ABSTRACT

This paper examines the experiences of Nigerian and Eritrean migrants on their journeys from their origin country to prior to disembarkation across the Mediterranean Sea in Libya. This paper builds on the work of Vigh (2006. “Social Death and Violent Life Chances.” In Navigation Youth, Generating Adulthood: Social Becoming in and African Context, edited by Catrine Christiansen, Mats Utas, and Henrik Vigh. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet; 2009. “Motion Squared: A Second Look at the Concept of Social Navigation.” Anthropological Theory 9 (4): 419–438) in the social navigation approach by applying it to migration journeys and illustrating how migrants display their agency within their navigation, while simultaneously reflecting on the oppression and constrained choices that they experience in their journeys. Drawing on qualitative fieldwork with 69 respondents in Italy in 2017, this paper examines how Eritrean and Nigerian migrants experience their journeys and navigate through complex environments. The results illustrate the differences in expectations, experiences, and transnational connections of the two cases. This article contributes to the literature on migrant’s agency and social navigation of their journeys.

Introduction

Clandestine migration journeys and refugee journeys have recently become a paradigm of social research in themselves (Mainwaring and Brigden Citation2016; Benezer and Zetter Citation2015; Schapendonk, Bolay, and Dahinden Citation2021). Mainwaring and Brigden (Citation2016) argue that the journey itself can ‘be as complex and significant as other phases of migration’ and further that it may have important implications for other phases of the migration process (247). Without question, these journeys have become increasingly dangerous due to border controls and the development of a sophisticated migration industry of smuggling networks. It is important to understand the stages of these journeys as events occurring at different points can have significant impacts on the rest of the migrants’ life. Understanding how migrants exercise their agency and navigate their journeys through the migration industry is an important area of inquiry to develop a recognition of the needs of this group and second to conceptualise the implications for migration governance and policy (Mainwaring and Brigden Citation2016; Triandafyllidou Citation2017).

The objective of this paper is to examine the experiences of Nigerian and Eritrean migrants on their journeys from their origin country to prior to disembarkation across the sea in Libya through a social navigation framework, which enables an exploration of the agency and constraints migrants face in their journey (Triandafyllidou Citation2019; Schapendonk Citation2017). Research has demonstrated that one of the most difficult routes to Europe is through the Central Mediterranean (McMahon and Sigona Citation2018). The Central Mediterranean has been labelled the world’s most dangerous sea crossing with the International Organisation for Migration reporting 13,476 migrants’ deaths along this route from 2014 to 2017 (IOM Citation2016). These numbers are significantly higher than any other migration routes to Europe. Furthermore, the vast majority of disembarkations for Italy are from Libya. Recent research and media outlets have increasingly documented the atrocities committed against migrants in Libya (see Snel, Bilgili, and Staring Citation2021; Kuschminder and Triandafyllidou Citation2020), stressing further the dangers and extreme hardships migrants experience on this route. The crisis in Libya has led recently to increased attention on the human rights abuses occurring in Libya, but it is essential to note that these abuses spread beyond Libya to Niger, Sudan, Egypt and Ethiopia, among other countries.

The two groups selected for analysis in this study, Eritreans and Nigerians represent the two highest origin country arrivals in 2015 and 2016 to Italy, but differ in many respects including: country context, migration drivers, routes to Libya, and experiences in Libya. Eritrea is considered a ‘refugee producing country’ and has an average first instance asylum acceptance rate of over 75 percent across the EU. Nigerians, on the other hand, have low asylum acceptance rates in the EU. A common policy assumption is that migrants coming across the Central Mediterranean are ‘economic migrants’ and that their intended destination has always been Europe (McMahon and Sigona Citation2018). This is perpetuated by claims that most migrants crossing the Central Mediterranean are in search of a better life and not necessarily in need of international protection. In this paper, the focus is on experiences before disembarkation and I use the term migrants recognising that individuals from either country may or may not be a refugee.

This paper is based on qualitative interviews conducted with Eritreans and Nigerians in Italy. A total of 69 interviews were conducted in Sicily, Rome and Milan in 2017. Following from this special issue (see Introduction) this paper will examine Eritrean and Nigerian migrants’ journeys from their country of origin to their disembarkation on boats in Libya for their journey across the Mediterranean to Italy. This larger stage of the journey, within their overall migration trajectory, can be divided into further distinct stages: leaving the country of origin, the journey in-between leaving and Libya, and surviving and escaping Libya.

The next section presents the theoretical framework of this paper of the social navigation of migration journeys. This is followed by an introduction to the case study of Eritrean and Nigerian migrants and then the study methodology. The results are presented in three sections of leaving, in between leaving and Libya, and surviving and escaping Libya. The paper concludes with a discussion.

Social navigation

The frame of social navigation provides an analytical framework to examine the intersection of agency, social forces, and change (Vigh Citation2009). Social navigation describes how people move in uncertain environments through contexts of insecurity, conflict and rapid change (Vigh Citation2006, Citation2009). The focus is on what Vigh (Citation2009) terms the ‘third dimension’, meaning that research normally looks at either the way social formations change over time, or the ways agents themselves move through social formations. This third dimension is the interactivity between the two, focusing on how agents move through a moving environment (Vigh Citation2009, 420).

Social navigation focuses on the individuals’ agency and represents the ability of an individual or migrant to plot their trajectories and adjust their trajectories in reaction to a changing environment (Denov and Bryan Citation2012). The concept of social navigation thus provides a strong analytical frame for understanding how migrants navigate their journeys and trajectories to Europe through the migration industry and conflict environments. It takes a step further from a focus on decision-making factors to encompass the social environment and reactions to a rapidly changing context (Schapendonk Citation2017). Triandafyllidou (Citation2019) argues that social navigation is useful for considering different ‘nodal points’ within the journey wherein migrants may be able to facilitate resources to move, or may experience structural constraints that limit movement.

Finally, the concept of social navigation is well suited to the migration journey as it seeks to account for a dense temporality, recognising that movement at the moment is related to both the ‘socially immediate and the socially imagined’ (Vigh Citation2009, 425). That is, the theoretical frame recognises that decisions made at the moment for mobility are rooted within an imagined future. For migrants coming to Europe, this is critically important as individuals are willing to take risks now in order to achieve the future imaginary of a life in Europe.

The recognition and focus on migrants’ social navigation of their journeys through the migration industry contrasts earlier perspectives of migrants, and in particular asylum-seekers, coming to Europe as passive victims or unaware subjects at the whim of smugglers (Havinga and Böcker Citation1999). Migration trajectories have greatly changed over the past two decades and current research provides evidence that migrants are increasingly active in information gathering regarding their journeys and trajectories (McAuliffe Citation2016). As an example, Dekker et al. (Citation2018) have used the term ‘smart refugees’ to describe Syrian migrants’ access and use of smartphones and social media in their migration journeys. Yet, these new terms suggest assurances that in reality migrants do not have in their journeys. Migrants face complex social environments that are dangerous and regardless of the use of smart phone technology, information prior to embarkation, social networks, or other preparations, they may still experience exploitation and abuse.

The forces of oppression, violence, geopolitics, legality, and border regimes are pressing down on irregular migrants within their journeys, but they choose to react, respond, and negotiate their livelihoods in reaction. Their choices in these environments are without any doubt heavily constrained. Research has shown how migrants navigate this oppression and complexity within their journeys (Schapendonk Citation2018; Triandafyllidou Citation2019; Schapendonk et al. Citation2018) and this articles contributes to this emerging literature.

Drawing from the social navigation frame there are three elements that I draw on as essential to the conceptualisation of how migrants navigate their journeys. First, as described by Vigh, the future is based on an unknown imaginary. Migrants are working towards a future goal of safety and security in an intended destination and the opportunity for a new life. This destination may or may not be known, with some migrants having a strong intended destination in their mind and for others this may be quite gray. The future imaginary, however, is a central part of the journey migrants navigation as the journey in itself has an intended end-point in the mind of the migrant. This relates to hope and optimism for a better future and life.

Second, social navigation is about the information awareness gathering and processing and using this information to make choices regarding the journey. This stresses the importance of social networks and highlights the role of transnational networks as a vital component of information access. Information can be gathered by multiple sources or by chance (Gladkova and Mazzucato Citation2017) and migrants work to process this information to make decisions regarding their trajectories. Information is used to calculate and determine risk and strategies are put in place to alleviate risks.

Third, migrants are flexible and reactive to rapidly changing situations in order to survive. As they transverse difficult environments and experience multiple forms of oppression, their choices can be constrained. Making quick decisions can enable mobility and survival (see Schapendonk Citation2017 for examples).

Social navigation is not just about navigating borders, the entry and exit, it is about navigating the social environment of irregularity within and between borders – it is about the risks faced in irregularity, the calculation of the information, and the decision making for a trajectory at a certain moment in time, and a focus on action or inaction for survival. Migrants are therefore active in plotting and planning, and sometimes it is quick action taking opportunities that arise by chance.

Case selection: Eritrean and Nigerian migrants

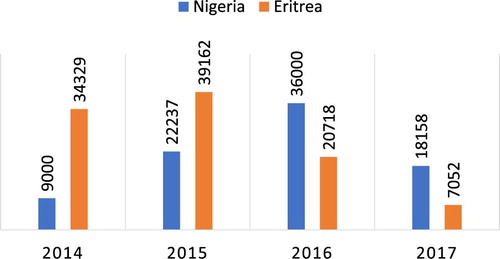

Both Eritrea and Nigeria have been top countries of origin of new arrivals on the Central Mediterranean route to Italy, particularly in 2015 and 2016 (see ).

Figure 1. Arrivals to Italy from Eritrea and Nigeria, 2014–2017. Source of data: IOM (Citation2016).

Eritrea is a small country of only 5.2 million people, compared to Nigeria that has the highest population in Africa at an estimated 195 million people. When considering flows across the Central Mediterranean these are quite different when considered as relative to the country’s population size. Since 2000, Eritreans have been fleeing their home country seeking to escape a repressive military regime. The main reasons cited by Eritreans for leaving include: to escape forced military conscription, endemic poverty, a lack of opportunities, and a lack of political freedom (Horwood and Hooper Citation2016). When exiting Eritrea, migrants arrive first in either Ethiopia or Sudan. Ethiopia has three longstanding refugee camps hosting Eritrean nationals and many Eritrean refugees also live irregularly in Ethiopia’s urban environments (Mallett and Hagen-Zanker Citation2018). Poor livelihood opportunities, a lack of autonomy and access to employment opportunities are key reasons that Eritreans seek to move onwards from Ethiopia (Mallett and Hagen-Zanker Citation2018). Formerly Israel was a target destination for Eritreans, but both difficult conditions in Israel and increased kidnapping on the Sinai route through Egypt have stemmed this flow.

Nigeria is a far more diverse country than Eritrean with varying levels of economic wellbeing and high ethnic diversity in different regions. Edo state, located in the South of Nigeria, has been an active hub of human trafficking of primarily women to Italy since around the 1990s. This migration activity has also likely contributed to the irregular migration of primarily men (but also some women) from this region of Nigeria to Europe. The drivers must be viewed much more broadly and Edo state has high poverty, unemployment, and lower education levels. In the north of Nigeria, the violent extremism from Boko Haram has led to the displacement of 1.7 million people in Nigeria and 229,000 Nigerian refugees in neighboring countries (IDMC Citation2018). The drivers therefore of migration from Nigeria are diverse and differ depending on the individual’s region and place of origin.

Nigeria and Eritrea create strong contrasting cases for analysis in this study for three primary reasons. First, the routes of their journeys to and through Libya to disembarkation are different (as will be discussed in the results). Second, Eritreans are generally considered as a ‘refugee’ group, whereas Nigerians are considered as ‘economic migrants’. In this paper, no claims are made regarding status, but the analysis seeks to highlight the plight individuals face on their journeys from both countries. Finally, it is often assumed for both groups that Europe is the ‘destination’. By examining the journeys, decisions at different points, and the complex cases it will be demonstrated that the ‘destination’ is not so simple.

Methodology

This paper compares the cases of Eritrean and Nigerian migrants that have arrived in Italy between 2016 and 2017, reflecting the two largest country of origin groups arriving in Italy in 2016. The paper draws from 69 interviews conducted with 34 Eritreans and 35 Nigerians between January and June 2017. shows a breakdown of the number of interviews conducted per location.

Table 1. Interviews overview.

In each field site, the sampling strategy varied slightly depending on the local context. In Sicily, two Nigerian research assistants were recruited based on recommendations from local contacts, one located in Palermo and one in Siracusa. The research assistants recruited Nigerians that had arrived within the last year for an interview. This recruitment was both through their personal networks and by approaching people they did not previously know in reception centers or on the street at common meeting points. From the initial entry points, snowball sampling was also used to recruit further participants. Despite several attempts to find a Tigrinya translator in Sicily, this eventually was not possible. An Eritrean research assistant was recruited in Rome that arranged interviews with respondents via assistance from an NGO.

In Milan, permission was received from the City to conduct the interviews. The Commune di Milano (city of Milan) has a different structure than other parts of Italy wherein the commune has its own migration and refugee team that is separate from the Prefettura and National level administration. The commune therefore manages reception of asylum seekers arriving in Milan outside of the national dispersal programme. The commune provided permission and support for this research and coordinated an introduction to two NGOs: Fondazione L’Albero della Vita and Fondazione Progetto Arca onlus, that are contracted by the commune to provide reception assistance. Both NGOs provided support to the project by inviting the interviewer to their centres and informing their beneficiaries of the interviews. Separate to this, an independent Tigrinya translator was hired for translation during the interviews. Finally, during the fieldwork in Milan, policies and practices were changing within the city, and some Eritreans were also approached on the street for interviews.

All interviews began with a detailed verbal informed consent process. The interview methodology used a life cycle approach, beginning with leaving the country of origin, experiences in countries of first reception, decision making processes, coming to Italy, initial arrival, current situation, and future plans. The interviews generally lasted from 30 to 60 minutes. All interviews were transcribed and coded for analysis. The coding was conducted based on an issue-focused analysis and in two stages using both inductive and deductive coding techniques.

As a result of the multiple recruitment and sampling strategies the overall sample is fairly diverse. Almost all respondents were living in a reception centre at the time of interview, with only a small handful of Nigerians living outside of reception centres in Sicily and a few Eritreans in Milan. Of the respondents, 16 Eritreans and 6 Nigerians were female. The average age of both the Eritrean and Nigerian respondents was 25 years old. Except for two Nigerian respondents, none of the respondents had any higher education, with most not having completed secondary school. Fourteen of the Nigerian respondents were from Edo state, and the remaining respondents were from different regions including Northern Nigeria. Most Eritrean respondents were from the regions of Gash Barka and Debub, with only a small number of respondents originating from Asmara. All respondents had arrived in Italy between 2015 and 2017.

Navigating the route to Europe from Eritrea and Nigeria

The results are presented in the following three sections: (1) leaving the country of origin; (2) the journey in-between leaving and Libya; and (3) surviving and escaping Libya. These three sections reflect the different stages of the journey that migrants face before entering boats to cross the sea to Italy. As will be discussed, each stage is characterised by different social environments and challenges that need to be navigated.

Leaving

Eritreans and Nigerians had different experiences in leaving their countries as departure from Eritrea is forbidden without a visa, whereas Nigerians have the right to pass freely to Niger via the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) agreement. As a result, Eritreans must plan and execute their departure with more caution and strategy.

An estimated 5,000 Eritreans flee the country every month. The reasons for Eritreans fleeing is well documented including escaping forced conscription, arbitrary imprisonment and abuse, and a general lack of freedom (Rosberg and Tronvoll Citation2017). These reasons were cited by respondents in this study. Despite the large outward flows from Eritrea, leaving the country is a dangerous endeavor due to both a ‘shoot on site policy’ enforced by the military against people attempting to cross the border and the risk of imprisonment if caught (ODI Citation2017). Individuals leaving Eritrea are aware of these challenges, some having directly experienced these difficulties themselves. One respondent, Selam, tried to leave Eritrea to join her husband who left before her to Sudan. She was captured and imprisoned in Eritrea for trying to leave. Her family paid a fine of 25,000 Nakfa (approximately USD 1600) for her to be released from prison. Selam waited another three years in Eritrea before trying to leave again, and the second time was able to successfully join her husband in Sudan. Other respondents reported being caught up to three times on their way to Sudan and imprisoned by border guards.

In an effort to evade the authorities most Eritreans leave in secrecy in the night by foot to cross to Ethiopia or Sudan. The choice of Ethiopia or Sudan, depends largely on where in Eritrea they lived and which country border was closer and easier to cross. Most do not tell their families as they do not want them to worry, nor to be exposed if questioned by the police. Instead, they try to call their families once they have arrived in Ethiopia or Sudan to let them know they have left the country.

Leaving Eritrea thus requires a significant level of social navigation to evade police, understand routes, and plan in secrecy with trusted sources on where and how to go. One respondent, Feker described how he navigated his wife and his departure during his imprisonment. After completing his isolation imprisonment sentence for evading military service he was sentenced to manual work. During his manual work he was able to call his wife and he instructed her to leave to Ethiopia and go through Ethiopia to enter Khartoum. He also instructed her to send him money. He then escaped at nighttime and used the money she sent to pay the border guards to enter Sudan directly. Feker’s story shows how he has navigated his escape by evading the military, escaping the labour camp, and trusting that he can pay the border guards for entry into Sudan. He has also arranged a separate strategy for this wife so that they can be reunited in Sudan. The process of leaving Eritrea is thus a difficult journey requiring advanced planning and preparation.

For Nigerians, the process of leaving Nigeria is less difficult and less dangerous. Nigerians left for multiple different reasons. Some were fleeing Boko Haram, others were fleeing a specific familial or individual circumstance, and other respondents were looking for a better life. When leaving Nigeria some of the respondents prepared for their migration by working and saving funds to pay for the migration, while others left spontaneously in the night. Most respondents reported making their decision to leave on their own, however, for some leaving was not their decision. For example, one younger male respondent reported that he was told by a guardian to go with the person that took him to Libya, where he was told he was supposed to live with his Uncle. He did not really believe this person was his uncle, but felt he had no other choice so went to Libya.

From their community in Nigeria most respondents travelled by bus to Kano and through northern Nigeria to Niger. As mentioned above, through the ECOWAS agreement, Nigerians can travel regularly to Niger. Once in Agadez, Niger, smugglers are most often recruited and paid for the travel to Libya. Some respondents hired smugglers directly in Nigeria to take them to Libya. This route reflects the same findings from other studies with Nigerian respondents (IOM Citation2016).

Overall, leaving Nigeria was a relatively straightforward process, wherein Nigerians are free to leave their country and cross the border to Niger. Respondents did not discuss difficulties in leaving Boko Haram territory, however it was clear that fear motivated their movements and decisions were made quickly. Although the journey leaving Nigeria was not necessarily dangerous, it was still an emotional journey. It was reflected by respondents that the decision to leave was difficult and they felt pain and conflicting emotions at leaving.

The journey in between leaving and Libya

The physical journey begins with leaving the country of origin; however the next country of the journey is often not one of safety and security. For both Eritreans and Nigerians, the journey to Libya can be dangerous and complex, however, the findings indicate that this stage is more difficult and lengthier for Eritreans than Nigerians. One of the reasons for this, as will be discussed in the next section, is due to the different perceptions of Libya between the two country of origin groups that are held prior to their arrival in Libya.

Although Eritreans have been fleeing to nearby Ethiopia and Sudan for several years, the conditions for them in these countries are becoming increasingly difficult. There are roughly 155,000 Eritreans currently residing in Ethiopia. Last year the UNHCR estimated that it would make 6,486 applications for resettlement from a total refugee population of 783,401 (ODI Citation2017), which is less than one percent. Many Eritreans in Ethiopia still hope for resettlement. One respondent waited for three years in Ethiopia for the resettlement process but realised that nothing was going to happen and decided to move onwards. Another stated:

It was good before when migrants used to fill forms to go to Canada even though few get the chance and other Ethiopians fill the forms as Eritreans and go. But now that kind of process doesn’t exist anymore so I chose my way out of Africa through Sudan and Libya.

Sudan is the second major country of transit for Eritreans. As discussed above, some respondents leave Eritrea directly to Sudan, while others enter Ethiopia first. The main factor determining the country of exit is where in the individual lives in Eritrea and which border is closer and more accessible, or if being smuggled out of Eritrea, which border the smuggler chooses. Several respondents stated that when leaving Eritrea or Ethiopia they were intending to go to Sudan to find work and make a life in Sudan. However, the harsh conditions, lack of legal permits, and abuse of Eritreans in Sudan propel people to leave. Respondents regularly reported being stopped by police for their papers and having to pay the police officers, having landlords request arbitrary rent even after the rent had been paid, not being paid for their work, and being abused. One woman reported that when she was eight months pregnant a police officer hit her in the stomach with a baton on the street and that she then lost the baby. When she became pregnant again a few years later she decided she needed to leave Sudan.

Navigating Sudan is difficult due to the conditions in the country and for most Eritreans stay in Sudan is no longer a possible option. Migrants freedoms are inherently linked to their freedom to be able to stay in a place (Sager Citation2008; Schapendonk and Steel Citation2014) and it clear that Sudan is not welcoming for Eritreans to stay. Abraham explained:

Nowadays there are few Eritreans left in Sudan. Even if they want to stay in Sudan until things in Eritrea get better, the situation in Sudan does not allow them to stay there. So that is why many Eritreans cross to Europe.

The journeys in between these connection points have become more dangerous with kidnappers now active in Ethiopia before the border with Sudan, in Sudan between the border and Khartoum, and leaving Khartoum before entering to Libya. As will be discussed in the case of Libya in the following section, kidnappers capture the migrants en route and extort them for money. Tirhas explained:

While we were on our way to Khartoum we were kidnapped by the Rashaina people. They told us to bring 10,000 dollars. We were four at first including my son but then they bring another 21 people then separate us into two groups. Then they began torturing everyone to bring them money. They beat me a few times but because I had a child with me it's not like the others. The men were beaten naked. There was one man who suffered more than anybody else in the room because he didn't have anyone from the outside. After I stayed for three weeks there, my brother from Germany paid them 6000 dollars and then a Rashaidan woman took me to Khartoum. She paid 200 dollars for me to enter Khartoum and connected me with people who can take me to Libya. I stayed for five days in the process before entering Libya. They told me they will take care of me because I had a child with me. Then we crossed the Sahara and entered Libya.

For Nigerians, the journey through Niger to Libya was generally straightforward. Upon arrival in Agadez, they hire a smuggler to take them to Libya. Usually the stay in Agadez was just a few days while this was sorted out, but could be as long as a few months. In the event that a respondent did not have the funds to go to Libya right away they sought to find work in Agadez to pay for the transfer. Then the respondents reported being packed in vehicles and taken through the desert to Sabha, a journey which also lasted a few days. This journey was difficult with little food and water and a few respondents reported that their convoys lost people in the dessert. Although a difficult aspect of the journey, for most respondents once en route it was a relatively short part. It is important to stress that research has demonstrated high levels of abuse of migrants and rape of women along this part of the journey (IOM Citation2016). This was not raised by the respondents, however, does not mean it did not occur. For this research, it was not deemed necessary to ask about traumatic events that could do harm to the respondents in the interview process.

Surviving and escaping Libya

Eritrean and Nigerian respondents had contrasting expectations and experiences in Libya. First, it is important to stress that for most Nigerian respondents Libya was their intended destination when leaving Nigeria and intended as a destination for work and safety. Respondents were not aware of the conflict and insecurity in Libya prior to arrival. For Eritreans, Libya was never the destination and only viewed as a necessary step in getting to Europe. Eritreans were highly knowledgeable regarding the conditions in Libya, knew they would have to pay the extortionists and prayed that they would not have bad experiences in Libya.

Second, it is important to recognise that Eritrean and Nigerian migrants enter Libya from different sides of the country; they enter different territories that are controlled by different militia or tribal groups. Eritreans enter Libya in the South-east, which is Toubou controlled territory. The Toubou have established a monopoly control of trade, smuggling, and trafficking from the Horn of Africa and through their networks they are able to efficiently move migrants from entry into Libya in the southeast to the north for disembarkation on the Mediterranean Sea (Reitano and Shaw Citation2017). Eritreans pay a smuggler in Sudan that takes them to the Libya/Sudanese border. Here they are left to wait (sometimes for days) until the Libyans arrive. In Libya they are taken to a holding facility where they are told a fee to pay and must transfer the money before they can continue with their journey. This system of kidnapping and extortion is anticipated and expected (Kuschminder and Triandafyllidou Citation2020).

Nigerians on the other hand, enter in the South-west of the country. This territory has been contested since the fall of Qaddafi between the Tebu and Toureg (Shaw and Morgan Citation2014). Nigerians are most commonly they are taken Sabha. Here they may be able to meet with existing social networks in Libya and work, or they may also be detained by smugglers, left on the street to find their own way or arrested by police. The experiences vary between those that are able to work versus those that are detained or captured by smugglers, militia groups or the police. Nigerians thus face a variety of different situations of abuse and exploitation in Libya, unlike the Eritreans who all face a similar path. The differences in geography of the route and the reflecting tribal groups control of east versus west Libya are a central factor in shaping the social environment faced by the respondents and their different experiences.

Eritreans expected that they would be detained by kidnappers in Libya and would have to pay/ have their families send money for their release and disembarkation to Italy. With this information at hand, several respondents actively strategised how to survive Libya and pass through quickly. Durations of stay in Libya ranged from one week to over a year, and this is highly dependent on one’s ability to have the money transferred. Whereas Belloni (Citation2016) found that Eritreans seek to get to Libya as once there their families will be forced to pay for their freedom, my findings suggest that instead, in particular female Eritreans and those travelling with children, prefer to stay in Sudan or Ethiopia until they are assured the money is available for their passage through Libya.

Adiam lived in Sudan for three years, when she became pregnant. She decided that Sudan was no place for children and that it was time for her to leave. After the birth of her daughter she contacted her uncle in Israel who had helped to pay for her mother’s passage through Libya three years earlier. He told her to wait until he had enough money to buy her a plane ticket from Khartoum to Tripoli so that she would not have to travel past the kidnappers in Libya and to reduce her risk. Once she heard this, she felt she knew that her uncle had enough money to send to the kidnappers in Libya over the land route. Knowing that the money was available she planned her journey. She left her uncles number with her friend and told her to call him three days after she had left to inform him that she had gone to Libya and to prepare the money so that it could be paid quickly. When she was captured in Libya she was released within a week as her uncle had received the phone call, quickly mobilised the funds and paid the money transfer immediately upon contact with the smugglers. Arguably, she also experienced some luck, and with a total journey time of three weeks in Libya she crossed the sea to Italy without her or her daughter having suffered any abuse in Libya.

Adiam’s story stresses how she managed the migration control industry in Libya through preparedness and mobilising her transnational connections. Like all Eritreans travelling to Libya, she was highly aware of the situation she would face, however, unlike Belloni’s (Citation2016) respondents and many others that go to Libya without resources, she mobilised her resources so that she could navigate her way through Libya without being subject to abuse and torture. In her case, her strategy was successful and she passed quickly through Libya.

Most Eritreans have transnational connections that they are able to mobilise to pay for their passage through Libya, however, there are some Eritreans who do not have such networks, or who’s networks cannot mobilise the resources to support them. One respondent in this situation was held in Libya for a year and regularly beaten to send the money. After one year, his captors released him and sent him to Italy recognising that they were not going to receive their payment. According to respondents, many who cannot pay are not released and are killed or remain trapped in Libya.

As mentioned at the beginning of this section, Nigerians on the other hand, were mostly unaware of the conditions in Libya and resultantly were surprised to encounter the discrimination, violence, and extortion occurring in the country. Most of the respondents were migrating to Libya as their intended destination for safety from the situation facing them in Nigeria or to find work and a better salary. Therefore, the situation in Libya was a surprise to many respondents and recounted as highly traumatic. Unlike Eritreans who were primarily in captivity in Libya, many Nigerians were living and working outside of captivity. This meant that the Nigerians were exposed to different forms of abuse, discrimination and exploitation than the Eritreans.

Some Nigerians had worked in Libya for several years before coming to Italy. Abu owned a shop in Libya and lived there for seven years. When the Libyan Civil War began in 2011 he left back to Nigeria. After the conflict settled he returned to his shop in Libya and due to the worsening situation in Nigeria his wife joined him with their two children. Abu said:

Last year I was living a normal life, I didn’t have any problems and the place was peaceful. May last year crisis came there, which was ISIS. They came there and took over. There was a lot of crisis over there, even my first daughter a bullet met her and she died there … From there we moved; there was crisis all over. One Arab man helped us to Italy.

Both Abu and Solomon had to respond to a crisis situation that emerged quickly and unexpectedly in Libya. With these changes in their social environment their trajectories changed as well and they made the journey to Italy, which they had never intended. Neither Abu nor Solomon were victim to the migration industry, kidnappers or extortion, but they were victim to the anarchy of a rapidly changing social environment in Libya that became hostile and deadly towards migrants. They acted quickly in an environment of constrained choice to ensure their survival. Their exit was reliant on networks of locals to assist them, not transnational co-ethnics in other countries. Unlike the Eritreans that relied on constant communication and advice from other migrants, Abu and Solomon navigated their way with limited information and on rapid decisions.

For other respondents, Italy was the destination upon leaving Nigeria. Emmanual, a young 16-year-old boy, decided to leave Nigerian after his aunt, the main provider for himself and siblings, left for Italy and was not heard from. He decided that there was nothing in Nigeria for himself, younger sister of 14 years, and little brother of six years. Their father, a teacher, had died a year earlier and their mother was not well. Their aunt left to make money to pay for their school fees, but without hearing from her, Emmanual decided they needed to leave as well. Upon arrival in Sabha, Emmanual and his siblings were captured and detained in a Libyan compound. The Libyan man told Emmanual that his driver had not paid the fine and he would have to get the money. Emmanual told the man they had no family and could not get the money, so a deal was made that Emmanual would work for the money for himself, sister, and brother. He was to be paid 300 dinar per month and had to pay 1200 dinar for each person, so expecting to work for one year. After three months, the compound they were in was bombed. One of the walls of the compound was destroyed in the bombing and all the detainees started to run out of the compound. Emmanual took the opportunity to collect his sister and brother and ran and escaped the compound. They did not know where they were going, but took the risk to escape their capture. Emmanaul looked for other Africans to help them and to find a ‘connection’ man to help them get out of Libya. They found some other Africans who took them to a ‘connection’ man. Emmanual said ‘we begged him, my sister begged him and we cried, we told him our story. So, he said okay … He took us to Tripoli as his sons and daughters and from Tripoli he pushed us for free’.

Emmanuals story shows how he navigated through several stages of a rapidly changing environment in Libya wherein his choices were also constrained and he was fighting for freedom and survival. First, he successfully negotiated for the planned release of his family with his captors to work off their captivity, saving them from potential abuse for not delivering the money. Then, his survival instincts took hold as he escaped through the broken wall with the other captors and took a risk into the unknown for their next steps. Schapendonk (Citation2017) refers to this as the ‘the art of improvisation’. Next, through both a chance encounter and their further negotiation his family was provided safe passage out of Libya. Emmanual and his family could have been recaptured by other Libyans before they found Africans to assist them, or could have been taken to another connection man that was unwilling to help them. In this case, by chance, they were assisted by the connection man who placed them as his own children to give them free passage to Italy. Their fate could have been much worse, but the three minors actively worked together to navigate through the web of actors in Libya.

Nigerians and Eritreans survival strategies and experiences were different in Libya. Nigerians survival strategies included seeking help from other West African migrants, sometimes receiving assistance from Libyans, and taking opportunities where they could. Nigerians ended up in situations of vulnerability in different ways in Libya than by the regularised and anticipated extortion experienced by the Eritreans. For both groups, Libya was undeniably a nightmare of risk and abuse that required strong navigation to survive and escape.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper examines how Eritrean and Nigerian migrants navigate their journeys prior to disembarkation in Libya and contributes to the framing of migrants as actors within their journeys using the concept of social navigators. The results demonstrate the dangers of journeys prior to disembarkation and the heterogeneity of these journeys. The findings stress the importance of understanding the differences in experiences of routes through Libya, which is based on point of entry and the resulting tribal control of the territory being traversed.

The results also highlight the differences in expectations and destination choices of the Eritrean and Nigerian migrants. From both countries, for several migrants Italy was not the intended destination choice, but the ‘the only destination left’ (Squire et al. Citation2017). This paper provides further evidence in challenging assumptions of Europe and Italy as migrants’ destination choice, and instead shows how the shrinking space of protection within Africa is leading to onwards migration to Europe. This paper has illustrated the oppressive environments that migrants navigate on their journeys before disembarkation through examples of kidnapping, extortion, terrorism, death, and abuse.

Returning to the beginning of the paper, three elements were suggested as essential in conceptualising social navigation of the migration journey. The first is the notion of the future being based on an unknown imaginary. For the Eritreans, the kidnapping and extortion was knowingly endured for the future imaginary of safety and freedom in Europe. Nigerians were less aware of the obstacles that they would face in their journeys; however, the idea of safe future elsewhere was always central in their minds.

Second, information awareness, gathering, and processing is an essential part of making decisions regarding the journey and it is evident that transnational networks play a vital role in this. Eritreans had wide access to information from their transnational networks that offered advice on movement and provided the financial capital required for their mobility. Although this information was deemed useful, it was not able to protect them from the kidnapping and extortion experienced in Libya, nor was it expected to protect them. This reflects that although useful, information itself may not be able to alleviate risk on these dangerous journeys. Nigerians had far less access to information. In certain cases, networks within Libya were essential for providing critical information that enabled onwards movement and survival.

Finally, this paper has demonstrated how migrants react and respond within situations of constrained choice. The example of Emmanual demonstrated how he made quick decisions when opportunities presented themselves to enable the mobility of himself and his family and to be able to survive. This relates to how trajectories are formed and changed by reactivity and situations of chance. This paper contributes to a growing literature that critically interrogates migration journeys, policy assumptions, and the role of migrants within their own journeys.

Acknowledgements

The author expresses gratitude to the Comune di Milano, Fon-dazione L’Albero della Vita and Fondazione Progetto Arca onlus for supporting and assisting in this research. Many thanks to Anna Triandafyllidou for offering valuable comments on an earlier draft and to Yordanos Mehari for excellent research and translation assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Belloni, M. 2016. “My Uncle Cannot Say “No” if I Reach Libya: Unpacking the Social Dynamics of Border-Crossing among Eritreans Heading to Europe.” Human Geography 9 (2): 47–56. doi: 10.1177/194277861600900205

- Benezer, G., and R. Zetter. 2015. “Searching for Directions: Conceptual and Methodological Challenges in Researching Refugee Journeys.” Journal of Refugee Studies 28 (3): 297–318. doi: 10.1093/jrs/feu022

- Dekker, R., G. Engbersen, J. Klaver, and H. Vonk. 2018. “Smart Refugees: How Syrian Asylum Migrants Use Social Media Information in Migration Decision-Making.” Social Media+Society 4 (1). doi:10.1177/2056305118764439.

- Denov, M., and C. Bryan. 2012. “Tactical Maneuvering and Calculated Risks: Independent Child Migrants and the Complex Terrain of Flight.” New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 2012: 13–27. doi:10.1002/cad.20008.

- Gladkova, N., and V. Mazzucato. 2017. “Theorising Chance: Capturing the Role of Ad Hoc Social Interactions in Migrants’ Trajectories.” Population Space and Place 23 (2): e1988. doi:10.1002/psp.1988.

- Havinga, T., and A. Böcker. 1999. “Country of Asylum by Choice or by Chance: Asylum Seekers in Belguim, the Netherlands and the UK.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 25 (1): 43–61. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.1999.9976671

- Horwood, C., and K. Hooper. 2016. “Protection on the Move: Eritrean Refugee Flows through the Greater Horn of Africa.” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/protection-move-eritrean-refugee-flows-through-greater-horn-africa.

- IDMC. 2018. http://www.internal-displacement.org/countries/nigeria.

- IOM. 2016. Assessing the Risks of Migration Along the Central and Eastern Mediterranean Routes: Iraq and Nigeria as Case Study Countries. Berlin: IOM.

- Kuschminder, K., and A. Triandafyllidou. 2020. “Smuggling, Trafficking, and Extortion: New Conceptual and Policy Challenges on the Libyan Route to Europe.” Antipode 52 (1): 206–226. doi: 10.1111/anti.12579

- Mainwaring, D., and N. Brigden. 2016. “Beyond the Border: Clandestine Migration Journeys.” Geopolitics 21 (2): 243–262. doi: 10.1080/14650045.2016.1165575

- Mallett, R., and J. Hagen-Zanker. 2018. “Forced Migration Trajectories: An Analysis Of Journey- And Decision-Making Among Eritrean And Syrian Arrivals To Europe.” Migration And Development 7 (3): 341–351. doi:10.1080/21632324.2018.1459244.

- McAuliffe, M. 2016. “How Transnational Connectivity is Shaping Irregular Migration: Insights for Migration Policy and Practice From the 2015 Irregular Migration Flows to Europe.” Migration Policy Practice VI (1): 4–10.

- McMahon, S., and N. Sigona. 2018. “Navigating the Central Mediterranean in a Time of ‘Crisis’: Disentangling Migration Governance and Migrant Journeys.” Sociology 52 (3): 497–514. doi:10.1177/0038038518762082.

- Overseas Development Institute (ODI). 2017. Journeys on Hold: How Policy Influences the Migration Decisions of Eritreans in Ethiopia. London: ODI.

- Reitano, T., and M. Shaw. 2017. “Libya: The Politics of Power, Protection, Identity and Illicit Trade.” United Nations University Centre for Policy Research. https://i.unu.edu/media/cpr.unu.edu/attachment/2523/Libya-The-Politics-of-Power-Protection-Identity-and-Illicit-Trade-02.pdf.

- Rosberg, A. H., and K. Tronvoll. 2017. Migrants or Refugees? The Internal and External Drivers of Migration From Eritrea. Oslo: International Law and Policy Institute.

- Sager, T. 2008. “Freedom as Mobility: Implications of the Distinction Between Actual and Potential Travelling.” In Spaces of Mobility. The Planning, Ethics, Engineering and Religion of Human Motion, edited by S. Bergmann, T. Hoff, and T. Sager, 243–267. London: Equinox.

- Schapendonk, J. 2017. “Navigating the Migration Industry: Migrants Moving Through an African-European web of Facilitation/Control.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1315522.

- Schapendonk, J. 2018. “Navigating the Migration Industry: Migrants Moving Through an African-European Web Of Facilitation/Control.” Journal Of Ethnic And Migration Studies 44 (4): 663–679. doi:10.1080/1369183x.2017.1315522.

- Schapendonk, J., M. Bolay, and J. Dahinden. 2021. “The Conceptual Limits of the ‘Migration Journey’. De-exceptionalising Mobility in the Context of West African Trajectories.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (14): 3243–3259. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804191.

- Schapendonk, J., and G. Steel. 2014. “Following Migrant Trajectories: The Im/Mobility of Sub-Saharan Africans en Route to the European Union.” Annals of the Association of American Georgraphers 104: 2.

- Schapendonk, Joris, Ilse van Liempt, Inga Schwarz, and Griet Steel. 2018. “Re-Routing Migration Geographies: Migrants, Trajectories and Mobility Regimes.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.06.007.

- Shaw, M., and F. Morgan. 2014. llicit Trafficking and Libya’s Transition: Profits and Losses. United States Institute of Peace. Accessed January 26, 2018. https://www.usip.org/publications/2014/02/illicit-trafficking-and-libyas-transition-profits-and-losses.

- Snel, E., Ö. Bilgili, and R. Staring. 2021. “Migration Trajectories and Transnational Support Within and Beyond Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (14): 3209–3225. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1804189.

- Squire, V., A. Dimitriadi, N. Perkowski, M. Pisani, D. Stevens, and N. Vaughan-Williams. 2017. “Crossing the Mediterranean Sea by Boat: Mapping and Documenting Migratory Journeys and Experiences.” Final Project Report. www.warwick.ac.uk/crossingthemed.

- Triandafyllidou, A. 2017. “Beyond Irregular Migration Governance: Zooming in on Migrants’ Agency.” European Journal of Migration and Law 19 (1): 1–11. doi: 10.1163/15718166-12342112

- Triandafyllidou, A. 2019. “The Migration Archipelago: Social Navigation and Migrant Agency.” International Migration 57 (1): 5–19. doi:10.1111/imig.12512.

- Vigh, H. 2006. “Social Death and Violent Life Chances.” In Navigation Youth, Generating Adulthood: Social Becoming in and African Context, edited by Catrine Christiansen, Mats Utas, and Henrik Vigh, 10–31. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Vigh, H. 2009. “Motion Squared: A Second Look at the Concept of Social Navigation.” Anthropological Theory 9 (4): 419–438. doi: 10.1177/1463499609356044