ABSTRACT

This study examined the voting practices of Filipina marriage migrants in South Korea. Drawing on in-depth interviews with 66 women, we examine marriage migrant women’s voting through the lens of cultural and performative citizenship. We focus on the gendered and ethnicized integration of marriage migrants into Korean families and in the larger society and how their marginalised social position shapes the women’s voting practices. We identified three voting patterns – dependent, independent, and transitioned – that vary in their degrees of cultural and performative citizenship. We also unpack the characteristics or factors associated with each voting pattern that facilitated marriage migrants’ ability to engage in performative citizenship; that is, to contest their marginalised status and exercise greater autonomy in their candidate choices. Our findings illustrate how viewing immigrant voting through the perspectives of cultural and performative citizenship provides nuanced insights about the meaning and practice of voting beyond its intrinsic function of political representation.

Introduction

Nicole migrated to South Korea (henceforth Korea) from the Philippines as an industrial trainee in 1997 and a few years later married a Korean colleague at the factory where she worked. She was 49 years old at the time of the study, and, since acquiring Korean citizenship in 2000, she had never questioned her husband’s voting decisions.

It’s my option and decision to follow my husband’s principles in selecting a candidate. Yes, I am a Korean citizen now, but I was not born as a Korean. But my husband will always be an authentic citizen of Korea. He knows better than me about his fellow Koreans [emphasis added].

In the past two decades, marriage migration has become a major source of immigration in East Asia (Jones and Shen Citation2008; Kim and Oh Citation2011; Jones Citation2012). As foreign spouses, marriage migrants undergo an expedited naturalisation process in countries such as Korea and Taiwan (Hsia Citation2009; Kim Citation2013). In Korea, access to naturalisation has meant that many marriage migrants can participate in the political life of their host countries within a relatively short period of time, including voting in local and federal elections. Indeed, 62% of naturalised marriage migrants report voting (MOGEF Citation2013).

Despite significant developments in the literature regarding increased marriage migration in East Asia, there is limited knowledge about marriage migrant women’s political participation and the social processes that influence their political activities in receiving countries. In the current study, we address this knowledge gap by examining the voting views and practices of Filipina marriage migrants in Korea. Drawing on in-depth interviews with 66 Filipina marriage migrants, we explore women’s voting through the lens of cultural and performative citizenship. By tracing how women practice voting in their everyday lives and how they experience changes over time, this study contributes to a more nuanced understanding of immigrant voting by showing how marriage migrant women’s political citizenship is intertwined with, and constrained by, host country cultural and gender norms.

Marriage migration and women’s voting in Korea

Since the early 1990s, the Korean government has promoted female marriage migration to resolve the ‘bride famine’ dilemma in rural Korea (Lee Citation2008). Local governments and agricultural associations arranged meetings between bachelor farmers and ethnic Korean women from China, seeking a solution to declines in the reproduction rate and caregiving functions of rural families. Since the early 2000s, as the commercial marriage industry evolved to encompass free enterprises that do not require government-issued licenses, cross-border marriages proliferated and expanded beyond rural areas. At the same time, the sending countries of female marriage migrants expanded beyond China. Currently, more than 231,000 marriage migrant women live in Korea. Women from China make up the largest share (39%) of the marriage migrant population, followed by women from Vietnam (33%), the Philippines (9%), and Japan (5%). With 48% of marriage migrant women having acquired citizenship and 14% securing permanent resident status, more than half of female marriage migrants in Korea are eligible to vote in national and/or local elections (MOGEF Citation2019).Footnote1

During the past decade, with the increasing visibility of marriage migrant women and the burgeoning discourse of multiculturalism (Kim Citation2012), these women’s political participation, especially electoral participation, has garnered wide public attention. For instance, in election periods, marriage migrant women have often been featured as an emerging group of new voters in the news media since the late 2000s (Ryu Citation2006). Regional branches of Korea’s National Election Commission, an independent constitutional body that manages elections, holds educational programmes and mock elections for marriage migrants during election campaigns. Marriage migrants have also been the target of political parties’ active strategies to garner their votes. For example, major political parties created committees that focus on issues specific to marriage migrants and their families. They also nominated marriage migrants as candidates for various local political offices. The election of a naturalised Filipina marriage migrant to the national Congress in 2012 brought further attention to the potential of female marriage migrants as political subjects representing damunhwa —a Korean translation of ‘multicultural,’ which colloquially refers to families with marriage migrants.

Only a handful of studies have examined marriage migrant women’s voting experience. Using survey data, these studies have identified the importance of Korean language ability, length of stay, the use of the Internet, and community engagement (Ariun Citation2011; Im and Nam Citation2014; Lee and Lee Citation2013) for marriage migrants’ political participation, including voting. In particular, Im and Nam (Citation2014) showed that those who were divorced or separated and employed were more likely to vote, join a political party, or participate in civic organisations. The authors did not further explore why divorce/separation or employment facilitated marriage migrants’ political activities, however. Also not explored in these prior studies is how the marriage migrants voted and why.

Studies on native-born Korean women’s electoral participation have shown that the voting practices of female constituents have undergone significant changes over time. Because politics has been traditionally considered a male domain, up until the 1990s voting rates were lower among female constituents than among their male counterparts. It was also not uncommon for female voters to follow their male family members’ choice of candidates when casting votes (Kim, Kim, and Kim Citation2001). During the new millennium, however, voting rates among women in their late 20s and 30s who actively participate in the labour market rose sharply compared with their male counterparts. At the same time, a declining trend of women’s reliance on male family members’ voting preferences was observed (Kim, Kim, and Kim Citation2001; Koo, Yoon, and Choi Citation2015; Lee Citation2013). This is not to say that native-born Korean women’s emerging political autonomy is without its challenges. A recent, widely reported incident where a husband in his 80s tore up his wife’s ballot because she did not vote for the same candidate as he did (Kim Citation2017), shows that native-born Korean women may still be constrained by gendered expectations when it comes to their voting practices.

Situating the voting participation of marriage migrant women

Previous studies on immigrant voting, which focused mainly on the experiences of immigrants in Western democracies, has largely focused on voting as a political citizenship practice. As both the right and duty of a citizen in democracies, scholars have identified voting as the key indicator of immigrants’ adaptation to the host country’s political system (Bloemraad Citation2006; Bueker Citation2005; Jones-Correa Citation2001; Voicu and Comşa Citation2014). They primarily explain voting as the result of immigrants’ political socialisation about the norms and behaviours of politics in the host country (Bloemraad Citation2006; Jones-Correa Citation2001; Ramakrishnan and Espenshade Citation2001; Voicu and Comşa Citation2014; White et al. Citation2008). For example, Bloemraad (Citation2006) explicates the social process of immigrant voting in the US and Canada, where immigrants learn about the host country’s political system and get mobilised to vote, primarily, at least initially, by co-ethnic community leaders and organisations. These studies of political socialisation outline the general mechanism of voting for economic immigrants and refugees.

The voting practices of female marriage migrants may be quite different from other immigrants (e.g. economic, education, and family class immigrants), however. First, marriage migrants have a fast-tracked path to naturalisation. As such, the socialisation process may be truncated. Second, marriage migrants are embedded within native-born Korean families, as opposed to co-ethnic communities. The Korean family, as an institution, has its own norms, much of it rooted in Confucian ideology, that structure the relations among its members, including marriage migrants (Kim Citation2013). Moreover, female marriage migrants are often located away from co-ethnic community settings that are generally assumed for other immigrants. Consequently, the political socialisation process may be less influenced by co-ethnic community members.

Studies have shown that marriage migrant women in East Asia gain access to both legal and substantive citizenship primarily through their roles as biological and cultural reproducers (Kim Citation2013; Kim and Vang Citation2020; Lee Citation2012; Wang and Bélanger Citation2008). In other words, their worth as a citizen is often contingent upon their ability to reproduce the next generation of Korean children. This path to ‘ethnicized maternal’ citizenship entails processes of cultural assimilation and ethnic othering (Kim Citation2013, 456). As newly married daughters-in-law, marriage migrant women are placed at the bottom of the family hierarchy under Confucian patriarchy (Cho Citation1998; Kandiyoti Citation1988). Nationalistic discourse regarding the superiority of Korea over marriage migrant women’s countries of origin further relegate the women to inferior ‘others’ (Freeman Citation2005; Lee Citation2012; Wang and Bélanger Citation2008; Bélanger, Lee, and Wang Citation2010). Marriage migrants from Southeast Asian countries, including Filipinas, are often racialized as ‘dark-skinned foreigners’ from underdeveloped countries and stereotyped as ‘lazy or unrefined’ in familial or communal settings in Korea (Kim Citation2018, 143).

Theoretical frameworks

Ethnicized maternal citizenship has implications for the kind of political socialisation that occurs for female marriage migrants in Korea. Specifically, the process of acquiring knowledge of the receiving country’s political system, the act of voting, and the decision of who to vote for are filtered through the power dynamics and relations of the Korean family that is different from those of co-ethnic members or ethnic organisations. As such, different theoretical frameworks are needed to situate and interpret the voting behaviours of female marriage migrants. In this section, we briefly outline such an alternative framework.

Building on Foucault’s concept of subjectification, Ong (Citation1996) conceptualises cultural citizenship as the ‘dual process of self-making and being made within webs of power’ (738, emphasis added). Within this framework, the focus is on the interactions where immigrants are subject to various disciplinary regimes by state agencies and civil society, which attempt to instil proper normative behaviour and identity for migrants; thereby setting the criteria of their belonging in the host society (Ong Citation1999; Citation2003). For marriage migrant women, the family is a key institution wherein the cultural practices and beliefs that delineate the criteria of their belonging in their immediate Korean family and larger host society are communicated, negotiated, and practiced (Kim Citation2007; Kim and Vang Citation2020). From a cultural citizenship standpoint, voting is not a neutral act but one that is potentially fraught with differential power relations along gender and ethnic lines.

Although the cultural citizenship framework acknowledges the process of ‘self-making’ in which immigrants pursue their own goals and needs within the cultural repertoires of the host country by appropriating and deflecting them (Ong Citation1999; Citation2003), it often falls short of explaining the transformative and creative endeavour that migrants engage to challenge their marginalised status. In his original formulation, Foucault acknowledges that the process of subjectification involves multiple subject-positions and discourses, which makes it open to resistance and struggles (Foucault Citation1980; Citation1982). That is, the existence of local knowledge or situated knowledge, in the language of feminist standpoint theory (Haraway Citation1988), enables counter-hegemonic practices of those who are marginalised. In terms of voting behaviour, this transformative possibility is better captured by the concept of performative citizenship.

Performative citizenship entails the political and social struggles of citizens and non-citizens who enact citizenship, regardless of their ascribed non-citizen or second class citizen status, by claiming and performing rights and duties as citizens (Isin Citation2017, 501). According to Isin (Citation2017, 501), ‘how people perform citizenship plays an important role in contesting and constructing citizenship and attaching meanings to rights [emphasis added]’. As such, performative citizenship can be defined as the endeavours of marginalised subjects to assert themselves as equal citizens based on their own situated knowledge. These efforts vary in their transformative ability to contest marginalisation.

The concept of performative citizenship has mainly been discussed in studies of grassroots struggles by non-citizens who act like citizens regardless of their formal status (McNevin Citation2009; McThomas Citation2016; Meyer and Fine Citation2017). Nonetheless, the concept may be useful in understanding the voting acts of new citizens whose belonging is still ‘in the mode of becoming’ (Butler Citation2004, 217). Specifically, performative citizenship among Filipina marriage migrants would include the actions that women undertake to contest their gendered and ethnicized status within the family. By either openly or surreptitiously voting for their preferred candidates, as opposed to voting for the candidates chosen by their husbands and/or in-laws, marriage migrants are not merely performing a privilege or duty of Korean citizenship, they are also challenging their marginal status in Korean society more generally.

Methods

This study draws on in-depth interviews with 66 Filipina marriage migrants residing in both urban and rural areas of Korea who were eligible to vote, either as citizens (n = 64) or as permanent residents (n = 2). The interviews with Filipina marriage migrants were mostly conducted over a period of seven months in 2014. Between April and June of 2018, follow-up interviews were conducted with 20 of the marriage migrants with whom we initially interviewed in 2014. Because only about a third of the initial interviewees were available for the follow-up interviews, three new Filipina marriage migrants were recruited into the study to partially make-up for the attrition. We chose to recruit Filipinas because of the presence of the Philippine-born congresswoman at the time of fieldwork. We expected that the wide media attention on her congressional seat, as mentioned earlier, might raise political awareness among the Filipinas and influence their voting behaviours. All interviews were conducted in the Seoul Capital Area and in cities and rural areas in the southern part of Korea. Local elections took place in June of 2014 and 2018, which heightened the study participants’ awareness about elections and provided a natural springboard for exploring the women’s views and voting practices during the interviews.

The participants were recruited through Filipina voluntary organisations and subsequent snowball sampling. From these initial contacts, snowball sampling was used to select additional interviewees. The additional interviews were selected to incorporate as much variation as possible in terms of their time since arrival, marital status, and family living arrangements (e.g. nuclear family only or co-habitation with in-laws).

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, in either English or Korean. The interview transcripts were coded using the qualitative software programme NVivo (Bazeley and Jackson Citation2013). Using the coding process suggested by Strauss and Corbin (Citation1998) as a guide, the first stage involved paragraph-by-paragraph open coding of the transcripts. Recurrent phenomena were then identified and open codes were categorised into higher-order codes, focusing on women’s voting experience. The three voting patterns – dependent, independent, and transitioned – emerged in the process. This process was followed by axial coding, in which higher-order codes were linked to ultimately create a storyline about how these women experienced voting and the factors that shaped each voting pattern.

shows the sociodemographic characteristics and voting behaviour of the participants. The average age was 39.7 (range: 25–63) years. Marriage migrants had been in Korea for 12.6 (range: 5–23) years on average at the time of the interviews. Approximately one in four participants had experienced divorce and/or separation. Among those remaining in their marriages, approximately one in four were living with their parents-in-law. In terms of educational attainment, the majority (65%) of the women had earned at least an associate degree in the Philippines. Only three women had no children with their Korean husbands while the rest had two children on average. Almost half of the women were working as part-time English teachers or interpreters, while others were engaged in farming or small businesses (see ).

Table 1. Characteristics of Filipina marriage migrants.

Table 2. Distribution of Filipina marriage migrants’ occupations.

Results

In the 2009 National Survey of Multicultural Families, 56.7% of female marriage migrants who were naturalised citizens reported having voted in Korea. Filipina respondents had the highest rate of voting (66.7%) among marriage migrant women (KIHSA Citation2010). In comparison, the overwhelming majority (95%) of the Filipina marriage migrants in our study reported voting in a local or national election. shows the voting patterns of the 63 marriage migrants who voted in a recent local or national election. These voting patterns, which we labelled as dependent, independent and transitioned represent varying degrees of cultural and performative citizenship.

Table 3. Voting patterns of Filipina marriage migrants who voted in elections between the 2012∼2018 elections.

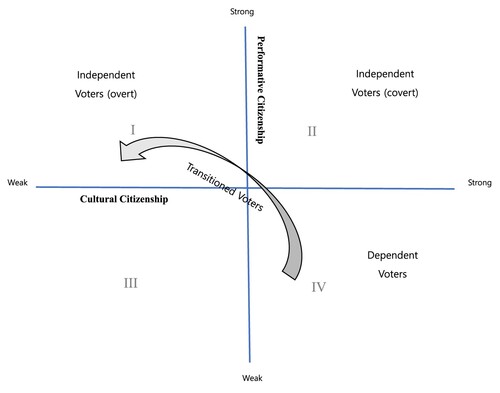

Although a ballot is cast individually in the end, voting—and immigrant voting in particular—is also a social process that is influenced by those around the voter (Bloemraad Citation2006; Gidengil and Stolle Citation2009; Rolfe Citation2012). Consequently, for marriage migrant women who come directly to stay with native-Korean families, the family becomes their closest resource and network, influencing their political views and voting behaviour. We found that this influence of the marital family comes with gendered and ethnicized norms and expectations of conformity. To make sense of the degree of ‘webs of power’ within the family (i.e. cultural citizenship) affecting marriage migrants’ voting practices and the extent to which migrant women are able to contest these influential forces (i.e. performative citizenship), we mapped the three voting patterns onto intersecting cultural and performative citizenship dimensions that vary in terms of strength (see ).

Approximately forty-one percent of the women followed the voting choices of their husbands and/or parents-in-law (dependent voters). Dependent voters are depicted in quadrant IV in because their voting choices are constrained by the preferences of their husbands and in-laws (strong cultural citizenship) and the act of voting is not perceived by the women as a process of claims-making nor does it serve to challenge the women’s marginalised status within the family (weak performative citizenship). In contrast, independent voters (39.7%) were marriage migrants who voted for their own candidates from the get-go rather than those selected by their husbands and/or in-laws (quadrants I and II). Dynamics of cultural citizenship varied across the weak/strong spectrum for these women depending on the degree of gendered and ethnicized expectations that husbands and/or in-laws had and their attempts to influence or control the marriage migrants’ candidate choices. Despite the varying degrees of cultural citizenship among independent voters, ultimately their high level of autonomy in choosing the candidates signified a strong degree of performative citizenship. Finally, 12 of the marriage migrants initially conformed with the voting choices of their Korean family members but voted for candidates that were not endorsed by their spouses and/or in-laws in subsequent elections (transitioned voters). These women are depicted as moving from quadrant IV to I because the ‘webs of power’ within the family maintain its influence, especially at the beginning. But as a result of various factors, explained below, these women were nonetheless able to lessen the influences of the family over time and exercise greater autonomy in their selection of candidates. This transition to having greater autonomy in voting can be seen as successful instances of low status contestation within the Korean family (i.e. strong performative citizenship).

In the following sections, we further describe the three different types of voting patterns and unpack the factors that influenced these patterns. Key distinguishing characteristics of the three voting patterns are highlighted in . Excerpts from selected interviewees which illuminate the key characteristics identified in are shown.

Table 4. Key characteristics of dependent, independent, and transitioned voters.

Dependent voters: voting as a family affair

For participants who followed the decisions of their husbands and in-laws, dependent voting, at least initially, makes sense because of the perception of their own lack of knowledge about Korea’s political structure, history, and candidates. Studies on voting behaviour have shown that employing cognitive shortcuts, such as following the endorsements of trusted others to make up for political ignorance, is a common practice among voters in general (Lau and Redlawsk Citation2001, 953). Indeed, the participants whose voting choices are consistent with that of their husbands and/or parents-in-laws seemed to be using such cognitive shortcuts. As mentioned by Imee, a 46-year-old Filipina who had been in a leadership role in a religious voluntary association of Filipina marriage migrants, ‘Most of us really vote. We practice the privilege of voting, and, mostly, who do we vote for? Usually we depend on the husband. “Honey, who do you like?” Like that. Whatever our husbands tell us, we vote for them.’

Imee’s explanation echoed that of most dependent voters, who reported that they participated in voting because they think of it as ‘a privilege and duty of a citizen.’ Most of them also expressed positive perceptions toward politics in Korea, which they often contrasted with political corruption in the Philippines. However, they were concerned about their ability to choose the right candidate. Certainly, a lack of information and the language barrier may make it difficult for these new citizens to choose candidates on their own. Previous studies have shown that recent immigrants often experience the ‘liability of newness,’ which may impede their voting participation (Bloemraad Citation2006, 78; Ramakrishnan and Espenshade Citation2001). In the present study, many of the participants had a sense of trust toward their husbands or in-laws in terms of candidate selection. These women’s trust was based on their perception that, relative to their husbands or in-laws, they were less informed and less knowledgeable about Korean politics. While employing endorsements of husbands and in-laws may seem to have neutral heuristic value on the surface, upon further investigation we found that the decision was shaped by women’s familial and societal position.

Most dependent voters made sense of their voting practice in the context of their gendered and ethnicized position within the family. The process of voting sometimes served as an opportunity for husbands and parents-in-law to assert or reinforce their superior social position by influencing or controlling marriage migrants’ political decision-making. Nina, a 33-year-old marriage migrant whose household included her parents-in-law, exemplifies the dependent voters we spoke with. She had experienced two elections since becoming a Korean citizen in 2011. When asked how she decided for whom to vote, Nina replied, ‘I asked my father-in-law and mother-in-law. “Oh, you only have to vote for that person, [candidate] number two,” they said (laughs). I don’t know very well [about the candidates], and the political system is quite different in the Philippines.’ As a young mother in a farming family, Nina’s activities outside the home were limited to attending church and participating in the events of a Filipina–Korean couples’ association in her county once or twice a year. Consequently, Nina, like the majority of the dependent voters, were mobilised to vote mostly by their Korean family members.

Some women’s political ignorance and apathy clearly led to dependence in terms of voting, even after more than a decade of residence in Korea, as seen in 40-year-old Mariel’s declaration: ‘I don’t know [the politicians]. I don’t know their education, their experiences. I don’t want to study who’s who and what’s what.’ Mariel said that for the past 10 years, she had always asked her husband which candidate to vote for so that she could finish the voting process quickly. Nevertheless, a closer examination of these women’s endorsement behaviour revealed that there is more than mere political ignorance or apathy at play. Further exploration of the women’s voting experiences revealed a self-perception of always knowing less and thereby being less of an ‘authentic’ and competent citizen relative to their husbands and in-laws. The alignment of marriage migrants’ voting choices with that of their spouses and in-laws, therefore, can be interpreted as deferential compliance. This acquiescence reflects the women’s gendered positions as wives and daughters-in-laws. It also reflects self-perceptions and ascribed view that, as foreigners, the marriage migrants are less knowledgeable citizens relative to their Korean husbands and in-laws.

Emily, a 56-year-old Filipina marriage migrant who had been the president of one of the largest Filipino organisations for more than a decade explained why so many Filipinas she knew followed the voting decisions of their husbands and in-laws:

It is said that there’s a Korean culture and tradition that women must follow their husbands, and especially if the wives are living with their mothers-in-law or parents-in-law, they should follow whatever they say to avoid a quarrel. So [they] just follow [their voting decisions].

Emily’s interpretation resonates with how Annie, a 42-year-old mother of three who migrated 14 years ago, experienced voting. Annie became a citizen in 2005 and has voted ever since. Her choice has always coincided with that of her husband:

How do you decide who to vote for?

From my husband. I ask him, ‘Who’s your favorite candidate? Who’s doing well?’

Then you follow him?

Yes (laughs). Sometimes I would tell him ‘Sojin’s daddyFootnote2, I heard this one [candidate] did something [bad],’ then he goes, ‘Oh, you shouldn’t be bothered. You’re supposed to give credit to what I say.’ (laughs) It’s like that.

The fact that most of the interviewed women had higher educational credentials than their husbands and that they had no difficulty obtaining information about Korean politics did not seem to diminish their sense of knowing less. Given that the women in this study experienced voting mostly as a family affair, where they were mobilised by their husbands and/or in-laws, the sense of being an inferior citizen should be understood as constructed within the hierarchical gender and ethnic ideology that is prevalent in Korean society (Kim Citation2018). The adage that ‘Men are heaven in Korea’ frequently came up during the interviews with the study participants, underscoring the message that these women received about their social position within the marital union. This male authority extends to the in-laws, in combination with seniority as a basic principle in organising hierarchical relationships within the Korean Confucian family (Cho Citation1998). Women’s self-perception of political ignorance was juxtaposed with the gendered and ethnicized hierarchy to shape women’s dependent voting choices.

Independent voters: choosing one’s own candidate

There were two distinctive subgroups of marriage migrants who voted independently from the start: overt and covert voters. All of the independent voters were subjected to varying degrees of conforming pressures from their husbands and/or in-laws, with covert independent voters facing the strongest familial demands to follow the voting choices of Korean family members. However, through a complex interplay of household living arrangements, human capital, and personal resources, both groups of women were able to avoid, resist and/or deflect familial attempts to influence their voting decisions; thus, exhibiting strong performative citizenship.

Women who made overt independent voting decisions from the start tend to live with only their nuclear family or to be divorced or widowed. Some of these women’s prior political socialisation in the Philippines and interest in politics led them to actively learn about Korean politics and choose their own candidates. This indicates that nuclear family living arrangements, in addition to interest in politics, are important drivers of independent voting behaviour. For women who were divorced or widowed, the absence of (ex)spouses and/or in-laws in their daily lives meant that they were relatively free from pressures to conform. Likewise, for independent voters in nuclear families, the influence of husbands was either non-existent or not strong because the marriage migrants could draw upon personal and/or external resources to contest their spouses’ attempts to control their voting decisions. As such, cultural citizenship dynamics were fairly weak for overt independent voters.

Emily, a long-time leader of a Filipina organisation in her city who was introduced earlier, exemplifies the overt independent voters we interviewed. Emily had a close relationship with the mayor, who had been supportive of various activities of her organisation. Although she had a relatively low level of fluency in Korean compared with women who arrived in the mid-1990s, the language barrier did not prevent her from ‘educating’ her husband about how they should go about selecting their candidates: ‘He was like, “Oh, this one is more famous” and voted for the candidate. … I said, “No, we should study their platform in the government first.”’ Emily’s prior experience of working as a district secretary for a congresswoman in her hometown in the Philippines, coupled with her educational background in law, gave her the necessary credentials to question her husband’s candidate choice and resist his attempt to influence her choice of candidates. However, she also added, half-jokingly, ‘I’m very lucky I don’t have a mother-in-law [living with us]. Maybe if I had a mother-in-law, I would always [follow her voting decision], you know (laughs).’ Emily’s case illustrates the importance of having prior experience with and an active interest in politics but also the crucial absence of influential cohabiting in-laws. These factors facilitated the acquisition of political knowledge and self-perceived competence in Korean politics.

Notably, a handful of the marriage migrants (5 out of 25) reported that their overt independent decisions were made only after confirming their husbands’ indifference to electoral participation. For these women, their spouses’ political apathy meant that they were free to choose whichever candidate they wanted without having to worry about managing their husbands’ preferences, too. These cases illustrate the complex interplay between women’s performative citizenship and the gendered and ethnicized expectations placed upon them by Korean society. Specifically, marriage migrants, even those who voted independently, have internalised the expectation that voting in damunhwa households should be a family affair. Nonetheless, the absence of interference from their husbands leads us to consider these women as facing weak cultural citizenship dynamics in the family.

Another subgroup of independent voters reported engaging in covert voting behaviours. As voting decisions were not always shared publicly, pretending to conform sufficed to deflect the familial expectations faced by some of the marriage migrants. Nenita, a 40-year-old woman who served as the president of the Philippine–Korean couples’ association in her rural county, recalled several quarrels with her husband during the local election campaign period in 2014 because he wanted to ‘dictate’ her decision: ‘He shouted, “Vote [for] the person I told you, he’s the best, blah blah blah … That man [you chose] is corrupt; never vote for him, understand?” He would repeat what he said almost every day before the election.’ Nenita did not follow her husband’s choice and instead decided on a candidate whom she had researched; seeking information about political candidates on her own is something that Nenita has done since becoming a Korean citizen in 2004. After 13 years of marriage and despite her leadership role in co-ethnic associational activities, she still faced pressure from her husband to align her voting decisions with his. Nenita made sense of her husband’s interference by describing him as a ‘Joseon period namja [man],’ an idiom referring to Korean men who are conservative and patriarchal. Although she did not actively try to persuade him about her decision, she also did not succumb to the pressure to change, saying, ‘He doesn’t have any idea [for] whom I vote. I am the only one [who] knows it.’

As Nenita’s story illustrates, women’s covert independent decision was an attempt to give the appearance of conformity to hegemonic expectations while simultaneously exercising their ideal understanding of political citizenship. Cognisant of their position in the family hierarchy, these women pretend to go along with the voting decisions of their husbands and in-laws, performing the role of a deferential wife and daughter-in-law. Ella, one of a few (3 out of 25) independent voters who were living in intergenerational households at the time of the interview, had lived with her in-laws since she married and immigrated to Korea in 1999. When it comes to voting, she knew how to appease her mother-in-law, who she described as vocal regarding voting decisions. When her mother-in-law said, ‘Let’s vote for this one,’ she always replied, ‘Okay, let’s go for that one,’ but her real decision was made on the basis of what was in the news and the official brochures delivered during the election period:

When you get into the polling place, [your actual voting decision] cannot be seen. I’m supposed to choose what I want. [But in front of my mother-in-law,] I just say ‘Yeah, let’s vote for the one,’ even though I do not like [that candidate].

Through conforming or pseudo-conforming voting practice, Filipina marriage migrants tended to reaffirm their subordinate positions and to reproduce the hierarchical relations in the family. However, as Ella’s story illustrates, what the women earned in return—being considered a trusted member of a Korean family, which also has implications for acceptance and belonging in the broader Korean society—seemed preferable to openly challenging and upsetting their daily lives.

Transitioned voters: emerging sense of knowing better and new identity

Filipinas’ experiences of voting as a ‘family affair,’ where their supposedly more knowledgeable and authentic husbands and/or in-laws directed them to make the ‘right’ voting decisions, were called into question for some of the women, who realised that these family members were not in a position to ‘teach’ them. Some participants had undergone transitions in how they made sense of their voting decisions as they repositioned themselves vis-à-vis their husbands and in-laws and developed their own, independent political perspectives. These women challenged their subjugated position in the family, invoking their better education, financial autonomy and material contributions to the household to justify and/or reinforce their independence. Bell’s story below is illustrative of the transitioned voters.

Belle, a 45-year-old widower and mother of one child initially voted for the same candidates that her parents-in-law did. But Belle declared that she would ‘absolutely never’ follow them again: ‘I can get better information than my parents-in-law. They are illiterate, and I [have] survived without their help. I didn’t ask for a single penny from them.’ As one of the few Filipina marriage migrants in her rural county earning their living by teaching English, Belle had raised her son without help from her parents-in-law following her husband’s death more than a decade earlier. Her self-definition as an independent provider for her family and as a survivor made her question how she had voted previously.

Through their everyday experiences in the families and local communities as ethnic minorities, women also developed a ‘group-based ethos,’ which often leads to political action (Collins Citation2010, 15). The emerging sense of belonging to their local co-ethnic communities and communities of damunhwa was closely tied to their firsthand experience in community organising. After the women began to understand Korean politics as something closely related with their everyday community life and challenged their ascribed position as ‘inferior’ members within the family, they no longer based their voting decisions on what their husbands or in-laws wanted. These women’s regular participation in community gatherings also often resulted in direct encounters with political candidates, contributing to the women’s perceptions of ‘knowing better.’

Marjorie’s transition demonstrates this point well. Marjorie, a 35-year-old who migrated to Korea in 2000, had led an association of more than 220 Filipino/a migrant wives and workers since 2007, facilitating members’ gatherings and organising seasonal sports leagues. As an official contact person of the association, Marjorie had established close relationships with a Korean nongovernmental organisation and with the religious leaders in her city. Since becoming a Korean citizen in 2003, Marjorie has voted in every election. Remembering several initial elections where she voted following her husband’s decisions, she said, ‘My husband used to tell me whom to vote [for]. … But now I know better. … You know, the Conservative Party is strong in this Southeast region. I know that, so I go for the Conservative Party. Now I’m also looking into the Democratic Party’ (emphasis added).

Marjorie and other transitioned voters rearranged their acts of voting to construct themselves as members of their emerging new belongings and in doing so, challenging their gendered and ethnicized positions in the family and larger host society. With women contributing significantly to the family economy, acquiring political knowledge and developing direct contacts with politicians through community engagement, they rarely reported being concerned about following the voting decisions of their husbands or in-laws. Forging an independent political perspective and sense of belonging outside the realm of the Korean family was particularly prominent among those who were divorced from their Korean husbands. By engaging in community gatherings through various multicultural family-related events and activities and/or voluntary associational activities, these women developed a new collective identity—not as wives or daughters-in-law in Korean families, but rather as members of multicultural families, which are legally recognised by the Korean government as a group and becoming increasingly visible in political scene as mentioned earlier.

Similar to what scholars have found about immigrant women’s political participation (Hardy-Fanta Citation1993; Jones-Correa Citation1998), these women’s community engagement fostered their interests and engagement in Korean politics. However, whereas previous studies on Latin American immigrants found that female immigrants were often marginalised from the leadership positions of ethnic organisations and tended to value grassroots community organising over electoral politics (Hardy-Fanta Citation1993), transitioned voters in our study who were active in community organising took leadership roles in their associations and were empowered to vote independently. For them, the performative aspect of voting independently, rather than the representational value of casting a vote, seemed to matter more because it signified their economic independence within the marital family and an emerging new identity as damunhwa.

Women’s performative citizenship that resists their marginalised status sometimes went beyond casting ballots. The contradictions between their new-found identity and their marginalised status in their families and in the larger society, prompted some of the marriage migrants became more actively engaged in formal politics. Such was the case for Erin, who ran for office; thereby demonstrating the most active form of formal political participation among the participants. Having lived in Korea for 23 years, Erin ran for a city council seat in the 2014 local election. When asked about her volunteer activism for migrant wives and workers, which she attributes to influencing her decision to run for office, she responded:

I got angry as I got to know more. If I’d rather stay ignorant, I would think, ‘Well, this is the way it is.’ When I knew nothing about Korea, my husband or other people around me would say, ‘You should do this and that in Korea.’ I was like, ‘Oh yes, I should follow.’ However, as we [migrants] learn things more, we get to think about things like human rights and what we can do about it. We deserve so much more than this. I felt like we are just being controlled. … They [Koreans] always see us as unable and weak. I just want to change their minds [by running for the candidacy].

As women develop a sense of ‘knowing better’ and as they realise the contradictions inherent in their ascribed position as inferior citizens, they endeavour to forge self-defined connections between themselves and their families and communities, as competent providers for their families and knowledgeable community members. The act of voting takes on different meaning as part of this development, evolving from a family affair into an act of contestation, transforming their social position and image as less authentic citizens. As these developments unfolded, women redefined the ways in which they voted—no longer deriving their social or political identities from those of their husbands and in-laws, but, rather, putting forth their own experiences as marriage migrants in multicultural families and communities.

Conclusion

By highlighting how marriage migrant women practice and attach varied and changing meanings to the act of voting, this study sheds light on how specific social location influences immigrant voting. We have shown that the voting practices of most Filipina marriage migrant women, who are in a marginalised social position in Korea, are realised in the context of a gendered and ethic hierarchy within the family. Given that most of these women at least initially experience voting as a family affair, mobilised primarily by their husbands and/or in-laws, voting is experienced in line with their everyday lived realities of hierarchy and dependency. Their self-perceptions of being an inauthentic and less knowledgeable citizen led them to derive their sociopolitical identities, which are manifested in their voting choices, from their husbands and in-laws.

Realising the contradictions between their definitions of themselves and their ascribed subjugated position in the family and society, some women experienced a transition to independent voting. As they begin to value their own situated knowledge (Haraway Citation1988), which is firmly grounded in their own experiences and perceptions about themselves, these women questioned the hegemonic expectations of the gender and ethnic hierarchy prevalent in Korean society. Through the act of independent voting based on their own understanding of their situation and experience as marriage migrant community members, women constructed themselves as legitimate members of Korean society. The women’s seemingly passive and dependent voting behaviour reflects their incorporation into Korean society primarily as dependents of their Korean husbands and as stigmatised others. The path to political empowerment for these women thus inevitably involves a process of forging and advancing self-defined perspectives.

Our findings illustrate how viewing immigrant voting through the perspectives of cultural and performative citizenship can reveal varied meaning and practice of voting beyond its intrinsic function of political representation. Achieving political equality in participatory democracy often requires more than guaranteeing ‘one person, one vote.’ When the premise of universal citizenship does not recognise disadvantaged groups, as Young (Citation1989, 259) has argued, ‘equality of citizenship makes some people more powerful citizens’ than others, reproducing the existing oppression of certain groups. As the present study has shown, examining voting as an everyday practice of cultural citizenship and tracing its transition to a transformative citizen act can provide a more nuanced understanding of immigrant voting and political participation.

Ethics declarations

McGill University, REB File #465-0514

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions on this article. We express our deepest gratitude to all the participants of this study who generously shared their stories and made this research possible.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Since 2005, immigrants to Korea who have held permanent residency for more than three years have been eligible to vote in local elections.

2 It is a casual custom to call a husband by one’s offspring’s name in Korea.

References

- Ariun, Shukhertei. 2011. “Iju Oeguginui Jeongchi Jeonghyang: Gyeolhoniminjaui Jeongchijeong Chamyeo Yangsangeul Jungsimeuro [Political Attitude of Foreign Immigrants: With a Special Emphasis on the Participatory Orientation of Immigrants by Marriage].” Masters’ thesis, Seoul: Hankuk University of Foreign Studies.

- Bazeley, Patricia, and Kristi Jackson. 2013. Qualitative Data Analysis with NVivo. London: Sage Publications Limited.

- Bélanger, Danièle, Hye-Kyung Lee, and Hong-Zen Wang. 2010. “Ethnic Diversity and Statistics in East Asia: ‘Foreign Brides’ Surveys in Taiwan and South Korea.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 33 (6): 1108–1130.

- Bloemraad, Irene. 2006. Becoming a Citizen: Incorporating Immigrants and Refugees in the United States and Canada. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bueker, Catherine Simpson. 2005. “Political Incorporation among Immigrants from Ten Areas of Origin: The Persistence of Source Country Effects.” International Migration Review 39 (1): 103–140.

- Butler, Judith. 2004. Undoing Gender. New York; London: Routledge.

- Cho, Haejoang. 1998. “Male Dominance and Mother Power: The Two Sides of Confucian Patriarchy in Korea.” In Confucianism and the Family, edited by H. Slote Walter, and George A. De Vos, 187–207. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Collins, Patricia Hill. 2010. “The New Politics of Community.” American Sociological Review 75 (1): 7–30.

- Foucault, Michel. 1980. “Two Lectures.” In Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977, edited by Colin Gordon, 78–108. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Foucault, Michel. 1982. “The Subject and Power.” Critical Inquiry 8 (4): 777–795.

- Freeman, Caren. 2005. “Marrying Up and Marrying Down: The Paradoxes of Marital Mobility for Chosonjok Brides in South Korea.” In Cross-Border Marriages: Gender and Mobility in Transnational Asia, edited by Nicole Constable, 80–100. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Gidengil, Elisabeth, and Dietlind Stolle. 2009. “The Role of Social Networks in Immigrant Women’s Political Incorporation.” International Migration Review 43 (4): 727–763.

- Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599.

- Hardy-Fanta, Carol. 1993. Latina Politics, Latino Politics: Gender, Culture, and Political Participation in Boston. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Hsia, Hsiao-Chuan. 2009. “Foreign Brides, Multiple Citizenship and the Immigrant Movement in Taiwan.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 18 (1): 17–46.

- Im, Hyuk, and Iljae Nam. 2014. “Gyeolhonijuyeoseongui Jeongchichamyeo Yeonghyangyoin Bunseok [The Analysis of Factors on Political Participation of Female Marriage Migrants].” Korean Political Science Review 48 (5): 43–65.

- Isin, Engin. 2017. “Performative Citizenship.” In The Oxford Handbook of Citizenship, edited by Ayelet Shachar, Rainer Bauböck, Irene Bloemraad, and Maarten Peter Vink, 500–523. Oxfor: Oxford University Press.

- Jones-Correa, Michael. 1998. “Different Paths: Gender, Immigration and Political Participation.” International Migration Review 32 (2): 326–349.

- Jones-Correa, Michael. 2001. “Institutional and Contextual Factors in Immigrant Naturalization and Voting.” Citizenship Studies 5 (1): 41–56.

- Jones, Gavin W. 2012. International Marriage in Asia: What Do We Know, and What Do We Need to Know? Singapore: Asia Research Institute (ARI), National University of Singapore Queenstown.

- Jones, Gavin, and Hsiu-hua Shen. 2008. “International Marriage in East and Southeast Asia: Trends and Research Emphases.” Citizenship Studies 12 (1): 9–25.

- Kandiyoti, Deniz. 1988. “Bargaining with Patriarchy.” Gender & Society 2 (3): 274–290.

- KIHSA. 2010. “Jeonguk Damunhwa Gajok Siltae Josa Yeongu [2009 National Survey on Multicultural Families].” Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs.

- Kim, Hyun Mee. 2007. “The State and Migrant Women: Diverging Hopes in the Making of ‘Multicultural Families’ in Contemporary Korea.” Korea Journal 47 (4): 100–122.

- Kim, Nora Hui-Jung. 2012. “Multiculturalism and the Politics of Belonging: The Puzzle of Multiculturalism in South Korea.” Citizenship Studies 16 (1): 103–117.

- Kim, Minjeong. 2013. “Citizenship Projects for Marriage Migrants in South Korea: Intersecting Motherhood with Ethnicity and Class.” Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society 20 (4): 455–481.

- Kim, Yeong-Hwan. 2017. “Husband Tore Wife’s Ballot ‘Why do you vote for the candidate?’” The Hankyoreh, May 8, 2017.

- Kim, Minjeong. 2018. Elusive Belonging: Marriage Immigrants and “Multiculturalism” in Rural South Korea. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Kim, Won-Hong, Hae-Yeong Kim, and Eun-Gyeong Kim. 2001. “Haebang Hu Hangukyeoseongui Jeongchichamyeo Hyeonhwanggwa Hyanghugwaje [Korean Women’s Political Participation since Independence and the Task Ahead].” Korean Women’s Development Institute.

- Kim, Hyuk-Rae, and Ingyu Oh. 2011. “Migration and Multicultural Contention in East Asia.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (10): 1563–1581.

- Kim, Ilju, and Zoua M. Vang. 2020. "Contending with Neo-Classical Patriarchal Bargain: Filipina Marriage Migrants' Negotiations for Naturalization in South Korea.” Citizenship Studies 24 (2): 209–227.

- Koo, Bon Sang, Sang-Jin Yoon, and Jun Young Choi. 2015. “20∼30dae Namnyeo Yugwonja Tupyoyului Seongbyeol Yeokjeon Hyeonsange Gwanhan Peojeul [The Puzzle of the Reverse Gender Gap in Young Korean Voter Turnout].” The Korean Association of Party Studies 14 (2): 115–140.

- Lau, Richard R., and David P. Redlawsk. 2001. “Advantages and Disadvantages of Cognitive Heuristics in Political Decision Making.” American Journal of Political Science 45 (4): 951–971.

- Lee, Hye-Kyung. 2008. “International Marriage and the State in South Korea: Focusing on Governmental Policy.” Citizenship Studies 12 (1): 107–123.

- Lee, Hyunok. 2012. “Political Economy of Cross-Border Marriage: Economic Development and Social Reproduction in Korea.” Feminist Economics 18 (2): 177–200.

- Lee, So Young. 2013. “2012 Hanguk Yeoseong Yukwonjaui Jeongchijeok Jeonghyanggwa Tupyohaengtae [Political Orientation, Attitude and Electoral Behavior of the 2012 Korean Female Voters].” The Korean Political Science Association 47 (5): 255–276.

- Lee, Yong Seung, and Yong Jea Lee. 2013. “Ijumin Jeongchichamyeo Yeonghyangyoine Daehan Tamsaekjeok Yeongu: Daegu Gyeongbukjiyeok Gyeolhonijuyeoseongeul Jungsimeuro [A Groping Study on Effective Factors of Political Participation of Marriage Migrants in Daegu and Gyeoung-Buk Province].” Minjok Yeonku [Ethnic Studies] 53: 110–130.

- McNevin, Anne. 2009. “Contesting Citizenship: Irregular Migrants and Strategic Possibilities for Political Belonging.” New Political Science 31 (2): 163–181.

- McThomas, Mary. 2016. Performing Citizenship: Undocumented Migrants in the United States. New York, London: Routledge.

- Meyer, Rachel, and Janice Fine. 2017. “Grassroots Citizenship at Multiple Scales: Rethinking Immigrant Civic Participation.” International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society 30 (4): 323–348.

- MOGEF. 2013. 2012 Jeonguk Damunhwagajok Siltaejosa Yeongu. [A Study on the National Survey of Multicultural Families 2012] Report for the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. Report no. 2012–59, January, South Korea.

- MOGEF. 2019. “2018 Jeonguk Damunhwagajok Siltaejosa Yeongu [A Study on the National Survey of Multicultural Families 2018].” Report for the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family. Report no. 2019–01, March, South Korea.

- Ong, Aihwa. 1996. “Cultural Citizenship as Subject-Making: Immigrants Negotiate Racial and Cultural Boundaries in the United States [and Comments and Reply].” Current Anthropology 37 (5): 737–762.

- Ong, Aihwa. 1999. Flexible Citizenship: The Cultural Logics of Transnationality. Durham & London: Duke University Press.

- Ong, Aihwa. 2003. Buddha Is Hiding: Refugees, Citizenship, the New America. London, England: Univ of California Press.

- Ramakrishnan, S. Karthick, and Thomas J. Espenshade. 2001. “Immigrant Incorporation and Political Participation in the United States.” International Migration Review 35 (3): 870–909.

- Rolfe, Meredith. 2012. Voter Turnout: A Social Theory of Political Participation. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Ryu, Yigeun. 2006. “Be Scared of Migrant Women’s Votes.” Hankyoreh 21, December 28, 2006.

- Strauss, A., and J. Corbin. 1998. “Section II: Coding Procedures.” In Basics of Qualitative Research: Procedures and Techniques for Developing Grounded Theory (Second Edition), 57–142. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Voicu, Bogdan, and Mircea Comşa. 2014. “Immigrants’ Participation in Voting: Exposure, Resilience, and Transferability.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (10): 1572–1592.

- Wang, Hong-zen, and Danièle Bélanger. 2008. “Taiwanizing Female Immigrant Spouses and Materializing Differential Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 12 (1): 91–106.

- White, Stephen, Neil Nevitte, André Blais, Elisabeth Gidengil, and Patrick Fournier. 2008. “The Political Resocialization of Immigrants Resistance or Lifelong Learning?” Political Research Quarterly 61 (2): 268–281.

- Young, Iris Marion. 1989. “Polity and Group Difference: A Critique of the Ideal of Universal Citizenship.” Ethics 99 (2): 250–274.