ABSTRACT

Migration may affect migrants’ ideas as they become exposed to different contexts over time. But how does such exposure and opportunities for comparative evaluation of origin and settlement contexts, translate into content for potential political remittances? To answer this question, we analyse 80 interviews with Polish and Romanian migrants living in Barcelona (Spain) and Oslo (Norway). Starting from the established ‘social remittances’, literature, our contribution is to unpack the process of their formation by focusing on what happens at the content-creation stage. We do so through analysis of migrants’ comparative evaluation of their ‘origin’ and ‘settlement’ contexts in regard to three explicitly political issues: corruption, public institutions and democracy. We analyse how exposure to, and comparative evaluation of, different contexts inform migrants’ views, and find non-linearity and inconsistency between migrant groups’ and in individuals’ own patterns of views. This underscores the salience of, first, recognising how the change that migration prompts in migrants’ outlooks may or may not be stronger than preceding political preferences, anchored in ongoing processes of (re)socialisation; and second, of better understanding how migration impacts migrants’ outlooks, by considering the specifics of exposure and comparative evaluation, whether or not ultimately articulated in forms traceable as ‘political remittances’.

Introduction

How and to what extent migration changes migrants’ perspectives and ideas is far from predictable. While ‘travel broadens the mind’ according to the proverb, the experience of migration does not necessarily change migrants’ political (or other) views in linear ways (Bauböck Citation2003; Fitzgerald Citation2004; Ostergaard-Nielsen Citation2003a, Citation2003b; Smith and Bakker Citation2005). Research using the lens of social remittances (Levitt Citation1998; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Citation2013) that is the ‘normative structures, systems of practice, and social capital’ through which migrants have the potential to influence their societies of origin (Levitt Citation1998, 933), has demonstrated that migration can bring about or feed into the desire and capacity to forge change (Grabowska et al. Citation2017; Horst Citation2018; Lacroix, Levitt, and Vari-Lavoisier Citation2016; Nowicka and Šerbedžija Citation2017; Portes Citation2010; Anghel, Fauser, and Boccagni Citation2019). Recent research looking at migrants’ contributions to specifically political change in origin contexts has employed the newer concept of political remittances, which should be understood as the multidirectional flows of political ideas, practices and principles influenced by receiving and sending contexts (Batista, Seither, and Vicente Citation2019; Ahmadov and Sasse Citation2016a; Hartnett Citation2020; Krawatzek and Müller-Funk Citation2020).

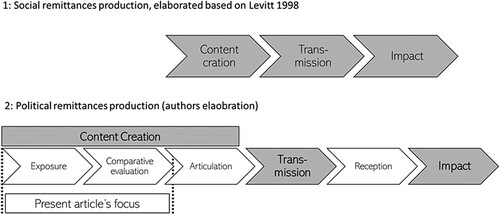

The growing body of research on social remittances highlights the processual and interactional dimensions of exchange and circulation involved (Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Citation2013; see also Boccagni and Decimo Citation2013; Grabowska et al. Citation2017; Nowicka and Šerbedžija Citation2017). The process by which the migration experience can potentially lead to societal change in origin contexts via social or political remittances consists of several steps. These steps were initially conceptualised as content creation, transmission and impact (Levitt Citation1998, see also: ). While essential to the potential for impact of migrant-led change, the refinement and exploration of the first of these steps, has been conspicuously modest in the vast social remittances’ literature (but see Grabowska et al. Citation2017; Grabowska and Garapich Citation2016). Our contribution focuses on what we refer to as the formation of political remittances, with reference to the initial content creation step.

In this article we interrogate the initial process by which they are formed, with relevance, we argue, for the study of political remittances, understood as a subset of social remittances. We ask about the mechanisms through which political remittances come into being. Understanding this necessitates taking a step back and concentrating on migrants’ exposure to different contexts. We thus leave aside both the question of transfer and impact which much research has already conceptualised and investigated, and instead focus on the mechanisms at work in the production of content (i.e. ideas or practices) which may intentionally or unintentionally circulate between places as political remittances.

We aim to add to ongoing debates on political, but also social, remittances by making one central contribution: we unpack the step of content creation. We use the concept of interpretative frames (Levitt Citation1998; Portes and Zhou Citation1993) to explore what happens at the stage of ‘content creation’, where migrants, through comparative evaluations of ‘here’ and ‘there’, contrast and assess different ideas and practices, thus generating content for (potential) political remittances. We argue that while not all of such political content will eventually be transferred and diffuse to homeland contexts, political remittances cannot come into being without the comparative evaluation which gives rise to ideas of difference between ‘here’ and ‘there’, denaturalising old ideas and practices and making the notion of change conceivable.

The paper draws on 80 semi-structured interviews with Polish and Romanian migrants, living in Oslo (Norway) and Barcelona (Spain). During interviews, among other, we asked interviewees to comparatively evaluate their context of origin and destination, along purposefully selected themes. This allows us to address the following questions: How does the content of political remittances come into existence? And more sensitive to the processual dynamics here: How does migrants’ exposure to multiple contexts, and the ensuing processes of comparative evaluation of the political environments’ migrants find themselves in – become the content of what might become political remittances?

We now present our analytical framework, building the case for this article’s specific focus on the content-creation phase of the production of potential political remittances. The subsequent section describes our methods and data. In the analysis we interrogate the formation of potential political remittances by considering how migrants’ ‘interpretative frames’ work – in the process of comparative evaluation of political issues, across two (or more) contexts which migrants are familiar with. We analyse migrants’ comparative evaluations about corruption, public institutions, and democracy. As we show, these contexts are actively drawn on as migrants’ interpretative frames are affected by the migration experience, offering a window into the black box of ‘content creation’ for what might become political (and social) remittances.

Producing political remittances?

Our analytical framework draws on existing work on social and political remittances, and approaches to content creation in the production of these (Levitt Citation1998; Lacroix, Levitt, and Vari-Lavoisier Citation2016; Nowicka and Šerbedžija Citation2017). We foreground migration and the changes which migration may foster in migrants’ interpretative frames, due to exposure to different contexts simultaneously (Portes and Zhou Citation1993). This sets the stage for our analysis where we put the limelight on the process of the formation of potential political remittances by systematically analysing how migrants comparatively evaluate political issues, across origin and settlement contexts. Here, their interpretative frames, shaped by migration experiences, are mobilised. We now discuss each of the building blocks we rely on: first, on social remittances and in particular the process which underlies them; second, recent work on political remittances and in particular what we know about how migration impacts migrants; and third, on migrants’ interpretative frames, in particular on the roles of exposure and comparative evaluation. Together this provides the framework for analysing the process of production of potential political remittances.

Social remittances: grasping elusive empirical mechanisms?

The term ‘social remittances’ was coined more than twenty years ago to highlight that, in addition to money, also ideas, practices, and social capital circulate between migrants’ origin and settlement communities (Levitt Citation1998). These iterative, circulatory exchanges reinforce and are reinforced by other forms of cultural circulation. They are distinct from them, however, because they are conveyed interpersonally between individuals who learn, adapt, and diffuse ideas and practices through their roles in families, communities, and organisations transnationally, drawing on their migration experience (Lacroix, Levitt, and Vari-Lavoisier Citation2016; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Citation2013).

Levitt (Citation1998) defines social remittances as a dynamic process which consists of three phases: content creation, transmission, and impact (Citation1998, 926). Levitt and Lamba-Nieves (Citation2011) later revisit the concept of social remittances, answering critics’ arguments that social remittances do not just move in one direction, but should rather be understood as exchange and circulation of ideas and practices, rather than a unidirectional flow. For our purposes, suffice to acknowledge that social remittances as ideas or practices that are exchanged, may both be intended or unintended, and might also have both intended and unintended effects in the ‘here’ and ‘there’ of the transnational social field.

The vast number of studies on social remittances in the past two decades have largely focused on the transmission and impact dimensions of political and social remittances (Grabowska et al. Citation2017; Lacroix, Levitt, and Vari-Lavoisier Citation2016; Paasche Citation2017). Thus, we know some of the mechanisms of transmission, such as through transnational networks, visits, by use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs), and the potential and limits of these– as well as the possible resistance to migrants’ ideas, but also the impacts which social remittances, often in conjunction with other simultaneous drivers of social change, contribute to (Garapich Citation2016a; Citation2016b; Grabowska et al. Citation2017; Nowicka and Šerbedžija Citation2017; White and Grabowska Citation2019).

However, it is intriguing that the vast number of studies on social remittances have barely started to unpack the actual mechanisms at work in the content creation for these potential exchanges, due to the exposure that the migration experience involves, and how this shapes migrants’ interpretative frames. Therefore, we develop a conceptual approach that allows us to unravel how the content creation part of the formation of what might become social remittances works, which we turn to below. But first we revisit the term political remittances.

Political remittances

Defining political remittances, Krawatzek and Müller-Funk argue that these are: ‘multidirectional flows of ideas and practices, influenced by receiving and sending contexts’ (Citation2020, 1004). In other words, the same sort of transfer and circulation which has been discussed for two decades under the heading of ‘social remittances’. Indeed, it may be argued that political remittances are a subset of the broader category of social remittances, but confined to the realm of the political. Meanwhile, debates on political remittances in migration studies and political science are not new (e.g. Kessler and Rother Citation2016; Nyblade and O’Mahony Citation2014; Tabar Citation2014; Vélez-Torres and Agergaard Citation2014). Much of the interest in political remittances has built on the hypothesis that migration transforms social norms and political views, and more specifically, that political remittances can have a democratising impact. Piper’s definition of political remittances as ‘ideas about democratisation [and] attempts to influence policy in order to democratise unequal power relations’ (Citation2009, 218) equates them with a pro-democratic push. A significant body of research suggests that through settling in a consolidated democracy, migrants from authoritarian states or less consolidated transitional regimes may internalise these values and adopt the practices of their hosts, and in turn ‘remit democracy home’ (Batista and Vicente Citation2011; Chaudhary Citation2018; Fomina Citation2021; Kessler and Rother Citation2016; Pérez-Armendáriz and Crow Citation2010).

However, Itzigsohn and Villacres’s (Citation2008) and Rother (Citation2009) challenge the assumptions about political remittances democratising nature. Migration and the exposure to the country of settlement’s political culture can result in both a critical perspective on politics in the country of origin, and in less support for democratic structures. Rother highlights that migrants’ interpretative frames and the content creation of political remittances in different settlement contexts varies to a great extent, and that the role of migrants’ educational and professional status, both ‘here’ and ‘there’, cannot be overestimated in this context. Furthermore, ideas about political remittances as inherently ‘democratising’ remain trapped in the notion that migrants ‘send back good norms’ from largely Global North to largely Global South contexts, rather than acknowledging ongoing circulation as well as global interconnectedness beyond migration as drivers of social change (Rother Citation2009; see also Kessler and Rother Citation2016; de Haas Citation2010; White et al. Citation2018).

In their effort to summarise the field of political socialisation of immigrants, White et al. (Citation2008), suggest there are three basic approaches; (1) exposure; (2) transferability; (3) resistance, where exposure is taken to mean absorption and adaptation, whereas transferability refers to migrants’ ability and agency in engaging in re-socialisation processes, whereas resistance refers to the innate conservativism of sticking with socialisation from the formative years of youth. Meanwhile studies of political socialisation as an ‘immigrant’ phenomenon, tend to lose sight of the transnational realities which affect many migrants’ lives, and thus do not address this dimension adequately.

More recent empirical contributions indicate that the degree to which migration changes political views varies considerably (Ahmadov and Sasse Citation2016a; Citation2016b). Variation is the norm, with key factors including characteristics of the origin and settlement contexts, and thus, what migrants are exposed to, which also depends on their participation in the settlement countries. Other important factors include levels of education, income levels, as well as migrant’s pre-migration backgrounds, socialisation and political views.

Despite all this variation and non-linearity, it is beyond doubt that at the individual level, migration experiences mark people in manifold ways, including with the potential to affect how they see the world around them. In the next section we therefore turn to explore more specifically how this happens, foregrounding the role of migrants’ interpretative frames, where exposure and comparative evaluation play key parts.

Migrants interpretative frames

We mobilise the idea of interpretative frames (Levitt Citation1998; Portes and Zhou Citation1993) to highlight the ways in which migrants relate to two (or more) contexts in their everyday lives, a foundational insight from the migrant transnationalism literature (Boccagni, Lafleur, and Levitt Citation2016; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Lacroix, Levitt, and Vari-Lavoisier Citation2016; Smith and Bakker Citation2005). Migrants’ interpretative frames reflect that they are (somewhat) familiar with political, economic and social systems across the contexts they live in, due to the everyday exposure which they experience over time. This enables comparative evaluations between contexts, in terms of how things are done, how institutions work, or on norms.

Research on exposure in different contexts of migration has underscored not only the salience of type and degree of exposure to institutional, as well as formal settings, but also to ties with fellow migrants (McGinnity and Gijsberts Citation2016). Furthermore, as Ahmadov and Sasse (Citation2016a; Citation2016b) as well as White et al. (Citation2008) demonstrate, the question of political (re)socialisation is hard to answer in terms of the direction and nature of change which might be anticipated. However, research seems relatively unanimous about the basic fact that being exposed to a ‘new’ context, is likely to have an effect of sorts.

Levitt (Citation1998) builds on Portes and Zhou (Citation1993) to show that migrants’ interpretative frames are affected by their interaction with the society of settlement. This interaction depends on their socioeconomic status and the opportunity structures available to them, and the hypothesis is that the greater the extent of interaction with a settlement society and the exposure to its features, the higher the chances are for more reflection on existing practices and the greater the potential for incorporation of new routines in their own lives. This reflects the typical ‘exposure’ hypothesis (White et al. Citation2008), which could be taken to mean adaptation in an absorbing sense but may equally also be taken as a point of departure for the idea that migrants process impressions which exposure offers – reflecting on, or even discussing, aspects which they find striking or of interest in some way. Therefore, migrants are in a unique position to develop comparative, evaluating, interpretative frames, which not only understand and relate to two contexts, and their underlying system dynamics and preconditions, but which can contrast them against each other.

In other words, and following Portes and Zhou (Citation1993), migrants’ interpretative frames are impacted by interaction with the society of settlement, but conversely, they are also impacted by sustained interaction with the society of origin. How a migrant’s views might change over time, may be the result of a number of intervening factors that mutually affect each other: type, volume, and depth of interpersonal interactions in the society of settlement, in the society of origin, with co-migrants in the society of settlement, with non-migrants in the society of settlement, as well as reflecting both the general level and direction of societal change ‘here’ and ‘there’, and finally, a migrant’s own demographic characteristics (gender, age, life-cycle stage, and length of stay abroad, among others).

We acknowledge the composite nature of the processes underlying change in people’s views. Here, we are concerned with the ways in which interpretative frames function: how do migrants compare and contrast realities ‘here’ and ‘there’, and negotiate different realities, in sense-making about their political views on particular issues? As we have shown above, despite longstanding research into social and political remittances, the literature is conspicuously silent about the processes of content creation. Here, the building bloc of ‘interpretative frames’ is particularly promising.

Building on existing work, with a model of content creation for political remittances consisting of (Levitt Citation1998; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011) – content creation, transmission, impact, we aim to unpack the ‘content creation’ step, by focusing on the work which migrants’ interpretative frames do, as they comparatively evaluate the contexts they are familiar with. Here, we propose to disaggregate the step of content creation, into exposure, comparative evaluation, and articulation (see ). Exposure, we argue virtually all migrants would experience. Comparative evaluation might be more or less implicit or explicit, conscious or not, and the extent of engagement in reflection processes will vary among migrants. Articulation is based on the insights which comparative evaluation yields and might pertain to one or both of the contexts’ migrants relate to, and refers to actively articulating these.

Both production processes are presented in in a simplified and stylised manner which renders their appearance more unidirectional than the bi- or multi-directional exchanges often empirically found. Nevertheless, building on this more fine-grained understanding of content creation, we recognise the role of motivation or intent in relation to transmission. But we also acknowledge that both intended and unintended circulation of ideas may contribute to change. Thus, we argue that motivation is a possible, but not always necessary step in the process of production of political remittances. For the purposes of our analysis, we focus on exposure and comparative evaluation as key to understanding the content creation for potential political remittances.

Methods and data

This article builds on a dataset of 80 semi-structured interviews with migrants from Poland and Romania, living in Barcelona and Oslo, twenty in each sub-group, respectively. The data was collected as part of a research project on emigration and political change in origin contexts in Central and East Europe. We selected Polish and Romanian emigrants, because these are numerically the two largest emigrant groups from this region to other parts of Europe (see e.g. Vlase Citation2013a; Vlase Citation2013b). Furthermore, in Norway, immigrants from Poland are the by far most numerous migrant group, whereas in Spain, Romanians are the most numerous EU-migrant group. Both Polish and Romanian migrants are also present in what are nationally (and by city) relevant numbers. The cities of Barcelona (Spain) and Oslo (Norway) were selected to have two distinct settlement contexts, including different political cultures and histories, different welfare regimes, different work culture, and different demographic composition of their migrant populations – while both large cities in their own national contexts.

The interviewees were recruited using a diverse set of entry-points, including the extended networks of the researchers, social media, migrant associations and religious institutions catering to migrants, as well as limited use of snowballing from one interviewee to another. The interviews were conducted in Polish and Romanian respectively, and then translated and transcribed in English. The full dataset has been extensively coded and analysed using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo 12, with a collaborative approach to developing a shared codebook.

The interviewees all gave their voluntary and informed consent to participate in the research project, and research ethics were a central concern throughout the data collection, analysis and writing. Therefore, interviewees are presented with a pseudonym in this text, with additional demographic information and characteristics of their engagement with their countries of origin, in an online Appendix.

The interviews typically lasted 1 to 1.5 hours, though some were briefer and a few longer. We followed a thematic interview guide, with seven substantive sections: Migration story; Future and past – lifespan reflections; Poland/Romania – engaging diasporas politically (voting and beyond); Reflecting on the most recent elections (Poland: Presidential 2019; Romania: Presidential 2019); Perceptions about other migrants from Poland in Barcelona/Oslo and from Romania in Barcelona/Oslo (respectively); Perceptions of differences and similarities between Poland and Norway or Spain, or between Romania and Norway or Spain; Migration and change (see online Appendix).

We draw on the complete dataset but focus especially on the last two sections of the coded interview material. For the theme: Perceptions of differences and similarities (…) we utilised a prompt in the interviews, where interviewees were presented a sheet with the keywords: Democracy, Corruption, Freedom of Speech, Religion, Rights of sexual minorities, Welfare, Gender equality, Immigration, Work conditions and opportunities, Environmental protection, Family obligations, Security. Interviewees were then asked to: discuss similarities and differences between the two contexts in relation to (some) of these key words, and to evaluate the degree of difference/similarity; reflect on reasons for difference/similarity; and comment on their own preferences, or thoughts about what was good or bad. Our aim was to allow interlocutors to express their views and impressions of differences and similarities, comparatively evaluating their experiences in these countries, based on their own subjective impressions, thus mobilising their interpretative frames.

Comparative evaluation: producing content for political remittances

Our analysis focuses on the process of producing content for potential political remittances, and the role of migrants’ interpretative frames therein. We analyse our interviewees’ reflections on three select themes, where they mobilised comparative evaluation and where their interpretative frames, shaped by multifaceted experiences evidently mattered. These were three of the twelve themes we used in the key-word-prompt-sheet during the interviews. Thus, we are not making any particular claims about why these themes were discussed. Instead, we our analysis is using statements about these three themes as a means to interrogate the content-creation step of the production of potential political remittances. The three themes in question are: corruption, public institutions, and democracy. Through this analysis, we address our main question: How does the content of potential political remittances actually come into existence?

Corruption

When I talk to my friends who are more integrated here, they tell me that [corruption] is the same as in Romania, but at the same time I have doubts about this. […] When you are here and you get hit by corruption here, it seems to you here it is corruption like there, but in reality, things are probably very different. That is, the phenomena are similar, but the magnitude is different.Footnote1

Taking Marius’s reflection on corruption as a point of departure, we find his interpretative frame as a migrant actively relates to ‘here’ and ‘there’. Marius, who is 44 and has been living in Barcelona since 2016 highlights the role of his exposure to the Spanish political scene: he is politically active, having voted in Romanian national elections before and after migration, while regularly discussing political issues affecting Romania and Spain with friends and families both in Barcelona and in Romania. However, he still refers to his friends ‘who are more integrated here’ [Barcelona], while questioning their assessment: this provides a reminder that exposure varies qualitatively, not just quantitatively with time, and that exposure to problems and discussions informs the development of the interpretive frame, leading to a potential evolution or re-establishment of political opinions. Echoing Marius, we find that our Romanian migrant interviewees in both cities tend to acknowledge that corruption exists everywhere, but that its magnitude and nature vary, though the situation in Romania is described in particularly negative terms, due to the permeation of corruption in most aspects of everyday life, as Maria (42) states:

I think it’s a different corruption. In our country [Romania] there’s this petty corruption, in hospitals, bribes, policemen and so on, whereas here this doesn’t exist, or almost doesn’t exist. It’s a system that works, but there’s corruption at a high level.

As Maria, who has been living in Barcelona for almost two decades, points out, the difference in visibility and extent between low-level and high-level corruption is often mentioned when comparing Romania and Spain. More nuance is provided by some of our Polish interviewees, among whom some argue that Spain does ‘worse’ than Poland, as in the case of Eliasz (39, in Barcelona since 2008) who says: ‘I don't know what corruption is like in Poland, but it is hard to be worse than Spain in this matter’. Other Poles pointed out that in Spain the issue is more visible and talked about, while in Poland it is conveniently kept quiet by political authorities.

When it comes to corruption, analysing migrants’ comparative evaluations reveals that, despite some clear difference between reflections depending on country of destination, the comparative evaluations across origin and settlement contexts are rather diverging at the individual level: Maria, Eliasz, and Marius have all been active politically before and after settling in Barcelona, and all of them have stated that they maintain political conversations with family and friends ‘here’ and ‘there’: yet they display different perceptions and opinions on the matter of corruption. Comparative evaluation of how corruption is perceived (or even experienced) across contexts mobilises reflections about what is relatively better or worse ‘here’ and ‘there’, which in turn may translate into ideas for change for the better. However, we find very few statements which point toward migrants seeing clear ‘lessons learned’ or ‘best practices’ when it comes to corruption. This might be linked to the fact that across the dataset, there is no unanimous sense that the problems of corruption are fully and adequately solved in any of the contexts. Rather, the reflection appears to be that there are profound similarities, yet different cultural and institutional iterations. We find heterogeneity among the interviewees in their comparative analyses of corruption ‘here’ and ‘there’, and we see non-linearity in how migrant origin and exposure to the same settlement context yield diverging assessments and comparative evaluations.

Public institutions

Considering perceptions of public institutions allows analysis of some issues which connect with corruption, most notably the question of trust in public institutions and the efficiency of public governance. Overall, when it comes to welfare, as something which public institutions are responsible for, most of our interviewees, Romanians and Poles in both Barcelona and Oslo, considered the provision of welfare and public services to be better in Spain and Norway than in Romania and Poland. The arguments made were also relatively similar: Norway and Spain were perceived to grant better access to public health care and to provide more generous unemployment benefits and low-income support than Romania and Poland. The system was perceived to work for the good of the residents overall, by contrast to the situation in Romania, as Crina (49) and Alessia (33) reflect on:

There is a lot of insecurity from the Romanian government. You could actually expect to hear them say ‘we are sorry but starting next month there is no money left for pensions fund […] Well that would never happen here [in Oslo], they never leave people when they are in need even if they have to take loans.

You have to think how your taxes are being used. I think that was one of my biggest disappointments back in Romania, looking at my taxes, which everyone has to pay and I’m ok with that, but I would like them to be more productive.

Crina and Alessia have both been living in Oslo since the early 2010s. While Alessia has voted in Romanian elections before and after migrating to Norway, Crina only started to vote after she moved to Oslo. Alessia regularly discusses political topics with friends and family in Norway and Romania, while Crina never does, keeping political opinions private. As exemplified by the quotes, exposure to the Spanish and Norwegian realities appears to impact migrants’ perception of the situation in the origin context, thus evidencing how interpretative frames, which are in simultaneous engagement over time with two contexts, produce comparative evaluations. This is the case also if these are not linked explicitly with statements about or commitment to acting on these insights drawn from the comparative evaluations.

Similarly, Denisa (53, in Barcelona since 2005) offers not only a description but also an analysis of medical services, based on the comparative evaluation which her own personal preferences as a migrant prompts:

I prefer to go to the doctor [in Spain] not because they have better doctors than in Romania, but because they are doing their job better because they are more motivated. In Romania doctors aren’t paid as they should be

Zaharia (32, in Oslo since 2008) notes ‘how overworked they are in the medical field and [how] public money is wasted in Romania’. Similar arguments about doctors and health professionals as relatively ‘better’ in Spain and Norway, not because they are better prepared or more educated than health professionals and doctors in Poland and Romania, but because they are better paid, more motivated, work in better-organised institutions and hence more efficiently, were made across our dataset, including among Polish respondents.

This reflects a perception that state and public institutions are perceived to be working for the public to a greater extent or more efficiently in Norway and Spain than in Poland and Romana. Zofia (35, in Oslo since 2013) explains, referring to the difficult conditions created by the COVID-19 pandemic:

In this whole difficult and stressful situation, I am for example at home for the 4th week, I practically don’t leave the house, […] I don’t know if my business will survive, but I know that I will have something to eat, because Norway will take care of me. […] The social policies are very fair, that they really want to help you. Whereas in Poland there are often political games, in my opinion.

The comparison with welfare provision in Poland foregrounds a perception that this is driven by political agendas, not as institutionalised support for all residents in an equal and transparent manner. As with the above example of healthcare, comparative evaluations point toward differences in institutional qualities, where migrants express preference for what they interpret as the settlement contexts models.

Drawing on reflections and comparisons around public institutions and the data at large, we find much comparative evaluation, but relatively little concrete articulation of paths toward change which might emanate from insights which comparative evaluation yields.

Democracy

When discussing democracy, we see a divide in our data between Oslo and Barcelona: in Oslo, none of our interviewees perceive democracy to function better in Poland or Romania than in Norway, while the answers given by our interviewees in Barcelona are considerably more mixed. We find that our Romanian and Polish interviewees in Oslo are more similar to each other in their views on democracy, than they are to their compatriots in Barcelona. Comparing Norway with their origin contexts, migrants point to transparency, the tone of political debates, and overall political awareness among people as the features that differentiate Norway for the better. Poland and Romania are, by contrast, often seen through a critical lens, as concerns are expressed about the rule of law and the aggression permeating political debates, as Maja (53) states:

I think the situation in Poland currently is difficult, and really against what I believe is freedom – it’s against freedom of speech and democracy. This couldn’t happen in Norway.

She also explicitly reflects on the conditions for democracy, comparing the national broadcaster’s political roles in Norway and Poland:

The public channel in Norway talks more about different things, and in Poland it talks about one thing. It’s used as a political tool. It scares people. When you listen to it, you’re shocked that this is happening in Poland, the scare. The horde of foreigners attacking our country …

Maja’s comparative evaluation of democracy draws on her exposure in both Poland and Norway: she has been living in Oslo since the mid-2010s and she has been voting from abroad with the same frequency as she did before leaving Poland, while regularly discussing political issues with friends and family in the two countries. It is very clear that Maja’s assessment of the situation, also comparatively, is shaped by her political preferences where the Polish context appears as a point of reference: what happens in Poland, in her view, would not happen in Norway. This offers a pointed diagnosis, and one with some engagement, yet (for now) far removed from any clear articulation of paths toward change, leading to a (potential) impact in Poland.

Dominika (65) presents a contrasting view when comparing the Spanish and the Polish contexts. Interestingly, she has been living in Barcelona for over 40 years, during which she has become accustomed to Spanish politics and has adopted a strong pro-Catalan independence stance. In her dislike for the central Spanish state, she positions herself on the side, as it were, of the current Polish government vis-à-vis debates on free speech and democracy in Europe today:

I think in Spain freedom of speech doesn't function well. There is freedom of speech, but it has to be according to the norms presented by the European Union. That means that I have the freedom of speech so I can speak well about migrants, Islam, but I don't have that freedom of speech if I wanted to glorify Christians. That's what I think. Some people are supported while others are stigmatized. That's the European Union’s direction. That's why Poland isn't popular in EU, because it goes in a different direction. It's a bastion which doesn't allow Islamic migration or building mosques. So, there is freedom of speech but only according to guidelines of the EU. I can't really say what I want or what I like.

Her comparative evaluation not only brings to the fore the EU as a supranational actor also affecting migrants’ views and assessments, but signals the profound ways in which political preferences shape migrants’ outlook too, potentially completely eclipsing the role of exposure in triggering reflections due to new practices or modes of thinking.

In Barcelona, aspects of democracy in the city specifically, are regarded positively, such as participation in demonstrations, electoral turnout, activism, the everyday dimension of activism outside and beyond electoral campaigns, as described by Agnieszka (38):

Democracy is something I feel every day, from the perspective of living in Barcelona. It is not just going to vote once in a while. So, this is the biggest difference in this matter. And living in Barcelona where the city is governed by the activists, it shows that you can become a mayor coming from ‘the street’. Most people don't have such ambitions and I don't either. But it is the feeling that the mayor is not a distant man in a suit. I feel the participation in democracy is completely different.

As Agnieszka’s statement shows, the specific context where comparative evaluations are situated really matters, and here scale plays an important role also. Agnieszka displays a high level of political awareness, having regularly voted for Polish elections before and after migration, and regularly discussing political issues with her personal networks in Poland and Spain. Meanwhile, as Bogdan (36), who has been living in Barcelona ever since turning 18, expresses, there is a substantial degree of frustration with the political system and how democracy functions in Romania (and Poland):

Here we try to win [elections] by doing better. But there, we are trying to win the elections by humiliation. This is the big difference between us on the political issue.

Comparing Poland and Norway, Lena (41, in Oslo since 2015) reflects about what she perceives to be a difference in attitude, which echoes the sentiment in Bogdan’s statement, about the nature and quality of democracy:

I don't know if you heard, but in Norway you wish each other “good elections” before voting. And that's a kind of … It's a celebration of democracy, how you wish Merry Christmas, you wish happy elections. And maybe this kind of attitude, if the authorities made this a holiday …

As with Agnieszka, both Lena and Bogdan have been actively participating in electoral contests before and after migration, and regularly discuss about politics with their personal networks ‘here’ and ‘there’. Migrants’ comparative evaluations on democracy, situated in Oslo/Norway or Barcelona/Spain and with an eye to Poland or Romania, underscore the salience of which contexts are being compared, for what might emerge in terms of political remittances content. With democracy, the high level of friction in national politics, especially in Poland, but also in Romania, and in the Spanish context too, means there is a degree of politicisation of views about democracy itself.

Unpacking the process of content creation of political remittances here faces the challenge of understanding the dynamics of pre-migration and post-migration socialisation and re-socialisation processes, as well as of accounting for interviewees’ political preferences – and how these may change with migration experiences – in the two different contexts.

Comparative evaluation and content creation

Based on our data, we suggest first, that both socialisation prior to migration and re-socialisation in the new context are ongoing, albeit to differing degrees; second, that political preferences may well cut across such socialisation or re-socialisation dynamics; and third, that migrants may apply different logics to how they interpret the two contexts they relate to. This means that non-linearity in migrants views and opinions, whether these are views emanating from comparative evaluation of context of origin and settlement, or the absence of such comparative evaluation, are to be expected. Importantly, it is also worth noting that, as emerged from our dataset, while migrants may have formed opinions on which political systems, solutions, or models they prefer or think of as ideal, there is little articulation about the transferability of such solutions from one context to another, or of how one country should learn from the other, in relation to a given issue. However, our insights merit further investigation with comparative survey data across cities and contexts, to systematically account for these (and other) mechanisms at play in the production of content for (potential) political remittances.

While in our interviews we asked migrants about similarities and differences, thus prompting comparative evaluations, the level of reflection and the breadth of examples which our interviewees shared, suggests that these comparative evaluations are indeed natural elements of migrants’ everyday lives, exposed somehow to two contexts simultaneously. We thus find that comparative evaluations are indeed ongoing: however, this does not necessarily mean that such comparative evaluations of how things work ‘here’ and ‘there’ lead to reflections on the potential for change in one or both of the contexts migrants relate to. This cuts across age, how long people have been living abroad, and whether they discuss political matters with their families and friends in the two contexts. Thus, content creation in the process of the formation of political remittances must be further disentangled, in order to allow exposure, followed by comparative evaluation, to come into plain view, as two connected but distinct steps, both of which we find most of our interviewees matter-of-factedly engaging in.

These precede the articulation of any concrete paths toward change. Such paths include what a very small minority of our interviewees did explicitly share views about: for instance, Mikołaj (37, who has been living in Oslo for 13 years) suggested that Poland has a great deal to learn from Norway when it comes to social policy. However, Mikołaj displayed a low level of political engagement, as he has never voted since migrating to Norway and only voted occasionally prior to migration. In addition, he keeps political matters private, as he does not have such discussions with friends or family neither ‘here’ nor ‘there’: therefore, his wish for Poland to learn from Norway on the matter of social issues is not concretised or transferred back to Poland either by voting or discussing. Similarly, Sebastian (35, who has been living on and off in Barcelona since the mid-2000s) noted that Spain could be an example worth following for dealing with corruption in Poland. However, since moving abroad he has not been voting regularly in Polish elections and only rarely does he discuss political matters with family and friends in Poland. He also tends not to discuss Polish political issues with his networks in Barcelona, rather preferring to discuss political issues affecting Barcelona and Spain instead.

Conclusion

Travel certainly broadens the mind, or to put it more rigorously, as illustrated through our analytical framework, migrants’ perspectives – or interpretative frames – are impacted by migration. With these changed interpretative frames, migrants engage in a process whereby they compare the various contexts that they are exposed to. In previous literature, the study of migrants’ impact on their countries of origins has been analysed through the concept of ‘political remittances’ as a subset of ‘social remittances’, and the process has been explained in stages: content creation, transmission, and impact. In this article, we set out to explore how migrants’ interpretative frames are impacted from exposure to multiple contexts and how the ensuing processes of comparative evaluation of their political environments could result in the creation of content for potential political remittances. This study’s original contribution lies in its specific focus on the first stage of the production of social and political remittance: content creation.

As shown above, we find that the process of production of potential political remittances involves, firstly, exposure to a new environment, and, secondly, comparative evaluation, which both appear to be relatively common among migrants, and simultaneously should be seen as necessary but not sufficient conditions for the formation of political remittances.

Through the lens of three specific themes – corruption, public institutions, and democracy – we were able to learn about how migrants comparatively evaluate the political contexts of ‘here’ and ‘there’, which we argue is the first step in creating content which can become political remittances. It is worth underscoring the non-linearity and inconsistency we find in interviewees’ comparative evaluations across different themes (see also online Appendix). It was more common than not that there was greater diversity among Poles and Romanians respectively, than necessarily difference between the two migrant groups, in Barcelona and Oslo overall. More significantly, there was a relatively high level of what might be described as internal inconsistency in interviewees’ statements and views across specific themes we asked them about. It is thus not given that more conservative or more liberal views on a given issue are a sound predictor of the type of views on any other single issue. Such human inconsistency is not necessarily surprising, but it challenges the assumption of the democratising (or liberal) nature of political remittances from migrants living in consolidated, liberal democracies (Kessler and Rother Citation2016; Rother Citation2009).

The non-linearity of migrants’ views reflects the complexity of their life journeys: socialisation and re-socialisation before and after migration; the socio-political contexts they relate to simultaneously; the networks they are part of and their personal life experiences. This contextualises the question not only of the formationof political remittances, but also of potential further downstream steps. As illustrated in ., we argue that the process of production of political remittances consists of content creation which can be disaggregated into: exposure – comparative evaluation – articulation. Furthermore, we know that transmission (or circulation) as well as ‘reception’ precede impact (see also Levitt Citation1998; Levitt and Lamba-Nieves Citation2011; Grabowska et al. Citation2017). Somewhere between comparative evaluation, articulation and transmission, desire or intent is likely to be found in some cases, while not in others – and in turn migration can clearly contribute to processes of change, whether or not this is migrants’ explicit desire or intent (see also de Haas Citation2010; Garapich Citation2016a; Citation2016b).

Overall, we found little articulation of clearly imagined paths to change emanating from insights on comparative evaluations in our data, thus raising questions about the much referred to idea of ‘migrants as agents of change’. Our data strongly suggests that when migration leads to exposure to new ideas and practices, which is a highly agreed upon axiom in the migration field, it is likely that this prompts comparative evaluation. But it remains an empirical question how and to what extent this is connected with migrants’ desire or lack of desire to engage in processes of change in the context of origin, and relatedly, also for any intended or unintended impact which migration may have at different scales and in diverse spheres of a given origin context. These are areas which it would be very interesting for future studies to contribute further knowledge about.

Whereas much of the literature imagines migrant agency as conscious activism or entrepreneurship, it should also be noted that mere content creation can generate ideas about a desired political landscape which transmitted via social channels (conversations or visits in the country of origin) can circulate among non-migrants, only to be picked up and articulated by domestic activists, or used as a benchmark to evaluate country of origin realities. This implies that content created through the process of critical comparison by migrants can be unintentionally transmitted and also have an impact on the interpretative frames of those who receive the content, sparking a different format of political or social remittances than what we may be used to considering. This is another area where there appears to be much scope for further research.

We do not in our dataset find much strong expression of desire among migrants to act as agents of change, but there are some threads emerging from the data which suggest why migrants possibly might not desire to engage intentionally in transmitting political remittances. These include: not having faith in the possibility of political change or not having interest in taking on the role, personally, of an agent of change. The fields of social and political remittance could benefit from research which further explores the reasons that migrants may choose not to engage. Meanwhile, given the emphasis in extant literature on transmission and impact of (social and) political remittances, these aspects are more addressed. Therefore, what we propose here are sketches for further exploration, mainly to the end of better understanding the process of production of political remittances.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (283.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All names are pseudonyms.

References

- Ahmadov, A. K., and G. Sasse. 2016a. “Empowering to Engage with the Homeland: Do Migration Experience and Environment Foster Political Remittances?” Comparative Migration Studies 4 (1): 12, Article 4.

- Ahmadov, A. K., and G. Sasse. 2016b. “A Voice Despite Exit: The Role of Assimilation, Emigrant Networks, and Destination in Emigrants’ Transnational Political Engagement.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (1): 78–114.

- Anghel, R. G., M. Fauser, and P. Boccagni. 2019. Transnational Return and Social Change: Hierarchies, Identities and Ideas. London: Anthem Press.

- Batista, C., J. Seither, and P. C. Vicente. 2019. “Do Migrant Social Networks Shape Political Attitudes and Behavior at Home?” World Development 117: 328–343.

- Batista, C., and P. C. Vicente. 2011. “Do Migrants Improve Governance at Home? Evidence from a Voting Experiment.” The World Bank Economic Review 25 (1): 77–104.

- Bauböck, R. 2003. “Towards a Political Theory of Migrant Transnationalism.” International Migration Review 37 (3): 700–723.

- Boccagni, P., and F. Decimo. 2013. “Editorial: Mapping Social Remittances.” Migration Letters 10 (1): 1–10.

- Boccagni, P., J. M. Lafleur, and P. Levitt. 2016. “Transnational Politics as Cultural Circulation: Toward a Conceptual Understanding of Migrant Political Participation on the Move.” Mobilities 11 (3): 444–463.

- Chaudhary, A. R. 2018. “Voting Here and There: Political Integration and Transnational Political Engagement among Immigrants in Europe.” Global Networks 18 (3): 437–460.

- de Haas, H. 2010. “The Internal Dynamics of Migration Processes: A Theoretical Inquiry.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (10): 1587–1617.

- Fitzgerald, D. 2004. “Beyond ‘Transnationalism’: Mexican Hometown Politics at an American Labour Union.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 27 (2): 228–247.

- Fomina, J. 2021. “Voice, Exit and Voice Again: Democratic Remittances by Recent Russian Emigrants to the EU.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (11): 2439–2458.

- Garapich, M. P. 2016a. “Breaking Borders, Changing Structures – Transnationalism of Migrants from Poland as Anti-State Resistance.” Social Identities 22 (1): 95–111.

- Garapich, M. P. 2016b. “I Don’t Want this Town to Change’: Resistance, Bifocality and the Infra-Politics of Social Remittances.” Central and Eastern European Migration Review 5 (2): 155–166.

- Grabowska, I., and M. P. Garapich. 2016. “Social Remittances and Intra-EU Mobility: Non-Financial Transfers Between UK and Poland.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 42 (13): 2146–2162.

- Grabowska, I., M. Garapich, E. Jazwinska, and A. Radziwinowiczówna. 2017. Migrants as Agents of Change. Social Remittances in an Enlarged European Union. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hartnett, L. A. 2020. “Relief and Revolution: Russian émigrés’ Political Remittances and the Building of Political Transnationalism.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1040–1056.

- Horst, C. 2018. “Making a Difference in Mogadishu? Experiences of Multi-Sited Embeddedness among Diaspora Youth.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (8): 1341–1356.

- Itzigsohn, J., and D. Villacres. 2008. “Migrant Political Transnationalism and the Practice of Democracy: Dominican External Voting Rights and Salvadoran Hometown Associations.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 31 (4): 664–686.

- Kessler, C., and S. Rother. 2016. Democratization Through Migration? Political Remittances and Participation of Philippine Return Migrants. Lexington Books.

- Krawatzek, F., and L. Müller-Funk. 2020. “Two Centuries of Flows Between ‘Here’ and ‘There’: Political Remittances and Their Transformative Potential.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 46 (6): 1003–1024.

- Lacroix, T., P. Levitt, and I. Vari-Lavoisier. 2016. “Social Remittances and the Changing Transnational Political Landscape.” Comparative Migration Studies 4 (1): 1–5.

- Levitt, P. 1998. “Social Remittances: Migration Driven Local-Level Forms of Cultural Diffusion.” International Migration Review 32 (4): 926–948. doi:10.2307/2547666.

- Levitt, P., and D. Lamba-Nieves. 2011. “Social Remittances Revisited.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 37 (1): 1–22.

- Levitt, P., and D. Lamba-Nieves. 2013. “Rethinking Social Remittances and the Migration-Development Nexus from the Perspective of Time.” Migration Letters 10 (1): 11–22.

- McGinnity, F., and M. Gijsberts. 2016. “A Threat in the Air? Perceptions of Group Discrimination in the First Years After Migration: Comparing Polish Migrants in Germany, the Netherlands, the UK and Ireland.” Ethnicities 16 (2): 290–315.

- Nowicka, M., and V. Šerbedžija. Eds. 2017. Migration and Social Remittances in a Global Europe. Springer.

- Nyblade, B., and A. O’Mahony. 2014. “Migrants’ Remittances and Home Country Elections: Cross-National and Subnational Evidence.” Studies in Comparative International Development 49 (1): 44–66.

- Ostergaard-Nielsen, E. 2003a. “The Politics of Migrants’ Transnational Political Practices.” International Migration Review 37 (3): 760–786.

- Ostergaard-Nielsen, E. 2003b. Transnational Politics: The Case of Turks and Kurds in Germany. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Paasche, E. 2017. “A Conceptual and Empirical Critique of ‘Social Remittances’: Iraqi Kurdish Migrants Narrate Resistance.” In Migration and Social Remittances in a Global Europe, edited by M. Nowicka and V. Šerbedžija, 121–141. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pérez-Armendáriz, C., and D. Crow. 2010. “Do Migrants Remit Democracy? International Migration, Political Beliefs, and Behavior in Mexico.” Comparative Political Studies 43 (1): 119–148.

- Piper, N. 2009. “Temporary Migration and Political Remittances: The Role of Organisational Networks in the Transnationalisation of Human Rights.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 8 (2): 215–243.

- Portes, A. 2010. “Migration and Social Change: Some Conceptual Reflections.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36 (10): 1537–1563.

- Portes, A., and M. Zhou. 1993. “The new Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and its Variants.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 530 (1): 74–96.

- Rother, S. 2009. “Changed in Migration? Philippine Return Migrants and (Un)Democratic Remittances.” European Journal of East Asian Studies 8 (2): 245–274.

- Smith, M. P., and M. Bakker. 2005. “The Transnational Politics of the Tomato King.” Global Networks 5 (2): 129–146.

- Tabar, P. 2014. “Political Remittances’: The Case of Lebanese Expatriates Voting in National Elections.” Journal of Intercultural Studies 35 (4): 442–460.

- Vélez-Torres, I., and J. Agergaard. 2014. “Political Remittances, Connectivity, and the Trans-Local Politics of Place: An Alternative Approach to the Dominant Narratives on ‘Displacement’in Colombia.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 53: 116–125.

- Vlase, I. 2013a. “My Husband is a Patriot!’: Gender and Romanian Family Return Migration from Italy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (5): 741–758.

- Vlase, I. 2013b. “Women’s Social Remittances and Their Implications at Household Level: A Case Study of Romanian Migration to Italy.” Migration Letters 10 (1): 81–90.

- White, A., and I. Grabowska. 2019. “Social Remittances and Social Change in Central and Eastern Europe: Embedding Migration in the Study of Society.” Central and Eastern European Migration Review 8 (1): 33–50.

- White, A., I. Grabowska, P. Kaczmarczyk, and K. Slany. 2018. The Impact of Migration on Poland: Eu mobility and Social Change. UCL Press.

- White, S., N. Nevitte, A. Blais, E. Gidengil, and P. Fournier. 2008. “The Political Resocialization of Immigrants: Resistance or Lifelong Learning?” Political Research Quarterly 61 (2): 268–281.