ABSTRACT

Drawing on a mix-methods study comprised of an online questionnaire and semi-structured interviews, this article presents findings about the complexity and development in time of health service use by Polish migrants living in the United Kingdom. The article contributes to the analysis of transnational healthcare practices by operationalising a framework that considers service access within and beyond national borders, and between private and public sectors. By categorising engagements with healthcare providers based on their occurrence in time it argues for an understanding of transnational healthcare as a process. It finds that Polish migrants manage their health by accessing a variety of different providers. This complexity is also reflected in the multiple ways in which access to services with regards to specific health issues unfolds in time. By focusing the analysis on specific health issues rather than individuals the article finds that multiple ways to access healthcare services coexist for the same participant, who does not necessarily move towards particular healthcare providers unitarily, but adopts ad hoc solutions on the basis of their experiences within specific medical areas. Understanding migrants’ patterns of accessing healthcare can contribute to more effective policy solutions supporting migrants in the UK today.

This article is concerned with advancing the analytical tools in the analysis of what is conceptualised as transnational healthcare by forwarding the understanding of health practices of Polish migrants in the United Kingdom. These have been previously analysed without considering them as processes that unfold in time dynamically. We fill this gap by addressing three questions. What is the extent of the use of different healthcare services by Poles living in the United Kingdom? How does the use of services change in time? How can we best analyse the complexity of service use within time? We answer these questions by presenting qualitative and quantitative results of a UK-wide mix-methods study on the preferences and experiences in accessing healthcare services in the UK and Poland of adult Poles in the UK. By ceasing to be Polish residents, migrants cannot be insured in the National Health Fund (NFZ) which grants them access to publicly funded healthcare in Poland. During their visits to Poland, they can access public services in case of emergency and they might be able to formally access some public services before their change of residence becomes official, after which they are able to use private services only. By becoming residents of the United Kingdom, they gain access to the British public healthcare system, the National Healthcare Service (NHS). Within the UK they have also access to private services, including those provided by clinics targeting Polish costumers and staffed with Polish professionals. We formulate an understanding of the health-seeking behaviours of this population by operationalising a transnational healthcare analytical framework. Our main contribution consists in proposing an analysis of transnational healthcare built upon the distinctions between public/private and national/transnational healthcare providers which considers the shifts in time between these services.

We develop our analysis following the methodological trajectory of the mixed-methods sequential study on which this paper is based. First, we review the literature relevant to our discussion and outline our contribution to it. Second, we present the methodology and the primary data used in this article. Third, we analyse the results of our online survey taken by adult Poles living in the UK (N = 510). By applying our transnational healthcare framework, we show the extent of the use of services in our sample and the multiplicity of service combinations on an individual level. Fourth, we introduce a temporal dimension into the analysis and develop three categories based on the evidence from the qualitative answers of the survey combined with the material from the semi-structured interviews (N = 32) conducted with the questionnaire respondents after the survey closed. We show the advantage of understanding access to health services within a transnational framework as a process unfolding in time, which adds to the multiplicity of service combinations a variety of shifts and continuities between these services. Finally, we present an analysis of the experiences with healthcare services that highlights the multidirectionality of different services used by the same participant. We apply our analysis to three case studies selected from the interviews we conducted.

Review of literature: mapping healthcare service use

Increasingly, migrants’ use of healthcare in their host country is coupled with a scrutiny of their access to health-related services in their country of origin. The merging of these two fields of inquiry is prevalent within a transnational framework. Transnational approaches with a focus on people’s access to services beyond national borders have recognised the contribution of both medical tourism and migrant health literatures, highlighting the attachments and links between places and health systems that each of them makes (Ormond and Lunt Citation2019). Migrants’ access to healthcare beyond the nations where they reside can be considered as an instance of wider movements of patients across borders, long understood either as a public health issue or as a market development phenomenon. Approaching the topic from a macro perspective, Botterill and colleagues (Botterill, Mainil, and Pennings Citation2013, 3) similarly attempt a marriage of two previously separated fields. They acknowledge the increasing fuzziness of the boundary between these two understandings, the former summarised by the term ‘medical tourism’ while the latter by ‘cross-border health care’, and propose the operational term ‘transnational health care’. Their intention is twofold: encourage the integration of public health and market development perspectives (and stakeholders), and start the development of a ‘global patient mobility framework, which builds on a logic of transnational health regions […], transnational organisations […] and sustainable health destination management’ (Ibid., p. 3). While this proposal rests upon an analysis at the macro-level of organisations, regions, and between states, it does show the non-exclusivity of perspectives that consider the patient as consumer or citizen, especially within the European context (Mainil, Commers, and Michelsen Citation2013).

Thus, a transnational perspective enables two interrelated dimensions to emerge as crucial for an analysis of healthcare management by migrants. First, the necessity of considering the use of services both within and beyond national borders. Second, the acknowledgment that this utilisation needs to be considered in relation to both state and market. Moreover, by focusing on transnational healthcare, we aim to avoid reducing our analysis to supply or demand logics, or describing our participant solely as consumers or patients, and instead treat transnational healthcare as a specific instance of transnationalism (Stan Citation2015). In this article, we contribute to the body of scholarship on transnational healthcare by operationalising these two aspects in the analysis of healthcare access by Poles living in the United Kingdom. Of the 6 million non-British Nationals living in the UK, Poles constitute the biggest group with 815 thousand estimated residents (ONS Citation2020). They are prone to travel back to their country of origin (Burrell Citation2011) and to access healthcare in Poland (Horsfall Citation2019), the latter within a more general trend of Europeans living in the United Kingdom (Moreh, McGhee, and Vlachantoni Citation2018). Poles residing in the UK have a varied use of services both nationally and transnationally, between public and private sectors. Together with the use of the NHS, research indicates that Poles access to private medical services in Poland and private polish clinics in the UK (Osipovič Citation2013; Reading Citation2014; Main Citation2014; Bell et al. Citation2019; Smoleń Citation2013a).

It is still unclear the extent to which these different services are used, how varied the access to them is for singular users and how it changes in time. A growing number of studies using qualitative and quantitative data explores the health and health service of Poles living in the UK. Quantitative studies have focused on specific medical concerns, services or localities. These comprise studies about HPV vaccine acceptance in Scotland (Pollock et al. Citation2019), influenza vaccine acceptance in Edinburgh (Bielecki et al. Citation2019), suicide in Scotland (Gorman et al. Citation2018), experiences of maternity care in England (Henderson et al. Citation2018), mental health help-seeking in the UK (Gondek and Kirkbride Citation2018), medical care perceptions of pregnant women in the UK (Kazmierczak et al. Citation2016), stress levels and coping strategies in England, Scotland and Ireland (Ziarko et al. Citation2014), general health problems (Smoleń Citation2013a) and stress (Smoleń Citation2013b) in London, Edinburgh and Glasgow, use of emergency services in Telford (Leaman, Rysdale, and Webber Citation2006). Qualitative studies have also focused on experiences in circumscribed localities and with regards to specific medical needs, such as vaccine (Gorman et al. Citation2019) and breast screening uptake in Lothian (Gorman and Porteous Citation2018), use of healthcare services in London (Osipovič Citation2013), maternity services in Scotland (Crowther and Lau Citation2019), vaccination and primary health service access in London, Lincolnshire and Berkshire (Bell et al. Citation2019), experiences of the UK health service in northern England (Madden et al. Citation2017), children’s health and wellbeing in Bristol (Condon and McClean Citation2016), experiences of women in London (Main, Citation2016), attitudes to antibiotics (Lindenmeyer et al. Citation2016), views and experiences of the Scottish health service (Sime Citation2014), cervical screening in London (Jackowska et al. Citation2012), stress in Edinburgh (Weishaar Citation2010, Citation2008). Within this literature, there is a lack of explicit focus on change in services accessed within time. One study taking into consideration recency of migration found that women recently migrated from Poland, and other nine countries that joined the EU since 2004, had more negative experiences of their maternal care and had more contact with midwives after giving birth in comparison with women who had been in the UK for more years (Henderson et al. Citation2018). In one longitudinal mix-methods study investigating perceptions of health and interactions with the NHS the aspect of change is tackled in terms of perceived health rather than service access and limited to the first 21 months after migration (Goodwin, Polek, and Goodwin Citation2012). Our contribution to this literature consists in providing a holistic view of Poles’ access to different services at the UK-wide level by bringing together primary qualitative and quantitative data and focusing on the shifts between different providers in time.

Based on interview data from 62 Polish migrants residing in London collected in 2007–2008, Osipovič (Citation2013) outlined participants’ engagements with the NHS and private services in the UK and Poland, arguing that it is key ‘to include the aspect of change over time in studies of migrant health care seeking behaviour' (Ibid., 111). Notwithstanding this call, a dynamic and processual analysis of healthcare access among Polish migrants in the UK is still lacking. Studies commonly consider the multiplicity of experiences held by migrants as a premise to account for motivations and expectations that inform behaviour (Main Citation2014; Madden et al. Citation2017; Sime Citation2014; Goodwin, Polek, and Goodwin Citation2012; Bell et al. Citation2019; Lindenmeyer et al. Citation2016; Crowther and Lau Citation2019; Gorman et al. Citation2019). Instead, we focus on medical experiences themselves as generative of changes and continuities in service use trajectories over time. Our analysis of transnational healthcare incorporates how services (public, private and between nations) are accessed over time throughout one’s healthcare biography. By including the temporal dimension in our analysis, we argue that transnational healthcare needs to be considered as a process.

The consequences of this are twofold. On the one hand, we inscribe transnational healthcare firmly within the broader transnational paradigm. In fact, while transnationalism has historically allowed the recognition of multiple and simultaneous ties across national borders, it has to be understood primarily as a process (Glick Schiller, Basch, and Blanc-Szanton Citation1992). As with other aspects of transnationalism, connections across borders are simultaneous, and ‘Movement and attachment is not linear or sequential but capable of rotating back and forth and changing direction over time.’ (Levitt and Schiller Citation2004, 1011) On the other hand, we recentre transnational healthcare on the agential aspect of health-seeking behaviour of the migrant vis a vis different services and professionals (positioned transnationally). Indeed, by developing an analysis that focuses on experiences of service use, we bring to the fore our participants’ agency, understood primarily as ‘a temporally embedded process of social engagement’ (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998, 963), that in our case unfolds transnationally. Agency in transnational spaces is articulated through social relations and by comparisons between past and present across national borders (McGhee, Heath, and Trevena Citation2012). We situate health practices as outcomes of ongoing post-migratory engagements between different providers across nation states and sectors.

Increasingly under scrutiny, common models that describe migrants’ behaviors and attitudes in the country of settlement often describe migrants’ more or less linear pathways of acculturation (Saharso Citation2019), adaptation or settlement (Grzymala-Kazlowska and Phillimore Citation2018) and focus on the individual or group as the unit of analysis. As our empirical findings show, migrants’ health-seeking practices are not only complex because of the multiplicity of the creative solutions adopted to access healthcare – as already described by Phillimore et al. (Citation2019) through their concept of healthcare ‘bricolage’ – but also because engagements in time that are not necessarily linear or unidirectional. Thus, another argument we put forward in this article is that to account for the complexity, multiplicity and multidirectionality of access to healthcare, the analysis needs to move between the individual level of experience and the sub-individual level of engagements with health conditions and medical areas of expertise.

Data and methods

Our data originates from a sequential mixed-methods study investigating how Poles living in the UK manage their healthcare needs by accessing health services within and beyond national borders. The study involved an online survey (N = 510) followed up with semi-structured remote interviews with selected survey participants (N = 32).Footnote1

Survey design

The online survey was conducted between 15 November 2019 and 9 February 2020. It was administered both in Polish and English, and it took respondents 21 min on average to complete (min = 3, max = 124, standard deviation = 14.1). The survey was open to citizens of Poland who were living or had lived before, in the United Kingdom, were over 18 years old and had consulted a medical professional for non-emergency treatments at least once after moving to the UK. The questionnaire included questions concerning transnationalism, access to various public and private healthcare services across national borders, more detailed specific items for those with chronic conditions or primary carer responsibilities, as well as questions on health-related and demographic characteristics. The survey also contained several open-ended answer boxes, where respondents provided detailed descriptions of their healthcare experiences.

As a tool of exploratory data generation, the self-selected online survey was not designed to obtain a representative sample of Polish migrants, but to collect detailed information on the variety and complexity of service use among the largest transmigrant national group in the UK. The questionnaire was distributed to respondents of a previous survey via email, by posting in Facebook groups of Poles living in the UK, and through two UK-based online Polish newspapers who advertised the survey on their websites and Facebook pages. This targeted data collection strategy has been recommended in the case of hard-to-reach populations (Temple and Brown Citation2011) and has previously proven adequate for achieving samples of Poles in the UK with core demographic characteristics in line with those recorded by administrative surveys (McGhee, Moreh, and Vlachantoni Citation2017). The socio-demographic characteristics of the resulting sample are summarised in .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Interview design

Following a preliminary analysis of the survey results, semi-structured interviews were designed using an explanatory sequential approach aimed at deepening our understanding of the survey results (Creswell Citation2015). Semi-structured interviewing allowed participants to openly expand upon the research and provided the flexibility to adapt the interview guide to individual experiences and circumstances (Brinkmann Citation2013).

Interviewees were selected from among survey participants who had agreed to be contacted for follow-up research (N = 297, 58%) based on their medical and socio-demographic characteristics. Since the aim of the qualitative stage of the project was to understand complex engagement patterns as they develop throughout individual healthcare life courses, we recruited interviewees from among those with long-term/chronic health conditions developed either before (N = 49) or after migration to the UK (N = 68), and/or those with primary carer responsibilities for a person diagnosed with a long-term condition or disability (N = 53). From this purposeful pool sample of 144 potential interview participants, we selected 32 interviewees based on maximum variation criteria in respect to gender, age, employment, family composition and experienced medical conditions. lists the main characteristics of the interview sample.

Interviews took place between 3 June and 27 August 2020. They were undertaken by the lead author in Polish – except for one which was conducted in English as per the preference of the interviewee – and lasted 64 min on average, with a range of 36–110 min. The interviews were conducted over phone (except for one made via computer using audio-communication software) due to the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, and they were audio-recorded. Beyond serving as a convenience measure, remote interviewing has been described as an effective method to enhance the sense of anonymity (Oltmann Citation2016), which is particularly desirable when discussion topics are of a personal and potentially sensitive nature.

The interview guide included themes expanding on the main survey questions on healthcare behaviour in order to understand the context of healthcare-seeking practices, their interconnections, and changes throughout the life course of interviewees. Reflections on the early effects of the COVID-19 pandemic were necessarily included as an emergent theme, as were thoughts on future access to transnational healthcare and life following the Brexit transition period. Interviews were professionally transcribed and translated into English. The transcripts were thematically coded using NVivo 1.4.

Analytic approach

The analysis presented in this paper relies primarily on the qualitative data obtained through the semi-structured interviews and the open-ended survey questions. Following our sequential study design, the initial layer of thematic coding emerged from categories and concepts derived from the survey data; subsequent analysis has identified secondary emergent themes and focused on capturing processual dynamics and path dependencies in healthcare engagements and transnational care choices following ‘an inductive approach, allowing for an iterative and ongoing pursuit of meaning' (Galletta and Cross Citation2013, 18).

We present results from our analysis in the next sections by first providing a quantitative overview of healthcare service use in order to capture the multiplicity of the practices; we then summarise a proposed typology of healthcare trajectories as they emerged from the qualitative material; finally, to exemplify the processual dynamics of healthcare trajectories, we discuss three individual case studies selected for their heterogeneity in terms of the interviewees’ circumstances and health conditions, and their diversity of engagements with different providers.

Multiplicities of service use

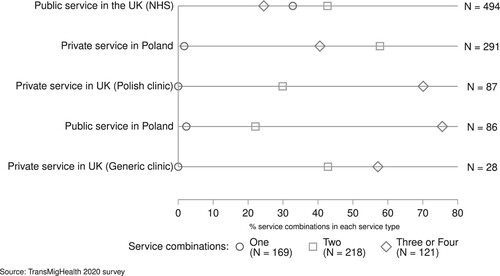

We first examine the extent of the use and combinations of healthcare services across transnational space and financing methods. In other words, we are interested in understanding how diversified healthcare service use is. For this purpose, we analyse quantitative data from the online survey. A multiple response question with four general answer options asked about the services that respondents, their children, or dependent parents, have used since they arrived in the United Kingdom. We have found that almost all of the respondents had used public health services in the UK (i.e. the NHS) (N = 494, 97%) and more than half had used private services in Poland (N = 291, 57%). Fewer respondents used private Polish clinics in the UK (N = 87, 17%) or public services in Poland (NFZ) (N = 86, 17%), and only a small minority had used generic private services in the UK (N = 28, 6%). These service use patterns confirm the prevalence of both cross-national travel and engagement with local Polish providers in the UK as a form of transnational healthcare ().

We further find that the relative majority of respondents use a combination of two of these services (N = 218, 43%). Somewhat fewer (N = 169, 33%) use only one service (almost all the NHS). Only 103 (20%) respondents combined three different service types, and only 18 (4%) combined all four service types. plots the types of services used against the number of service combinations and we can see that public service use in Poland and the use of private Polish clinics in the UK are most often combined with at least two other service types, while private services in Poland and the NHS are most commonly used in combination with one other service. The NHS is the only service which is used in isolation from other services by a relevant number of respondents.

While captures the general multiplicity of service use combinations, lists more clearly the different combinations that emerge empirically. The two largest user categories are those relying solely on the NHS (N = 162, 32%) and those combining NHS with private healthcare in Poland (N = 161, 32%). The remaining two-thirds of the respondents use various other service combinations ().

Table 2. Service combinations.

While this overview provides a useful snapshot of the complexities involved in transnational healthcare seeking, it also conceals the dynamic nature of these complex practices. As we discuss next, engagements with service providers are further complicated by the multiplicity of trajectories existing not only at the individual level but also at the level of specific medical areas and conditions.

Transnational healthcare trajectories

Considering how participants narrate their medical histories in their own words allows us to add temporal depth to the analysis. We have synthesised in the different engagements described by our participants when referring to a particular illness, health issue or medical specialism both in the survey and the interviews.

Table 3. Types of engagement.

The engagements summarised in consider the time since the arrival in the United Kingdom and exclude the use of emergency procedures in isolation from other services. They can be divided into linear, nonlinear, and singular. Linear engagements refer to instances where participants either always use the same provider or, once they change it, they use continuously and exclusively the new provider, without returning to the previous one. Nonlinear engagements are defined by circularity between service providers: at a certain point, there is a return to a service provider previously accessed. We call singular engagements those cases in which access to a medical service (outside the NHS) for a specific health issue consists of only one session. In these cases, a peculiar health issue is resolved by a one-off treatment and is usually an isolated occurrence in the history of care of the person, or when use of a service in Poland (instead than in the UK) happens merely because when the treatment was needed the person was visiting the country for other reasons.

Coupled with the variety of combinations of services, the types of service use in time adds a further layer of complexity in the analysis of transnational healthcare practices. The multilinearity of engagements emerging from considering changes and continuities in service access through time shows the necessity of considering the processual dimension of transnational healthcare. Having established that different patterns of service use exist, our data shows that they are coupled with an equally diverse array of shifts between services and that these are not necessarily unilinear or do not follow binary logics of either from public to private, or from national to transnational, and vice versa. Further, the types of engagements that we have described above apply to singular health issues or specialisations. This means that while the same participant may engage uniformly when it comes to all their health needs, for instance accessing only public services in the United Kingdom, it is often the case that the same person can, with regards to different health issues, engage with providers in several different ways.

Our research shows that even linear engagements are not necessarily corresponding to simple or unproblematic health conditions or treatments. They reveal how specific experiences with the public health sector in the host country can lead to perseverance with treatments within it or to change which often involves access to transnational services. Initial healthcare experiences in the UK are shaped by the various difficulties faced by migrants from Eastern European countries when accessing British healthcare services (Phung et al. Citation2020); we know, for instance, how a considerable proportion of Polish migrants in the UK report limited access to services (Nartowski Citation2018). Singular engagements reveal the at times impromptu nature of transnational engagements that result from travel to the country of origin in itself. Moreover, they shed light on the fact that premeditated healthcare does not necessarily lead to persistent and constant use of transnational services, but can remain an ad hoc intervention. When it does, it highlights the processual nature of transnational healthcare practices, which from occasional can become multiple or enduring (cf. Pordié Citation2013), or, to use our typologies, from singular develop into linear or nonlinear.

Case studies of healthcare trajectories

In the previous section, we have described engagements on the grounds of their multilinearity. In this section, we ask: How can we effectively analyse this complexity of engagements? We answer by proposing an analysis that considers experiences from two perspectives. The first analytical perspective that we advance is to group and juxtapose experiences from these case studies as linear, nonlinear and singular, to show how complex experiences with particular health issues are. A second analytical perspective is to group experiences of linear, nonlinear and singular engagements with healthcare services by singular individuals. From this it emerges how diversified an individual, and familial, experiences can be and how different engagements the same person can have depending on the health issue. The same person can use services purely nationally and publicly for a condition, purely transnationally for another, and can juggle health systems for yet another, in pathways that are linear or nonlinear (and with singular episodes) for different health needs. Moreover, the directionality towards or from transnational use of services can be different for different health issues in the same person.

When looking at participants’ overall use of services we identify cases in which there is a tendency towards transnational services use or national public healthcare or instances of exclusive reliance on it or the opposite. However, by centering our analysis on the ways in which people move between services for particular health issues rather than the overall tendencies in using healthcare by the individual within a transnational healthcare framework that accounts for time, we are able to show the existence of different directionalities even within the same participant. Below, we apply our analysis to three selected individual case studies.

Dorota

Dorota, a woman in her early 50s, has been living in the UK for eleven years and owns two small businesses. She lives with her husband and the youngest of her two adult children. Dorota’s narrative of her medical history in the UK stretches back to a few years ago when she was prescribed contraceptive tablets from a family planning clinic which induced profuse bleeding. Doctors at the same clinic advised her to continue taking the drug, but because her situation was not improving she consulted her GP who referred her to a gynaecological appointment. Dorota was not contacted for some time and discovered at her GP surgery that no specialist appointment had been made because there were no places available at the local hospital. Frustrated about the delay and experiencing difficulties in carrying on working under those circumstances, she asked her husband to call the referral service and obtained an appointment to a different hospital for a few weeks later. However, instead of waiting a few more weeks, Dorota went to a private Polish gynaecologist who was able to stop her bleeding. As a result of the bleeding, she developed anaemia, which delayed by a month an operation she had scheduled. Eventually, the operation took place and she was satisfied with the care received at the hospital.

Five years later she went again to her GP for a referral to see a specialist to change a contraceptive implant she was carrying. Once again, her appointment got cancelled without being notified and she had to go back to her GP to reschedule it. Dorota recalls how she ‘had to explain everything again and this time I got the referral, but again, it all lasted around six months … It’s just torturous … To get an appointment with a gynaecologist here is just a nightmare, and so I started doing everything privately. I simply don’t want to lose my health over it … '

Another crucial chapter in Dorota’s medical history in the UK was when she was suffering from headaches so strong as to affect her ability to work. She was referred by her GP for an MRI scan, but while waiting for the results she undertook blood tests privately which showed that she might have a muscular inflammation. Her GP, after having scrutinised the test results, argued that nothing was wrong with Dorota since the MRI did not show abnormalities. According to the doctor, the blood test results could not have any connection with the headaches since, ‘there are no muscles in the head' – a statement interpreted by Dorota as an instance of incompetence. Frustrated by not having her health issue solved after much waiting and pain, Dorota went to see a private Polish neurologist in the UK. The specialist identified the source of the pain in the connective tissue joining the muscles and bones of the cranium and prescribed a drug that made the headaches which had persisted for months disappear in a matter of days. After having tried out several private Polish clinics in the UK, Dorota currently mainly frequents one that is an hour away by car from her house, and where there are the ‘best doctors’ in her opinion. It was at that clinic that she was diagnosed with diabetes more recently, for which she is being medicated.

Although not often, Dorota visits Poland particularly to sort out non-health-related matters, but usually also takes advantage of these visits to see a healthcare professional if needed. Sometimes less urgent but potentially consequential medical checks are put on hold until travel to Poland for another matter is planned, and such behaviour emerges in Dorota’s medical history too. Three years ago she discovered a tick attached to her skin upon returning to the UK, but it was not possible to remove it for lack of tools at her GP practice. She managed to get it removed at a veterinary clinic where she asked for assistance. Unsure if to take an antibiotic or not, Dorota refrained from it, was tested for Lyme disease and was reassured that the test was negative but she did not receive the results. Lacking test results to show to a specialist chosen by her and unsure of where and how to undertake another test privately in the UK, she waited until recently to be tested in Poland.

There are also instances in her medical history when travel to Poland was coupled with – or was primarily driven by – planned healthcare treatments. Once, after the antibiotics prescribed by her GP to treat a rash proved ineffective, she asked specifically for a drug she knew was used in Poland. The new drug seemed to improve her condition and to find out whether it had neutralised the bacteria, she travelled to Poland to be tested, claiming that the tests for that disease are more reliable there than in the UK. She has also travelled multiple times specifically to accompany her youngest child to get a dental prosthesis. However, having seen how many trips this took, she decided to have the same procedure carried out for herself at a Polish dental clinic in the UK.

Zbigniew

A man in his early 50s, Zbigniew has been in the UK for six years. He lives with his wife and adult son and daughter, their partners and toddler child. He used to work as a driver in a warehouse before his health deteriorated a year earlier and left him unable to walk and work. He had started experiencing pain in one of his hips, carried on working thinking that it was an extemporary pain, but when it got increasingly worse, he consulted a doctor who could not identify any problem and reassured him that there was nothing wrong with it. As the pain persisted, Zbigniew went for a private X-ray in Poland. He also got examined by an orthopaedist who warned that the situation with his hips was serious and needed to be attended to. A couple of months after his return to the UK, while at work, he could not walk anymore and had to be taken home. His GP swiftly referred him to an orthopaedist and in the next five months, he had both hips operated on.

After his second operation, Zbigniew was also experiencing tennis elbow, a condition that causes pain in the arm. After a scan and two injections, the pain only worsened, and he was referred to a physiotherapist. The physiotherapist then referred him for an MRI scan which indicated that Zbigniew was probably suffering from arthritis. At the time of our interview, he was waiting to see an orthopaedist, but his appointments have been repeatedly postponed due to the Covid-19 pandemic. For the same reason, he could not attend the last of his sessions with an NHS-referred psychologist with whom he had previously eight meetings after experiencing depression due to his inability to work, being left financially dependent on his wife and partially his children. He had enjoyed the sessions and the fact that the practitioner was Polish was of great relief because of his very limited English proficiency.

Zbigniew is also grappling with health issues that first manifested when he was still living in Poland. For years he had had frequent headaches caused by high blood pressure. The drug prescribed by his GP to replace the tablets he had used in Poland proved just as efficient and he was satisfied; ‘but in terms of the liver disease, it hasn’t been that straightforward’, says Zbigniew. Around the age of thirty, he was diagnosed with cirrhosis, a scarring of the liver considered life-threatening as it can lead to liver failure and serious complications. In Poland, he had been medicated for the condition and the cirrhosis was brought under control; however, in the UK, despite his medical documentation from Poland, his GP remained unconvinced that he had the condition because several tests did not find anything wrong with his liver. Knowing that only more in-depth examinations could have highlighted his illness, but not wanting to challenge the doctors, Zbigniew simply resorted to being regularly monitored privately in Poland. While not currently medicated for his liver, he takes supplements and herbal remedies from Poland and follows an appropriate diet. Another aspect of his healthcare that is dealt with in Poland is dentistry. He and his whole family have always only consulted a dentist in Poland.

Paulina

Paulina is a woman in her mid-30s, living with her husband and her two teenage children. She has been in the UK for fourteen years and works as a beautician from her home. When she was a child, she contracted mumps and her hearing started to deteriorate. Her overall health condition worsened after she had her first child in the UK. After giving birth, she lost hearing completely in one ear and considerably in the other. She also developed migraines which provoked sight problems. Her GP referred her to an otolaryngologist (ear, nose and throat surgery or ENT), to whom she recounted how her hearing impairment meant that she had serious difficulties in communicating, especially in noisy and busy environments: ‘So I told that doctor all about it, to which he told me to come back when I’m deaf in the other ear too … I just stormed out of that room, went back to my GP and asked for another referral … ’, says Paulina recounting her encounter with the specialist. She was referred for a consultation in a second hospital. Because the transfer was taking some time, Paulina had hearing tests and other diagnostic procedures carried out in Poland. Once she started to be monitored in the second hospital, the approach of the new specialist reassured Paulina, who continues to be cared for by the specialist:

My ENT doctor is really great. She told me that if I have any problem, I can get in touch with her by email, and if it was urgent, that I could come to the hospital at any point, without having to make an appointment. She’s great and has really helped me.

Because of her various comorbidities – including kidney and thyroid dysfunctions – Paulina receives yearly medical checks in the UK, but she also repeats the blood tests in Poland to double-check their accuracy and because she knows of differences in what hormone levels are considered pathological in the two countries. The results were, so far, consistent.

Paulina has also gained experience with the healthcare sector as a mother. Her eldest child had tonsillitis and after this started to impact his hearing, he underwent a surgery, about which she was very pleased. She had different experiences with her youngest child. In his infancy, he developed laryngitis while in Poland for a visit. There he has prescribed inhaled antibiotics, of which Paulina sourced a consistent quantity in case the condition resurfaced while in the UK. The child was in possession of a European Health Insurance Card which enabled him to be seen within the NFZ. The doctor also diagnosed her son with asthma, but back in the UK, she was told that it was not possible to diagnose asthma in children under three. In the UK, he ‘started getting proper treatment’ only when found with ‘severe anaemia’ following repeated visits to the hospital emergency services because of breathing problems. Paulina recalls how they ‘were referred to a haematologist, pulmonologist and later to an allergist, and he’s under this specialist care to this day. When he turned three, he was diagnosed with asthma … ’. Nevertheless, when it comes to her children, apart from eventual emergencies occurring during visits in Poland, Paulina gets ‘everything done here. I think that healthcare for children is good in the UK; they respond really quickly … ’

Reflections on the case studies

The three case studies presented here are heterogeneous in terms of participants’ gender, age, economic circumstances, familial arrangements, time of residency in the UK and health conditions. Nonetheless, they all show how variegated service use can be, between public and private sectors in both the UK and Poland. We find some linear engagements of different kinds. An instance of this is Zbigniew’s case. He’s accessed his dental care always in Poland, and the uncomplicated way in which his high blood pressure was easily recognised and medicated by his GP meant that he is only accessed the public sector in the UK for it. For his liver condition, he sought care within the public sector in the UK, but investigations did not evidence traces of the health issue which once caused him to fear for his life, and wanting to be monitored but not desiring to enter in conflict with professionals over diagnosis, he shifted to regular check-ups in a trusted institution in Poland, while using Polish remedies as a mild treatment. His mental wellbeing has been taken care of by the public sector, but the treatment’s limited duration meant that he was left in need of support yet unassisted. Paulina’s psychological care has also followed a linear path, as she always accessed a NHS-provided psychologist, a service that is ongoing for her happiness. Her children have also followed a linear pathway of engagement with NHS services. In one instance exclusively, in the other punctuated by the episodic access to public healthcare in Poland. The latter is an instance of a type of engagement which we have called singular, in this case unintended since the child got ill while in Poland for a visit. Another singular engagement, but pre-arranged, was Zbigniew’s private consultation and test in Poland when he felt that he had to further investigate the state of his hips after experiencing the discrepancy between his pain and the assessment of the public healthcare doctor.

Dorota’s search for reassurance about Lyme disease was also initially an instance of singular engagement, in the form of a one-off treatment following an isolated event. However, since the first time she experienced unpreparedness for the specific health issue, when she was bitten for the second time she returned to the use of private healthcare in Poland, as well as approaching the public sector in the UK. Thus, she effectively adopted a nonlinear approach in dealing with this specific health issue. In another nonlinear engagement, she complemented different tests between the public and the private sector, and then identified a lack of competence in her encounter with the public practitioner, subsequently moving to consult doctors within the Polish private sector in the UK. Her gynaecological treatments similarly moved between these two providers, following her experiences of delays, complications and inefficiency. Migrants do not necessarily abandon the public healthcare service altogether following a single negative experience, and often supplement public healthcare with private interventions or tests. Alongside complementing national public healthcare with transnational services, migrants mirror the two, as in the cases when the same service is parallelly sought from both providers. Equally, in nonlinear engagements when a shift towards a particular service happens is often the result of multiple experiences with various healthcare providers, rather than the result of a single experience. What emerges by grouping experiences by the three typologies we proposed suggests also their permeability, which further stressed how engagements with providers are ongoing processes. For instance, Dorota’s case with tick bites shows that a (transnational) experience that proved satisfactory was repeated in the future. Indeed, rather than static and self-confined, our typologies based on time are also subject to change when taking into consideration one’s engagement with a particular health issue. Thus, from linear and singular engagements emerges that change or continuity in service use can be demarcated by a clear shift towards a different service provider or punctuated by episodes of transnational healthcare that are only temporary. Conversely, nonlinear engagements point to the fact that access to multiple providers can be a prolonged or enduring mode of health management.

Further, it is possible to group these different engagements by single users. Dorota uses predominantly Polish private services in the UK when it comes to specialist care. Nonlinear engagements between public and private sectors shifted towards increased use of private services within the UK for singular health issues related to gynaecological and neurological care she gradually shifted towards the latter while accessing healthcare in Poland for ad hoc procedures. Zbigniew predominantly uses the British public sector, but his liver and dental care is monitored exclusively in Poland. While between countries, his engagements were overall linear and mainly with the NHS apart for selected issues. Paulina’s specialist care happens within the British public health sector, while she constantly accesses private services in Poland in search of reassurance. Hers is a case of enduring linear and nonlinear engagement, while her healthcare is managed mainly within the NHS. Participant’s use of services can tend towards transnational or national public services. Nonetheless, this does not imply a complete reliance on either, or that these trends necessarily apply to all medical issues for which consultation, treatment or monitoring is needed.

Conclusion

In this article, we have asked what is the extent of the services used by Poles living in the United Kingdom, how it changes in time, and how to best analyse it. To answer each of these questions we have followed the methodological trajectory of our study. Our contributions have been at once to the development of an analysis of transnational healthcare and the empirical literature on Poles’ access and use of healthcare services. First, we operationalised a transnational healthcare framework that considers service access within and beyond national borders, and between private and public sectors. This has led us to describe the multiplicity of ways in which participants in our study manage their health. The combinations of services used are highly varied: from relying completely on the NHS by some to utilising only the private sector by others. Second, we have introduced time in our analytical framework and categorised engagements with healthcare providers as linear, nonlinear and singular depending on how access to services for specific health needs occurred in time. We have shown that service access is multilinear. That is, the use of services is also varied from a temporal perspective: from continuous access to the same provider, to constant juggling between different sectors, to once-in-a-time utilisation. Thirdly, we have concurrently grouped engagements with providers by different participants according to the categories describing shifts in time, and considered engagements corresponding to different categories within the same participants. By moving our analytical unit from participant to health issue we have found that the same user can access different services and change towards different providers depending on the health need, and that directionality towards (or away from) public, private, British or Polish services can be multiple for the same participant. We have argued that transnational healthcare needs to be considered as a process and that the study of health-seeking behaviour within a transnational context needs to take into account the multidirectionality of engagements by the same service user. That is, it needs to consider how an individual in the process of engaging with healthcare services can act differently depending on their experience in various areas of medical expertise and with different illnesses.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the people who took the time to complete our survey and especially to those who shared their views and experiences during the interviews. The authors have contributed to this article in the following ways. Giuseppe Troccoli: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Visualisation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. Chris Moreh: Conceptualisation; Formal analysis; Methodology; Supervision; Visualisation; Writing – review & editing. Derek McGhee: Conceptualisation; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Supervision; Writing – review & editing. Athina Vlachantoni: Conceptualisation; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Supervision; Writing – review & editing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Ethical approval granted by the Research Integrity and Governance team and the Faculty of Social Sciences Ethics Committee (52861, 52861.A1) at the University of Southampton.

References

- Bell, Sadie, Michael Edelstein, Mateusz Zatoński, Mary Ramsay, and Sandra Mounier-Jack. 2019. “‘I Don’t Think Anybody Explained to me how it Works’: Qualitative Study Exploring Vaccination and Primary Health Service Access and Uptake Amongst Polish and Romanian Communities in England.” BMJ Open 9: e028228.

- Bielecki, K., A. Kirolos, L. J. Willocks, K. G. Pollock, and D. R. Gorman. 2019. “Low Uptake of Nasal Influenza Vaccine in Polish and Other Ethnic Minority Children in Edinburgh, Scotland.” Vaccine 37: 693–697.

- Botterill, David, Tomas Mainil, and Guido Pennings. 2013. “Introduction.” In Medical Tourism and Transnational Health Care, edited by David Botterill, Guido Pennings, and Tomas Mainil, 1–9. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brinkmann, Svend. 2013. Qualitative Interviewing: Qualitative Interviewing. Cary, United States: Oxford University Press, Incorporated.

- Burrell, Kathy. 2011. “Going Steerage on Ryanair: Cultures of Migrant air Travel Between Poland and the UK.” Journal of Transport Geography 19: 1023–1030.

- Condon, L. J., and Stuart McClean. 2016. “Maintaining Pre-School Children's Health and Wellbeing in the UK: A Qualitative Study of the Views of Migrant Parents.” Journal of Public Health 39: 455–463.

- Creswell, John W. 2015. A Concise Introduction to Mixed Methods Research. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Crowther, Susan, and Annie Lau. 2019. “Migrant Polish Women Overcoming Communication Challenges in Scottish Maternity Services: A Qualitative Descriptive Study.” Midwifery 72: 30–38.

- Emirbayer, Mustafa, and Ann Mische. 1998. “What Is Agency?” American Journal of Sociology 103: 962–1023.

- Galletta, Anne, and William E. Cross. 2013. Mastering the Semi-Structured Interview and Beyond from Research Design to Analysis and Publication. New York: New York University Press.

- Glick Schiller, Nina, Linda Basch, and Cristina Blanc-Szanton. 1992. “Towards a Definition of Transnationalism: Introductory Remarks and Research Questions.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 645: ix–xiv.

- Gondek, Dawid, and James B Kirkbride. 2018. “Predictors of Mental Health Help-Seeking among Polish People Living the United Kingdom.” BMC Health Services Research 18: 693.

- Goodwin, Robin, Ela Polek, and Kinga Goodwin. 2012. “Perceived Changes in Health and Interactions With “the Paracetamol Force” A Multimethod Study.” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 7: 152–172.

- Gorman, D. R., K. Bielecki, L. J. Willocks, and K. G. Pollock. 2019. “A Qualitative Study of Vaccination Behaviour Amongst Female Polish Migrants in Edinburgh, Scotland.” Vaccine 37: 2741–2747.

- Gorman, Dermot, Rachel King, Magda Czarnecka, and Feniks Wojtek Wojcik. 2018. “A Review of Suicides in Polish People Living in Scotland.” ScotrPHN Report. https://www.scotphn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/2018_10_31-ScotPHN-Polish-Suicide-Final-1.pdf.

- Gorman, D. R., and L. A. Porteous. 2018. “Influences on Polish Migrants’ Breast Screening Uptake in Lothian, Scotland.” Public Health 158: 86–92.

- Grzymala-Kazlowska, Aleksandra, and Jenny Phillimore. 2018. “Introduction: Rethinking Integration. New Perspectives on Adaptation and Settlement in the Era of Super-Diversity.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (2): 179–196.

- Henderson, Jane, Claire Carson, Hiranthi Jayaweera, Fiona Alderdice, and Maggie Redshaw. 2018. “Recency of Migration, Region of Origin and Women's Experience of Maternity Care in England: Evidence from a Large Cross-Sectional Survey.” Midwifery 67: 87–94.

- Horsfall, Daniel. 2019. “Medical Tourism from the UK to Poland: How the Market Masks Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (20): 4211–4229.

- Jackowska, Marta, Christian von Wagner, Jane Wardle, Dorota Juszczyk, Aleksandra Luszczynska, and Jo Waller. 2012. “Cervical Screening among Migrant Women: A Qualitative Study of Polish, Slovak and Romanian Women in London, UK.” Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care 38: 229–238.

- Kazmierczak, Maria, Agnieszka Nowak, Beata Pastwa-Wojciechowska, and Robin Goodwin. 2016. “Polish Baby Boom in United Kingdom – Emotional Determinants of Medical Care Perception by Pregnant Poles in UK.” In Unity, diversity and culture. Proceedings from the 22nd Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology, edited by Roland-Lévy Boski C., Denoux P., Voyer P., and Gabrenya Jr W. K. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/179.

- Leaman, A. M., E. Rysdale, and R. Webber. 2006. “Use of the Emergency Department by Polish Migrant Workers.” Emergency Medicine Journal 23: 918–919.

- Levitt, Peggy, and Nina Glick Schiller. 2004. “Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society.” The International Migration Review 38: 1002–1039.

- Lindenmeyer, Antje, Sabi Redwood, Laura Griffith, Shazia Ahmed, and Jenny Phillimore. 2016. “Recent Migrants’ Perspectives on Antibiotic use and Prescribing in Primary Care: A Qualitative Study.” British Journal of General Practice 66: e802–ee09.

- Madden, Hannah, Jane Harris, Christian Blickem, Rebecca Harrison, and Hannah Timpson. 2017. ““Always Paracetamol, They Give Them Paracetamol for Everything”: A Qualitative Study Examining Eastern European Migrants’ Experiences of the UK Health Service.” BMC Health Services Research 17: 604.

- Main, Izabella. 2014. “Medical Travels of Polish Female Migrants in Europe.” Sociologicky Casopis-Czech Sociological Review 50: 897–918.

- Main, Izabella. 2016. “Biomedical practices from a patient perspective. Experiences of Polish female migrants in Barcelona, Berlin and London.” Anthropology & Medicine 23 (2): 188–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13648470.2016.1180579.

- Mainil, Tomas, Matt Commers, and Kai Michelsen. 2013. “The European Cross-Border Patient as Both Citizen and Consumer: Public Health and Health System Implications.” In Medical Tourism and Transnational Health Care, edited by David Botterill, Guido Pennings, and Tomas Mainil, 131–150. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McGhee, Derek, Sue Heath, and Paulina Trevena. 2012. “Dignity, Happiness and Being Able to Live a ‘Normal Life’in the UK–an Examination of Post-Accession Polish Migrants’ Transnational Autobiographical Fields.” Social Identities 18: 711–727.

- McGhee, Derek, Chris Moreh, and Athina Vlachantoni. 2017. “An ‘Undeliberate Determinacy’? The Changing Migration Strategies of Polish Migrants in the UK in Times of Brexit.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43: 2109–2130.

- Moreh, Chris, Derek McGhee, and Athina Vlachantoni. 2018. “EU migrants’ attitudes to UK healthcare.” ESRC Centre for Population Change Briefing Paper 41. http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/420904.

- Nartowski, R. 2018. “3.10-P8Comparing Self-Perceived Health Care Access of Poles of Varying Socioeconomic Status in London, England and Edinburgh, Scotland.” European Journal of Public Health 28: 77.

- Oltmann, Shannon. 2016. “Qualitative Interviews: A Methodological Discussion of the Interviewer and Respondent Contexts.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung 17 (2). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-17.2.2551.

- ONS. 2020. “Population of the UK by Country of Birth and Nationality: Year Ending June 2020.” Office for National Statistics - Annual Population Survey. Accessed 13 April 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/internationalmigration/bulletins/ukpopulationbycountryofbirthandnationality/latest.

- Ormond, Meghann, and Neil Lunt. 2019. “Transnational Medical Travel: Patient Mobility, Shifting Health System Entitlements and Attachments.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (20): 4179–4192.

- Osipovič, Dorota. 2013. “‘If I get ill, It’s Onto the Plane, and off to Poland’ Use of Health Care Services by Polish Migrants in London.” Central and Eastern European Migration Review 2: 98–114.

- Phillimore, Jenny, Hannah Bradby, Michi Knecht, Beatriz Padilla, and Simon Pemberton. 2019. “Bricolage as Conceptual Tool for Understanding Access to Healthcare in Superdiverse Populations.” Social Theory & Health 17: 231–252.

- Phung, Viet-Hai, Zahid Asghar, Milika Matiti, and A. Niroshan Siriwardena. 2020. “Understanding how Eastern European Migrants Use and Experience UK Health Services: A Systematic Scoping Review.” BMC Health Services Research 20: 173.

- Pollock, K. G., B. Tait, J. Tait, K. Bielecki, A. Kirolos, L. Willocks, and D. R. Gorman. 2019. “Evidence of Decreased HPV Vaccine Acceptance in Polish Communities Within Scotland.” Vaccine 37: 690–692.

- Pordié, Laurent. 2013. “Spaces of Connectivity, Shifting Temporality. Enquiries in Transnational Health.” European Journal of Transnational Studies 5: 6–26.

- Reading, Healthwatch. 2014. “How the Recent Migrant Polish Community are Accessing Healthcare Services, with a Focus on Primary and Urgent Care Services,” Reading: Healthwatch Reading. https://healthwatchreading.co.uk/sites/reading.healthwatch-wib.co.uk/files/Polish-Community-Access-to-Healthcare-Project-Report-with-responses-v1.pdf.

- Saharso, Sawitri. 2019. “Who Needs Integration? Debating a Central, yet Increasingly Contested Concept in Migration Studies.” Comparative Migration Studies 7: 1–3.

- Sime, Daniela. 2014. “‘I Think That Polish Doctors are Better’: Newly Arrived Migrant Children and Their Parents׳ Experiences and Views of Health Services in Scotland.” Health & Place 30: 86–93.

- Smoleń, Agata. 2013a. “Problemy Zdrowotne Polskich Emigrantów Poakcesyjnych. Implikacje dla Systemów Opieki Zdrowotnej.” Problemy Zarządzania 11 (41): 227–239.

- Smoleń, Agata. 2013b. “Migration-Related Stress and Risk of Suicidal Behaviour among ‘New’ Polish Immigrants in the United Kingdom,” Krakow: Młoda polska emigracja w UE jako przedmiot badań psychologicznych, socjologicznych i kulturowych EuroEmigranciPL. PL, Kraków, pp. 23–24.

- Stan, Sabina. 2015. “Transnational Healthcare Practices of Romanian Migrants in Ireland: Inequalities of Access and the Privatisation of Healthcare Services in Europe.” Social Science & Medicine 124: 346–355.

- Temple, Elizabeth Clare, and Rhonda Frances Brown. 2011. “A Comparison of Internet-Based Participant Recruitment Methods: Engaging the Hidden Population of Cannabis Users in Research.” Journal of Research Practice 7: D2–D2.

- Weishaar, Heide B. 2008. “Consequences of International Migration: A Qualitative Study on Stress among Polish Migrant Workers in Scotland.” Public Health 122: 1250–1256.

- Weishaar, Heide B. 2010. ““You Have to be Flexible” Coping among Polish Migrant Workers in Scotland.” Health & Place 16: 820–827.

- Ziarko, Michał, Helena Sęk, Michał Sieński, and Karolina Lewandowska. 2014. “Coping with Stress among Polish Immigrants.” Health Psychology Report 2: 10–18.