ABSTRACT

European governments widely celebrate and extensively fund ‘assisted voluntary return’ (AVR) programmes and assume that return counsellors play an important role for their implementation. At the same time, relevant legislation only vaguely defines this role and reduces it to a passive and neutral provision of ‘objective information’. In this article, we therefore ask how much and what kind of agency individual counsellors exercise and how this affects the aim and nature of AVR. We argue that counsellors fulfil a highly ambiguous function within a system that overall aims to bring unwanted migrants’ decision-making in line with restrictive immigration law. This function requires considerable autonomy to choose and use the various kinds of information they provide. We conceptualise their work as ‘aspirations management’ that mediates the ‘asymmetrical negotiation’ between precarious status migrants and the governments seeking to deport them. Based on original qualitative data from Austria and the Netherlands, we analytically distinguish three fundamentally different counselling strategies: facilitating migrants’ existing return aspirations, obtaining their compliance without aspirations, and/or inducing aspirations for return. This framework not only helps us to conceptualise AVR counsellors’ specific agency, but will also be useful for analysing how other actors manage the aspirations of unwanted non-citizens.

Introduction

So-called ‘assisted voluntary return’ (AVR) programmes have for several decades played a crucial role within European efforts to manage migration more effectively (Council of Europe Citation2010; EMN Citation2019). Initially set up as humanitarian policies facilitating the relocation of refugees to their countries of citizenship after cease of conflict (Vandevoordt Citation2017), contemporary AVR schemes primarily aim to encourage return among irregular migrants and (rejected) asylum seekers who at the same time face the more or less imminent prospect of deportation.Footnote1 The actual voluntariness of return under these circumstances has been rightly and extensively questioned (Lietaert Citation2016; Kalir Citation2017; Leerkes, van Os, and Boersema Citation2017; Vandevoordt Citation2017). Much less scholarly attention has been given to the concrete implementation of AVR policies and especially the role that AVR counsellors thereby play in terms of migration governance (Kuschminder Citation2017). Dedicated return counselling formally constitutes a key element of most AVR frameworks – including those of Austria and the Netherlands – and is being provided by either a state agency, non-state actors, or a combination of both (EMN Citation2019). It is widely assumed among government actors that return counsellors play an important role in acquiring the ‘voluntary return’ of unwanted non-citizens. At the same time, the relevant European and national legislation only vaguely define this role and reduce it to a passive and neutral provision of ‘objective information’ (Council of Europe Citation2010; EMN Citation2020). Return counsellors themselves, as the quote in the title of this article exemplifies, also tend to portray their work as merely assisting migrants by providing them with information they otherwise would lack (see also Loher Citation2020). An important aspect that remains to be explored in more detail is how much and what kind of agency individual counsellors exercise in their everyday work and how this affects the aim and nature of AVR.

In this article, we specifically look at the various ways in which state and non-state return counsellors in Austria and the Netherlands re/act upon potential returnees’ plans, wishes and concrete circumstances. We situate return counsellors as intermediary actors within one of many ‘spaces of asymmetrical negotiation’ between precarious status migrants and immigration authorities (Eule, Loher, and Wyss Citation2018). In the context of exclusionary migration governance, these negotiations often centre around the question of return. This makes the return counselling session a crucial site of governance, and return counsellors important actors who can directly intervene in and shape these negotiations by strategically selecting information they deem relevant and communicating it in particular ways. We conceptualise their interventions as a form of ‘aspirations management’ (Carling and Collins Citation2018), which aims at aligning migrants’ hopes and desires with usually adverse legal-political conditions and restrictive immigration law. A similar logic underlies the many information and awareness-raising campaigns through which Western governments try to discourage ‘potential irregular migrants’ from even attempting such a journey (Pécoud Citation2010; Watkins Citation2017). We argue that AVR counselling extends this logic of deterrence and discouragement from places of ‘origin’ and ‘transit’ to destination countries, and thereby relies on intermediary actors who actively engage in the ongoing negotiation of migrants’ precarious position vis-à-vis ‘the state’.

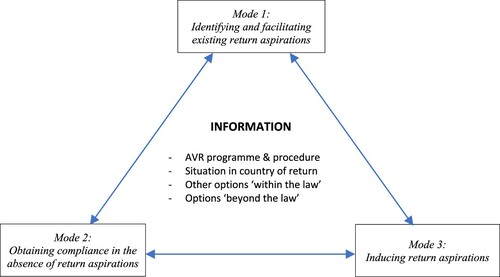

Our in-depth study draws on original qualitative data collected in Austria and the Netherlands, two countries with a long history of AVR policies but different institutional arrangements for the provision of return counselling. Primarily based on return counsellors’ personal accounts and our observations of their work, we identify three fundamentally different ways in which they understand their role in, and responsibility for, effectuating return. Each implies a different kind of engagement with ‘the law’ on the one hand and with migrants’ aspirations on the other. A return counsellor can (1) identify existing return aspirations and facilitate their realisation, (2) obtain compliance in the absence of return aspirations, and/or (3) aim at inducing return aspirations. Within each of these modes, return counsellors selectively combine and convey information on the available AVR programme, the situation in the country of return, alternative options within the law and those that lie ‘outside of’ the law. By tailoring this information to migrants’ concrete circumstances, they shape the aim and direction of return counselling which can, in principle, either support or undermine government efforts to exclude unwanted non-citizens.

Our article makes two contributions to the literature on the implementation of AVR policies and the governance of irregular migration more broadly. First, we highlight the significant autonomy and room for manoeuvre that individual return counsellors have in selectively combining different counselling strategies. Their choice partly depends on their own and their organisations’ ideological orientation, relative independence from the government, and their perception or official categorisation of potential returnees. Instead of trying to systematically explain when and why counsellors choose a particular mode, we argue that having this choice in the first place is precisely what enables them to mediate between migrants’ agency and state power. Importantly, none of the modes requires counsellors to bend the rules or work outside of the legal framework, since all of them are covered by their ambiguous mandate. As a second contribution, we provide a framework for further systematic analysis of not only return counselling practices but also other instances of return aspirations management across different countries, institutional settings and kinds of actors.

Managing aspirations within asymmetrical negotiations about deportation

Most non-citizens who become the target of ‘voluntary return’ policies and receive AVR counselling are also under a more or less imminent threat of deportation. This overlap led scholars to describe AVR as ‘soft deportation’ (Kalir Citation2017; Leerkes, van Os, and Boersema Citation2017), as a matter of ‘obliged voluntariness’ (Dünnwald Citation2008) or a ‘constrained choice’ (Lietaert Citation2016). As Leerkes, van Os, and Boersema (Citation2017, 8) note, AVR programmes rest always only partly on ‘voluntariness, facilitation and choice, while deterrence and force operate in the background’ (see also Lietaert, Broekaert, and Derluyn Citation2017). They follow Nye’s (Citation2004) differentiation between ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ power but understand these in terms of a ‘hard-to-soft continuum’ ranging from coercion to perceived legitimacy (Leerkes, van Os, and Boersema Citation2017, 6). The difference between the various modalities of power along this continuum is that in effectuating the law – in this case, a return order – implementing actors leave more or less room for compliance or resistance. Irregular migrants’ agency and strategies against exclusionary migration governance already received a lot of scholarly attention (e.g. Broeders and Engbersen Citation2007; Isin Citation2008; Ellermann Citation2010; Vasta Citation2011). Instead, this article focuses on the role that return counsellors – as a specific kind of implementing actors – play in mediating between migrants’ own preferences and the options immigration law prescribes for them. In order to better understand their crucial but ambiguous function, we conceptualise return counselling as an intervention in the asymmetrical negotiation over the rights and opportunities of precarious status migrants (Eule, Loher, and Wyss Citation2018) that takes the form of ‘migration aspirations management’ (Carling and Collins Citation2018).

Various scholars understand the implementation of immigration policy as a process of ongoing negotiation within a migration regime (Hess Citation2012; Eule, Loher, and Wyss Citation2018; Eule et al. Citation2019). Given the highly unequal distribution of power among the various actors of this regime, these negotiations are ‘asymmetrical’ (Eule, Loher, and Wyss Citation2018). At the same time, their outcome is often uncertain because they are based on a very complex, inherently ambiguous and frequently changing set of rules. Eule et al. (Citation2019, 5) argue that even when a final negative decision regarding an immigration case has been reached and the resulting obligation to return has been established, the actual implementation of ‘a deportation order is still a matter of negotiation, rather than enforcement’ (emphasis in original). The principal players in this particular negotiation are, on the one hand, migrants whose right to stay has been formally denied, and on the other hand, state authorities who as a result of this decision become responsible for their removal. In everyday practice, however, any such negotiation takes place within a broader and more complex ‘field [that] is shaped by a wide range of intervening actors, such as private companies, civil society groups, bureaucrats or supranational courts, which can enable or restrict migrants’ agency and a state's capacity to wield power’ (Eule, Loher, and Wyss Citation2018, 2717). As we will show, return counsellors find themselves in an ambiguous position, from which they can either enable migrants’ aspirations or state power, or try to do both at the same time, even though their official mandate is to remain neutral and objective.

Within these negotiations, ‘the law’ is being used in different ways and thereby becomes a ‘flexible tool’ that often ‘functions through informal knowledge transfers, rumours and various appropriations of black letter law’ (Eule et al. Citation2019, 9). Such flexibility is possible, and becomes necessary, because of the law's inherent ‘illegibility’: the fact that the state and its regulations are difficult to ‘read’ for both the people who are subject to these rules and those who implement them (Das Citation2004). In order for them to navigate the ‘messy’ character of the migration regime, they all rely on various kinds of knowledge, including informal ideas of the law, rumours and ‘oral traditions’ (Hagelund Citation2010; Eule Citation2016; Borrelli Citation2019). While Eule et al. (Citation2019) effectively show that particularly informal knowledge helps actors to navigate ‘spaces of asymmetrical negotiation’, we specifically focus on how intermediary actors within these spaces use formal and informal knowledge from a variety of sources in order to shape return decision-making.

According to Pécoud (Citation2010), contemporary migration management often involves ‘soft’ forms of control that rely on information technologies, advertising strategies and communication via traditional and social media. A well-known example for this kind of governing through information are state-led information campaigns in presumed countries of ‘origin’ and ‘transit’, which aim to prevent unwanted migration to Europe (Pécoud Citation2010; Schans and Optekamp Citation2016; Watkins Citation2017). The underlying idea is that providing purportedly ‘objective’ and ‘reliable’ information regarding the risks of unauthorised migration and residence will discourage aspiring migrants from even embarking on such a journey. Information campaigns thus promote self-governance and are based on the assumption that irregular migrants are ‘rational actors’ who simply lack adequate information and knowledge (Schans and Optekamp Citation2016). By providing such information – traditionally via flyers, posters, TV or radio adverts – governments want to divert potential migrants’ aspirations. Carling and Collins (Citation2018) therefore describe these campaigns as a form of ‘migration aspirations management’, through which states try to align migrants’ hopes and desires with existing legal-political conditions and opportunities. While these efforts mostly aim to prevent unwanted mobility in the first place, states have also used similar means to encourage migration among highly skilled migrants (Meyer Citation2018) or to trigger return among unwanted non-citizens already residing in Europe irregularly. In 2013 for example, the British government deployed several billboard-vans carrying the message ‘Go home or face arrest’ to neighbourhoods with the highest estimated numbers of unauthorised residents (Hattenstone Citation2018).

The actual effectiveness of such state-led campaigns is difficult to measure and remains highly contested (Tjaden, Morgenstern, and Laczko Citation2018), partly because irregular migrants and asylum seekers generally tend to mistrust receiving state governments as a direct source of information (Schans and Optekamp Citation2016). Instead, they tend to base their migratory decisions on what Eckert (Citation2012) has called ‘rumours of rights’, including anecdotal knowledge regarding pathways to regularisation, access to informal labour markets and other opportunities that at least partly lie ‘outside’ of the legal framework (Eule et al. Citation2019). This kind of information primarily travels ‘horizontally’ (Eckert Citation2012) through word-of-mouth, whereby complex legal knowledge is being filtered and transferred selectively in order to fit individual migrants’ specific circumstances and provide a better answer to their concrete migratory aspirations. Seen from this perspective, also return counselling works in a more horizontal way compared to classic information campaigns. Importantly, this horizontal way of working is what enables individual counsellors to provide only those bits of information that they deem appropriate to a particular migrant's situation and see as conducive to their decision-making. Similar to ‘rumours of rights’, which according to Eckert (Citation2012, 152) ‘are not always rumours of hope, but often of fear’, return counsellors can use information not only to trigger migrants’ hopes for a ‘better life at home’, but also their fear of destitution, marginalisation, detention or deportation. While their official mandate is to provide objective information, and thereby reduce the illegibility of the law, counsellors in fact often use only bits of that information to influence migrants’ decision-making. Since they are ultimately unable to make the law itself more legible, counsellors can only encourage unauthorised migrants to read and interpret it in one particular way.

Cases, context and methods

The empirical basis for this article comes from two independent research projects driven by a common research interest: to better understand the often simplified role that individual counsellors play within contemporary AVR systems. Following the logic of a multiple case study approach (Greene and David Citation1984), our study draws on equivalent, in-depth field data collected in Austria (between April and August 2019) and the Netherlands (between January and June 2017). The two AVR systems we look at exhibit a wide range of return counselling settings and actors, and thus provide a useful starting point for developing a framework for more systematic analysis of return aspirations management. Both countries’ governments are bound by the EU Return Directive and spend significant effort and money to make AVR available to non-citizens at any stage of their asylum or immigration procedure, as well as in detention. Return counselling is an obligatory part of the asylum procedure and starts well before a final decision is reached. Only if a recipient agrees to return, the counsellor completes an application for cash and/or in-kind assistance to be provided by the government.

While their AVR procedures are very similar, the two countries differ in terms of the institutional set-up and involved actors. In Austria, return counselling is funded by the state and provided by non-profit NGOs.Footnote2 The first major AVR programme (Rückkehrhilfe) was set up in December 1998 by Caritas, in cooperation with the European Commission, the Interior Ministry (BM.I) and IOM Austria. Since 2003, there is a second provider of return counselling, called Verein Menschenrechte Österreich (VMÖ), which has frequently been criticised for its close relationship with the BM.I (Pferschinger Citation2011). In addition to these two major players, a number of smaller NGOs also provide return counselling to more specific target groups (like victims of human trafficking) or as part of their broader advice work that they often call Perspektivenabklärung (clarification of prospects). In the Netherlands, IOM and the central government started providing AVR counselling in 1991. Since 2007, a specialised organisation within the Ministry of Justice and Security called the Repatriation and Departure Service (DT&V) is in charge of the return programme. DT&V counsellors work on the basis of case management and direct migrants who agree to return to IOM or state-sponsored non-profit NGOs, or otherwise initiate forced removal proceedings against them. The NGOs that provide counselling range from ‘state subcontractors’ to organisations questioning the goal of returning rejected asylum seekers but nevertheless operate within the same policy framework (Kalir and Wissink Citation2016). Similar to the Perspektivenabklärung in Austria, these NGOs present this part of their work – called toekomstoriëntatie – as an open discussion on migrants’ prospects and hopes for their future, not limited to return alone. The performance of state-funded NGOs in both countries is primarily measured by the number of counselling sessions they provide, rather than the number of resulting returns.

Fieldwork carried out in Austria mainly comprised a total of 28 semi-structured interviews with actors involved in the making and implementation of AVR policies: senior officials in the responsible ministry and its operative branch (the Federal Agency for Immigration and Asylum), representatives of IOM Austria and the two major providers of return counselling, legal advisors, asylum support workers and representatives of local advocacy groups. The interviewees’ original accounts were complemented with non-participant observation of several hours of return counselling sessions at both major counselling organisations. In the Netherlands, 18 in-depth interviews were conducted with 20 NGO return counsellors, who work in eleven different municipalities throughout the country. Data on the DT&V were collected during eleven working days through informal interviews with 30 officials and observations during counselling sessions, lunches and training sessions. Throughout our fieldwork, and without hiding our critical perspective, we both tried to get as close as possible to our research participants to familiarise ourselves with their perspective, concrete working environments and day-to-day challenges. We feel that this helped us to gain their trust and encourage them to talk freely about their aims and motivations, personal opinions on migration policy and their own strategies for achieving a ‘voluntary return’. At the same time, this approach also implies limitations. Most importantly, our focus on how return counsellors manage migrants’ return aspirations means that our analysis is primarily based on their narratives, practices and strategies. Our data did not allow us to systematically triangulate these findings with migrants’ experiences of counselling. We therefore refrain from making claims about its actual impact on their return decision-making.

All formal interviews were audio-recorded and fully transcribed, while observational data were processed into field reports. This material was anonymised, received the respondents’ approval and subsequently translated by the authors from either German or Dutch to English. In addition, we also reviewed relevant legislation, policy documents, parliamentary inquiries, press statements and other official proclamations by political actors with regard to return. We then analysed our data thematically, following an iterative approach. As a first step, we independently examined the data on each case to identify concrete counselling strategies. Then we discussed apparent similarities between the two countries and across the different organisations, which resulted in a preliminary coding scheme. Instead of drawing a definite line or comparison between the two countries or between state- and non-state counsellors, our aim was to identify ‘explanatory patterns’ (Greene and David Citation1984) that characterise the practice of return counselling more generally. Further inductive analysis and refinement of our coding scheme ultimately led to our analytical distinction between three modes of return counselling. The benefit of such a multiple case study approach is that it ‘preserves the essential wisdom of the case study approach (i.e. understanding how and why events occur in their natural context)’, but also ‘allows […] to judge the extent to which conclusions can be generalised to other persons, places and times’ (ibid, 74). The next section outlines our analytical framework and presents our empirical data.

Three modes of return counselling and their common basis: ‘objective’ information

Return counselling is always premised on the assumption that potential returnees lack certain information that they should have in order to make a decision regarding their return. For analytical purposes, we distinguish four types of information that return counsellors tend to provide during return interviews: (1) information on the available AVR programme and reintegration assistance, (2) information concerning the situation in the migrants’ country of nationality, (3) information on other options ‘within the law’ (like appeal rights and legal avenues for regularisation) and (4) on options ‘outside the law’ (like irregular residence). presents a schematic representation of how we conceptualise return counselling: as a flexible combination of three very different strategies that draw on the same body of information.

It is important to note that in principle, return counsellors can prioritise or resort to any one of these three modes of return counselling, or selectively combine them, whereby their choice of modes is mostly a response to the concrete situation at hand. For example, the counselling strategy will depend on a potential returnee's alleged country of nationality (including official and subjective assessments of safety in that country), their individual circumstances (e.g. family composition or health situation) and administrative status (e.g. asylum seeker or rejected asylum seeker). The latter will also determine the concrete setting in which counselling takes place, which can be an NGO office, state-run reception facility or detention centre. While most counselling sessions involve all four types of information presented above, there are notable differences between the three modes in terms of how this information is presented and how much weight is given to each type. Information on the available reintegration assistance, for example, can be provided as a way to facilitate already existing return aspirations (mode one), a concrete incentive that should induce such aspirations (mode three) or merely as part of the prescribed return procedure (mode two). In the following three subsections, we use selected empirical evidence to describe each mode in more detail.

Mode 1: Identifying and facilitating existing return aspirations

In both countries, some return counsellors portray their work as being primarily concerned with those relatively few migrants who approach them with an apparent wish to return. In Austria, this was true for counsellors working for either of the two main providers, who frequently made statements like the following:

We are not here to change someone's mind, but the person has to know what s/he wants. If s/he wants [to return] and really has made this decision for herself or for the family, then they go. So, we cannot change anyone's mind nor force anyone, right? We are here to advise (return counsellor, VMÖ).

Once counsellors identify a wish to return, they often focus on speeding up the process in order to reduce the chance of the migrant changing his or her mind. This logic of ‘quick returns’ is clearly reflected in the DT&V's official methodology for return counselling (see also Cleton and Chauvin Citation2020). A concrete example used in their training is when a return flight is booked too far in advance, giving potential returnees time to re-think their decision. In Austria, where no official guidelines exist, the same concern was not only expressed by state officials, but also by a representative of VMÖ:

We have very much geared our return procedure towards speed, which means we make every effort to ensure that the return actually happens as soon as possible. And that also has to do with the fact that the clients - if it takes too long to prepare their return - may then come up with other options and perhaps go to Germany illegally, which really does not help anyone. A quick return also has the consequence of saving accommodation costs and other costs.

We are not telling someone from Afghanistan: ‘just go back’, but they need to convince me twice that they want to return. I had a young guy the other day, and he told me he wants to return, but I say, ‘yes, but what's your motivation?’ And he says ‘well, if I die here or there, that doesn't matter’. And I told him ‘I don't think that that is a motivation if you tell me that you will die within three days of your return, I really don't want that to happen.’

Personally, I do not think that [return counsellors] can advise against return, because the asylum seeker knows best what is actually going on in the home country. […] If the person makes that decision, then it is the return counsellor's job to accept that and to organise all that is necessary, like flights etc. It is not the role of the counsellor to say: ‘don't do it’.

In principle, good counselling is when someone who wants to leave voluntarily, leaves, right? Where he is sure that no problems are to be expected, and he is really determined. It is worse when you have to confront someone with a return because that is how the laws are and we cannot do anything about it, but the person is not willing to return. I sometimes think the people do not want to see the truth.

Mode 2: Obtaining compliance in the absence of return aspirations

The vast majority of the people who receive return counselling do not wish to return to their country of nationality. Faced with such cases, return counsellors sometimes merely work towards obtaining their compliance with a return that they present as unavoidable. Counsellors thereby privilege information ‘within the law’ – including the available assistance and likelihood of deportation – without addressing the individual returnee's aspirations or desires. For them, the previously issued return order implies that there is no room for compromise or necessity to show empathy or even engage with migrants’ own hopes and desires. Sometimes they openly disregard migrants’ lack of return aspirations and arguments against having to leave, as the following excerpt from field notes taken while observing a return interview between a DT&V counsellor and a detainee exemplifies:

The man, an Indian national, starts telling the DT&V caseworker about his depression, anxiety and feelings of ‘losing himself’. The case worker quickly intervenes and tells him that he does not want to hear about all of this, as it is not important. The only thing that is important to him, he explains, is that the man told him earlier that he does not want to cooperate on return, while he has a legal obligation to leave the Netherlands.

When this was introduced, it was a very difficult issue for us, because something that is obligatory … is difficult to combine with our notion of ‘voluntariness’. But then we looked at it very closely and then said, ‘OK: if someone is obliged to get some information then at the end of the day, he simply has more information’.

One way of obtaining compliance is by emphasising the possibility of deportation as a legitimate way of enforcing a legal obligation to return. A DT&V counsellor explained that her efforts to achieve a ‘voluntary return’ generally were minimal for nationals of EU countries and so-called ‘safe country of origin’: ‘we offer them a voluntary return from the centre, but if they refuse, we are not going to convince them, as deportation is easily possible’. NGO counsellors, in contrast, tended to struggle more with having to discuss the threat of deportation:

If the [client] says she doesn't want to leave, I will not … convince her of a voluntary return. But if [the procedure] is already at the point where it's clear, and we cannot do anything […] then I can only say: ‘there is a possibility that you will be deported, and that is quite real, and there is the possibility to leave voluntarily’, but not in the sense of one being better than the other, but: ‘these are your options’ (NGO counsellor Austria).

Precisely because migrants are often exposed to a multiplicity of information and contradictory advice from different sources, return counsellors are expected to be clear about complex legal cases and their uncertain outcomes. This complexity makes it even more difficult to draw a line between counselling and persuasion, as a senior official of the Austrian Interior Ministry tried to do:

If a return counsellor says: ‘[…] the probability of success is very low; this is not going to work. […] I would advise you to return because in the end that's what is going to happen either way.’ That is probably what I would find okay and appropriate, that the perspectives are made clear. That would not be persuasion for me. […] As soon as an element of pressure would occur, that would of course not be okay because it would simply take the element of voluntariness ad absurdum.

Mode 3: Inducing return aspirations

Our third mode of return counselling is characterised by practices of actively trying to induce a desire to return, in the absence of pre-existing return aspirations. Particularly when deportation is impossible – as it often is due to legal or practical constraints -, this is the only way to effectuate a return order. While this mode is prevalent across all organisations, it is particularly well reflected in the DT&V's methodological guidelines. They start from the premise that ‘behaviour can always be influenced’ (DT&V Citation2018) and that the primary goal of counselling is to do exactly this. DT&V counsellors therefore apply a variety of ‘motivational interviewing techniques’ to ‘motivate a foreigner [to make] an informed decision about his or her return to their country of origin’ (ibid.). While no such formal guidelines exist in Austria, also there it is believed that return counselling is of vital importance for acquiring a ‘voluntary return’. For example, the legislative proposal for the 2017 immigration reform stressed that

return advice organisations can also repeatedly offer the foreigner a return counselling interview. This takes account of the fact that foreigners who have already clearly stated that they are unwilling to leave […] have an increased need for return counselling and [the proposal] pursues the purpose of increasing the willingness to leave the country also among these foreigners by means of intensified return counselling.

is based on a connection, or a bond, that I aim to make with the foreigner and is geared towards getting mutual trust, understanding and respect. The benefits of getting this relation very early on in the return process is that my clients will understand that I am here to help them. If they believe that this is the case already in the beginning of our conversations, when return is often not discussed extensively, they will also believe that I want what is best for them when the prospect of return becomes more real.

In order to be able to induce return aspirations, counsellors not only need to establish trust but also present the situation as one where potential returnees have several options to choose from. Interviewees in both countries therefore portray their work as a matter of ‘coaching’, rather than enforcing a decision already taken by the government or court:

Ideally, a return counsellor would be more like a coach […] who helps you to make a decision within your own reality, which the coach himself does not influence, but he tells you: ‘Did you look at this? Did you look at that? And what happens if you look at the two things?’ That would be my idea of return counselling (representative of IOM Austria).

think about the future of your two daughters. Yes, they are still underage now and can attend school and have a right to reside at the [reception] centre, but what will you do after they become 18? Perhaps it is better if you start considering returning to Iraq now and build a better future for them there.

My take on the matter is always to give honest information about chances for legal residence here, and possibilities of survival without a residence permit. We will in any case explain what their rights are, so the right to medical care and so on, but also tell them that they should not expect that the Dutch government or charity organisations will support them forever. So, we urge them to make a plan for themselves, if they want to stay here without papers (Dutch NGO return counsellor).

Another important strategy that counsellors use to induce return aspirations is framing return as a precondition for being able to accomplish broader life aspirations. Return counsellors in both countries point to the possibility of acquiring legal status through family reunification, but since migrants need to make such claims from their countries of nationality, they first have to return. In a similar way, a DT&V counsellor who found out that an Iraqi woman wanted to become an engineer, immediately supported this wish by offering to help her prepare the university application and suggested that the reintegration assistance could be used to finance this education. In both countries, many counsellors noted that being able to offer reintegration assistance generally makes their job easier. They also supported the idea that increasing the amount of reintegration assistance would make AVR programmes more effective, although the available empirical evidence on this issue is inconclusive (Koser and Kuschminder Citation2015; Leerkes, van Os, and Boersema Citation2017). Reintegration assistance is also presented to migrants as a way to foster future legal re-migration to Europe, for example by means of acquiring a labour- or student visa based on their successful businesses or education funded through the AVR scheme. Negative consequences of not choosing a ‘voluntary return’, such as a re-entry ban, are instead mentioned as a barrier to realising longer-term plans that are premised upon re-migration to Europe. Overall, what characterises mode three is that counsellors actively steer migrants towards choosing AVR as ‘the right decision for themselves’. This at the same time helps individual counsellors to understand return as a win-win situation and thereby justify their own active involvement.

Together, the three modes show that return counselling entails a wide range of strategies. While it is difficult to draw a definite line between ‘state’ and ‘non-state’ providers of return counselling, there are notable differences between DT&V and NGO counsellors in the Netherlands, which to some extent mirror those between VMÖ and Caritas in Austria. While this suggests that distance from the government and the institutional setup of AVR systems affect counselling practices, a striking commonality is precisely the far-ranging agency and discretion that individual return counsellors have in general.

Discussion and conclusion

In this article, we investigated how return counsellors and other relevant actors of the Austrian and Dutch return regimes understand the role that counselling plays in relation to migrants’ aspirations and state power. We started from the observation that governments widely celebrate and extensively fund AVR as part of their efforts to govern unwanted migration, but thereby often simplify the role of individual counsellors as neutral providers of ‘objective information’. The question we therefore tried to answer was what exactly it is that return counsellors do when they assist migrants in making a ‘well-informed decision’ regarding their return and how they themselves understand their role in shaping this decision-making process. We thereby situate return counsellors as intermediary actors in ‘asymmetrical negotiations’ (Eule, Loher, and Wyss Citation2018) about the interests of deporting states on the one hand and migrants’ own hopes, desires and expectations on the other. In order to make sense of the notable variety of practices that counsellors described and that we observed during counselling sessions, we analytically distinguish three modes of return counselling. According to this differentiation, counsellors manage unwanted migrants’ return aspirations in three fundamentally different ways: by facilitating existing aspirations, obtaining compliance without such aspirations or by actively inducing them. As they strategically choose between or combine these modes, counsellors give more or less room to migrants’ own plans and visions for the future, and thereby shift the balance between ‘migrants’ agency and a state's capacity to wield power’ (Eule, Loher, and Wyss Citation2018, 2717). Mode one, which we found most common among NGO counsellors, primarily aims at facilitating migrants’ agency rather than state power. Mode two, in contrast, is focused on compliance with state power and leaves very little room for migrants’ own agency and preferences. Unsurprisingly, it is mostly used by state counsellors and those working for organisations closely related to the government. Mode three is employed across all kinds of organisations and aims at enabling migrant agency in a way that also enables the exercise of state power.

Within each of these modes, counsellors assemble different pieces of information that they deem appropriate to a particular migrant's situation and see as conducive to their decision-making. While their official mandate is to provide objective information, and thereby reduce the ‘illegibility of the law’ (Das Citation2004), counsellors in fact often emphasise or blind out certain bits of information to make migrants read and interpret the law in a particular way. This filtering and tailoring of information does not require counsellors to bend the rules or work outside of the legal framework but is part and parcel of their ambiguous function. By nevertheless embracing their officially prescribed role as ‘neutral’ providers of ‘correct and clear-cut’ information, they do not make the law itself more legible but contribute to upholding the myth of a smoothly functioning migration bureaucracy. Importantly, counselling sessions are characterised by a clear hierarchy between the counsellor who is in charge of the conversation and the migrant who merely receives the information s/he supposedly needs. Despite this clear power imbalance, however, knowledge is transferred in a more ‘horizontal’ way (Eckert Citation2012), which relies on direct communication, requires a significant level of trust and allows information to be tailored to the recipient's concrete circumstances. Notably, recent information campaigns against irregular migration also increasingly involve ‘trained counsellors who deliver one-on-one consultation with migrants’ in order to ‘discover and address migrants’ unique motivations and understanding as well as their information needs’ (Seefar Citationn.d., 33). From a government perspective, this should make the dissemination of information more effective, but it also introduces additional actors to the process of managing unwanted migration. As our empirical data show, AVR counsellors have their own interests, interpretations and discretion over what happens during counselling sessions. Arguably, a more horizontal transfer of knowledge thus inevitably means a more indirect modality of government that gives intermediary actors considerable autonomy in providing the basis upon which migrants should take their ‘well-informed decisions’.

Apart from helping us to conceptualise the agency of return counsellors working in Austria and the Netherlands, we hope that our analytical framework will also be used for further and more systematic analysis of return counselling in and across other countries and institutional settings. In addition, we hold that the same framework is also applicable to other instances of return aspirations management that involve different kinds of actors, such as legal advisers, social workers, staff at reception facilities or private supporters. Arguably, all of them try to ‘help migrants assess their migration options and help them make smart choices – although it remains unclear what is defined as a ‘smart choice’’ (Schans and Optekamp Citation2016, 15). Even if these actors tend to position themselves on the migrants’ side of the negotiation, they are still – just like AVR counsellors – involved in ‘softly’ governing migrants’ choices through the never completely objective information they convey.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to all return counsellors and other respondents who agreed to participate in our research and to share their experiences. This article was previously presented at the ACES ‘Stay, move-on, return: Dynamics of mobility aspirations in contexts of forced displacement’ workshop on 6–7 November 2019 at the University of Amsterdam and the Annual IMISCOE Conference on 1–2 July 2020 (online). A previous version of the article has been published as an International Migration Institute (IMI) Working Paper (no. 160). We would like to thank all workshop and conference participants and the IMI editors for their fruitful comments and suggestions. Finally, we are indebted to Anna Wyss, Elsemieke van Osch, Robin Vandevoordt, Mieke Kox, Sieglinde Rosenberger and two anonymous reviewers, for their generous feedback and engagement with this article. All remaining mistakes are our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In the remainder of this article, we refer to these groups as ‘unwanted non-citizens’: they are ‘unwanted’ in the sense that the government either challenges or has already denied them the right to remain.

2 Note that since January 2021, a newly established state agency is exclusively responsible for providing return counselling.

References

- Borrelli, L.-M. 2019. “The Border Inside - Organizational Socialization of Street-Level Bureaucrats in the European Migration Regime.” Journal of Borderlands Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2019.1676815.

- Broeders, D., and G. Engbersen. 2007. “The Fight Against Illegal Migration: Identification Policies and Immigrants’ Counterstrategies.” American Behavioral Scientist 50 (12): 1592–1609.

- Carling, J., and F. Collins. 2018. “Aspiration, Desire and Drivers of Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 909–926.

- Cleton, L., and S. Chauvin. 2020. “Performing Freedom in the Dutch Deportation Regime: Bureaucratic Persuasion and the Enforcement of ‘Voluntary Return’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (1): 297–313.

- Council of Europe. 2010. Voluntary Return Programmes: An Effective, Humane and Cost- effective Mechanism for Returning Irregular Migrants. Report to the Committee on Migration, Refugees and Population, Doc. 12277, 4 June 2010.

- Das, V. 2004. “The Signature of the State: The Paradox of Illegibility.” In Anthropology in the Margins of the State, edited by V. Das, and D. Poole, 225–252. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- DT&V. 2018. “Wat is Werken in Gedwongen Kader?” Vreemdelingenvisie 05, September 2018. https://www.vreemdelingenvisie.nl/vreemdelingenvisie/2018/05/leg-mij-uit.

- Dünnwald, S. 2008. Angeordnete Freiwilligkeit. Zur Beratung und Förderung Freiwilliger und Angeordneter Rückkehr Durch Nichtregierungsorganisationen in Deutschland. München: Förderverein PRO ASYL e.V.

- Eckert, J. 2012. “Rumours of Rights.” In Law Against the State: Ethnographic Forays Into Laws Transformations, edited by J. Eckert, B. Donahoe, C. Strümpell, and ZÖ Biner, 147–170. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Eggebø, H. 2013. “‘With a Heavy Heart’: Ethics, Emotions and Rationality in Norwegian Immigration Administration.” Sociology 47 (2): 301–317.

- Ellermann, A. 2010. “Undocumented Migrants and Resistance in the Liberal State.” Politics & Society 38 (3): 408–429.

- EMN. 2019. Policies and Practices on Return Counselling for Migrants in EU Member States and Norway - EMN Inform. Brussels: European Migration Network.

- EMN. 2020. Policies and Practices on Outreach and Information Provision for the Return of Migrants in EU Member States and Norway - EMN Inform. Brussels: European Migration Network.

- Eule, T. G. 2016. Inside Immigration Law: Migration Management and Policy Application in Germany. London: Routledge.

- Eule, T. G., L.-M. Borrelli, A. Lindberg, and A. Wyss. 2019. Migrants Before the Law. Contested Migration Control in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eule, T. G., D. Loher, and A. Wyss. 2018. “Contested Control at the Margins of the State.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (16): 2717–2729.

- Greene, D., and J. L. David. 1984. “A Research Design for Generalizing From Multiple Case Studies.” Evaluation and Program Planning 7: 73–85.

- Hagelund, A. 2010. “Dealing with the Dilemmas: Integration at the Street-Level in Norway.” International Migration 48 (2): 79–102.

- Hattenstone, S. 2018. “Why was the scheme behind May’s ‘Go Home’ vans called Operation Vaken?” The Guardian, 26 April 2018. Available here: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/apr/26/theresa-may-go-home-vans-operation-vaken-ukip.

- Hess, S. 2012. “De-naturalising Transit Migration. Theory and Methods of an Ethnographic Regime Analysis.” Population, Space and Place 18 (4): 428–440.

- Isin, E. F. 2008. “Theorizing Acts of Citizenship.” In Acts of Citizenship, edited by E. F. Isin, and G. M. Nielsen, 15–43. London: Zed.

- Kalir, B. 2017. “Between ‘Voluntary’ Return Programs and Soft Deportation: Sending Vulnerable Migrants in Spain Back ‘Home’.” In Return Migration and Psychosocial Wellbeing: Discourses, Policy- Making and Outcomes for Migrants and Their Families, edited by Z. Vathi, and R. King, 56–71. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kalir, B., and L. Wissink. 2016. “The Deportation Continuum: Convergences Between State Agents and NGO Workers in the Dutch Deportation Field.” Citizenship Studies 20 (1): 34–49.

- Khosravi, S. 2009. “Sweden: Detention and Deportation of Asylum Seekers.” Race & Class 50 (4): 38–56.

- Koser, K., and K. Kuschminder. 2015. Comparative Research on the Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration of Migrants. Geneva: IOM.

- Kuschminder, K. 2017. “Interrogating the Relationship Between Remigration and Sustainable Return.” International Migration 55 (6): 107–121.

- Leerkes, A., R. van Os, and E. Boersema. 2017. “What Drives ‘Soft Deportation’? Understanding the Rise in Assisted Voluntary Return Among Rejected Asylum Seekers in the Netherlands.” Population, Space and Place 23 (8): 2059–2070.

- Lietaert, I. 2016. “Perspectives on Return Migration: A Multi-Sited, Longitudinal Study on the Return Processes of Armenian and Georgian Migrants”. Unpublished doctoral thesis. Ghent: Ghent University.

- Lietaert, I., E. Broekaert, and I. Derluyn. 2017. “From Social Instrument to Migration Management Tool: Assisted Voluntary Return Programmes – The Case of Belgium.” Social Policy & Administration 51 (7): 961–980.

- Loher, D. 2020. “Governing the Boundaries of the Commonwealth. The Case of So-Called Assisted Voluntary Return Migration.” In The Bureaucratic Production of Difference. Ethos and Ethics in Migration Administrations, edited by J. M. Eckert, 113–134. Wetzlar: Majuskel Medienproducktion GmbH.

- Meyer, F. 2018. “Navigating Aspirations and Expectations: Adolescents’ Considerations of Outmigration from Rural Eastern Germany.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 1032–1049.

- Nye, J. 2004. “Soft Power and American Foreign Policy.” Political Science Quarterly 119 (2): 255–270.

- Pécoud, A. 2010. “Informing Migrants to Manage Migration? An Analysis of IOM’s Information Campaigns.” In The Politics of International Migration Management, edited by M. Geiger, and A. Pécoud, 184–201. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pferschinger, S. 2011. “Unabhängige Beratung von AsylwerberInnen in Österreich?”. Unpublished master thesis. Vienna: University of Vienna.

- Schans, D., and C. Optekamp. 2016. Raising Awareness, Changing Behavior? Combating Irregular Migration Through Information Campaigns. The Hague: Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek- en Documentatiecentrum (WODC), Ministerie van Veiligheid en Justitie.

- Seefar. n.d. 3E Impact Ethical, Engaged & Effective. Running Communications on Irregular Migration from Kos to Kandahar. Hong Kong: Seefar.

- Tjaden, J., S. Morgenstern, and F. Laczko. 2018. “Evaluating the Impact of Information Campaigns in the Field of Migration: A Systematic Review of the Evidence and Practical Guidance.” In Central Mediterranean Route Thematic Report Series. Geneva: International Organization for Migration.

- van der Kist, J., and D. Rosset. 2020. “Knowledge and Legitimacy in Asylum Decision-Making: The Politics of Country of Origin Information.” Citizenship Studies 24 (5): 663–679.

- Vandevoordt, R. 2017. “Between Humanitarian Assistance and Migration Management: on Civil Actors’ Role in Voluntary Return from Belgium.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (11): 1907–1922.

- Vasta, E. 2011. “Immigrants and the Paper Market: Borrowing, Renting and Buying Identities.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 34 (2): 187–206.

- Watkins, J. 2017. “Australia’s Irregular Migration Information Campaigns: Border Externalization, Spatial Imaginaries, and Extraterritorial Subjugation.” Territory, Politics, Governance 5 (3): 282–303.