ABSTRACT

What is the role of non-state actors in the international politics of labour migration in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries? This paper employs a ‘migration diplomacy’ framework in order to examine the politics of regional mobility while interrogating the assumed centrality of the state in this process. It focuses on labour migration into the United Arab Emirates and draws on a range of primary sources in order to identify four types of non-state actors that seek to maximise their interests within the workings of Emirati migration diplomacy: public-private partnerships, namely the Tadbeer (‘procurement’) centres; corporations within the Emirati construction sector; business elites managing subcontracting companies; and, finally, non-governmental organisations and foreign consulting firms. The paper identifies how each of these four sets of actors pursues strategies that are able to strengthen, supplant, or undermine the state’s formal migration diplomacy aims. Furthermore, the Emirati case debunks the myth of the state as a centre of power in Gulf migration management via the kafāla (‘sponsorship’) system. Overall, the paper demonstates how a range of non-state actors can navigate migration management policymaking, thereby underlining the complexity of Gulf migration diplomacy.

Introduction

The Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf [or, Gulf Cooperation Council – GCC] constitutes one of the main clusters of migrant host states in the world, employing 35 million international migrants in 2019. The GCC accounts for over 10 per cent of all migrants globally and is responsible for over $100 billion in economic remittances, far surpassing American official development aid across the world (ILO Citation2020). Currently, the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia are two of the three top remittance-sending countries globally (IOM Citation2020). Despite the region’s centrality for cross-border mobility across the Global South, a number of gaps remain in terms of existing research on GCC migration politics. In this article, we seek to identify the main domestic actors involved in the international politics of labour immigration in the GCC countries, with a specific focus on the role of non-state actors in Emirati migration diplomacy. The literature on the politics of cross-border mobility in the GCC traditionally argues for the importance of state-level officials, who maintain a firm hand over migration either via direct control over entry or via the kafāla (‘sponsorship’) system. With regard to how Gulf countries’ foreign policymaking affects immigrant labour recruitment, in particular, the host state is historically seen as the key actor that facilitates bilateral labour agreements and governs immigrant labour recruitment. Yet, this perspective obscures a number of heretofore-unexamined non-state actors in Emirati and Gulf migration diplomacy.

Drawing on a wealth of primary and secondary sources in Arabic and English, we argue that four types of non-state actors enjoy a central role in UAE migration diplomacy. Firstly, select public-private partnerships, namely the Tadbeer (‘procurement’) centres, have emerged to strategically control migrant domestic work recruitment despite a formal state ban on hiring household service workers from Philippines and Indonesia. Secondly, corporations within the construction sector continue to recruit Indian construction workers despite the Emirati government’s reluctance to comply with India’s e-Migrate system due to fears of potential breaches of UAE sovereignty. Thirdly, economic elites employ sub-contracting companies as a way of circumventing the government’s diversification strategy in order to lower overall labour costs and maintain their competitive advantage in the Gulf markets. Finally, non-governmental organisations such as Migrant Forum in Asia [MFA] as well as foreign and local consulting firms feed into and facilitate the Emirati state’s national, regional, and global aims via the Abu Dhabi Dialogue process. Overall, our examination of Emirati migration diplomacy allows the identification and opening up of a new research agenda as well as a more systematic investigation of the role of non-state actors in the governance of migration in the Gulf States.

We proceed as follows: firstly, we examine existing work on the international politics of migration in the GCC as we identify a tendency to focus on state actors’ involvement in the management of regional cross-border mobility via the kafāla system. Secondly, we examine how a ‘migration diplomacy’ framework allows us to underline the importance of international processes in terms of migration processes in the GCC. We continue to enhance existing theorisation via a discussion of non-state actors’ engagement in migration diplomacy. We employ the case-study of the Emirates in order to identify four particular types of non-state actors: public-private partnerships such as the Tadbeer centres; corporations within the UAE construction sector; business elites managing subcontracting companies; and, finally, non-governmental organisations and foreign consulting firms. We examine how each of these four actors pursues strategies that seek to supplant, undermine, or strengthen the UAE’s formal migration diplomacy aims. We conclude by discussing how our findings enhance existing understandings of migration diplomacy while offering a more complete account of the international politics of cross-border mobility in the Emirates as well as the Gulf.

The international politics of migration in the Gulf

Although a number of social science works have addressed the politics of cross-border mobility in the Gulf (cf. Kamrava and Babar Citation2012; Jureidini Citation2019), few shed insights light onto the interaction between labour migration and GCC foreign policy. A primary source of scholarly research on the topic emerges out of political economy and demography, particularly in the decades immediately following the 1973 Arab-Israeli War and the two oil crises (Birks and Sinclair Citation1980; Seccombe Citation1985).Footnote1 This body of work tends to examine migration policymaking in the Gulf through the lens of demographic imbalances between GCC nationals and non-nationals (Kapiszewski Citation2001; Winckler Citation2009). By the early 1990s, migrant populations constituted over 70 percent of the total GCC workforce and, in some Gulf states, as much as 90 per cent (Fargues Citation2013; Malit and Al-Youha Citation2013). Not surprisingly, many scholars view the politics of Gulf migration via a regime or security lens that identifies how domestic elites sought to maintain control over the growing numbers of foreign workers (Baldwin-Edwards Citation2011), particularly in the aftermath of migrant mobilisation during the 1950s and 1960s (Vitalis Citation2007; Chalcraft Citation2010; Tsourapas Citation2018). In these analyses, the impact of the kafāla system for migrant groups across the Gulf is central (Gardner Citation2010), as is the case with broader works that discuss migrant rights (Ruhs Citation2013). While this line of research offers a clear understanding of the politicisation of labour migration in the Gulf, it provides few insights into how cross-border mobility features in the international politics of GCC states.

A second, smaller group of political economists offers an understanding of the foreign policy dimension of Gulf migration. Identifying that oil-producing Arab states accrue a significant amount of national revenue from unearned income, or rent (Beblawi Citation1987), these researchers seek to understand policymaking through the prism of rent-seeking behaviour (Ayubi Citation1996, 224–230; Hertog Citation2011). Shifts in the international politics of labour migration across the Gulf depend on global market fluctuations: for instance, the massive immigration of labourers in the 1970s during al-Tafra is linked to the influx of petrodollars (Korany Citation1986). Similarly, the subsequent shift from Arab to Asian immigrant labour in the 1980s and, more recently, to processes of labour market nationalisation and localisation has been driven by distinct political economy rationales (Shah Citation2018). Throughout these developments, the GCC states have constituted powerful actors that are contrasted with weaker, non-rentier countries of origin (Ibrahim Citation1982; Korany and Dessouki Citation2008). These power imbalances are evident in scholarly studies of how sending states’ diplomatic relations with the Gulf have shaped labour recruitment patterns – as in the case of Egypt (Tsourapas Citation2019), Yemen (Okruhlik and Conge Citation1997), or Jordan (Brand Citation2013). While such research identifies the importance of labour immigration in GCC foreign policymaking, the emphasis on oil-producing rentier states prioritises government actions, ultimately obscuring any other domestic actors that might affect Gulf migration management.Footnote2

More specifically, in the case of the UAE, a sizeable body of work in social sciences has examined migration processes, albeit primarily within sociology (Ali Citation2011; Sabban Citation2014), anthropology (Vora Citation2013; Inhorn Citation2015), and geography (Walsh Citation2009). In terms of the politics of UAE migration, work has focused primarily on the logistics of citizenship (Jamal Citation2015; Lori Citation2019), as well as political demography (De Bel-Air Citation2015). A small number of works also examines how economic and socio-cultural considerations have contributed to the espousal of ‘Emiratisation’ policies (Fargues and Shah Citation2018). However, with few exceptions (Ulrichsen Citation2016), international relations scholars of the Emirates tend to not examine cross-border mobility: although the foreign policy dimension of GCC labour migration falls within the scope of international relations, mainstream work on the international politics of the Gulf does not typically analyse cross-border mobility (see, for instance: Gause Citation2009; Hinnebusch Citation2013), as migration was considered a ‘low politics’ issue for much of the twentieth century (Hollifield Citation2015). That said, a small number of scholars employ single-case studies to identify a range of international politics processes – namely, how Gulf states’ migration policymaking interacts with ideological priorities (Russell Citation1989), regime threats (Van Hear Citation1998), or intra-GCC antagonism (Ulrichsen Citation2020). Thus, a distinct gap remains in terms of how sub-state actors might affect the international politics of UAE migration management.

Migration diplomacy and the role of non-state actors in Emirati foreign policy

In order to understand the role of non-state actors in the management of migration in the UAE while maintaining a focus on the foreign policy dimension, we adopt the framework of ‘migration diplomacy.’ Adamson and Tsourapas identify a distinct link between cross-border mobility and various forms of state diplomacy, and define migration diplomacy as ‘states’ use of diplomatic tools, processes, and procedures to manage cross-border population mobility’ (Tsourapas Citation2017; Adamson and Tsourapas Citation2019). Drawing on a long line of scholars (Thiollet Citation2011; İçduygu and Aksel Citation2014), they adopt a realist approach that highlights the interest and power of state actors in migration management. This moves beyond broader works on migration politics and governance by highlighting how cross-border population mobility management features in states’ international relations; Adamson and Tsourapas place the relationship between migration, interstate bargaining, and diplomacy at the forefront. Yet, while such a framework may identify the interests, linkages, and strategies shaping GCC states’ regulation of migration, it does not discuss the range of sub-state actors involved in shaping migration-related policies and practices. Even across the rising number of works within this emerging research agenda (Geddes and Maru Citation2020; Norman Citation2020; see also the special issue by Seeberg and Völkel Citation2020), the domestic sources of migration diplomacy have remained underexplored. A ‘migration diplomacy’ approach to GCC politics would address this gap by underlining the importance of the state in managing migration while also ‘unpacking’ it via identifying the gamut of domestic actors involved in shaping these practices.

In order to examine how non-state actors may affect GCC cross-border mobility politics and, more broadly, the workings of migration diplomacy, we focus on the single-case study of the United Arab Emirates. The Emirati case holds particular interest given the nature and development of that state: for one, the kafāla system involves a range of sub-state Emirati actors, as in other GCC countries. While there are multiple channels utilised by migrants to access this attractive job market – including social networks, travel agencies, and government-to-government agreements – private recruitment agencies on both the sending and receiving sides have come to drive substantial flows of workers. These private companies have, over the past 30 years, formed well-organized and profitable networks that provide an array of services to migrant workers and Emirati employers. In fact, they have taken over many of the functions of migrant labour recruitment that once were the main responsibility of sending states. As a result, research has identified how the interests of ruling elites and economic actors might intersect or collide, thereby paving the way for an analysis of the domestic sources of Emirati migration diplomacy. That said, the existing literature has thus far kept non-state actors’ involvement in migration separate from UAE foreign policy (cf. Malit and Naufal Citation2016).

At the same time, a focus on Emirati migration diplomacy brings to the forefront the extent to which the line between state- and non-state actors remains blurred. Numerous Emirati state officials are also business owners with keen interest in the area of labour migration. This is a broader GCC phenomenon in which ruling family members are also business elites across a variety of economic sectors within relatively porous states (Hertog, Luciani, and Valeri Citation2013), thereby contributing to a phenomenon that Hanieh terms khaleeji capital (Hanieh Citation2011). While the historical development of this particularity is beyond the scope of this paper (on this, see Ayubi Citation1996), the dichotomy between political and economic power is compounded by Gulf-wide limitations on foreign ownership of business and real estate, which expect potential foreign investors to partner with locals in order to set up their businesses. Again, in the UAE context, the importance of such particularities on Emirati foreign policy have been well-established (Rugh Citation2007), but with little attention paid to the management of cross-border mobility. The fact that nationals are reluctant to join sectors that have experienced enormous growth within the country – such as construction and infrastructure – continues to accentuate the need for foreign migrant labour.

Methodologically, we remain conscious of the pitfalls in utilising a single case-study method (B. Geddes Citation2003), but we also agree with its heuristic importance, particularly at the early stages of a research agenda (George and Bennett Citation2005). In this case, the single-case study of the UAE allows a deepening of our understanding of the actors involved in shaping migration diplomacy and governance in the GCC. We consider the Emirati as a crucial case (Gerring Citation2007), given the centrality of the UAE in terms of migrant stock and flows in the GCC both with regard to intra-Arab as well as extra-regional labour migration, primarily from South and Southeast Asia. Recognising the challenges in identifying accurate data on migration in autocratic contexts, and in the UAE in particular (De Bel-Air Citation2015), we engage in an ambitious data collection strategy that draws on a range of primary and secondary reports in both Arabic and English, field observation in Dubai, as well as data drawn from international organisations and media sources.

Migration diplomacy in the United Arab Emirates

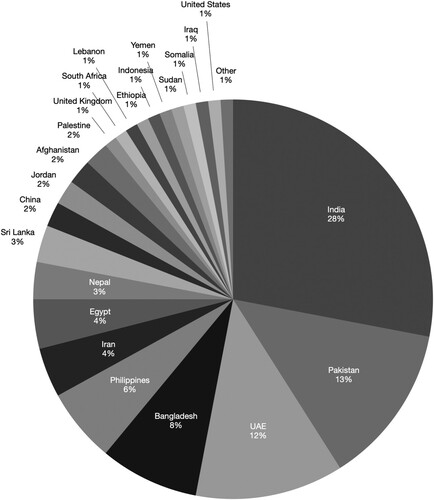

The UAE has emerged as a main destination for temporary labour migrants in the Gulf, second only to Saudi Arabia in terms of both migrant stock and outflow of remittances (IOM Citation2020). Created as a federation of seven emirates in 1971, the state develops migration policies both on the federal and the emirate-level, including numerous attempts at state-wide reform. Since the early 2000s, soaring oil prices have led to the recruitment of large numbers of foreign workers – primarily Indian, Bangladeshi, and Pakistani labourers – who currently make up over 90 percent of the country’s private workforce (Martin and Malit Citation2016; see and ). However, recruitment is guided by distinct safety valves set by the Emirati state. The ‘demographic imbalance’ that characterises the Emirates and all GCC states, particularly with regard to the Arab/non-Arab ratio, coupled with the fear of migrant-led political unrest have contributed to numerous state practices, namely the pre-eminence of granting citizenship via nasab (‘genealogy’) rather than jus solis; the expansion of the kafāla system that manages temporary contractual employment cycles; as well as the introduction of nationalisation processes that aim to prioritise employment for local nationals. By 2010 the Federal Demographic Council was established by Cabinet Federal Decree No. 3, tasked with restoring the country’s ‘demographic balance’ (Lori Citation2019, 118).

Figure 1. 2014 estimate of population residing in the UAE, by country of citizenship. Source: Gulf Labor Market and Migration. Available at: http://gulfmigration.eu/uae-estimates-ofpopulation-residing-in-the-uae-by-country-of-citizenship-selected-countries-2014.

Table 1. Total population and percentage of nationals and non-nationals in the UAE.

The UAE’s migration diplomacy strategy in terms of bilateral agreements with labour-sending countries and international organisations is developed by the state. For much of the country’s history, UAE migration diplomacy extended solely to regional governance and multilateral initiatives within the GCC context. Upon independence from the British, the Trucial States had agreed to a common immigration and citizenship policy that put forth standardised guidelines for issuing visas and identity documents, thereby transferring the authority over foreign residency permits to the Emirati state (Lori Citation2019, 113). Much like neighbouring oil-rich Arab states, the UAE experienced a surge of migrants from poorer Arab states, notably Yemen and Egypt, throughout the 1970s and 1980s. Over time, Gulf states would come to consider Arab workers as a security threat, particularly due to perception of certain migrant groups siding with Iraq during the 1990 Gulf War, which led to Arabs’ expulsion and their gradual replacement with Southeast Asian workers. The subsequent construction boom in the UAE contributed to further recruitment of Southeast Asian migrants, as international attention shifted towards human and labour rights abuses of noncitizens across GCC migrant host states, including the Emirates. Indeed, despite their differences, the GCC states share a dependence on foreign labour force as well as the reliance on the kafāla guest worker programme. Under the latter, foreign labourers – technically, temporary contractual workers rather than immigrants – enter the country as guest workers on fixed-term contracts, employed by a national citizen acting as their sponsor (kafeel). The human and labour rights associated with the kafāla system – which, to borrow Lori’s term, renders foreign workers ‘permanently deportable’ – has dominated coverage of Gulf migration politics.Footnote3 More recently, in 2016, the International Trade Union Confederation filed a case against the UAE for failing to uphold the International Labour Organization’s Convention Concerning Forced or Compulsory Labour (Convention No. 29). The ILO noted that the UAE ‘lacks an adequate legal framework that prevents migrant workers from falling into situations or practices amounting to forced labour,’ making a range of recommendations (ILO Citation2017).

It is at this time that the UAE turned to the Abu Dhabi Dialogue (ADD) as a way to improve its international image as a migrant host state. Founded in 2008, the ADD emerged as a ministerial-level consultative process on migration between the Gulf States and the Colombo Process countries, namely Asian sending states.Footnote4 This initiative laid the ground-work for a more ambitious UAE migration diplomacy, as the country provides the permanent secretariat for the ADD process and has held its chairmanship twice so far. The ADD process has aimed to increase state collaboration and engagement between Asian and GCC countries, while also encouraging regional project collaborations based on common thematic interests such as migrant recruitment migration governance technology (albeit excluding other topics, namely labour rights or migrants’ access to legal protection). The ADD also aims for multilateral engagement with other non-state actors like NGOs, foreign and local consulting firms, academic institutions, as well as international organisations, such as the International Organization for Migration. In the past few years, partly in response to the ILO case, the UAE has allowed a range of international human rights groups to critique and, ultimately, shape its migration policymaking. It is in the context of such state- and ADD-centred initiatives that a range of non-state actors now seek to affect Emirati migration diplomacy, as will be discussed below.

A. Public-private partnerships – the Tadbeer centres

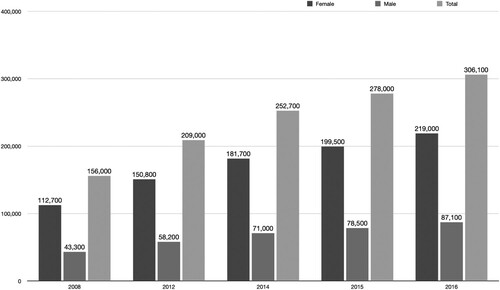

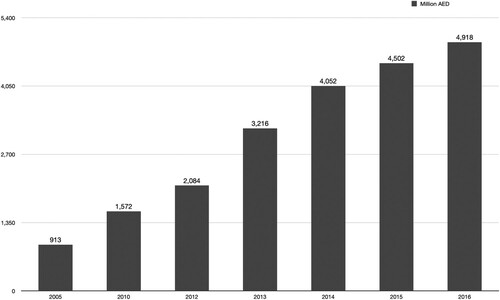

With various international organisations and rights groups condemning the illegal and unethical recruitment practices (i.e. debt bondage, modern slavery, excessive costs) in the UAE domestic work sector, the state forcefully attempted to gain tighter control of the interregional domestic work recruitment process. Currently, at least 306,000 migrant domestic workers are living in the UAE (Abu Dhabi Dialogue Citation2018).Footnote5 Following the passage of the UAE Federal Law No. 10 of 2017 on Domestic Workers, the Ministry of Human Resources and Emiratization (MOHRE) established the Tadbeer centres to indirectly control and regulate the recruitment costs, processes, and placement of migrant domestic workers in the country (for full text, see United Arab Emirates Citation2017). Framed as public-private partnerships, the Tadbeer centres’ ownership structure suggests that they could be either wholly owned by nationals or in cooperation with an expatriate business partner. Currently, of the 24 Tadbeer centres planned initially, 23 are in full operation (Ahmad Citation2020). They are located across various emirates, including Dubai (6), Abu Dhabi (6), Fujairah (4), Ras Al Khaima (3), Ajman (3), and Sharjah (1). At the same time, MOHRE monitors and regulates the centres' business and recruitment transactions in migrant-sending countries through extensive bilateral negotiation processes and agreements (i.e. MOUs). This institutional process enables the UAE state to extend its long arm into the private sector, as it indirectly aims to govern a highly valuable and profitable sector in the UAE labour market and society, namely domestic work. It is worth noting that this sector that generates significant government revenue due to the high demand from both emirati and expatriate families (see and ).

Figure 2. Number of domestic workers in Abu Dhabi and Dubai by sex, 2008-2016. Source: Abu Dhabi Dialogue (Citation2018).

Figure 3. Compensation of dometic workers in Abu Dhabi, 2005-2016. Source: Abu Dhabi Dialogue (Citation2018).

While the establishment of the Tadbeer centres strengthened the state’s control over the private sector, it also inevitably accentuated tensions with migrant-sending states. As Federal Law No. 10 replaced manpower agencies for recruiting domestic workers with Tadbeer centres, the latter now have the principal, exclusive right to recruit migrant domestic workers and issue employment visas to migrant domestic workers (United Arab Emirates Citation2020). However, the Tadbeer centres are not able to offer a guaranteed employment contract to migrant workers before their arrival in the UAE to the chagrin of migrant sending states, particularly the Philippines, which is currently the largest exporter of domestic workers to both the UAE and the Middle East.Footnote6 In fact, the Philippine Overseas Employment and Administration (POEA) mandates that Tadbeer centres need to provide such support: they should offer and guarantee a state-approved employment contract to all Filipino workers, including domestic workers, before the Philippines can approve any foreign employment agreement or their departure (POEA Citation2016). Yet, existing UAE hiring practices do not guarantee an employment contract with an employer; in fact, they often employ domestic workers via an ‘auction’ mechanism.Footnote7

These conflicting state regulations have created not only bilateral migration diplomacy tensions on issues of migrant domestic work but laid the ground for migrant abuse. Transnational recruitment practices contribute to massive trafficking of Filipina domestic workers, particularly given the existing deployment ban imposed by the Philippines on the formal recruitment on Filipino domestic workers due to their perceived precarious legal status and rights in the UAE, which has been in place since June 2014. This has negatively impacted the private sector’s inter-regional recruitment businesses in the Philippine-UAE migration corridor, as prospective Filipina domestic workers seek to benefit from the Emirates’ ‘soft’ immigration system that allows recruitment brokers to convert a tourist visa into a working employment visa. As they bypass the formal ban and enter the Emirates after transiting through Association of Southeast Asian Nations [ASEAN] countries, Filipina domestic workers are unable to receive full labour and employment protection from the Tadbeer centres. But Tadbeer centres, themselves a novel institution within the UAE, are not fully recognised actors by the Filipino state, further accentuating the plight of migrant workers.

Thus, the Tadbeer centres play into existing tensions between the Philippines and the UAE, which have been further exacerbated by continuous reports of abuse. This has prompted the Philippines’ attention to conditions surrounding migrant domestic work in other Gulf states, such as Kuwait and Saudi Arabia, where they are equally problematic - if not more. In fact, the 2018 deaths of two Filipina domestic workers in Kuwait have forced the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) to issue the following advisory statement on 30 December 2019:

The Philippine embassy in Kuwait is coordinating closely with Kuwaiti authorities to ensure that justice will be served. The DFA has summoned the Kuwaiti Ambassador in Manila to express the Government’s outrage over the seeming lack of protection of our domestic workers at the hands of their employers and to press for complete transparency in the investigation of the case and to call for the swift prosecution of the perpetrators to the fullest extent of the law.

B. Corporations in the construction sector

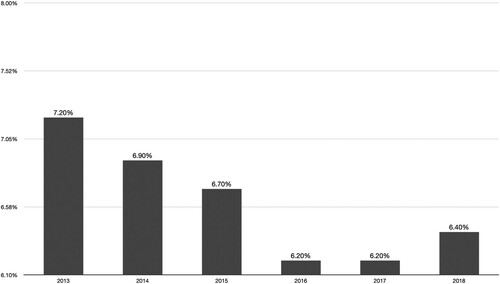

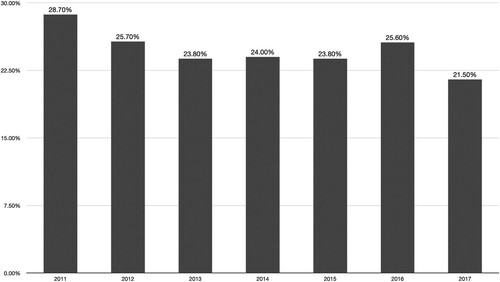

Beyond the Tadbeer centres, the private construction sector is a second major non-state actor in the UAE’s migration diplomacy. Construction holds a critical position in the UAE state and economy, given its powerful ability to build vital infrastructures that is necessary for global economic investments. Construction is also the most labour-intensive sector in Dubai, accounting for 6.4% of its Gross Domestic Product and employing 21.9% of the Emirate’s total workforce, or 607,640 workers (see and ). Largely dominated by locals or, in some cases, joint partnerships with expatriates or multinational companies [MNCs], the UAE construction sector depends on migrant-sending countries, primarily India or Pakistan, to address the structural labour shortages in the national economy. The cheap labour cost, combined with the close proximity of these migrant-sending states, has made India and Pakistan attractive to Emirati construction companies. The deep historical trade and migratory ties between the Emirates and South Asia is also important (Abdul-Aziz, Olanrewaju, and Ahmed Citation2018). Currently, over 3.42 million Indians and 1.5 million Pakistanis work in the UAE, constituting 39% of the country’s total population.

Figure 4. Construction sector contribution to Dubai GDP (%). Source: UAE Government Portal (Citation2020).

Figure 5. Share of the construction sector in Dubai total employment. Source: UAE Government Portal (Citation2020).

In the UAE construction sector, cross-border mobility of migrant workers requires complex bilateral interstate negotiations, which often pose serious critical diplomatic tensions due to the differential interests, priorities, and constraints for both the UAE and migrant-sending states. The Indian government’s digital recruitment portal, eMigrate, was put in place in 2015 and has produced particular diplomatic disputes due to the perceived intrusion of the sovereignty of the existing recruitment system. The eMigrate project is an initiative of the Overseas Employment Division of India’s Ministry of External Affairs, which aims to ‘automate the current emigration processes and eco-system’ via a ‘transformational e-governance program with a vision to transform emigration into a simple, transparent, orderly and humane process’ across a common platform.Footnote8 Currently, eMigrate mandates all foreign firms, including UAE construction companies, to submit their employment contracts and agreements online in order to verify veracity and compliance. UAE-based construction companies are also mandated to sign a legal undertaking in the host country that guarantees their state compliance levels and commitment to protecting the rights of Indian construction workers abroad.

Competition over the two states’ migration diplomacy strategies soon emerged. On the one hand, the Emirates view the Indian scheme as ‘intrusive’ and violating UAE ‘sovereignty’ (Al-Arabiya Citation2017). As the UAE Ambassador to India, Dr. Ahmed al Banna, argues:

India wants to build a databank to extract information about these companies in the UAE. We consider this a breach of our sovereignty. Some information only the UAE government or concerned ministry is allowed to collect. It is also not in the Indian Embassy or Consulate’s ambit to conduct inspections, and we have taken strong objection to that. This is not India’s work, this is ours. We have offered Indian authorities that we will give them the information they desire. (Ibid.)

In the COVID-19 pandemic context, interstate tensions between India and the UAE involving the construction sector have risen given the potential need to repatriate migrant construction workers. As the post-2020 lockdowns intensify in the UAE, most construction companies have ceased their building infrastructure operations. They largely experienced financial revenue losses, which forced them to partially or fully terminate the contracts of thousands of migrant construction workers, who live in high-risk migrant industrial camps. After diplomatically requesting that migrant-sending states facilitate the repatriation requests of their nationals, the UAE state has encountered some sending-states’ non-cooperative status, including India. This forced the UAE government and the Federation of the UAE Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FCCI) to ‘reconsider’ ties with migrant-sending countries, specifically India, by threatening to reduce future quotas or recruitment flows. With COVID-19 outbreaks intensifying across the Emirates, interstate tension between states, along with the construction companies’ difficulty in surviving the economy (i.e. business loss) will certainly deepen the interstate tension between India and the construction companies. As the FCCI specifically emphasises:

Unfortunately, some countries are ignoring all the humanitarian and constitutional principles by refusing to welcome their citizens or taking responsibility of transferring them home despite what their constitutions or passports are showing and slogans of citizens’ rights inside and outside their borders. These countries should abide by their slogans and mottos. The recent conditions showed that their mottos and slogans are mere sayings with no meanings whatsoever. Not allowing them to enter their homeland is against all principles of human rights, international conventions and citizenship rights. (Khaleej Times Citation2020)

C. Subcontracting companies

The development of Emirati migration diplomacy is influenced by another actor that is connected to the UAE construction sector, namely subcontracting companies (Segall and Labowitz Citation2017; Malit, Jenny, and Kristian Citation2019). These have formed to capitalise on the sector’s booming performance and to provide room for manoeuvre for domestic business elites. This is partly due to the stipulations of the UAE Vision 2021 National Agenda, with MOHRE’s ‘cultural diversity enhancement program’ expecting that each construction company be graded on the diversity of its workforce, estimated according to a ratio of employees’ nationalities. No one nationality is allowed to exceed 50%. As one senior official at MOHRE explains:

The cultural diversity enhancement program will support UAE employers by reducing the labor recruitment costs for establishments in which no less than 50 per cent of their workforce belong to a variety of cultural backgrounds. (MOHRE Citation2019)

As a result, domestic economic elites – often in joint partnerships with wealthy expatriates – have formed subcontracting companies (or ‘manpower supply agencies’) that enter into business partnerships with large construction companies. These subcontracting companies constitute third parties that have various expertise and capabilities to carry out specific portions of the works while, importantly, not being bound by the 50% rule. They exist to serve the overall national interests of the UAE state and the private sector, while also simultaneously navigating interstate regulations that are often marred by diplomatic tensions and human rights abuses. Companies like these, which play a crucial role in managing the cross-border mobility of millions of Indian, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and Nepali migrant workers, often charge visa fees to workers themselves, which is illegal according to UAE law; they refuge to pay agreed wages; they confiscate workers’ passports, and offer little protection against safety and health hazards.

In terms of their importance for Emirati migration diplomacy, subcontracting companies have evolved to act as ‘conduits’ that operate on the interstate level between the UAE, countries of origin, namely India and other South Asian countries, and private construction companies. More prominently, subcontracting companies’ operations frequently mar the country’s international profile: in 2015, Nardello & Co. highlighted the exploitative role they played in the construction of the NYU Abu Dhabi campus (Nardello & Co. Citation2015). Human and labour rights violations are particularly prominent by subcontracting companies in the construction sector (Human Rights Watch Citation2006). These violations have a direct effect on Emirati migration diplomacy: in 2012, the UAE government implemented labour market restrictions to Bangladeshi migrant workers, citing various illegal and unethical recruitment violations such as excessive recruitment costs, debt bondage, and high rates of absconding in the Bangladesh-UAE migration corridor (Herve and Arslan Citation2017). A senior officer of the UAE-based Bangladesh Civil Society for Migration, Syed Saiful Haque, acknowledged that ‘it can be described as a diplomatic failure of the Bangladesh government to reopen the UAE labour market over the last eight years’ (New Age Citation2020). This ongoing diplomatic incident did not only impact subcontracting companies’ access to millions of Bangladeshi construction workers, but also has continued to become an interstate diplomatic tension between the UAE and Bangladeshi governments in the Emirati labour market. In the context of combined legal and political pressures, the UAE introduced a range of initiatives, including the UAE Federal Law No. 10 of 2017 on Domestic Workers, as discussed above.

Furthermore, the immediate repatriation of low-skilled Indian or South Asian migrant construction workers due to COVID19 will become a critical issue, given the non-payment behaviour of subcontracting companies. For instance, MOHRE implemented Ministerial Resolution No. 279 of 2020 (‘Regarding the stability of employment in private sector companies during the period applying precautionary measures to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus') protecting the rights of employers by enabling them to restructure existing employment contracts. In particular, the Emirati state’s ministerial resolution empowered all Emirati employers, including subcontracting companies, to change contractual agreements with workers from full to part-time and amend their prevailing wage scales to offset any financial losses in the context of the current economic downturn due to COVID19 pandemic. However, if subcontracting companies fail to pay workers’ settlements or facilitate their repatriation, it is highly likely that they will face massive criticisms from various global rights groups for their failure to uphold the labour and human rights of migrant workers. This particular situation has already been highlighted by multiple global rights and media groups that blame the UAE private sector, numerous subcontracting companies, as well as the state for their failure to extend adequate social protection to migrant workers. In other words, sub-state actors within the Emirates private play a dominant role in shaping the country’s foreign policy image, but in a manner that also exposes the state's sectoral vulnerabilities.

D. NGOs & consulting firms

Finally, migrant NGOs and foreign consulting firms have played an increasingly important role in shaping the UAE's migration diplomacy framework strategy. Various migrant rights NGOs have consistently exerted transnational political pressures towards the UAE, including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, International Trade Union Confederation. Others have increasingly developed deeper institutional cooperation with the UAE: Migrant Forum in Asia [MFA], for example, is an influential Philippine-based regional network of non-government organizations (NGOs), associations and trade unions of workers, and individual advocates in Asia. Committed to protect and promote the rights and welfare of workers, MFA has historically condemned the labour rights and abuses of migrant workers under the kafāla sponsorship system in the Gulf countries, including the Emirates. Specific criticisms revolved around workers’ weak access to justice, immobility, contract slavery, debt bondage, and illegal/unethical recruitment practices, such as contract substitution.Footnote9 In its 2011 report on the UAE, for instance, MFA identified how

serious gaps exist between the procedures as proscribed by national laws/policies and the actual experience of migrants as they navigate the recruitment process. These gaps leave workers vulnerable to mistreatment, abuse, and exploitation on the part of unscrupulous recruitment agencies and their sub-agents. Numerous gaps between policy and practice have been identified across a variety of national contexts; the most salient of these is the point of collusion between recruitment agencies in the sending and receiving states. (Migrant Forum in Asia Citation2011)

Other non-state actors, including foreign and local consulting companies, such as McKinsey&Company, and academic institutions have also contributed to the shaping of UAE migration diplomacy. While it is difficult to examine the degree and impact of foreign consulting companies on the UAE migration policy, these actors play both technical and symbolic roles in various migration policy designs for the UAE state. They, for example, often prepare various technical research reports and policy recommendations to the UAE state, shaping – directly or indirectly – the state’s migration governance or policy options or choices both in the short and long run. While the UAE state’s decision largely prevails, it is logical to conclude that these non-state actors in UAE migration diplomacy still play a critical role not only in the development of their migration governance/diplomacy engagements but also in building their foreign policy image and reputation in both regional and global migration governance context.

Conclusion

In this paper, we have examined the workings of four distinct non-state actors within the UAE – the Tadbeer centres, construction companies, subcontracting firms, as well as NGOs and foreign consulting firms – as they seek to affect Emirati migration diplomacy. Usually examined from a state-centred perspective, Emirati migration diplomacy is actually shaped by a range of non-state actors: the Tadbeer centres accentuate bilateral tensions between the UAE and sending states, particularly the Philippines; the domestic construction sector’s interest in recruiting Indian workers via eMigrate is seen as threatening UAE sovereignty; subcontracting companies frequently aim to circumvent Emirati legal stipulations, thereby creating further areas of conflict with migrant-sending states; finally, NGOs and consulting firms are often co-opted by the Emirati state in order to contribute to the attractive regional and global image that the government seeks to put forth. Together, these four types of non-state actors indicate the wealth and complexity of processes that underpin the evolution and practices of Emirati migration diplomacy.

Beyond contributing to the nascent literature on the politics of migration into the UAE, we also seek to push the field further by interrogating the extent to which state actors are solely responsible for the development and conduct of 'migration diplomacy.' In particular, the UAE example highlights how foreign policy decision-making vis-à-vis cross-border mobility is also shaped by a range of firms, corporations, domestic institutions, as well as local and expatriate economic elites. Each of these actors is driven by separate agendas and pursues interest-maximising strategies in ways that may strengthen or undermine formal state agendas: occasionally, these actors support the Emirati image of a global player in the governance of labour migration – as in the case of select NGOs or consulting companies; other times, non-state actors seek to bypass formal regulations – as in the case of subcontracting companies; finally, they may seek to opposte governmental regulations – as in the case of the construction sector. Throughout these processes, the UAE state itself develops novel institutions – such as the Tadbeer centres – as it seeks to reconcile divergent domestic political and economic agendas.

At the same time, the findings of the paper hint at potential diffusion effects in terms of migration diplomacy processes across the GCC, which have yet to be examined in the relevant literature: Saudi migration management is dominated by business-government coalitions, with recruitment firms constituting ‘key mediators in migration diplomacy,’ in the words of one CEO, who had participated in the negotiations on minimum wages with Indonesia (Thiollet Citation2019). Not unlike patterns found in the Emirates, Saudi Oger, a local construction firm, faced complaints of not paying wages to tens of thousands of Indian workers in 2016; this created a bilateral diplomatic incident that involved the distribution of 15 tons of food by the Consulate General of India in Jeddah to avoid a ‘food crisis,’ as the Indian foreign minister declared (Reuters Citation2016). Kuwait, as well as other Gulf states, have faced bilateral crises with migrant sending states that involve domestic workers recruited via a range of labour agencies – again, reminiscent of the workings of the Tadbeer centres examined above.

Overall, beyond distinct findings about the management of UAE migration diplomacy, this paper points to a range of future work that could follow from this analysis. Firstly, we argue that the involvement of non-state actors in the foreign policy of migration states is important and merits further examination. We demonstrate here that, even in cases of non-democratic regimes, policymaking on migration continues to take into account the interests of a range of sub-state actors. Thus, targeted research on the international politics of migration across the GCC would allow for a more complete understanding of the governance of cross-border mobility. Secondly, we demonstrate the utility of ‘migration diplomacy’ as a framework for understanding the interstate dimension of migration management while arguing for further work on the importance of non-state actors. If we go beyond the Emirates or the GCC context, it becomes apparent how a range of political parties, media organisations, transnational corporations as well as international organisations seek to affect the conduct of migration diplomacy in Europe, North America, as well as the Global South. Ultimately, the international politics of global migration and mobility continue to provide a ripe area for further analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We note that the GCC emerges in 1981 as a regional organisation between Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. For ease of reading, we use the term to denote the Arab states of the Persian Gulf (except Iraq) in the pre-1981 period, as well.

2 For a notable exception, see Thiollet (Citation2019) on public-private partnerships across the GCC.

3 It is worth noting that, faced with international criticism, a number of GCC states have made steps to restrict the kafāla system, most notably Qatar.

4 The Abu Dhabi Dialogue is a voluntary and non-binding inter-government consultative process, engaging seven Asian host states: Bahrain, Kuwait, Malaysia, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and UAE; and eleven sending states: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, China, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Vietnam. Regular observers include the IOM, ILO, the private sector, and civil society actors. The current chair is Sri Lanka.

5 This data excludes migrant domestic workers who are based in the Northern Emirates (Sharjah, Ajman, Fujairah, Ras Al Khaima, and Umm Al Quwain). It also excludes undocumented, freelance, and part-time domestic workers for local and expatriate employers in the Gulf countries.

6 Approximately 679,819 Filipinos live in the UAE, according to the latest estimates.

7 Current UAE hiring practices include (1) direct sponsorship; (2) direct sponsorship after 6 months; (3) Tadbeer sponsorship; and, (4) time-based packages.

8 India’s online platform is available at: https://emigrate.gov.in/ext/about.action.

9 See MFA’s website, http://mfasia.org/resources/reports/all-mfa-reports/.

References

- Abdul-Aziz, Abdul-Rashid, Abdul Lateef Olanrewaju, and Abdullahi Umar Ahmed. 2018. “South Asian Migrants and the Construction Sector of the Gulf.” In South Asian Migration in the Gulf: Causes and Consequences, edited by Mehdi Chowdhury and S. Irudaya Rajan, 165–189. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Abu Dhabi Dialogue. 2018. “The Future of Domestic Work in the GCC.” http://abudhabidialogue.org.ae/library.

- Adamson, Fiona B., and Gerasimos Tsourapas. 2019. “Migration Diplomacy in World Politics.” International Studies Perspectives 20 (2): 113–128.

- Ahmad, Anwar. 2020. “COVID-19: All Tasheel and Tadbeer Offices Closed in UAE from April 2.” Gulf News. https://gulfnews.com/uae/government/covid-19-all-tasheel-and-tadbeer-offices-closed-in-uae-from-april-2-1.70728605.

- Al-Arabiya. 2017. “UAE Objects to India’s EMigrate Scheme Citing Sovereignty Issues.” Al Arabiya English, May 28, 2017. https://english.alarabiya.net/en/features/2017/05/28/UAE-objects-to-India-s-eMigrate-scheme-citing-sovereignty-issues.html.

- Ali, Syed. 2011. “Going and Coming and Going Again: Second-Generation Migrants in Dubai.” Mobilities 6 (4): 553–568.

- Ayubi, Nazih N. 1996. Over-stating the Arab state: Politics and Society in the Middle East. London: I.B. Tauris Publishers

- Baldwin-Edwards, Martin. 2011. "Labour Immigration and Labour Markets in the GCC Countries: National Patterns and Trends.” The Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States.

- Beblawi, Hazem. 1987. “The Rentier State in the Arab World.” Arab Studies Quarterly 9 (4): 383–398.

- Birks, J. S., and C. A. Sinclair. 1980. International Migration and Development in the Arab Region. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Brand, Laurie A. 2013. Jordan’s Inter-Arab Relations: The Political Economy of Alliance-Making. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Chalcraft, John. 2010. “Monarchy, Migration and Hegemony in the Arabian Peninsula.” LSE Kuwait Programme on Development, Governance and Globalisation in the Gulf States. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/32556/.

- De Bel-Air, Françoise. 2015. “Demography, Migration, and the Labour Market in the UAE”. Migration Policy Centre; GLMM; Explanatory Note. https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/36375.

- Fargues, Philippe. 2013. “International Migration and the Nation State in Arab Countries.” Middle East Law and Governance 5 (1–2): 5–35.

- Fargues, Philippe, and Nasra M. Shah. 2018. Migration to the Gulf: Policies in Sending and Receiving Countries. Cambridge: Gulf Research Centre.

- Gardner, Andrew M. 2010. City of Strangers: Gulf Migration and the Indian Community in Bahrain. Ithaca: ILR Press.

- Gause, F. Gregory. 2009. The International Relations of the Persian Gulf. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Geddes, Barbara. 2003. Paradigms and Sand Castles: Theory Building and Research Design in Comparative Politics. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Geddes, Andrew, and Mehari Taddele Maru. 2020. “Localising Migration Diplomacy in Africa? Ethiopia in Its Regional and International Setting.” EUI Working Papers, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced StudiesMigration Policy Centre.

- George, Alexander L., and Andrew Bennett. 2005. Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Gerring, John. 2007. “Is There a (Viable) Crucial-Case Method?” Comparative Political Studies 40 (3): 231–253.

- Hanieh, Adam. 2011. Capitalism and Class in the Gulf Arab States. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan

- Hertog, Steffen. 2011. Princes, Brokers, and Bureaucrats: Oil and the State in Saudi Arabia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hertog, Steffen, Giacomo Luciani, and Marc Valeri, eds. 2013. Business Politics in the Middle East. London: Hurst and Company

- Hervé, Philippe, and Cansin Arslan. 2017. “Trends in Labor Migration in Asia.” Safeguarding the Rights of Asian Migrant Workers from Home to the Workplace. Bangkok: ILO. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/230176/adbi-safeguarding-rights-asian-migrant-workers.pdf.

- Hinnebusch, Raymond. 2013. The International Politics of the Middle East. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hollifield, James F. 2015. “The Politics of International Migration: How Can We “Bring the State Back In”?” In Migration Theory: Talking Across Disciplines, edited by James F. Hollifield, and Caroline F. Brettell, 3rd ed., 183–237. New York: Routledge.

- Human Rights Watch. 2006. “Building Towers, Cheating Workers - Exploitation of Migrant Construction Workers in the United Arab Emirates.” https://www.hrw.org/report/2006/11/11/building-towers-cheating-workers/exploitation-migrant-construction-workers-united.

- Human Rights Watch. 2014. Already Bought You: Abuse and Exploitation of Female Migrant Domestic Workers in the United Arab Emirates. https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/reports/uae1014_forUpload.pdf.

- İçduygu, Ahmet, and Damla B. Aksel. 2014. “Two-to-Tango in Migration Diplomacy: Negotiating Readmission Agreement Between the Eu and Turkey.” European Journal of Migration and Law 16 (3): 337–363.

- Ibrahim, Saad Eddin. 1982. The New Arab Social Order: A Study of the Social Impact of Oil Wealth. Westview’s Special Studies on the Middle East. Boulder: Westview.

- ILO. 2017. “Observation (CEACR) - Adopted 2016.” https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:13100:0::NO::P13100_COMMENT_ID:3292702.

- ILO. 2020. “Labour Migration (Arab States).” https://www.ilo.org/beirut/areasofwork/labour-migration/lang–en/index.htm.

- Inhorn, Marcia C. 2015. Cosmopolitan Conceptions: IVF Sojourns in Global Dubai. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- IOM. 2020. “World Migration Report 2020.” Geneva. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2020.pdf.

- Jamal, Manal A. 2015. “The “Tiering” of Citizenship and Residency and the “Hierarchization” of Migrant Communities: The United Arab Emirates in Historical Context.” International Migration Review 49 (3): 601–632.

- Jureidini, Ray. 2019. “Global Governance and Labour Migration in the GCC.” In Global Governance and Muslim Organizations, edited by Leslie A. Pal and M. Everen Tok, 339–364. Cham: Palgrave.

- Kamrava, Mehran, and Zahra Babar, eds. 2012. Migrant Labor in the Persian Gulf. London: Hurst & Co.

- Kapiszewski, Andrzej. 2001. Nationals and Expatriates: Population and Labour Dilemmas of the Gulf Cooperation Council States. Reading: Ithaca Press.

- Khaleej Times. 2020. “FCCI to Reconsider Ties with in Countries Refusing to Receive Their Citizens.” Khaleej Times. https://www.khaleejtimes.com/uae/fcci-to-reconsider-ties-with-in-countries-refusing-to-receive-their-citizens-1.

- Korany, Bahgat. 1986. “Political Petrolism and Contemporary Arab Politics, 1967-1983.” Journal of Asian and African Studies 21 (1–2): 66–80.

- Korany, Bahgat, and Ali E. Hillal Dessouki, eds. 2008. The Foreign Policies of Arab States: The Challenge of Globalization. 3rd ed. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- Lori, Noora. 2019. Offshore Citizens - Permanent Temporary Status in the Gulf. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Malit, Froilan T., and Ali Al-Youha. 2013. “Labor Migration in the United Arab Emirates: Challenges and Responses.” https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/labor-migration-united-arab-emirates-challenges-and-responses.

- Malit, Froilan T., Knowles-Morrison Jenny, and Alexander Kristian. 2019. “Building Ethical Cultures in the Gulf Construction Sector: Implications on Corporations’ Quality Management.” In Embedding Culture and Quality for High Performing Organizations, edited by Norhayati Zakaria and Flevy Lasrado. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Malit, Froilan T., and George Naufal. 2016. “Asymmetric Information Under the Kafala Sponsorship System: Impacts on Foreign Domestic Workers’ Income and Employment Status in the GCC Countries.” International Migration 54 (5): 76–90.

- Martin, Philip L., and Froilan T. Malit. 2016. “A New Era for Labour Migration in the GCC?” Migration Letters 14 (1). https://search.proquest.com/openview/1e60651e2456fad138533aa7be1df665/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=456300.

- Migrant Forum in Asia. 2011. “Labour Recruitment to the Uae.” http://mfasia.org/migrantforumasia/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/mfa_recruitmentpaperfinal_jan2011.pdf.

- Migrant Forum in Asia. 2020. “MFA Visits UAE to Learn About New Initiatives on Migration | Migrant Forum in Asia.” 2020. https://mfasia.org/mfa-visits-uae-to-learn-about-new-initiatives-on-migration/.

- MOHRE. 2019. “MOHRE Implements a Program to Enhance Cultural Diversity in Labor Market.” https://www.mohre.gov.ae/en/media-centre/news/24/7/2019/%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%88%D8%B7%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%AA%D9%86%D9%81%D8%B0-%D8%A8%D8%B1%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%AC%D8%A7-%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B9%D8%B2%D9%8A%D8%B2-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%86%D9%88%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D9%82%D8%A7%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B3%D9%88%D9%82-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%85%D9%84.aspx.

- Nardello & Co. 2015. “Report of the Independent Investigator into Allegations of Labor and Compliance Issues During the Construction of the NYU Abu Dhabi Campus on Saadiyat Island, United Arab Emirates.” https://www.nardelloandco.com/wp-content/uploads/insights/pdf/nyu-abu-dhabi-campus-investigative-report.pdf.

- New Age. 2020. UAE labour market still closed to workers from Bangladesh. https://www.newagebd.net/article/99419/uae-labour-market-still-closed-to-workers-from-bangladesh.

- Norman, Kelsey P. 2020. “Migration Diplomacy and Policy Liberalization in Morocco and Turkey.” International Migration Review.

- Okruhlik, Gwenn, and Patrick Conge. 1997. “National Autonomy, Labor Migration and Political Crisis: Yemen and Saudi Arabia.” Middle East Journal 51 (4): 554–565.

- POEA. 2016. “Revised POEA Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Landbased Overseas Filipino Workers of 2016.” http://www.poea.gov.ph/laws&rules/files/Revised%20POEA%20Rules%20And%20Regulations.pdf.

- Reuters. 2016. “India Says to Bring Back Workers Facing “food Crisis” in Saudi.” https://www.reuters.com/article/us-india-saudi-workers-idUSKCN10B0B1.

- Rugh, Andrea. 2007. The Political Culture of Leadership in the United Arab Emirates. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ruhs, Martin. 2013. The Price of Rights: Regulating International Labor Migration. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Russell, Sharon Stanton. 1989. “Politics and Ideology in Migration Policy Formulation: The Case of Kuwait.” International Migration Review 23 (1): 24–47.

- Sabban, Rima. 2014. UAE Family Under Global Transformation. Zayed University Fellowship Programme. https://www.zu.ac.ae/main/en/research/publications/_books_reports/2014/UAE-Family-Under-Global- Transformation.pdf.

- Sabban, Rima. 2020. “From Total Dependency to Corporatisation: The Journey of Domestic Work in the UAE.” Migration Letters 17 (5): 651–668.

- Sallam, Sallam. 2019. “‘Shelters for Workers’ Forum launched in Dubai.” Arab24 News. http://arab24.news/shelters-for-workers-forum-launched-in-dubai/.

- Seccombe, Ian J. 1985. “International Labor Migration in the Middle East: A Review of Literature and Research, 1974-84.” International Migration Review 19 (2): 335–352.

- Seeberg, Peter, and Jan Claudius Völkel. 2020. “Introduction: Arab Responses to EU Foreign and Security Policy Incentives: Perspectives on Migration Diplomacy and Institutionalized Flexibility in the Arab Mediterranean Turned Upside Down.” Mediterranean Politics, May, 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2020.1758451.

- Segall, David, and Sarah Labowitz. 2017. Making Workers Pay: Recruitment of the Migrant Labor Force in the Gulf Construction Industry. New York, NY: NYU Center for Business and Human Rights.

- Shah, Nasra M. 2018. “Emigration Policies of Major Asian Countries Sending Temporary Labour Migrants to the Gulf.” In Migration to the Gulf: Policies in Sending and Receiving Countries, edited by Philippe Fargues and Nasra M. Shah, 125–150. Florence: European University Institute, Gulf Research Center.

- Thiollet, Hélène. 2011. “Migration as Diplomacy: Labor Migrants, Refugees, and Arab Regional Politics in the Oil-Rich Countries.” International Labor and Working-Class History 79 (1): 103–121.

- Thiollet, Hélène. 2019. "Immigrants, Markets, Brokers, and States: The Politics of Illiberal Migration Governance in the Arab Gulf." IMI Working Paper 155. Oxford: International Migration Institute.

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos. 2017. “‘Migration Diplomacy in the Global South: Cooperation, Coercion and Issue Linkage in Gaddafi’s Libya’.” Third World Quarterly 38 (10): 2367–2385.

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos. 2018. “Authoritarian Emigration States: Soft Power and Cross-Border Mobility in the Middle East.” International Political Science Review 39 (3): 400–416.

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos. 2019. The Politics of Migration in Modern Egypt: Strategies for Regime Survival in Autocracies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ulrichsen, Kristian Coates. 2016. The United Arab Emirates: Power, Politics and Policy-Making. New York: Routledge.

- Ulrichsen, Kristian Coates. 2020. Qatar and the Gulf Crisis: A Study of Resilience. London: Hurst & Co.

- United Arab Emirates. 2017. “Federal Law No. 10 of 2017 on Domestic Workers.” https://gulfmigration.org/database/legal_module/United%20Arab%20Emirates/National%20Legal%20Framework/Labour%20Migration/53.2%20Federal%20Law%20No%2015%20of%202017%20Domestic%20workers.pdf.

- United Arab Emirates. 2020. “The UAE’s Policy on Domestic Helpers.” https://u.ae/en/information-and-services/jobs/domestic-workers/uae-policy-on-domestic-helpers#:~:text=As%20per%20the%20Domestic%20Labour,including%208%20hours%20consecutive%20rest.

- Van Hear, Nicholas. 1998. New Diasporas: The Mass Exodus, Dispersal and Regrouping of Migrant Communities. London: University College London Press.

- Vitalis, Robert. 2007. America’s Kingdom: Mythmaking on the Saudi Oil Frontier. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Vora, Neha. 2013. Impossible Citizens: Dubai’s Indian Diaspora. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Walsh, Katie. 2009. “Geographies of the Heart in Transnational Spaces: Love and the Intimate Lives of British Migrants in Dubai.” Mobilities 4 (3): 427–445..

- Winckler, Onn. 2009. Arab Political Demography: Population Growth, Labor Migration and Natalist Policies. 2nd ed. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.