ABSTRACT

The non-governmental organizations (NGOs) rescuing migrants off the coast of Libya have been increasingly criminalised. We investigate the discursive underpinnings of this process by analyzing all the articles on sea rescue NGOs published between 2014 and 2019 by two major Italian newspapers located at opposite sides of the political spectrum: Il Giornale and La Repubblica. Our discourse analysis shows that the media salience of non-governmental sea rescue increased enormously following the first public allegations against humanitarians and peaked in 2019 after some standoffs between some NGOs and the Italian government, when the number of migrants rescued at sea had already dropped to a minimum. This inflated and heavily politicised media coverage contains both direct and indirect criminalisation discourses. Though sometimes directly accused of colluding with human smugglers and profiting from irregular migration, sea rescue NGOs have more often been indirectly criminalised through the same framing devices typically used to stigmatise irregular mobility at large, namely associational links, metaphors, frame-jacking, and othering.

1. Introduction

Non-governmental organizations (NGOs) operating at borders worldwide have increasingly been accused of threatening national security by aiding irregular migration, prompting state authorities to introduce a variety of restrictive measures aimed at ‘policing humanitarianism’ (Carrera et al. Citation2019). The NGOs conducting maritime search and rescue (SAR) in the Mediterranean Sea have suffered especially heated criticism in Italy, where prominent politicians referred to NGOs operating off the coast of Libya as ‘pirates’ and ‘sea taxis’ for irregular migrants. By the summer of 2017, the allegation that sea rescue NGOs acted as a pull factor of illegal immigration or were in cahoots with human smugglers had escalated into judicial indictments and policy restrictions on non-governmental SAR, causing several organisations to suspend their operations.

The criminalisation of migration, defined as ‘all the discourses, facts and practices … that hold immigrants/aliens responsible for a large share of criminal offences’ (Palidda Citation2011, 23), has received substantial academic attention (Brouwer, Van der Woude, and Van der Leun Citation2019; Perkowsky and Squire Citation2019; Quassoli Citation2013). Scholars have also increasingly investigated the criminalisation of those assisting asylum seekers. Recent studies have examined the legal and normative implications of European governments’ ongoing efforts to criminalise solidarity both on land and at sea (Basaran Citation2015; Carrera et al. Citation2019; Fekete Citation2018). Several scholars have conceptualised these efforts as part of a broader attempt to enforce more restrictive border policies (Moreno-Lax Citation2018; Tazzioli Citation2018). Other have empirically examined the activities of sea rescue NGOs (Cusumano Citation2021; Cuttitta Citation2018; Irrera Citation2019; Stierl Citation2018) and questioned the existence of a correlation between SAR operations and irregular departures from Libya (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020). No study to date, however, has systematically examined the linguistic strategies used to frame sea rescue NGOs as directly committing or indirectly facilitating criminal activities, a process we refer to as discursive criminalisation.

Both television and newspapers have often framed migration as a ‘crisis meriting political action and resolution’ (Caviedes Citation2015, 900). According to several scholars, media play a key role in setting the agenda of asylum and border policies, and their negative framing of human mobility has enabled a growing criminalisation of migration (Parkin Citation2013; Vollmer Citation2011). Scholarship on the criminalisation of humanitarian actors assisting migrants has already noted the connection between ‘a shift in rhetoric and a shift in policing practices’ (Allsopp, Vosyliūtė, and Smialowski Citation2020, 1). While several works have examined media coverage of irregular migration to Italy (Barretta et al. Citation2017; Berry, Garcia-Blanco, and Moore Citation2016; Quassoli Citation2013; Urso Citation2018), no study focuses specifically on the discursive criminalisation of non-governmental rescue operations. Existing scholarship has only briefly examined reactions to the 2018 standoff between the Italian government and SOS-Méditerranée’s Aquarius (McDowell Citation2020) and statements made by Italian politicians (Berti Citation2020; Colombo Citation2018), prosecutors, and European Union (EU) agencies like Frontex (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020).

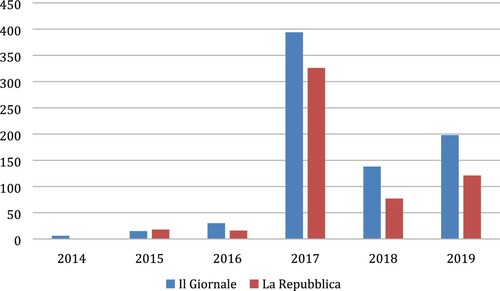

In this article, we fill this gap by answering the following research question: how do Italian media frame sea rescue NGOs and their operations, and how does this framing vary across media outlets and over time? To this end, we examine the media coverage of non-governmental SAR between 2014 and 2019 by coding all the articles on sea rescue NGOs published by two major Italian newspapers positioned at opposite sides of the political spectrum: Il Giornale and La Repubblica. Our analysis, which comprises 1565 articles and almost 900,000 words in total, identifies both direct and indirect discursive criminalisation devices. Criminalisation in a narrow sense, consisting of direct accusations of unlawful behaviour, was mainly confined to the right-wing outlet. Both the conservative and (albeit to a much lesser extent) the progressive paper, however, have indirectly contributed to the criminalisation of humanitarianism through four framing devices: associational links, metaphors, frame-jacking, and othering processes.

These findings provide an empirical, policy-relevant, and theoretical contribution. First, our study adds to the scholarship on media framing of irregular migration and humanitarianism, providing insights into what informs public perceptions of NGOs. Advancing empirical knowledge of these issues is relevant from policy and normative perspectives. Since NGOs have played a crucial role in rescuing migrants off the coast of Libya, discursive criminalisation strategies that hinder their legitimacy and access to the humanitarian space may severely impact human security at sea, exacerbating the risks attached to irregular mobility across the Mediterranean. Last, a systematic analysis of newspapers’ coverage of NGOs’ activities provides novel theoretical insights into the criminalisation of solidarity, its variance across media outlets, and its diachronic evolution. Relatedly, identifying the discursive strategies used to criminalise sea rescue NGOs sheds new light on the discursive underpinnings of the governing of indifference, namely the processes through which people are prompted to becoming indifferent towards the plight of irregular migrants and others in general (Basaran Citation2015).

The article proceeds as follows: section two outlines the importance of media framing in the context of migration, before drawing on scholarship on the securitisation and criminalisation of migration to identify the key framing devices deployed to stigmatise irregular border crossing. Section three explains our methodology and research design, while section four provides context on the evolution of non-governmental sea rescue. Section five presents the results of our analysis, which are discussed in section six. Section seven and the ensuing conclusions discuss the discursive criminalisation processes we identified and outline the broader implications of our study, sketching some avenues for future research.

2. The discursive criminalisation of migration

Communication frames organise everyday reality by providing ‘meaning to an unfolding strip of events’ (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1987, 143). Scholars have dedicated extensive attention to how media socially construct reality by framing events, phenomena, and actors. The process of media framing entails ‘select[ing] some aspects of a perceived reality and mak[ing] them more salient in a communicating text in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation for the item described’ (Entman Citation1993, 32). Framing occurs through ‘the presence or absence of certain keywords, stock phrases, stereotyped images, sources of information and sentences that provide thematically reinforcing clusters of facts or judgments’ (ibid. 52). Hence, frames manifest themselves in media content through various lexical choices, such as the use of specific adjectives, metaphors, and exemplars. These lexical choices, usually referred to as framing devices, ‘encourage certain kinds of audience processing of texts’ (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1987; Pan and Kosicki Citation1993, 56).

Frames can perform up to four functions, simultaneously defining problems, specifying causes, conveying moral assessment, and advocating solutions (Entman Citation1993). Media framing is therefore especially relevant in shaping public perceptions of complex and contentious phenomena widely seen as ‘crises’, such as large-scale irregular migration. Accordingly, many studies have examined the framing of migration in media, identifying economic, cultural, and security frames (Bleich, Bloemraad, and de Graauw Citation2015; Brouwer, Van der Woude, and Van der Leun Citation2019; Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2017; Heidenreich et al. Citation2019). International relations scholars have focused on the framing of migration as a security issue. Although some studies question the claim that migration has been successfully securitised (Boswell Citation2007; Caviedes Citation2015; Hintjens Citation2019), most agree with Huysmans’ (Citation2000) argument that the discourses and practices surrounding European migration governance have undergone an increasing securitisation process (Bourbeau Citation2011; Chebel d’Appollonia Citation2017; Kaunert and Léonard Citation2020; Squire Citation2015). Securitisation scholars have broken down the framing of migration as a security issue by identifying a variety of securitisation discourses linking migration to specific threats like terrorism, crime, infectious diseases, and the erosion of social cohesion and the welfare state (Bourbeau Citation2011). Whilst securitisation targets different forms of human mobility, it is most pervasive with reference to irregular migration, which is often presented as an unstoppable invasion (Chebel d’Appollonia Citation2017, 263; Kim et al. Citation2011). The ostensibly unregulated inflow of asylum seekers to Europe after the Arab uprisings consequently triggered an upturn in securitisation discourses (Kaunert and Léonard Citation2020).

By presenting mobility as a threat, securitisation often escalates into an outright criminalisation of migration. Much like securitisation, the discursive criminalisation of migration departs from speech acts which construct ‘a criminal threat that is inexorably linked to immigrants as “deviant” characters and immigration as the harbinger of security risks’ (Maneri Citation2011, 77; Squire Citation2015). Scholarship on the criminalisation of migration in Italian media has highlighted the role of framing devices like exemplars, which stereotypically contrast migrants ‘to the quintessential prototype of the respectable citizen’ (Maneri Citation2011, 79) and labels like clandestino, a derogatory term for illegal migrant (Quassoli Citation2013).

As discourse is relational, it operates through both a logic of equivalence and a logic of difference (Laclau and Mouffe Citation1985). By virtue of discussing them together, discourse makes actors and phenomena with no inherent connection appear alike or causally related. Discourses criminalising migration are a case in point: even when not directly framed as threats, migrants are securitised and criminalised through ‘associational links’ with crimes, criminals, and terrorists (Squire Citation2015). Discursive links between migration and criminal activities trigger a ‘chain of connotations’ that ‘automatically allude[s] to a universe of deviant behaviour with which it is connotatively associated’ (Maneri Citation2011, 80).

Logics of equivalence conflating different phenomena often operate through figures of speech like metaphors (Gamson and Modigliani Citation1987; Pan and Kosicki Citation1993). As cognitive shortcuts that simplify complex phenomena but also acquire coded meanings charged with strong emotions, metaphors are pervasive framing devices in the media coverage of migration (Dempsey and McDowell Citation2019; Watson Citation2009) and are often used in discourses criminalising irregular migrants (Arcimaviciene and Baglama Citation2018, 10).

Discourse, however, does not only link together actors and processes through metaphors and associational links, but also sets them apart through a logic of difference. In the case of migration, these othering processes are often grounded in domopolitics, namely the construction of the national political space as ‘a home where we belong naturally and where, by definition, others do not’ (Colombo Citation2018; Darling Citation2014; Walters Citation2002, 241). Accordingly, the criminalisation of migration ‘always operates from the perspective of an “us” which defines “them” as the problem’ (Maneri Citation2011, 77–78). By casting those crossing borders irregularly as intruders entering one’s home without permission, these othering discourses deepen the alleged divide between migrants and well-behaved citizens (Colombo Citation2018; Squire Citation2015).

Last, irregular migrants have often been portrayed as both ‘a risk and at risk’ (Moreno-Lax Citation2018; Aradau Citation2004). As such, the securitisation of migration does not solely consist of framing migrants as threats to national security, but also encompasses humanitarian narratives that present irregular border crossing as a threat to the safety of migrants themselves (Little and Vaughan-Williams Citation2016; Moreno-Lax Citation2018; Watson Citation2009). This appropriation of humanitarian concerns to uphold restrictive migration policies can be identified as a form of frame-jacking, a strategy by which human rights discourses are turned against the emancipatory agendas that they were initially meant to support (Bob Citation2012).

Some scholars have started to examine how maritime rescue is increasingly securitised (Ghezelbash et al. Citation2018) and how the framing of non-governmental sea rescue in Italian public discourse has changed over time, turning organisations previously referred to as ‘angels’ into ‘vice-smugglers’ (Barretta et al. Citation2017; Cusumano and Villa Citation2020). In our analysis, we add to these findings by analyzing the framing devices underlying this discursive process. Specifically, we argue that several of the discursive repertoires already used to criminalise migration have been replicated in the criminalisation of the NGOs rescuing migrants at sea. As sea rescue NGOs allegedly facilitate irregular migration to Europe, associational links, metaphors, othering, and frame-jacking should also underpin the discursive criminalisation of these organisations and those working therein.

3. Research design and methodology

Irregular migration has been criminalised across media outlets worldwide (Brouwer, Van der Woude, and Van der Leun Citation2019; Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2017). This is also the case in new immigration countries like Italy (Maneri Citation2011; Quassoli Citation2013). Due to its location at the centre of the Mediterranean, Italy has recently become both a transit and a destination country for irregular migrants, and had over 500,000 disembarked in its ports between 2013 and 2019 (IOM CitationUndated; Colombo Citation2018). This exposure to irregular maritime mobility has often translated into a criminalisation of humanitarian assistance (Allsopp, Vosyliūtė, and Smialowski Citation2020; Cusumano and Villa Citation2020; Mezzadra Citation2020). As restrictions on acts of solidarity like sea rescue operations have severe implications on human security at sea, Italy is a case of intrinsic importance in studying the criminalisation of humanitarianism.

An analysis of Italian newspapers provides the opportunity to leverage both diachronic and cross-media variations, thereby exploring the role of different factors in enabling or inhibiting the criminalisation of humanitarianism at sea. Between 2014 and 2015, NGOs benefitted from sporadic but largely sympathetic media coverage (Barretta et al. Citation2017). This positive portrayal significantly shifted during 2017, when politicians, prosecutors, and law enforcement agencies forcefully accused NGOs of colluding with human smugglers and serving as a pull factor of irregular migration. By encompassing the period between 2014 and 2019, our timeframe helps assess how these accusations changed pre-existing media frames. Moreover, this timespan covers both a period when irregular migration peaked (2014 to mid-2017) and a phase when departures from Libya dropped to record-low levels (mid-2017–2019). Finally, the timeframe selected spans through the 2018 Italian general elections and three different Italian cabinets, respectively led by the centre-left Democratic Party, the anti-immigration League and Five Stars Movement and the Five Stars Movement and Democratic Party. Hence, this diachronic analysis provides insights into the role of several factors in shaping media coverage of non-governmental SAR, such as the magnitude of irregular migration, the intensity of NGO activities, accusations by law enforcement agencies, prosecutors, and politicians, as well as disembarkation standoffs between humanitarian organisations and the Italian government.

Due to its visibility and humanitarian implications, migration across the Mediterranean is a newsworthy border spectacle (De Genova Citation2013). With over 15,000 casualties between 2013 and 2019, Italy’s southern maritime borders are the deadliest worldwide (IOM CitationUndated). The magnitude and visibility of shipwrecks off the Italian coasts, forcefully denounced by NGOs and opinion leaders like the pope, bolstered calls for humanitarian action, which coexisted and overlapped with narratives securitising and criminalising irregular migration (Barretta et al. Citation2017; Berry, Garcia-Blanco, and Moore Citation2016). Italy’s diverse and polarised media landscape has reflected both types of discourse. We therefore selected one newspaper from each side of the political spectrum – Il Giornale and La Repubblica. Il Giornale is the most prominent right-wing Italian newspaper, with a tabloid style and a political stance close to parties advocating a more restrictive approach to irregular migration, like the League. The progressive outlet La Repubblica, on the other hand, is close to the Democratic Party and widely seen as a quality newspaper. Our newspaper selection therefore serves multiple objectives.

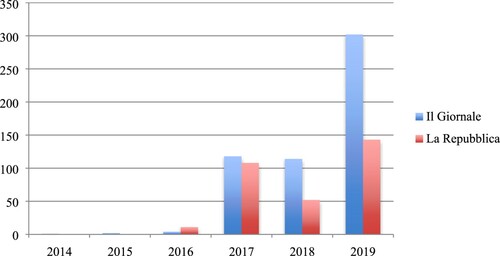

First, as both outlets have widely covered maritime migration and the role of humanitarian actors therein, our case selection consists of a comparable sample of articles, amounting to 755 in the case of Il Giornale and 810 in the case of La Repubblica. As shown in , the total number of words in each sample is also comparable, comprising 417,000 for Il Giornale and 470,000 for La Repubblica. Second, by choosing these two media outlets, we leverage the difference between tabloids and quality press, often seen as an important factor in shaping media framing of migration (Brouwer, Van der Woude, and Van der Leun Citation2019; Caviedes Citation2015; Greussing and Boomgaarden Citation2017). Third, and most importantly, the selection of two newspapers situated at opposite ends of the political spectrum allows us to assess the role of media outlets’ ideological position and their support or hostility to different government majorities.

Table 1. Media coverage of sea rescue NGOs, 2014–2019.

We compiled our sample by including all newspaper articles containing the keywords ONG* (NGO), migrant*, mare (sea), or Mediterraneo, and at least one of either soccors* and salvataggi* (the two Italian terms used for rescue). This strategy allowed us to identify all articles on non-governmental migrant rescue at sea, whilst excluding those pieces that focus on migration at large and other forms of humanitarian relief.

Instead of simply conducting a frame analysis dividing discourses on NGOs into different categories, we have sought to provide a more fine-grained examination of Italian media discourses by focusing on the framing devices that enable the criminalisation of non-governmental sea rescue. To that end, we have used a combination of qualitative discourse analysis and quantitative content analysis. Quantitative, computer-assisted content analysis complements and extends discourse analysis by helping identify discursive patterns in vast amounts of texts, systematically quantify the relative weightings of these patterns in different bodies of text, and track their diachronic evolution (Bennett Citation2015; Feltham-King and Macleod Citation2016, 2). While our approach is interpretive, we therefore used the content analysis software Atlas.ti to map the in-context iterations of all relevant nouns, verbs, and adjectives relating to the criminalisation of sea rescue NGOs. This strategy helped us identify the main framing devices underlying their criminalisation and map their variance between newspapers and over time.

We consider as associational links all those instances in which terms used to describe crimes and criminals, such as ‘illegal immigration’ and ‘human smugglers’, co-occur with the words used to identify sea rescue NGOs. Relatedly, we look at all metaphors used to describe NGOs and their activities in derogatory terms, as well as all the adjectives and expressions othering humanitarian actors from readers by, for instance, indicating their foreign nationality or their allegedly radical political background. As the framing of sea rescue operations cannot be isolated from the broader coverage of irregular migration, we also look at the extent to which migration across the Mediterranean is framed as a threat or a humanitarian issue. We use variations in the use of each of these framing devices over time and between newspapers as a quantitative indicator of the relative salience and content of specific criminalisation discourses.

The discourse analysis was complemented with 30 background interviews with humanitarians and law enforcement personnel, participant observation of four meetings between NGOs and Italian authorities, as well as a two-week non-governmental rescue mission off the coast of Libya in August 2016. Interviews and participant observation serve as a source of information on NGOs’ activities, which criminalisation discourses stakeholders perceive to be most salient, and the impact of criminalisation on non-governmental SAR.

4. The rise and fall of non-governmental maritime rescue

In October 2014, the Italian Navy maritime rescue mission Mare Nostrum was replaced by the EU-funded European Border and Coast Guard (still known as Frontex) operation Triton, which had a much narrower mandate and operational area. In May 2015, the European Council also launched the military operation EUNAVFOR Med, focused on disrupting human smuggling (Baldwin-Edwards and Lutterbeck Citation2019; Perkowsky and Squire Citation2019; Steinhilper and Gruijters Citation2018).

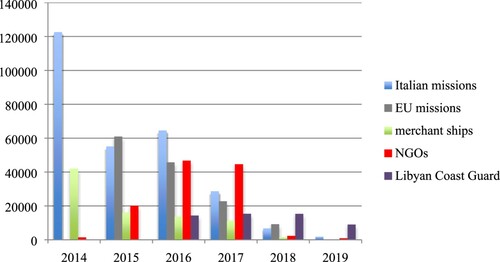

In response to the shortage of state-led rescue missions, several NGOs launched their own SAR operations. These began in September 2014 with the creation of the Migrant Offshore Aid Station (MOAS). The Amsterdam, Barcelona, and Brussels branches of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the German charities Sea-Watch, Sea-Eye, Lifeboat, and Jugend Rettet, the Spanish organisation Proactiva Open Arms, and Save the Children also launched SAR missions in the Central Mediterranean between 2015 and 2017. Mission Lifeline, Mediterranea Saving Humans and Aita Mari joined in 2017, 2018, and 2019 respectively. In 2016 and 2017, as illustrated by below, these organisations became a crucial provider of maritime rescue in the Central Mediterranean (Cusumano Citation2021; Cuttitta Citation2018; Stierl Citation2018).

Accusations that SAR incentivizes irregular migration were already levelled against Mare Nostrum, which was criticised as ‘an unintended pull factor, encouraging more migrants to attempt the dangerous sea crossing and thereby leading to more tragic and unnecessary deaths’ (House of Lords Citation2016).

When NGOs launched their operations in 2014, however, they were initially warmly praised by Italian authorities. While broadly positive, Italian media coverage of non-governmental rescue remained limited, and NGOs’ activities were rarely distinguished from Italian and European authorities’ rescue operations (Barretta et al. Citation2017). Eventually, however, non-governmental sea rescuers were confronted with the same accusations raised against Mare Nostrum. This criticism was initially formulated outside Italy. In December 2016, the Financial Times leaked an excerpt from a Frontex report claiming that migrants had received ‘clear indications … to reach the NGOs’ boats’ (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020, 7). Although the newspaper later released a correction, these concerns were indirectly reiterated by reports published in 2017 and 2020, which mention ‘NGO vessels in the proximity of Libyan territorial waters and their access to European ports’ as ‘key determiners’ of irregular migratory flows (Citation2020, 21, Citation2017).

In early 2017, this criticism spilled over into the Italian policy debate, where it escalated into accusations of direct collusion with human smugglers. In April 2017, Catania’s Attorney General Carmelo Zuccaro claimed that he had evidence of direct contacts between smugglers and NGOs. Although Zuccaro later downplayed his own statements as ‘working hypotheses’, his accusations were echoed by opposition parties. Most notably, Five Stars Movement’s Luigi Di Maio, then deputy president of the Italian Chamber of Deputies, popularised the metaphor of NGOs as ‘sea taxis’. In response, the Italian parliament initiated an enquiry and the center-left cabinet led by Paolo Gentiloni issued a code of conduct on maritime rescue which imposed various restrictions on NGOs’ activities, threatening non-signatories with having the authorisation to disembark migrants in Italian ports denied (Allsopp, Vosyliūtė, and Smialowski Citation2020; Cusumano and Villa Citation2020).

Shortly after his appointment as interior minister in June 2018, League Secretary Matteo Salvini declared Italian ports ‘closed’ to rescue ships, consistently vetoing or delaying the disembarkation of migrants on Italian territory to showcase his tough stance on irregular migration. During the Conte I cabinet (June 2018 – August 2019), Italy engaged in several standoffs with NGO ships and enacted specific legal provisions criminalising maritime rescue (Berti Citation2020; McDowell Citation2020). Besides being the target of policy restrictions, NGOs were increasingly subjected to judicial proceedings. Although accusations of aiding and abetting illegal immigration were very rarely supported by sufficient evidence to start a trial, rescue ships were frequently impounded and grounded for several months (Allsopp, Vosyliūtė, and Smialowski Citation2020; Cusumano and Villa Citation2020).

As acknowledged by all the humanitarian personnel interviewed, the combined effect of policy restrictions and growing risk of indictment+ severely impaired NGOs’ ability to conduct SAR operations. These developments, together with the sharp decrease in irregular departures from Libya since July 2017, caused non-governmental SAR to plummet. In 2019, only 925 migrants were assisted by NGO ships (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020, 6).

5. Results: sea rescue NGOs in Italian newspapers

Although Il Giornale and La Repubblica have portrayed migration across the Mediterranean in fundamentally different ways, their coverage of non-governmental sea rescue follows a similar pattern. In 2014–2016, when NGO operations were largely viewed as complementing Italian Navy and Coast Guard efforts, they triggered little in-depth discussion and were generally depicted in a positive light. Each newspaper’s attention to non-governmental SAR increased enormously only in 2017, when the coverage of NGOs’ activity spilled over into political and judicial reporting sections. This section examines each paper’s portrayal of non-governmental rescue operations and the salience of criminalisation discourses therein.

5.1. Il Giornale: direct and indirect criminalisation

The discourses used by Il Giornale to criminalise migration rapidly permeated their coverage of maritime rescue operations as well. Already in 2014, the conservative newspaper harshly criticised Italian Navy mission Mare Nostrum. This criticism became more heated and pervasive as NGOs replaced Italian security forces as the largest providers of SAR. Until late 2016, however, non-governmental rescue activities were largely ignored and only sporadically mentioned in neutral terms.

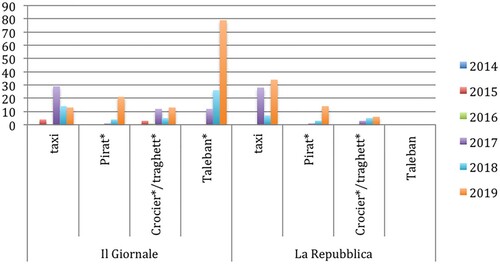

Since the first accusations against NGOs were made, however, humanitarians have been criminalised through both direct and indirect discourses. NGOs’ purported collaboration with human smugglers is the most salient direct criminalisation discourse. This is epitomised by the frequency of keywords like ‘collusion’ (36 iterations), ‘accomplice’, and ‘complicity’ (54 iterations), as well as ‘contacts’ between NGOs and smugglers (33 iterations). These associational links often take a more indirect form, relying on metaphors and circumlocutions that imply a causal connection between non-governmental sea rescue and irregular immigration, as illustrated by the widespread reference to NGOs as a ‘taxi’ service (61 iterations). This expression is complemented with similar metaphors comparing SAR assets to ‘ferries’ (24 iterations) and ‘cruise ships’ (4 iterations). By creating strong associational links between humanitarians and smugglers, these framing devices trigger a chain of connotations that shifts the stigma attached to smugglers onto aid workers.

The second discourse used by Il Giornale to directly criminalise NGOs focuses on their alleged disrespect for Italian borders and authorities. Consequently, humanitarians are accused of illegally trespassing into Libyan and Italian waters and concealing their movements. This discourse frames NGOs as rule-breakers by frequently using nouns like sconfinamento, Italian for the unlawful trespassing of borders and the verbs ‘ignore’ (23 iterations), ‘not respect’ (32 iterations), or ‘not give a damn’ (expressed by the two verbs fregarsene or infischiarsene – 22 iterations). Consequently, NGOs have frequently been labelled as fuorilegge, or ‘outlaws’ (24 iterations). Such labels gained enormous traction after the accidental collision between the Sea-Watch 3 and an Italian Customs Police speedboat that occurred in the port of Lampedusa on 2 July 2019. This episode, described by Il Giornale as a deliberate ‘ramming’, resulted in the arrest of shipmaster Carola Rackete on charges of ‘violence against a warship’. The framing of NGOs as in violation of international and Italian law is buttressed by another widely-used metaphor that likens humanitarian actors to another category of maritime criminals that carries strong stigma, that of ‘pirates’ (30 iterations).

Discourses questioning NGOs’ sources of funding also play a prominent role in criminalisation, fuelling distrust of humanitarians’ motives. After Catania’s prosecutor Zuccaro claimed that non-governmental sea rescue was too expensive to be sustained through lawful donations alone, the terms ‘funded’ or ‘financed’ with reference to NGOs’ operations were iterated 73 times, often complemented by adjectives like ‘suspicious’ and ‘unclear’. In several cases, Il Giornale explicitly hinted at conspiracy theories propagated by the extreme right, such as that investor and philanthropist George Soros – whose name is iterated 36 times – funded NGOs to ferry cheaper migrant workforce from Africa and even carry out an ethnic replacement of European native populations. More broadly, NGOs were framed as profiteers that benefit from the economic opportunities arising from the exploitation of irregular migrants. In Il Giornale’s articles, sea rescue NGOs are often lumped together with the charities running Italian asylum seekers’ reception centres. Cases of fraud and mismanagement in these facilities are therefore also used to suggest guilt by association, implying that sea rescue NGOs enable and directly participate in this lucrative migrant reception industry. Accordingly, Il Giornale’s coverage of non-governmental SAR operations is fraught with the word ‘business’, iterated 80 times.

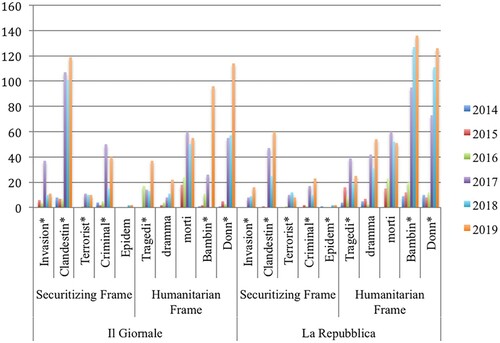

Moreover, NGOs are indirectly criminalised as enablers of illegal immigration. In its coverage of maritime migration, Il Giornale systematically refers to asylum seekers as ‘clandestini’ (152 iterations) and ‘illegal’ (118 iterations), describing irregular migration as an ‘invasion’ (70 iterations). Coverage of sea rescue operations frequently mentions terrorism (270 iterations), as well as infectious diseases like scabies (61 iterations), tuberculosis (33 iterations) and Ebola (33 iterations). The reproduction of discourses securitising migration in articles dedicated to non-governmental sea rescue indirectly implicates humanitarian actors in the perpetration of crimes, framing their activities as a threat to national security.

Discourses criminalising irregular migration and its alleged facilitators often coexist with victimisation narratives giving extensive coverage to migrants’ deaths at sea. The blame for their suffering, however, is systematically shifted onto the permissive asylum policies and the SAR operations allegedly luring migrants to sea. The coverage of the large shipwreck that occurred in April 2015 is a case in point. In the very title of the piece reporting the shipwreck, Il Giornale states that ‘700 died from buonismo’, a derogatory Italian expression stigmatising the do-goodism and naïveté of overly permissive border enforcement (Sallusti Citation2015). This argument is founded on the accusation that NGOs were serving as a pull factor of irregular migration. While the original English term ‘pull factor’ is only mentioned 3 times, Il Giornale frequently used different Italian expressions with similar meanings, including ‘incentivizing’ (26 iterations), and ‘attracting’ illegal immigration (15 iterations).

Finally, NGOs are indirectly criminalised through two different othering discourses. First, humanitarians are systematically framed as extreme left-wing activists. Humanitarians are therefore labelled as ‘rebels’ (16 iterations) and ‘extremists’ (13 iterations). This allegedly radical ideology is buttressed by labelling humanitarians and open borders advocates as ‘Taliban’ (106 iterations), a metaphor used to stress their allegedly uncompromising approach to migration, as well as ‘irresponsible’ and ‘reckless’ (21 iterations). Second, emphasis is placed on the foreign nationality of humanitarians and their ships. Accordingly, the word ‘foreign’ is iterated 19 times, while charities and their personnel are consistently presented as ‘German’ (146 iterations), ‘Spanish’ (86 iterations), or ‘French’ (33 iterations). This emphasis on NGOs’ foreign nationality not only frames humanitarian actors as alien to the Italian population, but is also instrumental to a last, more direct accusation: that rescue ships illegally enter Italian waters and ports. Regardless of the enormous additional distance, humanitarians are accused of refusing to take those rescued to the northern European countries where their organisations or ships are registered, deliberately offloading migrants’ burden onto Italy’s shoulders.

5.2. La Repubblica: a chiaroscuro portrait

While criticism of NGOs was especially pervasive in Il Giornale and other right-wing outlets, some of the framing devices enabling the criminalisation of non-governmental sea rescue occasionally spilled over into progressive newspapers as well. Certainly, La Repubblica refrained from engaging in the most direct criminalisation strategies mentioned above. Accordingly, derogatory adjectives like ‘pirates’, ‘taxis’, or ‘cruise ships’ exclusively appear in inverted commas when reporting or criticising anti-immigration politicians’ declarations. Likewise, the argument that NGOs are driven by ‘business’ (50 iterations), rather than humanitarian motives is almost always reported as direct quotes and consistently dismissed. The ample visibility given to these statements by a widely-read, progressive mainstream paper, however, may have inadvertently increased the salience of these accusations. The metaphor of NGOs as taxis, for instance, can be found 67 times, even more frequently than in Il Giornale.

La Repubblica was broadly supportive of NGOs from 2014 until early 2017, a period in which one of their reporters was frequently hosted on SOS-Méditerranée’s ship, and from 2018 onwards, vocally criticising Salvini’s ‘closed ports’ policy. In the second half of 2017, however, when some organisations refused to sign the code of conduct sponsored by the Democratic Party Interior Minister Minniti and the German NGO Jugend Rettet was indicted, the progressive paper uncritically subscribed to some criminalisation discourses. In the articles covering the investigations, accusations against humanitarian actors are no longer introduced as quotations, but presented as statements of fact. In a column from 3 August, leading reporter Carlo Bonini states that this ‘courageous investigation … incontrovertibly illustrates’ that Jugend Rettet ‘did not rescue migrants … it shuttled them to Italy in cahoots with human smugglers’. The position of Jugend Rettet and the other NGOs that did not sign the code of conduct is even defined as an ‘ideological obscenity that actually stands against any humanitarian principle’. Although this column and several other articles distinguish between ‘good and bad’ NGOs, La Repubblica’s coverage of this case inevitably triggers guilt by association mechanisms, drawing a connection between human smugglers, Jugend Rettet, and all likeminded NGOs that opposed the code of conduct. Accordingly, the investigation of Jugend Rettet is framed as an opportunity to ‘bring clarity into the world of humanitarian organizations’ at large (Bonini Citation2017).

The progressive newspaper, however, largely refrains from criminalising NGOs by drawing an associational link between their activities, the crime of illegal immigration, and the threats allegedly posed by migrants. Indeed, La Repubblica uses words like clandestini (44 iterations), ‘illegal’ (68 iterations), and ‘invasion’ (34 iterations) much less frequently than Il Giornale, and almost always in quotations from right-wing politicians’ speeches. Discourses establishing a migration-crime and a migration-terrorist nexus are also less frequent but not entirely absent, as shown by the iteration of terms like ‘terrorists’ (56 iterations) and ‘criminals’ (97 iterations). Likewise, La Repubblica does not entirely refrain from framing migrants as carriers of infectious diseases, including Ebola (49 iterations) and scabies (47 iterations).

Whilst mainly serving the purpose of attracting sympathy towards the plight of those rescued at sea, framing devices victimising migrants may inadvertently contribute to framing maritime rescue as problematic. La Repubblica’s discourses also indirectly contributed to securitising irregular maritime migration by framing it as a ‘crisis’ (140 iterations) or an ‘emergency’ (286 iterations), making extensive use of a vulnerability lexicon, including words like ‘women’ (379 iterations), many of whom ‘pregnant’ (70 iterations), ‘children’ (340 iterations), and ‘toddlers’ (84 iterations), as well as violence (119 iterations), ‘torture’ (59 iterations), and ‘rape’ (13 iterations) suffered by migrants. These victimisation discourses certainly help portray migration in a more humane way, but also contribute to securitising mobility by framing irregular crossings as a human security threat. Although La Repubblica consistently appreciates the humanitarian motive behind SAR operations, their emphasis on the tragedies taking place on irregular migratory routes indirectly supports the concern that rescue operations could have unintended consequences by serving as a pull factor. Accordingly, the English word ‘pull factor’ is mentioned 8 times, while Italian expressions with similar meanings are iterated on 16 occasions. This argument is frequently questioned, but sometimes cited uncritically as well.

Last, La Repubblica refrains from othering humanitarian actors (with the partial exception of Jugend Rettet) as extremists, but systematically attaches national labels like ‘German’ (106 iterations) and ‘Spanish’ (43 iterations). Unlike Il Giornale, the progressive paper does not subscribe to the argument that foreign-flagged ships should be banned from Italian waters. Indeed, after the 2018 elections and the introduction of Salvini’s ‘closed ports’ policy, La Repubblica vehemently criticised policy restrictions on NGOs’ activities. Their emphasis on the foreign nationality of most NGOs, however, is sometimes contrasted with EU countries’ lack of solidarity in the resettlement of asylum seekers, indirectly increasing Italians’ frustration towards non-governmental sea rescuers.

6. The framing of NGOs in Italian media: findings and discussion

As a basic social norm that has become increasingly contested after irregular maritime migration increased, the duty to rescue at sea can be simultaneously framed in different ways. Communication scholars have often noted that newspapers tend to prioritise crime and crisis-centered news items, displaying a tendency to frame stories in general – and migration-related stories more specifically – as problems rather than opportunities (Bleich, Bloemraad, and de Graauw Citation2015). Consistent with these findings, our analysis shows that the salience of non-governmental rescue operations in the two Italian newspapers we examined increased in parallel with criminalisation discourses. Accordingly, accusations made by Frontex, politicians, and prosecutors played a key role in both increasing the salience of non-governmental sea rescue and changing its previously positive framing.

As illustrated by comparing and , both newspapers’ coverage of NGOs’ SAR operations increased enormously only after the first accusations by Frontex were echoed and built upon by Italian politicians and prosecutors. This shift caused a paradoxical decoupling between the shrinking frequency of NGOs’ rescue operations at sea and their growing salience in Italian newspapers. Both the number of articles covering sea rescue NGOs and the total number of words therein skyrocketed precisely when their involvement in SAR operations began to decrease. Paradoxically, NGOs’ salience peaked in 2019, when their ships rescued fewer than 1000 migrants. The confiscation of humanitarian vessels and the standoffs caused by Italy’s refusal to authorise disembarkation reduced NGOs’ ability to rescue migrants, but also enormously increased the visibility of those operations, which had previously obtained much more limited media coverage. As a result of this sudden increase in the salience of non-governmental sea rescue, a large part of the Italian public only learnt about NGOs’ activities after they had become controversial.

Once the coverage of NGO rescue operations had increased disproportionately, both direct and indirect criminalisation discourses emerged. Within these discourses, four framing devices previously used to criminalise migration at large played a crucial role in triggering suspicion towards non-governmental SAR: associational links, frame-jacking, metaphors, and othering. First, NGOs were indirectly criminalised by drawing associational links between rescue operations and activities that are themselves unlawful. In some cases, most frequently in Il Giornale, NGOs are directly criminalised as acting in collusion with human smugglers or behaving like pirates. In most others, as illustrated by , this connection is drawn more indirectly by reporting the concern that NGOs’ operations facilitate human smuggling or mentioning both rescue operations and human smugglers within the same article.

Relatedly, non-governmental sea rescue is often discussed within a broader discursive frame which criminalises irregular migration. Unsurprisingly, as illustrated by , glaring differences can be found between the right-wing and the progressive outlet’s framing. Il Giornale directly criminalises those rescued at sea by systematically referring to them as illegal migrants and securitising them as potential terrorists, criminals, and carriers of infectious diseases. La Repubblica, by contrast, is much more sympathetic with migrants’ plight. Their strong emphasis on asylum seekers’ vulnerability, however, arguably had ambivalent effects, both humanising those rescued and magnifying the human costs of irregular migration, thereby securitising seaborne mobility and fuelling the concern that SAR operations have unintended consequences by acting as a pull factor. This accusation is explicitly formulated by Il Giornale, which consistently holds proactive rescue operations disembarking migrants in Europe responsible for deaths at sea and uses humanitarian arguments to advocate for more restrictive border enforcement. The appropriation of humanitarian discourses to support restrictive border enforcement policies and criminalise rescuers can clearly be identified as a form of discursive frame-jacking.

Metaphors have also served as a key indirect criminalisation tool. shows that newspapers have propagated metaphors coined by Italian politicians, who associated NGOs with ‘taxis’, ‘cruise ships’, and ‘pirates’. Right-wing newspapers like Il Giornale have made ample use of these statements, adding similar analogies referring to NGO ships as ‘ferries’ and open border advocates as ‘Taliban’. Left-wing outlets like La Repubblica only used derogatory metaphors when reporting politicians’ statements or in columns criticising these accusations. By doing so, however, La Repubblica inadvertently contributed to the salience of these expressions too, which enjoyed widespread currency in the period between mid-2017 and 2019. As documented by migration and security scholars alike, academic and media attempts to desecuritize migration may have unintended consequences by increasing the visibility of the very discourses they seek to debunk (Swarts and Karakatsanis Citation2013).

Metaphors, in combination with the broader framing of NGO rescue operations, contribute to the othering of humanitarians. Even if not directly criminalised, humanitarian actors are presented by Il Giornale as left-wing extremists and by both newspapers as foreigners. The implications of this othering process, illustrated by , are especially apparent when examined through the conceptual lens of domopolitics. The frequent references made to NGOs’ foreign nationality frames humanitarians as alien to Italian society, uncaring of its needs, and having no right to decide who is to enter and live in Italy. Furthermore, othering labels revolving around the nationality of NGOs tapped into Italians’ frustration about the uneven burden sharing of asylum seekers across the EU, as well as broader political and economic grievances against countries like Germany, France, and the Netherlands, where most NGOs are headquartered or registered their ships.

In sum, while the salience of non-governmental sea rescue in both Il Giornale and La Repubblica increased after the first accusations against NGOs were made, the extent to and the ways in which NGOs have been criminalised has been mediated by newspapers’ ideological orientation and political partisanship. Unsurprisingly, discursive constructions criminalising NGOs are systematic in a conservative outlet like Il Giornale, but more sporadic in a progressive one like La Repubblica. However, even La Repubblica indirectly contributed to delegitimizing NGOs, and in some rare cases even formulated direct criminalisation discourses against the organisations opposing the code of conduct in 2017. La Repubblica’s coverage of sea rescue NGOs, however, reverted to its previously very positive tone after the 2018 elections, leveraging sea rescue restrictions to criticise the newly-formed government coalition between the Five Stars Movement and the League.

These findings suggest that the sea rescue – and non-governmental rescue operations specifically – has become increasingly politicised. The framing of migration increasingly reflects new political cleavages predicated upon support or opposition to European integration, economic globalisation, and migration alike, such as those between Green, Alternative, and Liberal (GAL) and Traditional, Authoritarian, and Nationalist (TAN) parties (Hooghe and Marks Citation2017). Studies of migration to Italy show that maritime irregular arrivals to Italy were increasingly politicised after 2014 (Dennison and Geddes Citation2021; Urso Citation2018). Once sea rescue operations became contentious, the activities of the NGOs conducting them became increasingly politicised as well. Accordingly, newspapers situated at the TAN side of the political spectrum display a much higher propensity to engage in the criminalisation of sea rescue NGOs compared to their GAL counterparts. The fact that most NGOs were headquartered in northern European countries, yet the EU failed to implement any meaningful asylum redistribution scheme allowed outlets like Il Giornale to subsume Euroscepticism and hostility to migration under the rubric of domopolitics. Humanitarian actors were therefore framed as foreign extremists or outright criminals violating Italian borders and exacerbating other EU member states’ lack of solidarity towards Italy.

7. Implications, future research, and conclusions

Media frames help define issues as problems, conveys moral assessments, establish causes, and advocate solutions (Entman Citation1993). By linking NGOs to human smuggling, comparing their activities to taxies or ferries, and labelling them as foreign actors, Italian newspapers contributed to NGOs’ discursive criminalisation. In Il Giornale especially, coverage of NGOs operating at sea is subsumed within a broader frame that sees irregular migration as a crime, sea rescue operations as a pull factor, and restrictive border enforcement as the solution. Our findings contribute to both the academic scholarship and the policy debate on humanitarianism, border security, and migration at large.

First, our findings add to the scholarship on the policing of humanitarianism and the governance of indifference. As noted by Basaran (Citation2015, 207), the governing of indifference in liberal society requires ‘subtle forms of governing, not based upon coercion and force but embedded in routine and less visible practices’. Scholarship on the criminalisation of migration has highlighted the key role of discourse in governing human mobility, showing that media and political discourses enable and precede policy and judicial restrictions on migrants (Maneri Citation2011; Parkin Citation2013; Vollmer Citation2011). We have shown that many of the discursive devices used to criminalise irregular migration have been replicated in the framing of sea rescue NGOs. Most notably, we have highlighted the key role of associational links, metaphors, frame-jacking, and othering processes in informing a discursive criminalisation of non-governmental sea rescue. This framing process contributes to the governance of indifference. Framing devices presenting humanitarian actors as criminals, extremists, or merely foreigners reinforce the impression that solidarity towards those in distress at sea is not a basic social norm, but an abnormal, suspicious and fundamentally problematic activity, indirectly legitimising indifference to deaths at sea. Future research should examine whether these framing devices can be found within a broader population of newspapers and across other media, both in Italy and in other countries.

Second, our study shows that the salience of non-governmental sea rescue in Italian media and the role played by these organisations in rescuing migrants were completely decoupled. The newspapers’ coverage of non-governmental rescue operations and the accusation that NGOs’ activities acted as a pull factor of migration peaked when the number of migrants they rescued at sea plummeted. This distortion in the portrayal of NGOs vindicates the claim that news outlets’ framing of irregular migration to Europe is often disjointed from any actual or objective reality (Triandafyllidou Citation2017).

Our findings also support previous studies in noting that the role played by media in this criminalisation process is reactive rather than proactive (Brouwer, Van der Woude, and Van der Leun Citation2019). Rather than initiating criminalisation discourses, Italian right-wing outlets like Il Giornale only started to systematically cover sea rescue NGOs after the first accusations against them were made. Even progressive outlets like La Repubblica, which had previously dedicated some attention to non-governmental SAR, vastly increased their coverage of NGOs’ activities once they came under scrutiny. Although media did not initiate the discursive criminalisation process, they nevertheless played a key role in amplifying the claims made by Frontex, prosecutors, and politicians. Relatedly, scholarship on Frontex has mainly stressed the role of the organisation in securitising migration through border practices (Kaunert and Léonard Citation2020). The decisive role played by Frontex’s accusations in changing how sea rescue NGOs were franed and initiating their discursive criminalisation is a forceful reminder of the EU border agency discursive power and the importance of its speech acts.

Third, our analysis confirms that media framing of NGOs – like migration at large – is increasingly politicised and polarised along ideological and partisan lines (Brouwer, Van der Woude, and Van der Leun Citation2019; Helbling Citation2013). Accordingly, right-wing, anti-immigration outlets like Il Giornale have consistently criminalised NGOs. By contrast, La Repubblica has developed a much more sympathetic approach towards non-governmental sea rescuers. These findings suggest that the framing of sea rescue NGOs is increasingly shaped by newspapers’ political positioning along new political cleavages such as the GAL/TAN divide. In order to more comprehensively appraise the role of newspapers’ ideological position in framing their coverage of maritime migration and rescue operations, an examination of a broader array of media outlets and countries is warranted.

Given that policy restrictions had a severe impact on the ability to rescue lives at sea, the discursive portrayal of sea rescue NGOs has important policy and normative implications. While existing literature has focused on the use of legal instruments to police humanitarianism, discourse also plays a powerful role in deterring solidarity. According to the interviews conducted for this study, most NGOs experienced difficulties in donations and recruiting after accusations of collusion with smugglers were publicised by media. Suspicion against NGOs often escalated into hate speech against organisations and individual volunteers, who denounced a growing climate of intimidation. As more broadly illustrated by survey data, negative media framing of NGOs was followed by plummeting public support towards non-governmental sea rescuers in Italy (Diamanti Citation2017). By delegitimizing the activities of NGOs, these discourses severely impacted human security at sea. Between 2018 and 2019, when policy restrictions on non-governmental rescue ships were tighter, the deadliness of irregular migration across the Central Mediterranean peaked at over 6 per cent (Cusumano and Villa Citation2020).

The combination of the growing migration crisis fatigue of the Italian public, lack of EU-wide solidarity, and the accusations made by Frontex, prosecutors, and politicians provided an ideal backdrop for the discursive criminalisation of non-governmental sea rescue. For this reason, it was very difficult for NGOs to defend themselves against accusations and spread alternative counternarratives. The discourses we examined, however, suggest that sea rescue NGOs seeking to enhance their legitimacy should act on two fronts. First, criminalisation discourses leveraged internal divisions in the non-governmental sea rescue community, initially framing the organisations that decided not to sign the 2017 code of conduct as suspicious and then implicating the others through a process of guilt by association. This finding suggests that the non-governmental sea rescue community is only as strong as its weakest link, forcefully showing the need for NGOs to coordinate in order to form a unified front against criminalisation. Second, the prominence of framing devices othering humanitarian workers by leveraging their foreign nationality suggests the need for all sea rescue organisations to develop stronger links with Italian civil society. Given the pervasiveness of domopolitics in Italian newspapers’ discourses on irregular migration, having Italian crewmembers and spokespersons would help challenge the framing of sea rescue NGOs as foreign actors with no right to decide who is to cross Italian borders.

As media framing of sea rescue NGOs has important policy implications, our study also contributes to the broader debate on the implications of media coverage of migration, resonating with previous research problematising the discourses portraying irregular mobility across the Mediterranean as a humanitarian crisis. These narratives not only indirectly legitimize policies seeking to deter irregular migration (Little and Vaughan-Williams Citation2016; Triandafyllidou Citation2017), but may also portray rescue NGOs as enablers of irregular mobility, shifting attention away from the root causes of migration.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (2.3 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allsopp, Jennifer, Lina Vosyliūtė, and Stephanie Smialowski. 2020. “Picking ‘Low-Hanging Fruit’ While the Orchard Burns: The Costs of Policing Humanitarian Actors in Italy and Greece as a Strategy to Prevent Migrant Smuggling.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-020-09465-0.

- Aradau, Claudia. 2004. “The Perverse Politics of Four-Letter Words: Risk and Pity in the Securitisation of Human Trafficking.” Millennium – Journal of International Studies 33 (2): 251–277. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/03058298040330020101.

- Arcimaviciene, Liudmila, and Sercan Hamza Baglama. 2018. “Migration, Metaphor and Myth in Media Representations: The Ideological Dichotomy of ‘Them’ and ‘Us’.” Sage Open 8 (2): 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018768657.

- Baldwin-Edwards, Martin, and David Lutterbeck. 2019. “Coping with the Libyan Migration Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (12): 2241–2257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1468391.

- Barretta, Paola, Giuseppe Milazzo, Daniele Pascali, Valeria Brigida, and Martina Chichi. 2017. “Navigare a Vista. Il Racconto delle Operazioni di Ricerca e Soccorso nel Mediterraneo.” Osservatorio di Pavia. https://www.osservatorio.it/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Report_SAR_NDA.pdf.

- Basaran, Tugba. 2015. “The Saved and the Drowned: Governing Indifference in the Name of Security.” Security Dialogue 46 (3): 205–220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010614557512.

- Bennett, Andrew. 2015. “Found in Translation: Combining Discourse Analysis with Computer Assisted Content Analysis.” Millennium 43 (3): 984–997. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829815581535.

- Berry, Mike, Inaki Garcia-Blanco, and Kerry Moore. 2016. “Press Coverage of the Refugee and Migrant Crisis in the EU: A Content Analysis of Five European Countries.” Project Report, Geneva: United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. http://www.unhcr.org/56bb369c9.html.

- Berti, Carlo. 2020. “Right-Wing Populism and the Criminalization of sea-Rescue NGOs: The ‘Sea-Watch 3’ Case in Italy.” Media, Culture, and Society. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443720957564.

- Bleich, Erik, Irene Bloemraad, and Els de Graauw. 2015. “Migrants, Minorities and the Media: Information, Representations and Participation in the Public Sphere.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (6): 857–873. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.1002197.

- Bob, Clifford. 2012. The Global Right Wing and the Clash of World Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bonini, Carlo. 2017. “Buoni e Cattivi di una Catastrofe Umanitaria.” La Repubblica, August 3. https://ricerca.repubblica.it/repubblica/archivio/repubblica/2017/08/03/buoni-e-cattivi-di-una-catastrofe-umanitaria01.html.

- Boswell, Christina. 2007. “Theorizing Migration Policy: Is There a Third Way?” International Migration Review 41 (1): 75–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00057.x.

- Bourbeau, Philippe. 2011. The Securitization of Migration. London: Routledge.

- Brouwer, Jelmer, Maartje Van der Woude, and Joanne Van der Leun. 2019. “Framing Migration and the Process of Crimmigration: A Systematic Analysis of the Media Representation of Unauthorized Immigrants in the Netherlands.” European Journal of Criminology 14 (1): 100–119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370816640136.

- Carrera, Sergio, Lina Vosyliute, Jennifer Allsopp, and Valsamis Mitsilegas. 2019. Policing Humanitarianism: EU Policies Against Human Smuggling and their Impact on Civil Society. Oxford: Hart.

- Caviedes, Alexander. 2015. “An Emerging ‘European’ News Portrayal of Immigration?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (6): 897–917. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2014.1002199.

- Chebel d’Appollonia, Ariane. 2017. “Xenophobia, Racism and the Securitization of Immigration.” In Handbook on Migration and Security, edited by Philippe Bourbeau, 252–272. New York: Routledge.

- Colombo, Monica. 2018. “The Representation of the ‘European Refugee Crisis’ in Italy: Domopolitics, Securitization, and Humanitarian Communication in Political and Media Discourses.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2): 161–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1317896.

- Cusumano, Eugenio. 2021. “United to Rescue? Humanitarian Role Conceptions and NGO–NGO Interactions in the Mediterranean Sea.” European Security. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2021.1893698.

- Cusumano, Eugenio, and Matteo Villa. 2020. “From ‘Angels’ to ‘Vice Smugglers’: The Criminalization of Sea Rescue NGOs in Italy.” European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 27 (3): 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-020-09464-1.

- Cuttitta, Paolo. 2018. “Repoliticization Through Search and Rescue? Humanitarian NGOs and Migration Management in the Central Mediterranean.” Geopolitics 23 (3): 632–660. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1344834.

- Darling, Jonathan. 2014. “Asylum and the Post-Political: Domopolitics, Depoliticisation and Acts of Citizenship.” Antipode 46: 72–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12026.

- De Genova, Nicholas. 2013. “Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7): 1180–1198. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.783710.

- Dempsey, Kara, and Sara McDowell. 2019. “Disaster Depictions and Geopolitical Representations in Europe’s Migration ‘Crisis’.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 98: 153–160. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.11.008.

- Dennison, James, and Andrew Geddes. 2021. “The Centre no Longer Holds: The Lega, Matteo Salvini and the Remaking of Italian Immigration Politics.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1853907.

- Diamanti, Ilvo. 2017. “ONG: I muri alzati delle parole.” Repubblica, August 6. https://www.repubblica.it/politica/2017/08/06/news/speranza_e_bene_comune_ecco_come_salvare_le_ong_dall_ideologia_della_destra-172479341/.

- Entman, Robert. 1993. “Framing: Towards Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- Fekete, Liz. 2018. “Migrants, Borders and the Criminalisation of Solidarity in the EU.” Race and Class 59 (4): 65–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396818756793.

- Feltham-King, Tracey, and Catriona Macleod. 2016. “How Content Analysis may Complement and Extend the Insights of Discourse Analysis: An Example of Research on Constructions of Abortion in South African Newspapers 1978–2005.” International Journal of Qualitative Methods 15 (1): 1–9.

- Frontex. 2017. “Risk Analysis for 2017.” Frontex. https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Annual_Risk_Analysis_2017.pdf.

- Frontex. 2020. “Risk Analysis for 2020.” Frontex. https://frontex.europa.eu/assets/Publications/Risk_Analysis/Risk_Analysis/Annual_Risk_Analysis_2020.pdf.

- Gamson, William, and Andre Modigliani. 1987. “The Changing Culture of Affirmative Action.” In Research in Political Sociology, edited by R. G. Braungart, and M. M. Braungart, 137–177. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

- Ghezelbash, Daniel, Violeta Moreno-Lax, Natalie Klein, and Brian Opeskin. 2018. “Securitization of Search and Rescue at Sea: The Response to Boat Migration Offshore Australia and in the Mediterranean.” International & Comparative Law Quarterly 67 (2): 315–351.

- Greussing, Esther, and Hajo Boomgaarden. 2017. “Shifting the Refugee Narrative? An Automated Frame Analysis of Europe’s 2015 Refugee Crisis.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (11): 1749–1774. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1282813.

- Heidenreich, Tobias, Fabienne Lind, Jakob-Moritz Eberl, and Hajo Boomgaarden. 2019. “Media Framing Dynamics of the ‘European Refugee Crisis’: A Comparative Topic Modelling Approach.” Journal of Refugee Studies 32 (1): 172–182. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fez025.

- Helbling, Marc. 2013. “Framing Immigration in Western Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (1): 21–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.830888.

- Hintjens, Helen. 2019. “Failed Securitisation Moves During the 2015 ‘Migration Crisis’.” International Migration 57 (4): 181–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12588.

- Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. 2017. “Cleavage Theory Meets Europe’s Crises: Lipset, Rokkan, and the Transnational Cleavage.” Journal of European Public Policy 25 (1): 1–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1310279.

- House of Lords. 2016. “Operation Sophia, the EU’s Naval Mission in the Mediterranean: An Impossible Challenge.” House of Lords. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld201516/ldselect/ldeucom/144/14406.html.

- Huysmans, Jef. 2000. “The European Union and the Securitization of Migration.” Journal of Common Market Studies 38 (5): 751–777. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00263.

- IOM (International Organization for Migration). Undated. Missing Migrants Project, International Organization for Migration. https://missingmigrants.iom.int/region/mediterranean?migrant_route%5B%5D=1376.

- Irrera, Daniela. 2019. “Non-governmental Search and Rescue Operations in the Mediterranean: Challenge or Opportunity for the EU?” European Foreign Affairs Review 24 (3): 265–286.

- Kaunert, Christian, and Sarah Léonard. 2020. Refugees, Security and the European Union. London: Routledge.

- Kim, Sei-hill, John P. Carvalho, Andrew G. Davis, and Amanda M. Mullins. 2011. “The View of the Border: News Framing of the Definition, Causes, and Solutions to Illegal Immigration.” Mass Communication and Society 14 (3): 292–314. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15205431003743679.

- Laclau, Ernesto, and Chantal Mouffe. 1985. Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics. London: Verso.

- Little, Adrian, and Nick Vaughan-Williams. 2016. “Stopping Boats, Saving Lives, Securing Subjects: Humanitarian Borders in Europe and Australia.” European Journal of International Relations 23 (3): 533–556. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066116661227.

- Maneri, Marcello. 2011. “Media Discourse on Immigration: Control Practices and the Language we Live.” In Racial Criminalization of Migrants in 21st Century, edited by Salvatore Palidda, 77–93. Farnham: Routledge.

- McDowell, Sara. 2020. “Geopoliticizing Geographies of Care: Scales of Responsibility Towards Sea-Borne Migrants and Refugees in the Mediterranean.” Geopolitics. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2020.1777400.

- Mezzadra, Sandro. 2020. “Abolitionist Vistas of the Human: Border Struggles, Migration and Freedom of Movement.” Citizenship Studies 24 (4): 424–440. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2020.1755156.

- Moreno-Lax, Violeta. 2018. “The EU Humanitarian Border and the Securitization of Human Rights: The ‘Rescue-Through-Interdiction/Rescue-Without-Protection’ Paradigm.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (1): 119–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12651.

- Palidda, Salvatore. 2011. “A Review of the Principal European Countries.” In Racial Criminalization of Migrants in 21st Century, edited by Salvatore Palidda, 23–30. Farnham: Routledge.

- Pan, Zhongdang, and Gerald Kosicki. 1993. “Framing Analysis: an Approach to News Discourse.” Political Communication 10: 55–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963.

- Parkin, Joanna. 2013. “The Criminalisation of Migration in Europe: A State-of-the-Art of the Academic Literature and Research.” Liberty and Security in Europe CEPS Paper 61: 1–25. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/148870081.pdf.

- Perkowsky, Nina, and Vicky Squire. 2019. “The Anti-Policy of European Anti-Smuggling as a Site of Contestation in the Mediterranean Migration ‘Crisis’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (12): 2167–2184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1468315.

- Quassoli, Fabio. 2013. “‘Clandestino’: Institutional Discourses and Practices for the Control and Exclusion of Migrants in Contemporary Italy.” Journal of Language and Politics 12 (2): 203–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/jlp.12.2.03qua.

- Sallusti, Alessandro. 2015. “Settecento Morti di Buonismo.” Il Giornale, April 20. https://www.andreaspeziali.it/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/20.4.2015-Italian-Liberty-Il-Giornale.pdf.

- Squire, Vicky. 2015. “The Securitisation of Migration: An Absent Presence.” In The Securitisation of Migration in the EU, edited by Gabrielle Lazaridis, and Wadia Khursheed, 19–37. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Steinhilper, Elias, and Ruben Gruijters. 2018. “A Contested Crisis: Policy Narratives and Empirical Evidence on Border Deaths in the Mediterranean.” Sociology 52 (3): 515–533. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038518759248.

- Stierl, Maurice. 2018. “A Fleet of Mediterranean Border Humanitarians.” Antipode 50 (3): 704–724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12320.

- Swarts, Jonathan, and Neovi Karakatsanis. 2013. “Challenges to Desecuritizing Migration in Greece.” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 15 (1): 97–120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/19448953.2012.736238.

- Tazzioli, Martina. 2018. “Crimes of Solidarity: Migration and Containment Through Rescue.” Radical Philosophy 2 (1): 4–10. https://www.radicalphilosophy.com/commentary/crimes-of-solidarity.

- Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2017. “A ‘Refugee Crisis’ Unfolding: ‘Real’ Events and Their Interpretation in Media and Political Debates.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16 (1-2): 198–216. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15562948.2017.1309089.

- Urso, Ornella. 2018. “The Politicization of Immigration in Italy: Who Frames the Issue, When and How.” Italian Political Science Review/Rivista Italiana Di Scienza Politica 48 (3): 365–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/ipo.2018.16.

- Vollmer, Bastian. 2011. “Policy Discourses on Irregular Migration in the EU – ‘Number Games’ and ‘Political Games’.” European Journal of Migration and Law 13: 317–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/157181611X587874.

- Walters, William. 2002. “Secure Borders, Safe Haven, Domopolitics.” Citizenship Studies 8 (3): 237–260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1362102042000256989.

- Watson, Scott. 2009. The Securitization of Humanitarian Migration: Digging Moats and Sinking Boats. New York: Routledge.