ABSTRACT

Why do local governments develop policies for the reception and integration of forced migrants? What strategies do they employ in pursuing their own policy objectives in this field, especially within restrictive institutional and financial frameworks? In this article, I use an assemblage approach and insights from extensive desk and field research to study the successful migration policy activism of the Municipality of Thessaloniki in Greece. I argue that the initiatives of mayors and access to external funds can both trigger and facilitate the development of local reception and integration policies. In addition, I argue that horizontal and vertical coalitions with local, transnational and international partners may help local governments effectively exploit their space for discretion in migration and integration policy-making. Based on my findings, I emphasise the need to further examine the emerging relationships between United Nations (UN) organisations and local authorities in the field of migration governance. Furthermore, I advocate a broader application of the assemblage approach in migration policy research.

Introduction

Recent research has shifted the traditionally national perspective in forced migration studies to the local level, highlighting the potential role of cities as active subjects in the reception and integration of asylum seekers and refugees (Doomernik and Ardon Citation2018; Doomernik and Glorius Citation2016). A further impetus for this shift was the ‘long summer of migration’ in 2015, when local governments across Europe demonstrated unusual policy activism in this domain, often developing more welcoming and inclusive approaches than the respective national governments (Glorius and Doomernik Citation2020). Municipal policy innovations related to the arrival and settlement of forced migrants included the development of alternatives to state reception (Geuijen et al. Citation2020; Hinger, Schäfer, and Pott Citation2016) and local assistance with civic and labour market integration (Scholten et al. Citation2017).

Nevertheless, the proactive engagement of local governments in policy-making for forced migrants has remained on the margins of the ‘local turn’ in the study of migration governance (Zapata-Barrero, Caponio, and Scholten Citation2017). Consequently, the question of their motives for becoming active subjects in the reception and integration of asylum seekers and refugees remains open. The same applies to questions regarding the strategies used by local governments in pursuit of their own objectives in these policy areas. In addition to academic relevance, explaining the underlying reasons and pathways towards successful local policy initiatives for forced migrants also has a practical value. In the face of reception conditions that consistently fail to meet the standards of international and European Union (EU) law – especially in the Southern EU Member States – policy activism by local governments may help protect the fundamental rights of forced migrants (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights Citation2019).

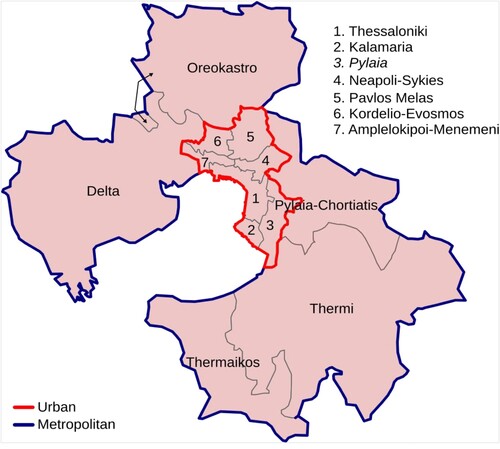

This article aims to contribute to the scholarly and practitioners’ debates on local policies for asylum seekers and refugees. To this end, it zooms in on Thessaloniki – the second largest city in Greece and a recent arrival point for forced migrants. Within just a few years, the Municipality of Thessaloniki has undergone a remarkable transformation from a complete novice to a laboratory for innovative reception and integration policies, at least in the Greek context. When the main migration route from Greece to Western Europe – the so-called ‘Balkan route’ – was closed in early 2016 under pressure from a number of EU Member States, approximately 10,000 people were transferred to the metropolitan area of Thessaloniki, effectively turning the city from a place of transit to a place of permanent settlement for forced migrants. Under these circumstances, the local government of Thessaloniki – the largest of the 11 self-governing municipalities in the metropolitan area () – gradually designed and enacted a coherent set of progressive policies for the newcomers (Municipality of Thessaloniki Citation2018a), in stark contrast to the lack of such a policy plan at the national level (Greek Ombudsman Citation2017).Footnote1 From housing, to equal access to information and services, to social cohesion and political participation, the municipal approach focused on the long-term integration of immigrants from the outset (Arrival Cities Citation2016). In this way, Thessaloniki not only filled many of the gaps in service provision left by the national authorities, but also developed its own local approach to address immigration.

Figure 1. The urban and metropolitan areas of the city of Thessaloniki with its 11 self-governing municipalities, including the Municipality of Thessaloniki (1). Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Thessaloniki_urban_and_metropolitan_areas_map_2.svg.

Thessaloniki’s policy activism constitutes a particularly compelling case study, given the very restrictive institutional and financial framework in which it emerged. In the highly centralised Greek administrative system, the central government has exclusive competence in the reception of asylum seekers, as well as in integration-related policy areas, such as healthcare, employment and formal education. While a major reform called Kallikratis (Law No. 3852/2010) gave local authorities an opportunity to develop additional social welfare policy initiatives, no funds were allocated to them for this purpose (Koulocheris Citation2017; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Citation2018, 12). Moreover, direct financial transfers from the central to the local level of government – the main source of funding for Greek municipalities – were cut by 60% in the period 2009–2014 amidst the country’s severe economic crisis (Hlepas and Getimis Citation2018, 61). Hence, Thessaloniki’s policy-making in the field of reception and integration of forced migrants seems unusual, especially in light of the fact that the municipality was on the verge of bankruptcy in early 2016 (CNN Greece Citation2016). It is therefore an ‘extreme case’ of both theoretical and practical importance (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008).

Against this backdrop, I focus on the questions of why and how Thessaloniki’s local government developed its own progressive reception and integration policies for asylum seekers and refugees: what were its motives to engage in actions that fall outside its mandate, and what strategy and resources did it use to overcome the aforementioned structural limitations? To answer these questions, I adopt an assemblage approach, combined with a process tracing technique, and data from extensive desk and field research. I analyse the local policy-making process through the lens of a reception and integration policy assemblage: a collection of actors and factors that originate at different levels, but directly or indirectly affect events at the local level. Within Thessaloniki’s policy assemblage, I identify various actors and factors that facilitated the municipality’s successful policy activism. More specifically, I argue that the municipal reception and integration policies were largely the result of the discernment of the local mayor, who took advantage of the opportunities that the 2015 ‘adhocracy’ in the area of migration governance offered. Furthermore, I argue that Thessaloniki’s policies were developed and enacted by virtue of external funds, human capital and know-how, to which the municipality gained access through the formation of horizontal (with local and transnational partners) and vertical coalitions (with UN agencies and international donor organisations).

I start with a discussion of the analytical challenges related to the inherent complexity of contemporary local migration policy-making, and present several arguments for applying the assemblage approach in the study of local reception and integration policies for forced migrants. Subsequently, I briefly outline the methodology of the research, followed by a detailed analysis of the evolution of Thessaloniki’s reception and integration policy assemblage. I then discuss the reasons behind Thessaloniki’s successful policy activism, as well as the added value of assemblage thinking for migration policy research. Finally, I conclude with suggestions for future research.

Local migration policy-making and the assemblage approach

The development of local policies for immigrants is a complex, multi-level and polycentric process (Caponio and Jones-Correa Citation2017). While the outcomes of this process mainly relate to concrete urban contexts, its causes can originate in very distant times and locations. Particularly with regard to forced migrants, cities have been described as ‘landscapes’ (Hinger, Schäfer, and Pott Citation2016) or ‘battlegrounds’ (Ambrosini Citation2020) – meeting points, where multiple jurisdictions intersect, and where different levels of government negotiate their authority on migration issues (Filomeno Citation2016; Zapata-Barrero, Caponio, and Scholten Citation2017), influenced by civil society and the private sector (Mayer Citation2018, 245). UN agencies (Thouez Citation2018), (international) non-governmental organisations ((i)NGOs) (Sunata and Tosun Citation2019), national governments (Gebhardt Citation2016), mayors (Terlouw and Böcker Citation2019), and transnational city networks (Caponio Citation2018) represent only a fraction of the actors that can directly or indirectly influence the course of local migration policy-making. At the same time, the decisions of all these actors are shaped by various ‘non-human’ structural factors from different levels, such as available resources, labour market conditions, etc. In short, local policies for the reception and integration of forced migrants are hardly ever just ‘local’ (Bazurli Citation2020).

The overwhelming complexity surrounding migration policy-making becomes particularly apparent when one zooms in on local responses to the arrival of forced migrants in Greece. Until a few years ago, the reception and integration of refugees was low on the agenda of the Greek state. However, this changed in early 2016, when tens of thousands of asylum seekers were stranded in the country (Koulocheris Citation2017). The intensity of the events and some hasty institutional novelties (EU-Turkey statement, new domestic Law No. 4375/2016 regulating asylum and reception, establishment of a Ministry of Migration Policy), led to a situation of ambiguity as to who was responsible for what, where, when and how. Some municipalities – including the Municipality of Thessaloniki – suddenly turned into places of arrival, where a plethora of public and civil society actors supported forced migrants with minimum or no coordination, often acting outside any legal and policy frameworks. At the same time, these emerging ‘asylum landscapes’ (Hinger, Schäfer, and Pott Citation2016) were influenced by contextual factors at different levels, such as unprecedented financial assistance from the EU (Howden and Fotiadis Citation2017), and the reduced capacity of the Greek public sector due to prolonged austerity measures (Hlepas and Getimis Citation2018).

To unravel the complexity in Thessaloniki’s reception and integration policy-making process, while at the same time avoid over-reductionism, I rely on an assemblage approach (Savage Citation2020). Assemblages are ‘wholes whose properties emerge from the interactions between parts’ (DeLanda Citation2006, 5), ultimately generating certain effects (Bennett Citation2009, 24). They are constructed by heterogeneous human and non-human elements that ‘come together in productive relations to form apparently whole but mobile social entities’ (Youdell and McGimpsey Citation2015, 119). In the social sciences, the assemblage approach is particularly useful for the development of conceptual frameworks that adequately capture the complexity of social formations (Youdell Citation2015, 118), especially in studies of intermediate entities (DeLanda Citation2006).

As an analytical tool, the assemblage approach has been applied in studies on policy development in the fields of education (Youdell Citation2015), youth services (Youdell and McGimpsey Citation2015) and public infrastructure reform (Ureta Citation2015). Its added value for policy research stems from the alternative point of departure it offers. Rather than viewing policies as the object of study – as in traditional policy sociology – the assemblage perspective views them as just one of the elements of a broader process of change, encompassing actors, factors and forces from different levels (Youdell Citation2015, 11). Local policies are therefore analysed as ‘experiments involving multiple and messy elements’ (Ureta Citation2015, 169). While the policy assemblage approach integrates the reorientation in policy research from the notion of government to the notion of governance, it also offers more dynamic and flexible concepts than other approaches, such as the policy network theory (Rhodes Citation2007) and multi-level governance (Caponio and Jones-Correa Citation2017), mainly because it prioritises the causal capacity of elements belonging to the broader policy context. In other words, instead of reducing complexity by focusing on the policy itself, the researcher unravels it by ‘distilling’ the assemblage of actors and factors as the new object of study.

Based on this analytical approach, I examine Thessaloniki’s response to the arrival of refugees through the lens of a local reception and integration policy assemblage. My first aim is to shed light on the processes of assembling, disassembling and reassembling of different elements over time (Youdell and McGimpsey Citation2015), and the formation of different ‘configurations’ within the policy assemblage (Ureta Citation2015). The term ‘configurations’ refers to combinations of elements that can either limit or facilitate the development of local migration policies. I identify four such configurations within Thessaloniki’s local reception and integration policy assemblage: adhocracy, horizontal coalition, vertical coalition and institutionalisation. These configurations partially correspond to chronological periods within the municipality’s migration policy-making process. However, instead of fixed, stable entities or phases, they should be seen as temporary and dynamic constructions, which can overlap and mix (Ureta Citation2015). By focusing on these configurations and the dynamics within and between them, I explain why and how the municipality developed its local policies for forced migrants.

Methodology

Scholars who study policy development from an assemblage perspective inevitably face the challenge of longitudinally mapping a large number of heterogeneous assemblage elements, along with their individual and collective characteristics and productive forces. Several methodological approaches have been suggested to address this issue. While Ureta (Citation2015) relied on genealogy, others have advocated the use of assemblage ethnography (Greenhalgh Citation2008; Youdell and McGimpsey Citation2015). I choose an alternative approach and apply process tracing (Bennett and Checkel Citation2014; George and Bennett Citation2005). Process tracing can be defined as

a procedure for identifying steps in a causal process [the complex relations between the elements and the configurations of the local reception and integration policy assemblage] leading to the outcome of a given dependent variable [local reception and integration policies] of a particular case [the Municipality of Thessaloniki] in a particular historical context [during the recent period of increased arrivals of forced migrants]. (George and Bennett Citation2005, 176)

The evidence I present in the following analysis is based on extensive desk research, including the review of legal/policy documents (EU, national and local level), municipal proceedings (46 in total for the Municipality of Thessaloniki and 135 for other municipalities in the metropolitan area), media publications and press releases from 2014 until April 2020, as well as secondary academic sources. In addition, a 3-month fieldwork was carried out in Thessaloniki at the end of 2018, during which a total of 28 semi-structured interviews were conducted with representatives of local municipalities, the regional government, the Ministry of Migration Policy, local (i)NGOs and international organisations operating in the city’s urban area (see Appendix). The desk research data were used to identify key respondents, design interview topic lists and for triangulation. Moreover, the first sample of respondents was expanded through snowball sampling. All data were incorporated into and analysed with NVivo 11.

Thessaloniki’s reception and integration policy assemblage

In this section, I present the development of Thessaloniki’s reception and integration policies by systematically analysing the formation of the aforementioned four configurations of the local policy assemblage – adhocracy, horizontal coalition, vertical coalition, and institutionalisation – along with their constitutive elements.

Adhocracy

Until the recent ‘refugee crisis’, Thessaloniki hosted less than two percent of the migrants seeking international protection in Greece.Footnote2 The vast majority of asylum seekers lived in Athens, where asylum interviews took place and where decision-making authorities were located. From the beginning of 2015, however, the presence of forced migrants in Thessaloniki started to increase. Homeless migrants, including families with young children, were often seen on the streets (T19). Rather than being their final destination, Thessaloniki had become an important ‘transit point’; up to 1,000 migrants passed through the city every week on their journey to Western Europe via the Balkan route (Arrival Cities Citation2016, 31).

This new reality led to a number of autonomous solidarity initiatives for people on the move. Local grassroots organisations, schools and immigrant associations, among others, offered various services, such as food, basic healthcare and legal advice (Dicker Citation2017). Thessaloniki’s local government joined this ad hoc support structure in two ways. First, it opened a large warehouse where in-kind donations for refugees were collected and redistributed. Second, it started providing hotel accommodation and basic support to the most vulnerable migrants, with the help of a grant from an international donor organisation. Since the municipality lacked both personnel and expertise in the reception of forced migrants, this initiative was only possible through the collaboration with local NGOs that provided services such as health monitoring and legal support. In any case, until the end of 2015, the efforts of the municipality remained only ‘a small part within a large, widespread solidarity movement’ (T19).

Meanwhile, approximately 70 km northwest of Thessaloniki, in the small village of Idomeni on the border between Greece and North Macedonia, two crucial elements of the adhocracy configuration began to take shape: the administrative vacuum in the governance of reception and the impending closure of the Balkan route. The Greek government had just established its Ministry of Migration Policy, which had only one employee in its regional office in Thessaloniki (T19). Acknowledging its inability to provide adequate protection to arriving migrants, the government requested the support of the EU and the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) (Thouez Citation2018). As a result, the EU Commission allocated a large amount of funding to Greece, while the UNHCR and other UN agencies, as well as humanitarian organisations started operating in the country. Idomeni was ‘overrun’ by a plethora of international organisations, (i)NGOs, local grassroots organisations and volunteers, who collaborated and competed with each other in assisting migrants (Anastasiadou et al. Citation2017). These supranational and subnational actors completely replaced the Greek state in the provision of all services except security (Maniatis Citation2018). The result was the emergence of a system of humanitarian adhocracy (Dunn Citation2012) characterised by chaos, instability and little to no concern for institutional frameworks, governed by an ‘invisible elbow’ rather than any real authority (Tilly Citation1996).

At the same time, the increasing reluctance of some EU Member States to accept migrants foreshadowed the impending border closures. As of December 2015, only migrants of certain nationalities were allowed to cross from Greece into North Macedonia, while Idomeni turned into a sprawling refugee camp hosting thousands of people (Anastasiadou et al. Citation2017). It was easy to imagine that the border would soon close for good, and that the stranded migrants would then head towards Thessaloniki, which is the nearest major city (T19). Against this background, the municipal authorities in the area realised that they were about to face a serious challenge in an area where they had no mandate and no extra resources. Caught between a rock and a hard place, the municipalities repeatedly requested the government to draw up a comprehensive plan to address the emerging issues, and suggested that it allocates powers and resources to the local level – however, they received no response (Regional Union of Municipalities of Central Macedonia Region Citation2015). Especially in the municipality of Thessaloniki, the ‘alertness’ that could be felt by the political leadership and administrative staff indicated the growing realisation that the vacuum in the governance of reception was not limited to Idomeni, but that it was about to directly affect the city of Thessaloniki as well (T19).

Horizontal coalition

Under these circumstances, the mayor of Thessaloniki, Yiannis Boutaris, stepped in and began to consolidate the municipality’s position at the centre of a wide horizontal coalition, as the second configuration of the local reception and integration policy assemblage. He initiated several meetings in the town hall, inviting representatives of other municipalities from the metropolitan area and local civil society. His aim was to bring all local stakeholders together and prepare a common plan to address the consequences of the expected border closure. The mayor of Thessaloniki used three arguments to convince others of the need to proactively combine their efforts. First, he stressed the humanitarian duty of municipal governments to help refugees. Second, he argued that even if one disagreed with the humanitarian argument, neglecting the issue and leaving the arriving people on their own would create serious problems for the municipalities. Finally, for those who were still not convinced, he presented his third and perhaps strongest argument: ‘In the time coming, it will rain money for the refugee issue, and then – you will hold an umbrella.’ (T19)

In other words, Mayor Boutaris suggested that, at a time when locals were struggling due to severe austerity measures and high unemployment, municipal authorities could play a key role in turning the crisis into an opportunity. However, despite this convincing rhetoric, most mayors in the area distanced themselves from the proposal, fearing that any involvement could become a pull-factor for immigrants (T11). Nevertheless, two local governments and a number of NGOs joined forces with the Municipality of Thessaloniki to look for solutions to the challenges ahead.

At the same time, the horizontal coalition within Thessaloniki’s reception and integration policy assemblage expanded transnationally. At the end of 2015, the municipality teamed up with several other municipalities from different EU countries, which were interested in developing local policies for immigrants. The group eventually secured an EU grant and created the URBACT Arrival Cities network (Saad and Essex Citation2018). Each of the partner municipalities committed to developing an action plan in collaboration with local civil society to address a concrete migration-related challenge. In the case of Thessaloniki, the deliverable was a coherent strategy for the reception and integration of forced migrants. As a result, the municipality formalised the already existing informal partnerships within the city, establishing an official ‘URBACT Local Group’ (T9). In addition, separate Memoranda of Understanding (MoU) were signed with several local NGOs working with refugees (T23). In short, the municipality’s participation in the network contributed to the realisation of a ‘more systematic approach’ of collaboration with local partners, mapping the pressing issues in the field of reception and integration, and identifying concrete local policy objectives (T9).

The Arrival Cities network was only the first step of Thessaloniki’s city-to-city collaboration in the field of migration policy-making. Evidence from diverse sources revealed that in just a couple of years, the municipality developed numerous links with other local authorities in Greece and beyond. At the transnational level, Thessaloniki benefitted from the expertise of local level migration policy-makers from Amsterdam and Zurich (Integrating Cities Citation2017), hosted a training for local authorities organised by the Intercultural Cities network (Council of Europe Citation2018), and joined the Integrating Cities initiative of EUROCITIES (Municipality of Thessaloniki Citation2018b). At the national level, Thessaloniki and Athens initiated a city network, bringing together Greek municipalities hosting asylum seekers and refugees (T9, T19). In addition to exchanging know-how and good practices, the network focuses on advocacy at the international, national and regional levels, both in terms of policy and funding (Cities Network for Integration Citation2019). Importantly, this horizontal inter-municipal partnership benefited directly from the technical and capacity-building support of the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) (Citation2019) and the financial support of the UNHCR, which demonstrates the blurred boundaries between the horizontal and vertical coalitions, discussed in more detail below.

Neither the consolidation of the horizontal coalition within Thessaloniki’s urban area, nor its expansion beyond the city were accidental. Rather, they reflected the ‘double opening’ – both internal and external – that Mayor Boutaris envisioned for the municipality as part of his broader and rather progressive political agenda (Municipality of Thessaloniki Citation2019). After his election as an independent candidate in 2010, the mayor ‘opened the door’ to local civil society (T11). This ended a long period of conservative rule in Thessaloniki’s local politics, during which the collaboration of local NGOs with the municipality had been ‘very difficult to impossible’ (T20). In the context of looming social problems, severe budget cuts and insufficient personnel, the local government gradually developed a close collaboration with several local organisations, which filled the gaps in the provision of social assistance and healthcare services to vulnerable people. Taking advantage of this synergy and again with the support of an EU grant, Thessaloniki’s local government opened, in 2015, its ‘Filoxenio’: the first municipality-run shelter for families of asylum seekers in the country (T18). At the same time, city diplomacy and collaboration with international organisations were the mayor’s two priorities in terms of external opening. In his words, international networking brought the municipality know-how and access to funds, and proved more effective than the support of the Greek state, which had limited the economic and administrative autonomy of local governments with its ‘suffocating embrace’ (Municipality of Thessaloniki Citation2019). To shed light on the relevance of the international level to the development of Thessaloniki’s local migration policies, I will now highlight the vertical coalition as the third configuration within the reception and integration policy assemblage.

Vertical coalition

In the spring of 2016, the fears of Thessaloniki’s mayor came true: the border between Greece and North Macedonia was definitively closed and several thousand of migrants were transferred from Idomeni to the Thessaloniki area (Anastasiadou et al. Citation2017). At that time, two parallel reception schemes were created in Greece. On the one hand, the central government opened large reception facilities, which were almost exclusively located outside urban centres. These facilities represented ‘out of sight, out of mind’ solutions that offered little prospect of integrating immigrants into local communities (Kandylis Citation2019; Lohmueller Citation2016). On the other hand, following an agreement between the EU Commission, the Greek government and the UNHCR, the latter received a large EU grant for securing at least 20,000 alternative reception places in urban accommodation (European Commission Citation2015). Although these places were initially only a temporary solution, they soon became an integral part of the Greek reception system (T21).

It is against this backdrop that the consolidation of the vertical coalition configuration within Thessaloniki’s policy assemblage began. To implement its accommodation scheme in the city, the UNHCR relied on (i)NGOs, which could quickly rent hotel rooms and apartments to host the arriving migrants. However, following the initial period of emergency, the UNHCR started looking for sustainable long-term solutions. By that time, Thessaloniki’s local government had already established itself as the leading actor in the aforementioned horizontal coalition. After brief consultations, the municipality of Thessaloniki – in collaboration with two other municipalities in the area and several NGOs – received its first direct grant trough the UNHCR. It used the funding to implement an urban reception project called Refugee Assistance Collaboration Thessaloniki (REACT), which provided accommodation to asylum seekers and refugees in private apartments rented by the municipal authorities, while the NGOs provided services such as legal assistance and socio-psychological support (T24). The project was gradually expanded and offered more than 900 reception places in early 2020.Footnote3

REACT was undoubtedly very important to the municipality because of its large scale (T19). However, it was just one of dozens of initiatives that mushroomed in Thessaloniki after the closure of the Balkan route. The sizeable needs and funding flows from the EU and international private donors quickly led to the proliferation of a local ‘reception and integration economy’, in which (i)NGOs continued developing parallel accommodation projects and providing a range of services to asylum seekers and refugees. This resulted in competition between the different actors working on the ground. However, since the local government relied almost exclusively on local NGOs to implement its policies, it was seen by them not so much as a competitor, but rather as a facilitator that helped attract external funds, which were then redistributed locally (T2, T20).

In this context, the Municipality of Thessaloniki started intensively building close partnerships with supranational actors, primarily with UN agencies operating in the city. A crucial development was the UNHCR’s decision to build capacity within local authorities before eventually withdrawing its operations from Greece (T21). The organisation provided interpreters and cultural mediators to the municipal services and seconded two of its employees to the municipality. These two employees started coordinating a large forum of forty-five locally operating actors, with the aim of improving service provision to migrants (T9). At the same time, Thessaloniki’s local government signed an MoU with the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), which resulted in the secondment of one more employee to the municipality and the development of a number of refugee integration initiatives in the field of non-formal education (T25). Due to its increased visibility and capacity, the municipality was also able to secure additional funding from international private foundations for its refugee-related projects (T19).

Using the funds, human capital and know-how accessed through the vertical and horizontal coalitions, Thessaloniki’s local government gradually developed its own policies for the reception and integration of forced migrants. The municipal management and staff agreed that the municipality could never ‘get the job done’ (T19) without using these external resources to remedy its internal weaknesses (T9, T11). Using process tracing to identify the sequence of events proved particularly helpful in confirming the validity of their statements. It revealed that the economic adjustment programmes that started in Greece in 2010 had largely affected Greek municipalities through continuous cuts in budgets for public spending and staff (Hlepas and Getimis Citation2018). In early 2016, Thessaloniki was close to bankruptcy (CNN Greece Citation2016), while in the period 2010–2019 the number of permanent municipal employees decreased from 5500 to 3000 (Lazopoulos Citation2019). Remarkably, without its external project employees, the municipality with more than 300,000 inhabitants would have had only one psychologist and one social worker (T11). In this context, the emergence of the reception and integration economy became an opportunity for local development; more than 80 new jobs were created within the REACT framework alone, with many young and highly educated locals finding jobs in their field (T11).

At the same time, collaboration with the national government – and therefore its role in the vertical coalition – remained superficial. The regional representatives of the Ministry of Migration Policy were ‘always invited to join’ the aforementioned forum that the municipality coordinated, but they ‘rarely attended’, focusing instead on the large reception facilities in the region (T21). Cooperation between the local and national levels of government was mostly ad hoc and took place only occasionally after a sudden arrival of migrants in the central square of the city, or in other words, when there was an urgent need to resolve an issue quickly (T9). The only significant exception was a nationally designed and EU-funded programme, under which the municipality opened a one-stop-shop mainly providing information to immigrants about the available municipal and NGO services in the area (T24).

Institutionalisation

The final configuration within Thessaloniki’s reception and integration policy assemblage concerns the formal adoption of a local migration policy framework and the unsuccessful attempt of Mayor Boutaris to permanently incorporate migration governance into the municipal administration. In 2018, the municipal council approved the ‘Integrated Action Plan for Integration of Refugees’ (Municipality of Thessaloniki Citation2018a) – a comprehensive set of policy objectives resulting from the participation in the Arrival Cities network and the ‘joint process of strategising’ with international and local partners (T9). The plan established a progressive rights-based approach to reception and integration, aimed at ensuring equal access to municipal services for all immigrants. In line with international human rights standards, it also envisaged the adoption of inclusive policies for undocumented migrants. Finally, the plan paved the way for the mainstreaming of immigrant integration into existing municipal services. At the same time, it maintained initiatives targeting asylum seekers and refugees, despite the limited mandate of the local government in this field.

In addition, a number of administrative changes were made. The mayor appointed a municipal councillor in charge of all migration-related issues and established a task force made up of seconded UNHCR staff and permanent municipal staff. With the support of municipal services, the task force started delivering on the various objectives of the Action Plan, implementing an affordable housing project, a labour market activation programme for refugees and locals, and a weekly radio programme designed and run by refugees, to name but a few. Its role was to serve as a transitional body until the establishment of a separate department for the integration of immigrants within the municipal administration (T9).

However, despite his efforts, the mayor did not succeed in assembling this final element to Thessaloniki’s policy assemblage. The establishment of an immigrant integration department was part of a broader plan to reorganise the administrative structure (T11), which was eventually voted down by the municipal council. This defeat – only a couple of months before the local elections in 2019 – was caused partly by political disagreements (factions within the mayor’s party that emerged after his decision not to run for office anymore), and partly by the opposition of members of the administration to the envisaged broader reform (Lazopoulos Citation2019). As a result, the attempt to embed migration governance into the organisational structure of the municipality ended prematurely, without being reactivated by the subsequent local government.

Discussion

The previous section outlined the key actors and factors that influenced Thessaloniki’s response to the arrival of forced migrants: from the tangled adhocracy, to the impetus provided through horizontal and vertical coalitions, and the incomplete institutionalisation. On the basis of the evidence presented, I now return to the questions of why and how the local government developed its reception and integration policies. In addition, I briefly reflect on the analytical and methodological approaches applied in this research.

To begin with, the above analysis demonstrates that the genesis of Thessaloniki’s reception and integration policies was the product of conjunctural human and non-human assemblage elements operating simultaneously on different levels. In line with previous findings, it shows that the policy response was triggered by local pragmatism (not coping with the issue would only get things worse) (Poppelaars and Scholten Citation2008), negligence on behalf of the responsible authorities (lack of response to the municipal requests), and policy gaps at the national level (no plan for the reception and integration of refugees) (Doomernik and Ardon Citation2018). However, it also shows that these factors represent only one side of the story. While Thessaloniki’s policy activism was undoubtedly enhanced by the facilitating effect of the adhocracy configuration, the municipality remained one of a few in the metropolitan area to develop local policies for forced migrants. The analysis thus points towards two elements that stood out for their primary role in the local policy assemblage: the mayor and the external funds.

The constant positioning of Yiannis Boutaris at the centre of all four configurations of Thessaloniki’s policy assemblage highlights the potential role of mayors, but also the limits of their ability to influence local responses to immigration. On the one hand, it confirms the arguments that mayors qua mayors can make a difference in policy-making for forced migrants (Betts et al. Citation2020; Terlouw and Böcker Citation2019), and that progressive local politicians are more likely to promote inclusive migration policies (de Graauw and Vermeulen Citation2016). Their strong commitment and perseverance can result in both the initiation and proliferation of such policies, despite structural constraints, such as the lack of a clear mandate on migration-related issues. On the other hand, the incomplete institutionalisation of Mayor Boutaris’ policy approach also points to an important risk in new ‘cities of arrival’: the failure to absorb the accumulated project-based know-how into the municipal administration. In this regard, the Thessaloniki experience demonstrates that local political leaders who are committed to developing policies for forced migrants should ‘strike while the iron is hot’. They should use the momentum to transform temporary ad hoc structures into permanent bodies within the municipal administration to ensure the continuity of their local approach to migration governance. Any delays in doing so could jeopardise the long-term sustainability of local policies as a result of new pressing issues appearing on the agenda or changes in government.

Through the dense fog of the adhocracy that had engulfed migration governance in 2015, the mayor managed to discern the second crucial element in Thessaloniki’s policy assemblage: the oncoming ‘rain’ of funds that was about to pour down on Greece. At a time when the municipality was on the verge of bankruptcy, assisting refugees became more than a matter of humanitarian duty or pragmatic policy-making. Paradoxically as it may seem, it was also an economic opportunity. In this respect, the insights from this case study contribute to the debate on the dynamics of local migration policy-making in times of economic hardship (Schiller and Hackett Citation2018). More concretely, they demonstrate that a ‘hybrid combination’ between economic and humanitarian reasoning can lead to the adoption of local policies for forced migrants, reflecting similar dynamics in local diversity policies (Moutselos et al. Citation2018). Moreover, the example of Thessaloniki shows that, under certain circumstances, the development of local migration policies can become an innovative way to address the consequences of austerity measures (Overmans Citation2019). In this regard, it confirms the suggestion that reduced local policy activism in the field of migration is not necessarily the only possible outcome during an economic crisis (Caponio and Donatiello Citation2017).

Regarding the question of how a new city of arrival can succeed in developing local migration policies within a very restrictive institutional context, the analysis pinpoints the significance of building horizontal (with local and transnational partners at city level) and vertical coalitions (with UN agencies and international donor organisations). While the adhocracy broadened the space for discretion in refugee reception and integration, this space could not be ‘inhabited’ by the municipality without the funds, the human capital and the know-how acquired through Thessaloniki’s ‘double opening’ (Oomen et al. Citationforthcoming). Access to these pivotal resources enabled the local government to free itself from the ‘suffocating embrace’ of the state and to pursue its own policy objectives.

While the contribution of civil society and transnational municipal networks to local migration policy-making is well documented (Caponio Citation2018; Danış and Nazlı Citation2018), the decisive role of Thessaloniki’s vertical coalition in promoting its local policy approach points to a novelty in migration governance. More specifically, UN agencies have deliberately started to foster closer relationships with local authorities, seeking to promote their own policy agenda for a ‘coalition of the willing’ in the reception and integration of refugees (Ahouga Citation2018; United Nations General Assembly Citation2017). This prima facie innocent shift from ‘traditional’ UN intervention – namely through cooperation with national governments and NGOs – could potentially give new meaning to the ‘think globally, act locally’ slogan. Some authors have emphasised the need for the UN to reach out to new partners and ‘capitalize on new and emerging alliances with local and non-state actors’ (Thouez Citation2018, 13). Others have suggested the potential benefits of cooperation between local governments and the UNHCR in the field of refugee resettlement (Sabchev and Baumgärtel Citation2020). In brief, the potential win-win scenario of engaging in such vertical coalitions could represent an opportunity for both municipalities and the UN, as well as interested central governments, and therefore deserves further scholarly attention.

Finally, a brief reflection is needed on the use of the assemblage analytical approach and the process tracing technique in this research. To start with the former, the story of Thessaloniki illustrates the contemporary quest of many municipalities to address the challenges associated with immigration by forming ‘new and shifting constellations’ (Mayer Citation2018, 232). These constellations undergo continuous transformations; they assemble, disassemble and reassemble. Using an assemblage approach to investigate them as temporary configurations of heterogeneous elements activated by different actors and factors (Greenhalgh Citation2008, 12–13; Ureta Citation2015) provides a detailed understanding of the local policy-making process. While the multi-level governance approach (Caponio and Jones-Correa Citation2017) also recognises the importance of the horizontal and vertical dynamics underpinning local migration policies, its point of departure remains the policy itself, rather than the broader policy context. As for the relational approach that has recently gained popularity in migration policy research (Filomeno Citation2016, Citation2017), one cannot but acknowledge the fact that it shares a number of core characteristics with the assemblage approach (relational thinking, focus on conjunctural causation and processes, etc.). On the face of it, it seems that the assemblage perspective offers a more solid foundation for the development of concepts that adequately capture the complexity of migration governance (e.g. adhocracy). In any case, it is the future application of these two approaches that will clarify which one provides better assistance in dealing with the inevitable reductionism that (migration) policy research entails.

At the same time, adopting such an analytical angle goes hand in hand with embracing the complexity of migration governance and the associated methodological challenges. In this respect, this study demonstrates that process tracing can serve as a complementary tool to the assemblage approach. For example, its heuristic function and its ‘alertness’ to multiple causation made it possible to establish a link between the prolonged austerity in Greece, the widespread adhocracy, and the development of local reception and integration polices in Thessaloniki. Furthermore, the use of process tracing helped uncover the intentions behind the mayor’s decisions, highlighting not only the ‘what now’, but also the ‘why now’ of the policy-making process (Gale Citation1999, 403). In short, these advantages underline the importance of further exploring and harnessing the potential of the assemblage approach and process tracing in the field of migration policy research.

Conclusion

This article addressed the questions of why and how local governments develop reception and integration policies for forced migrants. In answering these questions, I focused on the ‘against all odds’ policy activism of the municipality of Thessaloniki, analysing it through the lens of an assemblage approach. My analysis underlines the importance of different actors and factors for the development of local policies for asylum seekers and refugees. More concretely, the insights derived from Thessaloniki’s case confirm the assumption that mayors play an important role in enacting local approaches to reception and integration, which may have different goals than national ones. However, the will and capacity of mayors to achieve their distinct policy objectives depend on a number of conjunctural factors and cannot be explicated in isolation. In this particular case, the loosening of the institutional constraints and the mobilisation of funds for the reception and integration of forced migrants – both directly related to the adhocracy configuration – facilitated Thessaloniki’s successful policy-making. In addition, the establishment of horizontal and vertical coalitions with local, transnational and international partners appears to be an effective strategy to increase the capacity of local governments to exploit their institutional leeway. Such coalitions can address internal municipal weaknesses by equipping the local level with funds, human capital and know-how. However, as the case of Thessaloniki demonstrates, the failure to convert such temporary partnerships into permanent municipal structures may undermine the long-term sustainability of local policy initiatives for the reception and integration of forced migrants.

Building on the findings of this research, I conclude with two suggestions for future inquiry. From a practical perspective, further research within and outside the Greek context may bring additional clarity regarding the potential of vertical coalitions to accelerate the development and implementation of local reception and integration policies for forced migrants. If UN organisations can successfully use their resources to build capacity in local governments based on a shared vision of effective migration and integration governance – which is not necessarily shared by the respective national authorities – then how does this process affect the dynamics between local and national government? Moreover, to what extent can the UN fulfil the ‘wingman’ function (Thouez Citation2018) in progressive municipal coalitions established by local governments, as in the case of the Cities for Integration network in Greece supported by the IOM and the UNHCR? At the same time, from an analytical point of view, the application of the dynamic concepts offered by the assemblage perspective should be further explored in migration policy research. This may prove particularly fruitful in deriving new insights on local migration policy activism, especially given the complexity that this field entails.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 I adopt a broader definition of local reception and integration policy, as the wide range of measures and practices of local governments which seek to regulate forced migrants’ access to services and facilitate their initial settlement and subsequent inclusion into the local community life. This definition corresponds to the way in which migration policy scholars (Filomeno Citation2016) and the Greek Ministry of Migration Policy (Citation2018, 10) have conceptualised migrant integration policies.

3 See https://www.react-thess.gr/.

References

- Ahouga, Y. 2018. “The Local Turn in Migration Management: The IOM and the Engagement of Local Authorities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (9): 1523–1540.

- Ambrosini, M. 2020. “The Local Governance of Immigration and Asylum: Policies of Exclusion as a Battleground.” In Migration, Borders and Citizenship: Between Policy and Public Spheres, edited by M. Ambrosini, M. Cinalli, and D. Jacobson, 195–215. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Anastasiadou, M., A. Marvakis, P. Mezidou, and M. Speer. 2017. From Transit Hub to Dead End: A Chronicle of Idomeni. Accessed September 21, 2018. http://bordermonitoring.eu/berichte/2017-Idomeni/.

- Arrival Cities. 2016. Manaing Global Flows at Local Level. Arival Cities Baseline Study. Accessed June 13, 2020. https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/arrival_cities_baseline_study.pdf.

- Bazurli, R. 2020. “How “Urban” Is Urban Policy Making?” PS: Political Science & Politics 53 (1): 25–28.

- Bennett, J. 2009. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Bennett, A., and J. Checkel, eds. 2014. Process Tracing. From a Metaphor to Analytic Tool. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Betts, A., F. Memişoğlu, and A. Ali. 2020. “What Difference Do Mayors Make? The Role of Municipal Authorities in Turkey and Lebanon’s Response to Syrian Refugees.” Journal of Refugee Studies, (Published online), doi:10.1093/jrs/feaa011.

- Caponio, T. 2018. “Immigrant Integration Beyond National Policies? Italian Cities’ Participation in European City Networks.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (12): 2053–2069.

- Caponio, T., and D. Donatiello. 2017. “Intercultural Policy in Times of Crisis: Theory and Practice in the Case of Turin, Italy.” Comparative Migration Studies 5 (1): 5–13.

- Caponio, T., and M. Jones-Correa. 2017. “Theorising Migration Policy in Multilevel States: The Multilevel Governance Perspective.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (12): 1–16.

- Cities Network for Integration. 2019. Kinwniki Synohi Mesa apo tin Entaxi: Yposhomenes Praktikes gia tin Entaxi toy Prosfygikou Plithysmou stin Ellada apo toys Dimoys toy “Diktiou Polewn gia tin Entaxi” [Social Cohesion Through Integration: Promising Practices for the Integration of the Refugee Population in Greece from the “Cities Network for Integration”]. Accessed June 5, 2020. https://www.accmr.gr/el/%CE%BD%CE%AD%CE%B1/799-%CE%BA%CE%B1%CE%BB%CE%AD%CF%82-%CF%80%CF%81%CE%B1%CE%BA%CF%84%CE%B9%CE%BA%CE%AD%CF%82-%CE%B4%CE%AF%CE%BA%CF%84%CF%85%CE%BF-%CF%80%CF%8C%CE%BB%CE%B5%CF%89%CE%BD.html?art=1.

- CNN Greece. 2016. “Thessaloniki: Agwnas Dromoy gia na mi Hreokopisi o Dimos [Thessaloniki: A Race to Avoid the Bankruptcy of the Municipality].” Accessed June 9, 2020. https://www.cnn.gr/news/ellada/story/17949/thessaloniki-agonas-dromoy-gia-na-mi-xreokopisei-o-dimos.

- Council of Europe. 2018. Greek Municipalities Participate in the First Intercultural Integration Academy. [Press release]. Accessed June 4, 2020. https://www.coe.int/en/web/interculturalcities/-/greek-municipalities-participate-in-the-first-intercultural-integration-academy.

- Danış, D., and D. Nazlı. 2018. “A Faithful Alliance Between the Civil Society and the State: Actors and Mechanisms of Accommodating Syrian Refugees in Istanbul.” International Migration 57 (2): 143–157.

- de Graauw, E., and F. Vermeulen. 2016. “Cities and the Politics of Immigrant Integration: A Comparison of Berlin, Amsterdam, New York City, and San Francisco.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (6): 989–1012.

- DeLanda, M. 2006. A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity. London: Continuum.

- Dicker, S. 2017. “Solidarity in the City: Platforms for Refugee Self-Support in Thessaloniki.” In Making Lives: Refugee Self-Reliance and Humanitarian Action in Cities, edited by J. Fiori, and A. Rigon, 73–103. London: Humanitarian Affairs Team, Save the Children.

- Doomernik, J., and D. Ardon. 2018. “The City as an Agent of Refugee Integration.” Urban Planning 3 (4): 91–100.

- Doomernik, J., and B. Glorius. 2016. “Refugee Migration and Local Demarcations: New Insight into European Localities.” Journal of Refugee Studies 29 (4): 429–439.

- Dunn, E. C. 2012. “The Chaos of Humanitarian Aid: Adhocracy in the Republic of Georgia.” Humanity: An International Journal of Human Rights, Humanitarianism, and Development 3 (1): 1–23.

- European Commission. 2015. Joint Declaration On the Support to Greece for the Development of the Hotspot/Relocation Scheme as well as for Developing Asylum Reception Capacity. [Press release]. Accessed June 9, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/STATEMENT_15_6309.

- European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. 2019. Update of the 2016 Opinion of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights on Fundamental Rights in the ‘Hotspots’ Set Up in Greece and Italy. Accessed July 8, 2020. https://fra.europa.eu/sites/default/files/fra_uploads/fra-2019-opinion-hotspots-update-03-2019_en.pdf.

- Filomeno, F. A. 2016. Theories of Local Immigration Policy. Cham: Springer.

- Filomeno, F. A. 2017. “The Migration–Development Nexus in Local Immigration Policy.” Urban Affairs Review 53 (1): 102–137.

- Gale, T. 1999. “Policy Trajectories: Treading the Discursive Path of Policy Analysis.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 20 (3): 393–407.

- Gebhardt, D. 2016. “When the State Takes Over: Civic Integration Programmes and the Role of Cities in Immigrant Integration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (5): 742–758.

- George, A. L., and A. Bennett. 2005. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Geuijen, K., C. Oliver, and R. Dekker. 2020. “Local Innovation in the Reception of Asylum Seekers in the Netherlands: Plan Einstein as an Example of Multi-Level and Multi-Sector Collaboration.” In Geographies of Asylum in Europe and the Role of European Localities, edited by B. Glorius and J. Doomernik, 245–260. Cham: Springer.

- Glorius, B., and J. Doomernik, eds. 2020. Geographies of Asylum in Europe and the Role of European Localities. Cham: Springer.

- Greek Ombudsman. 2017. Migration Flows and Refugee Protection. Administrative Challenges and Human Rights Issues. Accessed September 20, 2018. https://www.synigoros.gr/?i=human-rights.en.recentinterventions.434107.

- Greenhalgh, S. 2008. Just One Child: Science and Policy in Deng’s China. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hinger, Sophie, Philipp Schäfer, and Andreas Pott. 2016. “The Local Production of Asylum.” Journal of Refugee Studies 29 (4): 440–463.

- Hlepas, N., and P. Getimis. 2018. Dimosionomiki Exygiansi Stin Topiki Aytodiikisi. Provlimata kai Diexodi ypo Synthikes Krisis [Fiscal Consolidation in Local Self-Government. Problems and Solutions in a Crisis Context]. Athens: Papazisi.

- Howden, D., and A. Fotiadis. 2017. “The Refugee Archipelago: The Inside Story of What Went Wrong in Greece.” 6 March. Accessed June 16, 2020. https://www.newsdeeply.com/refugees/articles/2017/03/06/the-refugee-archipelago-the-inside-story-of-what-went-wrong-in-greece.

- Integrating Cities. 2017. Thessaloniki Received Support from Amsterdam and Zurich in the Framework of Solidarity Cities. [Press release]. Accessed June 4, 2020. http://www.integratingcities.eu/integrating-cities/news/Thessaloniki-received-support-from-Amsterdam-and-Zurich-in-the-framework-of-Solidarity-Cities-WSWE-AT7NYC.

- International Organisation for Migration. 2019. “Supporting the ‘Cities Network for Integration’.” Accessed June 5. https://greece.iom.int/en/supporting-%E2%80%98cities-network-integration%E2%80%99.

- Kandylis, G. 2019. “Accommodation As Displacement: Notes from Refugee Camps in Greece in 2016.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (Special Issue 1): i12–i21.

- Koulocheris, S. 2017. Integration of Refugees in Greece, Hungary and Italy. Annex 1: Country Case Study Greece. Accessed June 10, 2020. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/25f9deb3-196e-11e9-8d04-01aa75ed71a1/language-en.

- Lazopoulos, D. 2019. “Ita Mpoytari-Katapsifistike o Neos Organismos Eswterikis Ypiresias [Defeat for Boutaris - the New Internal Service Organisation Voted Down].” Makedonia, 8 February. Accessed June 9, 2020. https://www.makthes.gr/196270.

- Lohmueller, D. 2016. “Out of Sight, Out of Mind.” Accessed June 9, 2020. http://davidlohmueller.com/en/refugee-camps-greece/.

- Maniatis, G. 2018. “From a Crisis of Management to Humanitarian Crisis Management.” South Atlantic Quarterly 117 (4): 905–913.

- Mayer, M. 2018. “Cities As Sites of Refuge and Resistance.” European Urban and Regional Studies 25 (3): 232–249.

- Ministry of Migration Policy. 2018. Ethniki Stratigiki gia tin Entaxi [National Strategy for Integration]. Accessed June 26, 2020. http://www.opengov.gr/immigration/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2019/01/ethniki-stratigiki.pdf.

- Moutselos, Michalis, Christian Jacobs, Julia Martínez-Ariño, Maria Schiller, Karen Schönwälder, and Alexandre Tandé. 2018. “Economy or Justice? How Urban Actors Respond to Diversity.” Urban Affairs Review 56 (1): 228–253.

- Municipality of Thessaloniki. 2018a. Integrated Action Plan for Integration of Refugees. Accessed June 10, 2020. https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/media/iap_thessaloniki_arrival_cities.pdf.

- Municipality of Thessaloniki. 2018b. Municipal Council Decision Approving by Majoity the Signing of the Integrating Cities Charter of the Eurocities Network (In Greek). (1522/29-10-2018). Accessed June 4, 2020. https://diavgeia.gov.gr/doc/72%CE%A9%CE%A3%CE%A9%CE%A15-6%CE%9D8?inline=true.

- Municipality of Thessaloniki. 2019. Synenteyxi Typoy-Apologismos Thitias tis Diikisis toy Yianni Boutari [Press Conference - End-of-term of Yiannis Boutaris’ Administration] [Press release]. Accessed June 9, 2020. https://thessaloniki.gr/synentefxi-typou-apologismos-thitias-tis-dioikisis-tou-gianni-mpoutari/.

- Oomen, B., M. Baumgärtel, S. Miellet, E. Durmus, and T. Sabchev. forthcoming. “Strategies of Divergence: Local Authorities, Law and Discretionary Spaces in Migration Governance.” Journal of Refugee Studies.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2018. Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees in Athens. Accessed October 12, 2018. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/9789264304116-en.pdf?expires=1558027139&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=B068E725CF5D90F664B3DE4DADEF8F8E.

- Overmans, J. 2019. The Austerity Paradox: How Municipalities (Can) Innovatively Cope with Fiscal Stress. The Hague: Eleven international publishing.

- Poppelaars, C., and P. Scholten. 2008. “Two Worlds Apart.” Administration & Society 40 (4): 335–357.

- Regional Union of Municipalities of Central Macedonia Region. 2015. Letter to the Deputy Minister of Interior and Administrative Reorganisation Entitled ‘Addressing the Refugee-Migrant Problem’ (In Greek). (1438/17/ΤΠ/8-12-2015). Accessed March 6, 2020. http://www.ampelokipi-menemeni.gr/Portals/2/files/images/Press/2015-1438%20080215.pdf.

- Rhodes, R. A. 2007. “Understanding Governance: Ten Years On.” Organization Studies 28 (8): 1243–1264.

- Saad, H., and R. Essex. 2018. Arrival Cities: Final Dispatches. Accessed June 4, 2020. https://urbact.eu/sites/default/files/media/fianl_report_arrival_cities.pdf.

- Sabchev, T., and M. Baumgärtel. 2020. “The Path of Least Resistance?: EU Cities and Locally Organised Resettlement.” Forced Migration Review 63: 38–40.

- Savage, G. C. 2020. “What is Policy Assemblage?” Territory, Politics, Governance 8 (3): 319–335.

- Schiller, M., and S. Hackett. 2018. “Continuity and Change in Local Immigrant Policies in Times of Austerity.” Comparative Migration Studies 6 (1): 2. doi:10.1186/s40878-017-0067-x.

- Scholten, P., F. Baggerman, L. Dellouche, V. Kampen, J. Wolf, and R. Ypma. 2017. Policy Innovation in Refugee Integration? A Comparative Analysis of Innovative Policy Strategies Toward Refugee Integration in Europe. Accessed October 24, 2018. https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/binaries/rijksoverheid/documenten/rapporten/2017/11/03/innovatieve-beleidspraktijken-integratiebeleid/Policy+innovation+in+refugee+integration.pdf.

- Seawright, J., and J. Gerring. 2008. “Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research.” Political Research Quarterly 61 (2): 294–308.

- Sunata, U., and S. Tosun. 2019. “Assessing the Civil Society’s Role in Refugee Integration in Turkey: NGO-R As a New Typology.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (4): 683–703.

- Terlouw, A., and A. Böcker. 2019. “Mayors’ Discretion in Decisions About Rejected Asylum Seekers.” In Caught In Between Borders: Citizens, Migrants and Humans. Liber Amicorum in Honour of Prof. Dr. Elspeth Guild, edited by P. E. Minderhoud, S. A. Mantu, and K. M. Zwaan, 291–302. Tilburg: Wolf Legal Publishers.

- Thouez, C. 2018. “Strengthening Migration Governance: The UN as ‘Wingman’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (8): 1242–1257.

- Tilly, C. 1996. “Invisible Elbow.” Sociological Forum 11 (4): 589–601.

- United Nations General Assembly. 2017. Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary General on Migration. Accessed February 19, 2019. http://undocs.org/A/71/728.

- Ureta, S. 2015. Assembling Policy: Transantiago, Human Devices, and the Dream of a World-Class Society. Cambridge: Mit Press.

- Youdell, D. 2015. “Assemblage Theory and Education Policy Sociology.” In Education Policy and Contemporary Theory: Implications for Research, edited by K. N. Gulson, M. Clarke, and E. B. Petersen, 110–121. London: Routledge.

- Youdell, D., and I. McGimpsey. 2015. “Assembling, Disassembling and Reassembling ‘Youth Services’ in Austerity Britain.” Critical Studies in Education 56 (1): 116–130.

- Zapata-Barrero, Ricard, Tiziana Caponio, and Peter Scholten. 2017. “Theorizing the ‘Local Turn’ in a Multi-Level Governance Framework of Analysis: A Case Study in Immigrant Policies.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 83 (2): 241–246.

Appendix. List of interviews