Abstract

Human capital has been long an exceedingly important concept in migration research. Over time there have been attempts to provide more nuanced, and less economistic interpretations of human capital. Based on outputs from the EU Horizon 2020 project YMOBILITY (2015–2018) and two additional papers, this Special Issue seeks to advance this agenda further by addressing the complexities of the mobility of human capital. Migration problematises human capital assumptions due to challenges in transferring human capital across national borders. In this introductory paper we propose rethinking the human capital of migrants in a three-fold way. Firstly, we question the interpretation of skills and competences beyond the conventional divide of ‘higher-skilled’ and ‘lower-skilled’ through the concept of a ‘knowledgeable migrant’. Secondly, we probe deeper into an understanding of the transferability of skills in relation to ‘location’, exploring the possibilities and constraints to the transfer of human capital in different spatial contexts. Thirdly, we theorise human capital in terms of new temporalities of migration and the role these play in skill acquisition. We illustrate our novel theoretical thinking with selected empirical data, both quantitative and qualitative, on youth mobility in Europe.

Introduction

At the outset of the 2004 European Union (EU) Enlargement, Baláž, Williams, and Kollar (Citation2004, 5) posed a fundamental question about the future ‘brain redistribution’ challenges for the then EU’s accession countries: ‘Who will migrate, what human capital will be lost or gained, and will this be temporary or permanent?’ Since then, some economies have experienced a large influx of migrants from Eastern Europe, as a consequence of the EU enlargements in 2004 and 2007, followed also by young Greeks, Spaniards, Portuguese and Italians, driven by the 2008 economic crisis. Some of the vital questions probed by Baláž et al. can be now addressed, more than a decade later. However, the responses remain complex. Engaging with the first question (who will migrate), in this Special Issue, we specifically address youth mobilities. But in terms of questions of human capital gain and losses, we need to open up inquiries into migrants’ individual experiences, the multi-directional flows migrants are engaged in, country-specific as well as changing EU regulatory regimes, and their temporalities.

We approach human capital as an inherently complex phenomenon. Our overarching contribution is to enrich our understanding of human capital dynamics as constituting more than an economic domain, including how human capital can or cannot be linked to other forms of capital. For instance, linking human capital (with its emphasis on success in the labour market) to Bourdieu’s (Citation1984) explanations of cultural capital (with an emphasis on education and language) or to social, economic and symbolic capitals requires careful theoretical thinking that sheds light on the underlying foundations of gains/losses and structural constraints which are either EU-wide, global or country-specific, as well as individual-level experiences. Dustmann (Citation1999), for instance, provides a synthesised view on language skills and communication as a distinct form of ‘language capital’. All these capitals are evolving through migration and they may form a distinctive ‘migration capital’ (Brickell and Datta Citation2011) where other capitals are amplified or constrained due to the nature of migration experiences. Migration scholars have also learned insights into the complexity of human capital from other fields, most notably management studies. Literatures on ‘learning careers’ (e.g. Salt Citation1988) have developed along with studies which employ the concepts of ‘brain waste’, ‘brain drain’, ‘brain gain’, ‘brain exchange’, ‘brain circulation’ or ‘brain training’. In sum, we contend that in any critical inquiry into employability, skills and competences in a migration context, human capital should not be isolated from other forms of capital: social, cultural and financial (King and Williams Citation2018; Marginson Citation2017; Scholten and Van Ostaijen Citation2018; Williams and Baláž Citation2005). This Special Issue builds further on this critique. The following text begins with an account on youth migration and mobility trends in Europe and a conceptual outline. Then we provide a three-fold theoretical and empirical agenda on new trends in human capital research: knowledge, spatialities and temporalities. All contributions in the Special Issue focus on young migrants as they comprise the largest flows in intra-EU mobility. Drawing on the YMOBILITY survey methodology, we define young migrants as those aged 16–35years (for the questionnaire survey) and 18–35 (at the time of first migration for the interviews), allowing to capture key life transitions from ‘youth’ to ‘full adulthood’ (see King and Williams Citation2018). We conclude with an overview of the contributions to this Special Issue and propose avenues for future research.

Human capital and mobility trends in Europe

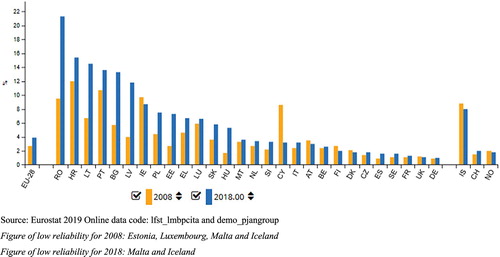

The EU enlargements of 2004 and 2007 dramatically changed international mobility patterns, creating what Favell (Citation2008) called ‘a new migration system in Europe’. By 2013 half of all intra-EU migrants were from the new member states, although these countries account for only 21% of the total EU population (Castro-Martín and Cortina Citation2015). Eurostat (Citation2019a) data from 2018 show that Romanians are the nationality that utilises free mobility rights the most (see ). Romanian citizens of working age (20–64) residing abroad within the EU accounted for about a fifth (21.3%) of the population in Romania. Other countries with a large share of their nationals in other EU member states are Lithuanians (14.5%), Croats (14.0%), Portuguese (13.6%), Bulgarians (13.3%) and Latvians (11.8) (Eurostat Citation2019a). In all this, caveats must be added that the available data may not capture some mobile groups.

Figure 1. EU mobile citizens of working age (20–64) by country of citizenship, % of their home-country resident population. Source: Eurostat Citation2019a Online data code: lfst_lmbpcita and demo_pjangroup.

A recent development shows an increase in return mobility; in 2016, 680,000 European nationals returned to their country of origin (Fries-Tersch et al. Citation2018). Available data on temporary mobility and return movements are, however, sparse.

Secondary data confirm that education levels also shape mobility patterns. Tertiary level graduates are generally more mobile than the rest of the population, and this is especially the case for countries that were part of the European Union before the 2004 accession (Eurostat Citation2019a). Migrants with a lower-secondary education are also overrepresented in the mobile population. Here we find big differences between the old and new member states. For Poles, Lithuanians, Latvians, Romanians, Czechs, Estonians and Bulgarians, there is a substantial overrepresentation of lower-skilled intra-EU mobility compared to their native populations. However, the reality is more complicated than a simple division of people according to formal skills. When migrants cannot access jobs where they could put their skills in use due to structural constraints, brain circulation and training remain a great challenge in European intra-mobility realities.

Besides, migration intentions among young people have been high in recent years. A Eurobarometer (2013) survey found that young age is a key indicator of potential future mobility. More than half of the respondents aged between 15 and 24 would consider working in another member state (56%), compared to 36% in the age group 25–39, 23% in age group 40–54 and 5% of those older than 55 years. Intentions to migrate among European youth remain high (Williams et al. Citation2018). Specifically, 30% of survey respondents across the nine countries studied in the YMOBILITY project were found very likely to migrate; with many having already made concrete plans towards their international move. Young people from Romania (41%), Italy (39%) and Spain (35%) showed the biggest desire to migrate within the next five years.

Youth mobility has the potential to partly address some of the large differences in youth unemployment between the member states. Unemployment, reaching above 20%, was an important push factor for young people to migrate from Poland to the UK following the EU 2004 Accession (White Citation2010). In 2017, long-term unemployment for the 15–29 age category varied from 22% in Greece, 14% in Italy and 9% in Spain to less than 2% in countries such as Germany, Denmark, Sweden and Netherlands (Eurostat Citation2019b). Insufficient language skills and non-recognition of formal qualifications are seen as two of the most important barriers for mobility between member states (Fries-Tersch et al. Citation2018). The question of the transferability of human capital is thus a central aspect for the future of intra-EU youth mobility. Broader theoretical horizons of the structural conditions in countries and regions also need to be brought into account. Both migrant agency and structural opportunities and constraints strongly influence migration and return decisions.

Broadening the concept of human capital

As path-breaking human capital theories state, ‘human capital’ is understood as the knowledge, skills, competences and other attributes embodied in individuals that are relevant to economic activity (Hartog Citation1999). Importantly, the level of human capital predicts success, costs and benefits in the labour market (Barkin Citation1962; Becker Citation1994; Schultz Citation1961; Sjaastad Citation1962). But migration also complicates this calculation due to the difficulties involved in transferring human capital between countries (Aydemir Citation2011; Chiswick and Miller Citation2009). Moreover, migrants might move precisely because they want to gain human capital abroad and are aspiring to gain a competitive edge on the labour market upon return (Bijwaard and Wang Citation2016; Dustmann, Fadlon, and Weiss Citation2011). Hence, we need to address the complexity of human capital acquired spatially and temporally. Moreover, we need to constantly question the very nature of the migration process itself, conceptualising it beyond a unidirectional understanding of a permanent human relocation, towards more dynamic and multi-directional mobilities, which may or may not involve permanent migration (King Citation2002; King and Williams Citation2018). Non-formal human capital can also be understood through the concept of tacit knowledge, defined as skills, ideas and experiences that individuals own, but are not codified and may not necessarily be easily expressed (Polanyi Citation1966; Williams and Baláž Citation2005). They are revealed distinctly in places and temporalities. The studies by Staniscia et al. (Citation2021), McGarry et al. (Citation2021), and Baláž et al. (Citation2021) are pushing forward the understanding of human capital in relation to such tacit knowledge in circular migration and upon return.

Further consideration is necessary regarding the types of skills. In the literature on migration and labour market integration, education level is often used as a key indicator of human capital (Demireva and Fellini Citation2018). However, as Williams and Baláž (Citation2005) have argued, formal education, and its translation into professional and economic outcomes, does not fully cover the diversity of skills which actually constitute ‘total human capital’ (Li et al. Citation1996) and ‘competences’ (Evans Citation2002). Hence, interpersonal skills, confidence, the role of social recognition and the different forms of knowledge that stem from the migration experience itself – all need to be incorporated into research on human capital dynamics in the context of migration.

The papers by Baláž et al. (Citation2021) and Janta et al. (Citation2021) confirm that formal and informal types of human capital are distinct and different. Even shorter experiences of migration improve soft skills and competences such as self-confidence and language ability that migrants value and are likely to enhance either their careers or personal development upon return. Some of these competences are being categorised as the social dimensions of human capital (Grabowska and Jastrzebowska Citation2021). Moroşanu et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate how migrants with lower formal education utilise a wider range of skills, beyond that their qualifications or occupations might indicate, to advance in the labour market, including generic skills such as creativity and work ethic. Hence, we argue that soft skills and competences that stem from migration experience should be included in the notion of ‘total human capital’ (Li et al. Citation1996). This broader definition further challenges assumptions about the transferability of human capital. Theoretically, there are similarities between the notions of human capital and Bourdieu’s (Citation1986) cultural capital. Cultural capital comprises education, and other forms of knowledge and intellectual skills, which provide advantage in achieving a higher social-status in society. Bourdieu also emphasised the importance of institutions’ formal recognition of a person’s cultural capital that facilitates the conversion of cultural capital into economic capital. Theoretical ideas are advanced by Aksakal and Schmidt (Citation2021) to uncover such institutional or structural barriers in receiving societies.

Knowledgeable migrants: beyond the higher- and lower-skilled divide

We question the conventional skills divide in existing theoretical assumptions. According to human capital theory, migrants tend to be categorised between lower-educated, tertiary-educated and students; yet, all individuals on the move are ‘knowledgeable and learning migrants’ (Williams Citation2006). The migration experience itself evokes intense learning in new environments and work places, and usually implies working in a different language. Education works as a ‘signalling’ of trainability for employers (Di Stasio Citation2014). And, while the acquisition of formal qualifications in terms of foreign degrees can be relatively easily measured, the task is to understand better how other, non-formal credentials, and new skills and competences are acquired at work and elsewhere, and how such informal skills and training can be measured or valorised. Complex informal skills matter, and may enhance mobile individuals’ future earnings and their career trajectories. Moreover, there is also an ethical need to rethink the categorisation of ‘lower-skilled’ as a depiction of ‘lower-ranked’ individuals. Professions and jobs are perceived as lower-skilled may require a great amount of embodied and culturally sensitive competences as well as self-confidence, physical endurance and more. Hence, we need to look at migrant skill portfolios as they combine and evolve over the life course, through different professional and migration trajectories.

Although all migrants may be knowledgeable and have potential for learning, their experiences can be diverse, and range from upskilling to deskilling, both in aggregate terms, and in respect of specific skills. Accordingly, re-thinking human capital theory and the nature of knowledge benefits not only economists but a broad spectrum of interdisciplinary migration scholars. Novel migration patterns question some long-standing theoretical perspectives in migration studies such as, for instance, dual and segmented labour market theories (Harris and Todaro Citation1970). Migrant agency and structural opportunities in a large metropolis, such as London, enable the chance to move out of insecure and dead-end jobs. Some classic theories (Chiswick, Lee, and Miller Citation2005; Fellini, Guetto, and Reyneri Citation2018; Rooth and Ekberg Citation2006) show that many Eastern but also some Southern Europeans experience enduring downgrading (not the U-shaped pattern) when they move westwards and northwards within Europe. The reasons for this seem to be related to economic inequality and socio-cultural factors such as bias and discrimination, but they can also be due to the migrants’ subjective perceptions and their (in)ability to present themselves (Nowicka Citation2014). The Special Issue builds further on considerable work done by human capital theorists and migration scholars to update and revise these ideas. Among these are, for instance, ideas of Eastern European ‘middling transnationals’ (Parutis Citation2014) who climb up career ladders; the role of regional disparities and dynamics within Southern Europe (Fonseca Citation2017), and the already-mentioned concept of the ‘learning migrant’ (Williams Citation2007) with nuanced attention to types of knowledge and skills.

Spatialities of human capital

While EU states have mutual recognition of formal qualifications, this important principle has its limits. Limits can be embedded within complex intersections of human and cultural capitals, which are place-contingent and variable in different regimes in EU nation-states. Formal qualifications are only part of total human capital. Therefore, overcoming the skills dichotomy feeds further into a broader and more critical understanding spatially of which countries and regions gain and which may lose due to ‘free’ mobility. As migrants are usually young, and have diverse motivations, they are less likely to be dependent on welfare systems and are highly motivated to participate in the labour market in destination countries, even if it initially involves de-skilling (Keereman and Szekely Citation2010). Problematising the skills divide leads us also to query the temporalities of human capital in certain locations. Recent research across OECD countries argues that higher-educated individuals prefer more mobile lives and through mobility, their human capital is valorised, while the lower-educated may seek a more permanent stay in immigration countries (Czaika and Parsons Citation2017). The higher-skilled are usually privileged in visa or points-based systems and can afford to take the risks of relocation. This is a pertinent question in regards to nascent trends to manage and control the migration of Europeans, along with new temporalities, most notably in the light of Brexit in the UK (Lulle et al. Citation2019).

In the recent, relatively intensively studied context of the UK, a range of Spatio-temporal human capital outcomes has been reported: from downgrading, mundane and dead-end occupations (Markova and Black Citation2007), ‘transitional jobs’ (Parutis Citation2014; Rolfe and Hudson-Sharp Citation2016) to migratory careers (Martiniello and Rea Citation2014). In the context of Germany, Basilio, Bauer, and Kramer (Citation2017) refer to ‘imperfect human capital transferability’, arguing that foreign schooling may be valued lower because of the imperfect compatibility of home- and host-country labour markets. Place-specific cultural capital (Kelly and Lusis Citation2006) helps to shed light on the interrelations between human and cultural capital in specific places. Clearly, distinguishing between country- and non-country-specific human capital is important in understanding human capital outcomes. Some countries, regions and cities are significant in the context of learning, and some destinations are strongly associated with learning skills and creativity (Williams Citation2006). The most iconic destination – London – has featured in several recent studies as a global financial hub and global city (King et al. Citation2018; Ryan and Mulholland Citation2014), seemingly promising high returns to one’s human capital. Yet, human capital gains in other regions, and the intersection of national versus regional effects, remain understudied.

Significant geographical differences exist with some regions being more competitive and attracting skilled professionals and thus stocks of human capital, which can eventually be turned into economic gain. Examples include the attraction of talent in technologies, science or medicine (e.g. Stanczyk Citation2016; Trebilcock and Sudak Citation2006). The inequality of human capital gains and losses geographically cannot be overlooked. Migration can both accentuate and ameliorate these inequalities, which are highly contingent. While the United Kingdom and Germany play the role of magnets in attracting more educated migrants (i.e. Aksakal and Schmidt Citation2021), Italy and Spain are more appealing to lower-skilled migrants due to their large demand for unskilled labour (i.e. Fellini, Guetto, and Reyneri Citation2018). London is known as an ‘escalator region’ (Fielding Citation1992) offering career opportunities unachievable, for example in Scotland or Italy; yet, a rich body of literature laments the downward mobility of non-Western European migrants, unable to transfer their credentials (i.e. Ciupijus Citation2011).

In this Special Issue, our attention travels to the metropolis of London; fast-growing regional hubs such as Bratislava; human capital outcomes in broader regional settings in Southern Europe; and a focus on specific countries, notably Germany and Sweden, where national language and often formal education requirements from a receiving country, tie the links between human capital outcomes to a certain country.

Temporalities: circular and return migration outcomes

The nature of return migration is changing. Relatively ‘free’ EU migration has resulted in ‘serial’ or ‘multiple migrations’ and ‘double returns’ (Main Citation2014; White Citation2014). Some migrants return from and return to multiple destinations or circulate between two or more places in Europe. These temporalities make us question how returning from multiple destinations shapes migrants’ skills acquisition, recognition and utilisation. How can such human capital be measured across time and space? Dustmann, Fadlon, and Weiss (Citation2011) argued that return may provide a competitive edge for the enhanced human capital, acquired by returnees. Yet, recent studies also show the obstacles that migrants face after return: lack of social networks due to time spent abroad and lack of recognition of foreign qualifications are some of the challenges returnees encounter (Barcevičius Citation2016; Lulle and Buzinska Citation2017; Vlase Citation2013). However, we need to re-embed return migration outcomes into new human capital theories. Returning to dynamic EU regions increases the chances of a successful reintegration on the home labour market, but it requires a broader understanding of the multiple relations between human capital and migration spatially. Return can improve innovative potential for the places and firms to which migrants return. Return itself can be an intense learning experience for a returnee. Return migrants face existing power relations in the places where they resettle, and can also face suspicions and a lack of tacit knowledge of the economy, political and social realities in the countries of return (King, Lulle, and Buzinska Citation2016). It may involve appreciation of skills gained abroad, but it also involves the requirement to develop further informal competences in the ‘home’ country because this country has also changed over time. These papers exemplify a broader common contribution of this Special Issue in regards of relationships between human and Bourdieusian cultural capital. To be able to utilise the capitals acquired abroad, a person may also need cultural and social capital in the country of return.

Moreover, new temporalities lead towards new conceptual debates on the circulation of skills, people and capitals in Europe. People strive to improve their existence in all life domains and not only in the workplace, and therefore research into circular, return or short-term migration examining human capital gains should go hand-in-hand with an understanding of the broader life satisfaction of those on the move. The accelerating temporalities of modern migration place an emphasis on learning on the move and the lifelong portfolio of skills and competences of migrants who have lived in multiple places for shorter times. Among many possible, two typical circulations evolve. The first involves maintaining ‘home’ and belonging in one place while circulating to others for work or study purposes. Secondly, young people are moving from one EU country to other, especially for education and work purposes, and thereby develop a sense of a broader space of possibilities under the ‘free’ EU regime. However, cautionary caveats must be added here: cultural, economic and social barriers exist in all EU nation-states, and instead of romanticising such ‘free’ circulations, they need to be unpacked further in terms of barriers for human capital and above all, quality and style of life of young and mobile Europeans.

While the extant literature is strong in national contexts (or in contexts of certain, usually high-skilled professions), we investigate actually existing shorter-term migration, ruptured migration trajectories, and multiple migrations either for the shorter term or in circular patterns. We also investigate the specific influences of different temporalities of migration, whether in terms of number of sojourns, or their duration (Janta et al. Citation2021). Hence, we need to establish a more robust understanding of how human capital gains are achieved over time and whether shorter-term migration develops social and individual competences as well.

Outline of papers

This Special Issue is largely based on the theoretical and methodological diversity of the empirical material amassed for the Horizon 2020 YMOBILITY project, in which both qualitative and quantitative data were collected from young individuals representing largely migration destination countries (Germany, Sweden, UK), sending countries (Latvia, Slovakia, Romania), and those which are both (Ireland, Italy, Spain). Some 30,000 questionnaires collected through an online panel survey from young Europeans aged between 16 and 35 years old captured migration versus non-migration intentions as well as various outcomes of youth-adult transitions, including learning experiences. The second phase of data collection, 840 in-depth interviews with migrants and returnees, focused on issues related to identity, return motivations, life satisfaction as well as life-time learning and working experiences. The last phase of the data collection included an experimental design using online-based software where individuals were asked to choose various migration scenarios. These databases provide unique insights into the transferability of human capital in the context of the nine project-partner countries. The papers presented in this Special Issue offer a range of methodological approaches, using qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods; a particular feature is that some papers present a pan-European analysis (Janta et al. Citation2021; McGarry et al. Citation2021), others a two-country comparative analysis (Staniscia et al. Citation2021) or single country cases (Moroşanu et al. Citation2021; Baláž et al. Citation2021; Emilsson and Mozetič Citation2021; Aksakal and Schmidt Citation2021), probing deeper into novel questions of human capital. The two studies outside of the YMOBILITY project (Palovic, Janta, and Williams Citation2021; Grabowska and Jastrzębowska Citation2021) focus on single country cases; Slovakia and Poland, utilising multiple data sources.

Three of the papers (Janta et al. Citation2021; Baláž et al. Citation2021; McGarry et al. Citation2021), examine perceptions of formal and informal human capital acquisition through intra-EU mobility, using data from a large quantitative survey. The focus here is on returnees in different contexts and human capital gains among circular migrants and other mobile groups. Four articles focus on under-studied contexts: examining return migration and its interrelations to location within Southern Europe by comparing returnees’ occupational experiences in Italy and Spain (Staniscia et al. Citation2021); exploring trajectories of ‘lower-skilled’ young migrants in the London region (Moroşanu et al. Citation2021); and examining destination countries with rather highly regulated labour markets, in Sweden (Emilsson and Mozetič Citation2021) and Germany (Aksakal and Schmidt, Citation2021). Two articles, both outside of the YMOBILITY project, seek to embed the young migrants’ experiences in a broader economic and social canvas: employers, as opposed to the young migrants’ perspectives in Slovakia (Palovic, Janta, and Williams Citation2021) utilising qualitative data; and migration-related skills, both individual and social, contributing to an understanding of the spill-over effects of knowledge transfer after return in Poland (Grabowska and Jastrzębowska Citation2021) using both quantitative and qualitative data. Most papers were presented at the IMISCOE conference in Rotterdam in 2017. We now summarise each paper’s contribution to the revisited human capital framework in turn.

Janta et al. (Citation2021) examine the influence of time and space in the acquisition of skills and competences through international mobility experience(s). The paper provides strong evidence that EU-intra mobility is valued highly among returnees when it comes to acquiring various skills. Different temporalities of migration, whether in terms of number of sojourns or their duration, shape skill acquisition. Interestingly, the effects of mobility depend on where migrants come from and where they migrate to; with individuals from Southern Europe benefiting more than those from Eastern Europe.

Baláž et al.’s (Citation2021) study focuses on the tacit and explicit knowledge transferred via migration in the context of return to Slovakia. The authors remind us that the transfer of uncommon tacit knowledge is most effectively realised via mobility which affords proximity, interactions, exchanges and direct observation. The key contribution here is a conceptualisation and operationalisation of the relationship between knowledge and skills.

Moroşanu et al. (Citation2021) examine narratives of occupational mobility and skills development amongst ‘medium-educated’ migrants in the London region. They show how participants acquire and use a variety of valuable technical and non-technical skills, which may help them advance occupationally. Findings problematise rigid distinctions between ‘high-’ and ‘low-skilled’ workers, and call for a broader understanding of human capital by capturing the often-neglected trajectories of those who may ‘get ahead’ within occupational sectors that do not normally require tertiary qualifications.

Palovic, Janta, and Williams (Citation2021) examine the nature of cultural capital and a less-studied aspect of skill transferability in the context of return migration – the perspectives of managers. Skills gained via migration are celebrated by Slovak managers, and they contribute to improved know-how of the business. The authors argue that these positive perceptions depend in part on similar experiences made by the managers themselves.

Emilsson and Mozetič (Citation2021) in their study of Latvians and Romanians in Sweden analyse the relationship between human capital, mobility and career outcomes. As a non-English-speaking country with regulated labour markets, the Swedish case provides a contrast to the dominant focus on English-speaking receiving countries with less-regulated labour markets. This contribution demonstrates that high formal education often means little in the new country, and that successful labour market integration depends on new investments in language and other forms of country-specific human capital.

Grabowska and Jastrzębowska (Citation2021) look at the impact of migration on the human capacities of two generations of Poles – born before and after the end of the Cold War era. The article explains the impact of working abroad in these groups on non-formal human capital, commonly known as soft skills, captured in this paper as human capacities It also explains how migration experiences are connected to life skills of self-improvement, communicating and relating to people, and understanding society.

Aksakal and Schmidt (Citation2021) problematise the role of cultural capital and its linkages to human capital with specific attention to location and migrants’ background. They argue that both external and internal conditions determine the levels and extent of capital migrants possess and are therefore relevant to further understanding of existing power constellations and inequalities. Migrant education and work strategies can lead to inequalities regarding their social mobility in Germany as younger migrants, ‘fresh out of school’, educated in Germany, often do better than their slightly older peers with credentials from other countries. Accordingly, this paper poses further questions on nation-state regulations and language capital empowering or constraining human capital gains.

Staniscia et al. (Citation2021) focus on the development of human capital in the context of migration and return to Spain and Italy. This study raises place-specific questions related to the transferability of skills. While the Italian case suggests brain circulation, in Spain, international mobility results in more challenging outcomes, with the highly skilled returnees struggling to find jobs matching their labour conditions abroad. The authors shed light on regional structures and comparisons of returnees, topics which have remained limited so far.

Finally, the paper by McGarry et al. (Citation2021) investigates the specific impact of circular migration on individual human capital gains and life satisfaction. Their analysis shows that human capital gains are positive but place of residence before migration affects human capital gains for circular migrants.

Conclusions

Understanding the opportunities and obstacles for the transfer of human capital is of paramount importance individually, nationally and regionally. Migration not only sets in motion the acquisition and utilisation of various and sometimes complementary formal and informal skills and competences, but it can also constrain, rupture and delay the development of human capital. The value of human capital is highly contingent. Spatiality, temporality, the connectivity of geographical places, formal and informal recognition of skills, and of these contingent factors enable or disempower migrants to pursue their careers, better lives and abilities to contribute to broader society. The central aim in this Special Issue is to outline novel theoretical and empirical ways to study contemporary youth migration. Our central conceptual conclusions on human capital and youth migration are three-fold.

Firstly, skills are diversifying. Formal and informal skills combine, and the latter can be even more important for the employability and personal success of young migrants. Learning is not limited to formal education; it takes place at work, including the low-skilled working environments (Moroşanu et al. Citation2021), through socialisation (Grabowska and Jastrzebowska Citation2021) or within the private sphere of the home (Williams Citation2006). Younger-age migrants also have the propensity to engage in multiple migrations (i.e. Janta et al. Citation2021) which offers opportunities for learning as well as constantly valorising one’s skill portfolio. Also, perceptions of one’s own human capital endowments combined with confidence and self-esteem shape migrants’ performance on the labour market.

As demonstrated in our Special Issue papers, lower- and medium-educated migrants also increase their informal human capital, through learning and career advancement in particular locations. Plentiful jobs in the unskilled sector of the British labour market offer opportunities to learn and thrive. However, the UK is not representative of the whole EU pattern of youth mobility and human capital. The experiences in Germany and Sweden – non-English-speaking countries with more regulated markets – differ considerably from the UK. Hence, human capital outcomes cannot be isolated from language issues (Esser Citation2006) and broader structural differences between welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen Citation1990; Hall and Soskice Citation2003). For future research, ideas about different European welfare regimes and regulations in relation to human capital transfers also need to be revisited in the generally more neo-liberal framework of the first decades of the twenty-first century.

Secondly, spatiality plays a constitutive role in the dynamics of human capital. Human capital can be place-specific: it could be valued in one place but perceived as less useful in other places. Therefore, we try to probe deeper into geographical factors. We study both migration destinations and countries of origin, whilst also acknowledging the importance of third and subsequent places as many respondents in our collaborative project research evolved their skill portfolios in multiple locations. Also, we raise issues of scale in intra-EU migration: how regions and particular cities matter versus national states on one hand and individual places on the other hand. At the macro-regional scale we also provide insights into the shifting positions of Eastern and Southern Europe in the map of migration flows, as well as of individual countries within these regions.

Thirdly, new temporalities, such as multiple, serial and circular migration patterns, challenge the relative fixity in our traditional understanding of human capital theory. Transnational experiences of temporalities, multiple mobilities and combinations of skills gained in various places may have a positive impact upon return. This is especially so for young people circulating between the Eastern and Western/Northern European countries. However, such variety of skills helps less when staying put in regulated markets with emphasis on nation- and place-specific human capital (as demonstrated in the cases of Germany and Sweden). Hence, causality – whether mobility enables acquisition of human capital or human capital is enabled by mobility – is highly contingent, in other words, place- and time-specific.

Further research is needed in different geographical contexts and under the ongoing uncertainties after the 2016 EU Referendum in the UK. While we relied on data from Europe, research on human capital dynamics needs to be applied globally. In terms of socio-demographics, future research needs to explore how human capital evolves among different age groups and genders, and across the life-course concept of a lifelong portfolio of skills and competences. More research is needed on employers’ and managers’ perspectives, in particular those without international experience or in small and medium size enterprises.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to scientific advisors Prof. Russell King (Sussex) and Prof. Allan Williams (Surrey) for guidance and constructive advice throughout all stages of this Special Issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aksakal, M., and K. Schmidt. 2021. “The Role of Cultural Capital in Life Transitions among Young Intra-EU Movers in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1848–1865. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679416.

- Aydemir, A. 2011. “Immigrant Selection and Short-Term Labour Market Outcomes by Visa Category.” Journal of Population Economics 24 (2): 451–475.

- Baláž, V., A. M. Williams, and D. Kollar. 2004. “Temporary Versus Permanent Youth Brain Drain: Economic Implications.” International Migration 42 (4): 3–34.

- Baláž, V., A. M. Williams, K. Moravčíková, and M. Chrančoková. 2021. “What Competences, Which Migrants? Tacit and Explicit Knowledge Acquired via Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1758–1774. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679409.

- Barcevičius, E. 2016. “How Successful are Highly Qualified Return Migrants in the Lithuanian Labour Market?” International Migration 54 (3): 35–47.

- Barkin, S. 1962. “The Economic Costs and Benefits and Human Gains and Disadvantages of International Migration.” Journal of Human Resources 2 (4): 495–516.

- Basilio, L., T. K. Bauer, and A. Kramer. 2017. “Transferability of Human Capital and Immigrant Assimilation: An Analysis for Germany.” Labour 31 (3): 245–264.

- Becker, G. S. 1994. “Human Capital Revisited.” In Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education (3rd ed.), edited by G. S. Becker, 15–28. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bijwaard, G. E., and Q. Wang. 2016. “Return Migration of Foreign Students.” European Journal of Population 32 (1): 31–54.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Translated by R. Nice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Brickell, K., and A. Datta, eds. 2011. Translocal Geographies: Places, Spaces, Connections. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Castro-Martín, T., and C. Cortina. 2015. “Demographic Issues of Intra-European Migration: Destinations, Family and Settlement.” European Journal of Population 31 (2): 109–125.

- Chiswick, B. R., Y. L. Lee, and P. W. Miller. 2005. “A Longitudinal Analysis of Immigrant Occupational Mobility: A Test of the Immigrant Assimilation Hypothesis 1.” International Migration Review 39 (2): 332–353.

- Chiswick, B. R., and P. W. Miller. 2009. “The International Transferability of Immigrants’ Human Capital.” Economics of Education Review 28 (2): 162–169.

- Ciupijus, Z. 2011. “Mobile Central Eastern Europeans in Britain: Successful European Union Citizens or Disadvantaged Labout Migrants?.” Work, Employment and Society 25 (3): 540–550.

- Czaika, M., and C. Parsons. 2017. “The Gravity of High-Skilled Migration Policies.” Demography 54 (2): 603–630.

- Demireva, N., and I. Fellini. 2018. “Returns to Human Capital and the Incorporation of Highly-Skilled Workers in the Public and Private Sector of Major Immigrant Societies: An Introduction.” Social Inclusion 6 (3): 1–5.

- Di Stasio, V. 2014. “Education as a Signal of Trainability: Results from a Vignette Study with Italian Employers.” European Sociological Review 30 (6): 796–809.

- Dustmann, C. 1999. “Temporary Migration, Human Capital and Language Fluency of Migrants.” Scandinavian Journal of Economics 101 (2): 297–314.

- Dustmann, C., I. Fadlon, and Y. Weiss. 2011. “Return Migration, Human Capital Accumulation and the Brain Drain.” Journal of Development Economics 95 (1): 58–67.

- Emilsson, H., and K. Mozetič. 2021. “Intra-EU Youth Mobility, Human Capital and Career Outcomes: The Case of Young High-Skilled Latvians and Romanians in Sweden.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1811–1828. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679413.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Esser, H. 2006. Migration, Language and Integration, AKI Research Review 4, Berlin: Social Science Research Center Berlin.

- Eurostat. 2019a. EU Citizens Living in Another Member State – Statistical Overview. Accessed January 28, 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_citizens_living_in_another_Member_State_-_statistical_overview#Who_are_the_most_mobile_EU_citizens.3F.

- Eurostat. 2019b. Youth Long-term Unemployment Rate. Accessed January 17, 2019. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=yth_empl_120&lang=en.

- Evans, K. 2002. “The Challenges of Making Learning Visible: Problems and Issues in Recognising Tacit Skills and Key Competences.” In Working to Learn: Transformative Learning in the Workplace, edited by K. Evans, P. Hodkinson, and L. Unwin, 79–94. London: Kogan.

- Favell, A. 2008. “The New Face of East–West Migration in Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (5): 701–716.

- Fellini, I., R. Guettoand, and E. Reyneri. 2018. “Poor Returns to Origin-Country Education for non-Western Immigrants in Italy: An Analysis of Occupational Status on Arrival and Mobility.” Social Inclusion 6 (3): 34–47.

- Fielding, A. J. 1992. “Migration and Social Mobility: South East England as an Escalator Region.” Regional Studies 26 (1): 1–15.

- Fonseca, M. 2017. “Southern Europe at a Glance: Regional Disparities and Human Capital.” In Regional Upgrading in Southern Europe, Advances in Spatial Science, edited by M. Fonseca and U. Fratesi, 19–54. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

- Fries-Tersch, E., T. Tugran, A. Markowska, and M. Jones. 2018. 2018 Annual Report on intra-EU Labour Mobility. European Commission. European Commission.

- Grabowska, I., and A. Jastrzebowska. 2021. “The Impact of Migration on Human Capacities of Two Generations of Poles: The Interplay of the Individual and the Social in Human Capital Approaches.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1829–1847. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679414.

- Hall, P. A., and D. Soskice. 2003. Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage. Oxford: Oxford Scholarship Online.

- Harris, J. R., and M. P. Todaro. 1970. “Migration, Unemployment and Development: A Two-Sector Analysis.” American Economic Review 60 (1): 126–142.

- Hartog, J. 1999. “Behind the Veil of Human Capital, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.” The OECD Observer 215: 37–39.

- Janta, H., C. Jephcote, A. M. Williams, and G. Li. 2021. “Returned Migrants Acquisition of Competences: the Contingencies of Space and Time.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1740–1757. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679408.

- Keereman, F., and I. Szekely, eds. 2010. Five Years of an Enlarged EU: A Positive Sum Game, 63–94. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

- Kelly, P., and T. Lusis. 2006. “Migration and the Transnational Habitus: Evidence from Canada and the Philippines.” Environment and Planning A 38: 831–847.

- King, R. 2002. “Towards a New Map of European Migration.” International Journal of Population Geography 8 (2): 89–106.

- King, R., A. Lulle, and L. Buzinska. 2016. “Beyond Remittances: Knowledge Transfer among Highly Educated Latvian Youth Abroad.” Sociology of Development 2 (2): 183–203.

- King, R., A. Lulle, V. Parutis, and M. Saar. 2018. “From Peripheral Region to Escalator Region in Europe: Young Baltic Graduates in London.” European Urban and Regional Studies 25 (3): 284–299.

- King, R., and A. M. Williams. 2018. “Editorial Introduction: New European Youth Mobilities.” Population, Space and Place, doi:10.1002/psp.2121.

- Li, F. L., A. M. Findlay, A. J. Jowett, and R. Skeldon. 1996. “Migrating to Learn and Learning to Migrate: A Study of the Experiences and Intentions of International Student Migrants.” International Journal of Population Geography 2 (1): 51–67.

- Lulle, A., and L. Buzinska. 2017. “Between a ‘Student Abroad’ and ‘Being from Latvia’: Inequalities of Access, Prestige, and Foreign-Earned Cultural Capital.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (8): 1362–1378.

- Lulle, A., R. King, V. Dvorakova, and A. Szkudlarek. 2019. “Between Disruptions and Connections: ‘New’ EU Migrants Before and After the Brexit in the UK.” Population, Space and Place 25 (1), doi:10.1002/psp.2200.

- Main, I. 2014. “High Mobility of Polish Women: The Ethnographic Inquiry of Barcelona.” International Migration 52 (1): 130–145.

- Marginson, S. 2017. “Limitations of Human Capital Theory.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (2): 1–15.

- Markova, E., and R. Black. 2007. East European Immigration and Community Cohesion. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. https://www.jrf.org.uk/bookshop/eBooks/2053-immigration-community-cohesion.pdf.

- Martiniello, M., and A. Rea. 2014. “The Concept of Migratory Careers: Elements for a New Theoretical Perspective of Contemporary Human Mobility.” Current Sociology 62 (7): 1079–1096.

- McGarry, O., Z. Krisjane, G. Sechi, P. MacÉinrí, M. Berzins, and E. Apsite-Berina. 2021. “Human Capital and Life Satisfaction Among Circular Migrants: An Analysis of Extended Mobility in Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1883–1901. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679421.

- Moroşanu, L., R. King, A. Lulle, and M. Pratsinakis. 2021. “‘One Improves Here Every Day’: The Occupational and Learning Journeys of “Lower-Skilled” European Migrants in the London Region.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1775–1792. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679411.

- Nowicka, M. 2014. “Migrating Skills, Skilled Migrants and Migration Skills: the Influence of Contexts on the Validation of Migrants’ Skills.” Migration Letters 11 (2): 171–186.

- Palovic, Z., H. Janta, and A. M. Williams. 2021. “In Search of Global Skillsets: Manager Perceptions of the Value of Returned Migrants and the Relational Nature of Knowledge.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1793–1810. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679412.

- Parutis, V. 2014. “‘Economic Migrants’ or ‘Middling Transnational’s’? East European Migrants’ Experiences of Work in the UK.” International Migration 52 (1): 36–55.

- Polanyi, M. 1966. The Tacit Dimension. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Rolfe, H., and N. Hudson-Sharp. 2016. The Impact of Free Movement on the Labour Market: Case Studies of Hospitality, Food Processing and Construction. National Institute of Economic and Social Research.

- Rooth, D. O., and J. Ekberg. 2006. “Occupational Mobility for Immigrants in Sweden.” International Migration 44 (2): 57–77.

- Ryan, L., and J. Mulholland. 2014. “Trading Places: French Highly Skilled Migrants Negotiating Mobility and Emplacement in London.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (4): 584–600.

- Salt, J. 1988. “Highly-skilled International Migrants, Careers and Internal Labour Markets.” Geoforum 19 (4): 387–399.

- Scholten, P., and M. Van Ostaijen, eds. 2018. Between Mobility and Migration: The Multi-Level Governance of Intra-European Movement. Cham: Springer Open.

- Schultz, T. W. 1961. “Investment in Human Capital.” The American Economic Review 51 (1): 1–17.

- Sjaastad, L. A. 1962. “The Costs and Returns of Human Migration.” Journal of Political Economy 70 (5): 80–93.

- Stanczyk, L. 2016. “Managing Skilled Migration.” Ethics & Global Politics 9 (1): 1–11.

- Staniscia, B., L. Deravignone, B. González-Martin, and P. Pumares. 2021. “Youth Mobility and the Development of Human Capital: Is there a Southern European Model?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (8): 1866–1882. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679417.

- Trebilcock, J., and M. Sudak. 2006. “The Political Economy of Emigration and Immigration.” New York University Law Review 81 (1): 1–60.

- Vlase, I. 2013. “‘My Husband is a Patriot!’: Gender and Romanian Family Return Migration from Italy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (5): 741–758.

- White, A. 2010. “Young People and Migration from Contemporary Poland.” Journal of Youth Studies 13 (5): 565–580.

- White, A. 2014. “Polish Return and Double Return Migration.” Europe-Asia Studies 66 (1): 25–49.

- Williams, A. M. 2006. “Lost in Translation? International Migration, Learning and Knowledge.” Progress in Human Geography 30 (5): 588–607.

- Williams, A. M. 2007. “Listen to Me, Learn with Me: International Migration and Knowledge Transfer.” British Journal of International Relations 45 (2): 361–382.

- Williams, A., and V. Baláž. 2005. “What Human Capital, Which Migrants? Returned Skilled Migration to Slovakia from the UK.” International Migration Review 39 (2): 439–468.

- Williams, A. M., C. Jephcote, H. Janta, and G. Li. 2018. “The Migration Intentions of Young Adults in Europe: A Comparative, Multilevel Analysis.” Population, Space and Place 24 (1): e2123.