ABSTRACT

Resettlement of refugees in third countries has seen a growing intervention by various civil society actors in the last few years, starting from the Canadian experience. Also in Europe, these sponsorship schemes are developing, despite a general restriction of asylum policies. This paper will analyse a case of civil society's sponsorship, which has been developed in recent years by religious (Christian) institutions, first in Italy, then in other European countries (France, Belgium, Andorra, San Marino and recently Germany), in agreement with governments: what have been called ‘humanitarian corridors’. The paper will provide an evaluation of the project referred to arrivals from Ethiopia (more than 300 people), based on documents and interviews with key informants, volunteers and refugees. In particular, it will discuss the present outcomes of the project, together with its relationship with restrictive policies: how the cultural message of the project challenges borders closure for asylum-seekers. Studying such experience, this article also wants to discuss some general questions: What does this reception by CSOs have to do with a neoliberal vision of asylum and human rights? What are the potential benefits and the possible shortcomings of citizens’ and communities’ engagement in refugee reception?

Refugee studies have burgeoned in the last decades, following a growing interest in the issue by public opinion and political debate. Scholars have been interested especially in critically analysing restrictions in refugees’ reception (Zetter Citation2007; Agustín and Jørgensen Citation2019), illegalisation of asylum-seekers (Carrera et al. Citation2015), externalisation of European borders (Lavenex Citation2006), devolution of borders management and refugees’ protection to transit countries (Faist Citation2018), the emergence of key-sites of tension between asylum-seekers and authorities of receiving States, as the small Italian island of Lampedusa (Dines, Montagna, and Ruggero Citation2015; Giliberti and Queirolo Palmas Citation2021). The same humanitarian assistance has been deeply criticised, and NGOs have been placed by a stream of scholarship among the actors of an asylum regime which combines repression of borders crossing with some morsels of compassion (Agier Citation2011; Fassin Citation2005; Malkki Citation1996; Sözer Citation2020).

Less frequent is the reflection on possible solutions to the refugees’ issue, beyond a stream of studies on refugees’ ‘integration’ in receiving countries, mainly of the Global North (Ager and Strang Citation2008; Askins Citation2015; Suter Citation2021; van Dijk et al. Citation2021). The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), being the main institutional actor in this field, has repeatedly outlined the fact that more than 80% of international refugees are hosted in developing countries, especially the bordering ones, often with limited internal resources (UNHCR Citation2020, Citation2021). In order to suggest some possible ways out for refugees’ future, and counterbalancing the deep inequality in burden-sharing across the world, UNHCR has identified four durable solutions: local integration, voluntary return, resettlement in a new country and complementary pathways for admission to third countries.Footnote1 However, UNHCR’s evaluation is not optimistic: ‘As wars and conflicts dragged on, fewer refugees and internally displaced people were able to return home, countries accepted a limited number of refugees for resettlement and host countries struggled to integrate displaced populations’ (UNHCR Citation2020, 11).

Complementary pathways can also be sponsored by private entities (Kumin Citation2015): in fact, they can be conceived as a form of resettlement, through which refugees can settle in a third and safe country (Ahmad Ali, Zendo, and Somers Citation2021). In such framework, this paper will analyse a private sponsorship scheme which has been developed in recent years by Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), and precisely religious Christian institutions, first in Italy, then in other European countries (France, Belgium, Andorra, San Marino, and recently also Germany, through the program NesT: Pohlmann and Schwiertz Citation2020), in agreement with governments: what have been called ‘Humanitarian Corridors’. Through Humanitarian Corridors (HC), asylum-seekers precariously hosted in transit countries, can reach European countries in safe ways, through a ‘protected entry procedure’, present an asylum application there, be scattered across the country and then be received and assisted by local groups of volunteers, for at least one year (Ricci Citation2020). The legal basis of these humanitarian visas can be found in Article 25 of the Community Visa Code, which gives EU member states discretion to issue visas with limited territorial validity on humanitarian groundsFootnote2 (Oomen et al. Citation2021).

Studying such experience, this paper also wants to discuss some general questions: How can researchers evaluate the involvement of the civil society in the governance of asylum, against a reluctance (at best) of States complying with human rights protection? What does this engagement in asylum policies by CSOs have to do with a neoliberal vision of asylum and human rights? In other terms, the engagement by CSOs in this contentious field does not exonerate governments to fulfil their obligations to protect human rights, namely to provide refugees’ protection? What are the potential benefits and the possible shortcomings of citizens’ and communities’ engagement in asylum-seekers’ admission and reception?

1. The involvement of ‘humanitarian’ civil society in asylum policies

In many countries, it is very common to observe that asylum-seekers, despite many obstacles, can receive help, access public services, have a voice in the public debate or survive even if their asylum applications have been rejected. This survival depends in many cases on the support that the asylum-seekers and other migrants receive from CSOs and groups of host country’s citizens (Ataç, Schütze, and Reitter Citation2020; Hagan Citation2008; Maestri and Monforte Citation2020).

However, this trend raises several issues. Private support to asylum-seekers can be seen as an expression of ‘humanitarianism’ (Sandri Citation2018; Schwiertz and Schwenken Citation2020; Vandevoordt and Verschraegen Citation2019), even if (maybe) different from large-scale and professional humanitarianism (Rozakou Citation2017). Humanitarianism can have different meanings, varying from international help to private donations, but it has often been treated as a uniform category in academic scholarship. Ticktin (Citation2014) has highlighted the shift from the first period of alliance between scholars and the moral project of humanitarianism to a second period, starting in the 2000s, of prevailing criticism of humanitarianism and its unintended consequences: ‘critiques that often suggested that humanitarianism should be entirely abandoned or dismantled’ (277). More recently, according to Ticktin, the third wave of studies has conducted ‘more cautious, ethnographic examinations and descriptions’ of the ‘complexities, limits, and boundaries’ of humanitarianism (283).

A crucial point in this debate concerns the link between ‘humanitarian’ activities developed by CSOs and state policies. The objections refer mainly to humanitarian actors’ alleged complicity with policies that aim to prevent the arrival of asylum-seekers or to restrict their access to refugee status: they cooperate in ‘managing the undesirables’ (Agier Citation2011). Humanitarianism, in this vision, would be the other side of the closure, softening its consequences and saving some cases on the ground of victimhood (Fassin Citation2005). Again, Fassin talks of ‘the three pillars of governmentality, that is, economy, police, and humanitarianism’ (Fassin Citation2011, 221).

According to this perspective, ‘humanitarian action thus forms part and parcel of the governance of migration’ (Fleischmann Citation2017, 57). Ticktin (Citation2011) in turn stigmatises the ‘antipolitics of care’, because humanitarian agencies, giving up political intervention, strengthen repressive migration policies and confirm global inequalities. Essentially, sentiments and moral engagement would take the place of justice and political engagement. The ‘humanitarian government process’, in global terms, tends to substitute a politics of rights with ethics of suffering and compassion, through the deployment of moral sentiments in contemporary politics (Fassin Citation2012). Moreover, the ‘humanitarian reason’ involves a tension between inequality and solidarity, between domination and assistance. According to this approach, compassion is always asymmetrical, without any possibility of reciprocity. Furthermore, under the label of ‘humanitarian government’, governmental and non-governmental initiatives are categorised as sharing the common aim of managing populations that face violence and suffering (Fassin Citation2012, 5). Similar objections have been addressed also against private sponsorship schemes (Ritchie Citation2018).

There would be then an inherent link between humanitarian action and the dominant political ideology of Western societies, namely a neoliberal approach which aims at imposing a ‘mobility regime’ (Glick Schiller and Salazar Citation2013; Faist Citation2019) which excludes in principle immigrants from the Global South, except economic and professional elites. According to Sözer (Citation2020, 2164), ‘contemporary humanitarianism is a product, a symptom and a suggested solution to neo-liberal political and economic transformation: it is neo-liberal humanitarianism’.

We think that it is necessary to distinguish more carefully various forms of ‘humanitarian’ action, various types of actors involved, and also various types of support to asylum-seekers. Clearly, each of these forms can be critically analysed, but without forgetting the wider context: a polarisation of public opinion and of political discussion (Rea et al. Citation2019), in which the voice of pro-human rights actors and their capacity for mobilisation deserve recognition, in contrast with anti-refugee claims. Askins (Citation2015) has stated that ‘banal, embodied activities’ of care can be outlined as ‘implicit activisms’ and ‘acts or micropolitics’; while Kirsch (Citation2016) has defined volunteering as ‘politics by other means’. In the same vein, Artero has argued (Citation2019, 158) that ‘volunteering functioned as a micropolitical practice: it allowed volunteers to be outraged by structural injustices, sympathise with migrants and (…) engage in outspoken forms of dissent such as lobbying, advocacy and public demonstration’. Humanitarian corridors, in a similar way, can be conceived as an expression of ‘debordering solidarity’ (Ambrosini Citation2021). They share the same vision, and often the same human and organisational resources, of many activities in favour of migrants and asylum-seekers which imply an objection against borders (Van Selm Citation2020): either external (rescuing people from the sea, against border closure), or internal, providing various types of help to people who are not authorised to remain on the territory, against removals and bureaucratic obstructions (Artero and Fontanari Citation2021). Although the proponents do not take an overt political position, they contest policies of asylum and borders in practice. It is what Fleischmann (Citation2020, 14) suggests, defining solidarity towards refugees as a

transformative relationship that is forged between established residents and newcomers in migration societies, one that creates collectivity across or in spite of differences. Such relationships of solidarity hold the potential to invent new ways of relating that challenge the divide between citizens and non-citizens.

The concept of debordering solidarity is then close to the concept of ‘inclusive solidarity’ introduced by Schwiertz and Schwenken (Citation2020). As they argue, ‘civil society initiatives acting in solidarity with those considered outside the nation have a crucial function in challenging social exclusion’ (405). We add, they challenge the establishment of harsh borders and policies trying to deny asylum-seekers’ access to the national territory. Clearly, they cannot erase borders, or reverse State policies, but they have made possible the reception of thousands of asylum-seekers, questioning political and cultural borders in fact. Triggering local acceptance and developing mutual relationships between native residents and foreign newcomers, they have demonstrated that asylum-seekers are not a threat to receiving societies.

In such a way, they become part of the ‘battleground’ of migration policies: a concept focusing on the involvement of various subjects, with their interests, beliefs and values, in the practical governance of immigration, at the international, national and local levels (Ambrosini Citation2021; Campomori and Ambrosini Citation2020; Dimitriadis et al. Citation2021). Practical help, and even more the introduction of a new legal way for the reception of asylum-seekers, is imbued with political meaning, even when it is not declared or acknowledged (Schwiertz and Schwenken Citation2020). The notion of debordering solidarity is intended to grasp the tension between these actions of support and policies which seek to reaffirm national sovereignty through stricter asylum and migration measures. In this case, however, as Oomen et al. (Citation2021, 22) observe, ‘national borders are not necessarily torn down by directly confronting and defying the central government or the established legal and policy frameworks, but also through a process of negotiation, collaboration, and use of already available legal tools’.

2. Resettlement and complementary pathways as a response to the ‘refugee crisis’: the engagement of non-public sponsors

The engagement of CSOs in private sponsorship schemes can be seen as an emerging feature of complementary pathways, which are seen by some authors as a form of resettlement (Kumin Citation2015; Pohlmann and Schwiertz Citation2020). While they can take different forms, private sponsorships hold two main features. First, an NGO, a group of citizens, an organisation or even an individual assumes an engagement for providing economic and social support to a resettled individual or family for a period, usually one year, or until the refugee becomes self-sufficient. Second, the private sponsors, if they want, usually hold the right to choose the person or people whose resettlement they are willing to support (Kumin Citation2015).

The first country to launch a private sponsorship scheme was Canada in 1978, implementing a passage of the Immigration Act of 1976, and for several years Canada remained the only country with such a programme. Since then, some 300,000 sponsored refugees were resettled in Canada through private sponsorships (Macklin et al. Citation2020). It is worth observing that private sponsorships are additional to the government’s resettlement programme. They are regulated by an annual target range, in relation to the government’s capacity to process applications, rather than to sponsors’ availability (Kumin Citation2015).

Canadian sponsors belong to three categories: sponsorship agreement holders (SAHs), which establish formal agreements with the government; groups of five or more Canadian citizens, or permanent residents (Caritas Italiana Citation2019); community sponsors, associations or other organisations that are active in local communities in which refugees will settle. Also, corporations or other businesses can become sponsors, but it occurs rarely. Several city governments, on the contrary, have supported sponsorship schemes, providing funds or making services available to refugees (Kumin Citation2015).

In 2013, furthermore, a ‘blended program’ has been introduced (Ahmad Ali, Zendo, and Somers Citation2021), through which responsibilities are shared between the government and a private sponsor: such programme together with full private sponsorships has contributed to more than double the number of refugees admitted in the country.Footnote3

In 2012, Australia set up its own pilot private/community sponsorship programme, which was transformed in 2015 into a Community Support Program and made a regular component of refugee reception in the country (Kumin Citation2015).

Until 2013, there was no scheme of private sponsorship in the EU. Only with the humanitarian crisis in Syria, some initiatives started to develop: 15 out of 16 federal states (Länder) in Germany have adopted private sponsorship arrangements, while Ireland and Switzerland briefly introduced private sponsorship as a way to reunify Syrian refugees families (Kumin Citation2015). These schemes allowed the entrance of more than 20,000 people in Germany, especially Syrian families hit by the civil war. Costs and length of support required to sponsors (all travel costs, board and lodging, access to social services) have requested some revisions to the programme, consisting in stronger public support (for instance, for health care) and a reduction of the time length of the sponsors’ guarantee (Pohlmann and Schwiertz Citation2020).

France and Austria have introduced sponsorship programmes for victims of Middle East conflicts as well. In particular, the French programme originally addressed persecuted religious minorities from Iraq and was later extended to Syrian citizens of all religious denominations fleeing to neighbouring countries (Caritas italiana Citation2019).

In the UK, a Community Sponsorship scheme was introduced in 2016. By the end of 2018, more than 200 refugees had arrived in the UK, sponsored by some 140 groups (Van Selm Citation2020). Some literature has summarised the main motives to sponsor refugees’ arrival and settlement. According to Sponsor Refugees (Citation2019), private sponsorships bring multiple benefits: at a cultural and political levels, they support a wider acceptance of refugees; at a social level, they involve citizens and local communities (Ricci Citation2020; Oomen et al. Citation2021), reinforcing social capital. Furthermore, they improve beneficiaries’ capacity to arrive in safe ways and to integrate into the receiving society (Ahmad Ali, Zendo, and Somers Citation2021). Similar expectations have informed the proposal of ‘Humanitarian Corridors’ in Italy, to whom now we will direct our attention.

3. Humanitarian corridors in Italy

In Italy, the reception of asylum-seekers coming mainly from the African shores has represented an issue of the public debate since the ‘90 of the last century, but it has become a paramount political question since 2014–2015, especially after the shipwreck of October 2013 near the coast of the small island of Lampedusa. Following the growth of arrivals and stronger involvement of the country as the provider of assistance to the newcomers, a wave of refusal and protest has risen at the national and local levels, especially in the towns and villages in which the government decided to establish a reception facility (Ambrosini Citation2018). Anti-establishment and right-wing parties exploited and fostered these sentiments (Castelli Gattinara Citation2017). In a period of economic difficulty and high unemployment, it was quite easy to direct the anger of many people against asylum-seekers, NGOs rescuing lives in the Mediterranean, and the government which allegedly welcomed them. The same centre-left government, which at first organised a campaign of search and rescue in the Mediterranean (‘Mare Nostrum’) and cooperated with NGOs, changed its political line: in 2017, the government started to impose stricter rules and legal obstacles to NGOs and signed an agreement with the Libyan government and local forces, to stop the departure of vessels from Libyan shores and to reconduct to Libya people who managed to leave (Marchetti Citation2020). This choice did not change the political destiny of the centre-left government: in 2018, the anti-establishment parties won the national elections and created the first populist government in the EU.

In this difficult situation, the search for alternative solutions to the so-called ‘refugee crisis’ involved many pro-immigrant actors from the Italian civil society. In Italy, humanitarian corridors have been promoted by some religious actors (Catholic and Protestant, see below) through an agreement with the national government, in particular the Ministry of Home Affairs and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Garofalo Citation2017; Gois and Falchi Citation2017; Trotta Citation2017; Albanese and Tardis Citation2020). The HC approach provides complementary legal and safe pathways and international protection for vulnerable asylum-seekers. The first and more relevant experience regards Syrian refugees coming from Lebanon, through which about 2,000 people have been admitted in Italy thus far. The promoters were the Waldensian Church, the Italian Federation of Evangelical Churches and the Catholic Community of Saint Egidio.Footnote4

The second corridor was promoted only by Catholic institutions (The Italian Bishops Conference, Caritas Italy, Migrantes and the Community of Saint Egidio), and has sponsored the arrival of about 500 refugees coming from Ethiopia and originating from Eritrea and other neighbouring countries. This experience will be the topic of this paper. A third corridor has been more recently created in Niger, again by the same Catholic institutions in cooperation with UNHCR, and it is taking charge of about 50 refugees.Footnote5 Since 2019, University Corridors for Refugees (UNICORE) have offered refugee students to pursue higher education in 24 Italian Universities.

Refugees have been selected in cooperation with local NGOs, on the basis mainly of vulnerability and family charges, they were allowed to reach Italy with a special visa, and they could present their asylum application after arrival.Footnote6 All were accepted. Refugees were received in a scattered way, in local communities across the country, with some concentrations for the first corridor in the region of Piedmont where the Waldensian church is historically settled. Usually, one or two families were hosted in local settings, through the support of religious institutions, without any public expenditure. Volunteers were made responsible for their accommodation and for supporting their integration into local societies: learning the Italian language, knowing the territory, accessing social services, helping children at school, searching for employment or vocational training, creating a network of acquaintances. In the case of the corridor from Ethiopia, the project suggested in particular the involvement of a local family as ‘mentor’ for newcomers, with the task of becoming the first point of reference for them, providing useful information, orientation to local services and social and emotional support. The Italian project resonates with the British experience, where

the main role of sponsors (…) is that of facilitators – a bridge offering guidance as well as some material assistance in the earliest days, and in some ways mentors, with a changing relationship over the course of time, as the refugees start to both integrate in wider society and become increasingly independent. (Van Selm Citation2020, 193)

In the following section, based on fieldwork, we discuss basically four questions. First of all, how do local communities take care of refugees? Second, is the host community able to adequately take care of the most vulnerable people? Third, is dispersion through the country the best solution, and in particular, are small villages the right place to host refugee families? Fourth, have refugees settled in Italy, or have they moved to other EU countries? And in case, have they found employment, being the main way achieving autonomy and recognition?

4. The field study: the 2017–2019 humanitarian corridor from Ethiopia

In January 2017, the Italian Bishops’ Conference (IBC) and three Faith-Based Organisations – Caritas Italy, Migrantes, and Community of Saint Egidio – signed a protocol with the Italian Government to introduce safe passage and resettlement for Eritreans, South Sudanese and Somalis. Within one year, the project provided 498 visas for vulnerable persons who were previously hosted in refugees’ camps in Ethiopia, having abandoned, often for reasons of conflict or persecution, their original countries. The project depends entirely upon private funding. The IBC contributes 4 million Euros for the entire project, including 15 Euros per refugee per day for one year.

The most vulnerable people were selected in cooperation with the UNHCR, the Ethiopian government’s Agency for Refugee and Returnee Affairs (ARRA), and different grassroots organisations, identifying vulnerable persons based on an UNHCR resettlement refugees screening tool (which assesses vulnerability by age, gender, health, welfare, and physical safety: UNHCR Citation2016). Caritas Italy and Saint Egidio collaborated in the selection. Multiple interviews were held to evaluate needs, identify priority levels, verify documentation, do health screenings and explain the integration process. After completing the assessment, names were submitted to the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Interior. Selected asylum-seekers were summoned to the Italian Embassy for biometric identification, and national and European authorisations. Thereafter, the Italian Embassy issued a temporary visa, granting legal travel to Italy.

Before departure, Caritas Italy provides selected beneficiaries with a pre-departure orientation focusing on cultural and socio-economic aspects of Italian society.

Once in Italy, selected beneficiaries applied for international protection; and social workers and volunteers introduced them to the host communities, where they formalised their asylum applications. After these procedures, they were all granted refugee status. Their asylum permit is valid for five years and can be renewed on expiry.

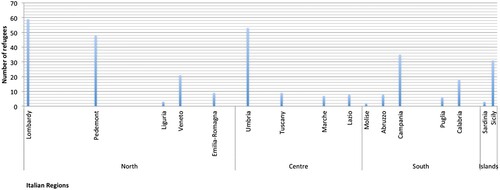

This section presents findings from the first two years of a five-year study that explores the experience of refugees and host communities, hosted in Italy through the 2017–2019 HC program by Caritas local communities, and not by Saint Egidio (318 of the 498), in 45 host communities of 16 Italian’s regions (). Among these 318 refugees, 281 were Eritreans, 15 Somali and 22 Sud Sudanese; 48 were single adults (10 female and 38 males); 66 family units (124 adults, 67 female and 57 male and 146 minors).

The substantially qualitative method of analysis engages different tools: field data collection and observation, in-depth qualitative interviews and semi-structured group discussions. Field research involved three trips to Ethiopia, to meet asylum-seekers prior to departure, one-to-three days visits to the 45 host communities in Italy during the first year of hosting and participation in Caritas national training sessions. For ongoing qualitative monitoring, a research assistant has interacted with social workers every three months. Frequent communication was also maintained with approximately 30 refugees via social networking groups over the years. During the first year of research (April 2018 to June 2019), more than 350 semi-structured interviews and 50 semi-structured group discussions were conducted in the 45 locations. Host communities include Caritas social workers, local volunteers, mentor families and in some cases the whole local community. Interviews included: 41 Caritas directors coordinators, 22 bishops and priests, 5 employers, 6 school teachers, 3 mayors, 1 city council administrator and 121 adult refugees. The group discussion interviews, which included 150 volunteers (at least 1 for each location), 25 mentor families and 60 social workers were adapted to individuals’ respective roles.

Interviews were conducted three to four months after refugees’ arrival to Italy, in Caritas offices, refugees’ homes and schools, and in accordance with guidelines of the university’s ethical review board. Interviews lasted 20 min–1 h and were conducted in Italian or English; a cultural mediator translated for refugees who spoke neither Italian nor English.

Interviews with refugees covered themes about their experience in the initial year. All interviews were recorded and transcribed to ensure anonymity and informed consent. Themes, codes and sub-codes were identified with the research hypothesis, and thematic data analysis was conducted through an iterative process. We also collected the number and characteristics of refugees who remained in or departed from Italy.

There has been a cooperation between Caritas and the public administration (both at the national and local levels); as a result, many of the refugees who arrived through the HC obtained interview appointments with the ‘Commission’ (Prefettura) earlier and faster than other asylum-seekers. In the majority of the hosting locations, the relationship with local municipalities has been collaborative. Nevertheless, the efficiency of State offices differed substantially. In a few locations, beneficiaries received refugee status after a year-long wait, some after two years, also for mistakes made by some local Caritas.

4.1. The key role of the local community in taking care of refugees

Preparation for host communities began several months prior to asylum-seekers’ arrival and included workshops about arriving people’s socio-cultural backgrounds and vulnerabilities.

Caritas Italy strived to ensure that each immigrant is placed in a host community whose facilities and resources and the presence of volunteers align with the individual’s vulnerabilities, needs and skills. Caritas Italy tried to select the locations matching the needs of refugees with possibilities of adequate housing, access to education and health facilities, language learning and opportunities of work.

In many hosting communities, the HC project is facilitated by local volunteers often coordinated by local mentor families who act as a point of reference in the life of the newcomers. Local mentor families and volunteers do not receive remuneration: they cultivate a personal relationship with refugees, which is a key element in contributing to the development of a solid network.

The support by the host community culminates in the refugees’ eventual ability to gain freedom and capacity independently from the assistance of Caritas social workers and volunteers. The principal aim of Caritas Italy and the local Caritas is to accompany HC’s refugees to their autonomy and integration into Italian society. The HC project has offered local communities the opportunity to engage personally with refugees. Snyder (Citation2012, 180) talks about the concept of hospitality and states that it ‘is rooted in concrete, one-to-one, personal encounters. It is these encounters which facilitate the development of mutually life-giving relationships’.

One 35-year-old Eritrean man hosted in the Emilia–Romagna region explained:

We are very pleased that someone is interested, that someone looks at our present and our state, how we live, and that nobody has abandoned us, it is a sign of closeness […] when we walked in this territory […] the closeness of the town, of the families, of the people […] today has given us back all what we have lost, that is, the sense of family. We feel at home as we were in our country.

From the first day we arrived here, in this house, we were welcomed by all the people of N. [City], in particular also by the municipality itself, there was the council member that day; the people of this place here do it not for work … they do it for love. For example [they] call you on Saturdays and Sundays and say ‘What are you missing? How are you? ‘ and he [social worker] introduces you to his family, he hosts at his house, he introduces you to his children, he goes further, and this creates a family for you. We have seen all of this. Then even when we also call. P. [social worker] he is very clear, he is always there 24 hours a day, always, if something is possible he does it immediately, if it's something he can't do, he says ‘I'll find out and let you know’. So the people are next to us, they call us, they are very interested in us.

volunteers who are good people came to pick me up with their car, they took me there where I picked fruit, they accompanied me, they also came to pick me up in the evening, these people gave to me a great joy, a great help.

In two different villages in Tuscany, refugees expressed a positive judgement about their experience:

Now we are in P. and the community … they [the people] are very socializing, they are very comforting us, they are doing everything to help us. By the way, the village is very comfortable for us.

We are happy, very much. P. is small but very beautiful. Very good.I. Is not too small? R.. I think P. is beautiful, it is better to live, no problem. Where we come from there were more problems, we don’t want that anymore, we accept that we live in P., it is very good for us. If we can find a job … For M. (child) is very good to live here, in a big town it would be much more difficult, it is better to live out of a city … ., he can go out, no cars [no danger], it is good for him, also for us to take the stroller out.. It is very nice.

One day this summer, I took them [the refugees] to the beach with my mom and my daughter. And from that day on, [the refugees] always ask me how they [my parents] are. They care about them. It's like we forged a stronger bond. We are a bigger family.

This can be seen as the micro-social aspect of debordering solidarity: native common people in hundreds of local settings discovered that refugees were not a threat to the social order; actually, they could develop reciprocal bonds, giving and receiving welcome. These micro-level encounters, displaying acceptance and solidarity towards people not belonging to the national community, have a wider, although often implicit, political dimension: they rewrite scripts referred to boundaries, membership and proximity (Sandri Citation2018; Schwiertz and Schwenken Citation2020).

4.2. Remote resettlement locations and socio-cultural clashes

The HC project involves local communities often located in remote villages or small cities. This is because distributing the responsibility of the integration process within the whole national territory is considered politically and socially more acceptable (Genovese, Belgioioso, and Kern Citation2017). However, our findings show that often refugees placed in remote locations suffer due to isolation and a lack of job opportunities. For instance, a South Sudanese young woman explained the difficulties of leaving in a small remote area (40 inhabitants and 18 kilometres from the main town in the Umbria region):

I came to Italy to change my life. But I don’t know […] the place I’m here now, S. [small town] is not comfortable for us. It’s too far from people, there are no people in this place. We must learn to speak Italian, if you are speaking Italian everything will be okay. But here now, it’s too boring [and] no one can speak with you.

The important thing is to find a job […] then you can grow, but it doesn't have to be a place like this, where you don't see anyone, it has to be in a city where there is growth and with other people.

During the first year, Italian language acquisition, often a prerequisite to finding a job, is hard for the majority of the refugees. Four months after settling, one 42-year-old Eritrean woman reflected,

There is always the problem of the language, if one knows the language [one] can communicate, do things. [… .] I started writing and reading a bit, but I don't know anything, the meaning, so this is my difficulty.

At the beginning there was the mistake of wanting to accelerate their insertion into our habits, especially hygienic habits. She [refugee] did not understand what the sheets were, how they were used, how they were put in bed.

Even if here it is good, […] I see my future re-joined with my relatives and family members. […] having two little girls […] I can't even go to school; the times are tight.

Cultural adaptation in many hosting communities was not at first seen as an important aspect of the welcoming phase.

4.3. The challenge of finding employment to gain autonomy

Most refugees recognise their need to secure work to gain autonomy, as one of them declared a few months after his arrival in a city in the Abruzzo region:

In my future I see that I will be a person who lives by his work. I have a profession. I have always worked as a driver and therefore I would like in some way to transform my knowledge and this competence and to adapt it to Italy.

One refugee explained, ‘[I need] a job, because in order to live I need it, we can't just wait for the things they give to us, we want to work and live properly.’ Some refugees, usually the less educated, would accept any job, but job opportunities are scarce and not easy to find in many areas located in less developed regions of Italy (especially in the Southern part of Italy) or small towns without a good local network. Some other refugees are too vulnerable or not willing, due to personal circumstances, to accept any employment. Beneficiaries under the age of 30 do better in terms of learning the language and finding employment.

The location where refugees are hosted is also important and linked to the development of the area. Higher probabilities of employment (before the period of COVID-19) were found as temporary jobs in touristic areas, even in small towns, in hotels and restaurants, during the tourist season. On the contrary, many unemployed refugees experience despair. One volunteer described a refugee who ‘feels the emptiness of not working’. A refugee reflected, ‘If we have work, we can live forever. This is our concern’. Another added, ‘If the contract [with Caritas] finishes and I do not have a job […] If I have nothing, what can I do with the children?’ Another refugee reflected on the common expectation that Caritas would offer job-related training and help her secure employment: ‘We were told that we would learn Italian at school, we are doing this. But if I understood correctly, they told us that this year they [would have] taught us a job, but we have not seen it yet.’

Only six months after asylum-seekers’ arrival, Caritas social workers started to engage refugees in adequate training, internship or job opportunities. The most pro-active refugees found themselves a job; in some locations, the network and word-of-mouth of volunteers helped the process.

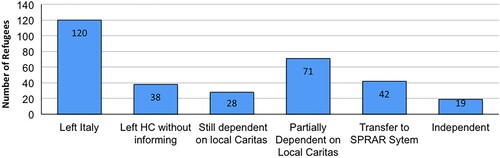

This difficulty in finding employment is one of the reasons why some refugees left the project early, sometimes before obtaining legal documents. Monitoring the refugees’ situation after three years from the beginning of the project (February 2021), it was found that 113 of 318 (35.53%) of the beneficiaries left Italy; 38 (11.9%) left without informing Caritas of their destination. Many are still dependent (28) on the local Caritas for housing and food, some are partially dependent on local Caritas (71) or the government system SAI (42), only 19 (6%) are fully independent (). Local Caritas acknowledged that twelve months of Caritas’ financial support are not sufficient to generate autonomy. Especially in the case of families with 7 or more members and adults with low levels of education or labour skills, reasonable financial support was felt to be needed far beyond the initial 12 months.

Furthermore, the pandemic COVID-19 and the lockdown had a strong impact on the Italian economy in 2020. Economic data released in May 2020 by the Italian Central Bank indicates that Italy has fallen into recession since the beginning of the pandemic in February 2020; its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) plummeted by 4.7 per cent in the first quarter of 2020. Italy’s economy relies on a significant level of informal work and many very small firms; sectors that suffered the most include tourism, construction, agriculture and personal care – all sectors which often employed and employ foreign labour with both regular and irregular employment (Ambrosini Citation2018). What has been described arises the question of how to balance the vulnerability of asylum-seekers and employment opportunities.

Loneliness and pressures from the diaspora community were also determining factors in the decision to leave and seek resettlement elsewhere. One Eritrean refugee explained, ‘Some have perhaps the husband or wife abroad, or the family […] Since in our culture loneliness is not very popular, we want to be together […] also for work reasons.’ He described how a fellow Ethiopian migrant living elsewhere in Europe encouraged him to migrate further.

4.4. Local networks of support

Support works best when it is backed by a network of actors (volunteers, mentor families, schools, parish priests, institutions and social workers) involved at various levels in the process, trying to make a person feel ‘welcomed’, ‘at home’, or part of a community. When this network does not exist or is weak and the host communities are not able to create or consolidate a circle of volunteers, the work remains in the hands of one or few social workers or volunteers who often do not have the expertise and professionalism to handle difficult situations. Sometimes, social workers delegate almost everything to volunteers, limiting themselves to distant supervision. In some locations, we have found that due to particular problems of some families or individuals, specific professional skills (such as an ethno-psychologist) were needed and that local communities were not sufficiently prepared to face certain difficulties. In this sense, it is clear that the model of humanitarian corridors requires an intense and coordinated intervention for the degree of complexity and the strong involvement required.

However, such a relation remains inadequate also when host communities vigorously try to address all the needs of the refugees without favouring their agency and responsibility to integration (Kerry et al. Citation2014). If some of the problems are not solved, the experience of dependency or paternalism may lead to depression or feelings of helplessness. Hence, local mentor families and volunteers are encouraged to avoid approaches where refugees are passive recipients of aid (the ‘dependency syndrome’ described by Harrell-Bond Citation1999). Agency and active participation are key factors in refugees’ integration. Then local hosting communities and volunteers are incited to better understand the content and the extent of the commitment, including its uncertain duration (which depends on external circumstances for many cases: employment, language and schooling), hence their responsibilities.

In our study, we capture indeed relational dynamics that allow an ‘adequate’ level of welcome and social help by leaving spaces of freedom for individuals and families. Human attitudes such as patience, courage and openness are central to the development of trust among refugees, social workers and volunteers. This trust is built through an ongoing dialogue that happens at the same time as when the key actors (practitioners and volunteers) deal with the different aspects of integration and the difficulties that this process entangles (language, culture adaptation and search for job opportunities).

These attitudes will favour the development of humanly positive relationships between refugees and host communities (see, for the UK, Maestri and Monforte Citation2020), permitting to face sudden changes and unannounced departures of beneficiaries and to understand that these departures normally are not the result of an inadequate welcoming, but rather a freely made decision by the refugee to migrate. In fact, it is a gesture of hope.

Here the micro-level and daily dimension of debordering solidarity is at stake: if it is not only an emotion, or a political claim, it tries to translate into effective practices, supporting refugees in their search for autonomy and a better life in Europe. Recalling Askins (Citation2015), daily activities of care become acts of micropolitics. This requires careful attention to develop a set of attitudes and relationships towards beneficiaries, giving support when necessary, but feeding independence, allowing freedom to choose, fostering reciprocity in exchanges.

5. Conclusion: debordering solidarity at work: political meaning and practical limits

HC can lead to the same problems which are often risen against other ‘humanitarian’ endeavours: they have been accused of only slightly softening harsh political closures against asylum-seekers through providing some exceptions; of accepting a neoliberal ideology, which delegates the protection of human rights to private actors on a voluntary basis; of avoiding the task of fighting against a global system of institutional injustice (Ritchie Citation2018).

An evaluation of the experience of HC, however, has a first place to consider the political landscape in which refugees are inserted: a national and international wave of anti-refugee sentiments and mobilisations (Rea et al. Citation2019). When most part of the public opinion seems to demand more closure of borders and less acceptance of asylum claims, the project of HC has offered a possible alternative, responding to several objections to refugee reception: an aid which saves lives of people in danger, cuts profits of traffickers, does not weight on the public budget, does not create huge concentrations of asylum-seekers in urban settings, and involve citizens and communities on a voluntary basis, reinforcing social bonds. Thousands of local citizens have been involved in the reception of about 2,500 refugees (and about 4,000 adding the other EU countries involvedFootnote7), donating money, time, accommodations and professional competence. Dozens of local communities have been in various ways involved. The political meaning of HC, and their connection with the idea of debordering solidarity, consists in this wide grass-root experience of humanitarian reception, rejecting in practice fears of invasion, priority for national citizens’ needs and definitions of solidarity as nationally bounded. Following Fleischmann (Citation2020, 18) ‘practices of refugee support can turn political when they strive to instigate change by enacting alternative modes of togetherness and belonging on the ground’.

As Van Selm (Citation2020) observes for the UK, also for HC in Italy, a strong motive is ‘the expression of support for refugee arrivals’ (194), targeting not only the direct beneficiaries but the public opinion and political actors. It is a form of ‘debordering solidarity’: a project which aims at spreading acceptance of refugees at the local level, counteracting xenophobic discourses, involving residents and triggering more support to asylum-seekers’ settlement. In so doing, HCs affirm in practice an idea of social solidarity which overcomes national borders and belonging to the national community (Agustín and Jørgensen Citation2019; Schwiertz and Schwenken Citation2020; Oomen et al. Citation2021).

HC are beneficial for two reasons. First, a change of narrative, demonstrating that refugees are not a threat to the social order, through developing mutual exchanges and daily relationships between local communities and newcomers. An indirect demonstration of the success of HC on this ground is the fact that any problem or relevant conflict at the local level has been highlighted by mass-media or political actors, for what regards refugees hosted through the HC. Second, the direct engagement of citizens and local communities, through whom refugee reception becomes an opportunity for community building. In general, most refugees and host communities participating in the HC emphasised both positive and reciprocal experiences.

Our study shows, however, that going into the details some issues remain open. First, as the outcomes of labour insertion show, an issue concerning the matching between refugees’ needs and the project of HC arises. It regards the balance between vulnerability and resources for economic and social autonomy. In the project of HC, the capacity to reach independence is crucial: support is provided in principle for one year, although in practice this deadline can be extended. Furthermore, volunteers are not prepared to face cases of heavy traumas and psychiatric disorders. It becomes necessary to recognise that reception through networks of volunteers and local communities is potentially a good solution for many cases of refugees, but not for all of them: in some cases, professional competence and high-skilled public services are required. It appears unrealistic to overburden volunteers with tasks that exceed their skills.

Second, as a consequence, the balance between voluntary engagement and professional competence, in the fields of linguistic and cultural intermediation, psychological support, and in case psychiatric help, implies the necessity of supporting volunteers and local communities, which face problems of communication, cultural misunderstanding and functional overload. Sometimes, the capacity of managing excessive expectations on both sides is required. Third, the existence of the problem of social isolation, deriving from the settlement in villages in which is hard to establish social connections and a wider integration, has to be addressed. Refugees are settled in some localities simply because there are empty buildings available, for free or at a low cost, and because dispersion on the territory appears politically more acceptable. But this is at odds with many refugees’ preference, to settle in urban areas and link with co-ethnic networks. Lastly, the issue of employment: not all the territories, even if welcoming, can offer reasonable opportunities for labour insertion. In Italy, this is especially the case in Southern regions and marginal territories.

In conclusion, we can state that actions speak louder than claims. This means that HC has reinforced political requests in favour of asylum-seekers’ reception, showing in practice, through everyday experience, that hosting refugees does not threaten or endanger national and local communities. HC has designed a practical alternative to border closure and risky journeys by earth and sea, acquiring a political meaning in times of anti-refugee politics. They resonate with what Stavinoha and Ramakrishnan (Citation2020, 183) say about grassroots volunteer groups throughout Europe: they hold ‘the potential for more fluid and humane responses to an ever-changing landscape of refugee flows and containment’. In this case, furthermore, a simplistic contrast between grassroots solidarity and large humanitarian organisations has been overcome, being volunteer groups connected to historical institutions, namely the Catholic and Protestant Churches.

As in every human experience, we found aspects to improve, as we showed in this article. These limits do not weaken, however, the political and cultural meaning of such spontaneous engagement by thousands of citizens and dozens of local communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 Regulation (EC) No. 810/2009 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 establishing a Community Code on Visas (Visa Code).

3 In this case admissions are counted under the government’s resettlement program.

4 https://www.mediterraneanhope.com/2021/08/31/refugees-new-protocol-for-a-thousand-more-arrivals-with-humanitarian-corridors-from-lebanon/. Downloaded on 15 November 2021.

5 https://www.avvenire.it/attualita/pagine/corridoi-umanitari-niger-profughi, 6 February 2021. Downloaded on 9 November 2021.

6 To simplify we called the beneficiaries of the humanitarian corridors “refugees” even before they granted the refugee status in Italy.

7 https://www.mediterraneanhope.com/2021/11/05/profughi-corridoi-umanitari-arrivati-questa-mattina-dal-libano-44-siriani/. Downloaded on 15 November 2021.

References

- Ager, A., and A. Strang. 2008. “Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Refugee Studies 21 (2): 166–191.

- Agier, M. 2011. Managing the Undesirables: Refugee Camps and Humanitarian Government. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Agustín, O. G., and M. B. Jørgensen. 2019. Solidarity and the ‘Refugee Crisis’ in Europe. Cham: Springer.

- Ahmad Ali, M., S. Zendo, and S. Somers. 2021. “Structures and Strategies for Social Integration: Privately Sponsored and Government Assisted Refugees.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. doi:10.1080/15562948.2021.1938332.

- Albanese, D., and M. Tardis. 2020. “Safe and Legal Pathways for Refugees: Can Europe Take Global Leadership?” In The Future of Migration in Europe, edited by M. Villa, 98–100. Milan: Ledizioni ISPI.

- Ambrosini, M. 2018. Irregular Immigration in Southern Europe. Actors, Dynamics and Governance. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Ambrosini, M. 2021. “The Battleground of Asylum and Immigration Policies: A Conceptual Inquiry.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 44 (3): 374–395.

- Artero, M. 2019. “Motivations and Effects of Volunteering for Refugees. Spaces of Encounter and Political Influence of the ‘New Civic Engagement’ in Milan.” Partecipazione e Conflitto 12 (1): 142–167.

- Artero, M., and E. Fontanari. 2021. “Obstructing Lives: Local Borders and Their Structural Violence in the Asylum Field of Post-2015 Europe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (3): 631–648.

- Askins, K. 2015. “Being Together: Everyday Geographies and the Quiet Politics of Belonging.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 14 (2): 461–469.

- Ataç, I., T. Schütze, and V. Reitter. 2020. “Local Responses in Restrictive National Policy Contexts: Welfare Provisions for Non-Removed Rejected Asylum Seekers in Amsterdam, Stockholm and Vienna.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43 (16): 115–134.

- Campomori, F., and M. Ambrosini. 2020. “Multilevel Governance in Trouble: The Implementation of Asylum Seekers Reception in Italy as a Battleground.” Comparative Migration Studies 8 (22): 1–19.

- Caritas italiana (ed.). 2019. Oltre il mare. Primo rapporto sui corridoi umanitari in Italia e altre vie legali e sicure d’ingresso. www.caritas.it/caritasitaliana/allegati/8149/Oltreil_Mare.pdf.

- Carrera, S., S. Blockmans, D. Gros, and E. Guild. 2015. The EU’s Response to the Refugee Crisis. Taking Stock and Setting Policy Priorities. CEPS Essay, No. 20 / 16 December 2015. Downloaded from: EU Response to the 2015 Refugee Crisis_0.pdf (ceps.eu).

- Castelli Gattinara, P. 2017. “Mobilizing Against ‘the Invasion’: Far Right Protest and the ‘Refugee Crisis’ in Italy.” Mondi Migranti 11 (2): 75–95.

- Dimitriadis, I., M. H. Hajer, E. Fontanari, and M. Ambrosini. 2021. “Local ‘Battlegrounds’. Relocating Multi-Level and Multiactor Governance of Immigration.” Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 37 (1–2): 251–275.

- Dines, N., N. Montagna, and V. Ruggero. 2015. “Thinking Lampedusa: Border Construction, the Spectacle of Bare Life and the Productivity of Migrants.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 38 (3): 430–445.

- Faist, T. 2018. “The Moral Polity of Forced Migration.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 41 (3): 412–423.

- Faist, T. 2019. The Transnationalized Social Question. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fassin, D. 2005. “Compassion and Repression: The Moral Economy of Immigration Policies in France.” Cultural Anthropology 20 (3): 362–387.

- Fassin, D. 2011. “Policing Borders, Producing Boundaries. The Governmentality of Immigration in Dark Times.” Annual Review of Anthropology 40: 213–226.

- Fassin, D. 2012. Humanitarian Reason: A Moral History of the Present. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fleischmann, L. 2017. “The Politics of Helping Refugees. Emerging Meanings of Political Action Around the German ‘Summer of Welcome.’” Mondi migranti 11 (3): 53–73.

- Fleischmann, L. 2020. Contested Solidarity. Practices of Refugee Support between Humanitarian Help and Political Activism. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag.

- Garofalo, S. 2017. “La frontiera mediterranea possibile. L’esperienza dei corridoi umanitari.” Occhialì. Rivista sul Mediterraneo Islamico 1 (1): 100–110.

- Genovese, F., M. Belgioioso, and F. Kern. 2017. The Political Geography of Migrant Reception and Public Opinion on Immigration: Evidence from Italy. Mimeo. Unpublished manuscript.

- Giliberti, L., and L. Queirolo Palmas. 2021. “The Hole, the Corridor and the Landings: Reframing Lampedusa Through the COVID-19 Emergency.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. doi:10.1080/01419870.2021.1953558.

- Glick Schiller, N., and N. B. Salazar. 2013. “Regimes of Mobility Across the Globe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (2): 183–200.

- Gois, P., and G. Falchi. 2017. “The Third way. Humanitarian Corridors in Peacetime as a (Local) Civil Society Response to a EU’s Common Failure.” REMHU, Revista Interdisciplinar da Mobilidade Humana 25 (51): 59–75.

- Hagan, J. M. 2008. Migration Miracle. Faith, Hope and Meaning on the Undocumented Journey. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Harrell-Bond, B. 1999. “The Experience of Refugees as Aid Recipients.” In Refugees: Perspectives on the Experience of Forced Migration, edited by A. Ager, 136–168. London: Continuum.

- Kerry, V., A. Binagwaho, J. Weigel, and P. Farmer. 2014. “From Aid to Accompaniment: Rules of the Road for Development Assistance.” In The Handbook of Global Health Policy, edited by G. W. Brown, G. Yamey, and S. Wamala, 483–504. Oxford: Wiley.

- Kirsch, T. G. 2016. “Undoing Apartheid Legacies? Volunteering as Repentance and Politics by Other Means.” In Volunteer Economies. The Politics and Ethics of Voluntary Labour in Africa, edited by H. Brown, and R. Prince, 201–221. Oxford: J. Currey.

- Kumin, J. 2015. Welcoming Engagement: How Private Sponsorship Can Strengthen Refugee Resettlement in the European Union. Brussels: Migration Policy Institute Europe. http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/welcomingengagement-how-private-sponsorship-can-strengthen-refugee-resettlement-european.

- Lavenex, S. 2006. “Shifting Up and Out: The Foreign Policy of European Immigration Control.” West European Politics 29 (2): 329–350.

- Macklin, A., L. Goldring, J. Hyndman, A. Korteweg, K. Barber, and J. Zyfi. 2020. The kinship between refugee and family sponsorship. Working Paper Series 2020/4. RCIS & CERC, Ryerson University.

- Maestri, G., and P. Monforte. 2020. “Who Deserves Compassion? The Moral and Emotional Dilemmas of Volunteering in the ‘Refugee Crisis.’” Sociology 54 (5): 920–935.

- Malkki, L. 1996. “Speechless Emissaries: Refugees, Humanitarianism, and Dehistoricization.” Cultural Anthropology 11 (3): 377–404.

- Marchetti, C. 2020. “(Un)Deserving Refugees. Contested Access to the ‘Community of Value’ in Italy.” In Europe and the Refugee Response. A Crisis of Values?, edited by E. M. Gozdziak, I. Main, and B. Suter, 236–252. London: Routledge.

- Oomen, B., M. Baumgärtel, S. Miellet, T. Sabchev, and E. Durmuş. 2021. “Of Bastions and Bulwarks: A Multiscalar Understanding of Local Bordering Practices in Europe.” International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 10 (3): 16–29.

- Pohlmann, V., and H. Schwiertz. 2020. Private Sponsorship in Refugee Admission: Standard in Canada, Trend in Germany? Research Brief No. 2020/1, RCIS & CERC. Ryerson University.

- Rea, A., M. Martiniello, A. Mazzola, and B. Meuleman. 2019. The Refugee Reception Crisis in Europe. Polarized Opinions and Mobilizations. Bruxelles: EUB.

- Ricci, C. 2020. “The Necessity for Alternative Legal Pathways: The Best Practice of Humanitarian Corridors Opened by Private Sponsors in Italy.” German Law Journal 21: 265–283.

- Ritchie, G. 2018. “Civil Society, the State, and Private Sponsorship: The Political Economy of Refugee Resettlement.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 37 (1): 1–13.

- Rozakou, C. 2017. Solidarity #Humanitarianism: the Blurred Boundaries of Humanitarianism in Greece. https://allegralaboratory.net/solidarity-humanitarianism/, 2017 September 27.

- Sandri, E. 2018. “‘Volunteer Humanitarianism’: Volunteers and Humanitarian aid in the Jungle Refugee Camp of Calais.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (1): 65–80.

- Schwiertz, H., and H. Schwenken. 2020. “Introduction: Inclusive Solidarity and Citizenship Along Migratory Routes in Europe and the Americas.” Citizenship Studies 24 (4): 405–423.

- Snyder, S. 2012. Asylum-Seeking, Migration And Church. Burlington: Ashgate.

- Sözer, H. 2020. “Humanitarianism with a Neo-Liberal Face: Vulnerability Intervention as Vulnerability Redistribution.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (11): 2163–2180.

- Sponsor Refugees. 2019. Welcome. Available at: www.sponsorrefugees.org.

- Stavinoha, L., and K. Ramakrishnan. 2020. “Beyond Humanitarian Logics: Volunteer-Refugee Encounters in Chios and Paris.” Humanity Journal 11 (2): 165–186.

- Suter, B. 2021. “Social Networks and Mobility in Time and Space: Integration Processes of Burmese Karen Resettled Refugees in Sweden.” Journal of Refugee Studies 34 (1): 700–717. doi:10.1093/jrs/fez008.

- Ticktin, M. 2011. Casualties of Care. Immigration and Politics of Humanitarianism in France. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ticktin, M. 2014. “Transnational Humanitarianism.” Annual Review of Anthropology 43: 273–289.

- Trotta, S. 2017. “Faith-Based Humanitarian Corridors to Italy: A Safe and Legal Route to Refuge.” Refugee Hosts, 2 May.

- UNHCR. 2016. “Vulnerability Screening Tool – Identifying and Addressing Vulnerability: A Tool for Asylum and Migration Systems.” https://www.refworld.org/docid/57f21f6b4.html.

- UNHCR. 2020. Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2019. Geneva: UNHCR.

- UNHCR. 2021. Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2020. Geneva: UNHCR.

- Vandevoordt, R., and G. Verschraegen. 2019. “Subversive Humanitarianism and Its Challenges: Notes on the Political Ambiguities of Civil Refugee Support.” In Refugee Protection and Civil Society in Europe, edited by M. Feischmidt, L. Pries, and C. Cantat, 101–128. Cham: Springer.

- van Dijk, H., L. Knappert, Q. Muis, and S. Alkhaled. 2021. “Roomies for Life? An Assessment of How Staying with a Local Facilitates Refugee Integration.” Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. doi:10.1080/15562948.2021.1923879.

- Van Selm, J. 2020. “Community-based Sponsorship of Refugees Resettling in the UK: British Values in Action?” In Europe and the Refugee Response. A Crisis of Values? edited by E. M. Gozdziak, I. Main, and B. Suter, 185–200. London: Routledge.

- Zetter, R. 2007. “More Labels, Fewer Refugees: Remaking the Refugee Label in an Era of Globalization.” Journal of Refugee Studies 20 (2): 172–192.