?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

One decade after its introduction, the superdiversity concept introduced by Steven Vertovec has widely found echoes in migration research, but also in business studies, particularly those focusing on ethnic minority entrepreneurship (EME). In spite of conceptually embracing superdiversity in EME research, the multi-dimensionality of superdiversity in its original understanding appears to require further consideration. Dimensions currently overlooked in research at the nexus of superdiversity and ethnic minority entrepreneurship are: (1) ethnic but also religious and linguistic diversity of entrepreneurship, (2) entrepreneurial diversity regarding business-types and (3) incorporation of the characteristics of the city within its analytical unit. Based on an extensive site survey of ethnic businesses in Glasgow combining ethnographic assessment and available statistical data on the city districts, this paper reconceptualizes the entrepreneurial superdiversity to do justice to the on-going debates on superdiversity within migration research. In doing so, it proposes the Entrepreneurial Superdiversity Index (ESI), which is a viable method for approximating entrepreneurial superdiversity in cities. The ESI allows comparative analyses of entrepreneurial superdiversity within a specific city and potentially also between different cities internationally, which could be highly useful for policy-makers and planners alike. It also delivers grounds for developing a general index for superdiversity in further migration research.

Introduction

The superdiversity paradigmFootnote1 was ushered in by Vertovec's paper in 2007, finding wide echoes in current migration and diversity studies (Hall Citation2015; Kloosterman, Rusinovic, and Yeboah Citation2016; Wessendorf Citation2018) and now also broadly used beyond disciplinary boundaries (Vertovec Citation2019), including those focusing on ethnic minority entrepreneurship (EME). Whereas several studies have focused on measuring and assessing the link between ethnic (super)diversity and economic outcomes at the urban level using quantitative data (Kemeny Citation2012; Nathan Citation2016), Hall (Citation2015) takes an exceptional approach by exploring intra-urban transformation through superdiversity and entrepreneurship using an in-depth ‘trans-ethnography’ of ‘super-diverse streets’, assessing the urban space with regards to the diversity of ethnic businesses. In the EME field within business studies, this nexus of superdiversity and entrepreneurship has been sustainably set forward by scholars, such as Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon (Citation2011), Ram et al. (Citation2013) or Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy (Citation2015). However, often due to a lack of precise data on the multidimensional nature of superdiversity and entrepreneurship, the superdiversity in these contexts is mostly understood solely in terms of entrepreneurs’ ethnicity.

To transfer the actual intention of the superdiversity concept as proposed by Vertovec (Citation2007) into EME research, however, further dimensions of migration characteristics should be taken into consideration. Both the criticism of the so-called ethno-focal lens but also the city as the unit of analysis which Meissner and Vertovec (Citation2015) pointed out are merely touched upon and not fully conceptually followed in entrepreneurship literature. In fact, empirical works so far focus on the presence of ethnic business clusters in cities or discuss specific ethnic minority entrepreneurs’ (EMEs) activities in selected cities as part of an overall diversification of the urban population and economy. Empirical research on the superdiversity character of entrepreneurial endeavours in the urban context, i.e. focusing on the diversity of the EME businesses themselves instead of and beyond the ethnicity of the entrepreneurs is still largely missing. Moreover, research on entrepreneurial superdiversity normally base on case studies that are nationally and internationally not directly comparable. The lack of methodological approaches to (entrepreneurial) superdiversity appears to be crucial for the missing empirical evidence. In fact, comparative urban analysis with a quantifiable measure, such as an index, would support policy-makers and researchers alike in assessing best practices in urban policies and developing measures to counter issues of socio-spatial segregation and fragmentation.

By translating the ideas of superdiversity into the EME context on the empirical basis of intra-urban analysis of ethnic businesses in Glasgow, we call for a reconceptualization of the superdiversity debate in entrepreneurship research. This encompasses including more attributes of diversity of the ethnic minorities but furthermore also complementing the actual business perspective to the superdiversity debate. Based on qualitative and ethnographic empirical research, we also propose a novel tool, the Entrepreneurial Superdiversity Index, which is thought to be a viable method for approximating entrepreneurial superdiversity in cities. When adjusted further and taking more aspects of diversity into account, it could become the basis for usage on researching other superdiversity phenomena or overall superdiversity in cities. The development of such an indicator further allows intra- but also inter-urban comparative analyses of superdiversity. Through its facilitation of comparing urban districts with each other and also cities internationally, it could find broader usage also in the policy practice of urban development and planning.

Superdiversity of the entrepreneurial population

First of all, the original superdiversity debate is embedded in migration research (Amin Citation2002; Padilla, Azevedo, and Olmos-Alcaraz Citation2015; Gawlewicz Citation2016; Kloosterman, Rusinovic, and Yeboah Citation2016); to apply the concept to entrepreneurship, it is crucial to take ethnic minority and not only migrant entrepreneurs. As Vertovec argues on the new complexity of migration in today's societies, the multidimensionality goes beyond just the country of origin. It also encompasses the dynamic interplays of further variables, such as ethnic and religious backgrounds (which can differ within the same country of origin), the legal status and the migration channel (Meissner Citation2018). This leaves the migrant status of entrepreneurs only one of the different aspects attributed to them and not necessarily the core nor single condition impacting their economic and thus potential entrepreneurial activity.

The ethno-focal lens criticised in migration research (Glick-Schiller and Çağlar Citation2009; Meissner and Vertovec Citation2015) is another aspect which is still prevalent in most current studies conducted in entrepreneurship research and requires reconsideration. Most research on EME has so far focused on single ethnic minority groups of entrepreneurs, whereas depending on the study such ethnic background has been differentiated according to nationality (Home Office Citation2009; General Register Office for Scotland Citation2010), country of birth or ethnicity in a broader sense (cf. Census data from the Office of National Statistics Citation2011; Kelly and Ashe Citation2014), for example, Pakistani, Chinese or Polish EMEs (Zhou and Logan Citation1989; Pécoud Citation2004; Wang and Lo Citation2007; Vershinina, Barrett, and Meyer Citation2011; Fong, Chan, and Cao Citation2013; Lever and Milbourne Citation2014; Gawlewicz Citation2016; Lassalle and Scott Citation2018; Ryan Citation2018). There are also cases where even broader categories of EMEs, such as ‘South Asian’ (Ishaq, Hussain, and Whittam Citation2010), ‘Black Ethnic Minority’ or ‘Black African and Caribbean’ (Ojo, Nwankwo, and Gbadamosi Citation2013) are being used in line with statistical data available in the UK (e.g. Census 2011). Other studies focus on the comparison between two or more ethnic groups (Barrett, Jones, and McEvoy Citation1996; Wang and Altinay Citation2012; Storti Citation2014; de Vries, Hamilton, and Voges Citation2015), while recent policy-oriented papers consider the general population of EMEs in their analysis (Ram et al. Citation2013). However, in these instances, mostly due to the lack of appropriate data but also conceptualisation of superdiversity, further dimensions of diversity, such as legal or religious variables are not taken into account. The importance of certain individual and social attributes have been discussed extensively though, such as in the context of ethnic social capital used for creating opportunities and starting-up within the co-ethnic community (Waldinger Citation1993, Citation2005; Portes and Sensenbrenner Citation1993; Deakins et al. Citation2009; Kloosterman Citation2010) or within ethnic enclaves (Zhou Citation2004).

Despite the challenges of capturing the complexity of the superdiversity phenomenon at the urban level and on a larger scale, it has been pointed out that grasping the multiple dimensions are essential for the researcher especially to more adequately inform policy-making (Deakins et al. Citation2009; Ram et al. Citation2013; Carter et al. Citation2015). In this context, literature on mixed-embeddedness has considerably contributed to conceptualising such multidimensional aspects of EME (Kloosterman and Rath Citation2001; Kloosterman, Rusinovic, and Yeboah Citation2016), in particular discussing their embeddedness in social networks and institutional structures, yet it still (so far) focuses on the ethnic lens (Jones et al. Citation2014). To further explore the complexities of entrepreneurship in urban context from a lens of superdiversity, there is indeed a need to go beyond the ethno-focality and to consider a wider range of diversity attributes in entrepreneurial activities.

One approach to capture superdiversity could be taken from anthropological and linguistic research (Blommaert Citation2013; Wessendorf Citation2013; Maly Citation2016). Visible signs of diversity attributes on the ethnic minority businesses are main clues for the superdiversity of entrepreneurial activities in the urban settings in analysis. These visible signs, be it as part of promoting Kosher or Halal products or accommodating multilingual services within the business, can be regarded as a proxy of the degree in which the EMEs engage in ethnic or religious minority businesses, contributing to the superdiversity of the local market beyond the single ethnic market. As the trans-ethnographic approach states, too, such ‘visual arrangement of the shop fronts, which must do the work of attracting a base of customers’ (Hall and Datta Citation2010, 71) are ‘choreographed arrangements of urban surfaces and spaces by proprietors’ (Hall and Datta Citation2010, 70). As a matter of fact, linguistic landscapes are also one of the core aspects discussed in superdiversity research (Maly Citation2016; Vertovec Citation2019) and could open new field also for the study of EME superdiversity.

Superdiversity in entrepreneurship

When diversity is discussed in business terms, entrepreneurship researchers deal with the actual diversification processes of entrepreneurial activities and actions taken to ensure the sustainability of their businesses. To enlarge their limited co-ethnic client base, EMEs engage in breakout strategies and adapting their product and services to access the indigenous or mainstream clientele locally, thus contributing to the diversification of business offering (Jones, Barrett, and McEvoy Citation2000; Engelen Citation2001; Smallbone, Bertotti, and Ekanem Citation2005; Rusinovic Citation2006; Kitching, Smallbone, and Athayde Citation2009; Lassalle and Scott Citation2018). These diversifications include internationalisation of entrepreneurship and the transnationalisation of entrepreneurs and their business, two aspects that have come into focus in EME research (Portes, Guarnizo, and Haller Citation2002; Vershinina et al. Citation2019). One novel aspect that entrepreneurship research can thus contribute to the superdiversity debate are such processes which change and diversify the nature of businesses. In fact, research on superdiversity in entrepreneurship is yet to study the nature and diversity of business types, in which EMEs engage. Ethnic retail has been intensively researched (e.g. Phizacklea and Ram Citation1996; Ishaq, Hussain, and Whittam Citation2010) and profiles of shop types have been surveyed ethnographically (Hall Citation2011), however, a systematic consideration of the diversity of the EMEs regarding the businesses as such as well as the combination of the diversities of EME and businesses have not been exhaustively explored. Such endeavours highlighted by previous research on EME also have high relevance for society, both with regards to the integration of migrant and ethnic minority population (Rodríguez-Pose and Hardy Citation2015; Wessendorf Citation2018) but also as a crucial positive impulse of creativity and innovation as more general drivers of economic development (Deakins et al. Citation2009; Kemeny Citation2012).

Though insightful research based on quantitative data are available, methodologically, merely quantifying the amount of EMEs in one specific city or even the accumulation of EMEs on a national level do not seem to do justice to the phenomenon of superdiversity in entrepreneurship. What must be scrutinised is whether and what business diversity can be found within one specific ethnic minority group of entrepreneurs on the one hand; and, on the other, how the diversity of businesses is also distributed among the diversity of the existent ethnic minorities of entrepreneurs. Such combination of the diversity of business types in relation to the diversity of ethnic minorities, and further considering attributes of the diversity in religion and language, or even gender perspectives, is needed in order to capture and analyse the complexity of superdiversity in entrepreneurship. A more comprehensive picture of the entrepreneurial landscape within a city can also help policy-makers as mere numbers of EMEs do not indicate the business types prevalent in an area and where support could be needed by the existent and potential ethnic minority population.

Superdiversity in the urban context

EME literature has been studying and pointing out the importance of locality for entrepreneurial ventures but also for policy responses (Syrett and Sepulveda Citation2011). Migration and (super)diversity studies have also acknowledged the city as the most practical and appropriate unit of analysis (Amin Citation2002; Piekut et al. Citation2012; Meissner and Vertovec Citation2015) and have also recently been discussing the urban context (Piekut et al. Citation2012; Buhr Citation2018; Harries et al. Citation2018). However, the urban spatial characteristics still appear not to be properly operationalised in EME research. In this regard, Nathan (Citation2016) stands out as he proposes to evaluate the performance of ethnic businesses using the urban level as the unit of analysis, using the approach of the fractionalisation index, whereas the actual spatial dimension for EME within the city in terms of district or neighbourhood level is still to be developed. Embedded in the context of global city London, Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon (Citation2011) have contextualised the entrepreneurial activity in terms of spatial and ethnic clustering of business activities, but focusing on specific communities. The local spatial context on the diversification and diversity of EME is a topic that needs to be further discussed. Cutting-edge attempts of urban researchers, such as Hall (Citation2015), to approach the city from different perspectives, using macro-level ‘data sets on population census, indices of deprivation and locality’ (Hall Citation2015, 7) as well as ethnographic data and mapping on the street-level provide insightful perspective for the consideration of spatial (local) contexts of EME (Hall Citation2011).

Whereas the city has been used as an administrative unit and level of analysis in research on EME, particularly due to the pragmatic reason of cumulative data being mostly available on that level, the urban context regarding intra-urban data on district levels has been neglected so far. As a matter of fact, district or even neighbourhood level data on entrepreneurship and attributes of diversity are basically inexistent. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises database can give some idea of diversity among enterprises, such as the citizenship of the owner, yet fully lack in precise data on district level and do not cover issues of ethnic or religious minorities. Retrieving information from publically accessible databases, such as Company House, could be an initial feasible approach to entrepreneurship data, yet these are often not comprehensive, up to date and further lack details on attributes covering superdiversity dimensions. In contrast to entrepreneurship studies, neighbourhood level and even smaller scale street-levels are common in urban anthropology and geographical studies, including also surveys by face-to-face (Hall Citation2011, Citation2015). However, surveys and mappings of ethnic minority businesses are limited to the study of their ethnicities (Werbner Citation2001; Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011). Further research on superdiversity of EME should consciously take the urban lens to the phenomenon and also take into account intra-urban differences in diversities of ethnic but also business diversities. The inclusion of the urban context consequently also requires taking into consideration different levels of diversification of the ethnic minority population in the districts, which is simultaneously (except for commonly city centre) an indicator of the diversity of the potential ethnic minority client base for EMEs, instead of concentrating merely on only one specific ethnic population. In fact, research has shown that serving the co-ethnic niche market is usually the primary and initial stage of entrepreneurship among ethnic minorities, followed by stages of diversification of both products and customer base (Rusinovic Citation2006; Lassalle and Scott Citation2018). Through such diversification processes of entrepreneurial activities, EMEs can reach a mixed clientele beyond the initial co-ethnic niche.

Following these three broader agenda for research on superdiversity in entrepreneurship and its methodological obstacles, this paper attempts to present empirical research on entrepreneurial superdiversity, which (1) goes beyond the ethno-focal lens and studies the diversity itself of ethnic minorities’ entrepreneurship but also include further attributes of superdiversity; (2) takes into consideration the diversity of business types of EME in the analysis. By developing an Entrepreneurial Superdiversity Index (ESI) on the basis of the ethnographic assessment combined with available statistical data, it (3) presents an urban analytical approach for comparing the diversities in the EME against the background of the ethnic residential population and the businesses types to identify areas of entrepreneurial superdiversity.

Capturing superdiversity in the city: selecting the field

In accordance with the proposals of Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon (Citation2011), Meissner and Vertovec (Citation2015) and Smallbone, Kitching, and Athayde (Citation2010), the analytical unit for entrepreneurial superdiversity should be on the local city level. Yet, such urban context should be further broken down and investigated on a smaller scale by means of intra-urban areas, as the city level itself does not give any indications of the diversities of EME within the actual urban context apart from illustrating ethnic clusters (Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011). As Hall (Citation2011) suggested, superdiversity and diversification within the urban landscape are better captured using the combination of detailed survey techniques and ethnographic work. This also allows the researchers to collect reliable data especially in the absence of comprehensive urban data on diversity at such small district-level. The consideration of which area should be actually surveyed base on the analysis of available data first.

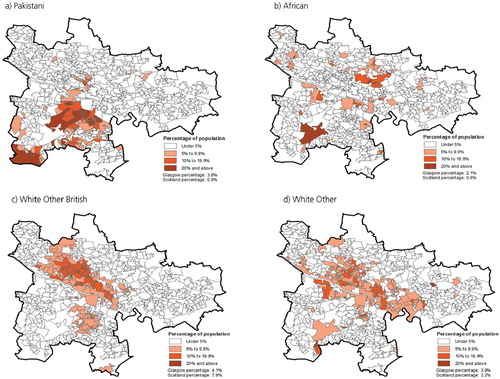

Glasgow with its vibrant entrepreneurial landscape, its largest Scottish urban economy and a diverse ethnic minority population, is an ideal field for in-depth intra-urban research on superdiversification of ethnic entrepreneurial activities, yet available data are limited to either larger scales or larger ethnic/racial groups as per latest 2011 Census data for Scotland (Krausova and Vargas-Silva Citation2013). Nonetheless, though imprecise in the ethnic breakdown on the district level, such data and also previous literature already indicate the superdiverse dynamics in this particular city, which has recently experienced a strong increase of its ethnic minority populations from 13% in 1991 to 21% in 2011 (Kelly and Ashe Citation2014). Apart from strong increases of the populations of Black African and Caribbean (890%), Other Black (339%), Chinese (176%) and Other Asian groups (176%), Glasgow has also been the site of recent arrivals of white migrants from A8 countries after the 2004-enlargment of the European Union (Stevenson Citation2007; General Register Office for Scotland Citation2010; Glasgow City Council Citation2012),Footnote2 experiencing also the arrival and increase of ethnic minority entrepreneurs in the city. Using such areal data basing on Census data already allows an approximation to capturing the ethnic diversity of the residential population.Footnote3 Basing on such data on ethnic minority distribution, we propose building a cumulative indicator of the superdiversity of ethnic minorities in the districts within Glasgow, illustrating not simply the concentration of each of the Pakistani, African, White Other British, White Other etc. population, but the areas with the highest diversity of ethnic minorities.

In order to select the relevant areas to conduct both the site survey and the ethnographic assessment, we first used data on ethnic population found in previous research (Kelly and Ashe Citation2014, ) with the intention to select, compare and contrast entrepreneurial superdiversity between iconic, vibrant and diverse areas with high concentration of ethnic minority enterprises () but also between areas of different level of deprivation, using the Scottish Indices for Multiple Deprivation (SIMD).

Encompassing seven weighted domains, including income, employment, geographical access and housing, the SIMD is used for monitoring also ethnic minorities in such deprived neighbourhoodsFootnote4 (Mokrovich Citation2011; Kelly and Ashe Citation2014). The SIMD in the context of diversity in EME is insofar of higher relevance as this is the factor which takes the urban analytical unit properly into consideration. Though the selection of urban areas for the study of superdiversity in entrepreneurship should not necessarily only focus on the higher density of ethnically diverse population and such in deprived areas, but with regard to issues of strong societal implication (Hall Citation2011), the pre-selection or at least the consideration of the index as part of the superdiversity analysis appears to be more than reasonable.

The third aspect to be taken into consideration for selection of further in-depth research on the superdiversity phenomenon in EME is the vibrancy of ethnic businesses in the selected areas. Basing on previous research on the Glaswegian entrepreneurial ecosystem in particular (Lassalle and Johnston Citation2018) but also on migrant communities (e.g. Piętka Citation2011; McGhee, Heath, and Trevena Citation2013), as well as further sources of information, such as mass media coverage and knowledge of local residents, areas with high entrepreneurial activity, especially of ethnic niche markets, were also taken into consideration. While in the selected areas, emerging areas and streets were added according to the local population and EMEs themselves advising on further business areas for consideration.

Ruling out the city centre itself as to avoid the impact of diversification deriving from the unique and ubiquitous context of urban centres, the areas were selected according to following three dimensions of diversityFootnote5: (1) areas with high concentrations of ethnic diversity, which is a prerequisite for the development of an ethnic niche market and also ethnic diversification of the local customer base along with the businesses; (2) areas with high concentration of businesses with ethnic minority labelling, especially focusing on streets well-known for their business activity and vibrancy; and (3) reflecting the diversity within the Glaswegian city itself, areas with different multiple deprivation indices according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD).

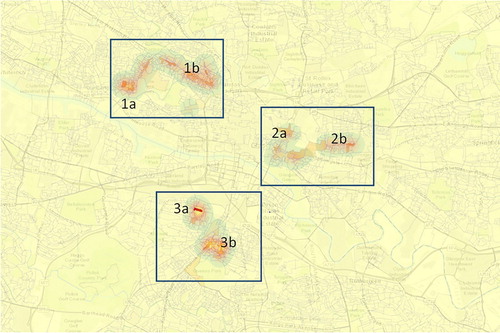

The final selection consisted of three areas: West End, in particular the University of Glasgow area (1a) and Kelvinbridge/Maryhill (1b), East End with High Street (2a) and Duke Street (2b) areas, and South Side covering Eglinton Toll (3a) and Govanhill (3b) areas. The areas of entrepreneurial activities refer to business streets, such as Great Western Road, Maryhill Road, Byres Road in the West End, Duke Street, High Street in the East End, Victoria Road, Pollockshield Road, Allison Street in the South side, since the rest of the areas are primarily residential with none to very limited number of businesses.

Capturing superdiversity: surveying the sites on ethnic minority entrepreneurship

The subsequent site survey on the entrepreneurial superdiversity focused on three different aspects of diversity dimensions. The selected areas were surveyed for EME (N= 247) by collecting data not only on (1) the ethnicity of the business (ethnic labelling), but also (2) the business type, and when visible also (3) religious and linguistic signs. The ethnographic assessment of viewing and categorising the sites and businesses as in linguistic landscaping (Blommaert Citation2013; Maly Citation2016) was carried out by two independent researchers equipped with GPS-located application on mobile devices recording the site survey results, walking and surveying businesses in the three selected areas presented above () for a fine-grained collection of data. Importantly, since the interest were on the visible diversity in entrepreneurial activity in these urban districts, which are also the access point for the ethnic minority customers in these areas, the focus was not on the ethnicity of the owner but on the ethnic labelling and visible signposts, which are reflections of the strategic intentions regarding the targeted market by ethnic businesses. For this conceptual purposes, EMEs that have totally broken out to the mainstream market – i.e. ethnic entrepreneurs serving non-ethnically labelled goods or services to a non-ethnic mainstream clientele – were excluded, and for the same reason, included those engaging in ethnic businesses owned and ran by entrepreneurs with no ethnic minority background but who purposefully either target an ethnic minority population or use an ethnic label to their product (e.g. a British owned and ran Vietnamese restaurant) – which is in fact a novel dimension of diversification of the entrepreneurial landscape and undeniably contributes to the superdiversity of ethnic entrepreneurship.

Pre-categorising the diversity of ethnic backgrounds according to the statistically available data in the UK on the largest groups of ethnic minority population, the categories of business types were also developed on the basis of administrative categories of economic activities used in official occupational and labour statistics of the Office of National Statistics. Accordingly, of the 247 total businesses identified and surveyed, the largest group of business types were restaurant and cafés (98), followed by convenience stores (74) and beauty services (27). Further businesses were categorised as design & interior and fashion (13), health & wellbeing (11); below ten each were businesses in financial and legal services (6), travel services (6) and internet & communication technology (4), and further eight miscellaneous. For the ethnic labelling, the majority of businesses identified as using ethnic labelling in the selected areas concentrated on businesses of Indian and Pakistani (49), Chinese (31), followed by Sub-Saharan African (14), Other South Asian (12) and Other Muslim origin with no specific visible ethnicity indication (26), but signs of ethnic businesses through the products and services presented as well as the linguistic landscape. Moreover, there were businesses assessed as Other Middle Eastern (6), Caribbean (6); among non-British White businesses, ethnic labels identifiable were Italian (7), Polish (8), Other Eastern European (4), such as a convenience stores with flags of multiple Baltic and Eastern European countries on the shop front and Other Europeans (12). Last but not least, 66 further businesses at least using ethnic labels or providing ethnicized services and products, such as ‘American’ nail salon, ‘German’ kitchenware or kebab stores without explicit linguistic, religious (Halal) or other indications of ethnicity, were also surveyed.

Furthermore, as the locational aspect of the city-level analysis of entrepreneurial superdiversity was crucial, these data were collected with their GPS coordinates. In addition, observations were complemented by a dozen of short interviews with several entrepreneurs and employees on their customer base and their ethnic labelling. The full data set also included the survey of landmarks, such as religious, ethnic cultural and educational institutions to characterise the areas in their ethnic diversity of the residential population. The subsequent spatial analysis was conducted using ArcGIS 10.6.

Sighting entrepreneurial superdiversity in Glasgow: empirical findings

While the West End and East End show fairly different pictures of the entrepreneurial diversity within Glasgow despite their similarity in terms of ethnic population density and deprivation, the most intriguing findings is the case of the two local areas in the South side of Glasgow (for descriptive findings of the other areas, see Lassalle and Johnston Citation2018). The surprising empirical results in South side emphasise the necessity and viability of research on the urban analytical unit, particularly of in-depth research on even smaller scale intra-urban contexts (Hall Citation2011, Citation2015; Wessendorf Citation2013). By combining a site survey approach (‘surveying’) with an ethnographic assessment (‘sighting’) of different selected areas of Glasgow, an index could be designed, aiming at measuring (or more approximating) entrepreneurial superdiversity at the intra-urban level in selected areas. Both methods of data collection provided interesting and surprising results due to the combination of crucial factors considered to define the multidimensional nature of superdiversity in general (Vertovec Citation2019) and indeed entrepreneurial superdiversity (diversity of EME, diversity of business types and diversity of population in the neighbourhood).

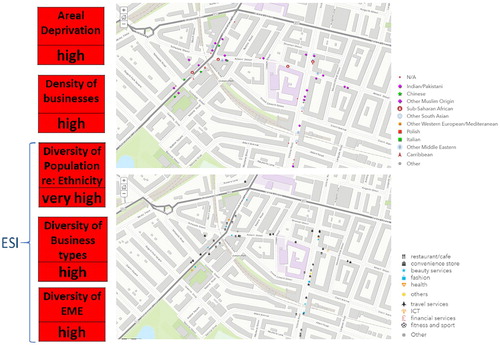

The area of the South side itself has a large ethnic population with a moderately diversity of ethnic populations and in any case an entrepreneurial landscape highly different from the local Scottish White population. The differences in the entrepreneurial (super)diversity of the two sub-areas of Eglinton Toll and Govanhill, however, lies in the diversity of the ethnic minority businesses regarding both their ethnicity and the business types. Whereas the area of Eglinton Toll can be regarded as a strong ethnic clustering of Indian/Pakistani businesses, therefore – according to literature so far – would be characterised as a superdiverse area (Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon Citation2011; Ram et al. Citation2013), the actual diversity of the businesses is extraordinarily low. There are primary groceries and convenience stores, with some individual travel agencies, yet the area is characterised by a high density of similar business types of the same ethnic background, i.e. South Asian. This reflects a classical ethnic cluster matching with previous accounts on EME.

Walking down the streets of Eglinton Toll, one loses sense of being in a Scottish neighbourhood; instead, we see characteristics of clustering area from a single ethnic group. As reported by Kelly and Ashe (Citation2014), close to 25% of the population of the area have a Pakistani ethnic identity (see also ). This is reflected in observation of visitors and shop owners on the streets. There is little traffic from visitors; those passing by are actually coming to the convenience stores or to the few other businesses (barbers, ethnic-focused legal advisers or travel agencies with shop front in Arabic). Many are dressed in traditional clothes from South Asia, and the very few women encountered are wearing the veil. Men, on their side, are wearing longer dresses and traditional hats, whereas shop owners (also from South Asia), are standing or sitting in front of their shop, speaking to each other in their home language. The concentration of similar businesses also leads to collaborative practices, as they are ready to support other shop owners and help them with products that they would lack in their stocks. In terms of diversity landscape, front shops also show a lack of diversity. Most of the shops are convenience stores (which constitute the majority of businesses in the area; cf. ) and their shop fronts display similar signs of ethnic labelling with most of the writing in Arabic, Halal and religious signs and references to South Asian products. Interestingly, the businesses are clustered, with no space in-between the shop fronts, aligning in rows of very similar businesses, providing food products (meat, vegetables, and fruits) and household goods mostly to the ethnic community (as evidenced by our observation inside the different shops). By going inside the shops, we see a mixture of South Asian food and household ware, one would rarely see in a British kitchen, all labelled for an ethnic minority clientele. All products are densely packed into small shops. Overall, the area is an ethnic cluster with a high ethnic population from one ethnic group, and a business cluster of similar businesses, operating in the same sector and serving a customer base constituted of co-ethnics for the largest part, which we assessed based on both the languages (spoken or visible) and visible signs on the shopfronts ().

Figure 3. South Glasgow – Eglinton Toll (above: density of EME, below: diversity of business types).

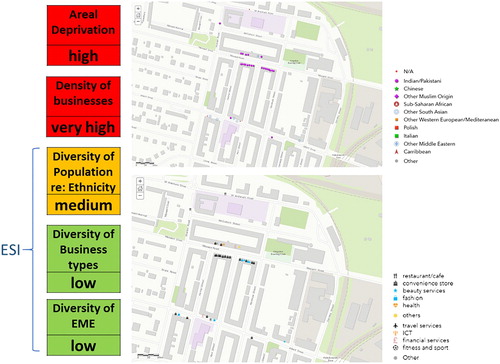

In contrast to this rather homogenous pattern of Eglinton Toll, the other area of the South side of Glasgow, i.e. Govanhill, is characterised by both higher diversity of ethnic backgrounds as well as higher diversity of business types of EMEs (). Govanhill in this respect exemplifies a real superdiversity of EME. The superdiverse nature of entrepreneurship here is characterised not only by the number of ethnic minority population, as in the case with Eglinton Toll, but moreover the diversity of the ethnic backgrounds of EMEs which is very large, as well as the high diversity of businesses prevalent in the area, making a highly dense ethnic minority entrepreneurial area. Apart from the classical ethnic minority businesses in grocery and gastronomy, the businesses also offer hairdressers, beauty but also financial and other services targeting a larger ethnic minority customer base. For example, one of the local shops, an Iranian hairdresser, serviced not only co-ethnics but also Scottish clients and other ethnic minorities. Likewise, a neighbouring Nigerian convenience store served also other clients beyond their co-ethnic initial market of Nigerians, such as French-speaking African and Caribbean customers as well as (more surprisingly) Romanian customers with poultry. These cases exemplify the diversity of the customer base in the area, which is reflected in the diversification of entrepreneurial activities, too.

The contrast between Eglinton Toll and Govanhill (Alison Street/Victoria Road area) is striking. The overall cityscape is much brighter and much more active, not just constituted of busy shops but with more space between larger businesses with spacious and brighter colourful displays as well as larger roads and larger sidewalks. We see far more traffic (cars, buses, pedestrian, and delivery trucks) in what is a busier and lively area. Moreover, people on the street are very diverse in terms of ethnicity, age, social level (although mostly working or lower middle class), and gender. In ethnic terms, there are local Scottish people as well as Kurdish, Romanian, Poles, Nigerian, etc. These people are going to work, or go shopping, therefore passing by or actively consuming (but nobody sitting and dwelling on the streets). On the business landscape, instead of blind small shops, businesses have large glass windows at the shop fronts (as for example a very bright cake shop, a flowery delicatessen shop front or a very open display hairdresser). This represents the need to attract the customer or passer-by, inviting them to look, come in and buy. Compared to the ethnic-based clientele of Eglinton Toll, businesses in Govanhill are competing on the various ethnic and sectoral market segments. Similar to the population, businesses display a wide diversity of ethnic labelling. Interestingly, in addition to these diversities of client-base and of ethnic businesses, the entrepreneurial landscape is complemented by a high diversity of business types, where car concessionaries are located aside of hairdressers/barbers and restaurants. A delicatessen with colourful front shop, adjoin a travel agent and a nail bar, etc. In addition, when entering one of the grocery shops, we see that there is a range of products available, targeting different ethnic groups (such as a Romanian shelf in a Polish business). Going further on the street, we see adverts in different languages in an Iranian-run barber shop. Even phone cards for international calls are more diverse and do not focus on one specific country or region.

Despite similar selection criteria for both area, i.e. high social deprivation and high (Govanhill) to very high business density (Eglinton Toll), the two areas present very different levels of entrepreneurial superdiversity. The findings from the ethnographically assessed site survey reveal two very different stories of entrepreneurial (super)diversity: on one side, a non-diverse, ethnically clustered area of Pakistani and Other South Asian Muslims in Eglinton Toll (); on the other side, only a few hundred metres away, the vibrant, multi-ethnic, and diverse hub of Govanhill, with a high level of diversity in business landscape with ethnic shops of diverse background (), serving not only their ethnic market but the diversity of communities in the area, and operating in diverse sectors.

Consequently, when superdiversity and entrepreneurship is only studied on a larger scale of urban context and also focuses on hubs with high ethnic minority population of one ethnicity (taking an ethno-focal lens) and only taking into consideration generically entrepreneurship without considering the diversity of business types, the actual superdiversity of entrepreneurial landscapes would not be properly captured. Though previous research on EME focusing on specific ethnic communities gives us important insights into diverse dimensions, including accesses, barriers and specific resources for these ethnic minorities, thus, is crucial for better understanding the ethnic entrepreneurship as such, the approach presented here has revealed quite a significant distortion of the picture. Scaling down of research on urban district-level and also focusing on the diversity in diversity of EME with regards to further dimensions, such as business types, appears to be the appropriate approach for grasping the superdiversity phenomenon in entrepreneurship.

Approximating entrepreneurial superdiversity: proposing a conceptual framework

On such basis of multidimensional diversity indicators presented above, we finally propose the usage of a so-called Entrepreneurial Superdiversity Index (ESI), which takes into account several of the criticism voiced on the research surrounding entrepreneurial superdiversity. Calculating the intensity of diversity for each sub-area, the ESI considers the multidimensional diversity of business types, the EME as well as the ethnic population. Additionally, the density of businesses and the areal deprivation including the diversity of socio-economic population data are taken into account as part of the overall selection criteria of the site surveys ().

Table 1. Entrepreneurial Superdiversity Index on cumulative diversity indicators.

The main advantage of a quantification is the comparability of neighbourhoods with each other and, thus, its potential usage in administration to monitor developments within cities and regions as it is already done in other contexts, such as integration monitoring in some cities or economic or social development on a larger scale in international indices. Fully capturing the complexity of a phenomenon with numbers is generally difficult, yet the proposed ESI builds on the most widespread linear aggregation of composite indices suggested by the OECD and applied widely by policy-makers and planners alike for common indices, such as the Human Development Index by the UNDP.Footnote6

The Entrepreneurial Superdiversity Index (ESI) measures achievements in three key dimensions of evidence of superdiversity in entrepreneurial activity in each of the areas surveyed: (1) the ethnic diversity of the population (for customer base), (2) the diversity of business types, and (3) the diversity of ethnic minority entrepreneurs, based on visible signs of ethnic diversity of the businesses. Each of these 3 indicators is first assessed (through the site survey, available statistics and ethnographic assessment) and is subsequently expressed as a score from low (=0), middle (=1), high (=2) to very high (=3). All indicators are then weighted and aggregated in the ESI using the following formula:

The aggregated numerical results for each indicator provide a level of diversity ranging on a spectrum from ‘low’ (0–2 points) entrepreneurial superdiversity to ‘very high’ (7–9 points) entrepreneurial superdiversity for each of the area selected.

This quantitative assessment can be used to capture or at least approximate the different dimensions of superdiversity in entrepreneurship. The results provide a level of diversity ranging on a spectrum from ‘low’ entrepreneurial superdiversity to ‘very high’ entrepreneurial superdiversity for each of the area selected. In that sense, Eglinton Toll and Govanhill present very different superdiversity landscape, despite similar level of high economic and social deprivation.

The main claim of superdiversity is the complex interaction and overlapping of different dimensions, which contribute to the diversification of diversities occurring in the cities. However, as presented above, recent studies on superdiversity of entrepreneurship has been either comparatively analysing on a city level or only focusing on singular ethnic entrepreneurs to be illustrating the diversification. This approach of subtle distinction of dimensions and suggesting an overall entrepreneurial index for superdiversity is novel and closer to what has been described as the superdiversity phenomenon in its multidimensional nature.

In addition to the diversity of EME as well as the diversity of business types deriving from own extensive fieldwork, the spatial dimension of this superdiverse ethnic minority entrepreneurial landscape is considered in the assessment of entrepreneurial superdiversity. By taking into account the multidimensional neighbourhood deprivation index of SIMD among the area selection criteria, the overall environment of the EMEs becomes clearer. The ESI then adds a layer on understanding the customer base as well as the physical and social environment of the businesses, therefore complementing works initiated by Hall (Citation2011). The relation between the different degrees of deprivation to the degree of diversity and diversification in entrepreneurial activities, however, requires further in-depth analysis by qualitative methods delving into the different impacting factors of the entrepreneurial environment for these EMEs in each of the socio-spatial contexts given.

Furthermore, this approach of superdiversity also breaks with the notion of the criticised ethno-focal lens (Meissner and Vertovec Citation2015) when studying the activities of EMEs. By collecting and analysing data on the whole breadth of EMEs (and on entrepreneurs targeting ethnic minority clientele) in specific locations instead of concentrating on comparative analyses of singular ethnic clusters one with another, this study succeeds in better grasping the nature of superdiversity in its actual extent. The viability of this approach is clearly demonstrated in the cases of the ethnic cluster of Eglinton Toll, which shows little diversity with regard to business types. Areas, such as Govanhill, however, show that there are indeed even more diverse areas, which means not only ethnically, but also by businesses as well as the residential population. These findings clearly show how much breaking the ethno-focal lens can contribute to better understanding ethnic entrepreneurial superdiversity. The potential impact of such research on superdiversity in EME can improve policy-makers and institutions’ understanding of the phenomenon, refocusing the superdiversity lens instead to support initiatives for prospective or new entrepreneurs.

Despite this novel and unique contribution to the superdiversity debate in entrepreneurship as initiated by Sepulveda, Syrett, and Lyon (Citation2011), some limitations must also not be ignored. Although the superdiversity notion has been extended to also business types and the ethnic diversity as such, going beyond conventional approaches of the ethnic lens, superdiversity as a phenomenon has even more dimensions which need to be further investigated. Superdiversity of urban society, for example, also discusses linguistic and religious diversities as well as legal status (Blommaert Citation2013; Vertovec Citation2019; Meissner Citation2018). These issues would be difficult to collect as a dataset, however, would give the dimension and extension of entrepreneurial superdiversity even more nuances. Such studies could also contribute to connect the idea of superdiversity of EME with the idea of entrepreneurial ecosystem as the accesses to resources also depend on them, e.g. legal status for accessing public support or linguistic barriers or advantages to access further ethnic niche markets. Furthermore, it is surely also a limitation that the field works extended ‘only’ to three larger areas within Glasgow, whereas an even large-scale study could result in more detailed results, as well as qualitative in-depth interviews will be able to deliver to the entrepreneurial activities and strategies more in detail, too. Similar critique could be also voiced regarding the extent of the ethnographic assessment of the exterior of businesses. Further fieldwork delving also into the interior (Hall Citation2011) of EME businesses could be revealing a more thorough assessment as not only the shopfront signature, but, as alluded in the ethnographic account earlier, also different dimensions of diversity regarding the products and the target groups could be studied. As some languages are of ‘higher symbolic value’ (cf. Duarte and Gogolin Citation2013), thus, being used for marketing reasons, further research into the interior could also give a more detailed views on the actual ethnic background of the entrepreneur (e.g. French restaurants or American nail salons of non-Francophone or non-Anglo-Saxon entrepreneurs). However, it must also be noted that this was a first step towards capturing the richness of superdiversity in a specific location, already quite successful in its extent, which will be further amplified in future and could be even better concretised if diversity data on entrepreneurship broken down to the urban district level were to become available in public statistics.

Conclusion

This paper contributes to the burgeoning debate on and application of the superdiversity concept in social and business studies and to give an impulse for reconceptualizing it for the entrepreneurial field. We call for an increased scrutiny of entrepreneurship and its diversification as such, as this is one of the core elements which entrepreneurship studies bring into the debate on superdiversity. At the same time, more insights from migration research have to also be incorporated into entrepreneurship. For EME, this means that the diversity on the migrants side themselves, by breaking the ethno-focal lens, but also further aspects of the migrant entrepreneurs, such as their migration history or legal status, have to be better conceptualised into entrepreneurial contexts. Last but not least, the unit of analysis of city has been already identified, but incorporating the urban context, if not consulting also interdisciplinary insights from urban studies, to better grasp urban dynamics of ethnic minority (and indeed migrant) entrepreneurship emerges as crucial. As not all areas of the city are affected by the superdiversity dynamics, smaller-scale qualitative works as well as ethnographic approaches are recommendable to grasp the superdiversity in ethnic entrepreneurship and in business activity at the intra-urban level (see also Hall and Datta Citation2010). Especially not all EMEs have the desirable environment for their entrepreneurial endeavours in all areas within the city is a highly politically relevant issue to be further dealt with to ensure that ethnic minorities and migrant individuals receive appropriate tailored support to help them starting-up and sustaining their businesses in a diversity of sectors.

Further research could also shed light on diversification strategies of EMEs regarding the mechanisms of diversifying the customer base from co-ethnic niches to either further ethnic minorities or the mainstream population. Another crucial aspect to be considered for further research is the issue of the transnationality of migrants regarding their social and economic activities. EMEs are increasingly involved in cross-border economic activities which go beyond the well-researched mechanisms of international entrepreneurship. Transnational manifestations of entrepreneurship, in particular regarding the actual business strategy in servicing an ever-increasing diversity of customers and benefiting from cross-border mobility and practices, i.e. activities beyond and behind shopfronts, deserve more attention as they add another layer of the diversification of society and, thus, also entrepreneurship.

The proposed Entrepreneurial Superdiversity Index incorporates both migration and urban aspects of the original idea of superdiversity and entrepreneurship (Meissner and Vertovec Citation2015) into EME research and gives also a first step to operationalise the entrepreneurial superdiversity in empirical terms. Acknowledging that it is so far a mere approximation to entrepreneurial superdiversity, where further exploration especially regarding the available data and qualitative research on each of the entrepreneurial contexts as exemplified above, but also debates on the criteria and the weighing of the factors are needed, the approach presented in this paper offers grounds for a more systematic inter-urban and intra-urban comparative analyses of superdiversity in entrepreneurship and can be regarded an important impulse for further research.

Such approaches allowing inter- and intra-urban comparison are also crucial for better practices in urban planning and policy. The concept of the ESI in fact offers strong potentials to be applied to the quantification, which in turn allows large-scale inter-urban comparative analyses on migrant (super)diversity in general. The conceptual idea and methodological approach which encompasses quantitative and qualitative capturing of superdiversity phenomena could be replicated and adjusted for other research context in urban superdiversity research. Following this concept, a general superdiversity index could be built on the basis of detailed urban data, which are currently rather rare yet available in some cities.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (27.9 KB)Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to thank Professor Steven Vertovec, Professor Sara Carter, Professor Sarah Dodd, and Dr Jonathan Scott for their insightful comments and constructive feedbacks on previous versions of this paper. We also appreciate the intriguing discussions with colleagues from the Entrepreneurship and Minority Groups track at the Institute for Small Business and Entrepreneurship (ISBE) Conference in 2017 and their encouragement through the best paper award.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Paul Lassalle http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6063-8207

Notes

1 To capture the complexity of new migration patterns in contemporary societies through the consideration of the dynamic interaction of different attributes, such as migration status, occupation, gender, age or spatial distribution (Vertovec Citation2019).

2 It must be noted that tremendous care is needed when using available migration statistics. Depending on the country, data are collected on the basis of the country of birth (foreign-born vs native), on citizenship or also migration background irrespective of naturalization or citizenship at birth. Also, categories of ethnic diversity may base on self-indicated ethnic/racial identities. Harmonization difficulties are thus undeniable (Lemaitre et al. Citation2007, OECD), yet this complexity also aligns with the original idea of migrant superdiversity (Vertovec Citation2007).

3 Statistically the available data refers to the residential population which may differ from the client base as businesses do show larger catchment areas than their actual location. However, ethnic minority businesses have been observed to show strong tendencies especially initially in focusing on the local ethnic niche market and only later to be venturing out so that the residential population can be regarded a reasonable approximation to the EME issue.

4 Deprived neighbourhoods are defined by the cut off at 10% of the most disadvantaged.

5 The focus on main or ‘high streets’ in ethnographic assessments of superdiversity is also found in Hall's seminal works on trans-ethnographic study; see also Hall and Datta (Citation2010, 70) on the significance of the urban high streets within the scale of the neighbourhood as the empirical context studied.

6 The Index is the sum of the normalised individual indicators, following existing methodologies (OECD Citation2008; UNDP Citation2016).

References

- Amin, Ash. 2002. “Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 34 (6): 959–980.

- Barrett, Giles A., Trevor P. Jones, and David McEvoy. 1996. “Ethnic Minority Business: Theoretical Discourse in Britain and North America.” Urban Studies 33 (4-5): 783–809.

- Blommaert, Jan. 2013. Ethnography, Superdiversity and Linguistic Landscapes: Chronicles of Complexity. Vol. 18. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Buhr, Franz. 2018. “Using the City: Migrant Spatial Integration as Urban Practice.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (2): 307–320.

- Carter, Sara, Samuel Mwaura, Monder Ram, Kiran Trehan, and Trevor Jones. 2015. “Barriers to Ethnic Minority and Women’s Enterprise: Existing Evidence, Policy Tensions and Unsettled Questions.” International Small Business Journal 33 (1): 49–69.

- Deakins, David, David Smallbone, Mohammed Ishaq, Geoffrey Whittam, and Janette Wyper. 2009. “Minority Ethnic Enterprise in Scotland.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (2): 309–330.

- de Vries, Huibert Peter, Robert T. Hamilton, and Kevin Voges. 2015. “Antecedents of Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurship in New Zealand: An Intergroup Comparison.” Journal of Small Business Management 53 (1): 95–114.

- Duarte, Joana, and Ingrid Gogolin. 2013. Linguistic Superdiversity in Urban Areas: Research Approaches. Vol. 2. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

- Engelen, Ewald. 2001. “‘Breaking in’ and ‘Breaking Out’: A Weberian Approach to Entrepreneurial Opportunities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27 (2): 203–223.

- Fong, Eric, Elic Chan, and Xingshan Cao. 2013. “Moving Out and Staying in the Ethnic Economy.” International Migration 51 (1): 61–77.

- Gawlewicz, Anna. 2016. “Beyond Openness and Prejudice: The Consequences of Migrant Encounters with Difference.” Environment and Planning A 48 (2): 256–272.

- General Register Office for Scotland. 2010. Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Migration Report.

- Glasgow City Council. 2012. Population and Households by Ethnicity in Glasgow Estimates of Changes 2001-2010 for Community Planning Partnership areas and Neighbourhoods.

- Glick-Schiller, Nina, and Ayse Çağlar. 2009. “Towards a Comparative Theory of Locality in Migration Studies: Migrant Incorporation and City Scale.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (2): 177–202.

- Hall, Suzanne M. 2011. “High Street Adaptations: Ethnicity, Independent Retail Practices, and Localism in London’s Urban Margins.” Environment and Planning A 43 (11): 2571–2588.

- Hall, Suzanne M. 2015. “Super-Diverse Street: A ‘Trans-Ethnography’ Across Migrant Localities.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (1): 22–37.

- Hall, Suzanne, and Ayona Datta. 2010. “The Translocal Street: Shop Signs and Local Multi-Culture Along the Walworth Road, South London.” City, Culture and Society 1 (2): 69–77.

- Harries, Bethan, Bridget Byrne, James Rhodes, and Stephanie Wallace. 2018. “Diversity in Place: Narrations of Diversity in an Ethnically Mixed, Urban Area.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 1–18. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1480998?needAccess=true.

- Home Office. 2009. Accession Monitoring Report. London: UK Border Agency.

- Ishaq, Mohammed, Asifa Hussain, and Geoff Whittam. 2010. “Racism: A Barrier to Entry? Experiences of Small Ethnic Minority Retail Businesses.” International Small Business Journal 28 (4): 362–377.

- Jones, Trevor, Giles Barrett, and David McEvoy. 2000. “Market Potential as a Decisive Influence on the Performance of Ethnic Minority Business.” In Immigrant Businesses: The Economic, Political and Social Environment, edited by Jan Rath, 37–53. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jones, Trevor, Monder Ram, Paul Edwards, Alex Kiselinchev, and Lovemore Muchenje. 2014. “Mixed Embeddedness and new Migrant Enterprise in the UK.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (5-6): 500–520.

- Kelly, Briand, and Stephen Ashe. 2014. Local Dynamics of Diversity: Evidence from the 2011 Census. Manchester: Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity.

- Kemeny, Thomas. 2012. “Cultural Diversity, Institutions, and Urban Economic Performance.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 44 (9): 2134–2152.

- Kitching, John, David Smallbone, and Rosemary Athayde. 2009. “Ethnic Diasporas and Business Competitiveness: Minority-Owned Enterprises in London.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35 (4): 689–705.

- Kloosterman, Robert. 2010. “Matching Opportunities with Resources: A Framework for Analysing (Migrant) Entrepreneurship from a Mixed Embeddedness Perspective.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22 (1): 25–45.

- Kloosterman, Robert, and Jan Rath. 2001. “Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Advanced Economies: Mixed Embeddedness Further Explored.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 27 (2): 189–201.

- Kloosterman, Robert C., Katja Rusinovic, and David Yeboah. 2016. “Super-Diverse Migrants—Similar Trajectories? Ghanaian Entrepreneurship in the Netherlands Seen from a Mixed Embeddedness Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (6): 913–932.

- Krausova, Anna, and Carlos Vargas-Silva. 2013. “Scotland: Census Profile.” In Migration Observatory briefing, COMPAS, University of Oxford.

- Lassalle, Paul, and Andrew Johnston. 2018. “Where are the Spiders? Proximities and Access to the Entrepreneurial Ecosystem: The Case of Polish Migrant Entrepreneurs in Glasgow.” In Entrepreneurial Ecosystems: Place-Based Transformations and Transitions, edited by Allan O'Connor, Erik Stam, Fiona Sussan, and David Audretsch, 131–152. Cham: Springer.

- Lassalle, Paul, and Jonathan M. Scott. 2018. “Breaking-out? A Reconceptualisation of the Business Development Process Through Diversification: The Case of Polish New Migrant Entrepreneurs in Glasgow.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (15): 2524–2543.

- Lemaitre, Georges, Thomas Liebig, Cécile Thoreau, and Pauline Fron. 2007. Standardised Statistics on Immigrant Inflows - Results, Sources and Methods. Paris: OECD.

- Lever, John, and Paul Milbourne. 2014. “Migrant Workers and Migrant Entrepreneurs: Changing Established/Outsider Relations Across Society and Space?” Space and Polity 18 (3): 255–268.

- Maly, Ico. 2016. “Detecting Social Changes in Times of Superdiversity: An Ethnographic Linguistic Landscape Analysis of Ostend in Belgium.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (5): 703–723.

- McGhee, Derek, Sue Heath, and Paulina Trevena. 2013. “Post-Accession Polish Migrants—Their Experiences of Living in ‘Low-Demand’ Social Housing Areas in Glasgow.” Environment and Planning A 45 (2): 329–343.

- Meissner, Fran. 2018. “Legal Status Diversity: Regulating to Control and Everyday Contingencies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (2): 287–306.

- Meissner, Fran, and Steven Vertovec. 2015. “Comparing Super-Diversity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (4): 541–555.

- Mokrovich, Jason. 2011. “Social Work Area Demographics.” Edited by Glasgow City Council.

- Nathan, Max. 2016. “Ethnic Diversity and Business Performance: Which Firms? Which Cities?” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 48 (12): 2462–2483.

- OECD, Joint Research Centre-European Commission. 2008. Handbook on Constructing Composite Indicators: Methodology and User Guide. Paris: OECD publishing.

- Office of National Statistics. 2011. UK Census. https://www.ons.gov.uk/census/2011census.

- Ojo, Sanya, Sonny Nwankwo, and Ayantunji Gbadamosi. 2013. “African Diaspora Entrepreneurs: Navigating Entrepreneurial Spaces in ‘Home’ and ‘Host’ Countries.” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 14 (4): 289–299.

- Padilla, Beatriz, Joana Azevedo, and Antonia Olmos-Alcaraz. 2015. “Superdiversity and Conviviality: Exploring Frameworks for Doing Ethnography in Southern European Intercultural Cities.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (4): 621–635.

- Pécoud, Antoine. 2004. “Entrepreneurship and Identity: Cosmopolitanism and Cultural Competencies among German-Turkish Businesspeople in Berlin.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (1): 3–20.

- Phizacklea, Annie, and Monder Ram. 1996. “Being Your Own Boss: Ethnic Minority Entrepreneurs in Comparative Perspective.” Work, Employment and Society 10 (2): 319–339.

- Piekut, Aneta, Philip Rees, Gill Valentine, and Marek Kupiszewski. 2012. “Multidimensional Diversity in Two European Cities: Thinking Beyond Ethnicity.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 44 (12): 2988–3009.

- Piętka, Emilia. 2011. “Encountering Forms of Co-Ethnic Relations: Polish Community in Glasgow.” Studia Migracyjne-Przeglad Polonijny 1 (37): 129–151.

- Portes, Alejandro, Luis Eduardo Guarnizo, and William J. Haller. 2002. “Transnational Entrepreneurs: An Alternative Form of Immigrant Economic Adaptation.” American Sociological Review 67 (2): 278–298.

- Portes, Alejandro, and Julia Sensenbrenner. 1993. “Embeddedness and Immigration: Notes on the Social Determinants of Economic Action.” American Journal of Sociology 98 (6): 1320–1350.

- Ram, Monder, Trevor Jones, Paul Edwards, Alexander Kiselinchev, Lovemore Muchenje, and Kassa Woldesenbet. 2013. “Engaging with Super-Diversity: New Migrant Businesses and the Research–Policy Nexus.” International Small Business Journal 31 (4): 337–356.

- Rodríguez-Pose, Andrés, and Daniel Hardy. 2015. “Cultural Diversity and Entrepreneurship in England and Wales.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47 (2): 392–411.

- Rusinovic, Katja. 2006. Dynamic Entrepreneurship: First and Second-Generation Immigrant Entrepreneurs in Dutch Cities. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Ryan, Louise. 2018. “Differentiated Embedding: Polish Migrants in London Negotiating Belonging over Time.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (2): 233–251.

- Sepulveda, Leandro, Stephen Syrett, and Fergus Lyon. 2011. “Population Superdiversity and New Migrant Enterprise: The Case of London.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23 (7-8): 469–497.

- Smallbone, David, Marcello Bertotti, and Ignatius Ekanem. 2005. “Diversification in Ethnic Minority Business.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 12 (1): 41–56.

- Smallbone, David, John Kitching, and Rosemary Athayde. 2010. “Ethnic Diversity, Entrepreneurship and Competitiveness in a Global City.” International Small Business Journal 28 (2): 174–190.

- Stevenson, Blake. 2007. A8 Nationals in Glasgow. Glasgow: Glasgow City Council.

- Storti, Luca. 2014. “Being an Entrepreneur: Emergence and Structuring of Two Immigrant Entrepreneur Groups.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 26 (7-8): 521–545.

- Syrett, Stephen, and Leandro Sepulveda. 2011. “Realising the Diversity Dividend: Population Diversity and Urban Economic Development.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 43 (2): 487–504.

- UNDP. 2016. “The Human Development Report 2016.” In, 286. New York: United nation Development Programme.

- Vershinina, Natalia, Rowena Barrett, and Michael Meyer. 2011. “Forms of Capital, Intra-Ethnic Variation and Polish Entrepreneurs in Leicester.” Work, Employment and Society 25 (1): 101–117.

- Vershinina, Natalia, Peter Rodgers, Maura McAdam, and Eric Clinton. 2019. “Transnational Migrant Entrepreneurship, Gender and Family Business.” Global Networks 19 (2): 238–260.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2007. “Super-Diversity and Its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054.

- Vertovec, Steven. 2019. “Talking Around Super-Diversity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (1): 125–139.

- Waldinger, Roger. 1993. “The Ethnic Enclave Debate Revisited.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 17 (3): 444–452.

- Waldinger, Roger. 2005. “Networks and Niches: The Continuing Significance of Ethnic Connections.” In Ethnicity, Social Mobility, and Public Policy: Comparing the USA and UK, edited by Glenn Loury, Tariq Modood, and Steven Teles, 342–362. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wang, Catherine L., and Levent Altinay. 2012. “Social Embeddedness, Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Growth in Ethnic Minority Small Businesses in the UK.” International Small Business Journal 30 (1): 3–23.

- Wang, Lu, and Lucia Lo. 2007. “Immigrant Grocery-Shopping Behavior: Ethnic Identity versus Accessibility.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 39 (3): 684–699.

- Werbner, Pnina. 2001. “Metaphors of Spatiality and Networks in the Plural City: A Critique of the Ethnic Enclave Economy Debate.” Sociology 35 (3): 671–693.

- Wessendorf, Susanne. 2013. “Commonplace Diversity and the ‘Ethos of Mixing’: Perceptions of Difference in a London Neighbourhood.” Identities 20 (4): 407–422.

- Wessendorf, Susanne. 2018. “Pathways of Settlement among Pioneer Migrants in Super-Diverse London.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (2): 270–286.

- Zhou, Min. 2004. “Revisiting Ethnic Entrepreneurship: Convergencies, Controversies, and Conceptual Advancements1.” International Migration Review 38 (3): 1040–1074.

- Zhou, Min, and John R. Logan. 1989. “Returns on Human Capital in Ethic Enclaves: New York City’s Chinatown.” American Sociological Review 54 (5): 809–820.