?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The article examines the politicisation of immigration in Europe during the so-called migration crisis. Based on original media data, it traces politicisation during national election campaigns in 15 countries from the 2000s up to 2018. The study covers Northwestern (Austria, Britain, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, and Switzerland), Central-Eastern (Hungary, Poland, Latvia, and Romania), and Southern Europe (Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain). We proceed in three interrelated steps. First, we show that the migration crisis has accentuated long-term trends in the politicisation of immigration. The issue has been particularly salient and polarised in Northwestern Europe but also in the latest Italian, Hungarian, and Polish campaigns. Second, radical right parties are still the driving forces of politicisation. The results underscore that the radical right not only directly contributes to the politicisation of immigration but triggers other parties to emphasize the issue, too. Third, we observe a declining ‘marginal return’ of the migration crisis on the electoral support of the radical right, and we confirm previous studies by showing that an accommodating strategy by the centre-right contributes to the radical right’s success, provided the centre-right attributes increasing attention to immigration.

Introduction

As has been outlined in the introduction of the special issue (Hadj Abdou, Bale and Geddes Citation2022), the politicisation of migration did not begin with the migration crisis, but has a history that reaches back several decades. Conflicts over immigration are part and parcel of a new structuring divide in European societies and politics. Different labels are used to refer to the new cleavage – from ‘integration-demarcation’ (Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012), ‘universalism-communitarianism’ (Bornschier Citation2010), ‘cosmopolitanism-communitarianism’ (de Wilde et al. Citation2019), ‘cosmopolitanism-parochialism’ (de Vries Citation2018b) to the ‘transnational cleavage’ (Hooghe and Marks Citation2018). However, scholars agree that the cleavage concerns fundamental issues of rule and belonging and taps into various sources of conflict about national identity, sovereignty, and solidarity. This is why manifest conflicts about the influx and integration of migrants, but also about competing supranational sources of authority, and international economic competition play such a significant role in the restructuration process.

For multiple reasons – programmatic constraints, internal divisions or incumbency – the mobilisation potentials that were created by this new divide were initially neglected and avoided by mainstream parties (e.g. Hooghe and Marks Citation2018; Green-Pedersen Citation2012; Steenbergen and Scott Citation2004; de Vries and van de Wardt Citation2011; Sitter Citation2001). Consequently, voters turned to new parties with distinctive profiles for their articulation. Over the past few decades, it has mainly been parties of the radical right that have politicised concerns about further immigration and European integration and thus mobilised the heterogeneous set of the losers of globalization (Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012). These parties all endorse a xenophobic form of nationalism that can be called ‘nativist’ (Mudde Citation2007), claiming that states should be inhabited exclusively by members of the native group (the ‘nation’). Accordingly, the vote for the radical right is not a ‘pure’ protest vote (e.g. Kriesi and Schulte-Cloos Citation2020). By contrast, scholars have shown that it is above all an anti-immigration and, more recently, an Islamophobic vote (e.g. Abou-Chadi, Cohen, and Wagner Citation2022; Betz Citation2002; Fennema and Van Der Brug Citation2003; Ivarsflaten Citation2008; Kallis Citation2018; Oesch Citation2008).Footnote1 To some extent, it has also been a vote against European integration (e.g. Werts, Scheepers, and Lubbers Citation2013), the ‘twin issue’ of immigration, and, additionally, a vote against the cultural liberalism of the left which has increasingly shaped western societies (e.g. Ignazi Citation2003; Inglehart and Norris Citation2019).

If the politicisation of migration is embedded in a deeper conflict, crises like the so-called migration crisis are still critical moments in the restructuration process of European party competition that may serve as catalysts for the politicisation of this underlying conflict. As Van Middelaar (Citation2016) aptly stated, crises are ‘moments of truth’, and in crises we are experiencing a ‘return of politics.’ In the present paper, we shall study whether and to what extent the migration crisis has indeed accentuated the long-term trends in the politicisation of immigration and the radical right’s capacity to fuel and profit from this process. Specifically, we answer three interrelated questions: First, to what extent does the migration crisis constitute yet another peak in the politicisation of immigration in Europe? Second, is the radical right still the driving force of politicisation? Finally, to what extent has the radical right profited electorally from the migration crisis and the strategies of its centre-right competitors?

Methodologically, we rely on a large-scale relational content analysis of newspaper coverage during national election campaigns. Based on the PolDem election dataset (Kriesi et al. Citation2020), we cover campaigns in 15 European countries from the early 2000s up to 2018. Our results show that the election campaigns since the onset of the 2015 crisis have seen extremely high levels of politicisation with the radical right still shaping debates in a distinctive and salient anti-immigration direction. At the same time, our analysis of electoral outcomes suggests a declining ‘marginal return’ of the migration crisis on the electoral success of the radical right; in particular, the radical right upstarts have benefited from the crisis, while established radical right parties have only marginally ‘profited’ from increasing numbers of asylum-seekers. Moreover, our findings confirm that an accommodative strategy of its main centre-right competitor boosts the electoral performance of the radical right. However, the radical right tends to benefit from such directional shifts only if the centre-right also emphasizes immigration issues more strongly. These are important findings against the background of a mainstreaming of radical right positions during the last decades (Mudde Citation2019). They provide a comparative benchmark for the country case studies in this special issue, which explore in detail the varying strategies of centre-right parties in responding to their radical competitors during crises.

Theoretical framework

The literature has developed a broadly held understanding of the concept of politicisation. Zürn (Citation2019, 978) suggests that it can be generally defined as ‘moving something into the realm of public choice’, while Hutter and Grande (Citation2014, 1003) define politicisation ‘as an expansion of the scope of conflict within the political system.’ In operational terms, a consensus is emerging regarding the components of what we mean by the term ‘politicisation’ (e.g. de Wilde, Leupold, and Schmidtke Citation2016; Hoeglinger Citation2016; Hutter and Grande Citation2014; Rauh Citation2016; Statham and Trenz Citation2013). These concepts have mainly been used in the study of the politicisation of European integration, but analogous concepts are also increasingly used in the study of the politicisation of immigration (see Van der Brug et al. Citation2016; Grande, Schwarzbörzl, and Fatke Citation2018).

Accordingly, we should distinguish between three conceptual dimensions which jointly operationalise the term: issue salience (visibility), actor expansion (range) and actor polarisation (intensity and direction). For this study, we do not consider actor expansion and conceptualise systemic politicisation as the product of salience and polarisation of the immigration-specific public discourse of political parties. In other words, we adhere to a definition that privileges public discourse and the supply side. We conceptually distinguish politicisation from related dynamics in public opinion and individual political behaviour (but see de Vries Citation2018a; Hurrelmann, Gora, and Wagner Citation2015). Broadly, politicisation of specific issues like immigration conceived in these terms is a function of national party competition. This competition, in turn, is shaped by long-term structural developments, critical moments like the migration crisis, and by the strategies of the parties involved (Hobolt and de Vries Citation2015). We take up these factors one by one, with a focus on the role of the radical right. In turn, we also consider arguably the most important impact of the politicisation of immigration – its impact on the electoral success of this party family.

Long-term structural change, the migration crisis, and the politicisation of immigration

With regard to the long-term factors and the recent migration crisis, we suggest that it makes sense to reduce the complexity by emphasizing broad differences that exist with respect to the impact of the new structuring divide between three large European regions – Northwestern Europe (NWE), Southern Europe (SE), and Central- and Eastern Europe (CEE). Moreover, we situate the impact of the migration crisis within the multiple crises Europe has faced since the onset of the Great Recession in 2008 (for a more detailed discussion, see Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019).

The new cleavage has had the greatest impact on party politics in NWE, with the transformation of party competition dating back at least as far back as the early 1980s when radical right parties began to gain ground in this part of Europe. They have become a critical force in the national party systems of Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands, Norway, and Switzerland already around the turn of the century. In other North-Western European countries – Finland, Germany, Sweden, and the UK – they have, for various reasons, broken through only during the more recent crises. While the Eurozone crisis did not have a great impact on party competition in these countries, we expect the migration crisis to have ‘hit’ the countries in NWE more forcefully and, therefore, to have enhanced the long-term trends towards the politicisation of immigration. In this part of Europe, we expect that it is the migration crisis which served to link the twin issues of European integration and immigration in a particularly explosive way. A study by Gessler and Hunger (Citation2019) confirms this hunch for Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

In SE, the impact of the new cleavage has been more limited – for reasons that have to do with the countries’ political legacy (long-lasting authoritarian regimes and strong communist parties, i.e. a strong ‘old’ left) as well as the fact that they had been emigration countries until more recently.Footnote2 However, under the impact of the combined economic and political crises that shook Southern Europe during the Great Recession, new parties of the radical left have surged in Greece, Spain and (to a more limited extent) in Portugal, while Italy has seen the rise of a movement-party (M5S) which declared itself to be ‘neither left, nor right’. The rise of these parties has substantially transformed the respective party systems (see Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019; Morlino and Raniolo Citation2017). We expect the impact of the Euro crisis on party competition to be compounded by the migration crisis in Greece and Italy, the two countries which have been strongly affected by the arrival of refugees across the Mediterranean. In these countries we expect a strong increase in the politicisation of immigration by a resurging radical right during the migration crisis, in line with the new structuring conflict in NWE.

In CEE, political conflict has been characterised by the absence of clear-cut cleavages. The Communist inheritance left a fragmented society and an unstructured pattern of political conflict. When measured against the four criteria of institutionalisation introduced by Mainwaring and Scully (Citation1995), the party systems in CEE still appear poorly institutionalised. They have not (yet) developed stable roots in society, are barely considered legitimate by the citizens of their countries, their organisations tend to be unstable, and they are characterised by extraordinarily high volatility (e.g. Powell and Tucker Citation2014). To the extent that there is structuration of conflict, the empirical findings suggest that it is connected to cultural issues (e.g. Coman Citation2017; Eihmanis Citation2019; Gessler and Kyriazi Citation2019; Salek and Sztajdel Citation2019). The common denominator of the cultural issues mobilising the conservative side of the CEE electorates seems to be a defensive nationalism asserting itself against internal enemies (such as ethnic minorities, Roma, and Jews) and external ones (such as foreign corporations colonising the national economy).

During the Great Recession, the lack of institutionalisation facilitated the rise ofright-wing populists in this part of Europe, most conspicuously in the Visegrad countries (Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Slovakia). Given the significantly less structured nature of party competition in CEE and the contradictory political incentives, strategically acting political entrepreneurs like Victor Orban and Jaroslaw Kaczynski have had ample maneuvering space for the mobilisation of conservative and nationalist attitudes (Enyedi Citation2005). Although they remained directly largely unaffected by the migration crisis in the sense of being so-called ‘destination countries’, these parties were concerned by the attempts of European agencies and Western European countries to relocate refugees across Europe. These attempts were exploited by national-conservative and populist governments. Their opposition to the relocation of refugees is likely to have fueled the politicisation of immigration and defensive nationalism in CEE.

The radical right’s contagious strategy in politicising immigration

Such structural potentials need to be politically mobilised and articulated by political actors. That is, certain actors need to visibly defend distinct positions in the public debate to activate the latent conflicts. As argued in the introduction, the politicisation of opposition to immigration has been the core business of radical right parties, which in turn have often been called anti-immigration parties. These parties both express and fuel opposition to immigration, which is most closely related to their core nativist concerns. Accordingly, Grande, Schwarzbörzl, and Fatke (Citation2018) show for 44 national election campaigns in six NWE countries (Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the UK) that the issue entrepreneurship of radical right parties plays a crucial role in the politicisation of the immigration issue. Gessler and Hunger (Citation2019) confirm the still crucial role of radical right parties for the politicisation of immigration during the migration crisis in the three NWE countries covered by their study. The question is whether this applies to other countries as well.

In addition to the radical right, other parties may have picked up the issue of immigration in their electoral campaigns, in part at least galvanised by the successful politicisation of the issue by the radical right. In this regard, the literature is ambiguous: part of it specifies that increasing radical right support/success induces mainstream parties to increasingly emphasize the immigration issue (salience contagion), while another part suggests that it also encourages them to shift toward anti-immigration positions (position contagion) (Abou-Chadi Citation2016). The later process indicates what scholars have called a ‘mainstreaming’ of the previously distinct stances adopted by the radical right (Mudde Citation2019). Another hypothesis argues that, in both respects, the centre-left is less affected by radical-right support/success than the centre-right. The positional shift of the centre-right in reaction to radical-right electoral success has been amply confirmed for Northwestern European party systems (e.g. Van Spanje Citation2010; Han Citation2015; Abou-Chadi Citation2016). Except for the study by Gessler and Hunger (Citation2019) none of these analyses covers the period of the migration crisis, however. Gessler and Hunger’s study shows that, in a situation such as the migration crisis, ignoring the immigration issue, especially for mainstream parties, was hardly an option. Most importantly, mainstream parties not only reacted to the crisis as such, but also to the radical right parties’ emphasis on immigration and did so within days and weeks. Salience contagion, which is already present before the crisis, thus seems to have been intensified during the crisis but diminished again in the post-crisis period. Regarding position contagion, the study finds few shifts, however.

Based on these ideas, we will analyze the politicisation of immigration by the radical right’s competitors as a function of the politicisation of the issue by the radical right during election campaigns. We expect that the radical right’s competitors will react to its politicisation of the immigration issue and politicisethe issue as well. In line with previous results, we expect them above all to increase the salience of the issue and to accommodate, to a more limited extent, their position to the anti-immigration position of the radical right. We expect such an effect especially for centre-right parties and during the migration crisis.

Weanalyze the driving role of the radical right for the politicisation of the immigration issue as well as the expectations concerning the strategic choices of the mainstream parties from left and right based on data about electoral debates. While such data focus on elections and do not allow for following the party discourse continuously, they have the advantage of mirroring the parties’ issue emphasis and positioning at a crucial moment of party competition.

The politicisation of immigration and the electoral success of the radical right

While we expect the radical right to contribute to the politicisation of the immigration issue in a decisive way, we also expect, in turn, that the electoral success of the radical right is decisively shaped by the politicisation of the issue in the electoral competition. Anti-immigration parties are known to benefit from the high salience of the immigration issue (e.g. Arzheimer Citation2018; Arzheimer and Carter Citation2006; Bale Citation2003). If the salience of the issue increases, as in the migration crisis, the radical right is likely to benefit as well. However, we would like to suggest that the salience of the issue in the public (which is particularly high in a crisis like the migration crisis) has a declining marginal return on the success of the radical right: it is above all the radical right upstarts which are likely to benefit from the crisis, while established radical right parties will already have largely exhausted their electoral potential and are expected to benefit only marginally from the increased salience of the issue during the migration crisis. Other parties may contribute to the salience of immigration, too, but it appears that a ‘dismissive’ strategy that keeps its salience low is most effective for the competitors of the radical right (Meguid Citation2005, 350).

Regarding the positioning of the competitors on the immigration issue, the results in the scholarly literature are more mixed: in line with standard spatial theory, van der Brug, Fennema, and Tillie (Citation2005, 561) find that radical right parties are more successful if the largest mainstream competitor occupies a centrist position than when it is leaning more clearly toward the right. Note, however, that this study does not explicitly consider the parties’ positioning with regard to immigration, but relies on their positioning on the left-right scale. By contrast, Bale (Citation2003) has argued that by adopting some of the positions of the radical right on immigration, i.e. by adopting what Meguid (Citation2005) called an ‘accommodating’ strategy, the centre-right might legitimize them and contribute to the radical right’s success. Indeed, Dahlström and Sundell’s (Citation2012) study of Swedish municipalities, for example, finds that a tougher stance on immigration of the mainstream parties is correlated with radical right success. Importantly, however, in this particular case, it is only when the entire mainstream is tough on immigration that the radical right benefits, and the toughness of the parties on the left seems to be more legitimising than that of the parties on the right.

Following our focus on public debates, we would like to suggest that the emphasis which the main centre-right competitor of the radical right puts on immigration and its positioning on the issue interact. If the centre-right competitor does not publicly mobilise on this issue, its positioning may be largely irrelevant for the radical right’s success. Only when immigration becomes a salient issue in the centre-right’s electoral campaign is its position likely to matter for the radical right’s success. Given the previously ambiguous results, it is an open question whether an adversarial (pro-immigration) or an accommodating (anti-immigration) position will increase the radical right’s electoral success, i.e. whether the niche-effect or the legitimising effect will be more important.

To sum up, we test three sets of expectations in this article. First, consider the impact of the migration crisis on the politicisation of immigration at the systemic level. We expect positive but region-specific effects given long-term differences in the structuration of political conflict and the differing crises experienced since the Great Recession. Second, we reconsider the status of the radical right as driving politicisation in times of crisis – it is expected to do so by directly contributing to the politicisation of immigration and by triggering its competitors to emphasize the issue as well. Finally, we focus on the conditions of the electoral success of the radical right, expecting a declining marginal return and an interaction effect between the centre-right’s shifts in issue emphasis and positioning.

Design and methods

We analyse debates during national election campaigns – as heightened moments of domestic conflict – in 15 countries. Specifically, we rely on the PolDem national elections dataset by Kriesi et al. (Citation2020).Footnote3 Six countries represent NWE (Austria, France, Germany, Ireland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the UK), and four each SE (Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain) and CEE (Hungary, Latvia, Poland, and Romania). For each country, we include at least one election campaign in the analysis before the onset of the Great Recession in the fall of 2008 and all the elections campaigns up to the end of 2018 (the Latvian election 2018 is not included yet). All in all, we cover 61 elections (Appendix A). As argued before, we consider the regional groupings as a helpful heuristic tool but provide empirical evidence on how far they carry us.

We follow our previous strategy and make use of a relational content analysis of newspaper articles to study politicisation (see Kriesi et al. Citation2008, Citation2012). While mass-mediated communication is not the only way to study politicisation, we consider it a kind of ‘master arena’ to observe statements in the public sphere. The analysis is based on the coding of two newspapers per country (Appendix A). We selected articles that report on the campaign and national party politics in general during the two months preceding Election Day. We then coded a sample of articles using core sentence analysis. That means each grammatical sentence is reduced to its most basic ‘core sentence(s)’ structure, which contain(s) only the subject, the object, and the direction of the relationship between the two. For the following analysis, we rely on all coded relations between party-affiliated actors as subject and any political issue as object. The analysis is based on around 100,000 such actor-issue statements.

A crucial step is aggregating the detailed issues that were coded into a set of broader categories. Ultimately, we grouped them into 17 categories (Appendix A). The issues were recoded so that positive directions indicate support for and negative directions opposition to immigration. The issue of immigration covers debates over access rights (who can enter?) and integration (what are the rights and duties of migrants and host societies?).

Empirical results

Systemic politicisation of immigration

The data analysis mirrors our expectations and proceeds in three steps. At first, we examine how politicisation developed at the systemic level. As pointed out, we measure politicisation at the systemic level as the multiplication of salience and polarisation. Regarding the two indicators, systemic salience is measured by the share of core sentences related to a given issue in percent of all statements. The indicator for the polarisation of positions is based on Taylor and Herman’s index of left-right polarisation, ranging from 0 to 1 (Appendix A).

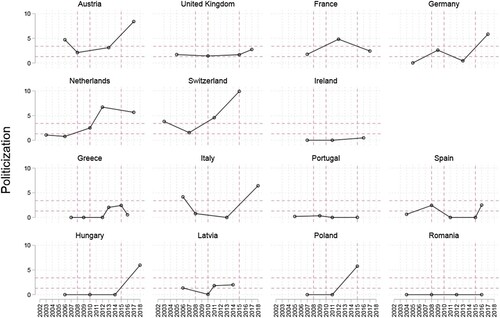

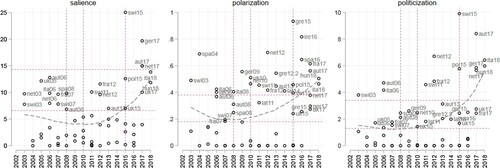

presents the development of the systemic salience, polarisation, and politicisation of immigration by election. The vertical lines indicate the start of the financial crisis (2008), of the Euro crisis (2010) and of the migration crisis (2015). For the interpretation, we also added two benchmarks: the two horizontal dashed lines indicate the mean (lower line) and the mean plus one standard deviation (upper line) of politicisation calculated for all 17 issue categories. Note that issues that cross the upper line are usually among the top-3 issues in a campaign.

Figure 1. Salience, polarisation, and politicisation of immigration by election.

Note: The figures show the salience, polarisation, and politicisation (salience X polarisation) of immigration by campaign. The trends are based on locally weighted smoothing (LOWESS). The horizontal dashed lines serve as benchmarks, indicating the mean and mean + std. dev. values across 17 issue categories (see Appendix B). The vertical dashed lines indicate the start of the financial crisis in 2008, the Euro crisis in 2010, and the refuges crisis in 2015.

The first graph in highlights that immigration was not a very salient issue in any of the campaigns leading up to the migration crisis. It reached above average salience especially in Austrian (2006, 2013), Dutch (2003, 2012), French (2007, 2012) and Swiss (2003, 2007, 2011) elections, i.e. countries where the radical right was already well established. Exceptionally, immigration assumed above average salience in the UK (2005), Italy (2006) and Spain (2008). The trend line for all countries remains below the ‘lower’ benchmark up to the migration crisis. In line with expectations, the salience of immigration has increased since the beginning of the migration crisis in 2015. What is more, immigration became highly polarised since 2015. Immigration had always been a highly polarising issue, as is indicated by the fact that, in the case of polarisation, the trend line always stayed above the mean. Since the beginning of the Eurozone crisis, however, immigration has become increasingly polarised and, since the migration crisis, it has become one of the most polarised issues (as indicated by the trend line and the many campaigns above the ‘upper’ benchmark in the second graph in ). The last graph in shows our summary measure of politicisation (salience x polarisation). It mirrors the combined trend for salience and polarisation. In a nutshell, since the migration crisis, immigration has become one of the most politicising issues, with extreme values not only for the last Austrian (2017), German (2017), Dutch (2017), and Swiss (2015) elections, but also for the last Hungarian (2018), Polish (2015), and Italian (2018) elections.

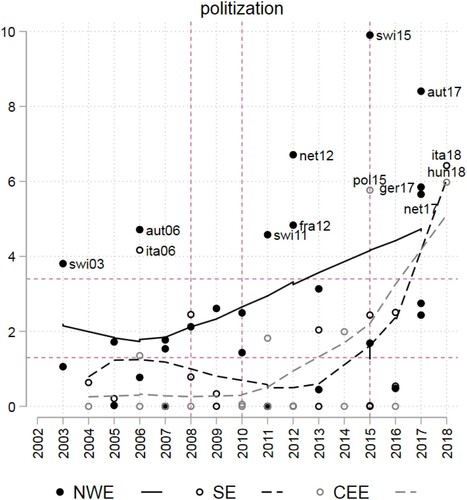

, which presents the trend lines for the three European regions separately, confirms that the increase in the politicisation of immigration extends to all three regions. After the beginning of the migration crisis, immigration has become a highly politicising issue across Europe. The increase of the politicisation of immigration has been more marked in Southern and Eastern than in Northwestern Europe, where the level of politicisation of immigration had already been above the mean throughout the 2000s.

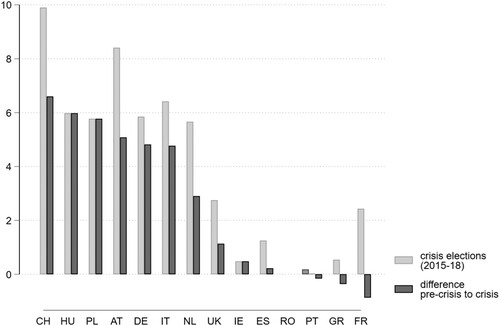

To put the impact of the migration crisis into a comparative perspective, presents the country-specific levels of politicisation since the onset of the crisis in 2015 as well as the difference to the pre-crisis campaigns. The countries are ordered according to the difference between pre- and crisis-levels. More details are presented in Appendix B which shows the trends by country. As indicates, in NWE, immigration has become more politicised during the migration crisis in Austria, the Netherlands, and Switzerland – three countries where the radical right had already been established long before the crisis and which were all more or less affected by the crisis. Immigration has also become more politicised in Germany, where the migration crisis had a particularly strong political impact and was the catalyst for the rise and radicalisation of the AfD (Arzheimer and Berning Citation2019). By contrast, the crisis had no perceptible impact in France, where economic issues dominated the 2017 elections and, except for the Front National (FN), neither European integration nor immigration constituted a major issue during the campaign (Kriesi Citation2018). Similarly, immigration was not politicised in Ireland during the migration crisis, and only to a limited extent in the UK, both non-members of the Schengen area and only marginally touched by the crisis. In SE, it is above all Italy where the crisis had a strong impact on the politicisation of immigration. Spain shows some impact, but Portugal has not been affected at all. In the 2015 Greek elections, the issue of European integration (and the bailout) has pretty much crowded out all other issues, including immigration, although Greece was, together with Italy, the hardest hit port-of-entry country at the time of the 2015 September elections. In CEE, Hungary and Poland are the two countries where the migration crisis politicised the immigration issue for the first time and to a large extent, while it had no impact on the 2018 election campaign in Romania according to our data.

The cross-country variation regarding the impact of the migration crisis illustrates two important points: first, the impact of this crisis is neither a necessary, nor a sufficient condition for the politicisation of immigration. While it is true that major destination and transit countries like Austria, Germany, Hungary and Italy have experienced a heavy politicisation of immigration, another strongly affected country like Greece did not do so. Also, countries that experienced less of a ‘hit’ (the Netherlands and Switzerland) or were rather by-stander countries (Poland) did so nevertheless. This, secondly, points to the crucial importance of partisan mobilisation for the politicisation of the immigration issue.

The drivers of politicisation: partisan divides over immigration

We now turn to the level of parties to examine the actors most strongly associated with opposition to or support for immigration in public debates. To identify the crucial actors involved in politicising immigration, we use the product of the salience a party attributes to immigration with the distinctiveness of its immigration position (which can be either distinctively anti- or pro-immigration). This conceptualisation not only parallels our conceptualisation at the systemic level, it is also analogous to Hobolt and de Vries’s (Citation2015, 1169) conceptualisation of issue entrepreneurship. There is, however, an important difference between the concept of politicisation at the systemic and what we measure on the party level: while the systemic level concept is not directed (both polarisation and salience can assume only positive values), the party level concept is (because of the distinctiveness of the party’s position on immigration). Based on this indicator, we identify the parties which shape public debates with salient and distinct immigration positions. This ‘politicizing party’ measure constitutes the dependent variable in a series of Prais-Winsten (for levels) and OLS (for change) regression models with robust standard errors.

To assess the politicising power of the radical right vis-à-vis its main competitors, we categorise the parties into four major groups: radical leftFootnote4, centre-left (including greens, social democrats and social liberals)Footnote5, centre-right (including Christian democrats, conservatives, conservative liberals), and radical right.Footnote6 In addition, we control for government participation at the time of the vote and party size as we expect these aspects to critically shape the ability of an individual party to politicise an issue in public debates. We also include a dummy for the elections during the migration crisis, as well as an interaction between this dummy and the party groups, to test whether the crisis made any difference for which parties most strongly politized immigration. Finally, we add a measure for the strategy adopted by the radical right to the analysis of the behaviour of the other party groups. This measure corresponds to the politicisation of immigration by the radical right, weighted by the electoral strenght of the radical right in the election in question. The idea is that the other parties react immediately to the radical right in an election campaign and that they are likely to do so to the extent that the radical right is an important competitor, as indicated by its anticipated success in these elections.Footnote7

presents the results in five models with our ‘politicizing party’ measure as the dependent variable. The first two models refer to all the parties, the last three exclude the radical right. The predictors in Model 1 include the party groups (with the radical left as the reference category), incumbency and party size. Model 2 adds the interactions between party groups and the migration crisis. The remaining three models concern the impact of the radical right on the role played by its competitors. Model 3 adds only the indicator for the radical right’s politicisation score to Model 1, Model 4 adds the same indicator in interaction with the party groups, and Model 5 adds these indicators to Model 2.

Table 1. The impact of party characteristics and the migration crisis on the ‘politicizing party’ score.

First, in Model 1, we find the expected differences between the broad party groups: both the radical left (reference group) and the centre-left politicise the issue in a pro-immigration direction.Footnote8 By contrast, the radical right is confirmed as the prime mover of anti-immigration politicisation. It contributes to the politicisation of immigration in general, independently of the specific politicising context of a given election. The centre-right is also generally mobilising against immigration, but to a lesser extent than the radical right. Incumbents are no different from opposition parties in this respect, but larger parties tend to mobilise a more anti-immigration position. Secondly, as shown by Model 2, the migration crisis did not make much of a difference regarding who is shaping public debates on immigration and in what way. It slightly increased the visibly pro-immigration stances of the centre-left, but otherwise it does not seem to have had much of an impact on the politicisation scores by the different parties. Note that party size no longer has any effect once we control for the migration crisis.

Turning to the impact of the radical right’s politicisation of immigration on the strategies of the other parties, Model 3 shows a strong negative effect. Since the radical right opposes immigration, this means that it generally incites the other parties to politicise the issue in a pro-immigration direction. Model 4 specifies that this effect applies above all to the parties on the left, while the overall effect on the centre-right is close to zero (-.009 + .008 = .001). The centre-right tends to generally politicise against immigration, independently of the mobilisation by the radical right.Footnote9 Once we control for these effects of the radical right on the other parties’ strategies, Model 5 suggests that the crisis has had a slightly stronger impact on the left: the politicisation score of the radical left becomes a bit more negative and that of the centre-left a bit more positive.

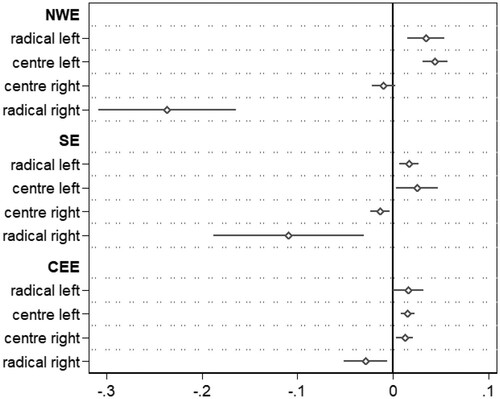

presents the effects for the party groups in the three European macro-regions (based on Model 1). As is immediately apparent, the radical right has been politicising immigration most in the region where it is most established, i.e. in NWE, while it has not done so consistently in CEE, where the party systems are least structured. SE takes an intermediary position in this respect. Compared to the strong effects for the radical right, all the other effects are rather limited. While the left consistently mobilises in favour of immigration across Europe, the results for the centre-right vary according to the region.

Figure 4. Marginal effects of the ‘politicizing party’ score by region and party group.

Note: The figure shows the marginal effects of party-level politicisation from a two-way interaction of region and party group. Confidence interval levels 84.4% (i.e. if C.I. do not overlap it means that there is a significant change at α = 0.05).

presents the impact of the party groups and of the radical right’s strategy on the salience and direction of immigration for the various parties. It replicates Models 1 and 5 for the two components separately. As Model 1 shows, the radical right contributes to the politicisation of immigration by both increasing the salience of the issue in the electoral campaigns and by mobilising against immigration. The same applies to the centre-right, albeit to a more limited extent. Model 5 shows the impact of the politicisation by the radical right on its competitors. If the radical right politicises the issue, our results suggest that it clearly increases the salience of immigration among all the other parties, but it only has a limited impact on the direction in which they politicise immigration. The effect on salience turns out to be enhanced during the migration crisis. The absence of any effect of the politicisation of immigration by the radical right on positional shifts of the mainstream parties is at variance with results of Abou-Chadi (Citation2016), who found such shifts among mainstream parties in reaction to radical right parties’ electoral success, in addition to increases in salience. The difference may have several explanations:the two studies differ with regard to the data – Abou-Chadi uses CMP data, which do not have a direct measure for immigration, but use a proxy (‘multiculturalism’) instead –, and he studies a different trigger for the reactions of mainstream parties – the radical right’s electoral success.

Table 2. The impact of party characteristics and the migration crisis on party-level salience of and position on immigration.

The electoral success of the radical right

Finally, we turn to the question of whether the radical right still profited electorally from heightened conflict over immigration. For the analysis of the electoral success of the radical right, we treat each election where the radical right participated as a unit of analysis. Our dependent variable is the change in the vote share of the radical right from the previous to the current election. We control for the radical right’s vote share in the previous elections. We proceed in two steps. First, we analyze the impact of the inflow of refugees on the radical right vote. As we have argued, the radical right’s electoral success is likely to be a function of migration flows during thecrisis. We measure the inflow of refugees by the maximum yearly number of refugees over the three years preceding the election (including the election year).Footnote10 We introduce this variable also in interaction with the radical right’s previous success to check whether the inflow of refugees has declining marginal returns for the radical right. All the other country differences are controlled for by country fixed effects.

Model 1 in presents the corresponding results. While these results should not be overinterpreted given the small number of cases, they nevertheless suggest that the radical right’s electoral success is strongly increased by the inflow of refugees, but the marginal returns of the crisis for the radical right are, indeed, decreasing: the more established parties of the radical right have been benefiting from the migration crisis much less than new radical right upstarts. The paradigmatic case for such an upstart i the German AfD, while the paradigmatic case of an already established radical right party, which benefited less from the migration crisis, would be the Swiss People’s Party SVP.

Table 3. Change in radical right success as a function of refugee numbers and changes in centre-right salience of and position on immigration.

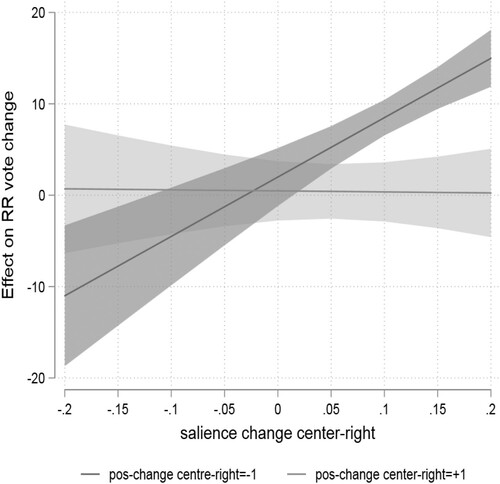

In the second step, we test the effect of the strategy of the most important centre-right party on the radical right’s success. For this test we keep the two strategic components – shifts in salience and positioning – separate. Models 2 and 3 in present the results. Model 2, which includes only the direct effects of the two components, indicates a statistically significant effect for changes in the salience of the immigration issue in the main centre-right party’s electoral campaign on the radical right’s success, but no effect for changes in its positioning on immigration. As expected, the more attention the mainstream centre-right party pays to immigration in its electoral campaign, the greater the success of its radical right competitor.

But, as shown by Model 3, there is also an important interaction effect between changes in salience and changes in the positioning of the centre-right party on the immigration issue. illustrates this interaction. It clarifies that our results support claims that an accommodating and not an adversarial strategy of the mainstream centre-right party contributes to the radical right’s electoral success, provided the centre-right party’s campaign attributes increasing attention to immigration. If the main competitor on the right-side of the political spectrum does not pay increasing attention to immigration, its publicly visible position shifts, whether accommodating or adversarial, tend to have no effect on the radical right’s success. However, if the centre-right competitor starts to pay a lot of attention to immigration and takes a stance similar to the radical right, then it contributes to the radical right’s success. This result supports the legitimising effect of an accommodating strategy of the centre-right, and vindicates Jean-Marie Le Pen’s adage that ‘the French choose the original, not the copy’.

Conclusion

In this article, we have presented results on three interrelated questions about the impact of the migration crisis on long-term trends in the politicisation of immigration and the radical right’s capacity in fuelling and profiting from moments of heightened conflict in the electoral arena. First, we analysed the extent to which migration has been politicised in national election campaigns in 15 European countries from the early 2000s up to 2018. Our results indicate that the immigration issue has only exceptionally been one of the key issues in the national electoral campaigns before the advent of the migration crisis. However, with the onset of the migration crisis, immigration has been heavily politicised across Europe. Nevertheless, we found country-specific variations in this respect, which suggest that this crisis is neither a necessary, nor a sufficient condition for the politicisation of immigration. Moreover, our results point to the crucial importance of partisan mobilisation and inter-party competition for the politicisation of immigration, which are analysed in detail in the country cases studies in this special issue (see Hadj Abdou, Bale and Geddes Citation2022). Importantly, the expected macro-regional differences in the level of politicisation are less pronounced for the immigration issue than for the politicisation of European integration (Hutter and Kriesi Citation2019).

Second, our results confirm previous studies regarding the crucial role of radical right parties for the politicisation of immigration. Radical right parties are important driving forces because they directly contribute to the politicisation of the issue and because they trigger other parties to engage with the issue as well. The centre-right is also generally mobilising against immigration, but to a lesser extent than the radical right. Specifically, the radical right’s mobilisation increases the salience of immigration among all the other parties during election campaigns, but it hardly has an impact on the direction in which they politicise immigration. Additionally, this kind of salience contagion has been amplified during the migration crisis, but no similarly systematic and strong trends can be observed for the positions adopted by the radical right’s competitors. Focusing on average effects across a larger set of countries, the migration crisis has hardly changed or reinforced this general pattern.

Third, with respect to the success of the radical right, our results indicate that success is strongly enhanced by preceding inflows of refugees. However, the ‘marginal returns’ of the crisis for the radical right are decreasing: the more established parties on the radical right have been benefiting under the condition of such inflows much less than new radical right upstarts. This result indicates a ceiling effect as many established radical right parties in Europe may have fully exploited their electoral potential, being only able to gain further under exceptionally favourable institutional and discursive conditions. Regarding the latter, our findings highlight once again that the success of the radical right is also related to the publicly visible strategy of its main competitor, the mainstream centre-right party. The literature is ambiguous about which type of strategy by this competitor is most conducive to the radical right’s success. Our findings suggest that it is an accommodating and not an adversarial strategy of the mainstream centre-right party that contributes to the radical right’s success, provided the centre-right party’s own campaign attributes increasing attention to immigration. This result confirms the legitimising effect of the centre-right’s accommodating strategy.

Our study has been largely supportive of previous results about the politicisation of immigration. The only exception is that we hardly found any indication of systematic positional shifts among mainstream parties in reaction to the politicisation of immigration by the radical rightin election campaigns, while Abou-Chadi (Citation2016) found such shifts in reaction to radical right electoral success. Otherwise, we largely support received wisdom, although the various studies used different data (media data vs. manifesto or expert survey data), different types of concepts (politicisation vs salience), different types of country selections (our results are based on a selection of 15 countries, covering all three European macro regions, vs data sets covering only west European countries), and different types of designs for the analysis (e.g. conventional regression designs vs. regression discontinuity designs). Importantly, however, we add to the received wisdom by our finding that the migration crisis 2015/16 tends to have not modified the basic parameters and dynamics of the politicisation of immigration in election campaigns, but it has greatly increased the level of politicisation of the issue in such campaigns.

Acknowledgments

We have presented earlier versions of the manuscript at workshops in Berlin and Florence. We would like to thank the participants of these workshops, the guest editors, and the reviewers for their very helpful feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For recent overviews of the burgeoning literature on electoral support for radical right parties, see Arzheimer (Citation2018) and Stockemer, Lentz, and Mayer (Citation2018).

2 Compared to the electoral results in NWE, radical right parties have not been able to get a foot on the ground in SE up to the most recent crises period; the main exception being the Italian Lega Nord (Betz Citation1993).

3 The dataset and further information on the strategy of data collection and its reliability are available at the Observatory for Political Conflict and Democracy in Europe (PolDem) https://poldem.eui.eu/.

4 We classified the Italian Five Star Movement (M5S) as radical left. We are aware of the fact that this is a controversial choice, but it does not affect our results.

5 Alternatively, we classified the greens with the radical left. Again, this does not affect our general results on the party group differences.

6 We classified the Polish PiS and the Hungarian Fidesz as parties of the radical right. This is again a controversial choice (but see Mudde Citation2019)

7 The actual election result isa proxy of what the radical right’s competitors can expect. Based on opinion polls preceding the elections, the competitors in a given election are likely to have a pretty accurate idea of the eventual success of the radical right in the election in question.

8 This is indicated by the constant in all the models (which refers to the radical left), and by the sum of the constant and the centre-left effect for the centre-left.

9 This is indicated by the direct effect of the centre-right, which is negative and significant in all models.

10 Source: Eurostat. We divide the number of asylum applications by the country’s 2011 population in order to have comparable figures.

11 For more extended methodological discussions, seeDolezal (2008) and Dolezal et al. (2012). Further information can also be found online, hosted by the Observatory for Political Conflict and Democracy in Europe (PolDem) https://poldem.eui.eu/.

References

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik. 2016. “Niche Party Success and Mainstream Party Policy Shifts: How Green and Radical Right Parties Differ in Their Impact.” British Journal of Political Science 46: 417–436.

- Abou-Chadi, Tarik, Denis Cohen, and Markus Wagner. 2022. “The Centre-Right Versus the Radical Right: The Role of Migration Issues and Economic Grievances.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (2): 366–384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853903.

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2018. “Explaining Electoral Support for the Radical Right.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by Jens Rydgren, 143–165. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Arzheimer, Kai, and Carl C. Berning. 2019. “How the Alternative for Germany (AfD) and Their Voters Veered to the Radical Right: 2013-2017.” Electoral Studies 60: 1020–1040.

- Arzheimer, Kai, and Elizabeth Carter. 2006. “Political Opportunity Structures and Rightwing Extremist Party Success.” European Journal of Political Research 45: 419–443.

- Bale, Tim. 2003. “Cinderella and her Ugly Sister: The Mainstream and Extreme Right in Europe’s Bipolarising Party System.” West European Politics 26: 67–90.

- Betz, Hans-Georg. 1993. “The New Politics of Resentment: Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe.” Comparative Politics 25 (4): 413–427.

- Betz, Hans-Georg. 2002. “Conditions Favouring the Success and Failure of Radical Right-Wing Populist Parties in Contemporary Democracies.” In Democracies and the Populist Challenge, edited by Yves Meny, and Yves Surel, 197–213. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Bornschier, Simon. 2010. Cleavage Politics and the Populist Right. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Coman, Emanuel. 2017. “Dimensions of Political Conflict in West and East: An Application of Vote Scaling to 22 European Parliaments.” Party Politics 23 (3): 248–261.

- Dahlström, Carl, and Anders Sundell. 2012. “A Losing Gamble. How Mainstream Parties Facilitate Anti-Immigrant Party Success.” Electoral Studies 31: 353–363.

- Däubler, T., K. Benoit, S. Mikhaylov, and M. Laver. 2012. “Natural Sentences as Valid Units for Coded Political Texts.” British Journal of Political Science 42 (4): 937–951.

- de Vries, Catherine E. 2018a. Euroscepticism and the Future of European Integration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- de Vries, Catherine E. 2018b. “The Cosmopolitan-Parochial Divide: Changing Patterns of Party and Electoral Competition in the Netherlands and Beyond.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (11): 1541–1565.

- de Vries, C. E. and M. van de Wardt. 2011. “EU Issue Salience and Domestic Party Competition.” In Issue Salience in International Politics, edited by K. Oppermann and H. Viehrig, 173–187. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar].

- de Wilde, Pieter, Ruud Koopmans, Wolfgang Merkel, Oliver Strijbis, and Michael Zürn, ed. 2019. The Struggle Over Borders: Cosmopolitanism and Communitarianism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- de Wilde, Peter, Anna Leupold, and Hendrik Schmidtke. 2016. “Introduction: The Differentiated Politicization of European Governance.” West European Politics 39 (1): 3–22.

- Dolezal, M., L. Ennser-Jedenastik, W. C. Müller, and A. K. Winkler. 2016. “Analyzing Manifestos in Their Electoral Context: A New Approach Applied to Austria, 2002–2008.” Political Science Research and Methods 4 (3): 641–650.

- Eihmanis, Edgars. 2019. “Latvia – An Ever-Wider Gap: The Ethnic Divide in Latvian Party Politics.” In European Party Politics in Times of Crisis, edited by Swen Hutter and Hanspeter Kriesi, 236–258. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Enyedi, Zsolt. 2005. “The Role of Agency in Cleavage Formation.” European Journal of Political Research 44: 697–720.

- Fennema, Meindert, and Wouter Van Der Brug. 2003. “«Protest or Mainstream? How the European Anti-Immigrant Parties Developed Into Two Separate Groups by 19991.” European Journal of Political Research 42 (1): 55–76.

- Gessler, Theresa, and Sophia Hunger. 2019. The Politicization of Immigration During the Refugee Crisis. Unpubl. Paper. Florence: EUI.

- Gessler, Theresa, and Anna Kyriazi. 2019. “Hungary – A Hungarian Crisis or Just a Crisis in Hungary?” In European Party Politics in Times of Crisis, edited by Swen Hutter and Hanspeter Kriesi, 167–188. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grande, Edgar, Tobias Schwarzbörzl, and Matthias Fatke. 2018. “Politicizing Immigration in Western Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (10): 1444–1463. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2018.1531909

- Green-Pedersen, Christoffer. 2012. “A Giant Fast Asleep? Party Incentives and the Politicization of European Integration.” Political Studies 60 (1): 115–130.

- Hadj Abdou, Leila, Tim Bale, and Andrew Peter Geddes. 2022. Centre-right Parties and Immigration in an Era of Politicisation.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (2): 327–340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853901.

- Han, Kyung Joon. 2015. “The Impact of Radical Right-Wing Parties on the Positions of Mainstream Parties Regarding Multiculturalism.” West European Politics 38 (3): 557–576.

- Helbling, M., and A. Tresch. 2011. “Measuring Party Positions and Issue Salience from Media Coverage: Introducing and Cross-Validating New Indicators.” Electoral Studies 30 (1): 174–183.

- Hobolt, Sarah, and Catherine de Vries. 2015. “Issue Entrepreneurship and Multiparty Competition.” Comparative Political Studies 48 (9): 1159–1185.

- Hoeglinger, Dominik. 2016. “The Politicization of European Integration in Domestic Election Campaigns.” West European Politics 39 (1): 44–63.

- Hooghe, L., and G. Marks. 2018. “Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 109–135.

- Hurrelmann, A., A. Gora, and A. Wagner. 2015. “The Politicization of European Integration: More Than an Elite Affair?” Political Affairs 63 (1): 43–59.

- Hutter, S., and T. Gessler. 2019. “The Media Content Analysis and Cross-Validation.” In European Party Politics in Times of Crisis, edited by S. Hutter and H. Kriesi, 53–71. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hutter, Swen, and Edgar Grande. 2014. “Politicizing Europe in the National Electoral Arena: A Comparative Analysis of Five West European Countries: 1970-2010.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52 (5): 1002–1018.

- Hutter, Swen, and Hanspeter Kriesi, eds. 2019. European Party Politics in Times of Crisis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ignazi, Piero. 2003. Extreme Right Parties in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Inglehart, Ronald, and Pippa Norris. 2019. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ivarsflaten, Elisabeth. 2008. “What Unites Right-Wing Populists in Western Europe? Re-Examining Grievance Mobilization Models in Seven Successful Cases.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (1): 3–23.

- Kallis, Aristotle. 2018. “The Radical Right and Islamophobia.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, edited by Jens Rydgren, 42–60. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kleinnijenhuis, J., J. A. De Ridder, and E. M. Rietberg. 1997. “Reasoning in Economic Discourse. An Application of the Network Approach to the Dutch Press.” In Text Analysis for the Social Sciences: Methods for Drawing Statistical Inferences from Texts and Transcripts, edited by C. W. Roberts, 191–207. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter. 2018. “The 2017 French and German Elections.” Journal of Common Market Studies JCMS 56: 51–62.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, et al. 2020. PolDem-National Election Campaign Dataset, Version 1. Accessed June 23, 2020. https://poldem.eui.eu/.

- Kriesi, H., E. Grande, M. Dolezal, M. Helbling, D. Höglinger, S. Hutter, and B. Wüest. 2012. Political Conflict in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Edgar Grande, Romain Lachat, Martin Dolezal, Simon Bornschier, and Thimotheos Frey. 2008. West European Politics in the Age of Globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, and Julia Schulte-Cloos. 2020. “Support for Radical Parties in Western Europe: Structural Conflicts and Political Dynamics.” Electoral Studies 65: 102–138.

- Mainwaring, S., and T. R. Scully. 1995. “Introduction: Party Systems in Latin America.” In Building Democratic Institutions. Party Systems in Latin America, edited by S. Mainwaring and T. R. Scully. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

- Meguid, Bonnie M. 2005. “Competition Between Unequals: The Role of Mainstream Party Strategy in Niche Party Success.” American Political Science Review 99 (3): 347–359.

- Morlino, Leonardo, and Francesco Raniolo. 2017. The Impact of the Economic Crisis on South European Democracies. Houndmills Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mudde, Cas. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Oesch, Daniel. 2008. “Explaining Workers’ Support for Right-Wing Populist Parties in Western Europe: Evidence from Austria, Belgium, France, Norway, and Switzerland.” International Political Science Review 29 (3): 349–373.

- Powell, Eleanor Neff, and Joshua A. Tucker. 2014. “Revisiting Electoral Volatility in Post-Communist Countries: New Data, New Results and New Approaches.” British Journal of Political Science 44 (1): 123–147.

- Rauh, Christian. 2016. A Responsive Technocracy? EU Politicization and the Consumer Policies of the European Commission. Colchester: ECPR Press.

- Salek, Paulina, and Agnieszka Sztajdel. 2019. “Poland – ‘Modern’ Versus ‘Normal’: The Increasing Importance of the Cultural Divide.” In European Party Politics in Times of Crisis, edited by Swen Hutter and Hanspeter Kriesi, 189–213. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sitter, Nick. 2001. “The Politics of Opposition and European Integration in Scandinavia.” West European Politics 24 (4): 22–39.

- Statham, Paul, and Hansjörg Trenz. 2013. The Politicization of Europe. London: Routledge.

- Steenbergen, Marco, and David Scott. 2004. “Contesting Europe? The Salience of European Integration as a Party Issue.” In European Integration and Political Conflict, edited by G. Marks and M. Steenbergen, 165–192. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stockemer, D., T. Lentz, and D. Mayer. 2018. “Individual Predictors of the Radical Right-Wing Vote in Europe: A Meta-Analysis of Articles in Peer-Reviewed Journals (1995-2016).” Government and Opposition 53 (3): 569–593. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2018.2.

- Taylor, M., and V. M. Herman. 1971. “Party Systems and Government Stability.” American Political Science Review 65 (1): 28–37.

- Van der Brug, Wouter, Gianni D’Amato, Joost Berkhout, and Didier Ruedin, eds. 2016. The Politicisation of Migration. London: Routledge.

- Van der Brug, Wouter, Meindert Fennema, and Jean Tillie. 2005. “„Why Some Anti-Immigrant Parties Fail and Others Succeed. A Two-Step Model of Aggregate Electoral Support.”.” Comparative Political Studies 38 (5): 537–573.

- Van Middelaar, Luuk. 2016. “‘The Return of Politics – The European Union After the Crises in the Eurozone and Ukraine.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 54 (3): 495–507.

- Van Spanje, Joost. 2010. “Contagious Parties: Anti-Immigration Parties and Their Impact on Other Parties’ Immigration Stances in Contemporary Western Europe.” Party Politics 16: 563–586.

- Volkens, A., P. Lehmann, T. Matthieß, N. Merz, S. Regel, and B. Weßels. 2017. The Manifesto Data Collection. Manifesto Project, Version 2017b. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

- Werts, Hans, Peer Scheepers, and Marcel Lubbers. 2013. “Euro-scepticism and Radical Right-Wing Voting in Europe, 2002–2008: Social Cleavages, Socio-Political Attitudes and Contextual Characteristics Determining Voting for the Radical Right.” European Union Politics 14 (2): 183–205.

- Zürn, Michael. 2019. “Politicization Compared: At Global, European and National Levels.” Journal of European Public Policy 26 (7): 977–995.

A

Coding and issue categorisation

For further details on the coding and dataset, please check out the observatory for political conflict and Democracy (PolDem) www.poldem.eu

Table A1. List of countries and elections.

Table A2. List of newspapers.

Table A3. Issue categories.

Coding

As stated, we selected articles from two newspapers per country (see Table A.2). We selected all news articles that were published within two months before the national Election Day and reported on the electoral contest and national party politics more generally. In the case of early elections, we selected the period from the announcement of the election until the Election Day. Editorials and commentaries were excluded from the selection. The selection was done by an extensive keyword list including the names and abbreviations of political parties and key politicians from each party.

We then coded a sample of the selected articles using core sentence analysis (CSA). Following this type of relational content analysis, each grammatical sentence of an article is reduced to its most basic ‘core sentence(s)’ structure, which contain(s) only the subject, the object, and the direction of the relationship between the two. The core sentence approach was developed by Kleinnijenhuis and colleagues (e.g. Kleinnijenhuis, De Ridder, and Rietberg Citation1997) and further refined for the study of political conflict by Kriesi et al. (Citation2008, Citation2012).Footnote11 This type of quantitative content analysis allows us to study both issue positions and salience. The direction between actors and issues is quantified using a scale ranging from −1 to +1, with three intermediary positions. For example, the grammatical sentence ‘Party leader A rejects calls for leaving the Eurozone but supports a haircut on the country’s debt’ leads to two coded observations (Party A +1 Eurozone membership; Party A +1 haircut). For this paper, we only focus on relations between party actors and political issues, that is we neglect relations between different actors (on the number of cases, see Table A.2).

Media data

While media data come with biases, we think they offer ample opportunities to capture changes in the political space in times of crises. More precisely, we rely on media data because we are interested in publicly visible conflicts among the parties during the campaigns. In our opinion, media data are especially sensitive to political change and allow us to examine how the issues of the day map onto underlying issue dimensions. While this might lead to limited information about small parties (as they might be underreported in the media), it gives a good indication of the conflicts and actors that dominate the public debate. Alternative data sources do not come with the same biases. However, they are usually not linked to specific elections (especially expert surveys), do not contain positional and salience measure for all issues (especially manifesto data), and apply a rather rigid issue set of issue categories (which we tend to avoid by relying on a more inductive approach to new issues).

Hutter and Gessler (Citation2019) cross-validated the media-based data for the fifteen countries used in this article by comparing it with the well-known data from the Comparative Manifesto Project (CMP/Marpor) (Volkens et al. Citation2017). In line with previous results from Helbling and Tresch (Citation2011), the find that the CSA data used in this article represent party positions in an accurate way. That is, the results indicate very high convergence when comparing CSA and CMP data. Note that the correlation coefficients are as high as those from similar comparisons of CMP and expert data. Second, the CSA data converge with the CMP data regarding the level of salience across the various issue domains. However, they tend to capture a different dynamic regarding within-issue variation (both across countries and over-time). This can be interpreted as indicating that media-based data do capture a different agenda to that captured from direct party communications or expert surveys because of the media filter, campaign dynamics (including inter- and intra-party conflict) and external events (such as an economic crisis). From the point of view of the public debate and electoral campaigns’ influence on citizens, it seems fair to conclude that it is exactly this agenda represented in the media that is crucial.

Reliability

The coders were trained in several common and individual meetings, and they had to code the same ten English-speaking articles with sufficient accurateness before starting the actual coding. Moreover, we conducted a reliability test in the early phase of the coding. As in the case of related approaches, the coders disagreed slightly more often on the identification of the relevant coding units (i.e. the core sentences) than on the actual coding of specific variables – especially if we focus on the comparatively high aggregation levels of actors and issues used for the analyses in this book. But note that in a recent methodological study, Dolezal et al. (Citation2016) illustrate the advantages of core sentences as coding unit compared to approaches that either rely on so-called quasi-sentences (the approach of the Comparative Manifesto Project) or take grammatical sentences as coding units (e.g. Däubler et al. Citation2012). Mirroring the results from previous projects (see Anonymized), in the first reliability tests we obtained a coder agreement of a bit below 80 percent with respect to the identification of the core sentences (Cohen’s Kappa=0.76). Additional coder training and continuous monitoring during the coding process were provided to address remaining uncertainties and to increase the reliability coefficient above the typical acceptance level of 0.80. The reliability coefficients for all the variables analysed (at the aggregation level presented in the present study) were also clearly above this threshold (>0.90 for the most aggregated issue domains and party affiliations).

Systemic politicisation (systemic salience X polarisation)

We operationalise the two components of politicisation as follows: salience is measured by the share of core sentences on an issue category in percent of all sentences related to any issue. The indicator for the polarization of party positions is based on Taylor and Herman’s (Citation1971) index, which was originally designed to measure left-right polarisation in a party system. The polarisation of positions on a given issue category is computed as follow:

,where

is the salience of a particular issue category for party k,

is the position of party k on this issue category, and

is the weighted average position of all parties, where weights are provided by the party-specific salience of the issue. Since positions are always measured on scales ranging from −1 to +1, the distance to the average (and our measure of polarisation) can range between 0 and 1.

Appendix B. Politicisation of immigration by election & country