ABSTRACT

In this Special issue, we focus on temporary migrants as an important and often overlooked demographic in urban areas around the world. We demonstrate through empirical evidence that these migrants experience oscillations in precarity over time and that these fluctuations are mediated and better understood through a sensitivity to different scales and scalar processes. Most migration policies are created by national governments that privilege certain categories of migrants (such as high-skilled professionals or international students) over others (such as low-skilled or asylum seekers). However, the lived experience of many temporary migrants plays out in the households, neighbourhoods, and cities in which they reside and work. Temporary migrant precarity is also influenced by policies and practices shaped by local urban governments and civil society. Thus, temporary migrants are subject to intersecting and varied levels of temporal and scalar precarity, often compounded by personal and social attributes. Finally, we demonstrate that many temporary migrants employ individual and collective agency to resist their categorisation as disposable and transitory workers.

We are the precarious, the flexible, the temporary, the mobile. We’re the people that live on a tightrope, in a precarious balance, we’re the restructured and outsourced, those who lack a stable job, and those who are overexploited … We’re just like you: contortionists of flexibility.Footnote1

This special issue is concerned with the precarity of temporary migrants and how this precarity intersects with urban life and space. Precarity is characterised by a status that is temporary, uncertain, and restrictive in terms of mobility and benefits (Anderson Citation2010; Standing Citation2011; Hira-Friesen Citation2018; Strauss and McGrath Citation2017). It can also result in exploitative employment conditions (Anderson Citation2010; Butler Citation2012). Precarity is not a fixed status, and most migrants experience oscillations in their levels of precarity over time and through space. Migrants themselves find ways to manage their precarity, and as the opening quote suggests, may become ‘contortionists of flexibility’ in doing so. As one contributor to this special issue argues ‘Heterogeneous and multidirectional flows mean people move in increasingly diverse ways, migration is no longer conceived as a one-way linear flow leading to settlement and integration’ (Désilets Citation2021).

We, therefore, investigate the scalar and temporal aspects of precarity as experienced by a wide range of temporary urban migrants: from low to high-skilled, international students, asylum seekers and refugees to name a few. Cities receive the majority of the world’s migrants (Bravo Citation2018), either through internal migration or international migration. These urban settings are not mere backdrops but generative spaces that influence levels of precarity (Nicholls and Uitermark Citation2016). The contributors in this special issue, however, have strategically used distinct scales of analysis (such as a household, neighbourhood, or judicial boundary) to better understand migrant precarity. Cities are also the settings where multiple forms and levels of precarity intersect and overlap; where migrants engage in place-based citizenship (denizenship) through residence and localised economic, social, cultural and political contributions even when they are not considered permanent settlers or citizens (Komine Citation2014; Collins Citation2018). Discrete spaces within cities such as neighbourhoods, plazas, university campuses, schools, places of work, worship, and play are all possible settings of contact between migrants and native-born. It is in such spaces and localities that conflict about who belongs in the city and under what conditions, may erupt into a discourse of crisis and/or practices of intentional inclusion. Nina Glick Schiller and Ayse Caglar contend that the migration literature says very little ‘about the relationship of migrants and cities' which is a gap that the essays in this volume engage with regards to temporary migrants (Citation2011, 2).

In an era when many countries are turning to work arrangements that preclude long-term settlement and citizenship, precarity among temporary migrants is an urgent concern for the migrants themselves as well as the localities in which they settle. As Cooke, Wright, and Ellis (Citation2018) argue in a recent perspective on the mobility transition concept,

unskilled immigrant workers, and perhaps the skilled too, may find their mobilities and rights of residence in destination countries even more tightly constrained going forward as states aim to expand temporary visa guest-worker programmes as substitutes for their growing reluctance to accept permanent migration (Citation2018, 519)

Temporariness begins with the terms of entry, conditions that assert the length of stay, kinds of work and even mobility from job to job. Yet temporariness as a label has pernicious social consequences, categorising large groups of urban dwellers as less attached to a locality due to the ‘termed’ conditions of their stay (Anderson Citation2010). Temporal concerns are also influenced by the age of the migrants, especially the distinctions between children, youth, and adults and how the receiving destination processes and receives such newcomers based on their age and gender. Temporality also illuminates the time of day or week that migrants engage with urban spaces and other residents in more or less restricted ways. These ephemeral moments can lead to a heightened sense of freeing or belonging as well as confinement and exclusion (Lobo Citation2021; Tan Citation2021).

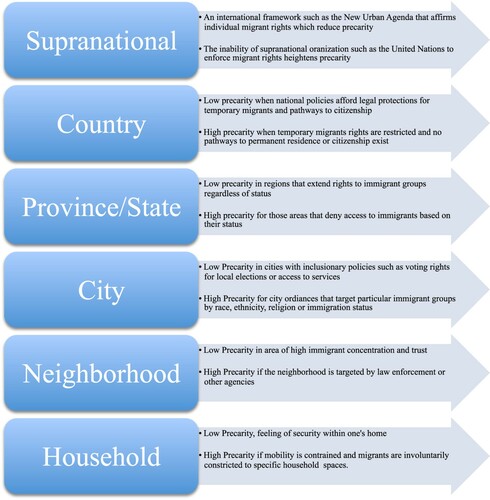

We contend that a sensitivity to different scales and scalar processes lends itself to a more nuanced understanding of migrant precarity. Precarity is experienced at the intimate scale of the human body but also it is influenced by policies determined by the nation-state or supranational entities such as the European Union, MercoSur or the United Nations. At the same time, there are divergent strategies between local and national governments as to the implementation of policies towards migrants, with ramifications for reception, inclusion/exclusion, integration and precarity. Consideration of diverse scales grounds the temporary migrant experience and underscores the localised interactions and encounters newcomers experience, the landscapes they help create and the institutions they interact with.

As argued by Panizzon and van Riemsdijk (Citation2019), at times a crisis mentality towards migration leads to complex governance dynamics in which ‘levels of policy-making interact, conflict, or disengage' in ways that require deeper exploration (Citation2019, 2). Such conflicts in governance are readily highlighted in urban settings, where the de facto experience of inclusion and livelihood comes into conflict with the de jure reality of conditional status imposed by other levels of governance.

In terms of global governance, the United Nations endorsed the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration in 2018 with the intention of improving the governance of migration, reducing migrant vulnerability, and strengthening the potential for migrants’ contributions to sustainable development (United Nations Citation2018). With specific regard to cities, the New Urban Agenda (NUA) endorsed in 2016 by the United Nations underscores the relationship between cities, migrants, and human rights (United Nations Citation2017). A key objective of the NUA is to reduce various forms of discrimination experienced by all categories of urban migrants, regardless of their migration status. Discrimination, which may be in the form of limited access to housing, legal employment, health care and education, is intertwined with the precarity that temporary migrants face. This stated normative goal, however, is difficult to achieve due to enforcement challenges at various scales.

Acknowledging that all those living within a city are vital to its social reproduction and fabric echo earlier concerns embedded in the rights to the city and social justice literatures (Fainstein Citation2011; Harvey Citation2009; Mitchell Citation2003; Wills et al. Citation2010; Glick Schiller and Caglar Citation2011). We recognise that urban migrants are imbricated in a complex web of legal policies and socio-economic processes that operate at various scales. But migrants are also actors who exercise agency in shaping a diverse range of social practices and spaces in cities.

Four research questions guide this exploration of the intersection of precarity, temporary migrant status and cities. The essays in this volume collectively explore these questions, although any individual contribution may not address all of them.

How does precarity inform our understanding of temporary migration and its effects on cities and the migrants themselves?

How does migrant precarity shift through space and across multiple scales?

How do conditions of entry and particular migrant characteristics impact the experience of precarity over time?

How do cities influence precarity and how does precarity influence cities?

Precarity and temporary migrants

Development scholar Standing (Citation2011) defined the precariat as populations who rely on money wages, often from temporary or flexible work, without any non-wage benefits or income security. He noted the relationship between present-day migration regimes and the creation of precarious labour, including low-skilled temporary migrant workers. Immigration policies and labour laws in migrant receiving countries, coupled with the worker’s immigration status often allow for the systemic exploitation of temporary migrant workers (Anderson Citation2010; Lewis et al. Citation2015). Butler (Citation2012) underscores the idea that precarity is not self-determined but an imposed condition of insecurity in both life and work. The precarisation of labour, which has been associated with neoliberal economic policies, leads to uncertainty of employment and the increasing normalisation of this unpredictability (Rachwal Citation2017). Lorey (Citation2015) notes that flexibility of labour, although often couched in terms of increasing freedoms, often leads to new cycles of exploitation, with effects in economic, social, cultural and corporeal realms. Thus precarity is experienced not simply in economic terms, but results in other kinds of vulnerabilities as well.

The most vulnerable among the precariat are migrants lacking a recognised legal status in the countries in which they live. Referred to as ‘un-citizens' (Nash Citation2009), even when they are able to obtain work, these migrants are often subjected to substandard working conditions, exploitation by employers who underpay or withhold wages, forced overtime as well as long and erratic working hours. These migrants are also more likely to be exposed to occupational hazards that have impacts on long term physical, mental and emotional health (Preibisch and Otero Citation2014).

Since the 1990s, according to Donato and Gabaccia, ‘ … women travelling as part of temporary labour recruitment schemes (have) become more common' (Donato and Gabaccia Citation2015, 113). In particular, the number of females (both married and unmarried) migrating to do reproductive work in domestic and institutional settings increased even in the context of more restrictive migration environments (Donato and Gabaccia Citation2015). Women employed as overseas contract workers, may be subject to ‘triple discrimination' when their statuses as temporary migrants, as females and as precarious workers intersect. Those who work in unregulated low-skill sectors such as domestic work, elder and child care, and commercial sex work are especially vulnerable, and could additionally face restrictions in their spatial mobility in the cities in which they live (Piper Citation2009; Vosko Citation2010; Yeoh and Huang Citation2010). There is even a growing literature that recognises the particular vulnerabilities of children and youth as part of these irregular and/or temporary migrant populations in cities (Allterton Citation2018; Menjívar and Perreira Citation2019).

Countries increasingly rely on temporary (and irregular) migrants to meet labour needs, offering temporary work visas over permanent residence even for highly skilled labour (Boese and Macdonald Citation2017). Thus, high-skilled migrant workers may find themselves subjected to precarious employment or become involved in ‘gig work' that is uncertain both in terms of tenure and income. Their precarity may be witnessed in uncertain employment prospects, the quality of the jobs they take, their earnings and lack of job security. In her study of high-skilled immigrants in Canada, Hira-Friesen (Citation2018) notes that recent immigrants are more likely to be engaged in temporary and involuntary part-time work than their Canadian-born counterparts or even more established immigrants. Even asylum seekers, who are often highly skilled, live in extremely precarious states, and may be in limbo for years before their cases are decided, even though they can add much to the economies of the urban areas in which they live (Jacobsen Citation2006). Viewing migrants as ‘temporary guests’ rather than as future citizens may offer economic benefits to urban jurisdictions but this also incurs social challenges in terms of how cities functionally include individuals who are labelled temporary but are, in fact, long-term urban residents (Price and Benton-Short Citation2008; Price and Chacko Citation2012).

Growing numbers of international students also make up the increase in temporary migrants. According to UNESCO (Citation2019), about 5.3 million students were enrolled in institutions of tertiary education outside their country of citizenship. International students may experience ‘extended precarity' as they seek to convert their tenuous student visa status into a more stable position that allows them to live and work in a country after the completion of their studies. In many Western countries, students may obtain practical training for a limited period of time after their course of study and even be absorbed into the workforce if they have the requisite skills and training, while in other countries they are required to leave shortly after graduation. However, the desire for a more permanent legal standing also makes students more vulnerable to labour exploitation in receiving countries (Robertson Citation2015; Thomas Citation2017; Maury Citation2017). Student experiences in the country, city and the wider community outside of campus may be constrained by visa status, resources, fluency in the culture and language of the host country, and limited avenues for inclusion (Chacko and Sojo Citation2016).

The urge to control migration has led to a proliferation of migration classifications in terms of entry and stay, many of which are predicated on the idea of temporariness. In the United States since the 1990s, new categories of temporary migrants have expanded and include H1-B (skilled worker) visas, Temporary Protected Status (TPS), Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) and Unaccompanied Migrant Children (UMC). Labels such a TPS, DACA and UMC may confer quasi-legal non-immigrant status but seldom provide a path to citizenship, resulting in an unstable situation of ‘liminal legality' (Menjivar Citation2006), a state of legal limbo that could be unevenly applied to different family members and that could be overturned by new administrations. For example, in September 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the U.S. government would rescind the DACA programme. This effectively reversed a programme that had been in existence for five years and gave undocumented youth the right to work legally, as well as safeguards from deportation. Similarly, since 1990, the U.S. government offered Temporary Protected Status (TPS) to migrants from certain countries who were fleeing war and armed conflict, environmental disaster and other extenuating conditions. TPS allowed these persons to reside and work in the United States until it was safe for them to return. In 2018, however, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security ended TPS for migrants from El Salvador, Haiti, Nicaragua and Sudan, making them ineligible to stay legally beyond deadlines given by the government despite many of them having lived in the United States for decades (USCIS Citation2019).

We acknowledge that immigration has become an especially divisive issue, as highlighted in 2016 by the United Kingdom ‘Brexit’ vote to leave the European Union and the election of Donald Trump in the United States. In both election campaigns, anti-immigrant sentiments were pervasive in the political discourse. In particular, the Trump Administration’s policy of wall-building, zero-tolerance, reduced legal migration, and bans on particular origin countries and refugees have been some of the most strident anti-immigration policies in nearly a century (Chishti, Pierce and O'Connor Citation2019). The politicalisation of migration and migrants into a discourse of ‘crisis’ is driving many countries away from policies that offer permanent residence or citizenship to newcomers and towards policies of temporariness, precarity or outright exclusion. Examples of this are numerous and from a wide range of countries. From the building of a wall between India and Bangladesh, denaturalising Haitians in the Dominican Republic, Australia’s Operation Sovereign Borders, or challenging the citizenship of the Windrush generation of Caribbean settlers in the United Kingdom. Exclusionary regimes based on resistance to settlement and/or citizenry, and limitation of movement for those allowed to enter, pose serious challenges to the basic human right of mobility and increase the level of precarity in the lives of all migrants.

Scalar and temporal dimensions of precarity

Scale and time have profound impacts on the migrant experience, and as such are fundamental when investigating precarity. Collectively, we understand scale as socially constructed and we concur with Marston’s (Citation2000) argument for the need to consider the demands of social reproduction and consumption when addressing the socio-political impacts of scale on migration. When one considers temporary migrants engaged in domestic labour, the linkages to social reproduction are obvious. Yet at the intimate level of the household, where migrants engage in ‘care work’ and may even be considered part of the family, limits to their spatial mobility are regularly imposed as to where they can sleep, places they can visit, or even if they can leave the house at all.

Our intent is to unpack the interconnecting spatialities of scale in the lives of migrants living in cities. We are not limited to a singular scale; rather, we share the view of Jones et al. (Citation2017) that processes of scalar production are central to complex spatial differentiations that temporary migrants experience. In this sense, scalar (as opposed to a fixed scale) suggests not simply a hierarchical continuum but also the possibility of jumping scale (Smith Citation1992), for example, from the household to the state, as in the case of many contracted migrant labourers. Most migration events involve movement across multiple scales that are interconnected. It is telescoping nature of scale that is socially constructed and embedded with power relations that informs our understanding of migrant precarity.

The contributors to this volume were asked to consider how scalar dimensions affect the temporary migrant experience. At some scales (such as a recreation centre or park) migrants express feelings of wholeness, belonging or inclusivity. Yet shifting to another scale, experiences of displacement or vulnerability may intensify. As Lobo (Citation2021) observes from her research in Darwin, Australia, experiences of refugees and asylum seekers oscillate between precarity and freedom depending upon scale and/or locality. Locating the sites and scales of precariousness and highlighting ways in which these uncertainties are addressed or mitigated via grass-roots initiatives, humanitarian organisations, and advocacy groups is an important contribution of the essays in this volume.

Exploring the neighbourhood scale, provides an opportunity to appreciate the role of migrants in remaking neighbourhoods such as Montreal’s Mile End (Désilets Citation2021) or the Basmane neighbourhood in Izmir, Turkey (Oner, Durmaz-Drinkwater and Grant Citation2021). In these dynamic neighbourhoods, researchers observe competing scales of governance interacting with local institutions and individuals. In the case of the high-skilled migrants in Montreal’s Mile End, they are key actors in the remaking of this multicultural hub of high tech professionals into a gentrified hipster zone of consumption (Désilets Citation2021). The differentiation of scale by the migrants themselves is also acute, especially when their status is highly precarious. Undocumented youth in the U.S. with DACA described areas that felt more secure and less secure in their daily commutes (Price and Rojas Citation2021). In Dongguan, China, a destination for many temporary workers, Tan (Citation2021) elaborates on the vitality of the public square for migrants’ sense of belonging and engagement. Similarly, Chacko (Citation2021) notes that international students studying for a bachelor’s degree in Singapore feel a sense of belonging to the university campus but have a more tenuous connection to other parts of the city.

Scalar divisions can be meaningful, arbitrary or insignificant when considering migrant precarity but this volume underscores the often overlooked role of scale in the migrant experience. In much migration literature, the territorial state is the scale of convenience with a focus on immigrants crossing state boundaries (Castles, de Haas, and Miller Citation2014). Governments of sovereign states have a vested interest in governing borders and deciding who should enter, yet the assumption that the same set of laws and selection processes are uniformly applied throughout the territorial state for different migrant types is readily challenged (Mountz Citation2010; Lobo Citation2016; Williams and Mountz Citation2018; Caponio and Jones-Correa Citation2018; Agnew Citation2019). When considering sub-state jurisdictions – neighbourhoods, cities, towns, counties – it becomes clear that particular scalar units impact migrants differently (Walker and Leitner Citation2013; Walker Citation2014). Consider the practice of granting asylum to unaccompanied minors in the United States (Blue et al. Citation2021). The authors demonstrate that a determining factor in receiving asylum is the federal court district to which a case was assigned, with California and especially San Francisco being far more generous than courts in Texas or states in the southern U.S. Similar regional variations were observed when federal deportation decisions were compared (Price and Breese Citation2016). This underscores the idea that if different scales are not considered, then these differentiations of precarity go unnoticed.

suggests ways in which scale may affect migrant precarity. At the household level, a temporary migrant may feel relatively safe and secure, and thus experience low precarity. Yet if a migrant works in a household where employer abuse occurs, then precarity could be quite high. Similarly, in neighbourhoods where immigrant populations are concentrated and social networks are dense, daily precarity could be low. However, in neighbourhoods where there are heightened tensions between native born and migrants, or a particular migrant group is singled out on account of their race, religion or country of origin, then precarity increases. Cities and entire metropolitan areas also influence migrant precarity. There are cities that actively develop policies aimed at inclusion, in which case precarity is lessened as seen in sanctuary cities in the United States (Delgado Citation2018). There are also unwelcoming cities, in which migrant services are limited or migrant populations are aggressively policed.

Probably more common are mixed practices of inclusion and exclusion, as geographers Walker and Leitner (Citation2013) demonstrated in their analysis of the variegated landscape of inclusionary practices in metropolitan Washington DC. Policies of sub-state jurisdictions, such as departments, provinces, and various administrative units may also impact precarity. In the United States, individual states differ in their interpretation of immigration enforcement and the extension of rights to individuals who are not authorised to remain in the U.S. but may have resided in a state for decades (Mathema Citation2018). These policy differences are pronounced and directly influence levels of precarity, as Blue et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate.

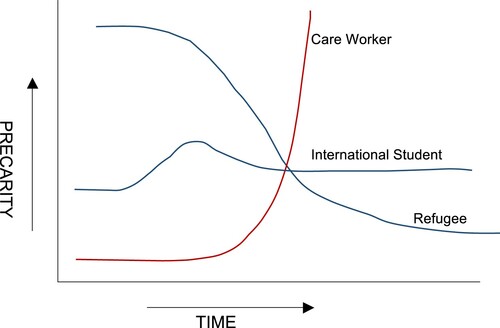

In addition to scalar considerations, most migrants experience oscillations in their levels of precarity over time. Migrant precarity fluctuates as a result of legal status, policy changes, age, physical abilities, and crisis-driven events that may produce waves of migrants. In particular, policy changes surrounding the conditions of entry or residence can increase or decrease precarity. For example, a contract labourer may legally work in a country for many years experiencing modest precarity, but if that worker becomes injured or pregnant, precarity is heightened if the contract is terminated and the migrant is told or forced to leave (Hennebry and Williams Citation2015; Yeoh Citation2006).

Considering precarity over time, in addition to scalar sensitivities, provides a more comprehensive understanding of the issues faced by temporary migrants. illustrates possible scenarios of how three temporary migrants – an asylum seeker, international student and care worker – might encounter precarity over time. A migrant might enter a city with extremely high precarity as an asylum seeker and attempt to transition to a permanent status. If asylum is granted, then precarity could markedly decline but if asylum is rejected, precarity increases. In contrast, an international student may begin her studies with moderate precarity because of the conditional aspects of her visa tied to one school, a time frame, and continued academic progress. Upon graduation, precarity might increase as the student seeks to find employment and/or transition to another type of visa. Precarity may then decline if the student’s migration status is adjusted or if she returns to her country of origin. Lastly, a care worker placed in a setting where she is treated well by her employer may enter with relatively low precarity, although if her physical condition changes (such as through pregnancy) then her precarity could markedly increase, leading to her removal from the job and even the country.

Figure 2. A hypothetical illustration of the shifting intensity of precarity over time by three migrant types.

The world’s sovereign states create categories of migrant entry and temporariness that can be hostile, indifferent, or provide protection. Depending on the country in question, these laws can result in higher or lower precarity for particular migrant groups as well as migrants in general. Lastly, intergovernmental bodies such as the United Nations or the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) endorse the universal declaration of human rights which acknowledges the human right to move within one’s territorial state, to leave one’s territorial state, and the right to seek asylum from persecution in another country. In theory, such universal rights exist to lower the precarity of migrants but they are difficult to enforce. These same international bodies are also criticised for reinforcing precarity by aligning themselves with the interests and agendas of migrant-receiving developed states who are often their financial sponsors (Geiger and Pécoud Citation2014; Pécoud Citation2018).

The intersection of cities, precarity and migrants

This special issue explores how cities influence the precarity of temporary migrants and how precarity among temporary residents influences cities. Cities, particularly global cities, are characterised by inequality and precarity not just in the economic realm, but also in access to housing and social benefits (Jordan Citation2017). Collins (Citation2011) review of migration in the Asia-Pacific cities of Singapore, Taipei, Tokyo and Seoul notes an increasing reliance on temporary migration regimes that aim to ‘use and discard’ migrant labour while prohibiting the development of social roots. He observes, ‘the presence of significant numbers of temporary migrants also has significance for housing, transport and public spaces, and their presence can lead to both passing and more long-term transformations of the urban built environment' (Collins Citation2011, 322).

What does it mean for a city to have large numbers of temporary migrants in various states of precarity? Some extreme examples are found in the gleaming and rapidly growing Persian Gulf cities of Dubai, Doha, Riyadh, and Kuwait City where the majority of the urban residents are temporary migrants with minimal rights and limited inclusion or integration. Low skilled temporary workers often live in labour camps in cramped conditions and have little if any interaction with the city beyond their places of work and stay. Temporary migrants who received the lowest pay also faced the greatest deprivations in terms of basic amenities and personal mobility, their precarity heightened because employers often confiscate and hold on to their passports for the entirety of their stay (Gardner et al. Citation2013). In such cities, temporary migrants are fundamental to the economic growth and development of urban localities but they are intentionally not considered as belonging to these settings in any meaningful way. Such urban denizens are excluded from political participation (such as voting, protesting, or organising) and are often banned from access to forms of education, housing, and pensions that are available to citizens.

The level of precarity experienced by migrants living in large urban centres, even within the same country, may vary considerably. In a study of worker precarity in seven Chinese regional urban centres, migrants working in Shanghai (a global city) were found to suffer less precarity than their counterparts in other regional urban centres such as Guangzhou, Wuhan and Harbin, indicating perhaps that globalisation allowed for greater institutionalisation and standardisation of inclusive labour regulations and practices (Sun and Chen Citation2017). However, even within global cities in China, the educational qualifications of the migrants could influence degrees of precarity, with high skilled migrants being less vulnerable than the low skilled (Sun and Chen Citation2017; Wang, Li, and Deng Citation2017). In Singapore, the presence of temporary workers on their day off in public spaces such as parks, open air spaces in ethnic enclaves and cultural conservation districts masks the lack of structural integration in the city. Additionally, the country’s laws distinguish between different kinds of temporary low-skilled workers. Singapore’s Employment Act lays down standard rules that govern the employment of male temporary workers who often work in construction and landscaping, but this protection does not extend to domestic workers, who are primarily female, thereby increasing the latter’s precarity within their workplace, the household (Yeoh Citation2006). In the United States measures to establish sanctuary cities or provide municipal forms of identification, such as the IDNYC for all residents in New York City, allows for inclusion and protection of migrants with irregular status in some cities but not others (Price Citation2015).

Articles in this special issue

The contributors to this special issue use a range of theoretical frameworks and empirical approaches to examine and analyse the scalar and temporal ramifications of precarity for temporary urban migrants. They investigate how precarity is experienced by individuals and groups in different urban settings, all the while aware of broader national contexts and global economic shifts. The localities considered include: Singapore, Dublin, Montreal, Dongguan (China), Darwin (Australia) Izmir (Turkey), Washington DC, and federal immigrant court boundaries within the United States (which vary in size from a single metropolitan area to several bordering states). The papers are grouped into three broad and overlapping categories based upon the status of these temporary migrants: (1) asylum seekers and refugees, (2) low skilled migrants, and (3) high skilled migrants (including international students). Each status group experiences varying degrees of precarity and integration, which change across scales and over time. By investigating how temporariness is embedded in migration regimes in a wide range of urban areas, we intentionally avoid specious distinctions between cities of the Global North and South.

Refugees and Asylum seekers often arrive in urban areas with varying levels of precarity. Asylum seekers experience high precarity due to limited rights and privileges and a tenuous legal status. Refugees arrive with permanent resident status, and therefore, less precarity, but even their experience of, and connections to the cities in which they live can be fraught with estrangement, marginalisation and exclusion if they are not formally resettled in a host community. Michele Lobo evaluates precarity engendered by statelessness, homelessness and privation as experienced by refugees and asylum seekers who are awaiting the regularisation of their status in the northern Australian city of Darwin. Using qualitative methods that include informal conversations, interviews, focus groups, participant photography and videos, Lobo discovers that the lives of these refugees and asylum seekers oscillate between freedom and precarity. Although these temporary migrants are disadvantaged in their socio-economic status, are housed in community detention facilities and are often unemployed or underemployed due to their limited right to work, they experience fleeting moments of freedom and connectedness. It is in the community centres where they interact with one another that they experience an evanescent ‘unfreezing' of precarity in their lives through participation in events centred around sports, cooking and communal eating.

Asli Ceylan Oner, Bahar Durmaz-Drinkwater and Richard J. Grant in their study of Syrian refugees living in the Basmane district of the city of Izmir in Turkey seek to understand how refugees negotiate and transform the built and cultural environments of the neighbourhoods in which they reside. These researchers use direct observation and media analysis to understand the lived experiences of precarity among refugees who have few rights and privileges. Despite their (un)settled lives, Syrian refugees built social ties with the city of Izmir through interactions with civil society, participation in the informal economy, and by making efforts to learn the local language and culture, thus making claims to urban space. The authors concentrate on the intra-relationships among place, refugees, and locals, seeking to contribute to the debate of how refugees produce differential pathways for adaptation and experiences of precarity. They conclude that a longer-term framework would facilitate the adaptation of refugees and their inclusion and integration in cities and city spaces.

Migrant youth from Central America crossing through Mexico to the United States face unusually dangerous circumstances during their journey as well as precarity when they request asylum in the United States of America. The contribution of Sarah Blue, Alisa Hartsell, Rebecca Torres and Paul Flynn considers how unaccompanied minors are processed in a federal system in which disparate outcomes are explained by strong place effects. Using administrative case data from over 232,000 unaccompanied migrant cases, the authors demonstrate that the location of the U.S. immigration court, as well as if a minor has legal representation, greatly influenced whether or not an unaccompanied minor received asylum. This regional disparity, and the increased role of local politics, produces uneven outcomes in which federal law fractures along the jurisdictional boundaries of immigration courts which are boundaries that are drawn for administrative purposes and should not influence outcomes. In terms of cities, certain courts located in major immigrant gateways such as San Francisco and New York City had much more favourable outcomes for asylum seekers.

Low skilled migrants often experience high levels of precarity and exploitation. Two papers that address low-skilled labour examine the social and spatial precarity of these migrants. Parreñas, Kantachote, and Silvey (Citation2021) offer a penetrating analysis of migrant domestic workers in Singapore; arguing that the temporary and restrictive conditions of entry are akin to indentureship and that such labour regimes would be better understood as ‘un-free’ rather than ‘free’ labour. They also introduce the concept ‘soft violence', which is the practice of cloaking the unequal relationship in domestic work via the cultivation of a relationship of ‘personalism' while simultaneously amplifying employers’ control of domestic workers. Empirically they draw from semi-structured interviews of employers, which reveal a range of attitudes but underscore the daily precarity and term-based restrictions these workers face. Singapore (as a city and a state) has created regulations to reduce the exploitation of household domestics, yet the researchers illustrate how precarity is amplified by restricted mobility within the household and across the city, along with debt bondage associated with financing the migrant’s travel from overseas. They conclude that many middle class families in cities around the world have become reliant upon temporary migrant labour to sustain household reproduction and living standards, all the while turning a blind eye to the subordinate, isolating, and precarious conditions of these same household residents.

Yining Tan offers a case study from Dongguan, China, where temporary migrant workers from the interior provinces are the economic backbone of this industrial city along the Guangzhou-Shenzhen economic corridor. In Dongguan, where most of the residents are registered as ‘temporary’ migrants under the hukou system, newcomers struggle for economic, social and spatial inclusion in a system that refuses to recognise permanence. Through participant observation and semi-structured interviews, Tan documents the spatial restrictions on these migrants as well as the significance of the public square in shaping social belonging and claiming urban space. Such spaces serve to integrate all residents of the city, and as the number and proportion of the city’s residents classified as temporary grows, research at this scale shows how temporary migrants are claiming certain ‘public’ urban spaces as their own.

Highly skilled migrants and international students are of interest to this research because the assumption is that they make up a population that is highly mobile and well educated and thus live less precarious lives as migrants. Gabrielle Désilets explores the concentration of high-tech temporary migrants in Montreal’s Mile End neighbourhood. Mile End attracts IT workers for the gaming, film, and AI industries who are drawn to this ‘hip’ neighbourhood that has been repurposed for the needs of the tech industry and the consumption patterns of its workers. Using an ethnographic approach, Désilets describes the experience temporary ‘middling migrants’ who often begin their migration journeys as college students, and then develop the skills and the desire to relocate globally as part of a skilled but middle-class workforce. In addition to exploring landscape changes brought by these newcomers, she addresses the tensions inherent between the needs for local civic engagement and place-based belonging in contrast with the transnational urban lifestyle that many of these migrants pursue. She questions the structure of global labour in which these temporary migrants are embedded. A structure marked by temporarily forcing migrants to live ‘in-between’ places, sometimes for several years. Never fully recognised, nor acting as political agents in the country of departure or of arrival, this migration has notable effects on urban local communities and on migrant’s perception of ‘integration’ and forms of identification.

Two of the articles in the special issue investigate precarity as experienced by international students who are in training to be high skilled workers. Gilmartin, Coppari, and Phelan (Citation2021) examine the intersections of legal, economic and personal precarisation and precarity among international students who are in Dublin, Ireland, to study language or obtain a degree. They find that the embodied experiences of precarity for this temporary migrant group, although laced with anxiety due to uncertain legal status and unclear future employment, is somewhat assuaged by hopes and promise. According to the authors, the ‘promising precarity' that the students simultaneously experience along with anxiety stems from small acts of resistance, organised activism and their full lives as social beings living in Ireland and strategising to stay on permanently in the country.

In her study of international students of Chinese and Indian descent majoring in STEM fields in baccalaureate programmes at a leading university in Singapore, Elizabeth Chacko investigates how these students’ emerging precarity affects their subjective well being and how they counter ideas of their inherent inassimilability through narratives of cultural belonging. Focus group discussions and structured interviews with the students reveal that as migrants who believe they are poised to enter the workforce in the receiving country, students experience precarity that emanates from an uncertain legal status as they finish their courses of study, which has ramifications for employability and employment. While uncertainty of prolonged stay often deters students from developing roots in the city, they have developed an affection for spaces (such as the university campus) within it and exhibit agency in diminishing their perceived precarity by positioning themselves as ‘locals' with an intimate knowledge of the city and Singaporean culture, and therefore, exemplars of future workers, permanent residents and even citizens.

Marie Price and Giancarla Rojas explore how college students with DACA status understand and navigate the built environment of metropolitan Washington in the context of oscillating precarity for themselves and their families. They position DACAmented college students as skilled migrants, because with DACA these undocumented youth attend college with in-state tuition and legally work. To understand the experience of temporariness they employ a spatial and visual approach, having six DACA holders engage in a participatory photo project as a means to visualise everyday life with and without DACA status. The photos underscore the ordinariness of their daily lives as well as strategic locations of safety and areas of avoidance. Given the uncertainty of retaining DACA status, these college students expressed a heightened sense of fear, even though they have felt safe for most of their lives within their suburban neighbourhoods.

Conclusion

By using case studies from East and Southeast Asia, North America, the Middle East, Australia, and Europe, the articles in this special issue provide empirical evidence of how precarity is experienced by temporary migrants in urban spaces at discrete and overlapping scales. There are different categories of temporary migrants, yet in each study, the precarity of migrant lives oscillates through time, across scale, and in particular localities. Precarity, as experienced by these migrants, is influenced by macro level factors such as fluctuating national regulations and policies, the vicissitudes of labour markets, changes in nuances of popular discourse on migration and migrants as well as personal and social characteristics such as age, gender, socio-economic class and even race/ethnicity and cultural characteristics in local settings. It is this attention to the temporal and scalar dimensions of precarity that ties the papers in this volume together. Migrant precarity is dynamic, and to fully understand the experiences of temporary migrants one needs to consider the nuanced effects of scale and time in addition to national policies and labour markets.

This special issue contributes to the literature on precarity in three important ways. Firstly, the issue explores the spatial and scalar dimensions of precarity for temporary migrants. The articles demonstrate that in any given urban space, different migrant populations may have access to varying localised sets of resources and are subject to distinct policies, and therefore, experience precarity in dissimilar ways. The papers also highlight variations of precarity at different scales within cities, ranging from the household and neighbourhood to the municipality or city. Secondly, the settings where these studies occur are also subjects of inquiry as these urban places provide the socio-political contexts for the migrant experience where local and national policies overlap and intersect. It is important to remember that cities are also being shaped, in ephemeral and enduring ways, by these (un)settled sojourners through their work and daily engagements. Thirdly, the research demonstrates how temporary migrants are employing individual and collective agency to resist their categorisation as disposable and transitory workers whose services are easy to cut and who are not worthy of being considered permanent residents or citizens. Many, including refugees and asylum seekers who are typically perceived as highly vulnerable, are able to create formal and informal spaces of inclusion within cities. Others offer new nomenclatures and classifications that demonstrate that they are denizens, fully immersed in the cities in which they live, study, and work.

While most studies of migrant precarity focus on legal precarity and its ramifications for temporary migrants, by demonstrating that precarity can shadow the status of all categories of temporary migrants, including the highly skilled, who are typically considered protected and secure, this special issue underscores the ways in which temporary migrants’ status is always in an uneasy state of ambiguity. Also, as the prevalence of temporary migrants grows throughout the world, this collection offers a more nuanced and empirically driven investigation of the consequences temporariness imposes across scales, over time and upon cities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 ‘Mayday, Mayday! Les precàries i precaris es rebel.len’, Manifiesto convocatoria Barcelona EuroMayDay 2004 https://marceloexposito.net/pdf/mayday_periodico.pdf

2 The United Nations Migrant Stock totals do not distinguish between temporary and more permanent conditions of migration. Yet many national policies and bilateral agreements stipulate temporary arrangements, especially the proliferation of temporary work visas for high skilled and low skilled migrants.

References

- Agnew, John. 2019. “Spatial Uncertainties of Contemporary Governance.” Territory, Politics, Governance 7 (4): 435–437. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2019.1663391

- Allterton, Catherine. 2018. “Impossible Children: Illegality and Excluded Belonging Among Children of Migrants in Sabah, East Malaysia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (7): 1081–1097. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1357464

- Anderson, Bridget. 2010. “Migration, Immigration Controls and the Fashioning of Precarious Workers.” Work, Employment and Society 24 (2): 300–317. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017010362141

- Bailey, Adrian, Richard Wright, Alison Mountz, and Ines Miyares. 2002. “(Re)producing Salvadoran Transnational Geographies.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 92: 125–144. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.00283

- Blue, Sarah A., Alisa Hartsell, Rebecca Torres, and Paul Flynn. 2021. “The Uneven Geography of Asylum and Humanitarian Relief: Place-Based Precarity for Central American Migrant Youth in the United States Judicial System.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4631–4650. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732588.

- Boese, Martina, and Kate Macdonald. 2017. “Restricted Entitlement for Skilled Temporary Migrants: The Limits of Migrant Consent.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (9): 1472–1489. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1237869

- Bravo, Jorge. 2018. Sustainable Cities, Human Mobility and International Migration. Report of the Secretary-General for the 51st session of the Commission on Population and Development (E/CN.9/2018/2).

- Butler, Judith. 2012. “Precarious Life, Vulnerability and the Ethics of Cohabitation.” Journal of Speculative Philosophy 26 (2): 134–151. doi: https://doi.org/10.5325/jspecphil.26.2.0134

- Caponio, Tiziana, and Michael Jones-Correa. 2018. “Theorising Migration Policy in Multi-Level States: The Multi-Level Governance Perspective.” Jounral of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (10): 1995–2010. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1341705

- Castles, Stephen, Hein de Haas, and Mark J. Miller. 2014. The Age of Migration: International Population Movements in the Modern World. 5th ed. New York: Guilford Press.

- Chacko, Elizabeth. 2021. “Emerging Precarity Among International Students in Singapore: Experiences, Understandings and Responses.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4741–4757. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732618.

- Chacko, Elizabeth, and Gloriana Sojo. 2016. “Spaces of Integration: International Students in a Global City.” In Chap. 22 in Race, Ethnicity and Place in a Changing America, edited by J. W. Frazier, E. L. Tettey-Fio, and N. F. Henry, Vol. 3, 335–343. Albany: SUNY Press.

- Chishti, Muzzafar, Sarah Pierce, and Allison O’Connor. 2019. Despite Flurry of Actions, Trump Administration Faces Constraints in Achieving Its Immigration Agenda. Policy Beat, April 25, 2019. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute.

- Collins, Francis L. 2011. “Transnational Mobilities and Urban Spatialities: Notes From the Asia-Pacific.” Progress in Human Geography 36 (3): 316–335. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511423126

- Collins, Francis L. 2018. “Desire as a Theory for Migration Studies: Temporality, Assemblage and Becoming in the Narratives of Migrants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 964–980. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384147

- Cooke, Thomas J., Richard Wright, and Mark Ellis. 2018. “A Prospective on Zelinsky’s Hypothesis of the Mobility Transition.” Geographical Review 108 (4): 503–522. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12310

- Delgado, Melvin. 2018. Sanctuary Cities, Communities and Organizations: A Nation at the Crossroads. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Désilets, Gabrielle. 2021. “Consuming the Neighbourhood? Temporary Highly Skilled Migrants in Montreal’s Mile End.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4705–4722. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732616.

- Donato, Katharine M., and Donna Gabaccia. 2015. Gender and International Migration. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Fainstein, Susan. 2011. The Just City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Gardner, Andrew, Silvia Pessoa, Abdoulaye Diop, Kaltham Al-Ghanim, Kien Le Trung, and Laura Harkness. 2013. “A Portrait of Low-Income Migrants in Contemporary Qatar.” Journal of Arabian Studies 3 (1): 1–17. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/21534764.2013.806076

- Geiger, Martin, and Antoine Pécoud. 2014. “International Organisations and the Politics of Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (6): 865–887. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.855071

- Gilmartin, Mary, Pablo Rojas Coppari, and Dean Phelan. 2021. “Promising Precarity: The Lives of Dublin’s International Students.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4723–4740. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732617.

- Glick Schiller, Nina, and Ayse Caglar. 2011. Locating Migration: Rescaling Cities and Migrants. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Harvey, David. 2009. Social Justice and the City. Athens: The University of Georgia Press.

- Hennebry, Jenna, and Gabriel Williams. 2015. “Making Vulnerability Visible: Medical Repatriation and Canada’s Migrant Agricultural Workers.” Canadian Medical Association Journal 187 (6): 391–392. doi: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141189

- Hira-Friesen, Parvinder. 2018. “Immigrants and Precarious Work in Canada: Trends, 2006–2012.” Journal of International Migration and Integration 19 (1): 35–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-017-0518-0

- Jacobsen, Karen. 2006. “Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Urban Areas: A Livelihoods Perspective.” Journal of Refugee Studies 19 (3): 273–287. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fel017

- Jones, I. I. I., John Paul, Helga Leitner, Sallie A. Marston, and Eric Sheppard. 2017. “Neil Smith’s Scale.” Antipode 49 (S1): 138–152. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12254

- Jordan, Lucy. 2017. Introduction: Understanding Migrants’ Economic Precarity in Global Cities.” Urban Geography 38 (10): 1455–1458. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1376406

- Komine, Ayako. 2014. “When Migrants Became Denizens: Understanding Japan as a Reactive Immigration Country.” Contemporary Japan 26 (2): 197–222. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/cj-2014-0010

- Lewis, Hannah, Peter Dwyer, Stuart Hodkinson, and Louise Waite. 2015. “Hyper-precarious Lives: Migrants, Work and Forced Labour in the Global North.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (5): 580–600. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514548303

- Lobo, Michele. 2016. “Geopower in Public Spaces of Darwin, Australia: Exploring Forces That Unsettle Phenotypical Racism.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 39 (1): 68–86. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1096407

- Lobo, Michele. 2021. “Living on the Edge: Precarity and Freedom in Darwin, Australia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4615–4630. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732585.

- Lorey, Isabell. 2015. States of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious. London: Verso.

- Marston, Sallie. 2000. “The Social Construction of Scale.” Progress in Human Geography 24 (2): 219–242. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/030913200674086272

- Mathema, Silva. 2018. What DACA Recipients Stands to Lose–and What States Can Do About It. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

- Maury, Olivia. 2017. “Student-migrant Workers.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 7 (4): 224–232. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/njmr-2017-0023

- Menjivar, Cecilia. 2006. “Liminal Legality: Salvadoran and Guatemalan Immigrants’ Lives in the United States.” The American Journal of Sociology 111 (4): 999–1010. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/499509

- Menjívar, Cecilia, and Krista M. Perreira. 2019. “Undocumented and Unaccompanied: Children of Migration in the European Union and the United States.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (2): 197–217. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1404255

- Mitchell, Don. 2003. The Right to the City: Social Justice and the Fight for Public Space. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Mountz, Alison. 2010. Seeking Asylum: Human Smuggling and Bureaucracy at the Border. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Nash, Kate. 2009. “Between Citizenship and Human Rights.” Sociology 43: 1067–1083. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038509345702

- Nicholls, Walter J., and Justus Uitermark. 2016. “Migrant Cities: Place, Power and Voice in the Era of Super Diversity.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (6): 877–892. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1126088

- Oner, Asli Ceylan, Bahar Durmaz-Drinkwater, and Richard J. Grant. 2021. “Precarity of Refugees: The Case of Basmane-İzmir, Turkey.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4651–4670. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732591.

- Panizzon, Marion, and Micheline van Riemsdijk. 2019. “Introduction to Special Issue: ‘Migration Governance in an Era of Large Movements: A Multi-Level Approach.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (8): 1225–1241. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1441600

- Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar, Krittiya Kantachote, and Rachel Silvey. 2021. “Soft Violence: Migrant Domestic Worker Precarity and the Management of Unfree Labour in Singapore.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4671–4687. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732614.

- Pécoud, Antoine. 2018. “What Do We Know About the International Organization for Migration?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (10): 1621–1638. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1354028

- Piper, Nicola. 2009. “Feminisation of Migration and the Social Dimensions of Development: the Asian Case.” Third World Quarterly 29 (7): 1287–1303. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01436590802386427

- Preibisch, Kerry, and Gerardo Otero. 2014. “Does Citizenship Status Matter in Canadian Agriculture? Workplace Health and Safety for Migrant and Immigrant Laborers.” Rural Sociology 79 (2): 174–199. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/ruso.12043

- Price, Marie. 2015. Cities Welcoming Immigrants: Local Strategies to Attract and Retain Immigrants in U.S. Metropolitan Areas in World Migration Report: Migrants and Cities: New Partnerships to Manage Mobility. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

- Price, Marie, and Lisa Benton-Short. 2008. Migrants to the Metropolis: The Rise of Immigrant Gateway Cities. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

- Price, Marie, and Derek Breese. 2016. “Unintended Return: U.S. Deportations and the Fractious Politics of Mobility for Latinos.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106 (2): 366–376.

- Price, Marie, and Elizabeth Chacko. 2012. “Migrant inclusion in cities: Innovative urban Policies and Practices.” Paper prepared for UN-Habitat and UNESCO.

- Price, Marie, and Giancarla Rojas. 2021. “The Ordinary Lives and Uneven Precarity of the DACAmented: Visualising Migrant Precarity in Metropolitan Washington.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4758–4778. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732619.

- Rachwal, Tadeusz. 2017. Precarity and Loss: On Certain and Uncertain Properties of Life and Work. Weisbaden: Springer Fachmedian Wiesbaden.

- Robertson, Shanthi. 2015. “Contractualization, Depoliticization and the Limits of Solidarity: Noncitizens in Contemporary Australia.” Citizenship Studies 19 (8): 936–950. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2015.1110286

- Smith, Neil. 1992. “Contours of Spatialized Politics: Homeless Vehicles and the Production of Geographical Scale.” Social Text 33: 55–81.

- Standing, Guy. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Strauss, Kendra, and Siobhán McGrath. 2017. “Temporary Migration, Precarious Employment and Unfree Labour Relations: Exploring the ‘Continuum of Exploitation’ in Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 78: 199–208.

- Sun, Zhongwei, and Jia Chen. 2017. “Global City and Precarious Work of Migrants in China: A Survey of Seven Cities.” Ûrban Geography 38 (10): 1479–1496. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1281056

- Tan, Yaning. 2021. “Temporary Migrants and Public Space: A Case Study of Dongguan, China.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4688–4704. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732615.

- Thomas, Susan. 2017. “The Precarious Path of Student Migrants: Education, Debt, and Transnational Migration among Indian Youth.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (11): 1873–1889. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1286970

- UNESCO. 2019. International Students – Migration Data Portal. https://migrationdataportal.org/themes/international-students.

- United Nations. 2017. New Urban Agenda, Habitat III. Quito: United Nations.

- United Nations. 2018. Global Compact for Migration. Accessed September 30, 2019. https://refugeesmigrants.un.org/migration-compact.

- United Nations Population Division. 2019. Workbook UN Migrant Stock. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp.

- United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2019. https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/temporary-protected-status.

- Vosko, Leah. 2010. Managing the Margins: Gender, Citizenship, and the International Regulation of Precarious Employment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Walker, Kyle. 2014. “The Role of Geographic Context in the Local Politics of US Immigration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (7): 1040–1059. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.831544

- Walker, Kyle, and Helga Leitner. 2013. “The Variegated Landscape of Local Immigration Policies in the US.” Urban Geography 32 (2): 156–178. doi: https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.32.2.156

- Wang, Hao, Wei Li, and Yu Deng. 2017. “Precarity Among Highly Educated Migrants: College Graduates in Beijing, China.” Urban Geography 38 (10): 1497–1516. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1314170

- Williams, Kira, and Alison Mountz. 2018. “Between Enforcement and Precarity: Externalization and Migrant Deaths at Sea.” International Migration 56 (5): 74–89. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12439

- Wills, Jane, Kavita Datta, Yara Evans, Joanna Herbert, Jon May, and Cathy McIlwaine. 2010. Global Cities at Work: New Migrant Divisions of Labour. London: Pluto Press.

- Yeoh, Brenda S.A. 2006. “Bifurcated Labour: The Unequal Incorporation of Transmigrants in Singapore.” Tijdchrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 97 (1): 26–37. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2006.00493.x

- Yeoh, Brenda, and Shirlena Huang. 2010. “Transnational Domestic Workers and the Negotiation of Mobility and Work Practices in Singapore’s Home-Spaces.” Mobilities 5 (2): 219–236. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101003665036