ABSTRACT

Empirical work has documented the socio-economic characteristics of immigrants who naturalise and the effects of naturalisation on labour market outcomes. Political engagement and national identity are, however, salient but understudied dimensions of citizenship. Using two waves of the U.K. Household Longitudinal Study, I investigate immigrants’ national identification and political engagement before and after naturalisation. I find that before naturalisation those who acquire citizenship are more likely to identify as British, be familiar with the British political system and are less interested in politics compared to those who do not. I also find that after naturalisation, the importance of new citizens give to their British identity is higher than before, but their interest in politics is lower. I argue that citizenship retains its role as a marker of national identity for immigrants and that the negative association between naturalisation and interest in politics for immigrants is compatible with the low political engagement of the British-born population. I suggest that the further decline in interest in politics following naturalisation may be explained by immigrants’ disillusionment with a political narrative that fails to include them. I reflect on the implications of my findings for the conceptualisation of citizenship, for policy, and for future research.

Introduction

Citizenship is a legal status that grants rights and obligations, it is national identity and it is the status that gives us the power to act as political agents to govern the society we live in (Bloemraad, Korteweg, and Yurdakul Citation2008). Yet, national identity and political engagement are understudied dimensions of citizenship in the context of naturalisation. We do not know if national identity and political engagement are among the reasons why immigrants naturalise and/or are affected by naturalisation.

Around 123,000 immigrants acquired British citizenship in 2017, putting the United Kingdom (U.K.) in second place among European countries for the number of naturalisations conferred (Blinder Citation2018; Eurostat Citation2019).Footnote1 This is despite the burdensome, complex and expensive process required to naturalise. Concurrently, over the past two decades other forms of membership such as legal residence status, rather than citizenship, have become critical in determining access to most social and civil rights and privileges in the U.K. as in many other Western countries. The key tangible differences between residence and citizenship that endure are the right to vote in general elections,Footnote2 greater freedom of movement and the permanence of the status, which governments revoke only in extreme circumstances. Are these benefits the entire reason why over 100,000 immigrants acquire citizenship every year? The literature to date has focused on the barriers and incentives defined by different naturalisation policies, and on documenting the immigrants who naturalise with respect to their socio-demographic and socio-economic profile. However, the story we know of who and why immigrants naturalise is incomplete. Little has been said on whether national identification and being engaged with national politics are motives for naturalising.

It is also worth asking if citizenship simply acknowledges immigrants who are already de facto citizens or if it is also a means to shape them into citizens. Existing research shows that once naturalised, immigrants may enjoy better wages and higher rates of employment (e.g. Helgertz, Bevelander, and Tegunimataka Citation2014), but citizenship may also be a resource that fosters other dimensions of integration, national identification, national attachment, and political engagement.

In this paper, I further the understanding of the role citizenship has for immigrants by considering two neglected, though integral, dimensions of citizenship, national identification and political engagement. I use longitudinal data to measure immigrants’ identity as British and political engagement before and after the acquisition of citizenship. In the next section, I discuss the salience of these dimensions of citizenship within the British context and the empirical evidence on the nexus between them and citizenship acquisition. In the subsequent sections, I describe my data, samples and analytical approach. I follow with a discussion of findings and conclusions.

Background

Citizenship

Modern scholars define citizenship in democracies as a status that grants civic, political and social rights and responsibilities (Bloemraad, Korteweg, and Yurdakul Citation2008; Carens Citation2000; Kymlicka and Norman Citation1994). Among these, the right to vote ensures political equality in the governing of a well-defined society. Citizenship is also sense of belonging to that same society, that is identification with the nation-state and emotional attachment to the community (Bloemraad, Korteweg, and Yurdakul Citation2008; Yuval-Davis Citation2006). Such a definition highlights how citizenship may not only have an instrumental value, but also a sentimental and identitarian significance (Pogonyi Citation2019).

In Western countries, citizenship is the chief conferrer of rights and privileges, but the distance from other forms of membership has lessened. It has become increasingly challenging to deny non-citizens civil and social rights that in the post-war era have become associated with the individual, rather than the citizen (Soysal Citation2000). Alternative forms of national and supra-national membership have developed in a context of economic and cultural globalisation, with relevant cross-border institutions and increased mobility resulting from more flexible borders. From an instrumental perspective, these other forms of status have become almost as important in assigning rights. With residence permits, non-citizens enjoy the same rights as citizens, except for the right to vote in general elections and greater freedom of movement. The European Union is also a supra-national institution that ensures social and civil rights to all its citizens, beyond their national status and residence permit.

Although citizenship has lost its distinctive primacy as a legal status that secures social and civil rights, it may still be associated with national identity and the will to engage politically. For the immigrants who acquire it, citizenship may hold more than an instrumental function.

Citizenship and national identity

Public and academic discourse often uses the terms citizenship and national identity interchangeably (Simonsen Citation2017). For example, it is only by virtue of being part of the same national community that we can justify paying taxes and support redistribution for the benefit of strangers (Sindic Citation2011). Citizenship lends itself to being a basis for a social identity as an institution that officially draws a line between those who hold the status and those who do not. The membership of those who belong as opposed to those who do not is clearly defined and conceptually charged. Criteria for naturalisation are illustrative. In the U.K., where these include a citizenship test on life in Britain, a language requirement and a ceremonial oath to pledge allegiance to the crown, citizenship is not a neutral legal institution that confers rights and duties, but it is also a symbolic one that delivers a conceptualisation of what it means to be British. In his comparative work on France and Germany, Brubaker (Citation1994) highlights how citizenship is about national identity and argues that immigration has triggered public discussions over citizenship acquisition policies, which are about what it means to belong to the nation-state, not about what and who gains from citizenship acquisition; ‘it is a politics of identity, not a politics of interest’ (Citation1994, 182). Survey data confirm that the loyalty and affection for nations remain unchallenged by other forms of community, such as a global or a European one (Heath and Roberts Citation2008; Smith and Jarkko Citation1998).

The nexus between national identity and citizenship may exist also for immigrants who are not granted citizenship at birth, but who make the decision to naturalise. Identifying with the country of residence can both be a reason for naturalising and a result of citizenship acquisition. Alternatively, as immigrants usually hold a different citizenship status and typically identify as belonging to another state, they may not be open to signing up to British identity. As their stories of belonging are, to different extents, rooted in the country of origin, they may view citizenship entirely as a legal status with attached benefits.

Nonetheless, a number of empirical studies focusing on particular countries or particular groups of immigrants in different national contexts, have found evidence of a link between citizenship acquisition and national identification. Bevelander and Veenman (Citation2006) for the Netherlands, Platt (Citation2014) and Manning and Roy (Citation2010) for the U.K. find that naturalised immigrants are more likely to identify with the host country compared to non-naturalised immigrants. Reeskens and Wright (Citation2013), and Karlsen and Nazroo’s (Citation2013) claim that citizen immigrants in the EU are more attached to the destination country than non-citizens. This evidence suggests that, even if the host country does not replace the home country, identification can gradually change over time (Casey and Dustmann Citation2010).

The cross-sectional nature of these studies prevents them from identifying the mechanisms at the heart of this relationship, which, potentially, goes both ways. As for any social identity, social recognition is as fundamental as identification in shaping national identity (Duveen Citation2001). Recognition of a social identity can take many forms, but its absence jeopardises one’s self-definition (Hopkins and Blackwood Citation2011). Arguably, immigrants seek the legitimisation of their national identity embedded in legal institutions when they already identify as British. It follows that I expect those who identify as British to be more likely to later naturalise. The official recognition sanctioned by the passport then completes the sense of national identity, which should therefore intensify. Moreover, as the state gives citizenship to a select group of applicants on strict conditions, we can expect those who succeed to feel a stronger rightful claim to Britishness compared to those who do not. I, therefore, expect citizenship to enhance the importance given to immigrants’ British identity.

Citizenship and political engagement

Citizenship ensures political equality and representation by conferring the right to vote. In democracies, non-citizens are not represented by the government and therefore do not contribute to the governing of the state and to the legislative process. When fundamental rights and entitlements to benefits are protected by supra-national institutions, voting and other more informal forms of national political participation may become less pivotal in shaping policy. Arguably, this is especially the case for European citizens and permanent residents whose rights are protected independently of citizenship status. Nonetheless, Britain’s decision to leave the European Union (EU), which has resulted in a surge in citizenship applications by European citizens, is a recent example of a political upheaval that might affect the position of non-citizens who could not express their preference in the referendum. Nations still represent the primary political framework in which individuals assert their rights and have a claim on equality (Calhoun Citation2007).

Although citizenship grants the right to participate in the governing of the state, it translates into political participation only if there is sufficient political engagement. That is, people participate when they are sufficiently interested and knowledgeable (Russo and Stattin Citation2017). It follows that on the one hand, the more politically engaged immigrants may be more likely to naturalise in order to gain the right to vote. On the other, the formal right to participate may trigger greater interest and acquisition of knowledge. Cross-sectional evidence by Diehl and Blohm (Citation2003) and Kesler and Demireva (Citation2011) for Europe, and by Leal (Citation2002) for the U.S.A., tell us that on average naturalised citizens are more interested in politics, are more likely to identify with a political party in their country of residence, and to engage in a range of activities such as signing petitions or joining protests.

There is evidence that voting is one of the reasons why immigrants naturalise for those who are most politically engaged. A group of Prabhat’s (Citation2018) respondents told her they wanted to acquire British citizenship to be able to vote. Stewart and Mulvey (Citation2011) also find that among Scottish refugees political representation was a key motive for citizenship application. Street (Citation2017) for the U.K. and Kahanec and Tosun (Citation2009) for Germany find that that more politicised immigrants self-select into citizenship.

However, if we see citizenship acquisition as a process of integration and assertion of belonging, it may be to those who are less politically engaged that citizenship is a more natural pathway. In the U.K., levels of political engagement are low among native British citizens. Only two thirds of British citizens voted in the last few general elections and even fewer vote in local and European elections (House of Commons Library Citation2017). It follows that if those who are most integrated within British society are the ones most likely to acquire citizenship, their level of political engagement should be relatively low. Heath et al. (Citation2013) argue that immigrants show higher levels of commitment to voting than the British majority but that, with time, they tend to converge to similar levels. The relationship between political engagement and naturalisation may therefore not be clearcut.

In line with existing cross-sectional evidence, citizenship acquisition may also foster political engagement. Citizenship is a legal resource that, by granting the formal right to participate, may spark political interest and knowledge. Beyond the legal aspect tied to the right to vote, citizenship is also closely tied to national identity and attachment to the community. Citizenship may, therefore, represent a psychological resource for people who feel like they belong to the polity and want to participate politically (Just and Anderson Citation2012). Political engagement should, therefore, continue to grow following naturalisation. Bevelander and Pendakur (Citation2011) find that citizenship increases the probability of voting. Waldinger and Duquette-Rury (Citation2016) find that Latino immigrants in the U.S.A. become more politically invested in the host country after naturalisation, but Levin’s (Citation2013) analysis on the same population finds mixed results.

Although we would expect the right to vote to spark political engagement, we cannot ignore the possibility that the anti-immigrant sentiment in political discourse over the period considered may generate some form of cognitive dissonance. Immigrants who identify as British and have been granted British citizenship may feel disillusioned and disappointed by a political discourse that excludes them. Media representations and the political climate make it particularly hard for certain groups of immigrants to feel included in a British identity. For example, the redefinition and public representation of Britishness have often explicitly juxtaposed British values presented as liberal with Islamic values portrayed as non-liberal (Sales Citation2010). Favell (Citation2013) has also identified the ‘sociological reality’ of Eastern Europeans being at the bottom of a European hierarchy, despite enjoying the same rights as other Europeans. Psychologists’ work on interest formation suggests that social conditions are paramount to sustain interest development (Hidi and Ann Renninger Citation2006). Moreover, citizen immigrants may feel more exposed to hostility towards immigrants in general and disappointed by the political system and by the lack of opportunities for social mobility (Levin Citation2013). If trust and political engagement are tightly linked, citizen immigrants may be less inclined to engage with politics (Putnam Citation2000). This dissonance between subjective perception of belonging and the political narratives and empirical realities of exclusion might push people to further disengage especially after the acquisition of citizenship.

Moreover, research suggests that political behaviour forms during teenage years and does not change much over the life course (Galston Citation2001; Schlozman, Jennings, and Niemi Citation1982). Consistent with this, Street (Citation2017) finds an effect of naturalisation on political engagement only for immigrants who naturalise in early adulthood. If so, naturalisation in adulthood may not affect immigrants’ existing disposition towards political engagement.

Other determinants of naturalisation

Any analysis that investigates the relationship between national identification, political engagement and citizenship acquisition needs to account for other determinants of and barriers to citizenship. Research for different European countries and the U.S.A. finds that years of residence, age and age at migration influence the likelihood of naturalisation, indicating that duration of stay gives more opportunities and higher motivation to integrate with the host population (e.g. Picot and Hou Citation2011 for North America; Vink, Prokic-Breuer, and Dronkers Citation2013 for 16 European countries). Arguably, immigrants of a low socio-economic status face higher barriers to naturalisation. The application process may be more daunting for people with low education levels and its cost may be unaffordable for immigrants with low income. However, not all research has found evidence of this. Fougère and Safi (Citation2008), Chiswick and Miller (Citation2008) are recent examples of studies which do find this relationship for France and the U.S.A; while DeVoretz and Pivnenko (Citation2008) and Bevelander and Veenman (Citation2006) do not for Canada and the Netherlands.

Family ties in the host country may also indicate how anchored one is there. Evidence suggests that immigrants in North America and in Europe who are married are more likely to naturalise than single immigrants (Chiswick and Miller Citation2008; Vink, Prokic-Breuer, and Dronkers Citation2013; Yang Citation1994), especially if married to someone of the destination country’s nationality (Bevelander and Veenman Citation2006). Evidence about having children is mixed. Yang (Citation1994) and Vink, Prokic-Breuer, and Dronkers (Citation2013) find that it enhances the probability of naturalisation, but Bevelander and Veenman (Citation2006) and Chiswick and Miller (Citation2008) do not. Country context could play a role in how the presence of children influences the decision to naturalise. In the U.K. a parent need not be naturalised for her/his child to be entitled to citizenship. At the institutional level, several studies, mostly for the U.S.A., find that the propensity to naturalise is lower for immigrants whose source country has a high level of economic development and civil liberties, suggesting that country of origin might affect the opportunity cost of choosing to naturalise (Mazzolari Citation2009; Picot and Hou Citation2011; Vink, Prokic-Breuer, and Dronkers Citation2013).

Net of these factors, I investigate immigrants’ degree of national identification and political engagement, both before and after naturalisation.

Data and methods

Sample

I use Understanding Society (UKHLS) waves 1 (2009–2011) and 6 (2014–2016). The UKHLS is a nationally representative household panel study that collects information on people’s social and economic circumstances, attitudes, behaviours and health (University of Essex Citation2017). This longitudinal survey has collected annual information from respondents from a sample of over 30,000 households first surveyed in 2009 and includes interviews with all adult household members of original respondents at each sweep. Understanding Society is particularly suitable for this study as it includes an ethnic minority boost sample (EMBS) that focuses on the larger minority groups, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, black Caribbean and black African. The sample design ensures that there are at least 1,000 interviewees from each of these groups. Northern Ireland is excluded from the EMBS sample. Interviews are mostly conducted in English, but translation is also provided when requested (Knies Citation2018). Some questions, the ‘extra five minutes’, are specifically relevant to ethnic minority groups (e.g. identification with parents’ ethnicity) (Knies Citation2018) and are asked of a subsample of respondents (the EMBS sample, a comparison sample from the main sample, and ethnic minority individuals living at wave 1 in areas with relatively low proportions of minorities, which were therefore not covered by the EMBS).

The population of interest for this paper is immigrants who did not have citizenship when first observed in Understanding Society. I use the word immigrant to refer to anyone not born in the U.K., although this includes people who have come to the U.K. at different periods, more or less permanently, and for a variety of reasons and therefore under different conditions. All U.K. born respondents are excluded from my analysis.

Wave 1 and wave 6 are the only interview rounds when citizenship status is recorded. My initial sample comprises 997 immigrants who were not British citizens at wave 1 and who responded to the survey at wave 6. Of these, 407 acquired citizenship after wave 1 and before wave 6, and 590 did not. My sample, therefore, excludes immigrants who acquired citizenship before wave 1. These have lived in the U.K. for longer on average, as the length of stay is an important determinant of naturalisation (e.g. Vink, Prokic-Breuer, and Dronkers Citation2013). I further restrict the sample to immigrants who have been living in the U.K. for at least two years by wave 1 because, by wave 6, they will have lived in the U.K. for at least seven years, giving them enough time to be eligible for and attain citizenship.Footnote3 This is a conservative way to select the population at risk of acquiring citizenship as there are other cases where permanent residence/indefinite leave to remain status, that usually precedes the opportunity to make a citizenship application, is acquired more quickly or is not necessary. As I use only complete cases,Footnote4 my analytical sample is reduced to 884 respondents, 514 of whom remain non-citizens by wave 6 and 370 who acquire citizenship. Full sample descriptive statistics are provided in Table S1 and Table S2 of the Supplementary Material (SM).

If the respondents who drop out of the survey after wave 1 differ systematically from the rest, estimates may be subject to attrition bias. For example, this might be the case if the immigrants who leave the survey are the ones returning to their country of origin and who would have therefore differed systematically from my sample in their likelihood of acquiring citizenship. I apply wave 6 adult probability weights included in the dataset in order to minimise the effects of attrition.

Measures

I outline the measures and then the methods for first investigating how far identification and political engagement are associated with citizenship and second investigating how far citizenship acquisition is associated with the identification and political engagement.

National identification and political engagement before citizenship acquisition

Dependent variable. Naturalisation: I derived this measure from wave 1 to wave 6 questions on whether the respondent is a U.K. citizen, citizen of their country of birth or citizen of another country. I recoded the latter two categories into one, resulting in a dichotomous variable that indicates whether (1) or not (0) the wave 1 respondent has acquired British citizenship by wave 6. I make no distinction between those who hold dual nationality and those who do not.

Independent variables of interest measured at wave 1. National identification: The survey includes a question that asks what respondents consider their national identity to be, with the available options Scottish, Welsh, English, British, Irish and other. I collapse the first four nationalities under ‘British’. Answers can be given alone or in combination. There are two resulting categories: ‘Other’ (0) if British nationality is not mentioned, and ‘British’ (1) if British nationality is mentioned alone or in combination with another nationality. As a sensitivity check, I also measured national identification as ‘British only’, ‘Other only’ and ‘British and other’; the results were robust to this alternative specification.

Political engagement: I operationalise political engagement as the interest and knowledge needed to engage in politics.

Interest in politics: Respondents are asked the extent to which they are interested in politics on a four-item scale that ranges from ‘not at all’, to ‘very’.

Familiarity with the political system: I combine responses to questions aimed to gauge whether the respondent has a preference for a political party or not. Respondents are first asked if they support a political party and if their answer is negative, whether they feel a little closer to one. The second question, therefore, nudges them to give a preference even if they do not identify as supporters of any party. Given that the British political system is almost a two-party system, even without supporting one of the two parties, it is fairly easy to choose which one is closest to one’s beliefs. Hence these two questions measure knowledge and familiarity with the political system as opposed to partisanship.

Other covariates measured at wave 1. Partnership and cohabitation status: I matched information about cohabiting partners and spouses to create a variable in three categories: single/no co-resident partner, with a non-U.K. born partner, with a U.K.-born partner.

Presence of children: I recoded the original survey question into a dichotomy of whether the respondent is a parent of any children.

Children’s country of birth: I derived a variable that indicates whether at least one of the respondent’s children was born in the U.K. I inferred this if the birth of any child took place after a year of arrival to the U.K.

Employment status: I recoded the original survey question into three categories: employed or self-employed, unemployed and economically inactive, which includes respondents who are retired, studying full-time or in caring roles.

Household income: measured over the last month before the interview and divided by 1000 to aid interpretability.

Age left education: I derived the age at which the respondent left school or university, in the U.K. or elsewhere.

Country of education: I derived an indicator of whether at least some of the respondent’s education took place in the U.K. I imputed that this was the case if the respondent left school/university after arriving to the U.K.

Language proficiency: I derive an indicator of whether the interview was translated or conducted in English.

Home ownership: I derive a binary measure of whether the respondent lives in an owned (including with a mortgage) or rented home.

Years of residence: I measure the length of residence in the U.K. by the number of years between arrival and the date of interview. As a sensitivity check, I allowed for non-linearity by including it as a categorical variable. The results were robust to this alternative specification.

Demographic variables: I include sex, age and age squared.

Region of origin: I use the 2015 Human Development Index (HDI) of country of birth instead of the country of birth itself because individual country sample sizes are very small. HDI also allows to account for the higher incentive to naturalise for people of low-income countries. I changed the scale from 0–1 to 0–100 to aid interpretation. I add an indicator of whether respondents were born in a European country, which brings particular rights, including freedom of movement across Europe, that might make naturalisation less important, and whether they were born in a country that is part of the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth comprises 53 states that are mostly former territories of the British Empire. Although the British government stripped immigrants originally from Commonwealth countries of their status of subjects to the British crown in 1981 (immigration restrictions had already been introduced as of the 1960s), it left them full voting rights. Irish, Cypriot and Maltese citizens are European citizens who have also had full voting rights in the U.K. since 1949. I include a dummy to capture these nationalities who are less incentivised to naturalise.

National identification and political engagement after citizenship acquisition

Dependent variable: The outcome variables are interest in politics, familiarity with the political system and the importance given to being British in wave 6. Respondents are asked to rate the importance they give to being British on a scale from 0 to 10 and where 11 is for respondents who spontaneously state that they do not consider themselves as British. I convert the scale to be from −1 to 10. I use this variable instead of the direct national identity measure used in the first part of the analysis because the latter is only asked at wave 1. Although the importance of being British is included both in waves 1 and 6, in wave 1 it is only asked of the ‘extra five minutes’ subsample of respondents and of respondents interviewed in the first 6 months of fieldwork, therefore, reducing sample size considerably.

Independent variable: The independent variable of interest is British citizenship status in wave 6, which indicates if the respondent has naturalised between after wave 1 and before wave 6.

Analytical approach

National identification and political engagement before citizenship acquisition

I estimate a probit regression model of the likelihood of naturalisation. With this method, I jointly explore the relationship between national identification and political engagement, and naturalisation. In addition to using weights, I also cluster standard errors by wave 1 household to avoid bias in standard error estimation arising from within-household error correlation.

National identification and political engagement after citizenship acquisition

Addressing this part of the research question presents three main challenges related to the lack of precise information on the date of naturalisation, which we only know happened in a window of time between before wave 1 and after wave 6. First, it is possible that any change in national identification and political engagement between waves 1 and 6, measured at wave 6, has occurred or started before naturalisation. For the respondents for whom this is the case, my analysis overestimates the effect of naturalisation. Second, it is possible that any change in national identification and political engagement between waves 1 and 6 affects the likelihood of naturalisation. That is, it drives naturalisation and remains constant thereafter. Third, there could be unobserved drivers of both naturalisation as well as national identification and political engagement. However, since wave 6 outcomes are also measured at wave 1, i.e. before naturalisation, I can control for time-invariant unobservables that affect national identification and political engagement, therefore reducing bias and estimating the net effect of citizenship acquisition. Nonetheless, time-varying unobservables may still affect national identification and political engagement in wave 6. For instance, the current state of British politics could influence both the willingness to naturalise and engagement with British politics.

Despite these data limitations, which limit the extent to which I can make causal claims, the data make it possible to observe the change in national identification and political engagement between waves and its relationship with citizenship acquisition. I use inverse-probability weighted regression-adjustment (IPWRA), a combination of matching and regression, whereby parametric regression is applied to matched data. I employ matching as opposed to regression alone because, by comparing respondents in the treatment group (i.e. those who acquired citizenship) and control group (i.e. those who did not acquire citizenship) with similar observed characteristics, it avoids areas where there is no overlap of covariates between the treatment and control group, a scenario where regression alone has been shown to perform poorly (Dehejia and Wahba Citation2002; Glazerman et al. Citation2003). Moreover, IPWRA is doubly robust if either one of the specifications of the prediction model of the treatment, naturalisation (estimated with matching) or of the outcome, national identification and political engagement (estimated with regression), is correctly specified. IPWRA, therefore, decreases the sensitivity of the estimated average treatment effect (ATE), the difference in mean outcomes, to the particular specification (Hill and Reiter Citation2006; Ho et al. Citation2007). As suggested by Stuart (Citation2010) and Schafer and Kang (Citation2008), using matching methods jointly with regression adjustment also reduces bias and increases efficiency compared to matching alone. Employing regression adjustment after matching ‘cleans up’ residual covariate imbalance between the treatment and control group, therefore minimising the bias related to observables (Stuart Citation2010). Finally, it provides a host of diagnostics that help to assess the quality of the model. A step-by-step breakdown of the analysis can be found in SM.

I estimate three separate models of the effect of citizenship acquisition on each outcome measure. For each one, I estimate both the average treatment effect (ATE) and the average treatment effect on the treated (ATET). The ATE estimates the effect of citizenship acquisition for the entire population of immigrants, both those who do and those who do not acquire citizenship. The ATET estimates the effect of citizenship acquisition only for the immigrants who do acquire citizenship. Details of covariate balance checks and successful common support assumption testing can be found in the SM.

For both sets of analyses, I focus on my discussion of results on the variables of interest and report key results in graphical form. Full tables of results are provided in the SM.

Results

National identification and political engagement before citizenship acquisition

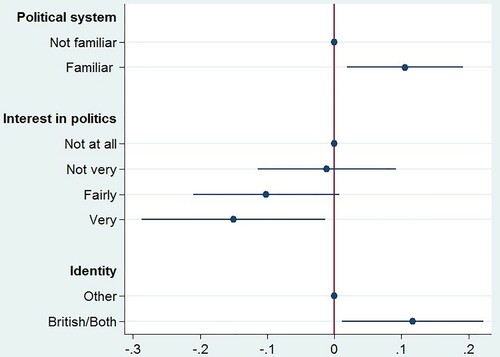

presents the average marginal probabilities of naturalisation by wave 6 for the key independent variables of interest, adjusting for other covariates. The full set of results from the probit regression can be found in the SM, Table S3. Identification as British, interest in politics and familiarity with the political system, all appear to matter in the decision to naturalise. shows that immigrants who identify as British, or as both British and another nationality, have an average marginal probability of 12 percentage points higher than that for immigrants who identify only with another nationality. For many successful applicants, identification as British takes place before citizenship acquisition. This finding suggests that net of other drivers and barriers, identifying as British provides immigrants with a motive to naturalise. These findings are consistent with theories of social identity that illustrate the role of social recognition in identity formation (Hopkins and Blackwood Citation2011). Arguably, immigrants who identify as British seek social and official recognition through citizenship acquisition. This form of acceptance may be particularly important to more marginalised groups who may feel their British identification is not matched by general public endorsement.

Figure 1. Average marginal effects of national identification and political engagement.

Notes: Average marginal effects computed after the probit model of the probability of acquiring British citizenship with clustered standard errors and weights. Circles show point estimates and the horizontal lines delineate 95% confidence intervals. Circles without horizontal lines show reference categories. Estimates control for sex, age, age squared, years of residence, HDI of country of origin, Europe indicator, Commonwealth indicator, gross household income, home ownership, age left education, whether any education in the U.K., presence of children, whether any children born in the U.K., partnership status, employment status, language proficiency.

As regards political engagement, the more immigrants are interested in politics, the less likely they are to naturalise. The effect is large, with those very interested in politics being 23 percentage points less likely to become citizens than those who are not at all interested. However, immigrants who are more familiar with the British political system are more likely to naturalise. The combination of these results may be puzzling at first because we would expect the two dimensions of political engagement to work in the same direction.

Reflection on what the two variables are measuring may help to explain these patterns. Familiarity with the political system is a necessary condition for political participation. Becoming familiar with the country’s political parties may not necessarily provide motivation for naturalisation, but might nevertheless signal a certain degree of integration. Without actively seeking this information, we can expect most people who read or watch the news and who have built ties with natives, to have some knowledge of British political parties. Sufficient knowledge of the British political system is also required to pass The Life in the U.K. test, a condition for Indefinite Leave to Remain or naturalisation. Immigrants who are more familiar with the British political system are therefore more likely to be those who self-select into citizenship. Importantly, this familiarity is necessary for later participation, enabled by the right to vote associated with citizenship.

In contrast, it is more difficult to interpret what the question on interest in politics is actually measuring. In light of the negative relationship with naturalisation, one possibility is that non-U.K. born respondents interpret the question with reference to their home country rather than to the U.K. If this were the case, it would mean that those who are more interested in the politics of their home country are less likely to naturalise. However, further investigation suggests this is not the explanation. First, if respondents thought about their country of origin in their answer to the interest in politics question, I would expect the immigrants most interested in politics to be the least familiar with the political system. However, the positive association between the two variables indicates otherwise (Table S4 in the SM). Secondly, I test whether there is a correlation between identifying only as a national of a country that is not the U.K. and higher interest in politics. The result of a simple t-test shows that the relationship is the opposite. The immigrants who identify as British, or as both British and another nationality as opposed to another nationality only, are significantly more interested in politics (Table S5 in the SM).

Alternatively, the survey question may evoke an interest in geo-politics that stretches beyond well-defined geographical borders and that leads people to be less invested and potentially critical of investment in naturalisation in a specific country. The lack of this awareness of those who are relatively less interested in politics may even be helpful in fostering the propensity to naturalise.

Finally, this finding may indicate that the immigrants who later naturalise have integrated more into British society than those who do not. As discussed, integration into British culture might equate to lower engagement with British politics. The British Social Attitudes survey provides evidence of an increasing disconnection with politics and a general voter apathy since the turn of the millennium (Phillips and Simpson Citation2015). On a similar question about interest in British politics in the same period 2009/2010, they report that only one third of respondents expressed a ‘quite a lot’ or ‘a great deal’ of interest in politics (Butt and Curtice Citation2013). I compare how new citizens, non-citizens, those who already acquired citizenship before wave 1, and native citizens are represented on the ‘interest in politics’ scale. Remarkably, for all groups, the majority say they are either ‘not at all’, or ‘not very’ interested in politics. The group with the highest proportion of respondents expressing they are ‘very’ interested in politics is that of non-citizens (Table S6 in the SM).

Although all respondents become eligible for naturalisation by wave 6, some are eligible for more time than others. As a sensitivity check for this, I re-estimate the model on a restricted sample of immigrants who were already eligible for citizenship at wave 1, i.e. they had been living in the U.K. for at least six years. Results are consistent with previous estimates (Table S7 in the SM).

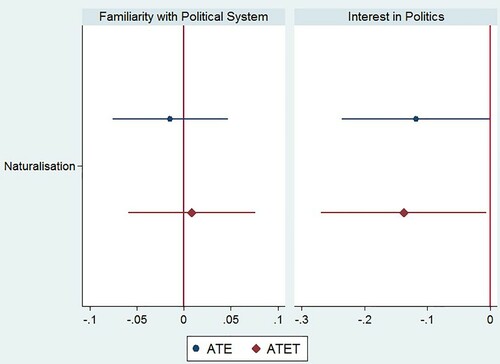

National identification and political engagement after citizenship acquisition

The second part of my analysis examines whether citizenship is a resource that fosters national identification and political engagement in British society. shows that immigrants who naturalise are not more likely to be familiar with the British political system. This is probably due to the more knowledgeable people having already self-selected into citizenship and to the variable not measuring the degree of familiarity, but merely if there is any familiarity or not. does, however, show that after naturalisation, citizens report a lower level of interest in politics than non-citizens. That is, other things being equal, not only the least interested in politics self-select into citizenship, but their interest continues to decrease thereafter. This finding is consistent with Bartram’s (Citation2019) analysis using the same data, but different methodological approaches. He argues that the requirements for naturalisation (tests and ceremonies) are to blame for the decrease in political interest. However, this explanation seems speculative. Importantly, it fails to take account of the fact that, as I have shown here, interest in politics is lower for citizens than non-citizens even before citizenship acquisition takes place. Moreover, the ‘citizenship’ tests are a requirement not only to attain citizenship for EU nationals, but they are also required to attain Indefinite Leave to Remain for non-EU U.K. residents, whether or not they subsequently apply for citizenship. Alternatively, it is plausible that the contrast between identifying as British and being a British national but being excluded by the political discourse which continues to associate immigrants with being non-British, pushes naturalised citizens further away from being engaged with the political world (Sales Citation2010). Especially after the strenuous process of naturalisation, those who already feel and are British may resent such non-acceptance and therefore dissociate from the political system that fosters it (Prabhat Citation2018).

Figure 2. The ATE and ATET of the acquisition of citizenship on the probability of being familiar with the British political system and the degree of interest in politics.

Notes: Average treatment effects (ATE) and average treatment effects on the treated (ATET) estimated through inverse-probability weighted regression-adjustment (IPWRA) on the likelihood of being familiar with the political system and on the degree of interest in politics. Circles/diamonds show point estimates and the horizontal lines delineate 95% confidence intervals.

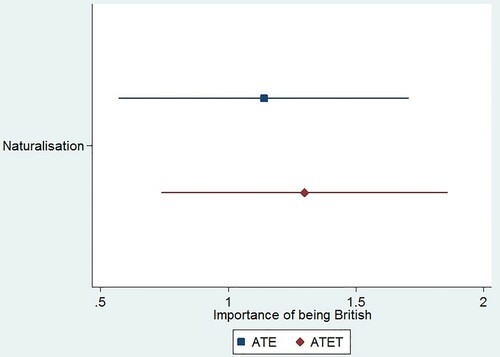

As expected, immigrants who naturalise give higher importance to their identity as British by around 1 point on a scale from −1 to 10 compared to those who do not. As shown in , this is true both for the ATE and ATET. Although I cannot confidently say that the growth in the importance given to being British followed naturalisation, the finding reveals that growth in British identification occurs in association with naturalisation. The finding also suggests that, although immigrants who naturalise were found to already identify more as British before naturalising, their sense of identity strengthens once they gain official recognition. The fact that the application process is costly and challenging might also contribute to creating a feeling of satisfaction and pride for those who are successful in attaining citizenship and may feed into boosting the importance given to their British identity.

Figure 3. The ATE and ATET of the acquisition of citizenship on the extent to which the respondent deems being British as important.

Notes: Average treatment effects (ATE) and average treatment effects on the treated (ATET) estimated through inverse-probability weighted regression-adjustment (IPWRA) on the degree of importance given to British identity. Circles/diamonds show point estimates and the horizontal lines delineate 95% confidence intervals.

Conclusion

Much of the discontent with multiculturalist policies in Europe concerns the lack of social cohesion between minority and majority groups under a common national identity (Koopmans Citation2013). Identifying as nationals of the country one lives in and engaging politically is important both for individuals’ wellbeing and for the sake of society’s functioning. In this paper, I asked if immigrants naturalise once they already feel and act as citizens. I find that they do. They feel British, they are familiar with the British political system and are as disengaged with politics as the average native population. I also asked whether citizenship contributes to immigrants’ growth as citizens. I find that their identity as British nationals strengthens and that their interest in politics continues to decline.

These findings raise questions about what being a citizen means. From a theoretical conceptualisation of citizenship, it is difficult to make sense of why interest in politics of immigrants who later acquire citizenship is significantly lower than for those who do not and why it continues to drop thereafter. Moreover, this finding is in contrast with evidence from other country contexts for which there is a positive association between political engagement and citizenship acquisition (e.g. Kesler and Demireva Citation2011). However, by considering that the average native citizen is not very interested in politics and does not participate in Britain’s political life, I argue that low interest in politics is an indication of integration, rather than marginalisation. I also suggest that the further decline in interest in politics may signal disillusionment with a political narrative that excludes immigrants irrespective of their citizenship status and fails to recognise their status and identity as British nationals.

This raises methodological and conceptual questions, both for researchers and for policy makers. Firstly, as political disaffection is high in most Western countries, how far does it make sense to regard political engagement as a defining features of citizenship? Secondly, when we study immigrant populations, what reference group should we compare them to, the ideal or the real? This last question is directed to policy makers as much as researchers. Policy makers dictate conditions for naturalisation, including a test that asks questions that most native British people are unlikely to know the answer to. The 3000 facts test-takers are expected to know, include about 278 historical dates, the height of the London Eye and the number of elected representatives in each regional assembly, for example. For researchers, it is important to be mindful that the choice of a comparison-group against which we measure immigrants implies judgments of ‘successful’ and ‘failed’ integration on which we base notions of good citizenship (Bloemraad, Korteweg, and Yurdakul Citation2008).

In contrast, the link between citizenship and national identification that exists for natives, appears to exist for immigrants too. This is in line with cross-sectional evidence of a nexus, both in Britain and other European countries (Manning and Roy Citation2010; Platt Citation2014). However, by distinguishing between national identity before and after naturalisation, this study contributes to our understanding of the mechanisms behind this relationship. I argue that social recognition is an indispensable facet of identity formation and might explain why the immigrants who identify as British naturalise, and why their sense of identity continues to grow thereafter. This study also adds to the growing evidence that national identification tends to increase with time (Georgiadis and Manning Citation2013; Güveli and Platt Citation2011; Karlsen and Nazroo Citation2013). While we should not forget that other social representations, such as those used in the media and in everyday life, also affect immigrants’ identity, this finding suggests that citizenship is still a valuable marker of national identity. This should be a reassuring finding to those worried about first and second generations failing to embrace a British national identity (Cameron Citation2011). If citizens, who can vote and are permanent members of nation states, identify as nationals of the country they live in, they are more likely to feel committed to the political community for a common good, contributing to the social cohesion of the country (Calhoun Citation2002; Moran Citation2011).

More geographically fine-grained evidence is needed to investigate whether immigrants’ political engagement mirrors that of natives in different parts of the country. Studying other country contexts with longitudinal data, with particular attention to the variation in naturalisation policies, could also improve our understanding of the relationship between citizenship, political engagement and national identity.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (67.3 KB)Acknowledgements

I thank Prof. Lucinda Platt, Prof. Stephen Jenkins, the editor and anonymous reviewers for very helpful suggestions and feedback on this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 However, the British naturalisation rate, which takes account of the immigrant population size, is similar to the European average (around 2%) (Eurostat Citation2019).

2 An exception in the UK is Commonwealth and Irish citizens who have full voting rights in the UK.

3 Different routes to citizenship typically require six years of residence.

4 With the exception of ‘the importance of being British’ variable which is part of the ‘extra five minute’ questions, asked by design to a subsample of immigrants only.

References

- Bartram, David. 2019. “The UK Citizenship Process: Political Integration or Marginalization?” Sociology 53 (4): 671–688. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518813842.

- Bevelander, Peter, and Ravi Pendakur. 2011. “Voting and Social Inclusion in Sweden.” International Migration 49 (4): 67–92. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2010.00605.x.

- Bevelander, Pieter, and Justus Veenman. 2006. “Naturalization and Employment Integration of Turkish and Moroccan Immigrants in the Netherlands.” Journal of International Migration and Integration / Revue de L’integration et de La Migration Internationale 7 (3): 327–349. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-006-1016-y.

- Blinder, Scott. 2018. “Naturalisation as a British Citizen: Concepts and Trends.” Oxford. 2018. https://migrationobservatory.ox.ac.uk/resources/briefings/naturalisation-as-a-british-citizen-concepts-and-trends/.

- Bloemraad, Irene, Anna Korteweg, and Gökçe Yurdakul. 2008. “Citizenship and Immigration: Multiculturalism, Assimilation, and Challenges to the Nation-State.” Annual Review of Sociology 34 (1): 153–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc34.040507.134608.

- Brubaker, Rogers. 1994. Citizenship and Nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Butt, Sarah, and John Curtice. 2013. “British Social Attitudes : The 26th Report 1 Duty in Decline ? Trends in Attitudes to Voting.” In British Social Attitudes : The 26th Report. 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446212073.n1.

- Calhoun, Craig. 2002. “Imagining Solidarity: Cosmopolitanism, Constitutional Patriotism, and the Public Sphere.” Public Culture 14 (11): 147–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-14-1-147.

- Calhoun, Craig. 2007. “Nationalism and Cultures of Democracy.” Public Culture 19 (1): 151–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2006-028.

- Cameron, David. 2011. “PM’s Speech to the Munich Security Conference.” 2011. https://www.gov.uk/ government/speeches/pms-speech-at-munich-security-conference.

- Carens, Joseph H. 2000. Culture, Citizenship, and Community: A Contextual Exploration of Justice as Evenhandedness. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/0198297688.001.0001.

- Casey, Teresa, and Christian Dustmann. 2010. “Immigrants’ Identity, Economic Outcomes and the Transmission of Identity Across Generations.” The Economic Journal 120 (542): F31–F51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02336.x.

- Chiswick, Barry R, and Paul W Miller. 2008. “Citizenship in the United States: The Roles of Immigrant Characteristics and Country of Origin.” Ethnicity and Labor Market Outcomes 29 (3596): 91–130. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/S0147-9121(2009)0000029007.

- Dehejia, R. H., and S. Wahba. 2002. “Propensity Score Matching Methods for Non-Experimental Causal Studies.” Review of Economics and Statistics 84 (1): 151–161. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/003465302317331982.

- DeVoretz, D. J., and S. Pivnenko. 2008. “The Economic Determinants and Consequences of Canadian Citizenship Ascension.” In The Economics of Citizenship, edited by Bevelander Pieter and Don J. De Voretz, 22–62. Malmö: Malmö University.

- Diehl, Claudia, and Michael Blohm. 2003. “Rights or Identity? Naturalization Processes Among Labor Migrants in Germany.” International Migration Review 37 (1): 133–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00132.x.

- Duveen, G. 2001. “Representations, Identities, Resistance.” In Representations of the Social: Bridging Theoretical Traditions, edited by Kay Philogène, and Gina Deaux, 257–270. Malden: Blackwell.

- Eurostat. 2019. “Acquisition of Citizenship Statistics.” 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Acquisition_of_citizenship_statistics#EU-28_Member_States_granted_citizenship_to_825.C2.A0400_persons_in_2017.

- Favell, Adrian. 2013. “The Changing Face of ‘Integration’ in a Mobile Europe Perspectives on Europe.” Perspectives on Europe 43 (1): 53–58. www.adrianfavell.com.

- Fougère, Denis, and Mirna Safi. 2008. “The Effects of Naturalization on Immigrants’ Employment Probability (France, 1968-1999).” IZA Discussion Papers, no. 3372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0042-7092.2007.00700.x.

- Galston, William A. 2001. “Political Knowledge, Political Engagement, and Civic Education.” Annual Review of Political Science 4 (1): 217–234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.4.1.217.

- Georgiadis, Andreas, and Alan Manning. 2013. “One Nation Under a Groove? Understanding National Identity.” Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 93: 166–185. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2012.10.013.

- Glazerman, Steven, Dan M. Levy, David Myers, and David Mye. 2003. “Nonexperimental Versus Experimental Estimates of Earnings Impacts.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 589 (1): 63–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716203254879.

- Güveli, Ayşe, and Lucinda Platt. 2011. “Understanding the Religious Behaviour of Muslims in the Netherlands and the UK.” Sociology 45 (6): 1008–1027. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038511416165.

- Heath, A., S. D. Fisher, G. Rosenblatt, D. Sanders, and M. Sobolewska. 2013. The Political Integration of Ethnic Minorities in Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heath, A., and J. Roberts. 2008. British Identity: Its Sources and Possible Implications for Civic Attitudes and Behaviour. London: Ministry of Justice. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk.

- Helgertz, Jonas, Pieter Bevelander, and Anna Tegunimataka. 2014. “Naturalization and Earnings: A Denmark–Sweden Comparison.” European Journal of Population 30 (3): 337–359. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-014-9315-z.

- Hidi, Suzanne, and K. Ann Renninger. 2006. “The Four-Phase Model of Interest Development.” Educational Psychologist 41 (2): 111–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_4.

- Hill, J., and J. P. Reiter. 2006. “Interval Estimation for Treatment Effects Using Propensity Score Matching.” Statistics in Medicine 25 (13): 2230–2256. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.2277.

- Ho, D., K. Imai, G. King, and E. Stuart. 2007. “Matching as Nonparametric Preprocessing for Reducing Model Dependence in Parametric Causal Inference.” Political Analysis 15: 199–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpl013.

- Hopkins, Nick, and Leda Blackwood. 2011. “Everyday Citizenship: Identity and Recognition.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 21 (3): 215–227. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1088.

- House of Commons Library. 2017. “Turnout at Elections.” 2017. https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-8060%23fullreport.

- Just, Aida, and Christopher J. Anderson. 2012. “Immigrants, Citizenship and Political Action in Europe.” British Journal of Political Science 42 (03): 481–509. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123411000378.

- Kahanec, Martin, and Mehmet Serkan Tosun. 2009. “Political Economy of Immigration in Germany: Attitudes and Citizenship Aspirations.” International Migration Review 43 (2): 263–291.

- Karlsen, S., and J. Y. Nazroo. 2013. “Influences on Forms of National Identity and Feeling ‘at Home’ among Muslim Groups in Britain, Germany and Spain.” Ethnicities 13 (6): 689–708. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812470795.

- Kesler, Christel, and N. Demireva. 2011. “Social Cohesion and Host Country Nationality Among Immigrants in Western Europe.” In Naturalisation: A Passport for the Better Integration of Immigrants? 209–235. Paris: OECD. doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264099104-11-en.

- Knies. 2018. “Understanding Society: Waves 1-7, 2009-2016 and Harmonised BHPS: Waves 1-18, 1991-2009, User Guide.” Institute for Social and Economic Research; University of Essex. Colchester.

- Koopmans, Ruud. 2013. “Multiculturalism and Immigration: A Contested Field in Cross-National Comparison.” Annual Review of Sociology 39 (1): 147–169. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145630.

- Kymlicka, Will, and Wayne Norman. 1994. “Return of the Citizen: A Survey of Recent Work on Citizenship Theory.” Ethics 104 (2): 352–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/293605.

- Leal, David L. 2002. “Political Participation by Latino Non-Citizens in the United States.” British Journal of Political Science 32 (2): 353–370. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123402000145.

- Levin, Ines. 2013. “Political Inclusion of Latino Immigrants.” American Politics Research 41 (4): 535–568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X12461438.

- Manning, Alan, and Sanchari Roy. 2010. “Culture Clash or Culture Club? National Identity in Britain.” The Economic Journal 120 (542): F72–F100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2009.02335.x.

- Mazzolari, Francesca. 2009. “Dual Citizenship Rights: Do They Make More and Richer Citizens?” Demography 46 (1): 169–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.0.0038.

- Moran, Anthony. 2011. “Multiculturalism as Nation-Building in Australia: Inclusive National Identity and the Embrace of Diversity.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 34 (12): 2153–2172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.573081.

- Phillips, Miranda, and Ian Simpson. 2015. “Disengaged and Disconnected? Trends in Attitudes Towards Politics.” In British Social Attitudes, the 32 Report. http://www.

- Picot, Garnett, and Feng Hou. 2011. “Divergent Trends in Citizenship Rates Among Immigrants in Canada and the United States.” Statistics Canada. Ottawa. doi:https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2012582.

- Platt, Lucinda. 2014. “Is There Assimilation in Minority Groups’ National, Ethnic and Religious Identity?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (1): 46–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.808756.

- Pogonyi, Szabolcs. 2019. “The Passport as Means of Identity Management: Making and Unmaking Ethnic Boundaries Through Citizenship.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (6): 975–993. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440493.

- Prabhat, D. 2018. Britishness, Belonging and Citizenship: Experiencing Nationality Law. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling Alone : The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Reeskens, Tim, and Matthew Wright. 2013. “Nationalism and the Cohesive Society.” Comparative Political Studies 46 (2): 153–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012453033.

- Russo, Silvia, and Håkan Stattin. 2017. “Stability and Change in Youths’ Political Interest.” Social Indicators Research 132 (2): 643–658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1302-9.

- Sales, R. 2010. “What Is ‘Britishness’, and Is It Important?” In Citizenship Acquisition and National Belonging, edited by Gideon Calder, Phillip Cole, and Jonathan Seglow, 123–140. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schafer, Joseph L., and Joseph Kang. 2008. “Average Causal Effects From Nonrandomized Studies: A Practical Guide and Simulated Example.” Psychological Methods 13 (4): 279–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014268.

- Schlozman, Kay Lehman, M. Kent Jennings, and Richard G. Niemi. 1982. “Generations and Politics: A Panel Study of Young Adults and Their Parents.” Political Science Quarterly 97 (4): 712. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2149815.

- Simonsen, Kristina Bakkær. 2017. “Does Citizenship Always Further Immigrants’ Feeling of Belonging to the Host Nation? A Study of Policies and Public Attitudes in 14 Western Democracies.” Comparative Migration Studies 5 (3).

- Sindic, Denis. 2011. “Psychological Citizenship and National Identity.” Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology 21 (3): 202–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.1093.

- Smith, Tom W, and Lars Jarkko. 1998. “National Pride: A Cross-National Analysis.” National Opinion Research Center: University of Chicago., no. 19. http://gss.norc.org/Documents/reports/cross-national-reports/CNR19 National Pride - A cross-national analysis.pdf.

- Soysal, Yasemin Nuhoğlu. 2000. “Citizenship and Identity: Living in Diasporas in Post-War Europe?” Ethnic and Racial Studies 23 (1): 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315260211.

- Stewart, E., and G. Mulvey. 2011. “Becoming British Citizens? Experiences and Opinions of Refugees Living in Scotland.” Glasgow. http://www.scottishrefugeecouncil.org.uk/assets/0000/1460/Citizenship_report_Feb11.pdf.

- Street, Alex. 2017. “The Political Effects of Immigrant Naturalization.” International Migration Review 51 (2): 323–343. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12229.

- Stuart, Elizabeth A. 2010. “Matching Methods for Causal Inference: A Review and a Look Forward.” Statistical Science 25 (1): 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1214/09-STS313.

- University of Essex. 2017. “ Understanding Society: Waves 1-6 [Data Collection],” Issued 2017. doi:https://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-6614-12.

- Vink, Maarten Peter, Tijana Prokic-Breuer, and Jaap Dronkers. 2013. “Immigrant Naturalization in the Context of Institutional Diversity: Policy Matters, But to Whom?” International Migration 51 (5): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12106.

- Waldinger, Roger, and Lauren Duquette-Rury. 2016. “Source: RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation.” The Russel Sage Foundation of the Journal of the Social Sciences 2 (3): 42–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2016.2.3.03.

- Yang, Philip Q. 1994. “Explaining Immigrant Naturalization.” International Migration Review 28 (3): 449–477. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/019791839402800302.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2006. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00313220600769331.