?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In this study, we explore whether the economic integration of immigrants may function as a stepping stone to their political integration. We show that there are strong theoretical reasons to expect entrance into the labour market to be pivotal for the political socialisation of immigrants in the new host country and in extension for their opportunities to stand for office. Empirically, we make use of Swedish register data and study whether labour market entrance among refugees affects their chances of being nominated for political office in Swedish municipal councils. We focus on refugees that arrived in Sweden between 1985 and 1994 and explore whether they became political nominees in seven consecutive elections between 1994 and 2014. Our results indicate that getting an early foothold in the labour market has a significant positive effect on the likelihood of running for office. These results hold even when we make use of more exogenous variation in the labour market conditions that refugees encountered when they arrived in Sweden, which provides some support that labour market entrance may have a causal effect on political candidacy among refugees.

Introduction

The number of refugees in the world currently stands at record high levels. At the end of 2020, the UN reported that the worldwide refugee population had reached above 26 million people (UNHCR Citation2021). The great majority of these refugees are hosted by countries in the Global South, but in recent decades there has also been an increased inflow of refugees to affluent Western countries. As a result, the economic and political integration of refugee immigrants is now portrayed as a critical policy challenge in many established democracies.

Judging from available empirical evidence, however, most countries still have a long way to go towards achieving full economic and social inclusion of immigrants in general and refugees in particular. There is a burgeoning body of research documenting how refugees are underrepresented or disadvantaged in various important spheres of society. In comparison to natives, but also to other types of immigrants, individuals who arrived to their host country as refugees are underrepresented in the labour market (Bratsberg et al. Citation2017; Fasani, Frattini, and Minale Citation2018), are overrepresented among social insurance claimants (Bratsberg, Raaum, and Røed Citation2014, Citation2017), vote to a lesser extent in democratic elections (Wass et al. Citation2015), and are considerably less likely to be elected or nominated for political office (Dancygier et al. Citation2015). However, whereas we begin to have a rather good understanding of the extent to which refugees are underrepresented in specific parts of society, the potential links between the underrepresentation in different spheres remain an understudied topic. The recent study by Bratsberg et al. (Citation2019) represents a partial exception to this current state of affairs. Based on Norwegian data, they argue that economic and political integration are intertwined. They further claim that one important reason for the political underrepresentation of immigrants is that migrants, especially soon upon arrival, have higher returns to work and labour market experience than natives. It is therefore more costly, the argument goes, for immigrants to prioritise politics over working, which makes migrants less likely to seek political office than natives. The argument by Bratsberg et al. (Citation2019) is both innovative and intriguing, but it primarily applies to those immigrants who have been able to secure a footing in the host country’s labour market. In this study, we will add to the previous literature by taking a step back and asking how immigrants’ labour market entrance relates to the speed and degree of their political integration.

It is a fairly widespread perception that immigrant integration in the host country starts in the labour market (e.g. Clark et al. Citation2019). The view expressed in a joint report by the OECD and the EU provides a good case in point:

Jobs are immigrants’ chief source of income. Finding one is therefore fundamental to their becoming part of the host country’s economic fabric. It also helps them – though there is no guarantee – to take their place in society as a whole. (OECD and European Union Citation2015, 79)

The purpose of this study is to examine the latter part of this statement empirically by studying if, and how, finding work helps refugee immigrants to take their place in politics. More precisely, we will study how the timing of refugees’ labour market entrance relates to their subsequent likelihood of being nominated for political office. The main reason for focusing on refugees is that their political underrepresentation constitutes a particularly important problem since they are more likely than other types of immigrants to stay permanently in their new host country (Bratsberg et al. Citation2017, 22). It is, however, also advantageous from a methodological viewpoint as we do not have to deal with the problem that the process of entering the labour market is very different for immigrants who choose to migrate for economic or labour market reasons.

To examine how refugee political representation develops with time of residence and whether this process is related to what happens to the refugees in the labour market, we will make use of high-quality data from Swedish registers. We follow the refugees who immigrated to Sweden between 1985 and 1994 for a period of 20 years and study how their labour market attachment and likelihood to become nominated for political office develop over time.

To preview our results, we find that labour market entrance is strongly related to the probability of becoming nominated for local political office. Immigrants who are able to find work relatively soon upon arrival experience considerably faster and higher political incorporation than those who remain outside the labour market for a longer time. This, however, raises the question of whether the relationship can be given a causal interpretation or if it merely reflects the fact that labour market entrance and entry into politics are governed by the same set of individual characteristics.

In an attempt to make progress on this latter issue, we utilise a refugee placement programme that assigned newly arrived refugees an initial municipality of residence. Because the programme created exogenous variation in refugees’ initial labour market conditions (Åslund and Rooth Citation2007), it can be used to study the causal impact of these conditions on their long-term political integration. We find evidence that refugees who, upon arrival, were placed in municipalities with stronger labour markets are more likely to eventually become nominated for political office. We argue that this serves to probe that the strong relationship between labour market entrance and the likelihood of entering politics that we uncover in the first part of our analysis is at least partly causal.

The rest of this study proceeds as follows. In the next section we discuss previous literature and elaborate on our argument about the importance of the labour market for immigrant candidacy. Thereafter comes two sections where we explain the institutional setting and the empirical design of our study. In the fourth section we present the empirical results. We then conclude by discussing our findings and their implications.

Theory and previous research

In party-based political systems, the political representation of immigrants is the result of both supply- and demand-side factors (Norris and Lovenduski Citation1995), i.e. for immigrants to appear on party lists two conditions must be met. First, there must be a sufficient number of immigrants who choose to engage in politics and are ready to stand as candidates if asked to do so (the supply side condition). Second, party selectors and gatekeepers must be willing to recruit and nominate these potential candidates with immigrant backgrounds (the demand side condition).

In relation to their significant share of the population, there are relatively few immigrants holding political office in most Western democracies (Bloemraad Citation2013; Dancygier et al. Citation2015). The limited number of immigrants in elected office has spurred an emerging literature on the causes of immigrants’ political underrepresentation. Scholars have explored a number of different explanations related to the supply and demand for immigrant political candidates.

One focus has been to study how parties may act as gate keepers and possible discriminatory practices among parties as well as voters (Dancygier et al. Citation2015; Portmann and Stojanović Citation2019; Van Trappen Citation2021). Another type of explanation instead stresses the role of opportunity structure variables, such as the electoral- and party system, and highlights the different ways in which these macro-level determinants may interact with various individual and group-level characteristics (Dancygier et al. Citation2015; Schönwälder Citation2013). There are also a few studies that have looked into the supply side of immigrant representation and the determinants of immigrant candidacy. Reny and Shah (Citation2018), for instance, find that socio-economic factors, typical determinants of engagement in politics (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995), matter also for immigrants but that psychological barriers related to immigrant identity and self-perception make it particularly difficult for immigrants to run for office. Dancygier et al. (Citation2021), on the other hand, find that immigrants have similar levels of political ambition and interest as natives and argue that the underrepresentation rather depends on party gatekeepers.

Related to this, there is also a more general literature on immigrant political incorporation, typically with a focus on voter turnout, which points to the importance of the political socialisation process (e.g. White et al. Citation2008). More specifically, this literature suggests that immigrants’ adaptation to a new political context is a function of three broad factors: exposure, transferability and resistance (Voicu and Comşa Citation2014; Wass et al. Citation2015).

The first type of explanation maintains that immigrant political integration is primarily a function of the extent of exposure to the political system in the new host country. For advocates of this perspective, length of residence is thus the main driver of immigrant political incorporation, but they also point to the importance of factors such as the extent to which immigrants interact with natives, the degree of immigrant residential concentration, and the extent to which immigrants develop a national attachment to the host country (Bhatti and Hansen Citation2016; Rapp Citation2020; Wass et al. Citation2015; White et al. Citation2008). Transferability instead stresses the past political experiences of immigrants in their country of origin and that political norms and behaviour may carry over to the new country (Black Citation1987; Voicu and Comşa Citation2014; White et al. Citation2008). The third perspective, resistance, is less optimistic and emphasises the difficulties of (re)socialisation into a new political system. This perspective departs from the traditional view of political socialisation as something that takes place early in the life course and that people thereafter are resistant to change, making it harder to adapt to a new political context in a new country (Black, Niemi, and Powell Citation1987; White et al. Citation2008). Resistance is typically seen as increasing with age and time spent in the original country (Wass et al. Citation2015).

While previous studies on the role of the political socialisation of immigrants have mainly focused on the electoral participation of immigrants, this research should also have bearing on immigrants’ political representation. It seems reasonable to expect that immigrants’ adaption to their new political context will affect both their readiness to engage in party politics and the likelihood of party elites entrusting immigrant party members with important political positions. Hence, the process of immigrant political (re)socialisation can impact both the supply- and demand of immigrant political candidates.

The theories discussed above suggest a number of reasons why entering the labour market may be an important stepping stone for immigrants’ political incorporation. A first possibility is that getting a job will imply improved opportunities for immigrants to interact and discuss politics with both natives and other immigrants who are already politically integrated. This is under the assumption that work typically would give access to more diverse social contexts – for instance by meeting colleagues and clients – than what otherwise would be the case for newly arrived immigrants. Discussions with natives and politically integrated immigrants can help improve newly arrived immigrants’ understanding of the host country’s political system and promote their language proficiency. Engaging in paid work also means that immigrants will pay taxes and obtain access to work-related social insurance, which can foster a sense of inclusion and national attachment among immigrants.

Moreover, the workplace may offer opportunities to get in contact with labour unions and representatives from other civil society organisations. These organisations can encourage political discussion, but may also in turn lead to meetings with members of political parties and party representatives. Naturally, there may also be colleagues at the workplace who themselves are actively engaged in party politics and thus may use the workplace for political recruitment.

Lastly, there are also reasons to expect a negative effect of not being able to secure a job. First, from the perspective of the immigrant, many years in the host country without gaining access to the labour market may lead to a general loss of confidence in the host country and its institutions. Such a trajectory may lead to political apathy and alienation from the political system. Even though one might get a job eventually, many years of unsuccessful job seeking may reinforce the resistance to the new political system and make one unwilling to become politically resocialised. Second, party activists and party gatekeepers may see an immigrant’s difficulties in the labour market as a negative signal of political ability and therefore refrain from trying to recruit or nominate someone with such a background.

There is thus strong theoretical reasons to expect a linkage between the economic and political integration of immigrants. This also resonates with what is frequently argued in the economic literature, namely that getting a job early after arrival in the host country is particularly beneficial for immigrants’ long-term integration (e.g. Åslund and Rooth Citation2007). Marbach, Hainmueller, and Hangartner (Citation2018), for instance, found that a shortening of the waiting period after which asylum seekers in Germany could take on work, considerably improved the long-run economic integration of this group. According to Marbach et al., this indicates that:

[T]he initial period after arrival is highly consequential for the subsequent integration trajectory of refugees, and early investments yield disproportionate integration returns. (2018, 4)

Ferwerda, Finseraas, and Bergh (Citation2020) leverage a similar argument regarding the political integration of immigrants by reasoning that early access to voting rights in the new host country positively affects immigrants’ subsequent trajectory of political incorporation (but see Engdahl, Lindgren, and Rosenqvist Citation2020). There is also a long tradition in political scholarship to connect political participation to resources that typically are acquired through work, such as money and civic skills (e.g. Schlozman, Burns, and Verba Citation1999; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995).

To sum up, we believe that there are substantial theoretical reasons to expect the labour market to be conducive for the political integration of refugees. There is also evidence from previous literature on the connection between early labour market entrance and the economic integration of refugees as well as on the connection between work and political participation in general. Against this backdrop, we reason that both the extent and speed with which immigrants enter the labour market can have consequences for their subsequent political integration. Ultimately, this is, however, an empirical question, but systematic empirical studies on this topic are still largely missing. In what remains of this article, we will attempt to help remedy this situation by utilising high-quality data from Swedish population registers to study the linkage of economic and political integration. One important reason for situating our study in Sweden is thus data availability; however, as we describe in the next section, another advantage of studying the Swedish context is that it offers certain institutional and contextual features that can be used for identification purposes.

Immigration and representation in Sweden

Sweden’s history of migration is similar to that of many other European countries. During the 1950s and 1960s, immigration to Sweden was dominated by labour migrants, primarily from Finland but also from Central and Southern Europe. However, labour migration to Sweden came to a halt during the 1970s due to a combination of stricter immigration rules and decreased demand for labour. From the late 1970s, immigration to Sweden has instead been dominated by refugee and family migration (Dancygier et al. Citation2015; Vogiazides and Mondani Citation2020). Currently, about one-fifth of Sweden’s population is foreign born.

The economic integration process is typically more drawn-out for refugees than for labour migrants. Sweden is no exception in this regard, but differences in employment and wages between economic and humanitarian migrants are somewhat less pronounced than in other Western countries (Brell, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2020; for further details on economic integration in Sweden, see Bevelander Citation2011). Research has typically explained diverging economic integration patterns for different types of migrants by differences in selection (e.g. Chiswick Citation1999). Selection may also occur across host countries and there is some evidence that refugees coming to Sweden are more negatively selected compared to refugees coming to the US and Israel (Birgier et al. Citation2018).

One side effect of the changing nature of immigration to Sweden during the 1970s was that the inflow of new immigrants became even more concentrated to certain regions, especially to the larger cities. In order to address this problem, the Swedish government introduced a refugee placement policy in 1985 (Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund Citation2003). The basic idea behind the policy was that asylum seekers should be distributed more equally between different municipalities and speed up the integration process. To achieve this, the policy implied that refugees would no longer have the right to settle according to their own preferences; instead, the Swedish Immigration Board assigned all newly-arrived asylum seekers to an initial municipality of residence. When the placement programme was first put in place, the Immigration Board was supposed to consider factors such as educational and labour market opportunities when deciding on refugee placement, but fairly soon housing availability became the main deciding factor. Moreover, there was no interaction between local Immigration Board officers and individual refugees in the placement process, which further reduced the opportunity for asylum seekers to affect their placement (Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund Citation2003).

The fact that the Swedish placement programme induced an element of randomness in refugee settlement has made it popular among researchers. Following the seminal study by Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund (Citation2003), the placement programme has been used to examine a wide range of economic and social outcomes (e.g. Åslund and Fredriksson Citation2009; Dahlberg, Edmark, and Lundqvist Citation2012). Recently, the placement programme has also been used to study the impact of ethnic concentration on political candidacy (Lindgren, Nicholson, and Oskarsson Citation2021) and turnout (Andersson et al. Citation2021). However, the work by Åslund and Rooth (Citation2007) is of particular relevance for the present analysis. Their study utilises the placement programme, in combination with the unexpected economic recession hitting Sweden in the early 1990s, to examine how initial labour market conditions affect the economic integration of refugees.

The economic crisis was both deep and prolonged. Sweden experienced negative growth rates for three consecutive years between 1991 and 1993, and open unemployment increased from about 2 to 12 per cent. However, whereas the recession hit all parts of Sweden, there was still geographical variation regarding both the timing and the depth of the crisis. Consequently, the refugees arriving to Sweden during late 1980s and early 1990s met very different local labour market conditions, depending on when and where they were placed. This is the variation exploited by Åslund and Rooth (Citation2007), who found that refugees that were placed in municipalities with higher unemployment rates suffered lower wages and employment for at least a decade following their immigration.

With respect to the political context, we will focus on the political representation of immigrants at the local level. The main reason for this is that there is no citizenship requirement for holding local office. All individuals who are either citizens or who have lived in Sweden for at least three years prior to the election day are eligible to vote and stand as a candidate in the municipal elections. During the study period, the number of municipalities increased from 284 to 290 and each municipality is governed by a municipal council. Municipal elections are held every fourth year (every third before 1994), on the same day as the election for the national parliament, and the municipal council is elected using a party-list proportional system. Swedish municipalities play an important role in the production of public welfare services, and they have independent taxation rights.

Previous research has shown that immigrants in general, and refugees in particular, are underrepresented in Swedish municipal councils (Dancygier et al. Citation2015; Folke and Rickne Citation2015). For instance, Dancygier et al. (Citation2015) report that in 2010, refugee immigrants were only 40 per cent as likely to be elected to local council as were natives.

Data and methods

Data for this study are drawn from Swedish public registers and focus on individuals born in refugee sending countries, who immigrated to Sweden between 1985 and 1994. The time period is chosen as these were the years when the refugee placement programme was active. Ideally, we would have liked to identify refugee status directly from the data, but unfortunately no such information is available in the registers at our disposal. We therefore follow the approach used by Åslund and Fredriksson (Citation2009) and focus on immigrants born in Non-Western countries, here defined as those not being members of the OECD as of 1985.Footnote1 For reasons of confidentiality, the country of birth variable has been grouped in 16 distinct groups. For immigrants from significant sending countries (e.g. Iran and Iraq), the region code is that of the country, but smaller sending countries are grouped together with their neighbours (see the Supplemental material, section A.1, for the included groups/countries). The fact that slightly more than half of the immigrants in our sample come from Former Yugoslavia, Iran, and Iraq – which all suffered from military conflicts during the study period – corroborates the view that the immigrants in our sample are primarily refugees (the country composition of the sample is reported in Table A.1 of the Supplemental material).

The purpose of this study is to examine the link between economic and political integration, which means that we will need to operationalise both of these much discussed concepts. With respect to the former concept, we will focus on immigrants’ labour market entry, which is a commonly used indicator of immigrant economic integration (e.g. Bratsberg et al. Citation2017; Marbach, Hainmueller, and Hangartner Citation2018).

We will follow the approach used by Åslund et al. (Citation2006) and classify an immigrant as having entered the labour market once he or she has received annual earnings in excess of half the median annual earnings of a 45 year-old. This threshold is sufficiently high to rule out short temporary jobs, but still sufficiently low to capture low-paid full-time jobs held during substantial parts of a year. Based on this definition, there is no way to un-enter the labour market, i.e. an individual is classified as having entered the labour market even if he or she later become non-employed. However, previous empirical research indicates that the great majority of the immigrants continue to be employed once they have entered the labour market (see e.g. Bratsberg et al. Citation2017, 124). Finally, we restrict our attention to individuals who were in working age at the time of immigration, here defined as aged between 18 and 55 upon arrival.

Turning to the issue of political integration, our focus will be on immigrant political representation. More precisely, we will examine the extent to which refugees arriving in the period 1985–1994 appeared as candidates on party lists for municipal councils in the seven elections held between 1991 and 2014. We have both theoretical and methodological reasons for choosing to study the likelihood of becoming nominated to political office, rather than the likelihood of being elected. Theoretically, recent research indicates that the major hurdle for immigrant political representation in Sweden lies in translating their political interest and motivation into a nomination for elected office (Dancygier et al. Citation2021). Methodologically, the number of nominated individuals is about four times as many as the number of elected individuals, which helps improve statistical precision.

Finally, to say that a specific group, such as immigrants, are politically underrepresented requires that the actual representation of the group is compared to some theoretical or empirical benchmark. In this study, we will address this problem by comparing refugee immigrants to natives with similar characteristics. Thus, we consider immigrants as underrepresented to the extent that they are less likely to be nominated to municipal councils than are comparable natives (we will return to the exact meaning of this in the next section).

Empirical strategy

The purpose of this study is to examine whether economic and political integration is intertwined so that immigrants’ labour market experiences are related to the speed and degree of their political integration. To do this, we will adapt the assimilation model of Borjas (Citation1985), which has been widely used in economics and sociology to study how the immigrant-native wage gap varies with time since migration (Borjas Citation1985; Villarreal and Tamborini Citation2018).

The basic idea of the Borjas model is to estimate separate earnings equations for immigrants and natives. Apart from the standard set of variables included in the earnings equation, immigrant earnings are allowed to depend both on time of arrival and the number of years that an immigrant has resided in the host country. It is thereby possible to examine whether immigrants’ earnings converge to those of natives over time.

Adapted to the present case, the two regression equations can be expressed as follows:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2)

where the superscripts I and N refer to Immigrants and Natives, respectively; yi,t is a binary indicator that takes the value of 1 if individual i is nominated to municipal council in year t, Ti,t gives the number of years an immigrant has resided in the host country, Ci,t identifies year of immigration, Ai,t indicates an individual’s age at the time of the election, Yi,t represents period effects (year of election), and Xi,t is a vector of other variables affecting the likelihood of nomination.

For estimation purposes, the two equations of the Borjas model is typically estimated simultaneously by pooling the sample and interacting all immigrant-specific variables with an immigrant dummy. To avoid perfect multicollinearity and achieve identification, it is also necessary to put some type of restrictions on the parameters of T, C, A, and the standard approach in the previous literature is to constrain the parameter of the period effect to be the same for immigrants and natives (i.e.

).

By using this empirical set-up, it is possible to study how the political representation of immigrants develops with time of residency compared to that of natives. However, a key difficulty in implementing this approach is how to make sure that immigrants are compared to a relevant set of natives. Our solution to this problem is to compare the political trajectory of immigrants to similar natives who lived in the municipality in which the immigrants were placed upon arrival. Similar is here operationalised as having the same birth year, sex and educational attainment. Accordingly, and as described in more detail in the Supplemental material, we stack our data and create groups based on all unique combinations of (initial) municipality, sex, year of birth and educational attainment. Each refugee immigrant is included in one such group, whereas a native can be included in multiple groups since they can serve as ‘controls’ for refugees arriving in different years. In the final stage we then use the unique personal identifiers in our data to merge on relevant data for each of the seven election years. However, the last election for which we have data is in 2014, which means that we can follow those immigrating in 1994 for 20 years. We have therefore decided to restrict our attention to the first 20 years since immigration, although it is possible to follow the early immigration cohorts for a longer time period.

Having constructed the data in such a way, our baseline model can be expressed as follows:

(3)

(3) where the subscript g indicates the comparison groups discussed above, Di,g,t is an immigrant indicator, and δg is a group-specific effect. This effect implies that each immigrant is only compared to a group of similar natives. In our baseline specification we do not include any additional controls in Xi,g,t.

If we use a logit model to estimate Equation (3) we can get a direct measure of how the political underrepresentation of immigrants varies by time of residence by interpreting the logit coefficients in terms of odds-ratios. A particular attractive feature is that for rare outcomes such as the one here under study, the odds-ratio will approximate the risk-ratio, which is an even more intuitive measure of underrepresentation. More formally, if we apply a logit model we, have:

If we find that OR = .5 at time τ, this means that an immigrant who has resided in Sweden for τ years is (approximately) 50 per cent as likely to be nominated to municipal council as a native in his or her comparison group (i.e. δg).

To study how the political underrepresentation of the refugees varies with their labour market entrance, we can then either estimate Equation (3) separately for different subgroups defined by their labour market status, or we can estimate the model in the pooled sample by interacting all immigrant-specific variables with their labour market status.

However, a limitation with these two approaches is that it will be difficult to discern whether a difference in the likelihood of political candidacy depending on labour market status represents a causal relationship. That is, there is a risk that the same set of characteristics that facilitates labour market entrance among refugees also has a positive effect on the likelihood of political candidacy – and these factors may not be limited to those that we keep constant with the help of our comparison groups (birth year, sex, education and municipality). This is why the refugee placement programme is important for us to more adequately test the causal effect of early labour market entrance. More precisely, because refugees were assigned to different municipalities in an arguably random manner, there should be no systematic differences in the unobserved individual characteristics of the refugees placed in municipalities with strong or weak labour markets. Consequently, if we find a relationship between initial labour market conditions and political representation we can be fairly confident that this relationship is not the result of any unobserved differences in individual refugee characteristics, which considerably strengthens the case for causality.

Finally, to accurately trace how political representation varies with time of residence, it is important to allow for sufficient flexibility in the modelling of time. We will do this by replacing T in Equation (3) with a flexible restricted cubic spline function with five knots (e.g. Beck, Katz, and Tucker Citation1998). The standard errors are clustered on the group indicator used to identify the ‘comparison groups’.

When estimating the logit model we are forced to drop all groups where there is no variation in the outcome (political candidacy). Once we do so we are left with a dataset with 48,610,042 individual-year observations including 2,313,697 unique individuals (76,715 immigrants and 2,236,982 natives).

Empirical results

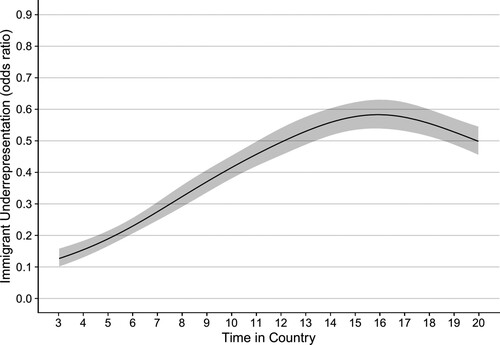

To ease interpretation, all regression results will be presented graphically (but the complete results are available in the Supplemental material). displays how the odds-ratio of immigrant political nomination develops with length of time in country. Given the rareness of nomination, the odds-ratio will in this case mimic the relative probability that an immigrant will appear on a party ticket in comparison with a similar native.

Figure 1. Refugee Underrepresentation by Time in Country.

Note: The line represents odds-ratios and the shaded area 95% confidence intervals. The fixest package in R (Bergé Citation2018) was used for estimation.

As can be seen in , the political underrepresentation of immigrants decreases with time of residence, which is in line with the exposure perspective discussed above. After five years of residency, a refugee immigrant is about 20 per cent as likely as a comparable native to be nominated to a local council. After 15 years, this number has grown to about 60 per cent, but then it seems to start to go down again.

The results presented in indicate that although refugee immigrants are able to narrow the representation gap over time, they remain severely underrepresented even after having lived 20 years in their new host country. However, this overall picture may conceal important subgroup differences. Given the purpose of the present study, we are particularly interested in the extent to which the integration trajectory differs depending on immigrants’ labour market attachment.

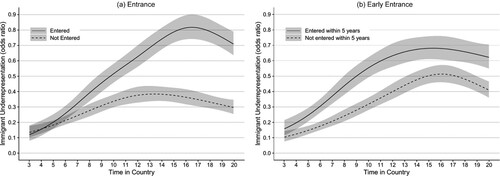

In the next step, we therefore estimate an interaction model to allow different time profiles depending on an immigrant’s labour market status. The left panel of shows the relative underrepresentation for immigrants who have entered the labour market at the time of the election (solid line), and those who have not done so (the dashed line).

Figure 2. Underrepresentation by Labour Market Status.

Note: The line represents odds-ratios and the shaded area 95% confidence intervals.

It is clear from the figure that relative underrepresentation is strongly related to labour market attachment. The relative probability of nomination is similar for the two groups during their initial years in Sweden. However, after 5–6 years, we see that the representation gap between the two groups widens substantially. After 15 years in the country, refugees who have entered the labour market by this time are 80 per cent as likely as the natives to be nominated to local office. For the immigrants who have stood outside the labour market for these 15 years, the corresponding figure is as low as 35 per cent.

In principle, there are two different explanations for why the gap between the two groups increases over time. A first possibility is that the group of non-entrants becomes increasingly negatively selected over time. A second possibility is that early labour market entrance is particularly helpful for refugee integration. As argued in the theory section, long-term exclusion from the labour market may infer resistance to political socialisation in the host country. In parallel with what has been found for economic integration (Marbach, Hainmueller, and Hangartner Citation2018), there might be a time-limited political integration window after arrival to the host country.

In an attempt to examine whether refugees’ political representation is related to the timing of their labour market entrance, the right panel of presents results from a model where we split the refugees in our sample based on whether they were able to enter the labour market within five years from arrival. There are both substantive and methodological reasons to set the early entrance threshold at five years. To be eligible to stand as a candidate in a local election immigrants must have lived in Sweden for at least three years, but the party lists are usually put together one year prior to the election. Consequently an immigrant must have spent at least 4–5 years in Sweden to have a realistic chance to stand as a candidate. Methodologically, we only have access to earnings data from 1990 and onwards. If we set the threshold for early labour market entrance below five years we would thus have to drop the individuals immigrating in the mid-1980s from the analysis. In addition, few refugee immigrants enter the labour market during their first years in Sweden so a shorter time frame would make the sample of early entrants fairly small.

As can be seen, there is a clear tendency that those refugees who were able to enter the labour market relatively soon upon arrival tend to be less politically underrepresented over time. From about seven years and onwards, the relative probability of nomination is 20–25 percentage points higher for the early labour market entrants. It is interesting to note that this difference is fairly constant over time, even though many of the late labour market entrants are able to find work in later years.

The pattern observed in is thus consistent with the view that early access to the labour market is of particular importance for refugees’ subsequent trajectory of political integration. With this being said, it could still be the case, however, that the relationship is due to selection bias, i.e. refugees who enter early and late differ in important regards, and it is these differences that explain their different likelihoods of entering the labour market as well as politics. The question thus still remains whether the observed relationship between economic and political integration can be given a causal interpretation. In the next section, we will try to make some progress on this difficult question by utilising the fact that the refugees under study met very different labour market conditions when arriving to Sweden.

Probing causality: the impact of initial labour market conditions

As discussed above, a refugee placement policy was in place in Sweden during the period 1985–1994. During this time, refugees were thus not free to choose where to locate, but were assigned their initial municipality of residence (although they were free to relocate later). In a previous study, Åslund and Rooth (Citation2007) showed that refugee immigrants who were placed in municipalities with weaker labour markets experienced lower employment and wage growth.

Here, we extend the analysis of Åslund and Rooth (Citation2007) and examine whether initial labour market conditions also affect the political integration of refugees.Footnote2 Towards this end, we interact the immigrant-specific variables in Equation 3 with the employment rate in the municipality where the refugees were placed (measured in the year of placement). Since the refugees were assigned to municipalities in an arguably random manner, the employment rate in their initial municipality of residence should not be related to any unobserved individual characteristics that could otherwise bias the results.

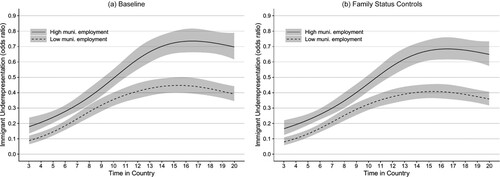

The sub-graph to the left in , labelled baseline, is based on the same model specification as that used for the models displayed in and . However, as noted by Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund (Citation2003), there are some indications that the placement officers may have taken information on the family status of immigrants into consideration when deciding on their municipality placement. In the rightmost sub-graph of , we therefore add controls for an individual’s marital status and number of children, measured at the time of immigration.Footnote3 To ease interpretation, both sub-graphs show the political underrepresentation of refugees placed in municipalities with employment rates one standard deviation above the mean (labelled high municipality employment), and one standard deviation below the mean (labelled low municipality employment).

Figure 3. Underrepresentation by Initial Labour Market Conditions.

Note: The line represents odds-ratios and the shaded area 95% confidence intervals.

The results displayed in are well in line with our previous findings. We see that refugees who were placed in municipalities with stronger labour market conditions, and who were therefore more likely to obtain work relatively soon upon arrival, experience less political underrepresentation over time. For instance, according to the baseline model, after 15 years in the country, a refugee who was placed in a municipality with a high employment rate is three-fourths as likely to become nominated to political office as a similar native, whereas the corresponding figure is only about 45 per cent for a refugee who was placed in a municipality with a low employment rate.

Moreover, and as can be seen from the rightmost sub-graph of , we obtain very similar results when we follow the advice of Edin, Fredriksson, and Åslund (Citation2003) and control for (initial) family status.Footnote4

The results presented in thus indicate that the link between labour market attachment and political representation that we uncovered in the previous section is at least partly causal. The refugee placement programme severely reduces the risk that initial labour market conditions are correlated with unobserved individual characteristics affecting the likelihood of being nominated to political office. There are thus good reasons to expect that the results presented in capture the causal effect of initial labour market conditions on the political underrepresentation of refugees.

Before jumping to conclusions, it is, however, necessary to consider the robustness of the findings. To this end, we have conducted a number of sensitivity checks. For reasons of space, we only provide a brief summary of the most important results from these additional analyses, but full details are given in the Supplemental material.

First, we have investigated how the results change if we lower the threshold for labour market entrance so that an immigrant is taken to have entered the labour market as soon as he or she receives positive labour earnings during a year. When doing so the relationship between labour market entrance and political representation becomes even more pronounced (see Figure A.6). Likewise, we find that the substantive findings remain intact if we lower the threshold for early labour market entrance from five to three years (Figure A.7).

Moreover, we show that the main findings remain if we add controls for other municipality characteristics to the model (see Figure A.1), and when attempting to adjust for the fact that the composition of refugee sender countries changed somewhat over time (see Figure A.2). We also obtain similar results when replacing our continuous indicators of time in country and initial labour market conditions with discrete indicators (see Figures A.3 and A.4). To further reduce the risk that our results are driven by non-refugee immigrants we have also re-estimated the results for the subset of immigrants coming from Iran, Iraq, and Former Yugoslavia, and all results remain very similar when focusing on immigrants from these conflict-ridden countries (Figure A.8).

In our main analyses we have assumed that the relationship between labour market entrance and political representation looks similar for women and men. In a supplementary analysis we have examined the validity of this assumption by splitting our sample by sex. We then find the overall pattern of results to be fairly similar for both sexes. Regardless of the exact measure being used, individuals with stronger labour market attachment experience less political underrepresentation, and this relationship holds true for both women and men. This being said, we find the relationship to be somewhat stronger for men than for women (see Figure A.9).

Ideally, we would also like to uncover the mechanisms driving the relationship between immigrants’ economic and political integration. Unfortunately, this is difficult to accomplish with the data at our disposal. A more detailed analysis of the underlying mechanisms is therefore outside the scope of the present study. However, in the Supplemental material, we provide a simple mediation analysis (see Figure A.5) in which we control for a number of intermediary factors such as citizenship status, socio-economic position, and some, admittedly rough, indicators measuring the opportunities to interact with natives and political insiders. Given the difficulties associated with these types of mediation analyses, the results should be interpreted with great caution, but the analysis gives rise to some interesting findings.

First, and as expected, we find that refugees are much more likely to become nominated to political office if they are Swedish citizens, have high socio-economic status, and are well connected to natives and political insiders. Yet, according to our results these variables are only able to explain about 10–15 per cent of the observed relationship between labour market entrance and political representation. Among the potential mediators that we study the variables measuring the opportunities to interact with natives and political insiders seem most influential to understand the linkage between economic and political integration. Although more research on this is issue is clearly needed before any definite conclusions can be made, these results thus suggest that one reason for why early labour market entrance can improve political representation is that it may facilitate the development of immigrants’ social networks.

Conclusions

The aim of the present study has been to examine whether there is a link between immigrants’ economic and political incorporation. More precisely, we have investigated how entering the labour market affects the political underrepresentation of refugee immigrants. The empirical results provide a fairly clear picture. Although we show that all refugee immigrants are politically underrepresented in relation to natives, even after having spent several decades in the country, the representation gap is considerably less marked for those refugees who manage to secure a footing in the Swedish labour market relatively soon after arrival.

The subsequent analysis using the combination of an unexpected economic crisis and a refugee placement programme to obtain arguably exogenous variation in refugees’ initial labour market conditions further supports these findings. Refugees who were placed in municipalities with strong labour market conditions experience substantially less political underrepresentation over time, which serves to probe that the strong relationship between labour market entrance and the likelihood of entering politics that we uncovered in the first part of our analysis is at least partly causal.

The present study is one of the first to consider how economic and political integration may be interlinked and how the former may determine the latter. In line with the findings of Bratsberg et al. (Citation2019), our results underscore the importance of economic integration also for political incorporation. For policymakers, our findings thus give additional reasons to facilitate early economic integration of immigrants. This is not only important for economic reasons but also for the representation of immigrants in political bodies – and in extension, the legitimacy of the institutions of representative democracy.

Considering the novel character of the literature on the interconnections between different forms of integration, there are many avenues for further research. First, the established relationship between economic and political integration found in this paper, using our Swedish data, needs to be tested also in other countries. Earlier research has shown that country-level institutions may matter for the political incorporation of immigrants, and labour markets also function differently across countries. Furthermore, refugees migrating to Sweden have been found to be more negatively selected relative to refugees coming to some other Western countries (Birgier et al. Citation2018), which may make labour market entry more difficult and possibly more decisive for political integration. On the other hand, the fact that research also suggests that the economic integration process of refugees is comparatively smooth in Sweden (Brell, Dustmann, and Preston Citation2020), could imply that labour market entry rather has a larger impact on the political integration of refugees in other countries. Second, in this study we focused on refugees, but it would also be of interest to explore how the labour market may matter for the political integration of other types of immigrants, maybe in particular family migrants. Their family connections may in one way facilitate political integration but may also imply that they interact less with society at large, which may make the labour market a pivotal factor also for them. Third, and perhaps most important, we need additional studies on the mechanisms related to how getting a job may facilitate political integration. We discussed some potential mechanisms in our theory section, including the role of interactions with natives and politically integrated immigrants as well as political recruitment at the workplace, but it is essential that these are also adequately studied.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (404.7 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Turkey is the only exception from this rule, which is defined as a refugee sending country despite its membership in the OECD.

2 Åslund and Rooth (Citation2007) focus on immigrants arriving between 1987 and 1991, when the placement programme had its strictest implementation. In contrast, we study the entire period during which the placement policy was formally in place, i.e., 1985–1994. This is mainly for reasons of statistical power as the number of nominated refugees in a particular election become very small if we focus solely on the five cohorts immigrating between 1987 and 1991.

3 For the natives in the comparison group these variables are measured in the year(s) when they serve as controls.

4 More precisely, we add a full set of fixed effects for marital status and the number of children to the baseline specification.

References

- Andersson, H., N. Lajevardi, K. O. Lindgren, and S. Oskarsson. 2021. “Effects of Settlement Into Ethnic Enclaves on Immigrant Voter Turnout.” Journal of Politics 84 (1): 578–584.

- Åslund, O., R. Erikson, O. Nordström Skans, and A. Sjögren. 2006. Fritt inträde? ungdomars och invandrades väg till det första arbetet. 1. uppl., 1 tr. Välfärdsrådets rapport 2006. OCLC: 255597094. Stockholm: SNS förl.

- Åslund, O., and P. Fredriksson. 2009. “Peer Effects in Welfare Dependence: Quasi-Experimental Evidence.” Journal of Human Resources 44 (3): 798–825.

- Åslund, O., and D. Rooth. 2007. “Do When and Where Matter? Initial Labour Market Conditions and Immigrant Earnings.” The Economic Journal 117 (518): 422–448.

- Beck, N., J. N. Katz, and R. Tucker. 1998. “Taking Time Seriously: Time-Series-Cross-Section Analysis with a Binary Dependent Variable.” American Journal of Political Science 42 (4): 1260–1288.

- Bergé, L. 2018. Efficient estimation of maximum likelihood models with multiple fixed-effects: the R package FENmlm. CREA Discussion Paper Series 18-13. Center for Research in Economic Analysis, University of Luxembourg.

- Bevelander, P. 2011. “The Employment Integration of Resettled Refugees, Asylum Claimants, and Family Reunion Migrants in Sweden.” Refugee Survey Quarterly 30 (1): 22–43.

- Bhatti, Y., and K. M. Hansen. 2016. “The Effect of Residential Concentration on Voter Turnout among Ethnic Minorities.” International Migration Review 50 (4): 977–1004.

- Birgier, D. P., C. Lundh, Y. Haberfeld, and E. Elldér. 2018. “Self-Selection and Host Country Context in the Economic Assimilation of Political Refugees in the United States, Sweden, and Israel.” International Migration Review 52 (2): 524–558.

- Black, J. H. 1987. “The Practice of Politics in Two Settings: Political Transferability among Recent Immigrants to Canada.” Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue Canadienne de Science Politique 20 (4): 731–753.

- Black, J. H., R. G. Niemi, and G. B. Powell. 1987. “Age, Resistance, and Political Learning in a New Environment: The Case of Canadian Immigrants.” Comparative Politics 20 (1): 73–84.

- Bloemraad, I. 2013. “Accessing the Corridors of Power: Puzzles and Pathways to Understanding Minority Representation.” West European Politics 36 (3): 652–670.

- Borjas, G. J. 1985. “Assimilation, Changes in Cohort Quality, and the Earnings of Immigrants.” Journal of Labor Economics 3 (4): 463–489.

- Bratsberg, B., et al. 2017. TemaNord 2017:520. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Bratsberg, B., G. Facchini, T. Frattini, and A. Rosso. 2019. Are Political and Economic Integration Intertwined? IZA Discussion Papers 12659. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA).

- Bratsberg, B., O. Raaum, and K. Røed. 2014. “Immigrants, Labour Market Performance and Social Insurance.” The Economic Journal 124 (580): F644–F683.

- Brell, C., C. Dustmann, and I. Preston. 2020. “The Labor Market Integration of Refugee Migrants in High-Income Countries.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 34 (1): 94–121.

- Chiswick, B. 1999. “Are Immigrants Favorably Self-Selected?” American Economic Review 89 (2): 181–185.

- Clark, K., et al. 2019. “Local Deprivation and the Labour Market Integration of new Migrants to England.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (17): 3260–3282.

- Dahlberg, M., K. Edmark, and H. Lundqvist. 2012. “Ethnic Diversity and Preferences for Redistribution.” Journal of Political Economy 120 (1): 41–76.

- Dancygier, R. M., K. O. Lindgren, P. Nyman, and K. Vernby. 2021. “Candidate Supply Is Not a Barrier to Immigrant Representation: A Case-Control Study.” American Journal of Political Science 65 (3): 683–698.

- Dancygier, R. M., K. O. Lindgren, S. Oskarsson, and Ka Vernby. 2015. “Why Are Immigrants Underrepresented in Politics? Evidence from Sweden.” American Political Science Review 109 (04): 703–724.

- Edin, P. A., P. Fredriksson, and O. Åslund. 2003. “Ethnic Enclaves and the Economic Success of Immigrants–Evidence from a Natural Experiment.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (1): 329–357.

- Engdahl, M., K. O. Lindgren, and O. Rosenqvist. 2020. “The Role of Local Voting Rights for Non-Naturalized Immigrants: A Catalyst for Integration?” International Migration Review 54 (4): 1134–1157. doi:10.1177/0197918319890256.

- Fasani, F., T. Frattini, and L. Minale. 2018. (The Struggle for) Refugee Integration into the Labour Market: Evidence from Europe. IZA Discussion Papers 11333. Institute of Labor Economics (IZA).

- Ferwerda, J., H. Finseraas, and J. Bergh. 2020. “Voting Rights and Immigrant Incorporation: Evidence from Norway.” British Journal of Political Science 50 (2): 713–730.

- Folke, O., and J. Rickne. 2015. “Vertikal ojämlikhet i kommunpolitiken.” In Låt fler forma framtiden!, SOU 2015:95, 163–187. Stockholm: Wolters Kluwers.

- Lindgren, K. O., M. Nicholson, and S. Oskarsson. 2021. “Immigrant Representation and Local Ethnic Concentration.” British Journal of Political Science. forthcoming.

- Marbach, M., J. Hainmueller, and D. Hangartner. 2018. “The Long-Term Impact of Employment Bans on the Economic Integration of Refugees.” Science Advances 4 (9): eaap9519.

- Norris, P., and J. Lovenduski. 1995. Political Recruitment: Gender, Race, and Class in the British Parliament. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press.

- OECD and European Union. 2015. Indicators of Immigrant Integration 2015: Settling In. OECD.

- Portmann, L., and N. Stojanović. 2019. “Electoral Discrimination Against Immigrant-Origin Can- didates.” Political Behavior 41 (1): 105–134.

- Rapp, C. 2020. “National Attachments and the Immigrant Participation gap.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (13): 2818–2840.

- Reny, T., and P. Shah. 2018. “New Americans and the Quest for Political Office.” Social Science Quarterly 99 (3): 1038–1059.

- Schlozman, K. L., N. Burns, and S. Verba. 1999. “"What Happened at Work Today?": A Multistage Model of Gender, Employment, and Political Participation.” The Journal of Politics 61 (1): 29–53.

- Schönwälder, K. 2013. “Immigrant Representation in Germany’s Regional States: The Puzzle of Uneven Dynamics.” West European Politics 36 (3): 634–651.

- UNHCR, UR. 2021. “Global Trends: Forced Displacement in 2020”. Publisher: UN High Com- missioner on Refugees Geneva, Switzerland.

- Van Trappen, S. 2021. “Steered by Ethnicity and/or SES Cues? An Examination of Party Selectors’ Stereotypes About Ethnic Minority Aspirants.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. Forthcoming.

- Verba, S., K. L. Schlozman, and H. E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Villarreal, A., and C. R. Tamborini. 2018. “Immigrants’ Economic Assimilation: Evidence from Longitudinal Earnings Records.” American Sociological Review 83 (4): 686–715.

- Vogiazides, L., and H. Mondani. 2020. “A Geographical Path to Integration? Exploring the Interplay Between Regional Context and Labour Market Integration among Refugees in Sweden.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (1): 23–45.

- Voicu, B., and M. Comşa. 2014. “Immigrants’ Participation in Voting: Exposure, Resilience, and Transferability.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (10): 1572–1592.

- Wass, H., A. Blais, A. Morin-Chassé, and M. Weide. 2015. “Engaging Immigrants? Examining the Correlates of Electoral Participation among Voters with Migration Backgrounds.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 25 (4): 407–424.

- White, S., et al. 2008. “The Political Resocialization of Immigrants: Resistance or Lifelong Learning?” Political Research Quarterly 61 (2): 268–281.