ABSTRACT

Temporary transnational migration of Nepali migrant workers has resulted in remittances now accounting for over 27 per cent of the country’s GDP. This article analyzes the domestic labour migration policy sector of Nepal using primary data to visualise the migration policy network through Social Network Analysis and explores the dynamics between the dominant actors involved in the regulation of the temporary labour migration regime. It finds a fragmented migration sector in Nepal where government agencies were not seen as leaders in the field but instead perceived to be heavily influenced by the private sector during the policy-making process, bringing their regulatory role into question. In such a situation, civil society organisations could have played a critical role as a watchdog and strong advocate for migrant workers but several factions and conflicts were apparent within them, resulting in low trust and high competition for funds. The article shows that different actors from the labour migration regime have a role in vigilantly watching for any abuse of power to ensure that the policy and regulatory environment is not influenced by certain actors to their benefit and to the detriment of temporary labour migrant workers.

Introduction

Temporary migration in search for better employment opportunities isn’t a new phenomenon. In recent years, there has been much research on ‘managing’ migration (Ghosh Citation2000; Klekowski von Koppenfels Citation2001Martin, Abella, and Kuptsch Citation2006a; Martin, Martin, and Weil Citation2006b) or the ‘global governance of migration’ (Betts Citation2012; Grugel and Piper Citation2007; Koslowski Citation2011; Kunz, Lavenex, and Panizzon Citation2012; Martin Citation2015). And even though cross-border migration for work is on the global policy agenda with several global conferences, with international organisations working on the issue, a global migration regime hasn’t emerged yet. Instead migration is currently governed by a set of formal and informal measures at the domestic, bilateral, regional and global levels.

Countries of origin and countries of destination have diverse priorities, complicating any possible agreement on a migration regime. In addition, there is a clear asymmetry of power in the international migration governance system where migrant receiving countries are usually global or regional hegemons with economic and military clout (S. F. Martin Citation2015) and can thus become implicit ‘rule-makers’, while sending states have to become ‘rule-takers’ (Betts Citation2011). Such asymmetry of power is especially evident during bilateral negotiations, which is one of the reasons it is still preferred by powerful destination states instead of multilateralism.

In recent years, there has been an attempt to situate the management of labour migration within the migration-development nexus linking its role to development. Circular labour migration has been promoted as a ‘triple win’ bringing benefits to the destination country, the origin country and the migrant workers themselves. Such arguments have been seen in international meetings, and even in regional consultative processes on migration. Temporary circular labour migration has been used to meet the labour market needs in destination countries without permanent settlement, while allowing a steady flow of remittances to the country of origin (Wickramasekara Citation2011). But the focus on the ‘triple win’ completely bypasses any focus on the labour and human rights of the migrant workers. Temporary foreign workers are not always governed by the same labour laws of destination countries nor are they allowed to join labour unions in many countries so low-skilled/low-wage temporary contract workers remain in highly vulnerable and exploitative situations. It is in this context that the interplay between migrant agency, the drivers of migration and its governance becomes significant (Carling and Collins Citation2017; Carling and Schewel Citation2018; Triandafyllidou Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2022).

For labour-sending nations, temporary labour migration has become a substantial source of income as remittances sent by migrant workers have steadily grown over time (Withers, Henderson, and Shivakoti Citation2021). In 2019, remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries equated to US$554 billion, becoming larger than foreign direct investment (FDI) (World Bank Citation2020). Remittances are seen to be steady even during times of uncertainty or physical disasters (Bettin, Presbitero, and Spatafora Citation2014; Shivakoti Citation2019; Yang and Choi Citation2007). Even though the World Bank initially estimated a 20 per cent reduction in remittance transfers to the Global South due to COVID-19, remittance flows to low- and middle-income countries remained resilient with only a 1.6 per cent drop from the 2019 levels (Arnold Citation2021).

Temporary labour migration has become an important phenomenon in Asia as thousands of South and South-East Asian men and women move to work in low-waged sectors such as construction and domestic work and send remittances back home. Their transnational status has meant that they are usually not governed by domestic host country labour laws in some cases, but cannot access social security in their home country. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the precarity of regulated temporary migration to the forefront in many ways (Deshingkar Citation2019; Lewis et al. Citation2015; Wee, Goh, and Yeoh Citation2019), including the sustainability of remittances as source of development capital for labour-sending countries (Foley and Piper Citation2021; Grugel and Piper Citation2007; Spitzer and Piper Citation2014; Yeoh Citation2020).

With remittances now accounting for a substantial percentage of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for some labour-sending countries, governments have become more involved in creating sophisticated systems around temporary labour migration, raising questions on whether it is a government strategy to export labour. Even though labour migration was initially seen as a temporary measure, it has now become a permanent feature for many labour-sending nations as a ‘culture of migration’ (Kandel and Massey Citation2002) develops and it becomes a generational right of passage in some countries. At the same time migrants are celebrated as modern-day heroes (Encinas-Franco Citation2013) in their roles supporting their families and country.

This special issue distinguishes between temporariness as a policy category and a category of practice. There are several important focuses within the policy category: the role of the state or of international conventions that regulate migrations, forced temporariness, regulated temporariness and flexible temporariness (Triandafyllidou Citation2022). This article contributes to the focus on regulated temporariness as a policy category by providing an in-depth analysis of the domestic migration policy sector of a significant labour-sending country within South Asia: Nepal, to understand how the state-society dynamics between the different actors in the migration policy network affects policies for temporary labour migrant workers and their rights. The regulation of temporary labour migration is dependent on the domestic actors and the migration policy environment of labour-sending countries, which plays a fundamental role as it can have noteworthy consequences for migrants. As labour migration has drastically increased, in volume and location, labour sending governments have had to increasingly rely on non-state actors, both domestically and internationally, to provide information, trainings, and services at home and abroad, and for rescue and repatriation. So understanding the different dynamics between the actors at the domestic level is now vital as migration policymaking often involves both state and societal actors in complex systems of mutual interactions. This article explores these relations between governmental actors, civil society organisations (CSOs) and private intermediaries, who are collectively behind the lucrative temporary labour migration industry and the regulation of temporary transnational labour migration. The rest of the article is structured as follows: I begin by introducing why networks can be an useful tool in studying complex issues such as migration policymaking. The next section provides a contextual background of Nepal’s migration industry by introducing the major actors in the domestic migration policy sector. I then explain the methodology used for this research, before presenting the findings from the social network analysis and the qualitative analysis. The article ends with a critique of the regulated temporary labour migration sector and concluding remarks.

Networks and policymaking

The high degree of interdependence and uncertainty in migration governance makes the use of networks ideal to study the links between various actors involved in the process. Networks are seen as an alternative to hierarchy and a reaction against the idea of a monolithic state that controls the process of policymaking alone and that policy making actually takes place in policy domain specific subsystems consisting of diverse actors such as government agencies, non-profits, and for-profits, who are mutually interdependent (Adam and Kriesi Citation2007) and are characterised by the predominance of informal, decentralised, and horizontal relations (Kenis and Schneider Citation1991).

Policy makers have supported the development of networks as a response to complex problems and as a way of levering in resources and expertise from beyond government (Blanco, Lowndes, and Pratchett Citation2011). McGuire describes networks as ‘structures involving multiple nodes – individuals, agencies, or organizations – with multiple linkages’ and that network structures are typically intersectoral, intergovernmental, and based functionally in a specific policy or policy area (McGuire Citation2006).

There have been several studies on the social networks of migrants as their interpersonal and organisational social ties affect who migrates, to which destinations, what kinds of employment they are able to obtain in host countries and how they integrate in the host society and remain connected to their community and homelands (Garip and Asad Citation2016; Haug Citation2008; Liu Citation2013; Poros Citation2001; Ryan et al. Citation2008; Tabuga Citation2021). Through their bonds of trust and reciprocity, these networks are thought to counter the disadvantages that migrants may encounter in destination countries. This article uses social networks to study the policy network for the migration sector for Nepal instead of personal social networks of migrants. It takes an in-depth look at the various actors involved in the policy network by identifying the actors, the structure of the network and the nature of the relations between the actors and their impact on policies related to labour migrant workers.

Interactions within and among government agencies and social organisations constitute policy networks that are instrumental in formulating and developing policy. Rhodes argued that networks varied according to their level of ‘integration’, which was a function of their stability of membership, restrictiveness of membership, degree of insulation from other networks and the public, and the nature of the resource they controlled (Rhodes Citation1985). Policy networks can also be seen to affect policy outcomes through their exclusionary or inclusionary nature as it ensures that certain groups and policy options are either suppressed or guaranteed. On the other hand, cohesion among a policy network's members emerges when there is a consensus on what should be the contents of public policy, what problems the network should deal with and how they should be solved (Daugbjerg and Marsh Citation1998).

Nepal’s migration industry

Contemporary labour migration from Nepal in larger numbers only started since the early 1990s after the restoration of democracy and liberalised economic policies adopted after 1992, helping formalise labour migration and opening doors for recruitment and remitting agencies to operate (Ministry of Labour and Employment Citation2014). A second major event that led to rapidly increased outflow of migrants from Nepal was the Maoist insurgency, which led to a 10-year armed conflict (1996–2006). This conflict resulted in large internal and external migration, because of security issues and also because it significantly stifled national economic development.

Even though foreign temporary labour migration has become an omnipresent phenomenon now, it was only in 1993 that the Department of Foreign Employment (DOFE) first began keeping official records of Nepalese migrating abroad for employment, beyond India by issuing labour permits (Sijapati and Limbu Citation2012). DOFE segregated data by sex even later, from 2005/06 and by geographic origins of migrants from 2011/2012. Prior to 1990, India was the major destination for most Nepalese as a result of the open border between the two countries but since the early 2000s, there has been an unprecedented increase in the volume of temporary workers headed to other Asian countries such as the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, Malaysia, Korea and elsewhere. Estimates of the number of Nepali migrants abroad vary widely, even though DOFE has issued over 4 million labour approvals between 2008/2009–2018/19 (Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security Citation2020), others have estimated that the figures are much higher when including seasonal workers in India (no official records due to the open border between the two countries) and those using informal channels (Sapkota Citation2011).

According to the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security, labour migration from Nepal is predominantly male and more than 80 per cent of the total labour migrant population in 2017/18 and 2018/19 were between the ages of 18 and 35. The share of workers taking up low-skilled work was high at 59 per cent in 2018/19. The main sectors they work are in construction, manufacturing, hospitality and domestic work. The top five destination countries for Nepali migrants in 2018/19 were Qatar, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Malaysia, accounting for 88 per cent of migrant workers (Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security Citation2020).

Nepal’s dependence on remittances has been steadily growing over the years, with remittances now amounting to US$8.1 billion or 27.3 per cent of its GDP in 2019 (World Bank Citation2020). In terms of equivalence to GDP, Nepal is the fifth-most remittance-dependent economy in the world (World Bank Citation2020). At the household level, labour migration is thought to be one of the main livelihood strategies as it was reported that 56 per cent of all households received remittance (Central Bureau of Statistics Citation2011), with the share of remittance accounting for around 35 per cent of the household income (Ratha, Mohapatra, and Silwal Citation2010). Labour migration is also thought to be a major contributing factor to poverty reduction in the country as the poverty rate fell from 42 per cent to 31 percent to 25 percent between 1995–96, 2003–04 and 2010–11 respectively (Central Bureau of Statistics Citation2011).

Foreign temporary labour migration is a cross-cutting issue and several government departments are involved in the labour migration governance process. In addition to the institutional framework, an evolution in the legislative framework is also seen in Nepal. The migration industry has been defined as ‘the array of non-state actors who provide services that facilitate, constrain or assist international migration’ (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg-Sorensen Citation2013) and the migration industry in Nepal includes various intermediaries such as private recruitment agencies (called manpower companies in Nepal), training and testing centres, visa and travel support and those providing various documentations as needed (Kern and Müller-Boker Citation2015). According to DOFE, there are over 800 registered recruitment agencies in Nepal, however, it is estimated that over 80,000 unlicensed local agents operate at the district level (Paoletti et al. Citation2014) and that around $260 million is paid to these agencies per year by migrant workers (Adhikari and Gurung Citation2011; Jones and Basnett Citation2013). The regulation of the recruitment agencies is often complicated with the difference between registered recruitment agencies and the unlicensed local agents, the relations between agents at the country of origin and destination and the difficulty in holding agencies accountable across multiple jurisdictions with different regulatory regimes (Agunias Citation2013). The commercialisation of the migration industry has meant that many migrant workers are taking heavy loans to pay for their migration journeys, resulting in long-lasting debt. Civil society organisations are also involved in disseminating information as well as providing support to migrants in need.

Methodology

This article uses networks as an analytical tool to study the domestic migration sector of Nepal, using both qualitative and quantitative methods. The Social Network Analysis (SNA) method focuses on analyzing the relationships among actors within a network and provides a visual network of the structure of the migration network and helps identify the core and dominant actors in the sector. The ability to study society based on relations between individuals or organisations instead of their attributes makes it a unique method. To understand the nuances of the network and the relationships present, a qualitative analysis of interviews was also conducted for this research.

This article draws on research conducted on Nepal’s migration policy sector between December 2014 and May 2015. The first step for this research was to identify members of the labour migration policy network of Nepal. An initial list was created under the headings of government, private agencies, trade unions, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), International Non-Governmental Organizations (INGOs)/donor agencies, media and research institutes based on review of government documents and participant lists from talks and workshops. The list was shown to several key informants who were asked to add any missing organisations. This roster was finally shared with the organisations themselves during meetings and interviews and the snowball method was used by asking the respondents to provide information about the identities of other relevant organisations to be added to the list until a point of saturation when new members weren’t being identified. Even though these steps were followed to create an exhaustive list of actors, it is possible that some policy actors could be missing from this list. One reason is that the centralised nature of migration policy actors in the capital city of Kathmandu means that organisations working outside of the city could be overlooked even during the snowball process by those in the network. Another reason is that there are hundreds of actors involved in the private sector such as individual recruitment centres, subagents, brokers, travel agencies, insurance agencies, training centres, health clinics and it is not possible to include every one of them in this list, so associations such as the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies (NAFEA), which represents hundreds of recruitment agencies were included instead. Lastly, it is important to understand that the migration network that is presented below is a snapshot based on the policy actors in the migration sector and their relations from 2015. The network changes as members join and leave the sector and their relations and dynamics change over time.

During the meetings, each agency official was asked to fill out the SNA survey questionnaire before answering a set of semi-structured interview questions. shows the total number of actors listed in the labour migration policy sector for Nepal and the number of them who were interviewed and those who filled out the survey.

Table 1. Policy actors in the migration sector.

Each organisation was presented with the network roster consisting of all actors in the domestic migration policy sector and they were asked to rank their relationship with each in terms of their level of collaboration (to work or collaborate with on labour migration issues). Each respondent had to rate the frequency for the relation on a scale of 1–5, with 1 being most rarely and 5 being most frequently. They could also write 0 if there were no relations. This survey data represents bidirectional relationships and can be mapped as a directed graph based on the responses.

In-depth interviews were also conducted with agency officials to understand the on-the-ground relations between the actors in the sector. Interviews were translated (Nepali to English) and transcribed by the researcher and with help from a research assistant. During the interview schedule, an earthquake of 7.8 Richter scale struck Nepal, which disrupted this research and had to be continued after some months with the support of a Nepali researcher. A total of 32 interviewees responded to requests for interviews while 31 agencies filled out the network survey for this research.

Migration policy network of Nepal

Policy network analyses have focused on the relationships between policy-making outcomes, the structure of a network and the inclusion or exclusion of certain individuals or groups from within that network. This study uses Social Network Analysis (SNA) to identify the structure of the migration policy network of Nepal and to identify the powerful groups in the core of the network. The SNA method provides a great visual by identifying the main actors in the migration network, however, the nuances of the relations and power dynamics between the actors in this group were better understood through in-depth interviews.

The overall migration policy network for Nepal had 40 organisations in total during the time of this research in 2015, these included 6 government agencies, 4 private agencies, 4 trade unions, 9 NGOs, 13 INGOs and donor agencies, 1 media organisation, and 3 research organisations. Among the 40 organisations, 31 responded to the survey and there is data (including complete and partial data) from 77.5% of the network. The software NODEXL was used for this analysis.

Authors like Marsh and Rhodes have stressed the importance of the structural aspect of networks as they see networks as structures of resource dependency, which affects policy outcomes (Marsh and Rhodes Citation1992). The centrality of an organisation is a good measure to assess their overall importance (Mukherjee Citation2013) as centrality measures how close an individual or organisation is to the centre of the action in a network and gives a rough indication of the social power of a node based on how well they connect the network. The more central the organisation is in the network, the more opportunities it has to access resources, information and support from the network and is able to guide, control or even broker the flow of information and resources among others. This research uses degree centrality as the centrality measure and it is defined as the number of links or ties a node has. Degree is often interpreted in terms of the immediate risk of node for catching whatever is flowing through the network (such as a virus, or some information).

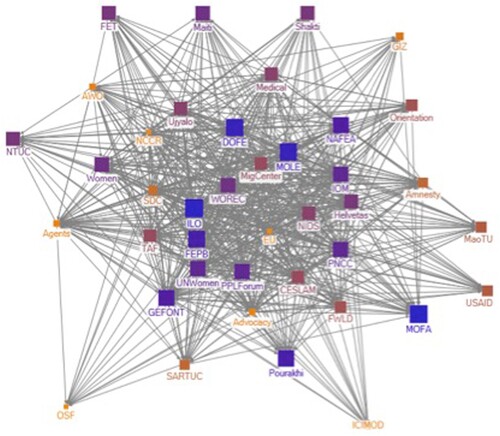

The survey asked each organisation to rank the other organisations on a scale of 1–5 on their level of collaboration on labour migration issues, and this data was used to create the collaboration matrix below. It shows the in-degree centrality and the nodes are sized and coloured (scale with blue being the highest in-degree and orange the lowest) according to in-degree centrality. The largest and bluest squares represent the most central organisations based on in-degree centrality numbers .

The figure shows that the largest in-degrees include several of the major government agencies with a mandate on labour migration, and a mix of NGOs, INGOs, trade unions and recruitment agencies.

Policy networks have been defined as (more or less) stable patterns of social relations between interdependent actors, which take shape around policy problems (Kickert, Klijn, and Koppenjan Citation1997). The stable power structures are usually dominated by a core of peak associations and governmental actors. Access to central positions requires information, both technical expertise and political knowledge, and resources, both material and symbolic. To identify the core of the network with peak associations and actors, those with a higher in-degree centrality than the network average (22) were isolated and 19 organisations remained. This group is regarded as the ‘Core’ while the remaining are regarded as the ‘Periphery’ in terms of their importance in the network by in-degree centrality .

We see a crucial role of the government agencies with all six labour migration related agencies: the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), the Ministry of Labour and Employment (MOLE), the Department of Foreign Employment (DOFE), Foreign Employment Promotion Board (FEPB), Foreign Employment Tribunal (FET) and the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare listed among the core group. We also see the importance of the NGOs as six of the nine listed are in the core: Pourakhi, Pravasi Nepali Coordination Committee (PNCC), People’s Forum, Maiti Nepal, Women’s Rehabilitation Center (WOREC), and Shakti Samuha. Among the thirteen listed INGO/Donor agencies, only four are listed in the core: International Labour Organization (ILO), International Organization for Migration (IOM), UNWomen and Helvetas. Two Trade Unions, General Federation of Nepalese Trade Unions (GEFONT) and Nepal Trade Union Congress (NTUC), are listed in the core group. Among the private sector associations, only Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies (NAFEA), the largest recruitment agency association is included. It can be noted that the organisations in the ‘periphery’ may be involved in temporary labour migration but not to the same extent as those remaining in the core. This is especially true for civil society organisations that work on a variety of issues where migration related projects could be funding and time dependent.

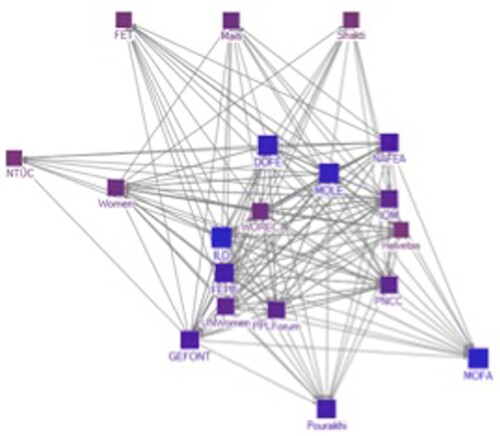

The same process of isolating actors further is repeated so we can identify 12 actors with the highest in-degree, who can be identified as comprising the powerful ‘dominant coalition’ in the sector .

The dominant coalition includes four government agencies, including the ones with mandate over labour migration: MOLE, DOFE, FEPB and MOFA. From the domestic NGOs, Pourakhi, PNCC and People’s Forum remain while from the INGO/Donor groups, ILO, IOM and UNWomen remain. NAFEA as the largest private association is still among the dominant actors and so is the trade union GEFONT, which has a long history of working with labour migrant workers.

Identifying the organisations that form the dominant coalition has wider implications for the sector as the central position of the group means that they hold substantial power, knowledge, influence, resources and decision-making authority. It is interesting to note that both the core group and the dominant coalition includes a range of actors from the government, private sector and civil society organisations and can initially appear quite inclusive. But who among the dominant coalition has more authority or leverage to influence policy change? Are some members more central and connected than others? Are the government agencies collaborative with all other actors or is the centralised nature of governance requiring all actors to work with them? The nuances of the nature of the relationships present and their implications became clearer through the interviews with network members. One aspect that was apparent from the interviews is that even though the dominant coalition appears inclusive of different actors, there is fragmentation between the various groups within the coalition. This is especially true for civil society actors and the private sector.

The role of the state actor and their relationship with other actors is an important issue to analyze. Rhodes and Marsh have written that this relation can take different forms with the state being the main decision maker while other actors are in the periphery or it can be more inclusive and collaborative in nature with different actors playing different parts. There can be single actor or a formation of coalitions as well (Sabatier and Jenkins-Smith Citation1999). At a given moment, in a given subsystem we are likely to find a limited number of coalitions with varying influence on the political processes within the subsystem (Kriesi, Adam, and Jochum Citation2006). Sometimes in domain-specific policy-making, it can be dominated by one coalition which Baumgartner and Jones have termed a ‘policy monopoly’ (Baumgartner and Jones Citation1993).

To explore these issues, the role of the state was explored in the interviews along with questions on which actors were most powerful and influential. The government, given its authority in the policy-making process has an important role and is thus a central and powerful actor. When asked who they thought was a leader in the sector, many interviewees stated that the government ‘should be’ the leader and main decision-maker given its authority but it was instead seen as easily influenced, especially by the private sector. As one CSO official stated ‘the link between political parties and manpower companies needs to be investigated, that is the elephant in the room.’

Power structures are often referred to in the literature as being central (Atkinson and Coleman Citation1989; Marsh and Rhodes Citation1992; Van Waarden Citation1992) and actors’ interactions reveal an essential part of the power structure. Power, according to Knoke is an aspect of the actual or potential interactions between two or more social actors (Knoke et al. Citation1996). Since policy network analysis starts on the premise that actors within policy networks need to exchange resources with one another in order to achieve their goals, the power-dependent relationships that emerge from the interactions can tell us who will become the core member of the network and who will be in the periphery and who can be completely excluded. The policy network can be studied to understand whether power is concentrated in the hands of a dominant actor or a coalition of actors, or if it is shared between actors. Interactions between actors can be conflictive or competitive, there can be bargaining involved or it can be cooperative in nature (Kriesi, Adam, and Jochum Citation2006).

For the Nepali migration policy network, the private sector, especially the manpower agencies, were seen to be a powerful component of the temporary labour migration industry. An official from the Ministry of Labour and Employment even described them as ‘leaders of the sector since the marketing is done by manpower agencies’. Several interviewees also mentioned their significant financial and political access. Local NGOs did not believe they could compete with the amount of money, access and power of the recruitment agencies. An official from a national NGO shared that ‘the NGO network is not able to discuss migration related issues with the government while NAFEA is frequently in dialogue with the Ministry proposing new agendas as they have a comparatively easier access’.

Private agencies were seen as being financially strong in the sector which was then used to ‘turn decisions and policies in their favour’ as they were closely associated to decision makers in the government and were sometimes themselves the decision makers. The influence and reach of the recruitment agencies in the government was mentioned by pointing out that the then Labour Minister himself used to own a recruitment agency and that many parliamentarians were also closely associated with manpower agencies. It was also mentioned that ambassadors to several major labour destinations have been directors of manpower companies, which has been criticised for the clear conflict of interest of such postings.

This close nexus of the private agencies, political parties and government officials brings into question the regulatory role of the government as well as the legitimacy of its policies in the temporary labour migration regime. If states are not seen as strong actors in managing the domestic migration network, it can result in a situation where non-state actors can capture the policy process and adopt policy measures that are short term and narrowly focused on providing benefits for themselves without taking broader concerns of the public or migrant interest into account (rent-seeking). If they are successful in influencing public decisions, such narrow interest groups can directly shape the future legal and regulatory environment to the detriment of temporary migrant workers. Such perception can minimise the overall trust in government agencies, especially when it is perceived that the private sector has privileged access while civil society organisations feel excluded in the policy-making process.

During the time of this research in 2015, the government introduced a zero-cost migration policy, which would exempt Nepali workers from paying for visa fees and airfares to the main destination countries. However, manpower agencies went on a strike against this policy resulting in the government having to compromise and agree to 31 of the 35 points put forth by the Nepal Association of Foreign Employment Agencies (Rai Citation2015; Shrestha Citation2015; Sijapati and Kharel Citation2016). The House panel report has called the government’s ‘free visa, free ticket’ scheme a failure due to poor implementation and the Supreme Court issued a directive to effectively implement the scheme (Mandal Citation2019c; Mandal Citation2017). But a survey of over 400 Nepali migrants by Amnesty International found that around two-thirds of the workers were paying over the permitted maximum amount to agencies. The report stated that the government must do more to enforce laws penalising exploitative recruitment agencies (Amnesty International Citation2017). Such events foster perceptions of unfair and easily influenced politics, thereby eroding credibility and legitimacy of the government’s regulatory role in the sector and increasing levels of citizens’ distrust.

In such a situation, civil society organisations could have played a critical role as an overseer and as a strong advocate for migrant workers and their rights. But NGOs themselves recognise their shortcomings. One official, confessed that ‘NGOs should have been a powerful group but we are not because of our internal conflicts.’ Issues related to competition, a reliance on donor funding, lack of trust and cooperation were mentioned. A major dissatisfaction among NGOs themselves and others, was with the fact that their work was project-driven and fund-driven, instead of being issue-driven. Almost all NGOs stated that 80-90% of their funding comes through donors and INGOs. An official shared ‘honestly NGOs working in Nepal see each other as competitors … I don't think we are doing justice to the issue itself because we are just moving projects.’

Civil Society Organizations are seen as important partners in the migration sector, especially for information dissemination, raising awareness, pressurising the government, providing policy feedback, demanding policy change and representing the public voice. But another main dissatisfaction among civil society organisations was that there was a lack of trust especially between the local NGOs and the INGOs & donor agencies. The heavy reliance on funds from donors and INGOs is driving NGOs to compete with each other but it is also building animosity towards the donors. There is a feeling among the local NGOs that INGOs/donors do not see them as partners but only as implementers of projects. NGOs also complained that there was a serious lack of transparency on how and on what basis donors grant funding. One NGO official suggested

“donors may have vested interests and thus patronize particular NGOs over others. Sometimes they decide on giving a large amount of money to one NGO making them long-term partners by arguing that it is easier for them to monitor one organization with a large fund than to monitor many organizations with smaller funds.”

Trade Unions are another important civil society group that have a wide reach but are usually divided by political and ideological strands. Among the different trade unions, GEFONT is the most active one, working with destination country trade unions and has been successful in countries like Korea and Hong Kong but less so in the Middle-East as many countries there do not even allow the formation of unions. During the interviews, it was noted that besides service provision, NGOs could become more involved in advocacy, especially if they work jointly with other networks such as trade unions. Both groups could also have a wider reach to support migrant workers in need at the destination countries.

When asked about how collaborative the labour migration sector was in general, most interviewees shared that it is superficially collaborative, where organisations would come together to celebrate International Migrant’s Day or invite each other for programmes, but that real collaboration was missing. Interestingly, three networks have been created among different CSO groups working on the migration sector but a hierarchy was observable among them as there is a network for national NGOs, another network for INGOs and implementing partners and a third loose network for donor agencies. The network for the national NGOs is called the National Network for Safe Migration (NNSM) created in 2007 and had 14 members by 2015. The network aims to work on advocacy at the national level and to avoid duplication among their member organisations but lack of resources has been a struggle. The second network, the Kathmandu Migration Group (currently renamed as Migration Group Nepal) is between donor agencies, formed in recognition of the need for inter-agency coordination, especially while interacting with the government. Lastly, there was another looser network among INGOs to share work, avoid duplication and to plan joint advocacy in the future.

The interviews have revealed a fragmentation among several groups where there is a closer connection between government and private agencies, which was seen to be exclusionary to other actors. For the policy network to become more inclusionary of the different voices, civil society organisations could become better organised. The donor community and international agencies have a stronger access and connection with government agencies and are seen as more powerful as well. They could use this access and power to insure that their partners, i.e. the local NGOs are included more in the larger policy discussions related to the labour migration policy network.

Conclusion

The governance of temporary labour migration and the migration industry that supports it is complex as it requires us to understand the interplay between the drivers of migration and of migrant agency. This article presents an analysis of temporariness as a policy category, i.e. that of a regulated temporariness. It presents the structure of the migration policy network of Nepal and identifies the important actors at the core of the decision-making process. The actors at the core and those that are able to influence policies according to their interests have direct implications on how temporary migration is regulated and whether the safety and interests of migrant workers are at the forefront in policymaking. The migration policy network is thus a part of the regulated temporary migration regime and is involved in the chain of managing circular temporary labour migration from Nepal.

The analysis of the domestic migration sector of Nepal shows that even though the institutional and legislative framework regarding transnational temporary migration has been built and improved over the years, the government has struggled to keep up to the pace and needs of overseas workers and their welfare, as evident during the COVID-19 global pandemic. The fragmentation between the various groups in the migration network adds to the complexity to the regulation of temporariness. This analysis found that the government agencies are not seen as leaders in the migration sector in Nepal, or as facilitators to better collaboration among other organisations working in the sector. Many interviewees wished the government to lead the sector given their authority and the fact that migrants contribute over 27 per cent of the GDP. Instead, they viewed them as weak and influenced by the private sector during policy formulation and decision-making. This finding challenges the view that the state actor is the main regulator for temporary labour migration regimes and shows that the indirect influence by the powerful private sector, who are directly involved in the process and gain financially from the system through various fees they impose on migrants, has implications for migrant workers. So temporary migration as a policy category is seen to be regulated by market interests and dynamics rather than by governmental policies alone as seen in its inability to implement the ‘zero cost migration policy’ among others. The perception that the private sector was using its financial strength, privileged access and power to influence the regulatory environment to its advantage has serious implications for the temporary migration sector and especially to the regulatory role and legitimacy of the government. The perception that private agencies have succeeded in policy capture, where temporary labour migration policy decisions are repeatedly directed away from the public interest towards a specific interest can exacerbate inequalities, undermine democratic values and erode trust in government.

Mitigating such capture is essential for the public good and this is where the engagement of other stakeholders in the policy network becomes vital in ensuring there are ‘checks and balances’ in the policy-making process to ensure that temporary migration regimes are regulated in the interest of migrant workers and not for market interests. Unfortunately, the other actors in the migration policy network were seen to be competitive and wary of each other. There is a need for different civil society organisations, including national NGOs, INGOs, donor agencies and trade unions, to work together to become stronger advocates for migrant workers and to ensure accountability.

A policy implication of this research is that the fragmentation within the labour migration sector has resulted in changes in the state-society dynamics, which in turn has led to changes in the regulation of temporariness. The state has the authority and resources that other actors do not, and it thus remains an important actor in any network, even in cases where the state is weak and influenced. In such cases, there should be measures in place to prevent policy capture by self-serving interest groups as the state’s legitimacy can be misused to confer broader legitimacy in the regulated temporary labour migration regime. A robust engagement of different stakeholders can play a role to ensure that such influence does not result in harmful policies for migrant workers and that states are accountable in their policy choices.

For labour-sending nations that have come to rely on remittances, there is a struggle to balance the promotion of labour migration versus the protection of labour migrants. Understanding that there is a competition for the same jobs between different labour-sending nations, governments have become more active in promoting labour migration using different venues. For the actors involved in the private intermediary migration industry at the country of origin, the priority is the promotion of labour migration as they earn higher incomes for larger numbers of temporary labour migration they can facilitate. As seen from this research, if the private sector can influence state migration policies and the temporary labour migration regime, they will prioritise their self-interest and not that of the migrant workers. The analysis of the domestic migration policy network and the dominant decision-makers involved thus becomes important in understanding such dynamics related to the regulation of temporary labour migration policy regimes, instead of assuming that the state is the main regulator.

Given the inherent power imbalance seen between labour-origin countries and destination countries and a lack of a global migration regime, protecting labour migrants has been a struggle due to the transnational nature of their employment and because the labour-sending government’s reach and influence at destination countries is weak. Thus exploring the domestic policy-making in regulating temporary migration in the country of origin is imperative to see the dynamics between the state and other actors of the migration policy network and to ensure that the regulatory environment works to protect migrant workers and their rights. This research used primary data to show the structure of the domestic migration policy network for Nepal and used in-depth interviews to explore the dynamics between actors. However, it is important to realise that the structural characteristics of the network presented provide a snapshot for the time this research was conducted in 2015. In recent years, the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security (MOLESS) is seen to be more vigilant in identifying fraudulent manpower agencies via raids, by fining them and by cancelling their permits (Mandal Citation2019a; MyRepublica Citation2020; News24 hours Citation2016). They decentralised the recruitment process by expanding DOFE outside Kathmandu and introduced new systems where migrants can upload required forms and fees online so they can bypass some intermediary actors and costs. They also introduced new measures requiring a substantial increase in security deposit and bank guarantee amounts for recruitment agencies, facilitating mergers and by scrapping the registration of any agency sending less than 100 workers abroad per year, bringing down the number of manpower companies from 1200 to 850 (MyRepublica Citation2019; Panday Citation2019). Many of these policies were brought into effect by the Minister of Labour, Employment and Social Security, Gokarna Bista who had a tenure of less than two years (2018–2019). Despite his far-reaching positive policy decisions for the sector, or rather because of them, he was sacked during a cabinet reshuffle by the Prime Minister under pressure from the recruitment agencies (Mandal Citation2019b; Nepali Times Citation2019). These events support our analysis and show that there is still a strong nexus between political parties and the private sector and that they have the financial means and political power to change rules and regulations and even people in power to their benefit. Policy networks are not static and change with time so it would be of interest for future researchers to conduct similar studies to track how the labour migration policy network has evolved over time and how the power dynamics and policies change to regulate the temporary labour migration regimes in Nepal.

This research adds to the burgeoning literature on migration governance by showing the importance of looking beyond the government’s role in migration governance. Migration is supported and governed by the interaction of many actors in the sector and understanding the nuances of the interactions and power dynamics between the network actors and its effects on migration policies is key to unpack the regulation of temporariness for migrant workers. The role and regulation of private sector and of civil society actors is also vital as they are key players in the migration industry that support migrant workers find and prepare for jobs abroad. All actors in the migration network need to remain vigilant to ensure that the rights and welfare of migrant workers remains at the forefront.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adam, Silke, and Hanspeter Kriesi. 2007. “The Network Approach.” In Theories of Public Policy, edited by Paul A. Sabatier, 129–154. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Adhikari, Jagannath, and Ganesh Gurung. 2011. Foreign Employment, Remittance and Its Contribution to the Economy of Nepal. Kathmandu: Ministry of Labour and Transport Management and IOM.

- Agunias, Dovelyn R. 2013. What We Know About Regulating the Recruitment of Migrant Workers. Washington, D.C: Migration Policy Institute. MPI Policy Brief.

- Amnesty International. 2017. Turning People into Profits: Abusive Recruitment, Trafficking and Forced Labour of Nepali Migrant Workers.

- Arnold, Tom. 2021. “Remittances to Developing Nations Resilient in 2020 -World Bank.” Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/health-coronavirus-remittances-int-idUSKBN2CT22L.

- Atkinson, Michael M., and William D. Coleman. 1989. “Strong States and Weak States: Sectoral Policy Networks in Advanced Capitalist Economies.” British Journal of Political Science 19 (01): 47–67.

- Baumgartner, Frank R., and Bryan D. Jones. 1993. Agendas and Instability in American Politics. 1st ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bettin, Giulia, Andrea Presbitero, and Nikola Spatafora. 2014. “Remittances and Vulnerability in Developing Countries.” . IMF Working Paper 14/13.

- Betts, Alexander. 2011. “The Global Governance of Migration and the Role of Trans-Regionalism.” In Multilayered Migration Governance The Promise of Partnership, edited by Rahel Kunz, Sandra Lavenex, and Marion Panizzon, 43–65. New York: Routledge.

- Betts, Alexander. 2012. Global Migration Governance. Reprint Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Blanco, Ismael, Vivien Lowndes, and Lawrence Pratchett. 2011. “Policy Networks and Governance Networks: Towards Greater Conceptual Clarity.” Political Studies Review 9 (3): 297–308.

- Carling, J., and F. Collins. 2017. “Aspiration, Desire and Drivers of Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 909–926.

- Carling, J., and K. Schewel. 2018. “Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 945–963.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. 2011. “Nepal Living Standard Survey 2010/11.” Accessed February 16, 2015. http://cbs.gov.np/?p = 184.

- Daugbjerg, Carsten, and David Marsh. 1998. “Explaining Policy Outcomes: Integrating the Policy Network Approach with Macro-Level and Micro-Level Analysis.” In Comparing Policy Networks, edited by David Marsh, 195–207. England: Open University Press.

- Deshingkar, Priya. 2019. “The Making and Unmaking of Precarious, Ideal Subjects – Migration Brokerage in the Global South.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (14): 2638–2654.

- Encinas-Franco, Jean. 2013. “The Language of Labor Export in Political Discourse: ‘Modern-Day Heroism’ and Constructions of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs).” Philippine Political Science Journal 34 (1): 97–112.

- Foley, Laura, and Nicola Piper. 2021. “Returning Home Empty Handed: Examining How COVID-19 Exacerbates the Non-Payment of Temporary Migrant Workers’ Wages.” Global Social Policy 21 (3): 468–489.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, Thomas, and Ninna Nyberg-Sorensen, eds. 2013. The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration. London: Routledge.

- Garip, Filiz, and Asad L. Asad. 2016. “Network Effects in Mexico–U.S. Migration: Disentangling the Underlying Social Mechanisms.” American Behavioral Scientist 60 (10): 1168–1193.

- Ghosh, Bimal. 2000. Managing Migration. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Grugel, Jean, and Nicola Piper. 2007. Critical Perspectives on Global Governance: Rights and Regulation in Governing Regimes. London: Routledge.

- Haug, Sonja. 2008. “Migration Networks and Migration Decision-Making.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (4): 585–605.

- Jones, Harry, and Yurendra Basnett. 2013. Foreign Employment and Inclusive Growth in Nepal: What Can Be Done to Improve Impacts for the People and the Country? ODI.

- Kandel, W., and Douglas S Massey. 2002. “The Culture of Mexican Migration: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis.” Social Forces 80 (3): 981–1004.

- Kenis, Patrick, and Volker Schneider. 1991. “Policy Networks and Policy Analysis: Scrutinizing a New Analytical Toolbox, edited by Policy Networks: Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Considerations, edited by B. Marin and R. Mayntz, 25–59. Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

- Kern, Alice, and Ulrike Müller-Boker. 2015. “The Middle Space of Migration: A Case Study on Brokerage and Recruitment Agencies in Nepal.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 65: 158–169.

- Kickert, Walter J. M., Erik-Hans Klijn, and Joop F. M. Koppenjan, eds. 1997. Managing Complex Networks: Strategies for the Public Sector. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Klekowski von Koppenfels, Amanda. 2001. “The Role of Regional Consultative Processes in Managing International Migration.”.

- Knoke, David, Franz Urban Pappi, Jeffrey Broadbent, and Yutaka Tsujinaka. 1996. Comparing Policy Networks: Labor Politics in the U.S., Germany, and Japan. First Edition Edition. Cambridge England . New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Koslowski, Rey, ed. 2011. Global Mobility Regimes. 1st ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kriesi, Hanspeter, Silke Adam, and Margit Jochum. 2006. “Comparative Analysis of Policy Networks in Western Europe.” Journal of European Public Policy 13 (3): 341–361.

- Kunz, Rahel, Sandra Lavenex, and Marion Panizzon, eds. 2012. Multilayered Migration Governance: The Promise of Partnership. Reprint ed. Abingdon, OX: Routledge.

- Lewis, H., P. Dwyer, S. Hodkinson, and L. Waite. 2015. “Hyper-Precarious Lives: Migrants, Work and Forced Labour in the Global North Progress in Human Geography.” Progress in Human Geography 39 (5): 580–600.

- Liu, Mao-Mei. 2013. “Migrant Networks and International Migration: Testing Weak Ties.” Demography 50 (4): 1243–1277.

- Mandal, Chandan. 2017. “‘Free Visa Free Ticket’ Scheme a Dud: Panel.” The Kathmandu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2017/08/10/free-visa-free-ticket-scheme-a-dud-panel.

- Mandal, Chandan. 2019a. “Foreign Employment Department Swings into Action against Fraud Cases.” Kathmandu Post. https://tkpo.st/37yjEv1.

- Mandal, Chandan. 2019b. “He Was One of the Few Ministers Who Delivered. Then the Prime Minister Sacked Him.” Kathmandu Post. https://tkpo.st/37Dkbf0.

- Mandal, Chandan. 2019c. “Supreme Court Issues Directive to Government to Effectively Implement ‘Free-Visa, Free-Ticket’ Scheme.” The Kathmandu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/national/2019/01/04/enforce-free-visa-free-ticket-scheme.

- Marsh, David, and R. A. W. Rhodes, eds. 1992. Policy Networks in British Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Martin, Susan F. 2015. “International Migration and Global Governance.” Global Summitry 1 (1): 64–83.

- Martin, Philip, Manolo Abella, and Christiane Kuptsch. 2006a. Managing Labor Migration in the Twenty-First Century. New Haven: Yale UP.

- Martin, Philip L., Susan F. Martin, and Patrick Weil. 2006b. Managing Migration: The Promise of Cooperation. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- McGuire, Michael. 2006. “Collaborative Public Management: Assessing What We Know and How We Know It.” Public Administration Review 66: 33–43.

- Ministry of Labour and Employment. 2014. “Labor Migration for Employment: A Status Report for Nepal: 2013/14.”.

- Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security. 2020. Nepal Labour Migration Report 2020. Kathmandu.

- Mukherjee, Ishani. 2013. “Prioritizing Sustainability: Coalitions, Learning and Change Surrounding Biodiesel Policy Instruments in Indonesia.” NUS.

- MyRepublica. 2019. “Government Tightening Leash on Manpower Agencies.” My Republica. https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/govt-tightening-leash-on-manpower-agencies/.

- MyRepublica. 2020. “Raids on Four Manpower Agencies Expose ‘syndicate ‘ Supplying Workers to Qatar.” My Republica. https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/raids-of-four-manpower-agencies-expose-syndicate-to-supply-workers-to-qatar/.

- Nepali Times. 2019. “Blood, Sweat and Tears.” Nepali Times. https://www.nepalitimes.com/editorial/blood-sweat-and-tears/.

- News24 hours. 2016. “Fraudulent Manpower Agencies under Government Vigilance.” News24 hours. https://nepal24 hours.com/fraudulent-manpower-agencies-under-government-vigilance/.

- Panday, Jagdishor. 2019. “Opening Manpower Agencies to Cost a Fortune.” The Himalayan Times. https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/opening-manpower-agencies-to-cost-a-fortune.

- Paoletti, Sarah, Eleanor Taylor-Nicholson, Bandita Sijapati, and Bassina Farbenblum. 2014. Migrant Workers’ Access to Justice at Home: Nepal. New York: Open Society Foundations.

- Poros, Maritsa V. 2001. “The Role of Migrant Networks in Linking Local Labour Markets: The Case of Asian Indian Migration to New York and London.” Global Networks 1 (3): 243–260.

- Rai, Om Astha. 2015. “Who Is against Zero-Cost Migration and Why?” http://nepalitimes.com/article/nation/manpower-agencies-of-Nepal-are-the-ones-against-zero-cost-migration-policy,2402.

- Ratha, Dilip, Sanket Mohapatra, and Ani Silwal. 2010. Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: World Bank Publications.

- Rhodes, R. a W. 1985. Power-Dependence, Policy Communities and Intergovernmental Networks. Colchester: Department of Government, University of Essex.

- Ryan, Louise, Rosemary Sales, Mary Tilki, and Bernadetta Siara. 2008. “Social Networks, Social Support and Social Capital: The Experiences of Recent Polish Migrants in London.” Sociology 42 (4): 672–690.

- Sabatier, Paul A., and Hank C. Jenkins-Smith. 1999. “The Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Assessment.” In Theories of Public Policy, edited by Paul A. Sabatier, 117–168. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Sapkota, Chandan. 2011. Large-Scale Migration and Remittance in Nepal: Issues, Challenges and Opportunities. Kathmandu: World Bank.

- Shivakoti, R. 2019. “When Disaster Hits Home: Diaspora Engagement After Disasters.” Migration and Development 8 (3): 338–354.

- Shrestha, Dambar Krishna. 2015. “Mission Unaccomplished.” Nepali Times.

- Sijapati, Bandita, and Himalaya Kharel. 2016. “Free-Visa, Free-Ticket.” The Kathmandu Post. https://kathmandupost.com/miscellaneous/2016/05/02/free-visa-free-ticket.

- Sijapati, Bandita, and Amrita Limbu. 2012. Governing Labour Migration in Nepal: An Analysis of Existing Policies and Institutional Mechanisms. Kathmandu: Himal Books.

- Spitzer, Denise L., and Nicola Piper. 2014. “Retrenched and Returned: Filipino Migrant Workers During Times of Crisis.” Sociology 48 (5): 1007–1023.

- Tabuga, Aubrey D. 2021. “How Does Outmigration Behaviour Cascade Within the Community of Origin? A Socio-Historical Approach to Migrant Network Analysis Using the Philippines Case.” International Migration. https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/doi/10.1111/imig.12855.

- Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2019. “The Migration Archipelago: Social Navigation and Migrant Agency.” International Migration 57 (1): 5–19.

- Triandafyllidou, Anna. 2020. “Decentering the Study of Migration Governance: A Radical View.” Geopolitics. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2020.1839052.

- Triandafyllidou, A. 2022. “Temporary Migration: Category of Analysis or Category of Practice?” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (16): 3847–3859. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2028350.

- Van Waarden, Frans. 1992. “Dimensions and Types of Policy Networks.” European Journal of Political Research 21 (1–2): 29–52.

- Wee, Kellynn, Charmian Goh, and Brenda S. A. Yeoh. 2019. “Chutes-and-Ladders: The Migration Industry, Conditionality, and the Production of Precarity among Migrant Domestic Workers in Singapore.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (14): 2672–2688. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1528099.

- Wickramasekara, Piyasiri. 2011. Circular Migration: A Triple Win or a Dead End. Geneva: International Labor Organisation.

- Withers, Matt, Sophie Henderson, and Richa Shivakoti. 2021. “International Migration, Remittances and COVID-19: Economic Implications and Policy Options for South Asia.” Journal of Asian Public Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/17516234.2021.1880047.

- World Bank. 2020. COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens. Migration and Development Brief 32.

- Yang, Dean, and HwaJung Choi. 2007. “Are Remittances Insurance? Evidence from Rainfall Shocks in the Philippines.” The World Bank Economic Review 21 (2): 219–248.

- Yeoh, Brenda. 2020. Temporary Migration Regimes and Their Sustainability in Times of COVID-19. Geneva: IOM Think Pieces.