ABSTRACT

In the name of women’s protection, Dutch immigration authorities police cross-border marriages differentiating between acceptable and non-acceptable forms of marriage (e.g. ‘forced’, ‘sham’, ‘arranged’). The categorisation of marriages between ‘sham’ and ‘genuine’ derives from the assumption that interest and love are and should be unconnected. Nevertheless, love and interest are closely entwined and their consideration as separate is not only misleading but affects the exchanges that take place within marriage and, therefore, has particular implications for spouses, especially for women. The ethnographic analysis of marriages between unauthorised African male migrants and (non-Dutch) EU female citizens, often suspected by immigration authorities of being ‘sham’, demonstrate the complex articulation of love and interest and the consequences of neglecting this entanglement – both for the spouses and scholars. The cases show that romantic love is not a panacea for unequal gender relations and may place women in a disadvantaged position – all the more so because the norms of love are gendered and construe self-sacrifice as more fundamental in women’s manifestations of love than that of men’s.

Introduction

In June 2009, Tim, a Nigerian migrant in Amsterdam and friend of mine, urgently asked me to meet his cousin Kevin. He was not clear about the reasons but he said Kevin became interested in talking to me when Tim told him that I was Greek and, at that time, I was working as a housekeeper in a Dutch hotel. The three of us arranged to meet in a central location in Amsterdam. I was the first to arrive. With some delay, Tim and Kevin came together. Kevin was in his early thirties, tall, a little bit fat, very talkative and loud – the very opposite of Tim, who was short, slim and had a voice you could hardly hear. Tim introduced his cousin Kevin as his ‘brother’ and for the rest of the conversation they addressed each other as brothers. Kevin also addressed me as ‘brother Apostolos’ and started explaining the reasons he wanted to meet me. He said that his temporary visa would expire soon. For this reason, he asked me to help him find a woman who would want to, if not marry him, have a cohabitation contractFootnote1 with him. This would enable him to extend his legal stay in the Netherlands. He emphasised that he was particularly interested in a European, but not Dutch, woman and asked me to search among my Eastern European hotel colleagues and my Greek network. In that way, he could benefit from the generous family migration rights conferred to spouses of EU citizens (Tryfonidou Citation2009; see also Wray, Kofman, and Simiç Citation2021). Kevin was in rush because if he did not find a woman within a month, he would have to face further bureaucratic complications.

‘I will make your pocket smile, my brother’, Kevin told me. Although he did not mention anything about him paying the woman, I assumed that he would be prepared to offer something to her as well. As Kevin was explaining his situation to me, I had no doubt that he was looking for a ‘marriage of convenience’ – a marriage that had nothing to do with love, just a means for him to get a residence permit – even though he never described it as such. Before Kevin and I finished our conversation, I asked him, quite hesitantly, if his search for a European partner was limited only to women and I explained that a same-sex marriage or partnership in the Netherlands could grant him the same rights as a marriage/partnership to a woman. Dutch immigration authorities tend to investigate more carefully heterosexual cross-border marriages in which the ‘sponsor’ is the female spouse. Often assuming that these women are naïve and in need of protection, immigration officers enquiry the motives of migrant men to marry them (De Hart Citation2003, 126–127). If Kevin was interested in a ‘marriage of convenience’, I thought, a same-sex marriage might be a better option because immigration authorities would less likely suspect it as ‘sham’ (on benevolent sexual culturalism: Chauvin et al., Citation2021). He said that he knew that and without a second thought rejected this option. Without calling me ‘brother’ again, he said, ‘Mister Apostolos, I’m talking to you seriously!’ From the conversation we had, it was clear that Kevin wanted a relationship with a European woman, intending to secure a long-term residence permit. Was that solely his purpose? If he was interested in just a ‘marriage of convenience’ which would allow him to extend his legal stay in the Netherlands, why did he reject from the beginning other possibilities such as a same-sex partnership/marriage which would help him to obtain a residence permit following the same legal route? Perhaps Kevin would feel uncomfortable pretending that he was in a romantic relation with another man in front of immigration authorities. Was that uneasiness the only reason for his reluctance to obtain a residence permit via this channel? Was he also looking for an emotional connection with a European woman? But if that was so, would that be a ‘marriage of convenience’ as I originally thought?

This encounter also raised questions about my understanding of Kevin’s search for a partner. Why did I immediately assume that a marriage that would provide access to migrant legality for Kevin had nothing to do with emotions and particularly love? Why did I understand Kevin’s motivation only as an instrumental action? Reflecting about this event, I realised that I shared the same assumption with the state authorities. The state’s distinction between ‘sham’ and ‘genuine’ marriages derives from the assumption that interest and emotions are separate domains of social life that are not and should not be in contact. Indeed, migration authorities establish the authenticity of a marriage by assessing the existence of emotions, in particular, ‘love’, and the absence of other ‘ulterior motives’ (Eggebø Citation2013; De Hart Citation2017; D’Aoust Citation2013). Often, scholars and migrant support organisations have unwillingly reproduced the assumption behind the categorisation of marriages as either ‘sham’ or ‘genuine’, including those who are critical of the exclusionary effects of such categorisations. They do so, for example, when they criticise how the fight against the ‘marriages of convenience’ has exclusionary consequences for ‘real’ couples and ‘loving’ partners.

This ethnographic study focuses on the marriages of unauthorised Ghanaian and Nigerian migrant men with (non-Dutch) EU citizen women in the Netherlands which are usually suspected by immigration authorities as ‘sham’ because they provide a relatively easy access to migrant legality. Without ignoring the importance of what spouses materially gain in these marriages, it challenges the categorisation of cross-border marriages as either ‘sham’ or ‘genuine’, showing a complex relation between emotions and interest. However, the aim is not simply to show the entwinement of emotions and interest and the falseness of that distinction – this has already been well-established by other scholars studying intimate relations (for instance, Zelizer Citation2005; Medick and Sabean Citation1984; Constable Citation2003). Instead, the article examines the implications of such dichotomy, between interest and love, for the exchanges that take place in the context of marriage and as a result, the effects on the relationship between two spouses. Contrary to immigration authorities which police cross-border marriages in the name of women’s protection, the case studies in this article show that the state-imposed romantic love ideal may undermine the bargaining power of women in marriage. Migration researchers risk neglecting these implications when they rely on the state categorisation of cross-border marriages as either ‘sham’ or ‘genuine’.

Data and methods

The empirical material analysed in this article originates from ethnographic fieldwork I carried out in the context of my previous research on kinship relations and the survival strategies of West African migrants (Ghana, Nigeria) in the Netherlands and Greece (Andrikopoulos Citation2017). The fieldwork also included interviews both with West African migrants, mostly male, and their spouses of various origins. Although the actual fieldwork in the Netherlands lasted fourteen months, I have been in contact with some of my research participants for a much longer period either because I knew some of them from previous research projects or because we maintain our good contacts up until the present. All of my research participants have been aware of the purpose of the research project and some of them have read previous versions of this text. To protect the anonymity of my research participants I have altered their names and some minor details. I have kept the titles and the way I addressed them (e.g. ‘Mrs’, ‘friend’) because it reflects my relationship with them at the time of my fieldwork. As is evident in the opening story, the ethnographic description includes also my own reaction to the events I describe. I do that on purpose in order to make apparent to the reader how my own assumptions have been challenged while I was in the field and why thinking through state categories led me to conclusions that are different from social reality (see also Piot Citation2015).

The state of emotions: romantic love and the ‘marriage of convenience’

In the Netherlands, as in other European countries, the regulation of cross-border marriages became a key concern for the national politics of belonging. As explained by Moret, Andrikopoulos, and Dahinden (Citation2021), state authorities closely inspect cross-border marriages for two main reasons. First, cross-border marriages enable a significant number of ‘uninvited’ foreigners to enter the national territory as ‘family migrants’. Second, state authorities fear that cross-border marriages may threaten the cultural reproduction of the nation and its social regeneration. By regulating cross-border marriages, and marriage more generally, the state attempts to define and produce the society it envisions.

In that effort, state authorities differentiate between, on the one hand, acceptable marriages that will result into ‘good families’ and, on the other hand, non-acceptable marriages that the state tries to prevent from taking place. The introduction of more restrictive policies for cross-border marriages have been justified by the Dutch government as measures to protect women and ensure gender equality (Rijksoverheid Citation2009; Bonjour and De Hart Citation2013). All categories of unacceptable and undesirable marriages (‘sham marriage’, ‘forced marriage’, ‘arranged marriage’), framed by the state as bad for women, have a common opposite: the love-based marriage. The romantic love ideal has become the means for state authorities to control the gender dynamics in cross-border marriages and prevent undesirable outcomes – both for women and society in general.

The Dutch state construes ‘sham’ marriages as those marriages contracted with the ‘sole purpose’ of enabling the migrant spouse to obtain a residence permit and often involve the monetary compensation of the citizen spouse (IND, Citationn.d.). A ‘genuine’ marriage is understood as the opposite: a relationship based on and sustained by love.Footnote2 The state categorisation between ‘genuine’/love-based and ‘sham’/interest-based marriages is informed by a modernist ideal of romantic relations which Giddens has described as a ‘pure relation’. According to Giddens (Citation1992), a pure relationship is a relation of equality and mutuality between two autonomous individuals. It is a relationship of emotional fulfilment in which what one offers to the other is not motivated by the expectation of something else in return. The ideal of marriage as a pure relationship is arguably the norm according to which cross-border marriages are assessed by the state (Wray Citation2015; Eggebø Citation2013).

The marriage of love and interest

State’s conception of love as a disinterested emotion is dominant across Europe precisely because it stems from a Christian ideal of love opposed to instrumentality. Nevertheless, such conception of love is not universal and may differ from daily practices. It is important, therefore, for migration researchers and other scholars, to ‘approach love as an analytic problem rather than a universal category’ (Thomas and Cole Citation2009, 3) and treat carefully the state’s conception of love. Problematising love implies that we pay close attention not only to what love means in particular settings but also how love is expressed and demonstrated.

Ethnographic studies (Rebhun Citation1999; Cornwall Citation2002; Hunter Citation2010; Constable Citation2003) have documented how local conceptions of love encompass material interest and how interest may strengthen affection and desire instead of erasing them. In rural Madagascar, for example, the local concept of love, fitiavina, refers both to affective qualities and acts of material support and care. Rural Malagasy express their love by sharing their resources and spending on their beloved ones (e.g. sharing food, buying clothes, paying school or medical fees). ‘In male-female relationships, a man makes fitiavina through gifts to the woman, and the woman returns the favor of fitiavina by offering her sexual and domestic services, and labor’ (Cole Citation2009, 117). But the teaching of Christian missionaries, during the period of colonialism, insisted on the separation of love and money and promoted a meaning of love that is selfish-less and interest-less. To some extent, this contributed to the emergence of a new understanding of love, as ‘clean fitiavina’, which, at least normatively, is unrelated to material exchanges (Cole Citation2009). Similar transformations in the meaning of love have been observed elsewhere and usually are attributed to the spread of Christianity, emergence of capitalism and the influence of a globalised western notion of romantic love (Hirsch and Wardlow Citation2006; Padilla et al. Citation2007). This does not mean that love has indeed became disengaged from material exchanges but rather that a new norm emerged that projects emotions and interest as ‘hostile worlds’ (Zelizer Citation2005). Even in societies of Europe and the U.S. where romantic love discourse originates, love continues to be deeply entwined with material interest but in less explicit ways (Zelizer Citation2005; Illouz Citation2007).

Although the state’s ideal of love-based marriage considers love as separate from material exchange, the assessment of the authenticity of cross-border marriages values positively certain transactions. For example, immigration authorities regard marriage payments (bridewealth, dowry) as proofs of the authenticity of a marital relationFootnote3 (Satzewich Citation2014; Pellander Citation2015). On the contrary, other forms of payment are considered suspicious and hint at ‘marriage of convenience’. The European Commission’s Handbook on Marriages of Convenience alerts national immigration authorities:

In comparison with genuine couples, abusers are more likely to hand over an ‘unexplained’ sum of money or gifts in order for the marriage to be contracted ( … ) that could be considered as ‘payment for abuse’ to the EU spouse and facilitators. (Citation2014, s.4.4)

It is clear, therefore, that material transactions are allowed depending on how they are framed. The labelling of a material transfer as ‘dowry’ or as a ‘payment for abuse’ is of utmost importance because it determines the content of the relation between two parties as either ‘spouses’ or as ‘economic partners’ and consequently the state’s assessment of this relation as either ‘genuine marriage’ or as ‘marriage of convenience’.

But there are also contradictions to the ideal of disinterested love in the regulation of cross-border marriages (see also Pellander, Citation2021). One of them is the framing of the citizen spouse as a ‘sponsor’ who has to meet certain income criteria in order to apply for family reunification with the foreign spouse. According to IND’s website, a sponsor ‘is a person, employer or organisation that has an interest in the arrival of the foreign national in the Netherlands’ (emphasis added). If the labelling of a material transfer (e.g. as ‘dowry’) determines the content of the relationship between the giver and receiver (as ‘spouses’ and their families), why does the labelling of the two partners (‘sponsor’ and ‘sponsored’) not determine the type of transfers between them (e.g. payment)? Quite ironically, West African migrants in the Netherlands use the word ‘sponsor’ to refer to persons who fund the migration projects of aspiring migrants and then expect these migrants to repay them, usually with money they earn in sex work. Dutch authorities prosecute these ‘sponsors’ as ‘human traffickers’.

Who fears love? Gender inequality and romantic love

‘A marriage of convenience is not as innocent as it may seem. Sometimes they claim victims, as they may involve people smuggling or human trafficking. This is why the government is taking preventive measures’ declares IND (Citationn.d.) on its webpage. The fight against ‘sham marriages’ and the policing of other non-acceptable marriages (e.g. ‘forced’, ‘arranged’, ‘polygamous’) in the Netherlands and many European countries have been presented as measures to protect women (Block, Citation2021; Leutloff-Grandits, Citation2021; Muller Myrdahl Citation2010; Carver Citation2016). Marriages with Dutch women are more likely to be suspected by immigration authorities as ‘sham’ than marriages with Dutch men (De Hart Citation2003; Kulu-Glasgow, Smit, and Jennissen Citation2017). To ensure that migrant men do not take advantage of ‘vulnerable’ women, immigration officers inspect the marriage motives and assess as ‘genuine’ those marriages that are motivated by love. As Giddens (Citation1992) associates the ‘pure relationship’ with the ‘democratisation of private life’, immigration authorities and, often, migration scholars take for granted that the ideal of love marriage, the common opposite to all non-acceptable forms of marriage, protects the position of women and contributes to the establishment of gender equality.

Studies on the historical transformation of marriage, from a relationship pragmatically arranged to a relationship that is based on romantic love, show that love does not automatically entail gender equality (Collier Citation1997; Rebhun Citation1999). The transformation of the meaning of love towards a new normative definition that excludes interest and exchange did not liberate women and often resulted in them losing resources and thus becoming more dependent on their men. For this reason, women did not always welcome this development and insisted on a notion of love that encompasses exchange. On the other hand, men often appealed to the notion of romantic love and complained that they have been financially used by women who did not really love them (for African examples: Cornwall Citation2002; Cole Citation2009; Smith Citation2009).

To understand the complex dynamic of love in gender relations, it is important to consider the gendered aspects of the norms of love. There is no doubt that both men and women fall in love. But they are expected to express and demonstrate love differently. These culturally constructed differences are not only a matter of bodily expressions (kissing, display of affection, etc.). When love is demonstrated as care for the other, it often implies altruism, self-sacrifice and suffering. Arguably, such manifestations of care are more central in norms of how women ought to express and demonstrate their love – with the exemplary case of maternal love which to some degree informs women’s love to other family members (Paxson Citation2007; Collier Citation1997). If love has different implications for men and women, the presence of it in a heterosexual marriage cannot by itself improve the position of women.

Affective circuits and the marital economy of exchange

Considering all of the above, this article takes critical distance from state’s categorisation of cross-border marriages as either ‘sham’ or ‘genuine’ and instead examines the forms of exchange that take place in marriage, how these are framed by those participating in these exchanges, and how state’s categories and ideals of acceptable marriage impact the circulation of resources as well as the power dynamics between spouses. I study these exchanges through the lens of ‘affective circuits’ which refer to ‘the social formations that emerge from the sending, withholding, and receiving of goods, ideas, people and emotions’ (Cole and Groes Citation2016, 6). The lens of affective circuits directs our attention to the circulation of resources – both material and emotive – and how these affect the social relations of the network(s) actors. The concept of affective circuits, as theorised by Cole and Groes (Citation2016), is attentive to the power dynamics between those who participate in exchanges as well as to the role of the state in regulating the flow of resources within the circuits.

The cross-border marriage literature predominantly focuses on couples and the relation between the spouses. Methodological conjugalism, ‘the tendency to focus on marriage, couples, and dyads within the largely Eurocentric framework of the nation-state’ (Groes Citation2016, 193), is informed by the modernist ideal of marriage as a pure relation and the state’s category of acceptable marriage. Nevertheless, marriage and the exchanges that take place within marriage are embedded in a larger affective circuit, extending beyond national borders, in which resources circulate in various directions and among more than two persons. The following case sheds light on these processes.

Circulating resources

In one of my visits to Christina (Greek) and John (Nigerian) in December of 2010, I mentioned the failed attempt of a migrant colleague at the fast-food restaurant where I worked to get papers through marriage to a Surinamese woman in exchange for €15,000. When I finished the story, John said, ‘Fifteen thousand is too much’. ‘He didn’t have an alternative’, I said. ‘Why doesn’t he go to Poland to marry one, or to Slovakia? There it will cost 4,000 to 6,000. I have many friends who did it!’

I asked John to elaborate. He said that my colleague should go to Poland, book a room in a hotel, and go out clubbing. He should flirt with women, pay for their drinks and talk to them nicely. If a woman responded, he could explain his situation and ask her for help. He could offer her around €4000. He should propose to the Polish woman, bring her to Amsterdam and offer her free accommodation and help in finding a job. ‘And if he can find her a job, then she might do it without money!’ John laughed. Although Eastern and Southern Europeans have the right, as EU citizens, to move freely to the Netherlands and any other EU member-state, migration remains a costly and financially risky decision. African migrant men can assist women from Europe’s periphery to migrate to Western Europe by providing them accommodation and access to their wide networks that will help them find a job and start a new life.

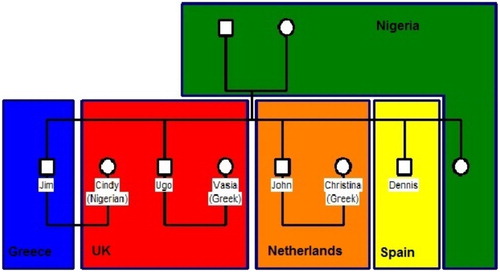

John was not the only person of his family in Europe (). He had one brother in Greece, Jim, a second brother in Spain, Dennis, and another one in the U.K., Ugo. John and his brother Ugo in the U.K. had residence permits on the basis of marriage to an EU citizen (both Greeks) and were the two brothers who managed to regularly send money to Nigeria in support of their parents as well as their younger sister who was taking care of their parents. Dennis, his brother in Spain, was unauthorised and Jim, his brother in Greece, had been legalised in an amnesty programme but was in a dire economic condition.

When I visited Greece in Easter of 2011, I met John’s brother, Jim, and we went together to his Pentecostal church. Jim was the oldest brother, in his early forties. He was married to a Nigerian woman who was living in the U.K. After the service, Jim introduced me to Camelia, a young woman in her late twenties from Romania, whom he presented as his ‘sister’. We left the church and went to Jim’s apartment where we spent the rest of our day. From what they told me, Camelia and Jim met on the Internet and after they had been chatting for a long time Camelia decided to come and meet Jim in person.

Later in the evening, Camelia told me that she was looking for a job, preferably in Western Europe. Jim asked me if I could help her find a job in the Netherlands. I explained to her that Romanian citizens needed a work permit in the Netherlands due to the transitory period requirements after Romania joined the EU. She was already aware of that but she seemed very interested in finding ways to overcome this legal barrier. For the time being, Camelia asked Jim to help her find a summer job on a Greek island. Greece did not apply the same restrictions to Romanians as did the Netherlands, so she could enjoy her rights of free movement and settlement in Greece as a full European citizen.

A few months later, when I returned to the Netherlands, I learned from Christina that Dennis, the brother of Jim and John who lived in Spain, had moved to Amsterdam. To my great surprise, Dennis had married Camelia, who had also moved to Amsterdam. ‘Well, it’s for papers’, Christina commented as she was giving me the news. In Amsterdam, Camelia stayed together with Dennis and hoped that he and his brother John would manage to find a decent job for her. To her disappointment, however, the legal barriers due to her Romanian citizenship did not allow her to work. In the meanwhile, Camelia got pregnant by Dennis. So their relationship was not only on paper and at least involved sexual relations. Dennis and John, unable to find a job for her in the Netherlands, mobilised their transnational networks. Their brother Ugo, who lived in the U.K. with his Greek wife, offered to help Camelia. Ugo worked as a supervisor in a cleaning company and made the necessary arrangements to hire Camelia as a cleaner on an undeclared basis. Camelia accepted the job offer and started working there. However, she was very disappointed with this job and threatened to divorce Dennis. As I learned from John and Christina, Camelia accused Dennis of not finding her a good job while his brother John had found a good office job for his Greek wife. Camelia regretted having left Romania and asked Dennis to relocate with her to her hometown. Dennis considered this possibility because his legal status was tied to Camelia. John and other friends strongly advised Dennis not to go to Romania. Nevertheless, Camelia insisted that she wanted to give birth there so her mother could help her. Dennis was left with no choice other than to follow Camelia to Romania where, after quite a long period, he managed to get a Romanian residence permit. A few years later, Dennis, Camelia and their child moved to the U.K. where they live together until today.

Although Camelia held the scarce civic resources required for Dennis’s legalisation, she relied on her husband and his connections for fulfilling her own migration aspirations in Western Europe. The marriage of Dennis to Camelia enabled him to get legalised and, as his other two brothers married also to EU citizens, to start sending money to Nigeria for his parents and the younger sister who was taking care of them.

The marriage of Camelia and Dennis was a relationship of mutual care, an exchange, in which both spouses contributed to each other. The multiple forms of exchange taking place in this marriage created a reciprocal dependency between the spouses. In this context, the wishes and preferences of Camelia, a migrant herself, were taken seriously by Dennis. Would Dennis show the same commitment to satisfy Camelia if his own personal gains were not at risk and if Camelia’s assistance for his legalisation was only motivated by (romantic) love? The answer to this question can only be hypothetical. But the next case is about a couple in which the woman’s assistance to her husband is driven by ‘pure’ love. How does the ideal of marriage as a pure relation impact the flow of resources between spouses and how these transfers are understood by them? What are the consequences of the separation of love and interest for the position of the female spouse in marriage?

I’ll marry you for free because I love you

Kyriaki, a Greek woman, met Frank, a Nigerian man, in a dance club of Thessaloniki, Greece. They started dating and quickly became a couple. Frank told Kyriaki that he had a problem with his papers and had to find a way to get a residence permit. He mentioned marriage as one of the possible ways to get papers. Kyriaki did not feel ready to marry him but at the same time she was afraid to lose him. After serious consideration, she decided to do it.

Kyriaki’s friends advised her to reconsider and warned her that Frank was with her only for the sake of his papers. Kyriaki felt confused by Frank’s motivations and thus confronted him with the following proposal as she recounted it to me:

I said to him before we marry: ‘Frank, if you want to marry me just for your papers, because I know how it is, I promise you that I will marry you and we will do your papers under an agreement: If there is love between us, we continue with our lives. But if there is no love and you marry me just for your interest, ( … ) we keep the marriage, each of us continues his and her life and in exchange I want you to help me with the fees of my vocational school’. How much was it that time? Was it €2,000? So, each of us would give €1000. This is what I asked him in exchange. And he insisted, ‘No, I love you!’

Frank and Kyriaki went to a lawyer to give them legal advice regarding their marriage and Frank’s legalisation. Kyriaki remembered:

The first question the lawyer asked me, as a Greek woman, was: ‘So, why do you marry him? For money? Does he pay you or it’s because of love?’ And I replied, ‘Love and only love’ … Because she (i.e. lawyer) wanted to know how to speak to us. She wanted to know if it’s a professional agreement so in case something goes wrong between us how we deal with it. And if it was because of love, how much would you do for this love?

Kyriaki dropped out of her vocational school, which she anyways could not afford, and travelled with Frank to Nigeria. It was her first trip by plane and the first time she used her passport. She stayed there for about a month to arrange all documents and marry Frank. The visa application was successful and Frank travelled to Greece as Kyriaki’s husband. That year Kyriaki got pregnant and gave birth to their child. A few months later, the whole family moved together to the Netherlands where Frank had friends who could help him find a well-paid job. As a husband of an EU citizen, Frank enjoyed the same mobility rights within the EU as Kyriaki. It was a difficult decision for Kyriaki to leave Greece and relocate to another country but now she had to consider not only her own well-being but also the promising future in the Netherlands for her husband and child.

Frank’s love for his wife and child has been important as well. As Frank writes in the diary he shared with Kyriaki: ‘I will love my family and take care of them because (it) is the only thing that I have (…) I believe that one love can keep us together’. But contrary to Kyriaki, who said to me that she had been ready to give without anticipating anything in return, Frank understood love more in reciprocal terms. ‘All I have is for my family and all they have is for me’, he writes in the diary.

In The Economy of Love and Fear, Boulding (Citation1973) distinguishes two types of transfers: the one-way transfer and the exchange. One-way transfers, he explains, are motivated either by love or by fear. By definition, thus, Boulding relies on the same Eurocentric ideal of love as a selfish-less emotion that excludes exchange. When one-way transfers, or what he considers ‘sacrifices’, are motivated by love, they contribute to the establishment of strong social bonds, not comparable to those established by exchange relations.

… without the kind of commitment or identity which emerges from sacrifice, it may well be that no communities, not even the family, would really stay together. Exchange has no power to create community, identity, and commitment, perhaps because it involves so little sacrifice. (Boulding Citation1973, 28)

Had I approached this case using the state lens of ‘sham’/ ‘genuine’ marriage, I would have been concerned only with the question of love’s authenticity, as Kyriaki originally was. This concern would have blurred a more fundamental issue: the consequences of romantic love and why these have been different for the wife and the husband in this marriage. The next section analyses the case of a woman, an Italian citizen of Ghanaian descent, who realises the unequal implications of romantic love and tries to deal with love’s consequences in marriage.

Resisting romantic love

Christy was born in Ghana, grew up in Italy and moved to the Netherlands as a teenager when her mother divorced her Italian husband. I first met her in 2010 in Amsterdam, through a common friend, and she immediately gained my admiration for her strong personality, social character and intelligence. Three years later, in 2012, she told me that she was planning to marry a legally unauthorised Ghanaian migrant and earn about €15,000 from this marriage. Kwame, the man who proposed to marry her, was a junior pastor in her church and also her ex-boyfriend. They had been in a relationship but Kwame chose to marry another woman in Ghana. Christy felt hurt and used to comment with bitterness and humour that Kwame left her ‘for a woman with a moustache’. The marriage of Kwame in Ghana lasted four years and, according to Christy, Kwame did it only to satisfy his parents who wanted him to marry that woman. As long as Kwame was married to a Ghanaian citizen in Ghana, marriage-based legalisation in the Netherlands was not an option for him. But after his divorce, marriage again became a possibility for his legalisation. In fact, there was only one-way Kwame could meet the criteria for his legalisation: if he could find a non-Dutch EU citizen spouse and benefit from the generous rights conferred to family members of EU citizens. As an Italian citizen living in the Netherlands, Christy was the ideal candidate. Kwame returned to her and asked her to help him get a residence permit by marrying him. Christy agreed. However, she said to him: ‘That time you had me for free. Now you have to pay’. Kwame accepted and asked Christy to propose a price. Christy told me that she took into consideration Kwame’s modest finances and instead of asking for the whole amount upfront she suggested that he pays €500 per month. They agreed and went to a lawyer to learn about the next steps. One of the first things Christy did was to inform her neighbours that she has reconnected with her ex-boyfriend. ‘If the police comes for a check, they may ask questions to my neighbours so it’s better that they know that we are in a relationship again’, Christy explained to me.

Mrs Veronica, the mother of Christy, was very delighted that her daughter would marry Kwame. At Christy’s birthday party, I noticed that Kwame addressed Mrs Veronica as ‘Mommy’. When I noted to Mrs Veronica my surprise that Kwame would even bow in greeting her, she replied that his respectful behaviour showed that ‘he wants to become a member of the family’. In one of my visits to Mrs Veronica together with Christy, Mrs Veronica narrated to me the story of her cousin in the U.K. who married an unauthorised migrant. According to what she said, the migrant woman who married her cousin, a naturalised British citizen, divorced him once she got her indefinite residence permit. ‘That’s why you always have to ask for money’, Mrs Veronica concluded, looking at Christy.

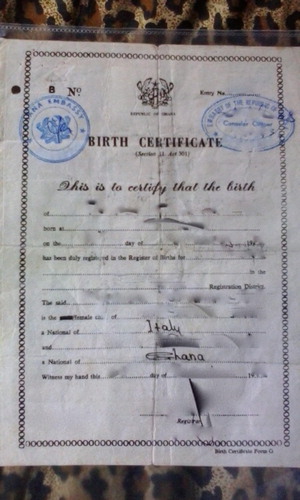

Mrs Veronica was aware of and approved her daughter’s decision to ask Kwame a compensation because, as she had said several times, marrying an unauthorised migrant entails risks not worth taking for free. Furthermore, Mrs Veronica claimed that she should receive part of Christy’s compensation from Kwame because Christy could only request a payment due to her Italian citizenship. She reminded Christy that she became an Italian citizen because Mrs Veronica brought her from Ghana to Italy, where she was living as a migrant at that time. Mrs Veronica’s expectation for compensation resembles bridewealth negotiations according to which parents may claim a higher amount when they have invested in their daughter and her future (e.g. by funding university education).Footnote5 ‘You owe your citizenship to me’, Mrs Veronica said to Christy. Christy exploded and answered back: ‘I don’t owe you anything. You owe your papers to me!’. Christy reminded her mother how she managed to get legalised in Italy. According to Christy, her mother had left her in Ghana with another woman so that she could migrate to Italy and make money from sex work. In Italy, Mrs Veronica married an Italian, who was one of her clients. Italian immigration authorities suspected that the marriage of a Ghanaian sex worker with an Italian citizen was ‘sham’ and so turned down Mrs Veronica’s legalisation request. Mrs Veronica and her husband went to Ghana and brought Christy back with them to Italy. With a fraudulent birth certificate (), they claimed Christy as their common legitimate child. Considering the child, Italian authorities validated the marriage and agreed to legalise Mrs Veronica. For this reason, Christy maintained that it was her mother who should be grateful to her and not the other way around. As we see, the direction of flow in affective circuits is subject to different interpretations, which are important because they determine who is obliged to whom.

Figure 2. The birth certificate of Christy which enabled her to acquire Italian citizenship and her mother to be legalised (photo by the author).

In the meanwhile, Kwame attempted to re-establish his love relationship with Christy. As Christy told me, Kwame became very flirty with her and tried to seduce her and have sex. Although Christy still felt attracted to him and, as she said to me, he could have been an ideal husband for her, she did not want to be in a love relation with him. Christy feared that a love relationship would result in her losing her monthly compensation because romantic love is not compatible with financial gains. For that reason, she insisted framing her marriage with Kwame as ‘business’ and not as ‘love’. Also, she could not forget that Kwame had betrayed her love when he left her to marry another woman. She resisted and did not give in to Kwame’s pressure to re-start a love relationship. After several attempts to reconnect, Kwame left Christy one more time, before they marry, accusing her of treating him ‘like a dog’.

This marriage, which immigration authorities would have labelled as ’sham’, failed because Christy resisted framing it as a love relationship. Despite Christy’s feelings for Kwame and Kwame’s feelings for her, Christy was conscious that the acknowledgement of their relation as ‘love’ would have consequences for her, some of them undesirable. This would not have been the case if the norm of love encompassed material exchange. But such a conception of love is incompatible both with state’s and Christian ideals of love and of marriage as a pure relation.

Six years later, after Christy read a draft of this article, she reformulated what was the dilemma for her:

What is the choice of a woman at the end of the day, after you tried everything and after you had so many bad experiences? Do you choose for love, you know pure love, or you choose to learn how to love?’

Conclusion

The politicisation of cross-border marriages in many European countries has impacted in fundamental ways the research agenda of migration studies and particularly how these marriages have been approached by migration scholars. The scholars’ use of the state categories, such as ‘sham’ and ‘genuine’ marriage, reproduce, often unwillingly, the same assumptions upon which state’s exclusionary practices and hierarchies are based (Moret et al., Citation2021). In this article, I did not approach cross-border marriages through the lens of ‘sham’ and ‘genuine’. This would have led in two opposite directions. The first would be to analyse these marriages as material exchanges and frame the feelings of spouses as ‘emotional labor’ (Hochschild Citation1983) or as ‘performances of love’ (Brennan Citation2004) or, second, as most usually happens, to emphasise love and neglecting the importance of material transfer. Instead, I showed that material transfers are embedded in a wider affective circuit in which material and emotive resources circulate – an embedding that is also found in non-migrant marriages whose authenticity is never officially questioned and scrutinised.Footnote6

The analysis of ethnographic material demonstrates how the state impacts the flow within the affective circuits in, at least, three ways: First, laws and policies enable, facilitate or deter who circulates within these circuits. Family reunification legislation, as well as other laws, affect cross-border marriage mobility – often in ways that is not predicted. Second, the state valorises some of the most important resources that circulate in the networks of affective circuits. The tension between Christy and Mrs Veronica is who owes citizenship to whom and is indicative of how valuable a resource citizenship is, precisely because exclusionary state policies made it scarce and not easily accessible (Andrikopoulos Citation2018). Cross-border marriage is highly valorised because it is one of the few remaining channels to citizenship and migrant legality. Third, the state imposes a certain morality on the transfers that take place in the affective circuits of cross-border marriages. The morality of love that lacks motives for material gains does not necessarily prevent the circulation of material resources between spouses and other actors of affective circuits. Nevertheless, the state-imposed and state-sanctioned morality of romantic love necessitate those who participate in affective circuits to frame material transfers as emotion-driven autonomous acts of giving. ‘You never wanted to admit that I married you mainly to help you’, said Kyriaki to Frank, during a crisis in their marriage. ‘You married me only because you loved me’, answered Frank – a response which made Kyriaki furious but would probably satisfy immigration officers and proponents of marriage as a pure relation.

In a strikingly similar interaction, found in Euripides’ ancient Greek drama Medea, when Jason left Medea to marry another woman, Medea blamed Jason for being unappreciative of her help in acquiring the Golden Fleece. Jason angrily replied, ‘In return for my salvation, though, you got better than you gave’ (534–535). But what made Jason’s reaction so similar to Frank’s, was that Jason had refused to acknowledge the help of his wife Medea and instead said, ‘Since you raise a monument to gratitude, I consider Aphrodite alone the saviour of my expedition – of all gods and humans’. His gratitude to Aphrodite was because she sent Eros, the god of love, to help him. Jason continued ‘You do have a subtle mind. Yet to detail the whole story of how Eros compelled you with his inescapable arrows to save my skin would cause resentment’ (527–531) (Rayor Citation2013). Jason and Frank did not deny that the assistance of their wives was crucial to surviving and achieving their goals. But they both did not want to see their wives’ acts as gifts that generated the obligation of a counter-gift. Instead, they argued that these actions were only a manifestation of love and as such no expectation of acknowledegment or any other type of return could be expected.

The ethnographic material analysed in this article showed not only the inaccuracy of the dichotomy between love and interest, upon which the categorisation of marriages as either ‘sham’ or ‘genuine’ is based, but also the perils of this division, especially for women. Ironically for the state and its agents, love is the remedy to all ‘unacceptable’ marriages (‘forced’, ‘arranged’, ‘sham’) construed as bad for women. Nevertheless, romantic love, especially when it has different implication for men and women, may also place women in a disadvantaged position. These are important insights for understanding how love affects the dynamics of gender relations in cross-border marriages and marriages more generally. In that endeavour, state’s categorisation of cross-border marriages, such as the dichotomy of ‘sham’ and ‘genuine’, is misleading and of limited analytic value.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Saskia Bonjour, Katharine Charsley, Sébastien Chauvin, Nicole Constable, Janine Dahinden, Peter Geschiere, Joëlle Moret, the participants in the two Neuchâtel workshops in preparation of this Special Issue as well as the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback and criticism on earlier versions of this article. My involvement in this Special Issue became possible due to a short-term visiting fellowship in Neuchâtel by the nccr-on the move. I owe a special thanks to Janine Dahinden for her invitation to Maison d’analyse des processus sociaux (MAPS) at the University of Neuchâtel.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 In the Netherlands, there are three different types of unions that grant rights and obligations to two partners of opposite or same sex: marriage (huwelijk), registered partnership (geregisteerd partnerschap) and cohabitation contract (samenlevingscontract).

2 ‘Love’ is not explicitly mentioned in legal definitions of ‘sham marriage’. Nevertheless, the romantic love ideal informs the implementation by immigration officers of these laws and policies, the decisions of judges in legal cases against ‘sham marriages’ and political discourses (such as in parliamentary debates) on the topic (De Hart Citation2003; Bonjour and De Hart Citation2013; Pellander, Citation2021; Scheel Citation2017).

3 This is only for marriages that involve persons from places where marriage payments are assumed to be common practice.

4 This does not mean that all women in Greece express their love in that way. The norms and practices of love differ across generations, social classes, place of residence, etc.

5 However, if parents ask a high bridewealth claiming that they their daughter’s upbringing was costly, they might be accused that ‘they are selling their daughter’.

6 In order to see the similarities with other marriages, we certainly need studies that do not focus exclusively on the marriages of migrants – as is the usual tendency in migration studies (Dahinden Citation2016).

References

- Andrikopoulos, Apostolos. 2017. “Argonauts of West Africa: Migration, Citizenship and Kinship Dynamics in a Changing Europe.” PhD diss., University of Amsterdam.

- Andrikopoulos, Apostolos. 2018. “After Citizenship: The Process of Kinship in a Setting of Civic Inequality.” In Reconnecting State and Kinship, edited by Erdmute Alber and Tatjana Thelen, 220–240. Philadelphia: Penn University Press.

- Block, Laura. 2021. “‘(Im-)Proper’ Members with ‘(Im-)Proper’ Families? – Framing Spousal Migration Policies in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (2): 379–396. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1625132.

- Bonjour, Saskia, and Betty De Hart. 2013. “A Proper Wife, a Proper Marriage: Constructions of ‘Us’ and ‘Them’ in Dutch Family Migration Policy.” European Journal of Women's Studies 20 (1): 61–76. doi: 10.1177/1350506812456459

- Boulding, Kenneth E. 1973. The Economy of Love and Fear. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- Brennan, Denise. 2004. What’s Love Got to Do with It? Transnational Desires and Sex Tourism in the Dominican Republic. London: Duke University Press.

- Carver, Natasha. 2016. “‘For Her Protection and Benefit’: The Regulation of Marriage-Related Migration to the UK.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (15): 2758–2776. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2016.1171369

- Chauvin, Sébastien, Manuela Salcedo Robledo, Timo Koren, and Joël Illidge. 2021. “Class, Mobility and Inequality in the Lives of Same-Sex Couples with Mixed Legal Statuses.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (2): 430–446. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1625137.

- Cole, Jennifer. 2009. “Love, Money, and Economies of Intimacy in Tamatave, Madagascar.” In Love in Africa, edited by Jennifer Cole and Lynn M. Thomas, 109–134. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Cole, Jennifer, and Christian Groes. 2016. “Affective Circuits and Social Regeneration in African Migration.” In Affective Circuits: African Migrations to Europe and the Pursuit of Social Regeneration, edited by Jennifer Cole and Christian Groes, 1–26. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Collier, Jane. 1997. From Duty to Desire: Remaking Families in a Spanish Village. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Constable, Nicole. 2003. Romance on a Global Stage: Pen Pals, Virtual Ethnography, and “Mail Order” Marriages. London: University of California Press.

- Cornwall, Andrea. 2002. “Spending Power: Love, Money, and the Reconfiguration of Gender Relations in Ado-Odo, Southwestern Nigeria.” American Ethnologist 29 (4): 963–980. doi: 10.1525/ae.2002.29.4.963

- Dahinden, Janine. 2016. “A Plea for the ‘De-Migranticization’ of Research on Migration and Integration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (13): 2207–2225. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1124129

- D’Aoust, Anne-Marie. 2013. “In the Name of Love: Marriage Migration, Governmentality, and Technologies of Love.” International Political Sociology 7 (3): 258–274. doi: 10.1111/ips.12022

- De Hart, Betty. 2003. “Onbezonnen Vrouwen. Gemengde Relaties in het Nationaliteitsrecht en het Vreemdelingenrecht.” PhD diss., Nijmegen University.

- De Hart, Betty. 2017. “The Europeanization of Love. The Marriage of Convenience in European Migration Law.” European Journal of Migration and Law 19 (3): 281–306. doi: 10.1163/15718166-12340010

- Eggebø, Helga. 2013. “A Real Marriage? Applying for Marriage Migration to Norway.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (5): 773–789. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.756678

- European Commission. 2014. Handbook on Addressing the Issue of Alleged Marriages of Convenience between EU Citizens and Non-EU Nationals in the Context of EU Law on Free Movement of EU Citizens. Brussels: European Commission.

- Giddens, Anthony. 1992. The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Groes, Christian. 2016. “Men Come and Go, Mothers Stay: Personhood and Resisting Marriage Among Mozambican Women Migrating to Europe.” In Affective Circuits: African Migrations to Europe and the Pursuit of Social Regeneration, edited by Jennifer Cole and Christian Groes, 169–196. London: University of Chicago Press.

- Hirsch, Jennifer S., and Holly Wardlow. 2006. Modern Loves: The Anthropology of Romantic Love and Companionate Marriage. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Hochschild, Arlie. 1983. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. London: University of California Press.

- Hunter, Mark. 2010. Love in the Time of AIDS: Inequality, Gender and Rights in South Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Illouz, Eva. 2007. Cold Intimacies: The Making of Emotional Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

- IND. n.d. Marriage of Convenience. Accessed June 1, 2019. https://ind.nl/en/about-ind/background-themes/pages/marriage-of-convenience.aspx.

- Kulu-Glasgow, Isik, Monika Smit, and Roel Jennissen. 2017. “For Love or for Papers? Sham Marriages Among Turkish (Potential) Migrants and Gender Implications.” In Revisiting Gender and Migration, edited by Murat Yüceşahin and Pinar Yazgan, 61–78. London: Transnational Press.

- Leutloff-Grandits, Carolin. 2021. “When Men Migrate for Marriage: Negotiating Partnerships and Gender Roles in Cross-border Marriages Between Rural Kosovo and the EU.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (2): 397–412. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1625133.

- Medick, Hans, and David Warren Sabean. 1984. Interest and Emotion: Essays on the Study of Family and Kinship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Moret, Joëlle, Apostolos Andrikopoulos, and Janine Dahinden. 2021. “Contesting Categories: Cross-Border Marriages from the Perspectives of the State, Spouses and Researchers.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (2): 325–342. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1625124.

- Muller Myrdahl, Eileen. 2010. “Legislating Love: Norwegian Family Reunification Law as a Racial Project.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (2): 103–116. doi: 10.1080/14649360903514368

- Padilla, Mark B., Jennifer S. Hirsch, Miguel Munoz-Laboy, Robert E. Sember, and Richard G. Parker. 2007. Love and Globalization. Transformations of Intimacy in the Contemporary World. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Paxson, Heather. 2007. “A Fluid Mechanics of Erotas and Aghape. Family Planning and Maternal Consumption in Contemporary Greece.” In Love and Globalization: Transformations of Intimacy in the Contemporary World, edited by Mark B. Padilla, Jennifer S. Hirsch, Miguel Munoz-Laboy, Robert E. Sember, and Richard G. Parker, 120–138. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Pellander, Saara. 2015. ““An Acceptable Marriage” Marriage Migration and Moral Gatekeeping in Finland.” Journal of Family Issues 36 (11): 1472–1489. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14557492

- Pellander, Saara. 2021. “Buy Me Love: Entanglements of Citizenship, Income and Emotions in Regulating Marriage Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (2): 464–479. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1625141.

- Piot, Charles. 2015. “Kinship by Other Means.” In Writing Culture and the Life of Anthropology, edited by Orin Starn, 189–203. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rayor, Diane J. 2013. Euripides’ Medea. A New Translation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rebhun, L. A. 1999. The Heart is Unknown Country. Love in the Changing Economy of Northeast Brazil. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Rijksoverheid. 2009. Hogere Eisen Huwelijksmigratie En Inburgering. http://rijksoverheid.archiefweb.eu/#archive.

- Satzewich, Vic. 2014. “Canadian Visa Officers and the Social Construction of “Real” Spousal Relationships.” Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne De Sociologie 51 (1): 1–21. doi: 10.1111/cars.12031

- Scheel, Stephan. 2017. “Appropriating Mobility and Bordering Europe through Romantic Love: Unearthing the Intricate Intertwinement of Border Regimes and Migratory Practices.” Migration Studies 5 (3): 389–408. doi: 10.1093/migration/mnx047

- Smith, Daniel Jordan. 2009. “Managing Men, Marriage, and Modern Love: Women's Perspectives on Intimacy and Male Infidelity in Southeastern Nigeria.” In Love in Africa, edited by Jennifer Cole and Lynn M. Thomas, 157–180. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Thomas, Lynn M., and Jennifer Cole. 2009. “Thinking through Love in Africa.” In Love in Africa, edited by Jennifer Cole and Lynn M. Thomas, 1–30. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Tryfonidou, Alina. 2009. “Family Reunification Rights of (Migrant) Union Citizens: Towards a More Liberal Approach.” European Law Journal 15 (5): 634–653. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0386.2009.00482.x

- Wray, Helena. 2015. “The ‘Pure' Relationship, Sham Marriages and Immigration Control.” In Marriage Rites and Rights, edited by Joanna Miles, Rebecca Probert, and Perveez Mody, 141–165. Oxford: Hart.

- Wray, Helena, Eleonore Kofman, and Agnes Simic. 2021. “Subversive Citizens: Using EU Free Movement Law to Bypass the UK’s Rules on Marriage Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (2): 447–463. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1625140.

- Zelizer, Viviana A. 2005. The Purchase of Intimacy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.