ABSTRACT

Several studies have demonstrated a positive association between regular church attendance and turning out to vote in established democracies. This paper examines whether the relationship holds for Muslims who regularly attend religious services. Using an original dataset of Muslim-origin citizens in Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, I find that regular mosque attendance is indeed associated with higher likelihood to vote in national elections in Germany and the United Kingdom, while among Dutch Muslims turnout is positively associated with individual religiosity. I find evidence that the proposed association between regular mosque attendance and voting is mediated through the acquisition of relevant political information and stronger associational involvement. The paper provides an individual-level analysis complementing studies of country-level institutional particularities and group-level characteristics that are conducive to higher levels of turnout among Muslims. The findings dispel the myth that mosques are sites of civic alienation and self-segregation, but can, in fact, play the role of ‘schools of democracy’.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

The decision to show up at the polling station and vote on election day is regarded as a sign of successful civic integration and engagement of ethnic minorities. Electoral participation defies the trend of increasing political apathy among the general population in liberal democracies (Blais and Rubenson Citation2013). This is all the more important when citizens of minority background, often suspected of alienation in their beliefs from the liberal-democratic mainstream and practices of self-segregation from the political process, are the ones doing the participating. This paper explores the factors contributing to electoral turnout among members of an important ethnoreligious minority, Muslims with a right to vote in three West European democracies, and zeroes, in particular, into the association between attendance of religious services and electoral participation. Is attending the mosque regularly associated with indifference to one of the most important aspects of the democratic political process? Or does it confer the resources, cognitive skills and psychological dispositions that render electoral participation more likely – and if so, why?

The choice of Muslim faith as the basis of sample selection is justified, because Muslims have increasingly come under scrutiny by politicians and a number of public intellectuals for supposedly forming, as a group, an ‘enemy within’ liberal democracies (Cesari Citation2013, 6–10). More broadly, Muslim-majority democracies have been found to have lower turnout rates, when controlling for other relevant institutional and socio-economic variables (Stockemer and Khazaeli Citation2014). At the same time, sympathetic observers have noted that a thaw in relations between Muslim minorities and non-Muslim majorities is predicated upon a better understanding of how Muslim communities are organised and how legitimacy is generated among their members (see, for instance, March Citation2011).

Relatedly, the idea that Muslim faith has become, in West European countries, the basis of a ‘thick’ ethnic identity, in other words, that it is currently a salient source of grievances and basis of potential mobilisation, is gaining traction among sociologists and political scientists (Alba and Foner Citation2015). However, the hypothesis that being Muslim is associated with specific political opinions or distinct political behaviour (turnout, left-right placement, party choice) has been tested only sporadically across countries (see for instance, Dancygier Citation2017; Kranendonk, Vermeulen, and van Heelsum Citation2018). This paper contributes to this literature by looking at the most common form of political participation, electoral turnout.

I am interested here in individual-level characteristics, and in particular the influence of regular mosque attendance on individual voter turnout, among Muslim citizens with the right to vote in West European democracies. I aim to test the hypothesis that the relationship is positive, as has been argued for Muslim voters in non-European contexts (for the US, see Jamal Citation2005, for Australia, see Peucker and Ceylan Citation2017) and explore possible mechanisms behind the hypothesised relationship. Other recent individual-country studies in Europe have also advocated a positive association between religious attendance and various forms of political participation (including voting) and proposed several possible working mechanisms (Giugni, Michel, and Gianni Citation2014; Sobolewska et al. Citation2015; Oskooii and Dana Citation2018). These studies are heavily influenced by a more established literature on the effects of church attendance on electoral participation among Christians, particularly in the United States. Regular churchgoers have consistently been found to report higher individual turnout rates (see, for instance, Rosenstone and Hansen Citation1993; Gerber, Gruber, and Hungerman Citation2016 for a quasi-experimental design leading to similar conclusions). This empirical regularity rests on the side-benefits of religious attendance for political mobilisation. Those attending religious services are more likely to acquire, on average, resources and skills that can inter alia be applied to voting. For instance, they may be exposed to political information of interest to their religious communities, develop strong associational networks that facilitate mobilisation on election day, and develop a heightened sense of political efficacy through regular participation in congregational activities. Regular attendants of religious services are also likely to develop group consciousness, that is, they may increasingly self-identify as members of a distinct minority and vote to defend and promote the rights of their group.

The present article focuses on the determinants of turnout among Muslims with the right to vote in national elections in Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. All three are major countries of immigration with sizeable Muslim populations, estimated at around 6% of the general population and projected to reach higher levels over the next decades (Grim and Karim Citation2011). The data is drawn from a recently completed large comparative project (Finding a place for Islam in Europe – EURISLAM) which has disseminated comparable survey data on the opinions and behaviour of Muslims across West European democracies. I focus here on individual-level traits and their interaction with group-level characteristics and thus complement the work of others who consider the effect of contextual factors, such as country-level institutional and discursive opportunities facilitating Muslim participation (Cinalli and Giugni Citation2016).

Mosque attendance and turnout: mediating mechanisms

Voting is the most common political activity in democracies, the one that regularly grants legitimacy to candidates for government. It also leads to substantive gains for voters of minority ethnic and religious background: formal and informal political mobilisation are linked with better political and economic outcomes for minority populations (Maxwell Citation2012). Still, minorities are less likely to vote than majorities in most of Western Europe, including in the three countries studied here (Bird, Saalfeld, and Wüst Citation2011). Large inter-country and inter-group differences exist and a lot of the variation is explained by inequalities in socioeconomic status and level of education (Sandovici and Listhaug Citation2010). Beyond the standard individual-level, socio-economic explanations, scholars have increasingly focused on institutional characteristics within countries, strength of group organisation and relational (network) resources of minority individuals with a positive influence on the likelihood to vote on election day (Sobolewska et al. Citation2015; Cinalli and Giugni Citation2016; Pilati and Morales Citation2016). The present paper focuses on one such potential source of networks and resources, namely religious attendance.

Religious attendance can potentially increase the resources individuals of minority background possess. By resources I mean various types of material and immaterial capital likely to make voting less costly/more beneficial and help overcome structural disadvantages. First, mosques, like churches, provide organised opportunities and a regular meeting place for individuals to discuss and act upon communal affairs (Baggetta Citation2009). Exposure to political affairs of direct interest to the Muslim community can be particularly valuable for persuading mosque attendants to vote. Thus the first hypothesised link between mosque attendance and individual voter turnout is:

H1: Mosque attendance increases the amount of exposure to political issues affecting the Muslim community, leading to higher voter turnout.

H2: Mosque attendance increases overall associational involvement leading to higher voter turnout.

H3: Mosque attendance is conducive to positive feelings towards democracy, leading to a higher individual-voter turnout.

H4: Mosque attendance generates a politicized, group consciousness among Muslims, leading to higher individual voter turnout.

Data and operationalisation

The analysis rests on data from the project ‘Finding a place for Islam in Europe’ (EURISLAM), an EU Seventh-Framework project. One component of the project was a telephone survey designed to capture the characteristics and beliefs of people originating from Muslim-majority countries in the six largest West European destination countries (Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, France the Netherlands and the UK).Footnote1 Questionnaires distributed in all countries, with the exception of France, included a question item on participation in the last national/federal election. The Swiss questionnaire did not include a screening question on having the right to vote and Switzerland was excluded, along with France, from the analysis. Belgium was also not included, because of the compulsory and strictly enforced voting participation laws in that country, which result in unusually high turnout rates.

The three remaining countries (Germany, the Netherlands and the UK), besides being major destination points for Muslim immigrants, feature different policy frameworks for citizenship acquisition, recognition of cultural rights of ethnic groups and overall approach to migrant integration. Thus, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands historically enforced less strict criteria for immigrant access to citizenship compared to Germany (Howard Citation2009, Citation2012). The Netherlands demonstrated an early willingness to institutionalise ties with ethnic and religious groups as a means of achieving integration and a more recent turn towards assimilationism (Vasta Citation2007). UK policy prioritised anti-discrimination and equality of opportunities over outright cultural recognition of religious groups (Modood Citation2006). Germany, on the other hand, focused on labour market integration, while retaining a more restrictive (ethnic) model of citizenship acquisition and cultural integration (Schönwälder and Triadafilopoulos Citation2016). Based on such national differences and the different institutional incentives for the self-organisation of ethnic and religious minorities, the effect of religious attendance on turnout could be expected to vary across the three countries. At the same time, the existence of a positive effect of regular mosque attendance on the likelihood to vote, irrespective of country-level policy traditions, would provide convincing evidence for an individual-level effect across national contexts.

The EURISLAM survey ran in 2011 and the first quarter of 2012 and questionnaire modules included, among other inquiries into patterns of ‘interaction and cultural distance’, items on political opinions and behaviour. The sample frame was based on name-recognition (onomastic sampling; see Schnell et al. Citation2017 for a description of the method) to identify Muslims of Turkish, Moroccan, Pakistani and ex-Yugoslav origin, these groups representing large enough populations from which to draw a representative sample in all six countries (Tillie et al. Citation2013). The purpose of the multi-group sample was to allow for testing the moderating effects of group-level characteristics. The sample frame was then applied to a digital phone directory to be subsequently used for random selection of potential respondents. Group-based and country-based sampling were combined, in order to provide a framework of testing hypotheses of minority attitudes and behaviour at the appropriate levels of analysis.

presents the numbers of respondents (natives and from each Muslim ethnic group) screened for eligibility and successfully interviewed, as well as the response rates for each group. To account for the heterogeneity of Muslim populations, seven groups based on Muslim-majority countries of origin were initially identified by the EURISLAM team as historically, linguistically and culturally distinct sample targets. However, only Turks, Pakistanis, Moroccans and ex-Yugoslavs (Muslims from Bosnia, Kosovo and FYR of Macedonia) featured high enough numbers in all targeted countries to produce a large enough sample. Bangladeshis, Algerians and Tunisians are thus excluded from the following group-level analyses.

Table 1. Response rates by country of residence and origin.

The dependent variable of interest measures electoral participation by asking respondents whether they voted in the last national/federal elections. In order to avoid conflating those ineligible to vote and those who did not vote for other reasons, the questionnaire included a filter question on eligibility to participate in national elections. The main independent variable of interest, frequency of mosque attendance, is derived from the question item: ‘How often do you go to the mosque or other place of worship?’. This item is likely to evoke attendance to congregational Friday and daily prayers at the mosque or other places designed for communal worship, but should not be taken to exclude other social and religious activities taking place in these spaces (Westfall Citation2018). For clarity's sake, I have constructed a binary variable with value ‘1’ representing those who answered they attended services daily or weekly and ‘0’ standing for those who answered ‘rarely’ or ‘never’. Mosque attendance is, of course, one of several components of individual religiosity, for instance frequency of prayer or conspicuous display of religious symbols (see Cinalli and Giugni Citation2016). I focus here on mosque attendance, because, much like church attendance, and unlike individual ritual prayers (salah) that are considered a duty for every Muslim, it accrues relational/networking and organisational benefits. Still, the analysis of individual countries, in particular the Netherlands, calls for examining the confounding effect of individual religiosity, broadly defined, among respondents; in this case, I include daily frequency of prayer (see Table 4 and adjacent analysis).

In exploring the association between mosque attendance and turnout, the paper proposes testing different causal mechanisms identified in the literature on political behaviour of minorities and controlling for potentially important confounding variables. I recognise that a causal link cannot be definitively established with cross-sectional, non-experimental data. Yet in providing empirical evidence for positive and statistically significant associations across countries and exploring potential mechanisms is an important first step towards studying the link between Muslim religious attendance and electoral participation in European democracies. To test the mediating mechanisms of the effect of mosque attendance, I include models with variables standing for knowledge of the national Islam Council (H1 – exposure to political issues), non-political associational membership (H2 – overall associational involvement), opinion on democracy (H3 – attitudes towards democracy) and self-identification as Muslim (H4 – group consciousness).Footnote2 I have also included several control variables in the models that are deemed relevant in the well-established literature on electoral participation: age (in years), unemployment (whether the respondent has paid work for more than 12 hours a week), educational status (International Standard Classification of Education 5-point scale), whether the respondent was born in the host country or not (Coffé and Bolzendahl Citation2010; Sondheimer and Green Citation2010; Smets and van Ham Citation2013). I also include self-reported proficiency in the host-country language. Last but not least, mosque attendance in the three countries is very much a gendered experience, because congregational prayers at the mosque or other communal places of worship (the Friday or Jummah prayers) are considered a duty only for Muslim men. This makes Muslim women considerably less likely to report regular mosque attendance (only about 13% of female respondents in the three countries compared to 37% among men). For this reason gender was included as a control variable in the following analyses.

Operationalising associational involvement as a mediating mechanism for the ‘civic’ effect of mosque attendance on voting raises objections. Some scholars argue that those attending religious services are also likely to join other associations and vote, because they are ‘joiners’ more generally and thus likely to participate in various forms of public and civic life (van Ingen and van der Meer Citation2016). To account for that possibility I run a separate analysis with non-political associational involvement as the dependent variable. I also include the knowledge of the national Islam Council as an alternative indicator of political resources acquired through mosque attendance. Islam Councils are officially recognised interlocutors between Muslim communities and national governments. They aim to centralise and standardise the administration of issues that arise between European states and practitioners of the Islamic faith (for instance, religious education in school curricula, burial and praying practices) and to represent Muslim interests in a way that respects constitutional principles and dispels fears of radicalisation (Laurence Citation2012). These bodies are typically umbrella organisations for several hundreds of mosques (or federations of mosques) and feature elections or other selection procedures that familiarise mosque attendants with standard democratic processes. As they mediate on state-mosque relations, they are likely to increase political awareness of and interest for national politics among Muslims who attend mosque services.

In fact, representatives of Islam Councils often make direct pleas to the faithful to vote. For instance, the speaker of the Muslim Coordination Council (Koordinierungsrats der Muslime), formed in the context of the German Islamkonferenz, explicitly invited the 1,5 million Muslims in Germany with a right to vote to do so in 2017 and included a ‘Master sermon’ to be read out in several mosques before the election (Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung Citation2017). The Muslim Council of Britain (MCB) launched a ‘Muslim Vote 2010’ online platform to inform British Muslims about specific issues relating to the Muslim community and encourage them to vote in the general election.Footnote3 For this reason I take knowledge of the national Islam Council as a potential mediator between mosque attendance and participation in national elections. Finally, I run the models including country-level and ethnic-group-level fixed effects to account for any unobserved characteristics in countries or groups. Although not of primary focus here, the discursive and institutional opportunity structures for Muslims vary in the three countries (Cinalli and Giugni Citation2016). Sobolewska et al. (Citation2015) and Jamal (Citation2005) also argue that the political salience of religion differs across groups depending on their historical trajectories in the host country and their organisational characteristics. The following section presents the main findings of the pooled-sample analysis controling for country- and group-level effects. The section after the next presents the results of the mediation analysis for potential mechanisms.

Findings

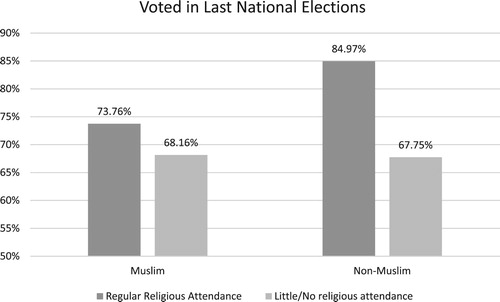

and Graph 1 provide descriptive statistics of electoral participation among Muslim respondents in Germany, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Turnout rates for Muslims with the right to vote were lower than the national average in all countries, the difference ranging from about 1.5% in the United Kingdom to about 5% in Germany. As Graph 1 demonstrates, regular religious attendance was associated with higher turnout rates both among Muslims and non-Muslims of the sample. A simple t-test operated for the two Muslim subgroups (high and low mosque attendance) shows that the difference in turnout is statistically significant at the 5% level, a first indication that mosque attendance is positively associated with showing up to vote on national election day.Footnote4 The difference in electoral participation between Muslims reporting high and low mosque attendance exists in all three countries, although it is only 2% in the Netherlands. More generally, the Netherlands features substantially higher turnout rates than the other two countries.

Graph 1. Electoral participation in last elections according to religious attendance (Muslims and Non-Muslims).

Table 2. Electoral participation in last elections of Muslims with right to vote (percentages across countries).

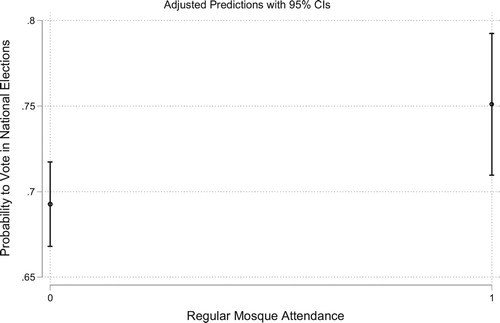

I now turn to the main analysis, fitting models to the data in order to account for electoral participation in the last national/federal elections among Muslim respondents. Since the dependent variable (turnout) is binary, the results of simple logistic regressions with different specifications are presented. displays the results (odds ratios) for the pooled 3-country sample. The variable of interest, regular mosque attendance, is, as hypothesised, positively and significantly associated with turnout in national elections (Model 1). The marginal effect is moderately strong, when controlling for other variables at their means – a little more than 5% higher probability to vote (Graph 2). The predicted effect is approximately as strong as being employed for more than 12 hours a week or adding 10 years of age or being fluent in host-country language, the other three variables of statistical significance at the 5% level.

Graph 2. Predicted probabilities of voting in national elections for varying mosque attendance (Model 3.1).

Table 3. Effect of mosque attendance on electoral participation of Muslims (odds ratios).

Results presented in Model 2 reveal that the effect of the attendance of religious services is moderated when controlling for group rather than country characteristics.Footnote5 Yugoslav Muslims are consistently found to be less likely to vote and provide the strongest evidence for the (here: negative) effect of national group origin. This may be linked to the fact that the members of this group are the most recent arrivals compared to the rest of the sample. Those Yugoslav Muslims who have the right to vote have practiced it for a short time, in addition to experiencing a long period of legal and socio-economic uncertainty, while the organisation in ethnic and religious networks is also relatively recent dating from the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s (Behloul Citation2011; Paul Citation2016).

On the other hand, Muslim respondents of Moroccan origin report the highest turnout rates, a finding that is surprising given the scholarly consensus on lower levels of Morroccan organisation and mobilisation (Kranendonk and Vermeulen Citation2018), and might reflect a longer-term integration process of these populations. Less surprisingly, Turkish Muslims also report higher than average turnout rates. Turkish mosques abroad enjoy organisational cohesion and resources through the Interior Ministry's Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet). For example in 2014, the German (Turkish Islamic Union for Religious Affairs – DITIB) and Dutch (Turkish Islamic Cultural Federation in the Netherlands -TICF) branches of Diyanet organised about 900 and 140 mosques respectively, more than half of the overall number of Turkish mosques and a much larger number than any other Muslim religious organisation in these two countries (Nielsen and Otterbeck Citation2015, 34, 55). Tight organisation of mosques by the Turkish government often involves appointing imams directly for a few years and using them as a means of indirect foreign policy. It also means that exhortations to vote in host-country elections are likely to reach large audiences and in a consistent manner. Diyanet imams have consistently advocated deeper political integration of Turkish immigrants and their descendants (including voting), because it increases the visibility and provides a springboard for representing Turkish interests in the host country (Warner and Wenner Citation2006, 466). For instance, the head of the German DITIB Izzet Er issued a press release before the 2013 Bundestag elections, in which he stressed that ‘Voting is a citizen's duty. One should absolutely make use of this democratic right’ (cited in Gorzewski Citation2015, 170).

Pakistanis are also considered a well-organised religious community, simultaneously combining high levels of identification with Islam and with their host countries, especially in the UK (Jacobson Citation2006, 32, 34). They were the first South Asian communities to become politically mobilised during the Salman Rushdie Affair, but also in response to the Kashmir conflict and other cases where Muslims around the world were perceived to be targeted (Gulf War, Israel-Palestine conflict). In fact, Pakistani diasporic communities have been at the forefront of the politicisation of Islam (Werbner Citation2005, 480–483) and would thus be expected to exert pressure on their members to become politically active. In Britain, the country where the Pakistani community is the most numerous, they have provided leadership for the national Muslim Council. At the same time, Pakistani diaspora mosques have also suffered from sectarian fragmentation (Werbner Citation2005, 481–482) and do not enjoy the organisational grip of a foreign government that characterises Turkish mosques.

The pooled-sample analysis yields a strong and significant country-level effect on turnout for the Netherlands compared to the UK and Germany. In order to account for this empirical outlier, I ran separate country-level analyses for all countries (). The effect of mosque attendance on turnout is found to be stronger for the country-level UK and Germany analyses, albeit weakly significant as the number of observations decreases substantially. The effect disappears in the analysis specific to the Netherlands. What accounts for the Dutch exceptionalism? Interestingly, among Dutch-Muslim respondents there is a strong and statistically significant positive association between regular prayer and voting in the national elections (Model 4). Alternative specifications, including running models with group-level effects and other mediating mechanisms do not alter the strong effect of regular prayer on the likelihood to vote in the Netherlands. I do not find a similar positive link between regular prayer and voting in Germany and the UK – in both countries the positive association between mosque attendance and voting is positive, strong and robust in alternative specifications, including regular prayer.Footnote6 It seems then that religiosity is a better predictor of turnout on election day than mosque attendance among Dutch Muslims. Given this result, more research is needed to gauge the effect of the Dutch national integration model on the accommodation of Islam, in particular with regard to how institutional and discursive opportunities lead to increased political participation among devout Muslims. The very public debates in the Netherlands about the role of Islam in public life since the assassinations of controversial Islam critics Theo Van Gogh and Pim Fortuyn are likely to have increased the group consciousness of religious Muslims and induced them to participate in national politics. At the same time, the earlier recognition and inclusion of ethnic and religious associations in the Netherlands (Vasta Citation2007) means that devout Dutch Muslims can rely on a wealth of resources for mobilisation (minority schools, associations, ethnic networks), other than the mosques.

Table 4. Effect of mosque attendance on electoral participation of Muslims BY COUNTRY (odds ratios).

Mediating mechanisms

Finally, displays the results of the multivariable logistic regression models that include the variables chosen to operationalise the potential mediating mechanisms. Direct and indirect resources in the form of associational involvement and knowledge of the national Islam Council are found to be strong and statistically significant predictors of electoral participation; they also decrease the effect size of mosque attendance (Models 1–2). One can tentatively conclude that informational and network resources accumulated through mosque attendance are indeed an important contributing factor to individual electoral participation. Self-perception as a Muslim is more strongly correlated with mosque attendance and thus decreases its effect on turnout more substantially, but is itself not as significant a predictor of individual turnout as associational activity and increased exposure to political issues (Model 3). Thus I find weaker evidence for a ‘group consciousness’ mechanism for mosque attendance; to bolster this conclusion I have run an alternative model substituting perception of discrimination against Muslims (a commonly used operator for ‘group consciousness’) for self-perception as Muslim. This question was unfortunately not available in the Dutch questionnaire, but when running the models for Germany and the UK (not shown here) the effect of mosque attendance remained unchanged and statistically significant and perception of discrimination was statistically insignificant. Lastly, there is no evidence that overall attitudes towards democracy have a positive or negative effect on turnout (Model 4).Footnote7

Table 5. Effect of mosque attendance and possible mediator variables on electoral participation of Muslims (odds ratios).

To be sure, associational involvement might not reflect the positive influence of religious attendance on a Muslim's participation in community life and broader networks, but might be the result of a confounding variable, for instance the respondent's overall, pre-existing civic-mindedness that makes them more likely to join an association and to attend congregational prayers. In order to preclude the possibility of such omitted variable bias, I have run a multivariable regression analysis on reporting being a member of an association. presents the results; the relationship between regular mosque attendance and joining an association is positive and statistically significant even after controlling for standard socio-economic indicators (such as level of education and employment status) and, importantly, for positive attitudes towards democracy that would indicate higher levels of civic- mindedness. The results do not change when including country and group fixed-effects (not shown here).

Table 6. Effect of mosque attendance on associational membership (odds ratios).

In a similar vein, a separate analysis of the factors associated with knowledge of the national Islam Council was run, in order to preclude for the possibility that reporting high levels of politically valuable resources is the effect of individual characteristics other than mosque attendance. The results are presented in . They show a very strong and statistically significant positive association between attending the mosque regularly and reporting knowledge of the national Islam Council, but no link of such knowledge with education level, associational membership or religiosity measured by frequency of prayer. The analysis here, in conjunction with the analysis presented at , points at a distinct mechanism for the effect of attending a mosque on electoral participation: regular mosque-goers are more likely to acquire political information that is pertinent to the Muslim community, making them more likely to participate in the political process. This may happen through direct canvassing in mosques or an indirect increase of perceived political efficacy – the exact mechanism can unfortunately be tested using the available EURISLAM data – but it seems to be independent from whether the respondent is, generally speaking, someone interested in civic life or religious matters. The analysis also demonstrates that Turkish respondents are more likely to have knowledge of the national Islam Council, a finding underlying the strong participation of the representatives of the Turkish community in these bodies. The German Islamkonferenz is also better-known than its UK and Dutch equivalents perhaps suggesting higher levels of consolidation and representativity of this body in Germany or better media coverage.

Table 7. Effect of mosque attendance on knowledge of national Islam Council (odds ratios).

Conclusion

This article set out to investigate the link between regular religious attendance among Muslims with the right to vote in three West European democracies and voting in (national) elections. The evidence drawn from an original dataset of citizens of Muslim background suggests that attending the mosque does not lead to political alienation. In no model and under no specification was there a negative association between regular mosque attendance and individual turnout. In fact, regular mosque attendance was mostly found to be positively associated with this most common form of political participation in consolidated democracies. This empirical finding, well-established for church-attending Christians and Muslims in the United States (Jamal Citation2005), seems to be confirmed in the case of West European Muslims as well, most significantly for Muslims in the UK and Germany. Of the possible mechanisms that mediate between regular mosque attendance and individual turnout, evidence is strongest for the exposure to political issues relevant for the Muslim community (such as knowledge of the national Islam Council) and an increase in overall associational involvement that indirectly makes a mosque attendant more likely to vote. One can thus interpret mosque attendance as a religious source of political and social capital that can be invested in electoral participation and can partly compensate for structural disadvantages of minority individuals. Unlike Sobolewska et al. (Citation2015) I do not find evidence for mediation through increased psychological resources, such as heightened group consciousness or an individual's higher trust in democratic politics.

The findings presented here do not imply that country-level or group-level dynamics are not important. To be sure, private religiosity in the Netherlands is more robustly associated with voting than attending the mosque, while some groups among Muslims (notably Yugoslavs) report lower levels of participation, while others (notably Moroccans and Pakistanis) vote almost as often as native respondents, with differences between these groups not disappearing when controlling for mosque attendance. Such findings should caution against hasty generalisations of a mosque-attendance effect on electoral participation in other countries or groups. Relatedly, one of the limitations of the present study is the inability to test for the ethnic composition of the mosque attended by the respondent as a potential mediating mechanism between mosque attendance and electoral participation. The argument, developed most prominently by Jones-Correa and Leal (Citation2001) in the study of Latino Churches in the United States and tested for places of worship in Britain by Sobolewska et al. (Citation2015), posits that ethnic homogeneity in the place of worship makes the politicisation of ethno-religious identities more likely, increasing electoral and non-electoral participation. Therefore, mosques act as repositories of ethnic social capital, which is itself associated with higher political participation (Jacobs and Tillie Citation2004). Although the brief discussion of group-level effects above suggests that most Muslims sampled are likely to attend ethnically homogeneous mosques, the EURISLAM questionnaire does not include a specific question item on the ethnic make-up of their places of worship.

In future studies, the research design can also be extended to non-electoral participation; as well as the interaction between party identity and mosque attendance. The tendency of Muslim voters to identify with and vote for left-wing parties is documented in the American literature (see Barreto and Bozonelos Citation2009). It is not simply the foundational democratic procedures, such as elections, that devout Muslims might be induced to endorse, but also specific parties, in particular left-wing and center-left parties (Dancygier Citation2017). Through support for and strong identification with such parties, minority political alienation decreases and the entire democratic process benefits. There exists little evidence for this link in European democracies as well, as whether it is solidified in religious congregations. Future international, comparative studies would also benefit from more standardised and precise survey items on the nature and sources of civic skills (political information, communication skills, political trust) acquired by Muslim-origin individuals in European democracies.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Michalis Moutselos http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8454-1124

Notes

1 EURISLAM Survey – Dataset and codebook, accessed 20 March 2018 at https://easy.dans.knaw.nl/ui/datasets/id/easy-dataset:62447/tab/2

2 Associational membership: ‘Do you join any associations such as sports clubs, religious organisations, labour unions, parents associations, etc. in, where you meet other people?’. Knowledge of the national Islam Council: ‘Are you aware of Deutsche Islam Konferenz (Germany)/Mosques and Imams National Advisory Board (the UK)/ Contactorgaan Moslims en Overheid or the Contactgroep Islam? (the Netherlands)’. Opinion on Democracy: ‘Could you please tell me if you agree strongly, agree, disagree or disagree strongly: Democracy may have problems, but it's better than any other form of government’. Self-definition as Muslim: ‘To what extent do you see yourself as Muslim?’

3 ‘Muslim Vote 2010’ accessed 5 November 2019 at http://archive.mcb.org.uk/muslim-vote-2010/

4 The t-test result is significant at the 5% level for the pooled sample and for any 2-country combination. For the individual-country samples, it is only significant at the 10% level for the UK.

5 Tables 3 and 4 of the Online Appendix present results including both country-fixed effects and group-fixed effects, along with the variables from the analysis for Tables 3 and 5. The size of the hypothesised effect of regular mosque attendance on voting remains substantial, but the predicted coefficient loses statistical significance because of the reduced power of the models.

6 See Online Appendix, Table 5.

7 In order to control for the possibility that the coefficient for mosque attendance decreases due to the presence of non-respondents, I have run each model in Table 5 without the mediating variables and excluding non-respondents corresponding to each mediating variable. The coefficient size and significance for mosque attendance did not change compared to the full-sample analysis.

References

- Alba, Richard, and Nancy Foner. 2015. Strangers No More: Immigration and the Challenges of Integration in North America and Western Europe. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Baggetta, Matthew. 2009. “Civic Opportunities in Associations: Interpersonal Interaction, Governance Experience and Institutional Relationships.” Social Forces 88 (1): 175–199.

- Barreto, Matt A., and Dino N. Bozonelos. 2009. “Democrat, Republican, or None of the Above? The Role of Religiosity in Muslim American Party Identification.” Politics and Religion 2 (2): 200–229.

- Behloul, Samuel M. 2011. “‘Religion or Culture?: The Public Relations and Self-Presentation Strategies of Bosnian Muslims in Switzerland Compared with other Muslims.” In The Bosnian Diaspora: Integration in Transnational Communities, edited by Marko Valenta and Sabrina P. Ramet, 301–318. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

- Betz, Hans-Georg, and Susi Meret. 2009. “Revisiting Lepanto: The Political Mobilization against Islam in Contemporary Western Europe.” Patterns of Prejudice 43 (3–4): 313–334.

- Bird, Karen, Thomas Saalfeld, and Andreas M. Wüst, eds. 2011. The Political Representation of Immigrants and Minorities: Voters, Parties and Parliaments in Liberal Democracies. Oxford: Routledge.

- Blais, André, and Daniel Rubenson. 2013. “The Source of Turnout Decline: New Values or New Contexts?” Comparative Political Studies 46 (1): 95–117.

- Cesari, Jocelyne. 2004. When Islam and Democracy Meet: Muslims in Europe and in the United States. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cesari, Jocelyne. 2013. Why the West Fears Islam: An Exploration of Muslims in Liberal Democracies. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cinalli, Manlio, and Marco Giugni. 2016. “Electoral Participation of Muslims in Europe: Assessing the Impact of Institutional and Discursive Opportunities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (2): 309–324.

- Coffé, Hilde, and Catherine Bolzendahl. 2010. “Same Game, Different Rules? Gender Differences in Political Participation.” Sex Roles 62 (5–6): 318–333.

- Dancygier, Rafaela M. 2017. Dilemmas of Inclusion: Muslims in European Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Dawson, Michael C. 1995. Behind the Mule: Race and Class in African-American Politics. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Djupe, Paul A., and Christopher P. Gilbert. 2006. “The Resourceful Believer: Generating Civic Skills in Church.” The Journal of Politics 68 (1): 116–127.

- Driskell, Robyn, Elizabeth Embry, and Larry Lyon. 2008. “Faith and Politics: The Influence of Religious Beliefs on Political Participation.” Social Science Quarterly 89 (2): 294–314.

- Gerber, Alan S., Jonathan Gruber, and Daniel M. Hungerman. 2016. “Does Church Attendance Cause People to Vote? Using Blue Laws’ Repeal to Estimate the Effect of Religiosity on Voter Turnout.” British Journal of Political Science 46 (3): 481–500.

- Giugni, Marco, Noémi Michel, and Matteo Gianni. 2014. “Associational Involvement, Social Capital and the Political Participation of Ethno-Religious Minorities: The Case of Muslims in Switzerland.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (10): 1593–1613.

- Gorzewski, Andreas. 2015. “Anbieten und Einfordern–Die DİTİB in Politik und Zivilgesellschaft.” In Die Türkisch-Islamische Union im Wandel, 129–173. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Grim, Brian J., and Mehtab S. Karim. 2011. The Future of the Global Muslim Population: Projections for 2010–2030. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

- Howard, Marc Morjé. 2009. The Politics of Citizenship in Europe. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Howard, Marc Morjé. 2012. “Germany’s Citizenship Policy in Comparative Perspective.” German Politics and Society 30 (1): 39–51.

- Jacobs, Dirk, and Jean Tillie. 2004. “Introduction: Social Capital and Political Integration of Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 30 (3): 419–427.

- Jacobson, Jessica. 2006. Islam in Transition: Religion and Identity among British Pakistani Youth. London: Routledge.

- Jamal, Amaney. 2005. “The Political Participation and Engagement of Muslim Americans: Mosque Involvement and Group Consciousness.” American Politics Research 33 (4): 521–544.

- Jones-Correa, Michael A., and David L. Leal. 2001. “Political Participation: Does Religion Matter?” Political Research Quarterly 54 (4): 751–770.

- Kranendonk, Maria, and Floris Vermeulen. 2018. “Group Identity, Group Networks, and Political Participation: Moroccan and Turkish Immigrants in the Netherlands.” Acta Politica. Advance online publication. doi:10.1057/s41269-018-0094-0.

- Kranendonk, Maria, Floris Vermeulen, and Anja van Heelsum. 2018. “‘Unpacking’ the Identity-to-Politics Link: The Effects of Social Identification on Voting Among Muslim Immigrants in Western Europe.” Political Psychology 39 (1): 43–67.

- Laurence, Jonathan. 2012. The Emancipation of Europe’s Muslims: The State’s Role in Minority Integration. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Lee, Taeku. 2008. “Race, Immigration, and the Identity-to-Politics Link.” Annual Review of Political Science 11: 457–478.

- March, Andrew F. 2011. Islam and Liberal Citizenship: The Search for an Overlapping Consensus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maxwell, Rahsaan. 2012. Ethnic Minority Migrants in Britain and France: Integration Trade-Offs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Modood, Tariq. 2006. “British Muslims and the Politics of Multiculturalism.” In Multiculturalism, Muslims and Citizenship: A European Approach, edited by Tariq Modood, Anna Triandafyllidou, and Ricard Zapata-Barrero, 48–67. Oxford: Routledge.

- Neue Osnabrücker Zeitung. 2017. “Koordinierungsrat ruft Muslime in Deutschland zur Teilnahme an Bundestagswahl auf.” September 22.

- Nielsen, Jorgen, and Jonas Otterbeck. 2015. Muslims in Western Europe. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Oskooii, Kassra A. R. 2016. “How Discrimination Impacts Sociopolitical Behavior: A Multidimensional Perspective.” Political Psychology 37 (5): 613–640.

- Oskooii, Kassra A. R., and Karam Dana. 2018. “Muslims in Great Britain: The Impact of Mosque Attendance on Political Behaviour and Civic Engagement.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (9): 1479–1505.

- Paul, J. 2016. Bosnian Organizations in Germany: Orientations and Activities in Transnational Social Spaces. COMCAD Working Papers, 149. Bielefeld: Universität Bielefeld, Fak. für Soziologie, Centre on Migration, Citizenship and Development (COMCAD).

- Peucker, Mario, and Rauf Ceylan. 2017. “Muslim Community Organizations – Sites of Active Citizenship or Self-Segregation?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (14): 2405–2425.

- Phalet, Karen, Gülseli Baysu, and Maykel Verkuyten. 2010. “Political Mobilization of Dutch Muslims: Religious Identity Salience, Goal Framing, and Normative Constraints.” Journal of Social Issues 66 (4): 759–779.

- Pilati, Katia, and Laura Morales. 2016. “Ethnic and Immigrant Politics vs. Mainstream Politics: The Role of Ethnic Organizations in Shaping the Political Participation of Immigrant-Origin Individuals in Europe.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (15): 2796–2817.

- Rosenstone, Steven J., and John Hansen. 1993. Mobilization, Participation, and Democracy in America. New York: Macmillan.

- Sandovici, Maria Elena, and Ola Listhaug. 2010. “Ethnic and Linguistic Minorities and Political Participation in Europe.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 51 (1-2): 111–136.

- Schnell, Rainer, Tobias Gramlich, Tobias Bachteler, Mark Trappmann, Menno Smid, and Inna Becher. 2017. “A New Name-Based Sampling Method for Migrants.” Methods, Data, Analyses 7 (1): 29.

- Schönwälder, Karen, and Triadafilos Triadafilopoulos. 2016. “The New Differentialism: Responses to Immigrant Diversity in Germany.” German Politics 25 (3): 366–380.

- Smets, Kaat, and Carolien van Ham. 2013. “The Embarrassment of Riches? A Meta-Analysis of Individual-Level Research on Voter Turnout.” Electoral Studies 32 (2): 344–359.

- Sobolewska, Maria, Stephen Fisher, Anthony F. Heath, and David Sanders. 2015. “Understanding the Effects of Religious Attendance on Political Participation among Ethnic Minorities of Different Religions.” European Journal of Political Research 54 (2): 271–287.

- Sondheimer, Rachel Milstein, and Donald P. Green. 2010. “Using Experiments to Estimate the Effects of Education on Voter Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 54 (1): 174–189.

- Stockemer, Daniel, and Susan Khazaeli. 2014. “Electoral Turnout in Muslim-Majority States: A Macro-Level Panel Analysis.” Politics and Religion 7 (1): 79–99.

- Tillie, Jean, Maarten Koomen, Anja van Heelsum, and Alyt Damstra. 2013. Finding a Place for Islam in Europe. Cultural Interactions between Muslim Immigrants and Receiving Societies. Final integrated report. Brussels: EURISLAM.

- van Ingen, Erik, and Tom van der Meer. 2016. “Schools or Pools of Democracy? A Longitudinal Test of the Relation Between Civic Participation and Political Socialization.” Political Behavior 38 (1): 83–103.

- Vasta, Ellie. 2007. “From Ethnic Minorities to Ethnic Majority Policy: Multiculturalism and the Shift to Assimilationism in the Netherlands.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (5): 713–740.

- Verba, Sidney, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambrudge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Warner, Carolyn M., and Manfred W. Wenner. 2006. “Religion and the Political Organization of Muslims in Europe.” Perspectives on Politics 4 (3): 457–479.

- Werbner, Pnina. 2005. “Pakistani Migration and Diaspora Religious Politics in a Global Age.” In Encyclopedia of Diasporas, 475–484. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Westfall, Aubrey. 2018. “Mosque Involvement and Political Engagement in the United States.” Politics and Religion. Advance online publication. doi:10.1017/S1755048318000275.