ABSTRACT

This paper tested the sometimes suggested but rarely tested idea that local ties are more important for migrants than for natives. Using nationally representative data from the Netherlands Longitudinal Lifecourse Study on first- and second-generation Turkish and Moroccan migrants aged 18–45 in the Netherlands in 2009 (N = 1607) and a comparison group of natives (N = 1979), this study described how important local ties were for people with and without a migrant background. The focus was on the amount of contacts with people in the neighbourhood, the presence or absence of parents in the neighbourhood and the geographic dispersion of the core discussion network. Models were estimated to explain differences between migrants and natives using information on socioeconomic status, life course variables, religiosity and neighbourhood characteristics. Findings showed that migrants were more strongly embedded in the neighbourhood than natives and that this difference could in part be explained by the lower socioeconomic status and higher levels of religiosity of migrants. Moreover, among migrants, parents were considerably more likely to live in the same neighbourhood and this played a major role in understanding the more local orientation of migrants. It is concluded that it is important to reconsider ‘family neighbours’ in empirical and theoretical studies of neighbourhood integration.

Introduction

The importance of local ties has been a classic theme in the social sciences. Studies of urbanisation have critically examined the assumed decline of neighbourhood ties during the modernisation process (Fischer Citation1982; Wellman and Leighton Citation1979), with recent evidence suggesting a modest long-term decline in interactions with neighbours (Fischer Citation2011). Social network studies have examined the spatial distribution of core discussion networks and the degree to which local ties are important for information and support (Wellman and Wortley Citation1990). Family studies have examined how close family members live to each other, how this has changed over time and how this is associated with solidarity in families (Chudnovskaya and Kolk Citation2017; Steinbach et al. Citation2020). Good relationships with neighbours are believed to enhance individual health and wellbeing (Aminzadeh et al. Citation2013) and can, under certain conditions, turn neighbourhoods into communities, thereby fostering social cohesion at the macro level (Volker, Flap, and Lindenberg Citation2007).

Local ties are sometimes believed to play a special role in migrant communities. Theoretically, there are several arguments suggesting that migrants are more strongly attached to the neighbourhood than natives (migrants in this paper refer to both the first and second generation). First, migrants are more likely to be lower educated and to have manual and unskilled jobs than natives. Because there is an inverse socioeconomic gradient in the degree to which people are integrated in the neighbourhood, in line with the classic idea of ‘working-class neighborhoods’ (Gans Citation1962; Young and Willmott Citation1957), migrants may be integrated more strongly in the neighbourhood than natives. Second, migrants often have a greater demand for social and practical support because of their migration experience. Because many forms of support are more likely to be given when the distance to potential support givers is small (Silverstein and Bengtson Citation1997), neighbourhood ties may be more relevant for migrants. Third, due to prejudice in parts of the majority population, migrants may feel less accepted in society and therefore have a preference to interact within the ethnic group. Because of the geographical segregation of ethnic groups, such ties are more often found within than outside of the neighbourhood.

Counterarguments exist as well, however. Notions of migration and transnationalism would suggest that the local context is less relevant for migrants as a source of social and instrumental support (Mazzucato Citation2015; Portes, Haller, and Guarnizo Citation2002). Moreover, migrants more often live in urban and deprived neighbourhoods and in such neighbourhoods, local ties are believed to be weaker on average (Sampson, Morenoff, and Gannon-Rowley Citation2002). For these reasons, neighbourhood contact may also be less rather than more common among migrants than among natives.

Empirical evidence on this issue is limited. Studies have analysed a variety of indicators of neighbourhood cohesion at the individual level (Fong and Hou Citation2017; Lancee and Dronkers Citation2011; Tolsma, van der Meer, and Gesthuizen Citation2009; Volker and Flap Citation2007; Volker, Flap, and Lindenberg Citation2007), but few studies have analysed differences in the volume of neighbourhood contact between migrants and natives. Studies in the US, Austria and the Netherlands showed that members of ethnic and racial minority groups interacted more frequently with neighbours than members of the majority (Barnes Citation2003; Kohlbacher, Reeger, and Schnell Citation2015; Tolsma and van der Meer Citation2018). There is also some evidence showing more proximity between parents and adult children among ethnic minorities than among the majority (Chan and Ermisch Citation2015; Reyes, Schoeni, and Choi Citation2020). In contrast to these findings, other studies have pointed to problems of social isolation and marginalisation of migrant groups, especially for new groups and recent immigrants (Kemppainen et al. Citation2020; Wessendorf and Phillimore Citation2019).

In this contribution, I compare the contacts and networks of people from Turkish and Moroccan origins in the Netherlands to those of the native majority. Three aspects of local ties will be studied. First, I assess how frequently people have contact with neighbours. Neighbourhood contacts are generally believed to be weak ties, but they can also include strong ties. Second, I use data from core discussion networks to assess how often the strong ties that people have are within the neighbourhood (Volker and Flap Citation2007). Third, I use data on intergenerational proximity, and in particular, on whether respondents live in the same neighbourhood as their parents. Fourth, I study interconnections between the different forms of contact. Specifically, I examine the impact of intergenerational proximity on neighbourhood contacts and local network ties, thereby addressing the notion that ‘family neighbours’ can be important for understanding variation in neighbourhood integration (Logan and Spitze Citation1994) and possibly also explain differences between migrants and natives.

Next to describing differences between migrants and natives with respect to the locality of their social ties, the second goal of this contribution is to explain variations in the locality of ties among migrants and natives. To assess this, I use previous insights into neighbourhood contacts on the influence of socioeconomic characteristics, life course characteristics, religiosity and the neighbourhood context (Campbell and Lee Citation1992; Volker and Flap Citation2007). I examine if these determinants explain differences between migrants and natives (mediating effects) and I explore if they have similar effects in the two groups (moderator effects). No previous study has systematically assessed – across a range of measures – if migrant groups have a more local orientation than non-migrants and no study has tried to explain possible gaps in an empirical fashion.

Background

To explain individual variations in local ties, authors have proposed theoretical mechanisms about need, preferences and opportunities (Marsden Citation1990; Volker and Flap Citation2007). The concept of need applies to the demand for social, emotional, practical and financial support. A greater demand for support may lead to a stronger orientation toward local ties because many forms of support are more easily given across smaller distances (Campbell and Lee Citation1992). Some people may also have a stronger individual preference for interactions outside of the local area than others. Such preferences may stem from more general values and attitudes that people have. For example, people who are more open and more cosmopolitan may be less oriented towards the local community. Finally, opportunities and constraints play a role because interaction in the neighbourhood depends on the supply of contact (Volker, Flap, and Lindenberg Citation2007). In part, such opportunities depend on the population composition of the local area and on related preferences for interacting with ethnically similar others. For another part, opportunities depend on other characteristics, such as how often people are present in the neighbourhood, how easy it is to meet others and how trusting other people are.

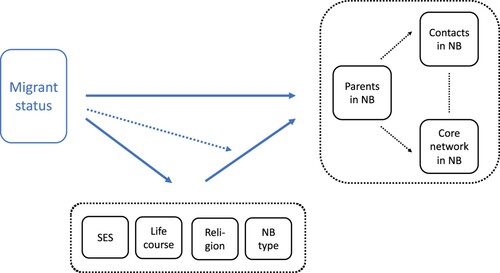

Based on this general framework, four groups of determinants can be considered: socioeconomic characteristics, life course characteristics, religiosity and neighbourhood characteristics. For each of these types of characteristics, hypotheses will be developed about how they affect local ties among migrants and natives. Moreover, hypotheses will be developed about the relationships among the different types of contact. Specifically, I will examine how the presence of parents in the neighbourhood may affect neighbourhood contact and local networks as well as how differences between migrants and natives are affected by differentials in intergenerational proximity. gives an overview of the conceptual model that is examined in this paper.

Socioeconomic determinants

Neighbourhood attachment is believed to be dependent on socioeconomic status. Studies have found that higher educated people live further away from their parents (Kalmijn Citation2006; Shelton and Grundy Citation2000) and have less frequent neighbourhood contact than the lower educated (Tolsma, van der Meer, and Gesthuizen Citation2009). When looking at the number of neighbours in core discussion networks, the evidence is less consistent (Moore Citation1990; Volker and Flap Citation2007). Lower status groups tend to have smaller networks, and hence fewer neighbours in their network, but they also have more frequent or more intensive contact with neighbours than higher status groups (Campbell and Lee Citation1992).

Several explanations have been suggested for these differentials. First, the schooling and labour market options of higher status groups require more geographic mobility and this may weaken integration in the neighbourhood. The geographical distribution of schooling and job options often requires people to live further away from their community of origin and hence, further away from their parents. Second, authors have argued that higher status groups have fewer local ties because they are more strongly oriented towards large and diverse networks (Marsden Citation1987; McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Brashears Citation2006). These differences may be related to a more cosmopolitan orientation among the higher educated (Pichler Citation2012) and less traditional family values in this group (De Vries, Kalmijn, and Liefbroer Citation2009).

Status differences may in part explain differences in the locality of ties between natives and migrants, but there may also be moderator effects. Different predictions can be made, depending on the specific type of contact. For proximity to parents, one would expect weaker effects of education among migrants because migrants are concentrated in urban areas (CBS Citation2018). Whereas for natives, upward (educational) mobility often requires migration to (more) urban areas, for migrants, upward educational mobility does not necessarily require moving away from the community of origin. For contacts with neighbours, in contrast, one would expect socioeconomic effects to be stronger for migrants. Migrants often come from lower status backgrounds so that a higher education and occupation often go hand in hand with considerable upward mobility. Upward mobility may result in a declining orientation toward the ethnic community and indirectly to more interactions outside of the local community (van Maaren and van de Rijt Citation2020). It is expected that the effect of socioeconomic status on neighbourhood contacts is stronger for migrants than for natives, whereas the effect of socioeconomic status on intergenerational proximity will be weaker for migrants.

Another relevant socioeconomic variable is employment. People who are employed and who work more hours are believed to interact less often with neighbours than people who are not employed or who work fewer hours. The main reason for this lies in the more limited opportunities to have contact in the neighbourhood when people are away from home in the daytime. The employment effect is probably most salient for women since women have traditionally been more involved in the neighbourhood than men (Fischer Citation2011). For men, not being employed in the age group we look at (18–45) is often due to unemployment and since unemployment may carry a social stigma (Peterie et al. Citation2019), this may not necessarily lead to more contact with neighbours, despite the greater availability of time to do so. Because migrant women are less likely to be employed than native women (Khoudja and Fleischmann Citation2017), employment differences may explain in part group differences in neighbourhood contact.

Life course effects

Several studies have argued that the degree to which people are integrated into the neighbourhood depends on the stage of the life course they are in. Having children at home, especially younger children, is associated with increased contact with neighbours, whereas being married by itself is not (Kalmijn Citation2012; Rozer, Poortman, and Mollenhorst Citation2017). The reasoning is that the required care for children creates a need for support that can in part be met by neighbours. Moreover, having children increases opportunities for contact with neighbours because parents meet other parents via their children, especially when children go to school (Munch, Miller McPherson, and Smith-Lovin Citation1997). Life course effects may contribute to group differences because there are significant differences in marriage formation and fertility between migrants and natives (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek Citation2018). Analyses of external survey data among people aged 25–65 show that 60% of people with a Moroccan background and 63% of people with a Turkish background were living with a partner and children, compared to only 46% of people without a migration background.Footnote1

Another aspect of the life course that is relevant for neighbourhood contact is divorce and single parenthood (with the term divorce, I also include the separation of a cohabiting union). On the one hand, being divorced creates a need for contact with others, in particular, when people need to raise children on their own. Neighbours can be an important source of support under such conditions. On the other hand, in certain circles there could also be a social stigma surrounding divorce and single parenthood which may lead to either withdrawal from weak ties or to avoidance by others. It is expected that especially local ties will be implicated in negative normative effects (Kalmijn and Uunk Citation2007). Given the more traditional attitudes about single parents in Muslim countries (Norris and Inglehart Citation2012) and the lower divorce rates of people with Turkish and Moroccan origins in the Netherlands (Smith, Maas, and van Tubergen Citation2012), one would expect that among migrants in this study, the negative effect of social norms will work against the positive effect that is created by greater demand for support. Among natives, we would expect the positive demand effects of single parenthood to dominate.

Religion

Cultural factors may also play a role in people’s orientation toward the neighbourhood. One of the more relevant cultural variables in this respect is religion. One would expect that the more a person is embedded in a religious denomination, the stronger his or her orientation toward local ties will be. One reason for this is that people who are more religious on average have a more traditional and less cosmopolitan orientation (Halman and van Ingen Citation2015). Religiosity is also related to stronger obligations toward the family which may motivate people to live close to their parents, and hence, closer or in their origin community (Gans, Silverstein, and Lowenstein Citation2009). Another reason is that people who are more religious are more strongly embedded in a place of worship (church, mosque and synagogue). In a study of religion and neighbourhood ties, Dougherty and Mulder (Citation2020, 28) argued that

belonging to a local congregation may put congregants into more frequent contact with their neighbours and elevate their satisfaction with their neighborhood. After all, congregations are a social and physical place that offer various levels of social service engagement to their neighborhoods.

The importance of religion for building – predominantly local – communities has been a classic theme in sociology (Lenski Citation1961) but may have lost some of its relevance for people in current times as a result of mass transportation, modern communication technology and suburbanisation. Nonetheless, there is still some evidence that churches foster commitment to the neighbourhood (Dougherty and Mulder Citation2020; Kinney and Winter Citation2006). Moreover, the role of religious institutions may be especially important for migrant communities because religion is often a source of ethnic identity for new migrant groups. For this reason, the effects of religiosity on local ties could be stronger for migrants than for natives.

Neighbourhood effects

The degree to which people interact locally depends in part on characteristics of the geographical context (Volker and Flap Citation2007). The most frequently studied aspect of the geographical context is the degree of urbanisation. How rural and urban areas compare in terms of neighbourhood contact has been an important issue in classic debates about urbanisation and suburbanisation (Wellman and Leighton Citation1979). Older studies have found negative effects of urbanisation on neighbourhood contacts and networks (Beggs, Haines, and Hurlbert Citation1996; Sampson Citation1988), in line with the classic hypothesis of more anonymity in the city. Less is known about the role of urbanisation in contemporary research. It is expected that natives and migrants in more urban areas have less frequent contact with their neighbours than natives and migrants in less urban areas. If such urbanisation effects are found, they will suppress differences between migrants and natives, given the more urban location of migrants.

The ethnic diversity of a neighbourhood is often believed to reduce the level of cohesion in the neighbourhood (Putnam Citation2007). Empirical research has not provided much support for this hypothesis, however, especially not in European countries (van der Meer and Tolsma Citation2014). Moreover, for migrants, a potential ‘hunkering down’ effect of diversity will be counteracted by opportunity effects since diversity, as it is usually measured, is highly correlated with the share of migrants in an area. Assuming a preference for interacting within the ethnic group, ethnic diversity would then increase rather than reduce neighbourhood contact among migrants (Fong and Hou Citation2017). Theoretically, one would expect that diversity reduces the importance of local ties for natives while increasing the prevalence of such ties for migrants.

The quality of the neighbourhood probably plays a different role. Regardless of migrant status, it has been found that low-quality neighbourhoods – as indicated by economic disadvantage and social and physical disorder – are associated with less trust in others and more social isolation (Intravia et al. Citation2016; Ross and Mirowsky Citation2009). To the extent that low-quality neighbourhoods are characterised by disorder, they may be perceived as threatening which may lead to feelings of stress and powerlessness on the one hand, and to a sense of suspicion toward neighbours on the other hand. Given the lower quality of the neighbourhoods where migrants live, such effects may suppress differences in neighbourhood contact between migrants and natives.

Family ties and neighbourhood contact

In their classic study of neighbourhoods in New York state, Logan and Spitze (Citation1994, 472–473) found that family members were often (close) neighbours and concluded that ‘local community networks are founded on kinship ties, even today’. Although this was written decades ago, it is probably still a mistake to assume that neighbourhood contacts are only or primarily based on weak ties. The concept of ‘family neighbours’ also has implications for group differences. If migrants more often live close to their family, this could explain differences between migrants and natives in the volume of neighbourhood contact and in how many local members they have in their core network. In other words, there are expectations of both main and mediating effects of intergenerational proximity.

The presence of parents in the neighbourhood could affect how attached people are to the neighbourhood in two ways. First, there may be a direct effect. Research has shown a strong association between parent–child proximity and parent–child contact (Kalmijn Citation2006). People whose parents live in the neighbourhood will have more contact with their parents and will probably include the parents more often in their core network. As a result, these people will have more local contacts, simply because their parents are added to the local set of contacts. Second, proximity to parents creates links with other people in the area who are either other family members or non-kin and thus contribute to neighbourhood integration. These can be called spill-over effects. A way to disentangle these mechanisms is by looking at specific parts of the core network in the analysis.

Data, measures and methods

The paper used data from the Netherlands Longitudinal Lifecourse Study (NELLS) which was conducted in 2009. The NELLS was based on a two-stage stratified random sample of individual persons aged 15–45 who were residing in the Netherlands. Thirty municipalities were chosen, stratified by region and degree of urbanisation, and from the municipal registers, a random sample was obtained with an oversample of people with Turkish and Moroccan origins (first and second generation). Respondents were interviewed at home and also filled out a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. The overall response of the survey was 52% (De Graaf et al. Citation2010).

For the present paper, I selected respondents 18 and over who had at least one living parent and who did not live at home (N = 3586). I included native-born people with native-born parents and people who themselves or whose parents were born in Turkey or Morocco.Footnote2 The Moroccan and Turkish groups were combined since additional analyses showed that they were similar in terms of local ties. The data and analyses combined first- and second-generation migrants and a control was used for generation. Obviously, many respondents in the first generation had parents who were living abroad (74%), but since a substantial minority had parents who lived in the Netherlands (26%), it was decided to keep the first generation in the analysis.

Measures of dependent variables

Respondents were asked how often they had face-to-face contact with people in the neighbourhood. There were seven categories and these were recoded to a five-point variable, ranging from daily to never (see ). Core discussion networks were used to delineate networks (Marsden Citation1987). The name generator question was as follows: ‘With whom did you discuss important matters in the past six months?’. Respondents could name up to five persons. Before calculating the network measures, household members were removed from the list. Using respondent reports on the location of network members, I calculated three measures: (a) the number of network members living in the same neighbourhood, (b) the number of non-kin network members living in the same neighbourhood and (c) the number of family members living in the same neighbourhood (other than parents).

Table 2. Differences in local ties between migrants and natives.

To measure proximity, respondents were asked where their parent(s) lived. If parents were divorced or separated, I used information on the mother. Four outcomes were distinguished: (a) parent(s) living in the same neighbourhood, (b) parent(s) living in the same place but not in the same neighbourhood, (c) parent(s) living in a different place and (d) parents living abroad. For the regression models, category (a) was contrasted to (b) and (c) and children with parents living abroad were excluded. A multinomial regression model that included this category as a ‘competing’ outcome yielded the same effects.

Independent variables

Three socioeconomic variables were included: educational attainment, the number of working hours (with 0 for the non-employed) and an index of poverty. Because of expected gender differences, the working hours variable was interacted with gender (Moore Citation1990). To measure education, 10 ordered categories of schooling were recoded to the isled scale (Schröder and Ganzeboom Citation2014). To measure poverty, respondents were asked to indicate five financial problems if these occurred in the past three months (e.g. borrowing money to cover necessary expenditures, being late with paying the rent/mortgage). The index was the number of financial problems, ranging from 0 to 5.

To measure life course variables, I defined four groups: (a) living without a partner and without children (the reference category), (b) living with a partner and without children, (c) living with a partner and children and (d) living with children but without a partner (single parent). Religiosity was measured using an index of items that were equally applicable to natives and migrants: at least weekly church/Mosque attendance, regular praying, regular Bible/Koran reading and evaluating religion as ‘very important’ personally. The attendance variable was based on seven frequency categories and was dichotomised for use in the index (weekly or more versus less often). The importance of religion was originally in five categories and also dichotomised (‘very important’ versus less important). The index ranged from 0 to 4.

Respondents were located in 265 districts (neighbourhoods) with 20 respondents on average per district. The first neighbourhood measure was the share of non-western first- or second-generation migrants in the district, as calculated by Statistics Netherlands. I experimented with group-specific measures (e.g. the share of Turkish-origin persons) but these did not yield different conclusions. The second measure was an index of neighbourhood quality. Respondents were asked about the frequency of occurrence of seven problems in the neighbourhood (e.g. property damaged, groups of youth hanging out on the street, littering problems, and drug problems). Answering categories were occurs never, occurs sometimes and occurs frequently. The items were combined in an index (α = 0.80) and the index was aggregated to the district level. The means were based on all respondents in the data and corrected for the oversample of migrants and demographic and regional variation in nonresponse. The degree of urbanisation of the municipality was coded using the four-point scale provided by Statistics Netherlands (rural, small cities, cities and large cities).

The control variables were gender, age, the length of stay in the neighbourhood, whether parents were divorced or separated, and generational status. The second generation included both native-born respondents whose parents were born in Turkey or Morocco and foreign-born respondents who migrated before age 13.

Analytical strategy

In the first part of the analyses, I provide a detailed description of the differences between migrants and natives with respect to the explanatory variables and the three dependent variables.

In the second part of the analyses, I present ordered logit models for contact with neighbours, Poisson models for the number of local network members and logit models for the proximity to parents. For each outcome, I present a model with and without explanatory variables (Model 1 and Model 2). The set of independent variables was the same in each table, except that intergenerational proximity was an additional explanatory variable for neighbourhood contact and local network ties. In the models for the number of network ties, I present results with and without controlling for the size of the network. In each table, I also present a model for migrants and natives separately. To improve the comparison across groups with the nonlinear models used here (Mood Citation2010), average marginal effects were presented for the two subgroups. For the pooled models, normal coefficients were presented in all three regression tables. Interaction effects were estimated to assess whether the effects differed significantly between the groups.

The last part of the analyses contains mediation analyses. By comparing the migrant effect between Models 1 and 2, it could be assessed to what extent differences between migrants and natives were due to (compositional differences in) the explanatory variables. Differences in the migrant effects across models were tested using the khb module in Stata which corrects for scaling effects on parameters in nonlinear models.

The continuous independent variables were standardised so that effects reflect changes per standard deviation change in the independent variable. Missing values were imputed with multiple imputation and chained regression models in Stata, using 20 imputations and Rubin’s rules to combine the effects.

Findings

Migrants more often had children at home and less often lived with a partner without children compared to natives (). On average, migrants were lower educated than natives and migrant women worked fewer hours. Not surprisingly, the level of religiosity was much higher among migrants than among natives. Finally, as one would expect, the neighbourhoods of migrants contained a larger share of migrants, but their neighbourhoods were also considerably more urban and somewhat more deprived on average.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

In , data are presented on the three dependent variables. Clear differences emerged: 19% of the migrants had daily contact with their neighbours compared to 10% of the natives. When focusing on strong ties using the network variables, there were substantial differences in the overall size of the network, with migrants reporting fewer strong ties than natives. When adjusting for the size of the network, migrants had a significantly larger share of their network in the same neighbourhood (27%) compared to natives (17%). Among all migrants in the sample, 16% lived in the same neighbourhood as their parents, compared to 11% of the natives. When limiting the sample to respondents whose parents were living in the Netherlands, this contrast was larger (27% versus 12%).

Determinants of neighbourhood contact frequency

contains the models for the frequency of contact in the neighbourhood. Model 1 confirmed that migrants had more contact with neighbours than natives. Model 2 included the effects of the explanatory variables. In line with expectations, higher educated respondents had less frequent contact with neighbours. The working hours variable was interacted with gender (1 = male, 0 = female) so that the main effect applied to women. Women who worked and worked more hours had fewer contacts in the neighbourhood. There was a significant positive interaction with gender, showing that among men, there was no association between working hours and contact with neighbours (b = −.256 + .210 = −.046). Poverty was negatively associated with neighbourhood contact but the effect was small compared to, for example, the effect of education.

Table 3. Ordered logit models for neighbourhood contact frequency.

In line with past studies, respondents with children had more frequent contact with neighbours than respondents without children and without a partner. Single parents also had more frequent contact with neighbours. Living with a partner without children was not associated with neighbourhood contact. Additional analyses revealed a significant gender interaction, showing that in the combined sample, the positive effect of living with a partner and children on neighbourhood contact was stronger for women than for men (b = .395, p < .01). Religiosity had a significant effect as well. More religious persons had more frequent contacts in the neighbourhood than less religious persons.

The explanatory variables included indicators of intergenerational proximity. Having parents living in the neighbourhood was positively associated with neighbourhood contact, showing that ties to parents had an important – direct and/or indirect – impact on contacts with neighbours. Interesting was that having parents living in the same place but not in the neighbourhood was not related to neighbourhood contact, confirming the logic of the former effect.

The last column of shows to what extent the effects of the explanatory variables differed between migrants and natives. The average marginal effects refer to the probability of having daily contact. Two significant interaction effects appeared. In line with expectations, the positive effect of single parenthood was only significant for natives and not for migrants (with a significant interaction). The effect of religiosity on neighbourhood contact was only significant for migrants and not for natives. The effect of parents living in the same neighbourhood was stronger and (marginally significant) for migrants and not significant for natives. The difference was substantial but the interaction effect was insignificant.

Determinants of local network ties

The models for network ties are presented in . In Model 1a, there was no significant effect of migrant status on network ties. Hence, in an absolute sense, migrants do not have more local network members than natives. When we add a control for network size in Model 1b, a strong and significant effect of migrant status appeared. In other words, in a relative sense, migrants had more local network ties than natives but because they reported fewer network ties in general, there were no differences in an absolute sense.

Table 4. Poisson models for the number of network members in the neighbourhood.

According to Model 2, higher educated respondents were less likely to have local ties in their core network than lower educated respondents but this effect was not significant. Working hours were negatively related to having local network ties. Women who worked more hours had fewer local ties in their network. The significant gender interaction showed that this effect did not apply to men (−.132 + .141 = .009). Having a partner and children was associated with more local network ties. No effect was observed for religion, in contrast to the findings for neighbourhood contact. There were no clear neighbourhood context effects.

The strongest effects in the model for local network ties could be observed for intergenerational proximity. Just as was observed when analysing neighbourhood contact, it appeared that people who lived in the same neighbourhood as their parents had more local ties in the network. There was also a significant but smaller positive effect of having parents in the same place rather than in the same neighbourhood, on the inclusion of local network ties. Additional analyses were done to assess if and to what extent the null-effects of some of the other explanatory variables in Model 2 were due to the inclusion of the indicators of intergenerational proximity. One important change was the effect of education, which became significant and negative when intergenerational proximity was excluded (b = −.093, t = 2.66). This result was in line with the analyses of neighbourhood contact where I also found an educational gradient in local ties.

Substantial effects of intergenerational proximity were found. To better interpret these effects, more detailed analyses were done. Specifically, I looked at the non-kin part of the network and the family part of the network while excluding the parents. For both sub-networks, there was a strong and positive association between having parents in the neighbourhood and the locality of ties (i.e. b = 2.379, p < .01 for local family other than parents and b = .780, p < 0.01 for local non-kin). People whose parents were in the same neighbourhood, had more local non-kin members in their network and also more other local family members in the network. These findings suggest that the effect of ‘family neighbours’ on having local ties was not only due to the parents themselves being included in the network.

To what extent were the effects of the explanatory variables similar for migrants and natives? The average marginal effects in the last column of show that the effect of being a single parent was again only present for natives, in line with the results for neighbourhood contact. Moreover, in the group-specific models, a significant and positive urbanisation effect emerged for natives. Natives in more urban areas were more likely to have local ties in their network, in contrast to the classic thesis on urban life. Finally, there were some differences in the effects of intergenerational proximity. For both groups, having parents in the same neighbourhood had a significant effect on local ties, as expected. However, for migrants, an additional positive effect emerged for having parents living in the same place but not in the same neighbourhood.

Determinants of proximity to parents

The logit regression model for proximity to parents is presented in . The outcome is having a parent in the neighbourhood vis-à-vis having a parent living further away in the Netherlands. The first model confirmed that compared to natives, migrants were more likely to live in the same neighbourhood as their parents. The second model added the explanatory variables. There was a significant effect of educational attainment. Higher educated persons were less likely to live in the same neighbourhood as their parents. The effects of working hours and the poverty scale were insignificant. Few effects were observed of the life course variables. Religiosity had a strong effect, however. More religious persons were more likely to live in the same neighbourhood as their parents. There were also significant effects of the geographical context. In more urban areas, people were less likely to live close to their parents. In more deprived areas, in contrast, people more often lived close to their parents.

Table 5. Logit models for parents in the same neighbourhood.

The last two columns contained the average marginal effects of the group-specific models. These models revealed interaction effects for education, religiosity and urbanisation. Some effects were stronger for migrants, others were stronger for natives. The educational effect was present for both natives and migrants but stronger for natives. In contrast to this, the association of religion with proximity was larger for migrants than for natives. The effect of urbanisation was also stronger for migrants.

Mediation analyses

To what extent can we explain differences between migrants and natives with the explanatory variables? The first column of presents the mediation results for neighbourhood contact frequency. The results show that the effect of migrant status on neighbourhood contacts declined with 80% when the explanatory variables were added. The mediation test was significant and the remaining effect of migration status was no longer statistically significant. The variable-specific mediation analysis in further showed that the mediation of the migrant effect on neighbourhood contact could be attributed in particular to education, women’s working hours, parenthood and religiosity. In other words, migrants had more frequent contact with neighbours because they more often had children at home, worked fewer hours (among women) and were lower educated and more religious than natives. Religious and educational differences were especially salient in this explanation.

Table 6. Mediation analyses of differences between migrants and natives.

The results for local network ties are presented in the second column of . When comparing models for local network ties with and without explanatory variables, but already controlling for size, it was observed that the effect of migration status was attenuated with 68%. A mediation test showed that this reduction was significant (bchange = .263, p < 0.01). The detailed mediation analysis showed that having parents living in the same neighbourhood was the most important component of this mediation. Women’s working hours also played a role but a smaller one. Neighbourhood diversity suppressed the differences between migrants and natives.

The last column contains the results for parents living in the same neighbourhood. The migrant effect on intergenerational proximity declined when the explanatory variables were added, although it remained significant. A formal mediation test showed a significant change in the migration effect between the two models (bchange = .233, p < 0.01). The variable-specific mediation analysis showed that most of the mediation could be attributed to the fact that migrants on average were lower educated and more religious than natives. Urbanisation also contributed to the mediation but worked in an opposite direction, as can be seen from the negative percentage. In other words, the more urban residence of migrants suppressed the differences between migrants and natives with respect to how close they lived to their parents.

Conclusion and discussion

This paper presented evidence that migrants from two important Muslim groups in the Netherlands were more strongly integrated into the neighbourhood than natives. This evidence applied to neighbourhood contacts, local kin and non-kin networks, and proximity to parents. The greater orientation of first- and second-generation migrants toward the local community could in part be explained by compositional differences. Migrants were on average lower educated, were more religious, more often had children and had lower employment rates, at least among women (). Since these variables also affected the locality of ties, they could explain in part migrants’ greater orientation toward the neighbourhood.

Proximity to parents played an important role in the differences. Migrants more often lived in the same neighbourhood as their parents and this explained in part the differences between migrants and natives in the degree to which they had local ties in their network. Having parents in the same neighborhood also increased the volume of neighborhood contact, especially among migrants. Although some of the effects of intergenerational proximity could be tautological – parents could be the neighbours with whom people had contact – additional analyses pointed to spill-over effects as well. People who lived in the same neighbourhood as their parents more often had non-kin network members in the neighbourhood and also had more other local family members in the network. Spill-over effects of intergenerational proximity may also stem from children knowing more people in the neighbourhood because they lived there since childhood. The conclusion is that migrants are more strongly integrated in the neighbourhood than natives and that the family plays an important role in understanding these differences.

Two important offsetting forces were visible. First, migrants, and especially those in the first generation, more often had parents who were living abroad. This reduced the gap between the local orientation of migrants and natives but did not eliminate it. Even when calculating percentages for all migrants, including migrants whose parents lived abroad, a larger share of migrants had parents who were living in the same neighbourhood. Interesting was that no generational differences appeared for neighbourhood contacts and local network ties. There were obvious differences in how often parents lived abroad, but once this difference was adjusted for, no further generational effects appeared.

A second offsetting force was that migrants had smaller core discussion networks than natives. It was only when the share of local ties was analysed that differences in the locality of network ties became visible. In other words, group differences in the locality of network ties were suppressed by migrants reporting a smaller core network. Whether relative or absolute differences are more important is a difficult question. For understanding access to resources and practical support, it is probably more important to look at absolute differences. If the focus is on the type of orientation that people have, relative differences probably matter more. Methodological effects may play a role as well. Migrants more often included their partner in the network whereas natives did not. This could be due to a somewhat different understanding of the survey question. Even though the partner was not included in my measure, it may have reduced the amount of reporting on other network members. For this reason, a relative measure could be preferred.

There were three important interaction effects. The role of religiosity was stronger for migrants than for natives. Migrants, who were more religious, were more likely to interact locally. This resembles the classic role of Christian churches in fostering neighbourhood ties in cities and towns in the more distant past (Dougherty and Mulder Citation2020; Lenski Citation1961). Apparently, this social role of the church no longer applies to the native population, but it does seem to apply to the migrant population. An alternative interpretation is that religiosity, as an indicator of cultural integration (or a lack thereof), leads to a stronger focus on the in-group among migrants, indirectly leading to more contact within the neighbourhood. In additional analyses, however, I found no evidence that among migrants, attitudes toward the majority or feelings of identification with the ethnic group were related to neighbourhood contact (not reported in the tables). The only cultural variable that turned out to be relevant for neighbourhood contact was religiosity.

A second interaction effect was that of education. Education had similar effects on neighbourhood contacts for migrants and natives but different effects on intergenerational proximity. The often reported finding that education leads to a greater geographical distance from parents (Chudnovskaya and Kolk Citation2017) applied less clearly to migrants. The main interpretation for this exception lies in the more urban residence of migrants. Whereas attending tertiary education often requires migration of students to a city, many migrant children can attend college without moving away from their home community.

Third, there was evidence for interactions with life course variables. The positive effect of single parenthood on neighbourhood contact was only significant for natives, not for migrants. In general, having children is believed to foster neighbourhood integration (Kalmijn Citation2012), but apparently, this does not generalise to single parents in the migrant group. The counteracting impact of norms against divorce in these migrant groups possibly played a role in these differences. Direct measures of these social norms are needed to test this interpretation conclusively.

Little evidence was found for the role of the neighbourhood context. One would expect that ethnic diversity reduced the number of neighbourhood contacts, as the constrict hypothesis would suggest. There was the expected negative effect of diversity on natives’ contacts with neighbours, but it was in insignificant and small in magnitude. Previous studies in European countries also found weak evidence for the constrict hypothesis (van der Meer and Tolsma Citation2014). For migrants, one would have expected positive effects of diversity as a result of greater local contact opportunities but such effects could not be found either.

There are a number of implications of the present findings. Many studies have looked at how the neighbourhood context affects intra- and inter-ethnic relationships (Huijts, Kraaykamp, and Scheepers Citation2014; van der Meer and Tolsma Citation2014) whereas the focus in the current paper was on variation in the volume of local ties. These two are related but not the same and therefore need a separate treatment. When looking at contact volume, the evidence does not suggest that migrants on average are more isolated socially than natives. Some previous studies have shown that older Turks and Moroccans feel more lonely than natives, despite their higher levels of contact (van Tilburg and Fokkema Citation2021). The current study confirms, for a younger age group, that these migrant groups are actually better protected socially via their link to the neighbourhood. This finding is relevant in that the neighbourhood is a source of practical support and gives a sense of belonging that may be beneficial for mental health outcomes. Keep in mind, however, that there can be other forces such as health limitations and discrimination which counteract the positive effects of neighbourhood ties on the social wellbeing of migrants. In any event, it is clear that in analyses of intra- and inter-ethnic contacts, it is important to take into account variation in the volume of contact. Different descriptive foci will lead to different basic findings.

Another implication of the findings is that the family provides an important path to neighbourhood ties. Many neighbourhood studies have discussed theories about how intra- and inter-ethnic ties are formed in local settings but few of these have acknowledged the role of the family. Family ties will be correlated strongly with neighbourhood ties and they are by definition intra-ethnic ties. Even though there may be overlap in determinants, it is clear that family considerations cannot be ignored from such explanatory models. In their paper on social networks in the 1980s in Albany, NY, Logan and Spitze (Citation1994, 472) found evidence for the importance of what they called, ‘family neighbours’ and concluded that ‘urban sociologists … can benefit from a reconsideration of the extent to which local community networks are founded on kinship ties, even today’. The present analyses underlines the relevance of this observation for first- and second-generation migrants in a different country and for a more recent time period.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are publicly available at DANS-KNAW (www.dans-knaw.nl).

Notes

1 Based on my own calculations of the SIM2015 data from Statistics Netherlands. In the NELLS sample, respondents were younger (18–45) which should lead to even stronger effects of life course variables since there are also differences in the timing of marriage and fertility (Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek Citation2018).

2 A small group of native-born persons with parents who were born in a Western foreign country were also included (136). These were to a large extent children of mixed native-migrant marriages (66%).

References

- Aminzadeh, K., S. Denny, J. Utter, T. L. Milfont, S. Ameratunga, T. Teevale, and T. Clarke. 2013. “Neighbourhood Social Capital and Adolescent Self-Reported Wellbeing in New Zealand: A Multilevel Analysis.” Social Science & Medicine 84: 13–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.012.

- Barnes, S. L. 2003. “Determinants of Individual Neighborhood Ties and Social Resources in Poor Urban Neighborhoods.” Sociological Spectrum 23 (4): 463–497. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02732170309218.

- Beggs, J. J., V. A. Haines, and J. S. Hurlbert. 1996. “Revisiting the Rural-Urban Contrast: Personal Networks in Nonmetropolitan and Metropolitan Settings.” Rural Sociology 61 (2): 306–325. WOS:A1996VA66700006.

- Campbell, K. E., and B. A. Lee. 1992. “Sources of Personal Neighbor Networks - Social Integration, Need, or Time.” Social Forces 70 (4): 1077–1100. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2580202.

- Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2018. Jaarrapport Integratie 2018. s-Gravenhage: CBS.

- Chan, T. W., and J. Ermisch. 2015. “Residential Proximity of Parents and Their Adult Offspring in the United Kingdom, 2009-10.” Population Studies - A Journal of Demography 69 (3): 355–372. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2015.1107126.

- Chudnovskaya, M., and M. Kolk. 2017. “Educational Expansion and Intergenerational Proximity in Sweden.” Population Space and Place 23 (1): 14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1973.

- De Graaf, P. M., M. Kalmijn, G. Kraaykamp, and C. Monden. 2010. Design and content of the Netherlands Longitudinal Lifecourse Study (NELLS). Unpublished manuscript, Tilburg University & Radboud University Nijmegen, Netherlands.

- De Vries, J., M. Kalmijn, and A. C. Liefbroer. 2009. “Intergenerational Transmission of Kinship Norms? Evidence from Siblings in a Multi-Actor Survey.” Social Science Research 38 (1): 188–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.09.005.

- Dougherty, K. D., and M. T. Mulder. 2020. “Worshipping Local? Congregation Proximity, Attendance, and Neighborhood Commitment.” Review of Religious Research 62 (1): 27–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-019-00387-w.

- Fischer, C. S. 1982. To Dwell among Friends: Personal Networks in Town and City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Fischer, C. S. 2011. Still Connected: Family and Friends in America Since 1970. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Fong, E., and F. Hou. 2017. “Neighbours Helping Neighbours in Multi-Ethnic Context.” Population, Space and Place 23 (2): e1991. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1991.

- Gans, H. J. 1962. The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian Americans. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gans, D., M. Silverstein, and A. Lowenstein. 2009. “Do Religious Children Care More and Provide More Care for Older Parents? A Study of Filial Norms and Behaviors Across Five Nations.” Journal of Comparative Family Studies 40 (2): 187–201.

- Halman, L., and E. van Ingen. 2015. “Secularization and Changing Moral Views: European Trends in Church Attendance and Views on Homosexuality, Divorce, Abortion, and Euthanasia.” European Sociological Review 31 (5): 616–627. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv064.

- Huijts, T., G. Kraaykamp, and P. Scheepers. 2014. “Ethnic Diversity and Informal Intra- and Inter-Ethnic Contacts with Neighbours in The Netherlands: A Comparison of Natives and Ethnic Minorities.” Acta Sociologica 57 (1): 41–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699313504232.

- Intravia, J., E. A. Stewart, P. Y. Warren, and K. T. Wolff. 2016. “Neighborhood Disorder and Generalized Trust: A Multilevel Mediation Examination of Social Mechanisms.” Journal of Criminal Justice 46: 148–158. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2016.05.003.

- Kalmijn, M. 2006. “Educational Inequality and Family Relationships: Influences on Contact and Proximity.” European Sociological Review 22 (1): 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jci036.

- Kalmijn, M. 2012. “Longitudinal Analyses of the Effects of Age, Marriage, and Parenthood on Social Contacts and Support.” Advances in Life Course Research 17 (4): 177–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2012.08.002.

- Kalmijn, M., and W. Uunk. 2007. “Regional Value Differences in Europe and the Social Consequences of Divorce: A Test of the Stigmatization Hypothesis.” Social Science Research 36 (2): 447–468. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.06.001.

- Kemppainen, T., L. Kemppainen, H. Kuusio, S. Rask, and P. Saukkonen. 2020. “Multifocal Integration and Marginalisation: A Theoretical Model and an Empirical Study on Three Immigrant Groups.” Sociology – The Journal of the British Sociological Association 54 (4): 782–805.

- Khoudja, Y., and F. Fleischmann. 2017. “Labor Force Participation of Immigrant Women in the Netherlands: Do Traditional Partners Hold Them Back?” International Migration Review 51 (2): 506–541. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/imre.12228.

- Kinney, N. T., and W. E. Winter. 2006. “Places of Worship and Neighborhood Stability.” Journal of Urban Affairs 28 (4): 335–352. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2006.00299.x.

- Kohlbacher, J., U. Reeger, and P. Schnell. 2015. “Place Attachment and Social Ties - Migrants and Natives in Three Urban Settings in Vienna.” Population Space and Place 21 (5): 446–462. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.1923.

- Lancee, B., and J. Dronkers. 2011. “Ethnic, Religious and Economic Diversity in Dutch Neighbourhoods: Explaining Quality of Contact with Neighbours, Trust in the Neighbourhood and Inter-Ethnic Trust.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (4): 597–618. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2011.545277.

- Lenski, G. 1961. The Religious Factor: A Sociologist's Inquiry. Garden City: Doubleday.

- Logan, J. R., and G. Spitze. 1994. “Family Neighbors.” American Journal of Sociology 100: 453–476.

- Marsden, P. V. 1987. “Core Discussion Networks of Americans.” American Sociological Review 52: 122–131.

- Marsden, P. V. 1990. “Network Diversity, Substructures, and Opportunities for Contact.” In Structures of Power and Constraint, edited by C. Calhoun, M. W. Meyer, and W. Richard, 397–410. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mazzucato, V. 2015. “Transnational Families and the Well-Being of Children and Caregivers Who Stay in Origin Countries Introduction.” Social Science & Medicine 132: 208–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.030.

- McPherson, M., L. Smith-Lovin, and M. Brashears. 2006. “Social Isolation in America: Changes in Core Discussion Networks Over Two Decades.” American Sociological Review 71: 353–375.

- Mood, C. 2010. “Logistic Regression: Why We Cannot Do What We Think We Can Do, and What We Can Do About It.” European Sociological Review 26 (1): 67–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006.

- Moore, G. 1990. “Structural Determinants of Men's and Women's Personal Networks.” American Sociological Review 55: 726–735.

- Munch, A., J. Miller McPherson, and L. Smith-Lovin. 1997. “Gender, Children, and Social Contact: The Effects of Childrearing for men and Women.” American Sociological Review 62: 509–520.

- Norris, P., and R. F. Inglehart. 2012. “Muslim Integration into Western Cultures: Between Origins and Destinations.” Political Studies 60 (2): 228–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.00951.x.

- Peterie, M., G. Ramia, G. Marston, and R. Patulny. 2019. “Social Isolation as Stigma-Management: Explaining Long-Term Unemployed People's ‘Failure’ to Network.” Sociology - The Journal of the British Sociological Association 53 (6): 1043–1060.

- Pichler, F. 2012. “Cosmopolitanism in a Global Perspective: An International Comparison of Open-Minded Orientations and Identity in Relation to Globalization.” International Sociology 27 (1): 21–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580911422980.

- Portes, A., W. J. Haller, and L. E. Guarnizo. 2002. “Transnational Entrepreneurs: An Alternative Form of Immigrant Economic Adaptation.” American Sociological Review 67 (2): 278–298. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3088896.

- Putnam, R. D. 2007. “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the Twenty-First Century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture.” Scandinavian Political Studies 30 (2): 137–174. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x.

- Reyes, A., R. F. Schoeni, and H. Choi. 2020. “Race/Ethnic Differences in Spatial Distance Between Adult Children and Their Mothers.” Journal of Marriage and Family 82 (2): 810–821. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12614.

- Ross, C. E., and J. Mirowsky. 2009. “Neighborhood Disorder, Subjective Alienation, and Distress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 50 (1): 49–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650905000104.

- Rozer, J. J., A. R. Poortman, and G. Mollenhorst. 2017. “The Timing of Parenthood and Its Effect on Social Contact and Support.” Demographic Research 36: 1889–1916. doi:https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.36.62.

- Sampson, R. J. 1988. “Local Friendship Ties and Community Attachment in Mass Society: A Multilevel Systemic Model.” American Sociological Review 53 (5): 766–779.

- Sampson, R. J., J. D. Morenoff, and T. Gannon-Rowley. 2002. “Assessing “Neighborhood Effects": Social Processes and New Directions in Research.” Annual Review of Sociology 28: 443–478. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141114.

- Schröder, H., and H. B. G. Ganzeboom. 2014. “Measuring and Modelling Level of Education in European Societies.” European Sociological Review 30 (1): 119–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jct026.

- Shelton, N., and E. Grundy. 2000. “Proximity of Adult Children to Their Parents in Great Britain.” International Journal of Population Geography 6: 181–195.

- Silverstein, M., and V. L. Bengtson. 1997. “Intergenerational Solidarity and the Structure of Adult Child-Parent Relationships in American Families.” American Journal of Sociology 103: 429–460.

- Smith, S., I. Maas, and F. van Tubergen. 2012. “Irreconcilable Differences? Ethnic Intermarriage and Divorce in the Netherlands, 1995-2008.” Social Science Research 41 (5): 1126–1137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.02.004.

- Steinbach, A., K. Mahne, D. Klaus, and K. Hank. 2020. “Stability and Change in Intergenerational Family Relations Across Two Decades: Findings from the German Ageing Survey, 1996-2014.” Journals of Gerontology Series B - Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 75 (4): 899–906.

- Tolsma, J., and T. W. G. van der Meer. 2018. “Trust and Contact in Diverse Neighbourhoods: An Interplay of Four Ethnicity Effects.” Social Science Research 73: 92–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.04.003.

- Tolsma, J., T. van der Meer, and M. Gesthuizen. 2009. “The Impact of Neighbourhood and Municipality Characteristics on Social Cohesion in the Netherlands.” Acta Politica 44 (3): 286–313. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/ap.2009.6.

- van der Meer, T., and J. Tolsma. 2014. “Ethnic Diversity and Its Effects on Social Cohesion.” In Annual Review of Sociology, Vol. 40, 459, edited by K. S. Cook, and D. S. Massey. Palo Alto: Annual Reviews.

- van Maaren, F. M., and A. van de Rijt. 2020. “No Integration Paradox among Adolescents.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (9): 1756–1772. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183x.2018.1551126.

- van Tilburg, T. G., and T. Fokkema. 2021. “Stronger Feelings of Loneliness among Moroccan and Turkish Older Adults in the Netherlands: In Search for an Explanation.” European Journal of Ageing 18 (3): 311–322.

- Volker, B., and H. Flap. 2007. “Sixteen Million Neighbors - A Multilevel Study of the Role of Neighbors in the Personal Networks of the Dutch.” Urban Affairs Review 43 (2): 256–284. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087407302001.

- Volker, B., H. Flap, and S. Lindenberg. 2007. “When are Neighbourhoods Communities? Community in Dutch Neighbourhoods.” European Sociological Review 23 (1): 99–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jc1022.

- Wellman, B., and B. Leighton. 1979. “Networks, Neighborhoods, and Communities: Approaches to the Study of the Community Question.” Urban Affairs Review 14 (3): 363–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/107808747901400305.

- Wellman, B., and S. Wortley. 1990. “Different Strokes from Different Folks: Community Ties and Social Support.” American Journal of Sociology 96 (3): 558–588.

- Wessendorf, S., and J. Phillimore. 2019. “New Migrants’ Social Integration, Embedding and Emplacement in Superdiverse Contexts.” Sociology-the Journal of the British Sociological Association 53 (1): 123–138.

- Young, M., and P. Willmott. 1957. Family and Kinship in East London. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.