ABSTRACT

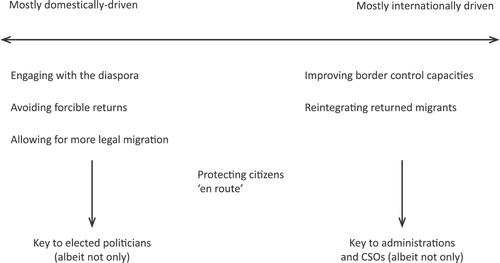

Studies on EU–Africa migration cooperation often focus on the interests of the EU and its member states. But what do African states themselves seek to achieve with respect to migration policy? This article presents an in-depth look at Ghana and Senegal, two stable West African democracies, and assesses which types of migration policies they support, and why. We suggest that a distinction ought to be made between West African policymakers’ more domestically-driven migration policy goals (to cooperate more closely with the diaspora or creating legal migration channels, for example) and internationally-induced ones (such as the reinforcement of border control capacities). Each type of policy interest is defended by an increasingly diverse set of national actors whose interests often – but not always – converge. This distinction should be considered as a continuum, as most West African migration policy preferences are driven by domestic as well as international factors, albeit to diverging degrees. Our findings demonstrate that migration policy-making in countries targeted by international cooperation can only be studied as an ‘intermestic’ policy issue, reflecting the dynamic interplay of international and domestic interests.

Introduction

This article investigates which type of migration policies West African states wish to have, and why that is so. In recent years, West African states have developped more comprehensive migration policies. These policies have been drafted in close cooperation with international actors, most notably the European Union (EU) and the International Organisation for Migration (IOM). The EU's interest in West Africa gained momentum with the migration (governance) crisis of late 2015 and early 2016, when Europe received its highest inflow of refugees since World War II (UNHCR Citation2018). Grappling to address the resultant migration issues, the EU has since developed new EU policy instruments, such as the Migration Partnership Framework, and provided more funding for migration-related projects. Curbing irregular migration and fostering the return of undocumented migrants are two of the EU's key goals in this regard (Carrera, Radescu, and Reslow Citation2015; Sinatti Citation2015). While the EU's interests and strategies are relatively well-known, the migration policy objectives of West African actors, and how they can be explained, are still largely unclear.

Our research draws on the burgeoning literature on the EU's cooperative relations with migrants’ countries of origin and transit (e.g. Boswell Citation2003; Lavenex Citation2004; Reslow and Vink Citation2015; Hampshire Citation2016). A range of studies have focused on the role and negotiation strategies of third countries vis-a-vis the EU's external migration agenda (Van Criekinge Citation2009; Paoletti Citation2011; Cassarino Citation2018). They reveal that non-EU countries that cooperate with the EU are not merely passive recipients of EU policies; rather, they actively react to, interpret, and adapt the EU policy agenda to their own domestic contexts. Our study follows this line of thought, but from a different perspective. Instead of studying the bilateral/multilateral negotiation dynamics, as other authors did, we focus on the following basic question: What do West African actors themselves seek to achieve with respect to migration policy, and why? We strive to investigate the factors that explain West African migration policy preferences. With few exceptions (for example, Poutignat and Streiff-Fénart Citation2010; Sinatti Citation2015; Mouthaan Citation2019), the drivers of migration policy-making in West Africa are still under-researched. This study seeks to partially fill that gap, offering an analytical account of the various actors involved in this dynamic and their migration policy preferences. Ghana and Senegal were selected as case countries due to the fact that both have stable democracies but differ in the degree to which they cooperate with the EU on migration-related issues.

This article seeks to offer both empirical and theoretical insights. Empirically, it gives an overview of the diverse migration policy interests of West African states and shows how these interests diverge between different issue areas and between different groups of policy actors (elected politicians, administrators and civil society actors). Theoretically, we propose to distinguish between the often more longstanding, domestically-defined migration policy preferences and externally-driven ones. The distinction is not dichotomous. We cannot easily draw the line between policy interests that are only driven by domestic factors and others only by international factors. It is a continuum from policy preferences almost entirely driven by domestic factors, to policy preferences equally influenced by domestic and international factors, all the way up to interests that are more driven by international factors than by domestic ones. This continuum serves as a heuristic tool to initiate a theoretical interpretation of the migration policy preferences of West African (democratic) states. We argue that domestically-driven migration policy preferences can primarily be understood by looking at dynamics such as electoral pressures, the economic importance of migration (through remittances), the cultural understanding of migration as a positive phenomenon, and societal mobilisation. The more recent internationally-driven policy preferences stem mostly from donor support, offered by international actors to national administrations to develop particular policies, to buy equipment or to build capacity. Most importantly, we suggest that migration policy preference formation in West Africa should be studied as an ‘intermestic’ policy issue (Rosenblum Citation2004). An intermestic approach elaborates on how international and domestic drivers come to mutually reinforce the development of each others’ preferences. It highlights the dynamic interplay of international and domestic interests. Our research addresses how West African actors seek to match international funding opportunities – and the demands those opportunities carry, with their own interests. The outcome is very issue-specific: in some areas, West African states insist on their priorities (for example, by opposing forcible returns), whereas in others they adapt and reinterpret their initial policy interests, or develop new ones (for example, by enhancing border control capacities).

The next section of this article discusses how our research contributes to the broader academic debate on the external dimension of EU migration policies, migration policy theory (beyond the ‘Western liberal state’) (Cassarino Citation2018; Natter Citation2018; Adamson and Tsourapras Citation2019; Tsourapas Citation2019), and – more generally – on preference formation in postcolonial states (Ayoob Citation2002; Jabri Citation2013). The third section presents the case-selection and methods. The fourth and fifth sections exhibit our empirical work. First, we sketch the actors and institutions involved in migration policy-making in Senegal and Ghana, considering how international organisations and relations influence this process of institution building. We then elaborate on the different migration policy interests in Senegal and Ghana, for whom those interests matter, and why. Finally, we conclude with a summary of our findings and a discussion on ‘intermestic’ migration policy-making in West Africa.

Theoretical approaches to preference formation with regard to West African migration policies

Most theoretical frameworks that explain migration policy preferences originate from research on ‘Western liberal states’ (Natter Citation2018). These theories focus on variables relating to democracy (political partisanship and public opinion), constitutionalism in terms of ‘rights based liberalism’ (Joppke Citation1998), conceptions of community (nationhood), and economics/capitalism (labour needs, depression of wages) (Hampshire Citation2013).

For areas outside the ‘Western liberal states’, the core assumptions of these migration policy theories may not hold. In the West African context, democratic governance is not a given in all states. The political parties and interest groups lobbying for or against a particular migration measure do not neatly fit into classical left/right, labour/capital cleavages. Furthermore, traditional and religious actors may play a more important role in West Africa than in the liberal Western states (Coumba Diop Citation2003; Diagne Citation2011; Siaw and Frempong Citation2019). Other institutions that are key to explaining immigration policy output in Western societies, such as judicial systems and constitutions, may have less of an impact in West Africa. Also, prevailing concepts of nationhood in West Africa, and the underlying view in that region that migration is a positive phenomenon (Coumba Diop Citation2009), may lead to migration policy preferences that differ from those in other settings. Many African states do not consider their borders, which were often drawn arbitrarily during colonial times, to be meaningful demarcations of identity (Ndlovu-Gatsheni Citation2013; Mbembe Citation2018).

Also, the economic stakes of migration politics in West Africa differ from those in Western states, since West African states stand to reap significant benefits from emigration. Emigration, rather than immigration, is of vital economic interest for African countries (Collier Citation2013). In light of these considerations, we must reassess the key variables that inform migration policy preferences in Western states, adapting them to the study of migration policy preferences of (West) African states and the various domestic actors involved in migration decision-making in that region.

Another factor that makes Western migration policy theories inapt for understanding (West) African dynamics is the relativeFootnote 1 inattention they pay to external factors. The (West) African context is marked by its continued economic, political and cultural dependence on former colonial powers. This state of dependency may decrease the autonomy of African policymakers. In this article, we adopt a position that falls somewhere between a structure-oriented approach – which explains migration policy preferences in West Africa by looking at the dependence on foreign donors – and one that focuses on domestic agency. Like postcolonial authors such as Gayatri Spivak (Citation1988) and Homi Bhabha (Citation1994),Footnote 2 we take seriously the agency of West African (migration) policy actors without neglecting the power imbalance characterising their international relations.Footnote 3 Spivak's (Citation1988, 198) focus on ‘enabling violence’ and Bhabha's view on ‘hybridity’ recognise both the agency of the (formerly) colonised within a context of ‘imperialist violence’. With this focus on agency in asymmetrical power relations, the work of Spivak and Bhaba differs from that of Edward Said, who in his book Orientalism describes colonial discourse as 'all powerful’ and the colonial subject as ‘its mere effect’ (cited in Kapoor Citation2002, 6). Our approach is in line with Jean-Pierre Cassarino’s (Citation2018) work on North African countries’ proactive involvement in the securitisation of migration policies, in which he draws on Acharya’s (Citation2004) ‘localisation’ concept. The latter can be defined as a proactive strategy that aims to adapt foreign norms and ideas to local sensitivities and interests.

The existing scholarship on preference formation and policy-making in postcolonial states usually addresses areas such as economic development. Our research focusses on migration policy. The growing attention that European and international actors place on migration issues has created both opportunities and constraints for African states. Private and public actors may make use of the new ‘markets’ emerging from migration cooperation for their economic advantage or institutional growth and maintenance (e.g. Gammeltoft-Hansen and Sørensen Citation2013; Hernandez-Leon Citation2013; Trauner and Deimel Citation2013; Andersson Citation2014). For example, Gammeltoft-Hansen (Citation2011) suggests that states may commercialise their sovereignty, notably in territorial waters, to (European) states eager to externalise migration control. For this, they use development aid, trade privileges, and quotas for labour migration as bargaining chips. Looking at the Senegalese-European migration cooperation, Vives (Citation2017a) suggests that so-called ‘preventive measures’, including development aid, job creation, and temporary migration programmes, have been used to ‘buy’ the support of Senegalese actors in order to curb irregular migration and the return of undocumented migrants.

While this branch of scholarship reveals important dynamics, we would argue that it tends to attribute too much influence to European and international actors, underestimating the role of domestic interests and agency. According to our empirical research, Ghanaian and Senegalese actors have found themselves in a perpetual balancing act, juggling domestically-derived interests with the demands of external donor and opportunity structures. For these reasons, we argue that migration preference formation in West Africa needs to be studied as an ‘intermestic’ policy issue. The plea that migration be studied as an intermestic policy issue has been suggested for the US context (Lowenthal Citation1999; Rosenblum Citation2004). These scholars argue that theories that take into account the migration policy preferences of national and international actorsFootnote 4 outperform those that only consider domestic or international factors in migration policy-making. In the case of the US, the migrant-sending states were shown to have influenced US migration policies, for example through direct lobbying, by linking US migration policy to other bilateral policy areas, or by directly influencing migration outcomes (Rosenblum Citation2004, 140). This seems even more relevant in West Africa. However, in the case of West Africa, the relevant international actors who influence national migration policies are not migrant sending-states, but rather donors (mostly migrant-receiving states and international organisations). We demonstrate in this article that the policy preferences of West African actors can only be understood by means of an ‘intermestic approach’, that addresses domestic-international interactions.Footnote 5

Case-selection and methods

Ghana and Senegal are the two case-countries chosen for this study. These states share some important features. Among the West African countries, both countries are seen to be functioning states with stable democracies. They have competing political parties, a free civil society, and established administrations, allowing us to check the influence of these variables on the formation of policy preferences. We also seek to understand how external actors interact with West African actors and influence their interests. Both, Ghana and Senegal count the presence of international migration actors. At the same time, Ghana and Senegal differ in some important respects, such as the colonising country of their past (Britain in the case of Ghana, France in the case of Senegal). Senegal and Ghana also differ socio-economically: Senegal's GDP per capita is two-thirds that of Ghana (1.641$ in 2017). Given this contextual variation, we may expect to find different sets of domestic interests, which would then intersect differently with externally defined preferences. However, while this study highlights some differences, our emphasis is on the broadly similar migration policy interests and dynamics of preference formation to be found in Ghana and Senegal. Indeed, our fieldwork demonstrates that the need to balance domestic and international pressures was similar for both countries.

In addition to analysing policy documents and secondary sources, we rely on semi-structured expert interviews as our main empirical basis. In contrast to policy-related research in Western contexts, for which there is sometimes a plethora of government documents, policy research in West Africa depends largely on primary data such as interviews. Our results are mainly based upon 88Footnote 6 interviews, conducted during four months of fieldwork in Accra, Dakar, and Brussels in early 2018. The interviewees represent the full spectrum of actors involved in migration policy-making in Ghana and Senegal. They include policy officers working for international organisations and national administrations, representatives of civil society organisations, academics, and policy analysts. The full transcription of the interviews enabled us to carry out a qualitative content analysis (Schreier Citation2012) using the Nvivo text processing software.

Our typology of migration policy preferences and the intermestic approach to preference formation emerged after four rounds of coding by all authors of this article. In the interviews, we first selected all of the information on the migration policy preferences of Senegalese and Ghanaian actors, and then that on the processes behind the formation of those preferences. The coding led to six broad types of migration policy preferences in West Africa: engaging with the diaspora, avoiding forcible returns, promoting legal migration channels, protecting migrants en-route, building border capacities, and reintegrating returned migrants back into their home countries. With regard to the drivers of preference formation, our coding revealed modes of policy development indicative of an ‘intermestic’ approach to preference formation, i.e. West African policymakers’ constant attempt to balance externally-induced opportunities and constraints against domestic interests.

Migration policy-making in Ghana and Senegal

Migration policy in Senegal and Ghana is handled through different ministries – and within them, various departments, agencies and units. In addition, new migration-related civil society organisations have emerged alongside these public institutions. The civil society actors and public administrations receive funds from international actors to develop projects or policies. IOM has considerably extended its activities across the region. As a consequence, its role has recently come under fire by national actors (Trauner et al. Citation2019).

The legal basis of the Senegalese migration framework was established in 1971. It governs the conditions under which foreign nationals may enter, gain residency, and become established in the country (ICMPD Citation2015). Senegal's institutional landscape on migration has been described as ‘fragmented’.Footnote 7 The most important ministries are the Ministry of the Interior, responsible for police and border police, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, hosting the Directorate General for Consular Affairs. The latter issues travel documents and is also responsible for documenting returnees. Another key player is the Directorate General for Diaspora (DGSE), which is part of the ministry of Foreign Affairs and handles policy and programme development for Senegalese living abroad. The DGSE has established numerous ‘Bureaus d’Acceuil et Orientation’ (BAOS) advising Senegalese who live abroad and their families about return options, reintegration prospects, and investment opportunities. The Directorate General for Employment negotiates labour agreements with third countries, aiming to create employment opportunities abroad. The Directorate General of Human Capital of the Ministry of Finance coordinated the National Migration Policy (NMP), which was developed between 2015 and 2018 and financed by the IOM development fund. Several other ministries, such as the national anti-trafficking unit of the Ministry of Justice, also handle migration-related issues. Since 2005, Senegal has enforced a harsh anti-smuggling and trafficking law imposing up to 10 years in prison for human traffickers, smugglers and document forgers (Vives Citation2017a, Citation2017b).Footnote 8 External actors were involved in almost all issue areas defining the country's migration policy. IOM, the EU, and EU member states particularly influenced the setup of key administrative units.

In Ghana, the overall structure is similar. Due to its geographical position away from the Western or Central African migration routes to Europe, Ghana has been less of a priority country for the EU than Senegal with respect to migration cooperation (Van Criekinge Citation2009) even if the EU's interest has slowly but steadily grown since the 2010s. As in Senegal, Ghana's main ministries dealing with migration are also the Ministry of the Interior and Foreign Affairs. Within the structures of the Ministry of Interior, the ‘Ghana Immigration Service’ (GIS) deals with entry, residence and border policies. In 2014, the EU launched the Ghana Integrated Migration Management Approach (GIMMA) which sought to further strengthen the GIS's operational capacities. With the IOM as an implementing agency, the EU-led approach focused on strengthening the effectiveness of the Ghanaian border guard by giving them training and equipment, holding information campaigns, restructuring the Migration Information Bureau, and opening the new SunyaniFootnote 9 Migration Information Centre. Similar to the setup in Senegal, the Ghanaian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoF) is responsible for issuing travel documents and handling return and diaspora affairs, with the latter being done by the Diaspora Affairs Bureau (DAB). The move of the DAB from the MoF to the office of the Presidency after the 2016 presidential elections possibly demonstrates the increased political salience of diaspora affairs in Ghana, also brought on by the announcement of voting rights for Ghanaians abroad.Footnote 10 The Migration Policy Unit of the Ministry of the Interior was in charge of developing the National Migration Policy. This was finalised in 2016, also with financial support from IOM and other donors. Other actors such as the Centre for Migration Studies at the University of Ghana have also helped to develop Ghana's migration policy. A diaspora engagement policy, which has been in the drafting stage since 2011, is currently under revision. Additionally, the Labour Ministry drafted and launched a National Labour Migration Strategy in 2017, with the support of the ACP-EU migration action. In contrast to Senegal, Ghanaian civil society organisations have not strongly mobilised against the forced return of immigrants abroad. However, similar to Senegal, several national civil society organisations have engaged in the reintegration of returned nationals, mostly together with IOM.

The national migration policy actors presented above function in an international context. If we are to fully understand how migration policy preferences develop in Senegal and Ghana, we need to provide some insight into this international context. The three most relevant international (f)actors for understanding national migration policy-making are (1) the membership of Ghana and Senegal of ECOWAS, the Economic Community of West African states, (2), the push for cooperation by the EU and its member states, and (3) general donor-dependency. Ghana and Senegal are both members of ECOWAS, whose free movement protocol they signed in 1971. Some barriers to free movement remain in Senegal and Ghana, particularly regarding residence rights and access to public services of intra-ECOWAS migrants (ICMPD Citation2015). Nevertheless, respondents in Senegal and Ghana stated that the ECOWAS Treaty and subsequent protocols set the frame for their migration policy. Safeguarding and working towards its full implementation remains a priority.

In addition to the ECOWAS framework, the EU and some of its member states have been a relevant source of external influence, notably in Senegal. Following the ‘Canary Island crisis’ of 2006, when approximately 30,000 migrants arrived by boat on the archipelago, Spain took the lead in enhancing Senegalese border control capacities and established joint border monitoring operations. Spain incentivised the cooperation with several development projects and a legal migration scheme (e.g. Ba Citation2007; Andersson Citation2014; Vives Citation2017b). In the years after 2006, Senegal also signed a number of bilateral migration and readmission agreements with other member states in exchange for development aid. In comparison, no EU member state has managed to sign a bilateral readmission agreement with Ghana. Due to its geographical position further away from the migratory route to Europe, migration has not reached a similar level of salience in EU-Ghanaian relations (Van Criekinge Citation2009).

Bringing together European and African heads of state, the 2015 Valletta Summit created the Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF), endowing it with an initial funding of €3.2 billion. The EUTF has a twofold aim: first, it attempts to address the ‘root causes of migration’, and second, it aims to motivate African actors to cooperate more on issues of migration control. In general, European development aid is increasingly being used to serve the EU's migration agenda. This is referred to as the ‘diversion of aid’ (Vives Citation2017a; Oliveira and Zacharenko Citation2018). Acknowledging European interest in cooperating with African states is crucial when attempting to understand African interests, given that many African governments face an aid-dependency, often following wider postcolonial dependencies (Williams Citation2000; Ayoob Citation2002). This reliance on aid, as we will show in the next section, influences but does not fully explain national migration policy preferences.

Migration policy interests in West Africa

Most of our interviewees highlighted that migration is not a key priority for politicians in Ghana and Senegal. Socio-economic policies such employment, education, and health as well as sanitation and infrastructure usually receive more attention. An exception is the issue of forcible returns of emigrants, which is politically highly salient. Readmission negotiations and agreements facilitating forced return are widely debated, notably in the press. Overall, migration in Senegal and Ghana is more an issue of bureaucratic politics than of partisan politics. However, since the 2000s the issue of migration has gained significance on political agendas in Ghana and Senegal. Partially in response to funding offers from external donors such as the EU and international organisations, new migration policy interests have emerged and older migration-related concerns have been defined more explicitly. The latter mark a set of preferences that are also more domestically driven. The distinction between domestically-driven and internationally-induced policy interests is often blurred, yet it allows us to conceptually identify processes of intermestic preference formation. The increase in cooperation with European and international actors – and the manifold funding opportunities that such a cooperation entails – has led West African actors to define new priorities.

Domestically-driven migration policy interests

Domestic interests in migration in Senegal and Ghana focus mainly on international emigration, rather than internal and intra-regional migration (within ECOWAS). Given that West Africans mainly migrate within the region, this may come as a surprise (ICMPD Citation2015). Nevertheless, interviewed policymakers did not point to the development of regional migration policies as a key policy interest. Engaging with the diaspora, promoting legal emigration channels, and preventing the forced return of emigrants are key policy interests of West-African policymakers. Elected politicians place a particular emphasis on these interests. More recently, national policy-makers in Ghana and Senegal have also developed a stronger interest in protecting migrants ‘en route’.

Engaging with the diaspora

According to our interviewees, engagement with the diaspora is a key interest for politicians in both Ghana and Senegal. As one interviewee noted, ‘there is a big focus of the government on diaspora and its contribution’.Footnote 11 The diaspora is seen to contribute to socio-economic development, particularly through financial and social remittances. In both countries, financial remittances from citizens living abroad exceed official development aid and foreign direct investment (World Bank Group Citation2017). The interest in diaspora policies is also related to their right to vote. In Senegal, persons in the diaspora have been able to vote since 1993. Dual citizenship was always allowed. In Ghana, dual citizenship was introduced in 2002.Footnote 12 Ghanaian voting rights for citizens abroad were scheduled to take effect as of 2020.Footnote 13

In both countries, the focus of the diaspora policy objectives has shifted from remittances towards a more comprehensive engagement with the diaspora community. Particularly in Ghana, the government has begun to promote the voluntary return of highly-skilled emigrants in order to achieve skill transfers via returning nationals. A case in point has been the Ghanaian government, which used to reach out to its citizens abroad on a more ad hoc basis. In 2012, for example, it organised a ‘diaspora conference’ and some ‘homecoming’ events. Eventually, however, the Ghanaian government developed a more systematic diaspora engagement, primarily funded by external European donors.Footnote 14 European governments such as Spain and the EU as a whole actively supported this new approach, framed as a win-win-win situation in terms of skills transfers and development. The assumption is that not only remittances, but also the direct transfer of skills via returning nationals, shape the development of West African countries.Footnote 15 According to a Senegalese official, returned migrants may ‘improve the capacities of the country by engaging in local enterprises (own translation)’.Footnote 16 Similarly, in Ghana, the positive contribution of returnees is being noted by policy-makers. ‘A lot of the health care professionals have now begun to come back. They set up private clinics and hospitals’,Footnote 17 noted one interviewee. Indeed, promoting the voluntary return of the persons in the diaspora is considered a ‘higher-level political’ priority in Ghana than in Senegal,Footnote 18 as emigration of the highly-skilled is more prominent in the former than in the latter. Institutionally, this interest in diaspora policies has translated into the creation of ‘Diaspora Affairs Bureaus’ or ‘units’ within the institutional structures of the Ghanaian Presidency or the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.Footnote 19 Almost every time that the presidents of Ghana or Senegal now travel abroad, a meeting with members of the diaspora is scheduled.Footnote 20 Policymakers also now compile data on the diaspora through their embassies.Footnote 21

European policymakers seem to have understood the importance of diaspora policies for countries like Senegal and Ghana. Indeed, some authors have called the EU's funding of diaspora policies an alternative ‘currency’ (Vives Citation2017a, 9). The EU pays the latter in exchange for the host country's support of returning migrants who are unwanted by the EU, as well as for deterring and stopping prospective migrants from entering the EU.

To some extent, engaging with persons from the diaspora and encouraging emigrants to return to their home countries has also been connected to claims for historical justice concerning the slave trade. In this case, the argument in favour of both of these policies has been embedded in a narrative of pan-Africanism and decolonialisation. In Ghana, these considerations boil down to the right of Afro-descendants to permanently reside in the country.Footnote 22 In practice, however, settling in Ghana does not seem easy for Afro-descendants,Footnote 23 as observants describe this ‘right of abode policy’ as ‘marred by loopholes’.Footnote 24

Avoiding forcible returns

West African governments’ interest in engaging with their diasporas and the economic benefits of return or remittances affect their position on the forced return of their nationals. On this topic, the interests of the EU and West Africa are quite divergent. For the EU, the effective return from European territory of undocumented migrants is crucial. For this reason, the EU lobbies African politicians and officials to agree to readmission agreements and help identify their citizens to ensure a smooth return. These demands can hardly be met by West African leaders. From the perspective of the Senegalese and Ghanaian governments, a readmission agreement is likely to harm not only its standing within the diaspora communities and their families at home, but also the flow and number of remittances. Ghana and Senegal are democratic states, meaning that party politics and elections come into play. Several of our respondents confirmed that if their governments were to accommodate the EU's demands, opposition parties would not hesitate to mobilise against them. Many families directly or indirectly benefit from remittances. There is also a high risk that returnees will end up unemployed. According to interviews with local civil society leaders, neither the governments nor international organisations are equipped to meet returnees’ needs with regard to employment opportunities or mental health care, if required.

European actors have come to understand that readmission and forced return are perceived as ‘going against the interest of the [West African state's] own population’.Footnote 25 They hope that financing programmes or making concessions on other migration issues may encourage the cooperation of non-EU countries with regard to forced return. Given the political sensitivity of the issue, both European and West African actors increasingly see informal channels of cooperation and non-binding readmission arrangements as more promising than formal agreements. Indeed, some interviewed civil servants and NGOs – who do not need to be elected – indicate a certain willingness to cooperate on non-legalised schemes of forced return. These may take the form of identification missions, or EU-funded projects aimed at persuading detained West African citizens to ‘voluntarily’ return from Europe.

Allowing for more legal migration

Unsurprisingly, new channels of legal migration (study and work visas) are important objectives for the governments of Ghana and Senegal. Both countries have young populations that lack employment opportunities. For West Africans, it is often nearly impossible to obtain a regular travel or work visa to Europe. Student visas are also hard to get. The lack of legal opportunities is considered to be a main reason for irregular migration from Senegal and Ghana, as expressed by a Ghanaian policy officer:

Most Ghanaians – and most Africans – do not want to go and live in Europe forever. But he will be refused when he comes back [to West Africa] and wants to go back [to Europe]. So he finds another means of getting there and doesn't come back. Now previously, when the visa regime was flexible, we hardly found this situation. When you tighten it, you will find another way of getting in.Footnote 26

Nobody wants migration in an irregular manner. Therefore, you have to regularize it. We need and want a legal migration policy. Irrespective of the level of the development of your country, there will always [be] people who would like to leave.Footnote 28

Protecting citizens ‘en route’

In recent years, Ghana and Senegal have also developed a stronger interest in protecting their citizens who are on their way to their final destination or have migrated to the Gulf states. In Senegal this already arose as of the Canary Islands crisis of 2006. In the wake of the 2015/2016 migration (governance) crisis, media coverage on migrant death, and notably a CNN documentary on migrant slave auctions in Libya released in 2016, pushed strong public awareness of the widespread human rights violations that African migrants face there. The impact of the CNN report was described as considerable in the region. The government of Ghana pushed the issue of migrant protection when starting to implement the National Migration Policy. As a Ghanaian immigration official stated: ‘When the documentary came out, the whole country was frightened. The new government has even made it a policy now’.Footnote 34 It also triggered a range of other measures, such as the opening of West African consulates in Libya and Niger and a stronger focus on, and acceptance of, IOM-led assisted voluntary return operations along the Central Mediterranean migratory route. Domestic actors working on campaigns (partly funded by the EU) to raise public awareness of the dangers of irregular migration were given an additional, publicly known argument in support of their endeavours.

The governments of Senegal and Ghana have also become more concerned with the conditions faced by their citizens when working abroad. For Ghana, a particular concern has been the situation of their citizens in the Gulf countries. They often work under highly precarious conditions, or are victims of human trafficking.

Internationally-induced migration policy interests

In a context of continued economic dependency of West African states, cooperation with European and international actors – and the many funding opportunities this entails – has led West African actors to develop some new migration-related priorities. Policy actors in Senegal and Ghana have recently developed a keener interest in capacity building with respect to border control and security, and in reintegration programmes for returned nationals. These interests are particularly characteristic of non-elected policymakers, that is, bureaucrats and civil society organisations. International funding allows for the further organisational development of ministries, agencies and civil society organisations. It promotes not only the creation of a ‘migration industry’ (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Sørensen Citation2013) but also of a ‘migration bureaucracy’ in West Africa, with its own interests in obtaining more power and resources.

Improving border control capacities

As mentioned earlier, following the ‘Canary Island crisis’ of 2006, the better control of the Senegalese-Spanish maritime border has become a priority for Spanish- and EU-funded capacity-building projects such as the Seahorse project, which is focused on information exchange. Other projects seek to enhance the capacities of law enforcement authorities to prevent and combat smuggling and trafficking in goods and humans, detect document fraud, and improve the security infrastructure at border control points. The Ghanaian and Senegalese ministries of the interior and law enforcement agencies are the key beneficiaries of this type of support.

Why do actors in the two countries allow these projects? At first glance, it seems to contradict the widespread West African conception of migration as a process which benefits both the migrants and the society they left behind. It is also at odds with the idea that African borders are arbitrary, since they were drawn at the Berlin conference by Europeans in 1885, and thus artificially divided former African empires and ethnic groups (Ajala Citation1983). Moreover, strengthening national borders seems to conflict with the idea of a ‘borderless West Africa’ within ECOWAS (Apedoju Citation2005). Yet the interviewees justified the need for stricter border control in West Africa for several reasons. Firstly, they mentioned the deteriorating security situation in the region. In Senegal, Mali is a key concern, while for Ghanaian actors it is Nigerian immigration. Besides the threat of terrorist groups operating in Mali, for Ghana cross-border crime and human trafficking towards Arab Gulf states have become serious domestic security concerns.Footnote 35 Secondly, the international funding for border capacity-building has provided certain West African bureaucracies with opportunities to improve their own standing and budgetary resources. In a struggle for administrative power and resources, EU-funded projects bring real economic benefits and symbolise internationalisation and competence. Our data support the argument of Cassarino (Citation2018, 397–398) suggesting that the West African actors’ involvement in the securitisation of migration should not be seen as a mere ‘passive reception’ of Western policies, but as a ‘reinterpretation with a view of reaching other ends’.

That said, not all West African actors subscribe to more border controls. According to a staff member of an international organisation in West Africa, the ‘governments in the region might find it great that their police officers get some training … and new pickup trucks, but they don't really care about these borders’.Footnote 36 In other words, improved capacities do not automatically translate to working towards the objectives of international actors, that is, to more stringent border controls. Indeed, some interviewees cautioned that the reinforcement of border controls would undermine the objectives of the ECOWAS free movement zone. Civil servants counter such criticism with the argument that border controls do not impede mobility – they just surveil and regulate movements.Footnote 37

Reintegrating returned emigrants

While many Ghanaian and Senegalese societal and political actors oppose cooperation on forcible returns, such returns take place to some extent. Moreover, the International Organisation of Migration (IOM) runs large-scale ‘assisted voluntary return programmes’ targeting West-African migrants in Libya and elsewhere (Andersson Citation2014; Trauner et al. Citation2019). These programmes usually have a reintegration component for the returnees. Indeed, the successful reintegration of these citizens in their local communities and labour markets is of interest to West African policy actors. While the reintegration of returned emigrants does not attract much attention from elected politicians, ministries and civil societies see opportunities in this cooperation. However, the process remains contested. How much reintegration support is needed? Who should be in charge of this process? Whereas the EU channels this support through the IOM, Senegalese and Ghanaian actors would like to become responsible for externally-funded reintegration support. Senegalese policymakers have started to contest the role of the IOM as the principal receiver of funds. According to Senegalese interviewees, it would make more sense to grant funding for the reintegration of returnees directly to state institutions and civil society actors, without co-financing international officials.Footnote 38 The IOM's role has been less contested in Ghana, where policymakers referred to IOM-implemented and EU-funded projects as a form of ‘corporate social responsibility’.Footnote 39 In both countries, civil society actors argue that the reintegration of returnees can only take place with the help of local communities.

Conclusion

This article has shown that the migration-related policy interests of West African states are diverse and have been evolving, in particular since the EU and its member states have become more engaged in the region. It proposes an ‘intermestic approach’, highlighting the close interlinkages of international and domestic actors in terms of migration policy-making in West Africa.

Contrary to many European countries, and with the exception of the question of forcible returns, migration is not among the most salient of policy issues in West Africa. Yet the overall relevance of the various issues that define migration policy in this region has clearly increased in recent years. More and more West African bureaucracies are dealing with migration issues, and have sought to become relevant migration policy actors, spurred on by domestic competition for international funding.

In this article, we have differentiated between more domestically-driven and more internationally-driven West African migration policy interests. Interests driven by domestic concerns are: closer engagement with the diaspora, the creation of legal migration channels, the prevention of West African citizens’ forcible return, and – more recently – the protection of vulnerable migrants en route. The growing international attention to West African migration policy-making has spurred the emergence of new migration policy interests, including the strengthening of the border control infrastructure and the provision of reintegration support to migrants who have participated in assisted voluntary return programmes. It is remarkable that most West African migration policy preferences reflect the EU's concern for (irregular) south-to-north migration, especially in a context wherein most West-Africans migrate within the region. In a way, West African governments respond to this concern by considering more regulations in this area.

It is also important to highlight that there is no uniform set of West African migration policy interests. Different policy actors in West Africa have, of course, different interests. Our paper has sought to distinguish between the interests of three groups: political actors, who must win elections and need to respond to domestic mobilisation and address salient issues; administrative actors, who seek bureaucratic expansion and tend to hold the most favourable view of EU priorities and funding opportunities; and societal actors, whose diverse stances range from a total rejection of the EU's agenda to the embracement of the new opportunities brought on by cooperation. Overall, migration policy-making in West African democracies is characterised by tight political constraints and diversified interests – not only those of international donors, but also of elected politicians, recently empowered administrative entities and civil society organisations, the diaspora, and an increasingly active citizenry at home.

In the above pages, we have sought to offer a nuanced account of migration policy interests among West African policymakers and their drivers. We recognise the important role of European and international actors in shaping West African policymakers’ preferences (like for example, Vives Citation2017a), but we offer a more nuanced view by also recognising the domestic drivers of these preferences. Taking into account West Africa's postcolonial dependency, we do not go as far as to claim that West African states’ policy preferences develop primarily out of domestic dynamics (for example, see Natter Citation2018 on North Africa). We take an intermediate position, observing that the policies developed by Ghanaian and Senegalese actors respond to both domestic and external incentives. In line with what scholars have noted for a different setting (Lowenthal Citation1999; Rosenblum Citation2004), we demonstrated that migration policy-making in these countries should be studied as ‘intermestic’ politics, in which West African actors are constantly seeking to balance external funding opportunities (and the conditions attached to them) with their own domestic interests. The outcome is issue-specific: in some areas, West African states insist on their priorities (for example, by opposing forcible returns), whereas in others they either adapt their priorities (for example, by promoting ‘voluntary return’) or develop new ones (for example, by enhancing border control capacities). A non-dichotomous distinction between domestically driven and internationally driven migration policy interests (see ), therefore, would serve as a heuristic for understanding policy-making in the target countries of EU migration policy cooperation.

This analysis of migration policy preferences and their formation has focused on two West African countries – Senegal and Ghana – with two particular migration histories. Our findings invite further exploration of how the countries targeted by international migration cooperation initiatives navigate between externally-induced opportunities and pressures and domestic ones. This intermestic approach to migration policy development will help to build migration policy theories that provide insights ‘beyond the liberal West’ (Natter Citation2018).

Acknowledgements

The researchers thank the research assistants Mamadou Faye and Rosina Badwi for their invaluable support, as well as the numerous interviewees for offering their time and invaluable insights. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the editorial assistance of Laura Cunniff (Europa-Universität Flensburg) and the outstanding comments of the anonymous reviewers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Western migration policy theories do look at supranational governance or human rights norms as drivers of national migration policy-making, but not to the relevance of external donor-support, which is, one has to admit, rather absent in (at least) West European and settler states.

2 It might seem surprising that in an article on Senegal and Ghana we do not make use of of local postcolonial authors like Léopold Sédar Senghor. This is so because the focus on the role of agency versus structure is less present in the work of Senghor. Senghor's work on the négritude concept is an example of agency against a dominant European philosophy but he did not explicitly pronounce himself on the relation between agency and structure in a postcolonial relationship.

3 For more information on the role of agency versus structure in the dependency and postcolonial theories, see Kapoor (Citation2002).

4 In the case of the United States, the most important international actors studied for understanding domestic immigration policies are the sending states, with a particular focus on Mexico.

5 In a recent article, Adamson and Tsoupras (Citation2019) develop the concept of ‘migration diplomacy’. Although their focus is different than ours, as they only focus migration foreign policy, and we study foreign and domestic migration policy preferences, they also point to the interwovenness of domestic and foreign interests.

6 We conducted 44 interviews in Senegal, 38 in Ghana and 6 in Brussels.

7 Interview with International Organisation (IO) official, Dakar, 16.2.2018.

8 The law is currently under revision.

9 Sunyani is a city in the West of Ghana in the region of Brong-Ahafo, the region from where most lowly-skilled Ghanaian emigrants leave.

11 Interview, International Organisation, Dakar, 16.02.2018.

12 Interview, European Member State, Dakar, 02.03.2018.

13 Court clears Ghanaians in Diaspora to vote in 2020. Ghanaweb, 19 December 2017. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Court-clears-Ghanaians-in-diaspora-to-vote-in-2020-610657#

14 Interview, Academic, Accra, 17.04.2018.

15 Interview, Former Civil Servant, Accra, 10.04.2018.

16 Interview, Civil Servant, Dakar, 02.03.2018.

17 Interview, Academic, Accra, 25.05.2018.

18 Interview, Former Civil Servant, Accra, 10.04.2018.

19 Interview, European Member State Development Agency, Accra, 03.05.2018.

20 Interview, Former Civil Servant, Accra, 10.04.2018 and Interview, Civil Servant, Dakar, 07.03.2018.

21 Interview, Civil Servant, Accra, 17.05.2018.

22 Le Ghana appelle sa diaspora à ‘rentrer à la maison’. Le Monde, 16 janvier 2019. https://www.lemonde.fr/afrique/article/2019/01/16/le-ghana-invite-sa-diaspora-a-rentrer-a-la-maison_5409837_3212.html

23 Interview, Civil Society, Accra, 14.05.2018.

24 Modern Ghana, Ghana's ‘Right Of Abode’ Programme Could Attract More Black People From Across The Globe But Marred By Loopholes, 5 October 2018.

25 Interviews with IO officials, Accra, 2018.

26 Interview, Civil Servant, Accra, 17.05.2018.

27 Interview a, Civil Servant, Accra, 17.05.2018 and Interview b, Civil Servant, Accra, 17.05.2018 and Interview, Civil Servant, Accra, 14.05.2018.

28 Interview, Civil Servant, Dakar, 25.01.2018.

29 Interview with IO official, Accra, 12.04.2018.

30 Interview, European Member State Development Agency, Accra, 03.05.2018.

31 Interview, Civil Society, Accra, 14.05.2018.

32 Interview, Civil Society, Accra, 15.05.2018.

33 High Level Dialogue Meeting, ‘Joint declaration on Ghana-EU Cooperation on Migration’ (Brussels, 16 April 2016).

34 Interview, Civil Servant, Sunyani, 08.05.2018.

35 Interview, Academic, Accra, 17.04.2018 and Interview, Civil Servant, Dakar, 08.02.2018 and Interview, European Member State Development Organisation, Dakar, 06.03.2018.

36 Interview with IO official, Dakar, 16.02.2018.

37 Interview, German Political Foundation, Dakar, 13.02.2018 and Interview, Civil Servant, Accra, 04.05.2018.

38 Interview Senegalese consultant, Dakar 23.03.2018 and interview IO official, Dakar, 16.02.2018.

39 Interview Civil Servants, Accra, 17.04.2018.

References

- Acharya, A. 2004. “How Ideas Spread: Whose Norms Matter? Norm Localization and Institutional Change in Asian Regionalism.” International Organization 58 (2): 239–275. doi:10.1017/S0020818304582024.

- Adamson, F. , and G. Tsourapras . 2019. “The Migration State in the Global South. Nationalising, Developmental and Neoliberal Models of Migration Management.” International Migration Review . Forthcoming.

- Ajala, A. 1983. “The Nature of African Boundaries.” Africa Spectrum 18 (2): 177–189.

- Andersson, R. 2014. Illegality, Inc. Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe . Oakland, CA : University of California Press.

- Apedoju, A. 2005. Creating a Borderless West Africa: Constraints and Prospects for Intra- Regional Migration . Lagos : UNESCO. Accessed March 28, 2019. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000139142 .

- Ayoob, M. 2002. “Inequality and Theorizing in International Relations: The Case for Subaltern Realism.” International Studies Review 4 (3): 27–48. doi: 10.1111/1521-9488.00263

- Ba, C. O. 2007. “Barça ou barzakh: La migration clandestine sénégalaise vers l’Espagne entre le Sahara Occidental et l’OceanAtlantique.” Oral Communication, Round Table organized by Casa Arabe, Murcie and Madrid, 7–8 June. www.casaarabeieam.es.

- Bhabha, H. 1994. The Location of Culture . London : Routledge.

- Boswell, C. 2003. “The ‘External Dimension’ of EU Immigration and Asylum Policy.” International Affairs 79 (3): 619–638. doi: 10.1111/1468-2346.00326

- Carrera, S. , R. Radescu , and N. Reslow . 2015. EU External Migration Policies. A Preliminary Mapping of the Instruments, the Actors and their Priorities . Brussels : EURA-net project.

- Cassarino, J. 2018. “Beyond the Criminalisation of Migration: A Non-western Perspective.” International Journal of Migration and Border Studies 4 (4): 397–411. doi: 10.1504/IJMBS.2018.096756

- Collier, P. 2013. Exodus: Immigration and Multiculturalism in the 21st Century . London : Allen Lane.

- Coumba Diop, M. 2003. Lé Sénégal Contemporain . Paris : Karthala.

- Coumba Diop, M. 2009. Le Sénégal des migrations. Mobilités, identités et sociétés . Paris : Karthala.

- Diagne, M. 2011. Pouvoir Politique et espaces religieux au Sénégal: Gouvernance locale à Touba, Cambèrene et Médina Baye. Université du Québec à Montréal: Phd thesis in Political Science.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. 2011. Access to Asylum. International Refugee Law and the Globalisation of Migration Control . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. , and N. N. Sørensen , eds. 2013. The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration . London : Routledge.

- Hampshire, J. 2013. The Politics of Immigration: Contradictions of the Liberal State . Cambridge : Polity.

- Hampshire, J. 2016. “Speaking with One Voice? The European Union’s Global Approach to Migration and Mobility and the Limits of International Migration Cooperation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (4): 571–586. ISSN 1369-183X. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2015.1103036

- Hernandez-Leon, R. 2013. The Migration Industry: Brokering Mobility in the Mexico-U.S. Migratory System . Los Angeles, CA : UCLA International Institute.

- ICMPD . 2015. A Survey on Migration Policies in West Africa . Vienna : International Centre for Migration Policy Development.

- Jabri, V. 2013. “Peacebuilding, the Local and the International: A Colonial or a Postcolonial Rationality?” Peacebuilding 1 (1): 3–16. doi:10.1080/21647259.2013.756253.

- Joppke, C. 1998. “Why Liberal States Accept Unwanted Migration.” World Politics 50 (2): 266–293. doi: 10.1017/S004388710000811X

- Kapoor, I. 2002. “Capitalism, Culture, Agency: Dependency versus Postcolonial Theory.” Third World Quarterly 23 (4): 647–664. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3993481 . doi: 10.1080/0143659022000005319

- Lavenex, S. 2004. “EU External Governance in ‘Wider Europe’.” Journal of European Public Policy 11 (4): 680–700. doi:10.1080/1350176042000248098.

- Lowenthal, A. 1999. “U.S.-Latin American Relations at the Century’s End: Managing the ‘Intermestic’ Agenda.” In The United States and the Americas: A Twenty-First Century View , edited by A. Fishlow , and J. Jones , 109–136. New York : WW Norton.

- Mbembe, A. 2018. “The Idea of a Borderless World.” The Chimurenga Chronic Oktober. Accessed May 17, 2019. https://chimurengachronic.co.za/the-idea-of-a-borderless-world/ .

- Mouthaan, M. 2019. “Unpacking Domestic Preferences in the Policy-‘Receiving’ State: The EU’s Migration Cooperation with Senegal and Ghana.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (37). https://comparativemigrationstudies.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40878-019-0141-7 .

- Natter, K. 2018. “Rethinking Immigration Policy Theory Beyond ‘Western Liberal Democracies’.” Comparative Migration Studies 6 (4). doi:10.1186/s40878-018-0071-9.

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. 2013. Coloniality of Power in Postcolonial Africa. Myths of Decolonization . Dakar : Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa.

- Oliveira, A. , and E. Zacharenko . 2018. EU Aid: A Broken Ladder? Concord Europe. AidWatch Report. Accessed March 28, 2019. https://library.concordeurope.org/record/2041 .

- Paoletti, E. 2011. “Power Relations and International Migration: The Case of Italy and Libya.” Political Studies 59 (2): 269–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2010.00849.x

- Poutignat, P. , and J. Streiff-Fénart . 2010. “Migration Policy Development in Mauritania: Process, Issues and Actors.” In The Politics of International Migration Management. Migration, Minorities and Citizenship , edited by M. Geiger and A. Pécoud , 202–219. London : Palgrave Macmillan.

- Reslow, N. , and M. P. Vink . 2015. “Three-Level Games in EU External Migration Policy: Negotiating Mobility Partnerships in West Africa.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 53 (4): 857–874.

- Rosenblum, M. 2004. “The Intermestic Politics of Immigration Policy: Lessons from the Bracero Program.” Political Power and Social Theory 16: 139–182. doi:10.1016/S0198-8719(03)16005-X.

- Schreier, M. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice . London : Sage Publishing.

- Siaw, E. , and A. Frempong . 2019. “Chiefs and Politicians in Ghana. Competitors, Collaborators or Uneasy Bedfellows?” In Politics, Governance and Development in Ghana , edited by J. Ayee , 21–42. Lanham : Lexington Books.

- Sinatti, G. 2015. “Return Migration as a Win-Win-Win Scenario? Visions of Return among Senegalese Migrants, the State of Origin and Receiving Countries.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (2): 275–291. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2013.868016

- Spivak, G. 1988. In Other Worlds . New York : Routledge.

- Trauner, F. , and S. Deimel . 2013. “The Impact of EU Migration Policies on African Countries: The Case of Mali.” International Migration 51 (4): 20–32. doi: 10.1111/imig.12081

- Trauner, F. , L. Jegen , A. Ilke , and C. Roos . 2019. “The International Organization for Migration in West Africa: Why Its Role Is Getting More Contested since Europe’s ‘Migration Crisis’.” UNU-CRIS Policy Brief, 03/2019. Accessed May 17, 2019. http://cris.unu.edu/international-organization-migration-west-africa-why-its-role-getting-more-contested .

- Tsourapas, G. 2019. The Politics of Migration in Modern Egypt: Strategies for Regime Survival in Autocracies . Cambridge : Cambridge University Press.

- UNHCR (The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) . 2018. “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2017.” Accessed March 27, 2019. https://www.unhcr.org/5b27be547.pdf .

- Van Criekinge, T. 2009. “Power Asymmetry Between the European Union and Africa? A Case Study of the EU’s Relations with Ghana and Senegal.” PhD diss., London School of Economics and Political Science.

- Vives, L. 2017a. “The European Union–West African sea Border: Anti-immigration Strategies and Territoriality.” European Urban and Regional Studies 24 (2): 209–224. doi: 10.1177/0969776416631790

- Vives, L. 2017b. “Unwanted Sea Migrants across the EU Border: the Canary Islands.” Political Geography 61 (11): 181–192. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.09.002

- Williams, D. 2000. “Aid and Sovereignty: Quasi-States and the International Financial Institutions.” Review of International Studies 26 (4): 557–573. doi: 10.1017/S026021050000557X

- World Bank Group . 2017. Migration and Remittances: Recent Developments and Outlook. Special Topic: Global Compact on Migration. Migration and Development Brief 27. Accessed March 27, 2019. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/29777 .