ABSTRACT

In response to the 2015 migration ‘crisis’, the European Union intensified the externalisation of its migration policies, in particular through the EU Trust Funds for Syria and Africa, and the Facility for Refugees in Turkey. The legal construction of these financial measures is such that in many projects, normal implementation and public procurement procedures are not applied. This creates opportunities for clientelism. A limited number of actors (Europe’s ‘clients’) has emerged to implement European policies in third countries. This way of implementing externalisation projects will first be analysed in functionalist terms and in terms of path dependency. The paper will conclude by arguing that, in addition to such analyses, this way of implementing externalisation is to be understood as (a) expanding the scope of legitimate action of European states outside their territory; and (b) setting norms for international actors such as non-European states, international organisations and corporations.

In 2014-2015, the European Union adopted three financial measures in order to cooperate with neighbouring countries in the field of migration policy. While external migration policy was thus intensified, amendments of internal policies lagged behind. As a consequence, the emphasis in European migration policy has shifted to its external elements. The adoption of the two most substantial measures was marked by high profile political summits: the November 2015 Valetta summit, bringing together the heads of state and government of the European Union and the African Union, and the March 2016 EU-Turkey summit. Under the three instruments, not only migration policy projects were funded, but also humanitarian and security related projects. The Trust Fund in response to the Syrian crisis, also called the Madad Fund, was worth a total of €2.3 billion;Footnote2 the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for stability and addressing root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa (hereafter: EUTF Africa) was worth €5 billion;Footnote3 and the Refugee Facility for TurkeyFootnote4 (later changed to Facility for Refugees in TurkeyFootnote5) €6 billion.Footnote6 This paper focuses on projects which seek to impact migration law and policy in non-EU countries, and which are funded through these measures; I will pass over projects of which the relation with migration policy is indirect (infra, para. 2). The main problematic of the article is the manner of implementation of these migration management projects – with limited or no public procurement, and relying predominantly on UN organisations and European development agencies for implementation. In other words: the article will ask the question why transregional cooperation in the field of migration management took this particular form. The overall argument of this article is that European states instrumentalise international organisations and development agencies to implement European migration policy objectives in Africa and the Middle East. These organisations become dependent on European funding, becoming Europe’s ‘clients’. This process is an example of what Lavenex and Piper (Citation2022) in their introduction to this collection call transregional power dynamics flowing ‘from beyond’ the regions from powerful states and related organisations in the moulding of regionalism; in combination with policy implementation ‘from above’ by the governments of third states without meaningful involvement of civil society.

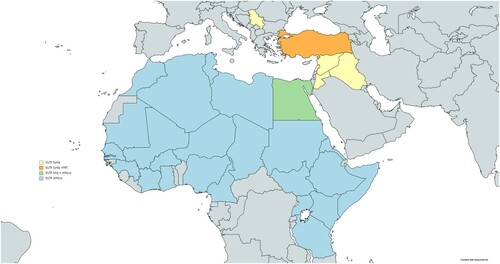

The aim of the Madad Fund and the Facility are defined in a similar, narrow manner. The Madad Fund aims to respond to the needs of Syrian refugees, their host communities and their administrations,Footnote7 while the Facility focuses exclusively on Turkey.Footnote8 The EUTF Africa has a broader purpose, namely ‘to address the crises in the regions of the Sahel and the Lake Chad, the Horn of Africa, and the North of Africa.’ It aims to support all aspects of stability and contribute to better migration management, as well as addressing the root causes of destabilisation, forced displacement and irregular migration. It will do so in particular by promoting resilience, economic and equal opportunities and security and development.Footnote9 The regional scope as defined in each instrument is summarised in the map below ().Footnote10

The two Trust Funds are financial instruments in the sense of EU Regulation 966/2012 (Carrera et al. Citation2018, 16–19). The Facility is an EU measure which is not a financial instrument itself. It is a coordination mechanism based directly on Article 210 and 214 TFEU. Both Trust Funds are emergency trust funds. While normally EU budget decisions are implemented by the Commission, the financial management of emergency trust funds can be implemented by, i.a., international organisations and their agencies; public law bodies; as well as by private entities with a public service mission.Footnote11 The Constitutive Agreement of the EUTF Africa even stipulates that delegated implementation led by Member States is the preferred manner of implementation.Footnote12 The decision establishing the Facility indicates a preference for grants,Footnote13 which is another way of sub-delegating the implementation of concrete activities to outside actors. In sum: there is a clear preference for the migration funds to be implemented not by the Commission, but by other actors.

The legal construction of these financial measures is such that usual public procurement procedures are not applied in most projects (infra, para. 1). On the basis of financial data concerning the migration management projects funded through these measures, it will be shown that a limited number of actors (namely: UN organisations and European development agencies) implement European migration policy objectives in third countries (infra, para. 2). This way of implementing externalisation projects will first be analysed in functionalist terms, following the work of Lavenex (infra, para. 3). The EU uses UN organisations and development agencies as subcontractors, and it legitimises its external migration policies through the respectability of the UN and the legitimacy of development. Then, an understanding based on path dependency will be outlined (infra, para.4). The path dependency inherent in any long-standing policy is reinforced by the subcontractors, which have institutional and financial interests in continuation of the policies they implement. Following McKeown’s poststructuralist approach (McKeown Citation2008), the paper will conclude by arguing that, in addition to functionalist analyses, the implementation of externalisation is to be understood as (a) expanding the scope of legitimate action of European states outside their territory; and (b) setting norms for international actors such as non-European states, international organisations and corporations (infra, para. 5).

1. Public procurement

Ordinarily, public projects have to be granted through public procurement, in which different parties are able to tender for the contract to be granted; public procurement is the legal term for competition in the public sector. There are a number of exceptions, in which public procurement is not required because of the urgency of the activity to be undertaken. These exceptions apply in different legal-technical contexts, the details of which are not relevant for the purpose of our analysis (for details see Spijkerboer and Steyger Citation2019). One important exception applies to crisis management aid, civil protection operations and humanitarian operations in the field of external action (Article 190(4) Regulation 966/2012). Specifically for projects in third countries, Article 190(2) of Regulation 1268/2012 contains an exception for crisis situations in third countries, which are defined as ‘situations of immediate or imminent danger threatening to escalate into armed conflict or to destabilise the country. Crisis situations shall also be understood as situations caused by natural disasters, manmade crisis such as wars and other conflicts or extraordinary circumstances having comparable effects related inter alia to climate change, environmental degradation, privation of access to energy and natural resources or extreme poverty.’ Articles 266(1)(a), 268(1)(a) and 270(1)(a) provide for another exception to be used ‘for reasons of extreme urgency brought about by events which the contracting authorities could not have foreseen and which can in no way be attributed to them’ and where for that reason the normal time limits cannot be kept. Directive 24/2014 (not applicable to the EU but instructing member States to legislate) allows for a similar exception ‘in so far as is strictly necessary where, for reasons of extreme urgency brought about by events unforeseeable by the contracting authority, the time limits for the open or restricted procedures or competitive procedures with negotiation cannot be complied with. The circumstances invoked to justify extreme urgency shall not in any event be attributable to the contracting authority.’Footnote14 If one of these general emergency provisions are applied, this means that a project can be granted to an outside actor without competition from others. What the various general emergency exceptions share is the notion that there may be situations that are so pressing that no time is to be wasted on procurement procedures. Because this undermines transparency and the efficient spending of funds, these exceptions are limited to urgent situations.

The legal instruments establishing the Madad Fund do not contain specific rules on procurement. This implies that exceptions to the normal public procurement procedures will have to be made and justified in individual project decisions on the basis of the general provisions mentioned above. It should be noted that a large part of the Madad Fund is spent on humanitarian assistance, which is exempted from public procurement (Article 190(4) Regulation 966/2012, supra).

The Decision establishing the Facility for Refugees in Turkey stipulates that implementation will be in accordance with the financial rules applicable to the Union’s budget.Footnote15 This means that the public procurement rules for financial instruments which the Facility coordinates are applicable. As a consequence, like under the Madad Fund, exceptions to public procurement are possible if they can be based on the general exceptions mentioned above. Another similarity to the Madad Fund is that a substantial part of the Facility funds concern humanitarian assistance, which is exempted from public procurement.

In contrast, the decision establishing the EU Trust Fund for Africa establishes that ‘(f)or the purpose of the implementation of the Trust Fund, the countries referred to in paragraph 4 of Article 1 are considered to be in crisis situation (…) for the duration of the Trust Fund’ (Article 3 Decision C(2015)7293). The Decision refers to Article 190 Regulation 1268/2012 (see above).Footnote16 As a consequence, all expenditure under the EUTF Africa is exempted from the obligation of public procurement procedures. However, it is not immediately evident that there is an emergency in all of the countries covered by the Fund for the all the years during which the Fund will function. The legality if this general exemption from public procurement is doubtful (Spijkerboer and Steyger Citation2019).

Empirical evidence shows that in concrete migration management projects funded through the Trust Funds, often there is no open competition. Instead, potential implementing partners bring their projects to the attention of EU delegations in the country concerned and the European Commission. These carry out a first scrutiny of potential projects. Subsequently, an informal expert group carries out an examination of the project proposals. In the background, there is an on-going negotiation between the Commission, the EU Member States, the third country involved and the potential implementing partner (Carrera et al. Citation2018, 28–29). One would expect this informal process to be more substantial if it is a well-established organisation that is in permanent contact with the European Commission and the Member States. In the words of the European Court of Auditors, the selection of projects is ‘not fully consistent and clear’ (European Court of Auditors Citation2018, 17–25).

2. Migration management clientelism

In the previous paragraph, we have seen that the legal set-up of the three financial instruments allows for discarding the usual rules on public procurement. In the EU Trust Fund for Africa, this is done by declaring a crisis for the duration of the fund in all countries covered by the fund, while for the Madad Fund and the Facility for Turkey public procurement is excluded for the bulk of the fund because it concerns humanitarian assistance (supra). Also, we have seen that in practice an ‘opaque’ (Carrera et al. Citation2018, 29, 75) procedure is followed in which lobbying by potential implementing partners plays an important role. Therefore, both formally and in practice, the scene is set for discretionary usage of EU funds. In effect, most funds are granted to a limited number of partners.

The empirical material of this paper consists of the projects adopted on the basis of the three financial measures in February 2021.Footnote17 As my focus is on the externalisation of migration policy, I have ignored projects which are predominantly about humanitarian assistance, development, and security.Footnote18 While such projects are now framed as part of external migration policy, they do not seek to influence migration and asylum policies in the target countries and are not directly relevant in our context. Together, the migration management projects (MMPs) amount to €2.8 billion. In the Excel file attached to this paper, these projects are grouped per implementing partner. The main findings are summarised in below.

Table 1. The 10 largest implementing partners of migration management projects (MMPs).

Table 2. UN run migration management projects (MMPs).

Table 3. Member State development agency run migration management projects (MMPs).

gives a summary of these projects per implementing partner. This shows that one entity, IOM, implements 17% of the migration management project funding, while GIZ (the German development agency), and UNHCR have a 14% and 11,9% share respectively. These three implementing partners have together attracted 42,9% of all migration management funding.

All UN agencies and offices together have attracted a 34% share, while all government development agencies together have attracted a 36% share ( and ).

This shows that the EU has a number of preferred partners through which it spends its migration management funding from the three sources covered in this study. Whether the preference for these partners can be explained by their superior capacity to implement these projects remains opaque. Firstly, the question of their potential superior capacity is not addressed in project documents. The (legally dubious) absence of public procurement makes it impossible to compare the preferred partners with the competition, and to establish that they are best placed to implement these projects. As indicated above, implementing partners themselves often lobby for the adoption of projects. Secondly, in some cases there is an obvious other candidate. An example of this is a project which is a continuation of an earlier project with the same aim, that was implemented by UNDP. The project document does explain why the new implementing partners (the Belgian development cooperation agency, Civipol and Communauté de Sant’Egidio) would be appropriate partners, but does not address the obvious question of why UNDP is not the appropriate implementing partner to continue its work.Footnote19

By concentrating two thirds of the funding on European development agencies and UN organisations (and 42,9% in just three of them), these partners become dependent on the EU for funding, and will be inclined to reproduce its policy preferences. The dependence of the implementing partners on EU funding results in a reciprocal exchange of goods and services based on informal links. This opaque modus of operation can hamper the efficiency of EU spending, as well as fundamental notions of democracy and the rule of law. Whether the resulting form of clientelism (Briquet Citation2021) would exist without the exceptions to public procurement is hard to say without further research. What we can observe is that the outcome (public contracts that are awarded to a limited number of actors) is one that public procurement law has been created to avoid.

3. Policy transfer

The measures under the three migration funds aim at realising a European policy goal (controlling the number of third country nationals entering the territories of European Union states) by implementing actions outside the EU. Therefore they constitute a tool of externalisation of EU policy. Such externalisation can be fruitfully analysed by relying on functionalist approaches. Lavenex has characterised this as functionalist extension: functionalist because the aim is not to control foreign territories but to influence particular policy sectors; and extension because these policies reach beyond European territory (Lavenex Citation2014). Two different mechanisms of policy transfer can easily be recognised. The first mechanism is conditionality: the threat of sanctions and, more relevant in our context, the promise of rewards in exchange for compliance with a certain policy priority. This is what happens at the general policy level. The Facility has been incorporated in the EU-Turkey agreement of March 2016, where Turkey was promised financial assistance, visa freedom and a kick-start of accession negotiations in exchange for readmitting all migrants arriving irregularly at the Greek islands after 18 March 2016.Footnote20 A kind of conditionality-lite is issue linkage, where promise and demand are not exchanged directly (as did happen in the EU-Turkey agreement) but are nevertheless closely related via an institutional structure. The EUTF Africa can be understood as a package deal in which development funding goes together with the externalisation of migration policy.Footnote21 Conditionality also occurs, but rarely, at the level of specific projects funded through the funds. One of the few examples is the budget support for Niger. Budget support amounting to €12 million in 2016 and €8 million in 2017 was granted on the condition that, among other things, the Nigerien national budget for those years is amended so that the entire amount will be spent on equipment for the Internal Security Services and justice infrastructure. Specific conditions for the 2017 support include adoption and implementation of the National Strategy on Irregular Migration.Footnote22

However, the second mechanism of policy transfer, which Lavenex (Citation2014) labels transgovernmental networking, is much more prevalent. Many projects are presented in action documents as a-political and technical, and as not imposing policies on third states but as cooperation with the authorities, reinforcement and support of existing policies. In some cases, there is a tension between the idea of support and the perspective of the receiving state as outlined in the action document. For example in one project, despite being called Support programme for the functioning of civil registries in Mali, one of the challenges identified in the action document is the limited interest of the Malian authorities in the biometric digitalised civil registry that the project seeks to implement.Footnote23 Nonetheless, approaches that suggest horizontality are prevalent: dialogues, information exchanges, as well as training and capacity-building which, though inherently vertical, at the explicit level aim at equipping third country actors to implement their own policy objectives.

International organisations (IOM, UNHCR) are very prominent in implementing transgovernmental networking projects. Organisations related to the UN implement 34% of the funds spent in migration management projects (supra). In the EU context, this can be understood in two ways. First, the EU lacks the extensive bureaucratic apparatus needed to implement these projects. International organisations function as subcontractors. Second, the fact that projects are implemented by international organisations lends the project legitimacy because of their mandate (for example the 1951 Refugee Convention in the case of UNHCR) or status (being related to the UN for IOM, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNODC). At the same, time, the financial dependence of the international organisations on European funding incentivises them to perceive their mandate in such a manner that it runs parallel with EU policies (Lavenex Citation2016; Klabbers Citation2019; Geiger and Pécoud Citation2020).

However, as we have seen, Member State development agencies also play a major part in implementing EU migration projects. For example, the development agency of the German government GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH) leads the €46 million Better Migration Management project,Footnote24 which might also have been implemented by IOM (and in which IOM and UNODC take part, for €10.387.300 and €8.929.557 respectivelyFootnote25). The subcontracting explanation of Lavenex (Citation2014) works for national development agencies as well as for international organisations. The legitimising explanation which Lavenex develops for international organisations may work in an adapted form: the aura of development can work to naturalise the issue linkage between development and the export of restrictive migration policies. The cloak of development helps legitimise the pressure of the EU on African countries to adopt and implement migration policies which are more obviously in the interest of the EU than of African states (i.a. Bisong Citation2019; Dicko Citation2018; Oette and Babiker Citation2017).

4. Path dependency

In the analysis presented so far, the externalisation of European migration policy under the three financial measures has been analysed in its own terms. The EU – so this analysis goes – seeks to make its own migration policy more effective by incentivising third states to align their policies with those of the EU. This is achieved by a mix of conditionality (including conditionality-lite, i.e. issue linkage) and transgovernmental networking. Externalisation may be more or less successful but, in this analysis, is effectively seeking to achieve its stated aims.

There are reasons not to be entirely satisfied with this analysis. First: it is evident that the externalisation policies, which have been implemented at the European level since 1990, are not very effective. Externalisation is effective in keeping people without the required documentation out of airplanes headed for Europe. However, overstaying is a more important source of undocumented migrants in Europe than irregular entry, and overstaying is not addressed by externalisation. Also, irregular entry by other means than air (boat, trucks) has increased as externalisation intensified. Furthermore, stricter migration and border policies turn out to have limited impact on mobility towards Europe, but do limit return mobility and therefore lead to a net increase of the number of migrants (including undocumented migrants) on European territory (Spijkerboer Citation2018). The limited impact may well be related to the top-down character of domestic policies which third countries implement under pressure from the EU, without ‘bottom-up’ domestic support (Lavenex and Piper, Citation2022).

In addition to these macro-level reasons not to analyse externalisation exclusively in its own terms, individual project documents display signs of despair on the side of the people drafting them.Footnote26 To give just one example: the action fiche on the Malian civil registry project mentioned earlier shows that the EU funds the development of a biometric digital civil registry for an amount of €25 million. The action fiche suggests that the Malian authorities had limited interest in a previous project with similar objectives. Footnote27 In the previous project, there has been ‘a very important gap between the financial efforts provided by the State and the partners (…) and the feeble level of political implication for an institutional reform of the system.’Footnote28 Examples of this are that a bill which is part of the process ‘is yet to be adopted since several years’, and that the Ministry of Justice has not fulfilled its supervisory role vis-à-vis the civil registries. These factors are labelled as risks. The risk that the bill will not be passed is not addressed (the relevant text repeats the problem by indicating the size of the population affected by the issue); the limited role of the Ministry of Justice is to be addressed by ‘strongly involving’ the judiciary in the process and having member of the Ministry of Justice on steering group.Footnote29 It is hard to believe that the drafters of the action fiche themselves believed that the apparent lack of interest of the Malian authorities in the effective implementation of the project can be addressed by such interventions.

Despite the above, it is quite possible to assume that European policy makers do try to effectuate policy transfer. This may be understood as a form of path dependency, which in this context takes on two specific shapes. It may not be very successful so far, but they may believe that it will eventually be successful if they try hard enough (the just-try-harder explanation). In this perspective, the lack of success of externalisation is not explained by inherent shortcomings, but by insufficient or otherwise lacking implementation. The just-try-harder attitude is evident in major European policy documents, such as the Commission’s New Pact on Migration and Asylum. Whereas the Commission speaks of ‘major shortcomings’ in existing European law and policy,Footnote30 the Commission’s proposals consist of an intensification of existing policies, including externalisation policies (De Bruycker Citation2020; García Andrade Citation2020; Guild Citation2020; Maiani Citation2020; Bendel Citation2021; Carrera Citation2021; Ineli-Ciger and Ulusoy Citation2021; Karageorgiou Citation2021; Spijkerboer Citation2021; Vedsted-Hansen Citation2021). In light of this form of path dependency in the overall policy of which the funds are part, it is plausible that it also plays a role in the implementation of the funds themselves. Alternatively, European policy makers may be aware of the limited success of policy transfer but find migration politically so important that some policy has to be implemented and they see no alternative to the ones they know to be ineffective (the got-to-do-something explanation). This seems to have been at work in the EUTF Africa. During the Valetta summit, at the height of the refugee ‘crisis’, European governments sought to take decisive action, and the clearest way of doing this was by spending lots of money. Therefore, it was important that substantial projects were adopted, and such adoption was accompanied by press releases of the European Commission. Another example is the apparent despair referred to above in the Malian project; the project is undertaken despite signs of a lack of conviction on the side of the drafters of the project fiche.

Both explanations assume a form of path dependency on the part of policy makers, where a policy is continued because it is there already. Policy makers will be encouraged in their path dependency by the implementing organisations. These are increasingly dependent on EU funding, and have an interest in continuation of the policies which they implement. As has been noted above, lobbying by implementing organisations plays an important role in the adoption of projects. Both the UN organisations and the development agencies are likely to reinforce policies and forms of implementation which allow them to remain Europe’s ‘clients’. The implementation of the externalisation of European migration policy through such actors therefore contributes to path dependency.

Although these explanations may carry some truth, they alone cannot explain either the form of, or the amount of money spent on European externalisation policies. Policy makers and researchers produce a considerable number of documents outlining policies, assessing pros and cons, and sketching long term horizons. They seem to be aware of problems inherent in their policies. Therefore the just-try-harder explanation is not convincing by itself, as this assumes that the people implementing the policies by and large have faith in the policies they implement. At the same time, if one were to believe that most or even all policy and research documents on externalisation are written by people who do not believe in what they write, one would have to believe in a well organised cynical conspiracy involving thousands of people. This is implausible, and therefore the got-to-do-something explanation cannot be sufficient explanation for externalisation either.

5. Normative power and melancholy order

Therefore, in addition to the functionalist and path dependency understandings of externalisation outlined so far, it makes sense to enquire whether there are approaches which allow us to understand externalisation even if it is accepted that its success if limited or even very limited.

Lavenex refers to Ian Manner’s notion of normative power, i.e. the ability to define what passes for normal in world politics (Lavenex Citation2014, 886). In his book Melancholy Order, the US historian Adam McKeown (without referring to Manner) uses a similar notion when he tries to understand the introduction of modern immigration law in the US and beyond after the 1880s (McKeown Citation2008). Like in our contemporary context, he faces the puzzle why at the time immigration law was popular without seeming to realise its stated aims. There was little evidence of the effectiveness of immigration law, and there were many signs that it did not lead to the desired result of controlling Chinese immigration to the US. Nonetheless, the US kept developing and refining its immigration legislation. Immigration acts modelled on the American original spread partly through direct US pressure, but more often via networks of experts, diplomats, consultants, legal writings, and scientific thought. This happened regardless of whether the states adopting US style immigration laws faced significant immigration or had welfare systems to protect. Therefore, the policy diffusion that can be observed during the period covered by McKeown’s study cannot be explained as a functional response to common economic and structural challenges. ‘Rather, the adoption of these laws must be understood as part of the spread of institutions and ideologies of population management that were necessary for international recognition as a modern nation state’ (McKeown Citation2008, 321). McKeown uses the concept of melancholia to express that immigration control may not be effective or useful, but is necessary nonetheless.

If we rely on McKeown’s historical approach in the context of contemporary European externalisation, two observations can be made. First, regardless of the effects of externalisation, Europe has successfully expanded the scope of what it can legitimately do. European policy incentivises third countries to control the movement of their own nationals (affecting their right to leave the country, and sometimes even the right to move within their own country) as well as the movement of nationals of other countries. This also happens in countries which are part of a free movement zone, in particular the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) (i.a. Hamadou Citation2018, Citation2020; Spijkerboer Citation2019). In a mainstream approach to international relations and international law, such European projects affecting the right to free movement within or across borders would be seen as interference in domestic affairs, because it is not Europe’s business how for example Niger deals with Senegalese nationals on its territory. This is the more relevant because the manner in which the EU implements its external migration policies undermines its African counterparts, ECOWAS in particular (Bisong Citation2019). This expansion of the scope of what Europe can get away with doing is supported by the legitimacy lent to this by the aura of international organisations (in particular if they are affiliated to the UN like IOM, UNHCR and UNICEF), and by the legitimacy lent by the label of development (think of involvement of development agencies such as GIZ and AFD).

Secondly, the willingness of international actors to align their policies and behaviour with European policy priorities in the field of migration is becoming required for being a legitimate subject of international law and international relations. States that allow their own nationals or those of other states to move in the direction of Europe have come to be seen as complicit in transnational organised crime (human smuggling, human trafficking) and as bearing responsibility for border deaths. This is evidenced by the de facto migration policy intervention of European countries in Libya, and the rather intrusive forms of migration management ‘support’ to states with limited control over their territory such as Niger, Mali and Chad. International organisations are also being recruited for European policy priorities. Partly this happens through financial dependence (clientelism, supra, para. 2). But in the process, UN organisations such as IOM, UNODC and UNHCR now also voice the idea that preventing particular forms of human mobility is imperative because of human rights (slave camps in Libya, death at sea) and transnational crime (human smuggling and trafficking).Footnote31 UN organisations have reinterpreted their institutional mandate in such a manner that it aligns with European policy (Lavenex Citation2016; Klabbers Citation2019; Geiger and Pécoud Citation2020). The same has happened in the case of carrier sanctions for international transportation companies, which are fined and eventually are denied landing rights if they fail to comply with legislation that makes them into de facto enforcement agents of migration policies of the global North.

In sum, the externalisation of European migration policy cannot, or cannot only be understood by its direct usefulness, but has to be understood also as part of a global political project. By using its ‘clients’ to implement externalisation, Europe has succeeded in adding population management to the policy fields where the global North can legitimately intervene in the policies and practices of the global South – earlier examples being military (humanitarian) intervention, good governance (including human rights), and economic policy (structural adjustment) (Anghie Citation2005, 247–272). Secondly, the EU has succeeded in setting a standard for international behaviour of states from the global South, of international organisations, and of international commercial actors. Although other countries of the global North are working on the same or similar projects (US interdictions, Australia’s offshoring), the avant garde role of the European Union in the field of the externalisation of migration law and policy positions it as a world leader. This avant garde role can be related to the success with which EU policy makers captured UN organisations as well as development agencies by having them implement its externalisation policies. One may point to the continuity with European management of populations in Africa and the Middle East during the colonial period (Hansen and Jonson Citation2016), or alternatively interpret externalisation as a form of colonial European nostalgia for the time when it still was in charge of these populations (McQueen Citation2011; Billings Citation2011). The potential parallel with the League of Nations era, in which Europe instrumentalised the mandate system as a form of colonial domination (Anghie Citation2005, 115–195), is an issue that could be further explored.

6. Conclusion

Although the crisis in dealing with the influx of refugees and asylum seekers was primarily related to internal factors (Heijer, Rijpma, and Spijkerboer Citation2016; Thym Citation2016), the European Union has responded to ‘2015’ mostly by intensifying its external migration policies. This is a form of transregional policy transfer, with Europe on the sending end and Africa, the Middle East and Turkey on the receiving end. The three financial measures which are at the core of this article are a major component of this. A notable element of these financial measures is the side-lining of the usual implementation and public procurement procedures. The lack of competition allows the EU to rely on a limited number of trusted partners to implement its migration management projects, which are the practical, tangible form of externalised migration policy. Implementation is dominated by a limited number of UN organisations and European development agencies who are dependent on EU funding and who in return interpret their mandate so as to run parallel with European policy objectives – Europe’s ‘clients’. In this manner, European migration policy makers have succeeded in ‘uploading’ their agenda to the UN level (Lavenex Citation2016; Spijkerboer Citation2017; Klabbers Citation2019; Geiger and Pécoud Citation2020) (which then ‘downloads’ it elsewhere), and they also instrumentalise European development agencies to implement migration policy transfer. This form of implementation can be analysed in functionalist terms as subcontracting, and as a way of adding legitimacy to externalisation policies. In addition, it can be analysed in terms of path dependency. This paper has argued that these explanations are insufficient, and proposes to add another perspective. The implementation modalities of European external migration policy have, on the one hand, helped to expand the field of legitimate action of European states. Population management in the Middle East and Africa is, once again, a legitimate subject of European policy. In addition, it has allowed Europe to set norms for international actors who are considered to impact migration (third states, international organisations, and transport companies). Because this approach does not align with mobility-oriented priorities of economic and civil society actors in the countries concerned, it results in a double ‘from above’ process (Lavenex and Piper, Introduction): firstly the EU incentivises third countries to implement European policy objectives, and a secondly third states impose policies which often lack domestic social and political legitimacy. This takes place in the context of unequal power relations, which are obscured by the multilateral veneer of the UN and the Third World-ist pretensions of development. In this manner, even if external migration policy may not be successful in its own terms, it furthers the EU’s global political project.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (132.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Professor of Migration Law, Amsterdam Centre for Migration and Refugee Law, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. The research presented in this paper has been made possible by the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation’s support for my position as Raoul Wallenberg Visiting Professor at Lund University, 2017-2020. I am grateful to the participants of the workshop ‘Advancing international migration governance: Global Compacts and Regional Approaches’ (University of Geneva, 21–23 June 2017), and in particular to Sandra Lavenex, for their feedback on earlier versions of this paper.

2 Decision C(2014) 9615 final. For financial details comp. Implementing Decision C(2014) 9614 final; Implementing Decision C(2015) 7695 final of 13 November 2015; Implementing Decision C(2016) 7898 final of 8 December 2016; Implementing Decision C(2017) 4290 final of 26 June 2017; Implementing Decision C(2017) 8187 final of 8 December 2017; Implementing Decision C(2018) 7776 final of 27 November 2018. Financial state of play February 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfund-syria-region/content/state-play_en, accessed 23 February 2021.

3 Decision C(2015)7293 final of 20 October 2015. Financial state of play February 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/content/trust-fund-financials_en, accessed 22 February 2021.

4 Commission Decision C(2015) 9500 final, 24 November 2015.

5 Commission Decision 2016/C 60/03 of 10 February 2016.

6 Article 4 Decision C(2015) 9500. Financial state of play February 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/news_corner/migration_en, accessed 23 February 2021.

7 Article 1(2) Decision C(2014) 9615. Recital 12 states that assistance inside Syria ‘should be considered’.

8 Decision C(2015) 9500, Article 1.

9 Article 1(2) Commission Decision C(2015) 7293 final, 20 October 2015.

10 For the Madad Fund: Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Turkey, Iraq, Egypt, or any other country in wider the region affected by the Syrian crisis, including the Western Balkans (Article 1(5) Decision C(2014) 9615 as amended by Decision C(2015) 9691 final of 21 December 2015); for EUTF Africa: Algeria, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Niger, Nigeria Senegal, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia and Uganda (Article 1(4) Decision C(2015)7293 and Decision C(2017)772 final); for the Facility: Turkey (Article 1, Decision C(2015) 9500).

11 Article 187(2) jo. Article 58(1)(c)(ii), (v) and (vi) Regulation 966/2012. Comp. Carrera et al. (Citation2018), 21.

12 Article 10 of the Agreement Establishing the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Stability and Addressing Root Causes of Irregular Migration and Displaced Persons in Africa, and its Internal Rules. Comp. Carrera et al. Citation2018, 31, 33.

13 Article 3(3) Decision C(2015) 9500.

14 Article 32(2)(c) Directive 24/2014.

15 Article 6(3) Decision C(2015) 9500.

16 Actually, the text refers to Article 90 instead of 190. The typo was identified by searching the pdf version of the Regulation for the word ‘crisis’.

17 An overview of all projects is to be found in the Excel file annexed to this paper. The sources are mentioned in the file; I have relied on contract status overviews where available, as these give the most detailed insight in which organisations got the contracts. Where these were not available, action fiches have been used, as well as the project lists for the EUTF Africa regions (Sahel & Lake Chad, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/sahel-lake-chad_en, Horn of Africa, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/horn-africa_en, North of Africa, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/north-africa_en, and the cross-window projects, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/north-africa_en), all accessed 22 February 2021.

18 Comp. the typology used in Kervin and Shilhav (Citation2017). I have considered as migration related projects those labelled by the EU as such on its website on the EU Trust Fund for Africa (https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/thematic/improved-migration-management, accessed 22 February 2021), and those that are related to migration policy on the basis of a substantive analysis of all information about the projects.

19 Programme d'appui au fonctionnement de l'état civil au Mali: appui à la mise en place d’un système d’information sécurisé, T05-EUTF-SAH-ML-08, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/sahel-lake-chad/mali/programme-dappui-au-fonctionnement-de-letat-civil-au-mali-appui-la-mise_en, accessed 24 February 2021.

20 EU-Turkey statement, 18 March 2016, Press release 144/16 of the Council of the EU, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/pdf, accessed 24 February 2021.

21 This was the perspective of Dutch civil servants working on the externalisation of European migration policy. They acknowledge the limited interest West-African states have in obstructing migration towards Europe because it limits remittances, undermines the smuggling economy without replacing it with other income, and has a potential negative impact on regional migration. But they emphasised that the income generated through EUTF development projects dwarfs the losses. Telephone interview with Foreign Office official 21 September 2017; telephone interview with Ministry of Security and Justice official 20 October 2017.

22 Contrat relatif à la Reconstruction de l'Etat au Niger en complément du SBC II en préparation / Appui à la Justice, Sécurité et à la Gestion des Frontières au Niger, T05-EUTF-SAH-NE-06, p. 23, https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/sites/euetfa/files/t05-eutf-sah-ne-06.pdf, accessed 23 February 2021. The document specifies the equipment to be acquired through the budget support, being ‘security, logistics and mobility, IT, solar, communication, technical and scientific equipment and supplies, as well as other equipment of the same type, non-lethal.’

23 Project document, supra fn 19.

24 See the EU website on this project https://eutf.akvoapp.org/en/project/5493/, accessed 24 February 2021, and the GIZ website https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/40602.html, accessed 24 February 2021.

25 Contract status Horn of Africa December 2017, https://ec.europa.eu/europeaid/sites/devco/files/december_-2017-hoa-contract_status_overview-update-regional_en.pdf, accessed 19 February 2018 and since removed from the EU’s website.

26 The notion of despair I borrow from Berman Citation1993.

27 Project document, supra fn 19, p. 4. In fact, this was a $56 million project implemented by UNDP, see UNDP Mali: Projet d’appui au processus electoral au Mali, http://www.ml.undp.org/content/mali/fr/home/operations/projects/democratic_governance/PAPEM.html, accessed 9 April 2019 and since removed from UNDP’s website.

28 Action fiche, supra fn 22, p. 4-5, author’s translation from the French original.

29 Ibid. p. 13.

30 Communication from the Commission on a New Pact on Migration and Asylum, COM(2020) 609 final, Brussels, 23.9.2020, para. 1.

31 Examples are the International Organization for Migration’s work on ‘Counter-Migrant Smuggling’ as part of its Immigration and Border Management Division, see https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/our_work/DMM/IBM/2020/en/counter-migrant-smuggling.pdf, accessed 18 June 2021; the UNODC’s involvement in implementing the UN Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants in a manner that restricts mobility, see https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/human-trafficking/Webstories2021/protection-of-smuggled-migrants.html, accessed 18 June 2021; comp. Spijkerboer Citation2017

References

- Anghie, Anthony. 2005. Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bendel, Petra. 2021. “Fresh Start Or False Start? The New Pact on Migration and Asylum.” Carrera and Geddes 2021: 251–261.

- Berman, Nathaniel. 1993. “‘But the Alternative Is Despair’. European Nationalism and Mondernist Renewal of Internaional Law.” Harvard Law Review 106 (8): 1792–1903.

- Billings, Peter. 2011. “Judicial Exceptionalism in Australia. Law, Nostalgia and the Exclusion of ‘Others’.” Griffith Law Review 20 (2): 271–309.

- Bisong, Amanda. 2019. “Trans-regional Institutional co-Operation as Multilevel Governance: ECOWAS Migration Policy and the EU.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (8): 1294–1309.

- Briquet, Jean-Louis. 2021. “Clientelism”, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/clientelism, accessed 23 February 2021.

- Carrera, Sergio. 2021. “, Whose Pact? The Cognitive Dimensions of the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum.” Carrera and Geddes 2021: 1–24.

- Carrera, Sergio, Leonhard den Hertog, J. Núñez Ferrer, Roberto Musmeci, Marta Pilati, and L. Vosyliūtė. 2018. Oversight and Management of the EU Trust Funds. Democratic Accountability Challenges and Promising Practices. Brussels: European Parliament.

- De Bruycker, Philippe. 2020. “The New Pact on Migration and Asylum: What it is not and what it could have been”, EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy, eumigrationlawblog.eu, accessed 18 June 2021.

- Dicko, Bréma Ely. 2018. La gouvernance de la migration malienne à l’épreuve des injonctons contradictoires de l’UE, FES Mali Policy Paper, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

- European Court of Auditors. 2018. European Union Trust Fund for Africa: Flexible but Lacking Focus. Luxembourg: European Court of Auditors.

- García Andrade, Paula. 2020. “EU cooperation on migration with partner countries within the New Pact: new instruments for a new paradigm?”, EU Immigration and Asylum Law and Policy, eumigrationlawblog.eu, accessed 18 June 2021.

- Geiger, Martin, and Antoine Pécoud. 2020. The International Organization for Migration. The New ‘UN Migration Agency’ in Critical Perspective. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Guild, Elspeth. 2020. “Negotiating with Third Countries under the New Pact: Carrots and Sticks?”, eumigrationlawblog.eu, accessed 18 June 2021.

- Hamadou, Abdoulaye. 2018. “La Gestion des Flux Migratoires au Niger Entre Engagements et Contraintes.” Revue des Droits de L’homme 14.

- Hamadou, Abdoulaye. 2020. “Free Movement of Persons in West Africa Under the Strain of COVID-19.” AJIL Unbound 114: 337–341.

- Hansen, Peo, and Jon Jonson. 2016. “EU Migration Policy Toward Africa. Demographic Logics and Colonial Legacies.” In Postcolonial Transitions in Europe: Contexts, Practices and Politics, edited by Sandra Ponzanesi, and Gianmaria Colpani, 39–48. Londen/New York: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Heijer, Maarten den, Jorrit Rijpma, and Thomas Spijkerboer. 2016. “Coercion, Prohibition and Great Expectations: The Continuing Failure of the Common European Asylum System.” Common Market Law Review 53 (3): 607–642.

- Ineli-Ciger, Meltem, and Orçun Ulusoy. 2021. “A Short Sighted and One Side Deal: Why The EU-Turkey Statement Should Never Serve As a Blueprint.”, Carrera and Geddes 2021: 111–124.

- Karageorgiou, Eleni. 2021. “The Impact of the New EU Pact on Europe’s External Borders: The Case of Greece.” Carrera and Geddes 2021: 47–60.

- Kervin, Elise, and Raphael Shilhav. 2017. An Emergency for Whom? The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – Migratory Routes and Development aid in Africa. Oxfam: Oxfam briefing note.

- Klabbers, Jan. 2019. “Notes on the Ideology of International Organizations law: The International Organization for Migration, State-Making, and the Market for Migration.” Leiden Journal of International Law 32 (3): 383–400.

- Lavenex, Sandra. 2014. “The Power of Functionalist Extension: how EU Rules Travel.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (6): 885–903.

- Lavenex, Sandra. 2016. “Multilevelling EU External Governance: the Role of International Organizations in the Diffusion of EU Migration Policies.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (4): 554–570.

- Lavenex, Sandra, and Nicola Piper. 2022. “Regions and Global Migration Governance: Perspectives ‘From Above', ‘From Below' and ‘From Beyond’.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (12): 2837–2854. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2021.1972564.

- Maiani, Fransesco. 2020. “A ‘Fresh Start’ or One More Clunker? Dublin and Solidarity in the New Pact”, eumigrationlawblog.eu, accessed 18 June 2021.

- McKeown, Adam M. 2008. Melancholy Order. Asian Migration and the Globalization of Borders. New York: Columbia University Press.

- McQueen, Rob. 2011. “The Remembrance of Things Past and Present.” Griffith Law Review 20 (2): 247–251.

- Oette, Lutz, and Mohamed Abdelsalam Babiker. 2017. “Migration Control à la Khartoum: EU External Engagement and Human Rights Protection in the Horn of Africa.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 36 (4): 64–89.

- Spijkerboer, Thomas. 2017. “Wasted Lives. Borders and the Right to Life of People Crossing Them.” Nordic Journal of International Law 86 (1): 1–29.

- Spijkerboer, Thomas. 2018. “The Global Mobility Infastructure: Reconceptualising the Externalisation of Migration Control.” European Journal of Migration and Law 20 (4): 452–469.

- Spijkerboer, Thomas. 2019. “The New Borders of Empire. European Migration Policy and Domestic Passenger Transport in Niger.” In Caught in Between Borders: Citizens, Migrants and Humans. Liber Amicorum in Honour of Prof. dr. Elspeth Guild, edited by Paul Minderhoud, Sandra Mantu, and Karin Zwaan, 49–57. Tilburg: Wolf Legal Publishers.

- Spijkerboer, Thomas. 2021. “I Wish There Was a Treaty We Could Sign”, in Carrera and Geddes, 61-60.

- Spijkerboer, Thomas, and Elies Steyger. 2019. “European Migration Funds and Public Procurement Law.” European Papers 4 (2): 493–521.

- Thym, Daniel. 2016. “The “Refugee Crisis” as a Challenge of Legal Design and Institutional Legitimacy.” Common Market Law Review 53 (6): 1545–1574.

- Vedsted-Hansen, Jens. 2021. “Admissibility, Border Procedures and Safe Country Notions.” Carrera and Geddes 2021: 170–179.