ABSTRACT

This article examines the emergence of a ‘migration industry’ as a result of European border externalisation and security outsourcing practices to curb migration flows from Libya. It argues that the management of migration has been partly delegated to a network of interlinked private and public actors which constitute a complex migration governance structure that ultimately gives rise to issues of transparency and accountability. Informed by theoretical approaches drawn from both Security and Migration Studies, the article offers an empirical analysis of the organisation and logics of the migration industry in a specific context, mapping and analysing the setup of actors, structures and processes that contribute to the security of the Euro-Libyan border. By doing so, it offers important insights into contemporary migration governance in the European context.

Introduction

Over the past years, migration management, originally a ‘set of rules and practices historically developed by a country’ (Sciortino Citation2004, 32), has shifted beyond the state by both relocating the border outside the state’s territory (externalisation) and delegating border control functions to non-state and third-state actors (outsourcing). Even if this is not a new phenomenon (see Harney Citation1977), it is unprecedented in terms of diffusion and level of institutionalisation. Indeed, outsourcing and externalising border security has become systematic as states use state funds, sign business contracts and enter into official (and semi-official) agreements with third-party actors. In the European context, externalisation is visible both in practices aimed at outsourcing care (for instance through the funding of NGOs or economic incentives) and control (financing border guards, reinforcing detention centres). The goal is to protect European borders from illegal entries and, ostensibly, to address the root causes of migration in countries or origin, transit and departure. Against this backdrop, researchers have introduced the idea of a ‘migration industry’ (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg-Sørensen Citation2013) to denote the network of organisations, businesses and individuals that in various ways facilitate or restrict the movement of people across state borders.

As actors involved in this ‘industry’ are proliferating in Europe and beyond, scholars across several fields have started to focus on this complex web of relations to make sense of developments in global migration governance (Betts Citation2011). In fact, many argue that state-centric analyses are no longer sufficient as they risk downplaying the complexity of a field characterised by a growing state and non-state, as well as public and commercial, interconnectedness. Following such arguments, this article centres on the migration industry growing out of European externalisation and outsourcing policies and practices. Focusing on the case of Libya, our aim is to uncover the workings and relational configurations of the migration industry – the network of supranational organisations, European governments, third-state governments, private companies, militias – that help shape multifaceted migration governance structures. By mapping and analysing this complex network of state and non-state actors, the article contributes to our understanding of key transformations in migration governance structures and processes, as well as the wider implications of this development for issues of accountability and transparency. In particular, our article speaks to recent research in the field that seeks to offer a systematic image of the phenomenon by analysing the functions outsourced, the actors involved as well as the multiple issues arising from this trend (Lopez-Sala and Godenau Citation2020).

To focus our efforts, we examine the outsourcing of migration control in Libya as part of the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for stability and addressing the root causes of irregular migration and displaced persons in Africa (EUTF). Trust Funds are multi-donor financing mechanisms created and administered by the European Commission to implement quick international cooperation and development responses to major emergencies (EC Citation2013). Launched at the 2015 Valletta Summit to address the so-called migration crisis, the EUTF de facto represents one of the key tools with which the EU is externalising its borders and enabling the creation of a European migration industry. So far, most authors have concentrated on the EUTF as a general instrument (Zanker Citation2019; Zaun and Nantermoz Citation2021) and have hitherto not engaged deeply with specific projects or with the workings of the migration industry in the EUTF context. Several analyses have focused on the ‘high politics’ of externalisation or the relation between European states and other countries (Lavenex Citation2008; Reslow Citation2012; Trauner and Wolff Citation2014). Still, we have insufficient knowledge about the implementation of specific projects beyond the EU, as well as the design and function of control and monitoring mechanisms (but see Zardo Citation2020). As several reports indicate, one reason for this relative lack of knowledge is the opaque nature of the Trust Fund and associated projects (Oxfam Citation2017; Concord and Cini Citation2018; ECA Citation2018). At the same time, a wealth of academic literature has raised concern about the use of complex blended financial instruments in terms of accountability and transparency (Castillejo Citation2017; Herrero Cangas and Knoll Citation2016; Carrera et al. Citation2018; Kipp Citation2018). In particular, some authors point to the flexible nature of the EUTF, warning that such a structure could easily result in non-transparent procedures (Castillejo Citation2017; Carrera et al. Citation2018), opaque procurement processes (Kipp Citation2018, 23), and loss of oversight and ownership of how the funds are spent (Herrero Cangas and Knoll Citation2016). In this sense, our mapping of the implementation of the EUTF in a specific context empirically supports such findings, pointing to similar issues in the practical outcomes of this complex financial instrument in relation to the Libyan migration industry.

As a great number of external private and public actors continue to be entrusted with key tasks in migration management, knowing who these actors are, how they are linked to one another as well as their role in securing the border is key to our understanding of the implications of contemporary migration governance policies and practices. Empirically, we contribute to this endeavour by focusing on the EUTF-funded and Italian-implemented project Support to Integrated Border and Migration Management in Libya (IBM) to uncover how the intertwining of governments, security forces, private security actors and militias shape processes and structures of border security at the EU-Libyan border. Mapping security actors and the outsourcing of key functions through an in-depth analysis of both official documents and secondary sources, this paper provides much-needed insights into relational configurations and challenges of monitoring, accountability and democratic oversight. The analysis draws on, and adds to, both Migration and Private Security Studies by investigating issues of security outsourcing and marketisation in migration.

The first part of the paper will help situate our argument in relation to the broader fields of Migration and Private Security Studies, drawing conceptually from both fields. The methodological section that follows details our experience from trying to access relevant documents and constitutes an important outcome. The difficulty we experienced in accessing relevant documents and the seeming impossibility to scrutinise European activities financed with public money underscore the general lack of transparency and accountability of the Trust Fund and related projects. In the central part of the paper, we focus our analysis on the numerous border security agreements between the EU, Italy and Libya over the last two decades. Finally, we present the core of our contribution with the analysis of an important border management project and the setup of actors, structures and processes that contribute to the security of the Euro-Libyan border. In particular, we study the complex network of public and private actors that effectively constitute a fully-fledged ‘migration industry’, with tasks and responsibilities often overlapping. Finally, we discuss potential issues of transparency, accountability and human rights violations that could be amplified by the complexity of migration governance structures in the Libyan context.

New border security actors and the migration industry

In Private Security Studies (Abrahamsen and Leander Citation2015), researchers have long pointed to the increasing use of non-state actors in security work, a process often referred to in general terms as the ‘privatisation of security’ (Berndtsson and Kinsey Citation2016; Abrahamsen and Leander Citation2015). Importantly, the rise of the private security industry is not only a consequence of state transfer of responsibility and authority, even if such processes are common. To a considerable degree, the private security industry has also flourished as a consequence of states’ unwillingness or weakness, and private actors have readily stepped into security voids created in spaces where state agencies or actors are largely or wholly absent. Consequently, many authors have called for alternative approaches in order to avoid narrow and essentially misleading conceptualisations of security, protection and the use of force as necessarily related to the state and state institutions such as the police and the military (Abrahamsen and Williams Citation2011). While this trend transcends ‘privatisation’ in the narrow sense, the concept might be used as a general description of a process whereby commercial and other non-state actors become increasingly involved in policing and protection-related activities. In this context, migration management and border control are no exceptions (Gammeltoft-Hansen Citation2016).

The use of security and defence companies in migration management and border control has been identified as a fairly recent development. Increasingly, private companies are called upon to manage detention facilities, migration flows, border checkpoints and provide equipment and/or training for other state or non-state actors involved in migration work (e.g. Baird Citation2018; Davitti Citation2019; Lopez-Sala and Godenau Citation2020; Cohen Citation2020). Analysing cases such as Libya, this commercialisation of migration and border management needs to be seen as a development of the security privatisation trend. Generally speaking, we can divide the externalisation and outsourcing of border security into two broad fields: one that delegates migration management functions to third countries (Gammeltoft-Hansen Citation2006) and one that delegates to private actors (Menz Citation2010; Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg-Sørensen Citation2013). Although sometimes treated separately, these two modes of outsourcing are not mutually exclusive but often combined to achieve efficiency in managing migrants. As migration shifted from being purely a domestic matter to a central feature of EU Foreign Policy (Gammeltoft-Hansen Citation2006), outsourcing to third countries has been increasingly institutionalised through various processes, such as through the European Neighbourhood Policy, the Global Approach to Migration, the Global Approach to Migration and Mobility, the Rabat Process, the Khartoum Process and the Valletta Summit. Against this backdrop, we focus on the EUTF, the key financial foreign policy instrument to outsource migration control to both third countries and private actors. As such, our analysis resonates with long-standing debates between scholars of EU Foreign Policy (Wong Citation2007; Keukeleire and MacNaughtan Citation2008; Sanchez-Barrueco Citation2018). In particular, as we shall see, the role of Italy in shaping the European agenda in Libya speaks to bottom-up Europeanisation processes in which EU member states are able to project national priorities at the EU level (Wong Citation2007, 325). Besides, scholars have already shown how development cooperation is often used to pursue changes that align with particular EU foreign policy objectives (Keukeleire and MacNaughtan Citation2008). On the other hand, the privatisation of border security has also been a crucial aspect of the European migration management strategy, with technology companies at the forefront of EU surveillance projects (e.g. EUROSUR) and some of the biggest private security and defence companies (e.g. G4S, Leonardo, BAE Systems, Airbus) are involved in providing a wide range of services and products (Lemberg-Pedersen Citation2018; Akkerman Citation2016; Davitti Citation2019). As shown by some authors, the steering of development funds to EU security companies is a recurring feature of EU foreign policy (Sanchez-Barrueco Citation2013).

Indeed, both recipient states and private actors are fundamental to make sense of a migration governance that is becoming essentially ‘polycentric’ (Scholte Citation2004) with different actors involved directly and indirectly in all stages of the migration management process (i.e. tracing intercepting, deterring, incarcerating, alleviating sufferance). As previously shown (Andersson Citation2014; Schapendonk Citation2018), migration management is not always homogenous and coherent, but includes networks of different actors, sometimes with diverging interests, goals and responsibilities, whose roles may shift over time. Following this approach, we posit that a variety of different state and non-state actors with a wide range of different, and sometimes contradictory agendas and interests cooperate and create networks through the EUTF.

To conceptualise the conglomerate of different actors involved in migration management, scholars have talked about an ‘industry’ (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg-Sørensen Citation2013), a ‘market’ (Nyberg-Sørensen Citation2012) a ‘business’ (Salt and Stein Citation1997; Andersson Citation2014), an ‘infrastructure’ (Xiang and Lindquist Citation2014) or more generally about the ‘privatisation of migration’ (Menz Citation2010). Furthermore, scholars have focused on the different sets of actors to whom migration management functions are outsourced. These can be actors that both facilitate or restrict movement, as well as actors involved in what we can loosely call the ‘business of care’ (i.e. NGOs). Against this backdrop, we can distinguish authors that investigate the privatisation of immigrant detention (Ackerman and Furman Citation2013; Arbogast Citation2016), the provision of services and equipment by private companies (Lemberg-Pedersen Citation2018; Davitti Citation2019), the involvement of NGOs (Cuttitta Citation2018), IOs (Andrijasevic and Walters Citation2010), civil actors such as carrier and transport services (Walters Citation2015), labour brokers (Anderson Citation2019) and smugglers (Salt and Stein Citation1997).

In light of the above, our contribution focuses on those ‘control providers’ who, unlike other actors, tend to work closely with governments (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg-Sørensen Citation2013, 6; also Lopez-Sala and Godenau Citation2020). Thus, we adopt and expand the term ‘migration industry’ to define the network of non-state and third-state actors who ‘provide services that facilitate, constrain or assist international migration’ (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg-Sørensen Citation2013, 6–7). In this context, it is important to underline that the term ‘non-state’ denotes a variety of commercial, non-commercial, legal and illegal actors, ranging from security companies, NGOs, lawyers and agents to traffickers and smugglers. Furthermore, and following Menz, we recognise that privatisation and outsourcing ‘do not necessarily imply that migration control is carried out by private actors in lieu of actions otherwise taken by public authorities. Instead, the state involves private actors in migration enforcement in addition to maintaining – and often extending – a state migration management apparatus’ (Menz Citation2013, 110). This process also creates new ‘hybrid’ security networks and modes of governance that disperses authority and control (Abrahamsen and Williams Citation2011; Berndtsson and Stern Citation2011; Hönke Citation2013).

In this paper, we observe how border security is entrusted to both state and non-state, global and local actors. A key argument is that we need to look at all these actors together in order to avoid creating a fragmented picture of migration management and governance. Additionally, an analysis that looks at the interplay between actors is crucial to uncover the opaque nature of these practices (Schapendonk Citation2018). Several scholars have analysed the controversial dynamics that might result from the delegation of border security functions to private and third-state actors (Leander Citation2005; Lemberg-Pedersen Citation2018; Menz Citation2011; Gammeltoft-Hansen Citation2013). One important consequence of the involvement of private and public actors at different levels of the migration management process is the difficulty of demarcating divisions of responsibility between state (whether the EU or Libya) and non-state actors (whether private companies or militias). In addition, this development may generate semi-autonomous and unpredicted structures and dynamics that might make it difficult to assign responsibility or to prevent and investigate problems such as violations of international and human rights law. Additionally, migration controls at the external borders have created a strong demand for security services provided by private companies that frame migration primarily as a security problem. Leander (Citation2005) describes this dynamic in relations to private security and military companies, where commercial actors that effectively become experts that help shape understandings about security threats and their solutions. In addition, there are a number of concerns regarding the effects of outsourcing on democratic control, transparency and accountability (Gammeltoft-Hansen Citation2013), and on the protection of migrants’ human rights (Sanchez-Barrueco Citation2018; Panebianco Citation2020).

Methodological note

The analysis focuses on the EUTF project ‘Support to Integrated Border Management in Libya-First Phase’ (IBM), managed by the Italian Ministry of Interior (MoI) in close cooperation with Libyan authorities. Given the novelty of the subject, an exploratory research design with a single in-depth case study methodology is best suited to achieve our aim. The choice to study this specific case comes from a preliminary mapping of the most relevant EUTF projects in North of Africa. Among the countries targeted by border security projects, Libya is by far the one which has received most funds. Indeed, Libya is characterised by on-going instability and conflict, and is a common departure point for migrants trying to reach Europe. Out of the 13 active EUTF projects in the country, IBM is the only one with a clear and open border security mandate, thus we believe it to be most suited to analyse the border security outsource and the migration industry that this process generates.

Methodologically, this research relies on a qualitative analysis of official, unpublished policy documents at the EU and Italian level, bidding procedures as well as secondary sources such as accredited independent journalism sources and CSOs websites and reports (e.g. Altraeconomia, Association for Juridical Studies on Immigration-ASGI, Italian Cultural and Recreational Association, ARCI). Documents and contracts were collected from both publicly available sources, such as the webpage of the EUTF and the Italian Polizia di Stato (State Police), and by filing several Freedom of Information (FOI) requests to the Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (DG NEAR) and to the Italian Ministry of Interior (MoI). Public documents available online will be referenced in notes. Through in-depth content analysis we have mapped out the networks of state and non-state actors involved and the main border security tasks outsourced. Besides, document analysis also points to evidence of a lack of transparency and accountability.

The overall data collection process has been far from smooth, and in many instances, we were denied access to relevant documents or information.Footnote1 However, instead of dismissing the innumerable negative replies as a worthless research outcome, we believe them to be revealing and informative, especially for what concerns the lack of transparency. It took us several months and several revisions of the FOI requests to accommodate DG NEAR requirements. After 4 months, we finally received a rather unsatisfactory reply, as DG NEAR granted access to very few documents. Similarly, the MoI disclosed only one document (with some parts redacted), claiming that all the others concern international relations and police cooperation with third countries and therefore are not subjected to transparency requirements. Nevertheless, thanks to some alternative sources, we were able to bypass the official procedure and gather some of the documents denied. Indeed, the bureaucratic process involved in filing the requests, the rather long timeframe required to receive a reply, and the legislative measures that grant the Commission and the MoI the right to narrow the scope of the requests and decide which information to disclose, make the overall process cumbersome. This lack of transparency is certainly not new in security and migration research, as scholars of both fields have encountered similar difficulties (Berndtsson Citation2017; Baird Citation2018; Kalir, Achermann, and Rosset Citation2019). In the sections that follow, we will show the practical functioning of the migration industry in the case of Libya.

Externalising migration management: old strategies, new opportunities

In order to expand our knowledge about the functioning of the migration industry that emerges as a result of EU border security policies and practices, we conduct a detailed mapping of the actors, processes and structures involved. However, before moving to a detailed analysis of IBM project, we should contextualise this project within two decades of agreements between the EU, Italy and Libya to curb migration flows.

For some years, both Italy and the EU have been pursuing a strategy of containment by various means, including the provision of training, equipment and various forms of assistance to Libyan authorities with the involvement of private security actors. At the European level, cooperation on migration management started in the late 1990s as Libya began to be recognised as a key point of entry into Europe. After an initial stalemate following the NATO intervention in March 2011, cooperation resumed with the National Transitional Council (NTC). Indeed, the 2011 conflict led to a massive displacement crisis. As a consequence, the conditions of immigrants and refugees significantly worsened, and human smuggling became an even more profitable and institutionalised activity. Soon after, the EU launched several missions such as the EU Border Assistance Mission (EUBAM) in 2013, Operation Sophia in 2015 and its substitute Operation Irini in 2020. These missions envisioned the training and capacity building of the Libyan Coast Guard and Navy as a priority and included private security contracts to provide border protection (i.e. to Vesper Group, Groupe Geos, Leonardo S.p.a.). In 2017, EU leaders endorsed the Italy-Libya Memorandum of Understanding which stated the intention to ‘prevent departure and managing returns’ also through EUTF resources. Indeed, the 2017 MoU renewed in February 2020 provides the political basis of any migration management agreement between Europe and Libya. Against this backdrop, the role of Italy has been crucial in shaping the European migration strategy in Libya and in paving the way for a solid cooperation by successfully projecting national priorities towards the EU. Starting from the 2000s, Italy and Libya signed several border security agreements which comprised, among others, financial assistance for the construction of detention centres, training courses for Libyan police forces, readmission agreements, deportation schemes and the supply of various forms of equipment (vessels, rubber boats, road vehicles, binoculars etc.). Therefore, far from being an exception, the EUTF project analysed here is part of a two decades-long strategy decided both at the European and Italian level. Moreover, the overlaps of multiple strategic and commercial interests as well as the involvement of a plethora of different private and public actors, is also a central and long-standing feature of the Euro-Libyan migration governance.

The first phase of IBM started in 2017 and officially ended in December 2020 with the start of a second phase currently ongoing. From the beginning, IBM had the twofold objective of improving the capacity of the Libyan authorities in the control of land and sea borders, while also fostering the establishment of a Libyan Maritime Coordination Centre and a SAR region. The estimated total cost of the project is of EUR 46,300,000, of which EUR 42, 223, 927 drawn directly from the EUTF and EUR 2,231,256 co-financed by Italy. Moreover, the project received a parallel financing contribution under the EU Internal Security Fund of EUR 1,844,816. The total estimated cost allocated for the first phase is divided between 4 different activities (Action Fiche Citation2017): activity 1, which is by far the most important one, comprises technical training, operational training and the delivery of vessels, other means of transport, communication tools and various equipment; activity 2 foresees the establishment of an Interagency National Coordination Centre (NCC) and a Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) to facilitate surveillance and control activities; activity 3 and 4 foresee, respectively, the implementation of a Libyan Search and Rescue region (SAR) and the surveillance of Southern borders by the Land Border Guards (LBG).

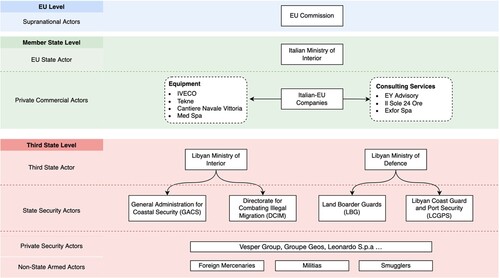

The Italian Ministry of Interior is the main implementing actor and the project is a continuation of activities that Italy has long been implementing in the country on a bilateral basis under official or semi-official agreements. In particular, the training and equipment of the Libyan border guards, an EU priority long before the EUTF (Loschi, Raineri, and Strazzari Citation2018), constitutes the core of the project. As a result, a number of different private companies have been contracted to provide equipment, training or consulting services to the Libyan counterpart. The Libyan authorities officially involved are the Ministry of Interior (the General Administration for Coast Security-GACS and General Directorate for Combating Illegal Immigration-DCIM) and the Ministry of Defence (Land Border Guards, LBG, and the Libyan Coast Guard and Port Security, LCGPS). However, given the fragmented nature of power in Libya and the well-documented links between the GNA and non-state actors (Pack Citation2019), border security functions are equally carried out by militias, smugglers and armed groups that gravitate around official state structures. Thus, the security of the Euro-Libyan border is performed by a complex network comprising private and public, global and local actors whose goals and priorities are sometimes aligned, sometimes diverging. The sections that follow provide a picture of the main actors involved in the management of the Euro-Libyan border through IBM at different levels. By mapping how the EU partly delegates border control functions to EU private commercial actors and third state security actors (GACS, DCIM, LBG, LCGPS), who in turn are linked to private security actors (including foreign mercenaries) and non-state armed actors (militias, smugglers, armed groups), we show the complexity of outsourcing practices and the price of these solutions in terms of accountability and transparency ().

Commercialising and privatising the border

Starting in 2018, the Italian Ministry of Interior (MoI) used EUTF resources to launch large calls for tenders for the provision of training services, equipment and various forms of assistance to the Libyan border guards. To date, the funds that can be tracked through the calls for tenders only account for a small part of the total allocated budget. This both downplays the real scale of border security contracts and casts doubt on the overall transparency of the migration industry created through European and Italian money. Since the Italian MoI decides with full discretion which contracts are to be made public, most of them remain inaccessible, de facto preventing public scrutiny of the projects. Nevertheless, our mapping of the companies involved and the kind of equipment and services provided reveal a partial, yet complex picture of the commercialisation and privatisation of migration and border management in the Libyan context.

Most of the contracts concern the provision of vehicles and vessels to the Libyan authorities. In 2019 the company IVECO Defence Vehicle provided minibusesFootnote2 for a total of EUR 722,500.00 and the company TEKNE provided 30 TOYOTA vehiclesFootnote3 for EUR 1,750,000. Both companies are well-known in the Italian and international defence market, as they have benefited from large contracts with the Italian Ministry of Defence and have links with two of the largest European arm producer companies. IVECO Defence Vehicle has been partnering with BAE SystemsFootnote4 for the production of military vehicles for the US army, whereas TEKNE signed a framework agreement integrating former Thales personnel working in Italy.Footnote5 Furthermore, in 2020, the company Med Spa won a bid for the provision of 6 automatic vessels worth EUR 1,660,800.Footnote6 With its division Med Defence dedicated to government and military, the company is a partner of the Italian Military.Footnote7 Arguably, such materiel constitutes important non-human actors that ‘without usurping human agency, extend it and shape it in important ways’ (Frowd Citation2018, 102). In fact, both vessels and vehicles perform important functions of border control: while vessels directly halt migrants intending to depart from Libya, the vehicles perform a sort of pre-emptive control, by blocking migrants on the land before they even embark on that journey. Thus, by providing material equipment to the Libyan counterpart, these private companies become important stakeholders in the migration industry.

Other commissions concern the provision of training services to both the Italian and Libyan border police, which indeed contribute to shaping securitised knowledges and practices on how to deal with migration flows. In 2018, the Italian Ministry of Interior awarded the provision of ‘specialised consultancy services and technical assistance in favour of the Central Direction for Immigration and Border Police’Footnote8 to the company EY Advisory for EUR 100,660.00, whereas a second call for proposals concerning an ‘online legal consultancy service’Footnote9 was awarded to the company Il Sole 24Ore for EUR 38,500.00. In 2019 the Ministry of Interior awarded a major call for bids of EUR 943,000.00 for a training course for the Libyan Coast Guard to the company Exfor Spa. According to the documents released by the MoI, the training had the stated goal of ‘enhancing the capacity building of the Libyan Coast Guard to increase the Libyan capacity to combat illegal migration’.Footnote10 In practice, the training consisted of 140 h of theory and practice on ‘navigation systems, electric and electronic systems, propulsion systems, routine maintenance, safety on board and international regulations’.Footnote11 However, according to the company’s webpage, for the period 2014–2020, Exfor has only delivered courses to ‘make pizzas, prepare alcoholic beverages and pre-cooked dishes’,Footnote12 all activities that are unlikely to be compatible with the courses delivered to the Libyan Coast Guard. Indeed, the fact that a rather-small regional company whose core business is offering cookery courses was able to win such a major public procurement raises legitimate doubts about the overall tendering process.

During Exfor’s training in Tunis, two vessels were found to be in poor conditions, thus the MoI awarded a contract to Cantiere Navale Vittoria to repair them.Footnote13 This company is a major beneficiary of the outsourcing of border security to Libya and has been receiving substantial funding for several millions of Euros from both Italy and the EU.Footnote14 Besides, Cantiere Navale Vittoria was directly chosen by the Libyan authorities and consequently contracted by the Italian government not to ‘jeopardize the relation with the Libyans and the overall cooperation in contrasting illegal migration’.Footnote15 Indeed, these links between Cantiere Navale Vittoria, Italian and Libyan authorities point towards opaque public procurement processes. In May 2017, a few months after the signature of the Italian-Libyan MoU, during an official meeting between representatives of Cantiere Navale Vittoria, Italian and Libyan authorities in Tunisia, the parties negotiated the provision of equipment, maintenance work, training courses and insurance policies. Moreover, on 2nd February 2020, the same day of the renewal of the MoU between Libya and Italy, Cantiere Navale Vittoria delivered two repaired vessels during an institutional meeting between the Libyan Coast Guard authorities and a representant of the Italian security services.Footnote16 This meeting was made public through a Facebook post on the official page of the LGCS.Footnote17

The substantial resources invested in IBM, the involvement of commercial actors and the connection between the companies involved and the Libyan and Italian authorities raise concerns about the transparency of these policies, as well as about who is actually responsible for the outcomes on the ground. Indeed, by outsourcing migration management to private companies, the EU is de facto circumventing transparency and accountability requirements as private actors cannot be held accountable and are not required to publicly disclose their business strategies. As already pointed out by other scholars, the delegation of border control functions makes it hard to bring state actions under public scrutiny (Lopez-Sala and Godenau Citation2020). Indeed, complexity and opaqueness are in the very nature of the EUTF: the outsourcing of major border control functions to private actors is the very first step that determines the convoluted implementation of externalisation policies on the ground. Besides, as most of the companies involved are active in the Italian and international defence and security industry, the risk that they might end up shaping migration as primarily a security problem in order to benefit from the European and Italian policy of containment, is real (Baird Citation2018).

The added complexity of the Libyan context: mercenaries, smugglers and militias

Although the outsourcing of important border control functions to commercial actors is already a major cause of the intricacy of the migration industry stemming from the EUTF, the Libyan context adds a further layer of complexity. Indeed, the borders are not controlled by a unitary state-actor, but instead are managed by a number of factions, military forces from several states, numerous militias and groups of foreign armed security guards and mercenaries. The involvement of non-state private security actors and armed actors in violent conflicts is certainly not a novel phenomenon. Even if our knowledge of the exact role of these actors in the Libyan case is still evolving, numerous reports detail their direct and indirect participation in combat, intelligence gathering, and site and border protection. While data on this is partial, several auxiliary armed groups have supported both the Libyan National Army (LNA) and the Government of National Accord (GNA). The LNA has been supported by several groups, ranging from paramilitary corps like the Petroleum Facilities Guards to tribal groups and foreign mercenaries from Sudan and Russia, whereas the GNA has been supported by armed groups from Chad and thousands of Syrian rebels (Dacrema and Varvelli Citation2020). Indeed, formal and informal links between states such as Russia and companies such as Wagner Group (to name but one example) adds to the notion that many of these foreign firms function at least in part as proxies, serving commercial and external political interests (see e.g. Petersohn Citation2019; Colton Citation2019; Reynolds Citation2019). Besides, many armed groups were integrated into both the detention and coast guards (DCIM and LCG) and are now part of the official state system (Okoli Citation2018). Given the mismatch between the official security structure and the reality on the ground, establishing the extent to which the provision of border security services financed by the EU is in control of the relevant ministries targeted by the project, or is managed by non-state armed groups, militias and foreign actors is almost impossible to ascertain. Likewise, attributing responsibility for the outcomes of EU border externalisation policies is challenging.

In this sense, the presence of a diversified and complex migration and security industry shapes the outcome of border security outsourcing in ways that raise doubts about the long-term sustainability of IBM and similar projects. As stated in the documents, the EU focuses a great deal on granting Libyan ownership by ‘ensuring the full buy-in of the relevant [local] authorities, as well as at enhancing, in a gradual way, Libyan autonomous capacity and ownership’ (Action Fiche Citation2017, 14). However, the lack of a solid ‘chain of command’ in the Libyan security sector is likely to result in a misuse of the equipment and in possible collusion between the intended beneficiaries of the EUTF and other hybrid forces (Action Fiche Citation2017, 12). For instance, some have observed how EUTF funds are directly channelled to smugglers in exchange for halting boats departing from Libyan shores (Bajec Citation2018; Concord and Cini Citation2018). Furthermore, as the government in Tripoli has enlisted militias implicated in smuggling, a flow of money between the EU/Italy, the GNA, militias and smugglers de facto happens in plain sight. Against this backdrop, many smugglers want to be recognised as legitimate actors in the migration industry, striving to convert their activities into anti-smuggling business to attract European resources. As Herbert (Citation2019) as shown, the involvement of this mix of statutory forces, hybrid forces and armed groups risks slowing down the emergence of a functioning Libyan security sector and contribute to the extreme power fragmentation in the country. Hence, although a project like IBM might serve the short-term goal of halting migration flows, the strategy might backfire in the long run. In fact, according to recent UNSC meetings, the presence of armed groups in Libya is a cause of major instability and is exacerbating the political and humanitarian crises in the country, including for migrants (UNSC Citation2020).

Furthermore, the implementation of a project like IBM in such an environment can hardly happen without trampling on migrants’ rights (Concord and Cini Citation2018; Loschi, Raineri, and Strazzari Citation2018; HRW Citation2020). Although the EU claims that IBM contributes to ameliorating the human rights situation in the country by ensuring that the actors targeted are fully compliant with international obligations and standards (Action Fiche Citation2017, 8–9, 14), several sources report how militias, smugglers and Libyan authorities alike are involved in the most serious abuses against migrants’ rights (Mannocchi Citation2017; Concord and Cini Citation2018). As shown by Flanagan (Citation2020), migrants become an important source of income and support for non-state armed groups: on the one hand, they are encouraged to resort to smugglers, which are variously linked with the armed groups; on the other they are used either as human shields to protect military objectives or as forced labour to militias. Notwithstanding the pledge to deliver HR courses and to improve the conditions of migrants, IBM has done little in this direction. From the documents available, no HR training course has been delivered. Moreover, evidence on the ground suggests that HR training is not effective in such a context, especially if they are reduced to a few hours (Loschi, Raineri, and Strazzari Citation2018).

Against this backdrop, it is clear that the outsourcing of security in Libya and the evolving migration industry might create negative outcomes that are neither predicted nor adequately prevented. One of the main reasons for that is the lack of appropriate monitoring and oversight mechanisms. As noted in the introduction, opaqueness and messiness are in the very nature of this complex blended financial instrument. In theory, the EUTF comprises a three-level monitoring mechanism: for each specific programme, for each region (North Africa, Horn of Africa and Sahel and Lake Chad), and for the EU Trust Fund for Africa as a whole. However, the publicly available monitoring reports for both the regional and general level, as well as the publicly available platform AkvoFootnote18 say very little about the actual outcomes of these projects (Welfens and Bonjour, Citationforthcoming). At the same time, the difficulties encountered in accessing relevant documents is further testament of the lack of transparency of these projects. For IBM, a consistent part of the monitoring system relies on the Italian law enforcement and Coast Guard staff deployed to Libya on long-term missions. Accordingly, they play a key role in ensuring that ‘technical means and equipment supplied under the project will be used in a proper manner and for the project purposes only’ (Action Fiche Citation2017, 17). However, although Italian and European authorities are aware of the risks of a loose monitoring in such a volatile environment, they lack the willingness or the power to prevent the emergence of the extremely diversified and intricate migration and security industry described above.

Conclusions

In this paper, we have shed new light on the way in which the EU implements its migration policies in a complex environment (Libya) through a specific instrument (EUTF), mapping and analysing the conglomerate of actors involved in this process. As shown in our analysis, the outsourcing of border security has created a highly fragmented migration industry, comprising a complex network of state and non-state actors, private and public authorities, foreign and local players with partially overlapping (and sometimes conflicting) interests and roles. In a context like Libya, this border security landscape has reached a level in which traditional distinctions between state and non-state, public and private, domestic and foreign become difficult to maintain. Drawing from the fields of Migration and Private Security Studies, our research has shown how border control, traditionally a state function, has gradually involved an increasing array of commercial, non-state and third-state actors, without necessarily leading to a retreat of the state. As in the case of the IBM project, the state still plays a crucial role, although not necessarily the central or most important one. Indeed, our paper has added to the concept of the ‘migration industry’ (Gammeltoft-Hansen and Nyberg-Sørensen Citation2013) by including a variety of state (Italy, Europe), non-state (private companies, mercenaries, smugglers, militias), and third-state entities (Libya). This variety of actors with sometimes different and opposite goals, influences the governance of migration, from agenda setting and negotiation to implementation and enforcement activities.

In Libya, commercialisation and outsourcing are clearly key aspects of migration management. Indeed, the externalisation of border security cannot be decoupled from a market logic whereby European funds, like the EUTF and many others, attract local authorities, private security companies and militias. In this sense, private companies greatly benefit from a border business that elevates them to the role of border security experts and award them with remunerative contracts for the provision of both equipment and services. At the same time, the Libyan militias and armed groups that gravitate in a more or less official way around the authorities, make profit either from smuggling migrants and enlisting them in their armies, or by being recognised as legitimate interlocutors. When they succeed in presenting themselves as important stakeholders in the management of migration, they also benefit from part of the migration industry. Needless to say, in the pursuit of European funds, many local actors have radically different beneficiaries in mind than those identified by the EU. These dynamics stand at the basis of the extremely flourishing migration industry that we have analysed throughout the paper. Because of the impossibility to clearly separate the different roles and responsibilities of the several actors involved in IBM, neither the EU nor Italy can be clearly held accountable for the outcome of externalisation practices.

The systemic failures of the rule of law in Libya, the impossibility for a unitary government to control the whole territory, the foreign interests involved and the collusion between Libyan authorities, traffickers and militias severely hinder the sustainability of European migration governance. This work also sheds some additional light on the opaque nature of the EUTF and related projects. Indeed, the lack of transparency on the use of the resources indicates structural deficiencies in the way the fund works and complicates our overall understanding of European migration governance. As demonstrated by the difficulty encountered in accessing information and documents, EU citizens, scholars and CSOs are de facto prevented from monitoring the moral and political accountability of the European Commission and EU governments. Given the impossibility to access all the documents and trace all the money allocated for this project, our study is able to offer only a partial picture of the reality on the ground. Yet, our findings demonstrate the complexity of global security networks related to border security outsourcing and pave the way for further research. Although the specific results of our analysis concern the Libyan case, analytically, we could expect similar dynamics to be observed elsewhere. For instance, Tunisia and Morocco have also been major beneficiaries of EUTF integrated border management projects which closely resembles IBM, both in terms of scope and actors involved.Footnote19 Indeed, whenever migration management its outsourced, the EU is likely to contribute to the creation of several (sometimes overlapping) migration industries, each with different degrees of complexity. In this sense, the migration industry that emerges from our analysis definitely stands out for its complexity, but is by no means the only one. In light of this, and as externalisation and outsourcing policies are proliferating in Europe and elsewhere, migration experts should continue to investigate these practices and their consequences in different contexts.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our earnest gratitude to the anonymous reviewers and to Joseph Trawicki Anderson, Anja Karlsson Franck and Darshan Vigneswaran for their invaluable feedback and comments on earlier versions of this text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The EU justified the total or partial denial of access to documents according to Regulation 1049/2001 on the following grounds: protection of the public interest as regards public security, protection of the public interest as regards international relations, commercial interests of a natural or legal person, protection of the privacy and integrity of the individual. In particular we received the following explanation: ‘Some of the documents identified, or parts thereof, contain concrete information whose disclosure would put at risk not only staff, partners and contractors but also project target groups […] The full public disclosure of the documents would severely affect the international relations between the EU and the Libyan authorities, given the content of the documents which provide insight into relevant actors’ involvement and decision-making on the ground […] Disclosing such documents, which were not designed for external communications purposes, might lead to misunderstandings and/or misrepresentations regarding the nature of the EU-funded activities in Libya’. At the Italian level, the total of partial denial of access to documents was justified by claiming that documents that concern international relations and police cooperation with third countries cannot be made public and are not subjected to transparency requirements, as they might jeopardise relations with Libya and the EU (D.Lgs 33/2013, Legge 241/1990, D.M. 415/1994). We appealed this decision to the Transparency and anti-Corruption Department of the Ministry of Interior, which nevertheless confirmed the denial.

11 Document released by the MoI to ASGI in 2019 and obtained by email on April 2020.

14 For instance, the majority of disclosed calls for bids to cooperate with the Libyan authorities to ‘combat illegal migration’ have been awarded to Cantiere Navale Vittoria. See for instance: https://www.poliziadistato.it/articolo/15175af41df132993583695306; https://www.poliziadistato.it/articolo/15175a5cd6f53075d747192469; https://www.poliziadistato.it/articolo/15175e566c0bd9b8c105097434; and https://www.poliziadistato.it/articolo/1621596de2c09d184096733536 for the reparation of some vessels; https://www.poliziadistato.it/articolo/15175af44149be401619474581; https://www.poliziadistato.it/articolo/15175b1575b1e41c1724987231; for the transportation of repaired vessels from Tunisia to Libya; https://www.poliziadistato.it/articolo/15175b157297de991651355303 for the training of the Libyan Coast Guards.

15 https://altreconomia.it/litalia-ripara-altre-tre-motovedette-delle-milizie-costiere-della-libia-per-fermare-i-migranti/ and https://www.poliziadistato.it/statics/28/determina-servizio-conduzione.pdf.

18 See: https://eutf.akvoapp.org/, accessed 15 April, 2021.

References

- Abrahamsen, R., and A. Leander. 2015. Routledge Handbook of Private Security Studies. London: Routledge.

- Abrahamsen, R., and M. Williams. 2011. Security Beyond the State: Private Security in International Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ackerman, A. R., and R. Furman. 2013. “The Criminalization of Immigration and the Privatization of the Immigration Detention: Implications for Justice.” Contemporary Justice Review 16 (2): 251–263.

- Action Fiche. 2017. Support to Integrated Border Management-First Phase. https://ec.europa.eu/trustfundforafrica/region/north-africa/libya/support-integrated-border-and-migration-management-libya-first-phase_en.

- Akkerman, M. 2016. “Border Wars: The Arms Dealers Profiting from Europe’s Refugee Tragedy.” Transnational Institute (TNI) and Stop Wapenhandel. https://stopwapenhandel.org/borderwars.

- Anderson, J. T. 2019. “The Migration Industry and the H-2 Visa in the United States: Employers, Labour Intermediaries, and the State.” International Migration 57 (4): 121–135.

- Andersson, R. 2014. Illegality, Inc. Clandestine Migration and the Business of Bordering Europe. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Andrijasevic, R., and W. Walters. 2010. “The International Organization for Migration and the International Government of Borders.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 28 (6): 977–999.

- Arbogast, L. 2016. Migrant Detention in the European Union: A Thriving Business. Paris and Brussels: Migreurop and Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung. www.migreurop.org/IMG/pdf/migrant-detention-eu-en.pdf.

- Baird, T. 2018. “Interest Groups and Strategic Constructivism: Business Actors and Border Security Policies in the European Union.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (1): 118–136.

- Bajec, A. 2018. “Working to Control Migration Flows: Italy, Libya and Tunisia.” Aspenia Online, November 9. https://aspeniaonline.it/working-to-control-migration-flows-italy-lybia-and-tunisia/.

- Berndtsson, J. 2017. “Combining Semi-Structured Interviews and Document Analysis in a Study of Private Security Expertise.” In Researching Non-State Actors in International Security, edited by A. Kruck, and S. Schneiker. London: Routledge.

- Berndtsson, J., and C. Kinsey, eds. 2016. The Routledge Research Companion to Security Outsourcing. London: Routledge.

- Berndtsson, J., and M. Stern. 2011. “Private Security and the Public–Private Divide: Contested Lines of Distinction and Modes of Governance in the Stockholm-Arlanda Security Assemblage.” International Political Sociology 5 (4): 408–425.

- Betts, A. 2011. Global Migration Governance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carrera, S., L. Den Hertog, J. Nuñez Ferrer, R. Musmeci, L. Vosyliūtė, and M. Pilati. 2018. Oversight and Management of the EU Trust Funds. Policy Department for Budgetary Affairs. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_STU(2018)603821.

- Castillejo, C. 2017. “The European Union Trust Fund for Africa: What Implications for Future EU Development Policy?” Briefing Paper, No. 5/2017, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn.

- Cohen, N. 2020. “Israel’s Return Migration Industry.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1752638.

- Colton, T. J. 2019. “Are the Russians Coming? Moscow’s Mercenaries in Comparative Perspective.” Journal of Future Conflict 1 (1): 1–25.

- Concord & Cini. 2018. Partnership or Conditionality? Monitoring the Migration Compacts and EU Trust Fund for Africa. concordeurope.org > wp-content > uploads > 2018/01.

- Cuttitta, P. 2018. “Repoliticization Through Search and Rescue? Humanitarian NGOs and Migration Management in the Central Mediterranean.” Geopolitics 23 (3): 632–660.

- Dacrema, E., and A. Varvelli. 2020. “Le relazioni tra Italia e Libia: interessi e rischi.” ISPI online, July 9. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/le-relazioni-tra-italia-e-libia-interessi-e-rischi-26883.

- Davitti, D. 2019. “The Rise of Private Military and Security Companies in European Union Migration Policies: Implications under the UNGPs.” Business and Human Rights Journal 4 (1): 33–53.

- EC. 2013. Trust Funds. https://ec.europa.eu/international-partnerships/trust-funds_en.

- ECA. 2018. European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa: Flexible but Lacking Focus. https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/DocItem.aspx?did=48342.

- Flanagan, D. 2020. “Caught in the Crossfire: Challenges to Migrant Protection in the Yemeni and Libyan Conflicts.” Journal on Migration and Human Security 8 (4): 318–331.

- Frowd, P. 2018. Security at the Borders Transnational Practices and Technologies in West Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. 2006. “Outsourcing Migration Management: EU, Power, and the External Dimension of Asylum and Immigration Policy.” DIIS Working Paper 1:15.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. 2013. “The Rise of the Private Border Guard: Accountability and Responsibility in the Migration Control Industry.” In The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration, edited by T. Gammeltoft-Hansen, and N. Nyberg-Sørensen, 128–151. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T. 2016. “Private Security and the Migration Control Industry.” In Routledge Handbook of Private Security Studies, edited by R. Abrahamsen, and A. Leander, 207–215. London: Routledge.

- Gammeltoft-Hansen, T., and N. Nyberg-Sørensen. 2013. The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration. New York: Routledge.

- Harney, R. F. 1977. “The Commerce of Migration.” Canadian Ethnic Studies/Études Ethniques du Canada 9: 42–53.

- Herbert, M. 2019. “Policy Brief: Less Than the Sum of Its Parts, Europe’s fixation with Libyan Border Security.” Institute for Security Studies, May 27. https://www.mattherbert.org/lalinea/2019/6/5/less-than-the-sum-of-its-parts-europes-fixation-with-libyan-border-security.

- Herrero Cangas, A., and A. Knoll. 2016. “The EU Trust Fund for Africa: A New EU Instrument to Accelerate Peace and Prosperity?” GREAT Insights Magazine 5 (1), February. Brussels: European Centre for Development Policy Management.

- Hönke, J. 2013. Transnational Companies and Security Governance. Hybrid Practices in a Postcolonial World. London: Routledge.

- Human Rights Watch. 2020. “EU: Time to Review and Remedy Cooperation Policies Facilitating Abuse of Refugees and Migrants in Libya.” https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/04/28/eu-time-review-and-remedy-cooperation-policies-facilitating-abuse-refugees-and.

- Kalir, B., C. Achermann, and D. Rosset. 2019. “Re-Searching Access: What Do Attempts at Studying Migration Control Tell Us about the State?” Social Anthropology 27: 5–16.

- Keukeleire, S., and J. MacNaughtan. 2008. The Foreign Policy of the European Union. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kipp, D. 2018. “From Exception to Rule: The EU Trust Fund for Africa.” SWD Research Paper 13. https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/eu-trust-fund-for-africa.

- Lavenex, S. 2008. “A Governance Perspective on the European Neighbourhood Policy: Integration Beyond Conditionality?” Journal of European Public Policy 15 (6): 938–955.

- Leander, A. 2005. “The Market for Force and Public Security: The Destabilizing Consequences of Private Military Companies.” Journal of Peace Research 42 (5): 605–622.

- Lemberg-Pedersen, M. 2018. “Security, Industry and Migration in European Border Control.” In The Routledge Handbook of the Politics of Migration in Europe, edited by A. Weinar A, S. Bonjour, and L. Zhyznomirska, 239–250. London: Routledge.

- Lopez-Sala, A., and D. Godenau. 2020. “In Private Hands? The Markets of Migration Control and the Politics of Outsourcing.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–19. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1857229.

- Loschi, C., L. Raineri, and F. Strazzari. 2018. “The Implementation of EU Crisis Response in Libya: Bridging Theory and Practice.” Working Paper EUNPACK project, 1–31.

- Mannocchi, F. 2017. “Noi, migranti in Libia: ostaggi dei trafficanti, trattati peggio delle bestie.” Espresso, August 1. https://espresso.repubblica.it/attualita/2017/08/17/news/se-questi-sono-uomini-1.307891.

- Menz, G. 2010. “The Privatization and Outsourcing of Migration Management.” In Labour Migration in Europe. Migration, Minorities and Citizenship, edited by G. Menz, and A. Caviedes, 183–205. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Menz, G. 2011. “Neo-liberalism, Privatization and the Outsourcing of Migration Management: A Five-Country Comparison.” Competition & Change 15 (2): 116–135.

- Menz, G. 2013. “The Neoliberalized State and the Growth of the Migration Industry.” In The Migration Industry and the Commercialization of International Migration, edited by T. Gammeltoft-Hansen, and N. Nyberg-Sørensen, 108–127. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Nyberg-Sørensen, N. 2012. “Revisiting the Migration–Development Nexus: From Social Networks and Remittances to Markets for Migration Control.” International Migration 50 (3): 61–76.

- Okoli, R. C. 2018. Proliferation of Armed Militias and Complicity of European States in the Orgy of (Failed) Migration in Libya, 2011–2017. Paper delivered at the 2018 AfriHeritage Conference on the Political Economy of Migration in Africa, Held at the African Heritage Institution, June 28–29.

- Oxfam. 2017. An Emergency for Whom? The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa – Migratory Routes and Development aid in Africa. www.oxfam.org > research > emergency-whom-eu-emergency.

- Pack, J. 2019. “Kingdom of Militias: Libya’s Second War of Post-Qadhafi Succession.” ISPI Online, May 31. https://www.ispionline.it/it/pubblicazione/kingdom-militias-libyas-second-war-post-qadhafi-succession-23121.

- Panebianco, S. 2020. “The EU and Migration in the Mediterranean: EU Borders’ Control by Proxy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2020.1851468.

- Petersohn, U. 2019. “Everything in (Dis)Order? Private Military and Security Contractors and International Order.” Journal of Future Conflict 1: 1–25.

- Reslow, N. 2012. “The Role of Third Countries in EU Migration Policy: The Mobility Partnerships.” European Journal of Migration and Law 14 (4): 393–415.

- Reynolds, N. 2019. “Putin’s Not-So-Secret Mercenaries: Patronage, Geopolitics, and the Wagner Group.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace - Papers.

- Salt, J., and J. Stein. 1997. “Migration as a Business: The Case of Trafficking.” International Migration 35: 467–494.

- Sanchez-Barrueco, M. L. 2013. “The European Union Comprehensive Intervention in Somalia: Turning Ploughs into Swords?” In Globalizing Somalia Multilateral, International and Transnational Repercussions of Conflict, edited by E. Leonard, and G. Ramsay, 227–250. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Sanchez-Barrueco, M. L. 2018. “Business as Usual? Mapping Outsourcing Practices in Schengen Visa Processing.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (3): 382–400.

- Schapendonk, J. 2018. “Navigating the Migration Industry: Migrants Moving through an African-European Web of Facilitation/Control.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (4): 663–679.

- Scholte, J. A. 2004. “Globalization and Governance: From Statism to Polycentrism.” Centre for the Study of Globalisation and Regionalisation, University of Warwick. CSGR Working Paper No. 130/04.

- Sciortino, G. 2004. “Between Phantoms and Necessary Evils. Some Critical Points in the Study of Irregular Migration to Western Europe.” IMIS-Beiträge: Migration and the Regulation of Social Integration 24: 17–43.

- Trauner, F., and S. Wolff. 2014. “The Negotiation and Contestation of EU Migration Policy Instruments: A Research Framework.” European Journal of Migration and Law 16 (1): 1–18.

- United Nations, Security Council. 2020. “As Foreign Interference in Libya Reaches Unprecedented Levels, Secretary-General Warns Security Council ‘Time Is Not on Our Side’, Urges End to Stalemate.” Press Release SC/14243, 8 July.

- Walters, J. 2015. “Migration, Vehicles, and Politics: Three Theses on Viapolitics.” European Journal of Social Theory 18 (4): 469–488.

- Welfens, N., and S. Bonjour. Forthcoming. The Knowledge Politics of Monitoring and Evaluation of the EU Trust Fund for Africa.

- Wong, R. 2007. “Foreign Policy.” In Europeanization New Research Agendas, edited by P. Graziano, and M. Vink, 321–334. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Xiang, B., and J. Lindquist. 2014. “Migration Infrastructure.” International Migration Review 48: 122–148.

- Zanker, F. 2019. “Managing or Restricting Movement? Diverging Approaches of African and European Migration Governance.” Comparative Migration Studies 7 (17): 1–18.

- Zardo, F. 2020. “The EU Trust Fund for Africa: Geopolitical Space Making through Migration Policy Instruments.” Geopolitics. doi:10.1080/14650045.2020.1815712.

- Zaun, N., and O. Nantermoz. 2021. “The Use of Pseudo-Causal Narratives in EU Policies: The Case of the European Union Emergency Trust Fund for Africa.” Journal of European Public Policy. doi:10.1080/13501763.2021.1881583.