both countries. Moreover, students’ track-level in mathematics may affect track assignment in other subjects, and advanced mathematics placement is strongly related to college attendance and completion (Chmielewski, Dumont, and Trautwein Citation2013, 934).

Swedish students were asked about their level of learning in mathematics. Answer categories include: ‘the highest group’ (i.e. high track), ‘the middle group’ (i.e. intermediate track), ‘the lowest group’ (i.e. low track), ‘no group’, and ‘don’t know’. I combine the ‘don’t know’ and the ‘no group’, as, theoretically, the level of school misconduct of students who do not know their track is not expected to differ from that of students who are not tracked.Footnote3

In England, there are eleven answer categories for students’ mathematics set: the highest ability (1) to the fifth highest ability group (5), the fifth lowest (6) to the lowest ability group (10), and no set (11). The number and types of sets vary across schools. For example, in some schools all sets are represented, whereas in others there is only a distinction between the highest (1), the second highest (2), and the lowest track (10). English students are considered to be in the high track when they attend the highest track (1). Students in the intermediate track are students in the second highest to the fifth highest sets. Students in the low track are students who attend the fifth lowest to the lowest sets.

Track attendance is relatively stable in England and Sweden: 75% of the English students stay in the same track for mathematics across the two waves, and 66% of the Swedish students.

Immigrant background

A categorical variable indicates whether students have a native, non-Western, or Western migration background. When both parents are born in the survey country, students are considered to have a native background (i.e. 84% of the Dutch, 73% of the Swedish, and 74% of the English sample, see ). When at least one parent is born in a (non-)Western country, the student is considered to have a (non-)Western migration background. When parents are born in different countries outside of the survey country, I rely on the maternal country of birth.

Students with one migrant parent and one native-born parent are considered to have a migration background. These students may be socialised with relatively high educational aspirations and motivations, and possibly try to circumvent discrimination in the labour market.Footnote4

I do not distinguish between first and second generation immigrants, as the sample sizes are too small to distinguish between these groups in different educational tracks in each country. For example, there are only 8 Western and 19 non-Western first-generation migrants in the highest track in the Netherlands.

For the same reason I cannot distinguish by country of origin, yet it should be noted that countries of origin differ across the destination countries. English students with a migration background primarily originate from India (n = 148), Jamaica (n = 57), or Pakistan (n = 263); Dutch students with a migration background from Turkey (n = 173), Morocco (n = 164), or Suriname (n = 106); and Swedish students with a migration background from Iraq (n = 153), Bosnia and Herzegovina (n = 99), or Turkey (n = 97).

Controls

I control for school misconduct in the first wave by using the average score on the same items as school misconduct in the second wave. In each country the items load on one factor and Cronbach’s alpha ≥ 0.70.

I control for a student’s cognitive performance, as students with higher performance levels attend higher tracks, and may exhibit lower levels of school misconduct. Cognitive performance is measured by a student’s score on a cognitive test of 27 items in the first wave (CILS4EU Citation2016). In all countries Cronbach’s alpha is ≥0.78. I standardise the test scores in each country.

I control for gender, as boys exhibit higher levels of school misconduct (Geven, Jonsson, and van Tubergen Citation2017), and may be assigned to lower tracks than girls (e.g. Timmermans, Boer, and Werf Citation2016).

A dummy variable indicates whether the respondent’s parents are divorced in the first wave. Children of divorced parents engage in higher levels of problem behaviour, and their academic achievement is lower (Amato Citation2000).

Parental occupational status is measured by the occupational status (ISEI 08) of the biological parent with the highest occupational status. In a separate questionnaire, parents provided their own and their partner’s occupation. When the occupational status of both biological parents is missing, I rely on information that is provided by the child. The correlation between the occupational status that is based on the child’s information and the one that is based on parental information varies between 0.70 and 0.76 for mothers, and 0.72 and 0.77 for fathers. I include a categorical variable that indicates the number of books in the home. Answer categories are on a five-point-scale, ranging from 0 to 25 books to over 500 books. Parental occupational status and number of books are both indicative of a parent’s socioeconomic status and/or cultural capital. This may be related to track placement as well as school misconduct.

I include a student’s age, as the extent to which students repeat a grade may differ across countries, and grade repetition is associated with school misconduct (Demanet and Van Houtte Citation2013).

I control for the share of wave 1 classmates in the wave 2 class. Especially in the Netherlands, students change class between the waves. Students’ level of school misconduct may be more constant when they are exposed to the same classmates in both waves.

At the class-level, I control for the share of students with a non-Western background, as these students tend to be clustered in lower tracks, and the ethnic composition of the school may be related to school misconduct (Geven, Kalmijn, and van Tubergen Citation2016).

and provide descriptive information for the total sample, by country, and by migration background.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, total sample and by country.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics, by migration background.

Analytical plan

First, I performed descriptive analyses to examine the level of school misconduct in the first and second wave for students with a native, Western, and non-Western background. Subsequently I pooled the data of all countriesFootnote5, and estimated multilevel models with students nested in first wave classes, nested in schools. In all models, except for the first, I accounted for selection effects by controlling for a student’s level of school misconduct in the first wave. This lagged-dependent variable approach was also applied by previous panel studies on this topic (Berends Citation1995; Müller and Hofmann Citation2016; Van Houtte Citation2016), and is especially appropriate when the lagged dependent variable predicts the main independent variable, or the lagged dependent variable directly affects the dependent variable (Allison Citation1990). The former is true, as prior school misconduct has been found to affect track placement. Moreover, the latter may be true: to avoid severe punishments. students may at some point stop exhibiting more school misconduct (Geven, Jonsson, and van Tubergen Citation2017).

The lagged-dependent variable approach does not account for unobserved differences between individuals that determine their track-level and (changes in) their school misconduct. Hence, as a robustness check, I examined how within-individual changes in track-level are related to within-individual changes in school misconduct in Sweden. These analyses accounted for unobserved time-invariant differences across students, yet did not preclude that changes in behaviour led to changes in track attendance. These analyses could not be performed for the other countries, as Dutch students hardly changed their track-level over time, and sample sizes in England were too small (i.e. only 175 non-Western migrants and 64 Western migrants changed their track-level; and when considering specific track changes, these numbers were even smaller).

Missing values on the independent variables were imputed by multiple imputation with chained equations. I imputed missing values for each country separately using 30 imputed datasets. The imputation models included all the predictor variables and indicators of school misconduct in both waves. As described before, and suggested in the literature (Young and Johnson Citation2015), cases with missing values on the dependent variable were deleted. In all analyses, I weighed for the non-response and sampling design at the school-level. In the tables and figures unstandardised estimates are shown. To give an indication about the effect sizes, y-standardised coefficients for the effects that are of main interest are provided.

Results

Descriptive results

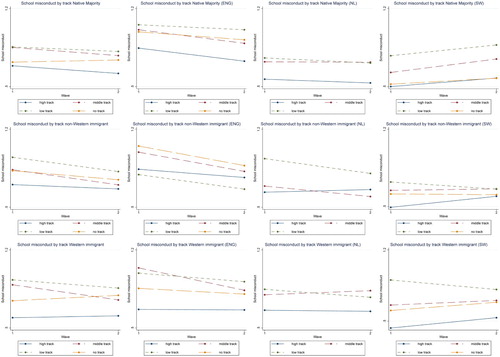

shows the average level of school misconduct in the first and the second wave for students with a migration background and students with a native majority background. When considering the data for all countries, the level of school misconduct among the native majority population is lower in the academic track than in the vocational or intermediate tracks (p < 0.01). These track differences hardly change over time. Nevertheless, students of the native majority in the high and intermediate track decrease their school misconduct slightly (about 0.03 points or 0.05 of a standard deviation), but statistically significantly, more than their peers in the low track (p < 0.01). This pattern is also visible when considering English native majority students. Dutch students of the native majority who attend the high track also decrease their school misconduct somewhat more than students in the intermediate track (p = 0.023). In Sweden, students from the native majority increase their school misconduct over time, and there are no statistically significant track differences in the level of change.

Figure 1. Average level of school misconduct in different educational tracks in wave 1 and wave 2 for students from the native majority (upper row), students with a non-Western immigrant background (middle row), and students with a Western immigrant background (bottom row); presented together for all countries (left column), and separately for each country. The figures for student school misconduct in all countries (left column) account for differences in the level of school misconduct across the countries, as the level of school misconduct, as well as the distribution of students across tracks, varies across countries. All numbers are adjusted for the sampling design and non-response at the school-level.

Among students with a migration background, the pattern is different. In the first wave, students with a (non-)Western migration background in the high track exhibit lower levels of school misconduct than students in the low and intermediate track (p < 0.01). However, these differences become smaller over time, as students in the intermediate and vocational tracks decrease their school misconduct more than students in the high track (p < 0.01). In sum, these descriptive results indicate that there is no negative relationship between a student’s track-level and school misconduct for all student groups (hypothesis H1). Instead, and in line with hypothesis H2a, this relationship seems to be more pronounced for students from the native majority.

Multilevel analyses

presents the findings of the multilevel models. In model 1, track differences in school misconduct are examined without accounting for a student’s prior level of misconduct and cognitive test score. Students who attend the intermediate, low, or no track exhibit higher levels of school misconduct than students in the high track. Compared to students in the high track, the level of school misconduct among students in the low track is 0.19, or 0.30 of a standard deviation (0.19/0.64), higher. Boys and students with divorced parents engage in higher levels of school misconduct. School misconduct is more prevalent in England than in the Netherlands or Sweden.

Table 3. Multi-level analyses on school misconduct w2 of students in England, the Netherlands, and Sweden.

In model 2, I account for the level of school misconduct in the first wave. The differences in school misconduct between students in the high track and those in the intermediate or low tracks remain statistically significant, but are greatly reduced. Compared to students in the high track, students in the low track exhibit 0.05, or 8% of a standard deviation, more school misconduct.

In model 3, cognitive test scores are included. Students who score higher on the cognitive test, exhibit lower levels of school misconduct, accounting for prior levels of school misconduct. In this model, the track differences in school misconduct turn to statistical insignificance. In contrast to hypothesis H1, I do not find that students in lower tracks exhibit higher level of school misconduct, when accounting for prior levels of school misconduct and cognitive ability.

Model 4 includes interactions between students’ track-level and their migration background. In this model, the main effects of attending the intermediate or the low track (as compared to the high track) are positive and statistically significant. Students with a native majority background who attend an intermediate or low track exhibit, respectively, 0.05 and 0.06 – or 0.08 and 0.09 of a standard deviation – more school misconduct than students in the high track. Although these effects are small, effect sizes are generally small in models that account for prior levels of the dependent variable. Hence, I find some support for H1 among students of the native majority. There is no statistically significant difference between native students in the high track and those who do not attend a track. Moreover, Wald tests indicate that there are no statistically significant differences between native students in the low, intermediate, or no track.

In support of hypothesis H2a, and in contrast to hypothesis H2b, I find statistically significant negative interaction effects between attending the intermediate track and being from a non-Western (b = −0.13) or Western immigrant background (b = −0.10). The interactions between having a (non-)Western migrant background and attending a low track are also negative, but not statistically significant. Nevertheless, the effect sizes of these negative interactions are larger than the positive main effect of low track attendance. Students with a migration background who attend the low track do not exhibit higher levels of school misconduct than their peers in the high track.

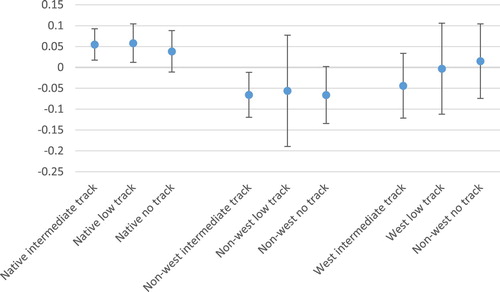

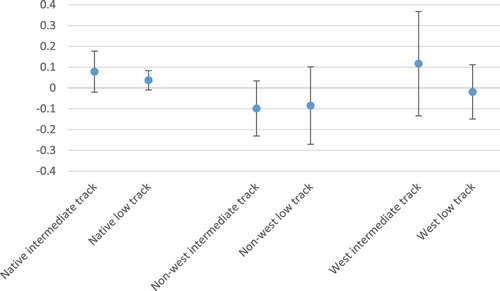

To shed more light on the interaction effects between track-level and migration background, I calculate the Average Marginal Effects (AMEs) of attending the intermediate, low, or no track, as compared to attending the high track, for students with a native, Western, and non-Western background. graphically depicts these AMEs. The figure indicates that among students with a non-Western immigrant background, there is a negative effect of attending an intermediate track (as compared to a high track) on school misconduct (b = −0.07, or −0.11 of a standard deviation in school misconduct). The effect of attending a low track as compared to a high track is also negative for students with a non-Western immigrant background (b = −0.06), but not statistically significant. However, the standard errors of this low-track effect are relatively large, indicating a high level of uncertainty in this estimate. There is no statistically significant effect of attending the low or no track (as compared to the high track) on school misconduct for students with a Western migration background.

Figure 2. Average Marginal Effects with 90%-CI of attending the intermediate, low, or no track as compared to the highest track for students with a native, non-Western, or Western immigrant background (calculations based on Model 4, ; effects sizes are not standardised).

In model 5, I examine cross-national differences in the effects of tracking for students with different migration backgrounds. The model includes a three-way interaction between educational track, immigrant background, and country; and two-way interactions between (1) immigrant background and country, and (2) educational track and country (England is the reference category). None of the country interaction effects in model 5 are statistically significant. Moreover, additional Wald tests indicate that there are no statistically significant differences between the Netherlands and Sweden with respect to the coefficients for tracking, migrant background, and the interaction between tracking and migrant background. Hence, I find no support for H3 and H4.

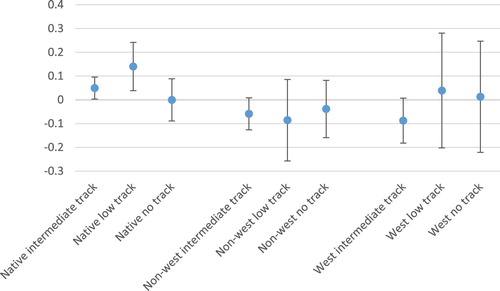

The sizes of the country interaction effects do suggest that the observed patterns may not reach statistical significance in all countries. To shed more light on this, I use the estimates of model 5 to calculate the AMEs of attending the intermediate, low, or no track for students with a native majority, Western immigrant, and non-Western immigrant background in each country (–). English students with a native background exhibit higher level of school misconduct when they attend the intermediate track (b = 0.05), the low track (b = 0.14), or no track (b = 0.09), than when they attend the high track (). Wald test indicate that there are no statistically significant differences between English students of the native majority who attend no, a low, or an intermediate track.

Figure 3. Average Marginal Effects with 90%-CI of attending the intermediate, low, or no track as compared to the highest track for students with a native, non-Western, or Western immigrant background in England (calculations based on Model 5, ; effects sizes are not standardised).

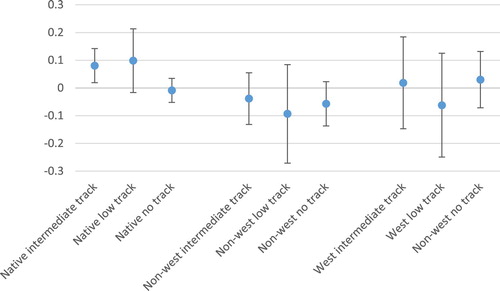

Figure 4. Average Marginal Effects with 90%-CI of attending the intermediate, low, or no track as compared to the highest track for students with a native, non-Western, or Western immigrant background in Sweden (calculations based on Model 5, ; effects sizes are not standardised).

Figure 5. Average Marginal Effects with 90%-CI of attending the intermediate, low, or no track as compared to the highest track for students with a native, non-Western, or Western immigrant background in the Netherlands (calculations based on Model 5, ; effects sizes are not standardised).

There are statistically significant differences in the effect of attending the intermediate track and the low track between students with a native background and students with a non-Western migrant background in England. For students with a non-Western background there is no positive effect of attending a low, intermediate, or no track (as compared to a high track) on school misconduct. For them, the point-estimates of attending the low, intermediate, or no track are all negative, but not statistically significant.

In Sweden, native students in the intermediate and low tracks exhibit higher levels of school misconduct than those in the high track (). The level of school misconduct of native students who are not tracked does not differ from that of native students in the high track (b = −0.01), yet seems to be lower than that of native students in the intermediate (difference is 0.09, p (two-sided) = 0.014) or low track (difference is 0.11, p (two-sided) = 0.150). Among Swedish students with a migration background, there is no statistically significant effect of attending the low, intermediate, or no track as compared to the high track ().

In the Netherlands, we find no statistically significant tracking effects for any of the groups (). However, the point estimates of attending a low or intermediate track tend to be positive for students from the native majority, and negative for students with a non-Western migration background.

Sensitivity Analysis

For Sweden I examine how changes in students’ track-level are related to changes in their school misconduct (Appendix Table A3). I use hybrid models to estimate both between-individual and within-individual effects of tracking (Allison Citation2009). The estimates of the within-individual effects are equal to the estimates that would be obtained in a student fixed effect model.

Contrary to the previously discussed findings, a change from no-track to the intermediate track is not related to an increase in school misconduct among native majority students in Sweden. However, a change from no-track to the low track is related to 0.24 of a standard deviation increase in school misconduct for these students. Moreover, the interaction effect between changing to a low track and having a non-Western migration background is negative, of substantial size, and borderline significant. More specifically, the within-individual effect of changing from no track to the low track is 0.5 of a standard deviation smaller for students with a non-Western migration background, implying that such a track change is not related to changes in their school misconduct. Generally, changes in track-level are not negatively related to changes in school misconduct among students with a migration background. Hence, in line with the other findings, the analyses on track changes in Sweden provide some support for H1 among native majority students, partial support for H2a, and no support for H2b.

Conclusion

For decades, scholars have argued that tracking leads to a polarisation of student attitudes and behaviours (Hargreaves Citation1967): students in the low tracks would come to oppose to school, whereas students in the high track would become more favourable towards school. This ‘differentiation-polarization’ hypothesis has been criticised, as student behaviours greatly vary across students in the same track (Gamoran and Berends Citation1987). Nevertheless, researchers have rarely examined variations in the relationship between track-level and school misconduct by student background. Moreover, few studies have relied on panel data, and no study has examined multiple tracking contexts at a time. The present study contributed to previous work by examining track differences in school misconduct over the course of a year by migration background in three educational systems that differ in their type of tracking (England, The Netherlands, and Sweden).

In contrast to previous panel findings (Berends Citation1995; Müller and Hofmann Citation2016), I found no overall support for the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis. However, I controlled for confounders that previous studies have not (always) controlled for, including student test scores and parental divorce. Possibly, students in lower tracks do not reject school because of their track-level, but because of their lower school performance, or the problems that they face in their out-of-school lives (e.g. parental divorce).

As expected, I found differences in the applicability of the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis by migration background, and most consistently between students from the native majority and students with a non-Western background. I found small positive effects of attending a lower track on school misconduct for students from the native majority, and no effects for students with a (non-Western) migration background. These findings could be interpreted in light of the ‘achievement-aspiration paradox’. The educational aspirations and choices of students from immigrant backgrounds are relatively ambitious (Dollmann Citation2017). Hence, when they attend a low track they may not come to oppose to school, but remain motivated. In line with the present findings, qualitative research in Belgium indicated that positive educational aspirations and attitudes among students with a Turkish or North-African background were not confined to students in the high tracks (D’hondt et al. Citation2016). D’hondt et al. (Citation2016) showed that racism and discrimination did not necessarily lead to school opposition, but that it even motivated some students in school, as they tried to counteract negative stereotypes and protect themselves against discrimination. Future research should examine the long-term consequences of low track placement among students with a migration background. It is possible that their frustration develops later in life.

The findings provided no support for an ‘oppositional culture’ among students with a non-Western migration background in the low track, yet some results were indicative of an oppositional culture in the high track. I found a negative effect of attending the intermediate track (rather than the high track) on school misconduct among students with a non-Western migration background. Moreover, students with a non-Western background in the high track engaged in higher levels of school misconduct than native majority students in the high track. Possibly, they experience that, although they perform well in school, their chances in society compare negatively to those of native students with equal educational credentials (c.f. De Vroome, Martinovic, and Verkuyten Citation2014). Prior research also showed that immigrants with higher educational levels more frequently turn away from the host society (De Vroome, Martinovic, and Verkuyten Citation2014), yet a recent study did not find this among adolescents (van Maaren and van de Rijt Citation2018).

I found no statistically significant cross-national differences in the relationship between tracking and school misconduct. While this may imply that the relationship does not vary by an educational system’s tracking type, the current findings do not allow definite conclusions. Perhaps, the influence of the educational system’s tracking type is overshadowed by other national-level factors (e.g. educational system or labour market). To tear out the influence of tracking type, future research should include more educational settings, or investigate how changes in tracking policies are related to changes in the effect of a student’s track-level.

A limitation of the present study is that only two waves of data could be analysed, and few students changed their track-level over time. While it is an empirical fact that tracking is rigid, future research could try to examine the relationship between changes in track-level and student behaviour with multi-wave data. This may allow researcher to estimate the trajectories of students’ school misconduct with latent growth models that can account for measurement error in school misconduct. Nevertheless, the current study advanced upon most previous work which tends to be cross-sectional.

Similar to previous panel studies on this topic, the students in this study were tracked before the data collection started. Hence, behavioural responses to tracking may have occurred before students were observed. This may especially apply to Dutch students, as they were assigned to a specific track two years before the start of the study, and hardly experienced changes in their track-level. Nevertheless, and extending previous studies on this topic, a ‘control group’ of students who did not attend a track was included for Sweden and England (c.f. Müller and Hofmann Citation2016). Consequently, the development of school behaviour among ‘tracked’ students could be compared to students who reported to attend no specific track.

This study relied on student self-reports of school misconduct and track-level, that may suffer from social desirability biases. Since I studied behavioural changes, social desirability biases in students’ school misconduct will merely be problematic if these biases change over time. Student reports of their track-level could also be inaccurate, because students may not know their track-level. However, according to the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis students are affected by a track-label. If students are unaware of their track, it should not impact their behaviour. In line with this, school misconduct of Swedish students who did not know their track did not differ from those who did not attend a track.

This study sheds more light on the extent to which the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis is tenable. The hypothesis was tested separately for immigrant and native youths with two-wave panel data in three different educational contexts. By showing that the application of the differentiation-polarisation hypothesis is restricted to native majority students, I provided an important contribution to the literature, especially in the light of the growing immigrant population in Western-Europe. Policies that aim to keep students in low tracks committed to school may have to draw special attention to the native majority population.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (46.4 KB)Acknowledgements

I like to thank the anonymous reviewers, the editor, Herman van de Werfhorst, Andrea Forster, Lotte Scheeren, Anatolia Batruch, Jesper Rözer, and Katrijn Delaruelle for helpful comments and suggestions. I presented earlier versions of this paper at the ‘European Consortium for Sociological Research’ (ECSR) conference at Sciences Po in Paris in 2018 and the ‘Educational Inequality – Mechanisms and Institutions’ conference at the University of Amsterdam in 2018. I am grateful to the audience at these conferences for their helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This study finds that students receive higher track recommendations when primary school teachers evaluate their work habits more positively and their social behaviour more negatively. However, students’ work habits and social behaviour are analysed in the same model and are positively correlated.

2 I also estimated a model in which the low and intermediate track are combined (Appendix A2.2; Figure A1). Conclusions remain unaltered.

3 Additional analyses show that, empirically, there are no differences between students who do not know their track and who are not tracked (Appendix A1.1).

4 As a robustness check, I excluded these students from the analyses (Appendix A1.3, Table A2). The patterns do not become stronger; if anything, they become slightly weaker.

5 I also analysed the data separately for each country (Appendix A1.1, Table A1).

References

- Allison, Paul D. 1990. “Change Scores as Dependent Variables in Regression Analysis.” Sociological Methodology 20: 93–114.

- Allison, Paul D. 2009. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Vol. 160. Los Angeles: SAGE publications.

- Amato, Paul R. 2000. “The Consequences of Divorce for Adults and Children.” Journal of Marriage and Family 62 (4): 1269–1287.

- Berends, Mark. 1995. “Educational Stratification and Students’ Social Bonding to School.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 16 (3): 327–351.

- Chmielewski, Anna K. 2014. “An International Comparison of Achievement Inequality in Within-and Between-School Tracking Systems.” American Journal of Education 120 (3): 293–324.

- Chmielewski, Anna K., Hanna Dumont, and Ulrich Trautwein. 2013. “Tracking Effects Depend on Tracking Type An International Comparison of Students’ Mathematics Self-Concept.” American Educational Research Journal 50 (5): 925–957.

- CILS4EU. 2016. Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries. Technical Report. Wave 1 – 2010/2011, v1.2.0. Mannheim: Mannheim University.

- de Brabander, Cornelis J. 2000. “Knowledge Definition, Subject, and Educational Track Level: Perceptions of Secondary School Teachers.” American Educational Research Journal 37 (4): 1027–1058.

- Demanet, Jannick, and Mieke Van Houtte. 2011. “Social-Ethnic School Composition and School Misconduct: Does Sense of Futility Clarify the Picture?” Sociological Spectrum 31 (2): 224–256.

- Demanet, Jannick, and Mieke Van Houtte. 2013. “Grade Retention and Its Association with School Misconduct in Adolescence: A Multilevel Approach.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 24 (4): 417–434.

- De Vroome, Thomas, Borja Martinovic, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2014. “The Integration Paradox: Level of Education and Immigrants’ Attitudes Towards Natives and the Host Society.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 20 (2): 166–175.

- D’hondt, Fanny, Lore Van, Mieke Praag, Peter A. J. Van Houtte, and Peter A. J. Stevens. 2016. “The Attitude–Achievement Paradox in Belgium: An Examination of School Attitudes of Ethnic Minority Students.” Acta Sociologica 59 (3): 215–231.

- Dollmann, Jörg. 2017. “Positive Choices for All? SES-and Gender-Specific Premia of Immigrants at Educational Transitions.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 49: 20–31.

- Finn, Jeremy D. 1989. “Withdrawing from School.” Review of Educational Research 59 (2): 117–142.

- Gamoran, Adam, and Mark Berends. 1987. “The Effects of Stratification in Secondary Schools: Synthesis of Survey and Ethnographic Research.” Review of Educational Research 57 (4): 415–435.

- Geven, Sara, Jan O. Jonsson, and Frank van Tubergen. 2017. “Gender Differences in Resistance to Schooling: The Role of Dynamic Peer-Influence and Selection Processes.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46 (12): 2421–2445.

- Geven, Sara, Matthijs Kalmijn, and Frank van Tubergen. 2016. “The Ethnic Composition of Schools and Students’ Problem Behaviour in Four European Countries: The Role of Friends.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (9): 1473–1495.

- Hadjar, Andreas, and Jan Scharf. 2019. “The Value of Education among Immigrants and Non-Immigrants and How This Translates Into Educational Aspirations: A Comparison of Four European Countries.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (5): 711–734.

- Hargreaves, David H. 1967. Social Relations in a Secondary School. London, England: Routledge.

- Heath, Anthony F., Catherine Rothon, and Elina Kilpi. 2008. “The Second Generation in Western Europe: Education, Unemployment, and Occupational Attainment.” Annual Review of Sociology 34: 211–235.

- Jackson, Michelle, Jan O. Jonsson, and Frida Rudolphi. 2012. “Ethnic Inequality in Choice-Driven Education Systems: A Longitudinal Study of Performance and Choice in England and Sweden.” Sociology of Education 85 (2): 158–178.

- Jenkins, Patricia H. 1997. “School Delinquency and the School Social Bond.” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 34 (3): 337–367.

- Jonsson, Jan O., and Frida Rudolphi. 2010. “Weak Performance—Strong Determination: School Achievement and Educational Choice among Children of Immigrants in Sweden.” European Sociological Review 27 (4): 487–508.

- Kalter, Frank, Anthony F. Heath, Miles Hewstone, Janne O. Jonsson, Mathijs Kalmijn, Irena Kogan, and Frank Van Tubergen. 2013. Children of Immigrants Longitudinal Survey in Four European Countries (Cils4EU). GESIS Data Archive, Cologne. ZA5353 Data file Version 3.3.0.

- Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 1995. “Optimism and Achievement: The Educational Performance of Immigrant Youth.” Social Science Quarterly 76 (1): 1–19.

- Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 1998. “Educational Aspirations of Minority Youth.” American Journal of Education 106 (3): 349–384.

- Kelly, Sean, and William Carbonaro. 2012. “Curriculum Tracking and Teacher Expectations: Evidence from Discrepant Course Taking Models.” Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal 15 (3): 271–294.

- Mickelson, Roslyn Arlin. 1990. “The Attitude-Achievement Paradox among Black Adolescents.” Sociology of Education 63 (1): 44–61.

- Müller, Christoph Michael, and Verena Hofmann. 2016. “Does Being Assigned to a Low School Track Negatively Affect Psychological Adjustment? A Longitudinal Study in the First Year of Secondary School.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 27 (2): 95–115.

- Ogbu, John U. 1987. “Variability in Minority School Performance: A Problem in Search of an Explanation.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly 18 (4): 312–334.

- Richer, Stephen. 1976. “Reference-Group Theory and Ability Grouping: A Convergence of Sociological Theory and Educational Research.” Sociology of Education 49 (1): 65–71.

- Rumberger, Russell W. 1995. “Dropping out of Middle School: A Multilevel Analysis of Students and Schools.” American Educational Research Journal 32 (3): 583–625.

- Salikutluk, Zerrin. 2016. “Why Do Immigrant Students Aim High? Explaining the Aspiration–Achievement Paradox of Immigrants in Germany.” European Sociological Review 32 (5): 581–592.

- Sneyers, Elien, Jan Vanhoof, and Paul Mahieu. 2018. “Primary Teachers’ Perceptions That Impact upon Track Recommendations Regarding Pupils’ Enrolment in Secondary Education: A Path Analysis.” Social Psychology of Education 21 (5): 1153–1173.

- Spruyt, Bram, Filip Van Droogenbroeck, and Dimokritos Kavadias. 2015. “Educational Tracking and Sense of Futility: A Matter of Stigma Consciousness?” Oxford Review of Education 41 (6): 747–765.

- Stark, Tobias H., Lars Leszczensky, and Sebastian Pink. 2017. “Are There Differences in Ethnic Majority and Minority Adolescents’ Friendships Preferences and Social Influence with Regard to Their Academic Achievement?” Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft 20 (3): 475–498.

- Timmermans, Anneke C., Hester Boer, and Margaretha P. C. Werf. 2016. “An Investigation of the Relationship between Teachers’ Expectations and Teachers’ Perceptions of Student Attributes.” Social Psychology of Education 19 (2): 217–240.

- Van de Werfhorst, Herman G., and Jonathan J. B. Mijs. 2010. “Achievement Inequality and the Institutional Structure of Educational Systems: A Comparative Perspective.” Annual Review of Sociology 36 (1): 407–428.

- Van de Werfhorst, Herman G., and Frank Van Tubergen. 2007. “Ethnicity, Schooling, and Merit in the Netherlands.” Ethnicities 7 (3): 416–444.

- Van Houtte, Mieke. 2006. “School Type and Academic Culture: Evidence for the Differentiation–Polarization Theory.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 38 (3): 273–292.

- Van Houtte, Mieke. 2016. “Lower-Track Students’ Sense of Academic Futility: Selection or Effect?” Journal of Sociology 52 (4): 874–889.

- Van Houtte, Mieke. 2017. “Gender Differences in Context: The Impact of Track Position on Study Involvement in Flemish Secondary Education.” Sociology of Education 90 (4): 275–295.

- Van Houtte, Mieke, Jannick Demanet, and Peter A. J. Stevens. 2012. “Self-Esteem of Academic and Vocational Students: Does Within-School Tracking Sharpen the Difference?” Acta Sociologica 55 (1): 73–89.

- Van Houtte, Mieke, and Peter A. J. Stevens. 2009. “Study Involvement of Academic and Vocational Students: Does between-School Tracking Sharpen the Difference?” American Educational Research Journal 46 (4): 943–973.

- van Maaren, Floor M., and Arnout van de Rijt. 2018. “No Integration Paradox among Adolescents.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Advance online publication.

- Van Tubergen, Frank, and Milou van Gaans. 2016. “Is There an Oppositional Culture among Immigrant Adolescents in the Netherlands?” Youth & Society 48 (2): 202–219.

- Wiatrowski, Michael D., Stephen Hansell, Charles R. Massey, and David L. Wilson. 1982. “Curriculum Tracking and Delinquency.” American Sociological Review 47 (1): 151–160.

- Young, Rebekah, and David R. Johnson. 2015. “Handling Missing Values in Longitudinal Panel Data with Multiple Imputation.” Journal of Marriage and Family 77 (1): 277–294.