ABSTRACT

How people conceptualise their values can be distinguished regarding several characteristics: the awareness of one’s values, the relevance of values in one’s life, the stability throughout the life course, their overall consistency, their normative power, and validity for the self and others. This article aims to explore how value conceptualisations influence attitudes towards immigration. The relevance of this question stems from two research strands: first, immigration research has critically addressed that integration policies increasingly center around values. The value conceptualisation embedded in these policies is suggested to foster negativity towards immigrants. I ask, if therefore value conceptualisations help to estimate a person’s attitudes towards immigrations? Second, attitudes towards immigrants are known to be influenced by value priorities (such as universalism and tradition). Is this relationship of values and attitudes moderated by how a person conceptualises their values? Data from the Austrian Value Formation Survey (1.519 participants) is used to analyse multiple linear regression models. The results reveal both direct and moderating effects of value conceptualisations on attitudes towards immigrations. These findings indicate that the way we think about our values is important to our attitudes on social matters and the way our values shape these attitudes.

1. Introduction

In recent years, scholars have observed a shift in immigration policies around the world that introduce a new key rational for the inclusion and exclusion of immigrants. Previous rationales such as ethnicity, attempts to reverse demographic aging, and global competition for high-skilled workers are now accompanied by considerations of immigrant’s cultural knowledge and their adherence to national norms and customs (Bahry Citation2016; Djuve Citation2010; Fernandes Citation2002; Michalowski Citation2004). Immigrant groups are increasingly judged on whether or not their cultural and religious backgrounds match those of native populations (Alarian and Neureiter Citation2019; Battacharyya Citation2016; Larin Citation2020; Morrice Citation2017). In particular, the alleged threat of immigration for the value homogeneity within nation states is an increasing political concern. In several western countries, civic integration policies have been introduced, some of which demand immigrants to participate in value courses, or sign value contracts (Larin Citation2020; McPherson Citation2010).

The increasing literature on this topic critiques the way values are conceptualised within these policies. For example, one implicit notion is that shared national values and cultural homogeneity are supposedly necessary to ensure the peace and order inside of nation states (Battacharyya Citation2016; Fritzsche Citation2016; Mensing Citation2016). Other critiqued ideas include that values are homogenous within national populations (Castels et al. Citation2002), that globally relevant achievements result from particular national histories, or the unquestionable superiority of certain beliefs above others (Larin Citation2020). Studies also show that these narratives disempower and exclude immigrants (Fernandes Citation2002; Khan Citation2013; Tyler Citation2010) and reduce the openness of receiving societies (Castels et al. Citation2002; King and Skeldon Citation2010). Therefore, the effects of these policies on the majority populations are of interest. Recent public opinion polls in Germany and Austria show that adherence to national values is an important factor for the population's acceptance of immigrants and refugees (Bretschneider and Austria Citation2017; Ditlmann et al. Citation2016). One consequence from these national policies seems to be a rising importance of values in the minds of native populations, when immigration is concerned.

The key role of values for attitudes on immigration is also highlighted in another research branch. Multiple international studies have found that attitudes towards immigration are influenced by one’s own value priorities (Beierlein, Kuntz, and Davidov Citation2016; Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012; Davidov et al. Citation2008; Davidov et al. Citation2014; Davidov et al. Citation2020; Eisentraut Citation2019; Goren et al. Citation2016; Ponizovskiy Citation2016; Vecchione et al. Citation2012). These studies find that value priorities explain attitudes towards immigration over and above sociodemographic predictors (Davidov et al. Citation2014, 265). The effect is also consistent in different countries (Davidov et al. Citation2020, 554) and has been confirmed in longitudinal studies (Eisentraut Citation2019). Therefore, value priorities are indeed an important factor in contemporary immigration politics. They are an important predictor of attitudes towards immigration within the host societies.

The following article tries to connect these findings, by asking how value conceptualisation affects attitudes towards immigration. Value conceptualisation is understood as the characteristics attributed to one’s values. Following Seewann and Verwiebe (Citation2020), I distinguish six such characteristic dimensions: value awareness, value relevance, value stability, value consistency, value normativity and value validity. Seewann and Verwiebe (Citation2020) show that people vary significantly in these dimensions. Given the example of value normativity, some people believe that the right values vary between people and understand values as subjective (low value normativity); while others attribute a universal normative power to values and claim that some values are objectively right (high value normativity). This article asks if conceptualisations, such as value normativity, influence attitudes on social matters. Seeing one’s own values as universal guidelines might foster negative attitudes towards immigrants, if they are perceived to hold different worldviews. I first investigate these direct effects of value conceptualisation on attitudes towards immigrants. Second, I ask, if value conceptualisations and value priorities interact in their relations to attitudes, thus forming a moderation. Taking the example of value normativity again, in those people that think their values are objectively right, values might have a stronger correlation with their attitudes than compared with people that see values as subjective. Or respectively: Depending on the importance of one’s values (e.g. universalism, tradition), value normativity might have a different effect on attitudes towards immigration.

These assumptions are tested using the Austrian Value Formation Survey (ÖWBS Citation2016) for secondary analysis. This survey data provides opinions on immigration and values by 1.519 Austrian citizens between the ages of 15 and 69 years. It was collected in Austria in 2016 via an online questionnaire. The sample is representative of the Austrian population in regards to age, gender, federal state and highest education level. The use of a national sample does not imply that the effects found are assumed to be specific to Austria. However, the country poses a good case study since political value debates are prominent, especially since 2015 when compulsory value courses for new immigrants were adopted (e.g. BMEIA Citation2015; Bretschneider and Austria Citation2017). Moreover, Austria has seen a significant growth in the share of population with foreign nationalities, from 9% in 2004 to 14% in 2016, a year when the country also accepted a large number of Syrian refugees (Verwiebe, Seewann, and Wolf Citation2018).Footnote1 The country is also featured in many previous studies on the relevance of values for immigration attitudes, most of which use the European Social Survey (e.g. Davidov and Meuleman Citation2012; Davidov et al. Citation2008; Davidov et al. Citation2020).

The ÖWBS includes the newly developed value conceptualisation scale (Seewann and Verwiebe Citation2020), as well as the Schwartz’s Portrait Values Questionnaire (Citation2012) and an index measuring the realistic and symbolic threat of immigration (ESS 7 Citation2014). Multiple linear regression models are used to explore if value conceptualisations help to explain variety in attitudes on immigration. The article at hand provides the first empirical insights into the role of value conceptualisation for immigration. It aims to include findings and insights from scholars of value research, as well as immigration research, which will be presented in the following section.

2. State of research and hypotheses

2.1. Value conceptualisation

In this article, the term value conceptualisation will be used to address the characteristics that people ascribe to their values. This means that aside from their content (e.g. hereinafter specifically universalism and tradition), values in general are experienced in different ways. Although this topic is not studied broadly yet, in recent years, several studies have explored how values are conceptualised, which I will summarise shortly: Malle and Edmondson (Citation2004) provide a conceptual study by examining lay definitions of the value concept of 324 students in the United States. The students' descriptions of values varied (see Malle and Edmondson Citation2004, 25f), for example whether values ‘can range from person to person’ and are ‘very personal’, or on the other hand ‘set ideals’ and ‘sacred’, marking differences in normative views on values.Footnote2 Similar qualitative studies have confirmed that even in rather homogenous groups (often students, managers or educators), considerable differences in value conceptualisation can be found (Branson Citation2004; Flowers Citation2002; Mashlah Citation2015; Zupan Citation2012). Flowers (Citation2002) has conducted one of the more diverse studies with people of different socio-economic, educational and family characteristics in Australia. She identifies ‘diverse interpretations of the term “values”’ (Flowers Citation2002, 11), as well as differing levels of self-reflection on values among participants. Köbel (Citation2018, 239) depicts contrasting experiences of values as long-lasting, or formed by sudden dramatic changes in Germany. Klages (Citation2001) theory of a value synthesis argued for the idea that some people value seemingly contradictory values (‘active realists’) while others related to no values at all (‘resigned without perspective’), a finding that sparked much debate (Klages and Gensicke Citation2006; Roßteutscher Citation2004, Citation2005; Thome Citation2004). Social psychology reflects on differences in value awareness under the term ‘metacognition’, meaning the ability of people to talk about their value priorities (Rohan Citation2000, 267f). Even Schwartz (Citation2009, 225) hints towards differences in value conceptualisation, for instance, when he discusses how some people pursue competing or contravening values, implying that other people may be more consistent in their beliefs.

No theoretic framework of value conceptualisations exists today. However, Seewann and Verwiebe (Citation2020) have recently provided a systematic study of value conceptualisations using a mixed methods approach. Seven focus group interviews (n = 38) with people of different age, gender and occupations were conducted to collect statements on values. Through classification, the authors distinguished six dimensions in which people’s conceptualisation of values vary:

The dimensions are value normativity (values are seen as applying only to oneself or all humans), value relevance (how often values are referred to in everyday situations), value validity (degree of acceptance for dictating values to others), value stability (previously experienced value changes), value consistency (perceived contradiction or coherence of one’s values), and value awareness (ability to express or explicitly think about values). (Seewann and Verwiebe Citation2020, 428)

2.2. Effects on attitudes towards immigration

2.2.1. Direct effects

The following section argues that value conceptualisations affect attitudes towards immigration by drawing on research of contemporary immigration policies in Europe. Values are currently present in the political discourse on immigration in many countries. In 2004, the European Justice and Home affairs council advocated for promoting ‘respect for the basic values of the European Union’ (EU Citation2014, 19) through courses, contracts and tests (Alarian and Neureiter Citation2019). Many states such as France, Denmark, UK, Sweden, Norway, Germany and Austria have since introduced mandatory trainings or contracts to adhere to national values for immigrants (Barry and Sorensen Citation2018; BMEIA Citation2015; Civic Integration Act Citation2006; Edenborg Citation2020; Elton-Chalcraft et al. Citation2017; Fernandes Citation2002; Integrationskursverordnung Citation2004; Larin Citation2020, 130). The existing literature (Alarian and Neureiter Citation2019; Fernandes Citation2002; Larin Citation2020; Mensing Citation2016; Morrice Citation2017) shows a connection between the conceptualisation of values within these discussions to negative images of immigrants. This study aims to test, if people that conceptualise values in this way, also hold negative attitudes towards immigration.

First, these political discussions stress the need to formulate explicit values and raise awareness of these values in the population. One example of this view is highlighted by Tyler, who quotes Prime Minister Gordon Brown in 2008:

… we may lose out if we prove slow to express (…) the British values that can move us to act together (…) Being more explicit about what it means to be a British citizen we can not only manage immigration in a way that is good for Britain (…) but at the same time move forward as a more confident Britain. (Tyler Citation2010, 64)

Tyler (Citation2010, 64f) argues that this conceptualisation of values reinforces the idea that non-citizens threaten to overwhelm the country, unless the population is made aware of core values and confidently enforces them. These policies also underline the relevance of values for everyday life and assert that shared values are ‘the basis of living together’ (e.g. BMEIA Citation2015; Tyler Citation2010). Multiple scholars offer an extensive criticism of this view (Castels et al. Citation2002, 147; Morrice Citation2017, 401; e.g. Norman Citation1995, 147). However, the narrative suggests that value awareness (H1a) and value relevance (H1b) might be more important to those that view immigration as a threat, while those open to immigration might put less importance on values (see for proposed hypothesis).

Second, these political discussions frame values to be the outcome of distinct national histories and long-lived circumstances (Mouritsen Citation2008, 23), and therefore as stable concepts within homogenous societies, overlooking that these principles ‘are equally resonant across many national boundaries’ (Larin Citation2020, 132). Immigrants on the other hand, are ‘tied irretrievably to backwards, violent and exclusionary values’ (Battacharyya Citation2016, 2). Several scholars critique this implicit notion that ‘nation states have settled collective and stable values and identities; that values (…) have a single shared meaning’ (Morrice Citation2017, 400) and that these shared values are under threat by immigrants (see also Alarian and Neureiter Citation2019; Castels et al. Citation2002; Dietze Citation2009). However, we might find that people that view values as more stable (H1c) and consistent (H1d) also hold more negative views on immigration, while people open to immigration address the changing and contradictory nature of their own beliefs.

Third, scholars find that immigrants are labeled as unfit or undeserving to participate in the culture of the receiving society (Larin Citation2020, 138; Zetter Citation2007). In a study comparing Sweden, Denmark and Norway, Fernandes (Citation2002, 253) found that introduction programms expressed a paternalistic understanding, in which immigrants were characterised by lacking competences, and mandatory participation in courses had to ensure the internalisation of ‘basic’ norms and values. For example, the 2015 Austrian pamphlet on mandatory ‘orientation and value courses’ reads: ‘They are to learn what society expects from them and what is not negotiable in order to enable peaceful coexistence of all people in Austria’ (BMEIA Citation2015, 14). In Denmark discussions on the ‘Dutch newcomers Integration Act’ recently made headlines

for the requirement that “low-income immigrant ghetto” children age one and older be separated from their families for at least 25 h per week for instructions in “Danish values” backed by the threat that the state may stop welfare payments if parents do not comply. (Barry and Sorensen Citation2018; Civic Integration Act Citation2006; Larin Citation2020, 130)

2.2.2. Moderation effects

Aside from directly relating to attitudes towards immigration, value conceptualisations might also form an interaction with value priorities. Value priorities address the relative importance that people place on specific goals, ideals and beliefs in their life. For example, Schwartz’s theory of human values (Schwartz Citation2012) distinguishes ten universally acknowledged values – such as self-direction, universalism and tradition. These values form specific relationships with each other: pursuing self-direction might be congruent to universalism, but in conflict with traditional values. Although a variety of competing classifications of value priorities exist (Halman, Sieben, and van Zundert Citation2011; Inglehart Citation1997; Klages Citation2001; Rokeach Citation1973; Vernon and Allport Citation1931), there is an agreement in the literature that the priority people place on one value over other values is important and helps to explain differences in attitudes. In the following, I will focus on universalism and tradition, two value priorities with distinctly different motivational goals. According to Schwartz’s refined theory of values universalism entails ‘understanding, appreciation, tolerance and protection for the welfare of all people and for nature’, while tradition is defined as ‘respect, commitment and acceptance of the customs and ideas that traditional culture or religion provides’ (Schwartz et al. Citation2012, 664).

Multiple studies have identified universalism and tradition as a key predictor of negative attitudes towards immigration (Beierlein et al., Citation2016; Davidov & Meuleman, Citation2012; Davidov et al., Citation2008; Davidov et al., Citation2014; Davidov et al., Citation2020; Eisentraut, Citation2019; Goren et al., Citation2016; Ponizovskiy, Citation2016; Vecchione et al., Citation2012), next to other factors such as education (Coenders & Scheepers, Citation2003), perceived threat (Schneider, Citation2008), relative deprivation (Grant, Citation2008), and racial prejudice (Akrami et al., Citation2000). Using the European Social Survey and Schwartz’s Portrait Values Questionnaire (Citation2012), researchers find that ‘individual differences in values explain negative attitudes towards immigration over and above the effects of social structural position’ (Davidov et al., Citation2014, 265). More precisely, universalism is a strong predictor of favourable attitudes towards immigration. Tradition on the other hand has been linked to a negative view on immigrants (Davidov et al., Citation2014; Vecchione et al., Citation2012). In their most recent study, Davidov et al. (Citation2020) provided evidence for this relationship in 21 European countries (as well as Israel).

This study asks if the effects of value priorities and value conceptualisations on attitudes towards immigration are dependent on each other. It is plausible that people are more likely to hold attitudes that are consistent with universalism/tradition if values are perceived to be clear, compelling, important and relevant (similar to the concept of attitude strength, see Howe & Krosnick, Citation2017, 328f). Methodically, such an interaction can also be understood the other way around: the direct effect of value conceptualisations on attitudes towards immigration might depend on the level to which universalism/tradition is important to a person.Footnote3

More specifically, (H2a) in people that claim to be highly aware of their values, and (H2b) in those that see values as highly relevant in their life, tradition might have a more negative, universalism a more positive relationship with attitudes on immigration. Research on moral metacognition suggests that ethical decision making can take place with varying levels of cognition, relying more or less on rational thought or intuition (McMahon & Good, Citation2016, 3f). Values that are conceived as relevant and aware might guide attitude formation. Conversely, those people that find it difficult to describe their values (low awareness), or see them as having little meaning in their life (low relevance) are likely not forming their attitudes based on values. Contemporary scholars such as Schwartz also resonate this idea that only ‘activated’ values shape attitudes and actions: ‘Values affect behavior only if they are activated and if, at some level of awareness, they are experienced as relevant’ (Citation2009, 230).

Similarly, the more stable (H2c) and consistent (H2d) one’s values are perceived, the more negative the relationship of tradition to attitudes, and the more positive the relationship of universalism to attitudes likely is. People who experience their values as contradictory or unstable are characterised as problematic throughout the literature on values (e.g. Roßteutscher, Citation2004, 410). Helmut Klages (Citation2001, 10) calls them the ‘resigned’ and describes them as ‘stepchildren of social change’ who are passive, apathetic and withdrawn from society. Kluckhohn states that without a clear value system ‘individuals could not get what they want and need from other individuals in personal and emotional terms nor could they feel within themselves the requisite measure of order and unified purpose’ (Kluckhohn, Citation1951, 400). Several scholars suggest that consistency needs motivate our understanding of values and their effect on attitudes and behaviors (Bardi & Schwartz, Citation2003; Boer & Fischer, Citation2013, 5f). In line with this argument, it is likely that perceiving one’s values as unstable or contradictory lessens their relationship with the attitudes a person holds.

Finally, I argue that the more values are understood as normative (H2e) and valid (H2f) for other people, the more negative the relationship of tradition, and the more positive the relationship of universalism and attitudes towards immigration. If values are seen to have normative power, they become not only a matter of subjective beliefs but are also relevant in judging and sanctioning others. In such a view, values are integral to the social fabric and interactions with other people (e.g. Hofstede, Citation2001; Rohan, Citation2000). This moderation might be particularly reasonable because attitudes towards immigration are concerned, which raise questions of belonging, loyalty and group identification (Alarian & Neureiter, Citation2019; Davidov & Meuleman, Citation2012; Vecchione et al., Citation2012).

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Data

To test the proposed hypotheses, I utilise data from the Austrian Value Formation Survey (ÖWBS, Citation2016) for secondary analysis. The survey was collected in July 2016, with the help of a market research firm. It was carried out via an online panel and participation was incentivised by an internal reward system. The total sample consists of 1519 participants. It is representative for the Austrian population between 15 and 69 years of age, with special regard to age, gender, federal state and education level (±5%). compares the demographics of this sample to the Austrian Microcensus 2015. It also provides information on the share of participants with an immigration background, which resembles the microcensus, except for first-generation participants which are underrepresented. Despite this limitation, the data set provides a unique opportunity for this exploratory study because it includes items used in previous research, as well as the newly developed value conceptualisation scale, which will be described in the following section.

3.2. Variables

Values were measured using the 21-item portrait values questionnaire (Schwartz, Citation2012).Footnote4 Schwartz’s human value theory distinguishes 10 universal values (universalism, benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation and self-direction). They are measured by presenting participants with 21 gender-matched portraits that describe goals and aspirations linked to each value. Participants then rate how similar they are to the person described on a six-point scale (1 very much like me, 2 like me, 3 somewhat like me, 4 somewhat not like me, 5 not like me, 6 not like me at all). The following analysis focuses only on the values universalism (UN) and tradition (TR) because they correlate strongly with attitudes towards immigration in previous studies (e.g. Davidov et al., Citation2014; Davidov et al., Citation2020; Eisentraut, Citation2019; Vecchione et al., Citation2012). The items measuring universalism ask the importance of treating every person in the world equally, as well as listening to and understanding people who are different. The item that concerns looking after the environment was excluded in this study. It was shown to lack validity (Knoppen & Saris, Citation2009; Schwartz et al., Citation2012) and is excluded in similar studies (Davidov et al., Citation2020; Eisentraut, Citation2019). The questions on tradition ask if following customs handed down by religion or family and being humble and modest is important.

To measure attitudes towards immigration respondents were asked three questions about the realistic and symbolic threat by immigrants: (1) ‘Would you say that generally cultural life in Austria is rather undermined or rather enriched by immigrants?’; (2) ‘Would you say that immigrants that come to Austria generally take jobs away from Austrian workers or contribute to the creation of new jobs?’; and (3) ‘Most immigrants that come to Austria work and pay taxes. They also utilise health and social benefits. In general, do you think immigrants that come to Austria take more than they contribute or contribute more than they pay’. Responses ranged from 0 to 10 on an 11-point scale, with positive statements towards immigration at the 10-point mark. For analyses, these questions were averaged in an index (further labelled IMI), after they loaded positively and highly on a single factor (ranging from .78 to .81) in a confirmatory factor analysis.

Value conceptualisation was measured using 6-point bipolar items (see ). Each item corresponds to a different dimension of value conceptualisation. Participants are asked to locate their own views on values between two statements on each dimension. For example, high value normativity is indicated by the statement ‘There are values that are objectively right and apply to everyone’ while the low value normativity statement reads ‘Which values are right, differs from person to person’. A full description of the question wording is given in (see Chapter 2.1). Seewann and Verwiebe (Citation2020) have provided initial evaluation of this newly developed scale and have found good variance and test–retest reliability, as well as convergent validity of corresponding items with dogmatism, preference for consistency and moral metacognition. To prepare the data for analysis, all value conceptualisation variables were recoded, so that higher item scores indicate stronger corresponding phenomena (normativity, stability, etc.) on all dimensions.

Table 1. Measurement of the six value conceptualisation dimensions.

Table 2. Demographics of ÖWBS sample.

Several control variables were added to exclude confounding effects. Gender was scored 0 for men and 1 for women. Literature shows that gender seldomly correlates significantly with value priorities (e.g. Davidov et al., Citation2014; Schwartz & Rubel, Citation2005), but women tend to show more empathy for immigrants (e.g. Chao et al., Citation2015). Age is measured in years and has shown to correlate negatively with perceptions of immigrants (e.g. Davidov et al., Citation2014; Vecchione et al., Citation2012). Education refers to the highest formal education level, which was recoded into two binary variables: one for secondary education (vocational training, apprenticeship, secondary schooling) and one for tertiary education (University or technical college), with compulsory education (or below) as a reference group. Education correlates positively with attitudes towards immigration in existing studies (e.g. Beierlein et al., Citation2016; Davidov et al., Citation2014; Vecchione et al., Citation2012).

3.3. Missing data

Owing to the incentivised panel used to collect this data by the market research firm, only completely filled out surveys are included in the ÖWBS. Unfortunately, no information on the response rate is available, which presents a limitation. The only cases of missing data included in the ÖWBS are ‘Don’t know’ answers to the survey questions. In regards to the variables used in this study, only a limited number of participants chose to answer in this way: universalism (0 cases), tradition (12 cases), six-value conceptualisation dimensions (0 cases), gender (0 cases), age (0 cases) and education (16 cases). These 26 cases were deleted. The dependent variable, measuring attitudes towards immigration on a three-item scale, also included several ‘Don’t know’ answers (178 cases where at least one of three items’ answers were missing). An effort was made to impute these answers, to preserve a large sample for the analysis and avoid a bias in the estimates. Based on the works of Kroh (Citation2006) I argue that ‘don’t know’ answers regarding immigration attitudes should not be treated as refusals. It cannot be assumed that a valid answer was withheld, rather than the respondent truly not knowing how to answer the question. Imputation methods that replace scores on the related variable would then result in a misspecification bias (Kroh, Citation2006, 228). Therefore, a multiple complete random imputation method (Kroh, Citation2006) was chosen to replace ‘don’t know’ answers. The sample size at this point included 1491 cases.

3.4. Analysis

To explore the relationship between value conceptualisation, value priorities and attitudes, I estimated a series of 12 hierarchical linear regression models in a build-up process (Cohen et al., Citation2003, 210). In preparation for the analysis, several steps were taken to visually explore the data and check the model assumptions. Frequency histograms and boxplots revealed several outliers in the universalism and tradition variable. Bivariate displays showed strong linear relationships of the attitudes towards immigration index to universalism and tradition and a slight curvilinear relationship to the value conceptualisation dimensionsFootnote5 - thus calling for the inclusion of power polynomials. The correlation matrix suggested a linear relationship of attitudes towards immigration to universalism (.31***) and tradition (−.09***) in the sample, as well as education (.20***), value validity (−.08**) and value consistency (−.06*). There was also significant correlation between universalism and tradition to several value conceptualisation dimensions - the highest being value relevance (universalism: .14***, tradition: .23***).

A preliminary examination of the regression models compared the models in terms of statistical power, significance levels, effect sizes, as well as theoretical rational. The constant variance, independence, and normality of residuals for these models were tested. Again, no problems were detected except a few outliers. Using Mahalanobis distance, leverage size and Cook’s distance, outliers that failed two of these three criterions where excluded (46 responses). Finally, the continuous variables in the model (age, universalism, tradition, all six-value conceptualisation dimensions, as well as their polynomials) were mean-centred to reduce multicollinearity issues and ease interpretation of the interactions.

The final analysis undertakes the following steps: the base model (1) includes the sociodemographic control variables. Model 2 introduces the direct effects of the value priorities for universalism and tradition. Model 3 includes the direct effects of all six dimensions of value conceptualisation. Models 4–9 introduce the six dimensions separately, but include power polynomials for each dimension of value conceptualisation. This strategy was chosen because visual examination revealed a curvilinear relationship in the residual scatterplots and lowess curves. Model 10 combines the direct and polynomial effect of all six dimensions of value conceptualisation into one model. Model 11 includes interaction terms between the main value conceptualisation effects and universalism, as well as tradition (only significant effects are included in ). Model 12 finally includes the interaction terms between polynomials of value conceptualisation and both values (universalism and tradition).

4. Results

provides descriptive statistics of the items used to measure value priorities, attitudes towards immigration and value conceptualisation. The data shows that attitudes towards immigration vary within the sample, with a slight skew towards negative views on immigrants. The following sections will try to explain part of this variance by focusing on values and value conceptualisations as contributing factors. In terms of value conceptualisation, shows that a majority of the Austrian population claim to be aware of their own values and considers values to be highly relevant and consistent. Value stability, normativity and validity are more normally distributed, with slight majorities in terms of unstable, normative values, with low validity.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of all uncentered items for the total sample.

Table 4. Regression models predicting attitudes towards immigration (IMI).

Table 5. Summary of predictions.

The results of the regression analysis first start with the base models 1 (see ), regressing the attitudes towards immigration on the sociodemographic variables. These variables explain about 2 percent of the variance in attitudes towards immigration (Adj R² .02). Tertiary education shows a strong positive effect towards immigration attitudes in the base model and all following models. Therefore, highly educated people hold more positive attitudes towards immigration. Age shows a slight negative effect in this first model, indicating that younger participants were more open to immigration. No significant difference in the attitudes of men and women could be detected. These results match those observed in previous studies (Vecchione et al. Citation2012, Davidov et al. Citation2014, Davidov et al. Citation2020).

Model 2 includes the main effect of universalism and tradition (see ). The introduction of those value priorities increases the explained variance to 14 (Adj R² .141). A highly significant positive effect suggests that universal values lead to more positive attitudes towards immigration. Traditional values on the other hand affect attitudes towards immigration negatively in all models. These results confirm those of previous studies, who also found that values can explain attitudes towards immigration over and above sociodemographic variables (e.g. Davidov et al., Citation2008).

Model 3 introduces all six dimensions of value conceptualisation (see ). The direct effects of these dimensions slightly increase the explained variance to 15 percent (Adj R² .149). Only two dimensions show a significant relationship. Value relevance portrays a negative effect (−.140*) meaning people that consider their values more relevant hold more negative attitudes towards immigration. Value normativity is positively related to attitudes towards immigration (.123**), suggesting that people that consider some values objectively right have a more positive attitude towards immigration.

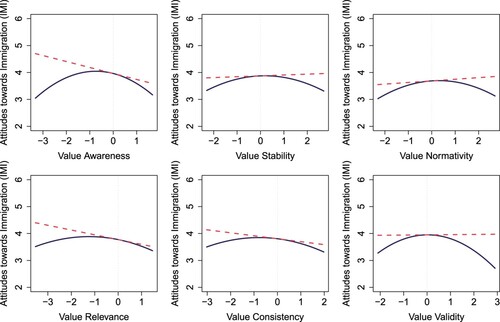

Models 4–9 present separate models for each value conceptualisation dimension and its squared polynomial. Since the value conceptualisation items present different dimensions, it is likely that they form complex relationships with one another. To understand the effects of each dimension on attitudes towards immigration, they will be discussed separately in the following pages. also gives a graphical representation of these effects.

Figure 1. Graphical comparison of the relationships of the six-value conceptualisation dimensions to attitudes towards immigration (Models 4−9).Note: Dotted lines signify the direct linear effects; solid lines the combined direct and squared effects.

Value awareness shows both a negative linear, as well as inverted u-shaped relation to attitudes towards immigration in model 4 (see and ). Assuming all other variables to take average or reference category values (e.g. a 42-year-old man with compulsory education and an average agreement to universal and tradition values), as one’s perceived awareness of values increases, attitudes towards immigration tend to get more negative (−.222***) but only after an initial bump (−.150**) at slightly below average awareness (mean 4.3, see for means before centring). This means that people that state ‘I find it difficult to describe my values’ as well as people agreeing strongly to being ‘clearly aware of their values’ have the most negative views on immigration. This relation stays present in models 10–12 when other dimensions of value conceptualisation and interaction terms are included. These variables also considerably increase the explained variability to 15.7 percent. When the curvilinear component is accounted for, H1a is supported by the data, however no moderation effect (H2a) could be found.

Value relevance portrays a similar pattern. In model 5 we find a significant negative linear effect (−.177**), as well as inverted u-shaped relation (−.071*) to attitudes towards immigration. This suggests that at average value relevance (mean 4.5), people hold the most positive attitudes towards immigrants. Stating that values have ‘little meaning in everyday life’ or strongly agreeing to values being ‘very important in my everyday life’ is related to more negative attitudes. The effect loses significance when other value conceptualisation dimensions are added into the models (10−12). H1a can therefore only be considered partly supported, and further research is need to understand the relationship between value relevance and other value conceptualisation dimensions. However, these results support the idea that the perception of values as conscious and important themselves are related to anti-immigrant sentiments, regardless of the values held by the participants (Morrice, Citation2017; Tyler, Citation2010).

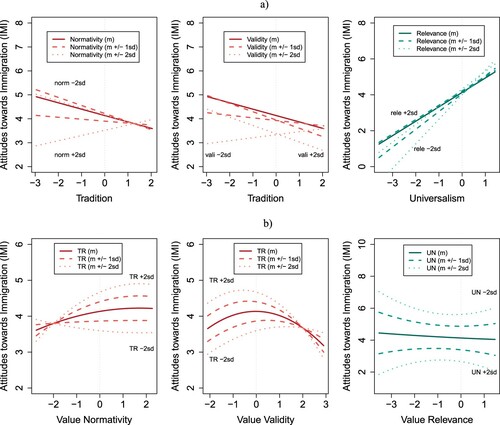

Another interesting finding is an interaction between universalism and the squared value relevance (.72+) in model 12. Although this term only portrays significance on a .1 level, it suggests that the relationship between value relevance’s curvilinear component and immigration attitudes is moderated by universalism (see ). Such a relationship has to be intepreted with care because polynomial interactions are seldom supported by theory and demand great statistical power to be detected (Cohen et al., Citation2003, 384). Two interpretations are plausible: on one hand, high value relevance leads to a more positive relationship of universalism to attitudes towards immigration (a), thus supporting H2b. On the other hand, the curvature of the relationship between value relevance and attitudes towards immigration is different for different levels of universalism values (see b). More specificly, the more a person agrees to universalism value (see UN-sd in b), the more u-shaped the curvature of the relationship gets. In return, the less importance people place on universalism, the more inverted the u-shape becomes (see UN + sd in b) In other words, positive attitudes towards immigration are found in people that highly value universalism but think values are irrelevant or significantly more relevant than the average population.

Figure 2. Simple slopes showing the moderating effect (model 12). (a) Depicting value conceptualisations moderating the association between tradition/universalism and attitudes. (b) Depicting tradition/universalism moderating the association between value conceptualisations and attitudes.

Value stability shows no significant direct linear effect to attitudes towards immigration, contrary to H1c. The data also shows no moderation effect, therefore not supporting hypotheses H2c. Only a slightly significant curvilinear relation can be observed in model 8 (−.089**). This suggest that both highly stable and highly changeable values lead to more negative views on immigrants (see ). One might conclude that both dramatic changes as well as very consistent values intensify the relationship with one’s values, as Köbel qualitative study (Citation2018) exemplifies. Perceiving moderate value stability might hint toward an indifference to the topic in this case that ties into an indifference about immigrants and the respective value changes they might bring (e.g. Dietze, Citation2009; Mouritsen, Citation2008).

Value consistency shows a negative linear relationship to attitudes towards immigration (−.110*) as well as inverted u-shaped relation (−.070*) in model 7. This suggests that above and below mean value consistency (4.02) attitudes towards immigration get more negative. Those that feel that values are ‘contradictory and hard to implement’, as well as those that strongly feel that values are ‘clear guidelines of how to live their life’ feel negatively towards immigration. The findings are overall in congruency with H1d. They also support the claim that emphasizing certainty in one’s values aligns with feeling threatened by immigrants, while claiming uncertainty reduces the perceptions of competition (Tyler, Citation2010). In opposition to H2d no statistically significant moderation effect could be detected. Therefore, besides its direct effect on attitudes towards immigration, an influence on the value attitude relationship is not supported by the data. The effects are not significant when other dimensions of value conceptualisation are included in the models, which warrants further research on the internal relationships of the value conceptualisation dimensions.

The models including value normativity show a different result. When both the direct effect (.060) and curvilinear effect (−.099***) are introduced in model 8, only the latter is significant. This suggests that value normativity holds an inverted u-shaped relationship with attitudes towards immigration, similar to value stability. However, in model 3 as well as model 10−12, when other dimensions are introduced, only the linear effect shows a slight significance (at .104* to .123** depending on the model). This indicates that the more a person agrees that ‘there are values that are objectively right and apply to everyone’ the more positive their attitude towards immigration. Likewise, people that agree ‘which values are right differs from person to person’ show more negative attitudes. In reference to the literature on values and multiculturalism this finding is rather interesting. Scholars such as Battacharyya (Citation2016) state that reassertions of majority values as the glue to social order, serve ‘as both the respectable compromise that allows diversity within the limits of shared key values and an element of more strident protests against the impact of multiculturalism’ (Battacharyya, Citation2016, 18), therefore trying to balance normative and subjective views on values. My results run against this observation, as well as my proposed hypothesis (H1e) and would suggest that commitment to objective values is connected to a more positive view on immigration.

Furthermore, models 11 and 12 find a significant moderation effect between value normativity and tradition. The negative moderation effect (−.091 and −.084) is significant only on a .05 level. It suggests that when values are considered highly normative, traditional values form a negative relationship with immigration attitudes (see a). While seeing values as subjective (low normativity, norm+2sd), the more important tradition is considered, the more positive the attitudes towards immigration. In other words, people that do not value tradition, but think that there are values that are objectively right, are the ones with the most positive attitudes towards immigration. As mentioned before, caution is advised in interpreting these results, due to the low levels of significance.

Finally, value validity shows a non-significant linear effect throughout the models, as well as an inverted u-shaped relation to attitudes towards immigration (see ). The results suggest that people who state ‘You have to guide people towards the right way’ and people who agree that ‘nobody should dictate values to others’ have more negative attitudes towards immigrant than people with average value validity (mean 3.1). This finding does not support H1f and contrasts much of the literature on value policies that suggest the ideas of value courses or guidance resonates with anti-immigrant sentiments (Fritzsche, Citation2016; Joppke, Citation2007; Mensing, Citation2016). Instead, it seems that both strong opposition and support for guiding others towards the right values is present in people holding negative attitudes towards immigrants.

Interestingly, models 11 and 12 also include a nearly significant (.1 level) moderation effect with tradition on the main effect (.088+). This result suggests that value validity moderates the effect of tradition on attitudes towards immigration (a). When people consider their values highly valid (others should be guided), tradition increases positive attitudes towards immigration. While with low validity (nobody can dictate values), the more traditional the more negative these attitudes get.Footnote6 Therefore, those that do not value tradition and think nobody is allowed to dictate values to others are most positive when it comes to immigration. This finding – although suggesting a moderation – is in direct opposition to H2f, but again, caution is advised because these effects are not significant above a .1 threshold.

The discussed moderation effects have some interesting implications for the complex dynamics that form attitudes towards immigration. However, the inclusion of interactions in models 11 and 12 only increase the explained variance in attitudes towards immigration slightly. Therefore model 10 including only direct effects (and explaining 17 percent of the variance) should be the focal point of discussion and future insights into these relationships.

5. Summary and discussion

Immigration has increased since the turn of the century, and is one of the most prominent political topics in Europe. Immigrants are often met with negative public attitudes, increasing integration demands, and sometimes confrontational political discourses. New to these discourses is a focus on beliefs and values. More precisely, European policies have embraced an understanding of values as a homogenous social glue within western societies that is under threat by immigrants and the harmful values they bring with them.

This study introduced the concept of value conceptualisation, to gain a more detailed understanding of the connection between values and attitudes towards immigration. In recent years, immigration research addressed the inherent value conceptualisation embedded within civic integration policies in Europe and their connection to a negative portrayal of immigrants. The present study asked whether certain value conceptualisations also align with negative attitudes towards immigrants within the general population. The large body of literature on values already shows, that prioritizing universalism increases positive attitudes towards immigration, while traditional values foster negativity. Furthermore, I aimed to examine moderations in this relationship, depending on whether or not values in general are perceived as aware, relevant, stable, consistent, normative and valid.

The results can be summarised in the following way: The most positive attitudes towards immigration are found in academically educated and young people, who place large importance on universal values but also in those that perceive values as difficult to describe (low value awareness) and believe in values that are objectively right and applicable to everyone (high value normativity). Furthermore, positive immigration attitudes also correlate with the idea that values have little meaning in everyday life (low value relevance) and are often contradictory and not easy to implement (low value consistency). Vice versa, elderly people those who received primary or secondary education and those who value tradition tend to perceive immigration as threatening. This seems especially true for people, that claim to be highly aware of their own values (high value awareness), and think the right values differ from person to person (low value normativity). The regression models also suggest that people who see values as guidelines in their life (high value consistency) and perceive them as very important in their life (high value relevance) share a negative view on immigration. Therefore, the article has shown, that value conceptualisation contributes to explaining variations in attitudes towards immigration.

All value conceptualisation dimensions were found to have an inverted u-shape relationship with attitudes towards immigration, with global maxima at zero (the mean value) or slightly below. This suggests that in most cases, more distinct/extreme opinions on value conceptualisation correlate with more negative views on immigrants, while average opinions on value conceptualisation give the most positive outlook on immigration.

Finally, the current study asked if value conceptualisation and value priorities interact in their relation to attitudes towards immigration. In most cases, interaction effects were not statistically significant. Three exceptions can be noted: (1) the curvilinearity of value relevance moderates the relationship between universalism and attitudes towards immigration; (2) value normativity as well as (3) value validity moderate the slope of tradition on attitudes towards immigration. Taken together, these results reveal a complex interrelation between values, their conceptualisation and attitudes towards immigration. Apparently, value conceptualisations directly affect the way we perceive immigrants and they also shape the influence our values have on these perceptions. Value conceptualisation therefore can be understood as an interesting context variable that might enhance the predication of attitudes from value priorities, although more research is needed.

The present study is the first empirical investigation of the role that value conceptualisation takes for attitudes in any dimension. As an exploratory and innovative effort, it is not without limitations. Both theoretical and empirical references to value conceptualisations are fragmented within the literature of multiple disciplines. This article tried to contribute to a systematic overview of previous findings, but acknowledges the gaps in knowledge that perforate the basis of such an empirical endeavor. In addition, the database of the present study is limited to one national survey and could not determine the distinctiveness or generalities of the presented findings for other countries. The data set also lacks information on non-response, which might hide biases in participant selection. Finally, value conceptualisation is far from a straightforward concept and the curvilinear and moderating relationships found in our models only complicate thinking about what this phenomenon entails. Surely, more testing could ensure that this new instrument is robust against interview misinterpretations and could expand our understanding of how different value conceptualisations are formed. Nonetheless, the study identified an interesting new concept, at the intersection of value research, migration research and political education, which future researchers may find useful to consider.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Compared to the proportions of foreign citizens in 2016 in Germany (11%), Spain (10%), Great Britain (8.6% foreign), Italy (8%), and Sweden (8%).

2 Another example is values being conceived as ‘personality traits’ and ‘tangible’ while others describe them as ‘learned through experiences’ and ‘changing’. Furthermore, some students argued that values ‘dictate decisions’ like ‘a rule of law’ and ‘wouldn’t compromise’ while others see values as ‘a social construct’.

3 Since both interpretations are mathematically identical, I will discuss the results from both perspectives.

4 The theory of values has since been refined to include 19 values, included a refined survey item (Schwartz et al., Citation2012). Unfortunately, the ÖWBS did not include this refined measurement. Future studies should adapt this model, and the presented results should be interpreted with care.

5 For visual examination in a scatterplot these variables were jittered by a random variable (ranging from –0.1 to 0.1) to avoid overplotting (Cohen et al. Citation2003, 111).

6 Vice versa, in people that value tradition (see TR-sd in b) the higher the validity of values the more positive attitudes towards immigration are found. On the other side, in people that do not put a lot of importance on tradition (see TR+sd in b) above average value validity lowers attitudes towards immigration.

References

- Akrami, Nazar, Bo Ekehammar, and Tadesse Araya. 2000. “Classical and Modern Racial Prejudice: A Study of Attitudes Toward Immigrants in Sweden.” European Journal of Social Psychology 30 (4): 521–532.

- Alarian, Hannah M., and Michael Neureiter. 2019. “Values or Origin? Mandatory Immigrant Integration and Immigration Attitudes in Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies.

- Bahry, Donna. 2016. “Opposition to Immigration, Economic Insecurity and Individual Values: Evidence from Russia.” Europe-Asia Studies 68 (5): 893–916.

- Bardi, Anat, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2003. “Values and Behavior: Strength and Structure of Relations.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 29 (10): 1207–1220.

- Barry, Ellen, and Martin Selsoe Sorensen. 2018. In Denmark, Harsh New Laws for Immigrant ‘Ghettos’. The New York Times.

- Battacharyya, Gargi. 2016. Ethnicities and Values in a Changing World. London: Routledge.

- Beierlein, Constanze, Anabel Kuntz, and Eldad Davidov. 2016. “Universalism, Conservation and Attitudes Toward Minority Groups.” Social Science Research 58: 68–79.

- BMEIA. 2015. 50 Punkte-Plan zur Integration von Asylberechtigten und subsidär Schutzberechtigten in Österreich. In F. M. f. E. a. I. A. Austria (Ed.).

- Boer, Diana, and Ronald Fischer. 2013. “How and When Do Personal Values Guide Our Attitudes and Sociality? Explaining Cross-Cultural Variability in Attitude–Value Linkages.” Psychological Bulletin 139 (2013): 1–35.

- Branson, Christopher Michael. 2004. “An Exploration of the Concept of Values-Led Principalship.” Doctor of Philosophy. Australian Cathlic University.

- Bretschneider, Rudolf, and GfK Austria. 2017. Integration und Zusammenleben. Was Denkt Österreich? Wien: Österreichischer Integrationsfond.

- Castels, Stephen, Maja Korac, Ellie Vasta, and Steven Vertovec. 2002. Integration: Mapping the Field. University of Oxford: Centre for Migration and Policy Research and Refugee Studies.

- Chao, Ruth Chu-Lien, Meifen Wei, Lisa Spanierman, Joseph Longo, and Dayna Northart. 2015. “White Racial Attitudes and White Empathy: The Moderation of Openness to Diversity.” The Counseling Psychologist 43 (1): 94–120.

- Civic Integration Act. 2006. Wet inburgering / Civic Integration Act. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0020611/2020-07-01.

- Coenders, Marcel, and Peer Scheepers. 2003. “The Effect of Education on Nationalism and Ethnic Exclusionism: An International Comparison.” Political Psychology 24 (2): 313–343.

- Cohen, Jacob, Patricia Cohen, Stephen G. West, and Leona S. Aiken. 2003. Applied Multiple Regression/Correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (3rd ed). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Davidov, Eldad, and Bart Meuleman. 2012. “Explaining Attitudes Towards Immigration Policies in European Countries: The Role of Human Values.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 38 (5): 757–775.

- Davidov, Eldad, Bart Meuleman, Jaak Billiet, and Peter schmidt. 2008. “Values and Support for Immigration: A Cross-Country Comparison.” European Sociological Review 24 (5): 583–599.

- Davidov, Eldad, Bart Meulemann, Shalom H. Schwartz, and Peter Schmidt. 2014. “Individual Values, Cultural Embeddedness, and Anti-Immigration Sentiments: Explaining Differences in the Effect of Values on Attitudes Toward Immigration Across Europe.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 66: 263–285.

- Davidov, Eldad, Daniel Seddig, Anastasia Gorodzeisky, Rebeca Raijman, Peter Schmidt, and Moshe Semyonov. 2020. “Direct and Indirect Predictors of Opposition to Immigration in Europe: Individual Values, Cultural Values, and Symbolic Threat.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (3): 553–573.

- Dietze, Gabriele. 2009. “Okzidentalismuskritik. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen Einer Forschungsperspektivierung.” In Kritik des Okzidentalismus, edited by G. Dietze, C. Brunner, and E. Wenzel, 23–54. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Ditlmann, Ruth, Ruud Koopmans, Ines Michalowski, Anselm Rink, and Susanne Veit. 2016. “Verfolgung vor Armut. Ausschlaggebend für die Offenheit der Deutschen ist der Fluchtgrund.” WZB Mitteilungen 151: 24–27.

- Djuve, Anne Britt. 2010. “‘Empowerment or Intrusion?’ The Input and Output Legitimacy of Introductory Programs for Recent Immigrants.” International Migration & Integration 11: 403–422.

- Edenborg, Emil. 2020. “Endangered Swedish Values: Immigration, Gender Equality, and Migrants Sexual Violence.” In Nostalgia and Hope, edited by O. C. Norocel, A. Hellström, and M. B. Jorgensen, 101–117. Springer Open.

- Eisentraut, Marcus. 2019. “Explaining Attitudes Toward Minority Groups with Human Values in Germany – what is the Direction of Causality?” Social Science Research 84: 102324.

- Elton-Chalcraft, Sally, Vini Lander, Lynn Revell, Diane Warner, and Linda Whitworth. 2017. “To Promote, or not to Promote Fundamental British Values?” British Educational Research Journal 43 (1): 29–48.

- ESS 7. 2014. European Social Survey Round 7 Data, Data File Edition 2.2.

- EU. 2014. Common Basic Principles for Immigrant Integration Policy in the EU [Press release]. https://ec.europa.eu/migrant-integration/librarydoc/common-basic-principles-for-immigrant-integration-policy-in-the-eu.

- Fernandes, Ariana Guilherme. 2002. “(Dis)Empowering New Immigrants and Refugees through their Participation in Introduction Programs in Sweden, Denmark, and Norway.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 13 (3): 245–264.

- Flowers, Charne. 2002. Values and Civic Behaviour in Australia. Project Report. Melbourne: Brotherhood of St. Lawrence.

- Fritzsche, Nora. 2016. “Antimulsimischer Rassismus im offiziellen Einwanderungsdiskurs.” Working Paper des Center for Miffle Eastern & North African Politics, Freie Universität Berlin(13).

- Goren, Paul, Harald Schoen, Jason Reifler, Thomas J. Scotto, and William O Chittick. 2016. “A Unified Theory of Value-Based Reasoning and U.S. Public Opinion.” Political Behavior 38 (4): 977–997.

- Grant, Peter R. 2008. “The Protest Intentions of Skilled Immigrants with Credentialing Problems: A Test of a Model Integrating Relative Deprivation Theory with Social Identity Theory.” British Journal of Social Psychology 47 (4): 687–705.

- Halman, Loek, Inge Sieben, and Marga van Zundert. 2011. Atlas of European Values. Trends and Traditions at the Turn of the Century. Leiden: Brill.

- Hofstede, Geert. 2001. Culture's Consequences. Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

- Howe, Lauren C., and Jon A. Krosnick. 2017. “Attitude Strength.” Annual Review of Psychology 68: 327–351.

- Inglehart, Ronald. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural Economic, and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Integrationskursverordnung. 2004. Verordnung über die Durchführung von Integrationskursen für Ausländer und Spätaussiedler. Bonn.

- Joppke, Christian. 2007. “Beyond National Models: Civic Integration Policies for Immigrants in Western Europe.” West European Politics 30 (1): 1–22.

- Khan, Amadu Wurie. 2013. “Asylum Seekers / Refugees’ Orientations to Belonging, Identity & Integration into Britishness.” Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, 153–179.

- King, Russel, and Ronald Skeldon. 2010. “‘Mind the Gap!’ Integrating Approaches to Internal and International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (10): 1619–1646.

- Klages, Helmut. 2001. “Brauchen wir Eine Rückkehr zu Traditionellen Werten?” Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte 29: 7–14.

- Klages, Helmut, and Thomas Gensicke. 2006. “Wertsynthese – Funktional Oder Dysfunktional.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 58 (2): 332–351.

- Kluckhohn, C. K. M. 1951. “Values and Value Orientations in the Theory of Action.” In Toward a General Theory of Action, edited by T. Parsons and E. A. Shils, 388–433. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Knoppen, Desirée, and Willem Saris. 2009. “Do we have to Combine Values in the Schwartz’ Human Values Scale? A Comment on the Davidov Studies.” Survey Research Methods 3 (2): 91–103.

- Köbel, Nils. 2018. Identität – Werte – Weltdeutung. Weinheim Basel: Beltz Juventa.

- Kroh, Martin. 2006. “Taking ‘don't knows’ as Valid Responses: A Multiple Complete Random Imputation of Missing Data.” Quality & Quantity 40: 225–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-005-5360-3.

- Larin, Stephen J. 2020. “Is it Really about Values? Civic Nationalism and Migrant Integration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (1): 127–141.

- Malle, Bertram F., and Eric Edmondson. 2004. What are Values? A Folk-Conceptual Investigation. ICDS technical reports. Institute of Cognitive and Decision Sciences.

- Mashlah, Samer. 2015. “The Role of People's Personal Values in the Workplace.” International Journal of Managment and Applied Science 1 (9): 158–164.

- McMahon, Joan M., and Darren J Good. 2016. “The Moral Metacognition Scale: Development and Validation.” Ethics & Behavior 26: 5.

- McPherson, Melinda. 2010. “‘I Integrate, Therefore I Am’: Contesting the Normalizing Discourse of Integrationism through Conversations with Refugee Women.” Journal of Refugee Studies 23 (4): 546–570.

- Mensing, Birte. 2016. “‘Othering’ in the News Media: Are Migrants Attacking the ‘Fortress Europe'?” (Bachelor of Public Governance Across Borders). University of Twente.

- Michalowski, Ines. 2004. An overview on introduction programmes for immigrants in seven European Member States. Den Haag.

- Morrice, Linda. 2017. “Cultural Values, Moral Sentiments and the Fashioning of Gendered Migrant Identities.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 43 (3): 400–417.

- Mouritsen, Per. 2008. “Political Responses to Cultural Conflict: Reflections on the Ambiguities of the Civic Turn.” In Constituting Communities, edited by P. Mouritsen and K. E. Jorgensen, 1–30. New York: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Norman, Wayne. 1995. “The Ideology of Shared Values: A Myopic Vision of Unity in the Multi-Nation State.” In Is Quebec Nationalism Just? Perspectives from Anglophone Canada, edited by J. H. Carens, 137–159. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- Ponizovskiy, V. A. 2016. “Values and Attitudes Towards Immigrants: Cross-Cultural Differences Across 25 Countries.” Psychology.Journal of Higher School of Economics 13 (2): 256–272.

- Rohan, Meg J. 2000. “A Rose by Any Name? The Values Construct.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 4 (3): 255–277.

- Rokeach, Milton. 1973. The Nature of Human Values. New York: The Free Press.

- Roßteutscher, Sigrid. 2004. “Von Realisten und Konformisten – Wider die Theorie der Wertsynthese.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 56 (3): 407–432.

- Roßteutscher, Sigrid. 2005. “Wertsynthese: Kein Unsinniges Konzept, Sondern Traurige Realität.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 57 (3): 543–549.

- Schneider, Silke L. 2008. “Anti-immigrant Attitudes in Europe: Outgroup Size and Perceived Ethnic Threat.” European Sociological Review 24 (1): 53–67.

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2009. “Basic Values: How They Motivate and Inhibit Prosocial Behavior.” In Prosocial Motives, Emotions, and Behavior, edited by M. Mikulincer and P. R. Shaver, 221–241. Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Schwartz, Shalom H. 2012. “An Overview of the Schwartz Theory of Basic Values.” Online Readings in Psychology and Culture 2 (1): 1–20.

- Schwartz, Shalom H, Jan Cieciuch, Michele Vecchione, Eldad Davidov, Ronald Fischer, Constanze Beierlein, … Mark Konty. 2012. “Refining the Theory of Basic Individual Values.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 203 (4): 663–688. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029393.

- Schwartz, Shalom H., and Tammy Rubel. 2005. “Sex Differences in Value Priorities: Cross-Cultural and Multimethod Studies.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 89 (6): 1010–1028.

- Seewann, Lena, and Roland Verwiebe. 2020. “How do People Interpret the Value Concept? Development and Evaluation of the Value Conceptualisation Scale Using a Mixed Method Approach.” Journals of Beliefs & Values 41 (4): 419–432.

- Thome, Helmut. 2004. “‘Wertsynthese’: Ein Unsinniges Konzept?” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 57 (2): 333–341.

- Tyler, Imogen. 2010. “Designed to Fail: A Biopolitics of British Citizenship.” Citizenship Studies 14 (1): 61–74.

- Vecchione, Michele, Gianvittorio Caprara, Harald Schoen, Gonzàlez Castro, Josè Luis, and Shalom H. Schwartz. 2012. “The Role of Personal Values and Basic Traits in Perceptions of the Consequences of Immigration: A Three-Nation Study.” British Journal of Psychology 103: 359–377.

- Vernon, Philip E., and Gordon W. Allport. 1931. “A Test for Personal Values.” The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 26 (3): 231–248.

- Verwiebe, Roland, Lena Seewann, and Margarita Wolf. 2018. “Migration und Flucht.” In Europasoziologie, edited by M. Bach and B. Bach-Hönig, 229–240. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- ÖWBS. 2016. Österreichischer Wertebildungs-Survey / Austrian Value Formation Survey.

- Zetter, Roger. 2007. “More Labels, Fewer Refugees: Remaking the Refugee Label in an Era of Globalization.” Journal of Refugee Studies 20 (2): 172–192.

- Zupan, Krista A. 2012. “Values, Conflicts & Value Conflict Resolution.” Doctor of Education. University of Toronto.