ABSTRACT

The literature on citizenship policies is flourishing, yet we know little of which naturalisation requirements majorities and minorities find reasonable, and how they view existing citizenship regimes. Drawing on original survey data with young adults in Norway (N = 3535), comprising immigrants and descendants with origins from Iraq, Pakistan, Poland, Somalia and Turkey, as well as a non-immigrant majority group, this article examines whether perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria and assessments of Norway’s current rules differ between groups. In terms of ideal citizenship criteria, we find a striking similarity across groups when looking at six different dimensions of citizenship policy. When merged into an index and estimated in a multivariate regression model, we find that both immigrants and descendants are significantly more liberal than natives are, yet the differences are small. When assessing the semi-strict citizenship regime in Norway, we find that immigrants are significantly more positive towards the current rules than natives. The results lend little support to recent work on ‘strategic’ and ‘instrumental’ citizenship and point instead to a close to universal conception of the terms of membership acquisition in Norway. This suggests that states may operate with moderate integration requirements while maintaining the legitimacy of the citizenship institution.

Introduction

What should it take to acquire a formal membership of a nation state? Although a vast literature has engaged with the development of European and North-American naturalisation policies, there is a striking lack of empirical studies of what individuals on the ground find to be fair requirements of naturalisation, and whether majorities and minorities differ in their perceptions.

On the one hand, one could expect immigrants and, to a somewhat lesser degree, native-born children of immigrants, to be more in favour of liberal naturalisation requirements (i.e. few constraints in accessing citizenship) compared to native majorities. The basic rationale of this proposition is that formal citizenship in a European or North American country is still a valuable good that affects mobility prospects and opportunities for democratic participation (Bauböck et al. Citation2013; Harpaz Citation2015; Harpaz Citation2019b; Moret Citation2017). Not only do strict criteria for naturalisation, such as long waiting time, demanding tests in language and societal knowledge and employment requirements, operate as de facto barriers to accessing such rights and opportunities, they also affect groups differently. Immigrants with low level of education, for example, have a harder time fulfilling demanding requirements (Jensen et al. Citation2019; Vink, Prokic-Breuer, and Dronkers Citation2013). Indeed, due to the global hierarchy of citizenship value, immigrants from less developed countries have the most to gain in accessing citizenship in Europe and North America (Harpaz Citation2015, Citation2019b; Kochenov and Lindeboom Citation2019), suggesting that these groups – and especially those who have not yet acquired a new citizenship – would favour liberal naturalisation requirements.

On the other hand, citizenship in a nation state not only concerns the instrumental access to security, rights and opportunities. Becoming a citizen through naturalisation also entails a change in membership, formally becoming part of a bounded community based on – at least ideally – shared ideas of solidarity and belonging. Of course, the idea of citizenship as a ‘sacred membership’ based on belonging to a single national community has lost much meaning in a globalised world (Harpaz Citation2019a; Joppke Citation2019). Yet as Kymlicka (Citation2019) has recently pointed out, diverse societies founded on liberal egalitarian ideas rest on an ethics of social membership that presupposes belonging, commitment and a sense of bounded solidarity amongst members of society. According to Kymlicka, such an ethics must be distinguished from the more overarching obligations to universal humanity, concerned with human personhood, dignity and linked to universal human rights. By contrast, an ethics of social membership is based on ‘claims we have on each other as members of a shared society, rooted in ideas of belonging and attachment to a particular society and territory, often articulated in the language of citizenship rights’ (Kymlicka Citation2019, 3).

Social membership in this sense is not only concerned with accessing rights and opportunities, but also with a deeper sense of solidarity in diverse societies (Banting and Kymlicka Citation2017a). While immigrants and other minority groups may feel less part of such mutual bonds of solidarity, for different reasons, we should not a priori assume that minority groups differ from majorities in their ideas of what it should take to become member of a nation state. If individuals with or without immigrant background ascribe importance to belonging, commitment and solidarity in a similar fashion and consider these values as important elements of citizenship, it would suggest that perceptions of membership acquisition is similar across groups.

Drawing on original survey data with young adults in Norway (N = 3535), comprising immigrants from Iraq, Pakistan, Poland, Turkey and Somalia, Norwegian-born individuals with parents from the same five origin countries, as well as a non-immigrant (native majority) group, this article examines whether perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria and assessments of the current rules applying in Norway differ between groups. Recent scholarship leads our expectations in two different directions: The ‘instrumentalist’ view on citizenship suggests that (especially non-EU) immigrants without a Norwegian citizenship are more in favour of liberal criteria since they have the most to gain. The ‘social membership’ view, by contrast, suggests that perceptions of reasonable requirements for citizenship are similarly distributed across groups, since individuals share a common sense of what membership in bounded communities entails. By analysing survey questions where respondents evaluate the reasonableness of key naturalisation requirements and assess the current rules in Norway, this article empirically assesses the relevance of these divergent propositions.

Comparing the views of immigrants, descendant of immigrants and majority natives offers a strong case for assessing the reasonableness in rules for membership acquisition through naturalisation. Immigrants in general are – by definition – more affected by naturalisation requirements than majority natives are, suggesting that their views are based on actual experience. Non-EU immigrants, which makes up the vast majority of our immigrant sample, represent, from an ‘instrumentalist’ perspective, a most likely case to be very critical of demanding naturalisation criteria, since the ‘value’ of their existing citizenship typically is much lower than immigrants from Europe and North America, especially concerning mobility prospects (Kochenov and Lindeboom Citation2019). Of course, how descendants of immigrants and not least majority natives view naturalisation requirements, is important in its own right. The descendants are still close to the bearings entailed in the citizenship institution, and the majority may be concerned about the sustainability of the existing polity and thereby wishing to raise the bar for membership. Brought together, data on how different groups in society assess naturalisation criteria and the existing citizenship regime in Norway offers a rare glimpse into the legitimacy of citizenship policies ‘from below’.

The Norwegian citizenship regime

Norwegian citizenship policies represent the middle-way in a Scandinavian and broader European context, although recently moving in a more restrictive direction (Midtbøen, Birkvad, and Erdal Citation2018). The acquisition of Norwegian citizenship at birth is based on the ius sanguinis principle. According to the main rule, a child acquires Norwegian citizenship at birth if a parent possesses Norwegian citizenship. For naturalisation, the main rule is that every person has upon application a right to citizenship if he or she meets the following requirements: evidence of identity; reached the age of 12; reside in Norway; and has spent a total of seven out of the previous 10 years in Norway with residence or work permits of at least one year’s duration. Furthermore, the person must hold or satisfy the conditions for a permanent residence permit and not have been sentenced to a penalty or special criminal sanction (Brochmann Citation2013).Footnote1 Until recently, applicants have been required to renounce their former citizenship if he or she does not automatically lose citizenship in another country when acquiring Norwegian citizenship. However, from January 2020 Norway accepts dual citizenship (Midtbøen Citation2019).

Concerning integration requirements, applicants must have documented language training and have passed tests in Norwegian and knowledge about society. Persons between 18 and 67 years of age must have completed 600 hours of approved tuition in the Norwegian language (including 50 hours of tuition in knowledge about society) or document sufficient knowledge of the Norwegian or Sami language and have passed an oral Norwegian test (on CEFR level A2), a fairly easy language requirement in comparative perspective (Goodman Citation2014). The applicant must also pass a citizenship test in which knowledge about Norwegian history, culture and society are documented. The test needs to be taken in Norwegian. All newly naturalised citizens are invited to a ceremony organised by the relevant County Governor. The ceremony has no legal function, and participation is voluntary. However, those who participate must pledge an oath of allegiance to the Norwegian state (Hagelund and Reegård Citation2011).

Theory and previous research

Norway’s gradual move towards a more restrictive citizenship regime is part of a broader shift in European citizenship policies since the late 1990s. Citizenship policy has re-gained saliency in national politics as part of wider, often sceptical debates about immigration, multiculturalism and social cohesion. Today, naturalisation requirements are often perceived as a basic tool in the efforts of the nation state to incentivize immigrants and their descendants to integrate (Brochmann and Hagelund Citation2011; Goodman Citation2014; Midtbøen Citation2015; Mouritsen Citation2013). The trend toward including integration requirements as conditions for naturalisation is referred to as the ‘civic turn’ in the citizenship literature (Borevi, Jensen, and Mouritsen Citation2017; Jensen, Fernández, and Brochmann Citation2017; Joppke Citation2007; Mouritsen, Jensen, and Larin Citation2019; Mouritsen and Olsen Citation2013). Indeed, during the last two decades, civic integration requirements regarding language, societal and cultural knowledge, employment and oaths have been introduced across Europe (Goodman Citation2014). These measures were prompted by concerns over ‘social cohesion’ in immigration receiving states due to a notion of failed immigrant integration (Bloemraad Citation2017; Joppke Citation2007). The turn to civic integration signals a shift in emphasis from a rights-based, legal equality-orientation, to an emphasis on duty and contribution: ‘it should take an effort’ to acquire citizenship.

Requiring integration by raising the bar for citizenship acquisition probably reflects a wish to fostering ‘good citizens’ (Brochmann and Hagelund Citation2012; Joppke Citation2017). However, stricter access to the national community may give rise to more prominent lines of division between insiders and outsiders – between those with and without access to the privileges of citizenship (Bloemraad Citation2017; Midtbøen, Birkvad, and Erdal Citation2018). Indeed, several recent studies have demonstrated that the level of strictness of naturalisation requirements do affect immigrants’ propensity to naturalise. Jensen et al. (Citation2019), for example, show that after 13 years in the country, less than 40 percent of refugees in Denmark are able to meet key civic integration requirements (language, economic self-sufficiency and no criminal offences) – the language requirement being the hardest to meet. Similarly, Vink, Prokic-Breuer, and Dronkers (Citation2013) find that accessible naturalisation requirements matter significantly for immigrants from less developed countries, suggesting that access to citizenship in countries with strict requirements depends on the immigrants’ level of education and available resources. Many scholars worry that the ‘civic turn’ in European countries’ citizenship policies will result in the permanent exclusion of substantial parts of the population from democratic participation. Bloemraad (Citation2017, 335), for example, suggests that ‘civic integration policies may erode rather than build democratic solidarity’.

While socioeconomic origins significantly affect citizenship acquisition, the groups who have the lowest likelihood of obtaining citizenship are also the groups who have most to gain. For immigrants originating from most countries outside the EU, naturalisation in an EU country dramatically increases their freedom to travel and work (Harpaz Citation2015; Harpaz and Mateos Citation2019). Citizenship in a stable democracy would furthermore provide legal stability to individuals who have experienced long periods of legal liminality; i.e. a fundamental uncertainty about one's legal status and right to stay (Birkvad Citation2019). The global hierarchy of citizenship that these examples indicate has been referred to as a ‘birthright lottery’ (Shachar Citation2009) and is perhaps most visible in the demand for dual citizenship. As Harpaz (Citation2019a) shows, this demand is particularly high in Latin America and non-EU Eastern European countries, where more than three million people have obtained a second citizenship from EU countries or the United States.

Existing empirical research on naturalisation policies and their effects suggests that easy access to citizenship indeed is in immigrants’ interest, and especially so for immigrants originating from countries outside the EU and North America. In a context of increasing focus on civic integration in Europe, one might even expect a growing divergence in views on fair requirements between majority natives and immigrant populations. The former are ‘gatekeepers’ of scarce goods – full membership in well-functioning polities and welfare states – while the latter might be driven by rational self-interest, aspiring to accomplish such a membership and enjoy the full spectrum of rights and opportunities attached to formal citizenship. Following this logic of self-interest, we would expect immigrants to be in favour of liberal naturalisation requirements. By contrast, we would expect majority natives to favour somewhat stricter requirements, and Norwegian-born descendants of immigrants to place themselves somewhere in between the other two groups. Following the logic of ‘affectedness’, we would furthermore expect that citizenship status matters, in the sense that, irrespective of immigrant background, those positing a Norwegian citizenship are somewhat more in favour of strict naturalisation requirements than those without Norwegian citizenship – the latter undoubtedly having the most to gain from easy access.

However, a less ‘instrumentalist’ (cf. Joppke Citation2019) view of citizenship suggests that individuals might share ideas about what membership in a bounded community entails, irrespective of their country-origins. Following Kymlicka (Citation2019, 5), the liberal egalitarian tradition of philosophical thought distinguishes between universal human rights and membership rights, the latter being anchored in the idea of citizenship rights as intimately connected with the national welfare state. According to Kymlicka (Citation2019, 11), social membership ‘only makes sense if people do indeed think of themselves as forming a shared society, and moreover, think that it is right and proper that they will continue to form a shared society into the future’. This position is derived from recent work on the sources of solidarity in diverse societies (Banting and Kymlicka Citation2017b), which suggests that social membership – a sense of ‘we’-ness – requires an effort of all actors involved. Indeed, as Banting and Kymlicka (Citation2017a, 3) point out, ‘self-interested strategic action alone is unlikely to generate a just society. […] Solidarity is sustained over time when it becomes incorporated into collective (typically national) identities and narratives.’ Similarly, Bauböck (Citation2017, 85), states that ‘if citizenship is over-inclusive in a way that undermines a shared sense of membership in the political community, or if it excludes those who are seen to belong, then solidarity will become disconnected from citizenship.’ Consequently, a certain level of strictness in requirements for acquiring formal membership in a nation state might signal that citizenship represents a collective identity in which members share a sense of belonging.

Whether such overarching ideas of an ‘ethics of membership’ (cf. Kymlicka Citation2019) have bearing on individuals’ perceptions of what constitute reasonable requirements for acquiring citizenship, remains an open question. However, the same goes for the literature on ‘strategic’ (Harpaz and Mateos Citation2019) and ‘instrumental’ (Joppke Citation2019) citizenship, which only indirectly indicates group-differences in assessments of requirements for naturalisation. Yet, the two perspectives point in opposite directions: The ‘social membership’ view suggest that perceptions of reasonable requirements for citizenship are similarly distributed across groups, while the ‘instrumentalist’ view suggests that immigrants – and especially those originating from non-EU countries, and those who have not already acquired a Norwegian citizenship – favour more liberal criteria compared to other groups.

Data and methods

This study builds on an original survey among young adults in Norway, comprising immigrants, descendants of immigrants and native majority Norwegians in the age group 20–36 years (N = 3535). The survey data is coupled with registry data from Statistics Norway that includes high-quality measures of immigrant background, citizenship status, educational level and occupational status. This rich set of registry data is advantageous for increasing the reliability of measurement on key variables. The use of registry data also diminishes the typical problems of self-report bias that can be a threat in survey responses (see e.g. Careja and Bevelander Citation2018; Chung and Monroe Citation2003; Donaldson and Grant-Vallone Citation2002).

The survey was conducted in the spring of 2018 by Statistics Norway and was a part of a larger Scandinavian survey that also included respondents in Denmark and Sweden. The Norwegian sample is unique in containing data on both immigrants and descendants of immigrants from five of the largest ethnic minority groups in Scandinavia – Somalia, Pakistan, Iraq, Turkey and Poland. The sample was stratified onto these 10 groups (first generation Somalis, second generation Somalis, first generation Pakistanis, etc.) while also including a group of native majority Norwegians. Majority natives are defined as Norwegian-born respondents with two Norwegian-born parents. Descendants of immigrants are defined as respondents that either were born in Norway by parents who immigrated to Norway from one of the countries of interest, or who immigrated to Norway before they were 11 years old. Hence, the group of descendants refers to both second and 1.5 generation immigrants (cf. Rumbaut Citation2004), but since the respondents in both cases have lived most of their lives in Norway we refer to them collectively as ‘descendants’ or ‘the second generation’. The immigrant category refers to people who themselves immigrated to Norway, who were older than 16 years when they immigrated and that had lived at least 7 years in Norway when the survey was conducted.Footnote2

The selection of the five immigrant-origin groups was guided by three main concerns. We wanted to include (1) groups that are relatively sizeable across the three Scandinavian countries; (2) the largest groups in each of the countries; and (3) variation across migrant categories, including older labour migrant groups (Pakistani, Turks), key refugee groups (Somali, Iraqis), and more recent labour migrants (Poles). However, to investigate whether perceptions of citizenship criteria differ according to how much individuals would gain from acquiring a Norwegian citizenship, we also wanted to include minority groups with background from countries with different ‘citizenship quality’. According to the Quality of Nationalities Index (QNI), Norwegian citizenship was ranked fourth in the world (2018), based on internal factors such as economic strength and human development, and external factors such as the possibility of visa-free travel and the ability to settle and work abroad (Kochenov and Lindeboom Citation2019). The ranking of the other five countries represents the entire spectrum of citizenship quality, from Poland (20) and Turkey (76) to Iraq (149) and Somalia (159).

Respondents were drawn by random sampling within each stratum and the survey was conducted by web and telephone. Those drawn to participate first received a web-link to the survey that was stated in Norwegian, as well as translated into Arab, English, Polish, Somali, Turkish and Urdu. After two weeks, a subsample of those who had not responded or had only partially completed the survey was contacted by telephone by an interviewer who had the appropriate language competences to conduct or finish the survey. This second round oversampled the groups that were underrepresented from the first round. 7.937 persons from the Norwegian registers were chosen to participate, of which approximately 50 percent answered the survey. Though minor skewness between the gross sample and the net sample is present, the skewness is generally rather small and does not pose significant challenges to the representativeness of the sample. An overview of the gross and net sample is provided in the appendix.Footnote3 As the table shows, 79 percent of the sample has a Norwegian citizenship while 21 percent do not. Among the immigrants in the sample, 37 percent do not have a Norwegian citizenship. The share of non-Norwegian citizens among the second generation and majority natives are 9 percent and zero, respectively.

Variables

Dependent variables

The study investigates two dependent variables: perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria and assessments of the citizenship criteria in Norway. The first variable, perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria, consists of questions relating to six different dimensions of naturalisation requirements: length of residence, language competence, economic qualifications, historical and cultural knowledge, dual citizenship, and declaration of citizenship commitment by oath. Within each of these questions, respondents were asked to indicate which requirements are in accordance with their opinion of acceptable requirements for citizenship. The answer categories ranged from no requirements/allow dual citizenship to categories reflecting very strict requirements. displays the full description of the questions and response categories, as well as the introductory text provided to the respondents.

Table 1. Six questions on perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria.

In the first part of the analysis regarding these ideal citizenship criteria, we look at each of the criteria separately. In the second part, we merge the six questions into one formative index that captures the overall perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria, i.e. how liberal or restrictive respondents are on average. Arguably, answers to the six questions are not caused by one underlying factor – respondents might reasonably hold that some requirements are important while others are not – but instead form or cause the overall restrictiveness of respondent’s attitudes towards ideal citizenship criteria (Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer Citation2001, 269–270). Though the formative index does not allow the same statistical tests of validation and reliability as the usual reflective scale development, collapsing such six dimensions of citizenship policy into one index is acknowledged and used in policy indices such as MIPEX, CIVIX and CITLAW (Jeffers, Honohan, and Bauböck Citation2017; Goodman Citation2014). The ideal citizenship criteria index is scaled from 0 (very liberal) to 1 (very restrictive), has a mean of 0.502 and a standard deviation of 0.183.

The second dependent variable, assessments of the actual Norwegian citizenship criteria, is measured by three items included at the very end of the survey questionnaire, where respondents were asked the extent to which they found the current citizenship rules in Norway to be (a) fair towards immigrants, (b) promote integration, and (c) good for the country. Respondents were presented with the actual criteria in NorwayFootnote4 before answering these three questions separately, on a scale from 1 (highly disagree) to 7 (highly agree). The three items were later merged into an index that measures the overall assessment of the actual citizenship criteria. The index proved to be a statistically valid and reliable measure of such assessments. Using an index instead of the three items individually both minimises random noise that is likely present in each item and offers a more nuanced measure of assessments of the actual citizenship criteria.Footnote5 The actual citizenship criteria index is scaled from 0 (very negative towards the actual rules) to 1 (very positive towards the actual rules), has a mean of 0.647 and a standard deviation of 0.251.

Independent variables

Immigrant background is the primary independent variable of the study. The variable consists of three categories: native majority Norwegians, descendants of immigrants (second generation) and immigrants (first generation). The five non-Norwegian origin groups – Somali, Pakistani, Iraqi, Turk and Polish – are in the main text collapsed into one second-generation group and one first generation group, respectively. This broad categorisation allows us to focus on the main similarities and differences between those originating from Norway (native Norwegians), those born and raised in Norway who have parents who do not originate from Norway (the second generation), and those born and raised elsewhere, who chose to settle in Norway (the first generation). As we also posit that there might be important variation between the groups’ perceptions of citizenship criteria, additional analyses of separate country of origin effects are included in the appendix and commented upon in the main text.

Control variables

We include the following background control variables from the Norwegian registers in the multivariate analyses to improve comparison between the different groups: gender, age, educational level, whether or not respondents have citizenship in Norway, whether or not respondents are employed, and the size of the city in which respondents live. Due to the structure of the registry data from Statistics Norway, it was not possible to use the age variable as a continuous measure. Age is therefore operationalised in three different categories: start-twenties (20–24 years), late-twenties (25–30 years) and thirties (31–36 years). Educational level is operationalised as the highest completed education or the educational level in which the respondent is currently attending. The variable contains three categories: secondary education or less (< 11 years of education), further education (11-14 years of education) and higher education (14+ years of education). In cases where respondents' highest completed education is ‘further education’ while he or she is currently attending a higher education, the respondent is coded as having a higher education level.

Of course, education, citizenship status, employment status and city size are not control variables in a strict sense, i.e. potential causes of both immigrant background and citizenship attitudes that hence could confound the relationship of interest (Angrist and Pischke Citation2015; Stock and Watson Citation2015). Instead, they constitute ‘usual suspects’ in terms of potentially explaining why differences between group attitudes may exist. Including these control variables in the models below does not imply that we aim to make causal claims about the direct effects of immigrant background on citizenship attitudes. Rather, we control for these factors in order to move closer to the core differences between groups in their views of citizenship criteria.

Results

Perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria

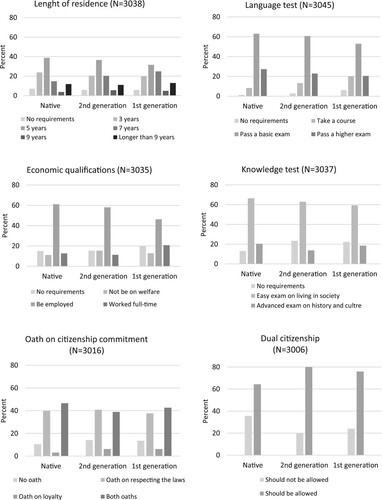

The first part of the following analysis focuses on each of the six different dimensions of citizenship requirements. displays the simple distribution of answers among majority natives, second generation and immigrants, and point to a quite astonishing similarity across these groups. The figure shows that the three groups seem to follow the same pattern in their perception of all ideal citizenship criteria. Further, the small differences that do exist do not seem to reveal a clear pattern. For example, while both immigrants and the second generation are more in favour of allowing dual citizenship than majority natives are, a higher share among the immigrants answer that full-time work – the strictest option concerning economic qualifications – should be a requirement for citizenship. Most strikingly, there seems to be a ‘typical’ response across dimensions, which suggests favouring rather moderate citizenship rules. The typical response across all groups is that, to obtain citizenship, applicants must have lived 5 years in the country, passed a basic language exam, be employed, passed an easy exam on living in society, make a declaration on respect for the laws of the country, and be allowed dual citizenship. Such universality in the distribution of the typical response is at odds with the ‘instrumentalist’ view that immigrants would have considerably more liberal perceptions of reasonable citizenship rules, compared to majority native Norwegians, and more in line with the ‘social membership’ view that an effort ought to be made, to become a full member of the national community.

Figure 1. Perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria distributed on each citizenship criterion by macro group.

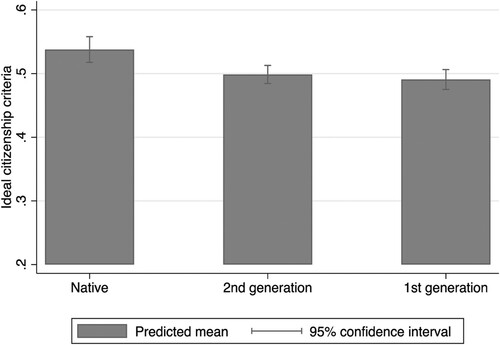

To investigate the aggregate differences in perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria, we created an index of the six dimensions. Model 1 in indicates that despite the similar distributions in , both immigrants and the second generation are significantly less restrictive, compared to native Norwegians, once we look at the aggregate measure. That is, both groups, on average, tend to favour more liberal citizenship rules compared to natives. However, these differences are quite small considering the scaling of the dependent variable from 0 to 1.

Table 2. Estimating perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria.

Model 2 in controls for gender, age, education, citizenship status, employment and city size. Though the effect sizes change somewhat, the overall picture is robust: both immigrants and the second generation are significantly more liberal than native majority Norwegians. Among the second generation, the effect size is smaller than in model 1. This indicates that some of the effect among this group goes through one of the control variables. This variable is primarily city size: More second-generation respondents live in larger cities, and living in larger cities correlates with more liberal perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria compared to living in a smaller city (a city with less than 20.000 inhabitants).

From model 2, it also seems that women are more liberal than men, and that individuals with higher education are more liberal than those with lower levels of education are. Having Norwegian citizenship, somewhat surprisingly, is also associated with more liberal perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria, than not having it. Additional analyses (not shown) suggest that this goes for both the first and the second generation; that is, Norwegian citizens in both of these groups are in fact significantly more liberal compared to non-citizens. Employment and age, by contrast, does not seem to correlate with one’s perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria. It is worth noting the rather low explanatory power of both model 1 and 2. This suggests that none of the independent variables seem to be strong predictors of ideal citizenship rules in Norway.

In , we have conducted the same analyses as in , but distinguished between origin groups. Overall, the conclusions hold across the subgroups. In terms of perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria, all groups are significantly more liberal compared to natives, except for Iraqis and Poles of both the first and second generation, who are not significantly different from the native majority reference group. Somalis of both the first and second generation are those in favour of the most liberal requirements. Somali citizens would have the most to gain from obtaining a Norwegian citizenship, as Somali citizenship has the lowest value according to the QNI, suggesting a possible relationship between self-interest and liberal attitudes toward citizenship rules. However, the respondents originating from Iraq, the second lowest-QNI-ranked citizenship in our sample, do not differ significantly from the native majority.

presents the predicted mean level of perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria among majority natives, the second generation, and immigrants, based on model 2 in . The figure indicates that the three groups remain quite similar in numerical terms: natives have a predicted mean of 0.538, whereas the second generation has a predicted mean of 0.499 and immigrants have a predicted mean of 0.491. Even though the difference between natives and immigrants is statistically significant, the difference is very small in substantial terms. Again, this points to a surprising similarity between groups in perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria.

Assessments of actual citizenship criteria

So far, we have focused on the different groups’ perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria. However, we cannot take for granted that the general public are aware of what is actually required to acquire Norwegian citizenship, and perceptions of ideal criteria do not tell us much about the legitimacy of the current citizenship regime. How do immigrants, the second generation and majority natives assess the criteria for actual citizenship acquisition in Norway?

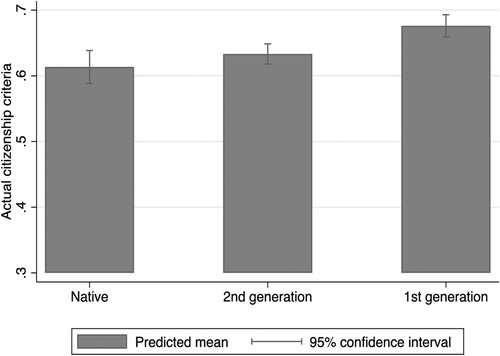

To answer this question, we analyse the index of the overall assessment of the citizenship criteria currently used in Norway, where respondents were asked to evaluate whether the rules are fair towards immigrants, promote integration, and are good for the country. shows the results of a regression on the overall assessment of the current Norwegian citizenship requirements. Model 1 presents the bivariate relationship between the three groups and assessments of the actual citizenship rules in Norway. In this simple model, only immigrants have different assessments than native majority Norwegians and in a positive direction, i.e. immigrants tend to be more positive towards the actual citizenship criteria, compared to both majority natives and the second generation. Controlling for the same variables introduced earlier (model 2) does not change the conclusion from model 1. However, we see from model 2 that those holding a Norwegian citizenship are significantly more positive to the current rules compared to those without a Norwegian citizenship.

Table 3. Estimating assessment of actual Norwegian citizenship criteria.

In in the appendix, we have run the same models but distinguished between origin groups. Again, the overall pattern holds. No second-generation group differs significantly from the native majority, except for second generation Poles, who are significantly more positive towards the actual citizenship rules. All immigrant groups are significantly more positive towards the current rules than the majority, except immigrants from Poland, where we find no statistically significant difference. Consequently, and in contrast to the instrumentalist view, non-EU immigrant groups are the ones most in favour of the current, semi-strict citizenship regime in Norway.

shows the predicted mean level of the assessments of actual citizenship criteria. Though majority natives on average are leaning towards being more positive than negative, with a predicted mean of 0.613, the second-generation group seems slightly more positive, with a mean of 0.630 (which is not significantly different from the native mean), exceeded by immigrants who have a predicted mean of 0.681. Thus, considering the current rules in Norway, all the groups are clearly more in favour of the rules than against them, but majority natives remain significantly more sceptical compared to immigrants.

Discussion and conclusion

While a large body of work exists on the development and effects of citizenship policies in Europe and North America (e.g. Goodman Citation2014; Harpaz Citation2019b), no prior study has examined what individuals on the ground find are reasonable requirements for becoming a formal member of a nation state. This article has analysed whether perceptions of ideal citizenship criteria differ between immigrants, descendants of immigrants and the native majority in Norway, as well as whether the three groups differ in their assessments of the actual citizenship criteria in the country.

In terms of ideal citizenship criteria, we find a striking similarity in the median response as well as in the distribution of responses, when looking at six different dimensions of citizenship policy. Interestingly, there seems to exist a close to universal understanding of a certain level of strictness in the perceptions of what it should take to get Norwegian citizenship. The typical response across all the groups is that immigrants – to obtain citizenship – must have lived 5 years in the country, have passed a basic language exam, be employed, have passed an easy exam on living in society, make a declaration on respect for the laws of the country, and be allowed dual citizenship. When merged into an index and estimated in a multivariate regression model, we find that both immigrants and descendants of immigrants are significantly more liberal than majority natives are. This goes for all groups except Iraqis and Poles of both the first and the second generation. Respondents with a Somali background are the most liberal. However, the differences, even at the subgroup-level, are small.

In terms of assessments of actual citizenship criteria, we find that immigrants are significantly more positive towards the rules than native Norwegians are, but these differences are small too. The difference between the native majority and descendants of immigrants is not statistically significant. On average, all groups seem to agree that the current requirements are fair towards immigrants, promote integration, and are good for the country, and the most positive are in fact immigrants originating from the four non-EU countries. Consequently, the overall conclusion of our study is that immigrant status matters little for assessments of citizenship criteria: Across groups, we find support for a certain level of strictness in accessing citizenship, and we find striking similarities in the favourable views on the current, semi-strict citizenship regime in Norway.

These results are interesting in light of recent work on ‘strategic’ (Harpaz and Mateos Citation2019) and ‘instrumental’ (Joppke Citation2019) citizenship, which would lead us to expect that the ones most affected by the policies would be most in favour of easy access. How, then, could we explain the striking similarities across groups and the fact that immigrants show a preference for a certain strictness in naturalisation requirements? One explanation might be that membership in a nation state still matters to people in a substantial way. Although a formal citizenship provides immigrants with both legal security, voting rights and valuable mobility opportunities, all groups included in this study – regardless of immigrant status – agree that citizenship should require an effort to integrate on the part of the newcomer. However, all groups also seem to agree that the criteria should not be too restrictive. The preferred integration requirements are rather moderate, and dual citizenship should be allowed. This suggests that, for immigrants, citizenship is not simply a matter of strategic choice (cf. Harpaz and Mateos Citation2019), but that residence and integration remain important aspects of membership.

Of course, a simpler answer to this question could be that young adults in general may not have very strong opinions on what it should take to acquire citizenship, and that they therefore cluster in the middle of the scale (cf. Deli Carpini and Keeter Citation1996; Zaller and Feldman Citation1992). However, such an interpretation ignores that, especially for immigrants originating from countries outside of the EU, a Norwegian citizenship is undoubtedly an important resource, suggesting that for this group the level of strictness in citizenship criteria is indeed a salient issue. The simple interpretation is also countered by the surprising fact that respondents without a Norwegian citizenship – who clearly have most to gain from easy access – are significantly less liberal than respondents with a Norwegian citizenship. That we indeed find support for a certain strictness in citizenship criteria across groups is finally backed up by the second key finding in this study, namely that when confronted with the actual, semi-strict requirements for citizenship in Norway, immigrants from non-EU countries are significantly more positive than majority natives are. This suggests that moderate requirements for citizenship indeed do appear as reasonable for those most directly affected by the policies.

In our view, the results appear to be more in line with recent work on the ‘ethics of social membership’ (Banting and Kymlicka Citation2017a; Kymlicka Citation2019). In contrast to conceptions of justice based on universal humanism, which is anchored in universal human rights, conceptions of justice based on membership, according to Kymlicka (Citation2019, 9), are ‘crystallized in the idea of citizenship rights and the national welfare state’. Membership in a bounded community, such as the nation state, to which citizenship policies and laws regulate formal access, depends on all members having a moral commitment and that they engage in continuous efforts to produce and reproduce a salient ‘we’. Indeed, as Bauböck (Citation2017, 85) points out, ‘if citizenship is perceived to be purely instrumentally valuable as a set of entitlements vis-à-vis states (such as those of free movement that come with a European passport) without corresponding responsibilities, then it is unlikely to be effective as a source of solidarity’.

This study suggests that both majorities and minorities, on average, agree that citizenship is not purely valuable as a set of entitlement vis-à-vis the Norwegian state. The naturalisation requirements preferred by respondents are somewhat stricter than the actual requirements for obtaining Norwegian citizenship, and immigrants from non-EU countries are significantly more positive to the current rules, compared to both majority natives, the second generation and EU (Polish) immigrants. These findings support an idea of social membership that requires an effort of all parties involved, including the immigrant groups who have the most to gain from accessing membership.

Of course, our findings cannot shed light on the relative importance of the rather technical questions posed in this study – precisely which requirements should newcomers fulfil to access citizenship? – compared to other important dimensions of the immigration/citizenship nexus, such as access to the country, national security and acceptance as full-fledged members of the nation. The striking similarities in views on citizenship requirements across the groups included in this study pertains only to the last gate of formal acceptance in the nation state. Prior to this stage, there is the basic question of rules of access to the territory, which concerns the realm of immigration policy, and rules of access to social and economic rights, which concerns the realm of welfare policy (Brochmann and Hagelund Citation2012). During the gradual process of integration and eventually naturalisation, as well as after gaining formal citizenship, there is furthermore the contentious nationhood aspects of everyday citizenry, affecting the extent to which immigrants and their children feel that they belong to, and are accepted as part of, the broader, national community (Erdal Citation2019; Erdal, Doeland, and Tellander Citation2018). The legitimacy of formal naturalisation requirements only indirectly touches upon these issues, suggesting that questions of access, belonging and acceptance will remain contested, regardless of views on rules of naturalisation.

The similarities across groups in views of ideal and current criteria for accessing a formal citizenship in Norway are nevertheless striking. Yet, the explanations for our findings remain somewhat speculative. We cannot know why the differences between groups are relatively small, and without a comparative dataset, we cannot assess directly the influence of historical traditions of citizenship on current perceptions of naturalisation criteria among groups of different immigrant status. Thus, our findings warrant more research on how ordinary people – both majority natives and the immigrant-origin population – view citizenship, and how such views vary across different national contexts.

Still, our results point clearly in the direction that naturalisation requirements at a certain level of strictness are viewed as reasonable both among those directly affected, and among those who are not. This suggests that citizenship – in the eyes of individuals on the ground – continues to matter. It may also imply a certain level of reflection and agency among minority members of the citizenry, on behalf of the nation state: It takes an effort to create a functioning plural society and to maintain legitimacy among the constituency. Our findings indicate that new citizens, to a surprising extent, blend in as gatekeepers of scarce goods together with the majority, whereas the majority, maybe also to a surprising extent, welcomes new citizens to the national community, with expectations and requirements that are within reach. In sum, our results suggest that nation states may operate with moderate integration requirements, while simultaneously maintaining the legitimacy of the citizenship institution – among both majority natives and the immigrant-origin population.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a larger Scandinavian comparative project, Governing and experiencing citizenship in multicultural Scandinavia (GOVCIT). All the listed authors have contributed to the survey design, the analyses and the writing. However, A.H.M. is the lead author of the article and M.K. was mainly responsible for the data analyses. We thank Will Kymlicka and Maarten Vink, as well as two anonymous reviewers, for valuable comments and suggestions to a previous version of the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Nordic citizens have much easier access to citizenship in Norway, e.g. only two year of waiting time is required. Persons who have been sentenced to a penalty or a special criminal sanction cannot acquire Norwegian citizenship until a waiting period (depending on the gravity of the criminal action) has been endured (Midtbøen, Birkvad, and Erdal Citation2018).

2 As a result, the youngest immigrants in the sample are 23 years old. Overall, the groups’ age span is somewhat different (immigrants 23–36; descendants 20–30; native majority 20–36). Due to the generally narrow age range of our population (20–36 years), we assume that this does not pose a challenge to the analyses. Indeed, in our models, age does not correlate with perceptions of naturalization criteria nor with assessments of the actual citizenship regime. Further, including age to the models does not add any explanatory power, and including or removing age from the models does not change the general conclusions of the differences between natives, descendants and immigrants.

3 Note the difference between the net sample in (N = 4031) and the net sample in this article (N = 3535). The reason for this discrepancy is that the original sample also included a group of second-generation Vietnamese who are excluded from this sample because a first generation immigrant comparison-group could not be included.

4 The rules were described as the following: Most immigrants must have a clear identity; reside in Norway with a wish to live in the country in the future; have lived in Norway in 7 out of the last 10 years; have permanent residency or fulfill the requirements for such residency; have given up citizenship in the country of origin; not be convicted of any crime; and have completed the proper courses in Norwegian language as well as passed tests in Norwegian language and knowledge of society (cf. the section on the Norwegian citizenship regime).

5 A principal component factor analysis of the three items indicated that only one factor had an eigenvalue above 1 (2.22) on which the items had high loadings (between 0.80 and 0.90). This suggests that the three items all reflect the same latent construct. The scale had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82.

References

- Angrist, J. A., and J.-S. Pischke. 2015. Mastering ‘Metrics: The Path From Cause to Effect. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Banting, K., and W. Kymlicka. 2017a. “Introduction: The Political Sources of Solidarity in Diverse Societies.” In The Strains of Commitment: The Political Sources of Solidarity in Diverse Societies, edited by K. Banting and W. Kymlicka, 1–58. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Banting, K., and W. Kymlicka. 2017b. The Strains of Commitment: The Political Sources of Solidarity in Diverse Societies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bauböck, R. 2017. “Citizenship and Collective Identities as Political Sources of Solidarity in the European Union.” In The Strains of Commitment: The Political Sources of Solidarity in Diverse Societies, edited by K. Banting and W. Kymlicka, 80–106. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bauböck, R., I. Honohan, T. Huddleston, D. Hutcheson, J. Shaw, and M. Vink. 2013. Access to Citizenship and Its Impact on Immigrant Integration: European Summary and Standards. Badia Fiesolana: European University Institute.

- Birkvad, S. R. 2019. “Immigrant Meanings of Citizenship: Mobility, Stability, and Recognition.” Citizenship Studies 23: 798–814. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2019.1664402.

- Bloemraad, I. 2017. “Solidarity and Conflict: Understanding the Causes and Consequences of Access to Citizenship, Civic Integration Policies, and Multiculturalism.” In The Strains of Commitment: The Political Sources of Solidarity in Diverse Societies, edited by K. Banting, and W. Kymlicka, 327–363. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Borevi, K., K. K. Jensen, and P. Mouritsen. 2017. “The Civic Turn of Immigrant Integration Policies in the Scandinavian Welfare States.” Comparative Migration Studies 5 (1): 9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-017-0052-4.

- Brochmann, G. 2013. Country Report: Norway. EUDO Citizenship Observatory. Badia Fiesolana: European University Institute.

- Brochmann, G., and A. Hagelund. 2011. “Migrants in the Scandinavian Welfare State: The Emergence of a Social Policy Problem.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 1 (1): 13–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/v10202-011-0003-3.

- Brochmann, G., and A. Hagelund. 2012. Immigration Policy and the Scandinavian Welfare State, 1945-2010. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Careja, R., and P. Bevelander. 2018. “Using Population Registers for Migration and Integration Research: Examples From Denmark and Sweden.” Comparative Migration Studies 6 (1): 19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s40878-018-0076-4.

- Chung, J., and G. S. Monroe. 2003. “Exploring Social Desirability Bias.” Journal of Business Ethics 44: 291–302. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023648703356

- Deli Carpini, M. X., and S. Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know About Politics and Why It Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Diamantopoulos, A., and H. M. Winklhofer. 2001. “Index Construction with Formative Indicators: An Alternative to Scale Development.” Journal of Marketing Research 38 (2): 269–277. doi: https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.2.269.18845

- Donaldson, S. I., and E. J. Grant-Vallone. 2002. “Understanding Self-Report Bias in Organizational Behavior Research.” Journal of Business and Psychology 17 (2): 245–260. doi: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1019637632584

- Erdal, M. B. 2019. “Negotiation Dynamics and Their Limits: Young People in Norway Deal with Diversity in the Nation.” Political Geography 73: 38–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.05.010.

- Erdal, M. B., E. M. Doeland, and E. Tellander. 2018. “How Citizenship Matters (or not): the Citizenship–Belonging Nexus Explored among Residents in Oslo, Norway.” Citizenship Studies 22 (7): 705–724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2018.1508415.

- Goodman, S. W. 2014. Immigration and Membership Politics in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hagelund, A., and K. Reegård. 2011. “‘Changing Teams’: a Participant Perspective on Citizenship Ceremonies.” Citizenship Studies 15 (6-7): 735–748. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2011.600087.

- Harpaz, Y. 2015. “Ancestry Into Opportunity: How Global Inequality Drives Demand for Long-Distance European Union Citizenship.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (13): 2081–2104. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2015.1037258.

- Harpaz, Y. 2019a. Citizenship 2.0: Dual Nationality as a Global Asset. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Harpaz, Y. 2019b. “Compensatory Citizenship: Dual Nationality as a Strategy of Global Upward Mobility.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (6): 897–916. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440486.

- Harpaz, Y., and P. Mateos. 2019. “Strategic Citizenship: Negotiating Membership in the age of Dual Nationality.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (6): 843–857. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440482.

- Jeffers, K., I. Honohan, and R. Bauböck. 2017. How to Measure the Purposes of Citizenship Laws: Explanatory Report for the CITLAW Indicators. Badia Fiesolana: European University Institute. http://globalcit.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/CITLAW_3.0.pdf.

- Jensen, K. K., C. Fernández, and G. Brochmann. 2017. “Nationhood and Scandinavian Naturalization Politics: Varieties of the Civic Turn.” Citizenship Studies 21 (5): 606–624. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2017.1330399.

- Jensen, K. K., P. Mouritsen, E. C. Bech, and T. V. Olsen. 2019. “Roadblocks to Citizenship: Selection Effects of Restrictive Naturalisation Rules.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1667757.

- Joppke, C. 2007. “Transformation of Immigrant Integration: Civic Integration and Antidiscrimination in the Netherlands, France, and Germany.” World Politics 59 (2): 243–273. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2007.0022.

- Joppke, C. 2017. “Civic Integration in Western Europe: Three Debates.” West European Politics 40 (6): 1153–1176. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01402382.2017.1303252.

- Joppke, C. 2019. “The Instrumental Turn of Citizenship.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (6): 858–878. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1440484.

- Kochenov, D., and J. Lindeboom. 2019. Kälin and Kochenov’s Quality of Nationality Index: Nationalities of the World in 2018. Oxford: Hart Publishing.

- Kymlicka, W. 2019. “The Ethics of Membership in Multicultural Societies.” Paper presented at the closing conference of the GOVCIT project, Oslo, Norway.

- Midtbøen, A. H. 2015. “Citizenship, Integration and the Quest for Social Cohesion: Nationality Reform in the Scandinavian Countries.” Comparative Migration Studies 3 (3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40878-015-0002-y.

- Midtbøen, A. H. 2019. “Dual Citizenship in an Era of Securitisation: The Case of Denmark.” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 9 (3): 293–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.2478/njmr-2019-0014.

- Midtbøen, A. H., S. R. Birkvad, and M. B. Erdal. 2018. Citizenship in the Nordic Countries: Past, Present, Future. Copenhagen: The Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Moret, J. 2017. “Mobility Capital: Somali Migrants’ Trajectories of (im) Mobilities and the Negotiation of Social Inequalities Across Borders.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.12.002.

- Mouritsen, P. 2013. “The Resilience of Citizenship Traditions: Civic Integration in Germany, Great Britain and Denmark.” Ethnicities 13 (1): 86–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796812451220.

- Mouritsen, P., K. K. Jensen, and S. J. Larin. 2019. “Introduction: Theorizing the Civic Turn in European Integration Policies.” Ethnicities 19 (4): 595–613. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796819843532.

- Mouritsen, P., and T. V. Olsen. 2013. “Denmark Between Liberalism and Nationalism.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (4): 691–710. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2011.598233.

- Rumbaut, R. G. 2004. “Ages, Life Stages, and Generational Cohorts: Decomposing the Immigrant First and Second Generations in the United States.” 38 (3): 1160–1205. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2004.tb00232.x.

- Shachar, A. 2009. The Birthright Lottery: Citizenship and Global Inequality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Stock, J. H., and M. W. Watson. 2015. Introduction to Econometrics (3rd ed.). Harlow: Pearson.

- Vink, M. P., T. Prokic-Breuer, and J. Dronkers. 2013. “Immigrant Naturalization in the Context of Institutional Diversity: Policy Matters, but to Whom?” International Migration 51 (5): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12106.

- Zaller, J., and S. Feldman. 1992. “A Simple Theory of the Survey Response: Answering Questions Versus Revealing Preferences.” American Journal of Political Science 36 (3): 579–616. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2111583.