ABSTRACT

How do migrants become part of a national community and feel a sense of belonging to that country? Whilst migrants’ educational level is considered key in doing so, survey studies conclude that higher-educated migrants experience a low sense of belonging to the residence country. This has been dubbed the integration paradox. We draw from in-depth qualitative biographical interviews with highly-skilled Turkish migrants in the Netherlands to contribute to understanding how this so-called paradox can come about. Purposeful sampling from the New Immigrants Survey allows for rich data that reflect those who, according to the survey, experience a paradox (N = 15) and those who do not (N = 17). First, we find that some migrants interpret national belonging in more complex ways than was intended by often-used survey items measuring this concept. Many highly-skilled migrants experience little belonging to a single nation, but instead identify with a supranational entity. Some self-identified world citizens are therefore categorised as ‘paradoxical’ because they experience belonging nowhere in specific. Second, we find multiple conditions that structure (non-)belonging, such as experiencing non-belonging due to exclusion from both Dutch and Dutch-Turkish communities, and might explain the paradox. These insights shed new light on the mechanisms underpinning the integration paradox.

Introduction

In the last decade, due to political and economic changes in Turkey more and more highly-skilled Turkish migrants have become part of the largest immigrant group in Western Europe. While Western-European countries, such as the Netherlands, are said to need to attract high-skilled migrants in order to sustain their labour market and to ensure an innovative future (OECD Citation2016), the integration of migrants, particularly from Muslim-majority countries, is considered a growing concern (Simonsen Citation2017). In this debate, it is often stressed that the prerequisite for a well-functioning society are shared feelings of belonging (De Vroome, Verkuyten, and Martinovic Citation2014). Moreover, belonging also matters for individual migrants as it enhances quality of and meaning in life, amongst others (Lambert et al. Citation2013; Yuval-Davis, Kannabiran, and Vieten Citation2006).

Among the key elements for obtaining a sense of national belonging is migrants’ educational level. Simply put, it is supposedly easier to belong when one has socio-economic ‘success’ in the residence society and is more exposed to prevailing norms and values (Reeskens and Wright Citation2014). Surprisingly, however, recent survey studies, mainly on Turkish migrants (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2019), conclude that particularly higher-educated migrants mentally turn away from the residence country (Steinmann Citation2019; De Vroome, Martinovic, and Verkuyten Citation2014). This counterintuitive finding, encompassing not just higher perceived discrimation, but lower cultural or emotional integration to which national belonging is an indicator, is considered the integration paradox in the wide sense (Steinmann Citation2019; Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013; Verkuyten Citation2016). We will contribute to previous studies by exploring underlying processes of this paradox and aim to inform our understanding of the integration paradox by taking an in-depth look at the group that deviates from the theoretical expectations, in order to generate new theoretical insights on why higher-education might not link to stronger belonging. In contrast to the predominantly quantitative approach in the existing integration paradox studies, we draw from in-depth interviews and build on personal experiences of highly-skilled Turkish migrants. Our main research question reads: How to understand a low sense of national belonging among highly-skilled Turkish migrants?

In our study, we will combine the literature on belonging (Yuval-Davis, Kannabiran, and Vieten Citation2006) with the literature on the integration paradox. Established knowledge in the literature on belonging allows us to come up with frameworks than can be applied when analysing the conducted interviews. Linking these two strands of literature allows for finding processes that provide a next step in understanding what shapes belonging and the paradox.

Empirically, we draw from life history interviews with 32 recent high-skilled Turkish migrants who moved to the Netherlands in 2012 and 2013. Our qualitative biographical interviews capture processes that go beyond existing survey data (Verkuyten Citation2016), but we purposefully sampled informants were from the New Immigrants Survey (Lubbers et al. Citation2018) to uniquely assure maximum alignment with the survey observing the paradox. In contrast to the, few, existing qualitative studies on this topic (i.e. Eijberts and Ghorashi Citation2017; Eijberts, Ghorashi, and Rouvoet Citation2017), we take the survey measurements to select higher-educated migrants who have and do not have a paradox. This way we can better assess the underlying mechanisms and inform previous studies and the survey literature accordingly.

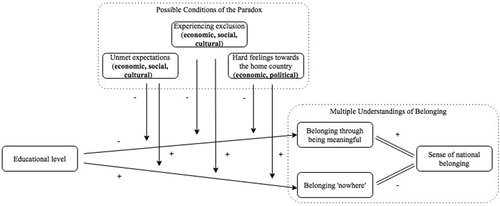

Our results indicate two main strands of explanations. First, migrants’ understanding of belonging matters in finding a paradox or not when using survey data. Highly-skilled migrants tend to self-identify as a world- rather than a national citizen. As a result, some migrants experience no specific belonging to any nation state, including the Netherlands, and answer negatively on a survey-item on experiencing belonging to the Netherlands. Moreover, a dimension of national belonging that migrants seem to have in mind thinking about belonging has not been captured in survey data and concerns the experience of being able to contribute to the Netherlands or not, again leading to low belonging answers. Such various interpretations of national belonging partly overrule the way national belonging was intended to be captured in survey items. Second, we found three new conditions of what might create a lower sense of belonging, which are particularly relevant for higher-educated immigrants: having high expectations that do not meet reality; experiencing social exclusion from both Dutch natives and second-generation Dutch Turks, and experiencing guilt towards Turkey and for leaving the country.

The case of recent Turkish migrants in the Netherlands

The Netherlands has a rich history with respect to migration from Turkey. Official agreements for labour migration brought many low-skilled Turkish citizens to the Netherlands around the 1960s and 1970s. Most migrants came from small villages in central Turkey or along the Black Sea coast (Crul and Vermeulen Citation2003). Migration motives first centred around labour and later around family reunion.

From the 2000s onwards, migrating due to political reasons has become increasingly prevalent. The change in government in Turkey in the early 2000s brought about a more religious nationalist regime, which caused especially high-skilled people to emigrate (Elveren Citation2018). In the Netherlands, 6809 Turkish migrants arrived in 2018, in 2015 this number was only 3747 (Statistics Netherlands Citation2019). These recent migrants mainly include well-to-do individuals and academics from larger cities such as Istanbul, Izmir and Ankara.

A focus on these recent migrants is important and adds to previous quantitative studies on the integration paradox as well as qualitative studies on belonging which tend to revolve around longer-established first-generation or second-generation migrants. Focussing on the first years after migration provides insights into arguably the most dynamic years, in which foundations are laid for future integration into the residence country (Kristen, Mühlau, and Schacht Citation2016). A seemingly paradoxical negative link between educational level and sense of belonging has been found among this group of migrants (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2019), and here we aim to explore (new) explanations for this link, as previous studies do not provide a full explanation.

The integration paradox

According to classic assimilationist theories, integration processes are interpreted as having multiple dimensions which follow each other in a linear fashion (Alba and Nee Citation2009; Gordon Citation1964). Following this linearity notion, it is assumed that integration into one domain will on average bring about integration into another domain. If one becomes more educated for example, this supposedly enhances belonging to the residence country (Eijberts and Ghorashi Citation2017).

Recent survey-based studies have however concluded that migrants’ educational level does not necessarily have this supposed effect on migrants’ sense of belonging (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2019; Verkuyten Citation2016; Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013). Instead, migrants who are considered structurally ‘integrated’ seem to disengage from the residence country. Previous studies have tested two main and closely-related mechanisms to explain this paradox. The first is perceived group discrimination, the second perceived group non-acceptance (i.e. is the residence country welcoming to their ethnic group). These two mechanisms appear to explain the paradox among recent migrants only partially; after accounting for them in regression models, the negative effect of educational level on sense of belonging to the Netherlands remains in most instances (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2019).

In most paradox studies explanations for a sense of national belonging (often referred to as host-country identification) are theorised, while measurements are mainly based on how migrants feel about the native population or country (the most frequently used questions are ‘How do you feel towards Dutch natives?’ and ‘What is your opinion on the Dutch society?’). Guided by the survey items available, a sense of belonging is hereby studied from a rather specific angle. Often, migrants’ feelings towards society are measured rather than their identification with such entities (as argued by Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2019). These observations stand in contrast to the broader approach in the conceptual belonging literature. Considering and exploring this is crucial since a discrepancy between the measurement and the theoretical concept might help explain the paradox as findings can depend on how respondents perceive belonging versus how belonging is caputered in survey items. In short, we argue that insight in the concept of belonging can complement the paradox literature.

Concepts of belonging

Previous studies on belonging give us guidelines for important distinctions and frameworks when studying (national) belonging, and this study underscores that belonging is best understood as an entanglement of multiple and intersecting relations, reflecting relational dimensions of inclusion and exclusion (Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2016). We will discuss three frameworks in specific: dialogical and performative belonging, mixed embeddeness, and multidimensional embeddedness. These three frameworks will later be applied as tools when analysing the interviews and understanding what questions regarding belonging might allude to respondents.

Dialogical and performative belonging

The construction of belonging is a narrative as it is about ‘stories people tell themselves and others about who they are (and who they are not)’ (Yuval-Davis Citation2006, 202). In ‘telling these stories’ a sense of belonging not only includes emotional attachments, but also a feeling at home and feeling safe (De Bree, Davids, and De Haas Citation2010; Yuval-Davis Citation2006). Belonging can hereby be both dialogical and performative (Yuval-Davis, Kannabiran, and Vieten Citation2006). Dialogically, belonging is constructed in relation to others, which thus brings about one’s positioning. Belonging is not only about how one sees oneself but also how one relates to others, and how others relate to you. An example for national belonging is whether one feels part of the native population and whether the residence country is part of one’s identity construction. The items used in previous paradox studies seemingly focus on this dialogical aspect of belonging, as they focus on identification towards a nation or its population. The performative aspect of belonging refers to certain (repetitive) practices that bring about emotional attachments (Yuval-Davis Citation2006), such as celebrating certain national holidays or using a certain language.

Mixed embeddedness

Since belonging is also constructed by the ways one is valued and judged by others (Latcheva and Herzog-Punzenberger Citation2011), the concept of mixed embeddedness was introduced to study the interplay and mix between agency and structure, which shapes one’s sense of belonging (Kloosterman Citation2010). Belonging is thus subjectively felt, but is never a private feeling. Individual belonging is continuously enabled, transformed and negotiated by one’s context, in which processes of boundary drawing and external categorisation take place (Yuval-Davis Citation2006; Simonsen Citation2017). These circumstances can be inclusionary and/or exclusionary, which are likely to shape one’s individual experience of belonging. Examples of such structural influences are integration policies in the residence country, the political situation in the origin country, and labour market discrimination. For example, perceiving discrimination in the workplace can bring about the feeling of not being accepted and increases the emotional distance towards both the workplace and country (Latcheva and Herzog-Punzenberger Citation2011). For drawing a comprehensive picture of national belonging, it is crucial to acknowledge one’s individual sense of belonging and the structural factors that condition these experiences separately from, yet in relation to, each other. We will do so accordingly.

Multidimensional embeddedness

Besides belonging being mixed, the experience of belonging is also likely to be multidimensional. Previous research has stressed that one can experience belonging on multiple levels and dimensions, as well as to many different objects of attachments (Yuval-Davis Citation2006), which is referred to as multidimensional embeddedness (Van Houte Citation2014; Davids and Van Houte Citation2008). The integration paradox literature has a national focus in assuming the country and/or its population is homogeneous or ‘a whole’. Moreover, national belonging can also be experienced through other dimensions such as being part of a family or one’s position at work (Eijberts, Ghorashi, and Rouvoet Citation2017). We will therefore acknowledge multiple dimensions in our study. A person’s educational level can be considered part of the economic dimension, examples of the other dimensions are ties with friends and family (social), political engagement and voting behaviour (political), and religious identification and practices as well as media use (cultural).

Interview strategy

Sampling

We draw from in-depth life history interviews with 32 highly-skilled recent Turkish migrants in the Netherlands who moved to the Netherlands around 2012/2013.Footnote 1 We invited respondents who stated to be interested in follow-up research in the New Immigrants Survey (NIS2NL) survey data. All 32 migrants had high educational levels, meaning that most informants finished university education. Purposefully sampling from NIS2NL (Lubbers et al. Citation2018) allowed for interviewing those who, according to the survey, are highly-educated but feel little belonging to the Netherlands (N = 15) and those who are highly-educated but do experience belonging in the Netherlands (N = 17). The first author conducted the interviews between July and October 2018 with this study’s research question being central, and over the course of the 32 interviews, we reached the point of saturation as no new themes or concepts emerged.

We invited 75 people as part of the paradox sample and 62 who did not show a paradox in NIS2NL. A sense of belonging was measured in line with the paradox literature (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2019; Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013), asking about their attitude towards native Dutch (0 – most negative, to 10 – most positive), the importance of the Netherlands for their sense of who they are (1 – very important, to 4 – not important at all) and having a strong sense of belonging to the Netherlands (1 – totally agree, to 5 – totally disagree). Scores of respectively 5 or lower, 3 or 4, and 4 or 5 are seen as indicators of having a low sense of belonging. When one has a low sense of belonging on at least two of the three items, we have labelled them as part of the integration paradox sample. Scores of respectively 7 or higher, 1 or 2, and 1 or 2 are seen as indicators of a high sense of belonging in the Netherlands. When one scored this way on at least two of the three items, we concluded that this person experienced no paradox. Within these boundaries, we managed to include a diverse group of informants in terms of age and sex, as presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive information of recent Turkish migrants interviewed.

Interviews and interviewer

The invitations were sent by mail in Dutch, English and Turkish so that those who were interested could reply in the language they felt comfortable with. More than half of the in-depth life history interviews were being held in English, nine were held in Dutch, and five were held in Turkish (Seale et al. Citation2004). The interviews held in Turkish were assisted by a professional Turkish interpreter. The interpreter was a recent migrant from a large city. This resulted in a mutual understanding and pleasant atmosphere during the interviews, where the informant felt the interpreter knew what one was talking about. Interviews lasted one to three hours and were conducted at a location of informants’ preference. Often this was their home, in a few cases this was in a public place. If preferred by the informant, one’s partner was present during the interview. This was the case for six interviews. Comparing interviews of those without a partner present to those with a partner present and comparing the interviews conducted in different languages did not lead to different results or interpretations; the general processes discussed were similar.

Taking a biographical, narrative approach during the interviews allows us to understand informants’ dynamic and multi-layered perspectives (Eijberts, Ghorashi, and Rouvoet Citation2017). Using this approach also enables gaining insight in the meanings that are attached to the main themes of this study (e.g. belonging, education). Various phases in life were discussed including life before migration, the first years after migration, the present and the future. Topics that were addressed ranged from several aspects of belonging to other domains of integration, individual characteristics, and life events.

The first author and interviewer is part of the Dutch majority population (which was revealed due to way of name and appearance). Informants were therefore very willing to explain and elaborate on answers since they could not rely on the interviewer knowing ‘what things are like’, something previously addressed in cross-cultural interviewing (Simonsen Citation2018). Moreover, it is supposed that the author’s age (24 at the time of interviews) helped signal that she was not a distanced authority. We expect that, as the informants were contacted via the New Immigrants Survey, one trusted the interviewer and the university and thus this research initiative.

Analytical strategy

Interviews were transcribed and analysed using the software program MAXQDA. Narrative and textual analyses were used to discover patterns among both groups of migrants, those with and those without a paradox. These two groups were analysed separately to study how the same topic or theme, for example one’s social life, was experienced differently. In the first round of coding, we coded inductively and in vivo to use informants’ own expressions to capture the content. Then, we more specifically compared both groups in their experiences and construction of national belonging.

We analysed the narratives using the multiple tools drawn from the belonging literature, acknowledging both migrants’ dialogical construction of belonging and the performative aspect of it (as recommended by Yuval-Davis Citation2011; Van Houte and Davids Citation2008), and relating this to mixed and multidimensional embeddedness. Below we describe an analysis of an example that came forward in our interviews in which we explicate possible dialogical and performative forms of belonging, the interplay between structure and agency as well as the multidimensionality to illustrate how we use insights from the belonging literature as tools to analyse individuals’ narrative.

We found that recent migrants are limited in the way they can make friends with either Dutch Turks or Dutch natives (social). Both the Dutch Turks and the native population have certain expectations of and judgements about who the recent migrants should be (dialogical), for example with respect to cultural traditions. The mismatch between these expectations and the realities cause friction and disappointment. Consequently, feelings of in-betweenness hamper a sense of belonging, especially when one makes investments and would like to develop and susain social ties in the new country (performative).

So, putting yourself out there (agency, performative) to establish connections and consequently experiencing that others view you differently than you see yourself (structure, dialogical) causes struggles with a sense of belonging. Being highly-educated (economic) relates to this as this can strengthen the experienced disappointment, due to made investments in education and the associated feeling of being ‘different’ from more traditional Turks in the Netherlands. Experiencing exclusion from both groups results in feeling misplaced and thus little belonging in the Netherlands, despite or fostered by socio-economic success.

Addressing how various dimensions (economic, social) matter for one’s sense of (dialogical, performative) belonging as well as how one’s agency (participating and putting yourself out there, performative) and structure (social exclusion from multiple sides) interrelate helps to understand how a so-called paradox can come about. Whilst this line of reasoning with respect to experiencing exclusion fits previous paradox studies (Verkuyten Citation2016), it shows that the seemingly independent role of one’s education for belonging is instead influenced and conditioned by a range of factors, such as exclusion from multiple sides, that are necessary to acknowledge to grasp the full picture. These frameworks derived from the belonging literature help in doing so and will be the point of departure for our analysis.

The results below are interpreted according to the example above, and illustrated by quotes, which are identified with an ‘I’ followed by the number that can be found in .

Results are presented based on patterns distinguished in a substantive part of the sample.

Results

In our results we distinguish two strands. The first refers to the way belonging is understood, which informs us about the conceptual and methodological interpretation of national belonging and how this is captured in previous paradox studies. The second strand discusses conditions that constrained the construction of belonging among those with a paradox, which came forward when comparing individuals with a paradox to those without.

Understanding belonging (1): belonging everywhere or nowhere

Informants shared that one’s identity often surpasses national boundaries. Indeed, a large share of informants talked about feeling more like a world or European citizen. Crucially, we can distinguish two types of such ‘supranational’ citizens among our informants. Some suggest they can belong anywhere whilst other experience no belonging to any specific place or country – so not to the Netherlands either:

I adapt anywhere I go, but I don’t feel like I belong to anywhere. (paradox sample – I6)

I would label myself as a world citizen. I think the Netherlands is, is somewhere that’s suitable for world citizens. (…) I thus feel more and more, I would say that I feel, I feel at home. (paradox sample – I2)

Understanding belonging (2): belonging as being meaningful

Another dimension that is mentioned throughout when discussing national belonging is being able to contribute to one’s environment. Belonging thus not only has a dialogical, relational aspect regarding people or places but also a performative aspect where contributing to society is necessary to belong somewhere and is kept in mind when migrants answer survey questions on belonging. This belonging, can be developed through work (economic, performative) or establishing a social network (social, performative):

After getting work, it all improved. I could meet new people and like, okay now I have friends here and my own family. So, I felt more and more at home. Because when you are at home alone, you are nothing. (non-paradox sample – I16)

Moreover, the interviews illustrate that it is not only economic integration that can enable belonging, but that also one’s social and family life can do so. Agency to contribute to a society and be meaningful, whether it is through being economically active or building a social network, was experienced as key in constructing belonging to a new place.

Home is where I can have a say, where I’m able to pull some wires. (paradox sample – I9)

I can’t celebrate my own holiday, because I’m a Muslim, I can’t celebrate it here. It doesn’t feel the same. (…) I see that my [native Dutch] wife has everything. She has everything in control, and I have nothing here. (paradox sample – I3)

Conditions of the paradox

The results above made clear that a found paradox among higher-educated migrants is based on a focus of belonging that not necessary aligns with migrants’ experiences (and their way of responding to survey items). Below, it becomes clear that individuals with a paradox experience various constraints in constructing belonging, whereas those without a paradox do not or to a lesser extent. Below, we will discuss conditions that our interview data suggests to strengthen or hamper the likelihood of being highly-skilled and (paradoxically) experiencing little national belonging.

Conditions of the paradox (1): expectations about the Netherlands

A first condition we distil from the interviews is having expectations of life in the Netherlands before migration and experiencing misalignment of these expectations in reality (structure). These expectations are rooted in two related aspects: (a) one’s experienced European lifestyle and liberal mind-set developed in Turkey and (b) one’s migration motive.

With respect to the former, a great number of our interviewees grew up in large, Europe-oriented cities such as Izmir, Istanbul and Ankara. Being fully adapted to a so-called secular lifestyle where one experienced freedom, led to high expectations of life in the Netherlands, both with respect to its open-minded and tolerant attitude (cultural) as well as economic opportunities (economic). When reality falls short on these expectations, this causes insecurity about one’s decision to migrate and about one’s life in the Netherlands in general. One woman discussed how she, against her expectations, was excluded by Dutch students at university (social) and how it affected her:

It makes you feel bad of course, you know, like – because my expectations on Dutch people were really high. I set the bar high because I was like okay. You know, it’s a free country? Why not? But apparently, it’s not that easy. (paradox sample – I7)

Among highly educated people in Turkey, European people have really high prestige. So, it was also what I expected to find … I was living in Turkey like a European woman (…) in here, I feel Turk. (paradox sample – I9)

Yeah, I didn’t know that I had a status in Turkey but after coming here I feel like yes, I had a status and I miss it sometimes (…) In Turkey there is an idiom ‘a stone is heavy in its own place’, so I mean Istanbul University has a name in Turkey but not here. (paradox sample – I1)

Another important driver of these expectations – the second aspect mentioned opening this section – is one’s migration motive. For example, especially those who moved for educational or economic reasons are disappointed when these efforts are not valued. Those who moved due to political reasons (political), had particularly high expectations with respect to the tolerance and open-mindedness of the Netherlands, which were not fulfilled in many cases. As one argued:

I didn’t expect to experience this kind of allergy towards foreigners, as the Netherlands is supposed to be this modern and developed country. (paradox sample – I8)

About the Netherlands I did not have any idea at all (…) I was not having really like a bad or good feeling about Dutch people. It was really neutral when I arrived here. And in the meantime, it did not turn out really like in a negative way. (non-paradox sample – I19)

Conditions of the paradox (2): experiencing exclusion in the Netherlands

As discussed above, part of experiencing less belonging is having expectations that do not meet reality. In this paragraph we will explore further how this reality in the Dutch context (structure) shapes migrants’ experiences, as many informants in the paradox group mention they feel excluded in the Netherlands. Exclusion can take up many forms, ranging from experiencing relative deprivation at work (economic) to facing stereotypes based on their ethnicity among Dutch people (cultural). Some feel that their skills and experiences are not valued, and many feel excluded based on being a foreigner more broadly. In each case the interviewee did not feel like they had the agency to oppose or change this situation for the better:

I am an educated person, I had university education. But then you see that neither your diploma nor your experience in your country are accepted here. They don’t accept. And they don’t take you in general seriously. (…) I understand that whomever you are, whatever you do, it doesn’t matter you cannot gain prestige, you cannot gain respect. (paradox sample – I16)

So, I don’t get in touch with them (…) if they find you not Turkish or Muslim enough then you will be criticized severely. (paradox sample – I5)

According to my relatives here I’m not that Turkish, but for Dutch people I’m too Turkish. (paradox sample – I7)

Those who do not experience a paradox seem unbothered by or have been spared such exclusionary experiences, allowing for a sense of belonging being constructed through getting a job or developing social ties. When talking about discrimination towards Turks in the Netherlands this man said:

Like some people say (…) we are discriminated, but I don’t think so. I can sit here, everyone can go and do their own events, like Turkish events, they go to mosques and do stuff. (…) As a foreign national, I was able to buy a house here without any problem. (non-paradox sample – I23)

Conditions of the paradox (3): having hard feelings for the home country

One’s country of origin, Turkey, is another location in which migrants are embedded that matters greatly in how one shapes one’s life here (structure). Many informants mentioned that the changing political and economic landscape of Turkey contributed to their move abroad. Their sense of belonging is already politicised in Turkey, as they did not feel comfortable staying in their home country. The situation in Turkey (economic and political) affects one’s investments and experiences in the Netherlands, as many argue they do not want to move back:

Nowadays I don’t see a future in Turkey, not for my own child and not for me before I got a child I would not have seen a future for me there either. (…) Eh, we don’t have elections for five years so for the coming five years, I don’t see a future there. (non-paradox sample – I28)

I tend to see negative things in Turkey more and compare it with the Netherlands and I always say I’m grateful to live here now, because it’s hard (…) because of the ruling party in Turkey, the economic situation is going worse and they can’t do anything for it. (non-paradox sample – I23)

I feel so responsible to Atatürk and his generation eh, because they did their best to leave us a good secular and yeah country with human rights and now I’m just doing nothing except for voting. (paradox sample – I1)

Conclusion & discussion

This article aimed to explore why highly-skilled migrants feel less belonging to the residence society – as was previously found in survey-based studies (Ten Teije, Coenders, and Verkuyten Citation2013; Tolsma, Lubbers, and Gijsberts Citation2012). By purposeful sampling higher-educated migrants from the New Immigrants Survey we were able to compare those with a paradox to those without a paradox and analyse their individual narratives in terms of what shapes low levels of national belonging and provide a next step in understanding the integration paradox. Theoretically, we linked the (mainly quantitative) integration paradox literature to the more conceptual studies on belonging. Based on the latter, we applied a combiniation of frameworks to explore the complex relation between being higher-educated and national belonging. As such, these frameworks offered new ways to look at results from the integration paradox literature and contributed to explaining it.

We conclude that among higher-educated migrants, a sense of national belonging is created depending on various experienced conditions. Whilst the logic underlying the paradox literature sometimes holds (i.e, scoring low on national belonging due to certain expectations about one’s economic situation or experiencing social exclusion) our results show this is only part of the story. The other part of the story, of which we unfolded major elements in this study, is necessary to grasp why a paradox exists, and why it exists among some groups and not among others. Future studies on the paradox are thus recommended to interact the influence of education with such conditions that were not (fully) captured in previous survey studies, as this seems core to understand the linkage between education and national belonging.

More concretely, we presented five core findings that help to understand the presence of a paradox, which can be categorised into two strands (as presented in ). The first strand is related to the meaning of the concept of belonging and how it can be captured in research (methodological-wise). The second strand focuses on conditions and mechanisms that make clear why for some migrants higher education does contribute or link to belonging in the Netherlands and for others it does not. Below, we relate each finding to previous studies and offer pathways for future research.

Understanding belonging

First, a large number of our interviewees identified as a supranational citizen (i.e. world or European citizen), rather than as Dutch and/or Turkish only, among which two groups can be distinguished. One group feels belonging everywhere (in whatever country), the other nowhere (and thus only supranational). Considering that both types of world citizens exist, makes us realise many informants are classified as being paradoxical due to experiencing relatively little belonging to the Netherlands but actually experience little particular belonging anywhere. Consequently, survey studies on the paradox have, unknowingly, included supranational citizens (who are mainly highly-educated) among the low belonging groups, whereas this is not the lack of belonging they conceptually set out the measure. Future studies could study how such supranational and national belonging relate and to what extent this offers a systematic explanation for the paradox, for example by adding items on world citizenship in analyses.

The first group of world citizens who experiences belonging that transcends national borders echoes prior studies on transnational belonging and the role of ‘place-belongingness’ (Ehrkamp Citation2005; Huizinga and van Hoven Citation2018; Antonsich Citation2010), but a closer look mainly raises import new questions. For example, Ehrkamp (Citation2005) stresses that experiencing comfort and security in a place is needed to feel belonging. Although we found that world citizens say to belong everywhere, a key role for place could remain: they also indicate that places vary in how inclusive they are for such ‘wordly’ mindsets. In other words, place-belongingness seems layered, with a rather fundamental and a more practical level of belonging; future research could delve into this more. Similarly, the second type of world citizen we found is rarely addressed, and sheds light on existing debates. The migrant who experiences belonging nowhere, does not necessarily feel marginalised. We found that migrants feel a kind of comfort and even empowerment in not belonging to something, which deserves more attention (Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2016).

Second, we found that belonging someplace new is defined by having a feeling of purpose and meaning in (daily) life. The inability to do so leads to frustration and disappointment. Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings (Citation2019) argued that a paradox may be brought about due to a mismatch between one’s educational investments and one’s job and/or occupational status. They did not find support for this hypothesis. With insights from current paper, we suggest that it is indeed not (necessarily) about having a certain job or status, but rather about whether one feels one matters and can be a valuable, contributing member to the Dutch society. This performative dimension of belonging has not been captured in previous paradox studies where items focus either on one’s attitude to the native population or the country. In the experience of migrants however, their sense of national belonging entails possibilities to contribute, having a say and acquire meaning in life in doing so (Eijberts, Ghorashi, and Rouvoet Citation2017). Lacking possibilities to perform belonging thus seem to hamper possibilities to belong emotionally, stressing the importance of considering both dialogical and performative belonging. Concretely, the integration paradox might thus be less paradoxical if the performative dimension is included in the concept of belonging and if the different potential dimensions of feeling a contributive member of society are included in future surveys.

Both core findings illustrate that an emphasis on belonging as identification towards a nation overlooks a broader experience among Turkish migrants who identify with either the world or Europe and moreover have the need to create meaning within a nation. Consequently, we argue for rethinking the concept-measurement connection in that literature and for incorporating the performative aspect in surveys as well as the possibility of supranational identification.

Conditions of the paradox

In terms of explanatory factors, we found several conditions that can bring about or hamper a negative impact of being highly-skilled on national belonging, of which we stressed three.

First, having high expectations which do not meet reality seem to result in a low sense of belonging. Lacking the agency to fulfil economic aspirations or counter social exclusion in a country expected to be tolerant brings about feelings of disappointment. When one has no or low expectations about one’s career or how one will be treated, there is less space for reality falling short. Supposedly, such expectations are in particular present among the highly-educated (see Verkuyten Citation2016). We further specify this condition by stressing that expectations concern not just the economic or cultural domain, but also include the political and social domain. We could partly draw this out as we focussed on recent migrants, who also moved for other than economic and associated motives. Future studies could delve deeper into these expectations about the residence country across domains.

Second, we found that some highly-educated migrants experience exclusion from the Dutch native population and the Turkish community in the Netherlands. This in-betweenness increased non-belonging through disappointment and feelings of loneliness (see also Ni Laoire Citation2008). This indicates that the paradox literature was right in theorising the importance of feeling accepted in the new country, but overlooked that some migrants experience little identification with the Turkish community, which clarifies why perceived group acceptance or discrimination does little in explaining the negative impact of educational level as found before (Geurts, Lubbers, and Spierings Citation2019). This exclusion from Turkish communities in the residence societies should be included in future survey studies. Moreover, we recommend to acknowledge more subtle measurements of social exclusion, as informants shared such exclusion was also experienced due to Dutch people not finding time to meet up, for example. In addition, the paradox literature’s mono-dimensional focus towards the country or population as wholes does not align with migrants’ varying experiences with belonging to specific groups. This result echoes Tolsma, Lubbers, and Gijsberts (Citation2012) focus on relative identification when studying the paradox, by asking whether one felt more Turkish or Dutch. We support the use of such a dialogical measurement, and would add that future studies could explore to what extent a paradox is present when sub-groups or places are acknowledged.

Finally, we found that a paradox is more likely if one still cares about one’s home country. More specifically, those engaged with Turkish politics and economic welfare have more trouble settling elsewhere. Having such feelings of guilt and worry make it difficult to invest in a new life elsewhere, as was found for leaving behind family by Baldassar (Citation2015). This condition may also be a reason for a paradox among second-generation Turkish migrants, as the higher-educated might stay more engaged in Turkish politics. Accordingly, future studies could use voting behaviour in the Turkish elections or watching Turkish television as possible indicators of such engagement and their conditioning role in the paradox.

Overall, these results underline the importance of a mixed and multidimensional approach to belonging, as it theoretically deepens the paradox literature. Our study explored specific conditions which are the cause for such seemingly paradoxical consequences of being highly-educated. A common denominator in these conditions is the importance of how belonging is politicised in different contexts they are embedded in, including the country of residence and origin; the ‘politics of belonging’, as argued by Antonsich (Citation2010) and Yuval-Davis (Citation2006). Regarding generalizability, it is likely that such conditions are also relevant to other migrants from other origin countries or migration generations. However, the shape of these conditions that may hamper a sense of belonging among highly-skilled migrants, requires translation to these settings. Similarly, future research could explore how similar processes in different countries of residence manifest themselves: to what extent does the national context matter in bringing?

Reflecting on this study’s approach and results, we set out to shed new light on the counterintuitive difference in national belonging previously found between higher- and lower-educated migrants. By comparing higher-educated migrants who did and did not experience the paradox, we provided an important stepping stone. To further understand this paradox, future research could study lower-educated migrants. Although previous research suggests that the conditions we distinguished are more likely to be experienced by higher-educated than lower-educated migrants (e.g. Verkuyten Citation2016), studying lower-educated migrants can unravel the integration paradox further.

Here, we showed that in times requiring migrants to become part of a national community, this is easier said than done for highly-skilled migrants. Several processes hamper establishing such a sense of national belonging, ranging from identification with a supranational entity to experiencing exclusion from various communities in the residence country. These various sources matter in how highly-educated migrants establish a sense of belonging to the Netherlands, illustrating that grasping the paradox requires acknowledging and exploring such mechanisms. This study has thereby discussed and explored the presuppositions and status quo of present integration paradox literature and offered opportunities for future studies to address these.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Turkish migrants in the NIS2NL survey on average indicated that the Netherlands is ‘fairly important’ for their identity, illustrating that after residing seven years a certain sense of belonging is present.

References

- Alba, Richard , and Victor Nee . 2009. “Rethinking Assimilation Theory for a New Era of Immigration.” International Migration Review 31 (4): 826–874. doi: 10.1177/019791839703100403

- Antonsich, Marco. 2010. “Searching for Belonging – An Analytical Framework.” Geography Compass 4 (6): 644–659. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2009.00317.x

- Baldassar, Loretta. 2015. “Guilty Feelings and the Guilt Trip: Emotions and Motivation in Migration and Transnational Caregiving.” Emotion, Space and Society 16: 81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.emospa.2014.09.003

- Crul, Maurice , and Hans Vermeulen . 2003. “The Second Generation in Europe.” International Migration Review 37 (4): 965–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2003.tb00166.x

- Davids, Tine , and Marieke Van Houte . 2008. “Remigration, Development and Mixed Embeddedness: An Agenda for Qualitative Research.” IJMS: International Journal on Multicultural Societies 10 (2): 169–193.

- De Bree, June , Tine Davids , and Hein De Haas . 2010. “Post-Return Experiences and Transnational Belonging of Return Migrants: a Dutch—Moroccan Case Study.” Global Networks 10 (4): 489–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2010.00299.x

- De Vroome, Thomas , Borja Martinovic , and Maykel Verkuyten . 2014. “The Integration Paradox: Level of Education and Immigrants’ Attitudes Towards Natives and the Host Society.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 20 (2): 166–175. doi: 10.1037/a0034946

- De Vroome, Thomas , Maykel Verkuyten , and Borja Martinovic . 2014. “Host National Identification of Immigrants in the Netherlands.” International Migration Review 48 (1): 76–102. doi: 10.1111/imre.12063

- Ehrkamp, Patricia. 2005. “Placing Identities: Transnational Practices and Local Attachments of Turkish Immigrants in Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (2): 345–364. doi: 10.1080/1369183042000339963

- Eijberts, Melanie , and Halleh Ghorashi . 2017. “Biographies and the Doubleness of Inclusion and Exclusion.” Social Identities 23 (2): 163–178. doi: 10.1080/13504630.2016.1244766

- Eijberts, M. , H. Ghorashi , and M. Rouvoet . 2017. “Identification Paradoxes and Multiple Belongings: The Narratives of Italian Migrants in the Netherlands.” Social Inclusion 5 (1): 105–116. doi: 10.17645/si.v5i1.779

- Elveren, A. Y. 2018. Brain Drain and Gender Inequality in Turkey . Cham, Switzerland : Palgrave Pivot.

- Geurts, Nella , Marcel Lubbers , and Niels Spierings . 2019. “Structural Position and Relative Deprivation among Recent Migrants: A Longitudinal Take on the Integration Paradox.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1828–1848. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1675499.

- Gordon, Milton Myron. 1964. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins . New York : Oxford University Press.

- Huizinga, Rik P. , and Bettina van Hoven . 2018. “Everyday Geographies of Belonging:Syrian Refugee Experiences in the Northern Netherlands.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 96: 309–317.

- Kloosterman, Robert C. 2010. “Matching Opportunities with Resources: A Framework for Analysing (Migrant) Entrepreneurship From a Mixed Embeddedness Perspective.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22 (1): 25–45. doi: 10.1080/08985620903220488

- Kristen, Cornelia , Peter Mühlau , and Diana Schacht . 2016. “Language Acquisition of Recently Arrived Immigrants in England, Germany, Ireland, and the Netherlands.” Ethnicities 16 (2): 180–212. doi: 10.1177/1468796815616157

- Lähdesmäki, Tuuli , Tuija Saresma , Kaisa Hiltunen , Saara Jäntti , Nina Sääskilahti , Antti Vallius , and Kaisa Ahvenjärvi . 2016. “Fluidity and Flexibility of ‘Belonging’: Uses of the Concept in Contemporary Research.” Acta Sociologica 59 (3): 233–247. doi: 10.1177/0001699316633099

- Lambert, Nathaniel M. , Tyler Stillman , Joshua Hicks , Shanmukh Kamble , Roy Baumeister , and Frank Fincham . 2013. “To Belong is to Matter: Sense of Belonging Enhances Meaning in Life.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 39 (11): 1418–1427. doi: 10.1177/0146167213499186

- Latcheva, Rossalina , and Barbara Herzog-Punzenberger . 2011. “Integration Trajectories: A Mixed Method Approach.” In A Life-Course Perspective on Migration and Integration , edited by Matthias Wingens , Michael Windzio , Helga de Valk , and Can Aybek , 121–142. Dordrecht : Springer.

- Lubbers, M. , M. Gijsberts , F. Fleischmann , and M. Maliepaard . 2018. The New Immigrant Survey – The Netherlands (NIS2NL). The codebook of a four wave panel study. NWO-Middengroot, file number 420-004.

- Ni Laoire, C. 2008. “Challenging Host-Newcomer Dualisms: Irish Return Migrants as Home-Comers or Newcomers?” Translocations:Migration and Social Change 4 (1): 35–50.

- OECD . 2016. Recruiting Immigrant Workers: The Netherlands 2016 . Paris : OECD Publishing.

- Reeskens, Tim , and Matthew Wright . 2014. “Host-country Patriotism among European Immigrants: A Comparative Study of its Individual and Societal Roots.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (14): 2493–2511. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2013.851397

- Seale, Clive , Giampietro Gobo , Jaber F. Gubrium , and David Silverman . 2004. Qualitative Research Practice . London : Sage.

- Simonsen, Kristina Bakkær. 2017. Do They Belong? Host National Boundary Drawing and Immigrants’ Identificational Integration . Aarhus : Forlaget Politica.

- Simonsen, Kristina Bakkær. 2018. “What It Means to (Not) Belong: A Case Study of How Boundary Perceptions Affect Second-Generation Immigrants’ Attachments to the Nation.” Sociological Forum 33 (1): 118–138. doi: 10.1111/socf.12402

- Statistics Netherlands . 2019. “Immi- en emigratie.” Accessed April 17, 2020. https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/nl/dataset/03742/table?dl=37142 .

- Steinmann, Jan-Philip. 2019. “The Paradox of Integration: Why Do Higher Educated New Immigrants Perceive More Discrimination in Germany?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (9): 1–24. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2018.1480359

- Ten Teije, I. , M. Coenders , and M. Verkuyten . 2013. “The Paradox of Integration.” Social Psychology 44 (4): 278–288. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000113

- Tolsma, Jochem , Marcel Lubbers , and Mérove Gijsberts . 2012. “Education and Cultural Integration among Ethnic Minorities and Natives in The Netherlands: A Test of the Integration Paradox.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (5): 793–813. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2012.667994

- Van Houte, Marieke. 2014. Moving Back or Moving Forward? Return Migration After Conflict . Maastricht : Boekenplan.

- Van Houte, Marieke , and Tine Davids . 2008. “Narrating Marriage: Negotiating Practices and Politics of Belonging of Afghan Return Migrants.” Identities 25 (6): 631–649. doi: 10.1080/1070289X.2017.1287489

- Verkuyten, M. 2016. “The Integration Paradox.” American Behavioral Scientist 60 (5-6): 583–596. doi: 10.1177/0002764216632838

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2006. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214. doi: 10.1080/00313220600769331

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2011. The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations . Los Angeles, CA : Sage.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira , Kalpana Kannabiran , and Ulrike Vieten . 2006. The Situated Politics of Belonging . London : Sage.