ABSTRACT

Far fewer people migrate than global disparities in wealth and well-being would lead us to predict, yet we know relatively little about why those who presumably have much to gain from migration prefer to stay in place. This article examines the motivations of young people who express the preference to stay put, and asks what individual and household characteristics are associated with voluntary immobility. Using survey data collected in Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam for the Young Lives Project, we find that the majority of young people surveyed envision a future within their home country, and between 32 per cent (Ethiopia) and 60 per cent (Vietnam) prefer to stay in their current location. Most youth prefer to stay for family-related reasons. Living in an urban area and engagement in farm work are associated with greater staying aspirations, but only for youth from the most resource-poor or the wealthiest households. Higher levels of schooling, wealth, feelings of self-efficacy and paid employment are consistently associated with diminished desires to stay, with stronger effects for youth from rural settings, resource-poor households, and women. Our results reveal the social patterning of staying aspirations and have important implications for development interventions that seek to enhance aspirations and capabilities of individuals to stay in place.

Introduction

It is now well established that youth, those between the ages of 15 and 30, are the most likely to aspire to migrate and to realise their migration intentions (Bogue Citation1959; De Jong and Fawcett Citation1981; Esipova, Ray and Pugliese Citation2011). Research provides many explanations for why, as people age, they become less likely to aspire to migrate or to realise their migration plans. For example, as people marry and have children, the material and immaterial costs of migration rise (Ritchey Citation1976; Haug Citation2008). Social and economic ties as well as feelings of ‘place-attachment’ also tend to strengthen over the life cycle (Fischer and Malmberg Citation2001; Lewicka Citation2011). However, research provides far fewer explanations and insights into why many young people, and especially those who presumably have good reasons to migrate, do not wish to do so.

In this article, we focus on the preference to stay, and therefore the determinants of ‘potential immobility,’ to complement growing research on migration aspirations and ‘potential mobility’ (see Esipova, Ray and Pugliese Citation2011; Docquier, Peri and Ruyssen Citation2014; Carling and Collins Citation2018). Our focus on immobility is partly a corrective to the mobility bias in migration studies, that is, a tendency to focus theoretical and empirical attention on the drivers of migration – the forces and conditions that initiate and perpetuate movement – rather than the personal and structural forces that resist or restrict migration (Schewel Citation2020). A mobility bias in migration research produces theories that tend to overestimate movement (Hammar and Tamas Citation1997), and ignores two important realities: many people who migration theories assume should aspire to migrate do not wish to do so, and many who do aspire to migrate may lack the capability to leave. As a result, far fewer people migrate than wide disparities in wealth and well-being worldwide would lead us to predict (see Massey et al Citation1999; Carling Citation2002; Schewel Citation2020).

Using survey data from Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam, this article asks: among the age cohort most prone to leave, who prefers to stay put? More specifically, what are the characteristics and motivations of youth who envision a future locally? We give attention to differences by gender, household wealth, and rural/urban location, recognising that the factors that motivate a desire to stay in place may differ for young women and men and for youth from different socioeconomic circumstances.

Our survey data comes from the Young Lives project, a study on the causes and consequences of childhood poverty in these case study countries (Boyden et al Citation2016). In line with the study’s overarching aims, poor areas in these countries were over-sampled, while children from better-off areas were included for comparison. This design provides an opportunity to focus on the aspirations of young people in resource-poor settings. Because the Young Lives data is not nationally-representative, our primary goal in this article is to discern initial patterns in how common development indicators at the individual and household level relate to staying aspirations across country contexts, rather than to explain country-level variations in staying aspirations. Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam are all majority rural societies with large agricultural sectors that have experienced notable gains in human and economic development since the 1990s. This provides an opportunity to explore the characteristics and motivations of young people who do not want to migrate in countries experiencing the social transformations associated with modern-day development.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 1 provides a brief theoretical and empirical background to the study, reviewing the concept of ‘voluntary immobility’ and the development contexts of Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam. Section 2 presents further details about the Young Lives dataset, its methodology, and the individual and household indicators we include in our analyses. Section 3 presents the main motivations young people give for not wanting to migrate, and Section 4 analyses what characteristics and life circumstances are associated with a preference to stay, with attention to differences by gender, wealth and rural/urban location.

Background

Conceptualising voluntary immobility

Long neglected by migration researchers, a mushrooming body of literature addressing immobility is shedding new light on why people do not migrate (see Schewel Citation2020, Gruber Citation2021). As is often the case in under-researched areas, initial research has focused on sketching the contours of the phenomena, offering simple typologies to clarify, as Mata-Codesal (Citation2015) put it, the ‘different ways of staying put.’ For example, in this journal Carling (Citation2002) first introduced the term ‘involuntary immobility’ to distinguish ‘voluntary non-migrants,’ ‘who stay because of a belief that non-migration is preferable to migration,’ from ‘involuntary non-migrants,’ ‘who aspire to migrate but lack the ability’ (Carling Citation2002, 12). That same year Cohen (Citation2002) identified three types of non-migrating households in rural Oaxaca, Mexico—the marginal, average and successful—to explain why some households ‘choose to ‘stay home’ while others cannot migrate.’ Examining immobility in rural Ecuador, Mata-Codesal (Citation2015) explored the distinction between ‘desired immobility’ and ‘involuntary immobility.’ Schewel (Citation2015) added the concept ‘acquiescent immobility,’ based on research in Senegal, to highlight a category of people who prefer to stay yet lack the ability to migrate and thus a meaningful choice. In a study of stayers in Brazil, Robins (Citation2022) uses the term ‘active immobility’ to emphasise staying as an actively chosen process, ‘a conscious decision rather than a passive result of a lack of agency’ (2). At the intersection of migration and environmental studies, the term ‘trapped populations’ is gaining traction to distinguish those who ‘are trapped in vulnerable locations’ from those who ‘choose to stay’ when facing environmental decline or natural disasters (Black et al. Citation2011, 123; Ayeb-Karlsson et al. Citation2018).

Although the vocabulary varies to describe these different forms of immobility, almost all revolve around a voluntary/involuntary distinction, or the degree to which a person chooses or is forced into staying in place. This distinction is helpful, not least because it complicates immobility, giving new dimensions to a category that has for too long been taken as ‘static, natural or residual’ (Gaibazzi Citation2015, 3). Yet, this distinction also introduces a host of other conceptual and empirical difficulties, many of which mirror the same challenges researchers face in distinguishing voluntary from forced migration. Across a wide variety of circumstances, the complex coexistence of volition and limited choice, of personal desires and external compulsions, of circumscribed opportunities and capability constraints—these human and social realities muddle the boundaries of our neat conceptual categories (see Erdal and Oepen Citation2018, Carling and Schewel Citation2018, Schewel Citation2021).

Beyond the voluntary or involuntary distinction, moreover, there are also many different ways of being voluntarily immobile. When people express a preference to stay, this preference could reflect a number of qualitatively different circumstances: an enthusiastic embrace of local opportunities, a commitment to staying in one’s community despite local decline, risk aversion, acceptance of one’s inability to migrate, or perhaps a person has never meaningfully considered leaving and thus never developed a real preference one way or another. These very different circumstances—from acquiescent to active immobility—could all fall under the umbrella of ‘voluntary immobility’.

Conscious of this diversity, and given the limitations of our survey data, what unites the voluntarily immobile in this study is simply the expressed preference not to move in the next ten years, which we describe as the ‘aspiration to stay.’ Clearly, we are using ‘aspiration to stay’ in a very broad sense, in the same way Carling and Schewel (Citation2018) use the term ‘migration aspiration’ to refer to the general conviction that migration is preferable to non-migration, thereby encompassing desires to migrate along a spectrum of forced to voluntary. The aspiration to stay – which we also refer to in terms of the desire, wish, or preference to stay (cf Carling and Schewel Citation2018) – similarly refers to the general conviction that staying is preferable to migration.

Country contexts

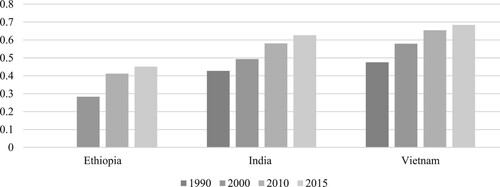

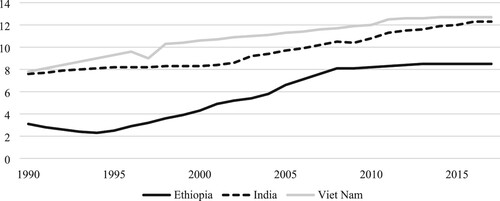

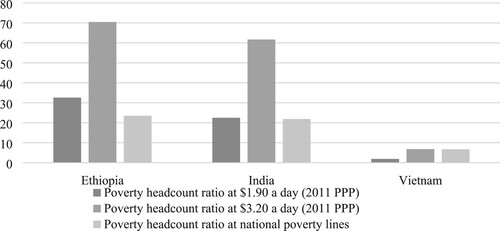

Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam all experienced notable gains in human and economic development indicators since the 1990s. Human development, measured by a composite picture of three dimensions of human development—life expectancy, education and gross national income—has risen at varying degrees for each country over the last few decades (see ). The most dramatic rise is seen in Ethiopia, in part because of the rapid expansion in primary education there (see Figure A.1 in the Appendix). Today, India and Vietnam are categorised as middle-income countries while Ethiopia is a low-income country – although poverty rates differ significantly between countries. As Figure A.2 shows in the Appendix, poverty headcount ratios in India are more similar to Ethiopia than to Vietnam, where poverty rates are much lower.

Figure 1. Human development index trends by country (1990-2015).

Source: UNDP Human Development Report 2019.

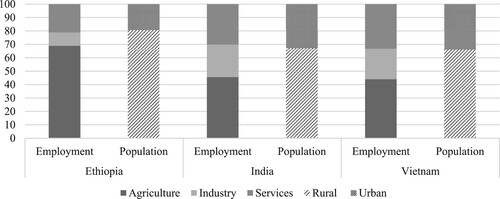

As these countries experienced the fundamental social transformations associated with economic growth and human development over the last several decades, population movements also shifted. Regarding internal migration, each country experienced a steady urbanisation process, driven by rural-urban migration in addition to natural urban population growth and urban expansion (WDI Citation2019). In each of the three countries, the vast majority of migration is internal migration between villages, towns, and cities. The percentage of each country’s population now living in urban areas mirrors the sectoral make-up of employment (see ), with Ethiopia remaining the most rural and agricultural of the three countries.

Emigration rates, defined here as total emigrant stock per total population, show steady but small growth over the last few decades: from 0.8% in 2000–1.2% in 2015 in India, and 2.3% to 2.8% over the same period in Vietnam (UN Citation2017). Middle Eastern countries and the United States are key destination areas for Indian emigrants. Vietnam has the greatest share of its emigrants in the United States – some half of all overseas Vietnamese – due to refugee flows and family reunification after the Vietnam War. Ethiopian emigration has largely been directed to the United States, the Middle East, and African destinations. Ethiopia shows the lowest levels of emigration, 0.7%, with little to no reported increase since 2000 (UN Citation2017), although research suggests a notable rise in irregular migration from Ethiopia over the last two decades, particularly to Middle Eastern countries (Zewdu Citation2018; Fernandez Citation2020; Schewel and Asmamaw Citation2021). Gavonel (Citation2017) finds a higher rate of attrition due to emigration for the Ethiopia Young Lives sample (5.2% versus less than 1% in Vietnam and India) – much of which was likely irregular labour migration to Gulf countries as minors. This rise in migration has not yet been captured in formal emigration estimates.

Against this backdrop of rising mobility associated with rising human and economic development, we ask: who are the young people who prefer to stay put? Research often emphasises that migrants are not a representative sample of origin communities. They tend to come from particular age, gender, or social groups – what researchers refer to as the ‘selectivity’ of migration (see, for example, Garip Citation2012). Yet, given the normalcy of internal and international mobility, this also means non-migrants are not a representative sample of any given community. Nor are non-migrants one homogenous social group. By focusing directly on the characteristics and motivations associated with the aspiration to stay, the following sections explore whether there is meaningful heterogeneity among these potential stayers.

Methodology

Data and sampling

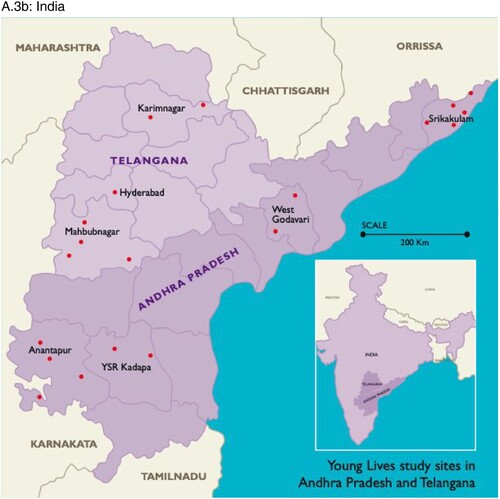

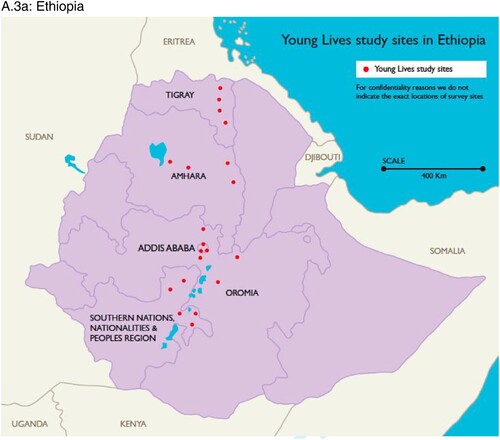

We use data from the Young Lives project, a longitudinal study on child and youth poverty, funded by the UK Department for International Development (DfID). This study collected panel data over a fifteen-year period in each country among a younger cohort (2,000 children born in 2001-02) and an older cohort (between 700 and 1,000 children born in 1994-95) in each country.Footnote1 We use data from the older cohort, who were roughly between 18 and 20 years old when interviewed for the fourth survey round in 2013 and 2014, the only round in which respondents were asked about their migration aspirations. Sample sites were selected in five major regions of Ethiopia (Amhara, Oromia, SNNPR, Tigray, and the capital city Addis Ababa), two states in India (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana), and five regions of Vietnam (the North-East region, Red River Delta, South Central Coast, Mekong River Delta, and the city of Da Nang). Figure A.3 contains maps of these fieldwork locations. The Young Lives methodology randomised households within each study site while the sites themselves were selected to illustrate diversity in terms of rural and urban locations, ethnicity and religion. In total, after deletion of missing values, our analyses are based on a sample of 2,547 individuals (885 in Ethiopia, 868 in India, and 794 in Vietnam).Footnote2

In line with the overall focus of the study on childhood poverty, districts with higher food shortages were oversampled to ensure the inclusion of children from poor households, and urban and rural areas were purposively sampled so that children from both areas were included (see Outes-Leon and Sanchez Citation2008; Kumra Citation2008; Nguyen Citation2008). Although this means that the data is not nationally representative, this sampling strategy is theoretically generative in the context of this study’s research interests. Many national-level datasets tend to underrepresent poor youth (Gavonel, Citation2017). The ‘pro-poor’ sampling design of the Young Lives study allows us to analyze how economic and educational factors impact aspirations to stay for young people in relatively resource-poor contexts. These are also the contexts most often targeted by development interventions aimed at alleviating what are commonly assumed to be root causes of migration: poverty, unemployment, and insecurity.

Variables and analyses

In this article, those who have ‘staying aspirations’ are those who answered ‘no’ to the question: ‘Would you like to move from your current location to a different place at some point within the next 10 years?’ The wording of the survey question suggests that what we refer to here as staying aspirations may reflect genuine desires to stay, not simply an acceptance of constraints. The wording of the Young Lives survey question, ‘Would you like to move … ’ is significantly different from ‘Will you move … ’ The former asks about desires; the latter requires some consideration of actual opportunities, constraints, and the likelihood of migration. Staying aspirations here, then, refer to young people who ideally prefer not to move in the next decade. Further, because those who answered yes to the question were then asked where they would be most likely to move, we are also able to differentiate between those who aspire to migrate internally rather than internationally.

Our analyses consist of descriptive statistics and regression analyses in which we include several individual and household characteristics to study how these are associated with the respondents’ preferences to stay. summarises the individual and household characteristics of the young respondents in our sample. Regarding individual characteristics, we include age, gender, and three education-related variables: whether or not respondents were in school at the time of survey, their educational attainment, and their aspired educational attainment. Aspired educational attainment is measured by asking youth what level of education they aspired to attain, imagining they had no constraints. The average score on this variable across the four countries is 5.21, which corresponds to an education level in-between post-secondary education and bachelor levels. The upper limit of actual educational attainment for this cohort of youth is upper secondary.

Table 1. Youth interviewed in Ethiopia, India, Peru, and Vietnam.

We also include a variable for self-efficacy, which generally refers to a person’s conviction in their ability to succeed (Bandura Citation1977). Personal and psychological characteristics are being given more attention in development analyses and strategies (see World Bank Citation2015), and self-efficacy is one personal characteristic, alongside others like risk-aversion (Czaika Citation2015; Lee Citation1966), that appears to have a close relationship with migration aspirations (Hoppe and Fujishiro Citation2015; Hagen-Zanker and Hennessey Citation2021).

To explore how local employment relates to aspirations to stay, we also incorporate variables that capture whether youth had engaged in farm work, paid employment and/or business activities over the 12 months previous to data collection.Footnote3 This indicator is particularly interesting to analyse in light of development aid strategies that aim to reduce migration through job creation (see Clemens and Postel Citation2018). Here we are able to examine how different kinds of employment relate to staying aspirations. Fourty-three per cent of youth in our sample had engaged in farm work, 38 per cent had been involved in paid employment, and 19 per cent were engaged in business activities.

We include a variable for previous migration episodes. Almost half of the respondents had moved prior to the Round 4 survey, with a higher share in Vietnam and India. Gavonel (Citation2017) provides an extensive overview of patterns and drivers of internal migration between Rounds 3 and 4 of Young Lives and finds that the main reason for moving in all countries is education-related, followed by family-related reasons (marriage, birth, or family reunification) in Ethiopia and India and work-related reasons in Vietnam. We find that those who did not move over this same period (between 2009 and 2013/14) were mostly young people from resource-poor households in rural areas and young people belonging to the higher wealth index categories in urban areas (see ).

Table 2. Individuals who did not move since 2009, by wealth index and rural/urban.

We include two wealth measures: a subjective measure of household wealth and a wealth index composed of three indices measuring housing quality, consumer durables, and access to services (see Outes-Leon and Sanchez Citation2008 for more information on the construction of the wealth index). Housing quality includes the number of rooms per person, floor quality of the house, and roof quality.Footnote4 The consumer durables index includes ownership of large household assets such as a radio, bicycle, TV, motorbike or scooter, motorised vehicle or truck, landline telephone, and a modern bed or table. Finally, the services index includes whether the household has access electricity, piped water source, a pit latrine or flush toilet, and if the household uses electricity, gas or kerosene for cooking. This composite wealth index aims to capture the long-term economic status of families, but one important limitation is that it does not include the incomes available to young people or a family in a given period. In the analyses, we split the wealth index into quintiles per country to study the prevalence of staying aspirations for youth in different wealth categories. Thus, these wealth categories represent a young person’s economic background relative to their respective country sample. We also add an indicator for household livestock ownership. Livestock can be a significant source of wealth, particularly (but not exclusively) in rural areas,Footnote5 but it was not captured in the wealth index.

Finally, we differentiate between rural and urban residence and also include two indicators that address the role of family and community as potential retain factors: the number of people that our respondents can rely on for material support and the number of relatives or family in the local community. Previous research suggests family and friends are a valued aspect of life that tends to reduce desires to leave (Ritchey Citation1976; de Jong and Fawcett Citation1981) and as the following section confirms, family-related reasons are overwhelmingly the most common explanation young people give for not wanting to migrate.

Findings

Motivations for staying

As the young people surveyed by the Young Lives study navigate a crucial period of transition into adulthood, the majority envision a future within their country, with a smaller subset imagining a future in their immediate community. As shows, 61 per cent of respondents in Ethiopia, 71 per cent in India, and 87 per cent in Vietnam do not want to leave their country. Among these potential stayers are those who do not want to leave their current locality: 32 per cent of respondents in Ethiopia, 36 per cent in India, and 60 percent in Vietnam.Footnote6 We focus our analyses on this latter cohort, those who prefer to stay in place.

The majority of the Young Lives respondents describe family-related reasons as their main motivation to stay (). This is particularly the case in Vietnam, where 69 per cent of respondents stated that family was their primary reason for staying. Other important motivations include having a good work, happiness and generally having a ‘good life.’ In India, approximately 20 per cent of young people mention property such as housing or land as the main reason to stay. This was far less common in Ethiopia or Vietnam, highlighting the importance of understanding local norms regarding land-holding and the age at which people generally inherit property. Enrolment in school is a more commonly cited reason for staying in Ethiopia than it is in India and Vietnam. Overall, respondents prioritised ‘retain factors’ over ‘repel factors’ (e.g. ‘migrants are not successful’) or migration constraints (e.g. ‘I cannot afford to move’) as reasons for staying.

Table 3. Main reasons to stay in current location.

examines the respondents’ motivations for staying split by wealth index quintiles, rural/urban location, and gender. While family-related motivations remain the most common explanation for staying aspirations across socioeconomic groups, they were notably higher among youth from the poorest households, youth in rural areas, and young women. Young people from wealthier households and youth in urban areas more often expressed being happy, having a good life, or enrolment in schooling as a reason for staying as compared to poorer youth or youth in rural areas. The most significant gender differences in motivations to stay concern work and family. Both sexes mention family and employment as key motivations for staying, but young men more often mentioned good local employment, whereas women more often mentioned the presence of family.

Table 4. Main reasons to stay in current location: by wealth index, rural/urban and gender.

Factors associated with voluntary immobility

examines what individual and household characteristics are associated with the aspiration to stay in one’s current location while controlling for other variables, including country-specific effects (descriptive statistics are included in the Appendix Table A.1). We add the variables in a step-wise fashion to check the robustness of results. Regarding formal education, we find that current enrolment in school, attaining upper secondary levels, and aspiring for higher levels of schooling are all strongly associated with lower staying aspirations (i.e. greater migration aspirations). Higher levels of self-efficacy are also associated with greater desires to migrate. Even when controlling for wealth and education levels, those who feel more control over their futures are more likely to want to leave.

Table 5. Regression analyses: aspirations to stay in current location.

Regarding wealth and employment, we find that engaging in household farm work is positively associated with aspirations to stay in one’s locality, while access to paid employment decreases the desire to stay. Higher levels of wealth, as measured by the wealth index and subjective wealth, appear to be negatively related to aspirations to stay (Model 3), but the significance of the effects of the wealth indicators diminishes in the final model. This is mostly due to the inclusion of the education variables, which are correlated with the wealth indicators.

Previous migration experiences are negatively associated with the desire to stay. If one has already moved, perhaps one can more easily imagine doing so again. Regarding family and community networks, the number of people on whom youth can rely for material support and the number of relatives in the community are not associated with an aspiration to stay.

The only notable retain factor in is living in an urban area. This effect seems to be primarily driven by India and Vietnam (see Appendix A.2). Indeed, country contexts also show important differences. Even when controlling for other factors, young people in Vietnam and India are more likely to aspire to stay than youth in Ethiopia. Nevertheless, Table A.2 in the Appendix confirms that many of the general patterns from hold for each country. For example, youth enrolled in school are less likely to want to stay where they area. Ethiopia shows stronger effects for education at primary level, while in India and Vietnam, achieving secondary levels of educational attainment is associated with greater desires to leave. Paid work is associated with greater migration aspirations in Ethiopia and Vietnam while work in business is a significant retaining factor in India.

To explore how the determinants of staying aspirations vary for young people from different socioeconomic backgrounds, and analyse staying aspirations by wealth index levels, rural/urban location, and gender. These tables reveal similar trends as those in , but show important differences in where certain relationships concentrate. While all youth, regardless of wealth level, are less likely to aspire to stay where they are if they are enrolled in school or have completed secondary education, even just primary levels of schooling appear to decrease staying aspirations for the most resource-poor youth, those living in rural areas, and for young women. One finds similar trends for the impact of feelings of self-efficacy.

Table 6. Regression analyses: aspirations to stay by wealth index.

Table 7. Regression analyses: aspirations to stay by rural/urban and gender.

Regarding employment, farm work only predicts an aspiration to stay for the poorest and the wealthiest youth. Owning livestock is a retain factor for poorer youth, those in rural settings, and young men. These findings may reflect the fact that farming for wealthier youth offers greater hope or prospects for a future in agriculture than it does for those with less resources, while young people from the poorest households, many of whom will rely upon subsistence farming and livestock to meet their basic needs, may be reluctant to take the risk of leaving their scarce assets. There is a different relationship to paid work, however. Similar to , access to paid employment is associated with lower desires to stay, but we see this effect only among young people in the first and second wealth quintiles. Perhaps for youth from resource-poor households, access to paid employment equips them with the knowledge, networks and financial resources needed to embark on a migration project elsewhere. Interestingly, living in an urban location is associated with the aspiration to stay only for the poorest and wealthiest youth – those in the first and fifth quintiles.

We find similar trends when we compare women and men (). Paid and business employment are both associated with greater migration aspirations for young women, but not men. Education also has stronger effects on the imagined futures of young women; completing just primary levels of education are associated with greater aspirations to migrate. The only instance where we find countervailing trends in how a particular indicator relates to staying aspirations is in how previous migration aspirations relates to the aspiration to stay. Women are more likely to aspire to stay after a previous migration episode, while men are more likely to aspire to leave. This may reflect gendered differences in marriage migration, where women move to join their spouse’s household. This effect is likely driven by India (see Appendix A.2), where half (50%) of all moves by young women between rounds 3 and 4 of the Young Lives survey were for marriage. In Vietnam, 18 per cent of young women’s moves were for marriage, followed by 12 per cent in Ethiopia (Gavonel Citation2017). This kind of early marriage migration is by a particular cohort of young women, usually those with less schooling and resources. It differs significantly from previous migration for studies or work, and thus shows a different relationship with staying aspirations.

Finally, despite family being the most common reason given for staying ( and ), we find the number of family members in one’s immediate community was not a notable retain factor in the regression analyses. The number of people on whom one could rely for material support shows a tentative positive relationship with staying aspirations for young people with middling levels of wealth and for youth in urban areas. It has a more robust effect as a retain factor in Ethiopia (see Appendix A.2).

Discussion

When first embarking on this study, we were eager to gain insight into the retain factors that help explain why many young people prefer to stay where they are. We soon discovered that the most common indicators we use to assess development at the individual or household level have an overwhelmingly negative relationship with staying aspirations – that is, higher levels of education, wealth, feelings of self-efficacy, and paid employment are all associated with greater migration aspirations. These findings resonate with an increasingly sophisticated body of research that argues that human and economic development increases migration propensities in low- and middle-income countries (see Skeldon Citation1997, Citation2012.; de Haas Citation2007 Citation2010; Docquier et al Citation2014; Dao et al Citation2018; Clemens and Postel Citation2018; Clemens Citation2020). One explanation is that, as countries experience the social transformations associated with development – including rising levels of income, education and connectivity – more people develop the aspiration to migrate and acquire the capabilities (i.e. financial, human and social resources) to leave (de Haas Citation2021).

For readers already familiar with the migration-development literature, our findings may come as little surprise. Yet, the basic point remains underappreciated by many working in the field of development, particularly those designing policies and programmes to alleviate the root causes of migration. If one assumes that poverty and unemployment are core drivers of migration, then it is natural to focus on increasing access to schooling and paid work to alleviate the need to migrate. However, our findings suggest that young people with higher levels of education and paid employment are more likely to aspire to migrate. Moreover, young people from less advantaged backgrounds – notably young women, youth in rural areas, and youth from resource-poor households – appear to be more susceptible to these effects.

It is particularly striking that under no circumstances does education – whether measured in terms of current enrolment, attainment, or aspired levels – serve as a retain factor. There is a consistently negative relationship between educational attainment and staying aspirations, even among an age cohort whose upper limits of schooling were just secondary levels. We found the same pattern in a more focused study of the relationship between migration aspirations and formal schooling in Ethiopia (Schewel and Fransen Citation2018); our findings here confirm that this relationship holds for India and Vietnam. Education may diminish a desire to stay for several reasons: education can boost the expected economic returns of leaving, and the skilled work that higher levels of education promise generally concentrate in urban areas. However, the impact of education likely goes deeper, reshaping notions of the good life that young people hold and the kinds of work they come to desire. As others have shown, for many (particularly rural) youth, education often entails ‘learning to leave’ (Corbett Citation2007; Crivello Citation2011 Citation2015; White Citation2012).

Employment has a more complicated relationship with staying aspirations. Farm work is associated with greater desires to stay put, but only for youth from the most resource-poor and the most resource-rich households. The reasons for staying are likely very different for these two groups of youth, the former relying on farming to meet their basic needs while the latter may be the only ones able to envision a desirable future in agriculture. Paid work, on the contrary, is associated with greater migration aspirations – but only for youth from poorer households. Perhaps for these young people, schooling and wage-work enhances access to information, networks and resources that enable or encourage them to imagine a future elsewhere. For most of these youth, ‘elsewhere’ will be a destination within their home country rather than outside of it.

It is also notable that the majority of youth in all countries mentioned family-related reasons as their primary motivation to stay put, yet the number of relatives living in one’s community did not significantly predict a desire to stay. This is likely because our primary indicator for family – the numerical size of local family networks – does not capture the family dynamics that can attract or tie people to home.Footnote7 The presence of family as a reason to stay could reflect several different, even countervailing, realities. It gives support to the positive notion that family and friends are a valued aspect of social life that many are reluctant to leave. However, it may also signal social or economic responsibilities to family that are location-specific and require a person to stay where they are, such as caring for children or aging parents. In another examination of staying aspirations in Senegal, for example, family-related motivations for staying ranged from the joy and peace of mind that comes from being with one’s children to ‘my husband would not agree’ (Schewel Citation2015). While family-related reasons remain common motivations for staying, exactly how family matters or retains people is likely more complex than it initially seems. To better understand this dynamic, further research would benefit from looking more closely at Vietnam, where both staying aspirations and family-related motivations to stay are particularly high.

This relates to a more fundamental concern that perhaps we are not using the right indicators to understand the factors most strongly associated with the aspiration to stay. By focusing on common indicators like wealth, education, or employment, we may have also fallen prey to a particularly narrow conception of what constitutes ‘development’ and what matters to people when they consider their future plans. A forthcoming study by Debray, Ruyssen, and Schewel, for example, uses Gallup World Poll data and finds a range of positive predictors of staying aspirations (at the global level), such as the importance of religion, personal thriving, feelings of safety or trust in local institutions. Had we been able to incorporate similar variables here, we would have likely found evidence for far more retain factors. Future surveys would benefit from trying to capture these more immaterial and non-economic factors that a growing body of qualitative research suggests are fundamental to explaining staying preferences (see Farbotko Citation2018; Adams and Komu Citation2021; Blondin Citation2021; Wyngaarden et al Citation2022).

Conclusion

To understand why so many people do not migrate, it is important to interrogate the aspiration to stay. Widespread immobility is not only a result of financial constraints or political and legal barriers to migration. In this study, the majority of young people—the demographic cohort most likely to aspire to migrate—imagine a future in their homelands. A smaller but still substantial cohort aspires for a future in the locality where they live. To better understand this voluntary immobility, our paper explored the reasons young people give for not wanting to migrate and the individual and household characteristics that are more strongly associated with a desire to stay put.

We began from the assumption that staying aspirations are socially patterned and find important differences in what retains young people depending on their gender, rural/urban location, and levels of wealth. For example, we find that both living in an urban area and engagement in farm work are positively associated with aspirations to stay in place, but only for youth from the poorest and wealthiest backgrounds. Access to paid employment, on the contrary, is associated with greater migration aspirations, particularly for young women, youth from rural areas and from resource-poor households. These findings have important and even counter-intuitive implications for development interventions that seek to decrease migration propensities by creating job opportunities in origin areas. Whether expanding employment will increase or decrease staying propensities depends on the nature and prospects of local employment and the socioeconomic backgrounds of young people engaging in it. For particular subsets of youth – youth from rural areas, poorer households, or young women – accessing paid work may be a stepping stone that provides the networks and financial resources needed to imagine and realise a migration project.

As research continues into the determinants of migration and immobility, future surveys would benefit from considering four issues. First, our focus on immobility aspirations only provides a snapshot of staying aspirations among young people in Ethiopia, India, and Vietnam. This research would be significantly enhanced if it were possible to follow shifts in migration and staying aspirations and behaviour over time. The Young Lives survey only asked about migration aspirations in one survey round. Future longitudinal studies could regularly include questions about migration and staying aspirations to explore how and why these change across the life course, and how they relate to actual migration or immobility outcomes.

Second, future surveys should consider asking about the aspiration to stay directly, rather than treating it as the default to migration desires. A growing number of surveys asking about migration aspirations now include follow-up questions that differentiate between an ideal wish to migrate, intentions and concrete plans, the latter generally being a better indicator of future behaviour (Carling and Schewel Citation2018; Tjaden et al Citation2019). Might it be possible to also include more specific follow-up questions about intentions or plans to stay? ‘Preparing to stay’ may not be as straight forward as ‘preparing to migrate,’ but the degree to which a young person invests in a future locally – whether through buying land or a house, opening their own business, or starting a family – may indicate a greater likelihood of staying.

Third, incorporating questions about the ability to migrate would allow researchers to better distinguish involuntary, voluntary and acquiescent immobility using survey data, as well as interrogate how aspiration and ability might impact each other, through, for example, adaptive preferences (see Carling and Schewel Citation2018, 958-959). Finally, as mentioned in the discussion, researchers interested in the relationship between migration, development, and immobility should include a wider definition of ‘development’ to include social, cultural, and even spiritual dimensions that a growing body of literature suggests are important to explain the preference to stay. By better understanding the influence of these variables, we can gain a more holistic understanding of the factors that are important to people when they make a decision to migrate or to stay.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results was part of the MADE (Migration as Development) Consolidator Grant project, receiving funding from the European Research Council under the European Community's Horizon 2020 Programme (H2020/2015-2020)/ERC Grant Agreement 648496. The authors thank Hein de Haas and Simona Vezzoli for their valuable comments on early drafts of this article.

The data used in this publication come from Young Lives, a 15-year study of the changing nature of childhood poverty in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam (www.younglives.org.uk). Young Lives is funded by UK aid from the Department for International Development (DFID). The views expressed here are those of the author(s). They are not necessarily those of Young Lives, the University of Oxford, DFID or other funders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Peru is a fourth case study country of the Young Lives project, but we did not include it in our sample for several reasons. First, the Peru sample is smaller and significantly more urban. Second, Peru as a country is much more urban, with an economy more firmly grounded in the service sector, meaning the country has a very different development context as compared to Vietnam, India, and Ethiopia.

2 Attrition rates between round 1 and round 4 of data collection ranged from 11.3 per cent in Vietnam to 4.3 per cent in India. In India and Vietnam, the main reasons for attrition among the older cohort include refusals to continue with the research or respondents were ‘untraceable,’ which may be due to migration. Only in Ethiopia was international migration the main reason for attrition (6.4%). The fact that internal and international migration is one reason for attrition may mean that individuals who (aspire to) stay are slightly overrepresented in our sample. Yet, as our aim is to study the individual characteristics of those who aspire to stay versus those who aspire to move, this does not affect our results. For further information More information on sampling and attrition in the four research sites can be found in the Round 4 Survey Design and Sampling Factsheets, which are available online at: www.younglives.org.uk/content/sampling-and-attrition.

3 Farm work referred to work ‘on a farm owned or rented by you or any member of your household (e.g. cultivating crops, farming tasks, caring for livestock)'. Paid employment referred to work ‘for someone who is NOT a member of your household (e.g. a company, the government, neighbours farm)’ and could include agricultural and non-agricultural work. Finally, business activities referred to work ‘on your own account or in a business enterprise belonging to you or someone in your household (e.g. shop-keeper)’ (Young Lives child questionnaire, older cohort, available here: https://www.younglives.org.uk/sites/www.younglives.org.uk/files/et-r4-oc-child-questionnaire.pdf). The job categories are not mutually exclusive, meaning that respondents could have engaged in multiple activities.

4 Good floor quality refers to floors made of a finished material (cement, tile or laminated material), whereas good roof quality refers to roofs that are made of iron, concrete tiles or slates.

5 Our data shows that in some countries, such as Ethiopia, livestock is also common in urban areas: 33 percent of urban youth owns livestock in Ethiopia, versus four and five percent of urban youth in India and Vietnam, respectively.

6 Locations refer to kebeles in Ethiopia, villages in India, and communes in Vietnam.

7 The size of a family may not matter as much as the strength of ties and feelings of responsibility to them, which is inevitably shaped by broader socioeconomic and cultural factors. For example, under conditions of resource scarcity, a commitment to family can also motivate migration. As New Economics of Labor Migration theory suggests, migration is often a household decision; the migration and remittances of one individual helps diversify the income available to a family (Stark and Bloom Citation1985). In other cases, commitment to family may require staying and through one’s physical presence, assuming the responsibilities for a family’s land, livelihood, or elderly members.

References

- Adams, Ria-Maria, and Teresa Komu. 2021. “Radically Ordinary Lives: Young Rural Stayers and the Ingredients of the Good Life in Finnish Lapland.” YOUNG, doi:10.1177/11033088211064685.

- Ayeb-Karlsson, Sonja, Christopher D. Smith, and Dominic Kniveton. 2018. “A Discursive Review of the Textual Use of ‘Trapped' in Environmental Migration Studies: The Conceptual Birth and Troubled Teenage Years of Trapped Populations.” Ambio 47 (5): 557–573.

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215.

- Black, Richard, Nigel W. Adger, Nigel W. Arnell, Stefan Dercon, Andrew Geddes, and David Thomas. 2011. Migration and Global Environmental Change: Future Challenges and Opportunities. UK Government Office for Science. <https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/migration-and-global-environmental-change>

- Blondin, Suzy. 2021. “Staying Despite Disaster Risks: Place Attachment, Voluntary Immobility and Adaptation in Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 126: 290–301.

- Bogue, Donald J. 1959. “Internal Migration’.” In The Study of Population: An Inventory and Appraisal, edited by P. Hauser, and O. Dudley Duncan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Boyden, Jo, Tassew Woldehanna, S. Galab, Alan Sanchez, Mary Penny, and Le Thuc Duc .2016. "Young Lives: an International Study of Childhood Poverty: Round 4, 2013–2014." UK Data Service. SN: 7931. doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-7931-1.

- Carling, Jørgen. 2002. “Migration in the Age of Involuntary Immobility: Theoretical Reflections and Cape Verdean Experiences.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28 (1): 5–42.

- Carling, Jørgen, and Francis Collins. 2018. “Aspiration, Desire and Drivers of Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 909–926. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384134.

- Carling, Jørgen, and Kerilyn Schewel. 2018. “Revisiting Aspiration and Ability in International Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 945–963. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1384146.

- Clemens, Michael. 2020. The Emigration Life Cycle: How Development Shapes Emigration from Poor Countries’ Center for Global Development Working Paper Series (Paper 540).

- Clemens, Michael A., and Hannah M. Postel. 2018. “Deterring Emigration with Foreign Aid: An Overview of Evidence from Low-Income Countries.” Population and Development Review 44 (4): 667–693.

- Cohen, Jeffrey H. 2002. “Migration and “Stay at Homes” in Rural Oaxaca, Mexico: Local Expression of Global Outcomes.” Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 31 (2): 231–259.

- Corbett, Michael. 2007. Learning to Leave: The Irony of Schooling in a Coastal Community. Blackpoint, NS: Fernwood Publishing.

- Crivello, Gina. 2011. “‘Becoming Somebody’: Youth Transitions Through Education and Migration in Peru.” Journal of Youth Studies 14 (4): 395–411. doi:10.1080/13676261.2010.538043.

- Crivello, Gina. 2015. “‘There’s no Future Here’: The Time and Place of Children’s Migration Aspirations in Peru.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 62: 38–46.

- Czaika, Mathias. 2015. “Migration and Economic Prospects.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (1): 58–82.

- Dao, Thu Hien, Frédéric Docquier, Chris Parsons, and Giovanni Peri. 2018. “Migration and Development: Dissecting the Anatomy of the Mobility Transition.” Journal of Development Economics 132: 88–101.

- Debray, Alix, Ilse Ruyssen, and Kerilyn Schewel. forthcoming. Voluntary Immobility: A Global Analysis of Staying Preferences,’ International Migration Institute Working Paper Series.

- de Haas, Hein. 2007. “Turning the Tide? Why Development Will Not Stop Migration.” Development and Change 38 (5): 819–841.

- de Haas, Hein. 2010. Migration Transitions: A Theoretical and Empirical Inquiry into the Developmental Drivers of International Migration’ DEMIG Project Paper, International Migration Institute Working Paper Series. Available from: <migrationinstitute.org>.

- de Haas, Hein. 2021. “A Theory of Migration: The Aspirations-Capabilities Framework.” Comparative Migration Studies 9 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1186/s40878-020-00210-4.

- de Jong, Gordon, and James T Fawcett. 1981. “Motivations for Migration: An Assessment and a Value-Expectancy Research Model’.” In Migration Decision Making: Multidisciplinary Approaches to Microlevel Studies in Developed and Developing Countries, edited by G. de Jong, and R. W. Gardner. Oxford: Pergamon Press.

- Docquier, Frédéric, Giovanni Peri, and Ilse Ruyssen. 2014. “The Cross-Country Determinants of Potential and Actual Migration.” International Migration Review 48 (Fall): 37–99. doi:10.1111/imre.12137.

- Erdal, Marta, Ceri Bivand. 2018. “Forced to Leave? The Discursive and Analytical Significance of Describing Migration as Forced and Voluntary.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (6): 981–998.

- Esipova, Neil, Julie Ray, and Anita Pugliese. 2011. The World's Potential Migration: Who They Are, Where They Want to Go, and Why It Matters. The Gallup Organization.

- Farbotko, Carol. 2018. “Voluntary Immobility: Indigenous Voices in the Pacific.” Forced Migration Review 57: 81–83.

- Fernandez, Bina. 2020. Ethiopian Migrant Domestic Workers: Migrant Agency and Social Change. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fischer, Peter, and Gunnar Malmberg. 2001. “Settled People Don't Move: On Life Course and (Im-)Mobility in Sweden.” International Journal of Population Geography 7 (5): 357–371. doi:10.1002/ijpg.230.

- Gaibazzi, Paolo. 2015. Bush Bound: Young Men and Rural Permanence in Migrant West Africa. Berghahn Books.

- Garip, Filiz. 2012. “Discovering Diverse Mechanisms of Migration: The Mexico-Us Stream 1970-2000.” Population and Development Review 38 (3): 393–433.

- Gavonel, Maria. 2017. “Patterns and Drivers of Internal Migration among Youth in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam.” Young Lives Working Paper Series169.

- Gruber, Elisabeth. 2021. “Staying and Immobility: New Concepts in Population Geography? A Literature Review.” Geographica Helvetica 76 (2): 275–284.

- Hagen-Zanker, Jessica, and Gemma Hennessey. 2021. What Do We Know About the Subjective and Intangible Factors That Shape Migration Decision-Making? A Review of the Literature from Low and Middle Income Countries. PRIO Paper. Oslo: Peace Research Institute Oslo.

- Hammar, Tomas, and Kristof Tamas. 1997. “Why Do People Go or Stay?” In International Migration, Immobility, and Development: Multidisciplinary Perspectives, edited by Tomas Hammar, Grete Brochmann, Kristof Tamas, and Thomas Faist. Oxford: Berg.

- Harris, John R., and Michael P. Todaro. 1970. “Migration, Unemployment, and Development: A Two-Sector Analysis.” American Economic Review 60: 126–142.

- Haug, Sonja. 2008. “Migration Networks and Migration Decision-Making.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34 (4): 585–605.

- Hoppe, Annekatrin, and Kaori Fujishiro. 2015. “Anticipated Job Benefits, Career Aspiration, and Generalized Self-Efficacy as Predictors for Migration Decision-Making.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 47: 13–27.

- Kumra, N. 2008. An Assessment of the Young Lives Sampling Approach in Andhra Pradesh, India, Young Lives Technical Note 2. Oxford: Young Lives.

- Lee, Everett S. 1966. “A Theory of Migration.” Demography 3 (1): 47–57.

- Lewicka, Maria. 2011. “Place Attachment: How Far Have We Come in the Last 40 Years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology 31 (3): 207–230. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001.

- Magali, S., and M. Scipioni. 2018. A Global Analysis of Intentions to Migrate. Brussels: European Commission. Joint Research Center Technical Reports.

- Massey, Douglas S, Joaquin Arango, Graeme Hugo, Ali Kouaouci, and Adela Pellegrino. 1999. Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration at the End of the Millennium. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Mata-Codesal, Diana. 2015. “Ways of Staying Put in Ecuador: Social and Embodied Experiences of Mobility–Immobility Interactions.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 41 (14): 2274–2290.

- Nguyen, N. P. 2008. An Assessment of the Young Lives Sampling Approach in Vietnam, Young Lives Technical Note 4. Oxford: Young Lives.

- Outes-Leon, Ingo, and Alan Sanchez. 2008. An Assessment of the Young Lives Sampling Approach in Ethiopia. Technical Note 1. Oxford: Young Lives.

- Ritchey, P. Neal. 1976. “Explanations of Migration.” Annual Review of Sociology 2: 363–404.

- Robins, Daniel. 2022. “Re-Imagining Belonging to Brazil: Active Immobility in Times of Crisis.” Population, Space and Place. doi.org/10.1002/psp.2558.

- Schewel, Kerilyn. 2015. Understanding the Aspiration to Stay: A Case Study of Young Adults in Senegal’, International Migration Institute Working Paper Series (Working Paper 107):1-37.

- Schewel, Kerilyn. 2020. “Understanding Immobility: Moving Beyond the Mobility Bias in Migration Studies.” International Migration Review 54 (2): 328–355.

- Schewel, Kerilyn. 2021. “Aspiring for Change: Ethiopian Women’s Labor Migration to the Middle East.” Social Forces 100 (4): 1619–1641.

- Schewel, Kerilyn, and Legass Bahir Asmamaw. 2021. “Migration and Development in Ethiopia: Exploring the Mechanisms Behind an Emerging Mobility Transition.” Migration Studies, doi:10.1093/migration/mnab036.

- Schewel, Kerilyn, and Sonja Fransen. 2018. “Formal Education and Migration Aspirations in Ethiopia.” Population and Development Review 44 (3): 555–587.

- Skeldon, Ronald. 1997. Migration and Development: A Global Perspective. Essex: Longman.

- Skeldon, Ronald. 2012. "Migration Transitions Revisited: Their Continued Relevance for The Development of Migration Theory." Population, Space and Place 18:154-166.

- Stark, Oded, and David E. Bloom. 1985. “The New Economics of Labor Migration.” American Economic Review 75: 173–178.

- Tjaden, Jasper, Daniel Auer, and Frank Laczko. 2019. “Linking Migration Intentions with Flows: Evidence and Potential Use.” International Migration 57 (1): 36–57.

- United Nations. 2017. Trends in International Migrant Stock: Migrants by Destination and Origin. UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (United Nations database, POP/DB/MIG/Stock/Rev.2017).

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2019. Human Development Report 2019. Beyond Income, Beyond Averages, Beyond Today: Inequalities in Human Development in the 21st Century. Geneva: UNDP.

- White, Ben. 2012. “Agriculture and the Generation Problem: Rural Youth, Employment and the Future of Farming.” IDS Bulletin 43 (6): 9–19.

- Woldehanna, T., Galab, S., Sanchez, A., Penny, M., Duc L. Thuc, Boyden, J. (2018) Young Lives: an International Study of Childhood Poverty: Round 4, 2013-2014. [data collection]. 2nd Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 7931, doi:10.5255/UKDA-SN-7931-2

- World Bank. 2015. World Development Report 2015: Mind, Society and Behaviour. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

- World Development Indicators (2019) World Development Indicators. The World Bank: Washington, D.C. Available from: <https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators > Accessed 5 May 2019.

- Wyngaarden, Sara, Sally Humphries, Kelly Skinner, Esmeralda Lobo Tosta, Veronica Zelaya Portillo, Paola Orellana, and Warren Dodd. 2022. “‘You Can Settle Here’: Immobility Aspirations and Capabilities among Youth from Rural Honduras.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, doi:10.1080/1369183X.2022.2031922.

- Zewdu, Girmachew Adugna. 2018. “Irregular Migration, Informal Remittances: Evidence from Ethiopian Villages.” GeoJournal 83 (5): 1019–1034. doi:10.1007/s10708-017-9816-5.

APPENDIX

Figure A.1. Expected Years of Schooling by Country (1990-2017). Source: UNDP Citation2019

Figure A.2. Poverty Indicators by Country. Source: World Development Indicators (Citation2019). Numbers refer to different years: 2015 for Ethiopia, 2011 for India, 2018 for Peru, and 2018 for Vietnam.

Figure A.3. Fieldwork locations in Ethiopia, India and Vietnam. (a) Ethiopia. Derived from: Young Lives Survey Design and Sampling in Ethiopia. Preliminary Findings from the 2013 Young Lives Survey (Round 4). Young Lives 2014, available at: https://www.younglives-ethiopia.org. (b) India. Derived from: Young Lives Survey Design and Sampling in India. Preliminary Findings from the 2013 Young Lives Survey (Round 4). Young Lives 2014, available at: www.younglivesindia.org. (c) Vietnam. Derived from: Young Lives Survey Design and Sampling in Vietnam. Preliminary Findings from the 2013 Young Lives Survey (Round 4). Young Lives 2014, available at: www.younglives-vietnam.org.

Table A.1. Aspirations to stay, by respondent characteristics: Descriptive statistics.

Table A.2. Regression Analysis: By Country